Abstract

Regulatory focus theory suggests that promoters are more concerned with growth and preventers are more concerned with security. Since coaching is a growth-oriented process, it seems to be more suitable for clients high on promotion than for clients high on prevention. Applying regulatory fit theory, the present research investigates how preventers can also benefit from coaching. First, a study looking at real coaching processes (N1 = 103) found that a higher promotion than prevention focus was indeed related to more coaching success, i.e., satisfaction and approach motivation. Next, testing the hypothesis that fit effects should also be present in coaching, a study using a vignette approach (N2 = 99) shows that participants experiencing a fit between their focus and a promotion versus a prevention coaching indicate a better coaching evaluation than participants experiencing no fit. In three studies (N3a = 120, N3b = 85, N3c = 189), we used an experimental approach and manipulated the regulatory focus of coaching interventions. We found promotion as well as prevention fit effects showing that participants experiencing a fit indicate more coaching success than participants experiencing no fit. Two studies (N4a = 41, N4b = 87) further tested interpersonal fit, i.e., the fit between the coach’s and client’s regulatory focus. We found promotion as well as prevention fit effects on participants’ satisfaction with and trust in a coach (Study 4a) and promotion fit effects on participants’ goal attainment and coaching progress (4b). The findings suggest that by adapting coaching to the client’s focus, coaching success can be increased not only for promoters but also for preventers. Thus, we found that regulatory fit effects, albeit small to medium, are also present in coaching. Multiple studies assessing multiple variables relevant to coaching showed that the findings differ regarding the interventions used and the variables that we looked at. The practical implications of these findings are discussed.

Introduction

According to regulatory focus theory [1], individuals use two self-regulatory systems to navigate through the environment—the growth-oriented promotion system and the security-oriented prevention system. Individuals can differ in the expression of the promotion and prevention system [1] such that promoters (i.e., individuals who are rather driven by the promotion system) are oriented towards growth, change, and success, and preventers (i.e., individuals who are rather driven by their prevention system) are oriented towards security and the avoidance of risks and failure. Previous research has shown the benefits of an individual’s perceived person-environment fit, in particular a regulatory fit between one’s self-regulatory system and the current situation [2]. A situation that may be more suitable for promoters than for preventers is the coaching situation. Coaching can be seen as a growth- and change-oriented process [3–9]. As promoters are growth- and change-oriented and preventers are security-oriented and rather change-aversive, coaching may in general be more successful when coaching clients are more promotion- than prevention-focused. But can preventers who have difficulties disengaging themselves from their status quo also benefit from coaching? If prevention-oriented clients set goals that match their prevention focus, a typically growth-oriented coaching process that uses promotion-focused interventions would be at odds with the client’s prevention focus. Imagine, for example, a person hiring a coach to eliminate stress factors in their job (i.e., a prevention-focused coaching goal). If the coach chooses promotion-oriented interventions such as developing new relaxation strategies, the client’s motivation to work on their goal may decrease. If the coach chooses prevention-oriented interventions such as exploring existing coping strategies which the client already applied in similar situations, the client’s motivation may increase as the intervention fits the regulatory focus.

In the present research, we first investigate the hypothesis that in general, individuals with a promotion focus benefit more from coaching than individuals with a prevention focus. Second, we apply regulatory fit theory [2] to coaching. Given the extensive research on the positive effects of regulatory fit in different areas, we investigate the hypothesis that the effectiveness of a regulatory fit also exists in coaching. We especially focus on individuals high on prevention who should benefit more from coaching when the coach uses prevention-oriented interventions rather than promotion-oriented interventions. Since there is little literature on regulatory fit in coaching, we do not know how important regulatory fit is for coaching and consequently, which coaching variables are particularly affected by regulatory fit. Thus, the aim of the current article is two-fold, examining whether applying regulatory fit to coaching has benefits and examining the coaching outcomes that are particularly affected by regulatory fit. We chose a multimethod approach (investigating real and imagined coaching processes; paper-pencil and online studies, and a behavioral observation study; assessing regulatory focus and qualitatively analyzing regulatory focus; creating a fit by developing promotion- vs. prevention-oriented coaching descriptions and interventions, and by analyzing the language of coach and client), different samples (real coaching clients, student samples, participants working in different professions), and multiple dependent variables that have shown to be relevant variables for coaching success.

Coaching and outcome taxonomies

Coaching is a consultancy format which is applied to different contexts and approaches. Research has shown that coaching is successful including, for example, high satisfaction, well-being, and goal attainment [3]. There are various definitions of what coaching is. For example, it is defined as “a human development process (…) to promote desirable and sustainable change for the benefit of the client and potentially other stakeholders” [4 p1], in which “organizationally, professionally, and personally beneficial development goals” [5 p73] are identified and achieved. It is a process which has the purpose of “fostering the on-going self-directed learning and personal growth of the client” [6 p2] and “achieving some type of change, learning or new level of individual or organizational performance” [7 p15]. Other definitions also emphasize the aim of self-change, self-development, learning, and performance [8, 9]. Summarizing these definitions, there seems to be agreement that coaching is an interaction between a coach and a coachee, aimed at the achievement of goals, change, growth, and self-development.

Meta-analyses show positive effects of coaching on many outcome variables [5, 10–15]. In our studies, we use different outcomes and classify them according to different taxonomies: Kirkpatrick [16] provides a taxonomy of training evaluation consisting of the categories reaction (e.g., satisfaction), learning (e.g., declarative knowledge), behavior (e.g., changes in leadership behavior), and result (e.g., organizational performance). Regarding the learning category, Kraiger et al. [17] differs between affective outcomes, i.e. attitudinal and motivational change such as positive affect, cognitive outcomes, i.e., knowledge acquisition or cognitive strategies such as self-awareness or cognitive flexibility, and performance and skill-based learning outcomes (e.g., vocational skills). Four coaching meta-analyses [10, 11, 14, 15] suggested the outcome category “psychological well-being” which aims at longer-term/distal well-being-related constructs (e.g., life satisfaction). Given that goal attainment is a central criterion to measure coaching success [e.g., 18], a review article on goal activities in coaching [19] and two meta-analyses [12, 15] proposed adding a goal category. Moreover, one meta-analysis [5] suggested the category relationship outcomes that includes for example trust, credibility, or the working alliance.

The Extended model for the evaluation of coaching [3, 20] differentiates between general proximal outcomes, coaching-specific proximal outcomes, and distal outcomes. General proximal outcome variables are variables used in various areas of personal development and beyond. These variables are, for example, reported satisfaction with coaching and goal attainment [19]. Coaching-specific proximal outcome variables are variables that show the specific characteristics and strengths of coaching compared to other interventions. Such variables used in coaching research are, for example, self-efficacy [21, 22] and self-esteem [23]. Distal outcomes are effects that need time in order to unfold. A distal outcome variable is, for example, life satisfaction [24].

In our research, we chose coaching outcomes described as relevant factors in the coaching meta-analyses [5, 10–15], i.e., satisfaction with coaching, positive and negative affect, self-esteem, self-efficacy, goal attainment, goal-related motivation, and trust. Next to these outcome variables, we chose outcomes described as relevant in general research on counseling and goals, i.e., approach motivation, enhanced understanding, strengthened motivation, and action implementation. In addition, Greif [3, 20] mentions process variables including the coaching relationship, client and coach characteristics, and antecedent variables that make the outcomes of coaching possible.

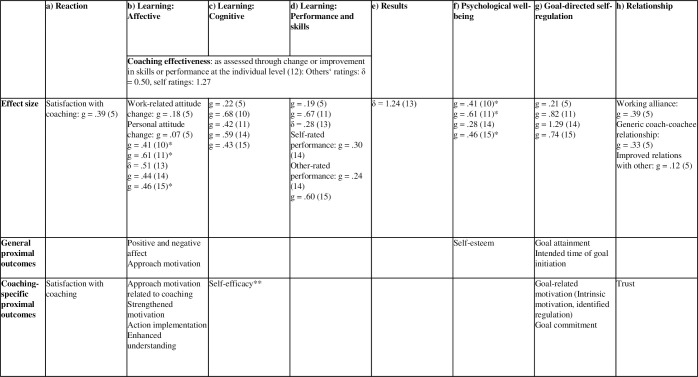

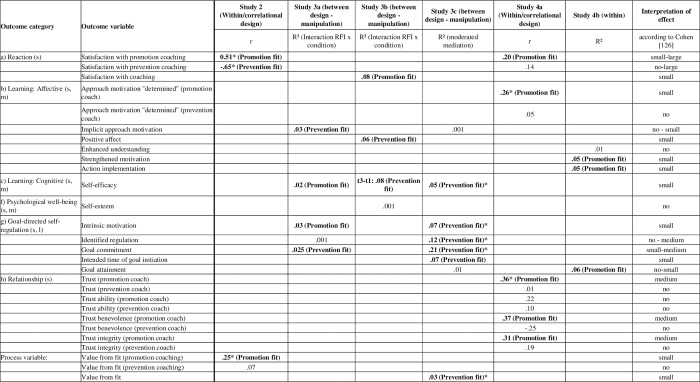

In Fig 1, we classified the variables assessed in our studies into the eight categories proposed by the meta-analyses [5, 10–15]: (a) Reaction, (b) Learning: Affective, (c) Learning: Cognitive, (d) Learning: Performance and skills, (e) Results, (f) Psychological Well-being, (g) Goal-directed self-regulation, and (h) Relationship. The effect sizes of the different outcome categories reported in the meta-analyses are also shown in Fig 1. Based on Greif 3, [20], we further differentiated between general proximal outcomes and coaching-specific proximal outcomes.

Fig 1. Classification and effect sizes of coaching variables according to the taxonomies used in the coaching meta-analyses and the taxonomy by Greif [3, 20].

The categories are described in the meta-analyses as follows: Reaction: Satisfaction with coaching [5]. Learning: Affective: Work-related attitude change [5]: e.g., motivation, self-efficacy, motivation to transfer coached skills; Personal attitude change [5]: e.g., reduced stress, happiness; Well-being [10]: e.g., DASS = Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale, NAS = Negative Affect Scale, PAS = Positive Affect Scale, SPWB = Scales of Psychological Well-being, SWLS = Satisfaction with Life Scale, WWBI = Workplace Well-being Inventory; Well-being [11]: Well-being, hope, resilience, reduced stress, increased life satisfaction, and experienced support; Affective outcomes [13]: Attitudes and motivational outcomes (e.g., self-efficacy, well-being, satisfaction); Affective outcomes [14]: Attitudinal, commitment and motivational outcomes (e.g., organizational commitment, job satisfaction); Well-being [15]: subjective and objective outcome measures that are a direct representation of peoples’ well-being, health, need fulfillment, and affective responses (e.g., measures of psychopathology and burnout). Learning: Cognitive: Cognitive change [5]: e.g. self-awareness, strategic thinking, emotional intelligence; Coping [10]: e.g., Cognitive Hardiness Scale; preparedness [11]: e.g. self-awareness, self-efficacy; Cognitive outcomes [13]: declarative knowledge; procedural knowledge; cognitive strategies (e.g., problem-solving); Cognitive outcomes [14]: knowledge acquisition, knowledge organization and cognitive strategies such as clients’ self-reflection, self-awareness and self-understanding of learning progress and strategy; consisting of a) general perceived efficacy (e.g. self-awareness, self-efficacy) and b) goal attainment; Coping [15]: outcome measures related to the ability to deal with present and future job demands and stressors (e.g., self-efficacy, mindfulness). Learning: Performance and skills: Professional skills/performance [11]: Performance measures (e.g., consultation skills); Skill-based outcomes [13]: Compilation and automaticity of new skills (e.g., leadership skills, technical skills, competencies); Generic behavioral change [5]: e.g., improved job performance, technical skills, leadership skills, impact and influence; Skill-based/performance outcomes [14]: Development of technical skills that links goal; consisting of a) self-rated performance and b) other-rated performance; Performance/skills [15]: Subjective and objective outcome measures that either directly reflect performance (e.g. number of sales, supervisory rated job performance) or reflect the demonstration of behaviors needed for an organization to be effective (e.g., transformational leadership behaviors). Results: coaching impact at the organizational level [12]: e.g., productivity, employee satisfaction; Results [13]: Individual, team, and organizational performance (e.g., financial results, objective or goal achievement, productivity). Psychological well-being: Well-being [10]: e.g., DASS = Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale, NAS = Negative Affect Scale, PAS = Positive Affect Scale, SPWB = Scales of Psychological Well-being, SWLS = Satisfaction with Life Scale, WWBI = Workplace Well-being Inventory; Well-being [11]: Well-being, hope, resilience, reduced stress, increased life satisfaction, and experienced support; Workplace psychological well-being [14]: Self-acceptance, purpose in life, positive relations with others, environmental mastery and autonomy (e.g., mental health or resilience); Well-being [15]: subjective and objective outcome measures that are a direct representation of peoples’ well-being, health, need fulfillment, and affective responses” (e.g., measures of psychopathology and burnout). Goal-directed self-regulation: Goal attainment [5]; Goal-effectiveness [11]; Goal attainment [14]: Trainees’ self-assessment of specific learning outcomes; Goal-directed self-regulation [15]: all outcome measures related to goal-setting, goal-attainment, and goal-evaluation. Relationship: Working alliance [5]; Generic coach-coachee relationship [5]: e.g., trust, credibility; Improved relations with others [5]. *Some variables (e.g. well-being) occur more than once as they can be classified into different categories. **Some authors view it as an affective outcome [5, 13, 17].

Coaching outcome and process variables used in the current studies

Within the category (a) reaction, a typical outcome variable is clients’ satisfaction with coaching. It is usually assessed by asking participants to indicate their subjective satisfaction on a scale [19]. In the current article, three studies report participants’ satisfaction (Studies 2a, 3b, 4a). An affective learning outcome (b) is, for example, positive and negative affect. Within coaching research, it is often assessed using the positive and negative affect schedule [PANAS, 25]. We assess positive and negative affect in Study 3b. Approach motivation also falls into this category. Approach motivation is important for following and attaining a goal set in coaching [26, 27]. It means that people are energized, capable, powerful, and determined to move toward something [28, 29]. Approach motivation can be assessed using self-reports (Studies 1 and 2b within the current article) such as “Right now, I feel energized” [28] but also using implicit measures (Studies 1, 3a, 3c within the current article). A well-established indicator of implicit approach motivation is cerebral asymmetry. Studies using electroencephalogram (EEG) found that relative left frontal activity was associated with self-reported approach motivation [30, for a review]. A behavioral measure to assess frontal activity is the line bisection task [LBT, 31]. Studies using this task [32, 33] take individuals’ biased perception to the right or left visual field when they try to mark the midpoint of horizontal lines. This reflects neural activity in the contralateral hemisphere [34]. Nash and colleagues [34] showed links between the line bisection task and state left frontal activity in EEG. Thus, the line bisection task can be used to assess situational approach-related motivation. According to the Rubicon model of action phases [35], it is important to enhance the clients’ understanding of their actual situation. This helps clients to build a strengthened motivation in order to clarify what they want and to trigger the implementation of an action [36] (Study 4b).

A typical cognitive learning outcome (c) that is often assessed in coaching research is self-efficacy (Studies 3a, 3b, 3c within the current article). It means that individuals believe that are able to master difficult situations [37]. Individuals who believe that they are self-efficient are more likely to exhibit behavior, try harder and persist in their behavior [38]. Coaching research often uses the self-efficacy scale by Jerusalem & Schwarzer [39; e.g., “When I am confronted with a problem, I can usually find several solutions”] which assesses individuals’ general expectation that they are capable of dealing with difficult situations. However, there are also studies that relate self-efficacy to a specific situation or problem [21, 40, 41]. For example, executive coaching increased executives’ self-efficacy expectations related to specific leadership competencies they considered important [41]. In our studies, we did not assess variables that fall into the categories (d) performance and skills [e.g., job performance, 42] or (e) results [e.g., individual productivity, 43] but in Study 3b we assessed one variable which can be categorized into (f) psychological well-being: self-esteem, i.e., an individual’s subjective perceived worth as a person [44]. Within the category (g) “goal-directed self-regulation”, a typical measure in coaching research is the goal attainment scale where clients identify a goal they would like to attain and then rate the degree of goal attainment [10, for an overview]. We assess goal attainment in Studies 1, 3c, and 4b. Another variable that falls within this category is goal-related motivation, including intrinsic motivation and identified regulation (Studies 3a, 3c). According to self-determination theory, motivation can be localized on a continuum of self-integration from extrinsic motivation on the one extreme to identified regulation and intrinsic motivation on the other [45–48]. If individuals identify with a behavior, feelings of autonomy increase. If people have fully integrated a behavior into their self, they act out of intrinsic motivation and feel highly autonomous, which may lead to higher goal acceptance, feelings of owning one’s goals, successful goal attainment, and well-being [48–50]. We also assessed goal commitment (Studies 3a, 3c). It is attained as soon as one has crossed the Rubicon and thus, has made a decision to work on a goal [35]. When individuals are committed to a goal, they make plans how and when they should implement an action [35]. Thus, in one Study (3c), we assessed participants’ intended time of goal initiation.

Within the category “(h) relationship”, trust is an important variable in coaching. Trust in the counselor opens the client to share and explore personal topics [51], an important prerequisite for coaching. Trust can therefore develop and thus, be seen an outcome variable [cf. 5] but it can also be seen as a process variable contributing to a good coach-coachee relationship and thus, to a successful coaching.

Two self-regulatory systems: Growth versus security

According to regulatory focus theory [RFT, 1], individuals differ in their self-regulatory systems [1, 52]. RFT distinguishes between two independent self-regulatory systems (labeled promotion and prevention) that affect the way individuals perceive the world, what information from the environment they focus on, and which strategies they prefer to pursue their goals. Higgins [1] states that promotion and prevention should not be understood as exclusive categories but rather as independent self-regulatory systems. Therefore, both promotion and prevention can be equally present. Nevertheless, individuals can differ in their expression of the promotion and prevention systems. This is called the dominant regulatory focus [1]. It arises from socialization, that is, from experience, one’s culture, and parenting. For example, for individuals with a dominant promotion focus, parenting may have placed great emphasis on encouraging the child to overcome difficulties or to be confident. The message to the child was that achievements, hopes, and ideals matter in life. For individuals with a dominant prevention focus, parental education may have placed great emphasis on alerting the child to potential dangers or on manners. The message to the child was that what matters in life is safety, a sense of responsibility, and the fulfillment of obligations [1].

Individuals with a dominant promotion focus (i.e., promoters) prefer eager advancement strategies when engaging with tasks, and they perceive change processes as opportunities for success. Promoters take risky actions, align their goals and actions to ideals, are particularly sensitive to positive and abstract information from the environment, and are driven by the need for growth. Individuals with a dominant prevention focus (i.e., preventers) prefer vigilant, cautious strategies of engaging with tasks and are keen to maintain stability. Preventers perceive possible pitfalls and failures in change processes, align their goals and actions to duties and obligations, are particularly sensitive to negative and concrete information from the environment, and are driven by the need for security [1, 53, 54].

Coaching, as well as counseling, essentially involves a process of personal growth and change [4, 6, 8]. Thus, coaching usually aims at leaving the status quo (0) to approach something new (+1), i.e., goals that the client set and develop within the coaching process. A promotion focus is also associated with a focus on approaching gains (+1), and avoiding the status quo (0), whereas a prevention focus is associated with approaching the status quo (0) and avoiding loss (-1) [54, 55]. Therefore, for individuals with a dominant promotion focus, coaching should be a natural situation, addressing their change-related focus (from 0 to +1). A promotion-related openness to change and a prevention-related preference for stability was shown in several studies. For example, individuals with a dominant promotion focus were more willing to change to a different task instead of continuing an interrupted task and were more willing to exchange an object for another object. Individuals with a dominant prevention focus were more willing to continue an interrupted task and refused to change their received objects [56]. The preventers’ preference for stability over change also fits with the finding that prevention focus is negatively related to personal values representing openness to change [i.e., self-direction and stimulation, 57].

Accordingly, we assume that coaching as a change-oriented process fits the growth-oriented promotion focus more than the security-oriented prevention focus. This should become apparent in a better evaluation of coaches and coachings in general and a higher coaching success.

H1: Clients with a higher promotion than prevention focus evaluate coaching better and report more coaching success than clients with a higher prevention than promotion focus.

Regulatory fit

Not only focus alone influences goal pursuit but also the fit between regulatory focus and strategies or situational means to reach a goal. This fit is called regulatory fit [2]. For example, a series of studies matched arguments concerning sociopolitical or health care issues to an individual’s regulatory focus [58–60]. They found that regulatory fit leads arguments to be perceived as more persuasive and increases people’s intention to act in line with the arguments’ recommendations. That is, after receiving growth- or gain-oriented arguments, promotion-focused individuals were more likely to initiate behavioral change than after receiving security- or loss-oriented arguments, whereas the opposite pattern was found for prevention-focused individuals. Moreover, when an incentive in an anagram task was framed in terms of gaining money (promotion framing) rather than in terms of losing money (prevention framing), promotion-oriented students performed better. For prevention-oriented students, the reverse was found [52]. Regulatory fit can also positively influence an individual’s motivation following feedback: Promoters showed higher motivation after positive feedback about previous successful work steps whereas preventers showed higher motivation when the feedback was based on negative indicators, such as previous errors or non-achieved targets [61]. Additionally, preventers showed more adaptive behavior and commitment towards a change when it was communicated by concentrating on the avoidance of possible mistakes rather than by concentrating on possible ways in which the change could promote professional growth [62]. A meta-analysis has shown medium effects of regulatory fit on evaluation, behavioral intention, and behavior [63]. While promotion fit compared to prevention fit showed a stronger effect on evaluation, prevention fit compared to promotion fit showed a stronger effect on behavior. Promotion focusing more on rewards may increase the value of a product and thus, the evaluation. Prevention focusing more on failures and mistakes may increase their focus on the outcomes, and thus, on the behavior [63].

Although RFT has been researched intensively, studies testing it in the context of coaching or counseling are scarce. One study indicated that a fit between a coach’s and a client’s regulatory focus may affect an individual’s performance in line with the regulatory fit hypothesis [64]. While clients generally benefited from a coach who highlighted previous partial successes and further opportunities for improvement, clients who perceived their personality traits as rather unchangeable (which indicates a prevention focus) benefitted most from a coach who highlighted previous mistakes and problems [a prevention-focused strategy; 64]. Accordingly, we suggest that if coaching is experienced as congruent with the client’s chronic regulatory focus, there will be also a positive impact on factors that are relevant to coaching. In this regard, even a preventer’s commitment towards change can be increased when the situation is congruent with his or her regulatory focus [cf 62]. In line with this, Taylor-Bianco and Schermerhorn [65] present a model in the context of leadership in which motivation to pursue change goals is predicted by regulatory fit. Although, in general a promotion focus relative to a prevention focus is related to a higher motivation to change, a prevention focus may lead to motivation to change when the change-situation requires stability. In their model they claim that prevention-oriented leaders are more likely to pursue change goals when they are in an environment of stability compared to an environment of rapid and unpredictable change.

Therefore, we hypothesize that coachings emphasizing prevention-related aspects, e.g., avoiding mistakes and risks to achieve stability and security, are more beneficial for clients with a higher prevention than promotion focus. Coachings emphasizing promotion-related aspects, i.e., exploiting opportunities and challenges to achieve growth, are more beneficial for clients with a higher promotion than prevention focus:

H2: A fit between the regulatory focus of the client and the regulatory focus of the coaching positively affects coaching success. That is, promotion-focused coaching approaches or coaching interventions are more beneficial for promotion-focused clients and prevention-focused coaching approaches or coaching interventions are more beneficial for prevention-focused clients.

Given the existing literature on the positive effects of regulatory fit in different areas, the effectiveness of a regulatory fit should exist also in coaching. However, there is little research on this topic and we are unclear about the importance of regulatory fit for coaching and about which coaching variables are particularly affected. A meta-analysis of regulatory fit including 215 studies with a total of 23,690 participants shows small to medium effects of regulatory fit on evaluation, behavioral intention, and behavior [63] and meta-analyses on coaching report small to large effect sizes of coaching on various outcomes (Fig 1). Thus, the aims of the current studies are to show the effect of regulatory fit in coaching and to figure out which outcome variables are particularly affected.

Interpersonal regulatory fit

Apart from regulatory fit developing when individual’s focus aligns with a situation or task, there is also the concept of interpersonal fit. Interpersonal fit is experienced when the regulatory foci of two individuals match. Righetti et al. [66] examined interpersonal regulatory fit during goal pursuit activities and found in six studies that promotion-oriented individuals benefitted from interpersonal fit. Thus, when they interacted with a promotion-oriented compared to a prevention-oriented partner they reported more enjoyment, a higher feeling right about their goal pursuit, and a higher motivation regarding goal pursuit. Furthermore, promotion-oriented individuals evaluated a promotion-oriented partner as more instrumental, useful, and helpful to achieve their goals than a prevention-oriented partner. Prevention-oriented individuals did not benefit from such interpersonal fit [66]. As coaching is a social interaction in which coach and coachee work together to achieve goals, we hypothesize that when there is an interpersonal regulatory fit between coach and coachee, coaching success is higher.

H3: A fit between the client’s and coach’s regulatory focus positively affects coaching success. This means that clients with a dominant promotion focus benefit most from coaches with a dominant promotion focus and clients with a dominant prevention focus benefit most from coaches with a dominant prevention focus.

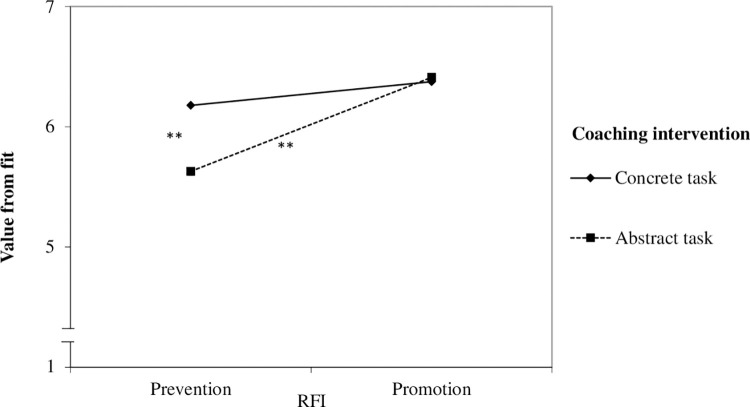

Value from fit within coaching

Regulatory fit theory [2] proposes that individuals experience a feeling right when the manner in which they pursue a goal fits their regulatory focus. The feeling-right-experience translates to an increased perceived value of what people are currently doing which is called value from fit [67–69]. As a result, self-regulatory processes are facilitated, the relevance of the information processed is increased and self-integration of the information may proceed [69, 70]. As research shows [2, 69–73], value from fit manifests in an increased inclination toward a behavior, an increased motivation to engage in a behavior, positive prospective feelings about a behavior, positive retrospective feelings about a behavior and an increased value of a behavior. This experience has been shown to mediate positive effects of regulatory fit on behavior [58]. Similarly, it can be assumed that a coaching that is in line with the client’s chronic regulatory focus feels right and thus, leads to an increased value of the coaching activity. This should in turn increase coaching success. Therefore, we hypothesize:

H4: The client’s value from fit mediates the effect of regulatory fit on coaching success.

Overview of the studies

As literature defines coaching as a change- and growth-oriented process [4, 6, 8], we first examine our hypothesis that coaching fits the growth-oriented promotion focus more than the security-oriented prevention focus. This should mean that clients with a higher promotion than prevention focus evaluate coaching better and report more coaching success than clients with a higher prevention than promotion focus (H1, Studies 1, 2, 4a).

Given the existing literature on persuasion, feeling right, fluency, and processing styles as a function of regulatory fit, the effectiveness of a regulatory fit should exist also in coaching (H2). Thus, we tested whether matching the coaching approach (Study 2) or coaching intervention (Studies 3a, 3b, 3c) with the client’s regulatory focus results in higher goal attainment and commitment, more goal-related motivation, more approach motivation, more self-efficacy, higher self-esteem, and more positive affect. As research has also shown motivational benefits of interpersonal fit regarding goal pursuit [66], we tested whether the fit between the coach’s and the client’s regulatory focus also creates benefits in coaching (H3, tested in Studies 4a and 4b). Moreover, we examined whether the mediating effect of individuals’ value from fit as already shown in regulatory fit research [67–69] can be replicated for coaching (H4, tested in Studies 2 and 3c).

Thus, the current line of studies has two aims. First, to show the benefits of regulatory fit also in the area of coaching and second, to show which coaching variables are particularly affected. All studies were approved by the University of Salzburg ethical committee.

Transparency, openness, and statistical analyses

For all studies, we describe our sampling plans, all data exclusions, all manipulations, and all measures (The measures for all studies are described in detail in S1 Table). All data and analysis codes are available at https://osf.io/f7uec/?view_only=0e25fdcbab94468aae9df807e0967f33. Materials for the studies are available by emailing the corresponding author. The studies’ designs and their analyses were not preregistered. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (version 27, IBM, Armonk, NY). Results are reported as significant when they reach a significance level of 5% and reported as “failed to reach the significance level of 5%” when they reach a significance level of 10%. For calculating Olkin’s z, we used an online calculator [74].

For all studies except of Study 4b, we used questionnaires assessing regulatory focus. Although prevention focus and promotion focus are theoretically independent, it has become common and accepted practice in previous studies to distinguish between promoters and preventers based on their regulatory focus index (RFI), which is a difference score of the two scales [promotion minus prevention score, 75, 76]. Positive values indicate a relatively higher promotion than prevention focus. Individuals with positive scores are therefore called “promoters” or “individuals high on promotion” and individuals with negative scores “preventers” or “individuals high on prevention.” Although some propose that promotion and prevention are two distinct strategies that coexist [77], others also create a difference score which gives us the opportunity of clearly distinguishing promotion-oriented from prevention-oriented individuals [62]. In our studies, we report both, the separate scales as well as the difference score. Although we are aware of the statistical and methodical implications of working with difference scores [78], for the ease of interpretation of the results, especially for the moderation analyses in Studies 3a, 3b, 3c and 4b, we use the difference score.

Study 1

In this study, we investigate the hypothesis that coaching clients with a higher promotion than prevention focus report more coaching success than coaching clients with a higher prevention than promotion focus (H1). We thereby examined data from a longitudinal coaching study consisting of five coaching sessions per client and explicit and implicit measures of coaching success.

Method

Participants

The study was part of a psychology course for master students. In this course, master psychology students received 220 hours of career coaching training according to a resource- and solution-focused career coaching concept [79]. Thus, coaches were master students who offered a career coaching with five sessions. Two hundred and seventy-one of their coaching clients filled out an online questionnaire before they participated in the coaching. As data was collected both online as well as in paper-pencil form, our sample varies according to analysis. Of the 271 coaching clients (Mage = 25.25 years, SD = 5.90; 172 female, 78 male, 21 did not indicate gender) who had completed the online regulatory focus questionnaire before the start of the first coaching session, 103 clients indicated both, their target and final goal attainment (114 indicated target goal attainment, 108 indicated final goal attainment). Of the 271 clients, 107 right-handed clients completed the implicit approach motivation before session 1 and after session 5. Of the 271 clients, 96 completed both, the baseline and final self-reported approach motivation (107 indicated baseline approach motivation and 120 indicated final approach motivation).

Since we did not perform an a-priori power analysis for this study, we ran a sensitivity analysis using G*Power [80]. With a minimum sample size of N = 103, we were able to detect an effect size of r = .24 with a power of .80, r = .26 with a power of .85, r = .28 with a power of .90, and r = .32 with a power of .95, indicating that the study had sufficient power to detect the found correlations between RFI and final goal attainment (r = .30) and RFI and implicit approach motivation (r = .26), but was underpowered to detect the found correlation between RFI and goal discrepancy (r = .19).

Procedure and measures

The coaching clients participated in five bi-weekly career coaching sessions each lasting about 1.5 hours. One week before the first coaching session, clients were sent a link to an online questionnaire assessing their regulatory focus. At the beginning of the coaching, clients provided written informed consent. Immediately before the first coaching session, we assessed clients’ implicit and self-reported approach motivation either using a paper-pencil or an online questionnaire. For clients’ implicit approach motivation, we used the line bisection task [LBT, 31]. The task involved 10 staggered horizontal lines of different length on a sheet of paper or on the computer. Participants were instructed to mark the middle of each line with a pen or the cursor. We calculated the distance of participants’ marks from the objective midpoint. Rightward errors were scored as positive values and leftward errors were scored as negative values. By averaging the scores across the 10 lines, we built the mean LBT scores with positive scores indicating relatively more rightward errors and thus approach motivation. As we were interested in people’s change in their motivational direction of behavior, we built a difference score reflecting the change from the beginning of the coaching to the end of the coaching (final-baseline approach motivation). Positive values indicate an increase in approach motivation. In line with prior research using the LBT and to control for hemispheric differences arising from handedness [81, 82], we only selected right-handed participants. During the first coaching session when clients had written down their goals, the coach asked them to indicate their target goal attainment on a scale from 1 to 10 and noted this value. At the end of the fifth session, the coach asked clients to indicate their actual goal attainment and gave them a paper-pencil questionnaire or an online questionnaire assessing their implicit and self-reported approach motivation. Clients immediately answered this questionnaire. All measures are described in detail in S1 Table. Apart from the measures used to test our main hypothesis, we included supplementary measures for additional research questions. As those measures are not part of the current research question, they are available from the authors upon request.

Results and discussion

For means, standard deviations, and correlations see Table 1.

Table 1. Means, standard deviations, and correlations for Study 1.

| Variable | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. RFI (Promotion-Prevention) | 0.03 | 0.78 | - | |||||||||||||

| 2. Promotion | 3.73 | 0.49 | .73** | - | ||||||||||||

| 3. Prevention | 3.70 | 0.54 | -.79** | -.16(*) | - | |||||||||||

| 4. Final goal attainment (after session 5) | 7.05 | 1.64 | .30** | .27** | -.20* | - | ||||||||||

| 5. Target goal attainment (session 1) | 8.09 | 1.54 | .09 | .07 | -.06 | .45** | - | |||||||||

| 6. Goal discrepancy (final—target goal attainment) | -1.09 | 1.67 | .19(*) | .21* | -.09 | .09 | -.48** | - | ||||||||

| 7. Implicit approach motivation before session 1 (baseline) | -0.43 | 1.55 | -.10 | -.08 | .07 | .16 | .17 | -.01 | - | |||||||

| 8. Implicit approach motivation after session 5 (final) | -0.18 | 1.67 | .20* | 0.22* | -.10 | .21 | .07 | .14 | .32** | - | ||||||

| 9. Implicit approach motivation difference (final-baseline) | 0.24 | 1.87 | .26** | .26** | -.15 | .06 | -.08 | .14 | .54** | .63 | - | |||||

| 10. Self-reported approach motivation before session 1 (baseline) | 3.45 | 0.65 | .20* | .33** | .01 | .19 | -.04 | .27 | .02 | .11 | .09 | - | ||||

| 11. Self-reported approach motivation "determined" before session 1 (baseline) | 3.66 | 0.97 | .19(*) | .27** | -.03 | .19 | -.01 | .22 | .07 | .11 | .05 | .65** | - | |||

| 12. Self-reported approach motivation after session 5 (final) | 4.04 | 0.76 | .18(*) | .27** | .003 | .15 | -.09 | .24(*) | -.11 | .07 | .15 | .50** | .48** | - | ||

| 13. Self-reported approach motivation "determined" after session 5 (final) | 4.19 | 0.79 | .07 | .15 | .05 | .08 | -.16 | .21 | -.15 | -.04 | .08 | .44** | .42** | .76** | - | |

| 14. Self-reported approach motivation difference (final-baseline) | 0.57 | 0.81 | .04 | -.002 | -.06 | -.02 | -.11 | .11 | -.16 | -.001 | .12 | -.43** | -.05 | .66** | .42** | - |

| 15. Self-reported approach motivation "determined" difference (final-baseline) | 0.52 | 1.01 | -.09 | -.13 | .02 | -.15 | -.14 | -.03 | -.23* | -.14 | .05 | -.24* | -.66** | .20 | .44** | .39** |

(*) p < .10

* p < .05

** p < .01

Descriptives

At the end of the coaching, individuals attained a mean goal attainment value of M = 7.05. There was still a mean discrepancy to their target goal attainment of M = 8.09, indicating that in total, clients did not fully attain their goals. As clients’ implicit approach motivation was more negative at the beginning of the coaching (baseline: M = -0.43) than at the end (final: M = -0.18), and their self-reported approach motivation was lower at the beginning (baseline: M = 3.45/3.66) than at the end of the coaching (baseline: M = 4.04/4.19), the results suggest that there was an increase in approach motivation.

Correlations

Regarding goal attainment, the correlations between RFI and the target goal attainment score were non-significant, indicating that promoters did not set themselves higher goals than preventers (see Table 1, for the exact values). We found a significant positive correlation between RFI and final goal attainment, r(106) = .30, p = .001, indicating that a higher promotion than prevention focus was associated with higher goal attainment at the end of the coaching. Olkin’s z for the comparison between the correlations of promotion and prevention with goal attainment (promotion: r(106) = .27, p = .004; prevention: r(106) = -.20, p = .042) shows a significant difference, z = 3.44, p < .001, hinting at a promotion focus being associated with higher goal attainment than a prevention focus. The correlation of RFI with the goal discrepancy was at the border of the significance level of 5%, r(101) = .19, p = .050. Olkin’s z for the comparison between the correlations of promotion and prevention with the goal attainment score (promotion: r(101) = .21, p = .031; prevention: r(101) = -.09, p = .354) shows a significant difference, z = 2.06, p = .020, hinting at a promotion focus being associated with lower goal discrepancy than a prevention focus.

Regarding implicit approach motivation, we first checked whether a higher promotion than prevention focus was associated with more approach motivation already at the beginning of the coaching. The correlations of RFI with the baseline score of implicit approach motivation were non-significant, indicating that in the beginning of the coaching, promoters had not been more approach motivated than preventers (see Table 1, for the exact values). The correlations of RFI with final approach motivation, r(105) = .20, p = .037 and with the difference score (final-baseline approach motivation) were significant, r(105) = .26, p = .006, indicating that a higher promotion than prevention focus was associated with more implicit approach motivation at the end of the coaching and with more increase in approach motivation. Olkin’s z for the comparison between the correlations of promotion and prevention with the final approach motivation showed a significant difference (promotion: r(105) = .22, p = .026; prevention: r(105) = -.10, p = .316), z = 2.25, p = .012, and also the correlations of promotion and prevention with the difference score showed a significant difference (promotion: r(105) = .26, p = .007; prevention: r(105) = -.15, p = .133), z = 2.94, p = .002. Thus, a promotion focus seems to be associated with more approach motivation than a prevention focus.

Regarding self-reported approach motivation, we first checked whether a higher promotion than prevention focus was associated with more self-reported approach motivation already at the beginning of the coaching. The correlations of RFI with the baseline score of self-reported approach motivation were significant (self-reported approach motivation before session 1 (baseline): r(105) = .20, p = .041; self-reported approach motivation "determined" before session 1 (baseline): r(105) = .19, p = .050), indicating that in the beginning of the coaching, promoters reported more approach motivation than preventers.

Regarding the final self-reported approach motivation, the positive correlation between RFI and final approach motivation failed to reach the significance level of 5%, r(118) = .18, p = .056. Olkin’s z for the comparison between the correlations of promotion and prevention with the final approach motivation showed a significant difference (promotion: r(118) = .27, p = .003; prevention: r(118) = .003, p = .977), z = 1.99, p = .023, indicating that a promotion was associated with more self-reported approach motivation at the end of the coaching than prevention. The correlation between RFI and the single item “determined” at the end of session 5 was not significant, r(118) = .07, p = .482. The correlations of RFI with the difference scores were not significant (self-reported approach motivation difference and self-reported approach motivation "determined" difference, see Table 1).

Summarized, there were significant positive correlations of RFI with final goal attainment and the goal discrepancy score, and final implicit approach motivation and the increase in implicit approach motivation from the start to the end of the coaching. Thus, regarding these variables, individuals scoring high on promotion may benefit more from coaching than individuals high on prevention. However, for final and the increase in self-reported approach motivation, the correlations did not reach significance. Here, the baseline scores were significantly correlated with RFI, indicating that promoters felt more energized, powerful, capable, goal-focused, and determined than preventers right away. This is in contrast to the non-significant correlation of RFI with baseline implicit approach motivation. The two approach motivation measures may thus reflect distinct constructs, especially since they do not correlate with each other (see Table 1). We address this issue in the general discussion.

The findings partly support H1 such that regarding goal attainment and having an implicit “impulse to move toward” [30, p 292], people scoring high on promotion benefit more from coaching than people high on prevention. For self-reported approach motivation, the results did not show significance.

Correction for multiple comparisons

As for our hypothesis H1, we test four dependent variables, i.e., goal attainment, implicit approach motivation, self-reported approach motivation, self-reported approach motivation “determined”, we performed an alpha correction for multiple comparisons. Controlling for the family-wise error rate, we applied the Bonferroni correction with an alpha level of .05 and four tests. This results in a corrected alpha level of p = .013. Interpreting the findings with the corrected alpha level, only the correlation of RFI with the implicit approach motivation difference and final goal attainment remains.

Study 2

As Study 1 partly shows that coaching fits promoters more than preventers, we further test this hypothesis in Study 2. We examine whether individuals are in general more interested in coaching than prevention-oriented individuals, resulting in a better evaluation of coachings (H1). Next, we investigate the hypothesis that a fit between the client’s regulatory focus and the regulatory focus of the coaching positively affects the individuals’ evaluation of coachings (H2). In Study 2, participants read the descriptions of three coachings–a promotion-oriented, a prevention-oriented, or a neutral coaching–and evaluated them by indicating their satisfaction with the coachings, their approach motivation, and their value from fit regarding the coachings. Research suggests that individuals derive value from regulatory fit, a corollary of increased hedonic experience and thus, feeling right about what one is currently engaged in [58, 67–69]. Further, value derived from regulatory fit may result in increased relevance and amplified value regarding the information processed [69, 70, 83]. Thus, we investigated whether people’s experience of value from fit mediate the effect of regulatory focus on people’s satisfaction with the coaching offers (H4).

Method

Participants

To determine the minimum sample size required to test our fit-hypothesis (H2), we conducted an a priori power analysis using G*Power [80]. Results indicated that for detecting a small to medium effect (r = .25) and achieving a power of 80% at α = .05, the required sample size was N = 97. We obtained a sample size of 99 German-speaking participants who were interested in coaching (41 females and 53 males, 5 did not indicate their gender). They were recruited for an online study via personal contacts. In terms of profession, the sample was very heterogeneous with participants working in sectors such as production, health, information and communication, or service providers. Participants’ age ranged from 18 to 70 years with Mage = 37.15 years (SD = 14.41).

Procedure and measures

After filling out a measure for the regulatory focus trait questionnaire, participants were instructed to imagine being offered coaching for personnel development. Then, participants could choose one out of five topics matching their actual professional situation. The topics were management responsibility, a new position, self-reflection, leadership, and personal development. They were shortly described. Based on their topic choice, they were presented with the description of three coachings—a promotion-oriented coaching, a prevention-oriented coaching, and a neutral coaching. The different coachings were presented in randomized order. Please see S1 File for a coaching example. Then, participants were asked to indicate their self-reported approach motivation and their satisfaction regarding the three coachings. As a mediator variable, we assessed individuals’ value from fit. Conceptually following Latimer et al. [58] and adapting their approach to the coaching context, we constructed 5 items, with each item measuring one of the aspects: inclination towards participating in the coaching (i.e., “Participating in this coaching will give me joy”), motivation to participate in the coaching (i.e., “I’m motivated to participate in this coaching”), positive prospective feelings about participation in the coaching (i.e., “It will feel good to participate in this coaching”), as well as positive retrospective feelings about participation in the coaching (i.e., “Once I have participated in the coaching, I will feel positive about it”) and perceived value of the participation in the coaching (i.e., “The participation in the coaching is valuable to me”). In addition, we integrated the item “It feels right to participate in this coaching” into the scale [e.g., 68]. Finally, they answered demographic questions. All measures are described in detail in S1 Table.

Results

For means, standard deviations, and correlations see Table 2.

Table 2. Means, standard deviations, and correlations for Study 2.

| Variable | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. RFI (Promotion-Prevention) | 0.14 | 1.25 | - | ||||||||||||||

| 2. Promotion | 5.32 | 0.84 | .70** | - | |||||||||||||

| 3. Prevention | 5.18 | 0.89 | -.74** | -.04 | - | ||||||||||||

| 4. Satisfaction (all coachings) | 5.37 | 1.15 | .21* | .30** | -.01 | - | |||||||||||

| 5. Satisfaction (Promotion coaching) | 5.56 | 1.43 | 0.20* | .27** | -.03 | .66** | - | ||||||||||

| 6. Satisfaction (Prevention coaching) | 5.14 | 1.60 | 0.14 | .27** | .06 | .77** | .21* | - | |||||||||

| 7. Satisfaction (Neutral coaching) | 5.40 | 1.57 | 0.14 | .14 | -.06 | .81** | .32** | .48** | - | ||||||||

| 8. Value from fit (all coachings) | 5.15 | 1.20 | .19(*) | .31** | .03 | .91** | .57** | .71** | .76** | - | |||||||

| 9. Value from fit (Promotion coaching) | 5.39 | 1.32 | .25* | .30** | -.07 | .63** | .87** | .23* | .35** | .70** | - | ||||||

| 10. Value from fit (Prevention coaching) | 4.82 | 1.68 | .07 | .27** | .15 | .74** | .22* | .90** | .49** | .81** | .31** | - | |||||

| 11. Value from fit (Neutral coaching) | 5.23 | 1.59 | .14 | .16 | -.04 | .78** | .34** | .47** | .91** | .84** | .43** | .52** | - | ||||

| 12. Approach motivation—"determined" (all coachings) | 5.27 | 1.21 | .19(*) | .35** | .07(*) | .88** | .62** | .68** | .69** | .86** | .61** | .71** | .68** | - | |||

| 13. Approach motivation—"determined" (Promotion coaching) | 5.43 | 1.57 | .26** | .32** | -.07 | .47** | .82** | .10 | .18(*) | .46** | .82** | .15 | .20(*) | .63** | - | ||

| 14. Approach motivation—"determined" (Prevention coaching) | 4.98 | 1.83 | .05 | .22* | .13 | .70** | .23* | .88** | .42** | .70**** | .27** | .91** | .41** | .77** | .20(*) | - | |

| 15. Approach motivation—"determined" (Neutral coaching) | 5.39 | 1.65 | .10 | .21* | .06 | .71** | .31** | .40** | .87** | .67** | .27** | .43** | .85** | .74** | .22* | .38** | - |

(*) p < .10

* p < .05

** p < .01

To test H1, hypothesizing that a higher promotion than prevention focus is associated with a better evaluation of coachings, we averaged the responses for the scales approach motivation and satisfaction over the promotion, the prevention, and the neutral coachings. There was a significant positive correlation between RFI and satisfaction, r(99) = .21, p = .037, indicating that a higher promotion than prevention focus was associated with more satisfaction with coaching. The correlation between RFI and approach motivation did not reach the significance level of 5%.

For the fit-hypothesis H2, RFI shows significant positive correlations with people’s self-reported approach motivation, r(97) = .26, p = .009, their satisfaction with the promotion coachings, r(97) = .20, p = .049, and their value from fit regarding the promotion coachings, r(97) = .25, p = .013, i.e. higher scores on RFI (i.e., higher promotion than prevention focus) are associated with more approach motivation, more satisfaction, and more value from fit regarding the promotion coachings and vice versa for lower scores on RFI. The correlations of RFI with the prevention and neutral coachings are not significant. Olkin’s z for the comparison between the correlations of RFI with the promotion coachings and RFI with the prevention coachings show a significant difference in approach motivation, z = 1.70, p = .044, indicating that a heightened promotion focus seems to be associated with more and a heightened prevention focus with less approach motivation. However, the comparisons failed to reach significance on value from fit, z = 1.57, p = .05961, and satisfaction, z = 0.49, p = .314.

Looking at the correlations of the separate promotion and prevention scores with the dependent variables, a high promotion focus is positively correlated with satisfaction, approach motivation, and feeling right regarding the promotion coaching as well as the prevention coachings and even with approach motivation for the neutral coaching. Thus, individuals scoring high on promotion seem to be satisfied with all kinds of coaching. There were no significant correlations between prevention and the dependent variables.

Correction for multiple comparisons

As for our hypothesis H2, we test three dependent variables, i.e., satisfaction, value from fit, and self-reported approach motivation, we performed an alpha correction for multiple comparisons. Controlling for the family-wise error rate, we applied the Bonferroni correction with an alpha level of .05 and three tests. This results in a corrected alpha level of p = .017. Interpreting the findings with the corrected alpha level, the significant correlations of RFI with people’s approach motivation and their value from fit regarding the promotion coaching remain but the correlation of RFI with satisfaction with the promotion coaching disappears.

Mediation

Investigating H4 hypothesizing that value from fit regarding the coaching mediates the fit between the client’s regulatory focus and the regulatory orientation of the coaching on coaching success, we performed a mediation analysis using the software PROCESS 3.4.1 [84, model 4]. As there were significant correlations of RFI with promotion coachings but not with prevention or neutral coachings, we performed the mediation only for the promotion coachings. The criterion for detecting a mediation was a significant indirect effect which was computed using a 95% bias-corrected bootstrap confidence interval (95% BC CI) and 10,000 bootstrap samples. Regression analyses revealed that RFI had significant total effects on satisfaction with the promotion coachings, b = .23, SE = .11, t(97) = 1.99, p = .049, and on self-reported approach motivation regarding the promotion coachings, b = .33, SE = .13, t(97) = 2.67, p = .009. The effects decreased to non-significance when the mediator value from fit had been added to the predictions, b = -0.02, SE = .06, t(97) = -0.41, p = .686 (for satisfaction), b = 0.08, SE = .08, t(97) = 1.01, p = .314 (for approach motivation). RFI positively affected the mediator value from fit, b = 0.26, SE = .10, t(97) = 2.54, p = .013. The mediator value from fit positively affected satisfaction with the promotion coachings, b = 0.96, SE = .07, t(97) = 13.36, p < .001, and approach motivation regarding the promotion coachings, b = 0.96, SE = .06, t(97) = 17.00, p < .001. The bootstrapped indirect effects of RFI via value from fit was significant for satisfaction with the promotion coachings, b = 0.25, SE = .12, BC CI [0.01, 0.48] and for approach motivation regarding the promotion coachings, b = 0.25, SE = .12, BC CI [0.01, 0.47]. In sum, the perception of value from fit fully mediated satisfaction and approach motivation regarding the promotion coachings for individuals with a more pronounced promotion focus.

Discussion

Summarized, in Study 2 we found that promotion-focused clients are more satisfied with coaching in general than prevention-focused clients, providing support for H1. Considering regulatory fit, a higher promotion than prevention focus (RFI) is associated with a higher satisfaction with the promotion coaching and in addition with heightened approach motivation and a value from fit regarding promotion coaching and vice versa for a higher prevention than promotion focus. This result only partially provides support for H2 as we did not find significant correlations of RFI with the prevention coachings. Value from fit mediated the promoters’ satisfaction and approach motivation regarding the promotion coaching. As we did not find a mediation for individuals with a more pronounced prevention focus, the result only partly supports H4.

Study 2 shows small effects only for promoters. While there were correlations of a more pronounced promotion than prevention focus with satisfaction and “determination” regarding a promotion coaching, there were no correlations with prevention coachings or neutral coachings. The promotion fit effects were mediated by promoters’ increased value from fit regarding promotion coachings. However, the vignette-based approach is certainly a critical issue that we discuss in the general discussion section.

In summary, looking at the results of Study 2, one can cautiously say that for offering coachings, the regulatory focus should be considered because fit effects can better explain people’s attitudes and motivation regarding a coaching than a general evaluation of coachings. This is in line with a study revealing fit effects in the context of job offers. Here, promoters were more attracted by job offers containing the promotion-related value autonomy at work and preventers were more attracted by job offers containing the prevention-related value security at work [85]. We find similar fit effects in our study but only for promoters. But is there also a way to establish a regulatory fit in coaching? We investigate this question in the next three studies by exploring the effect of promotion- or prevention-versions of established coaching interventions (Studies 3a, 3b, 3c).

Study 3a

In this study, we focused on the action planning phase of a coaching process which typically takes place at an early stage in the coaching process. We created an intervention using growth- or security-oriented goal-setting strategies. We hypothesized that promotion-focused coaching clients benefit more from identifying promotion-oriented action strategies to reach their goal and prevention-focused coaching clients benefit more from identifying prevention-oriented action strategies to reach their goal.

Method

Participants

To determine the minimum sample size required to test our fit-hypothesis (H2), we conducted an a priori power analysis using G*Power [80]. Results indicated that for detecting a small to medium effect (f2 = .10) and achieving a power of 80% at α = .05, the required sample size was N = 81. We obtained a sample size of 120 German-speaking participants (80 females and 40 males) who were recruited for an online study via university newsletters, social networks, or personal contacts. The survey language was German. Participants’ age ranged from 16 to 64 years with Mage = 25.78 years (SD = 7.52). Students in the sample received course credit in exchange for their participation. Participants were randomly assigned to either the promotion (n = 56) or prevention coaching intervention (n = 64).

Procedure and measures

At the beginning of the study, participants answered the regulatory focus questionnaire and were asked to write down a personal goal they would like to attain in the next 4 weeks. This was followed by an explanation of the SMART method of goal setting, which is a coaching technique used to properly define and operationalize goals [86]. It was at this point that the actual manipulation took place. In the promotion coaching intervention, participants were asked to identify promotion-oriented action strategies to reach their goal, whereas in the prevention coaching intervention participants were asked to identify prevention-oriented action strategies to reach their goal. The instructions were as follows:

Promotion coaching intervention: “Now try to describe the goal you defined before in accordance with the SMART criteria. Then think about which actions are necessary to reach your goal. Please list at least three actions and describe them briefly.”

Prevention coaching intervention: “Now try to describe the goal you defined before in accordance with the SMART criteria. Then think about which actions you should definitely avoid reaching your goal. Please list at least three actions and describe them briefly.”

After working on the coaching intervention, participants completed the LBT to assess approach motivation. They filled out a questionnaire assessing self-efficacy, goal-related motivation, and goal commitment before finishing the survey with another LBT and a set of demographic questions. All measures are described in detail in S1 Table.

Statistical analysis

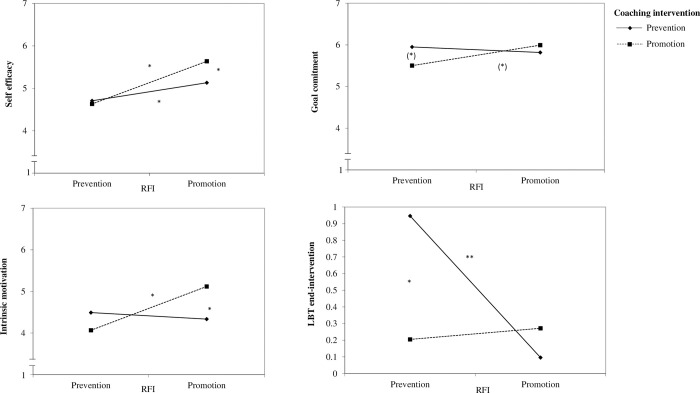

To test H2b we used moderated regression analyses of the SPSS macro PROCESS with a 95% bias-corrected bootstrap confidence interval (95% BCCI) and 10,000 bootstrap samples [84, model 1]. We used the coaching intervention condition (coded with prevention = 0, promotion = 1) as an independent variable and people’s RFI as a moderator variable. For significant results, follow-up simple slope analyses are investigated using the conditional effect of the intervention condition on the dependent variables for promoters (+1 SD of RFI, i.e., dominant promotion focus) and preventers (–1 SD of RFI, i.e., dominant prevention focus). See Table 3 for the estimates and Fig 2 for the interaction effects.

Table 3. Estimates for RFI, the intervention and their interaction for Study 3a.

| Variable | R2 | Predictor | b | Lower 95% CI | Upper 95% CI | SE | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-efficacy | .20 | |||||||

| RFI | 0.19 | 0.03 | 0.35 | 0.08 | 2.30 | .023 | ||

| Intervention | 0.23 | -0.07 | 0.52 | 0.15 | 1.53 | .129 | ||

| R2 change: .02 | RFI x Intervention | 0.26 | -0.02 | 0.53 | 0.14 | 1.86 | .066 | |

| Intrinsic motivation | .05 | |||||||

| RFI | -0.07 | -0.38 | 0.25 | 0.16 | -0.41 | .680 | ||

| Intervention | 0.21 | -0.36 | 0.77 | 0.29 | 0.72 | .475 | ||

| R2 change: .03 | RFI x Intervention | 0.54 | 0.01 | 1.07 | 0.27 | 2.03 | .044 | |

| Identified regulation | .01 | |||||||

| RFI | 0.06 | -0.15 | 0.26 | 0.11 | 0.53 | .598 | ||

| Intervention | 0.04 | -0.41 | 0.33 | 0.19 | -0.23 | .823 | ||

| R2 change: .001 | RFI x Intervention | 0.07 | -0.28 | 0.42 | 0.18 | 0.41 | .685 | |

| Goal commitment | .03 | |||||||

| RFI | -0.06 | -0.25 | 0.13 | 0.10 | -0.65 | .518 | ||

| Intervention | 0.12 | -0.46 | 0.22 | 0.17 | -0.69 | .495 | ||

| R2 change: .025 | RFI x Intervention | 0.28 | -0.04 | 0.60 | 0.16 | 1.74 | .085 | |

| Implicit approach motivation | .08 | |||||||

| RFI | -0.38 | -0.65 | -0.11 | 0.14 | -2.75 | .007 | ||

| Intervention | -0.26 | -0.74 | 0.22 | 0.24 | -1.08 | .282 | ||

| R2 change: .03 | RFI x Intervention | 0.41 | -0.05 | 0.86 | 0.23 | 1.78 | .078 |

Significant effects at p < 0.05 and effects that reached a significance level of p < 0.10 are in bold. Coding of coaching intervention: 0 = prevention, 1 = promotion.

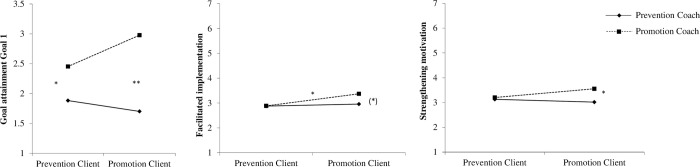

Fig 2. Interaction effects of RFI and coaching intervention on the dependent variables in Study 3a.

(*) p < .10; * p < .05; ** p < .01.

Results

Self-efficacy

The results revealed a significant main effect of RFI, indicating that overall people high on promotion showed more self-efficacy than people high on prevention. Although the interaction between RFI and the coaching intervention failed to reach the significance level of 5%, simple slopes indicate that promoters (p = .017) indicated higher self-efficacy when they received the promotion relative to the prevention intervention but for preventers (p = .760) the promotion or prevention intervention did not make a difference.

Goal-related motivation

For intrinsic motivation, there was a significant interaction between RFI and coaching intervention. Simple slopes showed that promoters (p = .054) indicated higher intrinsic motivation when they received the promotion relative to the prevention intervention but for preventers (p = .329) the promotion or prevention intervention did not make a difference. For identified regulation, there were no significant effects.

Goal commitment

The interaction between RFI and coaching intervention failed to reach the significance level of 5%. Simple slopes revealed that for promoters (p = .480) the promotion or prevention intervention did not make a difference but preventers (p = .090) indicated more goal commitment when they received the prevention relative to the promotion intervention. Thus, there is some evidence that regulatory focus moderates the relationship of the intervention and goal commitment with preventers showing stronger goal commitment when they received the prevention relative to the promotion intervention.

Implicit approach motivation

We included the mean handedness quotient as a covariate in our analyses. The results revealed a significant main effect of RFI, indicating that overall people high on promotion showed lower increase in approach motivation than people high on prevention. The interaction between RFI and coaching intervention for people’s approach motivation failed to reach the significance level of 5%. However, simple slopes revealed that for promoters (p = .660) the promotion or prevention intervention did not make a difference but preventers (p = .046) had an increase in approach motivation when they received the prevention relative to the promotion intervention.

Correction for multiple comparisons

As for our hypothesis H2, we test five dependent variables, we performed an alpha correction for multiple comparisons. Controlling for the family-wise error rate, we applied the Bonferroni correction with an alpha level of .05 and five tests. This results in a corrected alpha level of p = .001. Interpreting the findings with the corrected alpha level, all of the significant interactions of RFI with intervention disappear.

Discussion

In Study 3a we tested the regulatory fit hypothesis in relation to different goal setting strategies in the action planning phase of a coaching. Although interaction effects between coaching intervention and people’s regulatory focus were not all p < .05, the results of this study provide some, although weak, empirical support for H2, i.e., the idea of the applicability of the regulatory fit effect regarding coaching techniques. Specifically, we found that for self-efficacy and intrinsic motivation, individuals with a more pronounced promotion focus benefit from a regulatory fit–they indicate higher self-efficacy and more intrinsic motivation when they receive a goal-setting intervention that focuses on promotion-related actions. When asked to record avoidance strategies during goal setting, perceived self-efficacy as well as intrinsic motivation decline. For individuals with a more pronounced prevention focus our results are rather equivocal, with no effect for self-efficacy and intrinsic motivation, only a marginal effect for goal commitment, but a significant effect for implicit approach motivation. Thus, preventers may benefit from a regulatory fit on an implicit level–they show more positive values on our measure for approach motivation when they receive an intervention that focuses on prevention-related actions. However, the missing results for preventers’ intrinsic motivation or self-efficacy again raise the question introduced earlier, as to whether coaching by its very nature better fits the motivational orientation of promoters, based on change and growth, than that of change-reluctant preventers.

Yet, following the regulatory fit hypothesis, we still believe that motivational congruency can compensate for the presumed disadvantages of a prevention focus. Some researchers emphasize the need for more follow-up assessments in coaching studies to obtain a more holistic picture of the effects and their durability [87, 88]. That is, for some clients, coaching benefits might only appear after a specific time required to cognitively process the intervention and its implications have elapsed. This led us to conduct another coaching study, measuring time-delay effects.

Study 3b

In this study, we instructed participants to reflect upon goal-relevant personal resources, directed towards serving either growth or security needs and investigated immediate, as well as time-delayed regulatory fit effects. We hypothesized that promotion-focused coaching clients benefit more from identifying personal energy-givers and that prevention-focused coaching clients benefit more from identifying personal energy-takers.

Method

Participants

Based on an a priori power analysis requiring a minimum sample size of N = 81 (see Study 3a), a total of 85 German-speaking participants was recruited for this online study via university newsletters, social networks, or personal contact. The language of the survey was German. Three participants were eliminated due to neglecting to work on the coaching intervention. Participants were randomly assigned to the promotion (n = 42) or prevention coaching intervention (n = 43). There was an exploratory third condition, the prevention-plus-affirmation condition (n = 37), not part of the main analysis. For further information, please contact the first author. The participants’ age ranged from 18 to 53 years with Mage = 24.32 years (SD = 6.37) and a gender distribution of 70 females and 15 males. Of the 85 individuals participating in Stage 1 of the study, 57 returned to attend Stage 2 of the study, 1 week later. Students in the sample received course credit in exchange for their participation. Grubbs’ outlier testing led to the exclusion of one participant for the analysis of self-efficacy.

Procedure and measures

In Stage 1 of the study, participants’ regulatory focus and baseline measures of state self-esteem, self-efficacy, positive and negative affect (t1) were assessed. Then, we applied the respective version of the coaching intervention “energy-map”, which is used in coaching sessions to help clients reflect upon personal resources in different areas of their life [89]. In this application, areas are listed separately and include friends/social contacts, romantic relationships, self, leisure time, family, job/studies, and an additional area free of choice. Whereas the original version of the energy map aims to identify both “energy-givers” and “energy-takers” in the respective areas, for purposes of our study we deconstructed the map into two separate versions, which served as the underlying manipulation.

In the promotion version of the intervention, participants were asked to reflect upon and write down personal energy-givers in their areas of life (i.e., friends, partnership, self, leisure time, the family of origin, academic/professional context, and an open free-choice category). On a little side note, they were given a set of exemplary ideas on which aspects to focus on. Aside from nine shared aspects (e.g., goals, feelings, thoughts, tasks, activities, relationships, social contacts, beliefs, environment), there were also two promotion-specific aspects: performances and creations. In the prevention version, participants were asked to reflect upon and write down personal energy-takers in their areas of life. They were given the same set of shared aspects listed above and further, two unshared prevention-specific aspects to focus on: obligations and responsibilities.

Apart from these major differences, both versions of the coaching intervention shared the same underlying storyline, namely that becoming aware of their resources can support them in better implementing their goals. After working on the respective coaching intervention, participants filled out questionnaires assessing state self-esteem, self-efficacy, and positive and negative affect (t2) for a second time, before finishing Stage 1 of the study with a set of demographic questions. One week later, at Stage 2 of the study, state self-esteem, self-efficacy, and positive and negative affect were assessed for a third time (t3), together with satisfaction with coaching. For all variables assessed three times (t1, t2, t3), we built difference scores reflecting the change from t1 to t2 and from t1 to t3. All measures are described in detail in S1 Table.

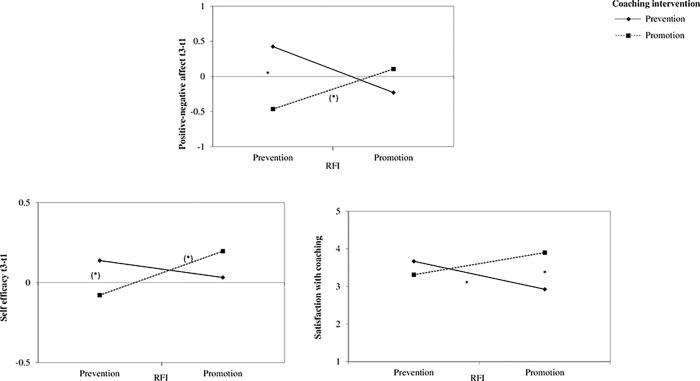

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were the same as in Study 3a. See Table 4 for the estimates and Fig 3 for the interaction effects.

Table 4. Estimates for RFI, the intervention and their interaction for Study 3b.

| Variable | R2 | Predictor | b | Lower 95% CI | Upper 95% CI | SE | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-esteem t2-t1 | .06 | |||||||

| RFI | -0.07 | -0.15 | 0.01 | 0.04 | -1.73 | .088 | ||

| Intervention | 0.17 | 0.01 | 0.33 | 0.08 | 2.15 | .035 | ||

| R2 change: .03 | RFI x Intervention | 0.11 | -0.02 | 0.23 | 0.06 | 1.65 | .103 | |

| Self-esteem t3-t1 | .01 | |||||||

| RFI | -0.03 | -0.16 | 0.10 | 0.07 | -0.47 | .643 | ||

| Intervention | 0.004 | -0.30 | 0.31 | 0.15 | 0.03 | .981 | ||

| R2 change < .001 | RFI x Intervention | -0.004 | -0.25 | 0.24 | 0.12 | -0.04 | .972 | |

| Self-efficacy t2-t1 | .06 | |||||||

| RFI | -0.002 | -0.06 | 0.05 | 0.03 | -0.07 | .955 | ||

| Intervention | 0.07 | -0.03 | 0.18 | 0.05 | 1.43 | .155 | ||

| R2 change: .03 | RFI x Intervention | 0.07 | -0.02 | 0.15 | 0.04 | 1.63 | .107 | |

| Self-efficacy t3-t1 | .10 | |||||||

| RFI | -0.05 | -0.14 | 0.04 | 0.05 | -1.09 | .279 | ||

| Intervention | 0.10 | -0.11 | 0.30 | 0.10 | 0.96 | .340 | ||

| R2 change: .08 | RFI x Intervention | 0.18 | 0.02 | 0.34 | 0.08 | 2.19 | .033 | |

| Affect t2-t1 | .04 | |||||||

| RFI | -0.12 | -0.35 | 0.11 | 0.11 | -1.04 | .300 | ||

| Intervention | 0.36 | -0.09 | 0.8 | 0.22 | 1.60 | .113 | ||

| R2 change: .003 | RFI x Intervention | 0.09 | -0.27 | 0.44 | 0.18 | 0.48 | .635 | |

| Affect t3-t1 | .10 | |||||||

| RFI | -0.31 | -0.65 | 0.04 | 0.17 | -1.78 | .081 | ||

| Intervention | 0.13 | -0.67 | 0.93 | 0.40 | 0.32 | .750 | ||

| R2 change: .06 | RFI x Intervention | 0.58 | -0.05 | 1.22 | 0.32 | 1.84 | .071 | |

| Satisfaction with coaching | .12 | |||||||

| RFI | -0.35 | -0.67 | -0.04 | 0.16 | -2.25 | .029 | ||