Abstract

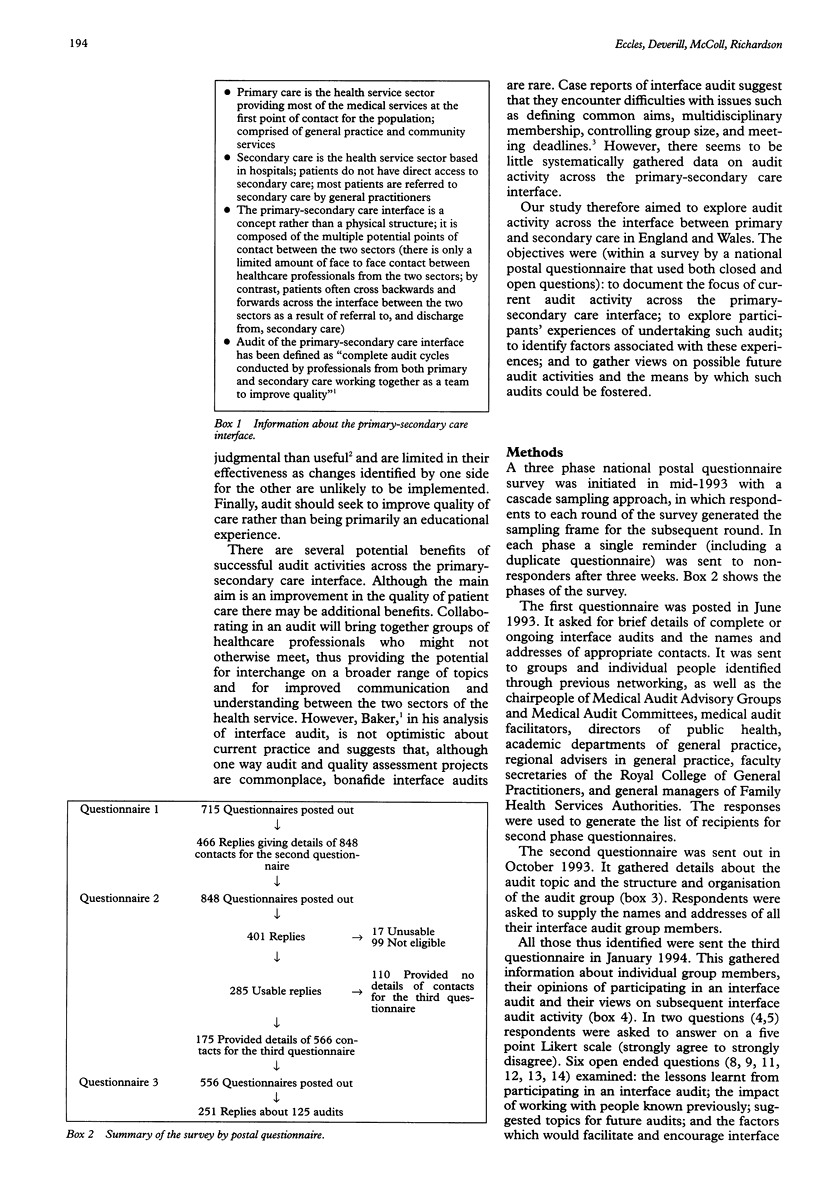

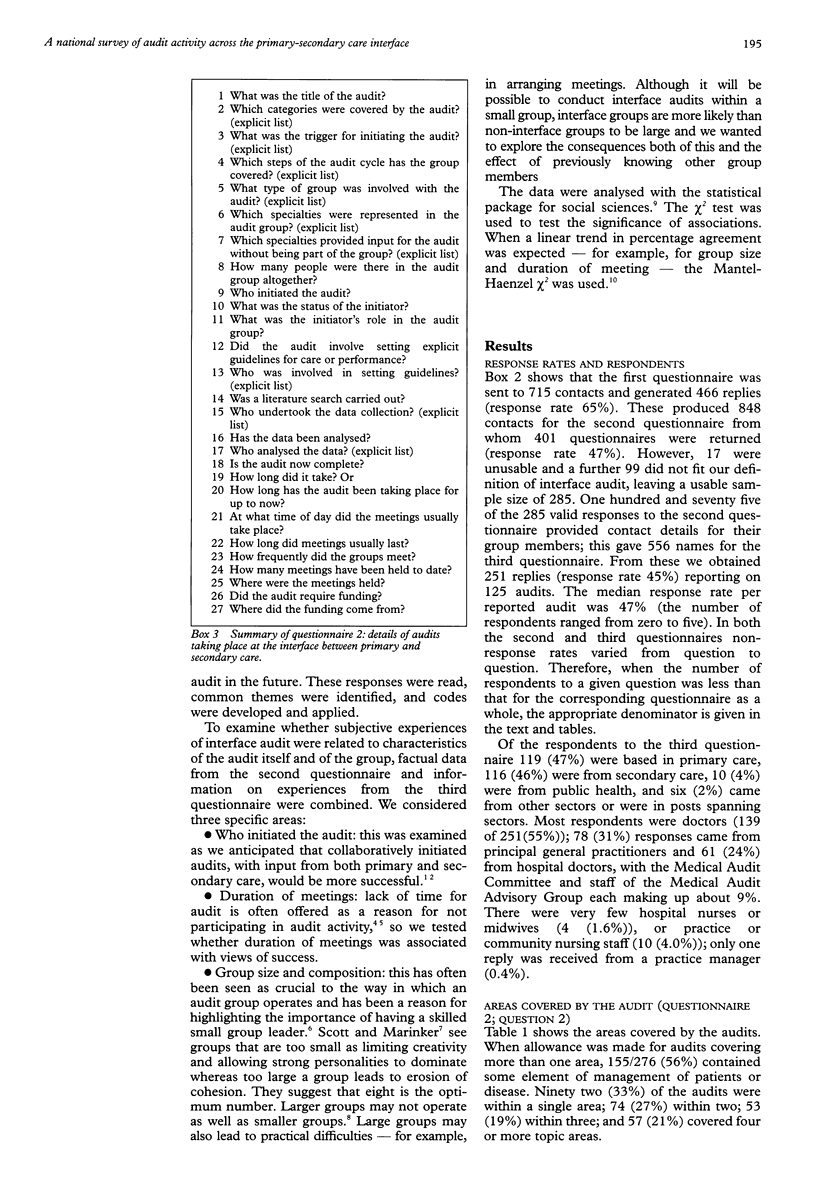

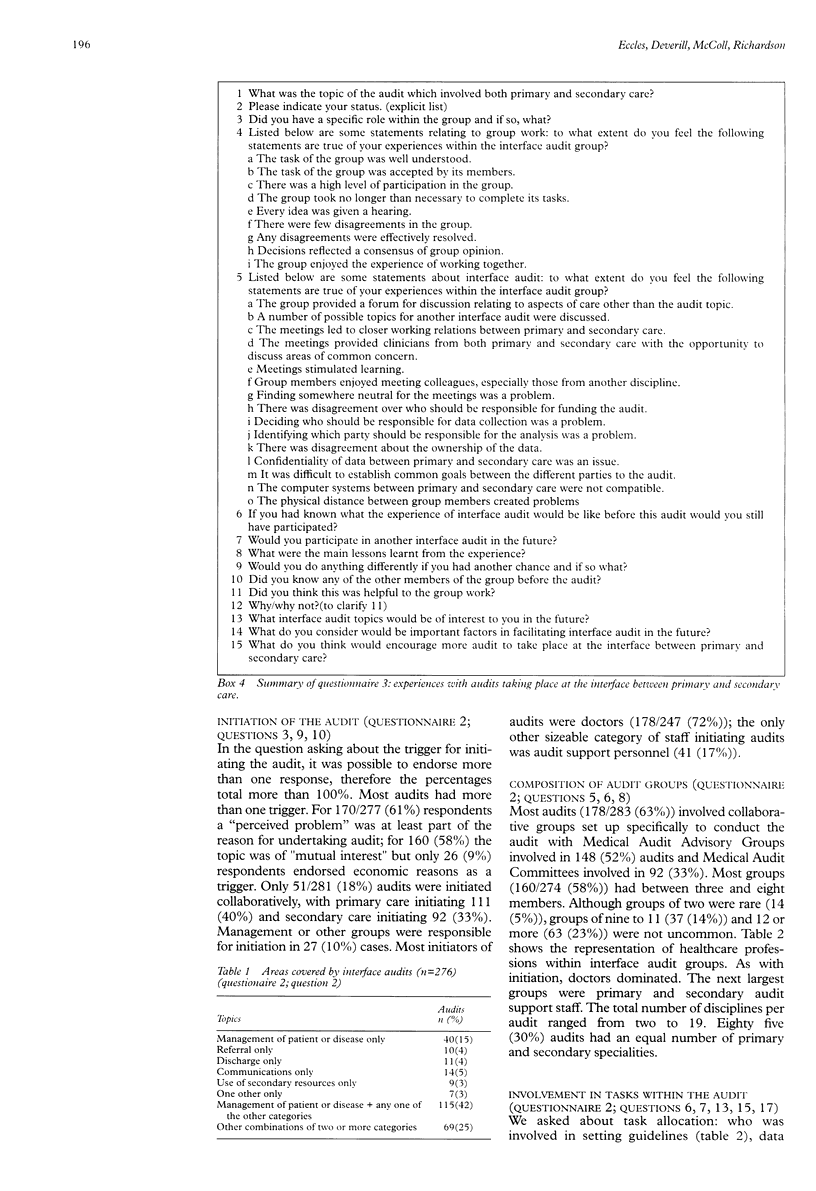

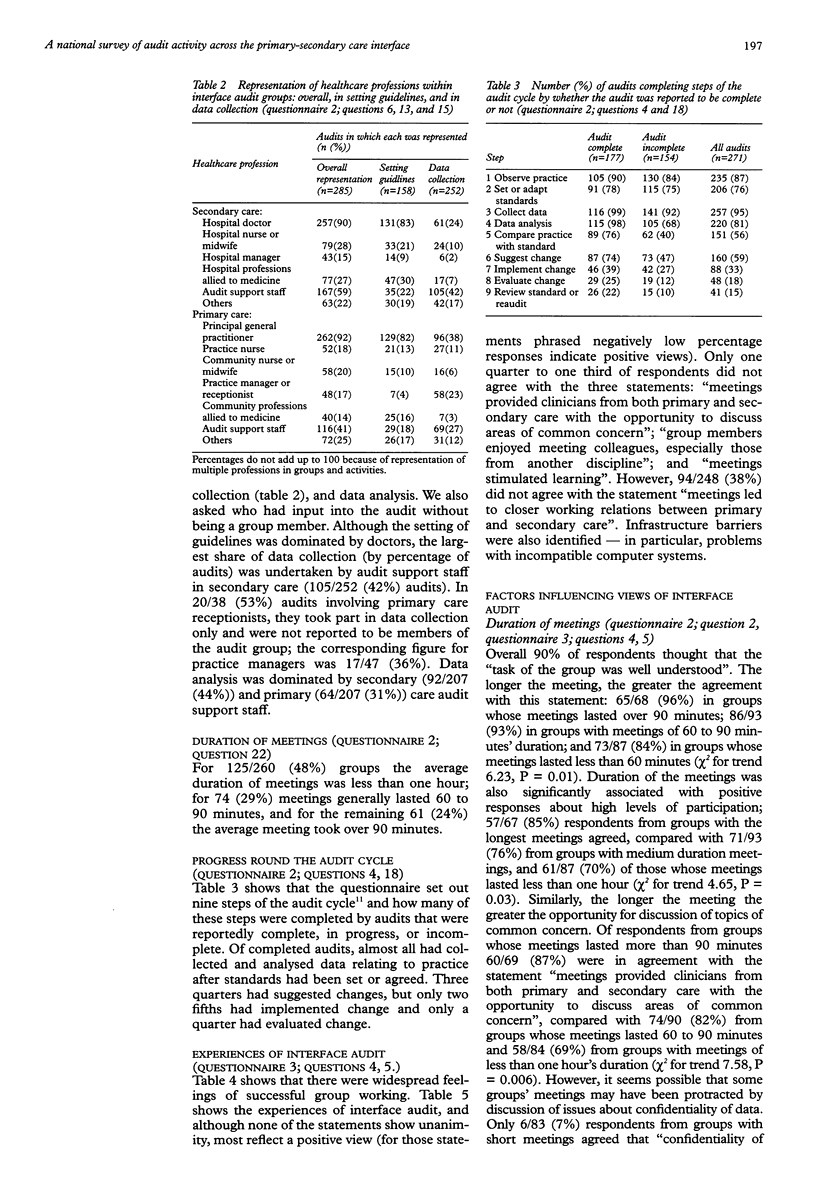

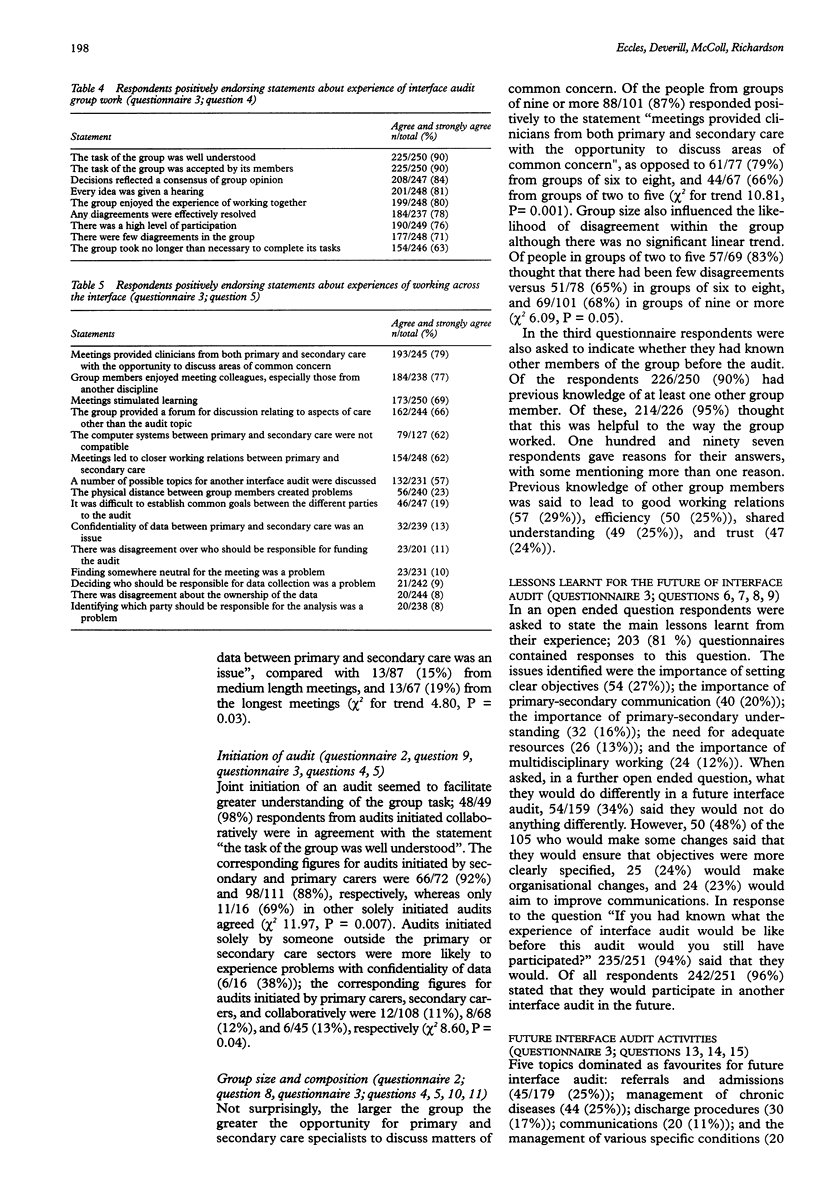

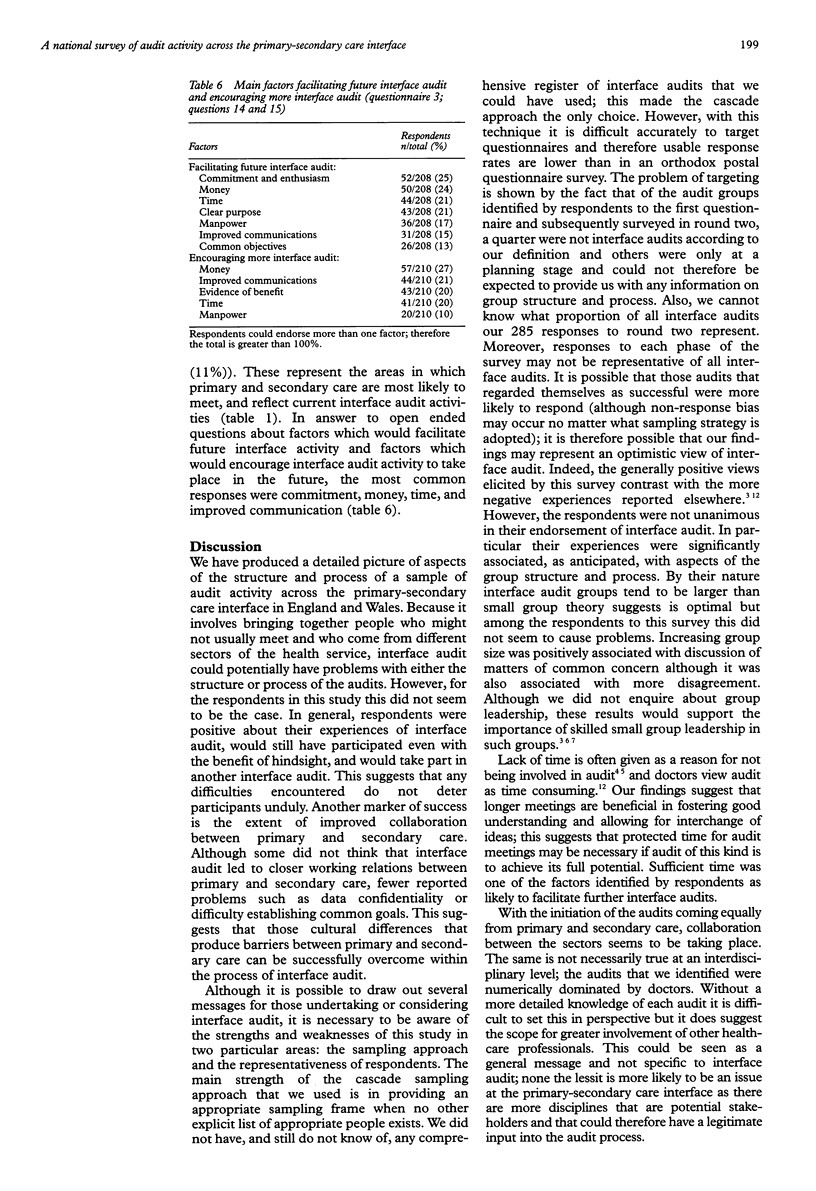

OBJECTIVE: To document the nature of audit activity at the primary-secondary care interface; to explore participants' experiences of undertaking such interface audit; to identify factors associated with these experiences; and to gather views on future interface audit activities. DESIGN: A three phase national survey by postal questionnaire with a cascade sampling approach. SETTING: England and Wales. RESULTS: Response rates were: 65% to the first questionnaire; 34% to the second questionnaire; and 45% to the third questionnaire. 56% of the audits covered some element of management of patients or disease; only 33% of the audits were within a single topic area. Most audits had more than one trigger: for 61% the trigger was a perceived problem; for 58% it was of mutual interest. Only 18% of audits were initiated collaboratively; doctors were the most frequent initiators (72%), and most audits (63%) involved collaborative groups convened specifically for the audit. 58% of groups had between three and eight members, 23% had 12 or more. Doctors were the most frequent group members. There was differential involvement of group members in various group tasks; the setting of guidelines was highly dominated by doctors. Of reportedly complete audits, only two fifths had implemented change and only a quarter had evaluated this change. There was widespread feeling of successful group work, with evidence of benefit in terms of the two sectors of care being able to consider issues of mutual concern. Levels of understanding of the group task and of participation were positively related to the duration of meetings. Joint initiation of audits facilitated greater understanding of the group task. Larger group sizes allowed primary and secondary carers to discuss issues of common concern; however, larger groups were more likely to experience disagreements. Having previously worked with group members increased trust and good working relations. The main lessons learnt from the experience included the importance of setting clear objectives and good communications between primary and secondary carers. Factors identified as important for future audit activity at the primary-secondary care interface included commitment, enthusiasm, time, and money. CONCLUSIONS: Audit at the primary-secondary care interface is taking place on a wide scale and has been an enjoyable experience for most of the respondents in this study. IMPLICATIONS: Despite being a positive experience most audits stopped short of implementing change. Care must be taken to complete the audit cycle if audit at the primary-secondary care interface is to move beyond the roles of education and professional development and to fulfil its potential in improving the quality of care.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Baker R. What is interface audit? J R Soc Med. 1994 Apr;87(4):228–231. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryce F. C., Clayton J. K., Rand R. J., Beck I., Farquharson D. I., Jones S. E. General practitioner obstetrics in Bradford. BMJ. 1990 Mar 17;300(6726):725–727. doi: 10.1136/bmj.300.6726.725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eccles M., Clapp Z., Grimshaw J., Adams P. C., Higgins B., Purves I., Russell I. Developing valid guidelines: methodological and procedural issues from the North of England Evidence Based Guideline Development Project. Qual Health Care. 1996 Mar;5(1):44–50. doi: 10.1136/qshc.5.1.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Firth-Cozens J. Building teams for effective audit. Qual Health Care. 1992 Dec;1(4):252–255. doi: 10.1136/qshc.1.4.252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MANTEL N., HAENSZEL W. Statistical aspects of the analysis of data from retrospective studies of disease. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1959 Apr;22(4):719–748. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McColl E., Newton J., Hutchinson A. An agenda for change in referral--consensus from general practice. Br J Gen Pract. 1994 Apr;44(381):157–162. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer J. Audit in general practice: where do we go from here? Qual Health Care. 1993 Sep;2(3):183–188. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2.3.183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]