Abstract

BACKGROUND

Nocardia cyriacigeorgica represents a rare cause of cerebral abscesses. Rarer still are brainstem abscesses caused by this bacterial species in immunocompetent hosts. In fact, only one such brainstem abscess case has been described in the neurosurgical literature to our knowledge to date. Herein, a case of Nocardia cyriacigeorgica abscess in the pons is reported, as well as a description of its surgical evacuation via the transpetrosal fissure, middle cerebellar peduncle approach. The authors review the utility of this well-described approach in treating such lesions safely and effectively. Finally, the authors briefly review, compare, and contrast related cases to this one.

OBSERVATIONS

Augmented reality is additive to and useful for well-described safe entry corridors to the brainstem. Despite surgical success, patients may not regain previously lost neurological function.

LESSONS

The transpetrosal fissure, middle cerebellar peduncle approach is safe and effective in evacuating pontine abscesses. Augmented reality guidance supplements but does not replace thorough knowledge of operative anatomy for this complex procedure. A reasonable degree of suspicion for brainstem abscess is prudent even in immunocompetent hosts. A multidisciplinary team is critical to the successful treatment of central nervous system Nocardiosis.

Keywords: brainstem, Nocardia, middle cerebellar peduncle

ABBREVIATIONS: AR = augmented reality, CNS = central nervous system, DWI = diffusion-weighted imaging, MRI = magnetic resonance imaging

Nocardia spp. are aerobic gram-positive bacilli that are commonly found in decomposing soil, foliage, and water. They are uncommon pathogens in human subjects.1,2 Nocardiosis represents the opportunistic infection caused by Nocardia spp. that is limited to cutaneous lesions in immunocompetent hosts but can cause extensive pulmonary lesions, and even intracranial abscesses, in immunocompromised hosts.1,3,4 Nocardia intracranial abscesses are exceedingly rare, present in less than 2% of all nocardiosis cases, but the mortality rate of these abscesses is three times higher than other intracranial abscesses.5–7 There have been isolated reports of brainstem involvement in disseminated central nervous system (CNS) infection, but very few with solitary abscess of the brainstem (Table 1). We report a case of an immunocompetent patient with a pontine abscess caused by N. cyriacigeorgica, which was evacuated via the retrosigmoid middle cerebellar peduncle approach.8

TABLE 1.

Reported N. cyriacigeorgica cases

| Authors & Year | Sex | Age (yrs) | Health Status | Presenting Symptom(s) | Location(s) | Abscess Size (cm) | Antibiotic Regimen | Surgical Approach/Intervention | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gabay et al., 20226 |

M |

75 |

Former smoker, ischemic heart disease, hypertension, CKD, dyslipidemia, asthma, hypoparathyroidism |

Altered mental status, lt hand apraxia, hemianopsia |

Rt parietal cerebrum |

NS |

Empirical: ceftriaxone (2 g × 1/d), metronidazole (500 mg × 3/d); culture-guided: meropenem (2 g × 3/d), TMP/SMX (240 mg × 3/d) |

Supratentorial craniotomy/evacuation |

Clinical improvement after 6 wks |

| Browne et al., 202117 |

M |

77 |

Hypertension, diabetes, tobacco use (daily) |

Cough, headache, fever, blurred vision, dysphonia, gait instability, impaired consciousness |

Lt parieto-occipital cerebrum |

2.9 |

Ceftriaxone (IV), TMP/SMX (oral) |

NA |

NS |

| Karan et al., 20195 |

M |

70 |

Healthy |

Generalized epileptic seizure |

Lt precentral cerebrum |

3 |

TMP/SMX, ceftriaxone |

Supratentorial craniotomy/evacuation |

Gradual clinical improvement (NS) |

| Khorshidi et al., 20183 |

F |

73 |

Diabetes |

Severe headache, shortness of breath, fever, vomiting |

Lt frontal cerebrum |

NS |

NS |

NS |

NS |

| Garcia et al., 20157 |

M |

77 |

Pulmonary tuberculosis at 19 yrs old, daily prednisone (30 mg/day), myasthenia gravis, thymectomy |

Night sweats, intermittent productive cough, mild respiratory distress, subcutaneous emphysema |

Frontal cerebrum (NS) |

NS |

TMP/SMX (oral), meropenem (IV), linezolid (Oral) |

NA |

Clinical improvement after 12 mos |

| Pamukçuoglu et al., 20144 |

F |

61 |

Multiple myeloma, autologous stem cell transplant, ventricular assist device, thalidomide, CYBORD therapy |

Epileptic seizure |

Rt pst parietal cerebrum |

NS |

Meropenem (IV), amoxicillin/clavulanic acid |

Supratentorial craniotomy/evacuation |

Clinical improvement after 6 wks |

| Pamukçuoglu et al., 20144 |

F |

60 |

Multiple myeloma, breast cancer |

Cerebellar dysfunction |

Rt cerebellum, lt parietal cerebrum |

3 |

Imipenem/cilastatin, TMP/SMX |

Craniotomy (NS) |

Clinical improvement after 6 mos |

| Eshraghi et al., 201420 |

F |

55 |

Kidney transplant, azathioprine/methylprednisolone |

Febrile, diarrhea, vomiting |

Multiple |

NS |

Cotrimoxazole, imipenem, vancomycin, ceftriaxone |

NA |

Clinical improvement after 3 mos |

| Chavez et al., 201118 |

M |

58 |

No substance abuse, obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension |

Productive cough, dyspnea on exertion, rt pleuritic chest pain, 25-lb weight loss |

Cerebrum (NS), mesencephalon, cerebellum |

NS |

TMP/SMX (IV) |

NA |

Clinical improvement w/o recurrence at 30 mos |

| Elsayed et al., 200619 |

F |

69 |

Type 2 diabetes mellitus, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, hypogammaglobulinemia |

Malaise, rt flank pain, rt pleuritic chest discomfort, lt leg weakness, ataxic gait |

Cerebellum, cerebrum |

NS |

Empirical: meropenem (IV), TMP/SMX; culture-guided: TMP/SMX, imipenem, amikacin |

NA |

Clinical & radiographic improvement w/o complete resolution |

| Alp et al., 20061 |

M |

72 |

Recent respiratory infection (treated w/20 days of cefazolin), no underlying disease, previously healthy |

Headache, cough w/ sputum |

Multiple |

NS |

Empirical: imipenem (2 g/day), amikacin (1 g/day); culture-guided: ceftriaxone (4 g/day), amikacin (1 g/day) |

Craniotomy (NS) |

Clinical improvement after 12 mos |

| Barnaud et al., 20052 | F | 33 | HIV+ | Grand mal seizure | Rt frontal cerebrum, lt cerebrum (NS) (×3) | NS | Empirical: amoxicillin (IV), minocycline (oral); culture-guided: imipenem, amikacin, ciprofloxacin | NA | Clinical improvement after 3 mos |

CYBORD = cyclophosphamide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone; CKD = chronic kidney disease; HIV+ = human immunodeficiency virus positive; IV = intravenous; NA = not applicable; NS = not specified; pst = posterior; TMP/SMX = trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole.

Illustrative Case

Clinical Presentation

A 70-year-old male presented to the hospital with the chief complaint of dysarthria. His past medical history was significant for atrial fibrillation and type 2 diabetes mellitus. He had no history of malignancy, transplantation, or chronic infection that might confer immunosuppression. His neurological examination at presentation showed right hemiparesis and facial drop of central origin. Radiographic studies revealed a pontine lesion eccentric to the left with edema and restriction on diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI; Fig. 1A and B). These findings were interpreted as possible infection. The patient was started on empirical antibiotics despite noncontributory blood cultures, cerebrospinal fluid without evidence of meningitis, and negative encephalitis panels. An echocardiogram was performed and did not reveal evidence of a right-to-left shunt as a source for infectious emboli.

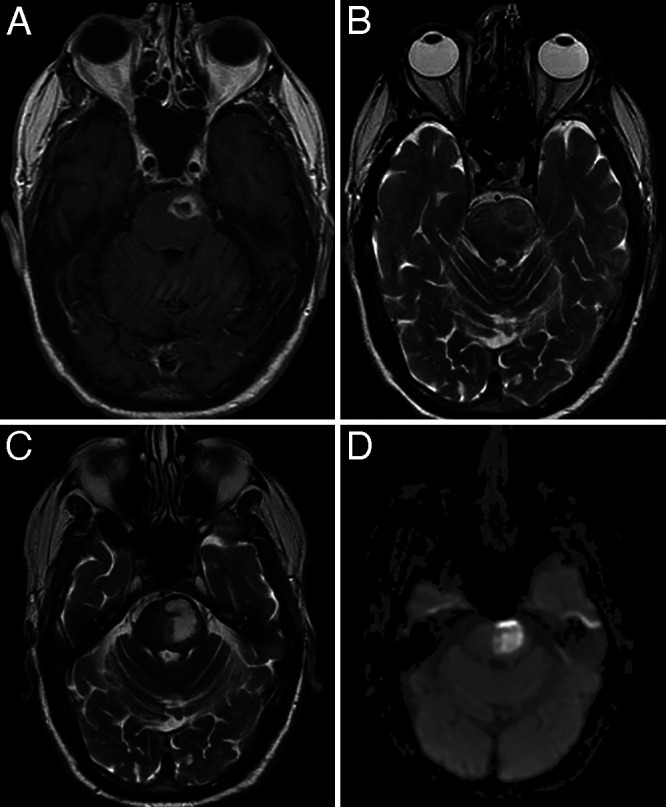

FIG. 1.

A: Axial T1-weighted MRI with gadolinium obtained at the initial presentation, showing a rim-enhancing lesion in the pons. B: Axial T2-weighted magnetic resonance image obtained at initial presentation, showing edema around the lesion. C: Axial T2-weighted magnetic resonance image taken 1 month after initial presentation, showing significant progression of the lesion. D: DWI showed restriction.

After several weeks, the mass enlarged and the patient’s hemiparesis worsened (Fig. 1C and D). Interestingly, the rim enhancement seen initially had diminished. On neurological examination, the lower half of his face on the right was almost immobile, and his speech was incomprehensible. Surgical evacuation was offered to the patient at presentation, but intervention was deemed too risky at that time by the patient, family, and his multidisciplinary care team. Given the clinical and radiographic progression with nonoperative treatment, however, surgery was reconsidered and deemed appropriate.

Surgical Management Strategy

Although stereotactic needle drainage was an option, this was dismissed for two reasons: (1) the risk of incomplete evacuation of the suspected abscess and (2) the possibility that this is a noninfectious lesion resistant to needle aspiration. For microsurgical extirpation, the well-described middle cerebellar peduncle approach was chosen because of recent experience with this operation for cavernous malformation of the brainstem.8,9

The patient was placed lateral with the left side up. After registering the neuronavigation and augmented reality (AR) systems, we were able to make a tailored C-shaped incision and retrosigmoid craniotomy that placed us directly above the target fissure. Under a navigation-tracked microscope integrated with AR (Video 1), the petrosal fissure of the cerebellum was opened until the middle cerebellar peduncle was exposed just superior to the entry zone of the facial and vestibulocochlear nerves. A small opening was made here and the dissection through the middle cerebellar peduncle gradually deepened, guided by navigation and AR. Here, the AR adjunct proved highly useful in localizing, and thus avoiding, these preoperatively contoured structures. The additional visual data provided not only facilitated the avoidance of these critical eloquent areas but also guided the angle of trajectory to the target in real time without potentially damaging deviations from the predetermined path (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

A: AR trajectory guiding the direction of dissection of the petrosal fissure. By aligning the superficial sphere with the deeper one, the surgeon can rely on the guidance to reach the middle cerebellar peduncle. B: View of the middle cerebellar peduncle. The AR (green) mesh is indicative of the extent of the brainstem lesion.

VIDEO 1. Clip demonstrating evacuation of the patient’s abscess via the middle cerebellar peduncle approach through the retrosigmoid craniotomy. Click here to view.

Once the target was reached, a thick, yellow fluid was encountered. Cultures were taken and the fluid was removed with suction. Exploration of the cavity showed an ill-defined wall with little demarcation from the brainstem. Once the cavity was fully explored and evacuated, the procedure was halted and closure began.

Outcome

Samples taken at surgery revealed fibrinopurulent necrotic debris with neutrophilic infiltration and granulation tissue formation on histopathological examination (Fig. 3). This was consistent with the diagnosis of abscess. The intraoperative cultures grew N. cyriacigeorgica. The patient consequently completed 6 weeks of ceftriaxone and remains on suppressive trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (Bactrim) months later. The magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) immediately after surgery showed a satisfactory evacuation of the abscess, and the patient’s neurological examination remained unchanged after surgery (Fig. 4). At 3 months, all but the Bactrim had been stopped, and the patient’s dysarthria and facial droop were vastly improved; his hemiparesis, however, had only slightly improved.

FIG. 3.

Histopathological image of the intraoperative sample. Fibrinopurulent necrotic debris with neutrophilic infiltration and granulation tissue formation are consistent with clinical diagnosis of abscess.

FIG. 4.

MR images obtained after surgery. A: Axial T2-weighted magnetic resonance image obtained right after surgery, showing no further evidence of the abscess. B: Axial T1 fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) image obtained at 3 months, with no recurrence.

Discussion

The incidence of solitary brainstem abscess is less than 4% of all posterior fossa abscesses, and less than 1% of all intracranial abscesses.10 Out of the very few solitary brainstem Nocardia abscesses in the literature, only two subjects survived (Table 1).11 We used the middle cerebellar peduncle approach and successfully evacuated an isolated Nocardia abscess of the pons.

Nocardia brain abscesses are rare but deadly, because they carry a greater than 50% mortality rate.6 They are most frequently encountered in immunocompromised hosts, entering the body through the lungs and spreading from the pulmonary source to the brain via the bloodstream. Isolated involvement of nonhemispheric regions has been reported. Cano Cevallos et al.12 studied a male patient with a necrotizing pulmonary nodule, who subsequently underwent an endonasal transsphenoidal biopsy for what proved to be a pituitary abscess caused by N. farcinica. Chow et al.11 studied a patient with solitary, yet multiloculated, abscess caused by the same species and unearthed four similar cases in the literature involving various species of Nocardia.13–15

Nocardia cyriacigeorgica, first identified by Yassin et al.,16 in 2001, is a rare cause of extrapulmonary nocardiosis.1 Since its initial sequencing, there have been several reported cases of N. cyriacigeorgica causing intracranial abscesses (Table 1).1–7,17–21 Notably, in contrast with most previously documented cases, our patient was previously healthy and active, spending much of his time doing yard work on his farm-like property in suburban Pennsylvania. Although his Nocardia exposure ostensibly occurred outdoors via the pulmonary route, his lungs were clear throughout his course of illness.

Observations

It is important to note that because of the restricted diffusion seen on the initial MRI, brainstem infection was suspected from the start. However, the patient, his family, and the multidisciplinary care team all agreed to a trial of medical therapy first. This has proven effective in prior cases in abscesses of the cerebrum, but often requires a very protracted course of antibiotics; notably, it has not been demonstrated in isolated and progressive brainstem lesions.11 Despite the surgical team’s willingness, an operation was initially deemed too risky. Nevertheless, clinical and radiographic progression during initial medical therapy mandated surgical intervention.

Regarding surgical alternatives, needle aspiration might have yielded identification of the pathogen, but had a high likelihood incomplete clearance of the infection. Other microsurgical approaches, such as the posterior midline approach, puts facial and eye movement at risk. The well-described posterolateral trajectory to the target (i.e., the middle cerebellar peduncle approach) is thought to mitigate these risks. It has most frequently been employed in resections of cavernous malformations, and there is ample data supporting its safety.8,9 The lack of neurological change in our patient after surgery is additive evidence for this.

Lessons

AR is additive to the transpetrosal fissure approach as described by Spetzler’s team.8 Although safe entry into the brainstem via this corridor is inarguably possible without this new technology, AR supplements the surgeon’s operative anatomy to confirm critical structures both for transgression and avoidance (Video 1). In our experience, we found that the usefulness of this intraoperative adjunct increases as the surgical field deepens into more eloquent parenchyma (Fig. 2). A case series is warranted to compare postoperative outcomes between AR and non-AR cases using this approach and those similar to it.

For brain abscesses in the hemispheres, the removal of the capsule, especially in the late-capsular phase of abscess evolution, is often taught as necessary for complete clearance of the infection. Given the location in the brainstem, this was never seriously considered for our patient, and in fact, a true capsule was not encountered in surgery. This is consistent with the diminution of rim enhancement on MRI within the month after presentation. Three months after surgery, the patient showed no signs of any infection, and some of his neurological symptoms have improved. The importance of a multidisciplinary team consisting of neurosurgeons as well as infectious disease and medical specialists cannot be overstated to both agree upon a unified approach to treatment and ensure complete resolution of the infection.

We report a case of N. cyriacigeorgica abscess in the pons of a previously healthy, immunocompetent patient. Refractory to medical management, the abscess was evacuated through a middle cerebellar peduncle approach with AR guidance, followed by antibiotics. Despite its rarity, Nocardia brain abscesses are often fatal. They need to be considered regardless of the immune status of the host and treated aggressively, including with microsurgical evacuation, when suspected.

Disclosures

Dr. Jean reported personal fees for consulting from Surgical Theater LLC outside the submitted work.

Author Contributions

Conception and design: Jean, Foster. Acquisition of data: all authors. Analysis and interpretation of data: Jean. Drafting the article: Jean, Mehta, Foster. Critically revising the article: all authors. Reviewed submitted version of manuscript: all authors. Approved the final version of the manuscript on behalf of all authors: Jean. Administrative/technical/material support: Jean, Mehta. Study supervision: Jean.

Supplemental Information

Video

Video 1. https://vimeo.com/799146633.

References

- 1. Alp E, Yildiz O, Aygen B, et al. Disseminated nocardiosis due to unusual species: two case reports. Scand J Infect Dis. 2006;38(6-7):545–548. doi: 10.1080/00365540500532860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Barnaud G, Deschamps C, Manceron V, et al. Brain abscess caused by Nocardia cyriacigeorgica in a patient with human immunodeficiency virus infection. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43(9):4895–4897. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.9.4895-4897.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Khorshidi M, Navid S, Azadi D, Shokri D, Shojaei H. A case report of brain abscess caused by Nocardia cyriacigeorgica in a diabetic patient. JMM Case Rep. 2018;5(9):e005133. doi: 10.1099/jmmcr.0.005133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Pamukçuoğlu M, Emmez H, Tunçcan OG, et al. Brain abscess caused by Nocardia cyriacigeorgica in two patients with multiple myeloma: novel agents, new spectrum of infections. Hematology. 2014;19(3):158–162. doi: 10.1179/1607845413Y.0000000108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Karan M, Vučković N, Vuleković P, Rotim A, Lasica N, Rasulić L. Nocardial brain abscess mimicking lung cancer metastasis in immunocompetent patient with pulmonary nocardiasis: a case report. Acta Clin Croat. 2019;58(3):540–545. doi: 10.20471/acc.2019.58.03.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gabay S, Yakubovsky M, Ben-Ami R, Grossman R. Nocardia cyriacigeorgica brain abscess in a patient on low dose steroids: a case report and review of the literature. BMC Infect Dis. 2022;22(1):635. doi: 10.1186/s12879-022-07612-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Garcia RR, Bhanot N, Min Z. A mimic’s imitator: a cavitary pneumonia in a myasthenic patient with history of tuberculosis. BMJ Case Rep. 2015;2015:bcr2015210264. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2015-210264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kalani MY, Yagmurlu K, Martirosyan NL, Spetzler RF. The Retrosigmoid Petrosal Fissure Transpeduncular Approach to Central Pontine Lesions. World Neurosurg. 2016;87:235–241. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2015.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tominaga S, Kugai M, Matsuda K, et al. Usefulness of the middle cerebellar peduncle approach for microsurgical resection of lateral pontine arteriovenous malformation. Neurosurg Focus Video. 2021;4(1):V11. doi: 10.3171/2020.10.FOCVID2063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Russell JA, Shaw MD. Chronic abscess of the brain stem. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1977;40(7):625–629. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.40.7.625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chow FC, Marson A, Liu C. Successful medical management of a Nocardia farcinica multiloculated pontine abscess. BMJ Case Rep. 2013;2013:bcr2013201308. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2013-201308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cano Cevallos EJ, Corsini Campioli C, Pritt BS, et al. Nocardia pituitary abscess in an immunocompetent host. IDCases. 2021;26:e01352. doi: 10.1016/j.idcr.2021.e01352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bertoldi RV, Sperling MR. Nocardia brain stem abscess: diagnosis and response to medical therapy. Bull Clin Neurosci. 1984;49:99–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Herkes GK, Fryer J, Rushworth R, Pritchard R, Wilson RM, Joffe R. Cerebral nocardiosis—clinical and pathological findings in three patients. Aust N Z J Med. 1989;19(5):475–478. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.1989.tb00311.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kepes JJ, Schoolman A. Post-traumatic abscess of the medulla oblongata containing Nocardia asteroides. J Neurosurg. 1965;22(5):511–514. doi: 10.3171/jns.1965.22.5.0511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Yassin AF, Rainey FA, Steiner U. Nocardia cyriacigeorgici sp. nov. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2001;51(Pt 4):1419–1423. doi: 10.1099/00207713-51-4-1419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Browne WD, Lieberson RE, Kabbesh MJ. Nocardia cyriacigeorgica brain and lung abscesses in 77-year-old man with diabetes. cureus. 2021;13(11):e19373. doi: 10.7759/cureus.19373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chavez TT, Fraser SL, Kassop D, Bowden LP, 3rd, Skidmore PJ. Disseminated nocardia cyriacigeorgica presenting as right lung abscess and skin nodule. Mil Med. 2011;176(5):586–588. doi: 10.7205/milmed-d-10-00346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Elsayed S, Kealey A, Coffin CS, Read R, Megran D, Zhang K. Nocardia cyriacigeorgica septicemia. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44(1):280–282. doi: 10.1128/JCM.44.1.280-282.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Eshraghi SS, Heidarzadeh S, Soodbakhsh A, et al. Pulmonary nocardiosis associated with cerebral abscess successfully treated by co-trimoxazole: a case report. Folia Microbiol (Praha) 2014;59(4):277–281. doi: 10.1007/s12223-013-0298-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Schlaberg R, Huard RC, Della-Latta P. Nocardia cyriacigeorgica, an emerging pathogen in the United States. J Clin Microbiol. 2008;46(1):265–273. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00937-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]