Abstract

Objective:

We aimed to identify the individual, interpersonal, community, health-system, and structural factors that influence HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) initiation among cisgender women seeking sexual and reproductive health care in a high HIV prevalence community to inform future clinic-based PrEP interventions.

Methods:

We collected anonymous, tablet-based questionnaires from a convenience sample of cisgender women in family planning and sexual health clinics in the District of Columbia. The survey utilized the lens of the socio-ecological model to measure individual, interpersonal, community, institutional, and structural factors surrounding intention to initiate PrEP. The survey queried demographics, behavioral exposure to HIV, perceived risk of HIV acquisition, a priori awareness of PrEP, intention to initiate PrEP, and factors influencing intention to initiate PrEP.

Results:

1437 cisgender women completed the survey. By socio-ecological level, intention to initiate PrEP was associated with positive attitudes towards PrEP (OR 1.56, 95% CI 1.13, 2.15) and higher self-efficacy (OR 1.32, 95% CI 1.02, 1.72) on the individual level, perceived future utilization of PrEP among peers and low fear of shame/stigma (OR 1.65, 95% CI 1.33, 2.04) on the community level, and having discussed PrEP with a provider (OR 2.39, 95% CI 1.20, 4.75) on the institutional level.

Conclusion:

Our findings highlight the importance of multi-level clinic-based interventions for cisgender women which promote sex-positive and preventive PrEP messaging, peer navigation to destigmatize PrEP, and education and support for women’s health medical providers in the provision of PrEP services for cisgender women.

Keywords: Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis, Female, HIV infections, Surveys and Questionnaires, Socio-ecological Model, Reasoned Action Approach

Introduction

Despite the demonstrated safety and efficacy of daily oral pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) with tenofovir disoproxil fumarate/emtricitabine (TDF/FTC)(Baeten et al., 2012; Murnane et al., 2013; Thigpen et al., 2012), there remains a substantial unmet need for HIV prevention among cisgender women and low engagement and retention in the PrEP cascade (AIDSVu, n.d.; Bush et al., 2015, 2016; Marcus et al., 2016; Siegler et al., 2018; Smith et al., 2018; Wu et al., 2017). Current literature suggests multiple patient, provider, and system level barriers to equitable and successful provision and utilization of PrEP. Patient-level barriers include lack of awareness of PrEP (Auerbach et al., 2015; Bogorodskaya et al., 2020; E. Bradley et al., 2019; Collier et al., 2017; Flash et al., 2017; Goparaju et al., 2015; Hill et al., 2020), low perceived risk of HIV acquisition (Auerbach et al., 2015; Bogorodskaya et al., 2020; E. Bradley et al., 2019; Collier et al., 2017; Flash et al., 2017; Goparaju et al., 2015; Hill et al., 2020; Hirschhorn et al., 2020; Hull, 2012; Koren et al., 2018; Kwakwa et al., 2016; Nydegger et al., 2020; Ojikutu et al., 2018), mistrust in the medical establishment (Dale, 2020; D’Angelo et al., 2021; Ojikutu et al., 2020; Tekeste et al., 2019), concern for side effects (Amico et al., 2019; Blumenthal et al., 2021; Goparaju et al., 2015; Hill et al., 2020; JD Auerbach, 2015; Koren et al., 2018), and stigma (Auerbach et al., 2015; E. Bradley et al., 2019; Calabrese et al., 2018; Felsher et al., 2020; Goparaju et al., 2017; Pinto et al., 2018; Rubtsova et al., 2014; Smith et al., 2012). Additionally low provider knowledge and comfort prescribing PrEP (Aaron et al., 2018; Blackstock et al., 2017; E. Bradley et al., 2019; Castel et al., 2015; Krakower & Mayer, 2016; Petroll et al., 2017; Pinto et al., 2018), racial biases around PrEP prescribing (Hull et al., 2021), and issues of accessibility and availability of PrEP services (Aaron et al., 2018; Bradley & Hoover, 2019; Siegler et al., 2018) serve as significant barriers to PrEP use for cisgender women.

The District of Columbia (DC) is a CDC-designated HIV “hotspot” with a population HIV prevalence of 1.7%; HIV prevalence is 1.2 % among all cisgender women and 1.7% among Black cisgender women (Bowser et al., 2022). The DC Department of Health (DC Health) estimates that fewer than 10% of residents with risk factors for HIV acquisition utilize PrEP, illustrating significant local unmet need (Bowser et al., 2022). In response to this underutilization of PrEP among cisgender women in the District of Columbia, we designed this study using both the Socio-Ecological Model (SEM)(Bronfenbrenner, 1979) and the Reasoned Action Approach (RAA)(Ajzen, 2011; Ajzen et al., 2012; Fishbein & Ajzen, 2011) as theoretical frameworks to understand intention to initiate PrEP among cisgender women in the high prevalence area of the District of Columbia. We conducted surveys among cisgender women seeking care at a family planning clinic within a large tertiary care medical center and a government-sponsored sexual health clinic, both of which offer universal PrEP screening and same-day PrEP initiation but evidenced low levels of PrEP uptake among cisgender women. Both sites serve predominantly Black, underserved patient populations. Our primary objective was to identify the individual, interpersonal, community, health-system, and structural factors that influence PrEP initiation in order to build interventions to improve engagement and retention in the PrEP cascade for cisgender women.

Methods and Measures

Study Design

We collected anonymous, tablet-based questionnaires from a convenience sample of cisgender women ≥ 18 years of age seeking care at a Department of Health-run sexual health clinic or a family planning and preventive care clinic within a tertiary care medical center in the District of Columbia. We included participants at all stages of the PrEP cascade in order to capture associations between RAA global measures/SEM factors and behavioral intention. We obtained IRB approval from both sites prior to data collection (IRB#s 2017–0870 and 2017–25). We collected questionnaires in the family planning clinic as part of a small-scale implementation and feasibility study from September 2017 to March 2018 and at both sites from July 2018 until March 2020.

In both waiting rooms, informational videos played on a loop and included the five-minute video “What is PrEP?” (www.whatisprep.org) along with other videos reviewing sexual health, contraception, and HIV prevention. The widely circulated, gender-inclusive video describes what oral PrEP is, how it works, how it is used, and PrEP eligibility criteria (Amico, et al. 2014). Study coordinators approached all women by describing the purpose of the study (script available upon request) in the waiting rooms of the two sites and all English-speaking women age 18 and older were invited to participate. The questionnaire screened sex assigned at birth and gender identity. Participants watched the “What is PrEP?” video on the waiting room television or on a tablet, then completed the informed consent and questionnaire on a tablet in an exam room while waiting for their medical provider. The questionnaire queried demographics, behavioral exposure to HIV, perceived risk of HIV acquisition, a priori awareness of PrEP, intention to initiate PrEP, prior receipt of a prescription for PrEP, and multi-level factors influencing intention to initiate PrEP. The questionnaire took approximately 25 minutes to complete and participants were compensated with a $5 gift card upon completion.

Universal PrEP screening and education by providers were standard of care in both clinics; patients who voiced interest in PrEP received counseling and laboratory screening by their medical provider, and depending on site protocol, were given a one-week supply or prescription for one month of oral TDF/FTC and scheduled for clinical follow-up.

Theoretical Frameworks

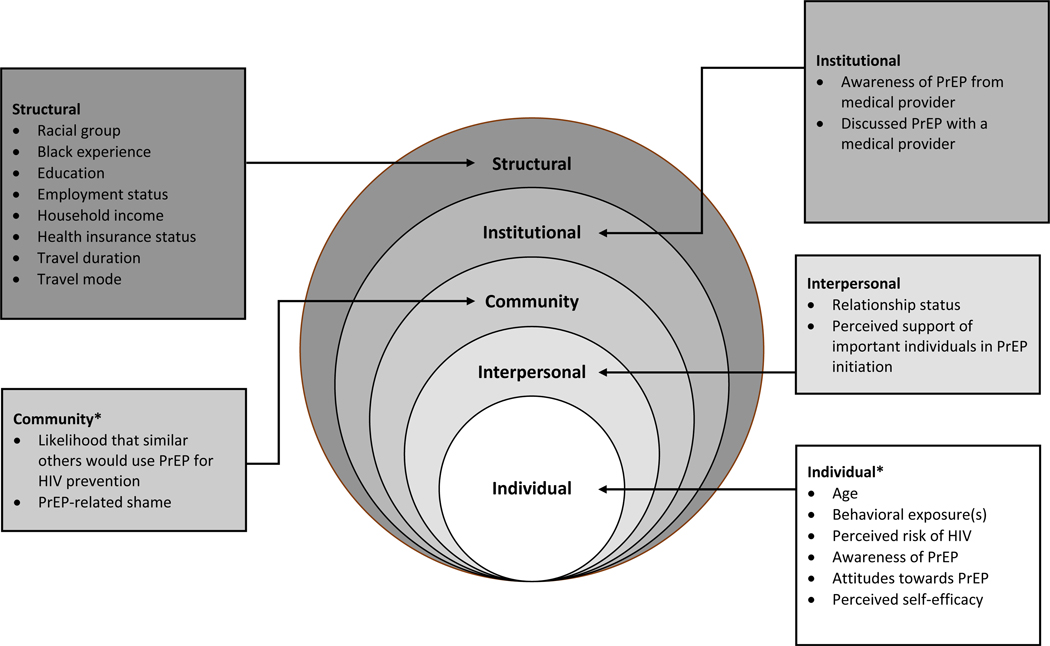

The Socio-Ecological Model (SEM) posits that an individual’s decisions and behaviors result from reciprocal interactions within and between individuals and their social, cultural, and structural environments (Bronfenbrenner, 1979). Specifically, the SEM highlights that although health decisions or behaviors occur at the individual level, they are influenced by individual (i.e., psychological), interpersonal (e.g., relationship power, relationship commitment), community (i.e., cultural norms, stigma), institutional (e.g., equitable provision of care, appropriate services), and structural factors (e.g., public policy, infrastructure) (Kaufman et al., 2014).

We supplement the SEM perspective with the Reasoned Action Approach (RAA), an individual level theory of behavior change and prediction, which is the latest iteration in the Theory of Reasoned Action framework (Yzer 2017). The RAA posits a limited number of psychosocial variables that shape behavioral intentions, which in turn affect behavior (Fishbein & Ajzen, 2011). The RAA posits that the primary predictor of behavior is intention. That is, people will act upon their intentions to the extent that they feel they have the ability, that it is under their control, and that environmental barriers are not excessive. Intentions are determined by attitudes toward performing the behavior, normative pressure and perceptions of behavioral control, or self-efficacy over performing the behavior. Attitudes refer to a sense of favorability with regard to the behavior. Normative perceptions refer to the perception that the behavior is acceptable to important social referents (i.e., injunctive norms) and that similar others engage in the behavior (i.e., descriptive norms). Perceptions of behavioral control (PBC) refer to perceptions of self-efficacy with regard to the behavior. These proximal determinants of behavioral intentions are determined by underlying beliefs. Attitudes are determined by outcome expectations (i.e., performing the behavior will result in specific desirable and undesirable outcomes); normative perceptions are determined by beliefs about whether particular normative referents would approve and the motivation to comply with those referents. PBC is determined by perceptions of ones’ ability to overcome specific barriers that are likely to be present (Fishbein & Ajzen, 2011).

The relative importance of these factors will vary by population and behavior. Other sociodemographic variables, such as perceived risk, relationship status, and education, are considered “background variables,” which are likely to impact behavior indirectly by shaping the beliefs people endorse. The RAA provides an account of the individual-level factors in health behavior and also acknowledges the critical importance of social and structural factors in health by highlighting how actual control may moderate the ability to act on intentions and also impact the beliefs people endorse. This model has been extensively applied across a wide array of behavioral contexts and populations, cross-sectionally and prospectively—including in HIV prevention (Albarracín et al., 2001; Armitage & Conner, 2001; Chittamuru et al., 2020; Godin & Kok, 1996; McEachan et al., 2016; Teitelman et al., 2020).

Measures

We assessed factors identified in our qualitative pilot research (Hull et al., 2017) and others’ formative research (Auerbach et al., 2015; Goparaju et al., 2017; Wingood et al., 2013) using closed-ended questions.

Individual factors included age, behavioral exposures to HIV — injection drug use, multiple sexual partners, non-monogamous sexual partners, transactional sex practices, inconsistent condom use, and history of recent history of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) — perceived risk of HIV acquisition, prior awareness of PrEP, salient outcome expectations (i.e., attitudes) relevant to PrEP (i.e., effectiveness, side effects, cost), and perceived self-efficacy. Interpersonal factors included relationship status and both the perceived support from important individuals in their networks and their motivation to comply with those individuals (injunctive norms), such as their doctor, main sexual partner, best friend, and sister. Community factors included perceived likelihood of peers to use PrEP (i.e., descriptive norms) and anticipated stigma. Institutional factors (i.e., health system) included education and counseling about PrEP from a medical provider or prescription of PrEP by a medical provider. Structural factors included racial group, educational and income levels, employment status, medical insurance status, transportation, and length of time to travel to the clinic site. Of note, transportation and duration of travel were not included in the pilot questionnaire and were added to the revised questionnaire in July 2018.

We measured behavioral intention to initiate PrEP by asking: “Which statement best reflects your thinking?” with response choices of “I have no intention of using PrEP for HIV prevention in the next 12 months,” “I am considering taking PrEP for HIV prevention in the next 12 months, but I’m not ready to take action,” “I am committed to taking PrEP for HIV prevention in the next 12 months,” and “I am ready to start PrEP as soon as possible.” We then collapsed responses into a dichotomous variable reflecting intention (i.e., “committed” and “ready to start” vs. “no intention” and “considering”). Theoretical constructs were assessed using 5-point Likert scales (strongly disagree to strongly agree), except for injunctive normative beliefs, which were calculated by multiplying beliefs about whether specific important individuals (i.e., normative referents identified through our previous research; [Hull et al. 2022]) would support PrEP uptake (definitively would not support to definitely would support, range −2 to 2) by reported rating of the motivation to comply with that referent (Bleakley & Hennessey, 2012, Bleakley & Hull, in press). To assess motivation to comply, we asked respondents how important each referent’s opinion was in her decision whether to use PrEP (i.e., not important at all to extremely important, range 1–5); the range for the normative belief variables is ±10.

Data Analysis

We used descriptive statistics to characterize the study sample, including age, racial group, marital status, education level, employment status, income level, and insurance type. To determine association of potential facilitators and barriers by socio-ecological level with intention to initiate PrEP, we divided the study sample based on the dichotomous PrEP intention status and tested associations with individual, interpersonal, community, institutional, and structural factors using Fisher’s exact test, Mann-Whitney U test, and Student’s t-test, when appropriate. We used Cochran-Armitage trend test to detect the trends in intention with increases in education and income levels. Lastly, we performed a binomial logistic regression analysis of RAA measures (attitudes, injunctive norms, descriptive norms, and self-efficacy) on intention to initiate PrEP, adjusting for significant socio-demographics, risk behaviors, and psychosocial factors identified from the bivariate analysis. We estimated an adjusted odds ratio with 95% confidence interval for each potential factor. The significance level was set at 0.05 throughout the study. All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

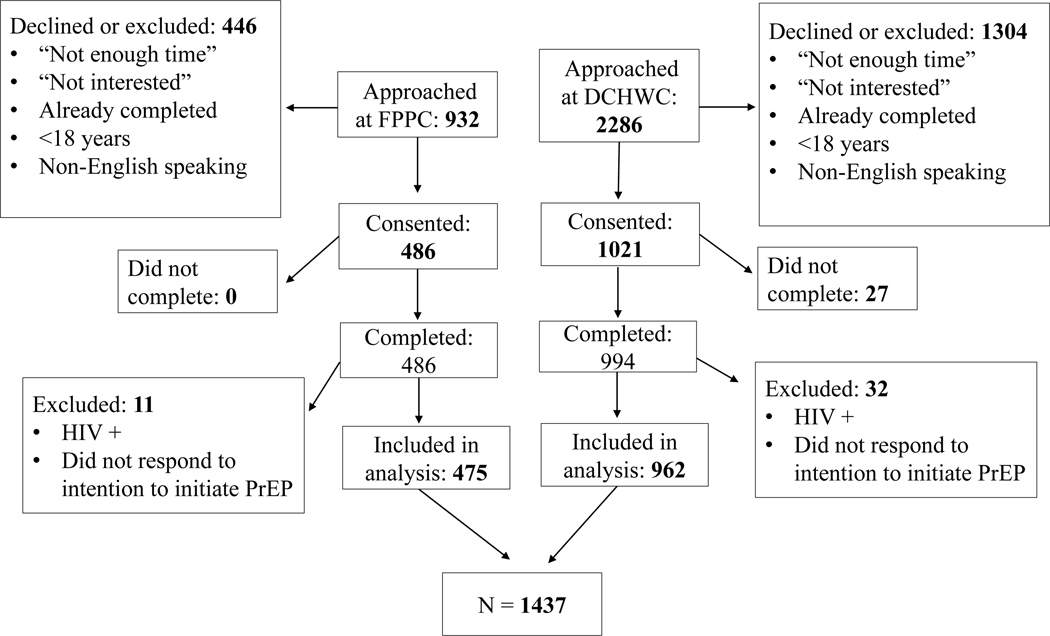

A total of 1480 participants completed the questionnaire. We excluded 43 respondents (10 who reported HIV positive status and 33 who did not respond regarding their intention to start PrEP); a total of 1437 total questionnaire responses were included in the final analysis (Table 1).

Table 1.

Bivariate analysis of determinants of intention to initiate PrEP by socio-ecological level

| Variables | Total (N=1437) | No intention to initiate PrEP (n= 1289) | Intention to Initiate PrEP (n=148) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. Individual | ||||

| Age | 28.8±9.2 | 28.7±9.2 | 30.1±9.9 | 0.08 |

| Behavioral exposure | ||||

| Injection Drug Use (lifetime; no/yes) | 64(4.5) | 51(4.0) | 13(8.8) | 0.02 |

| Inconsistent Condom Use (never, rarely, or sometimes vs. always) | 1020(71.0) | 915(71.0) | 105(70.9) | >.99 |

| >2 Sex Partners (yes/no) | 426(29.6) | 371(28.8) | 55(37.2) | 0.04 |

| Number of Behavioral Risk Factors – Median (10%, 90%) | 2(0,3) | 2(0,3) | 2(1,4) | <.01 |

| Recent History of STI (past 12 months) | 208(14.5) | 180(14.0) | 28(18.9) | 0.11 |

| Casual Sex Partner(s) (current) | 429(29.9) | 373(28.9) | 56(37.8) | 0.03 |

| Transactional Sex (past 12 months) | 42(2.9) | 33(2.6) | 9(6.1) | 0.03 |

| Perceived Risk (Lifetime) (scale 1– 4) | 1.6±0.7 | 1.6±0.7 | 1.7±0.7 | 0.63 |

| Perceived Risk (Near Future) (scale 1– 4) | 1.4±0.6 | 1.4±0.6 | 1.4±0.6 | 0.86 |

| Awareness of PrEP | ||||

| Before today, have you ever heard of people who do not have HIV taking PrEP to reduce the risk of getting HIV? (no/yes) | 541(39.0) | 484(38.8) | 57(40.7) | 0.71 |

| Attitudes | ||||

| Overall, would you say that using PrEP daily to prevent HIV is a good or a bad thing? (scale 1– 5) | 4.1±1.0 | 4.0±1.0 | 4.6±0.9 | <.01 |

| Using daily PrEP to prevent HIV would make me feel in control of my health. (scale 1– 5) | 3.8±1.2 | 3.7±1.2 | 4.4±1.1 | <.01 |

| PrEP is a safe way to prevent HIV infection. (scale 1– 5) | 4.0±1.0 | 4.0±1.0 | 4.5±1.0 | <.01 |

| PrEP is an effective tool to prevent HIV infection. (scale 1– 5) | 4.1±1.0 | 4.0±1.0 | 4.4±1.1 | <.01 |

| Perceived Self-Efficacy | ||||

| If I really wanted to, I could use PrEP daily for HIV prevention. (scale 1– 5) | 4.0±1.1 | 3.9±1.2 | 4.5±1.0 | <.01 |

| If I really wanted to, I could remember to take the pill every day. (scale 1– 5) | 4.0±1.2 | 3.9±1.2 | 4.4±1.1 | <.01 |

| If I really wanted to, I could take the pill every day, even if it gave me a stomachache. (scale 1– 5) | 3.0±1.4 | 2.9±1.3 | 4.0±1.3 | <.01 |

| I could use PrEP for HIV prevention, even if my main partner didn’t want me to. (scale 1– 5) | 4.1±1.1 | 4.1±1.1 | 4.5±1.1 | <.01 |

| I just can’t take pills. | 2.0±1.3 | 2.0±1.3 | 1.7±1.2 | <.01 |

| B. Interpersonal | ||||

| Relationship Status | 0.68 | |||

| Married or Living Together | 190(13.3) | 171(13.3) | 19(13.0) | |

| Divorced, Separated, or Widowed | 84(5.9) | 78(6.1) | 6(4.1) | |

| Single or Never Married | 1157(80.9) | 1036(80.6) | 121(82.9) | |

| Norms | ||||

| Thinking about the people who are important to you — would they support or not support your using PrEP for HIV prevention in the next 12 months? (scale 1–5) | 3.9±1.2 | 3.8±1.2 | 4.4±0.9 | <.01 |

| Top Five Important People (±10) | ||||

| Doctor | 6.6±4.2 | 6.3±4.2 | 8.4±3.1 | <.01 |

| Main Sex Partner | 5.2±4.9 | 4.9±4.9 | 7.7±3.5 | <.01 |

| Child | 4.7±4.9 | 4.5±4.9 | 6.4±4.4 | <.01 |

| Best Friend | 4.6±4.5 | 4.3±4.4 | 6.8±3.8 | <.01 |

| Sister | 4.4±4.7 | 4.2±4.7 | 6.6±4.2 | <.01 |

| C. Community | ||||

| Thinking about people who are similar to you — how likely would they be to use PrEP for HIV prevention in the next 12 months? (scale 1– 5) | 3.2±1.2 | 3.1±1.2 | 4.1±1.1 | <.01 |

| People would shame me if they learned that I was taking PrEP. (scale 1– 5) | 2.0±1.1 | 1.8±1.2 | <.01 | |

| D. Health System | ||||

| Heard about PrEP from a doctor1 | 148(27.4) | 121(25.0) | 27(47.4) | <.01 |

| In the past 12 months, have you had a discussion with a healthcare provider about taking PrEP?1 | 120(22.3) | 93(19.3) | 27(48.2) | <.01 |

| E. Structural | ||||

| Race | 0.03 | |||

| Black / African American | 1050(74.8) | 928(73.8) | 122(84.1) | |

| White / Caucasian | 144(10.3) | 135(10.7) | 9(6.2) | |

| Other / Multiple Races | 209(14.9) | 195(15.5) | 14(9.7) | |

| Black Experience – Black/African American (Yes vs. No) | 1050(74.8) | 928(73.8) | 122(84.1) | <.01 |

| Education | <.01 [.01] | |||

| Less than 12th Grade | 69(4.8) | 56(4.4) | 13(8.8) | |

| 12th Grade or GED | 413(28.8) | 362(28.2) | 51(34.7) | |

| Some college, Associate or Technical Degree | 548(38.3) | 489(38.1) | 59(40.1) | |

| Bachelor’s Degree | 275(19.2) | 260(20.2) | 15(10.2) | |

| Graduate Studies | 127(8.9) | 118(9.2) | 9(6.1) | |

| Employment Status | .10 | |||

| Employed Full-Time | 643(45.6) | 583(46.1) | 60(41.7) | |

| Employed Part-Time | 296(21.0) | 272(21.5) | 24(16.7) | |

| Student | 126(8.9) | 113(8.9) | 13(9.0) | |

| Unemployed, Homemaker, or Retired | 344(24.4) | 297(23.5) | 47(32.6) | |

| Household Income | <.01 [.03] | |||

| 0-$14,999 | 533(41.9) | 472(41.3) | 61(47.3) | |

| $15,000–29,999 | 228(17.9) | 206(18.0) | 22(17.1) | |

| $30,000–49,999 | 301(23.7) | 263(23.0) | 38(29.5) | |

| $50,000 or more | 210(16.5) | 202(17.7) | 8(6.2) | |

| Health insurance status (Insured vs. Uninsured) | 1054(75.5) | 947(75.6) | 107(74.3) | 0.76 |

|

Travel Duration (n=1331) ≤ 15 Minutes 25–29 Minutes 30–44 Minutes 45–59 Minutes ≥60 Minutes |

335(25.2) 577(43.4) 269(20.2) 96(7.2) 54(4.1) |

294(24.6) 520(43.5) 242(20.2) 89(7.4) 51(4.3) |

41(30.4) 57(42.2) 27(20.0) 7(5.2) 3(2.2) |

0.50 [0.07] |

|

Travel Mode (n=1337) Own car Friend or Family Car Bus Metro Bicycle Walk Car-share |

502(37.6) 197(14.7) 107(8.0) 180(13.5) 14(1.1) 60(4.5) 277(20.7) |

452(37.6) 178(14.8) 95(7.9) 161(13.4) 14(1.2) 52(4.3) 250(20.8) |

50(37.0) 19(14.1) 12(8.9) 19(14.1) 0(0) 8(5.9) 27(20.0) |

0.93 |

Note: The P-values within the brackets were based on Cochran-Armitage Trend Test. Others were based on Fisher’s Exact Test.

The mean age of the study population was 28.8 years; the majority of participants were Black (74.8%), single or never married (80.9%), with annual household incomes of less than $30,000 (59.8%). Table 1 reports the sample’s sociodemographic characteristics. The majority of participants reported >1 sexual partner in the past 12 months (50.9%) and inconsistent condom use (71.0%), in addition to living in a high HIV prevalence area. The median number of risk factors for HIV acquisition was 2. Mean perceived risk of HIV was “low.” Sixty-one percent (n=541) of respondents reported being previously unaware of PrEP. Those who were aware of PrEP had most commonly heard of it from their health care provider (27.4%, n=148); among them, 81.1% (n=120) reported a discussion about PrEP with their healthcare provider and 22.3% (n=33) reported receiving a prescription for oral PrEP. Cisgender women ranked the importance of their medical provider’s support most highly, followed by that of their partner. Among all respondents (N=1437),10.3% (n=148: n=72 “committed to starting PrEP,” n=76 “ready to start taking PrEP”) expressed intention to initiate PrEP in the next 12 months; 89.7% (n=638: n=72 “no intention to start PrEP,” n=566 “considering starting PrEP”) did not express readiness. Among the 33 women who reported previous prescription of oral PrEP, the majority (n=20, 74.1%) reported positive intention.

Table 2 reports the results of the multivariable logistic regression to understand the association of intention to initiate PrEP with significant bivariate barriers and facilitators of PrEP intention. To assess multi-collinearity, we estimated the variance inflation factor (VIF) of the explanatory variables in the model and found that the highest VIF = 1.45, indicating that multi-collinearity is not a cause for concern (Senaviratna & Cooray, 2019).

Table 2:

Multivariable logistic regression of intention to initiate PrEP on factors with significant bivariate associations

| Variable | Adjusted Odds Ratio Estimate | 95% Wald Confidence Interval | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Individual-level | |||

|

| |||

| Behavioral Exposure (past 12 months) | |||

| Injection Drug Use (Yes vs. No) | 2.23 | 1.004 | 4.95 |

| Casual Sex Partner (Yes vs. No) | 1.15 | 0.72 | 1.83 |

| >2 Sex Partners (Yes vs. No) | 1.29 | 0.79 | 2.11 |

| Transactional Sex (Yes vs. No) | 2.59 | 1.03 | 6.48 |

|

| |||

| Attitudes (1–5)1 | 1.56 | 1.13 | 2.15 |

|

| |||

| Self-Efficacy (1–5) 1 | 1.32 | 1.02 | 1.72 |

|

| |||

| Interpersonal-level | |||

|

| |||

| Global Injunctive Norm Score (1–5)1 | 1.15 | 0.90 | 1.47 |

|

| |||

| Community-level | |||

|

| |||

| Global Descriptive Norm Score (1–5) 1 | 1.65 | 1.33 | 2.04 |

|

| |||

| Health System-level | |||

|

| |||

| Heard about PrEP from Health Care Provider (Yes vs. No) | 1.28 | 0.64 | 2.53 |

| Discussed Taking PrEP with a Health Care Provider (Yes vs. No) | 2.39 | 1.20 | 4.75 |

|

| |||

| Structural-level | |||

|

| |||

| Race | |||

| White (vs. African American) | 1.04 | 0.45 | 2.45 |

| Other (vs. African American) | 0.79 | 0.40 | 1.56 |

|

| |||

| Education (Years of Schooling) | 0.85 | 0.76 | 0.96 |

|

| |||

| Income Level | |||

| $15k–29k (vs. 0–$14k) | 0.90 | 0.49 | 1.65 |

| $30k–49k (vs. $15k–29k) | 1.63 | 0.87 | 3.07 |

| >= $50k (vs. $30k–49k) | 0.40 | 0.17 | 0.94 |

The estimated odds ratio indicates the odds of behavioral intention to use for every one level increase in the score.

We present our findings by socio-ecological level:

Individual

At the individual level, behavioral exposure such as injection drug use (IDU), transactional sex, casual sex partner(s), and >2 sex partners demonstrated independent bivariate associations with intention to initiate PrEP. Only IDU (aOR 2.23, 95% CI 1.004, 4.95) and transactional sex (aOR 2.59, 95% CI 1.03, 6.48) were significantly correlated with intentions in the multivariable logistic regression model, after controlling for other variables in the model. There were no significant differences by intention in perceived risk of HIV acquisition, prior awareness of PrEP, or knowledge of where to “start the process” in the bivariate analysis. Although attitudes towards PrEP were favorable in both groups, more favorable attitudes towards PrEP were associated with intention to initiate PrEP in both the bivariate and multivariable analysis (aOR 1.56, 95% CI 1.13, 2.15). In the bivariate analysis, beliefs about PrEP safety and efficacy and the belief that “using daily PrEP to prevent HIV would make (cisgender women) feel in control of (their) health” were significantly correlated with intention (Table 1). Self-efficacy was similarly high in both cisgender women with and without intention to initiate PrEP. Still, higher self-efficacy, namely beliefs that cisgender women could be adherent despite side effects or lack of partner support, was associated with intention to initiate PrEP in both bivariate and multivariable analyses (aOR 1.32, 95% CI 1.02, 1.72).

Interpersonal

There was no significant bivariate association between relationship status and intention to initiate PrEP. The perceived support of important individuals with whom they are motivated to comply (injunctive norms), such as main sexual partner, best friend, and sister, were significant in the bivariate analyses. These injunctive normative beliefs were not significant in the multivariable analyses.

Community

Descriptive norms, specifically perceived likelihood of peers to use PrEP and anticipation of being shamed for taking PrEP, were significantly associated with intention to initiate PrEP (positively and negatively, respectively) in both the bivariate and multi-variable analysis (aOR 1.65, 95% CI 1.33, 2.04).

Institutional

Having heard about PrEP from a medical provider was not significantly associated with intentions in the multivariable analysis. Prior discussion with a health care provider about PrEP was significantly associated with intention to initiate PrEP (aOR 2.39, 95% CI 1.20, 4.75) in the multivariable analysis.

Structural

There were significant differences by racial group (p<0.01) such that Black women reported higher intentions to initiate PrEP in the bivariate analysis (n=122, 84.1% vs. n=928, 73.8%, p<0.01); however, these differences were not significant in the multi-variable logistic regression. There were no significant differences in intentions by employment or health insurance status. There were significant associations between intentions and both educational (p<0.01) and income levels (p<0.01). Specifically, cisgender women with household incomes greater than $50,000 were less likely to intend to initiate PrEP. Trend tests indicated that educational and income levels were both inversely associated with intention to initiate PrEP. We did not find associations between mode of transportation or duration of travel to the clinic site and intention to initiate PrEP.

Discussion

Findings in the context of the published literature.

We applied theory to guide the identification of multi-level factors shaping PrEP intentions among cisgender women and found that intention to initiate PrEP was associated with individual, community, and institutional-level socio-ecological factors among our sample of cisgender women seeking reproductive/sexual health care in an urban, high HIV prevalence US setting. Previous research has identified persistent low awareness as a barrier to equitable PrEP diffusion (Aaron et al., 2018; Auerbach, 2015; E. Bradley et al., 2019; Collier et al., 2017; Hill et al., 2020; Hull, 2012; Koren et al., 2018; Kwakwa et al., 2016; Ojikutu et al., 2018; Patel et al., 2019; Wingood et al., 2013). Consistent with this, the majority of cisgender women in this study were unaware of PrEP prior to their participation in this research. This is especially notable given that this research was conducted in a HIV hotspot among a sample of a population that experiences disparately high HIV incidence (Bowser et al., 2022); 9 out of 10 cisgender women who were diagnosed with HIV in the District of Columbia in 2020 were Black, despite Black women representing fewer than half of women in the District. Prior awareness of PrEP was not, however, associated with intention to initiate. Additionally, neither individual perceived risk nor the majority of HIV exposure behaviors that we measured were associated with intention to initiate PrEP. IDU and transactional sex, notably the highest risk behaviors, were the only behavioral exposures associated with intention to initiate PrEP among a minority of study participants. Conversely, on the individual level, both positive, preventive, and empowering perceptions of PrEP (i.e., attitudes) and greater perceived self-efficacy to take daily oral PrEP, even in the face of individual and interpersonal barriers, were associated with intention to initiate PrEP. Although assessed interpersonal level factors were not significant, on the community level, cisgender women who perceived higher acceptance of PrEP (i.e., higher likelihood of PrEP use among peers and lower concern for shame/stigma related to PrEP) were more likely to intend to initiate PrEP. On the level of the institution, our findings corroborate earlier publications reporting the importance of the role of the medical provider in cisgender women’s intention to initiate PrEP (Aaron et al., 2018; Flash et al., 2017; Goparaju et al., 2017; Wingood et al., 2013). Finally, on the structural level, we did not find lower socioeconomic status nor insurance status to be barriers to intention to initiate PrEP; rather, we found that cisgender women with lower educational and income levels were more likely to intend to initiate PrEP.

Implications for Practice.

Given our findings, we integrate widely accepted psychosocial behavior change theorizing into an ecological model to gain insight into potential avenues for intervention to promote PrEP use in a population that is systematically underserved by PrEP (Siegler et al., 2018). Given significant findings on multiple socio-ecological levels, we accordingly advocate for multi-level interventions to improve engagement and retention in the PrEP cascade among cisgender women. On the individual and community level, our findings echo those of Teitelman et. al. (2020) and indicate the importance of interventions not only focused on increasing awareness of PrEP among cisgender women, but specifically on messaging that emphasizes positive and preventive messaging around PrEP and both normalizes PrEP use and destigmatizes PrEP use for cisgender women. Although there is scant research on PrEP messaging among cisgender women, research among men who have sex with men (MSM) and transgender women empirically supports sex positive, preventive social marketing campaigns (Phillips et al., 2020). Additionally, as prior awareness of PrEP was not associated with intention to initiate PrEP, we hypothesize that raising awareness alone will not be sufficient to increase engagement in the PrEP cascade among this population. Beyond messaging, we advocate for integrated peer navigation as part of a multi-disciplinary approach to further address stigma by normalizing PrEP use and to bolster self-efficacy through PrEP counseling and peer support (Hull et al., 2022; Teitelman et al., 2021).

On the institutional level, our findings underscore the critically underutilized role of medical providers in HIV prevention and PrEP education, promotion, and provision for cisgender women (Aaron et al., 2018; Krakower & Mayer, 2016). As in the published literature, cisgender women identify provider support as both influential and logistically key to PrEP initiation (Aaron et al., 2018; Flash et al., 2017; Goparaju et al., 2017; Hull et al, 2022; Roth et al., 2019; Scott et al., 2020; Wingood et al., 2013). Notably, however, having been introduced to PrEP by a medical provider was not significantly associated with intention to initiate PrEP, yet discussion of PrEP with a provider was significantly associated. This finding highlights the critical importance for cisgender women of shared decision-making about PrEP with healthcare providers. It is insufficient that providers simply make women aware of PrEP (e.g., with posters, flyers, and pamphlets); raising awareness is necessary, but inadequate to increase utilization. Evidence from this study suggests that the discussion about PrEP, likely in relation to one’s own sexual health situation, carries a great deal of influence in cisgender women’s decision to use PrEP. Provider knowledge of and comfort with prescribing PrEP continues to lag across specialties (Blackstock et al., 2017; E. Bradley et al., 2019; Castel et al., 2015; Petroll et al., 2017), as echoed in a national survey of family planning providers (Seidman et al., 2016).

Despite the synergy of offering integrated PrEP services to reproductive-age cisgender women as part of sexual and reproductive health care services (Aaron et al., 2018; E. L. P. Bradley & Hoover, 2019; Seidman et al., 2018), most sexual and reproductive health clinics do not routinely counsel or offer PrEP (Sales et al., 2019). In addition to the barrier of low provider knowledge of PrEP, providers’ implicit and explicit biases disadvantage cisgender women, as well as people of color and those who use substances or have low incomes, in the equitable provision of PrEP (Adams & Balderson, 2016; Calabrese et al., 2014). Research among providers in U.S. HIV hotspots demonstrated implicit racial biases in the prescription of PrEP to cisgender women; specifically, in clinical vignettes providers were less likely to prescribe PrEP to Black cisgender compared to White women due to concerns for low adherence (Hull et al., 2021). Given the importance of providers in PrEP initiation indicated by cisgender women and recognizing continued provider-level barriers, the authors suggest that clinical interventions to improve engagement in the PrEP cascade should widen their focus to include providers, including tailored educational interventions and toolkits to address knowledge deficits and enable equitable provision of PrEP. Lastly, we did not find the structural barriers we anticipated, perhaps because of the availability and accessibility of PrEP in the select clinical settings where the research took place. In settings with less PrEP accessibility, trained peer navigators could address structural barriers in addition to social barriers.

Limitations.

Our questionnaire focused on intention to initiate rather than initiation and as questionnaires were anonymous, we are unable to correlate the socio-ecological factors associated with PrEP intention with actual PrEP uptake. This said, behavioral intention has been demonstrated to significantly correlate with behaviors in a wide range of behavioral domains (Sheeran, 2002). We acknowledge, however, that interpersonal and structural factors, which were not significant factors in intention to initiate PrEP, may become more pertinent in the actualization of PrEP initiation (i.e., moderate the intention-behavior relationship). This study was conducted in an HIV hotspot with Medicaid expansion, which facilitates the availability of free, same-day PrEP prescription. The results of this study are therefore limited in the extent to which they may be generalizable to settings with low access and availability of PrEP and where insurance coverage is relatively low. We anticipate that in settings with less PrEP accessibility, the determinants of intentions may vary. We also note that we did not adjust for multiple comparisons in the analysis.

Conclusions

The results of this study support the importance of multi-level clinic-based interventions for cisgender women that center on sex-positive and preventive messaging around PrEP, include peer navigation in the destigmatization of PrEP, and provide education and support to women’s health providers to aid in the provision of PrEP.

Figure 1.

Study Flow

Figure 2.

Socio-ecological Model

*Variables at these levels were derived using the Reasoned Action Approach

Role of the Funding Source:

Data reported in this publication was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number UL1TR001409, National Institute on Drug Abuse under Award Number 1K01DA050496–01A1a, and an Investigator Sponsored Research Award from Gilead Sciences (ISR-17–10227). The funders had no role in the study design, collection, analysis, or interpretation of data, in the writing of the report or the decision to submit the article for publication. Drs. Rachel Scott, Shawnika Hull, and Jim Huang had full access to all the data and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the analysis.

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Author Biography

Rachel K. Scott is a practicing obstetrician gynecologist at MedStar Health with a clinical and research focus on HIV and HIV prevention among women

Shawnika J. Hull is an assistant professor of communications at Rutgers University with a research focus on health communication and HIV prevention among women

Jim C. Huang is an assistant professor at National Sun Yat-sen University with a research focus on Health economics and outcomes research.

Peggy Ye is a practicing obstetrician gynecologist at MedStar Washington Hospital Center with a research and clinical focus on Family Planning.

Pam Lotke is a practicing obstetrician gynecologist at MedStar Washington Hospital Center with a research and clinical focus on Family Planning.

Jason Beverley is the STD/TB Control Division Chief at the D.C. Department of Health with expertise in HIV and HIV prevention.

Patricia Moriarty is a research manager at MedStar Health with a research concentration in Women’s Health and HIV.

Dhikshitha Balaji is a medical student at Case Western.

Allison Ward is a resident at MedStar Health completing her obstetrics and gynecology residency.

Jennifer Holiday is a research intern at MedStar Health, currently completing her obstetrics and gynecology residency.

Ashley R. Brant is a practicing obstetrician gynecologist at Cleveland Clinic with a clinical and research focus in family planning.

Rick Elion is a family physician associated with the D.C. Department of Health with expertise in HIV and HIV prevention.

Adam Visconti is a family physician at Medstar Health with clinical and research expertise in HIV and HIV prevention

Megan Coleman is a nurse practitioner and implementation specialist with expertise in HIV and HIV prevention working with US AID

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: RKS receives investigator-sponsored research funding (managed by MHRI) from Viiv Healthcare and Gilead Sciences.

Ethics Approval: IRB approval was obtained from both study locations prior to study initiation: IRB#s 2017–0870 and 2017–25.

Consent to participate: All participants signed informed consent prior to initiating the survey

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Aaron E, Blum C, Seidman D, Hoyt MJ, Simone J, Sullivan M, & Smith DK (2018). Optimizing Delivery of HIV Preexposure Prophylaxis for Women in the United States. AIDS Patient Care and STDs, 32(1), 16–23. 10.1089/apc.2017.0201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams LM, & Balderson BH (2016). HIV providers’ likelihood to prescribe pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for HIV prevention differs by patient type: a short report. AIDS Care - Psychological and Socio-Medical Aspects of AIDS/HIV, 28(9), 1154–1158. 10.1080/09540121.2016.1153595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen I. (2011). The theory of planned behaviour: Reactions and reflections. In Psychology and Health (Vol. 26, Issue 9). 10.1080/08870446.2011.613995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen L, Albarracin D, & Hornik R. (2012). Prediction and change of health behavior: Applying the reasoned action approach. In Prediction and Change of Health Behavior: Applying the Reasoned Action Approach. Taylor and Francis. 10.4324/9780203937082 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Albarracín D, Fishbein M, Johnson BT, & Muellerleile PA (2001). Theories of reasoned action and planned behavior as models of condom use: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 127(1), 142–161. 10.1037/0033-2909.127.1.142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amico KR, Balthazar C, Coggia T, Hosek S. (2014) Prep Audio Visual Representation (PrEP REP): Development and pilot of a PrEP education video. International Conference on HIV Treatment and Prevention Adherence. [Google Scholar]

- Amico KR., Ramirez C., Caplan MR., Montgomery BEE., Stewart J., Hodder S., Swaminathan S., Wang J., Darden-Tabb NY., McCauley M., Mayer KH., Wilkin T., Landovitz RJ., Gulick R., & Adimora AA. (2019). Perspectives of US women participating in a candidate PrEP study: adherence, acceptability and future use intentions. Journal of the International AIDS Society, 22(3). 10.1002/JIA2.25247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armitage CJ, & Conner M. (2001). Efficacy of the theory of planned behaviour: A meta-analytic review. British Journal of Social Psychology, 40(4), 471–499. 10.1348/014466601164939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auerbach JD, Kinsky S, Brown G, & Charles V. (2015). Knowledge, attitudes, and likelihood of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) use among US women at risk of acquiring HIV. AIDS Patient Care and STDs, 29(2), 102–110. 10.1089/apc.2014.0142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baeten JM, Donnell D, Ndase P, Mugo NR, Campbell JD, Wangisi J, Tappero JW, Bukusi EA, Cohen CR, Katabira E, Ronald A, Tumwesigye E, Were E, Fife KH, Kiarie J, Farquhar C, John-Stewart G, Kakia A, Odoyo J, … Partners PrEP Study Team. (2012). Antiretroviral Prophylaxis for HIV Prevention in Heterosexual Men and Women. New England Journal of Medicine, 367(5), 399–410. 10.1056/NEJMoa1108524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackstock OJ, Patel V. v., Felsen U, Park C, & Jain S. (2017). Pre-exposure prophylaxis prescribing and retention in care among heterosexual women at a community-based comprehensive sexual health clinic. AIDS Care, 29(7), 866–869. 10.1080/09540121.2017.1286287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bleakley A, & Hennessy M. (2012). The quantitative analysis of reasoned action theory. The annals of the American academy of political and social science, 640(1), 28–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bleakley A, & Hull SJ (forthcoming). A Reasoned Action Approach: The Theory of Reasoned Action, Theory of Planned Behavior, and Integrated Behavioral Model. In Glanz K, Rimer B, & Viswanath K(Eds.), Health Behavior: Theory, Research and Practice (6 ed.). Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Blumenthal J, Jain S, He F, Amico KR, Kofron R, Ellorin E, Stockman JK, Psaros C, Ntim GM, Chow K, Anderson PL, Haubrich R, Corado K, Moore DJ, Morris S, & Landovitz RJ (2021). Results from a Pre-exposure Prophylaxis Demonstration Project for At-risk Cisgender Women in the United States. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 73(7), 1149–1156. 10.1093/CID/CIAB328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogorodskaya M., Lewis SA., Krakower DS., & Avery A. (2020). Low Awareness of and Access to Pre-exposure Prophylaxis But High Interest Among Heterosexual Women in Cleveland, Ohio. Sexually Transmitted Diseases, 47(2), 96–99. 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000001082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowser M, Donahue K, & Nesbitt LS (2022). District of Columbia Department of Health, HIV/AIDS, Hepatitis, STI, & TB Administration 2021. https://dchealth.dc.gov/service/hiv-reports-and-publications

- Bradley E, Forsberg K, Betts JE, DeLuca JB, Kamitani E, Porter SE, Sipe TA, & Hoover KW (2019). Factors Affecting Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis Implementation for Women in the United States: A Systematic Review. Journal of Women’s Health (2002), 28(9), 1272–1285. 10.1089/jwh.2018.7353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley ELP, & Hoover KW (2019). Improving HIV Preexposure Prophylaxis Implementation for Women: Summary of Key Findings From a Discussion Series with Women’s HIV Prevention Experts. In Women’s Health Issues (Vol. 29, Issue 1, pp. 3–7). Elsevier USA. 10.1016/j.whi.2018.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U. (1979). The ecology of human development: Experiments by Nature and Design. Harvard University Press. https://books.google.mu/books?hl=en&lr=&id= [Google Scholar]

- Bush S, Magnuson D, Rawlings M, Hawkins T, McCallister S, & Mera Giler R. (2016). ASM/ICAAC: Racial Characteristics of FTC/TDF for Pre-exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) Users in the US. Racial Characteristics of FTC/TDF for Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) Users in the US. http://www.natap.org/2016/HIV/062216_02.htm

- Bush S, Ng L, Magnuson D, Piontkowsky D, & Mera Giler R. (2015). Significant uptake of Truvada for preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP) utilization in the US in late 2014 – 1Q2015. https://www.iapac.org/AdherenceConference/presentations/ADH10_OA74.pdf

- Calabrese SK, Dovidio JF, Tekeste M, Taggart T, Galvao RW, Safon CB, Willie TC, Caldwell A, Kaplan C, & Kershaw TS (2018). HIV Pre-exposure prophylaxis stigma as a multidimensional barrier to uptake among women who attend planned parenthood. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 79(1), 46–53. 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calabrese SK, Earnshaw VA, Underhill K, Hansen NB, & Dovidio JF (2014). The impact of patient race on clinical decisions related to prescribing HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP): Assumptions about sexual risk compensation and implications for access. In AIDS and Behavior (Vol. 18, Issue 2, pp. 226–240). Springer. 10.1007/s10461-013-0675-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castel AD, Feaster DJ, Tang W, Willis S, Jordan H, Villamizar K, Kharfen M, Kolber MA, Rodriguez A, & Metsch LR (2015). Understanding HIV care provider attitudes regarding intentions to prescribe PrEP. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 70(5), 520–528. 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chittamuru D, Frye V, Koblin BA, Brawner B, Tieu H-V, Davis A, & Teitelman AM (2020). PrEP stigma, HIV stigma, and intention to use PrEP among women in New York City and Philadelphia. Stigma and Health, 5(2), 240–246. 10.1037/SAH0000194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collier KL, Colarossi LG, & Sanders K. (2017). Raising Awareness of Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) among Women in New York City: Community and Provider Perspectives. Journal of Health Communication, 22(3), 183–189. 10.1080/10810730.2016.1261969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dale SK (2020). Using Motivational Interviewing to Increase PrEP Uptake Among Black Women at Risk for HIV: an Open Pilot Trial of MI-PrEP. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities, 7(5), 913–927. 10.1007/S40615-020-00715-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Angelo AB, Davis Ewart LN, Koken J, Bimbi D, Brown JT, & Grov C. (2021). Barriers and Facilitators to Pre-exposure Prophylaxis Uptake Among Black Women: A Qualitative Analysis Guided by a Socioecological Model. The Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care : JANAC, 32(4), 481–494. 10.1097/JNC.0000000000000241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felsher M, Ziegler E, Smith LR, Sherman SG, Amico KR, Fox R, Madden K, & Roth AM (2020). An Exploration of Pre-exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) Initiation Among Women Who Inject Drugs. Archives of Sexual Behavior 2020 49:6, 49(6), 2205–2212. 10.1007/S10508-020-01684-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fishbein M, & Ajzen I. (2011). Predicting and Changing Behavior : The Reasoned Action Approach. Predicting and Changing Behavior: The Reasoned Action Approach, 1–518. 10.4324/9780203838020 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Flash CA, Dale SK, & Krakower DS (2017). Pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV prevention in women: Current perspectives. In International Journal of Women’s Health (Vol. 9, pp. 391–401). Dove Medical Press Ltd. 10.2147/IJWH.S113675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gignac GE, & Szodorai ET (2016). Effect size guidelines for individual differences researchers. Personality and individual differences, 102, 74–78. 10.1016/j.paid.2016.06.069 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Godin G, & Kok G. (1996). The theory of planned behavior: A review of its applications to health- related behaviors. American Journal of Health Promotion, 11(2), 87–98. 10.4278/0890-1171-11.2.87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goparaju L, Experton LS, & Praschan NC (2015). Women want Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis but are Advised Against it by Their HIV-positive Counterparts. Journal of AIDS & Clinical Research, 6(11), 1. 10.4172/2155-6113.1000522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goparaju L, Praschan NC, Jeanpiere LW, Experton LS, Young MA, & Kassaye S. (2017). Stigma, Partners, Providers and Costs: Potential Barriers to PrEP Uptake among US Women. Journal of AIDS & Clinical Research, 08(09). 10.4172/2155-6113.1000730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill LM, Lightfoot AF, Riggins L, & Golin CE (2020). Awareness of and attitudes toward pre-exposure prophylaxis among African American women living in low-income neighborhoods in a Southeastern city. AIDS Care - Psychological and Socio-Medical Aspects of AIDS/HIV. 10.1080/09540121.2020.1769834 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirschhorn LR, Brown RN, Friedman EE, Greene GJ, Bender A, Christeller C, Bouris A, Johnson AK, Pickett J, Modali L, & Ridgway JP (2020). Black Cisgender Women’s PrEP Knowledge, Attitudes, Preferences, and Experience in Chicago. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 84(5), 497–507. 10.1097/QAI.0000000000002377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hull SJ (2012). Perceived risk as a moderator of the effectiveness of framed HIV-test promotion messages among women: A randomized controlled trial. Health Psychology, 31(1), 114–121. 10.1037/a0024702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hull SJ, Tessema H, Thuku J, & Scott RK (2021). Providers PrEP: Identifying Primary Health care Providers’ Biases as Barriers to Provision of Equitable PrEP Services. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes (1999), 88(2), 165–172. 10.1097/QAI.0000000000002750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hull S, & Sichone-Cameron M. (2017). Understanding Determinants of Intentions to Uptake PrEP Among Black Women in DC. [Google Scholar]

- Hull SJ., Duan X., Brant AR., Peng Ye P., Lotke PS., Huang JC., … & Scott RK (2022). Understanding Psychosocial Determinants of PrEP Uptake Among Cisgender Women Experiencing Heightened HIV Risk: Implications for Multi-Level Communication Intervention. Health Communication, 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JD Auerbach SKGBVC (2015). Knowledge, attitudes, and likelihood of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) use among US women at risk of acquiring HIV. AIDS Patient Care and STDS, 29(2), 102–110. 10.1089/apc.2014.0142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman MR, Cornish F, Zimmerman RS, & Johnson BT (2014). Health behavior change models for HIV prevention and AIDS care: Practical recommendations for a multi-level approach. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 66(SUPPL.3). 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koren DE, Nichols JS, & Simoncini GM (2018). HIV Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis and Women: Survey of the Knowledge, Attitudes, and Beliefs in an Urban Obstetrics/Gynecology Clinic. AIDS Patient Care and STDs, 32(12), 490–494. 10.1089/apc.2018.0030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krakower DS, & Mayer KH (2016). The Role of Healthcare Providers in the Roll-Out of PrEP HHS Public Access. Curr Opin HIV AIDS, 11(1), 41–48. 10.1097/COH.0000000000000206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwakwa HA, Bessias S, Sturgis D, Mvula N, Wahome R, Coyle C, & Flanigan TP (2016). Attitudes Toward HIV Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis in a United States Urban Clinic Population. AIDS and Behavior, 20(7), 1443–1450. 10.1007/s10461-016-1407-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mapping PrEP: First Ever Data on PrEP Users Across the U.S. - AIDSVu. (n.d.). Retrieved November 5, 2019, from https://aidsvu.org/prep/

- Marcus JL, Hurley LB, Hare MCB, Silverberg MJ, Volk JE, & Per K. (2016). Disparities inuptake of HIV Preexposure prophylaxis in a large integrated health care system. American Journal of Public Health, 106(10), e2–3. 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEachan R, Taylor N, Harrison R, Lawton R, Gardner P, & Conner M. (2016). Meta-Analysis of the Reasoned Action Approach (RAA) to Understanding Health Behaviors. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 50(4), 592–612. 10.1007/s12160-016-9798-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murnane PM, Celum C, Mugo N, Campbell JD, Donnell D, Bukusi E, Mujugira A, Tappero J, Kahle EM, Thomas KK, Baeten JM, & Partners PrEP Study Team. (2013). Efficacy of preexposure prophylaxis for HIV-1 prevention among high-risk heterosexuals: subgroup analyses from a randomized trial. AIDS (London, England), 27(13), 2155–2160. 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283629037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nydegger LA, Dickson-Gomez J, & Ko Ko T. (2020). A Longitudinal, Qualitative Exploration of Perceived HIV Risk, Healthcare Experiences, and Social Support as Facilitators and Barriers to PrEP Adoption Among Black Women. AIDS and Behavior 2020 25:2, 25(2), 582–591. 10.1007/S10461-020-03015-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ojikutu BO, Amutah-Onukagha N, Mahoney TF, Tibbitt C, Dale SD, Mayer KH, & Bogart LM (2020). HIV-Related Mistrust (or HIV Conspiracy Theories) and Willingness to Use PrEP Among Black Women in the United States. AIDS and Behavior, 24(10), 2927–2934. 10.1007/S10461-020-02843-Z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ojikutu BO., Bogart LM., Higgins-Biddle M., Dale SK., Allen W., Dominique T., & Mayer KH. (2018). Facilitators and Barriers to Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) Use Among Black Individuals in the United States: Results from the National Survey on HIV in the Black Community (NSHBC). AIDS and Behavior, 22(11), 3576–3587. 10.1007/s10461-018-2067-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel AS, Goparaju L, Sales JM, Mehta CC, Blackstock OJ, Seidman D, Ofotokun I, Kempf MC, Fischl MA, Golub ET, Adimora AA, French AL, Dehovitz J, Wingood G, Kassaye S, & Sheth AN (2019). Brief Report: PrEP Eligibility among At-Risk Women in the Southern United States: Associated Factors, Awareness, and Acceptability. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 80(5), 527–532. 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petroll AE, Walsh JL, Owczarzak JL, McAuliffe TL, Bogart LM, & Kelly JA (2017). PrEP Awareness, Familiarity, Comfort, and Prescribing Experience among US Primary Care Providers and HIV Specialists. AIDS and Behavior, 21(5), 1256–1267. 10.1007/s10461-016-1625-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips G, Raman AB, Felt D, McCuskey DJ, Hayford CS, Pickett J, Lindeman PT, & Mustanski B. (2020). PrEP4Love. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 83(5), 450–456. 10.1097/QAI.0000000000002297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinto RM, Berringer KR, Melendez R, & Mmeje O. (2018). Improving PrEP Implementation Through Multilevel Interventions: A Synthesis of the Literature. AIDS and Behavior, 22(11), 3681–3691. 10.1007/S10461-018-2184-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth A, Felsher M, Tran N, Bellamy S, Martinez-Donate A, Krakower D, & Szep Z. (2019). Drawing from the Theory of Planned Behaviour to examine pre-exposure prophylaxis uptake intentions among heterosexuals in high HIV prevalence neighbourhoods in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA: an observational study. Sexual Health, 16(3), 218–224. 10.1071/SH18081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubtsova A, Wingood G, Dunkle K, Camp C, & DiClemente R. (2014). Young Adult Women and Correlates of Potential Adoption of Pre-exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP): Results of a National Survey. Current HIV Research, 11(7), 543–548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sales JM, Escoffery C, Hussen SA, Haddad LB, Phillips A, Filipowicz T, Sanchez M, McCumber M, Rupp B, Kwiatkowski E, Psioda MA, & Sheth AN (2019). Pre-exposure prophylaxis integration into family planning services at title X clinics in the southeastern United States: A geographically-targeted mixed methods study (Phase 1 ATN 155). JMIR Research Protocols, 8(6). 10.2196/12774 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott RK, Hull SJ, Huang JC, Coleman M, Ye P, Lotke P, … & Visconti A. (2022). Factors Associated with Intention to Initiate Pre-exposure Prophylaxis in Cisgender Women at High Behavioral Risk for HIV in Washington, DC. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 51(5), 2613–2624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seidman D, Carlson K, Weber S, Witt J, & Kelly PJ (2016). United States family planning providers’ knowledge of and attitudes towards preexposure prophylaxis for HIV prevention: A national survey. Contraception, 93(5), 463–469. 10.1016/j.contraception.2015.12.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seidman D, Weber S, Carlson K, & Witt J. (2018). Family planning providers’ role in offering PrEP to women. In Contraception (Vol. 97, Issue 6, pp. 467–470). Elsevier USA. 10.1016/j.contraception.2018.01.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senaviratna NAMR, & Cooray A, J. TM (2019). Diagnosing Multicollinearity of Logistic Regression Model. Asian Journal of Probability and Statistics, 5(2), 1–9. 10.9734/ajpas/2019/v5i230132 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sheeran P. (2002). Intention—Behavior Relations: A Conceptual and Empirical Review. European Review of Social Psychology, 12(1), 1–36. 10.1080/14792772143000003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Siegler AJ., Mouhanna F., Giler RM., Weiss K., Pembleton E., Guest J., Jones J., Castel A., Yeung H., Kramer M., McCallister S., & Sullivan PS. (2018). The prevalence of pre-exposure prophylaxis use and the pre-exposure prophylaxis–to-need ratio in the fourth quarter of 2017, United States. Annals of Epidemiology, 28(12), 841–849. 10.1016/j.annepidem.2018.06.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith DK, Toledo L, Smith DJ, Adams MA, & Rothenberg R. (2012). Attitudes and program preferences of African-American urban young adults about pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP). AIDS Education and Prevention, 24(5), 408–421. 10.1521/aeap.2012.24.5.408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith DK, van Handel M, & Grey J. (2018). Estimates of adults with indications for HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis by jurisdiction, transmission risk group, and race/ethnicity, United States, 2015. Annals of Epidemiology, 28(12), 850–857.e9. 10.1016/j.annepidem.2018.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teitelman AM, Chittamuru D, Koblin BA, Davis A, Brawner BM, Fiore D, Broomes T, Ortiz G, Lucy D, & Tieu H-V (2020). Beliefs Associated with Intention to Use PrEP Among Cisgender U.S. Women at Elevated HIV Risk. Archives of Sexual Behavior 2020 49:6, 49(6), 2213–2221. 10.1007/S10508-020-01681-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tekeste M, Hull S, Dovidio JF, Safon CB, Blackstock O, Taggart T, … & Calabrese SK (2019). Differences in medical mistrust between black and white women: implications for patient–provider communication about PrEP. AIDS and Behavior, 23(7), 1737–1748 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thigpen MC, Kebaabetswe PM, Paxton LA, Smith DK, Rose CE, Segolodi TM, Henderson FL, Pathak SR, Soud FA, Chillag KL, Mutanhaurwa R, Chirwa LI, Kasonde M, Abebe D, Buliva E, Gvetadze RJ, Johnson S, Sukalac T, Thomas VT, … Brooks JT (2012). Antiretroviral preexposure prophylaxis for heterosexual HIV transmission in Botswana. New England Journal of Medicine, 367(5), 423–434. 10.1056/NEJMoa1110711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wingood GM, Dunkle K, Camp C, Patel S, Painter JE, Rubtsova A, & DiClemente RJ (2013). Racial Differences and Correlates of Potential Adoption of Preexposure Prophylaxis. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 63, S95–S101. 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182920126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu H, Mendoza MCB, Huang YLA, Hayes T, Smith DK, & Hoover KW (2017). Uptake of HIV preexposure prophylaxis among commercially insured Persons-United States, 2010–2014. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 64(2), 144–149. 10.1093/cid/ciw701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yzer M. (2017). Reasoned action as an approach to understanding and predicting health message outcomes. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Communication. [Google Scholar]