Abstract

Tuberculosis (TB) remains a leading cause of infectious disease mortality and morbidity. Pyrazinamide (PZA) is a critical component of the first-line TB treatment regimen because of its sterilizing activity against non-replicating Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb), but its mechanism of action has remained enigmatic. PZA is a prodrug converted by pyrazinamidase encoded by pncA within Mtb to the active moiety, pyrazinoic acid (POA) and PZA resistance is caused by loss-of-function mutations to pyrazinamidase. We have recently shown that POA induces targeted protein degradation of the enzyme PanD, a crucial component of the coenzyme A biosynthetic pathway essential in Mtb. Based on the newly identified mechanism of action of POA, along with the crystal structure of PanD bound to POA, we designed several POA analogs using structure for interpretation to improve potency and overcome PZA resistance. We prepared and tested ring and carboxylic acid bioisosteres as well as 3, 5, 6 substitutions on the ring to study the structure activity relationships of the POA scaffold. All the analogs were evaluated for their whole cell antimycobacterial activity, and a few representative molecules were evaluated for their binding affinity, towards PanD, through isothermal titration calorimetry. We report that analogs with ring and carboxylic acid bioisosteres did not significantly enhance the antimicrobial activity, whereas the alkylamino-group substitutions at the 3 and 5 position of POA were found to be up to 5 to 10–fold more potent than POA. Further development and mechanistic analysis of these analogs may lead to a next generation POA analog for treating TB.

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction.

Tuberculosis (TB) is an ongoing threat to global public health, resulting in more deaths than any other infectious disease in the 21st century.1 An estimated one-fourth of the world’s population is infected by Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb),1 with highest prevalence amongst marginalized and impoverished sections of the population.1–2 The TB pandemic is further exacerbated by limited access to healthcare, co-infection with diseases such as HIV, and drug resistance.3 As a result, there is a need for novel TB drugs, particularly agents with sterilizing activity against persistent bacteria to prevent relapse and resistance development. Pyrazinamide (PZA), one of the first line drugs for the treatment of TB, can target Mtb persisters that are challenging to eliminate with conventional antibiotics and thus remain an important component of current and future TB treatment regimens.4–9

Following its discovery in the mid-20th century, PZA was found to possess intriguing antimycobacterial activity, displaying activity in vivo in a murine TB model, but lacking observable activity in vitro under standard culture conditions.7 The cause of this conditional susceptibility of Mtb has not been conclusively determined in the decades since its discovery, although several important insights have been achieved. PZA is known to act as a prodrug, requiring bioactivation to pyrazinoic acid (POA) by a mycobacterial amidase, PZase (encoded by pncA).7, 10–12 PZA is highly effective against Mtb and other members of the Mtb complex, including M. africanum, M. microti, and M. canetti; one interesting exception is M. bovis, which lacks PZase activity due to a C169G point mutation in pncA.13 Accordingly, 72–97% of PZA resistance in Mtb is associated with mutations to PZase.1, 12, 14–18 Further details on PZA’s mechanism of action have remained enigmatic, though multiple hypothesis have been proposed.19–25 One early theory postulated that POA acts as a protonophore, disrupting the electrochemical gradient required for ATP production.26–27 This theory was supported by several key findings: acidic pH appeared to be essential for the in vitro activity of PZA/POA, and the correlation between pH and antibacterial activity was similar to the relationship between pH and protonation state predicted by the Henderson-Hasselbach equation for POA.28 PZA was potentiated by known inhibitors of ATP synthesis, providing evidence of a shared target;27 as POA decreased ATP synthesis and the proton motive force (PMF) in Mtb membrane vesicles in vitro.29 However, subsequent findings seem to contradict this theory, including the activity of PZA in vitro at neutral pH in the presence of other activating factors, such as nutrient limitation, pncA overexpression, reduced culture temperature, or the use of minimal medium.30–32 Another early theory proposed fatty acid synthase I (FAS-I) as a putative target, citing evidence that a close analog, 5-Cl PZA, inhibited purified Mtb FAS-I in biochemical assays, as well as Mtb fatty acid production in vitro.21, 33–34 An early contradicting report by Boshoff et al. has largely undermined this theory by demonstrating that, while 5-Cl PZA does indeed inhibit fatty acid production in vitro, POA fails to recapitulate this activity and does not inhibit purified enzyme in biochemical assays.24 However, an intriguing recent report has provided evidence that both PZA and POA inhibit FAS-I, but each molecule binds the enzyme at a different site and functions through differing inhibitory modalities.35 Another controversial theory, proposed by Shi and colleagues, suggests that POA interferes with trans-translation through inhibition of ribosomal protein S1 (RpsA).36 In an initial report, the authors determined that rpsA overexpression conferred five-fold resistance to PZA in vitro, and a PZA-resistant clinical isolate without pncA mutations was confirmed to have a point mutation in rpsA.37–38 Little evidence of POA-RpsA interactions has been found with a variety of biophysical techniques, while demonstrating that the PZA-resistant rpsA mutant identified by the Shi et al. retains PZA susceptibility in vivo.25, 39–40 This has been refuted by Shi et al., with evidence that rpsA point mutations in wild-type Mtb cause weak PZA resistance.41 These early theories have provided important insights regarding the mechanism of action of PZA/POA, but also contain significant flaws or contradicting evidence and fail to fully explain the paradoxical activity.

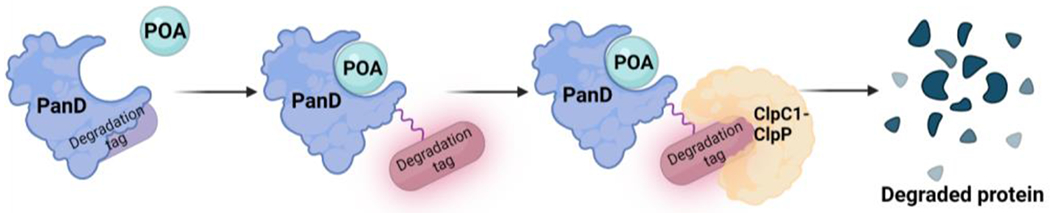

Recently, a new theory has emerged following reports that PZA inhibits mycobacterial coenzyme A (CoA) biosynthesis.42–46 POA resistant mutants, obtained by culturing in vitro, mapped to panD, which plays an essential role in CoA biosynthesis by catalyzing the decarboxylation of l-aspartate to β-alanine, the rate-limiting step in this pathway.46 POA binds to Mtb PanD with a dissociation constant (KD) of 6 μM and POA exposure results in selective depletion of downstream CoA pathway metabolites.43–47 In addition to acting as a weak PanD enzyme inhibitor, POA has been shown to induce PanD protein degradation, similar to the mechanism of proteolysis targeting chimeras (PROTACs) used to target intracellular proteins in eukaryotic cells.48 PROTACs are bifunctional molecules that contain a ligand for the protein of interest connected via a linker to another ligand that recruits an E3 ligase, ultimately leading to degradation via the human ubiquitin-proteasome system.46 POA on the other hand is a monovalent ligand, which binds to PanD exposing a buried degradation tag that stimulates targeted PanD degradation by the ClpC1-ClpP caseinolytic protease complex thereby depleting PanD and impairing the mycobacterial CoA biosynthetic pathway (Figure 1).48

Figure. 1.

POA binds to PanD and activates a degradation tag, causing degradation of PanD by the ClpC1-ClpP caseinolytic protease complex.

The structure-activity relationships (SAR) of POA have not been extensively explored (except for simple prodrugs) and virtually all of the previous literature has focused on modification of PZA guided by whole cell or animal studies.49–59 However, the SAR of PZA is not germane to POA since PZA analogs require bioactivation by PncA and the observed SAR of PZA reflects the narrow substrate specificity of PncA.60–61 (Aldrich lab, unpublished data)

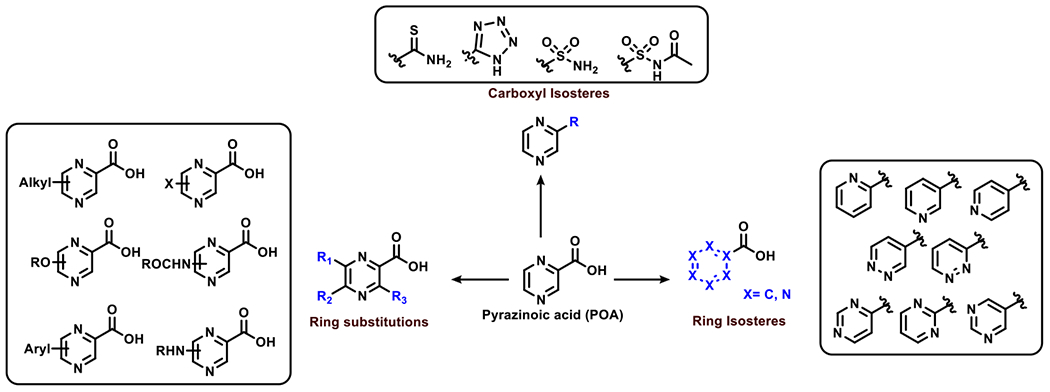

PanD is a reported target of POA, affording the potential for drug design using recently-reported PanD crystallographic structure for interpretation.57 However, POA does not operate only as a typical enzyme inhibitor; in addition binding to PanD induces a conformational change that alters the oligomeric state of the protein, leading to display of a C-terminal sequence recognized by the ClpP system.48 We hypothesize that the activity of POA can be enhanced by structural modifications made to the parent compound, yet we recognize that it is challenging to predict the impact of changes to inhibitor structure on PanD conformational dynamics. In pursuit of this goal, we have synthesized and screened an extensive set of POA analogs through substitutions at the pyrazine 3-, 5-, and 6-positions as well as by isosteric replacement of the carboxylic acid and pyrazine ring (Figure 2). Through this campaign, we successfully identified POA analogs with improved activity against the tubercle bacillus.

Figure 2.

Proposed scaffold modifications to POA

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Chemistry and synthesis.

We designed POA analogs by systematically modifying the ring through isosteric replacements made to the pyrazine ring. To evaluate the essentiality of the pyrazine core on microbial activity and to study the impact of altering the number and position of the nitrogen atoms in the ring, we deleted one nitrogen atom to form pyridine analogs (2–4). Next, we deleted both the nitrogen atoms to form benzoic acid (5); altered the position of the nitrogen atoms to form the pyrimidine and pyridazine analogs (6–10); and added a bulky benzene ring to form the bicyclic quinoxaline analog (11). Owing to the difficulty in the synthesis of the triazines and the poor predicted pharmacokinetic properties we did not study the analogs with more than two nitrogen atoms in the ring.62 For our next series, we performed some modifications to the carboxylic acid to evaluate its importance. We replaced the carboxylic acid with a tetrazole (12), a thioamide (13) sulfonamide (14), N-acetyl sulfonamide (15) and a ketone (16) to study the essentiality of carboxylic acid. Lastly, we looked at ring substitutions to the parent pyrazine-2-carboxylic acid molecule. We investigated the effects of various functional group substitutions at the 3, 5 and 6 positions. The substituents we evaluated were ring deactivating groups such as halides, mainly the chloride (17–19) and bromide (20–22), and ring activating groups such as amines (23–25), ethers (26–28), simple alkyl group (29–31), hydroxyl group (32–34) and aryl groups (35–40).

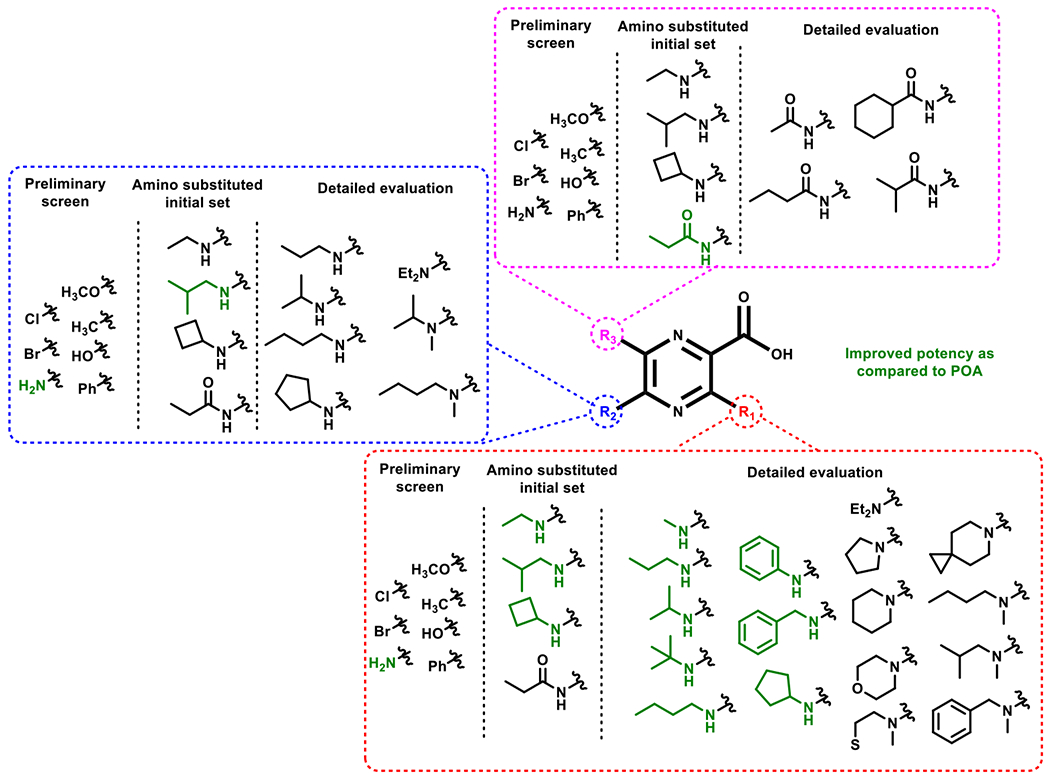

Based on the activity of the first set of compounds that were tested (1–40; Tables 1–3), we observed improved activity for the amine analogs as compared to POA and thus we further designed analogs such as the amines and amides (Figure 3). We elaborated upon this finding by additional 3, 5 and 6 (R1, R2, R3, Table 3)-amino analogs (41–52). The 6-amine substituted analogs were not well tolerated and hence only a small subset was evaluated, whereas, the 5 and 3 position substituents showed a moderate (3 to 10-fold) improvement in potency as compared to POA (1 mM to 0.1 mM), with significant improvement in potency observed for 3-position substituents over the 5-position substituents. Hence, amine substituents at 3-position (53–69; Table 4) were further studied, including secondary and tertiary alkyl amines, cycloalkyl amines and aryl amines, and a few representative amines were also explored for the 5-position (70–76; Table 5). To further expand our observations depending on the activity of amides as observed in the mono-substituted series, we also investigated a few simple alkyl and cycloalkyl amides (77–80; Table 5) at the 6-position.

Table 1:

Antimicrobial activity of POA ring bioisostere analogs against M. bovis BCG

|

MIC50 was determined using the broth dilution assay in Middlebrook 7H9 broth. POA (1) was included as a positive control and comparator. Means of two independent experiments are shown.

Table 3:

Antimicrobial activity of POA ring substituted analogs against M. bovis BCG

|

MIC50 was determined using the broth dilution assay in Middlebrook 7H9 broth. POA (1) was included as a positive control and comparator. Means of two independent experiments are shown.

Figure 3:

Sequential design of POA analogs.

Table 4:

Antimicrobial activity of substituted 3-amino POA analogs against M. bovis BCG

|

MIC50 was determined using the broth dilution assay in Middlebrook 7H9 broth. POA (1) was included as a positive control and comparator. Means of two independent experiments are shown.

Table 5:

Antimicrobial activity of substituted 5-amino and 6-amido POA analogs against M. bovis BCG

|

MIC50 was determined using the broth dilution assay in Middlebrook 7H9 broth. POA was included as a positive control and comparator (MIC50 = 1 mM). Means of two independent experiments are shown.

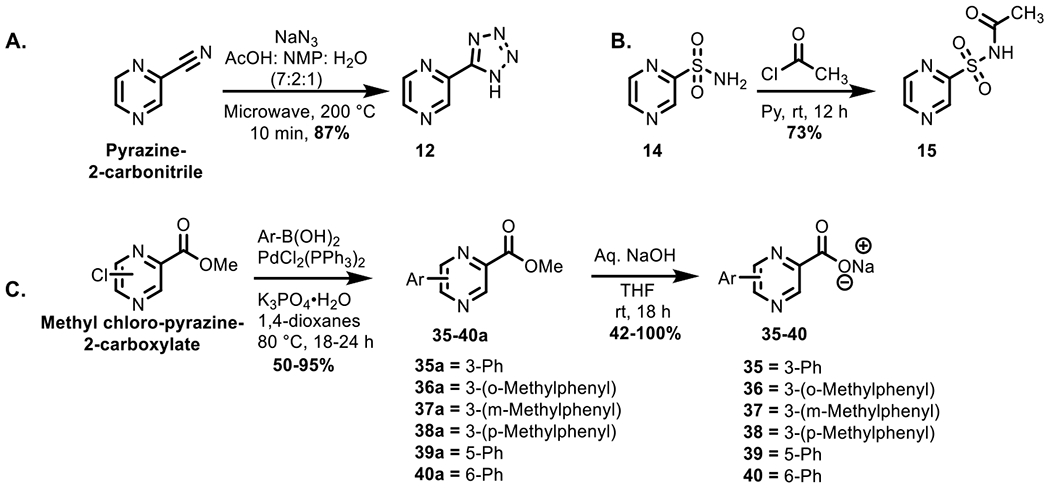

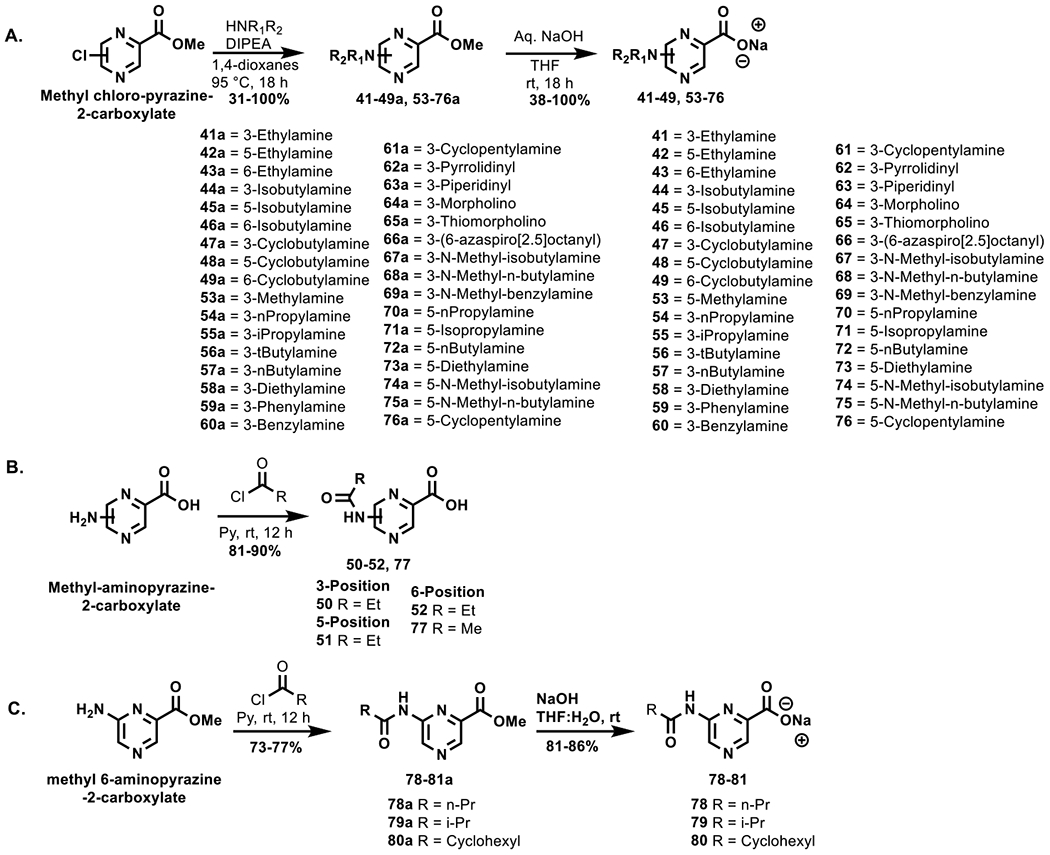

Our initial SAR explored pyrazinoic acid ring bioisosteres, carboxylic acid bioisosteres and substituted POA analogs, which were synthesized using conventional methods described herein. We synthesized most of the analogs (12, 15, 35–80), whereas a few of the commercially available analogs were purchased (1–11, 13–14, 16–34) and assayed for their identity and purity prior to biological evaluation (Table S1). We synthesized the tetrazole derivative 12 in 87% yield from 2-cyanopyrazine and sodium azide (NaN3) under microwave irradiation in a ternary solvent mixture of N-methyl pyrrolidone (NMP), acetic acid and water in 87% yield (Scheme 1A). Next, we prepared compound 15 through acetylation of sulfonamide derivative 14 in 73% yield (Scheme 1B). POA analogs containing aryl substituents (35–40) were synthesized by a two-step reaction involving a Suzuki-Miyaura coupling of the chloro-pyrazine ester and aryl boronic acids to produce the diaryl ester employing bis(triphenylphosphine)palladium(II) dichloride (10 mol%), and potassium phosphate monohydrate (Scheme 1C) with yields ranging between 50 and 95%. The esters were hydrolyzed to produce the sodium salts of the aryl-POA analogs in 42 to 100% yield. The methyl esters of POA amine analogs (41a–76a) were synthesized by nucleophilic substitution reactions performed at high temperatures to replace the chloride by the amines (Scheme 2A). While the methyl esters of 3-amino POA analogs resulted in over 65% yields, the methyl esters of the 5 and 6-amino POA analogs were low yielding (31–60%). The low yields were observed as result of the side reaction due to conversion of methyl ester to alkyl amine. Longer chain unbranched alkyl amines (n-butyl, n-propyl), in general, were low yielding as compared to their branched chain (isopropyl) or shorter chain (ethyl, methyl) homologues (42–49% v/s 59–79%, respectively). Ester hydrolysis of the POA amine analogs to the sodium salt resulted in variable yields (38–100%). While quantitative conversion was observed for a few analogs, most analogs had poor solubility in organic solvents and were lost during purification. The amido-analogs were prepared by coupling an acid chloride to the amine in the presence of a base such as pyridine. One step coupling of the acid unprotected amino-POA to the acyl chloride to produce amido-POA analogs, without additional steps for protection and deprotection of acid was attempted (Scheme 2B). While the ethionamido and propionamido-POA analogs were isolated in 81–90% yields, using the one step coupling method, the bulkier substituents such as the butyramido and cyclohexylamido analogs were challenging to purify and thus required the protection of the carboxylic acid prior to coupling (Scheme 2C). These amido-POA esters were subsequently hydrolyzed to produce the final analogs in 81–86% yields. On deprotection of the ester, sodium salts of the acids were isolated due to ease of purification as compared to the free acids.

Scheme 1:

A and B) Synthesis of carboxylic acid bioisosteres; C) Synthetic scheme for aryl coupling

Scheme 2:

A) Synthetic scheme for amine-substituted analogs; B) Synthetic scheme for amide-substituted analogs; C) Synthetic scheme for 6-amido analogs.

2.2. Anti-microbial activity.

POA analogs were assayed for their antimycobacterial potency using the biosafety level 2 compatible attenuated tubercle bacillus Mycobacterium bovis BCG Pasteur as surrogate for the virulent M. tuberculosis as described previously.63 Growth inhibition dose response curves were determined at a neutral pH, employing the broth dilution method using Middelbrook 7H9 broth and optical density as readout.45, 63 The activity is reported as the minimum inhibitory (MIC) concentration that inhibits fifty percent of growth (full concentration-response plots are provided in the supporting information, Tables S2–S7). All compounds were evaluated up to their maximum limit of solubility, hence the different upper limits for the reported MIC values. We systematically evaluated the SAR of the POA scaffold. First, isosteric replacement of the pyrazine ring through deletion and/or transposition of nitrogen at N-1 and N-4 was investigated (Table 1, entries 2–4). Replacement of either the N-1 or N-4 nitrogen atoms in 2 and 3 with a CH led to slightly enhanced activity (MIC = 0.7–0.9 mM), whereas deletion of both nitrogen atoms in benzoic acid (5) led to a modest reduction in potency (MIC = 2.2 mM). Transposition of the N-4 nitrogen to the 3-position in isonicotinic acid (4) was also less active (MIC = 2.7 mM). Next, we investigated the effects of altering the position of the two nitrogen atoms with respect to the carboxylic acid group with pyrimidine (6–8) and pyridazine analogs (9–10). We also tested a bicyclic ring such as a quinazoline analog (11) which showed a slight improvement in activity (0.7 mM) as compared to POA. While most of these ring modifications significantly reduced activity, a few modifications (2, 3, 11) retained activity. Among the heterocycle with two nitrogen atoms, pyrazine is the most potent in the series with a MIC of 1 mM. Owing to the difficulty in the synthesis of triazines and the poor predicted pharmacokinetic properties (predicted cLogP = −0.5 to −1) we did not study analogs with more than two nitrogen atoms in the ring. Taken together, these results indicate modification of the pyrazine ring is unable to dramatically improve potency, but that replacement of one nitrogen for a CH moiety is tolerated while pyrimidine and pyridazine constitutional isomers are weakly active to inactive.50

Next, we evaluated the role of the carboxylic acid moiety by replacing it with common bioisosteres (Table 2) including tetrazole (12), thioamide (13), sulfonamide (14) and N-acetyl sulfonamide (15), all of which were inactive or weakly active. The uncharged ketone isostere (16) also eliminated activity. Thus, we conclude that the carboxylic acid is required for potent activity and cannot be replaced with even conservative bioisosteres.

Table 2:

Antimicrobial activity of carboxylic acid modified analogs against M. bovis BCG

|

MIC50 was determined using the broth dilution assay in Middlebrook 7H9 broth. POA (1) was included as a positive control and comparator. Means of two independent experiments are shown.

Lastly, we sought to study substitution of the pyrazine ring (Table 3). Substitutions such as ring deactivating groups viz. as halides, mainly the chloride (17–19) and bromide (20–22), and ring activating groups such as amines (23–25), ethers (26–28), simple alkyl group (29–31), hydroxyl group (32–34) and aryl groups (35–40), mostly resulted in similar or reduced antimycobacterial potency as compared to the parent POA. Fortunately, 3- or 5-amino substitution (23–24) showed a slight improvement in activity over POA (0.8 mM vs. 1 mM). Interestingly, the 6-amino analog demonstrated reduced activity compared to its counterparts, a trend that was reversed for the chloro, methoxy, methyl and hydroxyl substituents (19, 28, 31, 34). Introduction of bulkier aryl substituents (35–40) unfortunately reduced the solubility of these compounds, likely due to increased lipophilicity. These analogs were less potent as compared to the unsubstituted POA. The 3-phenyl POA (35) was the most potent in the series with an MIC of 1.5 mM and hence a positional scan with a methyl group to the phenyl ring was evaluated. We observed an improvement in activity in the presence of a meta-methyl substituent (37) (0.8 mM). On the other hand, the ortho- methyl substituent (36) completed obliterated activity, which could be attributed to the steric hinderance caused by addition of the methyl group ortho to the pyrazine ring, and the para- methyl substituent (38) resulted in activity comparable to the parent POA (1 mM). The 5-phenyl POA (39) analog eliminated activity and the 6-phenyl POA (40) analog was nearly 2-fold less potent as compared to POA, and hence substituted phenyl groups were not evaluated at 5 and 6 positions.

A second series of compounds were designed based on the activity seen with the first set of compounds. Given the improved activity of the 3- and 5-amino analogs, a new set of analogs featuring additional elaboration on the amine were synthesized and evaluated. Mono-substitution with ethylamino (41–43), isobutylamino (44–46), cyclobutylamino (47–49) and propionamido (50–52) groups were evaluated at 3, 5 and 6 positions. For the aliphatic amine substituents such as the ethylamino and isobutylamino groups, the 3-amino (0.2–0.4 mM) and 5-amino analogs (0.4 mM) improved potency by 2.5–5 fold as compared to POA; the 3-cyclobutylamino analog (47) also demonstrated a better potency (0.4 mM), although incorporation of these substituents at the 5- and 6-positions substantially reduced activity. Consistent with the loss of activity seen with 6-amino-POA (25), 6-amino analogs generally displayed reduced activity compared to POA, excepting the potent 6-propionamido analog (52, 0.2 mM), which interestingly was more active than the corresponding 3- and 5-propionamido analogs (50/51, 1.5/3.5 mM, respectively) and was 5-fold more active in comparison to POA. This result suggests that an amide group at the 6-position may be able to form additional alkyl hydrophobic interactions with residues E43, I88, Y90, at the central tunnel of Mtb’s PanD.

To summarize, our initial screening identified 3, 5 and 6-amino substituents as amenable to modification. We synthesized additional analogs (Figure 3) to further explore these interactions. We observed most of the mono-alkyl amine substituents at 3-position had improved activity as compared to the parent amine substituent, with maximal potency for the branched isopropyl amine POA (55, <0.1 mM) followed by the isobutyl amine POA (44, 0.2 mM) and propylamine POA (54, 0.2 mM). The 3-cycloalkyl amine and 3-aryl amine analogs enhanced potency as compared to POA, with 3-benzylamine POA (60) showing the best potency amongst the series (MIC = 0.2 mM), whereas the cyclobutylamine (47), cyclopentylamine (61) and phenylamine (59) were equipotent with an MIC of 0.4 mM. This suggests that the activity is independent of the size of the ring but can be enhanced by increasing the length of the linker (methylene for 60). The 3-diethylamine POA (58) resulted in a loss of activity. Similar to the 3-diethylamine POA, the 3-pyrrolidine (62), 3-piperidine (63), 3-morpholine (64), 3-thiomorpholine (65) and the 3-6-azaspiro[2.5]octane (66) substituents abolished activity. Based on the potency of a few alkyl amine analogs, we selected a few analogs viz. the 3-isobutylamino POA (44), 3-n-butylamino POA (57) and 3-benzylamino POA (60) and synthesized the N-methyl analogs of these compounds (67–70). Consistent with our findings, most of these analogs obliterated activity, with surprising activity observed for N-Methyl-3-benzylamino POA (70, 0.7 mM). The loss of activity on substitution of the amine suggests that the proton may be essential for certain active site binding interactions. The benzyl group might be capable of forming additional stabilizing bonds as compared to other analogs making it capable of regaining potency on substitution of the amine. On evaluating the crystal structure of PanD bound to POA, reported by Sacchettini et al.,57 we observed a few residues that could potentially interact with the 3-aminosubstituents. These residues viz. N48, Pyr1 (cofactor Pyruvate binding - N48) and K9 have functional groups that could serve as H-bond acceptors, in particular, the N-terminal amino acid K9 amine was shown to serve as H-bond acceptor to the Y56-hydroxyl group and its mutation (K9A) resulted in loss of enzyme activity.63 3-position substitutions such as 54, 59 (Table 7) reveal that only smaller linear groups with an optimal size of three carbon length, n-propyl (54, Kd = 7 μM) have maintained micromolar binding. Further, extending the size of the 3-amino substituents to phenyl [59, Kd = 47 μM or 58, no binding (Table 7)] led to a reduction or abrogation of Mtb PanD binding. Additionally, the ‘NH’ extension on ortho to the acid group (viz. 3-position) was seen to maintain intramolecular H-bonding with the acid group of POA and could be critical for the geometry of the POA molecule, as N-N-disubstitutions at 3-position were not accommodated and sterically hindered the binding of 58 to Mtb PanD. This activity trend suggests that the active site may have a narrow pocket for binding to the 3-position substituents and only tolerates smaller 3-position substituents.

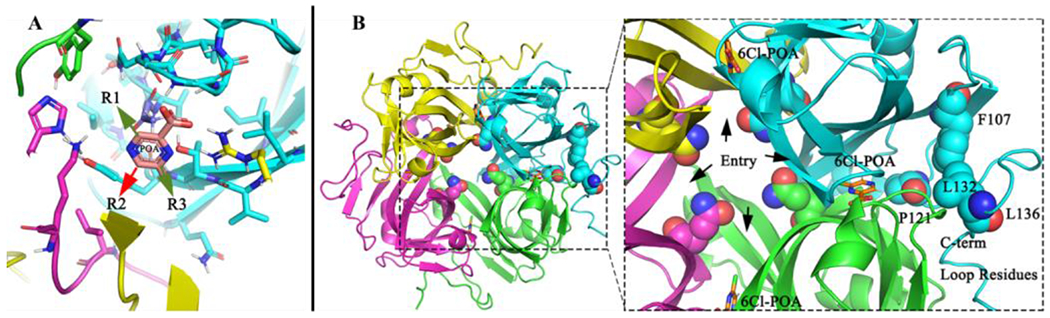

On further evaluating the 5-position substituents, we observed that 5-isobutylamine POA (45) and 5-butylamine POA (72) showed comparable activity to the 3-position analogs (47, 59, 61). Loss of potency was observed for the other secondary amines at 5-position, such as the ethylamine (42), n-propylamine (70), isopropylamine (71) as well as cyclobutylamine (48) and cyclopentylamine (76); activity was only observed with a 5-butyl amine substituent. Unexpected activity was observed in the case of the 5-diethylamine POA (73) which was equipotent to the parent POA. Owing to the intriguing activity of the 5-N,N-diethylamine POA (73), we prepared and evaluated the N-methyl derivatives (76–77) of the active alkylamine derivatives at 5 position viz. 5-isobutylamino POA (59) and 5-butylamine POA (72). We observed these tertiary amine substituents at the 5-position, retained the antimicrobial activity. These activity trends, when contrasted with 3-position, suggest that the active site may have a wide pocket for binding to the 5-position substituents to get accommodated towards the central tunnel and might not impose stringent requirements as the 3-position substitutions on POA. This is further corroborated by assessing the molecular interaction of bound POA-PanD complex (Figure 4A).57 The vicinity of the 5-position substituent was oriented into a wider cavity (central tunnel) outlined by residues Q43, Y90 (Figure 4B). These minor variations may partially explain, why the 5-position tertiary amide substituents retain potency, as they can be accommodated without steric hindrance. While the 3-position tertiary amines obliterate activity, due to steric hindrance.

Figure 4:

Cartoon model of PanD and POA. A) Cartoon Model showing the SAR points on POA-PanD ligand complex. B) Cartoon model revealing the tetrameric arrangement of Mtb PanD crystal structure (PDB 6P02). The zoomed subset highlights the probable entry of 6Cl-POA from the central tunnel lined by amino acids Q43 (spheres), while the overlay of C-terminal loop residues (highlighted in cyan spheres), from full length AlphaFold Mtb PanD homology model) show that C-terminal residues close the solvent accessibility to the ligand binding sites.

Next, to conclude screening of POA substituted analogs, we investigated the activity for the amide substituents at the 6-position due to its improved potency as observed in the first mini-series with propionamide. Similar straight chained and branched alkyl analogs (77-79), as well as a cycloalkyl analog (cyclohexyl, 80) were evaluated and they obliterated activity (Table 5). Thus, we observed that a 6-propionamide substituent is of optimal length for activity and all other amide substituents are not tolerated.

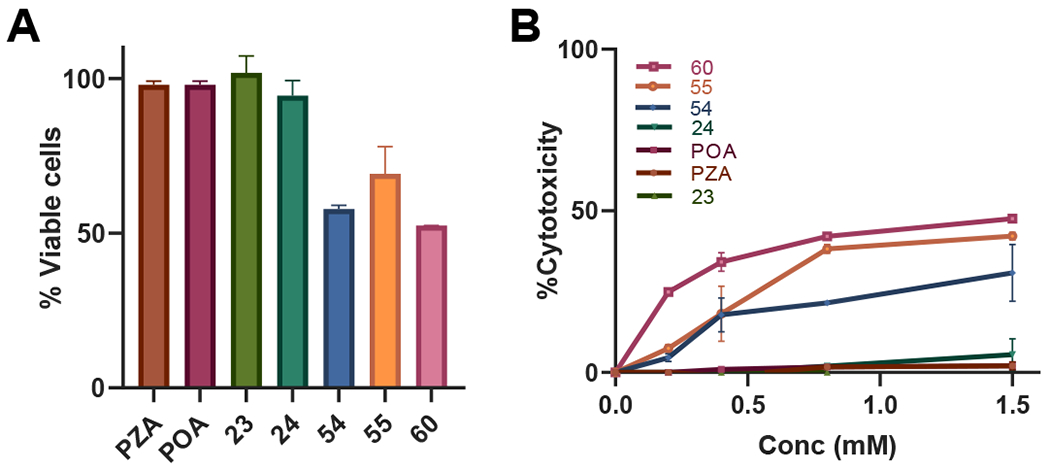

Lastly, we assessed whether POA and its analogs are cytotoxic, which could obfuscate the observed antibacterial activity. Cell viability was measured through XTT assays using cultured Vero cells upon exposure to POA, PZA and five potent POA analogs (23, 24, 54, 55, and 60) at increasing compound concentrations from 20 μM of up to 1.5 mM. Untreated cells were set at 100% and cell viability for the compounds was calculated with respect to the untreated cells. As shown in Figure 5A, cell viability at the maximal concentration tested (1.5 mM) was over 50% for the compounds evaluated. These studies suggest that these five compounds are slightly toxic to mammalian cells at high concentrations, as compared to PZA or POA, but have a low cytotoxicity at lower concentrations (Figure 5B).

Figure 5.

Cytotoxicity of PZA, POA and analogs 23, 23, 54, 55 and 60. Vero cells grown to confluence were exposed to compounds at various concentrations (20 μM to 1.5 mM) and cell viability was monitored as an indicator of cytotoxicity. A) Cell viability at the highest concentration tested (1.5 mM) for the reported compounds. B) Percent cytotoxicity at varying drug concentrations.

2.3. Binding assays

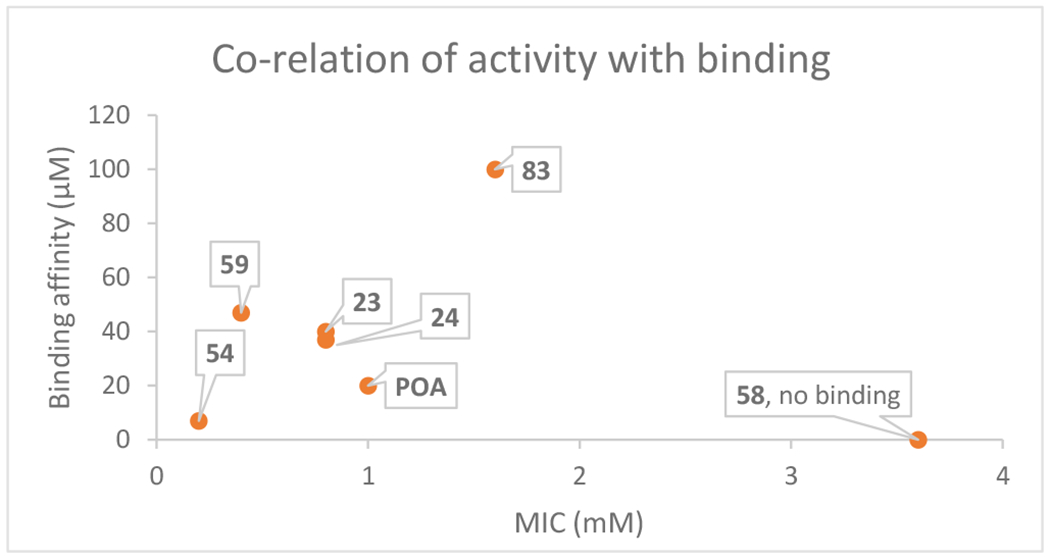

Having successfully identified new POA analogs with improved antimycobacterial activity, we sought to verify if this potency was due to PanD inhibition, rather than nonspecific off-target effects. To achieve this aim, we performed binding assays for a few active compounds using isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC). The compounds selected for this assay (1, 23, 24, 54, 55, 58, 59) were chosen on basis of their solubility, and only representative molecules were evaluated, to validate on-target binding. Amongst the compounds tested, we observed that most of the compounds that showed improved potency as compared to POA (23, 24, 59) were binding to PanD with a reduced affinity (37–47 μM) as compared to POA (1, 20 μM), whereas the compound with a loss of activity (58) did not bind at all (Table 6). Surprisingly, our best compound in the series (55), bound very weakly to PanD (> 100 μM). A plot of the binding affinities as a function of the MIC50 values (Figure 6) is scattered and suggests that there is no direct correlation between anti-TB activity and in vitro PanD binding affinity. Certain weak binders or non-binders also possess antimycobacterial potency and the activity may be attributed to any off-target activities caused by the analogs.

Table 6:

Susceptibility of M. bovis BCG wildtype and a representative POA-resistant M. bovis BCG strain to POA analogs, and ITC data of POA analogs for binding to PanD enzyme.

|

WT, wildtype; ND, not determined.

M. bovis BCG mutant POA2 was previously in vitro isolated and harbors a missense mutation in PanD, Leu132Arg45.

Figure 6:

Correlation of antimicrobial activity with ITC binding

To determine whether the analogs share a similar mechanism of action with POA, we tested a POA-resistant M. bovis BCG strain for cross-resistance to a few of the analogs (23, 24, 54, 55, 58, 59). M. bovis BCG mutant POA2 was previously isolated in vitro, and harbors a missense mutation in PanD, Leu132Arg.45 Susceptibility testing was done as previously described.64 POA was used as a positive control, and PanD mutant of M. bovis BCG showed strong levels of resistance (Table 6). The analogs 24, 54, 55 and 59 displayed a rather moderate shift in the growth inhibition potency against PanD mutant, M. bovis BCG POA2, while analog 23 showed a minimal shift in potency against the PanD mutant (Table 6). Although the moderate shift in potency toward the POA-resistant strains is suggestive of on-PanD target activity, the weak shifts in the growth inhibitory curves show no clear cross-resistance pattern indicating that most of the analogs may have off-target effects.

3. Conclusions

Inspired by recent developments highlighting a new possible mechanism for PZA/POA,46, 48 we designed and synthesized a systematic series of POA analogs. We chose to explore direct modulation of the POA scaffold, as analogs of the PZA prodrug form would still require PZase activation and as such might select for PZase compatibility over on-target activity. The goal of this study was to evaluate the antimycobacterial activity of POA analogs and to identify analogs with higher potency against Mtb. As described previously, we used the closely related but attenuated tubercle bacillus M. bovis BCG as test organism. Medicinal chemistry optimization based solely on growth inhibition of bacteria, by millimolar inhibitors, is challenging due to several factors, including potential involvement of multiple low affinity targets and differential cellular accumulation; small molecules such as POA are also more likely promiscuous and may exert off-target effects.65–66 Nonetheless, the SAR trends we observed corroborate previous reports regarding on-target activity observed with POA and PZA analogs.49–50, 63 We confirm that a nitrogen atom in the ring is essential for anti-TB activity, and best activity is observed with a pyridine-carboxylic acid with the aza-atom ortho to the carboxylic acid (as in picolinic acid analog 2, 0.7 mM). Amongst the aromatic rings containing two nitrogen atoms, viz. pyrazine, pyridazine and pyrimidine, pyrazinoic acid (1, 1 mM) has the optimal arrangement of heteroatoms for potent antimycobacterial activity, as other ring isosteres evaluated obliterated activity; congruent results were observed in earlier SAR studies performed on a PZA scaffold.50 We also observed that the carboxylic acid is essential for activity, as all other isosteric replacements were inactive, a trend which is similarly consistent with reported literature for bioactivated pyrazinamide analogs.49 These results validate that the carboxylic acid is essential in target binding as observed in the reported structure.57

The 3- and 5-amino POA analogs (23, 24) were found to be the most potent substituents in the series and were further evaluated. Zitko et al. previously evaluated N-alkyl-3-alkylamino PZA analogs and reported bulkier alkylamino substituents to have improved potency due to their enhanced lipophilicity, which could be attributed to their improved potential to penetrate the mycobacterial cell wall.67 Interestingly, in assessing similar POA analogs, we observed improved potency for most of the secondary amines evaluated. Alkyl, cycloalkyl and aromatic substitutions were well tolerated at the 3-position. However, di-substitution of the amine at the 3-position ablated activity, suggesting that a hydrogen bond donor may be important for forming key interactions in the active site. This observation was validated by binding studies that showed secondary amine analogs (54, 59) bind to PanD with variable affinities, but the representative 3-position tertiary amine analog (58) tested did not bind to PanD. We also found that 5-substitued analogs containing tertiary amines were equipotent or more potent than POA, suggesting that hydrogen bonding interactions with PanD may not be critical at this position. We report the most potent 5-position substituent was isobutylamine (45, 0.4 mM) as well as the n-butyl amine (72, 0.4 mM), which correlates with the previous results that found branched 5-alkylamino analogs to have improved potencies.68 Amongst the other analogs tested, we report a lower tolerance for substitution of the amine at 5-position as compared to 3-position.

A variety of substitutions were tolerated or even favored at the 3 and 5 position, while 6-substitution in our studies appears unfavorable. Sun et al showed 6-Cloro POA binds to PanD and suggested that 6-position would be favorable for modification.57 Consistent with their findings we observed 6-Cloro POA (19, 1 mM) derivative to be equipotent to POA and the 6-propionamido-POA (52, 0.2 mM) was 5–fold more potent as compared to POA, while all the other 6-amido analogs were inactive. This intriguing activity could be attributed to an additional interaction between these substituents and the active site of PanD or could merely be an observation due to off-target effects. Previously, 6-alkylamino analogs of PZA have been evaluated for their anti-mycobacterial activity and most of the derivatives evaluated were inactive against the strains tested, which aligns with our observation for 6-position POA analogs.57, 68 The observed SAR of POA analogs thus appears to largely reflect the varied substrate specificity for PanD active site.

This is the first effort to carry out systematic modifications of the POA scaffold. We identified certain next-generation POA analogs with 5 to 10-fold improved potency against whole cell mycobacteria. However, the overall whole cell activity remained in a moderate range, i.e., a potency ‘jump’ to single digit μM activities, was not achieved. The on-target activity of these molecules was evaluated by ITC binding studies and we observed no correlation between the binding affinity and the whole cell activity, and a few potent analogs were binding to PanD weakly. On assessing the cross resistance of a POA-resistant M. bovis BCG strain to a few POA analogs, we observed an altered microbial growth inhibition, suggestive of on-PanD target activity. However, the inability of the potent analogs to bind to PanD, accompanied by no clear cross-resistance to the PanD mutants indicate the possibility of off-target effects inhibiting the mycobacterial growth. Additionally, the previous evaluation of hepatic cytotoxicity of PZA, POA and a POA analog (33), show that POA and its analogs are more cytotoxic as compared to PZA.69 We assessed the cytotoxicity of a few representative POA analogs (23, 24, 54, 56 and 60) and our findings align with reported results and we observed these analogs to be cytotoxic (~50 %) at higher concentrations. Furthermore, due to the poor pharmacokinetic properties of the POA scaffold, additional optimizations focused on improvement of the solubility and drug-like properties of the molecules are required. In conclusion, we report that POA shows modest antimycobacterial activity and the whole-cell results suggest that the SAR is very sensitive to major modifications and showed modest effects or rendered the scaffold inactive. To verify that the observed activity is caused due to on-target effects and to negate the possibility of the whole cell activity being triggered by off-target effects, further evaluation of the molecular mechanism of action for these molecules is necessitated. Mechanistic investigations to validate the putative mechanism, beyond PanD binding is also essential. However, the high microbial inhibitory concentrations of these compounds, accompanied by their cytotoxic potential, make them poor drug candidates.

4. Materials and methods

4.1. Chemistry

4.1.1. Methods and instrumentation

All glassware was dried in a 150 °C oven overnight. All chemicals, solvents, and glassware were purchased from either Fisher Scientific (Pittsburg, Pennsylvania), Ambeed Inc (Arlington Heights, Illinois) or Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, Missouri). Dichloromethane (DCM), methanol (MeOH), and tetrahydrofuran (THF) were dispensed under Argon (Ar) using an Inert solvent purification system. All reactions were performed under an inert atmosphere of argon. The chemical reactions were tracked using fluorescent silica gel-coated TLC plates and the separated components were visualized using UV light (254 nm) or staining with Ninhydrin. Reaction purification was performed via column chromatography employing a Teledyne ISCO NextGen 300 CombiFlash system with the indicated solvent gradient; flash column silica gel cartridges were used for purifying intermediates, while RediSep® Rf Gold® Cyano cartridges (Teledyne ISCO) were used for purification of final carboxylic acid products. Percent purity analysis was performed using analytical high pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC) with a reversed-phase XSelect® CSH 5 μm C-18 4.6 × 150 mm LC column, with detection at 250 and 280 nm. A gradient method of 5% to 95% acetonitrile (MeCN) in water over 15 min at a flow rate of 1.0 ml/min was employed; both solvents were treated with either 0.1% formic acid or 20 mM ammonium acetate to assist resolution. All new compounds were also characterized and confirmed by HRMS. Mass spectra were acquired either on an Agilent 1200/AB Sciex® API 5500 QTrap LC/MS/MS, using electrospray ionization (ESI) or a single quadrupole analyzer or on an Agilent 7200/Accurate-Mass Q-TOF GC/MS, using electron impact (EI) or chemical ionization (CI). All final products were characterized by 1H NMR and 13C NMR on a Varian 7600-AS 400 MHz spectrometer or an Ascend™ 600 MHz Bruker spectrometer. 1H NMR spectra were referenced to residual CDCl3 (7.27 ppm), DMSO-d6 (2.50 ppm), or CD3OD (3.31 ppm) while 13C NMR spectra were referenced to CDCl3 (77.23 ppm), DMSO-d6 (39.51 ppm), or CD3OD (49.15 ppm). NMR chemical shift data are reported as follows: chemical shift, multiplicity (br = broad, s = singlet, d = doublet, t = triplet, q = quartet, m = multiplet, ABq = AB quartet, dm = doublet of multiplets), coupling constant, integration. Coupling constants are given in Hertz (Hz). Melting points (Mp) for solid final compounds were determined using a Thomas Hoover capillary melting point apparatus.

Compounds 1–11, 13–14, 16–34 were purchased and characterized to confirm their identity (HRMS) and purity (HPLC); the observed values are reported in table S1.

4.1.2. General amidation procedure

Substituted amino pyrazine derivative (1.0 equiv) was dissolved in pyridine (2 M) in a two-dram vial equipped with a pressure release cap. Acid chloride (1.0 equiv) was added slowly and the reaction mixture was stirred at 23 °C for 12 h and monitored for completion by TLC. The crude mixture was evaporated to remove excess pyridine and concentrated onto silica gel. Purification was performed using flash chromatography (EtOAc/Hexane, gradient method) and the major peak was collected.

4.1.3. General amination procedure

A solution of methyl chloro-2-pyrazinecarboxylate (1.0 equiv), diisopropylethylamine (3.0 equiv) and amine (2.0 equiv) in 1,4-dioxanes (0.2 M) in a sealed pressure flask was heated at95 °C and stirred overnight. The crude reaction mixture was diluted with DCM and concentrated onto celite. Purification was performed using flash chromatography (EtOAc/hexanes, gradient method) and the major peak was collected.

4.1.4. General Suzuki-Miyaura coupling procedure

Methyl chloro-2-pyrazinecarboxylate (1.0 equiv), aryl boronic acid (2.0 equiv), bis(triphenylphosphine)palladium(II) dichloride (10 mol%), and potassium phosphate monohydrate (2.0 equiv) were combined in a 2-dram vial, which was purged under vacuum and degassed with N2. Degassed 1,4-dioxanes (sonicated under vacuum, 5 mL/mmol of chloro-2-pyrazinecarboxylate) was added under positive pressure, and vial cap was replaced with a pressure release cap. The vial was heated at80 °C and stirred overnight. The reaction was cooled to rt, then concentrated and the residue partitioned between EtOAc and H2O and the organic layer separated. The aqueous layer was extracted with EtOAc (3 × 5 mL) and the combined organic layers were concentrated onto silica and purified by column chromatography (EtOAc/hexanes).

4.1.5. General saponification/ester hydrolysis procedure

Methyl ester (1.0 equiv) was dissolved in THF (0.1 M) at rt. Next, an aqueous NaOH solution (0.25 N, 2.50 equiv) was added slowly over 5 min, and the reaction was stirred at rt until completion as determined by TLC (25% MeOH in DCM; 1–18 h). The reaction mixture was evaporated to dryness in vacuo, concentrated onto celite, and purified by washing through a short silica column with a gradient of 0–50% MeOH in DCM.

4.1.6. General amidation procedure with free acid

Substituted amino pyrazine acid derivative (1.0 equiv) was dissolved in pyridine (2 M) in a two-dram vial equipped with a pressure release cap. Acid chloride (1.0 equiv) was added slowly and the reaction mixture was stirred at 23 °C for 12 h and monitored for completion by TLC. The crude mixture was evaporated to remove excess pyridine and concentrated onto silica gel. Purification was performed using flash chromatography (10-15% MeOH/DCM, gradient method) and the major peak was collected.

4.1.7. 2-(1H-Tetrazol-5-yl)pyrazine (12).

Pyrazine-2-carbonitrile (200 mg, 1.9 mmol, 1.0 equiv.), and NaN3 (371 mg, 5.7 mmol, 3.0 equiv.), were added to a 30 mL microwave vial equipped with a magnetic stir bar. Next, NMP/AcOH/H2O 7:2:1 (v/v) (5.0 mL) were added into it. The vial was sealed by capping with a Teflon septum and the sample was irradiated in a microwave at 200 °C for 10 min. After the reaction completion, the mixture was cooled to 50 °C by compressed air. The reaction mixture was extracted with saturated aqueous NaHCO3 (2 × 30 mL). Combined aqueous layer was washed with CHCl3 (3 × 45 mL) and was acidified to pH 5 with concentrated HCl, resulting in the precipitation of the tetrazole, which was collected by filtration. Tetrazole 12 was obtained in 246 mg, 87% yield as an off-white solid. Rf = 0.27 (1:7 Hexane–EtOAc); 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 9.40 (d, J = 1.3 Hz, 1H), 8.89–8.88 (m, 2H); HRMS (ESI) calcd for C5H3N6[M-H]− 147.0427 found: 147.0419 (error 5.4 ppm); Mp decomp. 154–157 °C, HPLC purity: 100%, tR = 6.0 min, k′ = 2.3.

4.1.8. N-(Pyrazin-2-ylsulfonyl)acetamide (15).

The title compound was obtained from compound 14 using the general method for amidation in 73% yield as a yellow solid. Rf = 0.18 (1:1 Hexane–EtOAc); 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 12.6 (br s, 1H), 9.26 (s, 1H), 9.10 (d, J = 1.4 Hz, 1H), 8.88–8.87 (m, 1H), 3.34 (br s, 1H), 1.98 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 169.7, 151.7, 148.8, 145.0, 143.7, 23.2. HRMS (ESI) calcd for C6H8N3O3S[M+H]+ 202.0281 found: 202.0281 (error 0 ppm); Mp decomp. 141–144 °C; HPLC purity: 99%, tR = 11.1 min, k′ = 5.2.

4.1.9. Methyl 3-(phenyl)pyrazine-2-carboxylic acid (35a).

The title compound was obtained from phenylboronic acid using the general method for Suzuki-Miyaura coupling in 86% yield as a yellow-brown oil.Rf = 0.27 (2:1 Hexane–EtOAc); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.76 (d, J = 2.3 Hz, 1H), 8.60 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 1H), 7.63 (ddd, J = 5.5, 2.9, 1.6 Hz, 2H), 7.51–7.45 (m, 3H), 3.84 (s, 3H). Spectral data matched previously reported values for this compound.5 HRMS (ESI) calcd for C12H11N2O2[M+H]+ 215.0815 found 215.0831 (error 7.4 ppm).

4.1.10. Sodium 3-(phenyl)pyrazine-2-carboxylate (35).

The title compound was obtained from 35a using the general method for ester hydrolysis in 66% yield as a white solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD) δ 8.78 (dd, J = 2.4, 1.5 Hz, 1H), 8.60 (dd, J = 2.6, 1.9 Hz, 1H), 7.73–7.65 (m, 2H), 7.52–7.45 (m, 3H); HRMS (ESI) calcd for C11H6N2O2 [M-H]− 199.0513, found 199.0502 (error 5.5 ppm); Mp decomp. > 280 °C; HPLC purity: 98%, tR = 8.9 min, k′ = 4.0.

4.1.11. Methyl 3-(o-tolyl)pyrazine-2-carboxylate (36a).

The title compound was obtained from o-tolylboronic acid using the general method for Suzuki-Miyaura coupling in 75% yield as an off-white solid. Rf = 0.60 (1:3 EtOAc–Hexanes); 1H NMR (400 MHz, 400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.80 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 1H), 8.67 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 1H), 7.36 (td, J = 7.4, 1.4 Hz, 1H), 7.32–7.25 (m, 2H), 7.18 (dd, J = 7.6, 1.3 Hz, 1H), 3.77 (s, 3H), 2.19 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 155.9, 145.7, 144.5, 142.4, 137.4, 135.9, 130.5, 129.3, 128.6, 125.8, 53.1, 19.8.HRMS (CI) calcd for C13H12N2O2 [M]+ 228.0893, found 228.0906 (error 5.5 ppm).

4.1.12. Sodium 3-(o-tolyl)pyrazine-2-carboxylate (36).

The title compound was obtained from 36a using the general method for ester hydrolysis in 92% yield as a tan solid. Rf = 0.14 (9:1 CH2Cl2–MeOH); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD) δ 8.56 (d, J = 2.6 Hz, 1H), 8.50 (d, J = 2.6 Hz, 1H), 7.39–7.34 (m, 1H), 7.33–7.24 (m, 2H), 7.21 (td, J = 7.3, 1.7 Hz, 1H), 2.23 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, CD3OD) δ 173.6, 155.2, 153.3, 143.3, 143.0, 139.0, 137.8, 131.3, 130.3, 129.7, 126.4, 20.1; HRMS (ESI) calcd for C12H9N2O2 [M-H]− 213.0670, found 213.0684 (error 6.6 ppm); Mp decomp. > 280 °C; HPLC purity: 96%, tR = 9.1 min, k′ = 4.2.

4.1.13. Methyl 3-(m-tolyl)pyrazine-2-carboxylate (37a).

The title compound was obtained from methyl 3-chloropyrazinoate and m-tolylboronic acid using the general method for Suzuki-Miyaura coupling in 89% yield as a light-yellow oil. Rf = 0.30 (1:3 EtOAc–Hexanes); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.75 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 1H), 8.58 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 1H), 7.51–7.45 (m, 1H), 7.38–7.25 (m, 3H), 3.84 (s, 3H), 2.43 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 166.8, 153.7, 145.2, 144.5, 141.6, 138.5, 136.9, 130.6, 129.1, 128.4, 125.6, 52.9, 21.4; HRMS (ESI) calcd for C13H13N2O2[M+H]+ 229.0972, found 229.0963 (error 3.9 ppm).

4.1.14. Sodium 3-(m-tolyl)pyrazine-2-carboxylate (37).

The title compound was obtained from 37a using the general method for ester hydrolysis in 90% yield as a tan solid. Rf = 0.10 (9:1 CH2Cl2–MeOH); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD) δ 8.58 (s, 1H), 8.43 (s, 1H), 7.70 – 7.60 (m, 3H), 7.26 (s, 1H), 2.39 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, CD3OD) δ 158.3, 149.2, 142.4, 141.0, 137.7, 131.7, 131.6, 129.5, 129.0, 127.8, 125.5, 20.1; HRMS (ESI) calcd for C12H9N2O2 [M-H]−: 213.0670, found: 213.0678 (error 3.8 ppm); Mp decomp. 247– 249 °C; HPLC purity: 99%, tR = 9.8 min, k′ = 6.5.

4.1.15. Methyl 3-(p-tolyl)pyrazine-2-carboxylate (38a).

The title compound was obtained from methyl 3-chloropyrazinoate and p-tolyl-boronic acid using the general method for Suzuki-Miyaura coupling in 87% yield as a light-yellow oil. Rf = 0.27 (1:3 EtOAc–Hexanes); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.74 (d, J = 3.8 Hz, 1H), 8.56 (d, J = 3.9 Hz, 1H), 7.53 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 2H), 7.29 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H), 3.86 (s, 3H), 2.42 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 166.9, 153.6, 145.3, 144.2, 141.4, 140.0, 134.1, 129.4, 128.4, 53.0, 21.4.; HRMS (ESI) calcd for C13H13N2O2[M+H]+ 229.0972, found 229.0951 (error 6.9 ppm).

4.1.16. Sodium 3-(p-tolyl)pyrazine-2-carboxylate (38).

The title compound was obtained from 38a using the general method for ester hydrolysis in 91% yield as a tan solid. Rf = 0.11 (9:1 CH2Cl2–MeOH); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD) δ 8.55 (d, J = 2.6 Hz, 1H), 8.40 (d, J = 2.6 Hz, 1H), 7.77 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 2H), 7.26 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 2H), 2.38 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (151 MHz, CD3OD) δ 173.3, 152.8, 149.8, 142.4, 140.8, 139.1, 134.7, 128.6, 128.3, 19.9; HRMS (ESI) calcd for C12H9N2O2 [M-H]− 213.0670, found 213.0679 (error 4.2 ppm); Mp decomp. >280 °C; HPLC purity: 96%, tR = 9.8 min, k′ = 4.5.

4.1.17. Methyl 5-(phenyl)pyrazine-2-carboxylate (39a).

The title compound was obtained from methyl 6-chloropyrazinoate phenylboronic acid using the general method for Suzuki-Miyaura coupling in 87% yield as a yellow solid. Rf = 0.52 (1:2 EtOAc–Hexanes); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 9.34 (s, 1H), 9.13 (s, 1H), 8.15–8.06 (m, 2H), 7.60–7.50 (m, 3H), 4.06 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 155.3, 145.7, 141.4, 135.2, 131.0, 129.3, 129.2, 127.6, 127.5, 53.1; HRMS (ESI) calcd for C12H11N2O2[M+H]+ 215.0815 found 215.0827 (error 5.6 ppm).

4.1.18. Sodium 5-(phenyl)pyrazine-2-carboxylate (39).

The title compound was obtained from 39a using the general method for ester hydrolysis in 64% as a white solid. Rf = 0.25 (9:1 CH2Cl2–MeOH); 1H NMR (500 MHz, CD3OD) δ 9.22 (d, J = 1.5 Hz, 1H), 9.10 (d, J = 1.6 Hz, 1H), 8.15–8.09 (m, 2H), 7.59–7.48 (m, 3H); 13C NMR (126 MHz, CD3OD) δ 169.5, 155.2, 149.9, 145.8, 141.9, 137.4, 131.2, 130.1, 128.3; HRMS (ESI) calcd for C11H6N2O2 [M-H]− 199.0513, found 199.0522 (error 4.5 ppm); Mp decomp. > 230 °C; HPLC purity: 100%, tR = 8.9 min, k′ = 4.0.

4.1.19. Methyl 6-phenylpyrazine-2-carboxylate (40a).

The title compound was obtained from methyl 6-chloropyrazinoate phenylboronic acid using the general method for Suzuki-Miyaura coupling in 87% yield as a yellow solid. Rf = 0.52 (1:2 EtOAc–Hexanes); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 9.20 (s, 1H), 9.17 (s, 1H), 8.12–8.02 (m, 2H), 7.57–7.45 (m, 3H), 4.04 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 164.7, 152.5, 144.8, 143.9, 142.6, 135.4, 130.5, 129.2, 127.3, 53.1; HRMS (EI) calcd for C12H10N2O2 [M]+ 214.0737, found 214.0740 (error 1.4 ppm).

4.1.20. Sodium 6-phenylpyrazine-2-carboxylate (40).

The title compound was obtained from 40a using the general method for ester hydrolysis in 45% yield as a white solid. Rf = 0.86 (95:5 CH2Cl2–MeOH); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD) δ 9.06 (s, 1H), 9.00 (s, 1H), 8.07 (d, J = 7.3 Hz, 2H), 7.50–7.37 (m, 3H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, CD3OD) δ 169.9, 152.0, 149.4, 142.9, 142.0, 136.2, 129.6, 128.6, 127.0; HRMS (ESI) calcd for C11H6N2O2 [M-H]− 199.0513, found 199.0521 (error 4.0 ppm); Mp decomp.>280 °C; HPLC purity: 99%, tR = 10.0 min, k′ = 4.7.

4.1.21. Methyl 3-(ethylamino)pyrazine-2-carboxylate (41a).

The title compound was obtained from Methyl 3-chloropyrazinoate and ethylamine using the general method for amination in 89% yield as a yellow solid. Rf = 0.18 (1:3 EtOAc–Hexanes); 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.17 (d, J = 2.2 Hz, 1H), 7.87 (s, 1H), 7.79 (d, J = 2.2 Hz, 1H), 3.90 (s, 3H), 3.47 (qd, J = 7.1, 5.1 Hz, 2H), 1.22 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (151 MHz, CDCl3) δ 167.3, 155.4, 147.5, 131.2, 52.7, 35.6, 14.7; HRMS (EI) calcd for C8H11N3O2 [M]+ 181.0846, found 181.0843 (error 1.8 ppm).

4.1.22. Sodium 3-(ethylamino)pyrazine-2-carboxylate (41).

The title compound was obtained from 41a using the general method for ester hydrolysis in 87% yield as a white solid. Rf = 0.34 (9:1 CH2Cl2–MeOH); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD) δ 7.87 (d, J = 2.6 Hz, 1H), 7.57 (d, J = 2.6 Hz, 1H), 3.33 (q, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 1.16 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, CD3OD) δ 171.0, 155.1, 143.1, 133.8, 129.1, 34.8, 13.5; HRMS (ESI) calcd for C7H9N3O2Na2 [M+2Na]+ 212.0456, found 212.0471 (error 8.0 ppm); Mp 133–136 °C; HPLC purity: 99% tR = 10.1 min, k′ = 2.1.

4.1.23. Methyl 5-(ethylamino)pyrazine-2-carboxylate (42a).

The title compound was obtained from methyl 3-chloropyrazinoate and ethylamine using the general method for amination in 61% yield as a yellow solid. Rf = 0.08 (1:3 EtOAc–Hexanes); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.77 (s,1H), 7.89 (s, 1H), 5.08 (s, 1H), 3.95 (s, 3H), 3.49 (qd, J = 7.2, 5.5 Hz, 2H), 1.30 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 165.3, 155.5, 145.9, 139.7, 131.3, 52.3, 36.4, 14.5; HRMS (ESI) calcd for C8H12N3O2[M+H]+ 182.0924, found 182.0928 (error 2.2 ppm).

4.1.24. Sodium 5-(ethylamino)pyrazine-2-carboxylate (42).

The title compound was obtained from 42a using the general method for ester hydrolysis in 84% yield as a white solid. Rf = 0.14 (9:1 CH2Cl2–MeOH); 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 8.60 (s, 1H), 7.87 (s, 1H), 3.38 (q, J = 7.3 Hz, 2H), 1.23 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (151 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 171.2, 155.3, 143.4, 141.7, 131.8, 35.4, 13.2; HRMS (ESI) calcd for C7H10N3O2 [M+H]+ 168.0768, found 168.0777 (error 5.4 ppm); Mp decomp. 243–245 °C; HPLC purity: 99%, tR = 7.7 min, k′ = 3.5.

4.1.25. Methyl 6-(ethylamino)pyrazine-2-carboxylate (43a).

The title compound was obtained from methyl 6-chloropyrazinoate and ethylamine using the general method for amination in 34% yield as a yellow solid. Rf = 0.33 (1:2 EtOAc–Hexanes); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.50 (s, 1H), 8.03 (s, 1H), 3.95 (s, 3H), 3.41 (q, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 1.27 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 165.2, 153.7, 140.3, 134.3, 133.9, 52.8, 36.6, 14.5; HRMS (EI) calcd for C8H11N3O2 [M]+ 181.0846, found 181.0851 (error 2.6 ppm).

4.1.26. Sodium 6-(ethylamino)pyrazine-2-carboxylate (43).

The title compound was obtained from 43a using the general method for ester hydrolysis in 87% yield as a white solid. Rf = 0.08 (95:5 CH2Cl2–MeOH); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD) δ 8.32 (s, 1H), 7.89 (s, 1H), 3.35 (d, J = 7.4 Hz, 2H), 1.27 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (151 MHz, CD3OD) δ 171.3, 160.1, 154.9, 147.8, 130.6, 35.3, 13.5; HRMS (ESI) calcd for C7H8N3O2 [M-H]− 166.0622, found 166.0625 (error 1.8 ppm); Mp decomp.>280 °C; HPLC purity: 99% tR = 9.4 min, k′ = 4.2.

4.1.27. Methyl 3-(isobutylamino)pyrazine-2-carboxylate (44a).

The title compound was obtained from methyl 3-chloropyrazinoate and isobutylamine using the general method for amination in 31% yield as a yellow solid. Rf = 0.25 (1:3 EtOAc–Hexanes); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.21 (d, J = 2.1 Hz, 1H), 8.08 (s, 1H), 7.84 (d, J = 2.3 Hz, 1H), 3.97 (s, 3H), 3.34 (dd, J = 6.9, 5.6 Hz, 2H), 1.94 (dp, J = 13.4, 6.7 Hz, 1H), 0.99 (d, J = 6.7 Hz, 6H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 167.4, 155.7, 147.4, 131.1, 124.0, 52.7, 48.1, 28.2, 20.3; HRMS (ESI) calcd for C10H16N3O2[M+H]+ 210.1237, found 210.1227 (error 5.7 ppm).

4.1.28. Sodium 3-(isobutylamino)pyrazine-2-carboxylate (44).

The title compound was obtained from 44a using the general method for ester hydrolysis in 97% yield as an off-white solid. Rf = 0.10 (9:1 CH2Cl2–MeOH); 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 10.06 (t, J = 5.7 Hz, 1H), 7.88 (d, J = 2.6 Hz, 1H), 7.53 (d, J = 2.6 Hz, 1H), 3.19–3.11 (m, 2H), 1.87–1.76 (m, 1H), 0.91 (d, J = 6.7 Hz, 6H); 13C NMR (126MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 168.1, 155.5, 142.2, 135.6, 128.8, 47.4, 27.8, 20.3; HRMS (ESI) calcd for C9H12N3O2 [M-H]− 194.0935, found 194.0944 (error 4.6 ppm); Mp decomp.> 280 °C; HPLC purity: 100%, tR = 6.8 min, k′ = 2.9.

4.1.29. Methyl 5-(isobutylamino)pyrazine-2-carboxylate (45a).

The title compound was obtained from methyl 5-chloropyrazinoate and isobutylamine using the general method for amination in 53% yield as a yellow solid. Rf = 0.08 (1:3 EtOAc–Hexanes); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.76 (s, 1H), 7.91 (s, 1H), 5.18 (s, 1H), 3.94 (s, 3H), 3.31–3.24 (m, 2H), 1.93 (dp, J = 13.4, 6.7 Hz, 1H), 1.00 (d, J = 6.7 Hz, 6H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 165.2, 154.0 140.2, 134.1, 133.9, 52.8, 49.4, 28.3, 20.2; HRMS (ESI) calcd for C10H16N3O2[M+H]+ 210.1237, found 210.1225 (error 4.8 ppm).

4.1.30. Sodium 5-(isobutylamino)pyrazine-2-carboxylate (45).

The title compound was obtained from 45a using the general method for ester hydrolysis in 91% yield as an orange solid. Rf = 0.13 (9:1 CH2Cl2–MeOH); 1H NMR (500 MHz, CD3OD) δ 8.62 (s, 1H), 7.90 (s, 1H), 3.22 (d, J = 6.9 Hz, 2H), 1.92 (hept, J = 6.7 Hz, 1H), 0.98 (d, J = 6.7 Hz, 6H); 13C NMR (126 MHz, CD3OD) δ 170.1, 157.5, 145.8, 133.7, 29.3, 20.6; HRMS (ESI) calcd for C9H12N3O2 [M-H]− 194.0935, found 194.0948 (error 6.7 ppm); Mp: 125 °C; HPLC purity: 99%, tR = 8.7 min, k′ = 3.3.

4.1.31. Methyl 6-(isobutylamino)pyrazine-2-carboxylate (46a).

The title compound was obtained from methyl 6-chloropyrazinoate and isobutylamine using the general method for amination in 31% yield as a yellow solid. Rf = 0.12 (1:3 EtOAc–Hexanes); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.50 (s, 1H), 8.05 (s, 1H), 5.05 (s, 1H), 3.96 (s, 3H), 3.24–3.15 (m, 2H), 1.89 (dq, J = 13.3, 6.7 Hz, 1H), 0.99 (d, J = 6.7 Hz, 6H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 165.2, 154.0 140.2, 134.1, 133.9, 52.8, 49.4, 28.3, 20.2; HRMS (EI) calcd for C10H15N3O2 [M]+ 209.1159, found 209.1147 (error 5.6 ppm).

4.1.32. Sodium 6-(isobutylamino)pyrazine-2-carboxylate (46).

The title compound was obtained from 46a using the general method for ester hydrolysis in 85% yield as a white solid. Rf = 0.33 (95:5 CH2Cl2–MeOH); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD) δ 8.20 (s, 1H), 7.84 (s, 1H), 3.21 (d, J = 5.3 Hz, 2H), 1.94–1.83 (m, 1H), 0.97 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, 6H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, CD3OD) δ 171.2, 160.1, 155.1, 147.6, 130.7, 61.4, 28.0, 19.2; HRMS (ESI) calcd for C9H12N3O2[M-H]− 194.0935, found 194.0937 (error 1.0 ppm); Mp decomp.197–201 °C; HPLC purity: 97%, tR = 9.4 min, k′ = 4.2.

4.1.33. Methyl 3-(cyclobutylamino)pyrazine-2-carboxylate (47a).

The title compound was obtained from methyl 3-chloropyrazinoate and cyclobutylamine using the general method for amination in 67% yield as an off-white solid. Rf = 0.55 (1:1 EtOAc–Hexanes); 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.15 (d, J = 2.2 Hz, 1H), 8.10–7.98 (m, 1H), 7.80 (d, J = 2.3 Hz, 1H), 4.54–4.43 (m, 1H), 3.91 (s, 3H), 2.43–2.33 (m, 2H), 1.97–1.85 (m, 2H), 1.83–1.67 (m, 2H); 13C NMR (151 MHz, CDCl3) δ 167.3, 154.5, 147.5, 131.5, 124.0, 52.7, 45.9, 31.3, 15.4; HRMS (EI) calcd for C10H13N3O2 [M]+ 207.1002, found 207.0999 (error 1.6 ppm).

4.1.34. Sodium 3-(cyclobutylamino)pyrazine-2-carboxylate (47).

The title compound was obtained from 47a using the general method for ester hydrolysis in 86% yield as a white solid. Rf = 0.55 (9:1 CH2Cl2–MeOH); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD) δ 7.85 (d, J = 2.6 Hz, 1H), 7.58 (d, J = 2.6 Hz, 1H), 4.34 (p, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 2.32 (dtt, J = 12.8, 8.0, 2.6 Hz, 2H), 1.94–1.84 (m, 1H), 1.78–1.64 (m, 2H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, CD3OD) δ 170.9, 154.1, 143.2, 133.5, 129.4, 45.6, 30.8, 14.8; HRMS (ESI) calcd for C9H11N3O2Na2[M+2Na]+ 238.0563, found 238.0566 (error 1.5 ppm); Mp decomp.>280 °C; HPLC purity: 99%, tR = 10.1 min, k′ = 4.6.

4.1.35. Methyl 5-(cyclobutylamino)pyrazine-2-carboxylate (48a).

The title compound was obtained from methyl 5-chloropyrazinoate and cyclobutylamine using the general method for amination in 70% yield as a white solid. Rf = 0.33 (1:1 EtOAc–Hexanes); 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.68 (d, J = 1.4 Hz, 1H), 7.79 (d, J = 1.5 Hz, 1H), 5.72 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 4.41–4.19 (m, 1H), 3.87 (s, 3H), 2.39 (dddd, J = 11.8, 10.1, 7.5, 2.9 Hz, 2H), 1.90 (qd, J = 9.5, 2.8 Hz, 2H), 1.79–1.66 (m, 2H); 13C NMR (151 MHz, CDCl3) δ 165.3, 154.7, 145.9, 131.2, 52.2, 46.6, 31.0, 15.2; HRMS (EI) calcd for C10H13N3O2 [M]+ 207.1002, found 207.1004 (error 1.0 ppm).

4.1.36. Sodium 5-(cyclobutylamino)pyrazine-2-carboxylate (48).

The title compound was obtained from 48a using the general method for ester hydrolysis in 84% yield as a yellow solid.Rf = 0.12 (9:1 CH2Cl2–MeOH); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD) δ 8.64 (d, J = 1.3 Hz, 1H), 7.87 (d, J = 1.3 Hz, 1H), 4.41 (q, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 2.43 (dtd, J = 13.2, 7.4, 3.0 Hz, 2H), 2.16–1.98 (m, 2H), 1.89–1.75 (m, 2H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, CD3OD) δ 171.2, 154.4, 143.6, 136.1, 131.7, 46.1, 30.3, 14.6; HRMS (ESI) calcd for C9H11N3O2[M+2Na]+ 238.0563, found 238.0545 (error 7.7 ppm); Mp decomp.>280 °C; HPLC purity: 96%, tR = 8.2 min, k′ = 4.5.

4.1.37. Methyl 6-(cyclobutylamino)pyrazine-2-carboxylate (49a).

The title compound was obtained from methyl 6-chloropyrazinoate and cyclobutylamine using the general method for amination in 31% yield as a yellow solid. Rf = 0.19 (1:2 EtOAc–Hexanes); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.54 (s, 1H), 7.96 (s, 1H), 5.15 (d, J = 6.9 Hz, 1H), 4.23 (h, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H), 3.97 (s, 3H), 2.52–2.43 (m, 2H), 1.96–1.75 (m, 4H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 166.3, 159.7, 138.0, 134.0, 131.6, 52.9, 47.0, 31.0, 15.1; HRMS (EI) calcd for C10H13N3O2[M+H]+ 208.1081, found 208.1078 (error 1.4 ppm).

4.1.38. Sodium 6-(cyclobutylamino)pyrazine-2-carboxylate (49).

The title compound was obtained from 49a using the general method for ester hydrolysis in 82% yield as an off-white solid. Rf = 0.08 (95:5 CH2Cl2–MeOH); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD) δ 8.25 (d, J = 1.3 Hz, 1H), 7.76 (d, J = 1.3 Hz, 1H), 4.39 (t, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H), 2.46–2.35 (m, 2H), 1.91 (td, J = 14.9, 12.5, 7.3 Hz, 2H), 1.84–1.73 (m, 2H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, CD3OD) δ 171.0, 153.8, 147.6, 131.2 (d, J = 53.6 Hz), 63.3, 30.5, 23.9, 14.4; HRMS (ESI) calcd for C9H11N3O2 [M-H]− 192.0779, found 192.0777 (error 1.0 ppm); Mp decomp. 200–205 °C; HPLC purity: 95%, tR = 8.5 min, k′ = 3.7.

4.1.39. Methyl 3-propionamidopyrazine-2-carboxylate (50a).

The title compound was obtained using general method for amidation in 77% yield as a yellow solid. Rf = 0.20 (3:1 EtOAc–Hexanes); 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 10.90 (s, 1H), 8.62 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 1H), 8.47 (d, J = 2.3 Hz, 1H), 3.76 (s, 3H), 2.39 (q, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H), 1.06 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (126 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 172.9, 164.8, 145.0, 144.9, 139.3, 138.0, 52.1, 28.8, 9.2; HRMS (ESI) for C9H12N3O3 [M+H]+ calcd 210.0873, found 210.0876 (error 1.4 ppm).

4.1.40. Sodium 3-(propionamido)pyrazine-2-carboxylic acid (50).

The title compound was obtained from the 50a using the general method for ester hydrolysis in 38% yield as a white solid. Rf = 0.24 (9:1 CH2Cl2–MeOH); 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 13.71 (s, 1H), 8.26 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 1H), 8.16 (d, J = 2.5 Hz, 1H), 2.56 (q, J = 7.5 Hz, 2H), 1.09 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (151MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 172.2, 166.4, 149.0, 142.0, 142.0, 138.0, 136.9, 30.9, 9.19; HRMS (ESI) calcd for C8H8N3O3 [M-H]− 194.0571, found 194.0579 (error 4.1 ppm); Mp decomp. 260 °C; HPLC purity: 98%, tR = 7.1 min, k′ = 3.1.

4.1.41. 5-(Propionamido)pyrazine-2-carboxylic acid (51).

The title compound was obtained from the 5-aminopyrazine-2-carboxylic acid using general procedure of amidation with free acid in 81% yield as a white solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD) δ 9.49 (d, J = 1.1 Hz, 1H), 8.97(d, J = 1.1Hz, 1H), 2.52 (q, J = 7.5 Hz, 2H), 1.21 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, CD3OD) δ 175.8, 166.5, 152.5, 146.0, 139.2, 136.5, 30.8, 9.5; HRMS (ESI) calcd for C8H10N3O3 [M+H]+ 196.0717, found 196.0728 (error 5.6 ppm); Mp decomp. 191–193 °C; HPLC purity: 96%, tR = 7.0 min, k′ = 2.9.

4.1.42. 6-(Propionamido)pyrazine-2-carboxylic acid (52).

The title compound was obtained from the 6-aminopyrazine-2-carboxylic acid using general procedure of amidation with free acid in 87% yield as a white solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 11.1 (s, 1H), 9.49 (s, 1H), 8.83 (s, 1H), 2.44 (q, J = 7.5 Hz, 2H), 1.05 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 173.6, 165.0, 148.4, 141.4, 139.7, 139.1, 29.0, 9.2 HRMS (ESI) calcd for C8H10N3O3 [M+H]+ 196.0717, found 196.0716 (error 0.5 ppm); Mp decomp. 218–221 °C; HPLC purity: 97%, tR = 12.9 min, k′ = 6.2

4.1.43. Methyl 3-(methylamino)pyrazine-2-carboxylate (53a).

The title compound was obtained from methyl 3-chloropyrazinoate and ethylamine using the general method for amination in 68% yield as a yellow solid. Rf = 0.25 (1:3 EtOAc–Hexanes); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.26 (d, J = 2.3 Hz, 1H), 7.93 (s, 1H), 7.87 (d, J = 2.3 Hz, 1H), 3.97 (s, 3H), 3.07 (d, J = 4.9 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 167.3, 155.4, 147.5, 131.2, 52.7, 35.6, 14.7; HRMS (ESI) calcd for C7H10N3O2[M+H]+ 168.0768, found 168.0762 (error 3.6 ppm).

4.1.44. Sodium 3-(methylamino)pyrazine-2-carboxylate (53).

The title compound was obtained from 53a using the general method for ester hydrolysis in 79% yield as a white solid. Rf = 0.27 (9:1 CH2Cl2–MeOH); 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 9.27 (s, 1H), 7.78 (s, 1H), 7.33 (s, 1H), 1.45 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (151 MHz, MeOD) δ 178.3, 171.0, 155.9, 143.5, 128.7, 22.4; HRMS (ESI) calcd for C6H6N3O2Na2 [M+2Na]+ 198.0255, found 198.0266 (error 5.6 ppm). Mp decomp. > 280 °C; HPLC purity: 96%, tR = 5.9 min, k′ = 2.3.

4.1.45. Methyl 3-(propylamino)pyrazine-2-carboxylate (54a).

The title compound was obtained from methyl 3-chloropyrazinoate and propylamine using the general method for amination in 59% yield as a yellow solid. Rf = 0.38 (1:3 EtOAc–Hexanes); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.22 (d, J = 2.3 Hz, 1H), 8.01 (s, 1H), 7.85 (d, J = 2.2 Hz, 1H), 3.97 (s, 3H), 3.47 (td, J = 7.1, 5.5 Hz, 2H), 1.67 (p, J = 7.3 Hz, 2H), 1.00 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 167.3, 155.4, 147.2, 131.1, 124.2, 77.2, 52.7, 42.5, 22.5, 11.5; HRMS (ESI) calcd for C9H14N3O2[M+H]+ 196.1081, found 196.1069 (error 6.1 ppm).

4.1.46. Sodium 3-(propylamino)pyrazine-2-carboxylate (54).

The title compound was obtained from 54a using the general method for ester hydrolysis in 81% yield as a white solid. Rf = 0.39 (9:1 CH2Cl2–MeOH); 1H NMR (400 MHz, D2O) δ 7.99 (d, J = 2.6 Hz, 1H), 7.68 (d, J = 2.6 Hz, 1H), 3.43 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 2H), 1.65 (dd, J = 8.5, 6.4 Hz, 2H), 1.55–1.46 (m, 2H), 0.99 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, D2O) δ 177.7, 154.4, 149.8, 143.6, 129.4, 42.3, 21.6, 10.7; HRMS (ESI) calcd for C8H10N3O2Na2 [M+2Na]+ 226.0568, found: 226.0552 (error 7.1 ppm); Mp decomp. > 280 °C;HPLC purity: 98% tR = 9.4 min, k′ = 4.3.

4.1.47. Methyl 3-(2-propylamino)pyrazine-2-carboxylate (55a).

The title compound was obtained from methyl 3-chloropyrazinoate and isopropylamine using the general method for amination in 68% yield as a yellow solid. Rf = 0.43 (1:3 EtOAc–Hexanes); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.22 (d, J = 3.6 Hz, 1H), 7.84 (d, J = 3.6 Hz, 1H), 4.37– 4.22 (m, 1H), 3.96 (s, 3H), 1.28 (d, J = 6.5 Hz, 6H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 167.3, 154.7, 147.4, 131.0, 123.9, 52.6, 42.2, 22.7; HRMS (ESI) calcd for C9H14N3O2[M+H]+ 196.1081, found 196.1070 (error 5.6 ppm).

4.1.48. Sodium 3-(2-propylamino)pyrazine-2-carboxylate (55).

The title compound was obtained from 55a using the general method for ester hydrolysis in 72% yield as a white solid. Rf = 0.48 (9:1 CH2Cl2–MeOH); 1H NMR (400 MHz, D2O) δ 7.88 (s, 1H), 7.59 (s, 1H), 3.86 (p, J = 6.4 Hz, 1H), 1.09 (d, J = 6.4 Hz, 6H); 13C NMR (151 MHz, CD3OD) δ 178.4, 171.1, 154.6, 143.5, 128.8, 41.5, 21.6; HRMS (ESI) calcd for C8H10N3O2Na2 [M+2Na]+ 226.0568, found 226.0552 (error 7.0 ppm); Mp decomp. 200–205 °C; HPLC purity: 98% tR = 9.3 min, k′ = 4.2.

4.1.49. Methyl 3-(tert-butylamino)pyrazine-2-carboxylate (56a).

The title compound was obtained from methyl 3-chloropyrazinoate and tert-butylamine using the general method for amination in 45% yield as a white solid. Rf = 0.35 (1:3 EtOAc–Hexanes); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.19 (d, J = 1.2 Hz, 1H), 8.10 (s, 1H), 7.82 (d, J = 1.2 Hz, 1H), 3.95 (s, 3H), 1.49 (s, 9H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 167.6, 155.4, 146.7, 130.8, 52.6, 51.7, 28.8; HRMS (ESI) calcd for C10H16N3O2[M+H]+ 210.1237, found 210.1228 (error 4.3 ppm).

4.1.50. Sodium 3-(tert-butylamino)pyrazine-2-carboxylate (56).

The title compound was obtained from 56a using the general method for ester hydrolysis in 65% yield as a white solid. Rf = 0.23 (9:1 CH2Cl2–MeOH); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD) δ 8.00 (s, 1H), 7.63 (s, 1H), 1.44 (s, 9H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, CD3OD) δ 171.4, 155.5, 143.6, 141.6, 128.6, 50.3, 27.8; HRMS (ESI) calcd for C9H13N3O2Na2 [M+2Na]+ 240.0719, found 240.0728 (error 3.7 ppm); Mp decomp. > 280 °C; HPLC purity: 98%, tR = 11.2 min, k′ = 6.9.

4.1.51. Methyl 3-(n-butylamino)pyrazine-2-carboxylate (57a).

The title compound was obtained from methyl 3-chloropyrazinoate and n-butylamine using the general method for amination in 55% yield as a white solid. Rf = 0.6 (1:1 EtOAc–Hexanes); 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.16 (d, J = 2.2 Hz, 1H), 7.92 (s, 1H), 7.79 (d, J = 2.3 Hz, 1H), 3.91 (s, 3H), 3.44 (td, J = 7.1, 5.4 Hz, 2H), 1.61–1.55 (m, 2H), 1.38 (dt, J = 15.0, 7.4 Hz, 2H), 0.90 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (151 MHz, CDCl3) δ 167.4, 155.6, 147.5, 131.1, 124.1, 52.71, 40.5, 31.4, 20.2, 13.8; HRMS (ESI) calcd for C10H16N3O2[M+H]+ 210.1237, found 210.1227 (error 4.8 ppm).

4.1.52. Sodium 3-(n-butylamino)pyrazine-2-carboxylate (57).

The title compound was obtained from 57a using the general method for ester hydrolysis in 76% yield as a white solid. Rf = 0.53 (9:1 CH2Cl2–MeOH); 1H NMR (600 MHz, CD3ODD) δ 7.99 (d, J = 2.6 Hz, 1H), 7.68 (d, J = 2.6 Hz, 1H), 3.43 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 2H), 1.65 (dd, J = 8.5, 6.4 Hz, 2H), 1.55–1.46 (m, 2H), 0.99 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, CD3OD) δ 173.8, 160.6, 148.2, 139.6, 134.0, 44.6, 36.3, 25.0, 18.9; HRMS (ESI) calcd for C9H13N3O2Na2 [M+2Na]+ 240.0719, found 240.0727 (error 3.4 ppm); Mp decomp. 268–272 °C; HPLC purity: 99%, tR = 12.2 min, k′ = 2.7.

4.1.53. Methyl 3-(diethylamino)pyrazine-2-carboxylate (58a).

The title compound was obtained from methyl 3-chloropyrazinoate and diethylamine using the general method for amination in 59% yield as a yellow oil. Rf = 0.70 (3:1 EtOAc–Hexanes); 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.11 (d, J = 2.1 Hz, 1H), 7.85 (d, J = 2.2 Hz, 1H), 3.95 (s, 3H), 3.45 (q, J = 7.1 Hz, 4H), 1.19 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 6H); 13C NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3) δ 167.2, 153.2, 143.2, 131.2, 130.1, 52.9, 43.9, 12.6; HRMS (ESI) calcd for C10H16N3O2 [M+H]+ 210.1237, found210.1257 (error 9.5 ppm).

4.1.54. Sodium 3-(diethylamino)pyrazine-2-carboxylate (58).

The title compound was obtained from 58a using the general method for ester hydrolysis in quantitative yield as a yellow solid. Rf = 0.41 (9:1 CH2Cl2–MeOH); 1H NMR (500 MHz, CD3OD) δ 7.95 (d, J = 2.6 Hz, 1H), 7.58 (d, J = 2.6 Hz, 1H), 3.58 (q, J = 7.0 Hz, 4H), 1.20 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 6H); 13C NMR (126MHz, CD3OD) δ 175.4, 152.6, 142.9, 141.3, 130.1, 44.3, 13.2; HRMS (ESI) calcd for C9H12N3O2 [M-H]− 194.0935, found 194.0945 (error 5.2 ppm); Mp decomp.240–242 °C; HPLC purity: 96%, tR = 4.8 min, k′ = 1.7.

4.1.55. Methyl 3-(anilino)pyrazine-2-carboxylate (59a).

The title compound was obtained from methyl 3-chloropyrazinoate and aniline using the general method for amination in 86% yield as a yellow solid. Rf = 0.53 (1:1 EtOAc–Hexanes); 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 10.08 (s, 1H),8.27 (d, J = 3.6 Hz, 1H), 8.00 (d, J = 3.5 Hz, 1H), 7.58 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 2H), 7.36–7.27 (m, 2H), 7.05 (t, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 3.98 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (151 MHz, CDCl3) δ 167.3, 153.2, 146.8, 138.5, 133.5, 129.0, 125.0, 123.9, 121.3, 53.2; HRMS (EI) calcd for C12H11N3O2[M]+ 229.0846, found 229.0826 (error 8.8 ppm).

4.1.56. Sodium 3-(anilino)pyrazine-2-carboxylate (59).

The title compound was obtained from 59a using the general method for ester hydrolysis in 69% yield as a yellow solid. Rf = 0.64 (9:1 CH2Cl2–MeOH); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD) δ 8.04 (d, J = 2.5 Hz, 1H), 7.80 (d, J = 2.6 Hz, 1H), 7.60 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H), 7.21–7.16 (m, 2H), 6.88 (td, J = 7.4, 1.2 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, CD3OD) δ 119.29, 121.6, 128.4, 131.8, 140.0, 142.8, 152.7; HRMS (ESI) calcd for C11H9N3O2Na2 [M+2Na]+ 260.0406, found 260.0404 (error 0.2 ppm); Mp decomp.>280 °C; HPLC purity: 98%, tR = 8.6 min, k′ = 1.6.

4.1.57. Methyl 3-(benzylamino)pyrazine-2-carboxylate (60a).

The title compound was obtained from methyl 3-chloropyrazinoate and benzylamine using the general method for amination in 86% yield as an off-white solid. Rf = 0.51 (1:1 EtOAc–Hexanes); 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.37 (s, 1H),8.28 (d, J = 2.8 Hz, 1H), 7.94 (d, J = 2.9 Hz, 1H), 7.40–7.30 (m, 5H), 4.77 (s, 2H), 4.00 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (151 MHz, CDCl3) δ 167.3, 155.3, 147.5, 138.6, 131.8, 128.7, 127.5, 124.4, 52.8, 44.6; HRMS (EI) calcd for C13H13N3O2 [M]+ 243.1002, found 243.0990 (error 4.9 ppm).

4.1.58. Sodium 3-(benzylamino)pyrazine-2-carboxylate (60).

The title compound was obtained from 60a using the general method for ester hydrolysis in 74% yield as a white solid. Rf = 0.66 (9:1 CH2Cl2–MeOH); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD) δ 7.89 (d, J = 2.6 Hz, 1H), 7.62 (d, J = 2.6 Hz, 1H), 7.26 (d, J = 7.1 Hz, 2H), 7.22–7.18 (m, 2H), 7.15–7.10 (m, 1H), 4.54 (s, 2H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, CD3OD) δ 171.0, 155.0, 143.2, 139. 5, 129.7, 128.1, 127.0, 126.5, 43.9; HRMS (ESI) calcd for C12H11N3O2Na2 [M+2Na]+ 274.0563, found: 274.0564 (error 0.1 ppm); Mp decomp.>280 °C; HPLC purity: 99%, tR = 8.6 min, k′ = 1.6.

4.1.59. Methyl 3-(cyclopentylamino)pyrazine-2-carboxylate (61a).

The title compound was obtained from methyl 3-chloropyrazinoate and cyclopentylamine using the general method for amination in 96% yield as a yellow oil. Rf = 0.60 (1:1 EtOAc–Hexanes); 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.16 (d, J = 2.1 Hz, 1H), 7.94 (s, 1H), 7.78 (d, J = 2.0 Hz, 1H), 4.33 (h, J = 6.7 Hz, 1H), 3.90 (d, J = 1.3 Hz, 3H), 2.01 (dq, J = 12.7, 6.6 Hz, 2H), 1.77–1.65 (m, 2H), 1.65–1.52 (m, 2H), 1.46 (dq, J = 14.0, 7.6, 7.1 Hz, 2H); 13C NMR (151 MHz, CDCl3) δ 167.4, 155.1, 147.5, 131.1, 124.0, 52.7, 52.3, 33.2, 23.8; HRMS (EI) calcd for C11H15N3O2 [M]+ 221.1159, found: 221.1148 (error 5.0 ppm).

4.1.60. Sodium 3-(cyclopentylamino)pyrazine-2-carboxylate (61).

The title compound was obtained from 61a using the general method for ester hydrolysis in 78% yield as an off-white solid. Rf = 0.60 (9:1 CH2Cl2–MeOH); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD) δ 8.16 (d, J = 2.2 Hz, 1H), 7.67 (d, J = 2.2 Hz, 1H), 4.27 (q, J = 6.5 Hz, 1H), 1.97 (dq, J = 12.9, 6.8 Hz, 2H), 1.71–1.62 (m, 2H), 1.58 (qd, J = 9.5, 7.7, 5.2 Hz, 2H), 1.47–1.36 (m, 2H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, CD3OD) δ 168.1, 155.0, 147.6, 129.9, 123.9, 52.0, 32.7, 23.3; HRMS (ESI) calcd for C10H13N3O2Na2 [M+2Na]+ 252.0719, found 252.0701 (error 6.9 ppm);Mp99–101 °C; HPLC purity: 99%, tR = 12.3 min, k′ = 2.8.

4.1.61. Methyl 3-(pyrrolidine-1-yl)pyrazine-2-carboxylate (62a).

The title compound was obtained from methyl 3-chloropyrazinoate and pyrrolidine using the general method for amination in 87% yield as an off-white solid. Rf = 0.49 (1:1 EtOAc–Hexanes); 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.10 (d, J = 1.7 Hz, 1H), 7.81 (d, J = 2.1 Hz, 1H), 3.91 (s, 3H), 3.38–3.32 (m, 4H), 1.93–1.87 (m, 4H); 13C NMR (151 MHz, CDCl3) δ 166.7, 151.4, 143.9, 130.7, 128.4, 52.8, 49.2, 25.5; HRMS (EI) calcd for C10H13N3O2[M]+ 207.1002, found 207.0990 (error 6.0 ppm).

4.1.62. Sodium 3-(pyrrolidine-1-yl)pyrazine-2-carboxylate (62).

The title compound was obtained from 62a using the general method for ester hydrolysis in 89% yield as a white solid. Rf = 0.09 (9:1 CH2Cl2–MeOH); 1H NMR (600 MHz, MeOD) δ 8.07 (d, J = 2.2 Hz, 1H), 7.69 (d, J = 2.2 Hz, 1H), 3.35 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, 4H), 1.91–1.82 (m, 4H); 13C NMR (151 MHz, MeOD) δ 167.9, 151.2, 143.7, 129.5, 129.2, 48.8, 25.0; HRMS (ESI) calcd for C9H11N3O2Na2 [M+2Na]+: 238.0563, found: 238.0558 (error 2.1 ppm). Mp122–124 °C. HPLC purity: 99%, tR = 9.2 min, k′ = 1.8.

4.1.63. Methyl 3-(piperidin-1-yl)pyrazine-2-carboxylate (63a).

The title compound was obtained from methyl 3-chloropyrazinoate and piperidine using the general method for amination in 89% yield as a yellow oil. Rf = 0.56 (1:1 EtOAc–Hexanes); 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.07 (d, J = 2.3 Hz, 1H), 7.85 (d, J = 2.3 Hz, 1H), 3.90 (s, 3H), 3.41 – 3.35 (m, 4H), 1.62 – 1.57 (m, 6H); 13C NMR (151 MHz, CDCl3) δ 166.6, 154.7, 143.4, 132.2, 130.4, 52.8, 49.2, 25.7, 24.3; HRMS (ESI) calcd for C11H16N3O2 (M+H)+ 222.1237, found: 222.1237 (error 0 ppm)

4.1.64. Sodium 3-(piperidin-1-yl)pyrazine-2-carboxylate (63).

The title compound was obtained from 63a using the general method for ester hydrolysis in 74% yield as a yellow solid. Rf = 0.31 (9:1 CH2Cl2–MeOH); 1H NMR (600 MHz, CD3OD) δ 8.10 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 1H), 7.78 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 1H), 3.37 (t, J = 5.0 Hz, 4H), 1.63–1.51 (m, 6H); 13C NMR (151 MHz, CD3OD) δ 173.6, 152.9, 143.0, 140.1, 130.4, 25.4, 24.3; HRMS (EI) calcd for C10H14N3O2[M+H]+ 208.1081, found 208.1075 (error 2.9 ppm); Mp 127–129 °C; HPLC purity: 97%, tR = 9.2 min, k′ = 1.8.

4.1.65. Methyl 3-(morpholino)pyrazine-2-carboxylate (64a).

The title compound was obtained from methyl 3-chloropyrazinoate and morpholine using the general method for amination in 77% yield as a light yellow solid. Rf = 0.36 (1:1 EtOAc–Hexanes); 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.13 (d, J = 2.3 Hz, 1H), 7.96 (d, J = 2.3 Hz, 1H), 3.91 (s, 3H), 3.81–3.71 (m, 3H), 3.53–3.38 (m, 3H); 13C NMR (151 MHz, CDCl3) δ 166.3, 154.6, 143.7, 133.5, 130.7, 66.7, 52.9, 48.5; HRMS (EI) calcd for C10H13N3O3 [M]+ 223.0951, found 223.0933 (error 8.1 ppm).

4.1.66. Sodium 3-(morpholino)pyrazine-2-carboxylate (64).