ABSTRACT.

Mass drug administration (MDA) is a key strategy for the control of soil-transmitted helminths (STHs). Within MDA programs, poor and non-random compliance threaten successful control of STHs. A case-control study was conducted comparing perceptions among non-compliant participants with compliant participants during a community-wide MDA (cMDA) with albendazole in southern India. Common reasons cited for non-compliance were that the individual was not infected with STH (97.4%), the perception that he/she was healthy (91%), fear of side-effects (12.8%), and dislike of consuming tablets (10.3%). Noncompliance was associated with poor awareness of intestinal worms (odds ratio [OR]: 9.63, 95% CI: 2.11–43.84), the perception that cMDA was only required for those with worms (OR: 2.14, 95% CI: 1.06–4.36), and the perception that the drug is not safe during pregnancy (OR: 2.19, 95% CI: 1.18–4.07) or when on concomitant medications (OR: 3.14, 95% CI: 1.38–7.15). Understanding of perceptions driving noncompliance can provide valuable insights to optimize participation during MDA for STHs.

In India, ongoing mass drug administration (MDA) programs for neglected tropical diseases include lymphatic filariasis (LF; currently in 256 districts in 21 states) and soil-transmitted helminths (STHs; National Deworming Day programs).1 A systematic review of India’s LF MDA program revealed a large coverage-compliance gap, with compliance rates ranging between 20.8% and 93.7%, with an effective compliance of ≥ 65% being reported in just 10 of the 31 rounds of MDA.2 Both programmatic as well as individual-level factors have been shown to influence noncompliance to MDA.3 Fear of side effects and fear of adverse reactions were the predominant reasons associated with noncompliance to albendazole/diethylcarbamazine in LF programs implemented across various regions of India. Other factors included a lack of faith in or motivation to take the drug, concurrent illnesses, and misinformation conveyed because of inadequate community sensitization activities.4–8 A study from Nepal showed that compliance during LF MDA was associated with awareness of the treatment drug, side effects, and MDA campaigns and visits by healthcare workers.9 Another study in Tamil Nadu state in southern India reported significantly increased coverage and compliance in the LF program when a strict protocol that mandated three home visits by drug distributors was implemented.10

For STHs, targeted deworming of at-risk populations is the current WHO-recommended strategy for control of STHs and associated morbidities. Mathematical models suggest that high coverage community-wide MDA (cMDA), irrespective of age, gender, or socioeconomic status, may lead to interruption of STH transmission.11 The DeWorm3 study is a large cluster-randomized trial being conducted in three countries (Benin, India, and Malawi) to test the feasibility of cMDA versus school-based targeted deworming (albendazole delivered biannually) for interrupting transmission of STHs.12 To understand the perceptions associated with noncompliance to cMDA in the India DeWorm3 site, this case-control study was conducted during the second year of the trial, after the third of a total of six rounds of cMDA.

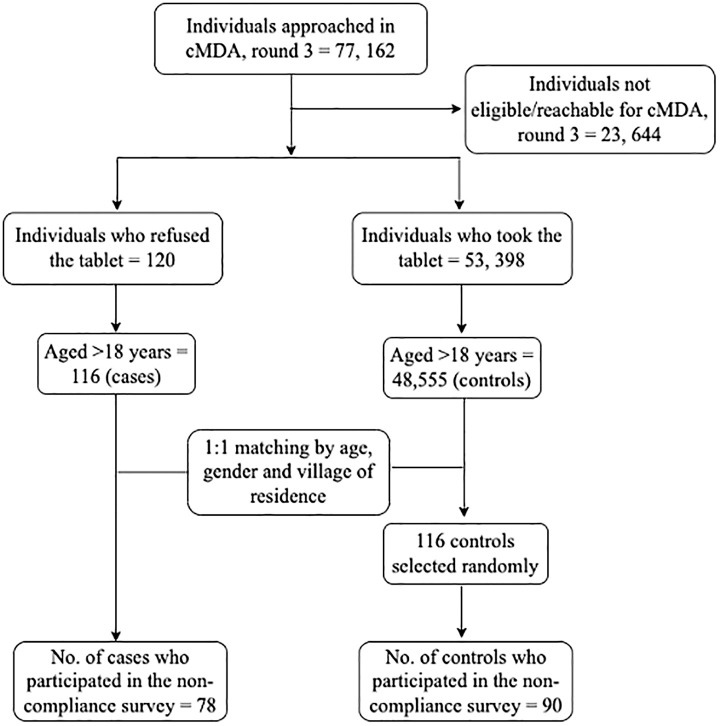

In India, the Deworm3 trial site is located in two blocks in the southern state of India in Tamil Nadu, namely Timiri, a rural block in the Ranipet district (formerly Vellore district), and Jawadhu Hills, a tribal block in the Tiruvannamalai district. The trial site was demarcated into 20 intervention and 20 control clusters, and the characteristics of the study population and prevalence of STHs in this community have been described earlier.13 The cMDA was directly observed treatment delivered house-to-house and during each round of cMDA; compliance and noncompliance to treatment of each individual who was eligible and available for treatment in the enumerated population were captured. A matched case-control study design (case: control = 1:1) with a sample size of 100 cases and 100 controls (imputing an expected odds ratio [OR] = 2.5, α = 0.05, β = 80%, 51% exposure) was used for conducting this survey on noncompliance (Figure 1). Noncompliant individuals (cases) and compliant individuals (controls) aged ≥ 18 years during cMDA round 3 (cMDA3) (who may or may not have been compliant in the previous two rounds of cMDA) and were available during all three cMDA rounds were included in the survey. Controls, matched for age, sex, and village of residence from the baseline census data conducted between December 2017 and February 2018 were selected by random sampling.

Figure 1.

Flowchart depicting the selection of cases and controls from the community-wide mass drug administration (cMDA), round 3, for the noncompliance survey.

A pilot-tested, semi-structured questionnaire was administered by three trained field research assistants in the local language (Tamil), and data were collected using an android-based mobile platform used for all Deworm3 surveys (SurveyCTO; Dobility, Inc., Cambridge, MA, and Ahmedabad, India).14 Fisher’s exact or χ2 tests were performed as appropriate to determine the association between noncompliance, and exposure variables and ORs with 95% CI were calculated from univariable logistic regression analyses.

The Deworm3 trial was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Christian Medical College, Vellore (CMC) [IRB Min No: 10,392] and the Human Subjects Division at the University of Washington (STUDY00000180). This analysis was approved as an amendment at CMC (A07-27.03.2019). The trial is registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT03014167). Written informed consent was obtained from the individuals participating in this survey.

During cMDA3 in February 2019, a total of 53,518 individuals out of 77,162 individuals in the intervention clusters were eligible or available to participate. Of these 77,162 individuals, 23,644 individuals could not be treated either because they were not eligible or available, and 120 individuals were documented as noncompliant to treatment (0.2%) (Figure 1). Most refusals to MDA (noncompliant) were in the Timiri block, with very few refusals documented in the Jawadhu Hills block (4/120). Of the 116 adult noncompliant individuals during cMDA3, 78 individuals (cases) spread across 15 intervention clusters consented to participate in this survey along with 90 matched compliant individuals (controls) (Figure 1). The median age of the participants in both groups was similar (case: median age = 44 years, interquartile range = 28.8–61.2 years and control: median age = 46 years, interquartile range = 29.1–59 years). The proportion of males and females among the cases and controls was also comparable (Table 1). More than 80% of the interviews were administered at the participants’ place of residence, and this was documented to determine whether the interviewees, specifically the noncompliant individuals, were comfortable in their home environment and were able to respond without any external influence during the interview. About 37% of the noncompliant individuals belonged to a higher socioeconomic quintile (> 5), whereas 44% of the compliant individuals belonged to lower socioeconomic quintiles (3 and 4). A majority of both noncompliant (94%) and compliant (92%) individuals were aware that the deworming tablet was distributed to everyone in the community during the DeWorm3 cMDA to ensure individuals are healthy or to eliminate worms.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of participants who took part in the noncompliance survey (N = 168)

| Characteristic | Cases (noncompliant, N = 78) n (%) |

Controls (compliant, N = 90) n (%) |

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age group | 18–24 years | 13 (16.7) | 14 (15.6) | 0.97 |

| 25–34 years | 20 (25.6) | 22 (24.4) | ||

| 35–44 years | 8 (10.3) | 8 (8.9) | ||

| > 45 years | 37 (47.4) | 46 (51.1) | ||

| Gender | Male | 38 (48.7) | 44 (48.9) | 0.98 |

| Female | 40 (51.3) | 46 (51.1) | ||

| Socioeconomic quintile*† | 1–2 | 21 (28) | 14 (15.9) | 0.15 |

| 3–4 | 26 (34.7) | 39 (44.3) | ||

| > 5 | 28 (37.3) | 35 (39.8) | ||

Quintiles, where 1 = Low and 5 = High (the wealth index was assessed using quintiles derived from household assets using principal component analysis as described elsewhere.13

Data not available for three cases and two controls.

The reasons for noncompliance included 1) feeling that they were not infected with STHs (97.4%); 2) being apparently healthy (91%); 3) fear of side effects due to the albendazole tablet distributed during the cMDA (12.8%) or because of underlying health conditions or being on concomitant medications (15.4%); 4) dislike of consuming tablets (10.3%); and 5) pregnancy or breastfeeding at the time of cMDA (7.7%) (Supplemental Table 1). About one-third of noncompliant individuals (37%) and a quarter of compliant individuals (25%) were on regular medication at the time of the survey. A higher proportion of noncompliant individuals (16%) had a history of an unpleasant experience after consuming any medication compared with compliant individuals (11%).

Factors significantly associated with noncompliance were 1) not having consumed deworming medications in the past (OR: 8.94, 95% CI: 1.95–40); 2) being unaware of what intestinal worms are (OR: 9.63, 95% CI: 2.11–43.84); and 3) a perception that it was unsafe to consume deworming tablets during a range of conditions such as 1) while not having worms (OR: 2.14, 95% CI: 1.06–4.36); 2) during pregnancy (OR: 2.19, 95% CI: 1.18–4.07); 3) while on concomitant medications (OR: 3.14, 95% CI: 1.38–7.15); 4) having skin allergies (OR: 2.46, 95% CI: 1.31–4.60); 5) consuming traditional medicines (OR: 2, 95% CI: 1.06–3.79); 6) having chronic conditions such as heart disease, diabetes, or hypertension (OR: 3.97, 95% CI: 2.07–7.63); and 7) having undergone recent surgery (OR: 2.14, 95% CI: 1.16–3.97) (Table 2). With reference to questions that were administered specifically to the women who participated in the survey (N = 86; cases = 40 and control = 46), 75% of noncompliant women and 61% of compliant women either did not know that it was safe or believed that it was unsafe for women to consume deworming tablets during menstruation (not significant). Some of them also believed that vaginal discharge could increase by consuming deworming tablets (25% of noncompliant women and 33% of compliant women; not significant).

Table 2.

Awareness and perceptions about STHs and cMDA among compliant and noncompliant participants

| Question | Response | Cases (noncompliant, N = 78), n (%) | Controls (compliant, N = 90), n (%) | Logistic regression | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P value | ||||

| Have you ever taken any tablets in the past? | No | 13 (16.7) | 2 (2.2) | 8.94 (1.95–40) | 0.005 |

| Yes | 65 (83.3) | 88 (97.8) | |||

| If yes, did you take/do you take the tablets that you mentioned regularly? | No | 41 (63.1) | 66 (75) | 0.57 (0.28–1.14) | 0.114 |

| Yes | 24 (36.9) | 22 (25) | |||

| Have you had any unpleasant experience/s with the tablets you mentioned in the past? | No | 55 (84.6) | 78 (88.6) | 0.71 (0.27-1.81) | 0.477 |

| Yes | 10 (15.4) | 10 (11.4) | |||

| Do you know what intestinal worms are? | No/does not know | 14 (17.9) | 2 (2.2) | 9.63 (2.11–43.84) | 0.003 |

| Yes | 64 (82.1) | 88 (97.8) | |||

| Why do you think a deworming tablet was given to everyone in the village? | For all to be healthy/eliminate worms | 72 (92.3) | 85 (94.4) | 1.41 (0.42–4.84) | 0.578 |

| Other/does not know | 6 (7.7) | 5 (5.6) | |||

| Do you think a person who does not have worms can still take the deworming tablet? | No/does not know | 26 (33.3) | 17 (18.9) | 2.14 (1.06–4.36) | 0.034 |

| Yes | 52 (66.7) | 73 (81.1) | |||

| Do you think the deworming tablet distributed to everyone has any side effects? | No/does not know | 65 (83.3) | 82 (91.1) | 2.05 (0.80–5.24) | 0.134 |

| Yes | 13 (16.7) | 8 (8.9) | |||

| What do you think about the quality of the deworming tablets? | Bad quality/does not know | 15 (19.2) | 9 (10) | 2.14 (0.88–5.21) | 0.093 |

| Good quality | 63 (80.8) | 81 (90) | |||

| Is it all right for a pregnant woman to take the deworming tablet? | No/does not know | 48 (61.5) | 38 (42.2) | 2.19 (1.18–4.07) | 0.013 |

| Yes | 30 (38.5) | 52 (57.8) | |||

| Is it all right for a woman to take the deworming tablet while breastfeeding? | No/does not know | 32 (41) | 26 (28.9) | 1.71 (0.90–3.25) | 0.100 |

| Yes | 46 (59) | 64 (71.1) | |||

| Is it all right for someone taking any other medicine/s to take the deworming tablet? | No/does not know | 22 (28.2) | 10 (11.1) | 3.14 (1.38–7.15) | 0.006 |

| Yes | 56 (71.8) | 80 (88.9) | |||

| Is it all right for someone with a skin allergy to take the deworming tablet? | No/does not know | 43 (55.1) | 30 (33.3) | 2.46 (1.31–4.60) | 0.005 |

| Yes | 35 (44.9) | 60 (66.7) | |||

| Is it all right for someone allergic to allopathic (English) medicines to take the deworming tablet? | No/does not know | 47 (60.3) | 43 (47.8) | 1.66 (0.90–3.06) | 0.107 |

| Yes | 31 (39.7) | 47 (52.2) | |||

| Is it all right for someone taking traditional medicines (homeopathy, siddha, others) to take the deworming tablet? | No/does not know | 55 (70.5) | 49 (54.4) | 2 (1.06–3.79) | 0.034 |

| Yes | 23 (29.5) | 41 (45.6) | |||

| Can someone with heart disease/diabetes/hypertension, etc., take the deworming tablet? | No/does not know | 45 (57.7) | 23 (25.6) | 3.97 (2.07–7.63) | < 0.001 |

| Yes | 33 (42.3) | 67 (74.4) | |||

| Is it all right for someone who recently underwent surgery to take the deworming tablet? | No/does not know | 45 (57.7) | 35 (38.9) | 2.14 (1.16–3.97) | 0.016 |

| Yes | 33 (42.3) | 55 (61.1) | |||

| Is it all right for someone who is generally feeling unwell to take the deworming tablet? | No/does not know | 32 (41) | 26 (28.9) | 1.71 (0.90–3.25) | 0.100 |

| Yes | 46 (59) | 64 (71.1) | |||

| Is it all right to take the deworming tablet on an empty stomach? | No/does not know | 55 (70.5) | 65 (72.2) | 0.92 (0.47–1.80) | 0.807 |

| Yes | 23 (29.5) | 25 (27.8) | |||

| Is it all right for old people to take the deworming tablet? | No/does not know | 21 (26.9) | 16 (17.8) | 1.70 (0.82–3.56) | 0.156 |

| Yes | 57 (73.1) | 74 (52.2) | |||

| Is it all right to take the deworming tablet distributed in the village without a doctor’s advice? | No/does not know | 45 (57.7) | 40 (44.4) | 1.70 (0.92–3.14) | 0.088 |

| Yes | 33 (42.3) | 50 (55.6) | |||

| Is it all right for someone under the influence of alcohol to take this deworming tablet? | No/does not know | 75 (96.2) | 83 (92.2) | 2.11 (0.55–8.45) | 0.342 |

| Yes | 3 (3.8) | 7 (7.8) | |||

| Questions asked only of women (cases, N = 40; controls, N = 46) | |||||

| Is it all right for a woman to take this deworming tablet when she is menstruating? | No/does not know/do not want to answer | 30 (75) | 28 (60.9) | 1.93 (0.76–4.88) | 0.166 |

| Yes | 10 (25) | 18 (39.1) | |||

| Do you think white discharge (vaginal) will increase if a woman takes this deworming tablet | No/I don’t know | 30 (75) | 31 (67.4) | 1.45 (0.56–3.73) | 0.439 |

| Yes | 10 (25) | 15 (32.6) | |||

cMDA = community-wide mass drug administration; OR = odds ratio; STHs = soil-transmitted helminths.

Bold values represent significant values at P < 0.05.

Our study had a few limitations. The survey adopted a careful approach to exclude open-ended questions to ensure participation of noncompliant individuals, but this may have limited the potential to elicit more in-depth information around noncompliance. Some of the general questions on awareness of STHs and prior deworming that are nonspecific to perceptions associated with noncompliance had wide CIs that could be attributed to the small sample size of this study. Interactions of participants with deworming providers may also be a factor influencing compliance that was not explored in this study. However, government stakeholder perspectives on MDA collected as part of the parent trial (Deworm3) indicated that availability of high-quality, tailored sensitization materials and human and material resources would be essential for implementing cMDA.15

In the DeWorm3 trial, the strategy of house-to-house cMDA delivery provided an opportunity for interpersonal communication with noncompliant individuals (0.2% of the study population) spread across almost three-quarters of the study clusters. This survey delineates perceptions among those noncompliant with cMDA for STHs in this community and provides insights that could help address challenges in the larger national cMDA programs for STHs in the Indian context. Previous studies from India have focused on noncompliance in LF MDA programs with little to no information on STH programs.2–6 The perceptions that healthy individuals should not participate in cMDA and that the drug distributed in cMDA was not safe to take in conditions such as pregnancy or in those with concomitant conditions such as heart disease, hypertension, or diabetes were the most important factors associated with noncompliance in the cMDA. Similar findings have also been shown in other studies.16,17 In this survey, > 90% of noncompliant individuals felt there was no need to take albendazole as they had no worms and were apparently healthy. Similar to observations during the LF MDA programs in India, fear of side effects from albendazole, either directly or associated with underlying health conditions or concomitant medications, was a common reason for treatment refusal in this survey.18,19 Findings from Egypt and Sri Lanka showed that reasons for noncompliance to MDA included not feeling the need for treatment, the fear of adverse effects, pregnancy or breastfeeding, being on concomitant medications, or having forgotten to take the drug.16,20 Treatment compliance was associated with the perception that deworming is safe. Overall, messages stressing the safety of deworming should be included in community sensitization messages to help improve compliance to STH cMDA in similar settings in India and other countries.

Supplemental Materials

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Gokila Palanisamy, Naveenkumar Sekar, Angelin Titus, Yesudoss Jacob, and Jabaselvi Johnson for their support in data collection. We thank their field managers and field supervisors and field workers at the DeWorm3 study site in India for logistical support during data collection activities in the field. We also acknowledge the work of all members of the DeWorm3 study teams and affiliated institutions. We acknowledge the support of the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Delhi and the Directorate of Public Health, Chennai for their support of the DeWorm3 study. We thank all of the study participants, communities, and community leaders who have participated or supported the DeWorm3 study.

Note: Supplemental material appears at www.ajtmh.org.

REFERENCES

- 1. National Vector Borne Disease Control Programme, Directorate General of Health Services, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India , 2018. Accelerated Plan for the Elimination of Lymphatic Filariasis. Available at: https://nvbdcp.gov.in/WriteReadData/l892s/1031567531528881007.pdf. Accessed May 6, 2023.

- 2. Babu BV, Babu GR, 2014. Coverage of, and compliance with, mass drug administration under the programme to eliminate lymphatic filariasis in India: a systematic review. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 108: 538–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Shuford KV, Turner HC, Anderson RM, 2016. Compliance with anthelmintic treatment in the neglected tropical diseases control programmes: a systematic review. Parasit Vectors 9: 29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kumar A, Kumar P, Nagaraj K, Nayak D, Ashok L, Ashok K, 2009. A study on coverage and compliance of mass drug administration programme for elimination of filariasis in Udupi district, Karnataka, India. J Vector Borne Dis 46: 237–240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ghosh S, Samanta A, Kole S, 2013. Mass drug administration for elimination of lymphatic filariasis: recent experiences from a district of West Bengal, India. Trop Parasitol 3: 67–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Babu BV, Mishra S, 2008. Mass drug administration under the programme to eliminate lymphatic filariasis in Orissa, India: a mixed-methods study to identify factors associated with compliance and non-compliance. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 102: 1207–1213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Patel PK, 2012. Mass drug administration coverage evaluation survey for lymphatic filariasis in Bagalkot and Gulbarga Districts. Indian J Community Med 37: 101–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Haldar A, Dasgupta U, Ray RP, Jha SN, Haldar S, Bhattacharya SK, 2013. Critical appraisal of mass DEC compliance in a district of west Bengal. J Commun Dis 45: 65–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Adhikari RK. et al. , 2014. Factors determining non-compliance to mass drug administration for lymphatic filariasis elimination in endemic districts of Nepal. J Nepal Health Res Counc 12: 124–129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Nandha B, Krishnamoorthy K, Jambulingam P, 2013. Towards elimination of lymphatic filariasis: social mobilization issues and challenges in mass drug administration with anti-filarial drugs in Tamil Nadu, South India. Health Educ Res 28: 591–598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Anderson R, Truscott J, Hollingsworth TD, 2014. The coverage and frequency of mass drug administration required to eliminate persistent transmission of soil-transmitted helminths. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 369: 20130435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ásbjörnsdóttir KH. et al. , 2018. Assessing the feasibility of interrupting the transmission of soil-transmitted helminths through mass drug administration: the DeWorm3 cluster randomized trial protocol. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 12: e0006166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ajjampur SS. et al. , 2012. Epidemiology of soil transmitted helminths and risk analysis of hookworm infections in the community: results from the DeWorm3 Trial in southern India. PloS Negl Trop Dis 15: e0009338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Oswald WE. et al. , 2020. Development and application of an electronic treatment register: a system for enumerating populations and monitoring treatment during mass drug administration. Glob Health Action 13: 1785146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Roll A. et al. , 2022. Policy stakeholder perspectives on barriers and facilitators to launching a community-wide mass drug administration program for soil-transmitted helminths. Glob Health Res Policy 7: 1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Abd Elaziz KM, El-Setouhy M, Bradley MH, Ramzy RMR, Weil GJ, 2013. Knowledge and practice related to compliance with mass drug administration during the Egyptian National Filariasis Elimination Program. Am J Trop Med Hyg 89: 260–264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Dicko I, Coulibaly YI, Sangaré M, Sarfo B, Nortey PA, 2020. Non-compliance to mass drug administration associated with the low perception of the community members about their susceptibility to lymphatic filariasis in Ankobra, Ghana. Infect Disord Drug Targets 20: 167–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Roy RN, Sarkar AP, Misra R, Chakroborty A, Mondal TK, Bag K, 2013. Coverage and awareness of and compliance with mass drug administration for elimination of lymphatic filariasis in Burdwan District, West Bengal, India. J Health Popul Nutr 31: 171–177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Nujum ZT, 2011. Coverage and compliance to mass drug administration for lymphatic filariasis elimination in a district of Kerala, India. Int Health 3: 22–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Weerasooriya MV, Yahathugoda CT, Wickramasinghe D, Gunawardena KN, Dharmadasa RA, Vidanapathirana KK, Weerasekara SH, Samarawickrema WA, 2007. Social mobilisation, drug coverage and compliance and adverse reactions in a Mass Drug Administration (MDA) Programme for the Elimination of Lymphatic Filariasis in Sri Lanka. Filaria J 6: 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.