Abstract

Background

Smoking prevalence is higher among individuals with schizophrenia or depression, and previous work has suggested this relationship is causal. However, this may be due to dynastic effects, for example reflecting maternal smoking during pregnancy rather than a direct effect of smoking. We used a proxy gene-by-environment Mendelian randomization approach to investigate whether there is a causal effect of maternal heaviness of smoking during pregnancy on offspring mental health.

Methods

Analyses were performed in the UK Biobank cohort. Individuals with data on smoking status, maternal smoking during pregnancy, a diagnosis of schizophrenia or depression, and genetic data were included. We used participants’ genotype (rs16969968 in the CHRNA5 gene) as a proxy for their mothers’ genotype. Analyses were stratified on participants’ own smoking status in order to estimate the effect of maternal smoking heaviness during pregnancy independently of offspring smoking.

Results

The effect of maternal smoking on offspring schizophrenia was in opposing directions when stratifying on offspring smoking status. Among offspring of never smokers, each additional risk allele for maternal smoking heaviness appeared to have a protective effect [odds ratio (OR) = 0.77, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.62 to 0.95, P = 0.015], whereas among ever smokers the effect of maternal smoking was in the reverse direction (OR = 1.23, 95% CI 1.05 to 1.45, P = 0.011, Pinteraction <0.001). There was no clear evidence of an association between maternal smoking heaviness and offspring depression.

Conclusions

These findings do not provide clear evidence of an effect of maternal smoking during pregnancy on offspring schizophrenia or depression, which implies that any causal effect of smoking on schizophrenia or depression is direct.

Keywords: Mendelian randomization, smoking, depression, schizophrenia

Key Messages.

Smoking prevalence is higher among individuals with schizophrenia and depression; however, the role of dynastic effects (for example, reflecting the effects of their maternal smoking during pregnancy, rather than a direct effect of their own smoking) in this relationship is unclear.

Proxy gene-by-environment Mendelian randomization analyses can be used to investigate whether there is a causal role of maternal smoking during pregnancy on offspring mental health.

We found no clear evidence for a causal role of maternal smoking during pregnancy, suggesting that any causal role of smoking on schizophrenia and depression is direct.

Introduction

Smoking prevalence is higher among individuals with schizophrenia and depression compared with the general population.1–5 One argument for this association is the ‘self-medication’ hypothesis that suggests individuals may smoke in order to alleviate symptoms of mental illness or side effects of medication.6,7 However, other studies have suggested that the relationship may also run in the opposite direction, with smoking being a risk factor for subsequent mental illness.8–11

Previous work by Wootton and colleagues used a Mendelian randomization approach and found evidence of a causal effect of own smoking on both schizophrenia and depression.8 However, this study design did not exclude possible dynastic effects: this is where the expression of parental genetics via parental phenotype directly influences offspring phenotype.12 In this case, maternal rs16969968 genotype will influence maternal smoking heaviness, which could directly affect offspring mental health. If this pathway acts via a route that does not include offspring smoking, then this could result in a violation of one of the fundamental assumptions of Mendelian randomization.13 Under this assumption there should be no confounding of the relationship between the genetic variant and the outcome.

Supporting a possible dynastic effect, maternal smoking during pregnancy has been associated with adverse offspring outcomes, including depression and severe mental illness.9,14–17 Prenatal smoke exposure can be a potential risk to the developing fetus, as nicotine can cross the placenta and fetal-blood brain barrier. It has also been suggested that prenatal smoking can result in dysregulation of the fetal hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, which may be linked to the development of psychopathology.18 The causal effects of an individual’s own smoking compared with maternal smoking are difficult, but important, to separate.

However, evidence relating to the effects of maternal smoking during pregnancy on offspring mental health is mixed.14–16,19–21 The majority of this evidence to date uses observational data, from which it is difficult to infer causality with confidence.9 A negative control study carried out in the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (ALSPAC) did find some evidence of a causal effect of in utero tobacco exposure on psychotic experiences in adolescence.20 Conversely, a cross-cohort and negative control study of maternal smoking in pregnancy and offspring depression suggested that observed associations could reflect residual confounding relating to parental characteristics.21

In this study, we used data from the UK Biobank study and a proxy gene-by-environment (GxE) Mendelian randomization approach to investigate whether there is evidence for a causal effect of maternal heaviness of smoking during pregnancy on offspring schizophrenia or depression.22 We used genetic data from participants at the rs16969968 locus in the CHRNA5 gene as a proxy for maternal genotype, which was unavailable in the study. The use of a genetic variant as a proxy for maternal smoking means that our analysis should be less subject to the problems of confounding and reverse causation that conventional observational studies are often subject to.13,23,24 This approach also enables us to investigate the effects of maternal smoking during pregnancy on offspring outcomes even when maternal genetic information is not available. This proxy GxE method has previously been validated by replicating the effect of maternal smoking during pregnancy on birthweight.22

Methods and measures

Sample

The UK Biobank Study is a large population cohort consisting of around 500 000 individuals recruited in the UK between 2006 and 2010. Eligible individuals were aged between 40 and 69 years at time of recruitment and living within 25 miles of an assessment centre (22 assessment centres were based across England, Wales and Scotland). Approximately 9.2 million individuals were invited to take part, with around 5.5% of these participating in the baseline assessment.25 Informed consent was obtained from study participants by UK Biobank. UK Biobank received ethics approval from the Research Ethics Committee (REC reference for UK Biobank is 11/NW/0382).

Smoking status

Maternal smoking during pregnancy was reported by UK Biobank participants (the offspring) in response to the question ‘Did your mother smoke regularly around the time when you were born?’ (variable: 1787). Offspring smoking status was categorized as never or ever (former or current) smokers according to participants’ self-reported smoking status at recruitment (variable: 20116).

Offspring schizophrenia diagnosis

Diagnoses of schizophrenia were derived using a combination of approaches including the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) diagnoses (variable 41202 and 41204, category F20) and date of diagnosis (variable: 130874), identified via a combination of sources including death registers, primary care sources, hospital admissions data and self-report. We also included self-reported diagnoses using the non-cancer illness item (variable: 20002, category for schizophrenia: 1289). Responses to this item were derived from the verbal interview conducted at the initial assessment. In total, we identified 528 (0.18%) individuals with a diagnosis of schizophrenia based on the date of diagnosis item (n = 526), ICD-10 codes (n = 336) and the non-cancer illness item (n = 276). All other participants in the analysis sample were categorized as controls (n = 288 165).

Offspring depression diagnosis

We used two definitions of depressive disorder. The first was a stricter definition of depression as measured by responses to the online mental health questionnaire (MHQ; variable: 20126), referred to from now on as major depressive disorder (MDD). The second was less specific about the type of depression and was measured by responses to both the self-reported diagnoses using the non-cancer illness item (variable: 20002, category for depression: 1286) and the ICD-10 diagnoses (variable: 41202 and 41204, categories: F32 or F33), referred to from here on as depression. A total of 18 704 individuals reported a diagnosis of MDD using the MHQ (27.1%) and 20 901 (7.24%) individuals reported a diagnosis of depression based on the non-cancer illness item (n = 16 318) and the ICD-10 item (n = 8125).

Genetic instrument for maternal smoking

Maternal genotype is unavailable in UK Biobank, so participants’ genotype was used as a proxy. There are several potential variants in the CHRNA5-A3-B4 gene cluster that could have been used as a proxy for smoking heaviness (e.g. rs16969968, rs1051730, rs2036527, rs17486278, rs17487223), and these are all highly correlated.26 A recent genome-wide association study of tobacco use identified variants within the CHRNA5-A3-B4 gene cluster that are associated with smoking initiation.27 However, these variants are not correlated with the rs16969968 single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP), and this gene cluster appears to have distinct influences on smoking initiation and heaviness.

We chose to use the rs16969968 variant in the CHRNA5-A3-B4 gene cluster as a genetic instrument for smoking heaviness. This variant is a missense mutation in the α-5 subunit and appears to have functional significance.26 This variant is located within the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor gene cluster and causes an amino acid change that is associated with a reduced response to nicotine.26,28 The rs16969968 SNP is therefore likely to be the functional variant associated with smoking heaviness. Each additional copy of the A allele is associated with smoking one additional cigarette per day on average.29 Analyses were restricted to individuals of White British descent to avoid introducing bias due to population stratification.30

Statistical analysis

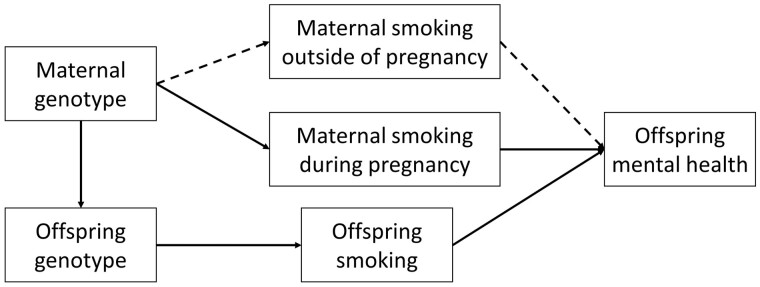

We used a proxy GxE Mendelian randomization approach as described in Yang and colleagues,22 to test for causal effects of maternal smoking on offspring mental health, where offspring genotype is used as a proxy for maternal genotype. Logistic regression analyses were performed to investigate the association between rs16969968 and diagnosis of schizophrenia or depression. It is possible that offspring genotype could influence their mental health via both maternal and their own smoking heaviness. Analyses were therefore stratified on participants’ own smoking status and adjusted for the top 10 principal components of ancestry, birth year and gender, in order to estimate the effect of maternal smoking heaviness during pregnancy independently of offspring smoking (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Proxy gene-by-environment Mendelian randomization conceptual framework—offspring genotype is used as a proxy for maternal genotype and analyses are stratified on maternal substance use during pregnancy. Maternal substance use outside of pregnancy could influence offspring mental health via alternative pathways (e.g. oocyte quality or passive smoking in the case of smoking heaviness—shown by dashed lines). Offspring substance use may also influence offspring mental health, and analyses are therefore also stratified on offspring substance use. Adapted from Yang Q, Millard LAC and Davey Smith G22

As a sensitivity analysis, we re-ran the analysis excluding individuals who were heterozygous at rs16969968, to ensure we knew which allele was received from the mother. Diagnoses of schizophrenia are much lower in UK Biobank (0.19%) than in the general population (lifetime prevalence estimates ∼1%),31 which could mean that these findings are at risk of distortion by collider bias.32 Depression is under less selection in UK Biobank, and we used two distinct phenotype definitions, which should minimize the risk of collider bias. In order to investigate the extent of collider bias due to selection of the offspring schizophrenia phenotype, we explored whether the association between diagnosis and known risk factors for schizophrenia was as expected in our sample. We expected an inverse association between both birthweight and education with schizophrenia diagnosis, and a positive association between genetic liability to schizophrenia and schizophrenia diagnosis.33–35

Results

There were 288 693 individuals in UK Biobank with relevant data on smoking status, maternal smoking during pregnancy, self-reported diagnosis of schizophrenia or depression and rs16969968 genotype. When using the MDD diagnosis from the touchscreen questionnaire, 68 983 participants had relevant data for the analysis.

Smoking status

We found an association between each additional smoking heaviness-increasing allele and increased odds of maternal smoking during pregnancy [odds ratio (OR) = 1.02, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.01 to 1.03, P = 0.002], and, as also reported by Yang and colleagues,22 lower odds of participants being an ever smoker (OR = 0.98, 95% CI 0.97 to 0.99, P = 0.001), and lower birthweight of the participant [beta (β) = -0.01,95% CI -0.01 to -0.002]. These associations confirm the validity of the genetic instrument as a proxy for smoking status.

Offspring schizophrenia

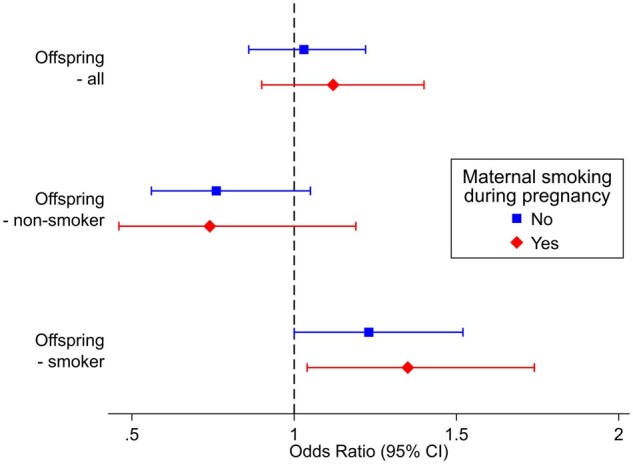

We found some evidence of an association between rs16969968 genotype and schizophrenia when stratifying on offspring smoking status (Pinteraction = <0.001; Table 1). Among offspring who were never smokers, each additional risk allele acting as a proxy for maternal smoking heaviness appeared to have a protective effect (OR = 0.77, 95% CI 0.62 to 0.95, P = 0.02), whereas among offspring who ever smoked, each additional smoking heaviness allele was associated with an increased odds of schizophrenia diagnosis (OR = 1.23, 95% CI 1.05 to 1.45, P = 0.01). However, this effect was consistent regardless of maternal smoking status during pregnancy and there was no clear evidence of an interaction by maternal smoking status (Pinteraction = 0.58–0.93; Table 2, Figure 2). This implies that any effects of smoking on schizophrenia risk is not due to maternal smoking in pregnancy.

Table 1.

Association between rs16969968 genotype and offspring mental health when stratified by offspring smoking only, analyses not restricted on maternal smoking status

| Outcome | Offspring smoking status | OR | 95% CI | P-value | Interaction P-value | N |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Schizophrenia | No | 0.77 | 0.62 to 0.95 | 0.015 | <0.001 | 161 372 |

| Yes | 1.23 | 1.05 to 1.45 | 0.011 | 127 321 | ||

| MDD | No | 1.02 | 0.99 to 1.06 | 0.192 | 0.812 | 38 911 |

| Yes | 1.02 | 0.98 to 1.06 | 0.377 | 30 072 | ||

| Depression | No | 1.01 | 0.98 to 1.04 | 0.727 | 0.553 | 161 372 |

| Yes | 1.02 | 0.99 to 1.05 | 0.237 | 127 321 |

MDD, major depressive disorder; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Table 2.

Proxy GxE analysis of maternal smoking heaviness during pregnancy on offspring mental health, adjusted for year of birth, offspring gender, top 10 principal components of ancestry

| Outcome | Offspring smoking status | Maternal smoking around birth | OR | 95% CI | P-value | Interaction P-value | N |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Schizophrenia | All | No | 1.02 | 0.87, 1.20 | 0.796 | 0.926 | 200 541 |

| Yes | 1.03 | 0.83, 1.28 | 0.784 | 88 152 | |||

| No | No | 0.80 | 0.62, 1.03 | 0.082 | 0.578 | 113 164 | |

| Yes | 0.70 | 0.47, 1.03 | 0.072 | 48 208 | |||

| Yes | No | 1.21 | 0.99, 1.49 | 0.062 | 0.795 | 87 377 | |

| Yes | 1.27 | 0.97, 1.67 | 0.086 | 39 944 | |||

| MDD | All | No | 1.02 | 0.98, 1.05 | 0.346 | 0.694 | 48 272 |

| Yes | 1.03 | 0.98, 1.07 | 0.263 | 20 711 | |||

| No | No | 1.03 | 0.98, 1.07 | 0.218 | 0.654 | 27 534 | |

| Yes | 1.01 | 0.95, 1.08 | 0.747 | 11 377 | |||

| Yes | No | 1.00 | 0.96, 1.05 | 0.967 | 0.218 | 20 738 | |

| Yes | 1.05 | 0.99, 1.13 | 0.128 | 9334 | |||

| Depression | All | No | 1.02 | 0.99, 1.04 | 0.253 | 0.446 | 200 541 |

| Yes | 1.00 | 0.96, 1.03 | 0.930 | 88 152 | |||

| No | No | 1.01 | 0.97, 1.05 | 0.626 | 0.253 | 113 164 | |

| Yes | 0.99 | 0.94, 1.05 | 0.790 | 48 208 | |||

| Yes | No | 1.02 | 0.99, 1.06 | 0.225 | 0.638 | 87 377 | |

| Yes | 1.01 | 0.96, 1.06 | 0.769 | 39 944 |

MDD, major depressive disorder; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval GxE, gene-by-environment.

Figure 2.

The association of participants’ rs16969968 genotype with diagnosis of schizophrenia stratified by maternal smoking status during pregnancy and their own smoking status

Sensitivity analyses restricting to individuals who were homozygous at rs16969968 were consistent and found no strong evidence of an effect of maternal smoking heaviness during pregnancy on offspring schizophrenia (Table 3). The association between established risk factors and offspring schizophrenia was as expected. Increased years of education were associated with decreased odds of schizophrenia diagnosis (OR = 0.85, 95% CI 0.82 to 0.89, P <0.001), and greater genetic liability for schizophrenia was associated with increased odds of diagnosis (OR = 1.53, 95% CI 1.40 to 1.66, P <0.001) (Table 4). Although there was no strong evidence of an association between birthweight and schizophrenia diagnosis, the effect estimate was in the hypothesized direction (OR = 0.92 per kg birthweight, 95% CI 0.76 to 1.11, P = 0.37). We also examined the association between the schizophrenia polygenic risk score (PRS) and years of education. Among controls we found some evidence of a small positive association (β = 0.01 per additional standard deviation in PRS, 95% CI 0.00 to 0.02, P = 0.05). In the whole sample, evidence for a positive association was weaker and, when restricting to cases, the effect estimate suggested a negative association between the schizophrenia PRS and years of education (β = -0.11 per additional standard deviation in PRS, 95% CI -0.33 to 0.10, P = 0.29) (Table 4). When restricting to cases, power was low and there was little evidence of an association.

Table 3.

Sensitivity analysis restricting to rs16969968 homozygous individuals only. Proxy GxE analysis of maternal smoking heaviness during pregnancy on offspring mental health, adjusted for year of birth, offspring gender, top 10 principal components of ancestry

| Outcome | Offspring smoking status | Maternal smoking around birth | OR | 95% CI | P-value | Interaction P-value | N |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Schizophrenia | All | No | 1.03 | 0.86, 1.22 | 0.748 | 0.547 | 111 954 |

| Yes | 1.12 | 0.90, 1.40 | 0.318 | 48 812 | |||

| No | No | 0.76 | 0.56, 1.05 | 0.096 | 0.910 | 63 094 | |

| Yes | 0.74 | 0.46, 1.19 | 0.212 | 26 560 | |||

| Yes | No | 1.23 | 1.00, 1.52 | 0.052 | 0.587 | 48 860 | |

| Yes | 1.35 | 1.04, 1.74 | 0.024 | 22 252 | |||

| MDD | All | No | 1.02 | 0.99, 1.06 | 0.175 | 0.555 | 27 098 |

| Yes | 1.00 | 0.95, 1.06 | 0.852 | 11 504 | |||

| No | No | 1.04 | 1.00, 1.09 | 0.076 | 0.247 | 15 435 | |

| Yes | 0.99 | 0.93, 1.06 | 0.840 | 6308 | |||

| Yes | No | 1.00 | 0.95, 1.06 | 0.938 | 0.571 | 11 663 | |

| Yes | 1.03 | 0.95, 1.11 | 0.466 | 5 196 | |||

| Depression | All | No | 1.02 | 0.99, 1.05 | 0.271 | 0.327 | 111 954 |

| Yes | 0.99 | 0.95, 1.03 | 0.690 | 48 812 | |||

| No | No | 1.02 | 0.98, 1.06 | 0.332 | 0.211 | 63 094 | |

| Yes | 0.98 | 0.92, 1.04 | 0.430 | 26 560 | |||

| Yes | No | 1.01 | 0.97, 1.06 | 0.522 | 0.937 | 48 860 | |

| Yes | 1.01 | 0.96, 1.07 | 0.719 | 22 252 |

GxE, gene-by-environment; MDD, major depressive disorder; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Table 4.

Association between established risk factors for schizophrenia and offspring schizophrenia in UK Biobank

| Exposure | Outcome | OR | 95% CI | P-value | N |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Education (years of schooling) | Schizophrenia diagnosis | 0.85 | 0.82 to 0.89 | <0.001 | 286 262 |

| Genetic liability for schizophrenia | Schizophrenia diagnosis | 1.53 | 1.40 to 1.66 | <0.001 | 288 693 |

| Birthweight (kg) | Schizophrenia diagnosis | 0.92 | 0.76 to 1.11 | 0.374 | 173 402 |

|

| |||||

| β | 95% CI | P-value | N | ||

|

| |||||

| Genetic liability for schizophrenia | Education (years of schooling): whole cohort | 0.01 | −0.001 to 0.016 | 0.072 | 286 262 |

| Genetic liability for schizophrenia | Education (years of schooling): among controls | 0.009 | 0.0002 to 0.017 | 0.046 | 285 740 |

| Genetic liability for schizophrenia | Educational (years of schooling): among cases | −0.11 | −0.33 to 0.10 | 0.290 | 522 |

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; β, beta.

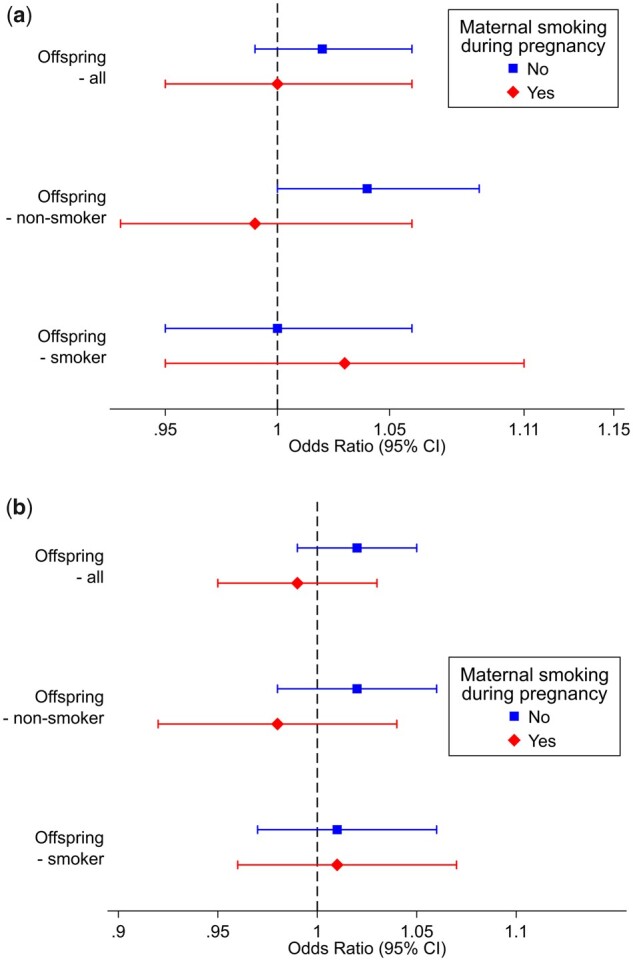

Offspring depression

We found no clear evidence of an association between rs16969968 genotype and either MDD or depression when stratifying on offspring smoking status, and there was no robust evidence of an interaction (Table 1). Effect estimates remained consistent when stratifying on maternal smoking status during pregnancy and we found no strong evidence of an association for either MDD or depression (Table 2, Figure 3). Sensitivity analyses restricting to homozygous individuals were consistent and identified no strong evidence of an association (Table 3).

Figure 3.

The association of participants’ rs16969968 with diagnosis of a) depression according to the mental health touchscreen questionnaire and b) depression according to the self-reported non-cancer illness code and ICD-10 codes. Both analyses were stratified by maternal smoking status during pregnancy and participants’ own smoking status. *ICD-10: International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Edition

Discussion

In this study, we extended previous work by Wootton and colleagues that found a causal effect of own smoking on mental health, and applied methods developed by Yang and colleagues22 to investigate whether this was partially explained by causal effects of maternal smoking heaviness in pregnancy. Although we found evidence of an effect of offspring smoking heaviness on schizophrenia, these effects were consistent when stratifying by maternal smoking status, and we found no strong evidence of an effect of maternal smoking heaviness on offspring depression. Overall, we found little support for a causal effect of maternal smoking heaviness during pregnancy on offspring schizophrenia or depression or of own smoking on depression, but some evidence of a causal effect of own smoking status on schizophrenia diagnosis.

A recent review, combining 12 observational studies, suggests that both own smoking and prenatal tobacco smoke exposure may be independent risk factors for schizophrenia, with risk of schizophrenia increased by 29% after exposure to prenatal smoke.9 However, this review did not include studies such as sibling comparison designs, and as a result may be subject to familial confounding as described by Quinn and colleagues.36 Rather than representing a true causal effect, it is possible that the observed association between maternal smoking during pregnancy and offspring diagnosis of schizophrenia could be due to passive gene-environment correlation or other shared family factors.36 Recent sibling comparison studies that account for this familial confounding have found weaker effects of maternal smoking during pregnancy, which is in line with our findings.14,19

The association between rs16969968 genotype and schizophrenia when restricting to participants (offspring) who smoke is indicative of a causal role of smoking heaviness on schizophrenia. This is in line with recent findings reported by Wootton and colleagues,8 who used a two-sample Mendelian randomization approach and found strong evidence for a causal effect of both smoking initiation and lifetime smoking on schizophrenia. However, we also observe an inverse association between rs16969968 genotype and own smoking status. This is unexpected and could be due to selection bias, which could have implications for our interpretation of the association between rs16969968 genotype and schizophrenia. We know that there is evidence of selection based on smoking status, with the proportion of current smokers in UK Biobank lower than in the general population of the UK.37 Poor mental health is also linked with lower participation in cohort studies,32,38,39 with diagnoses of schizophrenia in the UK Biobank study (0.19%) being much lower than in the general population (∼1%).31 The increased participation of non-smokers and lower participation of individuals with schizophrenia could therefore induce a negative association between rs16969968 genotype and schizophrenia among non-smokers. Therefore, the association we observe between rs16969968 genotype and schizophrenia diagnosis may be a result of collider bias due to selection on study participation.

Depression is under less selection in UK Biobank and we did not observe an association between rs16969968 genotype and offspring depression when using either definition of depression. An alternative suggestion is that this negative association between rs16969968 genotype and schizophrenia among non-smokers is due to some underlying biology. Yang and colleagues22 found a similar effect on birthweight when stratifying on maternal and own smoking status and suggest potential pathways, including that mothers exposed as fetuses to intrauterine smoking may be less able to constrain the paternal impact. However, we did not have the data to investigate the effects on mental health across three generations.

Lifetime prevalence of schizophrenia in the general population is around 1%,31 but in the UK Biobank we observed a prevalence of 0.2%. In order to investigate the impact of collider bias on our results, we performed several sensitivity analyses. We first estimated the association between known risk factors for schizophrenia (educational attainment, schizophrenia polygenic scores, birthweight) and offspring diagnosis, all of which were associated in the direction we would expect and effect estimates were consistent with those identified in previous studies.40,41 When stratifying on diagnosis, the differences in association shown between genetic liability for schizophrenia and educational attainment between cases and controls fit with theories of stabilizing selection or cliff-edge fitness for schizophrenia persistence.42,43 Among those without a diagnosis there is a positive association between genetic liability for schizophrenia and educational attainment, whereas among those reaching the threshold for a diagnosis, the direction of effect appears to be in the opposite direction. We also looked at the interaction between maternal smoking heaviness and schizophrenia polygenic score and found no strong evidence of an association. Depression is under less selection in the UK Biobank cohort and should therefore be at less risk of collider bias, and analyses using offspring depression as the outcome also found no strong evidence of an association between maternal smoking during pregnancy and offspring mental health. This suggests that for both schizophrenia and depression, the observed association between maternal smoking during pregnancy and offspring outcomes may be due to residual confounding. This is consistent with findings by Taylor and colleagues who used a cross-cohort and negative control analysis to investigate the influence of maternal smoking during pregnancy on offspring depression.21

This work is subject to limitations. First, our analysis used offspring genotype at rs16969968 as a proxy for maternal genotype. Offspring genotype contains information inherited from fathers, reducing our power to detect interactions between the categories of maternal smoking status. As a sensitivity analysis, we excluded heterozygous individuals to ensure that the smoking heaviness-increasing allele was inherited from the mothers. The results remained consistent, with little evidence of an effect of maternal smoking heaviness.

Second, rs16969968 is a proxy for smoking heaviness across the lifetime, and its effects are not restricted to during pregnancy. It is possible that any association could act via other pathways, such as passive gene-environment correlation or other familial confounding factors.

Third, our analysis stratifies on both mother and offspring smoking status and as a result may be subject to collider bias.37 Previous simulations suggest this should have a minimal impact on our findings, although it is likely that the extent of collider bias is larger with respect to how schizophrenia and its underlying genetic liability influence entering the study than in these previous examples.22,44

Fourth, offspring schizophrenia is under-represented in UK Biobank, which could mean our results are subject to collider bias. However, we performed several sensitivity analyses to check the association of this phenotype with established risk factors and they behaved as expected. We also included depression as an outcome, which is under less selection in the sample, and our results were similar. The association between rs16969968 and schizophrenia in this study could be due to collider bias; however it is also consistent with findings by Wootton and colleagues, who found a strong association between lifetime smoking and schizophrenia diagnosis.

Fifth, our exposure and outcome measures may be misclassified. We used offspring smoking status as reported at recruitment; however, smoking status is not constant across the life course and it may have differed at critical developmental periods prior to illness onset. Maternal smoking during pregnancy was derived using offspring responses to a question that asked about smoking around the time of birth, rather than during pregnancy. There is evidence to suggest that offspring reports of maternal smoking during pregnancy have reasonable validity.45 Although the question relates to smoking around the time of birth, at the time of these pregnancies there was little guidance around the use of tobacco during pregnancy. The first report Smoking and Health was published by the Royal College of Physicians (RCP) in 1962,46 whereas 90% of our sample were born in (or prior to) 1963. Therefore, although asking about smoking during the time of birth may have resulted in increased misclassification of smoking status during pregnancy, the risk is likely to be minimal in this cohort. It is also well documented that maternal smoking during pregnancy is associated with lower offspring birthweight, including within UK Biobank.47 As shown by Yang and colleagues,22 the rs16969968 SNP is associated with lower birthweight among offspring of mothers reporting smoking during pregnancy. It therefore seems likely that misclassification was minimal and that the variant reflects maternal smoking heaviness during pregnancy. Schizophrenia diagnosis and one of the depression definitions were based on positive responses to two items, so it is possible that some individuals who did not respond to these items were incorrectly classified as controls. This misclassification could lead us to underestimate a true causal effect, should one exist.

Sixth, data on smoking initiation, schizophrenia and depression were collected retrospectively and we did not have ages at diagnosis and initiation for the majority of our sample. Where these data were available, 92% of individuals reported smoking prior to receiving a diagnosis of schizophrenia. Additionally, given that 90% of lifetime smoking is initiated between ages of 10 and 20,48 whereas the median age of onset for depression and schizophrenia occurs during early to mid-adulthood,49 it seems likely that for the majority of participants, smoking initiation would precede any diagnosis.

Conclusion

Our findings are in line with those reported by Wootton and colleagues,8 which supported a causal effect of own cigarette smoking on schizophrenia diagnosis, although unlike Wootton and colleagues, we found little evidence of an association between own smoking and depression. We also found little evidence to suggest a causal effect of maternal heaviness of smoking during pregnancy on either offspring schizophrenia or depression.

Ethics approval

UK Biobank is approved by the National Health Service National Research Ethics Service (ref. 11/NW/0382; UK Biobank application number 9142).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Dr Hannah Jones and Dr Zoe Reed for their helpful suggestions on the analysis. This research has been conducted using the UK Biobank Resource under Application Number 9142. This work uses data provided by patients and collected by the NHS as part of their care and support. Copyright © 2023, NHS England. Re-used with the permission of the NHS England and UK Biobank. All rights reserved. This research used data assets made available by National Safe Haven as part of the Data and Connectivity National Core Study, led by Health Data Research UK in partnership with the Office for National Statistics and funded by UK Research and Innovation (research which commenced between 1st October 2020 – 31st March 2021 grant ref MC_PC_20029; 1st April 2021 – 30th September 2022 grant ref MC_PC_20058).

Contributor Information

Hannah M Sallis, Centre for Academic Mental Health, Population Health Sciences, Bristol Medical School, University of Bristol, Bristol, UK; MRC Integrative Epidemiology Unit (IEU) at the University of Bristol, Bristol, UK.

Robyn E Wootton, MRC Integrative Epidemiology Unit (IEU) at the University of Bristol, Bristol, UK; Nic Waals Institute, Lovisenberg Diaconal Hospital, Oslo, Norway.

George Davey Smith, MRC Integrative Epidemiology Unit (IEU) at the University of Bristol, Bristol, UK.

Marcus R Munafò, MRC Integrative Epidemiology Unit (IEU) at the University of Bristol, Bristol, UK; School of Psychological Science, University of Bristol, Bristol, UK; NIHR Biomedical Research Centre, University Hospitals Bristol NHS Foundation Trust and University of Bristol, Bristol, UK.

Data availability

The UK Biobank dataset used to conduct the research in this paper is available via application directly to the UK Biobank. Applications are assessed for meeting the required criteria for access, including legal and ethics standards. More information regarding data access can be found at [https://www.ukbiobank.ac.uk/enable-your-research].

Author contributions

G.D.S. and M.R.M. initiated the study concept. H.M.S. performed the statistical analysis and drafted the initial version of the manuscript. All authors were involved in the interpretation of the data and contributed to and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

H.M.S., G.D.S. and M.R.M. are all members of the Medical Research Council Integrative Epidemiology Unit at the University of Bristol (MC_UU_00011/1, MC_UU_00011/7). H.M.S. is also supported by the European Research Council (grant ref.: 758813 MHINT). R.E.W. is supported by a postdoctoral fellowship from the South-Eastern Norway Regional Health Authority (2020024). This work is supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Biomedical Research Centre at University Hospitals Bristol NHS Foundation Trust and the University of Bristol. The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Conflict of interest

H.M.S., R.E.W. and M.R.M. have provided consultancy to Action on Smoking and Health UK on the role of smoking in mental health.

References

- 1. Dickerson F, Schroeder J, Katsafanas E. et al. Cigarette smoking by patients with serious mental illness, 1999–2016: an increasing disparity. Psychiatr Serv 2018;69:147–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Castle D, Baker AL, Bonevski B.. Editorial: smoking and schizophrenia. Front Psychiatry 2019;10:738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Royal College of Physicians. Smoking and Mental Health. 2013. https://www.rcplondon.ac.uk/projects/outputs/smoking-and-mental-health (2 February 2023, date last accessed)

- 4. Fluharty M, Taylor AE, Grabski M, Munafò MR.. The association of cigarette smoking with depression and anxiety: a systematic review. Nicotine Tob Res 2017;19:3–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tjora T, Hetland J, Aarø LE, Wold B, Wiium N, Øverland S.. The association between smoking and depression from adolescence to adulthood. Addiction 2014;109:1022–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Khantzian EJ. The self-medication hypothesis of addictive disorders: focus on heroin and cocaine dependence. Am J Psychiatry 1985;142:1259–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Manzella F, Maloney SE, Taylor GT.. Smoking in schizophrenic patients: a critique of the self-medication hypothesis. World J Psychiatry 2015;5:35–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wootton RE, Richmond RC, Stuijfzand BG. et al. Evidence for causal effects of lifetime smoking on risk for depression and schizophrenia: a Mendelian randomization study. Psychol Med 2020;50:2435–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hunter A, Murray R, Asher L, Leonardi-Bee J.. The effects of tobacco smoking, and prenatal tobacco smoke exposure, on risk of schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nicotine Tob Res 2020;22:3–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Scott JG, Matuschka L, Niemelä S, Miettunen J, Emmerson B, Mustonen A.. Evidence of a causal relationship between smoking tobacco and schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Front Psych 2018;9:607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kendler KS, Lönn SL, Sundquist J, Sundquist K.. Smoking and schizophrenia in population cohorts of Swedish women and men: a prospective co-relative control study. Am J Psychiatry 2015;172:1092–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Brumpton B, Sanderson E, Heilbron K. et al. ; 23andMe Research Team. Avoiding dynastic, assortative mating, and population stratification biases in Mendelian randomization through within-family analyses. Nat Commun 2020;11:3519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sanderson E, Glymour MM, Holmes MV. et al. Mendelian randomization. Nat Rev Methods Primers 2022;2:6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Quinn PD, Rickert ME, Weibull CE. et al. Association between maternal smoking during pregnancy and severe mental illness in offspring. JAMA Psychiatry 2017;74:589–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Niemelä S, Sourander A, Surcel HM. et al. Prenatal nicotine exposure and risk of schizophrenia among offspring in a national birth cohort. Am J Psychiatry 2016;173:799–806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Moylan S, Gustavson K, Øverland S. et al. The impact of maternal smoking during pregnancy on depressive and anxiety behaviors in children: the Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort Study. BMC Med 2015;13:24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Menezes AMB, Murray J, László M. et al. Happiness and depression in adolescence after maternal smoking during pregnancy: birth cohort study. PLoS One 2013;8:e80370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Huizink AC, Mulder EJH.. Maternal smoking, drinking or cannabis use during pregnancy and neurobehavioral and cognitive functioning in human offspring. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2006;30:24–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Meier SM, Mors O, Parner E.. Familial confounding of the association between maternal smoking during pregnancy and schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 2017;174:187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Zammit S, Thomas K, Thompson A. et al. Maternal tobacco, cannabis and alcohol use during pregnancy and risk of adolescent psychotic symptoms in offspring. Br J Psychiatry 2009;195:294–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Taylor AE, Carslake D, de Mola CL. et al. Maternal smoking in pregnancy and offspring depression: a cross cohort and negative control study. Sci Rep 2017;7:12579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Yang Q, Millard LAC, Davey Smith G.. Proxy gene-by-environment Mendelian randomization study confirms a causal effect of maternal smoking on offspring birthweight, but little evidence of long-term influences on offspring health. Int J Epidemiol 2020;49:1207–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Davey Smith G, Hemani G.. Mendelian randomization: genetic anchors for causal inference in epidemiological studies. Hum Mol Genet 2014;23:R89–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Davey Smith G, Ebrahim S. ‘Mendelian randomization’: can genetic epidemiology contribute to understanding environmental determinants of disease? Int J Epidemiol 2003;32:1–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Fry A, Littlejohns TJ, Sudlow C. et al. Comparison of sociodemographic and health-related characteristics of UK biobank participants with those of the general population. Am J Epidemiol 2017;186:1026–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bierut LJ, Stitzel JA, Wang JC. et al. Variants in nicotinic receptors and risk for nicotine dependence. Am J Psychiatry 2008;165:1163–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Saunders GRB, Wang X, Chen F. et al. ; Biobank Japan Project. Genetic diversity fuels gene discovery for tobacco and alcohol use. Nature 2022;612:720–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Munafò MR, Timofeeva MN, Morris RW. et al. ; EPIC Study Group. Association between genetic variants on chromosome 15q25 locus and objective measures of tobacco exposure. J Natl Cancer Inst 2012;104:740–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ware JJ, van den Bree MBM, Munafò MR.. Association of the CHRNA5-A3-B4 gene cluster with heaviness of smoking: a meta-analysis. Nicotine Tob Res 2011;13:1167–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mitchell R, Hemani G, Dudding T, Corbin L, Harrison S, Paternoster L.. UK Biobank Genetic Data: MRC-IEU Quality Control. Version 2. 2019. 10.5523/bris.1ovaau5sxunp2cv8rcy88688v (2 February 2023, date last accessed) [DOI]

- 31. Stilo SA, Murray RM.. The epidemology of schizophrenia: replacing dogma with knowledge. Dialogues Clin Neurosci 2010;12:305–15. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2010.12.3/sstilo [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Martin J, Tilling K, Hubbard L. et al. Association of genetic risk for schizophrenia with nonparticipation over time in a population-based cohort study. Am J Epidemiol 2016;183:1149–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Dickson H, Hedges EP, Ma SY. et al. Academic achievement and schizophrenia: a systematic meta-analysis. Psychol Med 2020;50:1949–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Abel KM, Wicks S, Susser ES. et al. Birth weight, schizophrenia, and adult mental disorder: is risk confined to the smallest babies? Arch Gen Psychiatry 2010;67:923–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Vassos E, Di Forti M, Coleman J. et al. An examination of polygenic score risk prediction in individuals with first-episode psychosis. Biol Psychiatry 2017;81:470–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Quinn PD, Meier SM, D'Onofrio BM.. Need to account for familial confounding in systematic review and meta-analysis of prenatal tobacco smoke exposure and schizophrenia. Nicotine Tob Res 2020;22:1928–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Munafò MR, Tilling K, Taylor AE, Evans DM, Davey Smith G.. Collider scope: when selection bias can substantially influence observed associations. Int J Epidemiol 2018;47:226–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Bellón JA, de Dios Luna J, Moreno B. et al. Psychosocial and sociodemographic predictors of attrition in a longitudinal study of major depression in primary care: the predictD-Spain study. J Epidemiol Community Health 2010;64:874–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Fischer EH, Dornelas EA, Goethe JW.. Characteristics of people lost to attrition in psychiatric follow-up studies. J Nerv Ment Dis 2001;189:49–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Zheutlin AB, Dennis J, Karlsson Linnér R. et al. Penetrance and pleiotropy of polygenic risk scores for schizophrenia in 106,160 patients across four health care systems. Am J Psychiatry 2019;176:846–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Crouse JJ, Carpenter JS, Iorfino F. et al. Schizophrenia polygenic risk scores in youth mental health: preliminary associations with diagnosis, clinical stage and functioning. BJPsych Open 2021;7:e58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Lawn RB, Sallis HM, Taylor AE. et al. Schizophrenia risk and reproductive success: a Mendelian randomization study. R Soc Open Sci 2019;6:181049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Nesse R. Cliff-edged fitness functions and the persistence of schizophrenia. Behav Brain Sci 2004;27:862–63. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Millard LAC, Munafò MR, Tilling K, Wootton RE, Davey Smith G.. MR-pheWAS with stratification and interaction: Searching for the causal effects of smoking heaviness identified an effect on facial aging. PLoS Genet 2019;15:e1008353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Simard JF, Rosner BA, Michels KB.. Exposure to cigarette smoke in utero: comparison of reports from mother and daughter. Epidemiology 2008;19:628–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Royal College of Physicians. Smoking and Health. A Report on Smoking in Relation to Lung Cancer and Other Diseases. London: RCP, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Sun D, Zhou T, Li X, Ley SH, Heianza Y, Qi L.. Maternal smoking, genetic susceptibility, and birth-to-adulthood body weight. Int J Obes (Lond) 2020;44:1330–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health. State of Child Health. 2020. https://stateofchildhealth.rcpch.ac.uk (30 November 2022, date last accessed)

- 49. Solmi M, Radua J, Olivola M. et al. Age at onset of mental disorders worldwide: large-scale meta-analysis of 192 epidemiological studies. Mol Psychiatry 2022;27:281–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The UK Biobank dataset used to conduct the research in this paper is available via application directly to the UK Biobank. Applications are assessed for meeting the required criteria for access, including legal and ethics standards. More information regarding data access can be found at [https://www.ukbiobank.ac.uk/enable-your-research].