Abstract

Purpose:

It is generally believed that large eyelid defects must be repaired using a vascularized flap for 1 lamella, while the other can be a free graft. Recent studies indicate that the pedicle of a tarsoconjunctival flap does not contribute to blood perfusion. The purpose of this study was to explore whether large eyelid defects can be repaired using a free bilamellar eyelid autograft alone.

Methods:

Ten large upper and lower eyelid defects resulting from tumor excision were reconstructed using bilamellar grafts harvested from the contralateral or opposing eyelid. Revascularization of the flap was monitored during healing using laser speckle contrast imaging, and the surgical outcome was assessed.

Results:

The functional and cosmetic results were excellent. All grafts survived and there was no tissue necrosis. Only 1 patient underwent revision after 4 days as the sutures came loose. Two patients developed minimal ectropion but needed no reoperation. All patients were satisfied with the surgical results. Perfusion monitoring showed that the grafts were gradually revascularized, exhibiting 50% perfusion after 4 weeks and 90% perfusion after 8 weeks.

Conclusions:

A free bilamellar eyelid graft appears to be an excellent alternative to the tarsoconjunctival flap procedure in the reconstruction of both upper and lower eyelid defects, especially in patients who cannot tolerate visual axis occlusion or the 2-stage procedure of the conventional staged flap procedure.

The reconstruction of large lower and upper eyelid defects is based on the assumption that a vascularized flap must be used to repair one of the lamellae (to ensure the survival of the reconstructed eyelid), while the other can be a free graft. The most frequently used surgical technique for the reconstruction of the lower eyelid is the modified Hughes procedure, where the posterior lamella is repaired using a tarsoconjunctival flap from the upper eyelid, and the anterior lamella is created using a skin graft.1–3 Defects in the upper eyelid may be repaired using the Cutler-Beard procedure, in which a full-thickness flap from the lower eyelid is advanced posterior to an intact lower eyelid margin.4 In both cases, the visual axis is occluded by the pedicle during healing/revascularization. The pedicle is only divided when vascularization is deemed adequate (2–4 weeks with the Hughes procedure and 6 weeks to 3 months with the Cutler-Beard procedure).

Alternative single-stage procedures have been developed over the years to avoid eye occlusion. The posterior lamella may be repaired with a free tarsal graft or a free chondromucosal graft from the nasal septum, and the anterior lamella is then repaired using a vascularized advancement flap.5 Paridaens and van den Bosch6 suggested a “sandwich” technique for repairing lower eyelid defects, using an orbicularis muscle advancement flap covering a free graft on both sides. However, single-stage procedures for the repair of large eyelid defects are challenging, and a Hughes flap is still the most commonly used procedure.5

Werner et al.7 treated colobomas of the eyelid removing a full-thickness section of the contralateral eyelid and then removing the skin and orbicularis muscle, but leaving the eyelid margin, conjunctiva, and eyelid retractors. A skin flap was used to cover the graft.7 However, to the best of the authors' knowledge, free grafts have not been used for the repair of both the anterior and posterior lamella, with the exception of a case report from 1951 Callahan described a method of successfully repairing a central coloboma of the upper eyelid using a free bilamellar graft from the contralateral eyelid after shortening the horizontal dimension of the defect from 11 to 5,5 mm with sutures.8 An additional number of studies suggest that the use of a free bilamellar graft may be possible. The authors have described a case in which two-thirds of an upper eyelid was traumatically amputated and then simply sutured back into place. The outcome 10 years after the trauma regarding motility, cosmetic appearance, and function was excellent.9 The authors have also reported a case in which the excision of a carcinoma caused a large upper eyelid defect that was repaired using a free bilamellar eyelid autograft from the ipsilateral lower eyelid.10 In this case, the graft healed well, and both the functional and cosmetic results were excellent. Reed et al.11 repaired 28 upper eyelid defects in pigs using bilamellar autografts. All grafts but one were viable, and histopathological analysis showed that the vascularization was equivalent to that in an unaffected eyelid after 30 days. Other studies on patients have reported excellent results after premature flap dehiscence occurring 1 to 11 days after the modified Hughes procedure,12 and after early division of the conjunctival pedicle in the Hughes procedure after only 113 or 2 weeks.14 Small optical buttonholes in the Hughes tarsoconjunctival flap have been found not to compromise the viability of the flap or the outcome.15

The findings of these studies suggest that a vascularized flap may not be necessary in lower eyelid reconstruction. Indeed, blood perfusion monitoring by laser Doppler velocimetry and laser speckle contrast imaging (LSCI) has shown that the conjunctival pedicle did not contribute to the blood supply in the tarsus in the Hughes procedure, in pigs16 or in patients.17 Furthermore, LSCI showed that the overlying skin grafts revascularized well within 3 to 8 weeks.18

These findings led the authors to hypothesize that it may be possible to repair large eyelid defects using a free bilamellar eyelid graft. This would have the dual benefits of being a single-stage procedure and avoiding visual axis occlusion. The aim of this study was thus to explore the possibility of repairing large lower and upper eyelid defects using an autologous free bilamellar eyelid graft, harvested from the contralateral or opposing eyelid. To the best of the authors knowledge, this surgical technique has not previously been reported in patients.

METHODS

Ethics.

The experimental protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee at Lund University, Sweden. The research was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki as amended in 2008. Fully informed consent was obtained from all the patients participating in the study.

Subjects.

Patients with large upper or lower eyelid defects (>50% of the width) after tumor excision, with a strong wish to avoid visual axis occlusion and/or a second surgical procedure, were offered surgical repair with a free bilamellar eyelid graft. Exclusion criteria were inability to provide informed consent, and physical or mental inability to cooperate during the local anesthetic procedure. All patients who were offered the surgical procedure accepted surgery and participation in the study.

This study includes 8 patients admitted to the eye clinics at the Skåne University Hospital in Lund and 2 patients admitted to the St. Erik Eye Hospital in Stockholm, between 2015 and 2020. Four surgeons carried out the operations: Karl Engelsberg, Elin Bohman, Malin Malmsjö, and Johanna V. Berggren. The characteristics of the patients are presented in the Table.

Patient characteristics

| Patient | Gender | Age (year) | Type of tumor | Tumor location (horizontal size of the defect, mm) | Donor site (horizontal size of the graft, mm) | Tenzel flap | Smoker | Cardiovascular disease | Diabetes | Hypertensive treatment | Anticoagulant treatment | Steroid treatment | Follow up (days) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1* | Male | 60 | Squamous cell carcinoma in situ | Left, upper (12 mm) | Left, lower (11 mm) | Yes (donor site) | No | No | No | No | No | No | 1,559 |

| 2 | Female | 88 | Basal cell carcinoma type 3 | Left, lower (14 mm) | Right, lower (9 mm) | Yes (donor site and recipient site) | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | 1,090 |

| 3 | Female | 75 | Benign intradermal nevus | Right, lower (20 mm) | Left, lower (15 mm) | Yes (donor site and recipient site) | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | 61 |

| 4 | Male | 95 | Basal cell carcinoma type 2 | Left, lower (19 mm) | Right, lower (13 mm) | Yes (recipient site) | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | 19 |

| 5 | Female | 86 | Basal cell carcinoma type 3 | Left, lower (21 mm) | Right, lower (17 mm) | Yes (donor site) | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | 399 |

| 6 | Female | 95 | Basal cell carcinoma type 1 | Left, lower (23 mm) | Right, lower (19 mm) | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | 90 |

| 7 | Male | 80 | Squamous cell carcinoma | Left, lower (20 mm) | Right, lower (17 mm) | Yes (donor site) | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | † |

| 8 | Female | 60 | Basal cell carcinoma type 2 | Right, upper (17 mm) | Left, upper (12 mm) | No | >10 years ago | No | No | No | No | No | 56 |

| 9 | Female | 76 | c | Left, lower (14 mm) | Right, lower (9 mm) | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | 105 |

| 10 | Female | 64 | Basal cell carcinoma type 2 | Left, upper (15 mm) | Right, upper (10 mm) | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | 42 |

*Previously reported case.10

†Sutures came loose after 3 days. The graft appeared viable but was removed as the eyelid had stretched and could be closed without the graft at this time.

Surgical Procedure.

Surgery was carried out under local infiltration anesthesia with 20 mg/ml lidocaine (Xylocaine, AstraZeneca, Södertälje, Sweden) and Tetracaine eye drops (Tetracaine, Bausch & Lomb, Rochester, NY). After the tumors had been excised, bilamellar eyelid grafts, i.e., a skin-mucocutaneous-tarsoconjunctival graft without a pedicle, was harvested from the contralateral or opposing upper or lower eyelid (see the Table for details), using a pentagonal excision. The size of the defects ranged from 12 to 23 mm, and the size of the grafts ranged from 9 to 19 mm. The donor site was then closed. A Tenzel flap was required in 5 patients to reduce tension and close the donor site. In all patients apart from the first, the graft was harvested from the contralateral eye so that the ipsilateral, opposing eyelid would be preserved if further reconstruction proved necessary. The bilamellar graft was sutured in place using 5/0 or 6/0 resorbable sutures (Vicryl, Ethicon, Somerville, NJ) for the tarsal plate, and 6/0 nonabsorbable nylon sutures (Ethilon, Ethicon, Somerville, NJ) for the skin. A Tenzel flap was required in 3 patients to reduce the tension in the bilamellar graft. Chloramphenicol ointment (Chloromycetin 1%, Pfizer, New York, NY) or fusidic acid viscous eye-drops (Fucithalmic 1%, LEO Pharmaceutical Ltd., Ballerup, Denmark) was applied 2 to 3 times daily for the next 7 days. The superficial skin sutures were removed 7 to 8 days postoperatively.

Laser Speckle Contrast Imaging.

Blood perfusion was monitored using LSCI (PeriCam PSI NR System, Perimed AB, Stockholm, Sweden), which is a noninvasive perfusion monitoring technique employing an infrared 785 nm laser beam that is diffusely reflected from the surface of the skin. Dark and bright areas are formed by random interference of the light backscattered from the illuminated area creating a speckled pattern, which is recorded in real time by a camera. The recording rate is up to 100 images per second, and the spatial resolution is up to 100 μm/pixel. The variations in the speckle pattern are automatically analyzed and the blood perfusion was calculated by the software in the system. A medium-sized corneal shield (Ellman International Inc., Oceanside, NY) was applied to protect the eye from laser irradiation and prevent interference due to the laser signal resulting from blood flow in the underlying tissues.

Blood Perfusion Monitoring and Surgical Outcome.

Blood perfusion was monitored in 6 of the patients undergoing surgery in Lund. One patient dropped out of the study when the sutures came loose and the graft was removed. The blood perfusion obtained with LSCI is given in arbitrary units (perfusion units [PU]). Perfusion was monitored immediately postoperatively (denoted 0 weeks) and at several follow-up visits. Due to logistic reasons, the time of the follow-up visits varied. The data were therefore grouped into the following time intervals: follow up at 4 to 9 days (denoted 1 week), 14 to 19 days (denoted 2 weeks), 28 to 33 days (denoted 4 weeks), and 56 to 61 days (denoted 8 weeks). The surgical outcome was assessed in terms of functional and cosmetic results, including graft failure, eyelid apposition to the globe, other postoperative complications, and patient satisfaction.

Calculations and Statistical Analysis.

Blood perfusion is expressed as the percentage of normal perfusion at a point just outside the graft in undissected tissue (median values and 95% confidence intervals). The perfusion values in the graft immediately postoperatively were set to 0%. Calculations and statistical analysis were performed using GraphPad Prism 7.0a (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA).

RESULTS

Surgical Outcome.

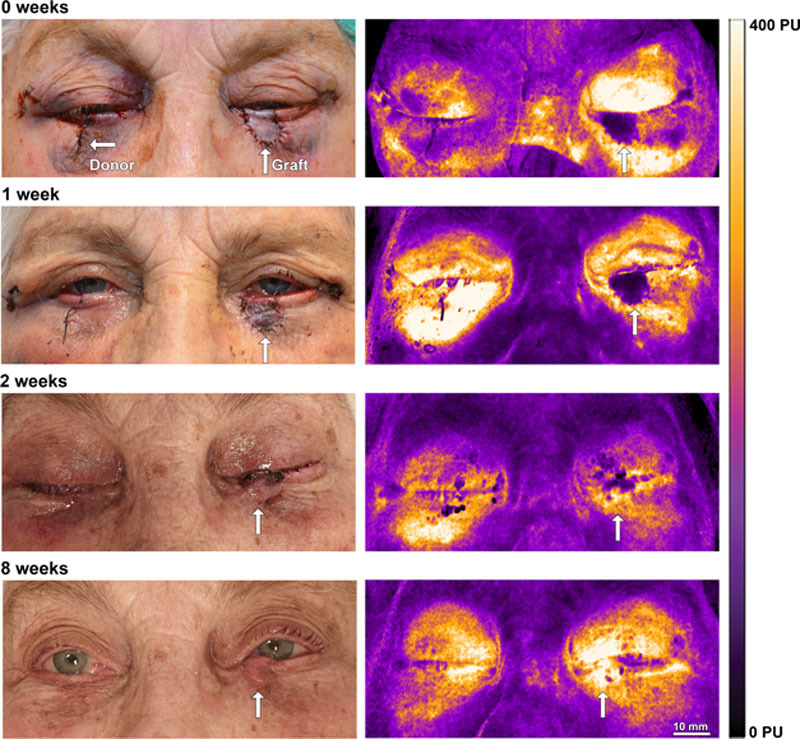

Surgery was successful in all cases. No graft failure or tissue necrosis was seen. The grafts were discolored and swollen during the first week, as expected, but then gradually regained their natural appearance as they became revascularized (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Representative example of a patient who has undergone surgery with a free bilamellar graft on the lower eyelid, taken from the contralateral eyelid. Tenzel flaps were used on OU to reduce tension on the graft and at the donor site. The healing process is illustrated on the left, showing initial swelling and discoloration of the graft, which was resolved after 2 weeks. The LSCI images on the right show the gradual revascularization of the graft (white arrows). LSCI, laser speckle contrast imaging.

Only 1 patient underwent revision, after 4 days, as the medial sutures came loose, believed to be due to excess tension in the repaired eyelid. In this case, the defect could be closed without the graft in place and the graft was removed and discarded, despite appearing to be viable. The authors believe that the increased eyelid tension during the 4 days the graft was in place expanded the eyelid tissue allowing direct closure.

Two patients developed minimal ectropion in the receiving lower eyelid, but neither experienced any symptoms. Both were satisfied and no reoperation was necessary. In all other cases, the apposition of the eyelids to the globe was good.

Slight conjunctival overgrowth at the receiving lower eyelid margin occurred in 2 patients, but neither had any complaints or required further surgery. The eyelashes only survived on the graft in 1 case. In 1 case, 3 remaining eyelashes were found in the grafted part of the eyelid at the 3-month follow up.

The ocular surface of the graft-receiving eye was intact and none of the patients developed keratitis. In 1 case, a resorbable suture in the donor eyelid caused superficial corneal erosion 11 days postoperatively. This healed quickly after treatment with chloramphenicol ointment and no scarring was observed. No other complications were reported at the donor site. All donor sites healed well with minimal scarring and excellent functional and esthetic/cosmetic results.

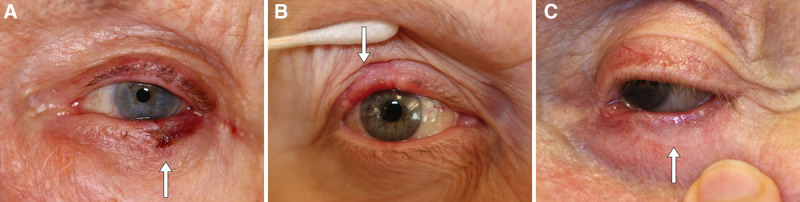

All patients were satisfied with the surgical results, and none requested reoperation for functional or cosmetic reasons. Representative examples of the surgical results are given in Figure 2.

FIG. 2.

Representative examples showing postoperative results of bilamellar grafts (white arrows) from 3 different patients after (A) 2 weeks, (B) 8 weeks, and (C) 3 months after surgery, showing excellent functional and cosmetic results.

To date, there have been no cases of tumor recurrence. In 1 case, the initial excision was later found not to be radical, and extended excision and reconstruction were required.

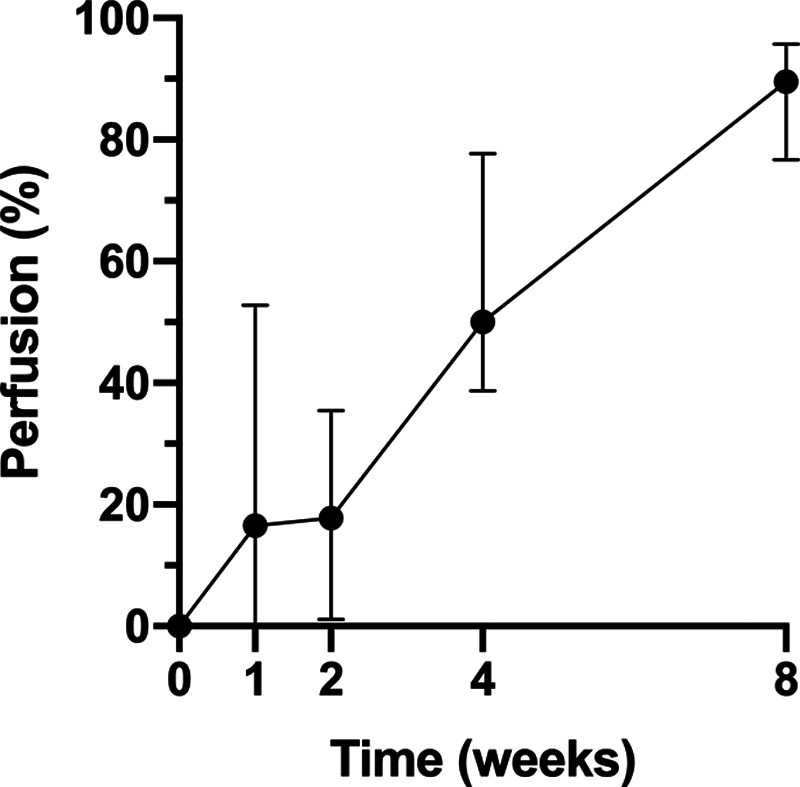

Blood Perfusion Measurements.

Perfusion monitoring with LSCI showed that the grafts were gradually revascularized, and that 50% perfusion was achieved after 4 weeks and 90% perfusion after 8 weeks (Fig. 3), indicating almost complete revascularization at this time.

FIG. 3.

Blood perfusion in the free bilamellar grafts, immediately postoperatively (0 weeks), and at follow up after 1, 2, 4, and 8 weeks. Data are expressed as the percentage (median values and 95% CIs) after normalization to the perfusion at a reference point just outside the graft (100%) and perfusion in the graft immediately postoperatively (0%). Data are shown for 6 patients (1 of the 7 patients in which perfusion was measured dropped out of the study when the sutures came loose, and the graft was removed). It can be that the perfusion increases during healing, as the graft becomes revascularized. CI, confidence interval.

DISCUSSION

The free bilamellar autograft procedure offers an alternative reconstructive technique to the conventional approach using a vascularized flap for the repair of 1 lamella and a free graft for the repair of the outer lamella. The bilamellar grafts in the present study showed excellent survival, and a vascularized flap thus does not appear to be necessary for graft survival. This may be because the periorbital region has a rich vascular supply and is known to be forgiving in reconstructive surgery. Furthermore, the graft is also in contact with the tear film, which has been found to have the same spectrum of nutrients as the blood.19 Indeed, nasal wings can be repaired with a free composite graft from the outer ear without the use of a vascularized flap.

The most significant clinical advantage of this bilamellar graft is that it is a 1-stage procedure, reducing both the cost of health care and the suffering of the patient. Furthermore, the visual axis is not occluded, providing a considerable improvement for the patient, especially if the vision of the contralateral eye is poor. A surgical advantage of a bilateral graft is that it is easier to move both the posterior and anterior lamella simultaneously, in 1 graft, instead of the traditional approach, in which the anterior and posterior lamellae are repaired separately. Furthermore, the color and texture are a better match when the graft is taken from the other eyelid, which may improve the cosmetic result. All the patients in the present study were satisfied with the results, and there was no need for additional surgery.

Skin tumors are the most common cause of eyelid defects and are most common in the elderly. Increasing eyelid laxity with age makes the unaffected eyelid an excellent donor site. However, when harvesting a large bilamellar graft, the eyelid laxity may not be sufficient for simple closure of the wound. A Tenzel flap was required to close the donor site in 5 of the 9 patients in this study. Three patients required a Tenzel flap on the recipient eyelid. In 1 patient without a Tenzel flap, the sutures for the bilamellar graft loosened after 3 days. The authors believe that the tension in the eyelid may have been too great, causing the sutures to cut through the delicate tissue of the graft. This could perhaps have been avoided by the use of a Tenzel flap, or a larger graft, to reduce the tension.

A possible disadvantage of a free bilamellar graft could be the lack of vertical lifting during healing, as is provided by the flap pedicle in the Hughes procedure.5 Furthermore, when using a bilamellar graft, there will be no second operation for pedicle division, during which the final position of the lower eyelid margin can be adjusted, if necessary. However, only 2 patients in this study developed minimal ectropion, which did not need to be surgically corrected. Possible effects of the lack of vertical lifting on the lower eyelid margin position could be minimized if care is taken to adjust the eyelid tension during the bilamellar graft. It is also important to take the donor site in consideration. In this study, there were no complications of the donor site reported in any cases. However, the potential distress of patients having surgery not only in 1 eyelid but both should not be downplayed.

The main limitation of the present study is the small number of patients. The effects of impaired microcirculation, due, for example, to diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease, smoking, or other factors that are known to potentially affect surgical outcome, cannot therefore be deduced from the results of this study. It would be of great interest to study whether the survival of bilamellar autograft is affected in higher-risk populations, in a future study. Nor can any conclusions be drawn about the effect of the graft size on survival, or whether there are differences between the upper and lower eyelids as the recipient of a graft. A larger study group would be needed to investigate these factors.

The authors have reported the successful reconstruction of large upper and lower eyelid defects in 9 patients using a free bilamellar autograft, as an alternative to reconstructing one of the lamellae using a vascularized flap. The major advantages of this procedure are that it is a single-stage procedure, and there is no need for visual axis occlusion, thus reducing health care costs and patient suffering. All grafts survived, there was no tissue necrosis, and the functional and cosmetic outcome was excellent. Laser speckle contrast imaging showed the gradual revascularization of the graft, reaching 90% of normal perfusion after 8 weeks.

In conclusion, the authors believe that this surgical technique for repairing large eyelid defects can reduce costs and patient suffering, while at the same time providing excellent functional and cosmetic outcomes.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We particularly thank all the surgical staff involved at the Skåne University Hospital in Lund, Sweden, especially Maria Schalén.

Footnotes

Supported by the Swedish Government Grant for Clinical Research (Avtal om läkarutbildning och forskning), Skåne University Hospital (SUS) Research Grants, Skåne County Council Research Grants, the Lund University Grant for Research Infrastructure, Crown Princess Margaret's Foundation (Kronprinsessan Margaretas Arbetsnämnd för Synskadade), the Foundation for the Visually Impaired in the County of Malmöhus, The Nordmark Foundation for Eye Diseases at Skåne University Hospital, a Lund Laser Center Research Grant, Carmen and Bertil Regnér's Foundation, and the Swedish Eye Foundation.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hughes WL. Total lower lid reconstruction: technical details. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1976; 74:321–329. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hughes WL. Reconstruction of the lids. Am J Ophthalmol. 1945; 28:1203–1211. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hughes WL. A new method for rebuilding a lower lid. Report of a case. Arch Ophthalmol. 1937; 17:1008–1017. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cutler NL, Beard C. A method for partial and total upper lid reconstruction. Am J Ophthalmol. 1955; 39:1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Collin JRO. A Manual of Systematic Eyelid Surgery. 2006, 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Inc [Google Scholar]

- 6.Paridaens D, van den Bosch WA. Orbicularis muscle advancement flap combined with free posterior and anterior lamellar grafts: a 1-stage sandwich technique for eyelid reconstruction. Ophthalmology. 2008; 115:189–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Werner MS, Olson JJ, Putterman AM. Composite grafting for eyelid reconstruction. Am J Ophthalmol. 1993; 116:11–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Callahan A. The free composite lid graft. AMA Arch Ophthalmol. 1951; 45:539–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berggren JV, Tenland K, Hult J, Blohmé J, et al. Successful repair of a full upper eyelid defect following traumatic amputation by simply suturing it back in place. JPRAS Open. 2019; 19:73–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Memarzadeh K, Sheikh R, Malmsjo M. Large eyelid defect repair using a free eyelid graft. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2017; 5:e1413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reed D, Soeken T, Brundridge W, et al. Repair of a Full-thickness eyelid defect with a bilamellar full-thickness autograft in a porcine model (Sus scrofa). Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2019. Dec 16. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bartley GB, Messenger MM. The dehiscent Hughes flap: outcomes and implications. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 2002; 100:61–65. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leibovitch I, Selva D. Modified Hughes flap: division at 7 days. Ophthalmology. 2004; 111:2164–2167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McNab AA, Martin P, Benger R, et al. A prospective randomized study comparing division of the pedicle of modified Hughes flaps at two or four weeks. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001; 17:317–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leibsohn JM, Dryden R, Ross J. Intentional buttonholing of the Hughes’ flap. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 1993; 9:135–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Memarzadeh K, Gustafsson L, Blohmé J, et al. Evaluation of the microvascular blood flow, oxygenation, and survival of tarsoconjunctival flaps following the modified Hughes procedure. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2016; 32:468–472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tenland K, Memarzadeh K, Berggren J, et al. Perfusion monitoring shows minimal blood flow from the flap pedicle to the tarsoconjunctival flap. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2019; 35:346–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Berggren J, Tenland K, Ansson CD, et al. Revascularization of free skin grafts overlying modified Hughes tarsoconjunctival flaps monitored using laser-based techniques. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2019; 35:378–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jalbert I. Diet, nutraceuticals and the tear film. Exp Eye Res. 2013; 117:138–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]