Abstract

Adoptive regulatory T (Treg) cell therapy is predicted to modulate immune tolerance in autoimmune diseases, including type 1 diabetes (T1D). However, the requirement for antigen (ag) specificity to optimally orchestrate tissue-specific, Treg cell-mediated tolerance limits effective clinical application. To address this challenge, we present a single-step, combinatorial gene editing strategy utilizing dual-locus, dual-homology-directed repair (HDR) to generate and specifically expand ag-specific engineered Treg (EngTreg) cells derived from donor CD4+ T cells. Concurrent delivery of CRISPR nucleases and recombinant (r)AAV homology donor templates targeting FOXP3 and TRAC was used to achieve three parallel goals: enforced, stable expression of FOXP3; replacement of the endogenous T cell receptor (TCR) with an islet-specific TCR; and selective enrichment of dual-edited cells. Each HDR donor template contained an alternative component of a heterodimeric chemically inducible signaling complex (CISC), designed to activate interleukin-2 (IL-2) signaling in response to rapamycin, promoting expansion of only dual-edited EngTreg cells. Using this approach, we generated purified, islet-specific EngTreg cells that mediated robust direct and bystander suppression of effector T (Teff) cells recognizing the same or a different islet antigen peptide, respectively. This platform is broadly adaptable for use with alternative TCRs or other targeting moieties for application in tissue-specific autoimmune or inflammatory diseases.

Keywords: Treg, dual-HDR, CRISPR, AAV6, ag-specific, CISC, enrichment

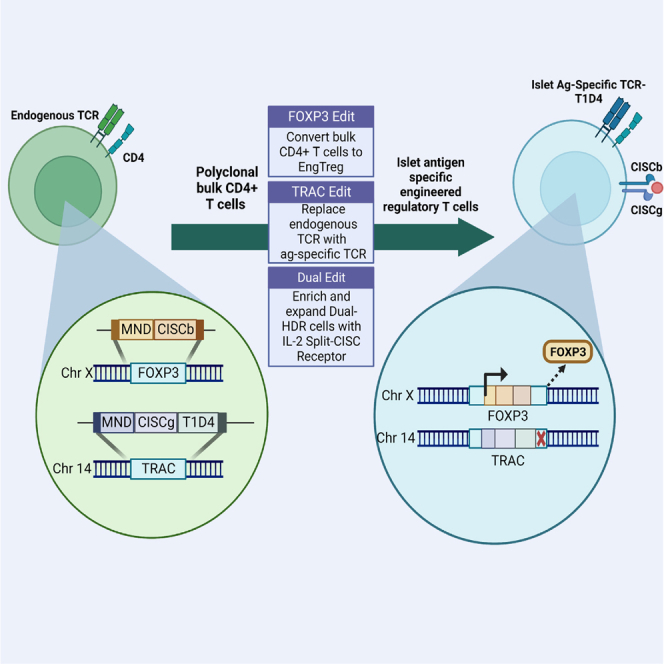

Graphical abstract

Rawlings and colleagues describe a single-step manufacturing strategy involving dual-locus CRISPR-HDR editing, capable of producing enriched diabetes disease-relevant EngTreg cells with robust immunosuppressive capacity. The dual-edited cells bear an inducible synthetic IL-2 receptor split across both loci, allowing selective survival and expansion of the cells of interest in vitro.

Introduction

Adoptive regulatory T cell therapy represents a potentially transformative cell-based approach to promote immune tolerance following stem cell or solid organ transplantation and in autoimmune disorders.1,2 However, key technical hurdles may limit broad clinical application of regulatory T (Treg) cell therapies, including the rarity of patient-derived thymic Treg (tTreg) cells and the requirement for antigen (ag) specificity to optimally modulate tissue-specific inflammation. To overcome some of these challenges, we established a homology-directed repair (HDR)-based gene editing strategy to stably express the Treg cell master transcription factor FOXP3 in primary CD4+ T cells. This approach introduces a constitutively active promoter downstream of the Treg-specific demethylated region (TSDR) to convert bulk CD4+ T cells into immunosuppressive polyclonal engineered Treg (EngTreg) cells.3 Notably, this approach eliminates the epigenetic control required to maintain FOXP3 expression in tTreg cells, reducing the likelihood of loss of FOXP3 expression leading to loss of regulatory activity. In recent work, this FOXP3 gene editing strategy was combined with lentiviral (LV) delivery of T cell receptors (TCRs) derived from type 1 diabetes (T1D) patients to generate pancreatic islet ag-specific EngTreg cells—cells that exhibit robust in vitro suppression of effector T (Teff) cell populations with matched ag specificity as well as bystander suppression of Teff cells targeting distinct islet ags.4 However, because the endogenous TCR was not disrupted, the LV cassette utilized TCR α and β chains containing murine constant regions as a means to promote specific pairing of the exogenous TCR. While this approach provided a key proof of concept, translation to human subjects raises potential concerns regarding safety and efficacy, including possible genotoxicity from LV integration,5,6 immunogenicity of the chimeric TCRs, and lack of a streamlined manufacturing process to expand a purified population.

CRISPR gene editing has become a primary focus in the field of cell-based immunotherapy, using autologous T cells to engineer expression of a chimeric ag receptor (CAR) or a defined TCR. Deletion of the endogenous TCR via CRISPR knockout of the TRAC or TRBC genes have been explored to prevent mispairing between the endogenous and engineered TCR α or β chains and alloreactivity of universal T cell immunotherapies.7,8,9 Recently, new strategies to knock out the endogenous TCR by simultaneous targeted insertion of a defined TCR or CAR by HDR-based editing at the TRAC locus have proven successful.10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20 Insertion strategies have also been developed to capture the endogenous TRAC promoter, resulting in CAR expression and transcriptional regulation similar to the endogenous TCR.18 Alternatively, the defined TCR α chain can be inserted as a fusion of the exogenous α variable region with the endogenous TRAC locus, resulting in a “TRAC hijack” integration strategy that reduces HDR template size and uses the 3′ UTR from the endogenous receptor.13

Additional genome engineering events have been paired with TRAC-targeted TCR replacement in T cells; for instance, B2M locus editing for major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I replacement with human leukocyte ag (HLA)-E.21 In other cell types, multiplexed HDR editing has been demonstrated either at multiple loci or at a single locus by biallelic editing with alternate repair templates targeting a single nuclease cut site.21,22,23,24,25,26,27 Because HDR is less efficient than non-homologous end joining (NHEJ),28 a potential drawback of multiplexed HDR strategies is a low initial frequency of dual-HDR events utilizing both donor repair templates. Current strategies to enrich dual-positive, dual-edited cells using cell sorting or drug resistance-based in vitro positive selection can produce a purified population. However, these approaches are unlikely to be applicable to development of clinical therapeutics.23,24,25,26,27

We previously described a physiologically relevant, cell-intrinsic selection strategy that takes advantage of the crucial role of interleukin-2 (IL-2) in expansion and survival of Treg cells.29 This approach utilizes the transmembrane and intracellular signaling domains of the IL-2 receptor, γ and β subunits, fused with extracellular rapamycin binding domains, FKBP and FRB, respectively, to form a chemically inducible signaling complex (CISC). In response to rapamycin, CISC-expressing CD4+ T cells or Treg cells were enriched and showed increased expansion and survival in vitro in the absence of IL-2.29 Importantly, cell-intrinsic signaling via CISC engagement also facilitates in vivo engraftment and survival of CISC-expressing EngTreg cells, addressing a key in vivo challenge, competition for IL-2 support, which occurs following adoptive Treg cell therapy.

Notably, the heterodimeric nature of the CISC suggested that delivery of these signaling elements “split” across two independent HDR events would permit selective expansion of biallelic, or dual-locus, dual-HDR edited cells in vitro. Testing this concept, in the present study, we describe a dual-HDR editing strategy based on co-delivery of CRISPR and AAV donor cassettes containing Split-CISC elements. This approach allowed combining FOXP3 editing with targeted insertion of an islet ag-specific TCR into the TRAC locus and subsequent in vitro selection, leading to generation of highly enriched populations of functionally active, ag-specific EngTreg cells.

Results

Application of IL-2 CISC to generate selectable dual-HDR-edited T cells

To establish a robust, clinically relevant gene editing strategy to generate enriched, ag-specific, CISC-expressing EngTreg cells, we first tested a series of HDR dual editing strategies based on co-delivery of AAV donor templates bearing the two Split-CISC elements.

To initially test the concept that separate delivery of the CISC components could permit expansion of dual-HDR-edited cells, alternative recombinant (r)AAV6 HDR donor cassettes were designed to target the first exon of the TRAC locus (Figure 1A). The donor cassettes have matched 5' and 3' 0.3-kb homology arms complementary to the directed nuclease cut site of our previously described TRAC-targeting single guide RNA (sgRNA), refered to as TRACg1.29 The internal expression cassettes contain a constitutively active, γ-retrovirus derived MND promoter30 to express the Split-CISC element, FRB-IL-2RB (CISCb) or FKBP-IL-2RG (CISCg), in association with a cis-linked fluorescent protein marker, GFP or mCherry, respectively. Previously, we have shown that cytosolic expression of an FRB domain (lacking an endoplasmic reticulum (ER)-targeting signal sequence, referred to hereafter as the decoy [d]FRB domain) can compete with mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) for intracellular rapamycin engagement, limiting cell-intrinsic, rapamycin-mediated inhibition of CISC-expressing T cells containing this element.29 Based on these previous findings, we incorporated dFRB into one of the HDR donor constructs. Because the dFRB is an independent element, it can be expressed in tandem with either Split-CISC domain. In this experiment, dFRB was included in the cassette delivering CISCg and mCherry using an in-frame 2A ribosome-skip peptide to separate the protein-coding sequences. The relevant AAV vectors are referred to as AAV TRAC[MND.GFP.Split-CISCb] and TRAC[MND.mCherry.Split-CISCg.dFRB], respectively (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

Biallelic dual-HDR editing at the TRAC locus using Split-CISC cassettes allows selective enrichment and expansion of dual-edited cells

(A) Schematic showing the TRAC locus and AAV donor templates designed to introduce the CISC elements via CRISPR-meditated HDR, with each donor template carrying one-half of the CISC heterodimer. Successful biallelic editing of the TRAC locus (bottom) is predicted to generate one allele (allele A) with the MND promoter driving expression of a GFP fluorophore and cis-linked Split-CISCb (FRB-IL-2RB fusion protein) and a second allele (allele B) with MND driving expression of an mCherry fluorophore and cis-linked Split-CISCg (FKBP-IL-2RG fusion protein) and dFRB. (B) Representative flow panels resulting from HDR editing of primary human CD4+ T cells using no AAV donor (mock), AAV TRAC[MND.GFP.Split-CISCb] alone (GFP edit), AAV TRAC[MND.mCherry.Split-CISCg.dFRB] alone (mCherry edit), or a 50:50 mixture of both AAV donor templates (dual edit). Numbers indicate the proportion of single- or dual-edited cells, respectively. (C) Dual-edited T Cells were expanded in the presence of 50 ng/mL IL-2, 10 nM rapamycin, 100 nM AP21967, or DMSO for 7 days. Left panel: Representative flow plots from days 0 and 7. Right panel: percentage of GFP+/mCherry+ (double-positive) cells over time (p value from two-way ANOVA). (D) Fold expansion of GFP+/mCherry+ cells cultured in rapamycin for 7 days. Data are presented as mean ± SEM for 3 technical replicates. Data shown are representative of 3 replicates.

To mediate HDR-based editing, human CD4+ T cells were electroporated to deliver Cas9 ribonucleoprotein (RNP) containing TRACg1, followed by delivery of the AAV TRAC[MND.GFP.Split-CISCb] or TRAC[MND.mCherry.Split-CISCg.dFRB] alone or co-delivery of both vectors (Figure 1A). As shown in Figure 1B, cell populations receiving a single HDR donor template generated a subpopulation of fluorophore marker-expressing cells, while delivery of both HDR donor templates resulted in a mix of 4 distinct subpopulations: double-negative, single-positive (GFP+ or mCherry+), and double-positive (GFP+/mCherry+) cells, with the latter presumably representative of dual-HDR cells incorporating one copy of each template into each TRAC allele. To determine whether delivery of both Split-CISC elements led to selective expansion of the GFP+/mCherry+ subpopulation, the dual-edited cell population was cultured in 10 nM rapamycin, 100 nM AP21967 (a heterodimerizing rapamycin analog that does not engage mTOR), 50 ng/mL IL-2, or no cytokine beginning 3 days post editing. After 7 days under these conditions, the subpopulation of GFP+/mCherry+ cells in rapamycin or AP21967 enriched to greater than 90%, while GFP+/mCherry+ cells in IL-2 or no-cytokine medium showed no change in relative abundance (Figure 1C). Consistent with specific, numerical expansion of dual-HDR-edited cells, the GFP+/mCherry+ subset showed an average 15-fold expansion from rapamycin enrichment day 0 to day 7, representative of 3 technical replicates from a single donor product (Figure 1D). Together, these data demonstrate that the IL-2 Split-CISC is capable of enriching for dual-HDR-edited T cells when the FKBP-IL-2RG and FRB-IL-2RB signaling chains are introduced following simultaneous independent HDR targeting of the TRAC locus.

Alternative promoter strategies to achieve threshold CISC expression

Strategies to disrupt endogenous TCR expression through targeted insertion of promoterless expression cassettes in frame at the TRAC locus have been used to express constructs under control of the TCRα promoter.15,16,18 To evaluate the feasibility of using this TRAC promoter capture strategy with our single-locus dual-HDR engineering approach, we designed promoterless HDR templates to introduce the Split-CISC components cis-linked to GFP or mCherry downstream of a P2A element (Figure S1A). These donor constructs (referred to as AAV TRAC[2A.GFP.Split-CISCg] or AAV TRAC[2A.mCherry.Split-CISCb], respectively) were designed to integrate in frame in TRAC coding exon 1 proximal to the ATG start codon, with 0.3 kb 5′ and 3′ homology arms flanking the nuclease cut site issued by an alternative, novel TRAC-targeting sgRNA, TRACg2. Dual-HDR editing using these templates was anticipated to generate T cells with each Split-CISC element driven off the endogenous TRAC promoter. Dual editing resulted in co-expression of GFP and mCherry at percentages similar to that in Figure 1B using MND promoter-driven AAV donors. However, when cultured in 100 nM AP21967 (used for enrichment in place of rapamycin as these donor constructs lacked the dFRB expression ), dual-edited GFP+/mCherry+ cells engineered with the promoter capture strategy failed to progressively enrich (Figures S1B and S1C). A closer examination of dual-edited cells with TRAC integration of Split-CISC fluorophore cassettes driven by the MND promoter versus endogenous TRAC promoter revealed a markedly higher mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of the cis-linked fluorophores with the MND promoter (Figure S1D).

These results suggested that CISC-based T cell enrichment may require a threshold level of FKBP-IL-2RG/FRB-IL-2RB expression. Alternatively, the constitutively active elongation factor 1 alpha (EF1α) promoter has been used to drive exogenous TCR expression when integrated into the TRAC locus, resulting in higher levels and more stable expression of the exogenous TCR compared with the promoter capture strategy.20 To examine differential promoter strength in the context of CISC enrichment, we utilized an LV vector containing an EF1α core promoter sequence to drive expression of all CISC elements linked to an mCherry reporter (Figure S2A). Following LV transduction, EF1α-driven, cis-linked fluorophore expression was present, but no enrichment of mCherry+ cells was observed in cells cultured in the presence of AP21967 (Figures S2B and S2C). Compared with T cells transduced with an identical LV cassette utilizing the MND promoter,29 higher mCherry MFI was observed with MND relative to EF1α (Figure S2D). Together, these observations further suggest that a threshold of CISC expression, as achieved with the MND promoter, is required for Split-CISC-mediated in vitro T cell enrichment.

Design of a dual-locus, dual-HDR editing strategy targeting TRAC and FOXP3

The results above show that single-locus, dual-HDR editing allows Split-CISC mediated cell enrichment. However, generation of a CISC-selectable, ag-specific EngTreg cell requires the ability to target two separate loci. To evaluate the Split-CISC in this context, an mCherry-linked CISCg HDR template targeting the FOXP3 locus was designed (AAV FOXP3[MND.mCherry.Split-CISCg]) and paired with AAV TRAC[MND.GFP.Split-CISCb] for co-delivery (Figure S3A). Human CD4+ T cells were electroporated with a mixed RNP complex containing TRACg1 and a previously validated FOXP3 sgRNA targeted downstream of the Treg cell-specific demethylated region, within the first coding exon,3 followed by concurrent delivery of AAV TRAC[MND.GFP.Split-CISCb] and AAV FOXP3[MND.mCherry.Split-CISCg] repair templates. Similar to our observations using single-locus dual-HDR, dual-locus dual-HDR produced a mix of 4 subpopulations: double-negative, single-positive (GFP+ or mCherry+), and double-positive (GFP+/mCherry+) cells (Figures S3B and S3C). Culture with 100 nM AP21967 resulted in progressive enrichment of Split-CISC GFP+/mCherry+ cells compared with cells cultured in 50 ng/mL IL-2. These findings demonstrate the capacity to achieve targeted insertion of Split-CISC into two different loci and to select for cells having undergone successful dual-HDR.

Generation of dual-locus, dual-HDR-edited, islet ag-specific EngTreg cells

Based on this strategy, we next designed a Split-CISC dual-locus, dual-HDR editing strategy with MND-driven cassettes designed to generate CISC-expressing, islet ag-specific EngTreg cells. As proof of concept, we utilized the T1D4 TCR. This clinically relevant TCR was isolated from Teff cells derived from a patient with T1D and recognizes the human islet ag islet-specific glucose-6-phosphatase-related protein (IGRP)-derived peptide (amino acids 241–260; IGRP241–260) in the context of HLA-DRB1∗04:01.31 In our previous work, LV delivery of this TCR utilized a construct that included the human α and β variable regions fused to the respective murine constant regions to promote pairing of the exogenous TCR chains.4 In the present study, we sought to generate fully humanized, ag-specific EngTreg cells with potential for clinical application. Thus, the murine TCR constant regions were replaced with the human constant region coding sequences. Because this raises concern regarding potential mispairing between the T1D4 TCR α and β chains with endogenous TCR sequences,32 we first evaluated CRISPR-mediated TRAC knockout (KO) in cells transduced with LV to deliver the fully human T1D4 TCR. Compared with mock KO cells transduced with the human T1D4 TCR, TRAC KO significantly increased TCR surface expression based on tetramer staining with the cognate ag IGRP241–260 (Figure S4). Disrupting the TRAC locus as part of our dual-locus, dual-HDR strategy decreases competition for pairing of the integrated TCR α and β chains, facilitating increased surface expression of the specific T1D4 TCR, while reducing the potential for irrelevant and/or off-target TCR expression.33,34

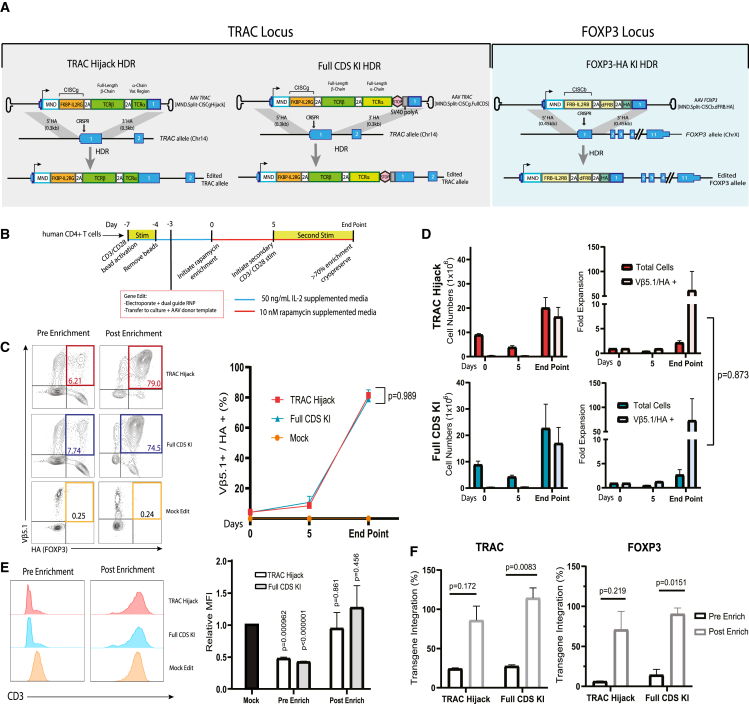

To manufacture CISC-expressing, T1D4 TCR ag-specific EngTreg cells, two alternative TRAC targeting cassettes delivering CISCg and the T1D4 TCR were generated (Figure 2A). (1) Donor AAV TRAC[MND.Split-CISCg.Hijack] included the full-length T1D4 β chain and the variable region of the T1D4 α chain separated by the 2A element and constructed with homology arms matched to TRACg2. Following in-frame HDR within the first coding exon of TRAC, this construct was designed to “hijack” the endogenous α constant region to form the full-length α chain. Importantly, via capture of these endogenous sequences, this approach permitted utilization of smaller HDR donor templates predicted to improve HDR editing efficiency. (B) The second vector, referred to as AAV TRAC[MND.Split-CISCg.FullCDS], with homology arms matched to TRACg1, also targets a downstream site in the first exon of TRAC but instead introduces CISCg, the full-length TCR β chain, and α chains separated by 2A peptides followed by a stop codon and SV40 poly(A) signal to terminate transcription, leading to expression of full-length exogenous T1D4 coding sequences. This strategy was designed as a proof-of-concept platform translatable for insertion of alternative targeting moieties not compatible with the TRAC hijack approach. Both TRAC donors were designed to knock out endogenous TCR expression and were paired with a FOXP3-targeting rAAV donor template3 to include CISCb, the dFRB domain, and a hemagglutinin (HA) epitope tag in frame with FOXP3 (Figure 2A). These coding elements were separated by 2A sequences to generate AAV FOXP3[MND.Split-CISCb.dFRB.HA].

Figure 2.

Dual-locus, dual-HDR editing generates islet-specific EngTreg cells that can be enriched in vitro to high purity

(A) Schematic showing editing strategies and anticipated outcomes following HDR. Left and center, gray panels: alternative strategies for TRAC locus editing using CRISPR targeting exon 1 and AAV donor templates designed to introduce the MND promoter driving expression of Split-CISCg and cis-linked islet ag-specific TCR (T1D4). The alternative AAV donors were designed to capture downstream components of endogenous TRAC (TRAC[MND.Split-CISCg.Hijack]) or to introduce the full-length exogenous TCR (AAV TRAC[MND.Split-CISCg.FullCDS], respectively. Right, light blue panel: editing strategy at the FOXP3 locus, targeting the first coding exon using an AAV donor (FOXP3[MND.Split-CISCb.dFRB.HA]) designed to introduce the MND promoter driving expression of Split-CISCb and endogenous FOXP3 with an N-terminal HA epitope tag. (B) Schematic showing the strategy to generate islet ag-specific EngTreg cells via HDR editing of primary human CD4+ T cells, followed by enrichment of dual-edited cells. The timing of CD3/CD28 bead stimulation, culture in 50 ng/mL IL-2-supplemented medium, and culture in 10 nM rapamycin-supplemented medium are shown. Mock-edited cells were stimulated identically using CD3/CD28 and electroporated (but not exposed to nuclease or AAV) and subsequently cultured in 50 ng/mL IL-2 alone . (C) Left panels: representative flow plots showing Vβ5.1/HA staining of TRAC Hijack, Full CDS Knock in (KI) EngTreg, and mock-edited cells pre enrichment (enrichment day 0) and post rapamycin enrichment (day of cryopreservation). Right panel: graph showing the proportion of Vβ5.1+/HA+ (double-positive) cells on enrichment days 0 and 5 and on the day of cryopreservation (p value from two-way ANOVA). (D) Quantification of total cell number and Vβ5.1+/HA+ cell number (left) and relative fold expansion (right) of TRAC Hijack and Full CDS KI EngTreg cells during cell production (p value from unpaired t test). (E) Representative flow cytometry for CD3 surface expression in TRAC Hijack and Full CDS KI EngTreg cells. Left panel: pre-enrichment (3 days post editing). Right panel: post rapamycin enrichment (day of cryopreservation). Mock-edited cells are shown for comparison; the graph shows CD3 MFI pre and post rapamycin enrichment relative to mock-edited T cells (p value from multiple unpaired t tests comparing groups with mock edit MFI). (F) Droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) data quantifying on-target transgene integration at the TRAC and FOXP3 loci, respectively, pre and post enrichment. ddPCR values were normalized using a control X-chromosomal genomic locus (∼10 kb downstream of the FOXP3 target site) (p value from paired t test). Full CDS KI EngTreg cells were manufactured using 3 peripheral blood mononuclear cell (PBMC) donors, with data from all donors represented in (C–F). TRAC hijack EngTreg cells were manufactured using the same 3 PBMC donors. (C) and (D) show data from donors 1 and 2. (E) and (F) show data from donors 2 and 3. All data are presented as mean ± SEM.

As shown in Figure 2B, following 3-day CD3/CD28 bead stimulation, human CD4+ T cells isolated from 3 PBMC donors were electroporated to deliver a mixed Cas9 RNP containing the FOXP3 sgRNA and the respective TRAC sgRNA. Alternative AAV donors (AAVs FOXP3[MND.Split-CISCb.dFRB.HA] + TRAC[MND.Split-CISCg.Hijack] or FOXP3[MND.Split-CISCb.dFRB.HA] + TRAC[MND.Split-CISCg.FullCDS]) were delivered in a 50:50 cocktail upon rescue from electroporation in IL-2 medium. Enrichment in 10 nM rapamycin was initiated 3 days post editing (enrichment day 0), followed by a secondary CD3/CD28 bead stimulation 8 days post editing (enrichment day 5). Cells were maintained in culture until they achieved a greater than 70% dual-HDR enrichment level, as measured by flow cytometry analysis based on surface staining for Vβ5.1, the variable β chain of the T1D4 TCR, and intracellular staining for the HA epitope tag included in the FOXP3 editing cassette. Mock-edited cells were handled equivalently but were maintained in IL-2 culture.

Both TCR insertion strategies resulted in comparable subpopulations of Vβ5.1+/HA+ cells that progressively enriched in rapamycin with similar kinetics (Figure 2C). The Vβ5.1+/HA+ subsets in both TRAC-targeting strategies exhibited an average 60-fold expansion from the initial editing rate at the end of enrichment (Figure 2D). Enriched populations exhibited restoration of CD3, indicating surface TCR expression (Figure 2E). Molecular analysis using droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) and primers flanking the insert junction at the TRAC and FOXP3 locus, respectively, confirmed initial HDR rates and the increase in relative level of transgene integration following enrichment, although variability between donors for the TRAC hijack strategy reduced the significance of the ddPCR dataset. Because we used a single allele reference located 10 kb downstream of the integration site on the FOXP3 allele, we were able to infer that there was biallelic TCR insertion at the TRAC locus based on transgene integration rates of greater than 100% (Figure 2F). These findings demonstrate that dual-locus, dual-HDR-edited EngTreg cells can be enriched in vitro in response to CISC engagement. These cell products lack endogenous TCR expression and express the exogenous islet-specific T1D4 TCR integrated into the TRAC locus.

TRAC Hijack T1D4 EngTreg cells exhibit a Treg cell immunophenotype

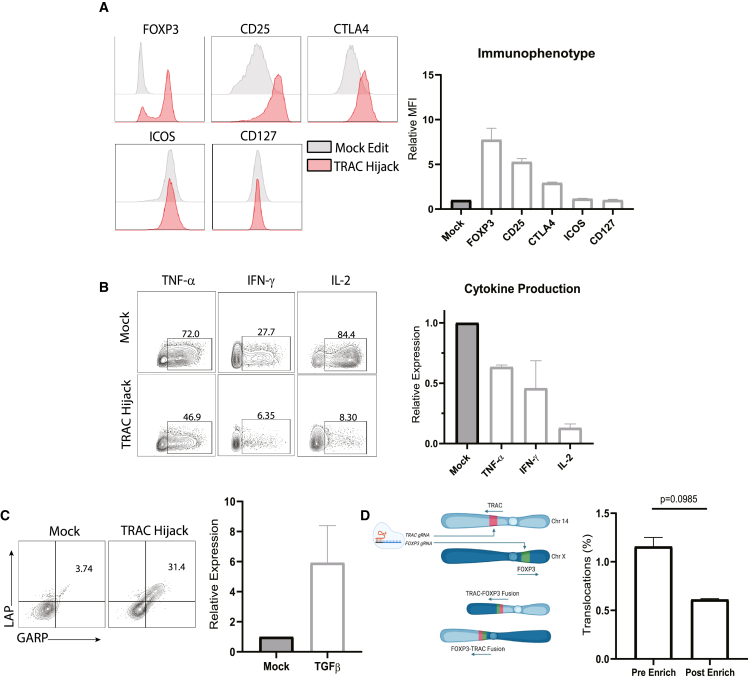

We next determined whether dual-edited cells generated using the Split-CISC strategy exhibited Treg cell properties. Enforced FOXP3 expression mediates a robust Treg cell phenotypic and immunosuppressive cytokine profile,3 and incorporation of CISC in the FOXP3 locus does not alter this phenotype.29 Because the TRAC Hijack TCR insertion strategy utilizes a smaller donor template and introduces fewer exogenous elements (for example, it lacks the α constant region and sv40 poly(A) elements), it is predicted to provide a more efficient platform for clinical applications utilizing a TCR-targeting moiety for production of an ag-specific EngTreg cell product. Therefore, using TRAC Hijack T1D4 EngTreg cells and control mock-edited T cells (derived from two independent donors), we performed flow cytometric analysis to assess key surface markers, including CD25, cytotoxic T lymphocyte associated protein (CTLA)4, inducible T cell costimulator (ICOS), and CD127, and intracellular FOXP3 expression (Figure 3A), yielding results consistent with a Treg cell surface phenotype. TRAC Hijack EngTreg cells also exhibited a Treg cell-like cytokine profile, including reduced expression of inflammatory cytokine production (tumor necrosis factor alpha [TNF-α], interferon gamma [IFN-γ], and IL-2) compared with mock-edited cells upon stimulation with phorbol myristate acetate (PMA) and ionomycin (Figure 3B). Following CD3/CD28 stimulation, TRAC Hijack EngTreg cells showed increased expression of the immunosuppressive cytokine transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β; based on co-expression of latency-associated peptide (LAP) and glycoprotein A repetitions predominant [GARP]) compared with mock-edited cells (Figure 3C).

Figure 3.

Dual-locus, dual-HDR-edited EngTreg cells exhibit a Treg cell immunophenotype and cytokine profile

Shown is characterization of TRAC Hijack EngTreg cells compared with mock-edited cells. (A) Left panel: immunophenotype of enriched TRAC Hijack EngTreg cells and mock-edited controls. Right panel: cryopreserved cells were immunophenotyped using flow cytometry for Treg cell markers following a 3-day rest post thaw. The graph shows relative MFI fold change for each indicated phenotypic marker normalized to mock-edited controls. (B) TRAC Hijack EngTreg cells were treated with Monensin to halt secretion of cytokines and stimulated with PMA/ionomycin for 5 h to assess production of the proinflammatory cytokines TNF-α, IFN-γ, and IL-2. Representative flow plots (left panel) and graphs (right panel) show relative cytokine production in EngTreg cells normalized to mock-edited controls. (C) Cryopreserved TRAC Hijack EngTreg cells were stimulated with CD3/CD28 beads for 24 h and assessed, using flow cytometry, for LAP and GARP expression to identify TGF-β cytokine production. Representative flow plots (left panel) and graph (right panel) show proportion of LAP/GARP double-positive EngTreg cells compared with mock-edited controls. (D) Left panel: schematic illustrating dual sgRNA delivery targeting TRAC and FOXP3 (on chr14 and chrX, respectively) and potential balanced chromosomal translocations leading to unicentric chromosomes. Right panel: graph comparing frequency of TRAC:FOXP3 balanced translocation measured via a ddPCR assay (using primers flanking the predicted fusion site) in gDNA extracted from EngTreg cells pre vs. post rapamycin enrichment (p value is from paired t test). For (A–D), data represent 2 biological replicates, with (D) including 3 technical replicates, and are presented as mean ± SEM.

Simultaneous delivery of sgRNAs targeting separate genomic loci has been demonstrated previously to generate chromosomal rearrangements at low frequency.22,35 Our TRAC- and FOXP3-targeting sgRNAs are predicted to potentially generate balanced translocations between chromosome 14 (chr14) and chrX that could be maintained across cell divisions. However, because cells bearing these translocations would not express the full CISC cassette, we predicted that such translocations would decline in frequency following CISC enrichment (Figure 3D). To detect TRAC:FOXP3 rearrangements, we developed a ddPCR assay to quantify the possible balanced translocation product and used a synthetic gene fragment with the predicted fusion as a positive control. Genomic DNA was extracted from TRAC Hijack EngTreg cells 3 days post editing and on the day of cryopreservation (as representative pre- and post-enrichment time points). Chromosomal translocation was detected in 1.5% of dual-edited cells before enrichment, and this fraction decreased to 0.61% post enrichment (Figure 3D, right panel), consistent with minimal persistence within the EngTreg cell product. These results validate our TRAC Hijack engineering strategy to generate ag-specific EngTreg cells with a robust Treg cell-like phenotype and cytokine profile.

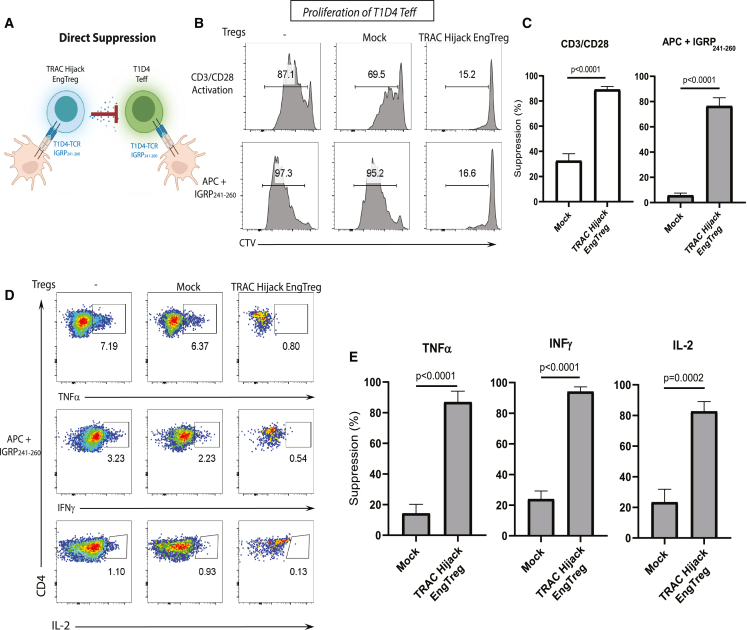

TRAC Hijack T1D4 EngTreg cells mediate direct and bystander Teff cell suppression

To directly evaluate TRAC Hijack EngTreg cell suppressive function, we first assessed their activity against autologous Teff cells expressing an identical, islet-specific TCR. To generate T1D4 Teff cells with high levels of exogenous TCR expression, human CD4+ T cells were transduced with an LV vector expressing a T1D4 TCR construct containing the human TCR-derived ag recognition domains in association with mouse TCR-derived α and β constant regions. T1D4 Teff cells were labeled with CellTrace violet (CTV) and cultured alone or co-cultured with mock-edited (polyclonal) CD4+ T cells or TRAC Hijack EngTreg cells in the presence of CD3/CD28-activating beads. Using CTV dilution as a measure of Teff cell proliferation, Teff cells co-cultured with TRAC Hijack EngTreg cells exhibited a greater than 80% reduction in proliferation compared with Teff cells cultured with mock cells (Figure 4B, top panels; Figure 4C, left panel). The mild suppressive effect of mock cells reflects competition for IL-2 following polyclonal activation. Next, to evaluate ag-specific direct suppressive activity of TRAC Hijack EngTreg cells, we cultured CTV-labeled T1D4 Teff cells alone or with mock-edited CD4+ T cells or TRAC Hijack EngTreg cells in the presence of the T1D4 cognate peptide IGRP241–260 and ag-presenting cells (APCs). TRAC Hijack EngTreg cells specifically suppressed T1D4 Teff cell proliferation following activation in the presence of cognate peptide (Figure 4B, bottom panels; Figure 4C, right panel). Mock-edited CD4+ cells (lacking the T1D4 TCR) were not activated by IGRP241–260; thus, no suppressive effect from IL-2 competition was observed.

Figure 4.

Dual-locus, dual-HDR-edited islet-specific EngTreg cells display robust on-target suppressive function

(A) Schematic of direct suppression between TRAC hijack EngTreg cells bearing the T1D4 TCR and Teff cells with matched TCR specificity to IGRP241–260 in the context of ag-specific stimulation. (B) Representative flow cytometry histograms for the in vitro suppression assay in the presences of CD3/CD28 activation beads or APCs displaying IGRP241–260. Fluorescence of the CTV-labeled Teff cells is shown for the Treg cell treatment groups indicated at the top of each column after 4 days in co-culture. (C) Graphs show the percent suppression of Teff cell proliferation in response to non-specific (CD3/CD28 activation) vs. specific TCR engagement (APC+ IGRP241–260). Percentage of suppression was calculated as ([%] Teff cell proliferation without Treg cells – [%] Teff cell proliferation with Treg cells) / ([%]) Teff proliferation without Treg cells) × 100. (D) Representative flow cytometry plots for pro-inflammatory cytokine production in T1D4 Teff cells co-cultured with different EngTreg cell populations after ag-specific stimulation. (E) Quantification of percent suppression of inflammatory cytokine production (TNF-α, IFNγ, and IL-2) by mock-edited vs. TRAC Hijack EngTreg cells. Data are presented as mean ± SEM for 2 biological replicates with 2 or 3 technical replicates for CD3/CD28 stimulation or APC stimulation and cytokine production suppression, respectively. All p values are from unpaired t tests compared with mock-edited cells.

We also evaluated the capacity of TRAC Hijack EngTreg cells to suppress T1D4 Teff cell cytokine production. T1D4 Teff cells were cultured alone or co-cultured with mock-edited CD4+ T cells or TRAC Hijack EngTreg cells in the presence of IGRP241–260 and APCs. After 4 days, production of TNF-α, IFNγ, and IL-2 was assessed using intracellular staining. Compared with mock-edited CD4+ T cells, TRAC Hijack EngTreg cells significantly suppressed ag-triggered Teff cell production of TNF-α, IFNγ, and IL-2 (Figures 4D and 4E). Together, these observations show that TRAC Hijack EngTreg cells mediate direct ag-specific suppression of Teff cells expressing an identical TCR specificity.

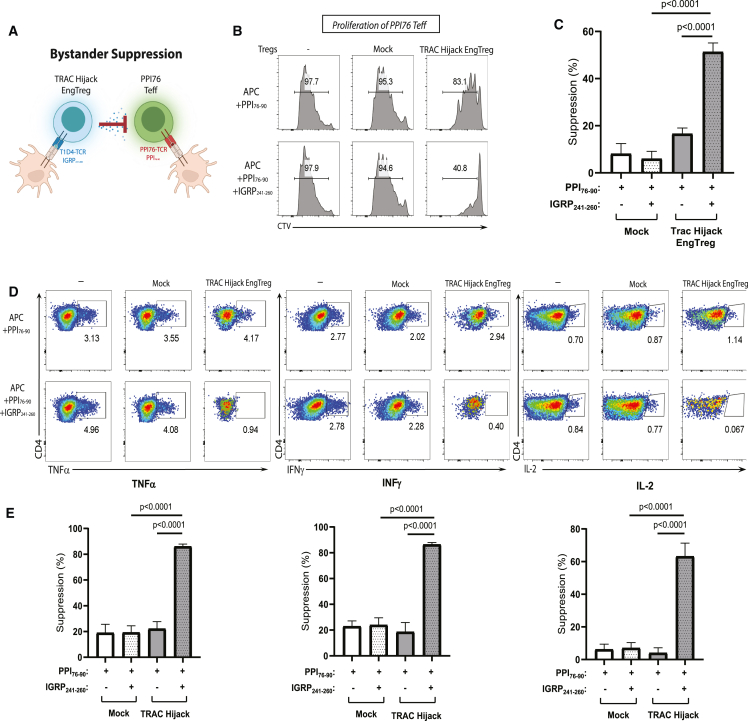

In autoimmune diseases, including T1D, autoreactive Teff cells exhibit a polyclonal TCR repertoire and target multiple self-ags. While Treg cell activation requires ag-specific TCR engagement, when activated, Treg cells exhibit the capacity to mediate bystander suppression of Teff cells bearing TCRs with distinct ag specificity in the local microenvironment (Figure 5A), a process critical for immune tolerance. To determine whether TRAC Hijack EngTreg cells can exert bystander suppression, Teff cells expressing a TCR specific for a key alternative islet ag, pre-pro insulin (PPI76–90; amino acids 76–90), were generated using LV transduction. PPI76 TCR Teff cells were labeled with CTV and cultured alone or co-cultured with mock-edited CD4+ T cells or TRAC Hijack EngTreg cells. Ag stimulation was provided by APCs with the PPI76 cognate peptide PPI76–90 or with a 50:50 mixture of PPI76–90 and IGRP241–260. In the presence of PPI76–90 with APCs alone, TRAC Hijack EngTreg cells had no impact on PPI76 Teff cell proliferation (Figure 5B, top panels; Figure 5C, left panel). In contrast, in the presence of the PPI76–90 and IGRP241–260 peptides, TRAC Hijack EngTreg cells suppressed PPI76 Teff cell proliferation (Figure 5B, bottom panels; Figure 5C, right panel). Additionally, only in the presence of PPI76–90 and IGRP241–260 did TRAC Hijack EngTreg suppress production of TNF-α, IFNγ, and IL-2 by ag-activated PPI76 Teff cells (Figures 5D and 5E). Overall, these results show that, in the presence of T1D4 cognate peptide, TRAC Hijack EngTreg cells mediate bystander suppression of Teff cells expressing a TCR with a different ag specificity. Thus, dual-HDR edited, CISC-expressing, islet ag-specific EngTreg cells exhibit critical in vitro functional properties that will be required for a potential islet-specific, EngTreg cell T1D therapy.

Figure 5.

Dual-HDR-edited islet-specific EngTreg cells display bystander suppression of Teff cells with distinct ag specificity

(A) Schematic of bystander suppression between TRAC hijack EngTreg cells bearing the T1D4 TCR and Teff cells bearing the PPI76 TCR specific to PPI76–90 in the context of ag-specific stimulation. (B) Representative flow cytometry histograms for the in vitro suppression assay after 4 days in culture. Fluorescence of the CTV-labeled Teff cells is shown for the Treg cell treatment groups indicated at the top of each column. Ag-specific stimulation conditions are indicated for each column. (C) Graphs show the percent suppression of PPI76 Teff cell proliferation. (D) Representative flow cytometry plots for pro-inflammatory cytokine production in PPI76 Teff cells co-cultured with no cells, mock-edited, or TRAC Hijack EngTreg cell populations after PPI76–90 ag-specific stimulation or mixed ag stimulation. (E) Quantification of percent suppression of inflammatory cytokine production by mock-edited and TRAC Hijack EngTreg cells. Data are presented as mean ± SD for 2 biological replicates with 3 technical replicates. All p values are from unpaired t tests compared with mock-edited cells.

Discussion

In the present study, we show that CISC can be utilized effectively as an in vitro selection tool for dual-HDR-edited T cells, allowing enrichment and expansion of ag-specific EngTreg cells. The heterodimeric nature of the CISC can be manipulated to split the FKBP-IL-2RG and FRB-IL-2RB functional protein domains, required to generate an IL-2 like signal, across two independent editing events targeting either both alleles at one locus or two separate loci. Upon in vitro treatment with rapamycin and withdrawal of IL-2, dual-HDR-edited cells containing both Split-CISC elements are enriched to generate a purified population. We implemented the Split-CISC strategy to generate ag-specific EngTreg cells, where Split-CISC elements were included in two alternative functional cassettes. From a starting population of bulk CD4+ cells, we targeted the FOXP3 locus to deliver a constitutively active promoter to drive stable FOXP3 expression to enforce an immunosuppressive Treg cell profile. Simultaneously, we targeted TRAC to replace the endogenous TCR with a T1D disease-relevant TCR, T1D4, specific to the islet ag IGRP (IGRP241–260). TRAC Hijack EngTreg cells displayed a Treg cell phenotype, suppressed Teff cells targeting the cognate ag, and mediated bystander suppression of Teff cells expressing a TCR with an unrelated ag specificity. This single-step, multiplexed genome editing strategy provides a robust platform to generate highly purified, ag-specific EngTreg cells for a broad range of potential autoimmune and autoinflammatory disorders.

Multiplexed HDR-based gene editing to deliver donor templates to single or multiple loci has recently been explored in the context of cell therapy. For example, TCR replacement at TRAC in association with knockin of a non-polymorphic MHC class I complex (HLA-E) within B2M was used to generate an allogeneic CAR-T cell product.21,22,23 However, a major predicted drawback of multiplexed HDR is the low initial frequency of dual-positive cells. For therapeutic cell products, selection strategies to enrich for cells bearing multiple HDR edits are an important consideration. Split-CISC provides an effective, cell-intrinsic in vitro selection strategy to achieve this goal via dual enrichment of independent HDR editing events with rapamycin or AP21967. Further, Split-CISC has unique advantages in the context of Treg cell engineering because these cells are highly sensitive to IL-2 withdrawal and incapable of generating autocrine IL-2. Importantly, we previously observed that full-CISC-expressing EngTreg cells exhibit improved in vivo engraftment and retention in the setting of systemic subtherapeutic rapamycin administration.29 While beyond the scope of the current study, ag-specific, dual-edited EngTreg cells expressing a Split-CISC are expected to share this key in vivo advantage, facilitating engraftment, trafficking to, and survival in target tissues where endogenous IL-2 is predicted to be limited. Well-established clinical experience with rapamycin36 and demonstration that subtherapeutic rapamycin doses mediate CISC-dependent signals37 provide a strong rationale for potential combined use of rapamycin and Split-CISC ag-specific EngTreg cells in future T cell therapies.

Combination of LV transduction and CRISPR editing has become an important focus in development of next-generation autologous T cell therapies. In the case of Teff cells engineered to express an ag-specific TCR or CAR, exogenous targeting moieties are typically delivered via LV transduction.38 In the context of defined TCR insertion, an advantage of endogenous TCR deletion is reduction of mispairing between the α and β chains of the endogenous and exogenous receptors. Mispairing reduces exogenous TCR expression and may also generate novel TCR specificities with off-target activities.11,33,39 Early trials of T cell products modified by CRISPR KO of TRAC, TRBC, and PD-1 and LV transduction of the NY-ESO-1 TCR have demonstrated safety and efficacy, implying that multiplexed CRISPR gene-edited T cells are feasible for translation into the clinic.8 In previous work, we addressed TCR mispairing of an LV-delivered islet TCR by fusing the islet ag targeting variable regions to murine α and β constant regions to ensure pairing and surface expression. In the present study, we pare this engineering approach down to a single manipulation step utilizing the fully humanized cassette to express the T1D4 TCR, as would be necessary for clinical application, from the TRAC locus. Tetramer staining revealed improved surface expression of the human T1D4 TCR upon TRAC KO (Figure S4), suggesting that the issue of mispairing was largely eliminated by our engineering strategy.

The ability to simultaneously deliver new information to genetic loci on different chromosomes presents itself as an efficient, single-step manufacturing strategy. However, this approach has potential limitations and significant points of concern in a cell-based therapy associated with dual-guide delivery resulting in NHEJ-mediated chromosomal rearrangements and their potential to generate driver oncogenes.35,40 While only limited data are available to date, dual targeting of TRAC and an alternative genomic site(s) has not resulted in a proliferative advantage for engineered cells.41,42 With our strategy, cells undergoing chromosomal translocations between TRAC and FOXP3 are unlikely to contain both Split-CISC elements and thus are unlikely to enrich with rapamycin, providing an additional safety measure against persistence of translocation events. Of note, our present study examined only predicted rearrangements resulting from on-target activity of FOXP3 and TRAC sgRNAs and did not examine potential rearrangements resulting from off-target activity. While the sgRNAs used in the present study are predicted to have high on-target specificity, a non-biased, genome-wide off-target analysis and subsequent examination of potential chromosomal rearrangements resulting from off-target activity will be important considerations for future study.

In summary, we describe a single-step engineering strategy capable of producing enriched ag-specific EngTreg cells bearing an inducible synthetic IL-2 receptor to create an effective way to promote survival and expansion of the dual-edited population. While the CISC is currently limited to use with T cells or other IL-2 cytokine family-dependent cell types, similar approaches could be developed using alternative cytokine pathways integral to survival and proliferation in a desired cell lineage. This editing and enrichment platform has potential for use with alternative TCRs, CARs, or other tissue-targeting moieties designed to modulate tissue-specific autoimmune or autoinflammatory disorders and sets the stage for further development toward clinical manufacturing.

Materials and methods

Study design

The objective of this study was to optimize a dual-HDR-based gene editing strategy to simultaneously generate islet ag-specific EngTreg cells and express a CISC to allow selective expansion of the dual-HDR edited cells. Alternate donor DNA template designs were iteratively tested for editing expression cassettes of the Split-CISC protein domains, ag-specific TCRs, and FOXP3 into specific loci of TRAC and/or FOXP3. Well-characterized intracellular and surface Treg cell markers and the immunosuppressive cytokine profile of Treg cells were assessed by flow cytometry. The ability of dual-HDR ag-specific EngTreg cells to suppress proliferation and cytokine production of Teff cells with matched or unmatched TCR specificity was assessed. Figure legends list the sample size, number of biological replicates, number of independent experiments, and statistical method.

Plasmid constructs

rAAV6 and pRRL LV vector plasmids were cloned using NEBuilder HiFi DNA Assembly Master Mix (New England Biolabs). pAAV TRAC[MND.GFP.Split-CISCb], TRAC[MND.mCherry.Split-CISCg.dFRB], TRAC[MND.Split-CISCg.FullCDS] create an insertion within the Cas9 nuclease cut site from TRACg129 disrupting exon 1 of TRAC and contain a 0.3-kb 5′ homology arm (chr14: 22,547,272-22,547,577) and a 0.3-kb 3′ homology arm (chr14: 22,547,578- 22,547,891). pAAV TRAC[MND.Split-CISCg.Hijack], TRAC[2A.GFP.Split-CISCg], and TRAC[2A.mCherry.Split-CISCb] create an insertion within the Cas9 nuclease cut site from TRACg2 in-frame with exon 1 of TRAC and contain 0.3-kb 5ʹ (chr14: 22547228–22547527) and 3′ homology arms (chr14: 22547530–22547827). pAAV FOXP3[MND.Split-CISCb.dFRB.HA] and FOXP3[MND.mCherry.Split-CISCg] create an insertion within the Cas9 nuclease cut site from FOXP3g14 downstream of the Treg cell-specific demethylated region of FOXP3 and contain 0.45-kb 5ʹ (chrX: 49258447–49258898) and 3ʹ (chrX: 49257993–49258445)3,4,29 or 0.3-kb 5ʹ (chrX: 49258447–49258742) and 3′ (chrX: 49258143–49258442) homology arms, respectively. All plasmids consisting of Split-CISC elements are codon-optimized fusions of FRB with human IL-2RB (CISCb) or FKBP with human IL-2RG (CISCg). The full coding sequence and TRAC hijacking TCR insertion AAV donor templates insert the full-length TCR β chain and either the full-length TCR α chain or the TCR α variable region, respectively, of the HLADRB1:04∗01 restricted T1D4 TCR with specificity to IGRP241–260. The pRRL lentiviral constructs were generated with T1D4 and PPI76 donor templates to insert the full-length TCRs with human or murine α and β constant regions, LV[MND.hT1D4TCR], LV[MND.mT1D4TCR], and LV[MND.mPPI76TCR], respectively, and to insert an mCherry fluorophore cis-linked to the full CISC coding sequence driven by an MND or EF1α core promoter, LV[MND.Full-CISC.mCherry]29 and LV[EF1α.Full-CISC.mCherry]. All inserted cassettes were sequenced to confirm correct amplification and fusion and contain a woodchuck hepatitus virus regulatory element (WPRE).

Viral vector production

Recombinant AAVs were generated and33 titered using the triple transfection method and serotype 6 helper plasmid described previously.43 Vesicular stomatitis virus G protein (VSV-G) pseudotyped lentiviruses were generated as described previously.44 Recombinant viral titers were calculated by ddPCR using inverted terminal repeat (ITR)-specific (AAV) or WPRE-specific (LV) primers.

Primary human T cell culture, editing, and expansion and AAV or LV transduction

Human PBMCs were purchased from Fred Hutch’s Co-operative Center for Excellence in Hematology Cell Processing Core Facility and from STEMCELL Technologies. CD4+ T cells were purified from PBMCs using the EasySep Human CD4+ T cell Enrichment Kit (STEMCELL Technologies) and then either frozen or cultured for editing. T cells were cultured in T cell medium (RPMI 1640 with 20% fetal bovine serum, 10 mM HEPES, 2 mM Glutamax, and 55 μM β-mercaptoethanol) supplemented with the human cytokine IL-2 (50 ng/mL). T cells were activated in culture using human T-Expander CD3/CD28 Dynabeads (Gibco) for 3 days according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Subsequent LV transduction at MOIs ranging from 5–40 vg/cell were performed 24 h after initiation of CD3/CD28 bead activation. Gene editing was performed 24 h after the end of CD3/CD28 bead activation, using electroporation to deliver spCas9 RNP (80 pM Cas9:200 pM sgRNA), followed by AAV transduction using an MOI of ∼40,000 vg/cell immediately upon recovery at a cell density of 2 × 106 cells/mL, as described previously.3 For dual editing, RNP was generated using 100 pM of each sgRNA, and AAV transduction used a mix of each AAV6 virus at an MOI of ∼20,000 vg/cell. Cell density was adjusted to 1 × 106 cells 24 h post transduction.3 sgRNA sequences utilized in CRISPR-Cas9 editing were as follows: FOXP3, 5ʹ-UCCAGCUGGGCGAGGCUCCU-3ʹ ; TRACg1, 5ʹ-GAGAAUCAAAAUCGGUGAAU-3ʹ; TRACg2, 5ʹ-UCUCUCAGCUGGUACACGGC-3ʹ.

For dual-HDR cell expansion, cells were recovered post editing in T cell medium supplemented with 50 ng/mL human IL-2 for 3 days, then maintained in T cell medium supplemented with 10 nM rapamycin (Sigma-Aldrich) or 100 nM AP21967 heterodimerizer (in lieu of IL-2) for 5 days. Mock-edited cells were cultured in 50 ng/mL human IL-2-supplemented T cell medium for 5 days. Dual-HDR ag-specific EngTreg cell products were then reactivated using CD3/CD28 Dynabeads, and culture was continued until enrichment of dual-HDR cells reached 70% or until enrichment day 18. T cell medium supplemented with rapamycin or IL-2 was replenished every 48 h when used.

ddPCR assays

Genomic DNA was extracted from cells 3 days post editing and following enrichment on the day of cryopreservation using the Dneasy Blood and Tissue Kit (QIAGEN) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Primer pairs and FAM-labeled probes were designed to specifically amplify and detect the desired transgene insertions in the TRAC and FOXP3 loci by flanking the transgene integration site into the endogenous genome. An additional primer pair and FAM-labeled probe was designed to flank the predicted TRAC:FOXP3 chromosomal translocation fusion site. As an endogenous genomic reference, a primer pair and HEX-labeled probe was designed, specific to the FOXP3 locus, approximately 10 kb downstream of the transgene insertion site. Each reaction contained 50 ng gDNA in ddPCR Supermix for Probes (no dUTP) (Bio-Rad). Reactions were performed in triplicate using a QX200 Droplet Digital PCR System (Bio-Rad). To determine the rate of on-target transgene integration, the ratio of FAM-positive to HEX-positive events was multiplied by 100. Frequency of translocation events was determined as the ratio of positive FAM events per positive HEX events multiplied by 100. Data analysis was performed with QuantaSoft v.1.7.11 (Bio-Rad).

Immunophenotyping assay

Mock-edited and TRAC Hijack EngTreg cells were thawed and rested in 20% fetal bovine serum (FBS)-RPMI 1640 T cell medium supplemented with IL-2 (5 ng/mL) for 3 days, followed by staining for flow analysis. To gate out non-viable cells, live/dead fixable near-IR dead cell stain (Invitrogen) was included with cell-surface staining for CD4 (BD Biosciences), CD25 (BD Biosciences), CD127 (BD Biosciences) ICOS (BioLegend), and CTLA-4 (BioLegend). Cells were fixed and permeabilized using the True-Nuclear transcription factor buffer set (BioLegend), followed by intracellular staining with an antibody for FOXP3 (BioLegend).

Cytokine production assay

Mock and TRAC Hijack EngTreg cells were thawed and rested in 20% FBS-RPMI 1640 T cell medium with IL-2 (5 ng/mL) for 3 days, followed by addition of Golgi-stop (Monensin), PMA (50 ng/mL), and ionomycin (1 μg/mL), and incubated at 37°C for 5 h. Cells were processed for flow cytometry analysis using the BD Cytofix/Cytoperm Kit and stained for live/dead, CD4, and IL-2 (Life Technologies)l IFN-γ (BioLegend); and TNF-α (Life Technologies). For TGF-β, cells were stimulated with CD3/CD28 T-expandr Dynabeads (Gibco) at 37°C for 24 h and stained for surface expression of LAP (BioLegend) and GARP (BD Bioscience).

In vitro immunosuppression assays

Human PBMCs were obtained from the Benaroya Research Institute (BRI) Registry and Repository and approved by BRI’s institutional review board (IRB #07109-588). Healthy control subjects had no personal or family history of autoimmune disease. Healthy control subjects were HLA-DRB1∗0401. CD4+ Teff cells were isolated from frozen PBMCs, cultured in T cell medium supplemented with 50 ng/mL IL-2, and activated with CD3/CD28 beads for 3 days. Cells were then transduced with a lentivirus to deliver a modified murine constant region TCR expression cassette with ag specificity to human IGRP241–260 or PPI76–90 and then cryopreserved. Upon thawing, CD4+ Teff cells were rested for 1.5 h in T cell medium at 37°C and stained with CTV (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Autologous mock or TRAC Hijack EngTreg cells were also thawed and rested alongside responder cells and stained with eFluor 670 cell proliferation dye (eBioscience). For in vitro suppression assays using CD3/CD28 T-activator Dynabeads (Gibco), 2 × 104 Teff cells were cultured alone or co-cultured with TRAC Hijack EngTreg cells or autologous mock cells at a 1:1 ratio in the presence of CD3/CD28 activator beads at a 1:30 bead:Teff cell ratio. For the ag-specific suppression assays using ag-specific peptides, 2 × 104 Teff were co-cultured with TRAC Hijack EngTreg or mock cells in the presence of 1 × 105 APCs (autologous PBMCs irradiated at 5,000 rad) and relevant peptide(s). Teff cell proliferation, as determined by CTV dilution, was measured after 4 days of co-culture with EngTreg cells at 37°C. Percent suppression was calculated as (a-b)/a × 100, where a is the percentage of Teff cell proliferation in the absence of suppressor cells, and b is the percentage of Teff cell proliferation in the presence of suppressor cells. For assays measuring suppression of intracellular cytokine production by Teff cells, cells were cultured for 3 days and incubated with Brefeldin A (BioLegend) for another 4 h, followed by intracellular cytokine staining with the Cytofix/Cytofirm Kit (BD Biosciences) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Percent suppression was calculated similarly as percent suppression of Teff cell proliferation, but the percentage of cytokine production was used instead of the percentage of Teff cell proliferation.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jennifer Haddock for assistance with editing the manuscript and Dr. Laura Smith for effective coordination of studies. We thank the investigators and staff of the BRI Translational Research Core and BRI Diabetes Research Program for recruitment of subjects with T1D, and Karen Cerosaletti for input on pancreatic islet-specific TCR selection. We also thank the members of the Rawlings laboratory for helpful discussions and support. This work was supported by grants from the Leona M. and Harry B. Helmsley Charitable Trust and GentiBio, Inc. (to D.J.R.), the Seattle Children's Research Institute (SCRI) Program for Cell and Gene Therapy (PCGT), the Children’s Guild Association Endowed Chair in Pediatric Immunology (to D.J.R.), and the Hansen Investigator in Pediatric Innovation Endowment (to D.J.R.).

Author contributions

D.J.R., J.B., P.J.C., and M.S.H. conceptualized and designed the study. M.S.H, A.B., and P.J.C. generated and tested Split-CISC HDR templates in human CD4+ T cells. M.S.H and P.J.C. generated and characterized human dual-edited T1D4+ EngTreg cells in vitro. S.J.Y. and E.M. performed in vitro on-target and bystander suppression assays. M.S.H., P.J.C., and D.J.R. wrote the manuscript with assistance from additional co-authors. D.J.R. obtained funding and was responsible for the project.

Declaration of interests

D.J.R. is a scientific co-founder and scientific advisory board (SAB) member of GentiBio, Inc. and scientific co-Founder and SAB member of BeBiopharma, Inc. D.J.R. received past and current funding from GentiBio, Inc. for related work. J.B. is a scientific co-founder and SAB member of GentiBio, Inc. J.B. received past and current funding from GentiBio, Inc. for related work. D.J.R., P.J.C., and J.B. are inventors on patents describing methods for generating ag-specific engineered regulatory T cells and/or use of the CISC platform.

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymthe.2023.07.016.

Contributor Information

Peter J. Cook, Email: peter.cook@seattlechildrens.org.

David J. Rawlings, Email: drawling@uw.edu.

Supplemental information

Data and code availability

Data supporting the findings of the present study are available upon request from the corresponding authors.

References

- 1.Raffin C., Vo L.T., Bluestone J.A. Treg cell-based therapies: challenges and perspectives. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2020;20:158–172. doi: 10.1038/s41577-019-0232-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferreira L.M.R., Muller Y.D., Bluestone J.A., Tang Q. Next-generation regulatory T cell therapy. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2019;18:749–769. doi: 10.1038/s41573-019-0041-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Honaker Y., Hubbard N., Xiang Y., Fisher L., Hagin D., Sommer K., Song Y., Yang S.J., Lopez C., Tappen T., et al. Gene editing to induce FOXP3 expression in human CD4(+) T cells leads to a stable regulatory phenotype and function. Sci. Transl. Med. 2020;12 doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aay6422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yang S.J., Singh A.K., Drow T., Tappen T., Honaker Y., Barahmand-Pour-Whitman F., Linsley P.S., Cerosaletti K., Mauk K., Xiang Y., et al. Pancreatic islet-specific engineered T(regs) exhibit robust antigen-specific and bystander immune suppression in type 1 diabetes models. Sci. Transl. Med. 2022;14 doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.abn1716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fraietta J.A., Nobles C.L., Sammons M.A., Lundh S., Carty S.A., Reich T.J., Cogdill A.P., Morrissette J.J.D., DeNizio J.E., Reddy S., et al. Disruption of TET2 promotes the therapeutic efficacy of CD19-targeted T cells. Nature. 2018;558:307–312. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0178-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nobles C.L., Sherrill-Mix S., Everett J.K., Reddy S., Fraietta J.A., Porter D.L., Frey N., Gill S.I., Grupp S.A., Maude S.L., et al. CD19-targeting CAR T cell immunotherapy outcomes correlate with genomic modification by vector integration. J. Clin. Invest. 2020;130:673–685. doi: 10.1172/JCI130144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ren J., Liu X., Fang C., Jiang S., June C.H., Zhao Y. Multiplex Genome Editing to Generate Universal CAR T Cells Resistant to PD1 Inhibition. Clin. Cancer Res. 2017;23:2255–2266. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-1300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stadtmauer E.A., Fraietta J.A., Davis M.M., Cohen A.D., Weber K.L., Lancaster E., Mangan P.A., Kulikovskaya I., Gupta M., Chen F., et al. CRISPR-engineered T cells in patients with refractory cancer. Science. 2020;367 doi: 10.1126/science.aba7365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Legut M., Dolton G., Mian A.A., Ottmann O.G., Sewell A.K. CRISPR-mediated TCR replacement generates superior anticancer transgenic T cells. Blood. 2018;131:311–322. doi: 10.1182/blood-2017-05-787598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wiebking V., Lee C.M., Mostrel N., Lahiri P., Bak R., Bao G., Roncarolo M.G., Bertaina A., Porteus M.H. Genome editing of donor-derived T-cells to generate allogenic chimeric antigen receptor-modified T cells: Optimizing alphabeta T cell-depleted haploidentical hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Haematologica. 2021;106:847–858. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2019.233882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schober K., Müller T.R., Gökmen F., Grassmann S., Effenberger M., Poltorak M., Stemberger C., Schumann K., Roth T.L., Marson A., Busch D.H. Orthotopic replacement of T-cell receptor alpha- and beta-chains with preservation of near-physiological T-cell function. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2019;3:974–984. doi: 10.1038/s41551-019-0409-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sachdeva M., Busser B.W., Temburni S., Jahangiri B., Gautron A.S., Maréchal A., Juillerat A., Williams A., Depil S., Duchateau P., et al. Repurposing endogenous immune pathways to tailor and control chimeric antigen receptor T cell functionality. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:5100. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-13088-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roth T.L., Puig-Saus C., Yu R., Shifrut E., Carnevale J., Li P.J., Hiatt J., Saco J., Krystofinski P., Li H., et al. Reprogramming human T cell function and specificity with non-viral genome targeting. Nature. 2018;559:405–409. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0326-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Müller T.R., Jarosch S., Hammel M., Leube J., Grassmann S., Bernard B., Effenberger M., Andrä I., Chaudhry M.Z., Käuferle T., et al. Targeted T cell receptor gene editing provides predictable T cell product function for immunotherapy. Cell Rep. Med. 2021;2 doi: 10.1016/j.xcrm.2021.100374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.MacLeod D.T., Antony J., Martin A.J., Moser R.J., Hekele A., Wetzel K.J., Brown A.E., Triggiano M.A., Hux J.A., Pham C.D., et al. Integration of a CD19 CAR into the TCR Alpha Chain Locus Streamlines Production of Allogeneic Gene-Edited CAR T Cells. Mol. Ther. 2017;25:949–961. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2017.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kath J., Du W., Pruene A., Braun T., Thommandru B., Turk R., Sturgeon M.L., Kurgan G.L., Amini L., Stein M., et al. Pharmacological interventions enhance virus-free generation of TRAC-replaced CAR T cells. Mol. Ther. Methods Clin. Dev. 2022;25:311–330. doi: 10.1016/j.omtm.2022.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Feucht J., Sun J., Eyquem J., Ho Y.J., Zhao Z., Leibold J., Dobrin A., Cabriolu A., Hamieh M., Sadelain M. Calibration of CAR activation potential directs alternative T cell fates and therapeutic potency. Nat. Med. 2019;25:82–88. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0290-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eyquem J., Mansilla-Soto J., Giavridis T., van der Stegen S.J.C., Hamieh M., Cunanan K.M., Odak A., Gönen M., Sadelain M. Targeting a CAR to the TRAC locus with CRISPR/Cas9 enhances tumour rejection. Nature. 2017;543:113–117. doi: 10.1038/nature21405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dai X., Park J.J., Du Y., Kim H.R., Wang G., Errami Y., Chen S. One-step generation of modular CAR-T cells with AAV-Cpf1. Nat. Methods. 2019;16:247–254. doi: 10.1038/s41592-019-0329-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ruggiero E., Carnevale E., Prodeus A., Magnani Z.I., Camisa B., Merelli I., Politano C., Stasi L., Potenza A., Cianciotti B.C., et al. CRISPR-based gene disruption and integration of high-avidity, WT1-specific T cell receptors improve antitumor T cell function. Sci. Transl. Med. 2022;14 doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.abg8027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jo S., Das S., Williams A., Chretien A.S., Pagliardini T., Le Roy A., Fernandez J.P., Le Clerre D., Jahangiri B., Chion-Sotinel I., et al. Endowing universal CAR T-cell with immune-evasive properties using TALEN-gene editing. Nat. Commun. 2022;13:3453. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-30896-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bak R.O., Dever D.P., Reinisch A., Cruz Hernandez D., Majeti R., Porteus M.H. Multiplexed genetic engineering of human hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells using CRISPR/Cas9 and AAV6. Elife. 2017;6 doi: 10.7554/eLife.27873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Iancu O., Allen D., Knop O., Zehavi Y., Breier D., Arbiv A., Lev A., Lee Y.N., Beider K., Nagler A., et al. Multiplex HDR for disease and correction modeling of SCID by CRISPR genome editing in human HSPCs. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids. 2023;31:105–121. doi: 10.1016/j.omtn.2022.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Agudelo D., Duringer A., Bozoyan L., Huard C.C., Carter S., Loehr J., Synodinou D., Drouin M., Salsman J., Dellaire G., et al. Marker-free coselection for CRISPR-driven genome editing in human cells. Nat. Methods. 2017;14:615–620. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.4265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Palmer D.J., Turner D.L., Ng P. Bi-allelic Homology-Directed Repair with Helper-Dependent Adenoviruses. Mol. Ther. Methods Clin. Dev. 2019;15:285–293. doi: 10.1016/j.omtm.2019.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shy B.R., MacDougall M.S., Clarke R., Merrill B.J. Co-incident insertion enables high efficiency genome engineering in mouse embryonic stem cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:7997–8010. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li X., Sun B., Qian H., Ma J., Paolino M., Zhang Z. A high-efficiency and versatile CRISPR/Cas9-mediated HDR-based biallelic editing system. J. Zhejiang Univ. Sci. B. 2022;23:141–152. doi: 10.1631/jzus.B2100196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fu Y.W., Dai X.Y., Wang W.T., Yang Z.X., Zhao J.J., Zhang J.P., Wen W., Zhang F., Oberg K.C., Zhang L., et al. Dynamics and competition of CRISPR-Cas9 ribonucleoproteins and AAV donor-mediated NHEJ, MMEJ and HDR editing. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021;49:969–985. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkaa1251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cook P.J., Yang S.J., Uenishi G.I., Grimm A., West S.E., Wang L.J., Jacobs C., Repele A., Drow T., Boukhris A., et al. A chemically inducible IL-2 receptor signaling complex allows for effective in vitro and in vivo selection of engineered CD4+ T cells. Mol. Ther. 2023 doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2023.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Halene S., Wang L., Cooper R.M., Bockstoce D.C., Robbins P.B., Kohn D.B. Improved expression in hematopoietic and lymphoid cells in mice after transplantation of bone marrow transduced with a modified retroviral vector. Blood. 1999;94:3349–3357. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cerosaletti K., Barahmand-Pour-Whitman F., Yang J., DeBerg H.A., Dufort M.J., Murray S.A., Israelsson E., Speake C., Gersuk V.H., Eddy J.A., et al. Single-Cell RNA Sequencing Reveals Expanded Clones of Islet Antigen-Reactive CD4(+) T Cells in Peripheral Blood of Subjects with Type 1 Diabetes. J. Immunol. 2017;199:323–335. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1700172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sadelain M. T-cell engineering for cancer immunotherapy. Cancer J. 2009;15:451–455. doi: 10.1097/PPO.0b013e3181c51f37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.van Loenen M.M., de Boer R., Amir A.L., Hagedoorn R.S., Volbeda G.L., Willemze R., van Rood J.J., Falkenburg J.H.F., Heemskerk M.H.M. Mixed T cell receptor dimers harbor potentially harmful neoreactivity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:10972–10977. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1005802107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bendle G.M., Linnemann C., Hooijkaas A.I., Bies L., de Witte M.A., Jorritsma A., Kaiser A.D.M., Pouw N., Debets R., Kieback E., et al. Lethal graft-versus-host disease in mouse models of T cell receptor gene therapy. Nat. Med. 2010;16:565–570. doi: 10.1038/nm.2128. 1p.following.570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Maddalo D., Manchado E., Concepcion C.P., Bonetti C., Vidigal J.A., Han Y.C., Ogrodowski P., Crippa A., Rekhtman N., de Stanchina E., et al. In vivo engineering of oncogenic chromosomal rearrangements with the CRISPR/Cas9 system. Nature. 2014;516:423–427. doi: 10.1038/nature13902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li J., Kim S.G., Blenis J. Rapamycin: one drug, many effects. Cell Metab. 2014;19:373–379. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2014.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.O'Shea A.E., Valdera F.A., Ensley D., Smolinsky T.R., Cindass J.L., Kemp Bohan P.M., Hickerson A.T., Carpenter E.L., McCarthy P.M., Adams A.M., et al. Immunologic and dose dependent effects of rapamycin and its evolving role in chemoprevention. Clin. Immunol. 2022;245 doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2022.109095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.June C.H., Sadelain M. Chimeric Antigen Receptor Therapy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018;379:64–73. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1706169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Heemskerk M.H.M., Hagedoorn R.S., van der Hoorn M.A.W.G., van der Veken L.T., Hoogeboom M., Kester M.G.D., Willemze R., Falkenburg J.H.F. Efficiency of T-cell receptor expression in dual-specific T cells is controlled by the intrinsic qualities of the TCR chains within the TCR-CD3 complex. Blood. 2007;109:235–243. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-03-013318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ghezraoui H., Piganeau M., Renouf B., Renaud J.B., Sallmyr A., Ruis B., Oh S., Tomkinson A.E., Hendrickson E.A., Giovannangeli C., et al. Chromosomal translocations in human cells are generated by canonical nonhomologous end-joining. Mol. Cell. 2014;55:829–842. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Poirot L., Philip B., Schiffer-Mannioui C., Le Clerre D., Chion-Sotinel I., Derniame S., Potrel P., Bas C., Lemaire L., Galetto R., et al. Multiplex Genome-Edited T-cell Manufacturing Platform for "Off-the-Shelf" Adoptive T-cell Immunotherapies. Cancer Res. 2015;75:3853–3864. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-3321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hu Y., Zhou Y., Zhang M., Ge W., Li Y., Yang L., Wei G., Han L., Wang H., Yu S., et al. CRISPR/Cas9-Engineered Universal CD19/CD22 Dual-Targeted CAR-T Cell Therapy for Relapsed/Refractory B-cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. Clin. Cancer Res. 2021;27:2764–2772. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-20-3863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sather B.D., Romano Ibarra G.S., Sommer K., Curinga G., Hale M., Khan I.F., Singh S., Song Y., Gwiazda K., Sahni J., et al. Efficient modification of CCR5 in primary human hematopoietic cells using a megaTAL nuclease and AAV donor template. Sci. Transl. Med. 2015;7:307ra156. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aac5530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang X., Shin S.C., Chiang A.F.J., Khan I., Pan D., Rawlings D.J., Miao C.H. Intraosseous delivery of lentiviral vectors targeting factor VIII expression in platelets corrects murine hemophilia A. Mol. Ther. 2015;23:617–626. doi: 10.1038/mt.2015.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting the findings of the present study are available upon request from the corresponding authors.