This randomized clinical trial assesses whether an online group coaching program reduces burnout and increases well-being for women physician trainees.

Key Points

Question

Can a 4-month, online, group coaching program reduce burnout, moral injury, and impostor syndrome and increase self-compassion and flourishing among a sample of women physician trainees across multiple sites?

Findings

In this randomized clinical trial of 1017 women trainee physicians, participants randomly assigned to a 4-month group-coaching program had a statistically significant reduction in all scales of burnout, moral injury, and impostor syndrome, as well as improved self-compassion and flourishing, compared with the control group.

Meaning

These findings suggest that an online, multimodal, group coaching program is an effective intervention to decrease distress and improve well-being for women physician trainees.

Abstract

Importance

Physician burnout disproportionately affects women physicians and begins in training. Professional coaching may improve well-being, but generalizable evidence is lacking.

Objective

To assess the generalizability of a coaching program (Better Together Physician Coaching) in a national sample of women physician trainees.

Design, Setting, and Participants

A randomized clinical trial involving trainees in 26 graduate medical education institutions in 19 states was conducted between September 1, 2022, and December 31, 2022. Eligible participants included physician trainees at included sites who self-identified as a woman (ie, self-reported their gender identity as woman, including those who reported woman if multiple genders were reported).

Intervention

A 4-month, web-based, group coaching program.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary outcomes were change in burnout (measured using subscales for emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and personal achievement from the Maslach Burnout Inventory). Secondary outcomes included changes in impostor syndrome, moral injury, self-compassion, and flourishing, which were assessed using standardized measures. A linear mixed model analysis was performed on an intent-to-treat basis. A sensitivity analysis was performed to account for the missing outcomes.

Results

Among the 1017 women trainees in the study (mean [SD] age, 30.8 [4.0] years; 540 White participants [53.1%]; 186 surgical trainees [18.6%]), 502 were randomized to the intervention group and 515 were randomized to the control group. Emotional exhaustion decreased by an estimated mean (SE) −3.81 (0.73) points in the intervention group compared with a mean (SE) increase of 0.32 (0.57) points in the control group (absolute difference [SE], −4.13 [0.92] points; 95% CI, −5.94 to −2.32 points; P < .001). Depersonalization decreased by a mean (SE) of −1.66 (0.42) points in the intervention group compared with a mean (SE) increase of 0.20 (0.32) points in the control group (absolute difference [SE], −1.87 [0.53] points; 95%CI, −2.91 to −0.82 points; P < .001). Impostor syndrome decreased by a mean (SE) of −1.43 (0.14) points in the intervention group compared with −0.15 (0.11) points in the control group (absolute difference [SE], −1.28 (0.18) points; 95% CI −1.63 to −0.93 points; P < .001). Moral injury decreased by a mean (SE) of −5.60 (0.92) points in the intervention group compared with −0.92 (0.71) points in the control group (absolute difference [SE], −4.68 [1.16] points; 95% CI, −6.95 to −2.41 points; P < .001). Self-compassion increased by a mean (SE) of 5.27 (0.47) points in the intervention group and by 1.36 (0.36) points in the control group (absolute difference [SE], 3.91 [0.60] points; 95% CI, 2.73 to 5.08 points; P < .001). Flourishing improved by a mean (SE) of 0.48 (0.09) points in the intervention group vs 0.09 (0.07) points in the control group (absolute difference [SE], 0.38 [0.11] points; 95% CI, 0.17 to 0.60 points; P < .001). The sensitivity analysis found similar findings.

Conclusions and Relevance

The findings of this randomized clinical trial suggest that web-based professional group-coaching can improve outcomes of well-being and mitigate symptoms of burnout for women physician trainees.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT05222685

Introduction

Physician burnout is highly prevalent in the US; is disproportionately experienced by physician trainees and women; and is associated with substance abuse, job turnover, higher rates of medical errors, and patient mortality.1,2,3,4,5 In 2022, the US Surgeon General declared physician burnout a crisis deserving of a multipronged approach to bring about “bold, fundamental change,”6 yet little is known about scalable, effective interventions to mitigate burnout risk.1,7,8,9

Professional coaching is a promising intervention to reduce burnout.10,11,12,13 The 2022 Surgeon General’s Advisory emphasized building a culture of well-being in training institutions and included coaching as a recommended tool.6,14 Coaching, unlike therapy, does not diagnose or treat, and instead uses inquiry and metacognition (ie, thinking about one’s thinking) to guide self-progress.15,16 Evidence supporting physician coaching is growing, but predominantly describes individual coaching led by nonphysician or noncertified faculty coaches in small studies.11,12,17,18,19,20 Literature on outcomes of coaching for physician trainees is sparse, limited to small samples and single specialties, and primarily includes programs of short duration.10,11,17,21,22

An online group coaching program, Better Together Physician Coaching (BT), was piloted in response to high physician trainee burnout.10,13 Because women trainees are disproportionately affected by burnout,3,4,5 BT was initially evaluated among women resident physicians at the University of Colorado in a pilot, single site, randomized clinical trial (RCT), which indicated that online group coaching improved burnout.10 Building on previous work, the objective of this multisite RCT was to evaluate the generalizability of the 4-month online group coaching program to reduce distress and improve well-being in a national sample of women physician trainees.

Methods

Trial Oversight

This RCT follows the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) reporting guideline23 and was approved by the University of Colorado institutional review board (see the Trial Protocol in Supplement 1). The study was conducted from September 1, 2022, to December 31, 2022, at 26 graduate medical education (GME) institutions across 19 states (eTable 1 in Supplement 2). Sites of different geographic locations, sizes, and focuses (ie, community vs academic) were recruited and included academic, county, Veterans Health Administration, and community-based hospitals and clinics. Recruitment emails were initially sent to institutional leadership, and video conference calls were held to confirm partnership in this study. Participant enrollment was voluntary, and all participants provided written informed consent. Data were collected and managed with The University of Colorado Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap). Participating sites were not involved in research and could not access identifiable data.

Participants and Trial Groups

All GME physician trainees who self-identified as a woman (ie, self-reported their gender identity as a woman, including those who reported woman if multiple genders were reported) at participating sites were eligible. Trainees were recruited through a series of 3 emails to a GME electronic mailing list. After enrollment, participants were randomly assigned to the intervention (access to online group coaching) or control group (no access). Randomization was stratified on the basis of the site. Intervention participants were not given protected time for the intervention and carried the same clinical schedules as control participants. All participants were asked to complete baseline (prior to randomization) and 4-month (end of intervention) surveys containing self-reported demographic questions and validated instruments measuring dimensions of distress and well-being. Participants had the ability to select multiple options for race and ethnicity and gender identity questions. Response options for gender identity included man, woman, nonbinary, not sure, not listed, and prefer not to say. Race and ethnicity categories included Asian, Black, Latinx, multiracial, Native American, Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander, White, and other (defined as unknown or any other race or ethnicity not otherwise specified); race and ethnicity were included to ensure generalizability of the intervention. The control group was offered the intervention after the study. To account for benefits accruing from expectations rather than the intervention, both groups were emailed alternative online wellness resources.24,25,26,27,28

Intervention: Better Together

BT is a 4-month, online, group coaching program developed by 2 professional physician coaches (T.F. and A.M.) and was delivered by a cohort of physician coaches (including author A.S.) who were all certified by The Life Coach School. Coach selection is described in the eMethods in Supplement 2. The program incorporates facets of user engagement from Short et al29 (eg, self-monitoring, reminders, and aesthetics), and the Cole-Lewis framework30 for behavior change (ie, modular, course-like, weekly introduction of content). More information on the foundational framework, program modalities, and curriculum can be found in the eMethods in Supplement 2. Participants had access to the following services housed on a members-only, password-protected website: (1) 3 to 4 live group coaching calls per week via video teleconference (Zoom Video Communications), (2) unlimited anonymous written coaching, and (3) weekly self-study modules on pertinent topics. Video teleconference sessions were recorded for asynchronous listening via private podcast. Topics were selected on the basis of an informal trainee needs assessment done prior to the pilot and were iteratively refined on the basis of rapid content analyses of coaching requests. The program required approximately 5 hours per week of total coach time.

Distress Outcomes

Burnout

The 22-item Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI) is considered the benchmark standard to measure burnout and was used under license.31 The MBI contains 3 subscales: emotional exhaustion (EE; score range, 0-54), where a higher score indicates worse EE; depersonalization (DP; score range, 0-30), where a higher score indicates worse DP; and personal accomplishment (PA; score range, 0-48), where a higher score indicates better feelings of PA.32 We used established threshold definitions of high EE (subscale score ≥27), high DP (subscale score ≥10), and low PA (subscale score ≤33), and considered those with high EE or DP to have at least 1 manifestation of burnout and meet the definition for positive burnout.19,20,33

Impostor Syndrome and Moral Injury

The Young Impostor Syndrome scale34 is an 8-item instrument with yes-or-no scoring and a range of 0 to 8. A score of 5 or greater indicates the presence of impostor syndrome. The Moral Injury Symptom Scale–Healthcare Professionals35 is a 10-item instrument with scores ranging from 10 to 100. Higher scores indicate greater moral injury.

Well-Being Outcomes

Self-Compassion and Flourishing

The Neff Self-Compassion Scale–Short Form36 is a 12-item instrument (total scale range, 12-60). Scores of 12 to 30 are considered low, 30 to 42 are considered moderate, and 42 to 60 are considered high. The Secure Flourish Index37 is a 12-item instrument assessing 5 domains of flourishing. Scores range from 0 to12 and higher scores indicate greater flourishing.

Statistical Analysis

We assumed no change in preintervention scores and postintervention scores for the control group and used estimates for the SD of the change in MBI scores from our pilot data.10 The power calculation for a minimum power of 80% (2-sided α = .05) to detect a standardized effect size (SD = 1) of 0.2, corresponded to a difference in mean (SD) values between the groups of 1.7 (8.6) in EE, 1.7 (8.6) in DP, and 1.0 (4.9) in PA, resulting in an enrollment target of 1000.

Descriptive statistics were computed for characteristics of the whole cohort and by intervention, with comparisons made using Wilcoxon rank sum tests for continuous covariates and Fisher exact or χ2 tests for categorical covariates. Characteristics of final survey responders and nonresponders were compared. Descriptive statistics were adjusted for multiple comparisons using the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure.38 P values from regression models were reported unadjusted.

An intent-to-treat analysis was performed on all participants regardless of postsurvey completion using linear and logistic mixed-effects models including the main effects of the time period (baseline vs postintervention), treatment (intervention vs control), the interaction between time period and treatment, and a random intercept for participants estimated using restricted maximum likelihood. Mean change from baseline within each group and the difference in mean change between groups and their 95% CIs were reported. Mixed-effects logistic regression models were used for EE, PA, DP, Young Impostor Syndrome Scale, Moral Injury Symptom Scale-Healthcare Professionals, Self-Compassion Scale-Short Form, Secure Flourish Index and for the binary outcomes of burnout and impostor syndrome.

Linear and logistic regression models were used to estimate mean change from baseline and odds ratios (ORs) adjusted for baseline value and their 95% CIs. The binary outcomes of burnout and impostor syndrome at follow-up were separately modeled using logistic regressions with treatment group and baseline values as variables. Effect sizes (risk difference, number needed to treat [NNT], and relative risk) for burnout and impostor syndrome were estimated from models using the same counterfactual framework for marginal effects. The 95% CIs were estimated with simulation.

In sensitivity analyses, to assess the potential influence of missing follow-up survey data on study outcomes, multiple imputation was used for missing score values via iterative chained random forest39 with predictive mean matching. The imputation model included baseline characteristics, treatment assignment, and baseline scores.

All P values are from 2-sided hypothesis tests and statistical significance was assessed at the α = .05 level. All analyses were performed using R statistical software version 4.2.3 (R Project for Statistical Computing).

Results

Participants

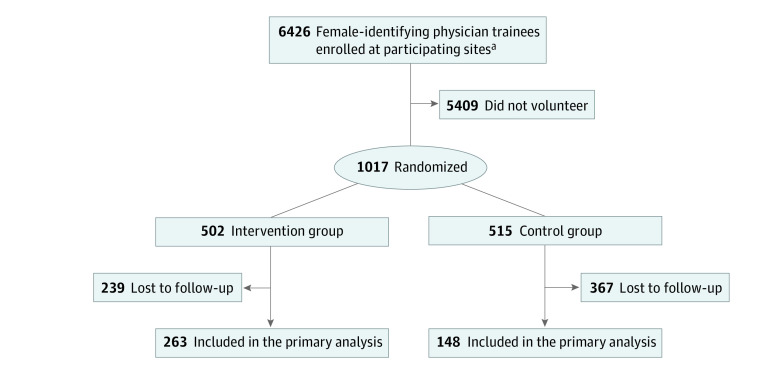

Of the 1017 participants (mean [SD] age, 30.8 [4.0] years; age range, 24.0-54.0 years; 540 White participants [53.1%]) enrolled, 502 were randomized to the intervention and 515 were randomized to the control group (Figure 1). All 26 sites had at least 1 participant in the intervention group (eTable 1 in Supplement 2). There were no significant baseline differences in demographics or outcome scores between groups (Table 1). Among all participants, 959 (94.3%) self-reported their gender identity as woman and 843 (88.0%) self-reported their sexual orientation as heterosexual. A total of 207 physician trainees (20.7%) were in postgraduate year (PGY) 1, 198 (19.8%) in PGY 2, and 595 (59.5%) in PGY 3 or beyond, with 186 of 999 physician trainees (18.6%) in a surgical subspecialty.

Figure 1. Participant Enrollment Flowchart.

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics of All Enrolled Participants (Intention-to-Treat).

| Variable or outcome | Participants, No. (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall (N = 1017) | Control (n = 515) | Intervention (n = 502) | |

| Age, y | |||

| Mean (SD) | 30.9 (4.0) | 31.0 (4.1) | 30.8 (3.9) |

| Median (range) | 30.0 (24.0-56.0) | 30.0 (24.0-56.0) | 30.0 (24.0-54.0) |

| Postgraduate year | |||

| 1 | 207(20.7) | 98 (19.3) | 109 (22.2) |

| 2 | 198 (19.8) | 97(19.1) | 101 (20.5) |

| ≥3 | 595 (59.5) | 313 (61.6) | 282 (57.3) |

| Training specialty | |||

| Nonsurgical | 813 (81.4) | 417 (82.1) | 396 (80.7) |

| Surgical, No./total No. (%) | 186/999 (18.6) | 91/508 (17.9) | 95/491 (19.3) |

| Gender identity | |||

| Woman | 959 (94.3) | 485 (94.2) | 474 (94.4) |

| Man, nonbinary, other, or prefer not to say | 58 (0.2) | 29 (0.1) | 28 (0.1) |

| Transgender | |||

| No | 938 (97.4) | 476 (97.5) | 462 (97.3) |

| Yes | 24 (2.5) | 11 (2.3) | 13 (2.7) |

| Prefer not to say | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.2) | 0 |

| Racial and ethnic identity | |||

| Asian | 229 (22.5) | 110 (21.4) | 119 (23.7) |

| Black | 52 (5.1) | 22 (4.3) | 30 (6.0) |

| Latinx | 83 (8.2) | 41 (8.0) | 42 (8.4) |

| Multiracial | 35 (3.4) | 20 (3.9) | 15 (3.0) |

| Native American | 2 (0.2) | 0 | 2 (0.4) |

| Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander | 2 (0.2) | 0 | 2 (0.4) |

| White | 540 (53.1) | 285 (55.3) | 255 (50.8) |

| Othera | 157 (15.4) | 78 (15.1) | 79 (15.7) |

| Sexual orientation, No./total No. (%) | |||

| Heterosexual | 843/958 (88.0) | 433/487 (88.9) | 410/471 (87.0) |

| Homosexual | 21/958 (2.2) | 11/487 (2.) | 10/471 (2.1) |

| Bisexual | 68/958 (7.1) | 33/487 (6.8) | 35/471 (7.4) |

| Other | 6/958 (0.6) | 4/487 (0.8) | 2/471 (0.4) |

| Prefer not to say | 20/958 (2.1) | 6/487 (1.2) | 14/471 (3.0) |

| Distress outcome | |||

| Burnout | |||

| MBI personal achievement subscale | |||

| Completed subscale, No. overall/No. observed (% not missing) | 812 (79.8) | 405(78.6) | 407 (81.1) |

| Score, mean (SD) | 33.3 (7.3) | 33.5 (7.2) | 33.1 (7.3) |

| Score, Median (IQR) | 34.0 (29.0-38.0) | 34.0 (29.0-38.0) | 34.0 (28.0-38.0) |

| Score, Range | 8.0-48.0 | 11.0-48.0 | 8.0-47.0 |

| MBI emotional exhaustion subscale | |||

| Completed subscale, No. overall/No. observed (% not missing) | 788 (77.5) | 394 (76.5) | 394 (78.5) |

| Score, mean (SD) | 30.6 (10.8) | 30.5 (11.0) | 30.6 (10.5) |

| Score, median (IQR) | 31.0 (23.0-38.0) | 32.0 (23.0-39.0) | 31.0 (23.0-38.0) |

| Score, range | 8.0-48.0 | 11.0-48.0 | 8.0-47.0 |

| MBI depersonalization subscale | |||

| Completed subscale, No. overall/No. observed (% not missing) | 810 (79.6) | 405 (78.6) | 405 (80.7) |

| Score, mean (SD) | 11.8 (6.4) | 11.8 (6.6) | 11.9 (6.3) |

| Score, median (IQR) | 12.0 (7.0-17.0) | 12.0 (6.0-17.0) | 11.0 (7.0-16.0) |

| Score, range | 0.0-29.0 | 0.0-29.0 | 0.0-28.0 |

| Met definition for positive burnout, No. overall/No. observed (% not missing) | |||

| No | 211/781 (27.0) | 108/391 (27.6) | 103/390 (26.4) |

| Yes | 570/781 (73.0) | 283/391 (72.4) | 287/390 (73.6) |

| Impostor syndrome | |||

| Completed YIS, No. overall/No. observed (% not missing) | 784/1017 (77.1) | 388/515 (75.3) | 396/502 (78.9) |

| YIS score, mean (SD) | 5.8 (2.0) | 5.8 (1.9) | 5.9 (2.0) |

| YIS score, median (IQR) | 6.0 (5.0-7.2) | 6.0 (5.0-7.0) | 6.0 (5.0-8.0) |

| YIS score, range | 0.0-8.0 | 0.0-8.0 | 0.0-8.0 |

| YIS ≥5 | |||

| No | 186/784 (23.7) | 91/388 (23.5) | 95/396 (24.0) |

| Yes | 598/784 (76.3) | 297/388 (76.5) | 301/396 (76.0) |

| Moral injury | |||

| Completed MISS-HP | 787(77.4) | 393 (76.3) | 394 (78.5) |

| MISS-HP score, mean (SD) | 45.9 (13.7) | 46.6 (13.8) | 45.2 (13.6) |

| MISS-HP score, median (IQR) | 47.0 (36.0-55.0) | 47.0 (37.0-56.0) | 45.5 (35.0-54.0) |

| MISS-HP score, range | 12.0-95.0 | 12.0-95.0 | 15.0-89.0 |

| Well-being outcome | |||

| Self-compassion | |||

| Completed SCS-SF, No. overall/No. observed (% not missing) | 788 (77.5) | 391 (75.9) | 397 (79.1) |

| SCS-SF score, mean (SD) | 31.6 (7.3) | 31.7 (7.4) | 31.4 (7.2) |

| SCS-SF score, median (IQR) | 31.0 (27.0-36.0) | 31.0 (27.0-36.0) | 31.0 (26.0-37.0) |

| SCS-SF score, range | 12.0-60.0 | 12.0-60.0 | 14.0-55.0 |

| Flourishing | |||

| Completed SFI, No. overall/No. observed (% not missing) | 737 (72.5) | 366(71.1) | 371 (73.9) |

| SFI score, mean (SD) | 6.2 (1.3) | 6.2 (1.3) | 6.2 (1.3) |

| SFI score, median (IQR) | 6.2 (5.2-7.2) | 6.2 (5.2-7.1) | 6.2 (5.2-7.2) |

| SFI score, range | 2.6-9.5 | 3.0-9.5 | 2.6-9.5 |

Abbreviations: MBI, Maslach Burnout Inventory; MISS-HP, Moral Injury Symptom Scale-Healthcare Professionals; SCS-SF, Self-Compassion Scale-Short Form; SFI, Secure Flourish Index; YIS, Young Imposter Syndrome scale.

Other race and ethnicity was defined as unknown or any other race or ethnicity not otherwise specified.

At baseline, the mean (SD) score was 30.6 (10.8) for EE, 11.8 (6.4) for DP, and 33.3 (7.3) for PA. A total of 570 participants scored positively for burnout, which represents 73.0% of the 781 participants who completed the full MBI. Of 784 participants who completed the YIS, 598 (76.3%) scored positively for impostor syndrome. The mean (SD) score was 45.9 (13.7) for moral injury, 31.6 (7.3) for self-compassion, and 6.2 (1.3) for flourishing. There were 411 participants (40.4%) who responded to the follow-up survey, with more participants in the control group (263 participants [51.0%; 95% CI, 47%-55%]) than the intervention group (148 participants [30.0%; 95% CI, 26%-34%]) (P < .05). Postsurvey respondents and nonrespondents differed by race, gender identity, and PGY (eTable 2 in Supplement 2).

Distress Outcomes

Burnout

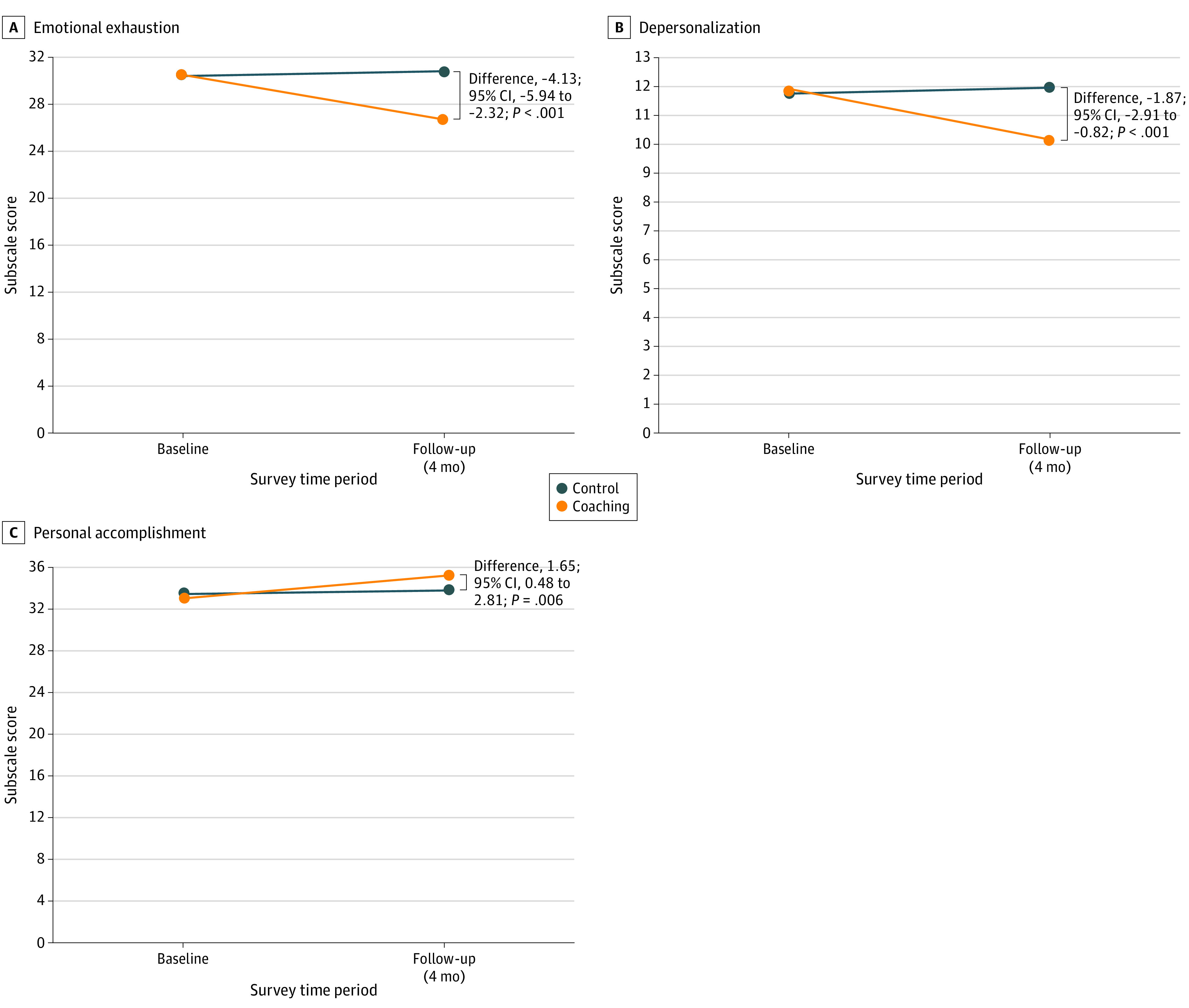

Intervention participants experienced significant improvement compared with the control group on all MBI subscales. For EE, the estimated change in score for the intervention group (mean [SE] −3.81 [0.73] points; 95% CI, −5.24 to −2.38 points) vs the control group (mean [SE] 0.32 [0.57] points; 95% CI, −0.79 to 1.43 points) resulted in an absolute difference (SE) in EE of −4.13 (0.92) points (95% CI, −5.94 to −2.32 points; P < .001).For DP, the estimated change in score for the intervention group (mean [SE] −1.66 [0.42] points; 95% CI, −2.49 to 0.83 points) vs the control group (mean [SE] 0.20 [0.32] points; 95% CI, −0.43 to 0.84 points) resulted in an absolute difference (SE) of −1.87 (0.53) points (95% CI, −2.91 to −0.82 points; P < .001). For PA, the estimated change in score for the intervention group (mean [SE] 2.08 [0.47] points; 95% CI, 1.15-3.00 points) vs control group (mean [SE] 0.43 [0.36] points; 95% CI, −0.28 to 1.13 points) resulted in an absolute difference (SE) of 1.65 (0.59) points (95% CI, 0.48 to 2.81 points; P = .006) (Table 2 and Figure 2).

Table 2. Mean Change in Response From Baseline Visit, Established From Linear Mixed-Effects Models.

| Outcome | Intervention group | Control group | Absolute difference (SE) in score change for intervention vs control, points [95% CI] | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participants, No. | Estimated score change, points (SE) [95% CI] | Participants, No. | Estimated change, points (SE) [95% CI] | |||

| Distress | ||||||

| Burnout | ||||||

| MBI emotional exhaustion subscale score | ||||||

| Baseline | 394 | −3.81 (0.73) [95% CI, −5.24 to −2.38] | 394 | 0.32 (0.57) [−0.79 to 1.43] | −4.13 (0.92) [−5.94 to −2.32] | <.001 |

| After intervention | 142 | 256 | ||||

| MBI depersonalization subscale score | ||||||

| Baseline | 407 | −1.66 (0.42) [−2.49 to 0.83 points] | 405 | 0.20 (0.32) [−0.43 to 0.84] | −1.87 (0.53) [−2.91 to −0.82] | <.001 |

| After intervention | 144 | 260 | ||||

| MBI personal achievement subscale score | ||||||

| Baseline | 405 | 2.08 (0.47) [1.15-3.00] | 405 | 0.43 (0.36) [−0.28 to 1.13] | 1.65 (0.59) [0.48 to 2.81] | .006 |

| After intervention | 143 | 260 | ||||

| Young Impostor Syndrome scale score | ||||||

| Baseline | 396 | −1.43 (0.14) [−1.70 to −1.15] | 388 | −0.15 (0.11) [−0.36 to 0.07] | −1.28 (0.18) [−1.63 to −0.93] | <.001 |

| After intervention | 140 | 252 | ||||

| Moral Injury Symptom Scale score | ||||||

| Baseline | 394 | −5.60 (0.92) [−7.40 to −3.81] | 393 | −0.92 (0.71) [−2.31 to 0.46] | −4.68 (−2.41) [−6.95 to 2.41] | <.001 |

| After intervention | 142 | 254 | ||||

| Well-being | ||||||

| Self-compassion Scale-Short Form score | ||||||

| Baseline | 397 | 5.27 (0.47) [4.34 to 6.20] | 391 | 1.36 (0.36) [0.65 to 20.80] | 3.91 (0.60) [2.73 to 5.08] | <.001 |

| After intervention | 142 | 255 | ||||

| Secure Flourish Index score | ||||||

| Baseline | 371 | 0.48 (0.09) [0.31 to 0.65] | 366 | 0.09 (0.07) [−0.04 to 0.23] | 0.38 (0.11) [0.17 to 0.60] | <.001 |

| After intervention | 131 | 240 | ||||

Abbreviation: MBI, Maslach Burnout Inventory.

Figure 2. Mean Change in Burnout Response From Baseline Visit, Estimated From Linear Mixed-Effects Models.

The figure shows the change in score for both the control group and intervention group from baseline to follow-up on the 3 subscales of the Maslach Burnout Inventory: emotional exhaustion (A), depersonalization (B), and personal accomplishment (C).

Intervention participants experienced an 18% (95% CI, 5%-31%) reduction in probability of burnout, with an OR of 0.47 (95% CI, 0.28-0.78; P = .008) compared with the control (ie, intervention participants had 53% lower odds of experiencing burnout at follow-up), with an NNT of 11 (95% CI, 7.1-22.4) to go from positive to negative burnout (eTable 3 in Supplement 2).

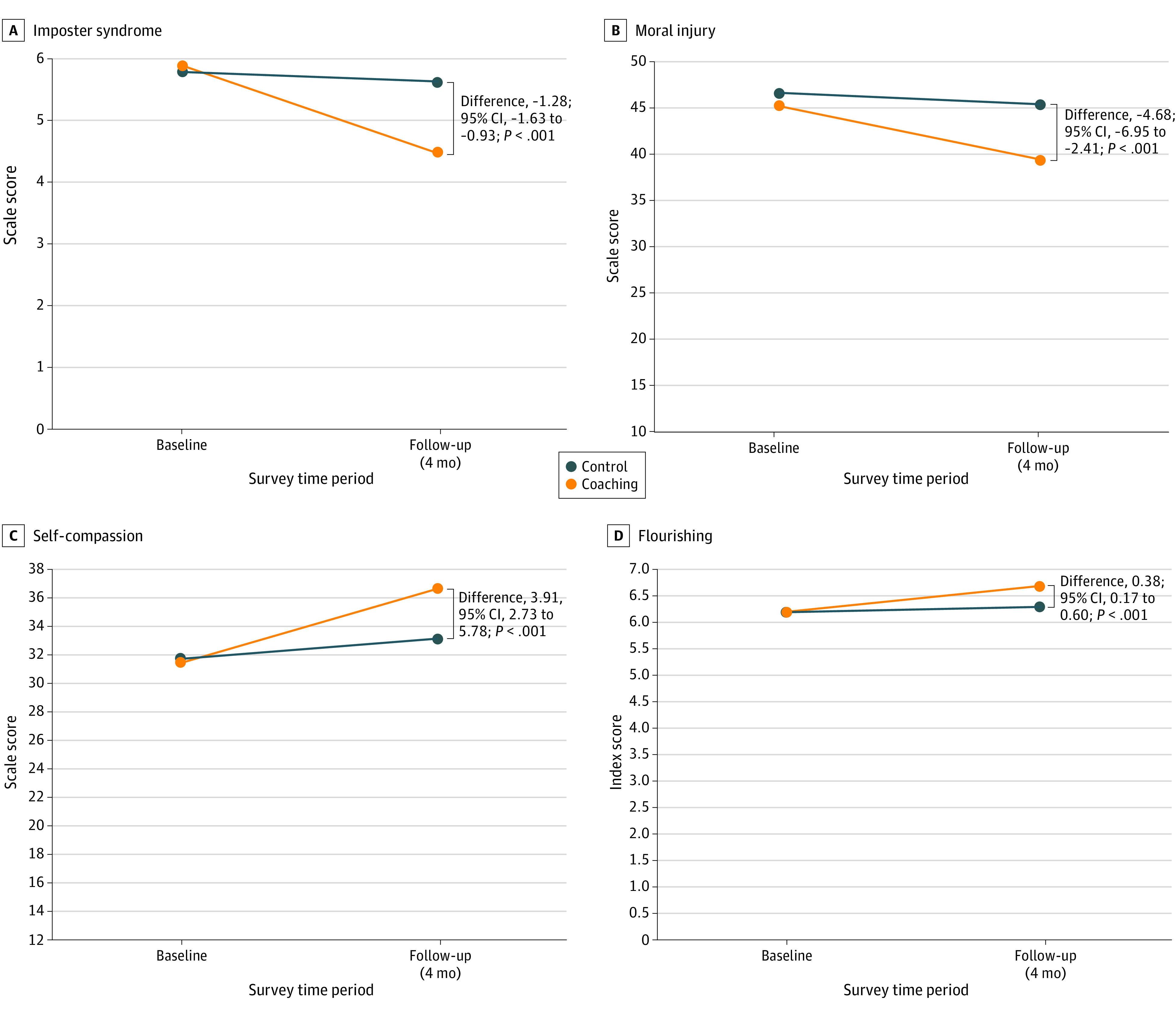

Impostor Syndrome

Intervention participants experienced a significant decrease in impostor syndrome with an absolute difference (SE) of −1.28 (0.18) points (95% CI, −1.63 to −0.93 points; P < .001); the mean (SE) change in score for the intervention group was −1.43 (0.14) points (95% CI, −1.70 to −1.15 points) and the mean (SE) change in score for the control group was −0.15 (0.11) points (95% CI, −0.36 to 0.07 points) (Figure 3). Intervention participants had a 34% (95% CI, 16% to 52%) reduced probability of impostor syndrome (OR, 0.36; 95% CI, 0.21 to 0.62; P < .001) with an NNT of 9 (95% CI, 6.8 to 17.8 to go from positive to negative impostor syndrome (eTable 3 in Supplement 2).

Figure 3. Mean Change in Secondary Outcome Response From Baseline Visit, Estimated From Linear Mixed Effects Models.

The figure shows the change in score for both the control group and intervention group from baseline to follow-up for Impostor syndrome (A), moral injury (B), self-compassion (C), and flourishing (D).

Moral Injury

Intervention participants experienced a significant decrease in moral injury with an absolute difference (SE) of −4.68 (1.16) points (95% CI, –6.95 to −2.41 points; P < .001). The mean (SE) change on the Moral Injury Symptom Scale for the intervention group was −5.60 (0.92) points (95% CI, −7.40 to −3.81 points) vs −0.92 (0.71) points (95% CI, −2.31 to 0.46 points) for the control group (Figure 3).

Well-Being Outcomes

Self-Compassion

There was a significant improvement in self-compassion with an absolute difference (SE) of 3.91 (0.60) points (95% CI, 2.73 to 5.08 points; P < .001). The mean (SE) change on the Self-Compassion Scale–Short Form was 5.27 (0.47) points (95% CI, 4.34 to 6.20 points) for the intervention group vs 1.36 (0.36) points (95% CI, 0.65 to 20.80 points) for the control group (Figure 3).

Flourishing

There was a significant improvement in flourishing with an absolute difference (SE) of 0.38 (0.11) points (95% CI, 0.17 to 0.60 points; P < .001). The mean (SE) change on the Secure Flourish Index was 0.48 (0.09) points (95% CI, 0.31 to 0.65 points) for the intervention group vs 0.09 (0.07) points (95% CI, −0.04 to 0.23 points) for the control group (Figure 3).

Sensitivity Analysis

Similar outcome results were obtained using multiple imputation and when baseline scores were carried forward for missing follow-up scores. See eTable 4 in Supplement 2 for more information on the sensitivity analysis.

Discussion

In this large, national RCT, women physician trainees who received online group coaching over 4 months had substantial reductions in multiple dimensions of professional distress (burnout, moral injury, and impostor syndrome) and improvements in well-being (self-compassion and flourishing). The improvement in burnout was significant and likely meaningful, with past studies40,41 showing that even a 1-point increase in EE has been associated with a 7% increase in suicidal ideation and a 5% increase in self-reported major medical errors. Additionally, intervention trainees reported less moral injury, lower odds of impostor syndrome, and increased flourishing and self-compassion.

We have previously demonstrated online group coaching reduced burnout among women trainees across specialties at a single institution.10 The digital platform and group nature of this study allowed a 10-fold expansion of participants and an addition of 25 sites with only 30 additional hours of direct coaching (1-2 more calls per week compared with the pilot study).10 The group and online delivery of the intervention supported greater scalability, accessibility, and lower cost compared with individual coaching. Furthermore, the magnitudes of improvement in scores described here were generally higher than other coaching and wellness interventions17,19,20,42,43,44 and higher than that of our single-site pilot RCT.10 Our findings show effectiveness in a broader population and match national data for trainees that self-report as underrepresented in medicine.45 We hypothesize that the greater impact may be due to iterative refinements, the maturity of the program, and the addition of nationwide participants who created community and normalized otherwise isolating challenges in medicine.13

In a recent advisory,46 the US Surgeon General strongly recommends integrating social connection into wellness programs focused on burnout. A major theme that arose from a qualitative analysis13 of participants’ experience of online group coaching was an increased sense of connection, even during a time of profound social isolation during the COVID-19 pandemic. Given the digital platform, online group coaching is easily accessed by rural and less resourced programs. Online group coaching is an example of an institutionally provided, individually harnessed tool to build a culture of connection necessary to heal physician burnout.

Limitations

This study has limitations. Voluntary participation may have created selection bias. This study enrolled only participants who identify as women, so outcomes among individuals who identify as men is unknown. There could have been selection bias of sites, a process that was dependent on leadership buy-in, which is vulnerable to bias. We did not use cluster randomization given our interest in individual rather than group-level changes in outcomes, and we also wanted to avoid loss of statistical power. This study is unique in that the intervention was administered digitally by a centralized entity and not separately at each site as in more traditional clinical trials. However, we may consider cluster randomization in future studies. Contamination was possible because each site had participants in control and intervention groups, although mitigation efforts were implemented (eg, password access to intervention materials).

We had substantial loss to follow-up. Control participants were significantly more likely to respond to the survey than intervention participants, perhaps due to email fatigue (the intervention group received 2emails weekly), or control participants may have been more motivated in anticipation of receiving the intervention. There were racial, gender identity, and PGY differences between follow-up survey responders and nonresponders. This finding may be related to previously established observations that those with higher time constraints (ie, participants in PGY 1) may feel marginalized, and those who are underrepresented in medicine due to their race and/or gender identity may feel less socially connected and less inclined to complete surveys.47,48 We attempted to assess the effect of missing follow-up survey data on study outcomes with the sensitivity analysis, a statistical technique to evaluate the effect of the missing data (eTable 4 in Supplement 2), which did not find significant outcome differences. Because participants did not use the same login for each coaching call, downloaded podcast, or curriculum module, we were unable to measure engagement or correlate it with outcomes. Additionally, the study team and participants could not be masked, and outcomes could have accrued in part from participant expectations despite providing both groups access to well-being resources as a plausible alternative. Furthermore, we did not evaluate the postintervention effect, which warrants future study.

Conclusions

Compared with GME training as usual, an online 4-month group-coaching program for women physician trainees delivered by certified physician coaches resulted in significant improvement in professional distress and well-being, with an NNT of 11 to mitigate burnout. Group coaching interventions may have a role in mitigating physician trainee burnout and improving well-being along with system-level interventions to improve the work and learning environment.

Trial Protocol

eTable 1. Site Participation

eMethods. BT Coach Onboarding and Facets of BT Program

eTable 2. Participant Characteristics at Baseline by Survey Completion

eTable 3. Effect Sizes for Burnout and Impostor Syndrome

eTable 4. Intention to Treat Sensitivity Analysis: Mean Change in Response From Baseline Visit, Estimated From Linear Regression Adjusted for Baseline Value

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Dzau VJ, Kirch DG, Nasca TJ. To care is human: collectively confronting the clinician-burnout crisis. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(4):312-314. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1715127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.West CP, Dyrbye LN, Shanafelt TD. Physician burnout: contributors, consequences and solutions. J Intern Med. 2018;283(6):516-529. doi: 10.1111/joim.12752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Spataro BM, Tilstra SA, Rubio DM, McNeil MA. The toxicity of self-blame: sex differences in burnout and coping in internal medicine trainees. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2016;25(11):1147-1152. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2015.5604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dillon EC, Stults CD, Deng S, et al. Women, younger clinicians’, and caregivers’ experiences of burnout and well-being during COVID-19 in a US healthcare system. J Gen Intern Med. 2022;37(1):145-153. doi: 10.1007/s11606-021-07134-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Templeton K, Bernstein CA, Sukhera J, et al. Gender-based differences in burnout: Issues faced by women physicians. National Academy of Medicine . May 30, 2019. Accessed August 22, 2023. https://nam.edu/gender-based-differences-in-burnout-issues-faced-by-women-physicians/

- 6.Murthy VH. Confronting health worker burnout and well-being. N Engl J Med. 2022;387(7):577-579. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2207252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.National Academy of Medicine, Action Collaborative on Clinician Well-Being and Resilience . National Plan for Health Workforce Well-Being. National Academies Press; 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jha AK, Iliff AR, Chaoui AA, Defossez S, Bombaugh MC, Miller YA. A crisis in health care: a call to action on physician burnout. Massachusetts Medical Society . March 28, 2019. Accessed August 22, 2023. https://www.massmed.org/Publications/Research,-Studies,-and-Reports/A-Crisis-in-Health-Care--A-Call-to-Action-on--Physician-Burnout/

- 9.Shanafelt TD, West CP, Dyrbye LN, et al. Changes in burnout and satisfaction with work-life integration in physicians during the first 2 years of the COVID-19 pandemic. Mayo Clin Proc. 2022;97(12):2248-2258. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2022.09.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fainstad T, Mann A, Suresh K, et al. Effect of a novel online group-coaching program to reduce burnout in female resident physicians: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(5):e2210752. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.10752 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Palamara K, Kauffman C, Chang Y, et al. Professional development coaching for residents: results of a 3-year positive psychology coaching intervention. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33(11):1842-1844. doi: 10.1007/s11606-018-4589-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Solms L, van Vianen A, Koen J, Theeboom T, de Pagter APJ, De Hoog M; Challenge & Support Research Network . Turning the tide: a quasi-experimental study on a coaching intervention to reduce burn-out symptoms and foster personal resources among medical residents and specialists in the Netherlands. BMJ Open. 2021;11(1):e041708. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-041708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mann A, Fainstad T, Shah P, et al. “We’re all going through it”: impact of an online group coaching program for medical trainees: a qualitative analysis. BMC Med Educ. 2022;22(1):675. doi: 10.1186/s12909-022-03729-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.US Department of Health and Human Services . Addressing health worker burnout: the US Surgeon General’s advisory on building a thriving health workforce. Current Priorities of the US Surgeon General. 2022. Accessed August 22, 2022. https://www.hhs.gov/surgeongeneral/priorities/health-worker-burnout/index.html

- 15.Deiorio NM, Carney PA, Kahl LE, Bonura EM, Juve AM. Coaching: a new model for academic and career achievement. Med Educ Online. 2016;21:33480. doi: 10.3402/meo.v21.33480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grant AM, Curtayne L, Burton G. Executive coaching enhances goal attainment, resilience and workplace well-being: a randomised controlled study. J Posit Psychol. 2009;4(5):396-407. doi: 10.1080/17439760902992456 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Palamara K, McKinley SK, Chu JT, et al. Impact of a virtual professional development coaching program on the professional fulfillment and well-being of women surgery residents: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Surg. 2023;277(2):188-195. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000005562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harte S, McGlade K. Developing excellent leaders: the role of executive coaching for GP specialty trainees. Educ Prim Care. 2018;29(5):286-292. doi: 10.1080/14739879.2018.1501770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dyrbye LN, Shanafelt TD, Gill PR, Satele DV, West CP. Effect of a professional coaching intervention on the well-being and distress of physicians: a pilot randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(10):1406-1414. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.2425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dyrbye LN, Gill PR, Satele DV, West CP. Professional coaching and surgeon well-being: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Surg. 2023;277(4):565-571. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000005678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.de Lasson L, Just E, Stegeager N, Malling B. Professional identity formation in the transition from medical school to working life: a qualitative study of group-coaching courses for junior doctors. BMC Med Educ. 2016;16:165. doi: 10.1186/s12909-016-0684-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Malling B, de Lasson L, Just E, Stegeager N. How group coaching contributes to organisational understanding among newly graduated doctors. BMC Med Educ. 2020;20(1):193. doi: 10.1186/s12909-020-02102-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boutron I, Altman DG, Moher D, Schulz KF, Ravaud P; CONSORT NPT Group . CONSORT statement for randomized trials of nonpharmacologic treatments: a 2017 update and a CONSORT extension for nonpharmacologic trial abstracts. Ann Intern Med. 2017;167(1):40-47. doi: 10.7326/M17-0046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pearl R. Dear new doctor: how to prevent burnout and find fulfillment. Forbes . Published August 18, 2016. Accessed August 29, 2022. https://www.forbes.com/sites/robertpearl/2016/08/18/dear-new-doctor-how-to-prevent-burnout-and-find-fulfillment/?sh=61c6400d1921

- 25.Wenger K, Strauss R. Consequences of physician burnout. Beyond Clinical Medicine. Posted September 4, 2019. Accessed August 29, 2023. https://www.beyondclinicalmedicine.org/e/beyond-clinical-medicine-episode-11-consequences-of-physician-burnout-%e2%80%93-dr-kip-wenger/

- 26.Mind Tools Content Team . Burnout self-test. MindTools . 2023. Accessed August 29, 2023. https://www.mindtools.com/auhx7b3/burnout-self-test

- 27.MindTools . Personal development plan. Mind Tools Store . 2023. Accessed August 29, 2023. https://store.mindtools.com/products/personal-development-plan?variant=30300852158557

- 28.Potter D. Online mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR). Palouse Mindfulness. Accessed August 29, 2023. https://palousemindfulness.com/

- 29.Short CE, Rebar AL, Plotnikoff RC, Vandelanotte C. Designing engaging online behaviour change interventions: a proposed model of user engagement. European Health Psychology Society . February 27, 2015. Accessed August 22, 2023. https://www.ehps.net/ehp/index.php/contents/article/view/763

- 30.Cole-Lewis H, Ezeanochie N, Turgiss J. Understanding health behavior technology engagement: pathway to measuring digital behavior change interventions. JMIR Form Res. 2019;3(4):e14052. doi: 10.2196/14052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maslach C, Jackson SE, Leiter MP. Maslach Burnout Inventory™ (MBI): license to administer. Mind Garden, Inc . 2023. Accessed August 23, 2023. https://www.mindgarden.com/maslach-burnout-inventory-mbi/765-mbi-license-to-administer.html?search_query=MBI&results=41

- 32.Maslach C, Jackson SE, Leiter MP. Maslach Burnout Inventory Manual. Consulting Psychologists Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shanafelt TD, Bradley KA, Wipf JE, Back AL. Burnout and self-reported patient care in an internal medicine residency program. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136(5):358-367. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-136-5-200203050-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Villwock JA, Sobin LB, Koester LA, Harris TM. Impostor syndrome and burnout among American medical students: a pilot study. J Int Assoc Med Sci Educ. 2016;7:364-369.doi: 10.5116/ijme.5801.eac4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mantri S, Lawson JM, Wang Z, Koenig HG. Identifying moral injury in healthcare professionals: The Moral Injury Symptom Scale-HP. J Relig Health. 2020;59(5):2323-2340. doi: 10.1007/s10943-020-01065-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Neff KD. The development and validation of a scale to measure self-compassion. Self Ident. 2003;2(3):223-250. doi: 10.1080/15298860309027 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Weziak-Bialowolska D, McNeely E, VanderWeele TJ. Flourish index and secure flourish index: validation in workplace settings. Cogent Psychol. 2019;6(1):1598926. doi: 10.1080/23311908.2019.1598926 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Stat Soc Series B Stat Methodol. 1995;57(1):289-300. doi: 10.1111/j.2517-6161.1995.tb02031.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stekhoven DJ, Bühlmann P. MissForest–non-parametric missing value imputation for mixed-type data. Bioinformatics. 2012;28(1):112-118. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shanafelt TD, Balch CM, Bechamps G, et al. Burnout and medical errors among American surgeons. Ann Surg. 2010;251(6):995-1000. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181bfdab3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shanafelt TD, Balch CM, Dyrbye L, et al. Special report: suicidal ideation among American surgeons. Arch Surg. 2011;146(1):54-62. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2010.292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Carullo PC, Ungerman EA, Metro DG, Adams PS. The impact of a smartphone meditation application on anesthesia trainee well-being. J Clin Anesth. 2021;75:110525. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2021.110525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brazier A, Larson E, Xu Y, et al. ‘Dear doctor’: a randomised controlled trial of a text message intervention to reduce burnout in trainee anaesthetists. Anaesthesia. 2022;77(4):405-415. doi: 10.1111/anae.15643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Weitzman RE, Wong K, Worrall DM, et al. Incorporating virtual reality to improve otolaryngology resident wellness: one institution’s experience. Laryngoscope. 2021;131(9):1972-1976. doi: 10.1002/lary.29529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Association of American Medical Colleges . 2022 Physician specialty data report: executive summary. January 2023. Accessed August 22, 2023. https://www.aamc.org/media/63371/download?attachment

- 46.US Department of Health and Human Services . Our epidemic of loneliness and isolation: the US surgeon general’s advisory on the healing effects of social connection and community. May 3, 2023. Accessed August 22, 2023. https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/surgeon-general-social-connection-advisory.pdf [PubMed]

- 47.Groves RM, Couper MP. Nonresponse in Household Interview Surveys. John Wiley & Sons; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Johnson TP, Lee G, Cho YI. Examining the association between cultural environments and survey nonresponse. Surv Pract. 2010;3(3):1-12. doi: 10.29115/SP-2010-0013 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial Protocol

eTable 1. Site Participation

eMethods. BT Coach Onboarding and Facets of BT Program

eTable 2. Participant Characteristics at Baseline by Survey Completion

eTable 3. Effect Sizes for Burnout and Impostor Syndrome

eTable 4. Intention to Treat Sensitivity Analysis: Mean Change in Response From Baseline Visit, Estimated From Linear Regression Adjusted for Baseline Value

Data Sharing Statement