Abstract

Late-onset Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia (PCP) can be developed in solid organ transplant (SOT) patients. Granulomatous P. jirovecii pneumonia (GPCP) can occur in immunocompromised patients, but has rarely been reported in SOT recipients. The diagnosis of GPCP is difficult since the sensitivity of sputum and bronchoalveolar lavage is low and atypical patterns are shown. A 60-year-old man, who had undergone renal transplantation 24 years ago presented with nodular and patchy lung lesions. He was asymptomatic and stable. After empirical treatment with a fluoroquinolone, the condition partially resolved but relapsed 4 months later. The pulmonary nodule was resected, and GPCP was confirmed. The pathogenesis of GPCP remains unclear, but in SOT recipients presenting with an atypical lung pattern, GPCP should be considered. This case was discussed at the Grand Clinical Ground of the Korean Society of Infectious Disease conference on November 3, 2022.

Keywords: Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia, Granulomatous PCP, Solid organ transplantation

Introduction

Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia (PCP) is an opportunistic fungal infection caused by P. jirovecii in immunocompromised individuals. The fatality rate of infection is significantly high, and without treatment, the disease progresses rapidly in patients [1]. PCP is associated with intensified immunosuppression, including high-dose corticosteroids, which is often administered in the early period after organ transplantation [2]. Therefore, PCP prophylaxis is recommended 6 - 12 months after solid organ transplantation (SOT) [3]. The radiological finding of PCP infection is bilateral interstitial infiltration with ground-glass opacities (GGO). However, atypical patterns, including focal infiltrates, nodules, cystic air spaces, and pleural effusions, depending on the overall status of immunosuppression, have also been reported [4]. Herein, we report a case of late-onset asymptomatic granulomatous PCP in a patient who underwent kidney transplantation.

1. Case report

A 60-year-old kidney transplanted man who visited a nephrology clinic every 2 months was referred to an infectious disease clinic because of an asymptomatic chest X-ray abnormality. He underwent living-donor kidney transplantation 24 years previously and was on immunosuppressive therapy with tacrolimus, sirolimus, and deflazacort. He was also diagnosed with chronic kidney disease, osteoporosis, post-transplant diabetes mellitus, and dyslipidemia. Medications included calcium supplements, calcitriol, allopurinol, folic acid, ferrous sulfate, sodium bicarbonate, linagliptin, atorvastatin, and rebamipide. He had received denosumab two months prior.

He worked as a pipefitter, but quit the job a year ago and now lives in Seoul, a metropolitan city in Korea. He is an ex-smoker with no known sick contacts or contact with infectious animals. The patient did not initially complain of any symptoms on review of systems. However, upon questioning, he admitted to a slight sore throat. On physical examination, the patient was afebrile with blood pressure 90/50 mmHg, heart rate 77 beats/min, and respiratory rate 18 breaths/min. Although oximetry was not performed, he did not present dyspnea or signs of hypoxemia on room air. He had a hemoglobin concentration of 9.7g/dL, white blood cell count of 6,000 × 103/mm3 (neutrophil percentage, 60.5%, and lymphocyte percentage, 26.7%), platelet count of 99 × 103/mm3, C-reactive protein level of 0.04 mg/dL, serum creatinine level of 2.2 mg/dL, and calcium level of 7.9 mg/dL (Table 1).

Table 1. Laboratory data.

| Blood test | Initial visit | Before wedge resection | Normal rangea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WBC, mm3 | 6,000 | 3,800 | 3,700 - 9,000 | |

| Neutrophil, % | 60.5 | 55.8 | 43 - 75 | |

| Lymphocyte, % | 26.7 | 31.5 | 24 - 45 | |

| Monocyte, % | 10.1 | 11.4 | 2 - 10 | |

| Hemoglobin, g/dL | 9.7 | 8.6 | 11 - 16 | |

| Platelets, /uL | 99 | 77 | 130 - 700 × 103 | |

| BUN, mg/dL | 37.4 | 29.3 | 7.3 - 20.5 | |

| Creatinine, mg/dL | 2.2 | 2.23 | 0.49 - 0.91 | |

| AST, U/L | 19 | 28 | 0 - 34 | |

| ALT, U/L | 29 | 35 | 0 - 46 | |

| Calcium, mg/dL | 7.9 | 7.4 | 8.6 - 10.2 | |

| Phosphate, mg/dL | 2.4 | 1.8 | 2.5 - 4.5 | |

| ESR, mm/hr | 22 | 11 | 1 - 20 | |

| CRP, mg/dL | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0 - 0.5 | |

| Parathyroid hormone | 34.21 | 18.9 | 15 - 65 | |

| 25 (OH) Vitamin D | 41.26 | Ns | Ns | |

aNormal range is based on the suggested value in the hospital.

Ns, non specificed.

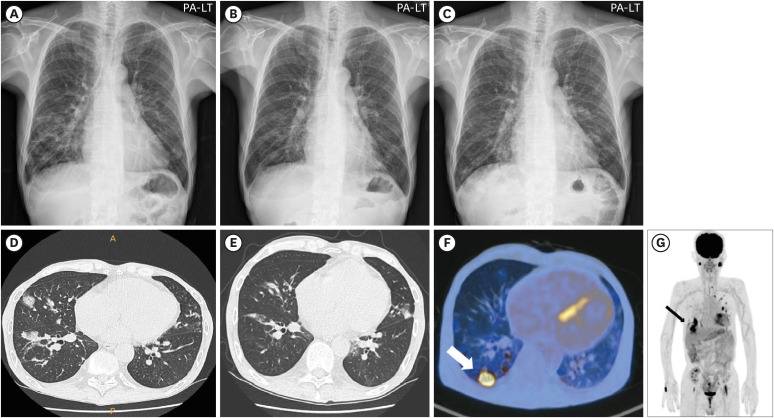

Radiography revealed multifocal nodular or patchy opacities in the bilateral middle and lower lung lobes (Fig. 1A). Chest computed tomography (CT) showed multiple nodular consolidations and GGO in both lungs, suggestive of organizing pneumonia (Fig. 1D). Blood and sputum cultures did not reveal any organism. Multiplex real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) panel for bacterial pathogens causing pneumonia, acid-fast bacilli staining, Mycobacterium PCR, and cytomegalovirus (CMV) immunoglobulin M were all negative. Since he did not reveal respiratory symptoms, Pneumocystis PCR, beta-D glucan, Aspergillus galactomannan, and Legionella antigen tests were not done. Under the suspicion of atypical pneumonia, empirical antibiotic therapy with moxifloxacin was initiated for 4 weeks. After a month, the previously observed nodular consolidations and GGO partially resolved, but new nodules were observed in both lungs (Fig. 1B and 1E). After four months of follow-up with chest CT and despite the absence of any other symptoms, newly appearing nodules or nodular consolidations were observed in both lungs, with a predominance in the lower lung (Fig. 1C for Chest X-ray; no Chest CT image provided).

Figure 1. Radiologic findings with granulomatous Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia (PCP). (A) Chest X-ray (CXR) showing multifocal opacities in bilateral lungs, (B) Follow-up CXR after empirical antibiotic treatment, (C) CXR 4 months after the treatment, (D) Chest computed tomography (CT) demonstrating multiple nodular consolidations, (E) Follow-up CT showing resolution of initial nodules, but the appearance of new nodules, (F) Follow-up CT revealing newly appearing numerous nodules in both lungs with relatively predominace in the lower lungs, (G, H) Positron emission tomography-CT (PET-CT) highlighting hypermetabolic lesions in both lungs, with notably high uptake in a right lower lung mass.

A black arrow in Figure 1G and a white arrow in Figure 1H indicate the lung mass where the histopathologic analyses were performed.

The patient was admitted to the hospital and underwent F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/CT. The right lower lung mass showed high uptake, which was highly suggestive of malignancy (Fig. 1F), and multiple hypermetabolic lesions were observed (Fig. 1G). To identify the etiology of the lung nodule, the patient underwent wedge resection of the right lateral basal segment via video-assisted thoracic surgery.

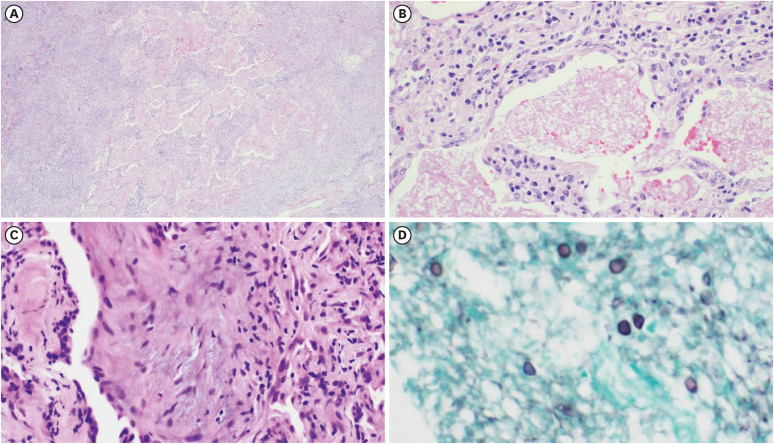

Tissue pathology revealed intra-alveolar foamy casts and multiple granulomas with necrosis. Gomori methenamine silver staining revealed a cystic form of the organism, suggestive of PCP (Fig. 2). Other infectious etiologies related to granulomatous reactions were assessed, and sputum cultures for bacteria, fungi were negative. The galactomannan antigen test from serum and mycobacteria PCR test from resected tissue were also negative. Pneumocystis PCR from sputum specimen was positive. After being diagnosed with granulomatous PCP (GPCP), the patient was started on trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP/SMX) as anti-PCP treatment. Due to acute kidney injury, the treatment was switched to clindamycin and primaquine for 7 days. However, he ultimately completed his treatment with TMP/SMX for a total 21 days. The lung lesions improved, and the patient maintained a healthy status in the outpatient clinic.

Figure 2. Histopathologic features of granulomatous PCP. (A, B) Intra-alveolar foamy alveolar casts (hematoxylin and eosin stain (H&E), ×40, ×200), (C) Multiple granulomas with necrosis (H&E, ×200), (D) Cystic form of organism in the intra-alveolar space (Gomori methenamine silver stain, ×400).

2. Ethics statement

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for the publication of this case report and the accompanying images. A copy of the written consent form is available for review upon request.

3. Minutes of the Clinical Grand Rounds on November 3, 2022

This case was discussed at the Grand Clinical Ground of the Korean Society of Infectious Disease (KSID) conference in 2022. The discussion began with the moderator’s inquiry to the panel about the pathogen causing the disease. Subsequently, the audience engaged in a free discussion on the implications of the case. The participants in the discussion are shown in Table 2, and the following are the minutes of the discussion:

Table 2. Participants in the clinical grand round discussion.

| Moderator |

| Sang-Oh Lee (University of Ulsan College of Medicine) |

| Case presenter |

| Yae Jee Baek (Soonchunhyang University College of Medicine) |

| Panelist |

| Dong-Gun Lee (College of Medicine, The Catholic University of Korea) |

| Young Hwa Choi (Ajou University School of Medicine) |

| Shin-Woo Kim (Kyungpook National University College of Medicine) |

| Audience |

| Sung-Han Kim (University of Ulsan College of Medicine) |

| Jun Yong Choi (Yonsei University College of Medicine) |

(1) What is the impression of pathogen causing pneumonia in this case?

Dong-Gun Lee: The patient was receiving immunosuppressants and presented with localized pneumonia with nodular and diffuse patterns. Microorganisms, such as fungi or Nocardia, can be considered due to the dominant presence of nodules. Viruses or Pneumocystis pneumonia could be responsible for the diffuse radiological patterns. Procedures such as bronchoscopy and percutaneous biopsy of lung lesions can be performed for diagnosis.

Young Hwa Choi: Because his occupation was a pipefitter, Legionella should also be included in the differential diagnosis, as the microorganism causes various patterns of occupational pneumonia.

Sin-Woo Kim: Considering host factors, atypical pathogens, such as Nocardia, Cryptococcus, and endemic fungi, can be traditionally considered.

Sung-Han Kim: Asymptomatic pneumonia is not commonly caused by Aspergillus species or PCP. Legionella or toxocariasis can be considered.

(2) What is the implication of this case?

Dong-Gun Lee: Compromised host with pneumonia requires prompt empirical intervention for diagnosis and treatment to improve survival.

Sung-Han Kim: I have seen only a few cases of PCP within 2 years of solid organ transplantation. I encountered nodular PCP in an acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) patient, but nodular PCP during an unusual timeline after transplantation was quite unexpected and interesting.

Sang-Oh Lee: Pneumocystis prophylaxis prevents PCP. However, after the prophylaxis is discontinued, the disease can occur in immunocompromised hosts.

Jun Yong Choi: PCP in AIDS patients develops with various manifestations, such as nodules, cavities, or pneumothorax. In addition, worsening of existing PCP can be associated with immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS).

Discussion

We report a case of late-onset GPCP in a patient who underwent kidney transplantation. Although its frequency has markedly decreased with widespread PCP prophylaxis, PCP can occur a year after SOT on immunosuppressants. The incidence of PCP is still 2.5 - 4.5% in SOT recipients [5,6]. The risk of PCP after transplantation without PCP prophylaxis can increase, particularly in SOT recipients with allogeneic rejection, CMV infection, and lymphopenia [2]. In a retrospective study, age (adjusted odds ratio [OR] 3.7, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.3 – 10.4), CMV infection (OR: 5.2, 95% CI: 1.8 – 14.7) and total lymphocyte count below 350 (OR: 3.9, 95% CI: 1.4 – 10.7) were found to be independently associated with late-onset PCP [7].

Although up to 65% of healthy adults may be colonized by the relatively ubiquitous P. jirovecii [8], the fungus can cause a severe form of pneumonia known as PCP in immunocompromised individuals. However, clinical manifestations can vary depending on the underlying disease. Patients with AIDS develop a more gradual onset of dyspnea and dry cough in PCP, while rapid progression and higher death rates have been noted in non-AIDS patients than in AIDS patients [9]. The patient in this case presented with mild, insidious symptoms. His nodular lung patterns, which did not respond to antibiotics, migrated in both lungs, complicating the diagnosis. Due to the atypical findings, PCP was not the initial suspicion, and therefore tests specific to it were not conducted. However, given the similarities in clinical symptoms and the nodular pattern, it is assumed that the condition was caused by the same microoraganism. In this context, GPCP occurring after SOT was not fatal. According to a cohort study in France, SOT was an independent variable associated with low mortality in patients with PCP compared to other causes of immunodeficiency (OR 0.08; 95% CI:0.02 – 0.31) [10]. However, according to a cohort study in Korea, SOT was frequently observed in the group that failed first-line treatment [11]. Another study indicated that a low CD4+ lymphocyte count was associated with morality in SOT patients with PCP, while patients presenting with the atypical pattern of PCP were less likely to experience mortality [12]. Therefore, the mechanisms and prognosis of PCP in patients with SOT should be further investigated.

A smaller subset of patients with PCP elicits a granulomatous response to P. jirovecii infection. GPCP is diagnosed when Pneumocystis organisms are present inside a granuloma, in the absence of other pathogens. Granuloma formation occurs in approximately 5% of PCP infections [13]. The granulomatous response is often represented as multiple distributed nodules on chest imaging, but different patterns including masses, diffuse infiltrates were also reported [14]. In addition, unlike classic PCP which is abundantly found within the alveoli, the diagnostic sensitivity of sputum and bronchoalveolar lavage for GPCP is low, possibly due to PCP encapsulation by the granuloma [15]. Therefore, invasive biopsy, including open surgery, is frequently performed.

There have been several reports of GPCP in patients with AIDS. Some patients with AIDS develop GPCP with an atypical presentation on PCP prophylaxis [16,17], whereas others are diagnosed with IRIS and consequently treated with corticosteroids [18]. There has been a case report of an AIDS patient who was diagnosed with nodular GPCP on their first visit without having started any medications [19]. A few cases of GPCP have been reported in patients with hematological malignancies. Some patients developed fever with progressive dyspnea [20,21,22], whereas others were asymptomatic [23,24,25]. Solitary or multiple nodules are observed in most cases. Granulomatous PCP in SOT recipients have rarely been reported. A summary of reported cases of granulomatous PCP in patients with transplants is presented in Table 3. To our knowledge, this is the fourth report of a granulomatous reaction to a PCP infection.

Table 3. Summary of reported cases of granulomatous Pneumocystis Jirovecii pneumonia (PCP) in solid organ transplanted patients.

| Year | Age/Sex | SOT | Granulomatous PCP onset after transplantation | Immunosuppressant | Symptoms | Radiological findings | PCP PCR | Confirmation | Hypercalcemia | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1975 | F/37 | KT | 7 months, rejection, no prophylaxis | Azathioprine, prednisone | Fever, yellow sputum | Patchy interstitial infiltration | Not done | Open lung biopsy, non-caseating epithelioid-cell granuloma, GMS+ | Not described | [30] |

| 2014 | F/54 | KT | 2 years | Prednisolone, tacrolimus, MMF | Dry cough, fever | Ground glass opacities | Positive | Transbronchial biopsy granulomatous with exudates, GMS + | Yes | [22] |

| 2019 | M/53 | KT | 13 years, no rejection | Prednisolone, cyclosporine, MMF | Fatigue, dyspnea | Diffuse patchy ground glass and reticular opacities | Negative | Transbronchial biopsy, Granulomatous infiltration and giant cells, GMS + | Yes | [27] |

| Present case | M/60 | KT | 24 years, rejection | Tacrolimus, sirolimus, deflazacort | Sore throat | Multiple nodules | Positive | Open lung biopsy, Granuloma with necrosis, GMS + | No |

SOT, solid organ transplant; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; bronchoalveolar lavage; F, female; KT, kidney transplantation; GMS, Gomori methenamine silver stain; M, male; MMF, mycophenolic acid.

Some researchers have postulated that the granulomatous response results from a more robust immune status [26]. The increased number of CD4+ T cells following reduced immunosuppression may have facilitated a granulomatous response [22]. Asymptomatic nodular GPCP has been reported in an immunocompetent person [27]; therefore, a T-cell immune response may be necessary in the morphogenesis of GPCP. However, it is also hypothesized that the secretion of tumor necrosis factor-alpha by histiocytic cells could affect the granulomatous reaction of chronic P. jirovecii infection [25]. In the formation of granuloma, persistent antigens can induce macrophage activation, producing granulomas, while CD4+ T cells protect against infectious granulomas [28]. Because the enhancement of macrophage microbial capacity cannot compensate for CD4+ T cell deficiency, GPCP could develop in immunocompromised individuals. The pathogenesis of GPCP with respect to cellular immunity remains unclear.

Cases of Pneumocystis-induced hypercalcemia have been reported in renal transplant recipients [29]. According to a study of PCP cases among kidney transplant recipients, hypercalcemia was observed in 37% of PCP patients with high 1,25-(OH)2 vitamin D and low parathyroid hormone (PTH), suggesting a granuloma-mediated mechanism [30]. This resolved after successful treatment of PCP pneumonia [31]. Hypercalcemia has also been reported in patients with PCP infection who have undergone liver transplant or have AIDS [32,33]. PTH-independent hypercalcemia can occur after ectopic 1,25-(OH)2 vitamin D production caused by activated macrophages in a granuloma or macrophage dysfunction [34]. Although not all PCP infections present with granulomas, the pathogenesis might be shared through macrophage activation against P. jirovecii. In our patient, the calcium level was normal, which might have been affected by osteoporosis medications, including calcitriol.

In conclusion, the diagnosis of GPCP can be challenging due to atypical manifestations on chest imaging and the insensitivity of microbiologic diagnostic modalities. However, in SOT recipients with manifestations of chronic or relapsing atypical pneumonia with or without hypercalcemia, more vigilant efforts for histological diagnosis should be considered to avoid missing GPCP.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank Sang-Oh Lee for his contribution of preparing and mediating the Clinical Grand Round of the Korean Society of Infectious Disease (KSID) conference in 2022.

Footnotes

Funding: This study was supported by the Soonchunhyang University Research Fund.

Conflict of interest: No conflict of Interest.

- Conceptualization: KTH.

- Data curation: BYJ, NH, KTH.

- Formal analysis: BYJ, KK, NB.

- Methodology: BYJ, KK, JJ, LEJ, NH.

- Writing - original draft: BYJ.

- Writing - review & editing: LEJ, NH, KTH.

References

- 1.Asai N, Motojima S, Ohkuni Y, Matsunuma R, Nakashita T, Kaneko N, Mikamo H. Pathophysiological mechanism of non-HIV Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia. Respir Investig. 2022;60:522–530. doi: 10.1016/j.resinv.2022.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Apostolopoulou A, Fishman JA. The pathogenesis and diagnosis of Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia. J Fungi (Basel) 2022;8:1167. doi: 10.3390/jof8111167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fishman JA, Gans H AST Infectious Diseases Community of Practice. Pneumocystis jiroveci in solid organ transplantation: guidelines from the American Society of Transplantation Infectious Diseases Community of practice. Clin Transplant. 2019;33:e13587. doi: 10.1111/ctr.13587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim B, Kim J, Paik SS, Pai H. Atypical presentation of Pneumocystis jirovecii infection in HIV infected patients: three different manifestations. J Korean Med Sci. 2018;33:e115. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2018.33.e115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Attias P, Melica G, Boutboul D, De Castro N, Audard V, Stehlé T, Gaube G, Fourati S, Botterel F, Fihman V, Audureau E, Grimbert P, Matignon M. Epidemiology, risk factors, and outcomes of opportunistic infections after kidney allograft transplantation in the era of modern immunosuppression: a monocentric cohort study. J Clin Med. 2019;8:594. doi: 10.3390/jcm8050594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim JE, Han A, Lee H, Ha J, Kim YS, Han SS. Impact of Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia on kidney transplant outcome. BMC Nephrol. 2019;20:212. doi: 10.1186/s12882-019-1407-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Iriart X, Challan Belval T, Fillaux J, Esposito L, Lavergne RA, Cardeau-Desangles I, Roques O, Del Bello A, Cointault O, Lavayssière L, Chauvin P, Menard S, Magnaval JF, Cassaing S, Rostaing L, Kamar N, Berry A. Risk factors of Pneumocystis pneumonia in solid organ recipients in the era of the common use of posttransplantation prophylaxis. Am J Transplant. 2015;15:190–199. doi: 10.1111/ajt.12947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ponce CA, Gallo M, Bustamante R, Vargas SL. Pneumocystis colonization is highly prevalent in the autopsied lungs of the general population. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50:347–353. doi: 10.1086/649868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee YT, Chuang ML. Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia in AIDS and non-AIDS immunocompromised patients - an update. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2018;12:824–834. doi: 10.3855/jidc.10357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roux A, Canet E, Valade S, Gangneux-Robert F, Hamane S, Lafabrie A, Maubon D, Debourgogne A, Le Gal S, Dalle F, Leterrier M, Toubas D, Pomares C, Bellanger AP, Bonhomme J, Berry A, Durand-Joly I, Magne D, Pons D, Hennequin C, Maury E, Roux P, Azoulay É. Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia in patients with or without AIDS, France. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014;20:1490–1497. doi: 10.3201/eid2009.131668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim T, Sung H, Chong YP, Kim SH, Choo EJ, Choi SH, Kim TH, Woo JH, Kim YS, Lee SO. Low lymphocyte proportion in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid as a risk factor associated with the change from trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole used as first-line treatment for Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia. Infect Chemother. 2018;50:110–119. doi: 10.3947/ic.2018.50.2.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Freiwald T, Büttner S, Cheru NT, Avaniadi D, Martin SS, Stephan C, Pliquett RU, Asbe-Vollkopf A, Schüttfort G, Jacobi V, Herrmann E, Geiger H, Hauser IA. CD4+ T cell lymphopenia predicts mortality from Pneumocystis pneumonia in kidney transplant patients. Clin Transplant. 2020;34:e13877. doi: 10.1111/ctr.13877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Travis WD, Pittaluga S, Lipschik GY, Ognibene FP, Suffredini AF, Masur H, Feuerstein I, Kovacs J, Pass HI, Condron KS, Shelhamer JH. Atypical pathologic manifestations of Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia in the acquired immune deficiency syndrome. Review of 123 lung biopsies from 76 patients with emphasis on cysts, vascular invasion, vasculitis, and granulomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 1990;14:615–625. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199007000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hartel PH, Shilo K, Klassen-Fischer M, Neafie RC, Ozbudak IH, Galvin JR, Franks TJ. Granulomatous reaction to pneumocystis jirovecii: clinicopathologic review of 20 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010;34:730–734. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181d9f16a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dako F, Kako B, Nirag J, Simpson S. High-resolution CT, histopathologic, and clinical features of granulomatous pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia. Radiol Case Rep. 2019;14:746–749. doi: 10.1016/j.radcr.2019.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Diaz-Abad M, Robinett KS, Lasso-Pirot A, Legesse TB, Khambaty M. Granulomatous Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia in an HIV-positive patient on antiretroviral therapy: a diagnostic challenge. Open Respir Med J. 2021;15:19–22. doi: 10.2174/1874306402115010019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim HW, Heo JY, Lee YM, Kim SJ, Jeong HW. Unmasking granulomatous Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia with nodular opacity in an HIV-infected patient after initiation of antiretroviral therapy. Yonsei Med J. 2016;57:1042–1046. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2016.57.4.1042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Taeb AM, Sill JM, Derber CJ, Hooper MH. Nodular granulomatous Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia consequent to delayed immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome. Int J STD AIDS. 2018;29:1451–1453. doi: 10.1177/0956462418787603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim EJ, Yoo SJ, Kang GH, Hong MY, Hong JS, Ryu DS, Eom DW, Jung BH, Song EH. A case of multiple pulmonary nodular Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia in an acquired immune deficiency syndrome patient. Infect Chemother. 2012;44:40–43. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Patel KB, Gleason JB, Diacovo MJ, Martinez-Galvez N. Pneumocystis pneumonia presenting as an enlarging solitary pulmonary nodule. Case Rep Infect Dis. 2016;2016:1873237. doi: 10.1155/2016/1873237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shin SR, Kim TS, Han J. CT findings of granulomatous Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia in a patient with multiple myeloma. J Korean Soc Radiol. 2022;83:218–223. doi: 10.3348/jksr.2021.0043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Otahbachi M, Nugent K, Buscemi D. Granulomatous Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia in a patient with chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a literature review and hypothesis on pathogenesis. Am J Med Sci. 2007;333:131–135. doi: 10.1097/00000441-200702000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Assaad M, Swalih M, Karki A. Necrotizing granulomatous Pneumocystis infection presenting as a solitary pulmonary nodule: a case report and review of the literature. Case Rep Pulmonol. 2022;2022:7481636. doi: 10.1155/2022/7481636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim HS, Shin KE, Lee JH. Single nodular opacity of granulomatous pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia in an asymptomatic lymphoma patient. Korean J Radiol. 2015;16:440–443. doi: 10.3348/kjr.2015.16.2.440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kumar N, Bazari F, Rhodes A, Chua F, Tinwell B. Chronic Pneumocystis jiroveci presenting as asymptomatic granulomatous pulmonary nodules in lymphoma. J Infect. 2011;62:484–486. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2011.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ramalho J, Bacelar Marques ID, Aguirre AR, Pierrotti LC, de Paula FJ, Nahas WC, David-Neto E. Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia with an atypical granulomatous response after kidney transplantation. Transpl Infect Dis. 2014;16:315–319. doi: 10.1111/tid.12198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lam J, Kelly MM, Leigh R, Parkins MD. Granulomatous PJP presenting as a solitary lung nodule in an immune competent female. Respir Med Case Rep. 2013;11:4–6. doi: 10.1016/j.rmcr.2013.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pagán AJ, Ramakrishnan L. The formation and function of granulomas. Annu Rev Immunol. 2018;36:639–665. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-032712-100022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hajji K, Dalle F, Harzallah A, Tanter Y, Rifle G, Mousson C. Vitamin D metabolite-mediated hypercalcemia with suppressed parathormone concentration in Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia after kidney transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2009;41:3320–3322. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2009.08.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hamroun A, Lenain R, Bui Nguyen L, Chamley P, Loridant S, Neugebauer Y, Lionet A, Frimat M, Hazzan M. Hypercalcemia is common during Pneumocystis pneumonia in kidney transplant recipients. Sci Rep. 2019;9:12508. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-49036-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Taylor LN, Aesif SW, Matson KM. A case of Pneumocystis pneumonia, with a granulomatous response and vitamin D-mediated hypercalcemia, presenting 13 years after renal transplantation. Transpl Infect Dis. 2019;21:e13081. doi: 10.1111/tid.13081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yau AA, Farouk SS. Severe hypercalcemia preceding a diagnosis of Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia in a liver transplant recipient. BMC Infect Dis. 2019;19:739. doi: 10.1186/s12879-019-4370-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ahmed B, Jaspan JB. Case report: hypercalcemia in a patient with AIDS and Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia. Am J Med Sci. 1993;306:313–316. doi: 10.1097/00000441-199311000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cruickshank B. Pulmonary granulomatous pneumocystosis following renal transplantation. Report of a case. Am J Clin Pathol. 1975;63:384–390. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/63.3.384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]