Abstract

Introduction

Professional societies state that Transgender and gender expansive (TGE) adolescents and their families should be counseled about future family building options prior to initiating gender affirming therapy. While emerging data show that TGE adolescents have diverse desires regarding future family building, little is known regarding how these preferences are developed in a larger ecological context.

Aim

The current study used Ecological Systems Theory as a framework to describe the family building attitudes of TGE adolescents, their caregivers, and their siblings.

Methods

Participants were recruited from community-based venues in the New England region of the U.S. to participate in the TTFN Project, a longitudinal community-based mixed methods study. The sample for the current study included 84 family members from 30 families (30 TGE adolescents, 11 siblings, 44 caregivers). All participants completed a semi-structured qualitative interview about family building attitudes and desires for TGE and cisgender adolescents at two waves across 6-8 months. Interview transcripts were analyzed using a combination of immersion/crystallization, thematic analysis, and template organizing style approaches. The Transgender Youth Fertility Attitudes Questionnaire (TYFAQ) was employed to quantitatively describe the family building attitudes of TGE adolescents and their families.

Results

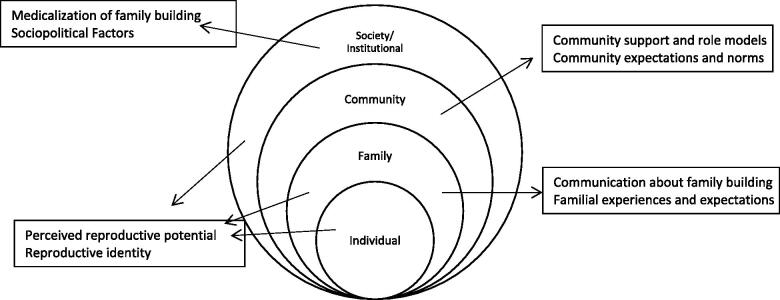

Eight themes corresponding to the levels of the ecological systems model – individual-level (perceived reproductive potential, reproductive identity), family-level (communication about family building, familial experiences and expectations), community-level (community support and role models; community expectations and norms), and societal/institutional-level (medicalization of family building, external sociopolitical factors) – were developed from the interviews. Results from the TYFAQ indicated that compared to cisgender adolescents, TGE adolescents were less likely to value having biological children and more likely to consider adoption in comparison to their cisgender siblings.

Discussion

Findings emphasize the importance of using Ecological Systems Theory to understand the family building attitudes and desires of TGE adolescents and their families.

Keywords: Adolescents, ecological systems, longitudinal, family building, fertility, transgender

Introduction

Transgender and gender expansive (TGE) adolescents identify differently from the gender(s) traditionally associated with their assigned sex(es) at birth. TGE adolescents, their families, and their medical providers are often faced with medical decisions that can affect their future fertility and family building options. The World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH) recommends that all TGE patients receive fertility counseling before initiating gender-affirming medical or surgical interventions (Coleman et al., 2012). Despite these recommendations, TGE adolescents are infrequently referred for formal counseling on fertility preservation (Chen et al., 2019; Wakefield et al., 2019). For those who do receive referrals, utilization of fertility preservation services is low (Nahata et al., 2017; Rafferty, 2019). Although previous research has examined the attitudes and desires of TGE adolescents regarding their future fertility desires, most of this research has focused on the isolated perspectives of adolescents themselves at single time points (Chen et al., 2019; Strang et al., 2018). One qualitative study showed that family values and finances were influential when a TGE adolescent was deciding to use fertility preservation services, suggesting that external factors should be considered when examining this population’s family building desires (Chen et al., 2019). The current study aimed to situate the family building attitudes and beliefs of TGE adolescents and their families, including parents and siblings, within the larger communal and societal contexts.

In a recent cross-sectional study of 156 TGE adolescents, 50% of respondents were interested in having children someday, but 83% reported never having conversations with their healthcare providers about hormonal treatments’ effects on their future fertility (Chen et al., 2018). Another cross-sectional study with 150 adult transmasculine participants (i.e., those who were assigned female at birth and identify as a gender other than girl/woman) showed that 20% planned to have biological children (defined as children conceived rather than adopted, therefore carrying genes from the parent(s)) in the future; of these, 9% planned to carry their pregnancies, and 12% planned to employ surrogates (Stark et al., 2019). Little is known about how family members may influence TGE adolescents’ parenthood goals, but emerging research has shown that familial connectedness is essential to many aspects of TGE health and wellbeing. In one study, parental support was associated with higher life satisfaction, lower perceived burden of being TGE, fewer depressive symptoms, and less suicidality among TGE adolescents (Chen et al., 2019). One qualitative study suggested that family values and finances were critical in deciding whether or not TGE adolescents would pursue fertility preservation (Chen et al., 2019). In 2018, Strang et al. developed the Transgender Youth Fertility Attitudes Questionnaire (TYFAQ), a 16-item scale to assess fertility attitudes and knowledge among TGE adolescents and their caregivers. A pilot test of the TYFAQ showed relative concordance in fertility attitudes and knowledge between TGE adolescents and their caregivers (Strang et al., 2018). However, factors affecting how TGE adolescents and their families develop preferences and attitudes toward future fertility and family building options remain unclear. While one Norwegian study suggested that there was significant cross-sibling influence when deciding whether to initiate biological parentage (Lyngstad & Prskawetz, 2010), no previous research on parenthood goals among families with TGE adolescents has incorporated the perspective of cisgender siblings.

The aim of the current study was to describe how TGE adolescents develop future family building preferences using quantitative survey data in conjunction with qualitative interviews of participants in the Trans Teen and Family Narratives (TTFN) Project, a longitudinal community-based mixed methods study designed to examine how family, community, and societal environments affect the health and well-being of TGE adolescents (Katz-Wise et al., 2018, 2019, 2020).

Methods

Participants

Participants were part of the TTFN Project, which included 96 family members from 33 families, including 33 TGE adolescents, 15 siblings, and 48 caregivers. Families were recruited from community-based venues in the New England region of the U.S. participate in the TTFN Project (Katz-Wise et al., 2018, 2019, 2020). Community-based venues included: support organizations; lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ+) organizations; LGBTQ + adolescent drop-in centers; homeless shelters; medical and mental health providers; and gender clinics. TGE adolescents between ages 13-17 years who lived in New England and identified as different gender(s) from their sex assigned at birth were eligible to participate. Caregivers and siblings (age 13+ years) of eligible TGE adolescents were also invited to participate in the study.

All participants originally enrolled in the TTFN Project who participated in Waves 4 and 5 were included in the current analysis. This subsample included 84 family members from 30 families, including 29 TGE adolescents, 11 siblings, and 44 caregivers. Among TGE adolescents, 10 were transgender girls, 12 were transgender boys, and 7 were non-binary (6 of whom were assigned female at birth, and 1 of whom was assigned male at birth). Among siblings, 6 were cisgender girls/women and 5 were cisgender boys/men. Among caregivers, 24 were cisgender women and 20 were cisgender men. Sociodemographic characteristics for the sample are displayed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sample demographic characteristics by family member for families with transgender and gender expansive (TGE) adolescents (N = 84 family members).

| Demographic Characteristic |

TGE Adolescents

(n = 29) |

Caregivers

(n = 44) |

Cisgender Adolescents

(n = 11) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years, M (SD) | 17.3 (3.5) | 52.3 (8.2) | 19.9 (4.1) |

| Gender identity, n (%) | |||

| TGN, assigned female at birth | 18 (62) | 0 | 0 |

| TGN, assigned male at birth | 11 (38) | 0 | 0 |

| Cisgender girl/woman | 0 (0) | 24 (54.5) | 6 (54.5) |

| Cisgender boy/man | 0 (0) | 20 (45.5) | 5 (45.5) |

| Race/Ethnicity, n (%) * | |||

| White | 22 (76.5) | 40 (90.9) | 8 (72.7) |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 1 (3.5) | 2 (4.5) | 1 (9.1) |

| Asian | 2 (7.0) | 0 (0) | 1 (9.1) |

| Black or African American | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (9.1) |

| Hispanic or Latinx | 1 (3.5) | 2 (4.5) | 0 (0) |

| More than one race/ethnicity | 3 (10.5) | 1 (2.3) | 1 (9.1) |

| Current grade, n (%) | |||

| 10th | 1 (3.5) | – | 0 (0) |

| 11th | 4 (13.7) | – | 2 (18.1) |

| 12th | 8 (27.5) | – | 1 (9.1) |

| Completed high school, not in school | 3 (10.5) | – | 1 (9.1) |

| Completed high school, currently in college | 13 (44.8) | – | 5 (45.5) |

| Completed college | 0 (0) | – | 1 (9.1) |

| Graduate school, current | 0 (0) | – | 1 (9.1) |

| Education Level, n (%) | |||

| Did not complete high school | – | 1 (2.3) | – |

| High school diploma | – | 5 (11.4) | – |

| Associate’s degree | – | 7 (15.9) | – |

| Bachelor’s degree | – | 12 (27.3) | – |

| Master’s degree | – | 11 (25) | – |

| Doctoral or professional degree | – | 8 (18.1) | – |

| Sexual Orientation, n (%) | |||

| Lesbian, gay, bisexual, queer | 21 (72.4) | 4 (9.1) | 3 (27.3) |

| Asexual | 0 | 0 (0) | 1 (9.1) |

| Heterosexual | 8 (27.6) | 40(90.9) | 7 (63.6) |

| Adoption Status, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 3 (10.5) | 1 (2.3) | 2 (18.1) |

Total does not add to 100% as participants were able to select multiple races.

Study procedure

The TTFN Project used community-based participatory research (CBPR) principles to involve community members in multiple steps of the research process, including study design, participant recruitment, development of study materials, and interpretation of results (Olden, 1998). The full TTFN Project included five waves of data collection; families participated every 6-8 months across 30 months. Data for the current analysis came from semi-structured interviews and surveys conducted at two waves, Wave 4 (1.5 years post-baseline) and Wave 5 (2 years post-baseline), between 2017 and 2019. Each participant completed a one-time, one-on-one, semi-structured interview and survey at each wave in a private room in the researcher’s office space, at the family’s home, or via teleconference. At the start of each session, participants younger than 18 years provided written informed assent along with caregivers’ written informed consent. Adult participants age 18 and older provided informed consent for themselves. Research team members who were LGBTQ+-identified or allies conducted interviews. Surveys were completed via RedCap either on an electronic tablet (for in-person study sessions) or online with participants’ own devices. At the end of each study session, participants received $25 gift cards in Wave 4 and $35 gift cards in Wave 5. Interviews were audio-recorded and professionally transcribed verbatim. All study procedures were approved by the Boston Children’s Hospital Institutional Review Board. Additional methods details are provided in previous publications from the TTFN Project (Katz-Wise et al., 2018, 2019, 2020).

Measures

Interview protocol

Three individualized interview protocols were developed for three categories of TTFN Project participants: TGE adolescents, siblings, and caregivers. A scientific advisory board, community partners, and stakeholders representing the interests of TGE adolescents and families reviewed the protocols. Full interview protocols addressed family functioning and support needs related to TGE adolescents’ gender identities. Interview questions analyzed for the current analysis addressed four primary domains: 1) current desires for future family building, 2) TGE identity and family building, 3) conversations and communication regarding family building, and 4) resources and support for family building. Example questions can be found in Table 2.

Table 2.

Example interview questions by participant type.

| Transgender and Gender Expansive Adolescents | Cisgender Adolescents | Caregivers |

|---|---|---|

| What do you think about possibly having children in the future? | What do you think about possibly having children in the future? | What do you think about your child(ren) possibly having their own children in the future? |

| When you think about possibly having children in the future, how do you think that might happen? (Specifically probe about method of family building [e.g. adoption, biological children] and timing.) | When you think about possibly having children in the future, how do you think that might happen? (Specifically probe about method of family building [e.g. adoption, biological children] and timing.) | When you think about your child(ren) possibly having their own children in the future, how do you envision that happening? (Specifically probe about method of family building [e.g. adoption, biological children] and timing.) |

| – | What do you think about [TRANS TEEN] possibly having children in the future? | What do you think about your trans teen possibly having their own children in the future? |

| How do you think your experience of being transgender has affected what you think about possibly having children in the future? | – | How do you think your trans teen’s gender identity has impacted your ideas about your child(ren) possibly having their own children in the future? |

Survey

The TYFAQ is a 16-item questionnaire for both TGE adolescents and their caregivers to assess fertility attitudes and knowledge. A modified version of the TYFAQ was developed for cisgender siblings and only included questions about family building desires (6 items). The TYFAQ was administered at both Wave 4 and Wave 5 to assess for changes in attitudes over time. Sample questions are displayed in Table 3. Additional demographic information was collected from participants via survey, including age, race/ethnicity, level of education, sexual orientation identity, and adoption status (Table 1).

Table 3.

Comparison of "Transgender Youth Fertility Attitudes Questionnaire" responses for transgender and gender expansive (TGE) adolescents and their caregivers in Wave 5.

| TGE Adolescent Items | Caregiver Items | Response, n |

TGE Adolescent

(n = 29) |

Caregiver (n = 44) |

Wilcoxon Z

(p-value) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| It is important to learn about how hormone treatment might affect my ability to have my own biological children. | It is important to learn about how hormone treatment might affect my child’s ability to have biological children. | Agree | 22 | 39 | 0.2514 |

| I don’t know | 3 | 1 | |||

| Disagree | 4 | 4 | |||

| I am aware that hormone treatment could cause issues with my ability to have my own biological children. | I am aware that hormone treatment could cause issues with my child’s ability to have their own biological children. | Agree | 28 | 41 | 1 |

| I don’t know | 0 | 2 | |||

| Disagree | 1 | 0 | |||

| I feel like I have people to talk to (like my doctor or therapist) about how hormone treatment could affect my ability to have my own biological children. | I feel like I have people to talk to (like a doctor or therapist) about how hormone treatment could affect my child’s ability to have biological children. | Agree | 26 | 39 | 1 |

| I don’t know | 2 | 3 | |||

| Disagree | 1 | 1 | |||

| I feel like I have people to talk to (like my doctor or therapist) about what I can do to have my own biological children if I’m taking hormones. | I would like to talk to someone about what my child can do to have biological children if they are taking hormones. | Agree | 26 | 11 | NA* |

| I don’t know | 2 | 9 | |||

| Disagree | 1 | 24 | |||

| I want to have kids someday. (This could be either your own biological kids or adopted kids). | I want my child to have kids someday. (This could be either their own biological kids or adopted kids). | Agree | 18 | 25 | 0.9753 |

| I don’t know | 5 | 15 | |||

| Disagree | 6 | 4 | |||

| If I have kids, it would be important to me that they are my biological kids. | If my child has kids, it is important to me that they are my child’s biological kids. | Agree | 5 | 0 | 0.0009 |

| I don’t know | 5 | 2 | |||

| Disagree | 19 | 41 | |||

| I would consider adoption someday. | I am open to my child adopting someday. | Agree | 27 | 44 | 0.309 |

| I don’t know | 1 | 0 | |||

| Disagree | 1 | 0 | |||

| My feelings about wanting my own biological child might change when I’m older. | My child’s feelings about wanting their own biological child might change in the future. | Agree | 13 | 31 | 0.028 |

| I don’t know | 9 | 9 | |||

| Disagree | 8 | 4 | |||

| I would be angry if the doctor didn’t tell me that hormone treatment could affect my ability to have my own biological children. | I would be angry if the doctor didn’t tell me that my child’s hormone treatment could affect their ability to have biological children. | Agree | 17 | 37 | 0.029 |

| I don’t know | 7 | 3 | |||

| Disagree | 5 | 4 | |||

| I am aware that there are options that would allow me to have my own biological child even if I’m on hormones. | I am aware that there are options that would allow my child to have biological children in the future (even if on hormones). | Agree | 23 | 34 | 0.9512 |

| I don’t know | 1 | 7 | |||

| Disagree | 5 | 3 | |||

| I feel pressured by my family to have my own biological child someday. | I would like my child to have their own biological child someday. | Agree | 2 | 14 | NA |

| I don’t know | 2 | 20 | |||

| Disagree | 25 | 10 | |||

| I would feel that I’m disappointing my family if I could not have my own biological child. | I would feel disappointed if my child could not have their own biological child. | Agree | 2 | 4 | 0.8183 |

| I don’t know | 1 | 2 | |||

| Disagree | 26 | 37 | |||

| I would consider medical procedures that would allow me to preserve my eggs or sperm in order to have my own biological children in the future. | I want my child to consider medical procedures that would preserve their eggs or sperm to be able to have their own biological children in the future. | Agree | 7 | 15 | 0.3054 |

| I don’t know | 8 | 13 | |||

| Disagree | 14 | 16 | |||

| My family wants me to preserve my eggs or sperm. | I want my child to preserve eggs or sperm. | Agree | 2 | 8 | 0.0767 |

| I don’t know | 9 | 17 | |||

| Disagree | 18 | 18 | |||

| How did you learn that hormone treatment could make it checkbox difficult for you to have your own biological child(ren)? (Check as many as are true.) |

How did you learn that hormone treatment could make it difficult for your child to have their own biological child(ren)? (Check as many as are true.) |

Doctor | 27 | 36 | |

| Internet | 19 | 18 | |||

| Parent/ Guardian |

8 | – | |||

| Spouse | – | 3 | |||

| Peers | 6 | 8 | |||

| Did not know | 0 | 4 |

p-value not provided as TGE and caregiver questions are not comparable.

Analytic methodology

Qualitative analysis

Interview transcripts were analyzed by a team of three research team members (i.e., “coders”) using a combination of three approaches: immersion/crystallization (Borkan, 1999), template organizing style (Crabtree & Miller, 1999), and thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006). First, the coding team familiarized themselves with the data by reading the interview transcripts from two families (6 participants total), representing TGE adolescent participants of different gender identities and ages, across Waves 4 and 5 (12 transcripts total), and creating memos about potential codes and themes. Then, using a template organizing approach, a codebook was developed with deductive and inductive codes, tested by the coding team on the 12 transcripts from the immersion/crystallization phase, and revised based on the testing. Then the coding team used the codebook to code the full set of interview transcripts using online mixed methods program Dedoose. Any new codes that were developed during coding were retroactively applied to previously coded transcripts, such that each transcript was analyzed using the complete codebook. After coding each family unit across both waves, coders wrote a family-level memo describing the notable themes as well as their perception of concordance within the family and change between the two waves.

After initial coding of all transcripts was complete, the coding team applied a “code cleaning” process to determine whether each code captured a distinct idea. As a result of this iterative process, some codes were combined and others were split into new codes or sub-codes. Finally, thematic analysis principles were used to consolidate data into major themes and sub-themes by creating groups of codes that were thematically related. Coding differences and thematic disagreements were resolved by discussion and consensus among the coding team. Ecological Systems Theory, which proposes that the family system is situated within and influenced by larger contexts including the community context and the societal/institutional context (Bronfenbrenner, 1986), was used as an analytical framework to help guide thematic development.

Quantitative analysis

The previously described TYFAQ was analyzed for descriptive purposes. Ordinal responses data from TGE adolescent-caregiver pairs, cisgender sibling-caregiver pairs, and TGE adolescent-cisgender sibling pairs were subsequently compared using the Mann-Whitney U test.

Results

Qualitative results

We identified eight themes that corresponded to different levels of the Ecological Systems Theory (Figure 1): (1) perceived reproductive potential, (2) reproductive identity, (3) communication about family building, (4) familial experiences and expectations, (5) community support and role models, (6) community expectations and norms, (7) medicalization of family building, and (8) socio-political factors. Themes 1 and 2, (perceived reproductive potential and reproductive identity), were classified as individual level. Themes 3 and 4 (communication about family building and familial experiences and expectations) were classified as family level. Themes 5 and 6 (community support and role models and community expectations and norms) were classified as community level. Themes 7 and 8 (medicalization of family building and socio-political factors) were classified as societal/institutional level.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model of themes representing the development of future family building desires for transgender and gender expansive (TGE) adolescents and their families.

Individual level themes

Theme 1: Perceived reproductive potential. Theme 1 reflected the individual’s gender identity, the impact of gender-affirming therapy on fecundity, and the sex/gender of current or future sexual partners. For many cisgender siblings, there was no hesitation about future biological parentage, as illustrated by a cisgender girl, age 21:

I definitely want kids of my own. I’d be devastated if I had [fertility problems], but I’d think about adoption if I weren’t able to have my own, or I’d consider IVF if it were an option. I really would do anything to have my own kids.

For TGE adolescents, considerations about future family building were more complicated. One transgender girl, age 19, summarized this complexity in the following way:

As an LGBT person, [I have to] think more about having children. For a lot of people in the world, you end up having children when you didn’t have to think about it and weren’t expecting to… And you have to put in a lot of effort to not do so. [But] I have to think about [it] and plan [it]. And it’s kind of…if anything, a decision and an option and a possibility that I really own and make my own.

For TGE adolescents, future reproductive potential was influenced by the accessibility of gender affirming treatment and information received from the medical community. Many TGE adolescents perceived that they were unable to have biological children. This caused significant distress for some, exemplified by a transgender girl, age 16: “I feel devastated that I’m not gonna be able to have children.”

Many TGE adolescents were told that gender-affirming treatment would preclude biological children, and they were open to alternative family building methods. One transgender boy, age 17, considered his hormonal therapy as he discussed future family-building:

I’ve been on testosterone for [about three or four years now]. So it’s too late to…save my eggs or anything. [Which is] kind of a bummer. I wish I had thought of that before… I’m hoping that I can either adopt or my partner will [want to] have a baby…I definitely want kids.

Some TGE adolescents and their families questioned the extent to which gender-affirming treatment led to decreased biological potential, as in this quote from a 19-year-old transgender boy’s mother:

The reason that you’re now ‘sterile’ is because you’re not ovulating! But the eggs are still there. I don’t know why it’s always been presented as…’You start T, and that’s it. You’re sterile.’ Because kinda sorta you’re not. Because the eggs are still there. So, there might be an option to have [biological] children.

Many TGE adolescents, siblings, and caregivers noted that future reproductive potential was also dependent on the gametes of future sexual partners. As one 21-year-old cisgender boy sibling said, “I mean, I like guys, so it’s like… you can’t get a guy pregnant.” A mother of a transgender boy, age 17, similarly described how her child’s family building path would depend on her child’s partner: “If he ends up with somebody assigned male at birth…there is this possibility that [my child could become] pregnant or carry a child.”

Theme 2: Reproductive identity. Theme 2 reflected the participant’s sense of self as it related to future family building. Many TGE adolescents described dissonance between future parenting desires and transgender identity development. One nonbinary adolescent, age 19, negotiated this conflict between fertility preservation and gender affirming treatment:

I have to decide … what’s more [important]: starting testosterone and freezing my eggs or not starting testosterone and keeping my eggs… I think I’d rather keep my eggs because testosterone isn’t something I need to be happy with my gender; it’s more so everybody else can…see how I feel… I don’t really necessarily care about how everyone else sees me as long as I’m happy with myself.

In contrast, a transgender girl, age 16, decided to prioritize the lifesaving benefits of gender-affirming therapy over future biological fertility:

I made the decision not to be able to have biological children a while ago and my logic was: do I either want the possibility [of having] children that [are] biologically related to me, or do I want to risk ruining my life by going through irreversible changes and never even live to the age where I’d be able to have children?

Other TGE adolescents described conflict between gender identity biological parenthood methods. A transgender boy, age 17, shared:

The very idea of me being able to get pregnant is what makes me [want to] throw up because of dysphoria, which has happened before. I would not mind if my partner wanted to be pregnant… but it gives me so much dysphoria even just imagining it, to the point where I’ve had to stay home before because I accidentally thought about it and I couldn’t move from my bed because I got too dysphoric.

Many adolescent participants expressed awareness that their current thoughts on family building were dynamic and could change in the future, as an 18-year-old transgender girl described “My grandmother wants me to have children someday and I said, ‘No, I really don’t [want to have children].’ [Then she said] ‘You’re young. You’ll change your mind.’ Eh, I could. I don’t disagree with her there.”

Some TGE participants expressed that their transgender identities would make them better parents than they might otherwise have been. A 17-year-old transgender boy explained

Honestly, I think [my transgender identity] made me want to have kids more because if I have a kid who is not cis and straight, I feel like I’ll be a better parent to know how to deal with that than perhaps someone who is cis and straight. I’m not saying that people who are cis and are straight aren’t gonna be good parents… I know my mom is [a good parent], and she says that she’s straight and she’s awesome. But…I think [if] I had more LGBT influence in my life before I got into high school…I would have been able to come out sooner.

Family level themes

Theme 3: Communication about family building. Theme 3 describes the conversations that did, or did not, occur within family units. Participants considered communication to be essential for future family building support. Many TGE participants described talking to their families at various stages of gender affirming treatment. One transgender girl, age 16 said “I have had conversations with my mom, both when I started puberty blockers and cross-sex hormones, and also just kind of recently, just [to] have a conversation about it.” Other participants described not having such conversations with their family given their youth: an 18-year-old nonbinary adolescent noted “I haven’t really talked about it with anyone because I’m only 18 [years old] and it’s not, like, something that would happen in the near future.”

Theme 4: Familial experiences and expectations. Theme 4 reflects the unique histories within each family and how they manifest into expectations, both explicit and inferred, for the adolescents. The experience of being adopted or having an adopted family member greatly impacted participants’ views of future family building options. One mother of an 18-year-old transgender girl described this influence:

I was brought up in [the] foster care system and it [was] awful. [It was] awful not having a family and there [are] a lot of kids out there that need a family. So, if they don’t [want to] have children, then I think that’s smart. And if they do, I just hope that they’re not pressured into it and it’s 100% their choice.

Adolescent participants described various degrees of family building pressure, both implicit and explicit, from their families. One participant, a 16-year-old non-binary adolescent, described their mother’s thoughts about family building:

I think one thing my mom always said is, not in like a super forceful way, but I think she really likes the idea of biological children, which makes sense because she had biological children, but it’s just not something I want to try and do by any means… I feel like she always sort of pushes that a little bit whenever she can, even though she’s understanding when I’m like, ‘I’m not interested in that prospect.’

Caregivers frequently expressed conflict between a desire for future biological grandchildren and prioritization of their TGE children’s happiness, health, and gender affirmation. One mother of a transgender boy, age 17, described expectations that many caregivers hold:

You know, you think, your children grow. They get married. They have children. Now that’s somebody else’s script. That’s a social construct that I no longer buy into. It’s sort of liberating. You know, I don’t have any unfair expectations of my children… I see so many other people say, ‘Well, you have to give me grandchildren.’ No, you have to do what’s right for you. If I’m blessed enough to have grandchildren, I will. But it’s not my decision to make.

Another mother of a 17-year-old nonbinary adolescent concluded

I want a happy, healthy, contributing member to society who is comfortable with themselves, doesn’t have dysphoria, and doesn’t have anxiety. And if that means I never have any grandkids, I don’t care. I want the rest, and I don’t have the rest right now.

Community level themes

Theme 5: Community support and role models. Theme 5 was related to the available community resources, including affirmation from friends, LGBTQ + groups, and medical organizations. Some participants noted the strength of community, comparing theirs a “chosen family.” As one mother of an 18-year-old nonbinary adolescent said

I think less specifically about [my child] having children but sort of about having a… rich relationship, a family that [they] forms however [they want], whether it’s kids or… a peer family or just a group that lives as a family.

Many participants described community role models for family-building options, such as one mother of a 17-year-old transgender boy:

We also have a good friend that runs a [local LGBTQ + adolescent camp]…and he’s transgender as well, and [he is] sort of [son]’s idol in a way because he runs this camp, he does a lot of public speaking, and he’s married, has a little girl, and he’s just such a great role model. So, it’s so exciting. Someday when that happens [for my child], it’s just gonna be just normal, right?

Theme 6: Community expectations and norms. Similar to the familial experiences and expectations theme (Theme 4), in Theme 6, participants were aware of the expectations and perceived norms within specific populations, such as the LGBTQ + community. A nonbinary adolescent, age 17, described community norms about family building:

I haven’t talked to many people outside of my family about [family building], except for my friends from like camp and they’re all supportive. Like all my friends from [LGBTQ + camp] basically all either want to adopt or be foster parents to help give back to the communities and be supportive parents, especially for kids who are LGBTQ+.

Society/institutional level themes

Theme 7: Medicalization of family building. Theme 7, identified as being on the societal/institutional level in the Ecological Systems Theory, This theme reflected experiences with medical providers and included TGE adolescents’ interests in future medical technology that might enable biological children in the future. Conversations with medical and mental health providers were a critical aspect of this theme, with participants describing varying levels of access. A nonbinary adolescent, age 17, described having these conversations:

With both endocrinologists, [the conversation about having children in the future] was about the risks of hormone blockers and testosterone, like pregnancy, childbirth, and the ability to have kids. And then with the therapist, it was partially the same thing but also about like what I wanna do in life and setting like a goal for the future.

A transgender boy, age 16, expressed a desire to have these conversations, saying “I haven’t talked to any doctors about [having children in the future]. I really want to.”

Many families who believed that biological children would not be possible for their TGE children hoped for medical advancements in the field of assisted reproductive technology. One transgender girl, age 19, said

It would be very nice if by the time I might potentially want to have children if I might be able to have a womb in which to carry said child, if that is a thing that science can do, you know, for trans people because they’ll work on it for cis people way before they work on it for trans people.

Theme 8: Socio-political factors. Theme 8 related to External forces, including geopolitical location, finances, and perception of safety, affect TGE adolescents’ plans for parenthood. Many TGE participants described cissexism as a barrier to future adoption, as one 17-year-old transgender boy explained

LGBT couples who aren’t trans are denied [adoption] because they’re gay or in a same-sex relationship. And it seemed like it might not be a possibility [for me]…and I know a thing about mental health and if you’ve had negative mental health, [then] it decreases your chance [of being able to adopt]. So if it really came down to it I would be open to having biological children just because it seems like it might be a more realistic option.

Caregivers expressed the fear of anti-transgender prejudice as well, as exemplified by the following quote from a mother of an 18-year-old nonbinary adolescent:

I guess there’s [going to be] be a certain level of judgment with [my trans child] and [their trans partner] if they [have kids together] because they’re trans. I have some [gay] friends who finally were able to adopt. They [had] their [adoption] party over the weekend and somebody just, like, a few days before the actual adoption went through, somebody reported them to the [Department of Health and Human Services].

In light of anticipated future prejudice, many caregivers also expressed hope for safety in the future, like this mother of a transgender girl, age 17: “So I just hope that they, you know, become parents [and] that their children have good opportunities and are in a safe, you know, a safe country, a safe community, just everyone [has] a good chance at happiness.”

Finances were a major factor when considering future fertility. Many people expressed that parenting is expensive. One nonbinary adolescent, age 19, said “Children are expensive. I mean, like, I was talking to my parents. I’m like, whoa, I didn’t realize I cost that much.” For TGE adolescents, particularly those assigned female at birth, the expense of fertility preservation was frequently noted. A transgender boy, age 16, described the cost of fertility preservation as a barrier:

The endocrinologist asked if I wanted to have kids in the future and stuff like that, and then egg freezing and… then we went to a place that does the whole egg freezing and all that, and we decided against it because we don’t have the time and money.

Quantitative results

Changes in family building desires over time

There was no statistical difference in TYFAQ answers between Waves 4 and 5 for any individual participant type, including TGE adolescents, cisgender siblings, and cisgender caregivers. Below, we describe results from Wave 5 data only.

Comparing TGE adolescents and cisgender caregivers

Responses to the TYFAQ comparing TGE adolescents and their caregivers can be found in Table 3. Caregivers were more likely than TGE adolescents to think TGE adolescents might change their minds about wanting biological children in the future (70% vs. 44%, p = 0.028) and more likely than TGE adolescents to say they would be angry if doctors did not disclose that gender-affirming hormone therapy could impact future fertility (84% vs. 58%, p = 0.029). Notably, caregivers were more likely than TGE adolescents to disagree that it is important for their TGE adolescents to have biological children (95% vs. 65%, p = 0.001).

Comparing TGE adolescents and cisgender siblings

Responses comparing TGE adolescents and cisgender siblings can be found in Table 4. TGE adolescents were more likely than cisgender siblings to report that they would consider adoption someday (93% vs. 54%, p = 0.007). Cisgender siblings were more likely than TGE adolescents to believe that it is important to have biological children (65.5% vs. 27%, p = 0.05). Comparing heterosexual adolescents (both TGE and cisgender) to those who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, or queer (LGBQ), heterosexual adolescents were more likely to say it is important to have biological children in the future (77% vs. 18%, p = 0.002). TGE adolescents in the current study who had no outside LGBTQ + support were more likely to say their parents would be disappointed if they did not have biological children (25% vs 0%, p = 0.003), and TGE adolescents who participated in TGE-specific summer camps were more likely to say they would be open to adoption someday (100% vs 75%, p = 0.02).

Table 4.

comparison of "Transgender Youth Fertility Attitudes Questionnaire" responses for transgender and gender expansive (TGE) adolescents and their cisgender siblings in Wave 5.

| TGE Adolescent Items | Cisgender Adolescent Items | Response, n | TGE Adolescent (n = 29) | Cisgender Sibling (n = 11) |

Wilcoxon Z

(p-value) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I want to have kids someday. (This could be either your own biological kids or adopted kids). | I want to have kids someday. (This could be either your own biological kids or adopted kids). | Agree | 18 | 7 | 0.8497 |

| I don’t know | 5 | 3 | |||

| Disagree | 6 | 1 | |||

| If I have kids, it would be important to me that they are my biological kids. | If I have kids, it would be important to me that they are my biological kids. | Agree | 5 | 3 | 0.0402 |

| I don’t know | 5 | 4 | |||

| Disagree | 19 | 4 | |||

| I would consider adoption someday. | I would consider adoption someday. | Agree | 27 | 6 | 0.0216 |

| I don’t know | 1 | 5 | |||

| Disagree | 1 | 0 | |||

| My feelings about wanting my own biological child might change when I’m older. | My feelings about wanting my own biological child might change when I’m older. | Agree | 13 | 5 | 0.9588 |

| I don’t know | 9 | 4 | |||

| Disagree | 7 | 2 | |||

| I feel pressured by my family to have my own biological child someday. | I feel pressured by my family to have my own biological child someday. | Agree | 2 | 1 | 0.8498 |

| I don’t know | 2 | 1 | |||

| Disagree | 25 | 8 | |||

| I would feel that I’m disappointing my family if I could not have my own biological child. | I would feel that I’m disappointing my family if I could not have my own biological child. | Agree | 2 | 0 | 0.1509 |

| I don’t know | 1 | 4 | |||

| Disagree | 26 | 7 |

Comparing cisgender siblings and cisgender caregivers

Responses comparing cisgender siblings and cisgender caregivers can be found in Table 5. Caregivers were more likely than cisgender adolescents to say it is not important for cisgender adolescents to have biological children (94% vs. 27%, p < 0.001). Caregivers also were more likely than cisgender children to say they were open to cisgender adolescents adopting (100% vs. 54%, p = 0.007).

Table 5.

Comparison of "Transgender Youth Fertility Attitudes Questionnaire" responses for caregiver(s) and their cisgender adolescents in Wave 5.

| Caregiver Items | Cisgender Adolescent Items | Response, n |

Caregiver

(n = 44) |

Cisgender Sibling (n = 11) | Wilcoxon Z (p-value) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I want my child to have kids someday. (This could be either their own biological kids or adopted kids). | I want to have kids someday. (This could be either your own biological kids or adopted kids). | Agree | 10 | 7 | 0.7395 |

| I don’t know | 7 | 3 | |||

| Disagree | 2 | 1 | |||

| If my child has kids, it is important to me that they are my child’s biological kids. | If I have kids, it would be important to me that they are my biological kids. | Agree | 0 | 4 | 0.0003 |

| I don’t know | 1 | 4 | |||

| Disagree | 18 | 3 | |||

| I am open to my child adopting someday. | I would consider adoption someday. | Agree | 19 | 6 | 0.0065 |

| I don’t know | 0 | 5 | |||

| Disagree | 0 | 0 | |||

| My child’s feelings about wanting their own biological child might change in the future. | My feelings about wanting my own biological child might change when I’m older. | Agree | 12 | 5 | 0.3552 |

| I don’t know | 6 | 4 | |||

| Disagree | 1 | 2 | |||

| I would feel disappointed if my child could not have their own biological child. | I would feel that I’m disappointing my family if I could not have my own biological child. | Agree | 3 | 0 | 0.8651 |

| I don’t know | 2 | 4 | |||

| Disagree | 14 | 7 |

Comparing caregiver desires for TGE adolescents vs. cisgender adolescents

Caregiver desires for family building for TGE and cisgender adolescents were concordant (i.e., there were no statistically significant differences in responses) for both gender identity groups.

Discussion

The goal of this study was to contextualize how TGE adolescents and their families describe future family building preferences according to the Ecological Systems Theory, which situates family building, sometimes considered an individual-level choice, within the larger contexts of family, community, and society. For TGE adolescents, the development of the reproductive self should not be separated from transgender identity. While there were no statistically significant survey differences between TGE and cisgender adolescents regarding parenthood goals, qualitative interviews clarified that many TGE adolescents prioritize gender affirmation over fertility preservation. This contrasted with cisgender siblings, who frequently expressed that having biological children was part of their life plans. In a prior study, TGE adolescents’ self-reported priorities were good health, excelling in school and work, and having close friends (Chiniara et al., 2019). As in the current study, their collective lowest priority was fertility preservation, even though most TGE adolescents wanted to have children eventually. While a lack of prioritization may be appropriate for non-medicalized cisgender adolescents, lack of fertility planning for TGE adolescents could prove detrimental to the TGE adolescent’s future goals.

For many TGE adolescents, a self-preserving desire for gender affirming medical interventions and their attendant psychosocial benefits takes priority over reproductive drives (Liu et al., 2019; Wakefield et al., 2019). Psychological comorbidities experienced by some members of the TGE community, such as a sense of foreshortened future, family disruption, and experiences of rejection, also impede successful planning for future fertility and parenthood (Chen et al., 2019). Gender dysphoria and comfort/familiarity with adoption are other fertility-related considerations (Chen et al., 2019; Chiniara et al., 2019). The current study echoed these earlier findings. In the TYFAQ survey data, approximately 75% of the TGE adolescents agreed that it is important to learn how hormone therapy might impact the ability to have biological children, and all but one of the 29 TGE adolescents were aware that hormonal affirmation could impact fecundity. Despite this, only one participant discussed delaying hormone therapy to consider fertility preservation in the qualitative data. These findings highlight the importance of conversations between medical and mental health providers and TGE adolescents and their caregivers regarding the impact of fertility preservation on gender affirmation goals and of gender-affirming treatments on reproductive potential.

As in prior studies (cite?), we found that TGE individuals’ fertility goals may change depending on partner-related factors. For example, sperm preservation might be considered for a cisgender female partner to be able to carry a biological pregnancy (Brik et al., 2019). Other research has shown that TGE individuals who identify as nonbinary are more likely to desire pregnancy than TGE individuals with binary identities (i.e., transgender man, transgender woman) (Brik et al., 2019). In both the current study’s survey and interview data, participants expressed concerns that TGE adolescents might regret limiting family building options. In the survey, caregivers were statistically more likely than their TGE adolescent to express this concern; however, it is notable that almost half of the TGE adolescents acknowledged the potential for future regret. Continued conversations are needed considering sexual orientation and potential partner gametes when discussing TGE adolescents’ family building options.

At the level of the family, two major qualitative themes developed, with significant overlap: communication about family building and familial experiences and expectations. Parental expectations were often influenced by caregivers’ own experiences in the greater context of the community and society. For example, in the interview data, caregivers discussed their personal experiences with being adopted or adopting children themselves, and validated adoption for their child(ren) as a preferred family building method. In the survey data, while TGE adolescents were overall more likely to agree that they would consider adoption someday, more than half of the cisgender adolescents stated that they would consider adoption. Most notably, all of the adolescents that were either adopted or had adopted parents stated that they would consider adoption someday.

In the current study, the family was a major affirmer of adolescents’ reproductive identities. Survey data showed that there is a high level of concordance between TGE adolescents and caregivers with regard to family building desires. However, during the interviews, many TGE adolescents expressed that they did not always feel caregivers supported their future family building desires. These adolescents tended to report not having conversations with family members and others outside the family and endorsed having few resources for making decisions about future family building while feeling pressure from their families and a high degree of perceived discordance.

At the community level, two major qualitative themes developed, community support and role models and community expectations and norms. The LGBTQ + community, specifically the TGE population, was particularly influential for TGE adolescents – some studies suggest that LGBTQ people, specifically TGE people, are more open to having non-biological children or not having children, compared with cisgender heterosexual counterparts (Chen et al., 2019). Between one half and two thirds of TGE individuals in recent studies agreed that a biological relationship was not an important factor in their parenthood goals (Riggs & Bartholomaeus, 2018; Kyweluk et al., 2018). In one study, 71% of participants were considering adoption as a method of family building (Chen et al., 2018), which aligns with findings from other studies describing the desire to adopt as a way to meet a global parent shortage (Kyweluk et al., 2018). In the same survey, 31% of TGE participants preferred family building through adoption compared with 25% desiring parenthood achieved through sexual intercourse and pregnancy (Kyweluk et al., 2018). These findings were echoed in both the survey data and the interview data from the current study.

In the survey data, LGBTQ+-identified adolescents were less likely than their heterosexual counterparts to report that having biological children is important, and TGE adolescents were more likely to be open to adoption in comparison to their cisgender siblings. Furthermore, TGE adolescents in the current study who had no outside LGBTQ + support were more likely to say their parents would be disappointed if they did not have biological children, and TGE adolescents who participated in TGE-specific summer camps were more likely to say they would be open to adoption someday. In the interviews, TGE adolescents in the current study frequently described family building discussions with LGBTQ + peer groups, and cisgender adolescents in the current study frequently described family building discussions with their cisgender peers. These findings suggest that the desire to parent is likely learned from and affirmed at not only the level of the family but also the level of the community.

At the level of society/institutions, the qualitative theme of sociopolitical factors developed. In the interviews, both TGE adolescents and cisgender siblings expressed a desire for “stability” in the future related to parenthood decisions, largely in economic terms. TGE adolescents, however, more frequently discussed the impact of TGE-related stigma on future parenthood goals. In prior studies investigating why many TGE individuals expressed no desire for fertility preservation, a leading factor was stigma against sexual and gender minority parents, including stigma against TGE parenting abilities and lack of legal support [8].

There was significant overlap between sociopolitical factors and the medicalization of family building, specifically regarding the expense of fertility preservation. In survey data, seven of the 29 TGE participants would consider undergoing fertility preservation and nine of the participants were unsure about fertility preservation. Despite these numbers, only three of the TGE adolescents in the current study actually underwent fertility treatment. Cost of fertility preservation is one of the most commonly cited barriers to biological parenthood among TGE adolescents (Chen et al., 2019; Rafferty, 2019). The fact that this cost is highly differential based on reproductive anatomy is not lost on TGE people: patients assigned female at birth are less likely to seek fertility preservation than patients assigned male at birth given the exorbitant fees associated with ovarian stimulation and oocyte cryopreservation compared to sperm collection and cryopreservation (Tishelman et al., 2019). This trend was observed in the current study as well, as two of the three TGE adolescents who underwent fertility preservation were trans girls.

Lastly, the qualitative theme of medicalization of family building demonstrated the significant hope many families maintain that medical advancements might enable family building in the future, and that medical providers can help families navigate TGE adolescent’s fertility preservation. In the interviews, families of some TGE girls in particular recognized desires among their daughters to carry future pregnancies and mentioned options on the horizon, like uterus transplantation, that would support this. The families of TGE adolescents who pursued gender affirming hormone therapy after the use of puberty blockers that prevented gonadal maturation discussed the possibility of harvesting gonadal tissue rather than gametes in the future. While these aspirations were shared by several families, it is important to highlight that in the survey data, only 79% of TGE adolescents and 77% of their caregivers were aware that there were options to have biological children in the future despite being on hormone therapy.

This research had limitations: the sample was geographically homogenous, and while the sample size was appropriate for qualitative analysis, it was too small to allow for strong conclusions to be drawn from the quantitative survey data. Quantitative survey data were included for the purpose of triangulation and to add additional context to the qualitative analysis.

Furthermore, while perceptions of caregiver support for the TGE adolescent varied across by family, sufficient familial acceptance and support was present to facilitate familial participation in the study.

Despite these limitations, to our knowledge this is the first community-based longitudinal mixed methods study to examine TGE future family building in families with TGE adolescents from multiple family members’ perspectives. Future research should be conducted to develop tools to help TGE adolescents and their families navigate discussions about and considerations regarding future family building.

Utilizing Ecological Systems Theory, we characterized the greater context that influences TGE adolescents’ and their families’ developing ideas about future family building. Medical and mental health providers should be aware of these complex dynamics and how they, as providers, play a significant role in the greater societal context. Providers should engage in developmentally appropriate conversations about fertility preservation and future family building options early and regularly with TGE adolescents and their families. Furthermore, TGE adolescents and their families should be encouraged to discuss the process of family building. When appropriate, TGE adolescents and their families should be provided with community resources that highlight the diverse ways in which people can build community and family.

This research adds to the growing body of literature demonstrating that the cost of assisted reproductive technology is a major barrier to family building for TGE people. Insurance coverage for these treatments varies widely and there are significant out-of-pocket costs associated with the subsequent maintenance of cryopreserved gametes. Advocating for policy changes that will increase insurance coverage of assisted reproductive technologies is critical for TGE future family building. Improving the affordability and availability of fertility preservation services will ensure that TGE individuals can achieve biological parenthood, if they desire it.

Funding Statement

The TTFN Project was funded by grants from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development (K99R00HD082340) and the Boston Children’s Hospital Aerosmith Endowment Fund, both awarded to Dr. Katz-Wise. Dr. Katz-Wise was also funded by the Maternal and Child Health Bureau, Health Resources and Services Administration (Leadership Education in Adolescent Health project 6T71-MC00009).

The TTFN Project was funded by grants from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development (K99R00HD082340) and the Boston Children’s Hospital Aerosmith Endowment Fund, both awarded to Dr. Katz-Wise. Dr. Katz-Wise was also funded by the Maternal and Child Health Bureau, Health Resources and Services Administration (Leadership Education in Adolescent Health project 6T71-MC00009).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. The authors are willing to allow the journal to review their data if requested. Raw data were generated at Boston Children’s Hospital. Derived data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author SKW on request.

References

- Borkan, J. (1999). Immersion/crystallization. In Crabtree B. F. & Miller W. L. (Eds.), Doing qualitative research (pp. 179–194). Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. [Database] 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brik, T., Vrouenraets, L. J., Schagen, S. E., Meissner, A., de Vries, M. C., & Hannema, S. E. (2019). Use of fertility preservation among a cohort of transgirls in the Netherlands. The Journal of Adolescent Health: Official Publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine, 64(5), 589–593. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2018.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1986). Ecology of the family as a context for human development: Research perspectives. Developmental Psychology, 22(6), 723–742. 10.1037/0012-1649.22.6.723 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, D., Kolbuck, V. D., Sutter, M. E., Tishelman, A. C., Quinn, G. P., & Nahata, L. (2019). Knowledge, practice behaviors, and perceived barriers to fertility care among providers of transgender healthcare. Journal of Adolescent Health, 64(2), 226–234. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2018.08.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, D., Kyweluk, M. A., Sajwani, A., Gordon, E. J., Johnson, E. K., Finlayson, C. A., & Woodruff, T. K. (2019). Factors affecting fertility decision-making among transgender adolescents and young adults. LGBT Health, 6(3), 107–115. 10.1089/lgbt.2018.0250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, D., Matson, M., Macapagal, K., Johnson, E. K., Rosoklija, I., Finlayson, C., Fisher, C. B., & Mustanski, B. (2018). Attitudes toward fertility and reproductive health among transgender and gender-nonconforming adolescents. The Journal of Adolescent Health: Official Publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine, 63(1), 62–68. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2017.11.306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiniara, L. N., Viner, C., Palmert, M., & Bonifacio, H. (2019). Perspectives on fertility preservation and parenthood among transgender youth and their parents. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 104(8), 739–744. 10.1136/archdischild-2018-316080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman, E., Bockting, W., Botzer, M., Cohen-Kettenis, P., DeCuypere, G., Feldman, J., Fraser, L., Green, J., Knudson, G., Meyer, W. J., Monstrey, S., Adler, R. K., Brown, G. R., Devor, A. H., Ehrbar, R., Ettner, R., Eyler, E., Garofalo, R., Karasic, D. H., … Zucker, K. (2012). Standards of care for the health of transsexual, transgender, and gender-nonconforming people, version 7. International Journal of Transgender Health, 13(4), 165–232. 10.1080/15532739.2011.700873 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crabtree, B. F., & Miller, W. L. (1999). Using codes and code manuals. In Crabtree B. F. & Miller W. L. (Eds.), Doing qualitative research (2nd ed., pp. 163–177). Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Katz-Wise, S. L., Ehrensaft, D., Vetters, R., Forcier, M., & Austin, S. B. (2018). Family functioning and mental health of transgender and gender-nonconforming youth in the trans teen and family narratives project. The Journal of Sex Research, 55(4–5), 582–590. 10.1080/00224499.2017.1415291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz-Wise, S. L., Godwin, E. G., Parsa, N., Brown, C. A., Pullen Sansfaçon, A., Goldman, R., MacNish, M., Rosal, M. C., & Austin, S. B. (2020). Using family and ecological systems approaches to conceptualize family-and community-based experiences of transgender and/or nonbinary youth from the trans teen and family narratives project. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, Advance online publication. 10.1037/sgd0000442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz-Wise, S. L., Pullen Sansfaçon, A., Bogart, L. M., Rosal, M. C., Ehrensaft, D., Goldman, R. E., & Bryn Austin, S. (2019). Lessons from a community-based participatory research study with transgender and gender nonconforming youth and their families. Action Research, 17(2), 186–207. 10.1177/1476750318818875 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kyweluk, M. A., Sajwani, A., & Chen, D. (2018). Freezing for the future: Transgender youth respond to medical fertility preservation. International Journal of Transgender Health, 19(4), 401–416. 10.1080/15532739.2018.1505575 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W., Schulster, M. L., Alukal, J. P., & Najari, B. B. (2019). Fertility preservation in male to female transgender patients. The Urologic Clinics of North America, 46(4), 487–493. 10.1016/j.ucl.2019.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyngstad, T. H., & Prskawetz, A. (2010). Do siblings’ fertility decisions influence each other? Demography, 47(4), 923–934. 10.1007/BF03213733 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nahata, L., Tishelman, A. C., Caltabellotta, N. M., & Quinn, G. P. (2017). Low fertility preservation utilization among transgender youth. The Journal of Adolescent Health: Official Publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine, 61(1), 40–44. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.12.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olden, K. (1998). The complex interaction of poverty, pollution, health status. The Scientist, 12(4), 7. [Google Scholar]

- Rafferty, J. (2019). Fertility preservation outcomes and considerations in transgender and gender-diverse youth. Pediatrics, 144(3), 1–2. 10.1542/peds.2019-2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riggs, D. W., & Bartholomaeus, C. (2018). Fertility preservation decision making amongst Australian transgender and non-binary adults. Reproductive Health, 15(1), 181. 10.1186/s12978-018-0627-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stark, B., Hughto, J. M., Charlton, B. M., Deutsch, M. B., Potter, J., & Reisner, S. L. (2019). The contraceptive and reproductive history and planning goals of trans-masculine adults: A mixed-methods study. Contraception, 100(6), 468–473. 10.1016/j.contraception.2019.07.146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strang, J. F., Jarin, J., Call, D., Clark, B., Wallace, G. L., Anthony, L. G., Kenworthy, L., & Gomez-Lobo, V. (2018). Transgender youth fertility attitudes questionnaire: Measure development in nonautistic and autistic transgender youth and their parents. Journal of Adolescent Health, 62(2), 128–135. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2017.07.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tishelman, A. C., Sutter, M. E., Chen, D., Sampson, A., Nahata, L., Kolbuck, V. D., & Quinn, G. P. (2019). Health care provider perceptions of fertility preservation barriers and challenges with transgender patients and families: Qualitative responses to an international survey. Journal of Assisted Reproduction and Genetics, 36(3), 579–588. 10.1007/s10815-018-1395-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakefield, B. W., Boguszewski, K. E., Cheney, D., & Taylor, J. F. (2019). Patterns of fertility discussions and referrals for youth at an interdisciplinary gender clinic. LGBT Health, 6(8), 417–421. 10.1089/lgbt.2019.0076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]