Abstract

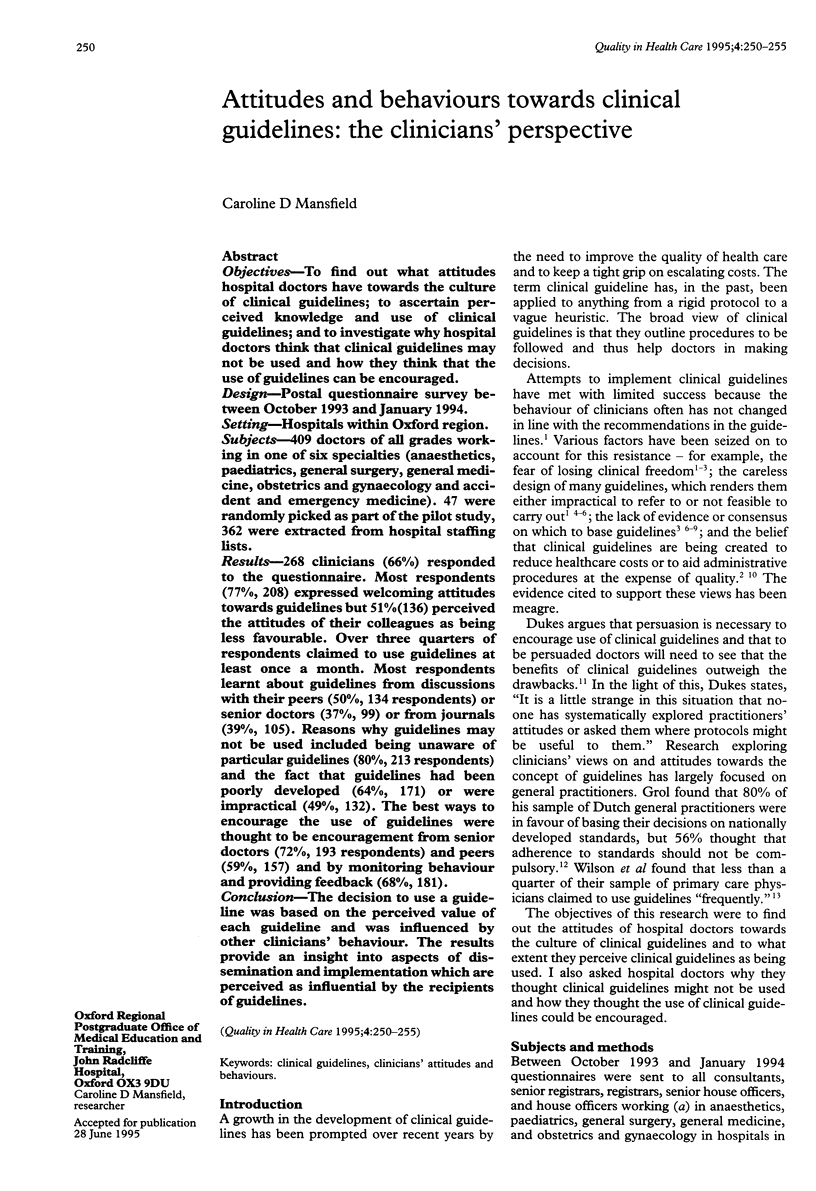

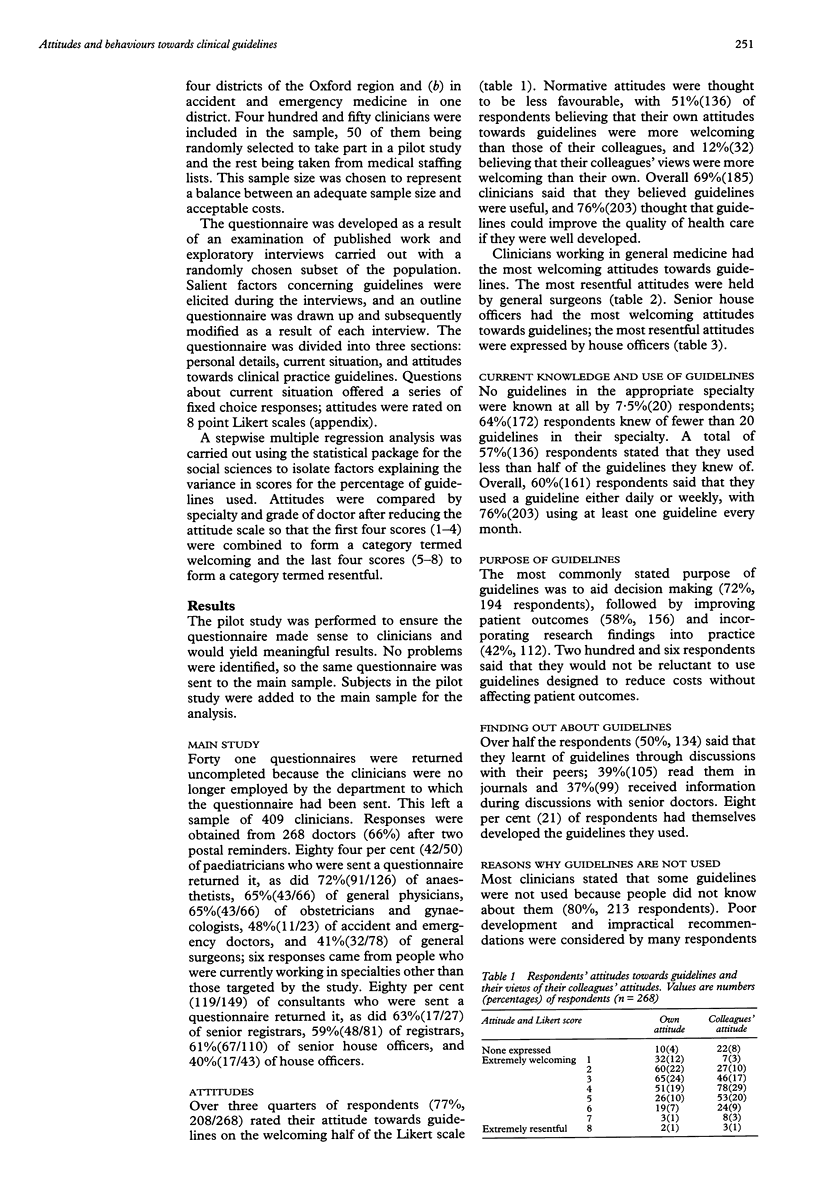

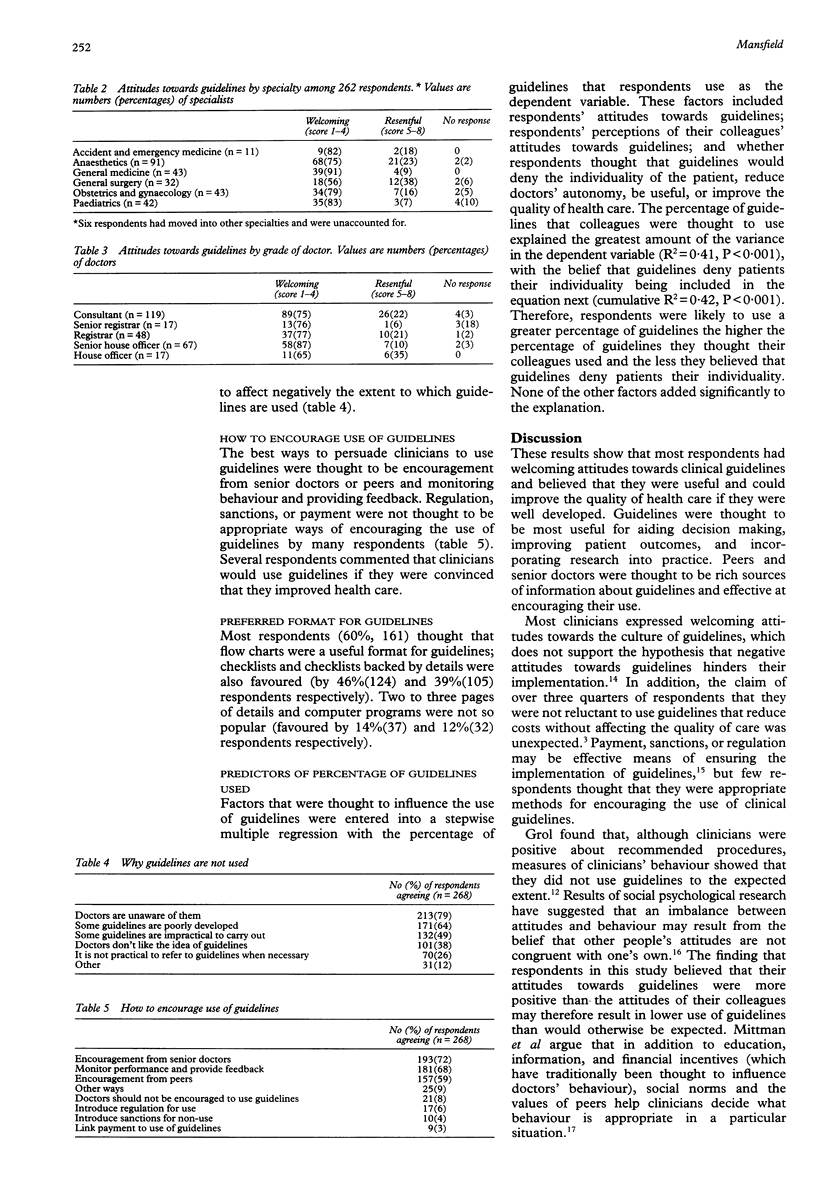

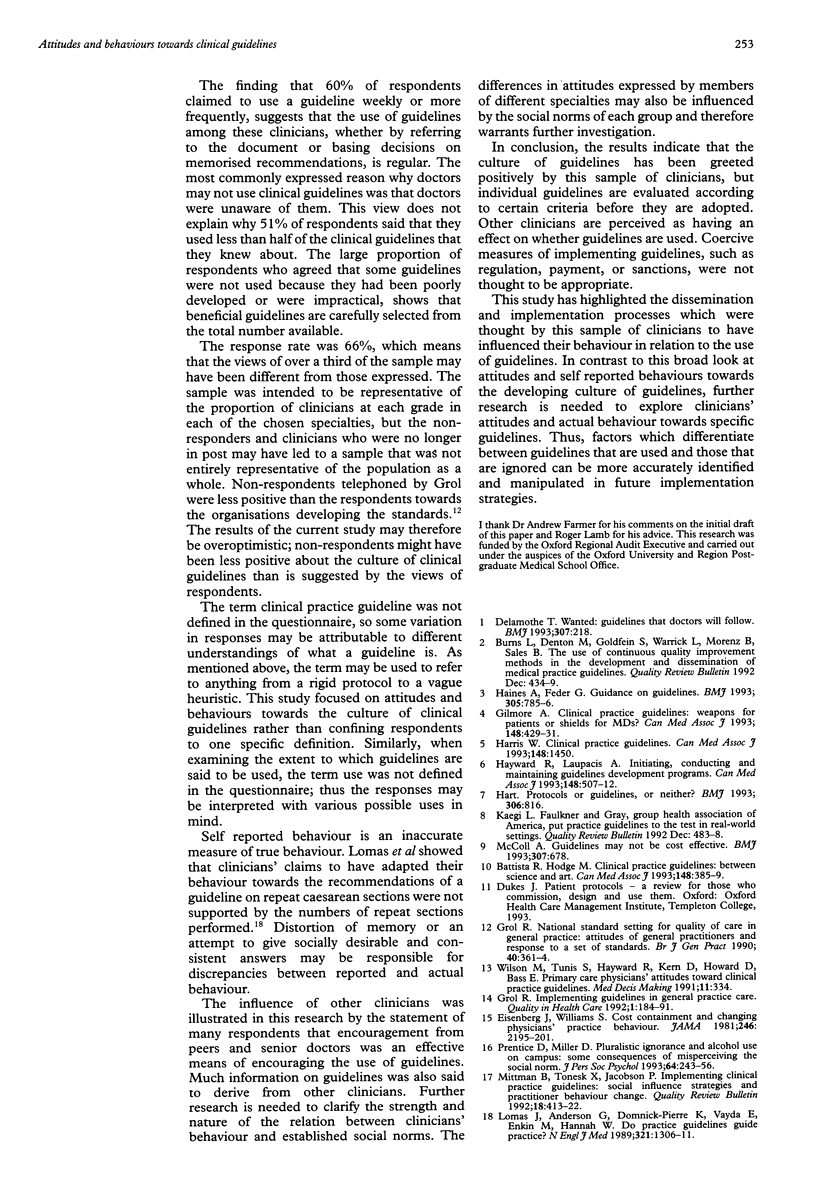

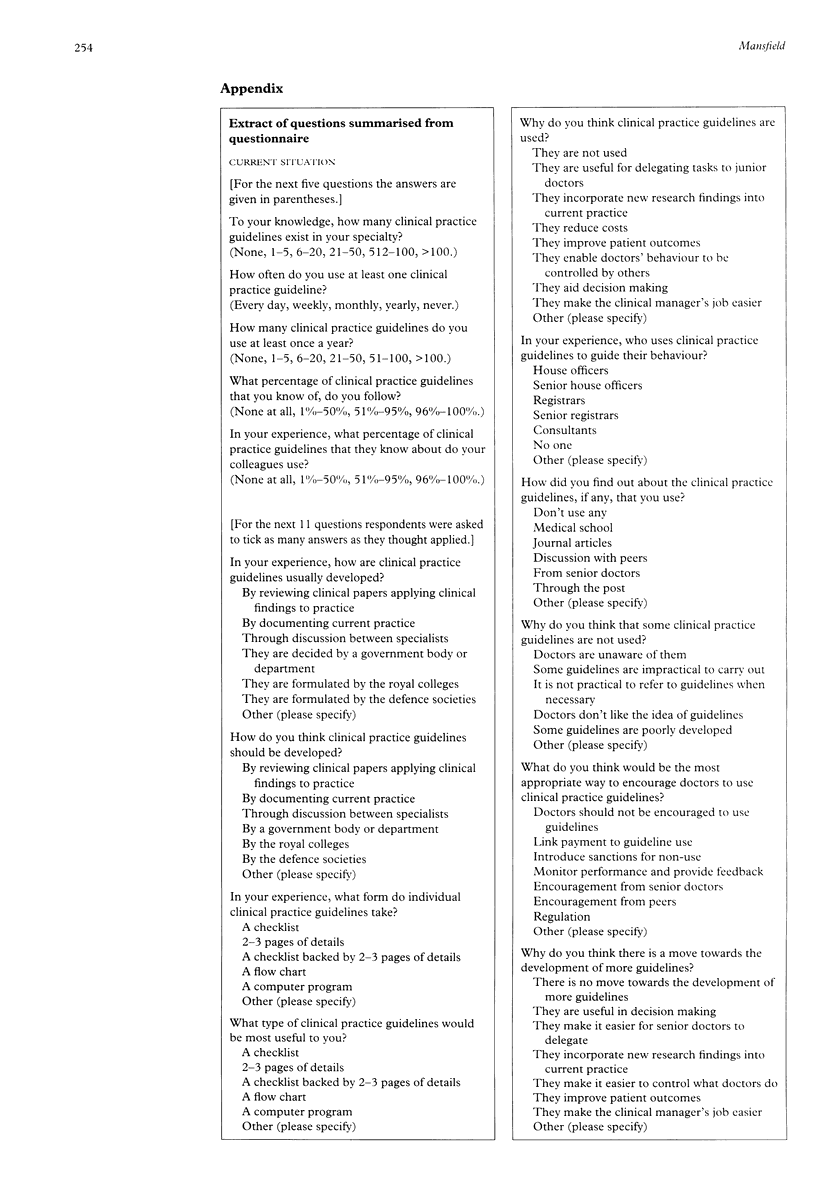

Objectives--To find out what attitudes hospital doctors have towards the culture of clinical guidelines; to ascertain perceived knowledge and use of clinical guidelines; and to investigate why hospital doctors think that clinical guidelines may not be used and how they think that the use of guidelines can be encouraged. Design--Postal questionnaire survey be tween October 1993 and January 1994. Setting--Hospitals within Oxford region. Subjects--409 doctors of all grades working in one of six specialties (anaesthetics, paediatrics, general surgery, general medicine, obstetrics and gynaecology and accident and emergency medicine). 47 were randomly picked as part of the pilot study, 362 were extracted from hospital staffing lists. Results--268 clinicians (66%) responded to the questionnaire. Most respondents (77%, 208) expressed welcoming attitudes towards guidelines but 51%(136) perceived the attitudes of their colleagues as being less favourable. Over three quarters of respondents claimed to use guidelines at least once a month. Most respondents learnt about guidelines from discussions with their peers (50%, 134 respondents) or senior doctors 37%, 99) or from journals (39%, 105). Reasons why guidelines may not be used included being unaware of particular guidelines (80%, 213 respondents) and the fact that guidelines had been poorly developed (64%, 171) or were impractical (49%, 132). The best ways to encourage the use of guidelines were thought to be encouragement from senior doctors (72%, 193 respondents) and peers (59%, 157) and by monitoring behaviour and providing feedback (68%, 181). Conclusion--The decision to use a guide line was based on the perceived value of each guideline and was influenced by other clinicians' behaviour. The results provide an insight into aspects of dissemination and implementation which are perceived as influential by the recipients of guidelines.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Burns L. R., Denton M., Goldfein S., Warrick L., Morenz B., Sales B. The use of continuous quality improvement methods in the development and dissemination of medical practice guidelines. QRB Qual Rev Bull. 1992 Dec;18(12):434–439. doi: 10.1016/s0097-5990(16)30569-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delamothe T. Wanted: guidelines that doctors will follow. BMJ. 1993 Jul 24;307(6898):218–218. doi: 10.1136/bmj.307.6898.218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg J. M., Williams S. V. Cost containment and changing physicians' practice behavior. Can the fox learn to guard the chicken coop? JAMA. 1981 Nov 13;246(19):2195–2201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilmore A. Clinical practice guidelines: weapons for patients, or shields for MDs? CMAJ. 1993 Feb 1;148(3):429–431. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grol R. Implementing guidelines in general practice care. Qual Health Care. 1992 Sep;1(3):184–191. doi: 10.1136/qshc.1.3.184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grol R. National standard setting for quality of care in general practice: attitudes of general practitioners and response to a set of standards. Br J Gen Pract. 1990 Sep;40(338):361–364. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haines A., Feder G. Guidance on guidelines. BMJ. 1992 Oct 3;305(6857):785–786. doi: 10.1136/bmj.305.6857.785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayward R. S., Laupacis A. Initiating, conducting and maintaining guidelines development programs. CMAJ. 1993 Feb 15;148(4):507–512. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lomas J., Anderson G. M., Domnick-Pierre K., Vayda E., Enkin M. W., Hannah W. J. Do practice guidelines guide practice? The effect of a consensus statement on the practice of physicians. N Engl J Med. 1989 Nov 9;321(19):1306–1311. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198911093211906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McColl A. Implementing clinical guidelines. Guidelines may not be cost effective. BMJ. 1993 Sep 11;307(6905):678–679. doi: 10.1136/bmj.307.6905.678-b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittman B. S., Tonesk X., Jacobson P. D. Implementing clinical practice guidelines: social influence strategies and practitioner behavior change. QRB Qual Rev Bull. 1992 Dec;18(12):413–422. doi: 10.1016/s0097-5990(16)30567-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prentice D. A., Miller D. T. Pluralistic ignorance and alcohol use on campus: some consequences of misperceiving the social norm. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1993 Feb;64(2):243–256. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.64.2.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]