As the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic swept the globe, clinicians, researchers, and the public wondered: who has the highest risk to become most severely ill? Early findings that the elderly and individuals with comorbidities were the most vulnerable fit the predominant conceptual model: severe disease results from pathogen-induced damage that is exacerbated by dysfunctional pathogen clearance or by immune overreaction underlying immunopathology and further facilitated by pre-existing organ dysfunction unable to withstand new threats.

This conceptual model is the basis for medical interventions that directly target pathogens, such as vaccinations, treatment with antimicrobials, and steps to minimize immunopathology. Indeed, these approaches successfully improved the outcome in many subsets of COVID-19 patients. However, severe disease frequently continued to progress among individuals with no known risk factors, while some comorbid elders survived unscathed. So, what are the biologic mechanisms that spared individuals expected to fare poorly and failed in those expected to do well? Perhaps the assumption that non-immune cells are passive to infection-mediated stress should be re-considered?

Here, we discuss evidence that severe disease after infection is perhaps best understood when incorporating a critical, regulated feature of host defense against infections known as disease tolerance. [1]

Disease tolerance

Disease tolerance was first defined more than a century ago as a defense strategy of plants that limits fitness costs of infection without an apparent reduction of pathogen burden. [2] Importantly, disease tolerance is distinct from immune tolerance, a term used broadly to define core properties of the immune system, underlying self–nonself discrimination and hyporesponsiveness. It is also distinct from resistance, another immune system function that limits the severity of infectious diseases via mechanisms that decrease pathogen burden.

Functionally, disease tolerance is a product of tissue damage control mechanisms [1, 3]. These rewire immune and parenchymal metabolism promoting adaptive homeostasis [4], to allow vital organs to withstand functional constraints associated with severe infections [3].

Protection from severe disease was shown for infections with viruses [5], bacteria [6–8] and protozoa [9]. Whether the involved regulatory pathways are common at the tissue and cell level remains to be elucidated. In humans, disease tolerance is best documented for malaria in which the clinical outcomes cannot be readily explained by variations in pathogen burden [10]. Moreover, sickle hemoglobin mutations, arguably the strongest protective trait against human malaria, induce disease tolerance in experimental models of Plasmodium infection [9]. These and other studies [11, 12] support the notion that disease tolerance is a central evolutionarily conserved defense strategy against infectious diseases. However, in human sepsis, the protection afforded by tissue damage control mechanisms, the biological regulatory mechanisms of adaptive responses involved in disease tolerance are unknown.

During intensive care, a conceptual model that encompasses disease tolerance could considerably expand the horizon for future therapeutic targets. Novel strategies could target pathophysiologic mechanisms employed by tissues and organs to limit damage and dysfunction rather than focus only on immune modulation and pathogen clearance. To target disease tolerance mechanisms therapeutically, we might not need completely new pharmaceuticals. Even re-purposed drugs were shown to promote disease tolerance. For example, low doses of antineoplastic anthracyclines activate cellular damage responses and improve sepsis survival without affecting bacterial loads in mice [7]. This approach to modify disease tolerance is the basis of an ongoing phase II dose-escalation trial (EPOS-1; ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT05033808), randomizing sepsis patients to low dose epirubicin vs. placebo.

Challenges

Quantifying pathogen load

A direct assessment of disease tolerance requires, by definition, a quantified measurement of the hosts’ pathogen load. While feasible in experimental models of infection, quantifying pathogen load in patients (e.g. via cultures or polymerase chain reaction), is challenging and semi-quantitative at best, failing to provide an accurate pathogen count in the bloodstream and less so in the entire organism. An alternative to measuring pathogen load in the blood is to assess tissue damage control directly. However, access to most parenchymal tissue is not practical in humans, and may require more invasive biospecimens or the identification of surrogate measures. An ideal surrogate would be (1) rapidly quantifiable, (2) reflective of real-time changes in tolerance, (3) minimally invasive, (4) not directly affected by treatments, and (5) preferably cost-effective. For single or multi-scale tolerance read-outs, the blood and pulmonary compartments may be the most readily accessible and reflective of these conserved mechanisms on the whole-host level.

Disease tolerance is dynamic

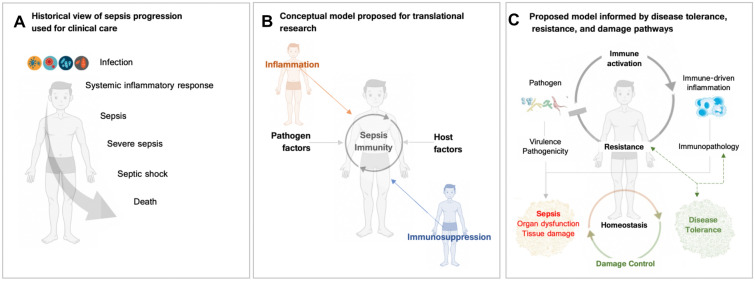

Clearly, some static baseline patients’ characteristics such as age or comorbidities, contribute to the underlying rather static capacity to tolerate infections. Potentially, the mortality differences in frail and obese sepsis patients represent different capacities of metabolic adaptation, a key feature of disease tolerance as described earlier. Some disease tolerance features, however, are dynamically regulated, and act most likely in a tissue type-specific manner to sustain organ function [4]. These include regulated variables such plasma glucose [6] or lactate [8]. In conjunction with damage control mechanisms [3], their regulation provides optimal adaptation to infection-mediated stress [2]. Another example for dynamic features of disease tolerance may be the systemic hypometabolic state imposed by sepsis that shares features with physiological hibernation [13] which is thought to contribute critically to multiorgan dysfunction [6]. In early sepsis, a hypometabolic response may be protective to optimize energy expenditure, but if sustained in late sepsis it may be detrimental. Such a dynamic nature emphasizes the importance of having real-time and measurable disease tolerance signatures. These could be used to build disease trajectories that reflect and predict sepsis phases and are modifiable by precision treatment [14] (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

A Early conceptual model of sepsis progression from infection to systemic inflammatory response to sepsis and death. Popularized in early sepsis definitions, criteria, and clinical practice guidelines, this model assisted clinical care but was agnostic to underlying biology [15]. B Model proposed for translational and clinical research that includes awareness of both the hyper- and hypo-inflammatory host responses in sepsis, as well as the modifying factors of host fitness and pathogens themselves. [16]. C Conceptual model of infection and host response that includes both dysfunction/damage, imposed by pathogens and/or by immune-driven resistance mechanisms as well as disease tolerance as a key regulator of sepsis progression [1, 3]. In brief, pathogenic microorganisms directly inflict damage to the host (“Virulence”) and induce the activation of the immune systems, ("Immune-driven inflammation") that in the early phase after infection aims at pathogens elimination ("Resistance"). As a trade-off, resistence mechanisms can inflict damage to non-immune cells of the host (“Immunopathology”). “Damage Control” mechanisms counter infection-associated stress, promote maintenance of “Homeostasis” and as such establish “Disease Tolerance” and limit disease severity

Take-home messages

Disease tolerance is a protective strategy that -if functional- prevents severe disease after infection. Perhaps due to the success of microbiological and immunological approaches and their dominance in our clinical routine to explain and treat infections, most clinicians and researchers do not yet include disease tolerance in their perception of critical illness or sepsis. Undoubtedly, pathogen elimination will remain unconditional in treating infections. Yet, most severe disease and death nowadays are a direct consequence of organ dysfunction rather than uncontrolled pathogen growth. Understanding disease tolerance will lead to fundamental insights into recovery and open yet hidden paths to precision medicine.

Acknowledgements

We thank Michael Bauer (Jena University Hospital), Luis F. Moita (Instituto Gulbenkian de Ciência) as well as Christopher W. Seymour and Derek C. Angus (University of Pittsburgh) for their critical discussions and the revision of the manuscript.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. REP is supported by funding from the NIH (5T32HL007563-34). MPS is supported by the Gulbenkian, “La Caixa” (HR18-00502) and FCT (5723/2014; FEDER029411) foundations as well as by Oeiras-ERC Frontier Research Incentive Awards. MPS is an associate member of the Excellence Cluster Balance of the Microverse (EXC 2051; 390713860). SW is currently funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, DFG, project number WE 4971/6-1, the Excellence Cluster Balance of the Microverse (EXC 2051; 390713860), the Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) project number 01EN2001.

Declarations

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Medzhitov R, Schneider DS, Soares MP. Disease tolerance as a defense strategy. Science. 2012;335(6071):936–941. doi: 10.1126/science.1214935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cobb NA (1894) Contributions to aneconomic knowledge of Australian rusts (Uredineae) in Agr. Gas. N. S. W.. C. Potter, govt. printer, Sydney, pp 239–250

- 3.Soares MP, Gozzelino R, Weis S. Tissue damage control in disease tolerance. Trends Immunol. 2014;35(10):483–494. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2014.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kotas ME, Medzhitov R. Homeostasis, inflammation, and disease susceptibility. Cell. 2015;160(5):816–827. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ho JSY, et al. TOP1 inhibition therapy protects against SARS-CoV-2-induced lethal inflammation. Cell. 2021;184(10):2618–2632 e17. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.03.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weis S, et al. Metabolic adaptation establishes disease tolerance to sepsis. Cell. 2017;169(7):1263–1275.e14. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.05.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Figueiredo N, et al. Anthracyclines induce DNA damage response-mediated protection against severe sepsis. Immunity. 2013;39(5):874–884. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.08.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vandewalle J, et al. Combined glucocorticoid resistance and hyperlactatemia contributes to lethal shock in sepsis. Cell Metab. 2021;33(9):1763–1776 e5. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2021.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ferreira A, et al. Sickle hemoglobin confers tolerance to Plasmodium infection. Cell. 2011;145(3):398–409. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.03.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marsh K, et al. Indicators of life-threatening malaria in African children. N Engl J Med. 1995;332(21):1399–1404. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199505253322102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Martins R, et al. Disease tolerance as an inherent component of immunity. Annu Rev Immunol. 2019;37:405–437. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-042718-041739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Råberg L, Sim D, Read AF. Disentangling genetic variation for resistance and tolerance to infectious diseases in animals. Science. 2007;318(5851):812–814. doi: 10.1126/science.1148526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brealey D, Singer M. Mitochondrial dysfunction in sepsis. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2003;5(5):365–371. doi: 10.1007/s11908-003-0015-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Torres BY, et al. Tracking resilience to infections by mapping disease space. PLoS Biol. 2016;14(4):e1002436. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1002436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bone RC, et al. Definitions for sepsis and organ failure and guidelines for the use of innovative therapies in sepsis. The ACCP/SCCM Consensus Conference Committee. American College of Chest Physicians/Society of Critical Care Medicine. Chest. 1992;101(6):1644–1655. doi: 10.1378/chest.101.6.1644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Angus DC, van der Poll T. Severe sepsis and septic shock. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(9):840–851. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1208623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]