Abstract

Objectives

To identify and explore positive aspects of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) as reported by adults with the diagnosis.

Design

The current study used a qualitative survey design including the written responses to an open-ended question on positive aspects of ADHD. The participants’ responses were analysed using thematic analysis.

Setting

The participants took part in trial of a self-guided internet-delivered intervention in Norway. As part of the intervention, the participants were asked to describe positive aspects of having ADHD.

Participants

The study included 50 help-seeking adults with an ADHD diagnosis.

Results

The participants described a variety of positive aspects related to having ADHD. The participants’ experiences were conceptualised and thematically organised into four main themes: (1) the dual impact of ADHD characteristics; (2) the unconventional mind; (3) the pursuit of new experiences and (4) resilience and growth.

Conclusions

Having ADHD was experienced as both challenging and beneficial, depending on the context and one’s sociocultural environment. The findings provide arguments for putting a stronger emphasis on positive aspects of ADHD, alongside the challenges, in treatment settings.

Trial registration number

Keywords: MENTAL HEALTH, QUALITATIVE RESEARCH, Adult psychiatry

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS OF THIS STUDY

The current study is one of few studies that focuses on positive aspects of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

With the current study design, we could only explore the participants’ experiences with positive aspects of ADHD. Future studies are needed to examine the generalisability of these positive aspects.

The large majority of the sample were women, which makes the findings less transferable to men.

The sample is restricted to including participants who responded to a question regarding positive traits.

Introduction

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a neurodevelopmental disorder with prevalence estimates of approximately 5% of children and 2.6% of adults.1 2 Recently, the number of individuals being diagnosed with ADHD in adulthood has increased, with women being at particular risk for receiving a diagnosis later in life.3 4 The diagnosis of ADHD is characterised by three cardinal symptoms: inattention, hyperactivity and impulsivity.5 Adults with ADHD also tend to face additional challenges related to emotion dysregulation, poor working memory, planning and organisation skills.6 7 These symptoms and challenges are known to interfere with many activities of daily living, with impact on occupational, educational, interpersonal and financial domains.5 Pharmacological treatment is the primary treatment for adults with ADHD, but many seek additional psychological treatment.8 9

Research on ADHD has traditionally focused on the impairments and negative outcomes associated with the diagnosis. When portraying a primarily deficit-oriented view on the diagnosis, it may add to the burden of living with ADHD. For instance, it is well known that individuals with ADHD are prone to experience public stigma, prejudice and criticism based on their diagnosis, which can negatively impact self-esteem, self-efficacy and well-being.10 11 Moreover, a deficit-oriented view of ADHD may overlook strengths of persons with the diagnosis. An alternative approach would be to adopt a more ability-oriented view of ADHD, emphasising the individuals’ resources, abilities and skills.12 This perspective aligns with beliefs of the neurodiversity movement, which has gained considerable recognition with the rise of social media platforms like TikTok and Instagram.13 Unlike the biological-medical perspective of ADHD, the neurodiversity movement advocates that ADHD and similar conditions should be denoted as neurological differences rather than being conceptualised as deficits.14 15 From this perspective, the neurological differences associated with ADHD are considered to be of societal benefit as they contribute to valuable diversity within the population.15

The majority of available studies on psychological treatment interventions for adults with ADHD also tend to have a deficit-oriented focus, with most studies defining successful treatment as reduction in core ADHD symptoms.16 Among 23 studies on cognitive behavioural therapy for adults with ADHD included in a recent systematic review, only one study examined an intervention with an explicit focus on strengths associated with having ADHD.17 18 This particular intervention was found to improve the participants’ knowledge about ADHD and life satisfaction, giving support for incorporation of a strength-based approach in psychological treatment for adults with ADHD.17 Findings from qualitative research further indicate that public mental healthcare is perceived as too deficit centred and symptom centred by adults with ADHD, leading some to seek alternative treatments that are perceived as more strength-based, even if not reimbursed by healthcare insurances.19 The willingness to pay out-of-pocket for these treatments could suggest that the current treatment options do not fully meet the needs of adults with ADHD.19

Taken together, the scientific literature on the strengths associated with ADHD is still scarce.20 Moreover, most studies on ADHD have included clinical samples of children, and less research has focused on adults’ experiences with the diagnosis. However, there are a few recent qualitative studies that have explored the positive experiences of adults with ADHD. A review on qualitative research examining the lived experience of adults with ADHD indicates that certain aspects of ADHD can be experienced as positive.21 Within these studies, attributes like energy, creativity, determination, hyperfocus, adventurousness, curiosity and resilience were emphasised.22–25 However, these studies have largely included small samples of high-functioning adults with ADHD. One exception is the study by Schippers et al,26 which applied both qualitative and quantitative methods to examine perceived positive characteristics with ADHD in a large sample of 206 adults with ADHD.26 Almost all of the participants in the study reported positive aspects related to ADHD, with core themes being creativity, being dynamic, flexibility, socioaffective skills and higher order cognitive skills. There are also a few quantitative studies that have focused on positive aspects of ADHD, in particular, creativity. A review of the link between creativity and ADHD has also shown that creative abilities and achievements were high among individuals with both clinical and subclinical symptoms of ADHD.20 In line with this, some studies have found ADHD to be associated with entrepreneurial intentions and initiation of entrepreneurial actions.27 28 As such, these studies highlight that despite the well-known challenges associated with ADHD, there are also several strengths that may be linked to having the diagnosis.

The current study employs a qualitative design to identify and explore positive aspects of having ADHD. By including a fairly large group of adults with ADHD seeking psychological help (n=50), the study further aims to shed light on how these positive aspects of the diagnosis can be used as part of psychological interventions for this group of adults. In this regard, the current study follows up on findings from previous qualitative studies that explored positive experiences with having the diagnosis. It also resonates with studies, indicating that adults with ADHD advocate for treatment options that are less deficit-oriented. We, thus, believe that an investigation into the positive experiences of help-seeking adults with ADHD would contribute to fill an important gap in the research field. A two-folded focus on both the strengths and challenges related to ADHD may further have a countereffect on the public stigmatisation associated with the diagnosis and help to empower individuals with the diagnosis.

Method

Study design

The current study is a qualitative investigation including written responses from adults with ADHD to an open-ended question about self-perceived positive aspects of having ADHD. The empirical material was analysed using thematic analysis with hermeneutic phenomenological framework.29 30

Study context

The data used in the current study originate from a larger clinical trial of a self-guided internet-delivered intervention for adults with ADHD.31 The clinical trial was a multiple randomised controlled trial, including 109 adults with ADHD aiming to examine whether SMS reminders would improve treatment adherence. The self-guided intervention was accessed online and included seven modules targeting common themes and challenges related to ADHD. The first module was an introduction module, whereas the second to sixth module focused on inattention, inhibitory control, emotion dysregulation, planning and organisation and self-acceptance, and included instructions to various coping strategies. The seventh and last module was a summary module of the entire programme (see Kenter et al32 for a more detailed description of the intervention). The majority of the participants who responded to the postassessment reported to be satisfied with the intervention. The participants received a gift card of 400 NOK (38 EUR) for their participation in the clinical trial, regardless of whether they answered the question assessing positive aspects of ADHD.

The original study protocol planned to use both qualitative and quantitative methods for data analysis, but it was not planned to examine positive aspects of ADHD. However, when reviewing the data, we were struck by its richness and the number of answers given to this open and non-obligatory question on positive aspects of ADHD, which inspired us to conduct a more in-depth examination of the empirical material.

Recruitment and inclusion criteria

Participants who were eligible to participate in the clinical trial were adults with ADHD living in Norway. The participants were recruited through the Norwegian ADHD patient association, via the associations’ Facebook page and email listings. Their members received a link to our project website, where they could read about the study and complete a prescreening survey to confirm their eligibility. The participants who were eligible were invited to a telephone screening interview performed by a clinical psychologist or a psychiatric nurse. In the telephone screening, the participants had to confirm a diagnosis of ADHD, give information about the name of the diagnosing physician, the diagnosing institution and the date of diagnostic decision. They were also asked about current ADHD symptoms, everyday functioning and treatment. Comorbid psychiatric disorders, including depression, suicidality, psychosis, bipolar disorder and substance abuse, were assessed through the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI)33 as part of the telephone screening. This was done to ensure that participants in need of other treatment interventions were not included in the trial. Moreover, all participants had to give their national identity number, which was used to confirm their identity and secure safe login to the online intervention portal. Following inclusion, the participants gave their informed consent to participate and completed the preintervention assessment, including the Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale, used to assess core ADHD symptoms.

The inclusion criteria for the clinical trial were: (a) age 18 years or older; (b) a diagnosis of ADHD; (c) access to a computer or smartphone with internet access, (d) the ability to read and write the Norwegian language. The exclusion criteria were: (a) severe mental illness, such as major depression, suicidality, bipolar disorder, psychosis or substance abuse disorder; (b) currently participating in another psychological treatment. All participants who responded to the question assessing positive aspects of ADHD were included in the current study.

Data collection

The data were collected between June and October 2020. The data material consisted of the participants’ written responses to the question: ‘What do you experience as positive aspects of having ADHD?’. Along with the question, the participants were given some additional guiding questions that could help them write their response: (a) ‘is there any positive aspects related to having ADHD? (b) has ADHD given you any useful knowledge or experiences? (c) has ADHD helped you get in contact with someone you appreciate? These guiding questions were included as examples to help the participants remind themselves of experiences of positive aspects related to having ADHD. The module page also gave some examples of positive characteristics that adults with ADHD may experience, based on previous studies, including being creative, accepting of others, fun, active, explorative, spontaneous and open minded. Considering that the question was text based and, therefore, without the opportunity to ask follow-up questions, we found it necessary to include those examples to provide a context for the participants when answering the question. The participant could write their response to the question in an open-text field on the module page. The mean number of words in the participants’ responses was 72.5, ranging from 1 to 261 words. There were no instructions on number of words or formatting and the question was not obligatory to answer to continue with the module or the intervention. The question was included in the sixth module of intervention, which was named ‘acceptance’ and had an overall focus on self-acceptance and self-compassion, that is, accepting what you cannot change and being kind to yourself. The module included psychoeducation, videos, tasks as well as text and audio instructions to acceptance and self-compassion strategies.

Data analysis

Qualitative analysis

The data were analysed using thematic analysis, employing a hermeneutic phenomenological framework. Thematic analysis is a well-known qualitative method for identifying and analysing themes or patterns across the data.29 Unlike some other methods for qualitative data analysis, thematic analysis does not have a pre-existing theoretical framework and it can, therefore, be applied within different frameworks. In line with the framework we have chosen, we acknowledge that the analytic work is an interpretative and inherently subjective activity. To ensure credibility, we have carefully followed the guidelines prescribed for thematic analysis. The thematic analysis followed the six phases described by Braun and Clarke29: (1) familiarisation with data, (2) generation of codes, (3) search for themes, (4) reviewing themes, (5) finalise and naming of themes and (6) producing the report.

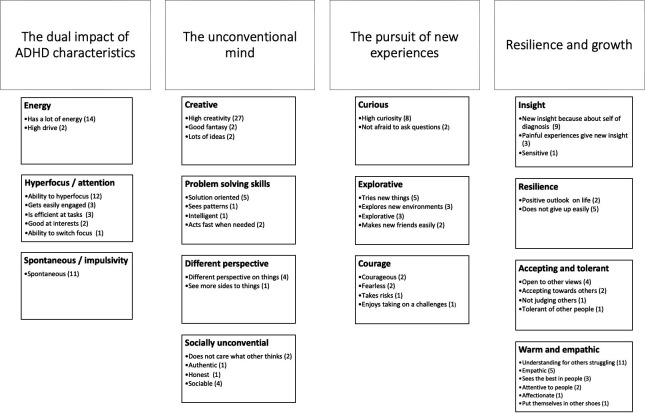

Following these steps, the first author began the analytic work by reading through the data material and taking notes. This included transferring the data material from the online intervention platform to the research server and reading carefully through each of participants’ responses while taking notes on preliminary thoughts and ideas. As a next step, the first author generated codes in line with the analytic focus of the study: ‘what do adults with ADHD experience as positive aspects with the diagnosis’. To safeguard interpretive credibility, the coding was conducted in a ‘low-inference’ manner, where the codes were phrased closely to the participants original accounts. The data material was coded using NVivo software.34 See figure 1 for an overview of all the codes and their frequency. Following the coding, the first author created a visual map where the codes that shared similarities were grouped together. The creation of the visual map was intended to provide an overview of the codes and to obtain preliminary ideas regarding categories and themes. All authors were then given an overview of the codes. The first author also presented the codes with illustrative examples of excerpts from the data to the second author to discuss how the quotes were interpreted. The first and second author continued with the third step in the analysis, namely searching for themes. The initial search for themes resulted in a thematic structure of ten themes. All authors were given an overview of these ten initial themes to provide their input and feedback. As a fourth step, the thematic structure was reviewed in more detail by the first and second author. In this analysis, it became clear that certain themes shared some commonalities, for instance, the initial themes ‘energy’ and ‘hyperfocus’ shared overlapping features, and where, thus, merged into one theme. A new thematic structure was identified, resulting in four core themes (shown in figure 1). These four themes were then finalised and named by the first and second author (step 5) and the final report was produced by all authors (step 6).

Figure 1.

Overview of core themes, subthemes and codes. Note. Core themes are shown within the upper boxes, whereas subthemes are shown the boxes beneath. Codes are shown as bullet points and code frequency is shown in parenthesis.

Quantitative analysis

In addition to the thematic analysis, differences in participant characteristics and ADHD severity scores were examined using independent t-tests and χ2. SPSS was used for quantitative analyses.

Reflexivity

We have strived to maintain reflexivity throughout the research process by consistently examining our pre-existing understanding and assumptions. During both data analysis and interpretation of results, the authors have actively engaged in self-reflection and peer discussions to identify our own preconceptions. For instance, ESN, being a clinical psychologist, has generally been taught that symptoms of ADHD and other psychiatric diagnoses are inherently negative attributes and have been less exposed to the potential positive aspects related to ADHD during her clinical training. To address potential biases, the authors revisited the raw data after creation of the themes to ensure that the participants’ perspectives were accurately represented and to validate their own interpretations.

Patient and public involvement

The user involvement in the larger project (INTROMAT), from which the data are derived, has been extensive. Throughout the 5-year project period, there have been arranged several user meetings with adults with ADHD to examine their needs and preferences to psychological interventions for ADHD. Adults with ADHD have also been involved in the development of content and videos to the intervention as well as evaluating the intervention. In these user meetings, we did not address the research question or research design for the current study; however, the focus of the current study was informed by previous qualitative studies involving adults with ADHD who have expressed a wish for both research and treatment interventions for ADHD to have a stronger focus on positive aspects related to ADHD. The results from the current study will be published on the project website where study participants can be informed. We will also present the findings at meetings for the ADHD patient association, which contributed to the recruitment of participants to the current study.

Results

Participants

Among the 109 participants of the intervention study, 62 participants accessed the module, which included the question on positive aspects of ADHD, and 50 gave their response. The remaining 47 participants did not access the module and, consequently, did not have the opportunity to view and respond to the question. None of these 47 participants accessed the following module either and was thereby considered to be dropouts. When comparing the responders (N=50) to the non-responders (N=59), there were no significant differences in age, medication status, age when diagnosed, gender, education, employment status or ADHD severity scores.

The final sample included 50 participants, with a large majority being women. All but one were diagnosed with ADHD in adulthood, with 4.8 years being the mean time since being diagnosed. A total of 37 (72.5%) participants were full-time employed or students and 30 (58.8%) participants had higher education. When comparing men and women in the final sample, the men were significantly older than the women (see table 1).

Table 1.

Participant characteristics, gender differences and ADHD severity scores

| Total sample | Woman | Man | |

| N (%) | 50 | 44 (88.0%) | 6 (12.0%) |

| Age, M (SD) | 34 (9.5) | 33.3 (8.8) | 42.2 (12.2)* |

| Age when diagnosed, M (SD) | 29.5 (8.5) | 28.9 (8.5) | 33.7 (7.9) |

| ADHD medication, n (%) | |||

| Daily | 38 (76.0%) | 34 (77.3%) | 4 (66.7%) |

| Occasionally | 4 (8.0%) | 4 (9.1%) | − |

| Not taking medication | 8 (16.0%) | 6 (13.6%) | 2 (33.3%) |

| ADHD symptoms | |||

| ASRS full scale, M (SD) | 49.2 (10.4) | 49.6 (10.1) | 46.3 (12.1) |

| Inattention, M (SD) | 26.2 (5.4) | 26.3 (5.5) | 25.5 (5.5) |

| Hyperactivity, M (SD) | 22.9 (6.3) | 23.2 (7.8) | 20.8 (6.1) |

*p < .05.

ADHD, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder; ASRS, Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale; n, number of participants.

Thematic analysis

The participants reported that they experienced a variety of benefits and advantages related to having ADHD, where all but two participants reported that they experienced ADHD to have positive aspects. With regards to ADHD medication, there were two participants who specifically reported that medications contributed to their positive experiences with ADHD, with one participant reporting that the positive aspects of ADHD were only experienced when taking medication. In the thematic analysis, the participants’ positive experiences associated with having ADHD were arranged within four core themes: (1) the dual impact of ADHD characteristics, (2) the unconventional mind, (3) the pursuit of new experiences and (4) resilience and growth (See table 2).

Table 2.

Overview of core themes

| Core theme | Example of participant quotations |

| 1—The dual impact of ADHD characteristics | ‘I have understood that my energy can be used for a lot of good, and that if I use it wrong, it can make things challenging’. |

| 2—The unconventional mind | ‘Creativity, and being able to think outside the norm, is something I really appreciate’. |

| 3—The pursuit of new experiences | ‘I enjoy trying new things and changes. This is the reason why I have the job that I have’. |

| 4—Resilience and growth | ‘The road to my final ADHD diagnosis has been so long and cruel, but I would not have been without all the pain and unbearable years, and all that experience made me know myself in a completely unique way’. |

ADHD, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder.

Theme 1: the dual impact of ADHD characteristics

Many of the participants stated that even core characteristics of ADHD, such as hyperactivity and impulsivity, could be experienced as positive features. Although these core characteristics could be troublesome, they could also be advantageous and beneficial in some situations.

High levels of energy and drive were reported to be useful in many contexts, such as during physical labour, sports, social events or home renovation. One participant stated: I am active. I am often able to do a lot in a short amount of time, and then I get to experience more (woman, 30 years). However, although there were positive aspects to having high energy levels, there could also be downsides: I have understood that my energy can be used for a lot of good, and that if I use it wrong, it can make things challenging (woman, 26 years). The participants also reported that they did not tire as easily as others: If it is something I really like, I have better endurance than others. I can work on something I enjoy forever without stopping (woman, 26 years).

Several participants also reported spontaneity and risk taking, which may be categorised as impulsive traits, as positive aspects associated with ADHD: I am spontaneous/impulsive. I can easily just ‘jump into it’ and that has given me a lot of great experiences (woman, 30 years). It was also mentioned that spontaneity contributed to memorable experiences and learning. However, some emphasised that spontaneity could be challenging as well: I am not really that fond of that spontaneous side of myself because I experience losing control, but at the same time it has given me unique friendships, relations and possibilities (woman, 28 years).

Hyperfocusing, the ability to have an intense focus on an activity for a longer period of time, was commonly mentioned as an advantage of having ADHD. The participants stated that if they were really interested in a topic, they could maintain focus for a long time without being distracted. Hyperfocus was mentioned to be a contributing factor for completing demanding educational courses, school exams and job assignments. One participant stated that hyperfocusing served as a compensatory strategy: I think my ADHD has helped me throughout the exam periods. If it had not been for a kind of hyperfocus, it would not have worked. But then again, I might not have postponed the reading for so long if I did not have ADHD (woman, 23 years). Another participant emphasised that the hyperfocus on useful task for it to be considered as a positive aspect of ADHD: The only positive is hyperfocus on tasks that are really exciting, but for ADHD to be considered positive in this setting, the task has to be something useful, such as school or work (man, 31 years). Most of the participants did not report inattention be positive, however, one participant explicitly mentioned inattention to also have upsides: Inattention can be nice when I actually need to change focus, if something happens while I am driving etc. It is also nice because I have observed some amusing conversations and such when I am actually supposed to be doing something else (woman, 26 years).

Theme 2: the unconventional mind

Many participants reported that they experienced unconventional thinking and behaviour as positive aspects of having ADHD. This included characteristics such as being creative, having novel ideas, seeing things from a different perspective than others and being good at finding solutions. At the same time, it was also emphasised that the social context and expectations present in one’s sociocultural environment could sometimes be an obstacle for utilising these strengths.

Creativity was emphasised to be a positive aspect of ADHD by many participants: Creativity and being able to think outside the norm is something I really appreciate (woman, 26 years).

Creativity was reported to help one to start new projects and find good solutions at work as well as make everyday life more exciting: I am creative and solution-oriented and very passionate about the things that I am interested in (man, 32 years). Creativity was also mentioned to be a good quality when it came to parenting as it facilitated playfulness with one’s children. Although creativity was viewed as a positive trait by many participants, some emphasised a complexity: From my experience in a work-related context, thinking outside the box is not as accepted in all contexts, despite good results’ (woman, 27 years). With this, the participant underscores that whether a quality is deemed as ‘good’ or ‘bad’ is also dependent on one’s social context.

There were also participants who described that they could be socially unconventional and go outside the norm: I do not care that much about what other think (woman, 41 years). Some reported that they could be quite straightforward, unafraid and uninhibited in social situations: I am pretty forward, and I am not afraid to take up space when I need a bit of attention. I know a lot of people and that is probably because I am not scared to say hi to new people (woman, 23 years).

Theme 3: the pursuit of new experiences

There were several participants who reported that they experienced adventurousness and novelty-seeking as positive aspects of ADHD. Being explorative also appeared to be connected to being both curious and courageous, with some participants describing that they were curious of the unknown and not afraid to embark on new ventures.

Many emphasised that they were curious and enjoyed trying new things and seeking new experiences. The participants also reported that they enjoyed learning new things: I seek new environments where I can learn new things (woman, 29 years). Because they enjoyed learning, they also acquired knowledge about various topics. In line with this, one participant also underlined that they would not give up easily when attempting to learn something new: I enjoy trying new things, and if I do not get it right the first time, I will examine the possibility of trying a simpler method. (woman, 30 years). To enjoy novelty was also reported to be of significance to one’s choice of occupation: I enjoy trying new things and changes. This is the reason why I have the job that I have (woman, 42 years).

There were also reports about being courageous and unafraid, which could push one to seek new experiences: I have experienced things that only would have happened by taking a risk (man, 62 years). Moreover, being impulsive could make one more daring: I dare more than when I sit down and think about it (woman, 29 years).

Theme 4: resilience and growth

The final theme centres around the participants’ experiences of growth and insight after facing adversity. The participants underscored that although ADHD indeed could be challenging, especially the process towards being diagnosed with ADHD, coping with these challenges could also foster resilience and growth.

Some of the participants reported to have a better understanding and acceptance for themselves because of ADHD: Being diagnosed with ADHD made me learn a lot about myself. Things I perhaps have been annoyed about, I can now accept and think that it is not ‘my fault’ in a way (woman, 30 years). Although the process of getting diagnosed could be tough, it could also give valuable insight: The road to my final ADHD diagnosis has been so long and cruel, but I would not have been without all the pain and unbearable years, and all that experience made me know myself in a completely unique way, and I have gotten a very valued quality when it comes to being able to reflect over situations both I and others are in (woman, 25 years).

The participants also expressed resilience after coping with previous challenges: ’ am better at handling resistance or challenges now, because I have learned to handle such challenges, it is part of life to have ups and downs (woman, 51 years). Likewise, coping with challenges could also make one more persistent: I have learned to not give up in the face of resistance. Maybe I must take some detours, do things differently than others, find out what works for me and trust myself, but the point is, I can make it if I want to (woman, 28 years).

The experience of receiving the diagnosis appeared to be especially important: To get the diagnosis was a relief because it gave me an explanation for why I did things I did not understand earlier, such as why I was not able to shut up, but talk without thinking, and why my emotions fluctuate so much, and often without me understanding why. It has given me more understanding and acceptance for myself (woman, 57 years). When the participants learned about the diagnosis, it allowed them to be more kind towards themselves: I discovered that I have ADHD in adulthood, so I lived most of my life in the belief that I am like everyone else. I have had high expectations to myself, compared myself to others, and achieved a lot (…) So when I found out about my challenges, it all became like a piece of cake. I could with good reasons lower the expectations to myself and finally rest with a clear conscience (woman, 37 years).

The participants also reported that they were non-judgemental and accepting of other people: Since I am such a “fool” I don’t judge others for being it (woman, 24 years). The participants also reported to be more empathic and understanding of others’ point of view. Several participants had jobs that involved working with people with disabilities, where having ADHD themselves could help them to connect with their students or patients: As a teacher, ADHD helps me to understand students that have a learning disability (man, 31 years). Another participant stated: I understand a part of the youth on a different level than my colleagu|es, and I therefore experience that I am able to get a better connection with the students others find it difficult to get close to (woman, 44 years). Another participant also shared similar experiences: I notice that I can meet children with ADHD with more understanding, so they feel safe with me quickly, and I know I can help them in challenging situations, or prepare them a bit extra, so that they are able to get through their school day (woman, 30 years).

Discussion

The current study aimed to identify and explore positive aspects of having ADHD from the perspective of help-seeking adults with the diagnosis. The participants’ accounts of positive experiences of having ADHD could be arranged within the following four themes: (1) the dual impact of ADHD characteristics, (2) the unconventional mind, (3) the pursuit of new experiences and (4) resilience and growth. Through the discussion, we further seek to highlight how positive experiences with the diagnosis can be used in treatment interventions.

The characteristics of ADHD could be experienced as a double-edged sword, where the traits could be seen as both challenging and beneficial. This is in accordance with findings in several studies included in the review by Ginapp et al21 and Schippers et al26. The direction of this relationship further seemed to be dependent on context and the norms in one’s sociocultural environment, where certain qualities could be deemed as beneficial in some situations, but undesirable in other situations. Although one’s environment appeared to be central in the participants’ experience of duality related to ADHD characteristics, individual factors are still important to take into consideration; one person might find a certain characteristic as beneficial, while another might not share the same perspective. As such, whether a characteristic is seen as positive or negative is likely dependent on a variety of factors, including individual factors, environmental factors and the interaction between the two.

From the perspective of the participants, it appeared that even core diagnostic characteristics of ADHD could be experienced as advantageous. For instance, the high energy associated with hyperactivity could be considered as an advantage in certain social settings and within sports, whereas hyperfocus could be beneficial during school exams or at work. These findings are in line with results reported in previous qualitative studies.22 23 As such, the analytic findings support the notion that some of the characteristics associated with ADHD can be reframed in a more positive manner. Given the high persistence of ADHD symptoms into adulthood, helping adults to explore potential advantages of their symptoms in a treatment setting could perhaps have favourable outcomes for treatment and improve life satisfaction17

On the other hand, the present findings resonate with results from several other previous studies showing that ADHD characteristics are associated with problems that affect daily-life functioning.35–37 Based on the current reports, it appeared that the participants had to figure out the ways to make ADHD work for them, with certain traits, such as hyperfocus and high energy, only being considered beneficial under the right circumstances. This reasoning can imply that a key step in psychological interventions for ADHD would be to not only identify the participants’ strengths but also to examine in what contexts these strengths are useful and potential pitfalls or obstacles for utilising them.

Interestingly, only one of the participants reported inattention to be beneficial. In relation to this, a study on ADHD and identity among youth with ADHD found that while several participants experienced positive sides to hyperactivity and impulsivity and integrated these as part of their identity, inattentive symptoms were not associated with such positive experiences.38 The experience of living with inattentive versus hyperactive/impulsive traits should be an interesting topic for future studies.

The findings further show that creativity seems to be experienced as a core positive aspect of having ADHD. These findings are in line with results from previous studies, which have associated ADHD symptoms with certain qualities of creativity.39 40 Distractibility has, for example, been associated with creative achievements.41 As such, it may be that distractibility makes one notice more so-called ‘irrelevant’ information in one’s environment, which later may be helpful in generating more original ideas.41 Given that creativity may be a strength of ADHD, it should be possible to take advantage of this quality in treatment settings, for example, by including more creative tasks in psychosocial interventions to facilitate engagement and adherence.

The current accounts further show that traits such as adventurousness, exploration and courage may be seen as strengths of ADHD. Such strengths have also been reported by adults with ADHD in previous studies.23 25 42 In their study, Newark et al42 found courage to be a resource among adults with ADHD and they further linked this trait to self-efficacy and self-esteem. The authors further emphasised that courage could be a valuable skill in therapy, a situation where clients indeed are faced with both challenges and novel experiences.36

Lastly, it appeared like coping with the challenges associated with ADHD could lead to resilience and growth for some participants. There were reports about understanding oneself and others in a more nuanced manner, and successful coping was seen as making them more fit to cope with future challenges. This is in line with findings from a previous study including women with ADHD, where the participants identified positive learning from the challenges they had faced.25 When people are faced with adversity, they often underestimate their abilities to cope with the emotional distress and overestimate the intensity and impact of the particular event.43 In line with this, some participants seemed to cope with the challenges related to ADHD in a resilient manner and perhaps even experience growth during times of adversity. These findings may be understood within Dombrowski’s theory of positive disintegration, which posits that emotional difficulty and turmoil are necessary for human growth and development.44 It has further been suggested that resilience is linked to impulsivity, where impulsive traits may help adults to faster move on from their problems, which may be useful in therapy settings.45

Implications

The clinical implications of the findings may be to incorporate a stronger focus on strengths and resources in both the assessment and treatment of ADHD in adulthood. There is a consensus within psychotherapy that treatment should not only focus on the absence of symptoms but also on recovery, coping, well-being and growth.46 However, adults with ADHD still report current treatment options to be too deficit oriented.19 By putting an emphasis on the full range of experiences related to ADHD, both good and bad, one might be able to offer treatment interventions more in line with the needs of adults with ADHD, which may be favourable for treatment engagement and clinical outcomes. For instance, therapist could help adults with ADHD to identify strengths, which may be beneficial for self-esteem and self-efficacy. Within cognitive-behavioural therapy, one could also use positive experiences with ADHD to reframe negative automatic thoughts or maladaptive cognitions. These speculations should indeed provide interesting topics for further studies. A focus on positive sides to ADHD within research may also have societal implications by changing social perception around ADHD and by this reducing stigma related to the diagnosis.

Strengths and limitations

The current study is one of few studies that focus on positive aspects of ADHD, and one of few with a fairly large sample size. Moreover, this study is the only study investigating positive aspects in a sample of help-seeking adults with ADHD. Still, several limitations should be noted. With the current study design and analysis, we can only explore the participants’ experiences with positive aspects of ADHD and give a thematic structure of these experiences. However, future studies combining qualitative and quantitative analyses are needed to further evaluate the generalisability of the positive aspects of ADHD reported in this and previous studies. The sample of the present study was restricted to only include participants who responded to a question regarding positive traits, which only was about half of the participants in the clinical trial. The lower response rate is likely due to the question being asked at the end of the intervention and several participants had been lost to drop-out and thus never accessed the question on positive aspects of ADHD. The impact of being participants in a psychological intervention should also be commented on. For example, it is possible that taking part in the intervention increased the participants’ positive beliefs about themselves and ADHD. The participants did also receive some examples of positive aspects with ADHD in the intervention, which may have influenced their answers. We found it necessary to include these examples since the data collection was conducted online without the guidance of a researcher. As such, when conducting the data analysis and creating the themes, we were careful to examine depth and richness in the participants’ answers and not only frequency. The examples were reported 47 times in the data material, with creativity being the trait most frequently referred to in the data material (27 references). However, creativity was also the most frequently mentioned positive aspect of ADHD in Schippers et al’ s study. Moreover, we found it reassuring that the participants’ answers went beyond the examples given. The participants of the study mainly consisted of high-functioning women in their 20s and 30s who were diagnosed with ADHD as adults and were seeking psychological help for ADHD. The sample did therefore include more females than males, which makes the findings less transferable to males since the clinical expression of ADHD is known to vary with gender.47 It may also be seen as a limitation that the ADHD diagnosis was based on self-report. To ensure validity of the diagnosis, it could have been beneficial to conduct a clinical re-examination to confirm that the participants met the diagnostic criteria. However, all participants were asked to report the date, venue and diagnosing healthcare professional for the diagnosis as well as their national identity number. We, therefore, have trust in the participants’ reports. In addition, because participants with ongoing severe mental illness were excluded from the study, the participants are most likely individuals within the less severe end of the ADHD symptom spectrum.

Future directions

The findings from this study need to be validated by future studies. These studies should not only investigate characteristics of strengths related to ADHD but also in what contexts these strengths are useful and beneficial. Moreover, future studies should investigate the impact of strength-based treatments on both treatment engagement and clinical outcomes. Future research should aim for the development of a valid procedure to assess strengths and positive qualities of adults with ADHD. Moreover, it would also be interesting for future studies to include other observers’ impressions of positive aspects related to ADHD, for instance, family members and clinicians.

Conclusion

The aim of the current study was to identify and explore positive aspects of having ADHD from the perspective of help-seeking adults with the diagnosis. From the perspective of the participants, the characteristics of ADHD could be both beneficial and challenging, depending on the individuals’ contextual environment. For clinicians, it may be important to examine the individual’s positive experiences of ADHD, as this should be capitalised on within treatment. A stronger focus on positive aspects of ADHD in treatment interventions, alongside the challenges, may also help to contribute to support a more ability-oriented view of ADHD.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: ESN contributed to the recruitment of participants for the clinical trial, was responsible for the thematic analysis, interpretation of the results, and drafting of the manuscript. FG contributed substantially to the thematic analysis and interpretation of the results, and with comments and input to different versions of the manuscript. TN was responsible for the clinical trial (PI) and contributed with comments and input to the manuscript. AL was responsible for the idea of the current study and contributed substantially with comments and input on different drafts of the manuscript. All authors have read and accepted the final draft of the manuscript. ESN acts as the guarantor for the work.

Funding: The data used in the current study are from the INTROMAT project, funded by The Research Council of Norway (grant: 259293). ESN received funding from the Western Norway Regional Health Authorities (Helse Vest) for her doctoral thesis (grant: F-11016).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the Methods section for further details.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. The data is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

This study involves human participants and was approved by Regional Committees for Medical and Health Research, Region West Reference ID: 90483. Participants gave informed consent to participate in the study before taking part.

References

- 1.Polanczyk G, de Lima MS, Horta BL, et al. The worldwide prevalence of ADHD: a systematic review and metaregression analysis. Am J Psychiatry 2007;164:942–8. 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.6.942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Song P, Zha M, Yang Q, et al. The prevalence of adult attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: a global systematic review and meta-analysis. J Glob Health 2021;11:04009. 10.7189/jogh.11.04009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chung W, Jiang S-F, Paksarian D, et al. Trends in the prevalence and incidence of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder among adults and children of different racial and ethnic groups. JAMA Netw Open 2019;2:e1914344. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.14344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nussbaum NL. ADHD and female specific concerns: a review of the literature and clinical implications. J Atten Disord 2012;16:87–100. 10.1177/1087054711416909 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5 5th ed. Washington, D.C: American Psychiatric Association, 2013. 10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Willcutt EG, Doyle AE, Nigg JT, et al. Validity of the executive function theory of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a meta-analytic review. Biol Psychiatry 2005;57:1336–46. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shaw P, Stringaris A, Nigg J, et al. Emotion dysregulation in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Am J Psychiatry 2014;171:276–93. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.13070966 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Solberg BS, Haavik J, Halmøy A. Health care services for adults with ADHD: patient satisfaction and the role of psycho-education. J Atten Disord 2019;23:99–108. 10.1177/1087054715587941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Matheson L, Asherson P, Wong ICK, et al. Adult ADHD patient experiences of impairment, service provision and clinical management in England: a qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res 2013;13:184. 10.1186/1472-6963-13-184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beaton DM, Sirois F, Milne E. Experiences of criticism in adults with ADHD: a qualitative study. PLoS One 2022;17:e0263366. 10.1371/journal.pone.0263366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mueller AK, Fuermaier ABM, Koerts J, et al. Stigma in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Atten Defic Hyperact Disord 2012;4:101–14. 10.1007/s12402-012-0085-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lesch K-P. ‘Shine bright like a diamond!’: is research on high‐functioning ADHD at last entering the mainstream? J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2018;59:191–2. 10.1111/jcpp.12887 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McDermott V. “Tell me something you didn't know was neurodivergence-related until recently. I'll start”: tiktok as a public sphere for destigmatizing neurodivergence”. In: Rethinking perception and centering the voices of unique individuals: reframing autism inclusion in praxis. IGI Global, 2022: 127–47. 10.4018/978-1-6684-5103-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ortega F. The cerebral subject and the challenge of neurodiversity. BioSocieties 2009;4:425–45. 10.1017/S1745855209990287 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sonuga-Barke E, Thapar A. The neurodiversity concept: is it helpful for clinicians and scientists? Lancet Psychiatry 2021;8:559–61. 10.1016/S2215-0366(21)00167-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Epstein JN, Weiss MD. Assessing treatment outcomes in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a narrative review. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2012;14:PCC.11r01336. 10.4088/PCC.11r01336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hirvikoski T, Lindström T, Carlsson J, et al. Psychoeducational groups for adults with ADHD and their significant others (PEGASUS): a pragmatic multicenter and randomized controlled trial. Eur Psychiatry 2017;44:141–52. 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2017.04.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fullen T, Jones SL, Emerson LM, et al. Psychological treatments in adult ADHD: a systematic review. J Psychopathol Behav Assess 2020;42:500–18. 10.1007/s10862-020-09794-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schrevel SJC, Dedding C, Broerse JEW. Why do adults with ADHD choose strength-based coaching over public mental health care? A qualitative case study from the Netherlands. SAGE Open 2016;6:215824401666249. 10.1177/2158244016662498 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hoogman M, Stolte M, Baas M, et al. Creativity and ADHD: a review of behavioral studies, the effect of psychostimulants and neural underpinnings. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2020;119:66–85. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2020.09.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ginapp CM, Macdonald-Gagnon G, Angarita GA, et al. The lived experiences of adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a rapid review of qualitative evidence. Front Psychiatry 2022;13:949321. 10.3389/fpsyt.2022.949321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mahdi S, Viljoen M, Massuti R, et al. An international qualitative study of ability and disability in ADHD using the WHO-ICF framework. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2017;26:1219–31. 10.1007/s00787-017-0983-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sedgwick JA, Merwood A, Asherson P. The positive aspects of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a qualitative investigation of successful adults with ADHD. Atten Defic Hyperact Disord 2019;11:241–53. 10.1007/s12402-018-0277-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Redshaw R, McCormack L. “Being ADHD”: a qualitative study. Adv Neurodev Disord 2022;6:20–8. 10.1007/s41252-021-00227-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Holthe MEG, Langvik E. The strives, struggles, and successes of women diagnosed with ADHD as adults. SAGE Open 2017;7:215824401770179. 10.1177/2158244017701799 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schippers LM, Horstman LI, van de Velde H, et al. A qualitative and quantitative study of self-reported positive characteristics of individuals with ADHD. Front Psychiatry 2022;13:922788. 10.3389/fpsyt.2022.922788 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lerner DA, Verheul I, Thurik R. Entrepreneurship and attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a large-scale study involving the clinical condition of ADHD. Small Bus Econ 2019;53:381–92. 10.1007/s11187-018-0061-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wiklund J, Yu W, Tucker R, et al. ADHD, impulsivity and entrepreneurship. J Bus Ventur 2017;32:627–56. 10.1016/j.jbusvent.2017.07.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 2006;3:77–101. 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Binder P-E, Holgersen H, Moltu C. Staying close and reflexive: an explorative and reflexive approach to qualitative research on psychotherapy. Nord Psychol 2012;64:103–17. 10.1080/19012276.2012.726815 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nordby ES, Gjestad R, Kenter RMF, et al. The effect of SMS reminders on adherence in a self-guided internet-delivered intervention for adults with ADHD. Front Digit Health 2022;4:821031. 10.3389/fdgth.2022.821031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kenter RMF, Lundervold AJ, Nordgreen T. A self-guided internet-delivered intervention for adults with ADHD: a protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Internet Interv 2021;26:100485. 10.1016/j.invent.2021.100485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, et al. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry 1998;59 Suppl 20:22–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.QSR . Nvivo 12 computer software; 2016.

- 35.Lefler EK, Sacchetti GM, Del Carlo DI. ADHD in college: a qualitative analysis. Atten Defic Hyperact Disord 2016;8:79–93. 10.1007/s12402-016-0190-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Watters C, Adamis D, McNicholas F, et al. The impact of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in adulthood: a qualitative study. Ir J Psychol Med 2018;35:173–9. 10.1017/ipm.2017.21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Michielsen M, de Kruif J, Comijs HC, et al. The burden of ADHD in older adults: a qualitative study. J Atten Disord 2018;22:591–600. 10.1177/1087054715610001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jones S, Hesse M. Adolescents with ADHD: experiences of having an ADHD diagnosis and negotiations of self-image and identity. J Atten Disord 2018;22:92–102. 10.1177/1087054714522513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Boot N, Nevicka B, Baas M. Creativity in ADHD: goal-directed motivation and domain specificity. J Atten Disord 2020;24:1857–66. 10.1177/1087054717727352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.White HA, Shah P. Creative style and achievement in adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Pers Individ Differ 2011;50:673–7. 10.1016/j.paid.2010.12.015 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zabelina D, Saporta A, Beeman M. Flexible or leaky attention in creative people? Distinct patterns of attention for different types of creative thinking. Mem Cognit 2016;44:488–98. 10.3758/s13421-015-0569-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Newark PE, Elsässer M, Stieglitz R-D. Self-esteem, self-efficacy, and resources in adults with ADHD. J Atten Disord 2016;20:279–90. 10.1177/1087054712459561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wilson TD, Gilbert DT. Affective forecasting: knowing what to want. Curr Dir Psychol Sci 2005;14:131–4. 10.1111/j.0963-7214.2005.00355.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Laycraft K. Theory of positive disintegration as a model of adolescent development. Nonlinear Dynamics Psychol Life Sci 2011;15:29–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Newark PE, Stieglitz R-D. Therapy-relevant factors in adult ADHD from a cognitive behavioural perspective. Atten Defic Hyperact Disord 2010;2:59–72. 10.1007/s12402-010-0023-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Seligman ME. Flourish: a visionary new understanding of happiness and well-being. Simon and Schuster, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vildalen VU, Brevik EJ, Haavik J, et al. Females with ADHD report more severe symptoms than males on the adult ADHD self-report scale. J Atten Disord 2019;23:959–67. 10.1177/1087054716659362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. The data is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.