Abstract

Background

Gestational Diabetes Mellitus (GDM) affects approximately 1 in 7 pregnancies globally. It is associated with short- and long-term risks for both mother and baby. Therefore, optimizing treatment to effectively treat the condition has wide-ranging beneficial effects. However, despite the known heterogeneity in GDM, treatment guidelines and approaches are generally standardized. We hypothesized that a precision medicine approach could be a tool for risk-stratification of women to streamline successful GDM management. With the relatively short timeframe available to treat GDM, commencing effective therapy earlier, with more rapid normalization of hyperglycaemia, could have benefits for both mother and fetus.

Methods

We conducted two systematic reviews, to identify precision markers that may predict effective lifestyle and pharmacological interventions.

Results

There was a paucity of studies examining precision lifestyle-based interventions for GDM highlighting the pressing need for further research in this area. We found a number of precision markers identified from routine clinical measures that may enable earlier identification of those requiring escalation of pharmacological therapy (to metformin, sulphonylureas or insulin). This included previous history of GDM, Body Mass Index and blood glucose concentrations at diagnosis.

Conclusions

Clinical measurements at diagnosis could potentially be used as precision markers in the treatment of GDM. Whether there are other sensitive markers that could be identified using more complex individual-level data, such as omics, and if these can feasibly be implemented in clinical practice remains unknown. These will be important to consider in future studies.

Subject terms: Gestational diabetes, Predictive markers, Combination drug therapy

Plain language summary

Gestational diabetes (GDM) is high blood sugar first detected during pregnancy. Normalizing blood sugar levels quickly is important to avoid pregnancy complications. Many women achieve this with lifestyle changes, such as to diet, but some need to inject insulin or take tablets. We did two thorough reviews of existing research to see if we could predict which women need medication. Firstly we looked for ways to identify the characteristics of women who benefit most from changing their lifestyles to treat GDM, but found very limited research on this topic. We secondly searched for characteristics that help identify women who need medication to treat GDM. We found some useful characteristics that are obtained during routine pregnancy care. Further studies are needed to test if additional information could provide even better information about how we could make GDM treatment more tailored for individuals during pregnancy.

Benham, Gingras, McLennan, Most, Yamamoto, Aiken et al. conduct two systematic reviews and meta-analyses to evaluate whether a precision-based medicine approach can be adopted to improve the clinical management of gestational diabetes (GDM). They find some precision markers that may improve the treatment course of GDM but further research is needed.

Introduction

Gestational diabetes (GDM) is the most common pregnancy complication, occurring in 3–25% of pregnancies globally1. GDM is associated with short- and long-term risks to both mothers and babies, including adverse perinatal outcomes, future obesity, type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease1–3. The landmark Australian Carbohydrate Intolerance Study in Pregnant Women (ACHOIS) demonstrated that effective treatment of GDM reduces serious perinatal morbidity4.

Current treatment guidelines for management of GDM assume homogeneous treatment requirements and responses, despite the known heterogeneity of GDM aetiology5–8. Standard care includes diet and lifestyle advice at a multi-disciplinary clinic, home blood glucose monitoring at least four times per day, clinic reviews every 2 to 4 weeks, and then progression to pharmacological treatment with metformin, glyburide and/or insulin if glucose targets are not met. Around a third of women cannot maintain euglycaemia with lifestyle measures alone and require treatment escalation to a pharmacological agent3. Yet current treatment pathways often take 4–8 weeks to achieve glucose targets. This delay resulting in continued exposure to hyperglycaemia poses a risk of accelerated foetal growth9,10. Previous research has suggested that maternal characteristics including body mass index (BMI) ≥ 30 kg/m2, family history of type 2 diabetes, prior history of GDM and higher glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) increase the likelihood of need for insulin treatment in GDM11, indicating the potential for risk-stratification of women to streamline successful GDM management. There is emerging evidence that precision biomarkers predict treatment response in type 2 diabetes, which has similar heterogeneity to GDM12,13 and thus gives rationale to investigate whether a similar precision approach could be successful in optimising outcomes in GDM.

To address this knowledge gap, we conducted two systematic reviews of the available evidence for precision markers of GDM treatment. We aimed to determine which patient-level characteristics are precision markers for predicting (i) responses to personalised diet and lifestyle interventions delivered in addition to standard of care (ii) requirement for escalation of treatment in women treated with diet and lifestyle alone, and in women receiving pharmacological agents for the treatment of GDM. For both reviews we considered whether the precision markers predicted achieving glucose targets, as well as maternal and neonatal outcomes. The Precision Medicine in Diabetes Initiative (PMDI) was established in 2018 by the American Diabetes Association (ADA) in partnership with the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). The ADA/EASD PMDI includes global thought leaders in precision diabetes medicine who are working to address the burgeoning need for better diabetes prevention and care through precision medicine14. This systematic review is written on behalf of the ADA/EASD PMDI as part of a comprehensive evidence evaluation in support of the 2nd International Consensus Report on Precision Diabetes Medicine15.

We find a paucity of studies examining precision lifestyle-based interventions for GDM highlighting the pressing need for further research in this area. We find a number of precision markers identified from routine clinical measures that may enable earlier identification of those requiring escalation of pharmacological therapy (to metformin, sulphonylureas or insulin). These findings suggest that clinical measurements at diagnosis could potentially be used as precision markers in the treatment of GDM. Whether there are other sensitive markers that could be identified using more complex individual-level data, such as omics, and if these can feasibly be implemented in clinical practice remains unknown and will be important to consider in future studies.

Methods

The systematic reviews and meta-analyses were performed as outlined a priori in the registered protocols (PROSPERO registration IDs CRD42022299288 and CRD42022299402). The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines16 were followed. Ethical approval was not required as these were secondary studies using published data.

Literature searches, search strategies and eligibility criteria

Search strategies for both reviews were developed based on relevant keywords in partnership with scientific librarians (see Supplementary Note 1 for full search strategies). We searched two databases (MEDLINE and EMBASE) for studies published from inception until January 1st, 2022. We also scanned the references of included manuscripts for inclusion as well as relevant reviews and meta-analyses published within the past two years for additional citations.

For both systematic reviews we included studies (randomised or non-randomised trials and observational studies) published in English and including women ≥16 years old with diagnosed GDM, as defined by the study authors. For the first systematic review (precision diet and lifestyle interventions), we included studies with any behavioural intervention using any approach (e.g., specific exercise, dietary interventions, motivational interviewing) that examined precision markers that could tailor a lifestyle intervention in a more precise way compared to a control group receiving standard care only. For the second systematic review (precision markers for escalation of pharmacological interventions to achieve glucose targets), we included studies investigating women with GDM that required escalation of pharmacological therapy (e.g., insulin, metformin, sulphonylurea) compared to women with GDM that achieved glucose targets with diet and lifestyle measures only, or women with GDM treated with oral agents that required progression to insulin to achieve glucose targets. For both reviews, we included any relevant reported outcomes; maternal (e.g., treatment adherence, hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, gestational weight gain, mode of birth), neonatal (e.g., birthweight, macrosomia, shoulder dystocia, preterm birth, neonatal hypoglycaemia, neonatal death), cost efficiency or acceptability. We excluded studies with a total sample size <50 participants to ensure sufficient data to interpret the effect of precision markers. We also excluded studies published before or during 2004, in order to consider studies with standard care similar to ACHOIS4.

Study selection and data extraction

The results of our two searches were imported separately into Covidence software (Veritas Health Innovation, Australia, available at www.covidence.org) and duplicates were removed. Two reviewers independently reviewed identified studies. First, they screened titles and abstracts of all references identified from the initial search. In a second step, the full-text articles of potentially relevant publications were scrutinised in detail and inclusion criteria were applied to select eligible articles. Reason for exclusion at the full-text review stage was documented. Disagreement between reviewers was resolved through consensus by discussion with the group of authors.

Two reviewers independently extracted relevant information from each eligible study, using a pre-specified standardised extraction form. Any disagreement between reviewers was resolved as outlined above.

Data extracted included first author name, year of publication, country, study design, type and details of the intervention when applicable, number of cases/controls or cohort groups, total number of participants and diagnostic criteria used for GDM. Extracted data elements also included outcomes measures, size of the association (Odds Ratio (OR), Relative Risk (RR) or Hazard Ratio (HR)) with corresponding 95% Confidence Interval (CI) and factors adjusted for, confounding factors taken into consideration and methods used to control covariates. We prioritised adjusted values where both raw and adjusted data were available. Details of precision markers (mean (standard deviation) for continuous variables or N (%) for categorical variables) including BMI (pre-pregnancy or during pregnancy), ethnicity, age, smoking status, comorbidities, parity, glycaemic variables (e.g., oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) diagnostic values, HbA1c), timing of GDM diagnosis, history of diabetes or of GDM, and season were also extracted.

Quality assessment (risk of bias and GRADE assessments)

We first assessed the quality and risk of bias of each individual study using the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) critical appraisal tools17. A Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluations (GRADE) approach was then used to review the total evidence for each precision marker, and the quality of the included studies to assign a GRADE certainty to this body of evidence (high, moderate, low and/or very low)18. Quality assessment was performed in duplicate and conflicts were resolved through consensus.

Statistical analysis

Where possible, meta-analyses were conducted using random effects models for each precision marker available. The pooled effect size (mean difference for continuous outcomes and ORs for categorical outcomes) with the corresponding 95% CI was computed. The heterogeneity of the studies was quantified using I2 statistics, where I2 > 50% represents moderate and I2 > 75% represents substantial heterogeneity across studies. Publication bias was assessed with visual assessment of funnel plots. Statistical analyses were performed using Review Manager software [RevMan, Version 5.4.1, The Cochrane Collaboration, Copenhagen, Denmark].

As part of the diabetes scientific community, we are sensitive in using inclusive language, especially in relation to gender. However, the vast majority of original studies that the GDM precision medicine working groups reviewed used women as their terminology to describe their population, as GDM per definition occurs in pregnancy which can only occur in individuals that are female at birth. To be consistent with the original studies defined populations, we use the word ‘women’ in our summary of the evidence, current gaps and future perspectives, but fully acknowledge that not all individuals who experienced a pregnancy may self-identify as women at all times over their life course.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Results

Study selection and study characteristics

PRISMA flow charts (Figs. 1 and 2) summarise both searches and study selection processes.

Fig. 1. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagrams for precision approaches to enhance behavioural (diet and lifestyle) interventions.

The PRISMA flow diagram details the search and selection process applied in the review.

Fig. 2. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagrams for precision markers for escalation of pharmacological interventions.

The PRISMA flow diagram details the search and selection process applied in the review.

For the first systematic review (precision approaches to diet and lifestyle interventions), we identified 2 eligible studies (n = 2354 participants), which were randomised trials from USA and Singapore (Supplementary Data 1)19,20.

For the second systematic review (precision markers for escalation of pharmacological interventions to achieve target glucose levels), we identified 48 eligible studies (n = 25,724 participants) (Supplementary Data 2)21–68. There were 34 studies (n = 23,831 participants) investigating precision markers for escalation to pharmacological agent(s) in addition to standard care with diet and lifestyle advice. Of these, 29 studies (n = 20,486) reported escalation to insulin as the only option21–49 and 5 (n = 3345) reported escalation to any medication (metformin, glyburide and/or insulin)50–54. There were 12 studies (n = 1836 participants) investigating precision markers for escalation to insulin when treatment with oral agents was not adequate to achieve target glucose levels. Initial treatment was with glyburide in 6 of these studies (n = 527)55–60 and metformin in the other 6 studies (n = 1142)61–66. A further 2 eligible studies reported maternal genetic predictors of need for supplementary insulin after glyburide (n = 117 participants)67 and maternal lipidome responses to metformin and insulin (n = 217 participants)68.

The majority of included studies were observational in design. Most studies reported outcomes of singleton pregnancies. The studies were from a range of geographical locations: Europe (Belgium, Finland, France, Italy, Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Spain, Sweden), Switzerland, Middle East (Israel, Qatar, United Arab Emirates), Australasia (Australia, New Zealand), North America/Latin America (Canada, USA and Brazil) and Asia (China, Malaysia, Japan). There were a range of approaches to GDM screening, choice of diagnostic test and diagnostic glucose thresholds.

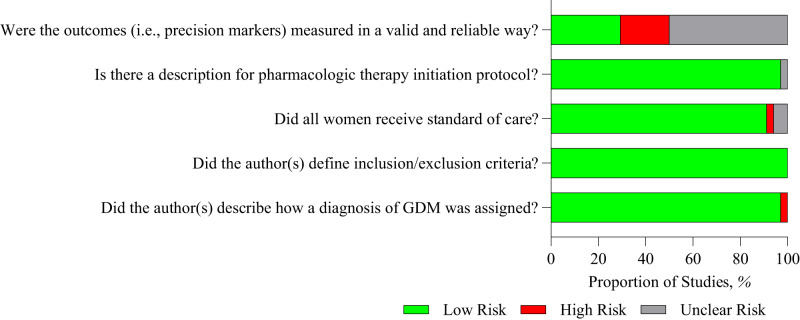

Quality assessment

Study quality assessment is presented as an overall risk of bias for the studies included in the meta-analyses in Fig. 3 and as a heat map for quality assessment for each included study in Fig. 4. Most of the studies were rated as low risk of bias, as they adequately described how a diagnosis of GDM was assigned, defining inclusion and exclusion criteria, and reported the protocol for initiation of pharmacological therapy. Not all studies reported whether women received diet and lifestyle advice as standard care. Few studies reported whether the precision marker was measured in a valid and reliable way. Using the GRADE approach, the majority of precision markers were classified as having a low certainty of evidence with some classified as very low certainty (Tables 1 and 2). No publication bias (as ascertained by funnel plot analyses) was detected.

Fig. 3. Risk of bias graph: review authors’ judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all studies included in the meta-analyses.

Green circle with + sign, Yes, Red circle with – sign, No, Blank – not described.

Fig. 4. Risk of bias summary: review authors’ judgements about each risk of bias item for each study included in the meta-analyses.

Green – low risk of bias, Grey – unclear risk of bias, Red – high risk of bias.

Table 1.

Lifestyle adequate to achieve target glucose levels vs need for escalation to pharmacological agent(s) to achieve glucose targets.

| Precision Marker | Studies | Participants | Statistical Method | Effect Estimate (95%CI) | GRADE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 20 | 14620 | Mean difference (95%CI) | −0.98 [−1.23, −0.73] | ⊕⊕◯◯ |

| Nulliparity | 8 | 6969 | Odds Ratio (95%CI) | 1.53 [1.23, 1.89] | ⊕⊕◯◯ |

| Body mass index kg/m2 | 16 | 11313 | Mean difference (95%CI) | −1.83 [−2.32, −1.35] | ⊕⊕◯◯ |

| Previous history of GDM | 13 | 9885 | Odds Ratio (95%CI) | 0.46 [0.37, 0.57] | ⊕⊕◯◯ |

| Haemoglobin A1C (%) | 8 | 4825 | Mean difference (95%CI) | −0.21 [−0.27, −0.14] | ⊕⊕◯◯ |

| Fasting glucose (mg/dl) | 13 | 8663 | Mean difference (95%CI) | −6.26 [−8.44, −4.08] | ⊕⊕◯◯ |

| 1-h glucose(mg/dl) | 10 | 6579 | Mean difference (95%CI) | −15.33 [−20.81, −9.85] | ⊕◯◯◯ |

| 2-h glucose(mg/dl) | 12 | 8255 | Mean difference (95%CI) | −9.06 [−13.55, −4.56] | ⊕◯◯◯ |

| 3-h glucose(mg/dl) | 3 | 2126 | Mean difference (95%CI) | −8.56 [−12.58, −4.54] | ⊕◯◯◯ |

| Family history of diabetes | 13 | 9256 | Odds Ratio (95%CI) | 0.66 [0.59, 0.75] | ⊕⊕◯◯ |

| Gestational age at GDM diagnosis (weeks) | 9 | 5882 | Mean difference (95%CI) | 3.06 [2.33, 3.79] | ⊕⊕◯◯ |

| Smoking history | 5 | 3488 | Odds Ratio (95%CI) | 0.80 [0.52, 1.23] | ⊕⊕◯◯ |

| Previous history of macrosomia | 7 | 5595 | Odds Ratio (95%CI) | 0.63 [0.42, 0.94] | ⊕⊕◯◯ |

Very low ⊕◯◯◯.

Low ⊕⊕◯◯.

Table 2.

Oral pharmacological agent adequate to achieve target glucose levels vs need for escalation to insulin to achieve glucose targets.

| Precision Marker | Studies | Participants | Statistical method | Effect Estimate (95%CI) | GRADE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 11 | 1473 | Mean difference (95%CI) | −1.04 [−2.10, 0.03] | ⊕⊕◯◯ |

| Nulliparity | 8 | 1215 | Odds Ratio (95%CI) | 1.55 [1.17, 2.04] | ⊕⊕◯◯ |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 10 | 1692 | Mean difference (95%CI) | −1.21 [−2.21, −0.21] | ⊕⊕◯◯ |

| Previous history of GDM | 8 | 1412 | Odds Ratio (95%CI) | 0.43 [0.30, 0.63] | ⊕⊕◯◯ |

| Haemoglobin A1C (%) | 6 | 1152 | Mean difference (95%CI) | −0.21 [−0.29, −0.13] | ⊕⊕◯◯ |

| Fasting glucose (mg/dl) | 12 | 1836 | Mean difference (95%CI) | −8.02 [−11.87, −4.16] | ⊕◯◯◯ |

| 1-h glucose (mg/dl) | 8 | 1177 | Mean difference (95%CI) | −10.64 [−18.25, −3.02] | ⊕◯◯◯ |

| 2-h glucose (mg/dl) | 10 | 1378 | Mean difference (95%CI) | −7.31 [−11.38, −3.25] | ⊕◯◯◯ |

| 3-h glucose (mg/dl) | 6 | 679 | Mean difference (95%CI) | 0.00 [−11.79, 11.79] | ⊕◯◯◯ |

| Family history of diabetes | 6 | 1040 | Odds Ratio (95%CI) | 0.79 [0.50, 1.25] | ⊕⊕◯◯ |

| Gestational age at GDM diagnosis (weeks) | 11 | 1473 | Mean difference (95%CI) | 2.64 [1.42, 3.86] | ⊕⊕◯◯ |

| Gestation at oral pharmacological agent initiation (weeks) | 7 | 967 | Mean difference (95%CI) | 3.79 [2.08, 5.51] | ⊕⊕◯◯ |

Very low ⊕◯◯◯.

Low ⊕⊕◯◯.

Precision diet and lifestyle interventions in GDM

Two studies examining different precision approaches to behavioural interventions were included in the first systematic review, so we present a narrative synthesis of the findings. Neither study examined whether a precision approach to specific lifestyle interventions facilitated achievement of glucose targets during pregnancy or improved outcomes that reflect glycaemic control during pregnancy such as macrosomia, large for gestational age, or neonatal hypoglycaemia.

In one study of women with GDM19, the intervention was distribution of a tailored letter based on electronic health record data detailing gestational weight gain (GWG) recommendations (as defined by the Institute of Medicine). Receipt of this tailored letter increased the likelihood of meeting the end-of-pregnancy weight goal among women with normal pre-pregnancy BMI, but not among women with overweight or obese pre-pregnancy BMI. This study identified normal pre-pregnancy BMI as a precision marker for intervention success.

The second study20 used a Web/Smart phone lifestyle coaching programme in women with GDM. Pre-intervention excessive GWG was evaluated as a potential precision marker for the response to the Web/Smart phone lifestyle coaching programme in preventing excess GWG. There was no difference between study arms with respect to either excess GWG or absolute GWG by the end of pregnancy indicating that early GWG is not a useful precision marker with respect to this intervention.

Precision markers for escalation of pharmacological interventions to achieve glucose targets in GDM

Of the 34 studies of precision markers for escalation to pharmacological therapy to achieve glucose targets in addition to standard care with diet and lifestyle advice, 23 studies (n = 19,112 participants) were included in the meta-analysis21–23,25,26,31–36,38,40,41,43–46,48,50–53 and 11 studies (n = 7158 participants) in the narrative synthesis24,27–30,37,39,42,47,49,54.

Table 1 and Supplementary Figs. 1–13 show that precision markers for GDM to be adequately managed with lifestyle measures were lower maternal age, nulliparity, lower BMI, no previous history of GDM, lower HbA1c, lower glucose values at the diagnostic OGTT (fasting, 1 h, 2 and/or 3 h glucose), no family history of diabetes, later gestation of diagnosis of GDM and no macrosomia in previous pregnancies. There was a similar pattern for not smoking but this did not reach statistical significance.

Twelve studies (n = 1836 participants) of precision markers for escalation to insulin to achieve glucose targets in addition to oral agents were included in the meta-analysis55–66.

Table 2 and Supplementary Figs. 14–25 show that precision markers for achieving glucose targets with oral agents only were nulliparity, lower BMI, no previous history of GDM, lower HbA1c, lower glucose values at the diagnostic OGTT (fasting, 1 h, and/or 2 h glucose), later gestation of diagnosis of GDM and later gestation at initiation of the oral agent. In sensitivity analyses, there were no differences in the precision markers predicting response to metformin versus glyburide (Supplementary Data 3).

Similar precision markers for escalation to pharmacotherapy to achieve glucose targets were observed in the 11 studies (n = 7158 participants) that were not included in the meta-analysis24,27–30,37,39,42,47,49,54 (Supplementary Data 4). Additional precision markers including foetal sex28, ethnicity30,47 and season of birth37 were evaluated in some studies but there was insufficient data to draw conclusions.

There was a paucity of data in examining other precision markers with only weak evidence that the maternal lipidome68 or genetics67 hold potential as precision markers for escalation of pharmacological treatment (Supplementary Data 4).

Discussion

As the factors contributing to the development of GDM and its aetiology are heterogeneous5–8, it is plausible that the most effective treatment strategies may also be variable among women with GDM. A precision medicine approach resulting in more rapid normalisation of hyperglycaemia could have substantial benefits for both mother and foetus. By synthesising the evidence from two systematic reviews, we sought to identify key precision markers that may predict effective lifestyle and pharmacological interventions. There were a paucity of studies examining precision approaches to better target lifestyle-based interventions for GDM treatment highlighting the pressing need for further research in this area. However, we found a number of precision markers to enable earlier identification of those requiring escalation of pharmacological therapy. These included characteristics such as BMI, that are easily and routinely measured in clinical practice, and thus have potential to be integrated into prediction models with the aim of achieving rapid glycaemic control. With the relatively short timeframe available to treat GDM, commencing effective therapy earlier, and thus reducing excess foetal growth, is an important target to improve outcomes. Basing treatment decisions closely on precision markers could also avoid over-medicalisation of women who are likely to achieve glucose targets with dietary counselling alone.

In our first systematic review, we identified only two studies addressing precision markers in lifestyle-based interventions for GDM, over and above the usual lifestyle intervention as standard care19,20. In both studies, precision markers were examined as secondary analyses of the trials and only two precision markers (communication of GWG goals according to pre-pregnancy BMI; and early GWG as a precision marker for the efficacy of technological enhancement to a behavioural intervention) were assessed; it is thus not possible to conclusively identify any precision marker in lifestyle-based interventions for GDM. This gap in the literature highlights the need for more research, as also echoed by patients and healthcare professionals participating in the 2020 James Lind Alliance (JLA) Priority Setting Partnership (PSP)69.

Our second systematic review extends the observations of a previous systematic review reporting maternal characteristics associated with the need for insulin treatment in GDM11. We identified a number of additional precision markers of successful GDM treatment with lifestyle measures alone, without need for additional pharmacological therapy. The same set of predictors identified women requiring additional insulin after treatment with glyburide as with metformin, despite their different mechanisms of action. However, the numbers of women included in most studies were relatively low and most studies with data in relation to need to escalation to insulin in addition to glyburide were over 10 years old55,56,58–60. We acknowledge that there are also differences in diagnostic criteria, clinical practices, and preferences for choice of which drug to start as first pharmacological agent in various global regions which may limit the generalisability of our findings.

Notably, many of the identified precision markers are routinely measured in clinical practice and so could be incorporated into prediction models of need for pharmacological treatment70,71. By identifying those who require escalation of pharmacological therapy earlier, better allocation of resources can be achieved. Additionally, some of the precision markers identified, such as BMI, are potentially modifiable. This raises the question of how women can be helped to better prepare for pregnancy72. Implementing interventions prior to pregnancy could help understand if these precision markers are on the causal pathway, thus providing an opportunity for prevention and improving health outcomes.

Importantly, there was a lack of data on other potential precision treatment biomarkers, with only two eligible low-quality studies reporting maternal genetic and metabolomic findings67,68. In the non-pregnancy literature, efficacy of dietary interventions has been reported to differ for patients with distinct metabolic profiles, for example high fasting glucose versus high fasting insulin, or insulin resistance versus low insulin secretion73–75. More recent evidence from appropriately designed, prospective dietary intervention studies has confirmed that dietary interventions tailored towards specific metabolic profiles have more beneficial effects than interventions not specifically designed towards a patient’s metabolic profile76–79. Ongoing studies such as the Westlake Precision Birth Cohort (WeBirth) in China (NCT04060056) and the USA Hoosier Moms Cohort (NCT03696368) are collecting additional biomarkers which will enhance knowledge in this field. However, implementing such measures in clinical practice, if they prove informative, could be complex and expensive and thus not suitable for use in all global contexts.

Our study has several limitations: Our reviews primarily relied on secondary analyses from observational studies that were not specifically designed to address the question of precision medicine in GDM treatment and were not powered for many of the comparisons made. Prior to introduction in clinical practice, any marker would have to be rigorously and prospectively tested with respect to sensitivity and specificity to predict treatment needs. The majority of data were extracted from clinical records leading to a lack of detail, such as the precise timing of BMI measurements, and limited information about whether BMI was self-reported or clinician measured. There was marked variation in approaches to GDM screening methods, choice of glucose challenge test and diagnostic thresholds as well as heterogeneity in glucose targets or criteria met to warrant escalation in treatment. Whilst we included studies from a range of geographical settings, the majority of studies were from high income settings, and therefore our findings may not be applicable to low- and middle-income countries. Pregnancy outcomes of precision medicine strategies for GDM also remain unknown, underscoring the need for tailored interventions that account for patient perspective and diverse patient populations.

Despite these limitations, our study has several strengths. We used robust methods to identify a broad range of precision markers, many of which are routinely measured and can be easily translated into prediction models. We excluded studies where the choice of drug was decided by the clinician based on participant characteristics to avoid bias. Our study also highlights the need for further research in this area, particularly in exploring whether there are more sensitive markers that could be identified through omics approaches.

In conclusion, our findings suggest that precision medicine for GDM treatment holds promise as a tool to stream-line individuals towards the most effective and potentially cost-effective care. Whether this will impact on short-term pregnancy outcomes and longer term health outcomes for both mother and baby is not known. More research is urgently needed to identify precision lifestyle interventions and to explore whether more sensitive markers could be identified. Prospective studies, appropriately powered and designed to allow assessment of discriminative abilities (sensitivity, specificity), and (external) validation studies are urgently needed to understand the utility and generalisability of our findings to under-represented populations. This is an area of active research with findings from ongoing studies (NCT04187521, NCT03029702, NCT05932251) eagerly awaited. Consideration of how identified markers can be implemented feasibly and cost effectively in clinical practice is also required. Such efforts will be critical for realising the full potential of precision medicine and empowering patients and their health care providers to optimise short and long-term health outcomes for both mother and child.

Supplementary information

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Acknowledgements

The ADA/EASD Precision Diabetes Medicine Initiative, within which this work was conducted, has received the following support: The Covidence license was funded by Lund University (Sweden) for which technical support was provided by Maria Björklund and Krister Aronsson (Faculty of Medicine Library, Lund University, Sweden). Administrative support was provided by Lund University (Malmö, Sweden), University of Chicago (IL, USA), and the American Diabetes Association (Washington D.C., USA). The Novo Nordisk Foundation (Hellerup, Denmark) provided grant support for in-person writing group meetings (PI: L Phillipson, University of Chicago, IL). J.M.M. acknowledges the support of the Henry Friesen Professorship in Endocrinology, University of Manitoba, Canada. N.-M.M. and R.M.R. acknowledge the support of the British Heart Foundation (RE/18/5/34216). S.E.O. is supported by the Medical Research Council (MC_UU_00014/4) and British Heart Foundation (RG/17/12/33167).

Author contributions

All authors J.L.B., V.G., N.-M.M., J.M., J.M.Y., C.E.A., S.E.O. and R.M.R. contributed to the design of the research questions, study selection, extraction of data, data analyses, quality assessment and data interpretation. The ADA/EASD PMDI consortium members provided feedback on methodology and reporting guidelines. RMR wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors edited the manuscript and all approved the final version.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Medicine thanks Rochan Agha-Jaffar and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available

Data availability

The included studies are detailed in Supplementary Data 1 and 2. The data underlying Tables 1 and 2 are in Supplementary Figs. 1–13 and 14–25, respectively. Additional information is available via contact with the corresponding author.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Jamie L. Benham, Véronique Gingras, Niamh-Maire McLennan, Jasper Most, Jennifer M. Yamamoto, Catherine E. Aiken.

These authors jointly supervised this work: Susan E. Ozanne, Rebecca M. Reynolds.

A list of authors and their affiliations appears at the end of the paper.

Contributor Information

Rebecca M. Reynolds, Email: r.reynolds@ed.ac.uk

ADA/EASD PMDI:

Deirdre K. Tobias, Jordi Merino, Abrar Ahmad, Catherine Aiken, Dhanasekaran Bodhini, Amy L. Clark, Kevin Colclough, Rosa Corcoy, Sara J. Cromer, Daisy Duan, Jamie L. Felton, Ellen C. Francis, Pieter Gillard, Romy Gaillard, Eram Haider, Alice Hughes, Jennifer M. Ikle, Laura M. Jacobsen, Anna R. Kahkoska, Jarno L. T. Kettunen, Raymond J. Kreienkamp, Lee-Ling Lim, Jonna M. E. Männistö, Robert Massey, Niamh-Maire Mclennan, Rachel G. Miller, Mario Luca Morieri, Rochelle N. Naylor, Bige Ozkan, Kashyap Amratlal Patel, Scott J. Pilla, Katsiaryna Prystupa, Sridharan Raghavan, Mary R. Rooney, Martin Schön, Zhila Semnani-Azad, Magdalena Sevilla-Gonzalez, Pernille Svalastoga, Wubet Worku Takele, Claudia Ha-ting Tam, Anne Cathrine B. Thuesen, Mustafa Tosur, Amelia S. Wallace, Caroline C. Wang, Jessie J. Wong, Katherine Young, Chloé Amouyal, Mette K. Andersen, Maxine P. Bonham, Mingling Chen, Feifei Cheng, Tinashe Chikowore, Sian C. Chivers, Christoffer Clemmensen, Dana Dabelea, Adem Y. Dawed, Aaron J. Deutsch, Laura T. Dickens, Linda A. DiMeglio, Monika Dudenhöffer-Pfeifer, Carmella Evans-Molina, María Mercè Fernández-Balsells, Hugo Fitipaldi, Stephanie L. Fitzpatrick, Stephen E. Gitelman, Mark O. Goodarzi, Jessica A. Grieger, Marta Guasch-Ferré, Nahal Habibi, Torben Hansen, Chuiguo Huang, Arianna Harris-Kawano, Heba M. Ismail, Benjamin Hoag, Randi K. Johnson, Angus G. Jones, Robert W. Koivula, Aaron Leong, Gloria K. W. Leung, Ingrid M. Libman, Kai Liu, S. Alice Long, William L. Lowe, Jr., Robert W. Morton, Ayesha A. Motala, Suna Onengut-Gumuscu, James S. Pankow, Maleesa Pathirana, Sofia Pazmino, Dianna Perez, John R. Petrie, Camille E. Powe, Alejandra Quinteros, Rashmi Jain, Debashree Ray, Mathias Ried-Larsen, Zeb Saeed, Vanessa Santhakumar, Sarah Kanbour, Sudipa Sarkar, Gabriela S. F. Monaco, Denise M. Scholtens, Elizabeth Selvin, Wayne Huey-Herng Sheu, Cate Speake, Maggie A. Stanislawski, Nele Steenackers, Andrea K. Steck, Norbert Stefan, Julie Støy, Rachael Taylor, Sok Cin Tye, Gebresilasea Gendisha Ukke, Marzhan Urazbayeva, Bart Van der Schueren, Camille Vatier, John M. Wentworth, Wesley Hannah, Sara L. White, Gechang Yu, Yingchai Zhang, Shao J. Zhou, Jacques Beltrand, Michel Polak, Ingvild Aukrust, Elisa de Franco, Sarah E. Flanagan, Kristin A. Maloney, Andrew McGovern, Janne Molnes, Mariam Nakabuye, Pål Rasmus Njølstad, Hugo Pomares-Millan, Michele Provenzano, Cécile Saint-Martin, Cuilin Zhang, Yeyi Zhu, Sungyoung Auh, Russell de Souza, Andrea J. Fawcett, Chandra Gruber, Eskedar Getie Mekonnen, Emily Mixter, Diana Sherifali, Robert H. Eckel, John J. Nolan, Louis H. Philipson, Rebecca J. Brown, Liana K. Billings, Kristen Boyle, Tina Costacou, John M. Dennis, Jose C. Florez, Anna L. Gloyn, Maria F. Gomez, Peter A. Gottlieb, Siri Atma W. Greeley, Kurt Griffin, Andrew T. Hattersley, Irl B. Hirsch, Marie-France Hivert, Korey K. Hood, Jami L. Josefson, Soo Heon Kwak, Lori M. Laffel, Siew S. Lim, Ruth J. F. Loos, Ronald C. W. Ma, Chantal Mathieu, Nestoras Mathioudakis, James B. Meigs, Shivani Misra, Viswanathan Mohan, Rinki Murphy, Richard Oram, Katharine R. Owen, Susan E. Ozanne, Ewan R. Pearson, Wei Perng, Toni I. Pollin, Rodica Pop-Busui, Richard E. Pratley, Leanne M. Redman, Maria J. Redondo, Rebecca M. Reynolds, Robert K. Semple, Jennifer L. Sherr, Emily K. Sims, Arianne Sweeting, Tiinamaija Tuomi, Miriam S. Udler, Kimberly K. Vesco, Tina Vilsbøll, Robert Wagner, Stephen S. Rich, and Paul W. Franks

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s43856-023-00371-0.

References

- 1.Saravanan P. Gestational diabetes: opportunities for improving maternal and child health. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2020;8:793–800. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(20)30161-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vounzoulaki E, et al. Progression to type 2 diabetes in women with a known history of gestational diabetes: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2020;369:m1361. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Metzger BE, et al. Hyperglycemia and adverse pregnancy outcomes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008;358:1991–2002. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0707943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Crowther CA, et al. Effect of treatment of gestational diabetes mellitus on pregnancy outcomes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005;352:2477–2486. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa042973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Powe CE, Hivert MF, Udler MS. Defining heterogeneity among women with gestational diabetes mellitus. Diabetes. 2020;69:2064–2074. doi: 10.2337/dbi20-0004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Powe CE, et al. Heterogeneous contribution of insulin sensitivity and secretion defects to gestational diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2016;39:1052–1055. doi: 10.2337/dc15-2672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Benhalima K, et al. Characteristics and pregnancy outcomes across gestational diabetes mellitus subtypes based on insulin resistance. Diabetologia. 2019;62:2118–2128. doi: 10.1007/s00125-019-4961-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Madsen LR, et al. Do variations in insulin sensitivity and insulin secretion in pregnancy predict differences in obstetric and neonatal outcomes? Diabetologia. 2021;64:304–312. doi: 10.1007/s00125-020-05323-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harrison RK, Cruz M, Wong A, Davitt C, Palatnik A. The timing of initiation of pharmacotherapy for women with gestational diabetes mellitus. BMC Preg, Childbirth. 2020;20:773. doi: 10.1186/s12884-020-03449-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tisi DK, Burns DH, Luskey GW, Koski KG. Fetal exposure to altered amniotic fluid glucose, insulin, and insulin-like growth factor-binding protein 1 occurs before screening for gestational diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2011;34:139–144. doi: 10.2337/dc10-0607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alvarez-Silvares E, Bermúdez-González M, Vilouta-Romero M, García-Lavandeira S, Seoane-Pillado T. Prediction of insulin therapy in women with gestational diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. J. Perinat. Med. 2022;50:608–619. doi: 10.1515/jpm-2021-0247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dennis JM, Shields BM, Henley WE, Jones AG, Hattersley AT. Disease progression and treatment response in data-driven subgroups of type 2 diabetes compared with models based on simple clinical features: an analysis using clinical trial data. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2019;7:442–451. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(19)30087-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dawed AY, et al. Pharmacogenomics of GLP-1 receptor agonists: a genome-wide analysis of observational data and large randomised controlled trials. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2023;11:33–41. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(22)00340-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nolan JJ, et al. ADA/EASD Precision Medicine in Diabetes Initiative: an international perspective and future vision for precision medicine in diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2022;45:261–266. doi: 10.2337/dc21-2216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tobias, D. K., Merino, J., Ahmad, A. & PMDI, A. E. Second international consensus report on gaps and opportunities for the clinical translation of precision diabetes medicine. Nat. Med. (in press), 10.1038/s41591-023-02502-5. (2023) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann. Intern. Med. 2009;151:264–269. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) critical appraisal tools https://jbi.global/critical-appraisal-tools. Accessed 15 April 2023.

- 18.Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluations (GRADE) https://guidelines.diabetes.ca/cpg/chapter2. Accessed 15 April 2023.

- 19.Hedderson MM, et al. A tailored letter based on electronic health record data improves gestational weight gain among women with gestational diabetes mellitus: the Gestational Diabetes’ Effects on Moms (GEM) cluster-randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Care. 2018;41:1370–1377. doi: 10.2337/dc17-1133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yew TW, et al. A randomized controlled trial to evaluate the effects of a smartphone application-based lifestyle coaching program on gestational weight gain, glycemic control, and maternal and neonatal outcomes in women with gestational diabetes mellitus: the SMART-GDM study. Diabetes Care. 2021;44:456–463. doi: 10.2337/dc20-1216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ares J, et al. Gestational Diabetes Mellitus (GDM): relationship between higher cutoff values for 100g Oral Glucose Tolerance Test (OGTT) and insulin requirement during pregnancy. Matern. Child Health J. 2017;21:1488–1492. doi: 10.1007/s10995-017-2269-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barnes RA, et al. Predictors of large and small for gestational age birthweight in offspring of women with gestational diabetes mellitus. Diabet. Med. 2013;30:1040–1046. doi: 10.1111/dme.12207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Benhalima K, et al. Differences in pregnancy outcomes and characteristics between insulin- and diet-treated women with gestational diabetes. BMC Preg. Childbirth. 2015;15:271. doi: 10.1186/s12884-015-0706-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Berg M, Adlerberth A, Sultan B, Wennergren M, Wallin G. Early random capillary glucose level screening and multidisciplinary antenatal teamwork to improve outcome in gestational diabetes mellitus. Acta Obstetr. Gynecol, Scand. 2007;86:283–290. doi: 10.1080/00016340601110747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ducarme G, et al. Predictive factors of subsequent insulin requirement for glycemic control during pregnancy at diagnosis of gestational diabetes mellitus. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstetr. 2019;144:265–270. doi: 10.1002/ijgo.12753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Durnwald CP, et al. Glycemic characteristics and neonatal outcomes of women treated for mild gestational diabetes. Obstetr. Gynecol. 2011;117:819–827. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31820fc6cf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Elnour AA. Antenatal oral glucose-tolerance test values and pregnancy outcomes. Int. J. Pharm Pract. 2008;16:189–197. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Giannubilo SR, Pasculli A, Ballatori C, Biagini A, Ciavattini A. Fetal sex, need for insulin, and perinatal outcomes in gestational diabetes mellitus: an observational cohort study. Clin. Ther. 2018;40:587–592. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2018.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gibson KS, Waters TP, Catalano PM. Maternal weight gain in women who develop gestational diabetes mellitus. Obstetr. Gynecol. 2012;119:560–565. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31824758e0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hillier TA, Ogasawara KK, Pedula KL, Vesco KK. Markedly different rates of incident insulin treatment based on universal gestational diabetes mellitus screening in a diverse HMO population. Am. J. Obstetr. Gynecol. 2013;209:440.e441–449. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2013.06.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ikenoue S, et al. Clinical impact of women with gestational diabetes mellitus by the new consensus criteria: two year experience in a single institution in Japan. Endocr. J. 2014;61:353–358. doi: 10.1507/endocrj.ej13-0496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ito Y, et al. Indicators of the need for insulin treatment and the effect of treatment for gestational diabetes on pregnancy outcomes in Japan. Endocr. J. 2016;63:231–237. doi: 10.1507/endocrj.EJ15-0427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kalok, A. et al. Correlation between oral glucose tolerance test abnormalities and adverse pregnancy outcomes in gestational diabetes: a cross-sectional study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health17, 6990 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Koning SH, et al. Risk stratification for healthcare planning in women with gestational diabetes mellitus. Netherlands J. Med. 2016;74:262–269. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mecacci F, et al. Different gestational diabetes phenotypes: which insulin regimen fits better? Front. Endocrinol. 2021;12:630903. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2021.630903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Meghelli L, Vambergue A, Drumez E, Deruelle P. Complications of pregnancy in morbidly obese patients: What is the impact of gestational diabetes mellitus? J. Gynecol. Obstetr. Hum. Reprod. 2020;49:101628. doi: 10.1016/j.jogoh.2019.101628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Molina-Vega M, et al. Relationship between environmental temperature and the diagnosis and treatment of gestational diabetes mellitus: an observational retrospective study. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;744:140994. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.140994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ng A, Liu A, Nanan R. Association between insulin and post-caesarean resuscitation rates in infants of women with GDM: a retrospective study. J. Diabetes. 2020;12:151–157. doi: 10.1111/1753-0407.12974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nguyen TH, Yang JW, Mahone M, Godbout A. Are there benefits for gestational diabetes mellitus in treating lower levels of hyperglycemia than standard recommendations? Can. J. Diabetes. 2016;40:548–554. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjd.2016.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nishikawa T, et al. One-hour oral glucose tolerance test plasma glucose at gestational diabetes diagnosis is a common predictor of the need for insulin therapy in pregnancy and postpartum impaired glucose tolerance. J. Diabetes Investig. 2018;9:1370–1377. doi: 10.1111/jdi.12848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ouzounian JG, et al. One-hour post-glucola results and pre-pregnancy body mass index are associated with the need for insulin therapy in women with gestational diabetes. J. Matern.-Fetal Neonatal Med. 2011;24:718–722. doi: 10.3109/14767058.2010.521869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Parrettini S, et al. Gestational diabetes: a link between OGTT, maternal-fetal outcomes and maternal glucose tolerance after childbirth. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2020;30:2389–2397. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2020.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Silva JK, Kaholokula JK, Ratner R, Mau M. Ethnic differences in perinatal outcome of gestational diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:2058–2063. doi: 10.2337/dc06-0458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Souza A, et al. Can we stratify the risk for insulin need in women diagnosed early with gestational diabetes by fasting blood glucose? J. Matern-Fetal Neonatal Med. 2019;32:2036–2041. doi: 10.1080/14767058.2018.1424820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Suhonen L, Hiilesmaa V, Kaaja R, Teramo K. Detection of pregnancies with high risk of fetal macrosomia among women with gestational diabetes mellitus. Acta Obstetr. Gynecol. Scand. 2008;87:940–945. doi: 10.1080/00016340802334377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sun T, et al. The effects of insulin therapy on maternal blood pressure and weight in women with gestational diabetes mellitus. BMC Preg. Childbirth. 2021;21:657. doi: 10.1186/s12884-021-04066-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wong VW. Gestational diabetes mellitus in five ethnic groups: a comparison of their clinical characteristics. Diabet. Med. 2012;29:366–371. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2011.03439.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wong VW, Jalaludin B. Gestational diabetes mellitus: who requires insulin therapy? Aust. N.Z. J. Obstetr. Gynaecol. 2011;51:432–436. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-828X.2011.01329.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zawiejska A, Wender-Ozegowska E, Radzicka S, Brazert J. Maternal hyperglycemia according to IADPSG criteria as a predictor of perinatal complications in women with gestational diabetes: a retrospective observational study. J. Matern.-Fetal Neonatal Med. 2014;27:1526–1530. doi: 10.3109/14767058.2013.863866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bashir M, et al. Metformin-treated-GDM has lower risk of macrosomia compared to diet-treated GDM- a retrospective cohort study. J. Matern.-Fetal Neonatal Med. 2020;33:2366–2371. doi: 10.1080/14767058.2018.1550480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gilbert L, et al. Mental health and its associations with glucose-lowering medication in women with gestational diabetes mellitus. A prospective clinical cohort study. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2021;124:105095. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2020.105095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Krispin E, Ashkenazi Katz A, Shmuel E, Toledano Y, Hadar E. Characterization of women with gestational diabetes who failed to achieve glycemic control by lifestyle modifications. Arch. Gynecol. Obstetr. 2021;303:677–683. doi: 10.1007/s00404-020-05780-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Meshel S, et al. Can we predict the need for pharmacological treatment according to demographic and clinical characteristics in gestational diabetes? J. Matern.-Fetal Neonatal Med. 2016;29:2062–2066. doi: 10.3109/14767058.2015.1077225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhu S, Meehan T, Veerasingham M, Sivanesan K. COVID-19 pandemic gestational diabetes screening guidelines: a retrospective study in Australian women. Diabetes & Metabolic Syndrome. 2021;15:391–395. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2021.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chmait R, Dinise T, Moore T. Prospective observational study to establish predictors of glyburide success in women with gestational diabetes mellitus. J. Perinatol. 2004;24:617–622. doi: 10.1038/sj.jp.7211147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Conway DL, Gonzales O, Skiver D. Use of glyburide for the treatment of gestational diabetes: the San Antonio experience. J. Matern.-Fetal Neonatal Med. 2004;15:51–55. doi: 10.1080/14767050310001650725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Harper LM, Glover AV, Biggio JR, Tita A. Predicting failure of glyburide therapy in gestational diabetes. J. Perinatol. 2016;36:347–351. doi: 10.1038/jp.2015.216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kahn BF, Davies JK, Lynch AM, Reynolds RM, Barbour LA. Predictors of glyburide failure in the treatment of gestational diabetes. Obstetr. Gynecol. 2006;107:1303–1309. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000218704.28313.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rochon M, Rand L, Roth L, Gaddipati S. Glyburide for the management of gestational diabetes: risk factors predictive of failure and associated pregnancy outcomes. Am. J. Obstetr. Gynecol. 2006;195:1090–1094. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yogev Y, et al. Glyburide in gestational diabetes–prediction of treatment failure. J. Matern.-Fetal Neonatal Med. 2011;24:842–846. doi: 10.3109/14767058.2010.531323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gante I, Melo L, Dores J, Ruas L, Almeida MDC. Metformin in gestational diabetes mellitus: predictors of poor response. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2018;178:129–135. doi: 10.1530/EJE-17-0486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Khin MO, Gates S, Saravanan P. Predictors of metformin failure in gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) Diabetes Metab. Syndr. 2018;12:405–410. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2018.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.McGrath RT, Glastras SJ, Hocking S, Fulcher GR. Use of metformin earlier in pregnancy predicts supplemental insulin therapy in women with gestational diabetes. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2016;116:96–99. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2016.04.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Picón-César MJ, et al. Metformin for gestational diabetes study: metformin vs insulin in gestational diabetes: glycemic control and obstetrical and perinatal outcomes: randomized prospective trial. Am. J. Obstetr. Gynecol. 2021;225:517.e511–517.e517. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2021.04.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rowan JA, Hague WM, Gao W, Battin MR, Moore MP. Metformin versus insulin for the treatment of gestational diabetes. N. Engl J. Med. 2008;358:2003–2015. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0707193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tertti K, Ekblad U, Koskinen P, Vahlberg T, Rönnemaa T. Metformin vs. insulin in gestational diabetes. A randomized study characterizing metformin patients needing additional insulin. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2013;15:246–251. doi: 10.1111/dom.12017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bouchghoul H, et al. Hypoglycemia and glycemic control with glyburide in women with gestational diabetes and genetic variants of cytochrome P450 2C9 and/or OATP1B3. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2021;110:141–148. doi: 10.1002/cpt.2142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Huhtala MS, Tertti K, Rönnemaa T. Serum lipids and their association with birth weight in metformin and insulin-treated patients with gestational diabetes. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2020;170:108456. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2020.108456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ayman G, et al. The top 10 research priorities in diabetes and pregnancy according to women, support networks and healthcare professionals. Diabet. Med. 2021;38:e14588. doi: 10.1111/dme.14588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cooray SD, et al. Development, validation and clinical utility of a risk prediction model for adverse pregnancy outcomes in women with gestational diabetes: the PeRSonal GDM model. EClinicalMedicine. 2022;52:101637. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2022.101637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Liao LD, et al. Development and validation of prediction models for gestational diabetes treatment modality using supervised machine learning: a population-based cohort study. BMC Med. 2022;20:307. doi: 10.1186/s12916-022-02499-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Cassinelli EH, et al. Preconception health and care policies and guidelines in the UK and Ireland: a scoping review. Lancet. 2022;400:S61. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hjorth, M. F. et al. Pretreatment Fasting glucose and insulin as determinants of weight loss on diets varying in macronutrients and dietary fibers-the POUNDS LOST study. Nutrients11, 586 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 74.Hjorth MF, et al. Pretreatment fasting plasma glucose and insulin modify dietary weight loss success: results from 3 randomized clinical trials. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2017;106:499–505. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.117.155200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hjorth MF, Due A, Larsen TM, Astrup A. Pretreatment fasting plasma glucose modifies dietary weight loss maintenance success: results from a stratified RCT. Obesity. 2017;25:2045–2048. doi: 10.1002/oby.22004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bergia, R. E. et al. Differential glycemic effects of low- versus high-glycemic index Mediterranean-style eating patterns in adults at risk for type 2 diabetes: the MEDGI-Carb randomized controlled trial. Nutrients14, 706 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 77.Aldubayan MA, et al. A double-blinded, randomized, parallel intervention to evaluate biomarker-based nutrition plans for weight loss: the PREVENTOMICS study. Clin. Nutr. 2022;41:1834–1844. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2022.06.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Trouwborst I, et al. Cardiometabolic health improvements upon dietary intervention are driven by tissue-specific insulin resistance phenotype: a precision nutrition trial. Cell Metab. 2023;35:71–83.e75. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2022.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Cifuentes L, et al. Phenotype tailored lifestyle intervention on weight loss and cardiometabolic risk factors in adults with obesity: a single-centre, non-randomised, proof-of-concept study. EClinicalMedicine. 2023;58:101923. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2023.101923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Data Availability Statement

The included studies are detailed in Supplementary Data 1 and 2. The data underlying Tables 1 and 2 are in Supplementary Figs. 1–13 and 14–25, respectively. Additional information is available via contact with the corresponding author.