Abstract

Decreased total CO2 (tCO2) is significantly associated with all-cause mortality in critically ill patients. Because of a lack of data to evaluate the impact of tCO2 in patients with COVID-19, we assessed the impact of tCO2 on all-cause mortality in this study. We retrospectively reviewed the data of hospitalized patients with COVID-19 in two Korean referral hospitals between February 2020 and September 2021. The primary outcome was in-hospital mortality. We assessed the impact of tCO2 as a continuous variable on mortality using the Cox-proportional hazard model. In addition, we evaluated the relative factors associated with tCO2 ≤ 22 mmol/L using logistic regression analysis. In 4,423 patients included, the mean tCO2 was 24.8 ± 3.0 mmol/L, and 17.9% of patients with tCO2 ≤ 22 mmol/L. An increase in mmol/L of tCO2 decreased the risk of all-cause mortality by 4.8% after adjustment for age, sex, comorbidities, and laboratory values. Based on 22 mmol/L of tCO2, the risk of mortality was 1.7 times higher than that in patients with lower tCO2. This result was maintained in the analysis using a cutoff value of tCO2 24 mmol/L. Higher white blood cell count; lower hemoglobin, serum calcium, and eGFR; and higher uric acid, and aspartate aminotransferase were significantly associated with a tCO2 value ≤ 22 mmol/L. Decreased tCO2 significantly increased the risk of all-cause mortality in patients with COVID-19. Monitoring of tCO2 could be a good indicator to predict prognosis and it needs to be appropriately managed in patients with specific conditions.

Subject terms: Medical research, Nephrology

Introduction

Low levels of serum bicarbonate usually indicate metabolic acidosis or renal compensation for respiratory alkalosis. Metabolic acidosis is relatively common among seriously ill patients, especially in subjects with major organ dysfunction, and is closely associated with increased mortality1–4. The presence of metabolic acidosis affects diverse organ systems, and the cardiovascular system is the organ most critically affected, exhibiting a change in vascular resistance and cardiac output depending on the level of pH5. Moreover, metabolic acidosis leads to increased inflammation and interleukin stimulation via macrophage production and impaired immune response6. In addition to metabolic acidosis, respiratory distress reduces the level of serum bicarbonate. This could reflect various responses that are complexly intertwined depending on patients' underlying conditions and problems. Therefore, it might be necessary to intervene based on a detailed assessment, especially for critically ill patients.

To obtain information on acid–base status, including serum bicarbonate levels, arterial blood gas analysis is primarily used. However, a relatively invasive technique is required to obtain blood, and detailed processing is essential7. Instead of serum bicarbonate, measuring serum total carbon dioxide (tCO2) could be a good method to assess acid–base status, and serum tCO2 exhibits a significant correlation with bicarbonate concentration8. Serum tCO2 also has the strength of a convenient measurement approach, which can be done along with the measurement of serum creatinine and electrolytes using a biochemical analyzer. In this regard, serum tCO2 could be a useful option for the assessment of a specific group with infectious diseases showing high transmission infectivity, such as that associated with novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) infection.

After the outbreak of COVID-19 in December 2019, approximately 6 million people died worldwide9. Although mortality differed across countries and pandemic periods, the case-fatality rate was reported to range from 0.4 to 15%10. The mortality rate was higher among hospitalized patients with older age, decreased oxygen saturation, elevated levels of C-reactive protein (CRP), and underlying disease11,12. Acidosis also has a role in dysregulation of the immune system and multidirectional inflammatory reactions, and it is regarded as a factor related to the pathogenesis of severe forms of COVID-19 infection13. In addition, COVID-19 infection is closely associated with respiratory failure characterized by desaturation, hypercapnia, and acid–base imbalance, as well as a poor prognosis14. However, there was a lack of data to show the exact association between metabolic acidosis status and mortality risk in patients with COVID-19.

As a significant risk factor and confounding factor, we aimed to evaluate the impact of decreased levels of tCO2 on mortality in hospitalized patients with COVID-19 in this study. Moreover, we tried to identify the factors related to decreased tCO2 based on the cutoff value representing an increased mortality risk in this population.

Results

Baseline characteristics

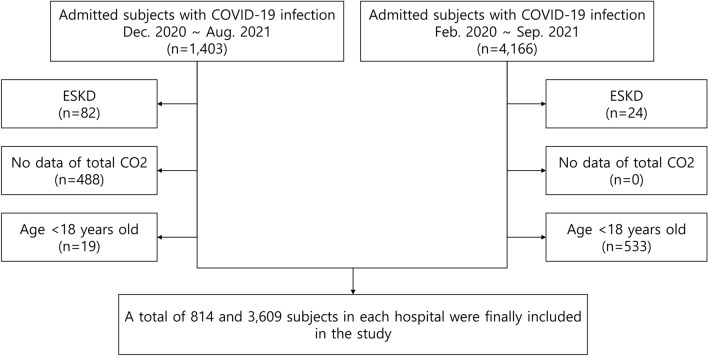

A total of 4,423 patients were included in this study (Fig. 1). There were 792 (17.9%) patients with tCO2 ≤ 22 mmol/L at the time of admission to the hospital due to COVID-19 infection. In the comparison of the two groups according to the cutoff of 22 mmol/L tCO2, patients with lower tCO2 showed older age; a higher prevalence of males; higher white blood cell (WBC) count, aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), uric acid, and CRP; and lower hemoglobin, platelet, serum calcium, serum albumin, and lower potassium. The prevalence of comorbidities such as hypertension, diabetes, cerebrovascular disease, and cardiovascular disease was higher in patients with lower tCO2 (Table 1). There were 17 patients with acute kidney injury requiring kidney replacement therapy (KRT), and it was more frequent in patients with lower tCO2.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram for the study populations. ESKD, end-stage kidney disease; CO2, carbon dioxide.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics according to the tCO2 level.

| Variables | Total (n = 4423) | tCO2 > 22 (n = 3631) | tCO2 ≤ 22 (n = 792) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, year | 54.7 ± 18.3 | 53.8 ± 18.0 | 58.7 ± 19.1 | < 0.001 |

| Sex, male, n (%) | 1,935 (45.7) | 1,527 (44.4) | 408 (51.5) | < 0.001 |

| WBC, × 1,000/uL | 5.3 ± 2.5 | 5.1 ± 2.3 | 5.8 ± 3.1 | < 0.001 |

| Hemoglobin, mg/dL | 13.4 ± 1.8 | 13.5 ± 1.7 | 13.0 ± 2.0 | < 0.001 |

| Platelet, × 1,000/uL | 193.9 ± 73.5 | 195.8 ± 73.1 | 185.3 ± 74.8 | < 0.001 |

| Calcium, mg/dL | 8.7 ± 0.9 | 8.7 ± 0.8 | 8.4 ± 1.0 | < 0.001 |

| Phosphorus, mg/dL | 3.2 ± 0.7 | 3.2 ± 0.6 | 3.2 ± 0.9 | 0.963 |

| Potassium, mmol/L | 4.0 ± 0.5 | 4.0 ± 0.5 | 4.1 ± 0.6 | 0.029 |

| Glucose, mg/dL | 129.2 ± 52.6 | 127.2 ± 50.0 | 138.4 ± 63.1 | < 0.001 |

| BUN, mg/dL | 14.5 ± 10.7 | 13.5 ± 8.6 | 19.0 ± 16.4 | < 0.001 |

| Creatinine, mg/dL | 1.0 ± 1.8 | 0.9 ± 1.7 | 1.3 ± 1.9 | < 0.001 |

| eGFR, mL/min/1.73 m2 | 94.2 ± 25.0 | 96.4 ± 22.4 | 84.0 ± 32.7 | < 0.001 |

| Total bilirubin, mg/dL | 0.5 ± 0.4 | 0.6 ± 0.3 | 0.6 ± 0.5 | 0.108 |

| AST, mg/dL | 37.0 ± 33.8 | 35.5 ± 29.0 | 43.7 ± 50.0 | < 0.001 |

| ALT, mg/dL | 30.7 ± 33.4 | 30.3 ± 33.4 | 32.4 ± 33.7 | 0.106 |

| Protein, g/dL | 6.8 ± 0.6 | 6.8 ± 0.6 | 6.7 ± 0.6 | < 0.001 |

| Albumin, g/dL | 4.0 ± 0.5 | 4.1 ± 0.5 | 3.9 ± 0.5 | < 0.001 |

| Uric acid, mg/dL | 2.5 ± 2.5 | 2.2 ± 2.5 | 4.0 ± 2.1 | < 0.001 |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dL | 152.1 ± 38.2 | 153.7 ± 37.7 | 144.0 ± 40.0 | < 0.001 |

| C-reactive protein, mg/dL | 2.9 ± 4.4 | 2.8 ± 4.3 | 3.3 ± 4.7 | 0.008 |

| tCO2, mmol/L | 24.8 ± 3.0 | 23.4 ± 4.8 | 20.3 ± 1.9 | < 0.001 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 522 (11.8) | 385 (11.2) | 110 (13.9) | < 0.001 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 333 (7.5) | 226 (6.6) | 89 (11.2) | 0.033 |

| Cerebrovascular disease, n (%) | 65 (1.5) | 46 (1.3) | 19 (2.4) | 0.016 |

| Cardiovascular disease, n (%) | 51 (1.2) | 36 (1.0) | 15 (1.9) | 0.031 |

| Obstructive pulmonary disease, n (%) | 69 (1.6) | 58 (1.6) | 11 (1.4) | 0.668 |

| Acute kidney injury requiring KRT, n (%) | 17 (0.4) | 8 (0.2) | 9 (1.1) | < 0.001 |

| In-hospital staying periods, days | 11.8 ± 8.5 | 11.7 ± 8.2 | 12.4 ± 9.7 | 0.030 |

WBC, white blood cell; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; tCO2, total carbon dioxide; KRT, kidney replacement therapy.

We evaluated tCO2 level according to the underlying comorbidities including hypertension, diabetes, cerebrovascular disease, cardiovascular disease, and obstructive pulmonary disease. The level of mean tCO2 was significantly lower in patients with diabetes, cerebrovascular disease, and cardiovascular disease (Table S1). On the contrary, there was no difference based on hypertension or obstructive pulmonary disease.

Impact of tCO2 on all-cause mortality

During the in-hospital staying periods of 11.8 ± 8.6 days, there were 92 (2.5%) and 53 (6.7%) mortality cases in the subgroup of tCO2 > 22 mmol/L and ≤ 22 mmol/L, respectively. Mortality cases showed older age; higher levels of inflammatory markers, such as WBC and CRP; lower levels of nutritional markers, such as serum albumin and total cholesterol; and a higher prevalence of comorbidities, including hypertension, diabetes, cerebrovascular disease, and cardiovascular disease (Table S2). Patients with acute kidney injury requiring KRT also showed higher mortality. The mean level of tCO2 was significantly different between the survival (24.9 ± 3.0) and mortality (23.4 ± 4.8) groups. An increase in tCO2 of 1 mmol/L significantly reduced the risk of death by approximately 5% (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR] 0.94, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.90–0.98) after adjustment for laboratory results and comorbidities (Table 2). Considering the impact of lactate level on acidosis status and mortality, we performed a Cox-proportional analysis including the lactate variable. Although, there were only 18.4% of patients with lactate levels, lower tCO2 significantly increased the risk of in-hospital mortality (aHR 0.94, P = 0.024).

Table 2.

Significance of tCO2 in terms of all-cause mortality.

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P-value | aHR (95% CI) | P-value | aHR (95% CI) | P value | aHR (95% CI) | P value | |

| tCO2 | 0.90 (0.86, 0.94) | < 0.001 | 0.93 (0.89, 0.97) | 0.001 | 0.93 (0.89, 0.97) | < 0.001 | 0.94 (0.90, 0.98) | 0.006 |

Model 1: Unadjusted.

Model 2: Adjusted for age and sex.

Model 3: Adjusted for variables in model 2 with comorbidities including hypertension, diabetes, cerebrovascular disease, cardiovascular disease, pulmonary disease, and acute kidney injury requiring kidney replacement therapy.

Model 4: Adjusted for variables in model 3 with laboratory variables including white blood cell count, hemoglobin, platelet, potassium, calcium, glucose, blood urea nitrogen, eGFR, protein, albumin, uric acid, total cholesterol, total bilirubin, C-reactive protein.

HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; aHR, adjusted hazard ratio; tCO2, total carbon dioxide.

A cut-off value of tCO2 representing the increased mortality

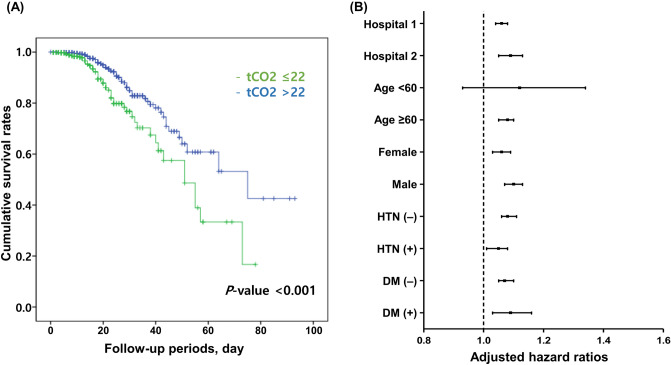

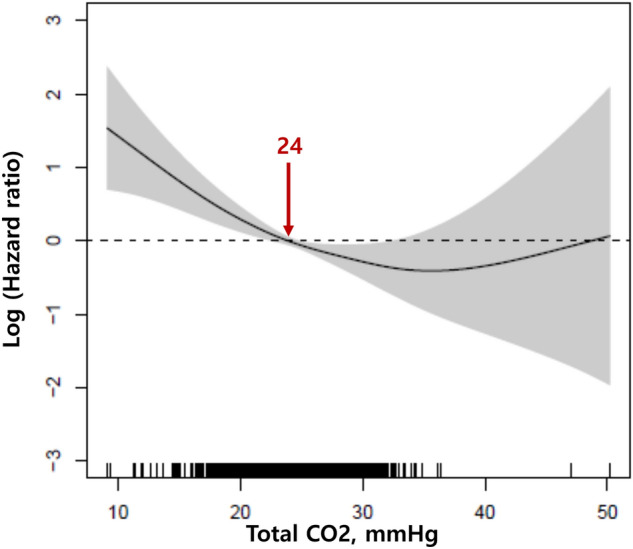

Based on the level of 22 mmol/L, the mortality rate was significantly different between group classified according to tCO2 level (Fig. 2A). This result was maintained irrespective of the each hospital (Fig. S1), sex, and comorbidities, such as hypertension and diabetes, in the subanalysis (Fig. 2B). In subjects with tCO2 ≤ 22 mmol/L, the mortality rate was significantly increased by 1.78 times compared to that in patients with tCO2 > 22 mmol/L. We additionally identified 24 mmol/L tCO2 as a new cutoff value indicating an increased mortality risk using a generalized additive model in this study (Fig. 3). Based on this new cutoff value, the mortality risk was well discriminated (Fig. S2). The risk of mortality (1.73 times) in subjects with tCO2 ≤ 24 mmol/L was similar to that in individuals classified according to the prior cutoff value of tCO2, 22 mmol/L (Table 3).

Figure 2.

(A) Cumulative survival rate according to the 22 mmol/L cutoff of tCO2 and (B) subgroup analysis according to the each hospital, age 60 years, sex, and comorbidities such as hypertension and diabetes. Adjusted hazard ratios are shown with 95% confidence intervals. Adjusted variables in subgroup analyses: age, sex, white blood cell count, hemoglobin, platelets, calcium, glucose, blood urea nitrogen, eGFR, protein, albumin, uric acid, total cholesterol, total bilirubin, aspartate aminotransferase, C-reactive protein, hypertension, and diabetes.

Figure 3.

Cutoff value representing the increased risk of mortality based on the generalized additive model.

Table 3.

Significance of tCO2 in terms of all-cause mortality based on the different cut-off value.

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P-value | aHR (95% CI) | P-value | aHR (95% CI) | P value | HR (95% CI) | P-value | |

| tCO2 ≤ 24 | 1.95 (1.37, 2.76) | < 0.001 | 1.65 (1.19, 2.30) | 0.003 | 1.69 (1.21, 2.37) | 0.002 | 1.73 (1.16, 2.58) | 0.008 |

| tCO2 ≤ 22 | 2.17 (1.53, 3.07) | < 0.001 | 1.76 (1.25, 2.47) | 0.001 | 1.82 (1.28, 2.59) | < 0.001 | 1.78 (1.18, 2.67) | 0.006 |

Model 1: Unadjusted.

Model 2: Adjusted for age and sex.

Model 3: Adjusted for variables in model 2 with comorbidities including hypertension, diabetes, cerebrovascular disease, cardiovascular disease, pulmonary disease, and acute kidney injury requiring kidney replacement therapy.

Model 4: Adjusted for variables in model 3 with laboratory variables including white blood cell count, hemoglobin, platelet, potassium, calcium, glucose, blood urea nitrogen, eGFR, protein, albumin, uric acid, total cholesterol, total bilirubin, C-reactive protein.

HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; aHR, adjusted hazard ratio; tCO2, total carbon dioxide.

Relative factors associated with lower tCO2

Several factors were associated with tCO2 ≤ 22 mmol/L in patients with COVID-19 infection. Most variables were associated with lower tCO2 in the unadjusted model. However, after adjustment with significant variables in model 2, there was no association with age or sex on the lower tCO2. Among the laboratory parameters, higher WBC, lower hemoglobin, lower calcium, lower estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), and higher uric acid, and AST were significantly associated with tCO2 ≤ 22 mmol/L in adjusted model. In particular, the significance of comorbidities including hypertension, diabetes, cerebrovascular disease, cardiovascular disease, and acute kidney injury requiring KRT was attenuated in the adjusted model (Table 4).

Table 4.

Relative factors associated with tCO2 ≤ 22.

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P value | aOR (95% CI) | P value | |

| Age, years | 1.02 (1.01, 1.02) | < 0.001 | 0.99 (0.99, 1.00) | 0.086 |

| Sex, male, n(%) | 1.33 (1.14, 1.56) | < 0.001 | 1.04 (0.83, 1.30) | 0.730 |

| WBC, × 1,000/uL | 1.11 (1.08, 1.14) | < 0.001 | 1.07 (1.03, 1.11) | < 0.001 |

| Hemoglobin, mg/dL | 0.88 (0.84, 0.91) | < 0.001 | 0.92 (0.86, 0.98) | 0.014 |

| Platelet, × 1,000/uL | 0.998 (0.997, 0.999) | < 0.001 | 1.00 (1.00, 1.00) | 0.212 |

| Calcium, mg/dL | 0.73 (0.67, 0.80) | < 0.001 | 0.70 (0.60, 0.80) | < 0.001 |

| Phosphorus, mg/dL | 1.00 (0.89, 1.12) | 0.970 | ||

| Potassium, mmol/L | 1.21 (1.03, 1.42) | 0.019 | 1.05 (0.87, 1.28) | 0.602 |

| Glucose, mg/dL | 1.004 (1.003, 1.005) | < 0.001 | 1.00 (1.00, 1.00) | 0.904 |

| BUN, mg/dL | 1.04 (1.04, 1.05) | < 0.001 | 1.01 (1.00, 1.02) | 0.054 |

| eGFR, mL/min/1.73 m2 | 0.98 (0.98, 0.98) | < 0.001 | 0.99 (0.98, 0.99) | < 0.001 |

| Protein, g/dL | 0.68 (0.60, 0.77) | < 0.001 | 1.05 (0.83, 1.33) | 0.672 |

| Albumin, g/dL | 0.49 (0.42, 0.57) | < 0.001 | 0.97 (0.70, 1.33) | 0.831 |

| Uric acid, mg/dL | 1.37 (0.32, 1.42) | < 0.001 | 1.36 (1.30, 1.42) | < 0.001 |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dL | 0.99 (0.99, 1.00) | < 0.001 | 1.00 (1.00, 1.00) | 0.657 |

| Total bilirubin, mg/dL | 1.28 (1.05, 1.56) | 0.014 | 1.10 (0.84, 1.43) | 0.491 |

| AST, mg/dL | 1.01 (1.00, 1.01) | < 0.001 | 1.01 (1.00, 1.01) | < 0.001 |

| ALT, mg/dL | 1.00 (1.00, 1.00) | 0.103 | ||

| CRP, mg/dL | 1.02 (1.01, 1.04) | 0.005 | 1.01 (0.99, 1.03) | 0.453 |

| History of hypertension | 1.28 (1.02, 1.61) | 0.033 | 0.83 (0.60, 1.14) | 0.250 |

| History of diabetes | 1.80 (1.39, 2.33) | < 0.001 | 1.30 (0.90, 1.85) | 0.162 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 1.92 (1.12, 3.29) | 0.018 | 1.13 (0.56, 2.27) | 0.738 |

| Cardiovascular disease | 1.93 (1.05, 3.54) | 0.034 | 1.02 (0.49, 2.12) | 0.964 |

| Obstructive pulmonary disease | 0.87 (0.45, 1.66) | 0.668 | ||

| Acute kidney injury requiring KRT | 5.21 (2.00, 13.53) | < 0.001 | 0.53 (0.15, 1.88) | 0.328 |

Model 1: Unadjusted.

Model 2: Adjusted with variable with P < 0.05 in Model 1.

WBC, white blood cell; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; CRP, C-reactive protein; KRT, kidney replacement therapy; OR, odds ratio; aOR, adjusted odds ratip; CI, confidence interval.

The overall distribution of acid–base status

A total of 350 patients underwent arterial blood gas analysis on their date of admission. Mean partial pressure of CO2 (PaCO2) and tCO2 were 35.2 ± 6.0 mmHg and 25.3 ± 3.9 mmHg, respectively (Table S3). According to the tCO2 22 mmol/L, there was an insignificant difference in pH and partial pressure of oxygen (PaO2), but PaCO2, tCO2, and bicarbonate (HCO3) were significantly lower in patients with tCO2 ≤ 22 mmol/L. More than half of the patients (54.8%) showed alkalemia with pH ≥ 7.45. However, there were only 4 (1.1%) and 11 (3.2%) patients with pH ≥ 7.60 and pH < 7.35, respectively. Patients with alkalemia showed higher PaO2, lower PaCO2, and higher HCO3 than patients with normal pH (Table S4). The proportion of patients with tCO2 ≤ 22 mmol/L was lowest in patients with alkalemia. The correlation between changes in PaCO2 and HCO3 showed the proper compensation response to acid–base imbalance (Fig. S3). Among the 49 subjects with normal pH with HCO3 ≤ 24 mmol/L, the mean values of decreased tCO2 and PaCO2 were 3.8 mmol/L and 7.5 mmHg, respectively.

Discussion

In the present study, a decreased level of tCO2, which is easily detected using serum samples, was found to be a significant risk factor for mortality. The mortality risk increased incrementally from the traditional cutoff level of tCO2 ≤ 22 mmol/L. Additionally, the level of tCO2 ≤ 24 mmol/L, which was confirmed by a generalized additive model, showed similar results. We found that increased inflammatory markers, and dysfunction in major organs, such as the kidneys and liver, were associated with decreased tCO2.

Metabolic acidosis is a risk factor for mortality, especially in critically ill patients1,15. Because of the variety of baseline conditions, it was challenging to identify the relationship between the type of acidosis and outcomes. In this regard, serum bicarbonate is commonly used as a variable representing acidosis status and mortality risk16. Considering the more convenient approach and excellent correlation with serum bicarbonate, tCO2 is widely used for monitoring acidosis status8. However, it needs to be a caveat concerning the interpretation of an isolated measurement. We suggest that the low levels of tCO2 were as a result of either metabolic acidosis or compensation for respiratory alkalosis.

Acid–base disorders are common in patients with COVID-1917, and the most frequently reported form is respiratory and metabolic alkalosis, especially in patients with a severe form of COVID-1917,18. Respiratory and metabolic alkalosis could be related to the disease characteristics of the respiratory infectious disease. Nevertheless, a severe form of metabolic acidosis was also linked to worse outcomes in terms of the cytokine storm, which contributes to the mortality of COVID-1919. In addition, a higher level of lactate, one of the major sources of metabolic acidosis, was significantly related to increased mortality in patients with COVID-1920. However, following the trends of increased prevalence and decreased case-fatality rate worldwide, a specific approach would be warranted to identify the factors with the ability to predict worse outcomes in patients with COVID-19 showing mild to moderate severity. In this regard, the present study determined the impact of lower tCO2 on in-hospital mortality for patients with mild to moderate COVID-19 and a susceptible pH level.

Metabolic acidosis may be indicative of infectious status, significant organ damage, and worsened clinical characteristics21–23. Higher WBC counts, CRP levels, and extended hospital stays were associated with the severity of infectious disease. In addition, decreased calcium, elevated creatinine, decreased eGFR, and elevated AST and ALT may be associated with impaired kidney and liver function. In the same context, a higher prevalence of comorbidities such as hypertension, diabetes, cerebrovascular disease, and cardiovascular disease could be considered23. In this study, we also found that patients with lower tCO2 had worse clinical characteristics.

The kidneys have been generally reported as an organ inducing metabolic acidosis and an organ affected by metabolic acidosis. Metabolic acidosis significantly increases mortality risk, especially in patients with advanced CKD2,24. We previously reported that these hazardous effects of metabolic acidosis on graft and patient survival were maintained in kidney transplant recipients25. Although most patients had preserved kidney function in this study, those with lower tCO2 showed lower eGFR, and a lower level of eGFR was a factor associated with tCO2 ≤ 22 mmol/L. Lower hemoglobin and calcium were significant factors associated with lower tCO2. Though a definitive causal relationship between these variables and acidosis could not be determined, all of these variables are closely related to kidney function status; therefore, a comprehensive approach including kidney function status would be required to interpret the results.

In addition to the kidney and lungs, the liver is a critical acid–base regulation organ26. Based on its role in lactate metabolism, ketogenesis, albumin synthesis, and urea production27, severe liver damage could be linked to metabolic acidosis28. In this study, 3.4% and 3.4% of patients showed AST and ALT over 3 times the upper normal limit, respectively. We found a significant negative association between the level of AST and tCO2. There was no statistical significance, but bilirubin also showed a negative association with tCO2. Considering the severity of the status of the included patients, it would be warranted to monitor major organ dysfunction and the status of acid–base disorder.

Although the lockdown has ended, the COVID-19 epidemic has continued. Acid–base imbalance could be regulated and managed; thus, evaluating and monitoring the acid–base status as a significant factor associated with mortality is essential. Considering the straightforward approach of assessing acid–base balance based on the single measure of tCO2, this study has the strength of suggesting unique and helpful guidance for general populations with mild-to-moderate severity COVID-19. However, there are several limitations to this study. First, this was a retrospective observational study. We could not figure out the exact causal association between each variable and acidosis status. In addition, it needs to consider the recall bias during the process of recruiting the diagnosis information. Second, we could not differentiate the detailed status of acid–base balance, including the compensation status. It is not a routine process to measure arterial blood gas; therefore, we could not fully obtain the data of all the variables, such as pH, PaCO2, and PaO2. Third, although COVID-19 infection is a respiratory infection, we did not consider respiratory alkalosis or distress because of the small number of patients requiring oxygen supply or mechanical ventilation in this study. Fourth, we analyzed the significance of tCO2 on mortality in only patients with COVID-19 infection. Therefore, we suggest that these results only applied to patients with COVID-19, not to compare the patients without COVID-19.

Decreased tCO2, especially in patients with tCO2 ≤ 22 mmol/L significantly increases the risk of mortality in patients with COVID-19 infection. Considering the socioeconomic burden of COVID-19 infection, identifying factors that can predict outcomes is helpful in distinguishing patients based on risk stratification. Evaluating and monitoring tCO2 based on a convenient approach could be an excellent method to predict mortality, especially in patients with mild-to-moderate severity COVID-19 infection.

Materials and methods

Study populations

We included subjects aged ≥ 18 years from two hospitals dedicated to COVID-19 treatment during February 2020 and September 2021. We excluded subjects with underlying end-stage kidney disease requiring KRT. Additionally, subjects without data on total CO2 value were excluded. All subjects were followed-up from the date of admission related to COVID-19 to discharge from the hospital. The type of discharge included discharge to home, transfer, and death.

Clinical parameters and data acquisition

We collected laboratory data from the admission date, including complete blood counts; serum calcium, phosphate, serum potassium, and glucose; blood urea nitrogen; creatinine; protein; albumin; total bilirubin; aspartate transferase; alanine transferase; uric acid; total cholesterol; CRP; and lactate. The eGFR was calculated using the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration equation. We collected acid–base parameters of tCO2 and bicarbonate in whole populations. Moreover, we obtained arterial blood gas analysis data including pH, PaO2, and PaCO2 from those who had results. We also obtained information on underlying comorbidities such as hypertension, diabetes, cerebrovascular disease, cardiovascular disease, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease based on the medication history and responses of the patients. We used tCO2 as an exposure variable, and a level of 23 mmol/L was regarded as a lower limit of the normal range29. The primary outcome was all-cause mortality during hospitalization.

Sensitivity analysis

We additionally evaluated acid–base status in subjects according to arterial blood gas analysis. We divided the patients into three groups depending on the level of pH: < 7.35, ≥ 7.35 and < 7.45, and ≥ 7.5. The distribution of PaO2, PaCO2, bicarbonate, and tCO2 were evaluated according to pH.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are presented as the mean and standard deviation (SD). Categorical variables are shown as a number with a percentage. To compare the two groups according to the level of tCO2, we used Student's t tests and chi-square tests. We performed a Cox proportional hazard analysis to identify the impact of tCO2 on all-cause mortality. We used logistic regression analysis to determine the factors associated with decreased tCO2. In the multivariate analysis, we adjusted these variables, including age, sex, comorbidities, and laboratory findings, including WBC counts, hemoglobin, platelets, serum calcium, glucose, albumin, eGFR, and CRP. We used a generalized additive model to identify the association of tCO2 with increased risk of all-cause mortality. P values < 0.05 were defined as significant when they were two-sided. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (version 23.0; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

Ethical consideration

This study was conducted after approval by the institutional review board of Seoul National University Boramae Medical Center (IRB No 20–2021-88). The study was performed in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. All of the clinical information was extracted by retrospective review, and informed consent was waived by the institutional review board of Seoul National University Boramae Medical Center (IRB No 20–2021-88).

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the participating patients and clinical research coordinators for their contribution.

Author contributions

The principal investigator was J.P.L. Study proposal and design was conducted by Y.K. Acquisition, analysis or interpretation of data was performed by S.K, J.L, C.H, S.Y, and B.K. Statistical analysis was performed by Y.K and S.K. Study protocol was reviewed by K.J, S.H, D.K.K, and J.P.L. Material and technical supports were driven from S.K and J.L. Each author contributed important intellectual content during manuscript drafting or revision and accepts accountability for the overall work by ensuring that questions pertaining to the accuracy or integrity of any portion of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Funding

This study was supported by grant number '0320220340' from the SNUH research fund.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-023-41988-4.

References

- 1.Gunnerson KJ, Saul M, He S, Kellum JA. Lactate versus non-lactate metabolic acidosis: A retrospective outcome evaluation of critically ill patients. Crit. Care. 2006;10:R22. doi: 10.1186/cc3987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Raikou VDMP. Metabolic acidosis status and mortality in patients on the end stage of renal disease. J. Transl. Int. Med. 2016;4:170–177. doi: 10.1515/jtim-2016-0036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lo KB, Garvia V, Stempel JM, Ram P, Rangaswami J. Bicarbonate use and mortality outcome among critically ill patients with metabolic acidosis: A meta analysis. Heart Lung. 2020;49:167–174. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2019.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim, D. W. et al. Hospital mortality and prognostic factors in critically ill patients with acute kidney injury and cancer undergoing continuous renal replacement therapy. Kidney Res. Clin. Pract. (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Mitchell JH, Wildenthal K, Johnson RL., Jr The effects of acid-base disturbances on cardiovascular and pulmonary function. Kidney Int. 1972;1:375–389. doi: 10.1038/ki.1972.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kellum JA, Song M, Li J. Science review: extracellular acidosis and the immune response: Clinical and physiologic implications. Crit. Care. 2004;8:331–336. doi: 10.1186/cc2900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Castro, D., Patil, S. M. & Keenaghan, M. in StatPearls (StatPearls Publishing LLC., 2022).

- 8.Hirai K, et al. Approximation of bicarbonate concentration using serum total carbon dioxide concentration in patients with non-dialysis chronic kidney disease. Kidney Res. Clin. Pract. 2019;38:326–335. doi: 10.23876/j.krcp.19.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim Y, et al. First snapshot on behavioral characteristics and related factors of patients with chronic kidney disease in South Korea during the COVID-19 pandemic (June to October 2020) Kidney Res. Clin. Pract. 2022;41:219–230. doi: 10.23876/j.krcp.21.065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rajgor DD, Lee MH, Archuleta S, Bagdasarian N, Quek SC. The many estimates of the COVID-19 case fatality rate. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2020;20:776–777. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30244-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bertsimas D, et al. COVID-19 mortality risk assessment: An international multi-center study. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0243262. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0243262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chebotareva N, et al. Acute kidney injury and mortality in coronavirus disease 2019: results from a cohort study of 1,280 patients. Kidney Res. Clin. Pract. 2021;40:241–249. doi: 10.23876/j.krcp.20.128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nechipurenko, Y. D. et al. The role of acidosis in the pathogenesis of severe forms of COVID-19. Biology (Basel)10 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Wu C, et al. Risk factors associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome and death in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 Pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA Intern. Med. 2020;180:934–943. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.0994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Broder G, Weil MH. Excess lactate: An index of reversibility of shock in human patients. Science. 1964;143:1457–1459. doi: 10.1126/science.143.3613.1457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kovesdy CP, Anderson JE, Kalantar-Zadeh K. Association of serum bicarbonate levels with mortality in patients with non-dialysis-dependent CKD. Nephrol. Dial. Transpl. 2009;24:1232–1237. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfn633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alfano G, et al. Acid base disorders in patients with COVID-19. Int. Urol. Nephrol. 2022;54:405–410. doi: 10.1007/s11255-021-02855-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chiumello, D. et al. Acid-base disorders in COVID-19 patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome. J. Clin. Med.11 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Chhetri S, et al. A fatal case of COVID-19 due to metabolic acidosis following dysregulate inflammatory response (cytokine storm) IDCases. 2020;21:e00829. doi: 10.1016/j.idcr.2020.e00829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Booth AL, Abels E, McCaffrey P. Development of a prognostic model for mortality in COVID-19 infection using machine learning. Mod. Pathol. 2021;34:522–531. doi: 10.1038/s41379-020-00700-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maciel AT, Noritomi DT, Park M. Metabolic acidosis in sepsis. Endocr. Metab. Immune Disord. Drug Targets. 2010;10:252–257. doi: 10.2174/187153010791936900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ravikumar NPG, Pao AC, Raphael KL. Acid-mediated kidney injury across the spectrum of metabolic acidosis. Adv. Chronic Kidney Dis. 2022;29:406–415. doi: 10.1053/j.ackd.2022.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kimmoun A, Novy E, Auchet T, Ducrocq N, Levy B. Hemodynamic consequences of severe lactic acidosis in shock states: from bench to bedside. Crit. Care. 2015;19:175. doi: 10.1186/s13054-015-0896-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Raphael KL, Wei G, Baird BC, Greene T, Beddhu S. Higher serum bicarbonate levels within the normal range are associated with better survival and renal outcomes in African Americans. Kidney Int. 2011;79:356–362. doi: 10.1038/ki.2010.388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Park S, et al. Metabolic acidosis and long-term clinical outcomes in kidney transplant recipients. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2017;28:1886–1897. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2016070793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cohen RD. Roles of the liver and kidney in acid-base regulation and its disorders. Br. J. Anaesth. 1991;67:154–164. doi: 10.1093/bja/67.2.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Scheiner B, et al. Acid-base disorders in liver disease. J. Hepatol. 2017;67:1062–1073. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2017.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Funk GC, et al. Acid-base disturbances in critically ill patients with cirrhosis. Liver Int. 2007;27:901–909. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2007.01510.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kraut JA, Madias NE. Re-evaluation of the normal range of serum total CO(2) concentration. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2018;13:343–347. doi: 10.2215/CJN.11941017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.