Abstract

The oceanographic ecology of pelagic Sargassum, and the means by which these floating macroalgae thrive in the nutrient-poor waters of the open ocean, have been studied for decades. Beginning in 2011, the Great Atlantic Sargassum Belt (GASB) emerged, with Sargassum proliferating in the tropical Atlantic and Caribbean where it had not previously been abundant. Here we show that the nutritional status of Sargassum in the GASB is distinct, with higher nitrogen and phosphorus content than populations residing in its Sargasso Sea habitat. Moreover, we find that variations in arsenic content of Sargassum reflect phosphorus limitation, following a hyperbolic relationship predicted from Michaelis-Menten nutrient uptake kinetics. Although the sources of nutrients fueling the GASB are not yet clear, our results suggest that nitrogen and phosphorus content of Sargassum, together with its isotopic composition, can be used to identify those sources, whether they be atmospheric, oceanic, or riverine in origin.

Subject terms: Marine biology, Marine chemistry, Physical oceanography

The Great Atlantic Sargassum Belt is a hazard for coastal communities. Elevated N and P in the GASB are measured, with As content reflecting P limitation. Nutrient availability causes GASB blooms but reducing P would increase As accumulation.

Introduction

The floating macroalgae Sargassum spp. serves as a habitat for more than 200 types of organisms, including 10 endemic species1–3, and provides habitat for fish nursery, spawning, and foraging4,5. Neonate and juvenile sea turtles use Sargassum habitat for feeding as well as protection from predators6,7, and several species of seabirds forage over Sargassum8,9. In contrast to these traditionally beneficial ecological impacts, the Great Atlantic Sargassum Belt10 (GASB) has caused unprecedented inundations of Sargassum on Caribbean and Florida coastlines with deleterious effects on near-shore seagrass and coral reef ecosystems11–14, and declines in turtle hatchling survival15. The GASB has also presented challenges to regional economies, particularly those that rely heavily on tourism16,17. Sargassum decay on coastal margins can cause respiratory and other human health issues18, and the presence of arsenic in Sargassum tissue19–21 puts significant constraints on the utilization of the biomass that washes ashore22–24.

A complex set of interconnected hypotheses has been offered to explain the dynamics of the GASB10,25,26. Anomalous wind patterns in 2009-2010 are thought to have introduced Sargassum from its habitat in the Sargasso Sea into the eastern North Atlantic where it was subsequently entrained into the equatorial current system27. Since that time, Sargassum has increased dramatically in the tropical Atlantic, begging the question of nutrient supply. A variety of nutrient sources have been suggested10,27–29, including upwelling, vertical mixing, discharge from the Amazon and Congo rivers, and atmospheric deposition. However, the causes of the GASB and the mechanisms controlling its seasonal to interannual variability remain unknown. An underlying question is: is this massive abundance of Sargassum a result of higher nutrient availability in the GASB?

In this work we show that GASB Sargassum populations are enriched in both nitrogen and phosphorus content relative to its Sargasso Sea habitat, clearly identifying nutrient supply as a primary driver of this phenomenon. In addition, we demonstrate that Sargassum’s arsenic content varies with the degree of phosphorus limitation, linking our observations with a theoretical prediction based on nutrient uptake kinetics. Our results show that ascertaining the nutrient sources and their regulation is essential to understand the underlying causes of this basin-scale phenomenon—and only then will society have a conceptual basis on which to design potential strategies to mitigate the consequences of the GASB.

Results

Sargassum distributions and nutritional status

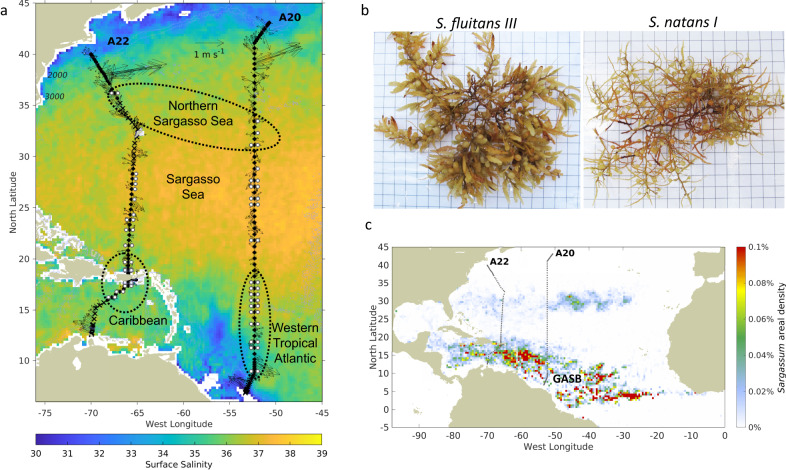

In order to address this question, Sargassum tissue samples were collected in spring 2021 along with hydrographic and nutrient measurements on two hydrographic sections in the western Atlantic (Methods) that intersected the western portion of the GASB (Fig. 1). The samples were separated into two species S. fluitans and S. natans based on their morphology30. S. fluitans and S. natans co-occurred in the southern portions of both A20 and A22. S. natans was more prevalent north of 24°N on A22, and north of 27°N on A20. Both species were present at 32°N on A20 as well as the farthest north sample, collected just south of the Gulf Stream on A22.

Fig. 1. Sargassum sampling on GO-SHIP lines A20 (16 March–16 April 2021) and A22 (20 April–16 May 2021).

a White circles indicate the collection of Sargassum samples, with S. fluitans III shown to the left and S. natans I to the right of the station locations, which are indicated as black circles (where Sargassum sampling was possible), and black Xs (where Sargassum sampling was not possible). Dashed black lines indicate sample groupings in the northern Sargasso Sea, Sargasso Sea, western tropical Atlantic, and Caribbean. Velocity vectors are from the uppermost bin (centered at 29 m depth) of the ship’s acoustic doppler current profiler. The surface salinity field is comprised of a time-average of Soil Moisture and Ocean Salinity (SMOS) satellite measurements for the cruise period (16 March–16 May, 2021). b Photographs of S. fluitans III and S. natans I samples on a 1 cm grid background. Photo credit: Amy Siuda and Jeffrey Schell, Sea Education Association. c Location of GO-SHIP lines A20 and A22 relative to the Great Atlantic Sargassum Belt (contiguous area of Sargassum coverage surrounding the annotation) for the cruise period estimated from MODIS data. Blue lines are the 2000 m and 3000 m isobaths.

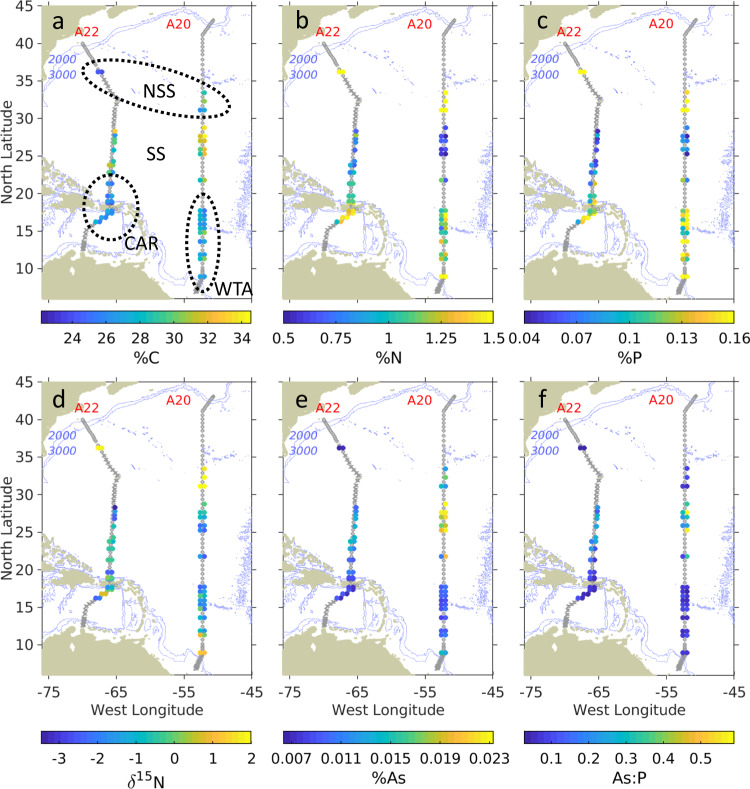

Sargassum elemental composition was similar between species (Fig. 2, Supplementary Table 1), a finding that is consistent with earlier studies29. Our data reveal three distinct regimes within the sampling domain. In the Sargasso Sea, carbon content tends to be relatively high (particularly in the eastern transect A20), whereas nitrogen and phosphorus content tend to be low. Nutritional status in the GASB was much better, with the nitrogen and phosphorus content of Sargassum in the Caribbean and western tropical Atlantic significantly higher than in the Sargasso Sea (Supplementary Fig. 1, Supplementary Table 2). Interestingly, nitrogen and phosphorus content were highest in the northern Sargasso Sea.

Fig. 2. Sargassum tissue data from GO-SHIP lines A20 and A22, as depicted in Fig. 1.

a Carbon content (% dry weight). b Nitrogen content. c Phosphorus content. d δ15N. e Arsenic content. f Arsenic to phosphorus ratio. S. fluitans III is shown to the left of transects A20 and A22, and S. natans I to the right. Stations, where no Sargassum was found, are shown as circles, and stations where Sargassum sampling was not possible are shown as Xs. Dashed black lines in the upper left panel indicate sample groupings in Northern Sargasso Sea (NSS), Sargasso Sea (SS), Caribbean (CAR), and Western Tropical Atlantic (WTA), as in Fig. 1. Blue lines are the 2000 m and 3000 m isobaths.

These trends are also evident in elemental ratios (Supplementary Fig. 2). As expected, C:N was high in the Sargasso Sea, driven by higher carbon content and lower nitrogen content (Fig. 2). These ratios are higher in A20 than in A22, particularly in S. natans. This zonal gradient with C:N increasing to the east is driven by both increasing carbon content and decreasing nitrogen content. C:P is also high in the Sargasso Sea, although the zonal gradient evident in C:N is not clear in C:P. N:P shows a pronounced maximum in the Sargasso Sea region of A22, which is driven by a combination of increased N content and decreased P content. Little meridional trend in N:P is evident in A20, and in aggregate N:P in the Sargasso Sea differs less from the surrounding regions than does C:N and C:P (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Based on the seasonal analysis conducted on prior data sets29, the springtime samples described herein would be expected to be at their seasonal maxima of nitrogen and phosphorus content, and minima of their C:N and C:P ratios.

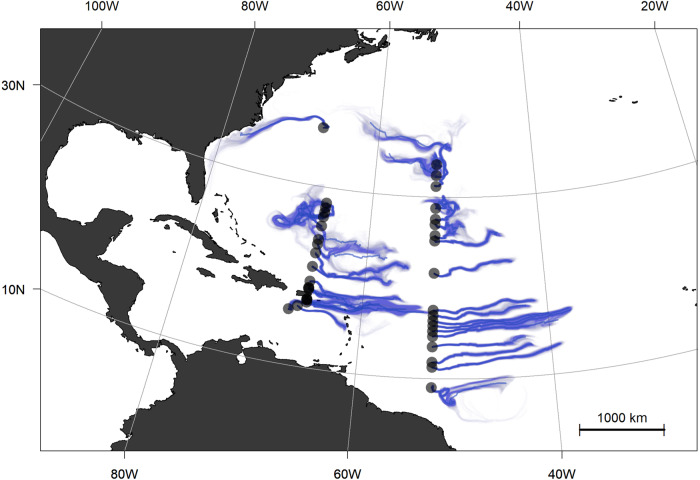

Nutrient sources

Because Sargassum is subject to both surface currents and wind, hydrodynamic transport plays a key role in its dynamics31–33. In order to assess the recent history of our Sargassum samples, passive particles were inserted into a numerical ocean model hindcast at each collection site and tracked backward in time (Fig. 3; see Methods). The southernmost sample of A20 appears to have come from the southeast, whereas samples in the 10–30°N latitude band come primarily from the east. Exceptions to that pattern include an eddy-like flows from 25°N to 28°N on A22. Samples collected north of 30°N on A20 appear to have come from the north, consistent with a Gulf Stream origin. The northernmost sample on A22 was clearly under the influence of the Gulf Stream, although its point of entry into the Gulf Stream varied widely within the ensemble—ranging from the continental shelf north of Cape Hatteras to the South Atlantic Bight, with some in the core of the Gulf Stream as far south as 30°N.

Fig. 3. Origins of Sargassum spp. samples from GO-SHIP lines A20 and A22.

Surface particles deployed at sample collection sites (Figs. 1, 2) were tracked back in time for 60 days. The centroid of the ensemble is shown as a bold blue line with individual trajectories shown in lighter blue.

This information, together with δ15N values of the Sargassum tissue, facilitates some inferences about nitrogen sources. Specifically, Sargassum utilizing riverine nitrogen tend to have enriched (positive) δ15N values, whereas those fueled by near-surface oceanic and atmospheric sources have lower (negative to slightly positive) δ15N values29. Nitrogen fixation typically results in a fractionation of −2‰34.

Patterns in δ15N from our survey reveal spatial coherence, with no systematic difference between S. fluitans and S. natans (Fig. 2). Depleted δ15N values in the Sargasso Sea, Caribbean, and western tropical Atlantic could result from nitrogen fixation by epiphytic cyanobacteria35,36 or perhaps atmospheric deposition37. The highest δ15N values occurred in the northern Sargasso Sea, with values of approximately +2‰ potentially reflecting riverine sources along the U.S. east coast (as indicated by spatial connectivity depicted in Fig. 3), or as distant as the Gulf of Mexico which has been identified as a source region for Sargassum in the western Atlantic38. For example, a coherent plume emanating from the Mississippi River in the summer of 2004 was entrained into the Loop Current, reaching the Straits of Florida in approximately 25 days, continuing northward in the Gulf Stream to be found in the South Atlantic Bight another 25 days after that39. Our northern Sargasso Sea samples were collected another 600 nm farther downstream, so assuming a flow of 4 kt, they could have been influenced by Mississippi River water discharged as recently as 150 days before sampling. With end-member δ15N values of +6–8‰ in the northern Gulf of Mexico Sargassum29, dilution to +2‰ would require several doublings of the population using oceanic sources of nitrogen—which is certainly possible based on observed growth rates36,40,41. Alternatively, enrichment of δ15N in samples from the northern Sargasso Sea could be caused by upwelling and/or vertical mixing, as values of +2‰ are characteristic of nitrate in the upper thermocline in that region42,43.

Enriched δ15N values were also found in the southernmost samples of the western tropical Atlantic (Fig. 2), under the direct influence of the Amazon River plume (as evidenced by the salinity distribution in Fig. 1) which has been implicated as a nutrient source for the GASB10,27–29,44. There was one station in the Caribbean interior (17°N, 67°W) where similarly high δ15N values were measured, but the corresponding salinity (Fig. 1) does not bespeak riverine influence. Particle backtracking calculations suggest source waters to the east-southeast (Fig. 3), and given the cross-isohaline transport enabled by wind drag, Amazon River influence is plausible. However, it is noteworthy that neither the elemental composition (Fig. 2) nor nutrient ratios (Supplementary Fig. 2) in the high-δ15N samples of the tropical Atlantic and Caribbean Sea show corresponding anomalies.

Hydrographic data from sections A20 and A22 provide environmental information with which to interpret the Sargassum observations. The nitracline and phosphocline are deepest in the warm and salty waters of the Sargasso Sea, and shallower in the warmer and fresher waters of the Caribbean and western tropical Atlantic (Supplementary Fig. 3). Both nutriclines are shallower in the colder and fresher waters of the northern Sargasso Sea. Near-surface nutrient concentrations are generally very low except for the northernmost portions of each transect where the nutriclines outcrop. Nitrate and phosphate are at or below the limit of detection in the surface waters Sargasso Sea (Supplementary Fig. 4). Nitrate is enhanced in the Caribbean, and less so in the western tropical Atlantic, where surface phosphate is elevated. The presence of detectable nitrate and phosphate in these areas is consistent with the enhanced nutritional status of Sargassum in the GASB.

Arsenic biogeochemistry

The fact that Sargassum bioaccumulates arsenic has generated considerable interest, particularly because the associated toxicity puts practical limitations on the valorization of the biomass inundating coastal communities of the GASB. Our survey revealed regional scale variations in arsenic content (Fig. 2). Arsenic content was lowest in the GASB (Caribbean and Western Tropical Atlantic samples) and highest in the Sargasso Sea, particularly in the eastern transect A20. Other stations in A20 show modest enrichment, such as in the southernmost samples at 9°N, 52°W and the Northern Sargasso Sea samples at 31–33°N, 52°W. There are no systematic differences in arsenic content between S. fluitans and S. natans (Supplementary Table 1), although interspecies variability is apparent at some stations (Fig. 2).

The high arsenic content of Sargassum in the subtropical gyre is accompanied by the lowest phosphorus content, which is consistent with the depression of the phosphocline (Supplementary Fig. 3) and surface dissolved phosphate concentrations generally below the limit of detection (Supplementary Fig. 4). Thus, the arsenic to phosphorus ratio of Sargassum of the subtropical gyre stands out as uniquely high in that region (Fig. 2), where Sargassum is known to be phosphorus limited45.

Uptake of arsenate (AsO43−) by aquatic plants occurs as a byproduct of phosphorus uptake, owing to its chemical similarity with the phosphate ion (PO43−)46,47. Using the standard Michaelis-Menten form, the uptake of dissolved phosphate and arsenate can be expressed as:

| 1 |

For low concentrations of phosphate and arsenate, uptake is approximately linear in concentration:

| 2 |

The ratio of As to P uptake is therefore:

| 3 |

Surface arsenate concentrations in the tropical and subtropical Atlantic are relatively uniform in comparison with phosphate, and up to an order of magnitude lower48. Moreover, surface concentrations of arsenate and phosphate are uncorrelated49, so the ratio of As to P uptake can be simplified to:

| 4 |

Assuming that the tissue content of these two constituents reflects their proportionate uptake, one would expect that the ratio of arsenic to phosphorus in Sargassum would be a hyperbolic function of phosphorus content:

| 5 |

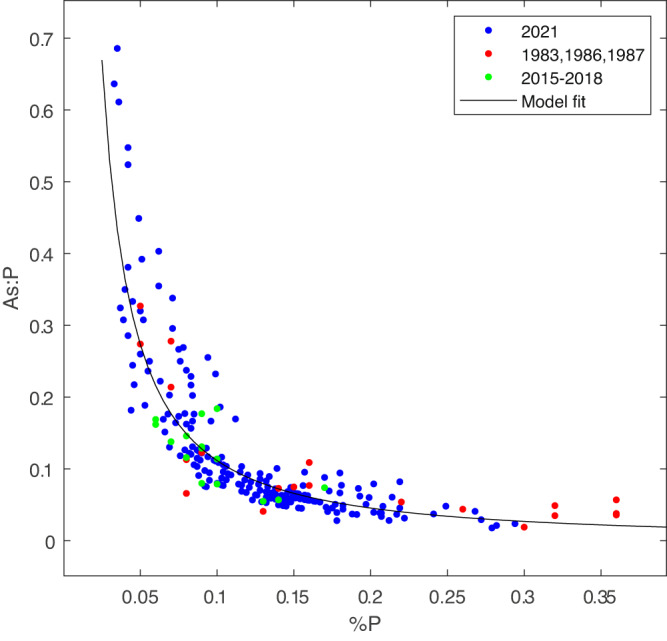

This prediction is qualitatively consistent with the present data as well as prior observations dating back to the 1980s (Fig. 4), although the dependence on phosphorus content varies as %P−1.3 rather than %P−1.0 predicted by the theory. The reason for this supra-hyperbolic dependence is not known, but it is statistically reliable with a p-value < 0.001 (Supplementary Note). This is a clear demonstration of arsenic content as a diagnostic of phosphorus limitation in a natural population of marine algae and is consistent with laboratory studies50,51, biogeochemical proxies based on dissolved As speciation in the ocean49, and other recent field data52.

Fig. 4. Arsenic to phosphorus ratio as a function of phosphorus content in Sargassum tissue.

Data from GO-SHIP lines A20 and A22 in 2021 are in blue (N = 200), 1983–1987 in red (N = 20), and 2015–2018 in green (N = 21). Black line is the fit described in the Supplementary Note.

It could be argued that the As:P versus P relationship in Fig. 4 is a result of the intrinsic association among variables: for two random variables a and b, plotting the ratio a:b versus b will take on a hyperbolic form. However, the elemental composition of Sargassum is not random. For example, the As:C ratio does not show a hyperbolic dependence on carbon content (Supplementary Fig. 5). Interestingly, As:N varies hyperbolically with nitrogen content, which we attribute to covariation in nitrogen and phosphorus content.

Notwithstanding our theoretical prediction of the hyperbolic relationship of As:P and P content, one might also expect a negative correlation between As and P content as a symptom of phosphorus stress in Sargassum. Observations are also consistent with this expectation (Supplementary Fig. 6). A similar negative correlation is observed between arsenic and nitrogen content, which we again attribute to the correlation between nitrogen and phosphorus content. In contrast, As content is positively correlated with carbon content.

Discussion

Nutrient limitation of oceanic Sargassum populations in their native habitat was demonstrated decades ago45,53, and enhanced nutrient availability has been advanced as a key factor in stimulating the GASB10,27,29. We show clearly for the first time that Sargassum in the GASB is enhanced in both nitrogen and phosphorus, indicative of a healthy and thriving population. Stable nitrogen isotope values point to riverine sources in some circumstances and are more equivocal in others. Distinguishing the various nutrient sources sustaining the GASB will require systematic snapshots of nutrient content and isotopic composition across its entire breadth. Presumably, the closer one gets to the source, the higher the nitrogen and / or phosphorus content of Sargassum should be. In that sense, basin-wide patterns in nitrogen and phosphorus elemental composition could provide the fingerprinting necessary to unequivocally determine the sources. However, given the strong seasonal to interannual variability intrinsic to the GASB, it will be essential that such snapshots be synoptic, which poses significant practical challenges for a phenomenon of this scale.

Our demonstration of arsenic content as an indicator of phosphorus stress in natural populations of Sargassum also has considerable implications. Sargassum inundating coastal areas of the GASB already contains arsenic concentrations that can exceed safe thresholds for consumption22–24. If the phosphorus supply to the GASB were to wane relative to that of nitrogen, our findings would suggest that the arsenic content of Sargassum in that area would rise even further, perhaps up to levels currently observed in the Sargasso Sea. This would have important implications for management if the nutrient sources turn out to be anthropogenic.

For all these reasons, expanded observational and modeling studies are needed to understand the GASB’s physical, biological, and chemical drivers. Moreover, the societal need for scientific understanding is urgent: improved seasonal to interannual predictions would offer tremendous value for proactive planning and response, while quantification of the underlying causes could inform potential management actions to mitigate the problem.

Methods

Sampling was conducted on R/V Thomas G. Thompson voyages TN389 (16 March–16 April 2021) and TN390 (20 April–16 May 2021), occupying GO-SHIP lines A2054 and A2255, respectively.

Hydrography

Hydrographic profiles and water samples were collected with a standard Conductivity, Temperature, Depth (CTD) rosette system with Niskin bottles. Nutrient analyses were carried out at sea using a Seal Analytical continuous-flow AutoAnalyzer 3, consistent with the methods described in the GO-SHIP repeat hydrography manual56.

Sargassum collection and identification

Sargassum spp. samples were collected with a dip net and sorted into the species and morphotypes, S. natans I and S. fluitans III per Parr30. Recent literature has indicated the increasing presence of a previously rare form S. natans V III on the basis of both morphology26 and genetics57,58. Based on morphological similarity, any S. natans V III in our samples would have been classified as S. fluitans III.

Sargassum elemental analysis and isotopic composition

Samples for each morphotype were separated into up to three replicates as quantities allowed (6 to 10 thalli/species), rinsed briefly (3 to 5 s) in deionized water, cleaned of macroscopic epizoa and epiphytes, dried in a laboratory oven at 65 to 70 °C for 48 h, and powdered with a mortar and pestle53. The dried Sargassum samples were split in half and stored in plastic screw top vials. One half was used for arsenic analysis (see below), and the other half was shipped to the University of Georgia’s Center for Applied Isotope Studies Stable Isotope Ecology Laboratory (UGA-SIEL; https://cais.uga.edu/facilities/stable-isotope-ecology-laboratory/) for analysis of δ15N as well as %C and %N on a Thermo Delta V IRMS coupled to a Carlo Erba NA1500 CHN-Combustion Analyzer via a Thermo Conflo Interface. National Institute of Standards and Technology reference materials 8549, 8558, 8568, and 8569 were used to routinely calibrate working standards prepared in the laboratory. QA/QC results were incorporated into the raw data reports received by UGA-SIEL. The other part of this half sample was analyzed at UGA-SIEL for %P, where approximately 2 mg of dried tissue was weighed into crucibles, ashed at 500 °C for four hours, and extracted with 0.2 mL of Aqua Regia acid59,60. The acid extracts were then diluted 41:1 with deionized water for TP (as PO4-P) analysis on an Alpkem 300 series analyzer.

Sargassum arsenic content

Arsenic content of Sargassum tissue was measured by the University of Missouri Soil and Plant Testing Laboratory (MU SPTL) using an Inductively Coupled Plasma Optical Emission Spectrometer (ICP-OES; Agilent 5800; λAs = 188.980 nm). Subsamples of rinsed, dried, and powdered Sargassum tissue from the GO-SHIP A20/A22 expeditions were digested at MU SPTL in 2022 according to EPA method 3052. In brief, the powdered samples were digested with a combination of HNO3 acid at 175 °C for 15 min using a microwave-accelerated digestion system (CEM MARS Xpress). Samples collected prior to the 2021 surveys were retrieved from the B. Lapointe archives (1980–2018) at the Harbor Branch Oceanographic Institute, Florida Atlantic University. Prior to sending to the MU SPTL for ICP-OES analysis, this subset was digested at the National High Magnetic Field Laboratory at Florida State University (P. Morton) in 2020 following a two-step process. First, ~0.1 g aliquots of the powdered sample were carefully weighed into 15-mL Teflon digestion beakers (Savillex), to which 3 mL of concentrated HNO3 acid (Fisher Optima) were added. The beakers were tightly capped and left overnight ( ~ 12 h) on a hotplate at 150 °C. The beakers were then uncapped, and the digested sample was taken to dryness (150 °C, 2–4 h). The sample residue was then digested a second time (capped, 150 °C, overnight) using 3 mL concentrated HNO3 (Fisher Optima) and 200 µL of concentrated HF (Fisher Optima). The samples were taken to dryness again (uncapped, 150 °C), and the residue dissolved in 3.0 mL of 0.32 M HNO3 (Fisher Optima).

All samples were analyzed at MU SPTL with ICAP-OES at a 1/100 dilution to bring the As concentrations into a working range of the matrix-matched (0.16 M HNO3) external standard calibration curve. Triplicate independent digestions and analyses of four Sargassum tissue samples were used to determine the representative reproducibility of the sample processing and instrumental analysis methods. For more details see https://extension.missouri.edu/programs/soil-and-plant-testing-laboratory/spl-researchers.

Backtracking of source waters

At each station where Sargassum was collected, the source waters were assessed by tracking particles backward in time for 60 days using a Lagrangian algorithm61. Surface currents were specified from the OSCAR 1/3° resolution analysis, described at https://www.esr.org/research/oscar/oscar-surface-currents/ and available at https://podaac.jpl.nasa.gov/dataset/OSCAR_L4_OC_third-deg. A total of 100 particles were released at each location where Sargassum was found, with random walk diffusion applied each time step Δt with gaussian perturbations σ defined by . The horizontal diffusivity D was chosen to be 4000 m2 s−1 based on estimates for this region derived from Argo float observations62. In addition to being affected by surface currents, wind also influences Sargassum transport31,32. Windage factors ranging from 0.5% and 3% produce the most accurate simulations of Sargassum trajectories63,64, and a mid-point value of 2% was used here. Wind forcing was specified using daily NCEP/NCAR reanalysis65 and validated with shipboard meteorological measurements made on R/V Thomas G. Thompson during voyages TN389 and TN390.

Trajectories for each virtual particle were plotted in Fig. 3 using R and TheSource61. Transparency was used to visually indicate relative variance in particle trajectories, and the mean path for each station was overlaid. The script used to run the model and generate the plot is available at https://gist.github.com/tbrycekelly/830f5278269ba46df15f883c1c3cccc5.

Satellite observations

Pelagic Sargassum distributions (https://optics.marine.usf.edu/projects/saws.html) were derived from MODIS measurements using a floating algal index10,66,67. MODIS data were obtained from the U.S. National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) Goddard Space Flight Center (https://oceancolor.gsfc.nasa.gov). Surface salinity distributions were obtained from SMOS Earth Explorer mission and the data were accessed from https://www.catds.fr/Products/Products-over-Ocean/CEC-Lops-SSS-SMOS-SMAP-OI-L4.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

Sargassum samples of opportunity were collected on U.S. GO-SHIP lines A20 (Ryan Woosley, Chief Scientist), and A22 (Viviane Menezes, Chief Scientist), carried out on the R/V Thomas G. Thompson (voyages TN389 and TN390) with the support of NSF and NOAA. We greatly appreciate the efforts of all who participated in the collection, processing, and preservation of the samples on these cruises, particularly Christine Klimkowski, Jennifer Nomura, Elizabeth Ricci, and Stephen Jalickee. Likewise, we thank Kevin Tyre, Allyson DiMarco, Dave Milmore, Jennifer Cannizzaro, and Kristie Dick for their efforts processing cruise samples. D.J.M. gratefully acknowledges partial support of this effort by the National Science Foundation (Grant Number OCE-1840381) and the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (Grant Number 1P01ES028938) through the Woods Hole Center for Oceans and Human Health, as well as internal support provided by the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution and the Isham Family Charitable Fund. D.J.M. thanks O. Kosnyrev for her skillful data analysis and visualization. C.H., R.A.B., and B.E.L. acknowledge the support of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (Grant Number 80NSSC20M0264). We thank Yingjun Zhang for the SMOS salinity analysis that went into Fig. 1. A portion of P. Morton’s work was performed at the National High Magnetic Field Laboratory, which is supported by National Science Foundation Cooperative Agreement No. DMR-1644779 and the State of Florida.

Author contributions

D.J.M. Conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, investigation, writing-original draft, writing-reviewing and editing. R.A.B. Data curation, writing - review and editing. C.H. Investigation, writing - review and editing. T.B.K. Investigation, writing - review and editing. P.L.M. Investigation, resources, writing – review and editing. A.R.S. Formal analysis, writing – review and editing. B.E.L. Conceptualization, methodology, investigation, writing-reviewing and editing.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Pamela Fernandez and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Data availability

The Sargassum tissue data generated in this study have been deposited in the Figshare database under accession code 10.6084/m9.figshare.2268450768. Shipboard hydrographic data: https://cchdo.ucsd.edu/cruise/325020210316 (TN38954). https://cchdo.ucsd.edu/cruise/325020210420 (TN39055). Surface currents used for particle tracking: https://podaac.jpl.nasa.gov/dataset/OSCAR_L4_OC_third-deg69. Satellite-based surface salinity: https://www.catds.fr/Products/Products-over-Ocean/CEC-Lops-SSS-SMOS-SMAP-OI-L470. Ocean color data for computation of satellite-based Sargassum distributions: https://oceancolor.gsfc.nasa.gov71.

Code availability

Particle tracking code: 10.5281/zenodo.346852461.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41467-023-41904-4.

References

- 1.Martin LM, et al. Pelagic Sargassum morphotypes support different rafting motile epifauna communities. Mar. Biol. 2021;168:115. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coston-Clements, L., Settle, L. R., Hoss, D. E. & Cross, F. A. Utilization of the Sargassum habitat by marine invertebrates and vertebrates, a review. NOAA Tech. Memo. NMFS-SEFSC 296, (1991).

- 3.Huffard CL, von Thun S, Sherman AD, Sealey K, Smith KL. Pelagic Sargassum community change over a 40-year period: temporal and spatial variability. Mar. Biol. 2014;161:2735–2751. doi: 10.1007/s00227-014-2539-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.NMFS. National Marine Fisheries Service Fisheries of the Caribbean, Gulf of Mexico and South Atlantic; pelagic Sargassum habitat of the south Atlantic region (Final Rule) Fed. Regist. 2003;68:57375. [Google Scholar]

- 5.ICCAT. Resolution 05–11 on pelagic Sargassum. Compendium Management Recommendations and Resolutions adopted by ICCAT for the Conservation of Atlantic tunas and tuna-like species, (2005).

- 6.Mansfield KL, Wyneken J, Porter WP, Luo J. First satellite tracks of neonate sea turtles redefine the ‘lost years’ oceanic niche. Proc. Biol. Sci. 2014;281:20133039. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2013.3039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Witherington B, Hirama S, Hardy R. Young sea turtles of the pelagic Sargassum-dominated drift community: habitat use, population density, and threats. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2012;463:1–22. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haney JC. Seabird patchiness in tropical oceanic waters: the influence of Sargassum “Reefs”. Auk. 1986;103:141–151. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moser ML, Lee DS. Foraging over Sargassum by western North Atlantic seabirds. Wilson J. Ornithol. 2012;124:66–72. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang M, et al. The great Atlantic Sargassum belt. Science. 2019;365:83–87. doi: 10.1126/science.aaw7912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van Tussenbroek BI, et al. Severe impacts of brown tides caused by Sargassum spp. on near-shore Caribbean seagrass communities. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2017;122:272–281. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2017.06.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rodríguez-Martínez RE, et al. Faunal mortality associated with massive beaching and decomposition of pelagic Sargassum. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2019;146:201–205. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2019.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alvarez-Filip L, Estrada-Saldívar N, Pérez-Cervantes E, Molina-Hernández A, González-Barrios FJ. A rapid spread of the stony coral tissue loss disease outbreak in the Mexican Caribbean. PeerJ. 2019;7:e8069. doi: 10.7717/peerj.8069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cabanillas-Terán N, Hernández-Arana H, Ruiz-Zárate M, Vega-Zepeda A, Sanchez-Gonzalez A. Sargassum blooms in the Caribbean alter the trophic structure of the sea urchin Diadema antillarum. PeerJ. 2019;7:e7589. doi: 10.7717/peerj.7589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maurer AS, De Neef E, Stapleton S. Sargassum accumulation may spell trouble for nesting sea turtles. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2015;13:394–395. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Louime C, Fortune J, Gervais G. Sargassum invasion of coastal environments: a growing concern. Am. J. Environ. Sci. 2017;13.1:58–64. [Google Scholar]

- 17.United Nations Environment Programme. Sargassum White Paper - Sargassum Outbreak in the Caribbean: Challenges, Opportunities and Regional Situation. Eighth Meeting of the Scientific and Technical Advisory Committee (STAC) to the Protocol Concerning Specially Protected Areas and Wildlife (SPAW) in the Wider Caribbean Regionhttps://wedocs.unep.org/20.500.11822/35948 (2018).

- 18.Resiere D, et al. Sargassum seaweed on Caribbean islands: an international public health concern. Lancet (Lond., Engl.) 2018;392:2691. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32777-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dassié EP, Gourves P-Y, Cipolloni O, Pascal P-Y, Baudrimont M. First assessment of Atlantic open ocean Sargassum spp. metal and metalloid concentrations. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022;29:17606–17616. doi: 10.1007/s11356-021-17047-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johnson DL, Braman RS. The speciation of arsenic and the content of germanium and mercury in members of the pelagic Sargassum community. Deep Sea Res. 1975;22:503–507. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cipolloni O-A, et al. Metals and metalloids concentrations in three genotypes of pelagic Sargassum from the Atlantic Ocean Basin-scale. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2022;178:113564. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2022.113564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rodríguez-Martínez, R. E. et al. Element concentrations in pelagic Sargassum along the Mexican Caribbean coast in 2018-2019. PeerJ8 (2020). 10.7717/peerj.8667 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Oxenford HA, Cox S-A, van Tussenbroek BI, Desrochers A. Challenges of turning the Sargassum crisis into gold: current constraints and implications for the Caribbean. Phycology. 2021;1:27–48. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Devault DA, et al. The silent spring of Sargassum. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021;28:15580–15583. doi: 10.1007/s11356-020-12216-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smetacek V, Zingone A. Green and golden seaweed tides on the rise. Nature. 2013;504:84–88. doi: 10.1038/nature12860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schell JM, Goodwin DS, Siuda ANS. Recent Sargassum inundation events in the Caribbean: shipboard observations reveal dominance of a previously rare form. Oceanography. 2015;28:8–11. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Johns EM, et al. The establishment of a pelagic Sargassum population in the tropical Atlantic: biological consequences of a basin-scale long distance dispersal event. Prog. Oceanogr. 2020;182:102269. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oviatt CA, Huizenga K, Rogers CS, Miller WJ. What nutrient sources support anomalous growth and the recent Sargassum mass stranding on Caribbean beaches? A review. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2019;145:517–525. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2019.06.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lapointe BE, et al. Nutrient content and stoichiometry of pelagic Sargassum reflects increasing nitrogen availability in the Atlantic Basin. Nat. Commun. 2021;12:3060. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-23135-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Parr AE. Quantitative observations on the pelagic Sargassum vegetation of the Western North Atlantic: with preliminary discussion of morphology and relationships. Bull. Bingham Oceanogr. Collect. 1939;6:1–94. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Putman NF, et al. Simulating transport pathways of pelagic Sargassum from the Equatorial Atlantic into the Caribbean Sea. Prog. Oceanogr. 2018;165:205–214. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Beron-Vera FJ, et al. Dynamical geography and transition paths of Sargassum in the tropical Atlantic. AIP Adv. 2022;12:105107. [Google Scholar]

- 33.van Sebille, E. et al. Dispersion of Surface Drifters in the Tropical Atlantic. Front. Marine Sci.7 (2021). 10.3389/fmars.2020.607426

- 34.Montoya, J. P. in Nitrogen in the Marine Environment (Second Edition) (eds Douglas G. Capone, Deborah A. Bronk, Margaret R. Mulholland, & Edward J. Carpenter) 1277-1302 (Academic Press, 2008).

- 35.Carpenter EJ. Nitrogen fixation by a blue-green epiphyte on Pelagic Sargassum. Science. 1972;178:1207–1209. doi: 10.1126/science.178.4066.1207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Carpenter EJ, Cox JL. Production of pelagic Sargassum and a blue-green epiphyte in the western Sargasso Sea. Limnol. Oceanogr. 1974;19:429–436. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kendall, C., Elliott, E. M. & Wankel, S. D. in Stable Isotopes in Ecology and Environmental Science (eds R. Michener & K. Lajtha) Ch. 12, 375-449 (Blackwell Publishing, 2007).

- 38.Gower, J. & King, S. Satellite Images Show the Movement of Floating Sargassum in the Gulf of Mexico and Atlantic Ocean. Nature Precedings10.1038/npre.2008.1894.1 (2008).

- 39.Hu, C. et al. Mississippi River water in the Florida Straits and in the Gulf Stream off Georgia in summer 2004. Geophysical Research Letters32 (2005). 10.1029/2005GL022942

- 40.Magaña-Gallegos E, et al. Growth rates of pelagic Sargassum species in the Mexican Caribbean. Aquat. Bot. 2023;185:103614. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hanisak, M. D. & Samuel, M. A. in Twelfth International Seaweed Symposium. (eds Mark A. Ragan & Carolyn J. Bird) 399-404 (Springer Netherlands, 1987).

- 42.Knapp AN, DiFiore PJ, Deutsch C, Sigman DM, Lipschultz F. Nitrate isotopic composition between Bermuda and Puerto Rico: Implications for N2 fixation in the Atlantic Ocean. Glob. Biogeochemical Cycles. 2008;22:1–14. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Knapp, A. N., Sigman, D. M. & Lipschultz, F. N isotopic composition of dissolved organic nitrogen and nitrate at the Bermuda Atlantic Time-series Study site. Global Biogeochemical Cycles19 (2005). 10.1029/2004GB002320

- 44.Gower J, Young E, King S. Satellite images suggest a new Sargassum source region in 2011. Remote Sens. Lett. 2013;4:764–773. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lapointe BE. Phosphorus-limited photosynthesis and growth of Sargassum natans and Sargassum fluitans (Phaeophyceae) in the western North Atlantic. Deep Sea Res. Part A. Oceanographic Res. Pap. 1986;33:391–399. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Benson AA, Katayama M, Knowles FC. Arsenate metabolism in aquatic plants. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 1988;2:349–352. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sanders JG. The concentration and speciation of arsenic in marine macro-algae. Estuar. Coast. Mar. Sci. 1979;9:95–99. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cutter GA, Cutter LS, Featherstone AM, Lohrenz SE. Antimony and arsenic biogeochemistry in the western Atlantic Ocean. Deep Sea Res. Part II: Topical Stud. Oceanogr. 2001;48:2895–2915. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wurl O, Zimmer L, Cutter GA. Arsenic and phosphorus biogeochemistry in the ocean: Arsenic species as proxies for P-limitation. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2013;58:729–740. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mamun MAA, et al. Bioaccumulation and biotransformation of arsenic by the brown macroalga Sargassum patens C. Agardh in seawater: effects of phosphate and iron ions. J. Appl. Phycol. 2019;31:2669–2685. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sanders JG, Windom HL. The uptake and reduction of arsenic species by marine algae. Estuar. Coast. Mar. Sci. 1980;10:555–567. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gobert T, et al. Trace metal content from holopelagic Sargassum spp. sampled in the tropical North Atlantic Ocean: Emphasis on spatial variation of arsenic and phosphorus. Chemosphere. 2022;308:136186. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2022.136186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lapointe BE. A comparison of nutrient-limited productivity in Sargassum natans from neritic vs. oceanic waters of the western North Atlantic Ocean. Limnol. Oceanogr. 1995;40:625–633. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Woosley, R. & Thurnherr, A. M. Hydrographic data from voyage TN389 of the R/V Thomas G. Thompson. https://cchdo.ucsd.edu/cruise/325020210316 (2021).

- 55.Menezes, V. & Anderson, J. Hydrographic data from voyage TN390 of the R/V Thomas G. Thompson. https://cchdo.ucsd.edu/cruise/325020210420 (2021).

- 56.Becker, S. et al. in GO-SHIP Repeat Hydrography Manual: A Collection of Expert Reports and Guidelineshttps://www.go-ship.org/HydroMan.html (GO-SHIP Program and SCOR, 2019).

- 57.Dibner S, et al. Consistent genetic divergence observed among pelagic Sargassum morphotypes in the western North Atlantic. Mar. Ecol. 2022;43:e12691. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Amaral-Zettler LA, et al. Comparative mitochondrial and chloroplast genomics of a genetically distinct form of Sargassum contributing to recent “Golden Tides” in the Western Atlantic. Ecol. evolution. 2016;7:516–525. doi: 10.1002/ece3.2630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Allen, S. E., Grimshaw, H. M., Parkinson, J. A., Quarmby, C. & Roberts, J. D. Chemical Analysis of Ecological Materials. (Blackwell Scientific Publications, 1974).

- 60.Jones, J. B., Wolf, B. & Mills, H. A. in Plant Analysis Handbook 195-196 (Micro-Macro Publishing, 1990).

- 61.Kelly, T. B. TheSource: An R library of simple utilities to facilitate research (V0.1.6). Zenodo (2019). 10.5281/zenodo.3468524

- 62.Cole ST, Wortham C, Kunze E, Owens WB. Eddy stirring and horizontal diffusivity from Argo float observations: Geographic and depth variability. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2015;42:3989–3997. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Berline L, et al. Hindcasting the 2017 dispersal of Sargassum algae in the Tropical North Atlantic. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2020;158:111431. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2020.111431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Putman NF, Lumpkin R, Olascoaga MJ, Trinanes J, Goni GJ. Improving transport predictions of pelagic Sargassum. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 2020;529:151398. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kalnay E, et al. The NCEP/NCAR 40-Year Reanalysis Project. Bull. Am. Meteorological Soc. 1996;77:437–472. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wang M, Hu C. Mapping and quantifying Sargassum distribution and coverage in the Central West Atlantic using MODIS observations. Remote Sens. Environ. 2016;183:350–367. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hu C. A novel ocean color index to detect floating algae in the global oceans. Remote Sens. Environ. 2009;113:2118–2129. [Google Scholar]

- 68.McGillicuddy, D. J. et al. Nutrient and arsenic biogeochemistry of Sargassum in the western Atlantic. Figshare, 10.6084/m6089.figshare.22684507 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 69.ESR. OSCAR third deg. Ver. 1. PO.DAAC, 10.5067/OSCAR-5003D5001 (2009).

- 70.Kolodziejczyk, N. et al. SSS SMOS/SMAP OI L4 maps. SEANOE, 10.17882/73142 (2020).

- 71.NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, Ocean Ecology Laboratory, Ocean Biology Processing Group. Moderate-resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) Aqua Data. NASA OB.DAAC, 10.5067/AQUA/MODIS/L5062/OC/2022 (2022).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The Sargassum tissue data generated in this study have been deposited in the Figshare database under accession code 10.6084/m9.figshare.2268450768. Shipboard hydrographic data: https://cchdo.ucsd.edu/cruise/325020210316 (TN38954). https://cchdo.ucsd.edu/cruise/325020210420 (TN39055). Surface currents used for particle tracking: https://podaac.jpl.nasa.gov/dataset/OSCAR_L4_OC_third-deg69. Satellite-based surface salinity: https://www.catds.fr/Products/Products-over-Ocean/CEC-Lops-SSS-SMOS-SMAP-OI-L470. Ocean color data for computation of satellite-based Sargassum distributions: https://oceancolor.gsfc.nasa.gov71.

Particle tracking code: 10.5281/zenodo.346852461.