Abstract

Objective

In sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), multiple factors contribute to the considerable burden of mental health disorders among adolescents, highlighting the need for interventions that address underlying risks at multiple levels. We reviewed evidence of the effectiveness of community or family-level interventions, with and without individual level interventions, on mental health disorders among adolescents in SSA.

Design

Systematic review using the Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development and Evaluation approach.

Data sources

A systematic search was conducted on Cochrane Library, MEDLINE, EMBASE, PSYCINFO and Web of Science up to 31 March 2021.

Eligibility criteria

Studies were eligible for inclusion in the review if they were randomised controlled trials (RCTs) or controlled quasi-experimental studies conducted in sub-Saharan African countries and measured the effect of an intervention on common mental disorders in adolescents aged 10–24 years.

Data extraction and synthesis

We included studies that assessed the effect of interventions on depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder and substance abuse. Substance abuse was only considered if it was measured alongside mental health disorders. The findings were summarised using synthesis without meta-analysis, where studies were grouped according to the type of intervention (multi-level, community-level) and participants.

Results

Of 1197 studies that were identified, 30 studies (17 RCTs and 3 quasi-experimental studies) were included in the review of which 10 delivered multi-level interventions and 20 delivered community-level interventions. Synthesised findings suggest that multi-level interventions comprise economic empowerment, peer-support, cognitive behavioural therapy were effective in improving mental health among vulnerable adolescents. Majority of studies that delivered interventions to community groups reported significant positive changes in mental health outcomes.

Conclusions

The evidence from this review suggests that multi-level interventions can reduce mental health disorders in adolescents. Further research is needed to understand the reliability and sustainability of these promising interventions in different African contexts.

PROSPERO registration number

CRD42021258826.

Keywords: MENTAL HEALTH, PUBLIC HEALTH, Anxiety disorders, Depression & mood disorders, Substance misuse

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Study selection was done by two independent reviewers to ensure all relevant studies were included.

As we only searched published studies, we may have missed important evidence from unpublished literature.

The diversity in the characteristics of included studies limited our ability to meta-analyse the findings.

Introduction

Mental health disorders account for 16% of the global burden of disease and injury in young people.1 Common mental disorders such as depression and anxiety are among the leading causes of illness and disability in adolescents aged 10–24 years.1 2 Globally, an estimated 10% of adolescents have a mental disorder and majority of these cases are not diagnosed or treated, leading to high risk of long-term physical and mental health problems in later life.3 It is vital to intervene early, as half of mental disorders that are experienced during adulthood have their onset during adolescence.4 Additionally, mental disorders are associated with poor academic and work performance and risky behaviours during adolescence.5–7

In sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), adolescents are disproportionately exposed to traumatic life experiences such as violence, armed conflicts and natural disasters, leading to high post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) prevalence rates.8 9 They also face other multiple challenges, including HIV-AIDS, early pregnancy, substance abuse and poverty.10–13 All these factors can directly or indirectly contribute to the risk of mental health disorders. For example, mental disorders are common in both people living with HIV and those at high risk of HIV acquisition,14–16 and they can also increase the risk for HIV acquisition.17 18 Given the complexity of problems that adolescents face and dearth of resources for mental health in SSA, there is a critical need for combination interventions that will address the underlying risk factors at multiple socio-ecological levels to improve mental health.19 20

To date, there is limited evidence from SSA regarding interventions that promote mental health and prevent or treat mental disorders in adolescents.21 Previous reviews from low/middle-income countries (LMICs) tended to focus on interventions that intervene only at interpersonal (family) or community-level to improve mental health outcomes in adolescents, or among specific groups (eg, HIV positive adolescents).22 23 For example, Bhana and colleagues23 previous study reviewing interventions targeted to adolescents living with or affected by HIV in LMICs found family-based and economic strengthening interventions to be effective in improving mental health. Similarly, Barry and colleagues demonstrated that mental health interventions can be implemented effectively in school and community-based settings.22 Despite growing evidence on the effectiveness of combination interventions on health outcomes (eg, HIV and sexual health outcomes) among adolescents in SSA,24 little is known about how these interventions could improve mental health in adolescents. The aim of this review was therefore to assess the effect of combining community or family-level interventions with individual level interventions on mental disorders in adolescents living in SSA. We used a socio-ecological model for combining interventions which suggests that people’s behaviour is influenced by multiple factors operating at different levels of influence (eg, individual, interpersonal-level (family/community)).25 26 This approach has been used by few studies to deliver mental health interventions to people living with HIV.27 The objective of the review was:

To assess the effect of interventions that are delivered to either individuals, groups or both on mental disorders (depression, anxiety, PTSD and substance abuse) among adolescents in SSA.

Methods

The conduct of this study was informed by the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions and Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines.28

Search strategy and selection criteria

A systematic literature search was conducted on the following electronic databases: Cochrane Library, MEDLINE, EMBASE, PSYCINFO and Web of Science. The search was restricted to English language. A search strategy was developed and evaluated in MEDLINE and adapted for other databases. Cochrane and SIGN filters for RCT search were applied in Ovid databases.29 The results were not filtered by publication date. A detailed search strategy is shown in online supplemental S1 appendix. Other articles were searched by manually reviewing the references of the selected studies. The last search was completed on 31 March 2021. All retrieved articles were sent to EndNote which was also used to remove duplicates. The screening of articles and full-text review were conducted by two independent reviewers (NM and AMR), and disagreements were resolved through discussion. Studies were included in the review if they met the following criteria:

bmjopen-2022-066586supp001.pdf (5.5MB, pdf)

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) (individually or cluster randomised) and quasi-experimental studies (with control group) that were conducted in SSA.

Participants were adolescents aged between 10 and 24 years (age when the intervention was implemented). We used an expanded definition of adolescence based on the culturally and contextually influenced delays in the transition roles to adulthood in resource-limited settings.30 31 Studies with adults above 24 years were only considered if data was disaggregated by age group so that outcomes in those aged 10–24 could be extracted. Studies were excluded if they did not specify age range of participants or did not mention that participants were adolescents.

Measured depression, anxiety, PTSD and substance abuse using a validated screening tool. Substance abuse (alcohol or drug abuse) was only included if it was measured alongside common mental disorders or PTSD.

Studies that met the criteria were classified according to the type of intervention which they delivered as: (a) individual-level only; (b) community-level only (including family-based); or (c) multi-level. Interventions were defined according to whether they were delivered directly to individuals or groups, irrespective of level of randomisation (cluster or individual). We defined individual-level interventions as those delivered directly to individuals (eg, one-on-one counselling, drug therapy) to develop copying strategies, change attitudes and behaviour. Community-level interventions were defined as interventions delivered to groups of people, including families and communities. Multi-level interventions were defined as a combination of individual and community-level interventions; interventions that were delivered to groups but also included one-on-one counselling sessions were categorised as multi-level interventions.

Data extraction and management

For each study, we extracted data on methods, participants, interventions and outcomes (see online supplemental S1 and S2 tables). For studies with multiple reports, we selected the most complete report, preferably including both baseline and last follow-up/postintervention data. For studies with pilot and main study reports, we preferred main study reports. Mean differences and SEs were used to generate forest plots. For studies that did not report SEs, the CIs, F statistic and p value were used to calculate SEs.28 For studies that reported ORs or rate ratios, a natural logarithm of each estimate was calculated.

Assessment of risk of bias in the included studies

Studies were critically assessed for risk of bias using Cochrane Tools.32 33 Random sequence generation or allocation concealment (or bias due to confounding for non-RCTs), blinding of outcome assessment and incomplete outcome data were considered critical for assessing the quality of studies in this review. No studies could blind participants due to the nature of interventions and we therefore did not include this criterion. Other biases which may rise due to use of inappropriate statistical analyses were also considered for cluster randomised trials, cross-over and non-randomised trials. None of the studies were excluded based on their risk of bias.

Assessment of heterogeneity

Clinical heterogeneity was assessed by considering the type of participants, duration of intervention and intervention components as these factors are likely to influence the effect of intervention.34 Statistical heterogeneity was assessed using visual inspection of forest plots and subgroup analysis in RevMan V.5 software.35 χ2 tests for heterogeneity with 10% level of significance was used and the degree of heterogeneity was measured using I2 statistic with values above 50% indicating substantial heterogeneity.34 For outcomes with enough studies (minimum five studies per subgroup), subgroup analyses were conducted based on the type of participants and type of intervention.34

Data synthesis

As the interventions and participants in the included studies were too diverse to allow a quantitative synthesis of the study findings, synthesis without meta-analysis was used to summarise the results.36 For all studies, we used outcomes measured at the last follow-up or postintervention regardless of whether the study had multiple follow-up times. The findings were synthesised separately for studies that delivered multi-level intervention and community-level interventions. Within each group, studies were subdivided according to type of participants who participated in the studies.

Assessment of the certainty of the evidence

The certainty of the body of evidence for each outcome was assessed using Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development and Evaluation approach within each of the four domains (risk of bias, inconsistency, imprecision and indirectness). The inconsistency in the findings was measured by looking at the direction of the effect among studies which measured the same outcome. The imprecision was measured by looking at the number of participants within each study and studies with less than 100 participants were judged as having serious imprecision. Indirectness was measured by looking at whether the included studies addressed the research question for this review. The quality of evidence was downgraded to a lower level (starting from high to very low) if one of the domains raised serious concerns.

Patient and public involvement

Since this is a systematic review, it was not possible to involve patients or public in the design or conduct or reporting of our research.

Results

The search results are described in figure 1. A total of 1197 articles were identified through database search and hand searching. Of these, 122 articles were assessed for eligibility and 30 studies were included in the synthesis.37–66 The remaining 92 articles were excluded due to various reasons described in online supplemental S3 table. Most studies were RCTs, except for three which used controlled quasi-experimental designs.54 58 61 Fourteen studies were cluster-randomised trials including one cross-over trial.66 Most studies had two groups except for four studies37 44 51 58 which randomised participants into three groups (two intervention groups and one control). Study durations ranged from 1 week to 4 years and the length of the interventions ranged from 1 hour to 4 years.

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flow diagram. PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder; RCT, randomised controlled trial.

Intervention

Interventions were heterogeneous across the included studies. The included studies were categorised according to the type of intervention (multi-level, community-based or individual). Of 30 included studies, 10 studies delivered multi-level interventions and the remaining studies delivered only community-based interventions. None of the included studies reported only individual-level interventions. For multi-level interventions, studies were divided into following categories: HIV affected; orphaned or bereaved; and war-affected adolescents. The studies that delivered community-level interventions were grouped in a similar way using the following categories: vulnerable adolescents comprised orphans, adolescents with trauma experiences and from poor households, students and general population.

Multi-level interventions

The multi-level interventions included a combination of community-level and individual- level interventions (table 1, online supplemental S4 table). Two studies delivered trauma-focused cognitive and behavioural therapy (CBT) for groups which also included trauma narratives modules that were delivered to individuals.45 46 Three studies delivered economic empowerment interventions which were combined with antiretroviral therapy (ART) or counselling.37–39 One study delivered HIV status disclosure to groups, and ART and counselling to individuals.40 One study delivered CBT and interpersonal therapy (IPT) intervention for groups (families) which included trauma narratives sessions for individuals.41 Participants in this study were all required to take ART. Two studies delivered a writing therapy or IPT in combination with counselling.43 44 One study delivered a peer-support intervention to participants who also had access to monthly healthcare.42 Most interventions targeted multiple mental health outcomes including those that are not common mental disorders (eg, self-concept, hopelessness, self-efficacy, grief, etc) and three studies targeted physical and sexual health in addition to mental health37 40 41 (online supplemental S5 table).

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies that delivered multi-level and community-level interventions

| Study (author) and setting | Target population | Study design, sample size | Study and intervention duration | Intervention components |

| Multi-level | ||||

| HIV/AIDS-affected adolescents | ||||

| Ssewamala et al, Uganda37 | Adolescents, AIDS orphans in fifth or sixth grade (average age=12) | RCT (cluster) N=1383 |

48 months. The intervention was provided for the first 24 months. Twelve 1–2 hour workshops | Group: economic empowerment Individual: counselling |

| Cavazos-Rehg et al, Uganda38 | Adolescents living with HIV, 10–16 years | RCT (cluster) N=702 | 48 months: The intervention was received for the first 24 months. 4 sessions and additional 12 sessions with a mentor for 24 months | Group (family): economic empowerment Individual: ART, weekly-monthly healthcare |

| Han et al, Uganda39 | AIDS orphaned adolescents, 10–14 years | RCT (cluster) N=297 | 12 months, 1–2 hours training sessions and one mentorship meeting per month over 12-month period | Group: economic empowerment Individual: counselling |

| Vreeman et al, Kenya40 | Adolescents HIV-infected and in active care, 10–14 years | RCT (cluster) N=285 | 24 months | Group: HIV status disclosure (counselling) Individual: ART, counselling |

| Dow et al, Tanzania41 | Young people living with HIV, 12–24 years | Pilot RCT (individual) N=105 | 6 months. Ten group sessions, two one-on-one sessions. 90 min every Saturday for 3 months | Group: cognitive and behavioural therapy (CBT), interpersonal therapy (IPT), motivational interviewing (MI) Individual: trauma narratives, ART |

| Kumakech et al, Uganda42 | Adolescents AIDS orphans, 10–15 years | RCT (cluster) N=326 | 16 exercises over 10 weeks. 1-hour play | Group: peer-group support Individual: monthly healthcare |

| Orphaned adolescents | ||||

| Thurman et al, South Africa43 | Bereaved female adolescents, 13–17 years | RCT (individual) N=382 | 8 sessions. Weekly 90 min sessions (average three activities) | Group: theory-based support group (IPT), cultural adaptation Individual: counselling |

| Unterhitzenberger and Rosner, Rwanda44 | Orphaned adolescents, 14–18 years | RCT (individual) N=69 | 3 weeks. 30 min writing periods each week on three consecutive Thursdays | Group: writing therapy Individual: counselling |

| War-affected adolescents | ||||

| O'Callaghan et al, Democratic Republic of Congo45 | Sexually exploited, war-affected adolescent girls aged 12–17 years | RCT (individual) N=52 | 3 months. The intervention was offered for 2 hours per day, 3 days per week for 5 weeks | Group: CBT Individual: trauma narratives |

| McMullen et al, Democratic Republic of Congo46 | Adolescent boys-former child soldiers aged 13–17 years | RCT (individual) N=50 | 3 months. 15 sessions. The intervention was delivered for approximately 5 weeks | Group: trauma Focused-CBT Individual: trauma narratives |

| Community_level | ||||

| Vulnerable adolescents | ||||

| Green et al, Kenya47 | Orphaned adolescents (average age 14 years) | RCT (cluster) N=835 | 4 years. The intervention was provided annually from 2011 until 2015, or until the student dropped out of school | Cash transfers (school support) |

| Ismayilova et al, Burkina Faso48 | Children aged 10–15 years from extremely poor households | RCT (cluster) N=360 | 24 months. Monthly one-on-one mentoring over 24 months. Family sessions conducted once monthly (35–45 min each) |

Economic strengthening, family coaching |

| Cluver et al, South Africa49 | Adolescents aged 10–18 years and their caregivers from families reporting conflict with their adolescents | Pragmatic RCT (cluster) N=552 | 9 months. 10 weekly child-caregiver sessions four separately | Parenting programme |

| Rossouw et al (2018), South Africa50 | Adolescents who had experienced or witnessed an interpersonal trauma and had chronic PTSD (>3 months), 13–18 years | RCT (individual) N=63 | 6 months. 7–14 weekly, 60 min sessions | Prolonged exposure therapy, control group received supportive counselling |

| Betancourt et al, Uganda51 | Adolescent war-survivors, 14–17 years | RCT (individual) N=314 | 1 year. 16 weekly group meetings, lasting 1.5–2 hours each | Group interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT) and creative play |

| Getanda and Vostanis, Kenya52 | Adolescents aged 14–17 years and experienced traumatic events in the past year | RCT (individual) N=54 | 1 week. Six sessions of writing over three consecutive days | Writing for recovery-psycho-social-educational group intervention |

| Thurman et al, South Africa53 | Orphaned and vulnerable adolescents, 14–17 years | RCT (cluster) N=489 | 2 years. 16 weekly 90 min group sessions | Interpersonal psychotherapy for groups (IPTG) |

| School/college-based adolescents | ||||

| McMullen and McMullen, Uganda54 | Adolescent students, 13–18 years | Quasi-controlled (cluster) N=620 | 1 year. 24 sessions, 45–60 min each | The Living Well manualised intervention (based on CBT) |

| Rivet-Duval et al, Mauritius55 | Adolescents from single-sex secondary schools, 12–16 years | RCT (individual). N=160 | 6 months. 11 1 hour weekly sessions | The Resourceful Adolescent Programme based on CBT and IPT |

| Ede et al, Nigeria56 | College adolescents, 16–21 years | RCT (individual) N=162 | 12 sessions (one session per week) lasted for 1 hour each. | Group cognitive behavioural therapy |

| Richards et al, Uganda57 | Adolescent primary school pupils aged 11–14 years | RCT (individual) N=1462 | 11 weeks. At least one 1.5-hour training session per week over 9 weeks. 40 min game each weekend | The sport-for-development intervention |

| Eifediyi et al, Nigeria58 | Secondary school students, 14–19 years | Quasi-experimental controlled N=160 | 7 weeks. 45 min each of six sessions lasted for 7 weeks | Rational emotive behaviour therapy |

| Osborn et al, Kenya59 | Adolescent students, 14–17 years | RCT (individual) N=51 | 4 weeks. Four 1-hour sessions that were 1 week apart included homework exercises | Wise intervention |

| Berger et al, Tanzania60 | Primary school students, aged 11–14 years in grades 6–8 | RCT (cluster) N=183 | 16 sessions=two weekly 45 min sessions | Stress-Prosocial programme (ESPS) |

| Jordans et al, Burundi61 | School-going children aged 10–14 years with elevated psychological distress | Quasi-experimental with controls N=161 | Two sessions of an average 2.5 and 3.0 hours, respectively | Brief parenting psychoeducation |

| Osborn et al, Kenya62 | Adolescent high school students aged 14–17 years | RCT (individual) N=103 | The intervention took 1 hour | Digital wise intervention |

| Bella‐Awusah et al, Nigeria63 | Adolescents with depressive symptoms and aged 14–17 years | RCT (cluster) N=40 | Five structured sessions offered weekly, each lasting 45–60 min | Brief school-based, group cognitive behavioural therapy |

| General population | ||||

| Kilburn et al, Kenya64 | Adolescents, 15–24 years | RCT (cluster) N=1960 | 4 years | Large-scale unconditional cash transfer |

| Angeles et al, Malawi65 | Adolescents, 13–19 years | RCT (cluster) N=2099 | 2 years. Monthly cash transfers for 2 years | Social Cash Transfer Programme |

| Puffer et al, Kenya66 | Adolescents (and caregivers) aged 10–16 years | RCT (cluster) stepped wedge (four churches, n=237) | 3 months. Nine sessions (2-hour each) | Parenting programme, HIV prevention, CBT, economic empowerment |

ART, antiretroviral therapy; N, sample size; RCT, randomised controlled trial.

Community-level interventions

Twenty studies delivered community-level interventions including CBT, IPT, writing for recovery, wise interventions (group and single digital session), psychoeducation (including parenting), prolonged exposure therapy, economic empowerment, cash transfers, parenting programme and sport for development (table 1). Five studies delivered economic empowerment interventions,47 48 64–66 of which two delivered economic empowerment alongside family coaching or parenting programme.48 66 Five studies delivered CBT including CBT-based interventions50 54 56 58 63 such as prolonged exposure therapy,50 rational emotive behaviour therapy58 and The Living Well intervention.55 Prolonged exposure therapy helps individuals to gradually confront their fears. Rational emotive behaviour therapy involves identifying and altering negative thoughts and beliefs that lead to unhealthy behaviour. The Living Well programme teaches about different behaviour change techniques such as problem solving, monitoring of emotional consequences and self-talk. Two studies delivered IPT51 53 and one study delivered The Resourceful Adolescent Programme which used both CBT and IPT techniques.54 Two studies delivered group and digital wise interventions that focus on how people make sense of themselves, the people or situations they are in.59 62 Ten studies delivered community-level interventions that targeted multiple outcomes and two of these studies did not target mental health as primary outcomes.49 66

Implementation of interventions

The follow-up periods of the studies varied by type of intervention (online supplemental S4 table). Studies that delivered economic empowerment or HIV disclosure interventions had longer follow-up time ranging between 12 and 48 months. The retention rates at follow-up were high (above 80%) for both multi-level and community-level interventions, except two studies that reported attrition rates of 23% and 37%53 65 and one study that did not report retention rate.38 Interventions in most studies were delivered by non-specialists (lay community health workers, teachers) who were trained and supervised by mental health specialists (see online supplemental S5 table).

Participants

The participants in the included studies varied across studies. Among studies that delivered multi-level interventions, six studies included participants who were living with HIV or affected by HIV,37–41 two studies included war-affected adolescents43 44 and two included orphans and bereaved female adolescents.45 46

Of 20 studies that delivered community-based interventions, 10 included school-going or college adolescents,54–63 seven studies included vulnerable populations such as orphans, war survivors, adolescents who have experienced trauma and vulnerable orphans (from poor households)47–53 and three studies included general population.64–66

Risk of bias in the included studies

All included studies were assessed for risk of bias. Ten studies were rated as having an overall high risk of bias due to not blinding the outcome assessors, incomplete outcome data and use of inappropriate statistical methods (eg, not accounting for clustering),40 42 44 54 55 58 61 63 64 66 while 11 studies were judged as having an overall low risk of bias.41 43 46–51 53 56 The remaining nine studies were judged as having unclear risk of bias. The summary of risk of bias is shown in online supplemental S6 table.

Effect of multi-level interventions on mental health

Depression

Eight studies measured depression (figure 2).37–44 Three studies found a significant decrease in depressive symptoms among participants in the intervention group compared with control group.39 42 43 Of these studies, two delivered peer or theory-based support to AIDS orphans42 or bereaved females,43 and one study delivered economic empowerment intervention.39 In four studies, multi-level intervention was not significantly associated with decrease in depressive symptoms. However, one study that delivered a family economic empowerment intervention found a significant decrease in depressive symptoms at 24-month follow-up (end of intervention) but no significant effect observed thereafter at 36 and 48 months.37 One study by Unterhitzenberger and Rosner evaluated the effect of emotional writing on depression and found that emotional writing was associated with increased depression symptoms compared with positive writing and no writing.44

Figure 2.

Effect of multi-level interventions on depression, anxiety and PTSD. ART, antiretroviral therapy; CBT, cognitive and behavioural therapy; IPT, interpersonal therapy; MI, motivational interviewing; PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder; RCT, randomised controlled trial.

Anxiety

There was only one study that measured anxiety. Kumakech and colleagues found a significant decrease in anxiety among adolescents who received a peer support and monthly care compared with those who in the control group.42

Post-traumatic stress disorders

Three studies measured PTSD.41 45 46 Of these studies, two showed a significant decrease in PTSD symptoms among participants in the intervention group compared with participants in the control group.45 46 Both studies delivered CBT to war-affected adolescents.

Depression and anxiety-like symptoms

There were two studies45 46 that looked at depression and anxiety-like symptoms (see online supplemental S1 figure). Both studies delivered CBT and found a significant decrease in depression and anxiety-like symptoms among participants in the intervention group compared with control group.

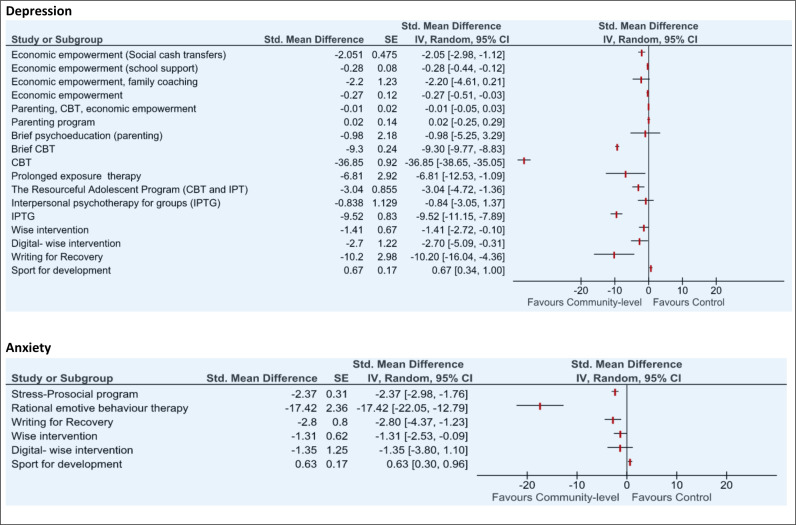

Effect of community-level interventions on mental health

Depression

Seventeen studies measured depression (figure 3). As there were enough studies that measured depression, subgroup analyses (by intervention and participants) were conducted to assess heterogeneity among studies (see online supplemental S2 and S3 figures). There was substantial unexplained heterogeneity (I2>90%) between all studies and within each of the subgroups. Therefore, the intervention effect estimate was not calculated.

Figure 3.

Effect of community-level interventions on depression and anxiety. CBT, cognitive and behavioural therapy; IPT, interpersonal therapy.

Eleven studies showed a significant decrease in depressive symptoms among participants in the intervention group in comparison with the control group. Of the 11 studies, five delivered theory-based interventions (CBT, IPT and wise interventions) to school or college students55–57 62 63 and two delivered economic empowerment intervention to general adolescents.64 65 The remaining four studies delivered interventions to vulnerable adolescents: three delivered theory-based interventions to adolescents who had trauma experiences,50–52 and one delivered economic empowerment (cash transfers) to orphans.47

Four studies did not show any significant effect of intervention on depressive symptoms.48 49 54 61 One study that used sport to promote physical fitness and mental well-being showed a significant increase in depressive symptoms among adolescent boys who participated in the sport-for-development interventions compared with control group.57

Anxiety

There were six studies that looked at anxiety (figure 3). Four studies found a significant decrease in anxiety symptoms among participants in the intervention group compared with control group and all these studies were conducted in schools.52 57–60 Richards and colleagues57 evaluated the effect of sport-for-development intervention and found an increase in anxiety symptoms among participants in the intervention group compared with participants in the control group.

Post-traumatic stress disorder

Three studies measured PTSD (figure 4). Two studies that delivered prolonged exposure therapy and writing for recovery to adolescents with trauma experiences found a significant decrease in PTSD symptoms among participants in the intervention group.50 52 One study by Ismayilova and colleagues delivered economic strengthening intervention but found no significant effect of the intervention on PTSD.48

Figure 4.

Effect of community-level interventions on post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and substance abuse.

Substance abuse

One study that looked at substance abuse alongside mental disorders found a significant decrease in substance abuse among participants in the intervention group compared with control group.49 The study delivered a parenting programme (figure 4).

Depression and anxiety-like symptoms

There was only one study that assessed depression and anxiety-like symptoms54 (see online supplemental S4 figure). This study found a significant decrease in depression and anxiety-like symptoms among participants in the intervention group compared with participants in the control group.

Certainty of evidence

The main strength of this review is that it is the first to assess the effect of multi-level interventions on mental health in adolescents in SSA. However, it is important to note the quality of evidence when interpreting these findings. Full details on quality appraisal are provided in online supplemental S7 table.

Multi-level interventions

The quality of evidence for studies that delivered multi-level interventions ranged from low to moderate. The results for effect of multi-level interventions on depression were not consistent across eight studies. Anxiety was measured by only one study which had a high attrition rate in the control group and did not adjust for clustering of participants in the analysis.42 Among three studies that measured PTSD, two studies had small sample sizes below 100.45 46

Community-level interventions

The quality of evidence for studies that delivered community-level interventions ranged from low to high. For depression, most studies showed a positive intervention effect, however, the studies that delivered economic empowerment or parenting intervention seemed to have no or smaller effect than studies that delivered CBT or IPT interventions. The quality of evidence was not downgraded as the direction of effect was consistent for most studies. For anxiety, the quality of evidence was rated as high. For PTSD, the evidence was downgraded to moderate because two of the three studies that measured PTSD had sample sizes smaller than 100. For depression and anxiety-like symptoms (combined outcome), only one study was included. This study had a high risk of bias due to high attrition rate (only 27% completed both pre-questionnaire and post-questionnaire).54 Thus, the quality of evidence was downgraded to low. For substance abuse, only one study was included. The study included enough participants and had a low risk of bias. Thus, the quality of evidence was rated as high.

Discussion

The findings from this systematic review suggest that multi-level interventions that include economic empowerment, peer-support or CBT can improve mental health in adolescents. Similar patterns indicating the positive effect of these interventions were also observed for studies that delivered only community-level interventions. However, due to high variability in intervention components and study participants between studies identified in this review, further research on these interventions is needed to help us understand their effect when scaled up in different contexts and to demonstrate if they can be reliable and sustainable. The variability in intervention components found in this review is consistent with previous reviews that looked at mental health interventions for adolescents in LMICs.22 23 67

Among five studies that found multi-level interventions to be effective in reducing mental health problems, the intervention components included group-based economic empowerment, peer support, CBT and IPT. These group-based interventions were offered alongside counselling or healthcare or included one-on-one trauma narrative sessions. One study that delivered an economic empowerment intervention did not show significant intervention effect after the intervention had been stopped,37 and other two studies with longer duration (12 months or more) did not have an impact on depression.38 40 This suggests that some interventions may be effective but fail to show positive long-term impact on mental health. This also highlights the importance of investing in sustainable interventions that have a longer positive health impact.

Multi-level interventions were generally delivered to highly vulnerable populations such as adolescents infected with or affected by HIV, orphans and war-affected adolescents, with individual-level components offered based on individual’s need. While vulnerabilities may vary within youth populations, it is important to consider their individual needs when designing interventions. Engaging young people in the development of interventions may help identify their needs and ensure that interventions are relevant to their individual needs. Youth engagement have been found to be effective in improving mental health in youth,68 however it is still limited in SSA.69

Community-level interventions varied substantially. Sixteen of the twenty studies reviewed significantly reduced mental health problems including substance abuse. Of these studies, four delivered economic empowerment interventions and family coaching or parenting interventions. Economic empowerment interventions like cash transfers have been shown to have a positive impact on mental health outcomes in SSA.70 Parenting and family-focused interventions have been shown to have a significant positive effect on child and youth mental health in LMICs.23 71 Another eleven effective studies delivered theory-based interventions such as CBT and IPT, of which ten were conducted in schools. This suggests that schools provide a good opportunity for implementation of interventions that are relevant to adolescents and youth; a previous review has demonstrated that school-based mental health interventions can be effective in improving mental health and could be integrated into education programmes.22 Nevertheless, care must be taken not to exclude out-of-school youth by targeting effort too much on school settings. Peer-led community-based and digital mental health interventions including internet-based CBT may be able to reach many young people irrespective of whether they are enrolled in school.72 73

While there is overlap between mental health problems and substance abuse, in this review we identified only one study that measured both mental health and substance abuse. Cluver and colleagues found a significant positive effect of parenting programme on substance use among adolescents’ families reporting conflicts, but no observed effect on mental health.49 This finding highlights the importance of comprehensive interventions that involve parents, to prevent and reduce substance abuse in adolescents. In SSA, where substance abuse among adolescents is a major public health problem,12 there is need for further research to identify effective interventions that will simultaneously reduce substance abuse and mental health problems.

Most studies in this review were targeting adolescents who were already having symptoms of common mental disorders. This highlights the gap in the evidence of preventive interventions on mental health in SSA and suggests the need for universal mental health interventions (whole school or community) that can reduce the risks of poor mental health. In settings like SSA where it may not be affordable to treat mental health conditions, preventive interventions such as economic empowerment and family strengthening interventions that are already known to be effective may be vital to reducing social determinants of poor mental health in adolescents. Future research should identify strategies to implement preventive interventions and consider task-shifting delivery model to achieve sustainable long-term mental health gains.

This review has a number of limitations. First, we only searched published studies and included only RCTs or quasi-experimental (controlled) studies, therefore some evidence from unpublished and qualitative studies may have been excluded. Second, we were unable to report summary effect measures due to variability in intervention components, participants and study duration in the included studies. Third, majority of studies measured the outcomes using a continuous scale without a cut-off or further confirmation of diagnosis by the specialist. Fourth, none of the included studies looked at individual-level interventions, so we could not compare multi-level interventions with individual-level interventions. Finally, we restricted the search to studies that included adolescents aged 10–24 years, this might have excluded important information. Despite these limitations, this review adds new knowledge about mental health interventions for adolescents. Our findings highlight the need to combine individual-level and community or family-level interventions when addressing mental health problems in vulnerable youth population. For example, social support or social protection interventions such as cash transfers, parenting programmes and school-based interventions (including feeding scheme) may be delivered in combination with individual-level interventions tailored to young people’s needs.

Conclusion

There is evidence that multi-level interventions can improve mental health in young people in SSA. Economic empowerment, peer-support or CBT found to be effective when delivered alone or in combination with individual-level interventions tailored to individual needs. However, due to limited number of studies and substantial heterogeneity in intervention components, study participants and duration among studies that delivered multi-level interventions, it is difficult to identify intervention components that are most effective. Future research should involve replicating these promising interventions in different settings to understand their long-term effect and reliability under different circumstances.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Twitter: @harlingg, @MaryamShJ

Contributors: NM, MS, GH and AC conceptualised and designed the study. NM and AMR undertook the literature searches, independently screened, filtered and selected the articles. NM and AMR completed the full text reviewing of articles and compared the database for discrepancies. NM analysed data and drafted the manuscript. All authors contributed to interpreting the data. All authors critically reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript. The corresponding author affirms that all listed authors meet authorship criteria. NM is the guarantor.

Funding: MS is supported by the National Institute of Health (5R01MH114560-03). GH is supported by a fellowship from the Wellcome Trust and Royal Society [grant number 210479/Z/18/Z]. This research was funded in whole, or in part, by Wellcome [Grant number Wellcome Strategic Core award: 201433/Z/16/A]. For the purpose of open access, the author has applied a CC BY public copyright licence to any Author Accepted Manuscript version arising from this submission,

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information. The data supporting the findings of this study are provided in the supplemental material.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

References

- 1.GBD 2019 Diseases and Injuries Collaborators . Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2019. The Lancet 2020;396:1204–22. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30925-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eyre O, Thapar A. Common adolescent mental disorders: transition to adulthood. The Lancet 2014;383:1366–8. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62633-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.WHO . Adolescent mental health Geneva. 2020. Available: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/adolescent-mental-health [Accessed 11 Feb 2021].

- 4.Jones PB. Adult mental health disorders and their age at Onset. Br J Psychiatry 2013;202:s5–10. 10.1192/bjp.bp.112.119164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kusi-Mensah K, Donnir G, Wemakor S, et al. Prevalence and patterns of mental disorders among primary school age children in Ghana: correlates with academic achievement. J Child Adolesc Ment Health 2019;31:214–23. 10.2989/17280583.2019.1678477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Folayan MO, Arowolo O, Mapayi B, et al. Associations between mental health problems and risky oral and sexual behaviour in adolescents in a sub-urban community in Southwest Nigeria. BMC Oral Health 2021;21:401. 10.1186/s12903-021-01768-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maina BW, Orindi BO, Osindo J, et al. Depressive symptoms as predictors of sexual experiences among very young adolescent girls in slum communities in Nairobi, Kenya. Int J Adolesc Youth 2020;25:836–48. 10.1080/02673843.2020.1756861 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Koenen KC, Ratanatharathorn A, Ng L, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder in the world mental health surveys. Psychol Med 2017;47:2260–74. 10.1017/S0033291717000708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Charlson F, van Ommeren M, Flaxman A, et al. New WHO prevalence estimates of mental disorders in conflict settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 2019;394:240–8. 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30934-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.UNAIDS . Confronting inequalities. Lessons for pandemic responses from 40 years of AIDS. 2021. Available: https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/documents/2021/2021-global-aids-update?msclkid=e300ef16b9d911ec80981ac58dea961e [Accessed 2 Feb 2022].

- 11.Kassa GM, Arowojolu AO, Odukogbe AA, et al. Prevalence and determinants of adolescent pregnancy in Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Reprod Health 2018;15:195. 10.1186/s12978-018-0640-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Olawole-Isaac A, Ogundipe O, Amoo EO, et al. Substance use among adolescents in sub-Saharan Africa. A systematic review and meta-analysis. S Afr J CH 2018;12:79. 10.7196/SAJCH.2018.v12i2b.1524 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mbirimtengerenji ND. Is HIV/AIDS epidemic outcome of poverty in sub-Saharan Africa Croat Med J 2007;48:605–17. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Remien RH, Stirratt MJ, Nguyen N, et al. Mental health and HIV/AIDS: the need for an integrated response. AIDS 2019;33:1411–20. 10.1097/QAD.0000000000002227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lassi ZS, Salam RA, Bhutta ZA. Recommendations on arresting global health challenges facing adolescents and young adults. Ann Glob Health 2017;83:704–12. 10.1016/j.aogh.2017.10.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kinyanda E, Levin J, Nakasujja N, et al. Major depressive disorder: longitudinal analysis of impact on clinical and behavioral outcomes in Uganda. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2018;78:136–43. 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tlhajoane M, Eaton JW, Takaruza A, et al. Prevalence and associations of psychological distress, HIV infection and HIV care service utilization in East Zimbabwe. AIDS Behav 2018;22:1485–95. 10.1007/s10461-017-1705-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Peltzer K, Pengpid S, Tiembre I. Mental health, childhood abuse and HIV sexual risk behaviour among university students in Ivory Coast. Ann Gen Psychiatry 2013;12:18. 10.1186/1744-859X-12-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McLeroy KR, Bibeau D, Steckler A, et al. An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health Educ Q 1988;15:351–77. 10.1177/109019818801500401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Castillo EG, Ijadi-Maghsoodi R, Shadravan S, et al. Community interventions to promote mental health and social equity. Curr Psychiatry Rep 2019;21. 10.1007/s11920-019-1017-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Skeen S, Laurenzi CA, Gordon SL, et al. Adolescent mental health program components and behavior risk reduction: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics 2019;144:e20183488. 10.1542/peds.2018-3488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barry MM, Clarke AM, Jenkins R, et al. A systematic review of the effectiveness of mental health promotion interventions for young people in low and middle income countries. BMC Public Health 2013;13:835. 10.1186/1471-2458-13-835 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bhana A, Abas MA, Kelly J, et al. Mental health interventions for adolescents living with HIV or affected by HIV in low- and middle-income countries: systematic review. BJPsych Open 2020;6:e104. 10.1192/bjo.2020.67 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mebrahtu H, Skeen S, Rudgard WE, et al. Can a combination of interventions accelerate outcomes to deliver on the sustainable development goals for young children? Evidence from a longitudinal study in South Africa and Malawi. Child Care Health Dev 2022;48:474–85. 10.1111/cch.12948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weiner BJ, Lewis MA, Clauser SB, et al. In search of synergy: strategies for combining interventions at multiple levels. JNCI Monographs 2012;2012:34–41. 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgs001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schölmerich VLN, Kawachi I. Translating the socio-ecological perspective into multilevel interventions: gaps between theory and practice. Health Educ Behav 2016;43:17–20. 10.1177/1090198115605309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van Luenen S, Garnefski N, Spinhoven P, et al. The benefits of psychosocial interventions for mental health in people living with HIV: a systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS Behav 2018;22:9–42. 10.1007/s10461-017-1757-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, eds. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 6.2 (updated February 2021). Cochrane, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Glanville J, Kotas E, Featherstone R, et al. Which are the most sensitive search filters to identify randomized controlled trials in MEDLINE J Med Libr Assoc 2020;108:556–63. 10.5195/jmla.2020.912 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kinghorn A, Shanaube K, Toska E, et al. Defining adolescence: priorities from a global health perspective. The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health 2018;2:e10. 10.1016/S2352-4642(18)30096-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sawyer SM, Azzopardi PS, Wickremarathne D, et al. The age of adolescence. The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health 2018;2:223–8. 10.1016/S2352-4642(18)30022-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sterne JA, Hernán MA, Reeves BC, et al. ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ 2016:i4919. 10.1136/bmj.i4919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sterne JAC, Savović J, Page MJ, et al. Rob 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2019;366:l4898. 10.1136/bmj.l4898 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Deeks JJ, Higgins JPT. Chapter 10: analysing data and undertaking meta-analyses. In: Higgins JPT TJ, Chandler J, Cumpston M, et al., eds. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. 2nd Edition. Chichester (UK): John Wiley & Sons, 2019: 241–84. 10.1002/9781119536604 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.The Cochrane Collaboration . Review manager (Revman) [computer program]. version 5.4. 2020.

- 36.Campbell M, McKenzie JE, Sowden A, et al. Synthesis without meta-analysis (swim) in systematic reviews: reporting guideline. BMJ 2020;368:l6890. 10.1136/bmj.l6890 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ssewamala FM, Shu-Huah Wang J, Brathwaite R, et al. Impact of a family economic intervention (bridges) on health functioning of adolescents orphaned by HIV/AIDS: A 5-year (2012-2017) cluster randomized controlled trial in Uganda. Am J Public Health 2021;111:504–13. 10.2105/AJPH.2020.306044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cavazos-Rehg P, Byansi W, Xu C, et al. The impact of a family-based economic intervention on the mental health of HIV-infected adolescents in Uganda: results from Suubi + adherence. J Adolesc Health 2021;68:742–9. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.07.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Han C-K, Ssewamala FM, Wang JS-H. Family economic empowerment and mental health among AIDS-affected children living in AIDS-impacted communities: evidence from a randomised evaluation in southwestern Uganda. J Epidemiol Community Health 2013;67:225–30. 10.1136/jech-2012-201601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vreeman RC, Nyandiko WM, Marete I, et al. Evaluating a patient-centred intervention to increase disclosure and promote resilience for children living with HIV in Kenya. AIDS 2019;33 Suppl 1:S93–101. 10.1097/QAD.0000000000002183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dow DE, Mmbaga BT, Gallis JA, et al. A group-based mental health intervention for young people living with HIV in Tanzania: results of a pilot individually randomized group treatment trial. BMC Public Health 2020;20:1358. 10.1186/s12889-020-09380-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kumakech E, Cantor-Graae E, Maling S, et al. Peer-group support intervention improves the psychosocial well-being of AIDS orphans: cluster randomized trial. Social Science & Medicine 2009;68:1038–43. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.10.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thurman TR, Luckett BG, Nice J, et al. Effect of a bereavement support group on female adolescents' psychological health: a randomised controlled trial in South Africa. Lancet Glob Health 2017;5:e604–14. 10.1016/S2214-109X(17)30146-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Unterhitzenberger J, Rosner R. Lessons from writing sessions: a school-based randomized trial with adolescent orphans in Rwanda. Eur J Psychotraumatol 2014;5:24917. 10.3402/ejpt.v5.24917 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.O’Callaghan P, McMullen J, Shannon C, et al. A randomized controlled trial of trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy for sexually exploited, war-affected congolese girls. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 2013;52:359–69. 10.1016/j.jaac.2013.01.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McMullen J, O’Callaghan P, Shannon C, et al. Group trauma-focused cognitive-behavioural therapy with former child soldiers and other war-affected boys in the DR Congo: a randomised controlled trial. J Child Psychol Psychiatr 2013;54:1231–41. 10.1111/jcpp.12094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Green EP, Cho H, Gallis J, et al. The impact of school support on depression among adolescent orphans: a cluster-randomized trial in Kenya. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2019;60:54–62. 10.1111/jcpp.12955 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ismayilova L, Karimli L, Sanson J, et al. Improving mental health among ultra-poor children: two-year outcomes of a cluster-randomized trial in Burkina Faso. Social Science & Medicine 2018;208:180–9. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.04.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cluver LD, Meinck F, Steinert JI, et al. Parenting for lifelong health: a pragmatic cluster randomised controlled trial of a non-commercialised parenting programme for adolescents and their families in South Africa. BMJ Glob Health 2018;3:e000539. 10.1136/bmjgh-2017-000539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rossouw J, Yadin E, Alexander D, et al. Prolonged exposure therapy and supportive counselling for post-traumatic stress disorder in adolescents: task-shifting randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry 2018;213:587–94. 10.1192/bjp.2018.130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Betancourt TS, Newnham EA, Brennan RT, et al. Moderators of treatment effectiveness for war-affected youth with depression in northern Uganda. J Adolesc Health 2012;51:544–50. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.02.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Getanda EM, Vostanis P. Feasibility evaluation of psychosocial intervention for internally displaced youth in Kenya. Journal of Mental Health 2022;31:774–82. 10.1080/09638237.2020.1818702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Thurman TR, Nice J, Taylor TM, et al. Mitigating depression among orphaned and vulnerable adolescents: a randomized controlled trial of interpersonal psychotherapy for groups in South Africa. Child Adolesc Ment Health 2017;22:224–31. 10.1111/camh.12241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.McMullen JD, McMullen N. Evaluation of a teacher-led, life-skills intervention for secondary school students in Uganda. Social Science & Medicine 2018;217:10–7. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.09.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rivet-Duval E, Heriot S, Hunt C. Preventing adolescent depression in Mauritius: a universal school-based program. Child Adolesc Ment Health 2011;16:86–91. 10.1111/j.1475-3588.2010.00584.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ede MO, Igbo JN, Eseadi C, et al. Effect of group cognitive behavioural therapy on depressive symptoms in a sample of college adolescents in Nigeria. J Rat-Emo Cognitive-Behav Ther 2020;38:306–18. 10.1007/s10942-019-00327-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Richards J, Foster C, Townsend N, et al. Physical fitness and mental health impact of a sport-for-development intervention in a post-conflict setting: randomised controlled trial nested within an observational study of adolescents in Gulu, Uganda. BMC Public Health 2014;14:619. 10.1186/1471-2458-14-619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Eifediyi G, Ojugo AI, Aluede O. Effectiveness of rational Emotive behaviour therapy in the reduction of examination anxiety among secondary school students in Edo state, Nigeria. Asia Pacific Journal of Counselling and Psychotherapy 2018;9:61–76. 10.1080/21507686.2017.1412329 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Osborn TL, Wasil AR, Venturo-Conerly KE, et al. Group intervention for adolescent anxiety and depression: outcomes of a randomized trial with adolescents in Kenya. Behav Ther 2020;51:601–15. 10.1016/j.beth.2019.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Berger R, Benatov J, Cuadros R, et al. Enhancing resiliency and promoting Prosocial behavior among Tanzanian primary-school students: a school-based intervention. Transcult Psychiatry 2018;55:821–45. 10.1177/1363461518793749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jordans MJD, Tol WA, Ndayisaba A, et al. A controlled evaluation of a brief parenting psychoeducation intervention in Burundi. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2013;48:1851–9. 10.1007/s00127-012-0630-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Osborn TL, Rodriguez M, Wasil AR, et al. Single-session digital intervention for adolescent depression, anxiety, and well-being: outcomes of a randomized controlled trial with Kenyan adolescents. J Consult Clin Psychol 2020;88:657–68. 10.1037/ccp0000505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bella-Awusah T, Ani C, Ajuwon A, et al. Effectiveness of brief school-based, group cognitive behavioural therapy for depressed adolescents in South West Nigeria. Child Adolesc Ment Health 2016;21:44–50. 10.1111/camh.12104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kilburn K, Thirumurthy H, Halpern CT, et al. Effects of a large-scale unconditional cash transfer program on mental health outcomes of young people in Kenya. J Adolesc Health 2016;58:223–9. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.09.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Angeles G, de Hoop J, Handa S, et al. Government of Malawi’s unconditional cash transfer improves youth mental health. Social Science & Medicine 2019;225:108–19. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.01.037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Puffer ES, Green EP, Sikkema KJ, et al. A church-based intervention for families to promote mental health and prevent HIV among adolescents in rural Kenya: results of a randomized trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 2016;84:511–25. 10.1037/ccp0000076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bevan Jones R, Thapar A, Stone Z, et al. Psychoeducational interventions in adolescent depression: a systematic review. Patient Educ Couns 2018;101:804–16. 10.1016/j.pec.2017.10.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Dunne T, Bishop L, Avery S, et al. A review of effective youth engagement strategies for mental health and substance use interventions. J Adolesc Health 2017;60:487–512. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.11.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Asuquo SE, Tahlil KM, Muessig KE, et al. Youth engagement in HIV prevention intervention research in sub-Saharan Africa: a Scoping review. J Int AIDS Soc 2021;24:e25666. 10.1002/jia2.25666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Owusu-Addo E, Renzaho AMN, Smith BJ. The impact of cash transfers on social determinants of health and health inequalities in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. Health Policy Plan 2018;33:675–96. 10.1093/heapol/czy020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Pedersen GA, Smallegange E, Coetzee A, et al. A systematic review of the evidence for family and parenting interventions in Low- and middle-income countries: child and youth mental health outcomes. J Child Fam Stud 2019;28:2036–55. 10.1007/s10826-019-01399-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Khanna MS, Carper M. Digital mental health interventions for child and adolescent anxiety. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice 2022;29:60–8. 10.1016/j.cbpra.2021.05.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Rose-Clarke K, Bentley A, Marston C, et al. Peer-facilitated community-based interventions for adolescent health in Low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. PLoS One 2019;14:e0210468. 10.1371/journal.pone.0210468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2022-066586supp001.pdf (5.5MB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information. The data supporting the findings of this study are provided in the supplemental material.