Abstract

Background:

Rates of burnout among physicians have been high in recent years. The Electronic Health Record (EHR) is implicated as a major cause of burnout.

Objective:

To determine the association between physician burnout and timing of EHR use in an academic internal medicine primary care practice.

Methods:

We conducted an observational cohort study using cross-sectional and retrospective data. Participants included primary care physicians in an academic outpatient general internal medicine practice. Burnout was measured with a single-item question via self-reported survey. EHR time was measured using retrospective automated data routinely captured within the institution’s EHR. EHR time was separated into four categories: weekday workhours in-clinic time, weekday workhours out-of-clinic time, weekday afterhours time, and weekend/holiday afterhours time. Ordinal regression was used to determine the relationship between burnout and EHR time categories.

Results:

EHR use during in-clinic sessions was related to burnout in both bivariate (OR=1.04, 95% CI 1.01, 1.06; p=0.007) and adjusted (OR=1.07, 95% CI 1.03, 1.1; p=0.001) analyses. No significant relationships were found between burnout and afterhours EHR use.

Conclusions:

In this small single-institution study, physician burnout was associated with higher levels of in-clinic EHR use but not afterhours EHR use. Improved understanding of the variability of in-clinic EHR use, and the EHR tasks that are particularly burdensome to physicians, could help lead to interventions that better integrate EHR demands with clinical care and potentially reduce burnout. Further studies including more participants from diverse clinical settings are needed to further understand the relationship between burnout and afterhours EHR use.

Keywords: physician burnout, physician wellness, electronic health records, health information technology

1. BACKGROUND AND SIGNIFICANCE

Burnout among primary care physicians is a major problem in the US. Forty-eight percent of Internal Medicine physicians reported at least one symptom of burnout in 2017, compared to 43.9% physicians overall.1 In addition to negatively impacting physician health, burnout is also associated with reduced quality of patient care and increased physician turnover, further contributing to healthcare costs and the shortage of physicians.2–6

While many issues can contribute to physician dissatisfaction and burnout, the Electronic Health Record (EHR) increasingly is implicated as a major source of dissatisfaction.7–10 Although the EHR offers some benefits to practice, it also pulls physicians’ time away from meaningful face-to-face patient interactions towards data-entry and asynchronous tasks, such as telephone/patient-portal care.7 Recent studies confirm that the EHR occupies a large portion of physicians’ lives, both during and after traditional workhours. One study found that physicians spent almost half of their workhours engaged with the EHR.11 Another study found that primary care physicians spent almost 6 hours in the EHR per day, including 4.5 hours during, and 1.4 hours outside of, normal clinic hours.12

While prior research has identified the link between perceived EHR workload and burnout, it is not clear whether actual patterns of physicians’ EHR use are associated with burnout. If such a relationship exists, it would help clarify the role that changing EHR use could have on reducing burnout and perhaps illuminate specific patterns that are particularly related to physician stress.

2. OBJECTIVES

We conducted a study to determine the association between physician burnout and timing of EHR use in an academic internal medicine primary care practice. We hypothesized that increased time spent in the EHR, particularly outside of normal workhours, would be associated with higher levels of burnout.

3. METHODS

Study population

Eligible participants included all 58 primary care internal medicine physicians who practiced and managed a primary care clinic panel at 9 of the 10 University of Wisconsin (UW) Health General Internal Medicine (GIM) clinics in the Madison, Wisconsin area. One rural clinic was excluded from this study due to its distinctly different practice environment and workflows. All physicians at these clinics have academic positions at UW-Madison, with practices ranging from full-time clinical work to hybrid practices with variable amounts of teaching, research, and administrative responsibilities. Physicians’ clinical work is structured within half-day sessions. At the time of this study, full-time clinicians (1.0 full-time equivalents, or FTE) were expected to see patients for 27 hours per week in 9 half-day sessions averaging 2.0 patients per hour, with one half-day administrative time per week; providers working clinically less than full-time have reductions in increments of half-day sessions. Full-time physicians are expected to care for a weighted panel13 of 1,800 patients, which is adjusted downward proportional to their in-clinic time. Panel is defined as the group of patients assigned to a specific physician as their primary care provider, and for whom that physician team is expected to provide appropriate primary care, including office visits and non-face-to-face care (i.e. responding to telephone and patient-portal messages). Patients are included on a physician’s panel as long as they have at least one clinical encounter within the organization in the prior 3 years. The study was approved by the UW-Madison Health Sciences Institutional Review Board.

Study measures and data collection

Burnout and sociodemographic data (age, marital status, years since residency, years employed at UW) was collected via an electronic survey sent to all eligible physicians in November 2017. Two reminders were sent approximately 1 and 3 weeks later. Burnout was measured with a single item asking physicians to use their own definition of burnout and rate their feelings on a 5-point scale. Response options included: (1) I enjoy my work. I have no symptoms of burnout; (2) I am under stress, and don’t always have as much energy as I did, but I don’t feel burned out; (3) I am definitely burning out and have one or more symptoms of burnout, e.g., emotional exhaustion; (4) The symptoms of burnout that I am experiencing won’t go away. I think about work frustrations a lot; and (5) I feel completely burned out. I am at the point where I may need to seek help. This single-item measure was chosen for several reasons. First, it is identical to item used to measure burnout in the Physicians Worklife Survey14 as well as the Minimizing Error, Maximizing Outcome (MEMO) study, a multi-site study that showed significant relationships between burnout and lower job satisfaction, greater time pressure, poorer work control, more workplace chaos, lower work-life balance, and greater intent to leave the practice.3,15 This measure of burnout was also found in another study to be associated with physicians leaving their institution in the subsequent two years.6 Secondly, this single-item measure correlates with the emotional exhaustion component of the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI).16–18 While it does not correlate strongly with the other two subscales of the MBI (depersonalization and personal accomplishment),16 prior studies found that the emotional exhaustion subscale, and not the depersonalization subscale, was associated with physicians reducing their work effort4 and leaving practices.19 Lastly, this single-item measure has been promoted by the American Medical Association as part of their STEPS Forward™ program as a method for organizations to measure burnout.20

EHR time and visit volumes were determined for all eligible physicians using retrospective automated data from UW Health’s EHR system (Epic Systems Corporation, Verona WI). One EHR database, event logging records, automatically stores information each time a clinician accesses or moves between modules in the EHR, including the time that the specific process occurs. Sequential time stamps can then be used to determine the time providers spend in the EHR. Time for each individual process was truncated at 90 seconds to minimize inclusion of idle time when the EHR was not engaged by the user.12 EHR data was captured for the 12 months prior to the burnout survey administration. Since we were interested in the work done by primary care outpatient physicians, we only included EHR data when physicians were logged into their outpatient clinic environment, and excluded data directly related to inpatient practice.

EHR time was categorized as occurring either during the workdays, afterhours-weekdays, or weekends/holidays. The workday was defined as 7:30am to 5:29pm, to capture variation in clinic start times (ranging from 7:50am to 8:00am) and end times (no patients are scheduled after 5pm), and included some time before/after clinic to review and finish charting. Workdays were further subdivided into morning (7:30am to 12:29pm) and afternoon (12:30pm to 5:29pm) half-day sessions. Billing data was used to categorize the time for each half-day session as occurring in-clinic (≥ 1 billed office visit during the half-day period) or out-of-clinic (no office visit billed during that half-day period). Visits done by residents were assigned to the supervising (billing) attending. The average EHR time per in-clinic and out-of-clinic session was then calculated by dividing in-clinic and out-of-clinic EHR times by the number of in-clinic and out-of-clinic sessions respectively. Similarly, the average EHR time for afterhours-weekdays and weekend/holidays was divided by the number of weekday and weekend/holiday days respectively. The number of days was further adjusted for physicians who started working at UW Health, or took a leave-of-absence, within the EHR time-period of interest.

Administrative records were used to collect physicians’ sex and clinical FTE (cFTE). For simplicity, cFTE was defined as the proportion of 10 half-day sessions a provider was expected to be in clinic seeing patients per week.

Analyses

Descriptive statistics were used to describe participants’ demographic and practice characteristics, degree of burnout, and timing of EHR use. Burnout was treated as an ordinal (ordered) variable. While most previous studies used burnout as a dichotomous variable, we chose to use it as an ordinal variable to retain potentially important differences between providers with varying levels of responses, and to maintain power in our analysis.21 Bivariate analyses using nonparametric testing (Spearman’s rho for two continuous variables, Mann-Whitney U for continuous-dichotomous variables) examined the unadjusted relationship between burnout/EHR use and demographic and practice characteristics. Ordinal regression was then used to determine the bivariate and adjusted relationships between burnout (dependent variable) and EHR times. The adjusted model included all EHR time categories (excluding total EHR time) as independent variables, as well as potential confounders. Age and sex were automatically included as potential confounders since they were frequently associated with burnout in prior studies.2 Visit volume, defined as the total number of visits, was included to adjust for workload; visit volume was felt to adjust for workload better than cFTE, since it changes based on time away from clinic (i.e., due to vacations or conferences) whereas cFTE does not. We included additional demographic/practice characteristics as covariates only if they were significantly related to EHR use or burnout in bivariate analyses (p<0.05). The analyses used EHR data in the 3 months prior to the survey, since this time period was expected to be more relevant to our one-time measurement of burnout, and long enough to reduce susceptibility to month-to-month schedule variations. In addition, sensitivity analyses using different EHR time periods (1, 6, and 12 months prior to the survey) showed similar results. Analyses were conducted using SPSS v.25 (2017, IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY) and Stata/SE v.15.1 (2019, StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX).

4. RESULTS

Characterization of EHR use

Of the 58 eligible physicians for this study, most were female (62%) with cFTEs ranging from 0.6–0.8. EHR data was available for all 58 physicians, while only 34 (59%) completed the survey. There were no significant differences in sex, cFTE, number of clinic visits, and EHR use between those that did and did not complete the survey (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of participants in the study

| Characteristic | All participants (n=58) |

Completed survey (n=34; 59%) |

Did not complete Survey (n=24; 41%) |

p-value‡ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female (%) | 36 (62%) | 22 (65%) | 12 (50%) | 0.62§ |

| Clinical FTE (%)* | ||||

| 0 – 0.5 | 15 (26%) | 9 (26%) | 6 (25%) | 0.60‖ |

| 0.6 – 0.8 | 29 (50%) | 18 (53%) | 11 (46%) | |

| 0.9 | 14 (24%) | 7 (21%) | 7 (29%) | |

| Mean number of visits performed in 3 months prior to survey (SD) | 387.9 (146.2) | 391.1 (154.2) | 384.5 (139.0) | 0.88¶ |

| Total time on EHR in 3 months prior to survey: mean hours (SD) | 238.7 (103.6) | 248.2 (109.5) | 225.2 (95.4) | 0.52¶ |

| Mean EHR time per half-day in-clinic weekday session: minutes (SD) | 141 (25) | 145 (27) | 135 (20) | 0.10¶ |

| Median† EHR time per half-day out-of-clinic weekday session: minutes (range) | 27 (1, 129) | 27 (2, 106) | 27 (1, 129) | 0.30¶ |

| Median† EHR time per afterhours weekday: minutes (range) | 17 (0, 109) | 18 (0, 104) | 14 (2, 109) | 0.67¶ |

| Median† EHR time per afterhours weekend/holiday day: minutes (range) | 16 (0, 186) | 16 (0, 163) | 14 (0, 186) | 0.63¶ |

| Mean age in years (SD) | NA# | 48 (10.0) | NA# | |

| Mean years since residency (SD) | NA# | 16.5 (9.9) | NA# | |

| Mean years at UW (SD) | NA# | 11.7 (8.3) | NA# | |

| Marital Status | NA# | |||

| Married/Partner | NA# | 32 (94%) | NA# | |

| Never married | NA# | 2 (6%) | NA# |

Clinical FTE is the proportion of half-day sessions a provider was expected to be in-clinic per week.

Median reported, due to positively skewed distribution of data

p-value compares those that did vs. did not complete the survey

Pearson Chi-Squared

Linear trend

Mann-Whitney U

NA = Not applicable, as information was only obtained via survey

The majority of EHR time occurred when physicians were in-clinic, where they used the EHR for an average of 141 minutes (2.4 hours) per each half-day session (Table 1). Physicians saw an average of 5.6 (SD 0.8) patients per session. EHR usage for other time categories was positively skewed, and was relatively low during weekdays when physicians were not in clinic (median 27 minutes per half-day session, range 1–129), afterhours during the week (median 17 minutes per weekday, range 0–109), and afterhours on weekends/holidays (median 16 minutes per weekend/holiday day, range 0–186). While it is difficult to determine the time spent in EHR on a typical weekday because of the variability in physicians’ schedules, we estimate that physicians spent approximately 299 minutes (5 hours) on the EHR during a day when they were in-clinic for both morning and afternoon sessions (average 141 minutes for each half-day session, plus a median 17 minutes per weekday afterhours).

EHR use varied according to physicians’ volume in practice, with higher cFTEs and higher visit volumes associated with more total EHR time, half-day in-clinic session EHR time, and weekend/holiday EHR time (Table 2). Out-of-clinic session EHR time was significantly associated with a higher number of visits, but not with cFTE. No significant relationships were seen between EHR time categories and physicians’ age, sex, marital status, or years in practice.

Table 2.

Bivariate relationship between EHR time and Clinical FTE/Number of Visits (n=34)

| Characteristic | EHR Time Category | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total hours of EHR time ρ p-value |

Minutes per half-day in-clinic session ρ p-value |

Minutes per half-day out-of-clinic session ρ p-value |

Minutes per afterhours weekday ρ p-value |

Minutes per weekend/ holiday day ρ p-value |

|

| Clinical FTE | 0.78 p<0.001 |

0.51 p=0.002 |

0.31 p=0.08 |

0.19 p=0.27 |

0.37 p=0.03 |

| Number of Visits | 0.81 p<0.001 |

0.46 p=0.006 |

0.35 p=0.04 |

0.24 p=0.18 |

0.36 p=0.04 |

ρ = Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient

Burnout and EHR use

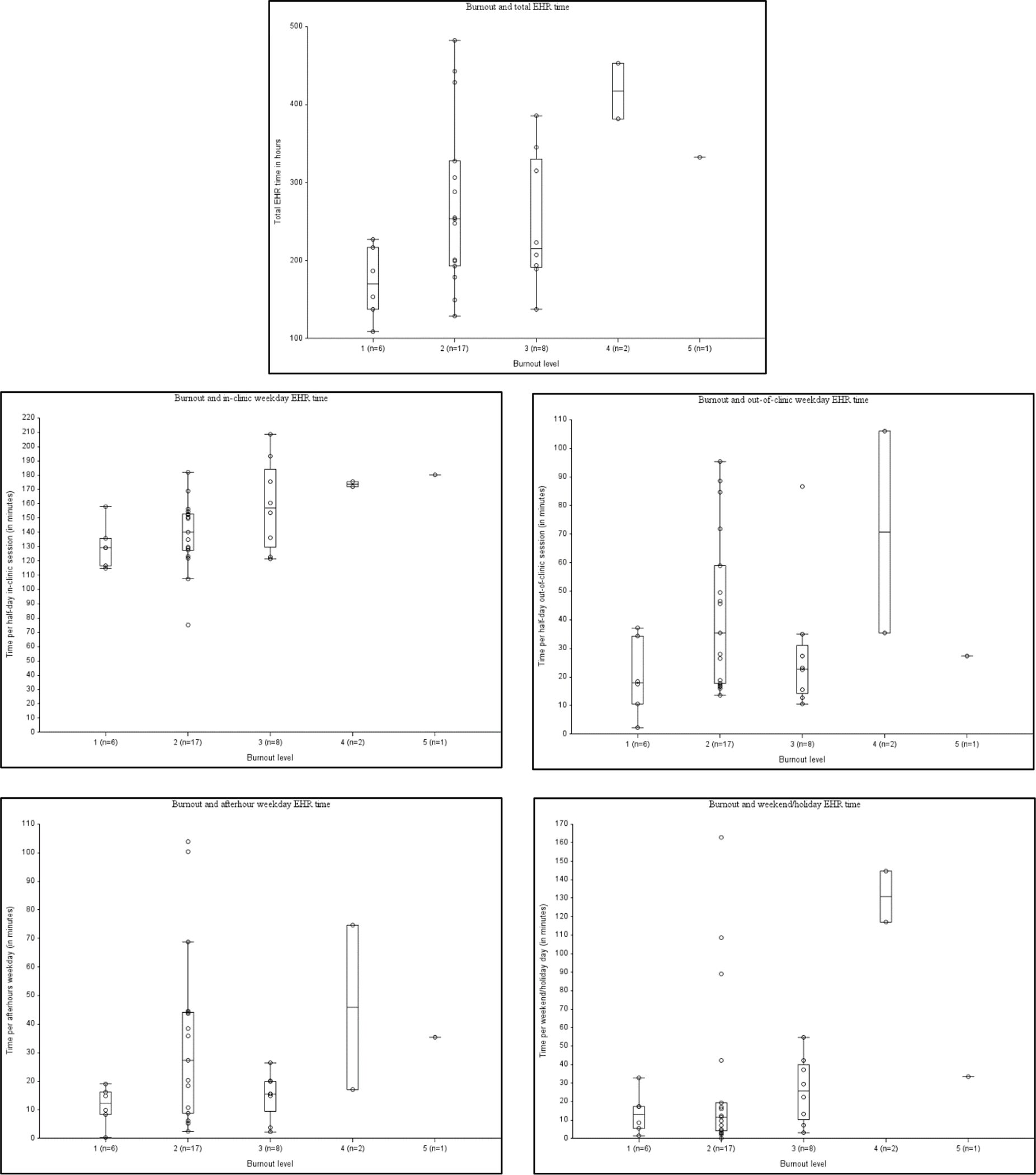

Among the 34 survey respondents, the average burnout rating was 2.3 (SD 0.9) on the 1–5 scale where higher ratings indicate more burnout. Most respondents scored a 2 (n=17, 50%) on the scale, while only one physician endorsed a 5 (the highest level of burnout). In bivariate analyses, there were no significant relationships (p<0.05) between burnout and sex, age, marital status, years since clinical training, years at UW Health, cFTE, and visit volume. In unadjusted analyses, higher levels of burnout were associated with more total and in-clinic EHR time (Table 3 and Figure). In models adjusting for age, sex, cFTE, visit volume, and other categories of EHR time, burnout was only significantly associated with in-clinic EHR time and not with out-of-clinic or afterhours EHR time (Table 3).

Table 3.

Relationship between burnout and EHR time (n=34)

| EHR time category | OR | |

|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted* OR (95% CI) p-value |

Adjusted† OR (95% CI) p-value |

|

| Total hours of EHR time | 1.007 (1.001, 1.01) p=0.03 |

NA |

| Minutes per half-day in-clinic session | 1.04 (1.01, 1.06) p=0.007 |

1.07 (1.03, 1.1) p=0.001 |

| Minutes per half-day out-of-clinic session | 1.01 (0.99, 1.04) p=0.33 |

0.99 (0.96, 1.02) p=0.40 |

| Minutes per afterhours weekday | 1.01 (0.98, 1.03) p=0.61 |

0.99 (0.95, 1.02) p=0.45 |

| Minutes per weekend/holiday day | 1.02 (0.999,1.03) p=0.06 |

1.01 (0.99, 1.04) p=0.27 |

OR = Odds Ratios, determined using ordinal regression with burnout as the dependent variable and EHR time categories as the primary independent variable

Unadjusted analysis represents a separate model for each time category

Adjusted for sex, age, clinical FTE, number of visits, and other time categories (total EHR time excluded); NA = Not Applicable

5. DISCUSSION

In this small study of physicians in an academic primary care internal medicine practice, we found that burnout was associated with the amount of EHR use that occurred during clinic sessions. This finding may indicate that physicians with more in-clinic EHR use feel a greater intrusion of the EHR pulling them away from meaningful face-to-face interactions towards computer-time and data-entry tasks.7 Our result is consistent with prior research reporting that increased clerical burden is associated with burnout and lower job satisfaction.22 Certainly, some of the variability in physicians’ in-clinic EHR use may be related to different workloads in face-to-face and asynchronous care, which is reflected in our finding that a higher visit volume was associated with more EHR time in all categories. Efforts to understand the amount of EHR time required to care for specific panels of patients may help normalize productivity expectations, and could prevent overly burdensome workloads. However, variability in EHR use may also be related to inefficiencies in EHR-related proficiency and workflows, even among physicians in the same practice setting. Further research could help determine best-practices associated with EHR efficiency, as well as identify specific EHR tasks that particularly increase in-clinic EHR time and burnout. This could lead to targeted physician- and organization-level interventions focused on improving EHR efficiency, offloading work from physicians, and better integrating computer-oriented tasks during face-to-face encounters. Indeed, physician satisfaction has been shown to improve with interventions that distribute EHR tasks to other members of the healthcare team,23,24 enhance physicians’ EHR efficiency through proficiency training,25,26 and improve note documentation.27

Our results did not show a consistently significant relationship between afterhours EHR work (often referred to as “pajama time”) and burnout. These results are not consistent with prior findings that self-reported time spent at home on work-related tasks negatively impacts physician satisfaction and burnout.2,28 Possible reasons for not finding a significant relationship include our low statistical power due to the low number of participants, and our lack of inclusion of personal information—such as the presence of work-home conflicts—that may impact the consequence of afterhours work in individual physicians.2,29 It may also be related to the relatively low amount of EHR time we observed in the afterhours periods compared with prior studies.11,12 Some of this difference may be attributed to differences in methodologies, as one study used self-report to determine afterhours work,11 which might be an inaccurate estimate of objectively-measured EHR time outside of clinic.30 Another study normalized EHR time to a full-time physician and included weekday and weekend use in afterhours totals.12 Nonetheless, physicians in this study had relatively low face-to-face time and patients-per-hour requirements compared with other organizations, which may have resulted in lower afterhours EHR use and limit the generalizability of our findings to settings with higher productivity requirements. Further studies including a larger number of participants from diverse clinical settings, and perhaps examining for threshold effects or looking at maximum (rather than average) afterhours EHR times, are needed to further define the relationship between afterhours EHR work and burnout.

There are several limitations to our study. First, while the response rate to our survey was adequate (59%), our sample size was low and might have limited our power to detect meaningful relationships. While the demographic characteristics and EHR use of survey responders and non-responders were not significantly different, the possibility that responders were less—or more—burned out than respondents could affect our results and generalizability. Secondly, we measured burnout with a single-item question, which may have less validity and discriminatory ability compared with the complete 22-item Maslach Burnout Inventory. We chose a single validated measure to encourage a higher response rate among our small group of physicians. Third, our measure of EHR use was not an exact measure of physician’s active engagement with EHR, but rather based on User Access Logs which cannot discriminate between active or idle time. Fourth, EHR measurements intentionally only included time spent when physicians were logged in to their outpatient environment. Our EHR metric was therefore not a reflection of total EHR work, and some EHR work may have been misclassified if physicians performed inpatient work while logged into their outpatient environment, or vice versa. Nonetheless, we believe this effect would have minimal impact on our results, since only 8 respondents (24%) did inpatient work. Fifth, our EHR metric did not subdivide the type of EHR work performed, such as work for office visit documentation, order entry, billing, telephone calls, or patient-portal messages. Future studies including EHR task categorizations could help identify which EHR tasks may particularly contribute to burnout. Lastly, our sample was restricted to academic internal medicine physicians in one university-based practice setting, so may not be applicable to other academic or non-academic practices. Observed patterns of EHR use are likely dependent on multiple site-specific characteristics, such as defined workhours, patients-per-hour requirements, and amount of EHR training and optimization support—which could change over time within organizations. Additional studies including multiple practice sites and larger sample sizes would be needed to help confirm our findings and discern if variation exists between burnout and EHR use in other populations.

6. CONCLUSIONS

In summary, our results show that burnout among physicians is associated with higher levels of in-clinic EHR use, but not with afterhours EHR use. It is important for future studies to further clarify the relationship between burnout and afterhours EHR use in larger populations and other settings. It is also imperative to better understand the factors involved with high-intensity and intrusive EHR use, particularly during clinic sessions when physicians are required to do multiple computer-related tasks while seeing patients. Improved understanding of the dynamics of in-clinic EHR use, including which specific EHR tasks are particularly related to burnout, may lead to focused interventions at the organizational and individual level, such as improved EHR training,25,26 the adoption of scribes,23,24 or the reduction of waste in data-entry and documentation processes.31–33 These strategies may ultimately help promote better quality of care and a happier and more stable physician workforce.

Figure 1: Bivariate relationship between burnout and EHR time, by EHR time category (n=34).

Each graph represents a scatterplot of burnout (X-axis) and EHR time (Y-axis), with a separate graph for each EHR time category. Overlying the scatterplots are boxplots, with bands representing the median, and the top and bottom of the box plot representing the first and third quartiles (respectively).

Clinical Relevance Statement

This manuscript presents our findings of an observational cohort study using novel ways to objectively characterize primary care physicians’ EHR use, to determine the relationship between burnout and their use of the EHR. We found that burnout is primarily related to EHR use during clinic sessions, and not related to afterhours EHR use. We believe our results may help refine efforts to improve physician burnout, by focusing attention on strategies that specifically help integrate EHR demands with in-clinic care.

Multiple Choice Questions

-

1In which of the following time periods do physicians spend the most time in the EHR?

- Afterhours during the week.

- Afterhours on weekends and holidays.

- During a clinic session, when seeing patients.

- During the weekdays, when not seeing patients.

Correct answer: The correct answer is option c. In this study, the highest amount of EHR time was seen during periods of time when physicians were in clinic seeing patients. During a 5 hour half-day period when physicians were seeing patients, they spent an average of 2.4 hours on the EHR. This contrasts with lower amounts of time spent in other time periods. For example, physicians in this study only used the EHR for a median of 27 minutes during half-day periods on the weekdays when not in clinic (ie during administrative time, or time off), 17 minutes per afterhours weekday, and 16 minutes per afterhours weekend/holiday day.

-

2Among physicians in this study, higher levels of burnout were associated with higher amounts of EHR time during which of the following periods?

- Afterhours during the week.

- Afterhours on weekends and holidays.

- During a clinic session, when seeing patients.

- All of the above time periods.

Correct answer: The correct answer is option c. In this study, physician burnout was statistically associated with in-clinic EHR time, when physicians were seeing patients. This relationship persisted in both bivariate and multivariate analyses, when adjusting for demographic and practice characteristics, and other EHR time periods. A consistent relationship between burnout and EHR time was not seen with any of the other EHR time periods.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by Pilot Project funding from the Division of General Internal Medicine at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Additional support was received from the Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSA) program, previously through the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR) grant 1UL1RR025011, and now by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), grant 9U54TR000021. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health, the Department of Veterans Affairs, or the United States government. This project was also supported by the University of Wisconsin Carbone Cancer Center (UWCCC) Support Grant from the National Cancer Institute, grant number P30 CA014520. Additional support was provided by the UW School of Medicine and Public Health from the Wisconsin Partnership Program. We would also like to thank Linda Baier Manwell, MS, for her insightful advice and logistical support throughout this study.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have any conflicts of interest.

Protection of Human and Animal Subjects

This study was performed in compliance with the Belmont Report and the Common Rule (45 CFR 46), and was approved by the UW-Madison Health Sciences Institutional Review Board.

REFERENCES

- 1.Shanafelt TD, West CP, Sinsky C, et al. Changes in Burnout and Satisfaction With Work-Life Integration in Physicians and the General US Working Population Between 2011 and 2017. Mayo Clin Proc. 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.West CP, Dyrbye LN, Shanafelt TD. Physician burnout: contributors, consequences and solutions. J Intern Med. 2018;283(6):516–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rabatin J, Williams E, Baier Manwell L, Schwartz MD, Brown RL, Linzer M. Predictors and Outcomes of Burnout in Primary Care Physicians. J Prim Care Community Health. 2016;7(1):41–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shanafelt TD, Mungo M, Schmitgen J, et al. Longitudinal Study Evaluating the Association Between Physician Burnout and Changes in Professional Work Effort. Mayo Clin Proc. 2016;91(4):422–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Panagioti M, Geraghty K, Johnson J, et al. Association Between Physician Burnout and Patient Safety, Professionalism, and Patient Satisfaction: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(10):1317–1330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 6.Hamidi MS, Bohman B, Sandborg C, et al. Estimating institutional physician turnover attributable to self-reported burnout and associated financial burden: a case study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Friedberg MW, Chen PG, Van Busum KR, et al. Factors Affecting Physician Professional Satisfaction and Their Implications for Patient Care, Health Systems, and Health Policy. Rand Health Q. 2014;3(4):1. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Babbott S, Manwell LB, Brown R, et al. Electronic medical records and physician stress in primary care: results from the MEMO Study. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2014;21(e1):e100–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coleman M, Dexter D, Nankivil N. Factors Affecting Physician Satisfaction and Wisconsin Medical Society Strategies to Drive Change. WMJ. 2015;114(4):135–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sinsky CA, Dyrbye LN, West CP, Satele D, Tutty M, Shanafelt TD. Professional Satisfaction and the Career Plans of US Physicians. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92(11):1625–1635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sinsky C, Colligan L, Li L, et al. Allocation of Physician Time in Ambulatory Practice: A Time and Motion Study in 4 Specialties. Ann Intern Med. 2016;165(11):753–760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arndt BG, Beasley JW, Watkinson MD, et al. Tethered to the EHR: Primary Care Physician Workload Assessment Using EHR Event Log Data and Time-Motion Observations. Ann Fam Med. 2017;15(5):419–426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kamnetz S, Trowbridge E, Lochner J, Koslov S, Pandhi N. A Simple Framework for Weighting Panels Across Primary Care Disciplines: Findings From a Large US Multidisciplinary Group Practice. Qual Manag Health Care. 2018;27(4):185–190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Williams ES, Konrad TR, Linzer M, et al. Refining the measurement of physician job satisfaction: results from the Physician Worklife Survey. SGIM Career Satisfaction Study Group. Society of General Internal Medicine. Med Care. 1999;37(11):1140–1154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Linzer M, Manwell LB, Williams ES, et al. Working conditions in primary care: physician reactions and care quality. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(1):28–36, W26–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rohland BM, Kruse GR, Rohrer JE. Validation of a single-item measure of burnout against the Maslach Burnout Inventory among physicians. Stress Health. 2004;20(2):75–79. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hansen V, Girgis A. Can a single question effectively screen for burnout in Australian cancer care workers? BMC Health Serv Res. 2010;10:341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dolan ED, Mohr D, Lempa M, et al. Using a single item to measure burnout in primary care staff: a psychometric evaluation. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(5):582–587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Windover AK, Martinez K, Mercer MB, Neuendorf K, Boissy A, Rothberg MB. Correlates and Outcomes of Physician Burnout Within a Large Academic Medical Center. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(6):856–858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mini Z burnout survey. American Medical Association. https://www.stepsforward.org/modules/physician-burnout-survey. Accessed 7/26/2018. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Altman DG, Royston P. The cost of dichotomising continuous variables. BMJ. 2006;332(7549):1080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shanafelt TD, Dyrbye LN, Sinsky C, et al. Relationship Between Clerical Burden and Characteristics of the Electronic Environment With Physician Burnout and Professional Satisfaction. Mayo Clin Proc. 2016;91(7):836–848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gidwani R, Nguyen C, Kofoed A, et al. Impact of Scribes on Physician Satisfaction, Patient Satisfaction, and Charting Efficiency: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Ann Fam Med. 2017;15(5):427–433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shultz CG, Holmstrom HL. The use of medical scribes in health care settings: a systematic review and future directions. J Am Board Fam Med. 2015;28(3):371–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dastagir MT, Chin HL, McNamara M, Poteraj K, Battaglini S, Alstot L. Advanced proficiency EHR training: effect on physicians’ EHR efficiency, EHR satisfaction and job satisfaction. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2012;2012:136–143. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Longhurst CA, Davis T, Maneker A, et al. Local Investment in Training Drives Electronic Health Record User Satisfaction. Appl Clin Inform. 2019;10(2):331–335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Belden JL, Koopman RJ, Patil SJ, Lowrance NJ, Petroski GF, Smith JB. Dynamic Electronic Health Record Note Prototype: Seeing More by Showing Less. J Am Board Fam Med. 2017;30(6):691–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Robertson SL, Robinson MD, Reid A. Electronic Health Record Effects on Work-Life Balance and Burnout Within the I(3) Population Collaborative. J Grad Med Educ. 2017;9(4):479–484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dyrbye LN, West CP, Satele D, Sloan JA, Shanafelt TD. Work/Home conflict and burnout among academic internal medicine physicians. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(13):1207–1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.DiAngi YT, Stevens LA, Halpern-Felsher B, Pageler NM, Lee TC. Electronic health record (EHR) training program identifies a new tool to quantify the EHR time burden and improves providers’ perceived control over their workload in the EHR. JAMIA Open. 2019;2(2):222–230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bain PA. How Physicians Can Save 56 Hours Per Year. WMJ. 2017;116(2):52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ashton M. Getting Rid of Stupid Stuff. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(19):1789–1791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Guo U, Chen L, Mehta PH. Electronic health record innovations: Helping physicians - One less click at a time. Health Inf Manag. 2017;46(3):140–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]