Abstract

Background

Timely and appropriate treatment for childhood illness saves the lives of millions of children. In low-middle-income countries such as sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), poor healthcare-seeking behavior for childhood illnesses is identified as a major contributor to the increased risk of child morbidity and mortality. However, studies are limited on Factors associated with mother's healthcare-seeking behavior for symptoms of acute respiratory infection in under-five children in sub-Saharan Africa.

Objective

To examine factors associated with a mother's healthcare-seeking behavior for symptoms of acute respiratory infection in under-five children in sub-Saharan Africa.

Methods

A secondary data analysis was conducted based on the latest Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) data of 36 sub-Saharan African countries. A total weighted sample of 16,925 mothers who had under-five children with acute respiratory infection symptoms was considered. The Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC), Median Odds Ratio (MOR), and Likelihood Ratio (LR) tests were done to assess the presence of clustering. Model comparison was made based on deviance (-2LLR) value. Variables with a p-value < 0.2 in the bivariable multilevel robust Poisson analysis were considered for the multivariable analysis. In the multivariable multilevel robust Poisson regression analysis, the Adjusted Prevalence Ratio (APR) with the 95% Confidence Interval (CI) was reported to declare the statistical significance and strength of the association.

Results

The prevalence of mother's healthcare-seeking behavior for symptoms of acute respiratory infection in under-five children in SSA was 64.9% (95% CI: 64.2%, 65.7%). In the multivariable analysis; mothers who attained primary education (APR = 1.11, 95% CI: 1.08, 1.15), secondary education (APR = 1.13, 95% CI: 1.09, 1.18), and higher education (APR = 1.19, 95% CI: 1.11, 1.27), belonged to the richest household (APR = 1.07: 95% CI: 1.02, 1.12), had media exposure (APR = 1.11, 95% CI: 1.08, 1.15), currently working (APR = 1.08, 95% CI: 1.06, 1.11), had ANC use (APR = 1.25: 95% CI: 1.17, 1.35), health facility delivery (APR = 1.10, 95% CI: 1.07, 1.14), belonged to West Africa (APR = 1.04, 95% CI: 1.01, 1.08) and being in the community with high media exposure (APR = 1.04, 95% CI: 1.02, 1,07) were significantly associated with higher prevalence of mother's healthcare-seeking behavior for symptoms of acute respiratory infection in under-five children. On the other hand, distance to a health facility (APR = 0.87, 95% CI: 0.84, 0.91), and being in central Africa (APR = 0.87, 95% CI: 0.84, 0.91) were significantly associated with a lower prevalence of mother's healthcare-seeking behavior for symptoms of acute respiratory infection in under-five children.

Conclusion

Mother's healthcare-seeking behavior for symptoms of acute respiratory infection in under-five children. It was influenced by maternal education, maternal working status, media exposure, household wealth status, distance to the health facility, and maternal health care service use. Any interventions aiming at improving maternal education, maternal healthcare services, and media access are critical in improving mothers' healthcare-seeking behavior for symptoms of acute respiratory infection in under-five children, hence lowering the prevalence of ARI-related death and morbidity.

Keywords: Under-five children, Multilevel robust Poisson regression, SSA, Mothers healthcare-seeking behavior

Background

Globally, acute Respiratory Infections (ARIs) are the leading causes of under-five morbidity and mortality [1, 2]. They account for 6% of the worldwide disease burden [3–5]. While sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) has made significant progress in lowering under-five mortality, the progress is far below the expected [6–8]. ARIs are caused by a wide range of pathogens such as Streptococcus pneumonia, Haemophilus influenzae, Staphylococcus aureus, etc. [9].

Effective antibiotic treatment for ARIs is available, and timely treatment can prevent the majority of ARI-related deaths [10, 11]. Effective treatment of acute respiratory infections in children under the age of five requires early diagnosis, timely medical attention seeking, and administration of the necessary drugs [12]. However, less than one-third of ARI cases in low-income countries [13], and only 40% of children under the age of five in SSA with ARI symptoms obtained medical treatment [14].

One of the key components of the Integrated Management of Childhood Illness Strategy (IMCIS) is the World Health Organization's (WHO) effort to improve family and community healthcare practices towards disease detection and care-seeking behaviors [15, 16]. However, IMCIS implemented in Low and Middle-income Countries (LMIC) specifically in SSA has not achieved its target [17]. Mothers or caregivers play a crucial role in recognizing the symptoms of acute respiratory infection in under-five children [18, 19]. Previous studies conducted on mother's healthcare-seeking behavior for symptoms of acute respiratory infection in under-five children showed that maternal education [20, 21], household wealth status [19, 22], distance to a health facility [23, 24], residence [20, 25], childhood nutritional status [19, 26], maternal occupation [22, 27], husband education [28], perceived severity [20, 21, 29], previous history of under-five death [20], media exposure [14], ANC visit [30], and place of delivery [31, 32] were found to be significant predictors.

Despite the ongoing advancement of medicine, ARIs continue to impose a significant burden on under-five morbidity and mortality in sub-Saharan African countries. This is closely linked to failure to seek health care and delay in seeking timely and appropriate care. In addition, ARIs continue to be one of the major health issues in SSA, and as far as we are concerned a study on healthcare-seeking behavior for symptoms of ARIs among under-five children and associated factors in SSA using a multilevel robust Poisson regression model has not yet been done. Even though the mother's healthcare-seeking behavior was not a rare occurrence, prior studies in different Sub-Saharan African countries reported odds ratios to quantify the association [33–35]. When the prevalence exceeds 10%, using a multilevel Poisson regression model with robust error variance in cross-sectional studies prevents overestimation of the association between outcome and explanatory variables [36]. As a result, we examined mothers' healthcare-seeking behavior in SSA for under-five children with ARI symptoms.

Methods

Study design and settings

A secondary data analysis was conducted based on the most recent Demographic and Health Surveys (DHSs) of 36 sub-Saharan African countries conducted from 2005 to 2019. DHS is a community-based cross-sectional study conducted in five-year intervals to generate basic health and health-related indicators of the population.

Study population and sampling

The study population was the mothers who had under-five children with ARI symptoms. Two-stage stratified cluster sampling technique was employed using Enumeration Areas (EAs) as primary sampling units and households as secondary sampling units [37]. The Kids Record dataset (KR file) was used for this study after we obtained an authorization letter from the measure DHS program for data access. A total of 16,925 weighted samples were considered for this study. The detailed methodology is available in the following references [38, 39].

Measurement of variables

Dependent variable

Mother's healthcare-seeking behavior for symptoms of acute respiratory infection in under-five children was the dependent variable. The presence of ARIs is defined as children having a history of cough accompanied by short, rapid breathing or difficulty breathing and fever within two weeks preceding the survey. In DHS, mothers of under-five children were asked whether their children had a history of cough within two weeks preceding the survey. For children who had a cough, the mother was asked whether the child's cough was accompanied by short, rapid breathing or difficulty breathing and fever within two weeks preceding the survey. It was obtained from the DHS question "Did he/she breathe faster than usual with short, rapid breaths or have difficulty breathing in the 2 weeks preceding the survey?”. Then classified as "yes" if a child meets all the aforementioned conditions and "no" if a child does not [40]. This study was limited to mothers who had children aged 0–59 months with symptoms of ARIs within two weeks preceding the survey. Following that, it was categorized as "Yes" if they sought medical attention for their ARI symptoms, and "No" if they did not.

Independent variables

Maternal age, maternal educational status, household wealth status, media exposure, sex of a child, birth size, place of delivery, had ANC visit, maternal working status, stunting, wasting, underweight, marital status, and husband education were level one (individual level) variables. On the other hand, residence, sub-Saharan African region, distance to the health facility, community media exposure, community maternal education, and community poverty were level two (community level) variables.

To assess a child's nutritional status DHS used anthropometric measures (height, age, and weight), height for age measures stunting, weight for height measured wasting, and weight for age measured for underweight. Compared with the reference population of children, the children < -3 standard deviations were severe malnutrition and between -3 and -2 standard deviations were moderate.

Media exposure was calculated by aggregating three variables such as watching television, listening to the radio, and reading newspapers. Then, categorized as having media exposure if a mother has been exposed to at least one of the three and not if she had no exposure to any of the media sources.

In DHS data, there was no variable collected at the community level except residence, and distance to the health facility. Therefore, we generated community media exposure by aggregating listening to the radio, watching television, and reading newspapers at the cluster level. These were categorized as higher community media exposure and lower media exposure based on the national median value of media exposure since it was not normally distributed. Community maternal education and community poverty were generated by aggregating maternal education and wealth status at the cluster/enumeration area levels. Then categorized as higher community maternal education and poverty based on the national median value of maternal education and poverty since they were not normally distributed.

Data management and analysis

STATA version 17 and R version 4.1.3 statistical software were used for data management and analysis. All the results were based on the weighted data. DHS is a cross-sectional study, and the prevalence of mothers seeking healthcare for ARI symptoms in children under the age of five was 64.9%, which was larger than 10%. In this scenario, reporting the odds ratio could overestimate the relationship between the independent variables and the mother's healthcare-seeking behavior for symptoms of ARIs in children under the age of five. Therefore, the prevalence ratio is the best measure of association for the current study. To obtain the prevalence ratio, we have fitted a multilevel Poisson regression model with robust variance.

We preferred this model for three reasons. Firstly, when the magnitude of the outcome variable is common, the odds ratio obtained using the binary logistic regression overestimates the strength of the relationship. Secondly, because the DHS data is hierarchical, mothers were nested within cluster/EA. Thirdly, the multilevel robust Poisson regression model outperformed the multilevel log-binomial regression model in terms of convergence. Therefore, this model accounts for data dependencies as well as the problem of overestimation.

Likelihood Ratio (LR) test, Intra-class Correlation Coefficient (ICC), and Median Odds Ratio (MOR) were computed to measure the variation between clusters. The ICC quantifies the degree of heterogeneity between clusters (the proportion of the total observed individual variation in mothers' healthcare-seeking behavior for symptoms of ARIs among children under age five that is attributable to cluster variations) [41].

π2/3 is the individual-level variance which is approximated to 3.29, and represents the community-level variance

But MOR is quantifying the variation or heterogeneity in outcomes between clusters. It is defined as the median value of the odds ratio between the cluster more likely to seek health care for symptoms of ARIs of children under age five and the cluster at lower risk when randomly picking out two clusters (EAs) [42].

We have fitted four models separately. Model 1 (null model) was fitted without an independent variable to estimate the cluster-level variation of the mother's healthcare-seeking behavior in SSA. Model 2 and Model 3 were adjusted for individual-level variables and community-level variables, respectively. Model 4 was the final model adjusted for individual and community-level variables simultaneously. Variables with a p-value < 0.2 in the bi-variable multilevel Poisson regression analysis were considered for the multivariable analysis. Deviance (-2Log-likelihood Ratio (-2LLR)) was used to compare models, and a model with the lowest deviance was considered the best-fit model. Finally, the Adjusted Prevalence Ratio (APR) with its 95% confidence interval (CI) was reported to declare the statistical significance and strength of the association.

Ethical consideration

Permission to get access to the data was obtained from the measure DHS program online request from http://www.dhsprogram.com.website and the data used were publicly available with no personal identifier. The data used for this study were publicly available with no personal identifier. For the details see https://dhsprogram.com/methodology/Protecting-the-Privacy-of-DHS-SurveyRespondents.cfm.

Results

Descriptive characteristics of mothers of children under age five with ARI symptoms

A total of 16,925 mothers of children under the age of five with symptoms of ARI were included in this study. More than half (52.1%) of the children were males and nearly one-third (30.9%) of mothers were aged 15–24 years. About 4,224 (25%) and 2,456 (14.5%) of the children belonged to the poorest and richest households, respectively. The majority (72.3%) of children lived in rural areas, and 42.4% were in East African countries. About 43.4%, 36.5%, and 45.6% of children under age five were severely wasted, severely stunted, and severely underweight, respectively (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic, socio-economic, and health-related characteristics of mothers of under-five children with symptoms of ARIs

| Variables | Frequency (n = | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Residence | ||

| Urban | 4695 | 27.7 |

| Rural | 12,230 | 72.3 |

| Maternal age | ||

| 15–24 | 5222 | 30.9 |

| 25–34 | 8105 | 47.9 |

| ≥ 35 | 3598 | 21.2 |

| Maternal education status | ||

| No | 5924 | 35.0 |

| Primary | 6836 | 40.4 |

| Secondary | 3737 | 22.1 |

| Higher | 428 | 2.5 |

| Household wealth status | ||

| Poorest | 4224 | 25.0 |

| Poorer | 3798 | 22.4 |

| Middle | 3347 | 19.8 |

| Richer | 3100 | 18.3 |

| Richest | 2456 | 14.5 |

| Media exposure | ||

| No | 5718 | 33.8 |

| Yes | 11,207 | 66.2 |

| Sex of child | ||

| Male | 8811 | 52.1 |

| Female | 8114 | 47.9 |

| Birth size | ||

| Average | 6611 | 39.1 |

| Small | 4145 | 24.5 |

| Large | 6169 | 36.4 |

| Place of delivery | ||

| Home | 5969 | 35.3 |

| Health facility | 10,956 | 64.7 |

| Had ANC visit | ||

| No | 1180 | 7.0 |

| Yes | 15,745 | 93.0 |

| Distance to a health facility | ||

| Not a big problem | 10,166 | 60.1 |

| A big problem | 6759 | 39.9 |

| Maternal working status | ||

| Not working | 5567 | 34.6 |

| Working | 10,517 | 65.4 |

| Stunting | ||

| Normal | 6642 | 39.2 |

| Moderate | 1899 | 11.2 |

| Severe | 6169 | 36.5 |

| Wasting | ||

| Normal | 9018 | 53.3 |

| Moderate | 555 | 3.3 |

| Severe | 7352 | 43.4 |

| Underweight | ||

| Normal | 7992 | 47.2 |

| Moderate | 1216 | 7.2 |

| Severe | 7717 | 45.6 |

| Marital status | ||

| Single | 1034 | 6.1 |

| Married | 14,662 | 86.6 |

| Widowed | 220 | 1.3 |

| Divorced | 1010 | 6.0 |

| Husband’s education status (n = 14,816) | ||

| No | 4475 | 31.6 |

| Primary | 4852 | 34.2 |

| Secondary | 4098 | 28.9 |

| Higher | 761 | 5.4 |

| sub-Saharan Africa region | ||

| East Africa | 7179 | 42.4 |

| Central Africa | 4245 | 25.1 |

| Southern Africa | 714 | 4.2 |

| West Africa | 4787 | 28.3 |

| Community media exposure | ||

| Low | 9113 | 53.8 |

| High | 7812 | 46.7 |

| Community maternal education | ||

| Low | 13,931 | 82.3 |

| High | 2994 | 17.7 |

| Community poverty | ||

| Low | 9404 | 55.6 |

| High | 7521 | 44.4 |

Prevalence of mothers’ healthcare-seeking behavior for symptoms of ARIs among children under age five in SSA

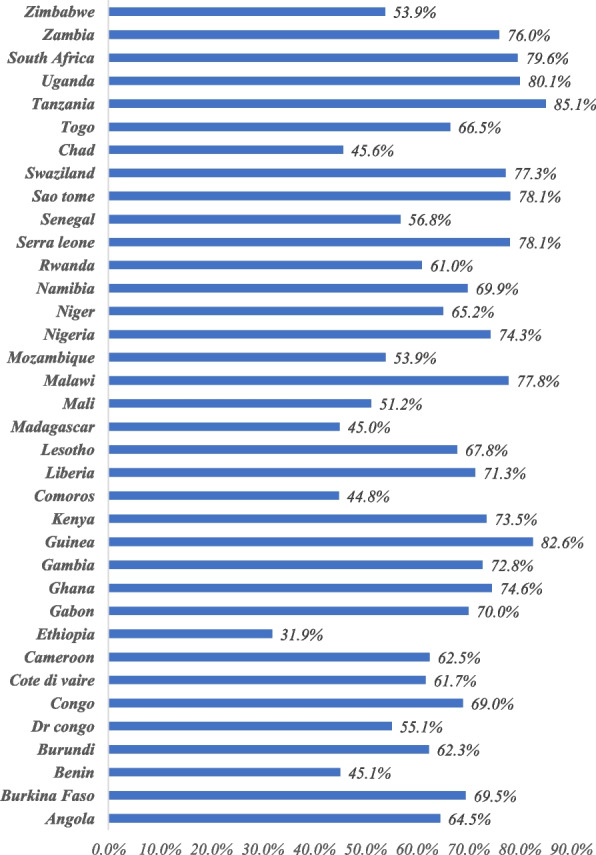

The prevalence of mothers’ healthcare-seeking behavior for symptoms of ARIs among children under age five in SSA was 64.9% (95% CI: 64.2%, 65.7%), it ranged from 31.9% in Ethiopia to 85.1% in Tanzania (Fig. 1). The prevalence of mothers' healthcare-seeking behavior for symptoms of ARIs among children had significant differences by residence, maternal age, maternal education, mothers working status, SSA region, community media exposure, media exposure, community maternal education, wealth status, community poverty, distance to health facility, place of delivery, ANC visit, stunting status, wasting status and underweight status (p < 0.05) (Table 2).

Fig. 1.

The percentage of mothers’ healthcare-seeking behaviour across countries

Table 2.

Distribution of study participants characteristics by their healthcare seeking behaviour for symptoms of acute respiratory infections in under-five children in SSA

| Variables | Did not seek medical care | Sought medical care | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Residence | |||

| Urban | 1322 (28.15) | 3374 (71.85) | 0.00001 |

| Rural | 4612 (37.71) | 7618 (62.29) | |

| Maternal age | |||

| 15–24 | 1755 (33.61) | 3466 (66.39) | 0.018 |

| 25–34 | 2901 (35.79) | 5204 (64.21) | |

| ≥ 35 | 1278 (35.51) | 2321 (64.49) | |

| Maternal education status | |||

| No | 2591 (43.74) | 3333 (56.26) | 0.00001 |

| Primary | 2284 (33.41) | 4552 (66.59) | |

| Secondary | 967 (25.87) | 2770 (74.13) | |

| Higher | 91 (21.33) | 337 (78.67) | |

| Household wealth status | |||

| Poorest | 1739 (41.18) | 2484 (58.82) | 0.00001 |

| Poorer | 1387 (36.52) | 2411 (63.48) | |

| Middle | 1202 (35.91) | 2145 (64.09) | |

| Richer | 1011 (32.60) | 2089 (67.40) | |

| Richest | 595 (24.21) | 1861 (75.79) | |

| Media exposure | |||

| No | 2576 (45.05) | 3142 (54.95) | 0.0001 |

| Yes | 3358 (29.96) | 7849 (70.04) | |

| Sex of child | |||

| Male | 3010 (34.16) | 5801 (65.84) | 0.144 |

| Female | 2924 (36.03) | 5190 (63.97) | |

| Birth size | |||

| Average | 2215 (33.49) | 4397 (66.51) | 0.238 |

| Small | 1526 (36.81) | 2619 (63.19) | |

| Large | 2194 (35.56) | 3975 (64.44) | |

| Place of delivery | |||

| Home | 2649 (44.37) | 3320 (55.63) | 0.0001 |

| Health facility | 3285 (29.98) | 7671 (70.02) | |

| Had ANC visit | |||

| No | 680 (57.64) | 500 (42.36) | 0.0001 |

| Yes | 5253 (33.37) | 10,492 (66.63) | |

| Distance to a health facility | |||

| Not a big problem | 3310 (32.56) | 6857 (67.44) | 0.0001 |

| A big problem | 2623 (38.82) | 4135 (61.18) | |

| Maternal working status | |||

| Not working | 2479 (38.69) | 3929 (61.31) | 0.0001 |

| Working | 3454 (32.85) | 7063 (67.15) | |

| Stunting | |||

| Normal | 2383 (35.87) | 4259 (64.13) | 0.044 |

| Moderate | 719 (37.88) | 1180 (62.12) | |

| Severe | 2831 (33.77) | 5553 (66.23) | |

| Wasting | |||

| Normal | 3283 (36.40) | 5735 (63.60) | 0.001 |

| Moderate | 222 (40.08) | 333 (59.92) | |

| Severe | 2429 (33.03) | 4924 (66.97) | |

| Underweight | |||

| Normal | 2833 (35.45) | 5159 (64.55) | 0.0001 |

| Moderate | 500 (41.13) | 716 (58.87) | |

| Severe | 2600 (33.69) | 5117 (66.31) | |

| Marital status | |||

| Single | 291 (28.13) | 743 (71.87) | 0.0001 |

| Married | 5241 (35.75) | 9421 (64.25) | |

| Widowed | 73 (33.51) | 146 (66.49) | |

| Divorced | 328 (32.51) | 682 (67.49) | |

| Husband’s education status (n = 14,816) | |||

| No | 1934 (43.22) | 2541 (56.78) | 0.0001 |

| Primary | 1725 (35.56) | 3126 (64.44) | |

| Secondary | 1325 (32.32) | 2774 (67.68) | |

| Higher | 161 (21.20) | 600 (78.80) | |

| sub-Saharan Africa region | |||

| East Africa | 2368 (32.99) | 4811 (67.01) | 0.0001 |

| Central Africa | 1799 (42.38) | 2446 (57.62) | |

| West Africa | 1575 (32.89) | 3212 (67.11) | |

| Southern Africa | 192 (26.85) | 522 (73.15) | |

| Community media exposure | |||

| Low | 3546 (38.91) | 5567 (61.09) | 0.0001 |

| High | 2388 (30.57) | 5424 (69.43) | |

| Community maternal education | |||

| Low | 5060 (36.32) | 8871 (63.68) | 0.0001 |

| High | 874 (29.19) | 2120 (70.81) | |

| Community poverty | |||

| Low | 3176 (33.78) | 6228 (66.22) | 0.013 |

| High | 2757 (36.66) | 4764 (63.34) | |

Associated factors of mother's healthcare-seeking behavior for symptoms of acute respiratory infection in under-five children in SSA

In the null model, there was statistically significant variability in the odds of the mother's healthcare-seeking behavior for symptoms of acute respiratory infection in under-five children between clusters (the LR test was statistically significant (p = 0.0001)). Though the ICC value in the null model was 3.4%, the MOR revealed that if we randomly select two mothers from different clusters and transfer women from the cluster with a lower likelihood of health care seeking behavior to cluster with higher healthcare-seeking behavior, she could have 1.42 times higher prevalence of seeking health care for symptoms of ARI. Therefore, a multilevel robust Poisson regression model was fitted, and the final model was the best-fitted model since it has the lowest deviance value (deviance = 31,006,76).

In the final multivariable multilevel robust Poisson regression model; maternal educational status, household wealth status, media exposure, mother working status, ANC visits, and place of delivery were among the individual factors associated with mothers' healthcare-seeking behavior for symptoms of ARIs among children under age five. Sub-Saharan African region, distance to the health facility, and community media exposure were among the community-level factors associated with mothers' healthcare-seeking behavior for symptoms of ARIs in children under age five.

Mothers' who attained primary, secondary, and higher education had 1.11 times (APR = 1.11, 95% CI: 1.08, 1.15), 1.13 times (APR = 1.13, 95% CI: 1.09, 1.18), and 1.19 times (APR = 1.19, 95% CI: 1.11, 1,27) higher prevalence of seeking health care for symptoms of ARIs of children under age five than mothers who had no formal education, respectively. The prevalence of seeking health care for symptoms of children under age five among mothers belonging to the richest household was 1.07 times (APR = 1.07, 95% CI: 1.02, 1.12) higher than mothers belonging to the poorest household. Mothers who had media exposure had 1.11 times (APR = 1.11, 95% CI: 1.08, 1.15) higher prevalence of seeking health care for symptoms of ARIs than those who had no exposure to media. Compared to mothers who had no work, mothers who were working had 1.08 times (APR = 1.08, 95% CI: 1.06, 1.11) higher prevalence of seeking health care for symptoms of ARIs in children under five age. Mothers who had ANC visits for the index pregnancy had 1.25 times (APR = 1.25, 95% CI: 1.17, 1.35) higher prevalence of seeking health care for symptoms of ARI than those who had no ANC visits. Similarly, the prevalence of seeking health care for symptoms of ARI in children under age five among mothers who gave birth at a health facility was 1.10 times (APR = 1.10, 95% CI: 1.07, 1.14) higher compared to mothers who gave birth at home.

The prevalence of seeking healthcare for symptoms of ARIs among children under the age of five was decreased by 13% (APR = 0.87, 95% CI: 0.84, 0.91) among mothers in East Africa. Whereas mothers in West Africa had 1.04 times (APR = 1.04, 95% APR = 1.01, 1,08) higher prevalence of seeking healthcare for symptoms of ARIs than mothers in East Africa. Regarding distance to the health facility, mothers who had a big problem with the health facility had 0.95 times (APR = 0.95, 95% CI: 0.93, 0.98) decreased prevalence of seeking healthcare for symptoms of ARIs. Being from communities with a high level of media exposure had 1.04 times (APR = 1.04, 95% CI: 1.02, 1.07) higher prevalence of seeking healthcare for children under age five compared to mothers in the community with a low level of media exposure (Table 3).

Table 3.

Multilevel robust Poisson regression analysis of factors associated with mother's healthcare-seeking behaviour for symptoms of ARIs among children under age five in sub-Saharan Africa

| Variables | Null model | Model I (Individual-level variables) | Model II (Community level characteristics) | Model III (Both individual and community level variables) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PR with 95% CI | PR with 95% CI | PR with 95% CI | ||

| Maternal age (in years) | ||||

| 15–24 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 25–34 | 0.97 (0.95, 1.00) | 0.97 (0.95, 1.00) | ||

| ≥ 35 | 0.99 (0.95, 1.02) | 0.99 (0.95, 1.02) | ||

| Maternal education status | ||||

| No | 1 | 1 | ||

| Primary | 1.09 (1.06, 1.13) | 1.11 (1.08, 1.15)** | ||

| Secondary | 1.10 (1.06, 1.14) | 1.13 (1.09, 1.18)** | ||

| Higher | 1.17 (1.10,1.25) | 1.19 (1.11, 1.27)** | ||

| Household wealth status | ||||

| Poorest | 1 | 1 | ||

| Poorer | 1.03 (0.99, 1.07) | 1.02 (0.98, 1.06) | ||

| Middle | 1.02 (0.98, 1.06) | 1.01 (0.97, 1.05) | ||

| Richer | 1.02 (0.98, 1.07) | 1.01 (0.97, 1.06) | ||

| Richest | 1.09 (1.04, 1.13) | 1.07 (1.02, 1.12)* | ||

| Media exposure | ||||

| No | 1 | 1 | ||

| Yes | 1.16 (1.12, 1.19) | 1.11 (1.08, 1.15)** | ||

| Maternal working status | ||||

| No | 1 | 1 | ||

| Yes | 1.07 (1.04, 1.10) | 1.08 (1.06, 1.11)* | ||

| Had ANC visit | ||||

| No | 1 | 1 | ||

| Yes | 1.30 (1.21, 1.40) | 1.25 (1.17, 1.35)* | ||

| Place of delivery | ||||

| Home | 1 | 1 | ||

| Health facility | 1.10 (1.07, 1.14) | 1.10 (1.07, 1.14)* | ||

| Residence | ||||

| Urban | 1 | 1 | ||

| Rural | 0.90 (0.87, 0.92) | 0.99 (0.96, 1.03) | ||

| Sub-Saharan African region | ||||

| East Africa | 1 | 1 | ||

| Central Africa | 0.83 (0.79, 0.86) | 0.87 (0.84, 0.91)* | ||

| Southern Africa | 1.04 (0.99, 1.09) | 1.02 (0.97, 1.07) | ||

| West Africa | 0.98 (0.95, 1.01) | 1.04 (1.01, 1.08)* | ||

| Distance to the health facility | ||||

| Not a big problem | 1 | 1 | ||

| Big problem | 0.94 (0.91, 0.97) | 0.95 (0.93, 0.98)* | ||

| Community media exposure | ||||

| Low | 1 | 1 | ||

| High | 1.07 (1.04, 1.10) | 1.04 (1.02, 1.07)* | ||

| Community maternal education | ||||

| Low | 1 | 1 | ||

| High | 1.04 (1.01, 1.08) | 1.02 (0.99, 1.06) | ||

| Community poverty | ||||

| Low | 1 | 1 | ||

| High | 0.99 (0.96, 1.02) | 1.01 (0.98, 1.03) | ||

| Model comparison | ||||

| LLR | -15,669.87 | -15,533.28 | -15,599.73 | -15,503.38 |

| Deviance | 31,339.74 | 31,066.56 | 31,199.46 | 31,006,76 |

| AIC | 31,341.74 | 31,094.55 | 31,217.46 | 31,050.77 |

| BIC | 31,349.47 | 31,202.79 | 31,287.04 | 31,220.85 |

AIC Akaike Information Criteria, ANC Antenatal Care, BIC Bayesian Information Criteria, LLR Log-likelihood Ratio, PR Prevalence Ratio

* p-value < 0.05, ** p-value < 0.01

Discussion

The study found that the prevalence of mothers’ healthcare-seeking behavior for symptoms of ARIs among children under age five in SSA was 64.9% with considerable variation across countries. This finding is higher than the previous study reported in the Philippines (53.4%) [43]. Improved access to healthcare and a better understanding among mothers of the severity of acute respiratory infections in children under five might be the reason for the increasing proportion of children under five seeking medical attention for symptoms of ARIs [44]. In addition, in sub-Saharan African countries to tackle the problem of access to health care and financial crisis, community health insurance has been established and is currently widely implemented to enhance communities' healthcare-seeking behavior for illnesses [45]. However, this finding was lower than studies reported in high-income countries [20, 46, 47], this could be due to the scarcity of public financing, a poor public system in the supply of essential health care, and the government's inability to allocate adequate financing to its health system in sub-Saharan African countries compared to the developed nations [48, 49].

Consistent with studies reported in Ghana [50], Bangladesh [19], and Nepal [51], maternal education was found significant predictor of health-seeking behavior for symptoms of ARIs among under-five children. This could be due to educated mothers having good access to information on common childhood infections like acute respiratory infections and their symptoms [52, 53]. Besides, education can empower women to make health care decisions and their ability to seek health care for their children [54]. Another significant predictor was household wealth status. This is in line with a study's findings in Indonesia [55] and SSA [14]. This could be attributable to mothers with good incomes who can pay for medical care and afford medical assurance hence they are capable of seeking health care whenever their child feels sick [26].

Media exposure enhances mothers' healthcare-seeking behavior for symptoms of ARIs among under-five children. This is in line with a study reported in rural Bangladesh [56], this could be due to media exposure enables mothers to seek key messages on upper respiratory infection symptoms, its severity, and management, which in turn, enhances mothers' seek care at the health facility [57]. Media exposure is a vital tool for health promotion and has a significant positive impact on healthcare service utilization [58]. Health facility delivery and ANC visits found significant positive predictors of the healthcare-seeking behavior of mothers for symptoms of ARI among children under age five. This is supported by previous study findings [28, 55], this is because having previous exposure to maternal and child health care services is important to their awareness and trust about health care services, the relevance of seeking health care services, and the accessibility of services sought for the treatment of their children. Having ANC visits and giving birth at a health facility enhances their interest in health care services including health care providers and strongly motivated to seek health care when their child shows signs and symptoms of diseases [59, 60].

Another important predictor significantly associated with the mother’s healthcare-seeking behavior was the distance to a health facility. Mothers who had big problems with health facilities had a decreased chance of seeking healthcare for symptoms of ARI among children under five compared to mothers where the distance to health facilities was not a big problem. It is in line with previous studies [50, 61], this might be because mothers who with a big problem reaching a health facility need to use transportation facilities or travel a long distance to reach the facility, which in turn contributes not to seeking health care for their child [62]. In addition, mothers who are near the health facility are more likely to visit health care facilities as they are free from transportation costs to reach the health facility [13, 63, 64]. Compared to mothers who had no work, working mothers had an increased chance of seeking health care for symptoms of ARIs among under-five children. This finding is consistent with studies reported in Nigeria [21], and India [65], this is because women who are working have relatively higher incomes, and contact with different individuals, this in turn could increase women’s economic independence, access to information and strengthen their autonomy in making health care decisions for their children [66]. The prevalence of seeking healthcare for symptoms of ARIs of children under age five among mothers from the community with high media exposure was higher compared to those who were from the community with low media exposure. This was supported by studies reported in India [65] and West Bengal [67], the possible reason is that health information may improve health-seeking habits through various electronic and print media, such as information about what services are available, where and when to get them, as well as the benefits and risks of accessing specific services.

Strengths and limitations of the study

The study was done based on the weighted Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) data of 36 SSA to ensure representativeness and to obtain reliable estimates. As the study was cross-sectional, we are unable to show a temporal relationship; however, multilevel modeling was employed to consider the clustering effect to obtain reliable estimates and standard errors. Additionally, our multilevel robust Poisson regression corrects the problem of overestimation of effects size produced by conventional multilevel binary logistic regression model employed in cross-sectional studies and increases the precision of the findings. Moreover, all information related to ARIs and healthcare-seeking behavior was provided by mothers and was not validated by applying medical examinations/investigation, and was thus subjective. Therefore, it is prone to recall bias. Furthermore, important variables such as perceived severity, previous experience of similar illness, and previous history of under-five death were not considered in this study as these variables were not available in DHS. The other limitation was the DHS data for all countries were not collected at the same time and the result could mask the changes.

Conclusion

This study found that the prevalence of mothers who sought health care for symptoms of ARIs of children under age five was relatively low in SSA compared to the developed nations. The multilevel analysis found that maternal education, maternal occupation, distance to the health facility, sub-Saharan African region, ANC visits, place of delivery, household wealth status, media exposure, and community media exposure as significant factors associated with a mother's healthcare-seeking behavior for symptoms of ARIs of children under age five. These findings highlighted that public health interventions aimed at enhancing maternal education, media access, and maternal health service utilization need to be implemented to promote mothers' healthcare-seeking behaviour for symptoms of ARIs among children under age five.

Acknowledgements

We greatly acknowledge MEASURE DHS for granting access to the EDHS data sets.

Abbreviations

- APR

Adjusted Prevalence Ratio

- ARIs

Acute Respiratory Infection symptoms

- CI

Confidence Interval

- DHS

Demographic and Health Survey

- ICC

Intra-class Correlation Coefficient

- LLR

Log-likelihood Ratio

- LMICs

Low-and Middle-income Countries

- LR

Likelihood Ratio, MOR; Median Odds Ratio

- SSA

Sub-Saharan Africa

- WHO

World Health Organization

Author’s contributions

BLS and GAT conceived the study. BLS and GAT analyzed the data, drafted the manuscript, and reviewed the article. BLS and GAT extensively reviewed the article. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

No funding was obtained for this study.

Availability of data and materials

Data is available online and you can access it from www.measuredhs.com.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Since the study was a secondary data analysis of publicly available survey data from the MEASURE DHS program, ethical approval and participant consent were not necessary for this particular study. We requested DHS Program and permission was granted to download and use the data for this study from http://www.dhsprogram.com. There are no names of individuals or household addresses in the data files. All the methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. Procedures and questionnaires for standard DHS surveys have been reviewed and approved by ICF Institutional Review Board (IRB). Additionally, country-specific DHS survey protocols are reviewed by the ICF IRB and typically by an IRB in the host country. ICF IRB ensures that the survey complies with the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services regulations for the protection of human subjects, while the host country IRB ensures that the survey complies with laws and norms of the nation. Comprehensive information about the ethical protocols are accessible through https://dhsprogram.com/methodology/Protecting-the-Privacy-of-DHS-Survey-Respondents.cfm.

Consent for publication

Not applicable since the study was a secondary data analysis.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Williams BG, Gouws E, Boschi-Pinto C, Bryce J, Dye C. Estimates of world-wide distribution of child deaths from acute respiratory infections. Lancet Infect Dis. 2002;2(1):25–32. doi: 10.1016/s1473-3099(01)00170-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bellos A, Mulholland K, O'Brien KL, Qazi SA, Gayer M, Checchi F. The burden of acute respiratory infections in crisis-affected populations: a systematic review. Confl Heal. 2010;4(1):1–12. doi: 10.1186/1752-1505-4-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goodarzi E, Sohrabivafa M, Darvishi I, Naemi H, Khazaei Z: Epidemiology of mortality induced by acute respiratory infections in infants and children under the age of 5 years and its relationship with the Human Development Index in Asia: an updated ecological study. J Public Health 2020:1–8.

- 4.Feigin VL, Roth GA, Naghavi M, Parmar P, Krishnamurthi R, Chugh S, Mensah GA, Norrving B, Shiue I, Ng M. Global burden of stroke and risk factors in 188 countries, during 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet Neurol. 2016;15(9):913–924. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(16)30073-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mokdad AH, Forouzanfar MH, Daoud F, Mokdad AA, El Bcheraoui C, Moradi-Lakeh M, Kyu HH, Barber RM, Wagner J, Cercy K. Global burden of diseases, injuries, and risk factors for young people's health during 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet. 2016;387(10036):2383–2401. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00648-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tadesse M, Defar A, Getachew T, Amenu K, Teklie H, Asfaw E, Bekele A, Kebede A, Assefa Y, Demissie T: Countdown to 2015: Ethiopia's progress towards reduction in under-five mortality: 2014 country case study. 2015.

- 7.Cha S. The impact of the worldwide Millennium Development Goals campaign on maternal and under-five child mortality reduction:‘Where did the worldwide campaign work most effectively?’. Glob Health Action. 2017;10(1):1267961. doi: 10.1080/16549716.2017.1267961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rutherford ME, Mulholland K, Hill PC. How access to health care relates to under-five mortality in sub-Saharan Africa: systematic review. Tropical Med Int Health. 2010;15(5):508–519. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2010.02497.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cashat-Cruz M, Morales-Aguirre JJ, Mendoza-Azpiri M: Respiratory tract infections in children in developing countries. In: Seminars in pediatric infectious diseases: 2005: Elsevier; 2005: 84–92. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.McKee MD, Mills L, Mainous AG. Antibiotic use for treatment of upper respiratory infections in a diverse community. J Fam Pract. 1999;48(12):993–993. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zoorob R, Sidani MA, Fremont RD, Kihlberg C. Antibiotic use in acute upper respiratory tract infections. Am Fam Physician. 2012;86(9):817–822. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kassile T, Lokina R, Mujinja P, Mmbando BP. Determinants of delay in care seeking among children under five with fever in Dodoma region, central Tanzania: a cross-sectional study. Malar J. 2014;13(1):1–10. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-13-348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mbagaya GM, Odhiambo MO. Mother's health seeking behaviour during child illness in a rural western Kenya community. Afr Health Sci. 2005;5(4):322–327. doi: 10.5555/afhs.2005.5.4.322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Noordam AC, Carvajal-Velez L, Sharkey AB, Young M, Cals JW. Care seeking behaviour for children with suspected pneumonia in countries in sub-Saharan Africa with high pneumonia mortality. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(2):e0117919. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0117919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Geldsetzer P, Williams TC, Kirolos A, Mitchell S, Ratcliffe LA, Kohli-Lynch MK, Bischoff EJL, Cameron S, Campbell H. The recognition of and care seeking behaviour for childhood illness in developing countries: a systematic review. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(4):e93427. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0093427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Winch PJ, Leban K, Casazza L, Walker L, Pearcy K. An implementation framework for household and community integrated management of childhood illness. Health Policy Plan. 2002;17(4):345–353. doi: 10.1093/heapol/17.4.345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gera T, Shah D, Garner P, Richardson M, Sachdev HS: Integrated management of childhood illness (IMCI) strategy for children under five. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016(6). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Anwar-ul-Haq HMD, Kumar R, Durrani SM. Recognizing the danger signs and health seeking behaviour of mothers in childhood illness in Karachi. Pakistan Univ J Public Health. 2015;3:49–54. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sultana M, Sarker AR, Sheikh N, Akram R, Ali N, Mahumud RA, Alam NH. Prevalence, determinants and health care-seeking behavior of childhood acute respiratory tract infections in Bangladesh. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(1):e0210433. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0210433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sreeramareddy CT, Shankar RP, Sreekumaran BV, Subba SH, Joshi HS, Ramachandran U. Care seeking behaviour for childhood illness-a questionnaire survey in western Nepal. BMC Int Health Hum Rights. 2006;6(1):1–10. doi: 10.1186/1472-698X-6-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abdulraheem I, Parakoyi D. Factors affecting mothers’ healthcare-seeking behaviour for childhood illnesses in a rural Nigerian setting. Early Child Dev Care. 2009;179(5):671–683. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Akinyemi JO, Banda P, De Wet N, Akosile AE, Odimegwu CO. Household relationships and healthcare seeking behaviour for common childhood illnesses in sub-Saharan Africa: a cross-national mixed effects analysis. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19(1):1–11. doi: 10.1186/s12913-019-4142-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sigdel D, Onta M, Bista AP, Sharma K. Factors affecting health seeking behaviors for common childhood illnesses among rural mothers in Chitwan. Int J Health Sci Res. 2018;8(11):177–184. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tiwari G, Thakur AK, Pokhrel S, Tiwari G, Pahari DP. Health care seeking behavior for common childhood illnesses in Birendranagar municipality, Surkhet, Nepal: 2018. PLoS ONE. 2022;17(3):e0264676. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0264676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Burton DC, Flannery B, Onyango B, Larson C, Alaii J, Zhang X, Hamel MJ, Breiman RF, Feikin DR. Healthcare-seeking behaviour for common infectious disease-related illnesses in rural Kenya: a community-based house-to-house survey. J Health Popul Nutr. 2011;29(1):61. doi: 10.3329/jhpn.v29i1.7567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sakisaka K, Jimba M, Hanada K. Changing poor mothers' care-seeking behaviors in response to childhood illness: findings from a cross-sectional study in Granada, Nicaragua. BMC Int Health Hum Rights. 2010;10(1):1–11. doi: 10.1186/1472-698X-10-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Abegaz NT, Berhe H, Gebretekle GB. Mothers/caregivers healthcare seeking behavior towards childhood illness in selected health centers in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: a facility-based cross-sectional study. BMC Pediatr. 2019;19(1):1–9. doi: 10.1186/s12887-019-1588-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Apuleni G, Jacobs C, Musonda P: Predictors of health seeking behaviours for common childhood illnesses in poor resource settings in Zambia, a community cross sectional study. Front Public Health 2021;9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Taffa N, Chepngeno G. Determinants of health care seeking for childhood illnesses in Nairobi slums. Tropical Med Int Health. 2005;10(3):240–245. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2004.01381.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goldman N, Heuveline P. Health-seeking behaviour for child illness in Guatemala. Tropical Med Int Health. 2000;5(2):145–155. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.2000.00527.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Geda NR, Feng CX, Whiting SJ, Lepnurm R, Henry CJ, Janzen B. Disparities in mothers’ healthcare seeking behavior for common childhood morbidities in Ethiopia: based on nationally representative data. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021;21(1):1–11. doi: 10.1186/s12913-021-06704-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.de Souza AT, Peterson K, Andrade F, Gardner J, Ascherio A. Circumstances of post-neonatal deaths in Ceara, Northeast Brazil: mothers’ health care-seeking behaviors during their infants’ fatal illness. Soc Sci Med. 2000;51(11):1675–1693. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00100-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ng'ambi W, Mangal T, Phillips A, Colbourn T, Mfutso-Bengo J, Revill P, Hallett TB. Factors associated with healthcare seeking behaviour for children in Malawi: 2016. Tropical Med Int Health. 2020;25(12):1486–1495. doi: 10.1111/tmi.13499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yaya S, Bishwajit G. Trends in the prevalence and care-seeking behaviour for acute respiratory infections among Ugandan infants. Global Health Res Policy. 2019;4(1):1–10. doi: 10.1186/s41256-019-0100-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Timkete M: Factors affecting healthcare-seeking for children below five years with symptoms of acute respiratory tract infection in Ethiopia: a Cross-sectional study based on the 2016 Demographic and Health Survey. In.; 2018.

- 36.Stryhn H, Sanchez J, Morley P, Booker C, Dohoo I: Interpretation of variance parameters in multilevel Poisson regression models. In: Proceedings of the 11th International Symposium on Veterinary Epidemiology and Economics: 2006; 2006.

- 37.https://dhsprogram.com/data/. In.

- 38.Rutstein SO, Rojas G: Guide to DHS statistics. Calverton, MD: ORC Macro 2006, 38.

- 39.Macro I: Measure DHS. Data downloaded. 2011. from. http://www.measuredhs.com.

- 40.Graham NM, Douglas RM, Ryan P. Stress and acute respiratory infection. Am J Epidemiol. 1986;124(3):389–401. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rodriguez G, Elo I. Intra-class correlation in random-effects models for binary data. Stand Genomic Sci. 2003;3(1):32–46. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Merlo J, Chaix B, Ohlsson H, Beckman A, Johnell K, Hjerpe P, Råstam L, Larsen K. A brief conceptual tutorial of multilevel analysis in social epidemiology: using measures of clustering in multilevel logistic regression to investigate contextual phenomena. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2006;60(4):290–297. doi: 10.1136/jech.2004.029454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Reñosa MDC, Tan AG, Kamigaki T, Tamaki R, Landicho JM, Alday PP, Tallo VL, Oshitani H. Health-seeking practices of caregivers and determinants in responding to acute respiratory infection episodes in Biliran Island Philippines. J Global Health Rep. 2020;4:e2020014. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kasongo ANW, Mukuku O, Gray A, Kanteng W. Shongo MY-P, Mutombo AK, Tambwe AM-A-N, Ngwej DT, Wembonyama SO, Luboya ON: Maternal knowledge and practices regarding childhood acute respiratory infections in Lubumbashi, Democratic Republic of Congo. Theory Clin Pract Pediatr. 2020;2:44–51. [Google Scholar]

- 45.De Allegri M, Sauerborn R, Kouyaté B, Flessa S. Community health insurance in sub-Saharan Africa: what operational difficulties hamper its successful development? Tropical Med Int Health. 2009;14(5):586–596. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2009.02262.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shaikh BT, Hatcher J. Health seeking behaviour and health service utilization in Pakistan: challenging the policy makers. J Public Health. 2005;27(1):49–54. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdh207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Aftab W, Shipton L, Rabbani F, Sangrasi K, Perveen S, Zahidie A, Naeem I, Qazi S. Exploring health care seeking knowledge, perceptions and practices for childhood diarrhea and pneumonia and their context in a rural Pakistani community. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):1–10. doi: 10.1186/s12913-018-2845-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Montagu D. Franchising of health services in low-income countries. Health Policy Plan. 2002;17(2):121–130. doi: 10.1093/heapol/17.2.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bhandari D, Yadav NK. Developing an integrated emergency medical services in a low-income country like Nepal: a concept paper. Int J Emerg Med. 2020;13(1):1–5. doi: 10.1186/s12245-020-0268-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Danquah L, Amegbor PM, Ayele DG. Determinants of the type of health care sought for symptoms of Acute respiratory infection in children: analysis of Ghana demographic and health surveys. BMC Pediatr. 2021;21(1):1–14. doi: 10.1186/s12887-021-02990-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dev R, Williams-Nguyen J, Adhikari S, Dev U, Deo S, Hillan E. Impact of maternal decision-making autonomy and self-reliance in accessing health care on childhood diarrhea and acute respiratory tract infections in Nepal. Public Health. 2021;198:89–95. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2021.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Woldemicael G, Tenkorang EY. Women’s autonomy and maternal health-seeking behavior in Ethiopia. Matern Child Health J. 2010;14(6):988–998. doi: 10.1007/s10995-009-0535-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mekonnen Y, Mekonnen A: Factors influencing the use of maternal healthcare services in Ethiopia. J Health Popul Nutr 2003:374–382. [PubMed]

- 54.Ahmed S, Creanga AA, Gillespie DG, Tsui AO. Economic status, education and empowerment: implications for maternal health service utilization in developing countries. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(6):e11190. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Titaley CR, Que BJ, de Lima FV, Angkejaya OW, de Lima FV, Maelissa MM, Latuconsina VZ, Taihuttu YM, van Afflen Z, Radjabaycolle JE. Health care–seeking behavior of children with acute respiratory infections symptoms: analysis of the 2012 and 2017 Indonesia Demographic and Health Surveys. Asia Pacific Journal of Public Health. 2020;32(6–7):310–319. doi: 10.1177/1010539520944716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Amin R, Shah NM, Becker S. Socioeconomic factors differentiating maternal and child health-seeking behavior in rural Bangladesh: A cross-sectional analysis. International journal for equity in health. 2010;9(1):1–11. doi: 10.1186/1475-9276-9-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Abd-el Rahman N, Mohamed M. Effects of national television immunization campaigns on changing mothers attitude and behaviour in Egypt. Institute of Education: University of London; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Flora JA, Maibach EW, Maccoby N. The role of media across four levels of health promotion intervention. Annu Rev Public Health. 1989;10(1):181–201. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pu.10.050189.001145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Molla G, Gonie A, Belachew T, Admasu B. Health Care Seeking Behaviour on Neonatal Danger Signs among Mothers in Tenta District, Northeast Ethiopia: Community based cross-sectional study. Int J Nurs Midwifery. 2017;9(7):85–93. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Berhane M, Yimam H, Jibat N, Zewdu M: Parents’ knowledge of danger signs and health seeking behavior in newborn and young infant illness in Tiro Afeta district, Southwest Ethiopia: A community-based study. Ethiopian J Health Sci 2018;28(4). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 61.Ndungu EW, Okwara FN, Oyore JP. Cross sectional survey of care seeking for acute respiratory illness in children under 5 years in rural Kenya. Am J Pediatr. 2018;4(3):69–79. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Feikin DR, Nguyen LM, Adazu K, Ombok M, Audi A, Slutsker L, Lindblade KA. The impact of distance of residence from a peripheral health facility on pediatric health utilisation in rural western Kenya. Tropical Med Int Health. 2009;14(1):54–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2008.02193.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Scott K, McMahon S, Yumkella F, Diaz T, George A. Navigating multiple options and social relationships in plural health systems: a qualitative study exploring healthcare seeking for sick children in Sierra Leone. Health Policy Plan. 2014;29(3):292–301. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czt016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Keter PKK: Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices of Mothers in relation to Childhood Pneumonia and factors associated with Pneumonia and Seeking Health Care in Kapsabet District Hospital in Nandi County, Kenya. JKUAT; 2015.

- 65.Chandwani H, Pandor J. Healthcare-seeking behaviors of mothers regarding their children in a tribal community of Gujarat, India. Electron Physician. 2015;7(1):990. doi: 10.14661/2015.990-997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chakrabarti S, Biswas CS. An exploratory analysis of women's empowerment in India: a structural equation modelling approach. J Dev Stud. 2012;48(1):164–180. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ghosh N, Chakrabarti I, Chakraborty M, Biswas R: Factors affecting the healthcare-seeking behavior of mothers regarding their children in a rural community of Darjeeling district, West Bengal. Int J Med Public Health 2013, 3(1).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data is available online and you can access it from www.measuredhs.com.