Abstract

Objective

This study aimed to determine whether or not transfusion of fresh red blood cells (RBCs) reduced the incidence of new or progressive multiple organ dysfunction syndrome compared with standard-issue RBCs in pediatric patients undergoing cardiac surgery.

Methods

Preplanned secondary analysis of the Age of Blood in Children in Pediatric Intensive Care Unit study, an international randomized controlled trial. This study included children enrolled in the Age of Blood in Children in Pediatric Intensive Care Unit trial and admitted to a pediatric intensive care unit after cardiac surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass. Patients were randomized to receive either fresh (stored ≤7 days) or standard-issue RBCs. The primary outcome measure was new or progressive multiple organ dysfunction syndrome, measured up to 28 days postrandomization or at pediatric intensive care unit discharge, or death.

Results

One hundred seventy-eight patients (median age, 0.6 years; interquartile range, 0.3-2.6 years) were included with 89 patients randomized to the fresh RBCs group (median length of storage, 5 days; interquartile range, 4-6 days) and 89 to the standard-issue RBCs group (median length of storage, 18 days; interquartile range, 13-22 days). There were no statistically significant differences in new or progressive multiple organ dysfunction syndrome between fresh (43 out of 89 [48.3%]) and standard-issue RBCs groups (38 out of 88 [43.2%]), with a relative risk of 1.12 (95% CI, 0.81 to 1.54; P = .49) and an unadjusted absolute risk difference of 5.1% (95% CI, −9.5% to 19.8%; P = .49).

Conclusions

In neonates and children undergoing cardiac surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass, the use of fresh RBCs did not reduce the incidence of new or progressive multiple organ dysfunction syndrome compared with the standard-issue RBCs. A larger trial is needed to confirm these results.

Key Words: red blood cell, erythrocyte, length of storage, pediatric cardiac surgery, cardiopulmonary bypass, transfusion, critical care medicine

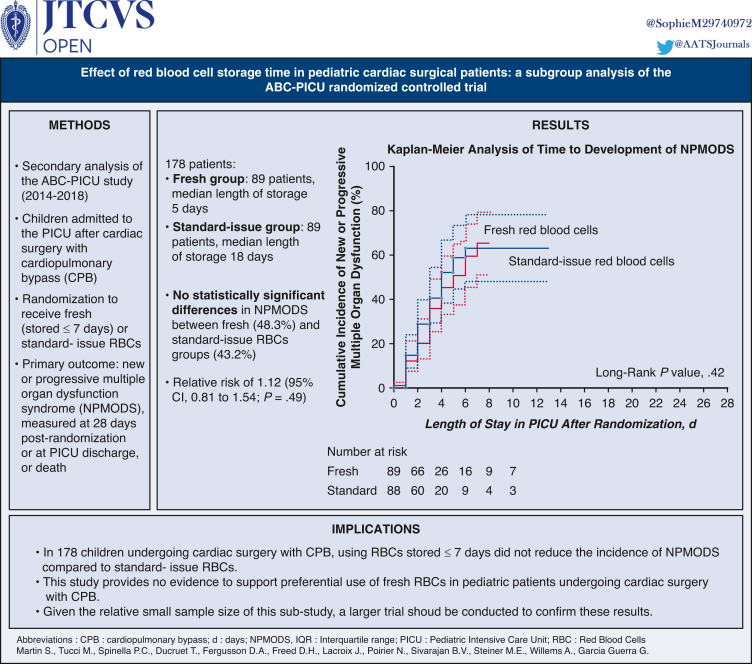

Graphical abstract

Kaplan-Meier analysis of time to development of NPMODS.

Central Message.

In 178 neonates and children undergoing cardiac surgery with CPB, the transfusion of RBCs stored ≤7 days did not reduce the incidence of NPMODS compared with standard-issue RBCs.

Perspective.

This secondary analysis of a multicenter randomized controlled trial provides no evidence to support the use of fresh RBCs in pediatric patients undergoing cardiac surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass. Given the relative small sample size of this substudy, a larger trial shoud be conducted to confirm the results.

Pediatric patients undergoing cardiac surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) are commonly exposed to red blood cell (RBCs) transfusions during both surgery and their subsequent recovery in a pediatric intensive care unit (PICU). A survey published in 2010 reported that practitioners in most North American hospitals preferentially transfuse RBCs that have less than 14 days of storage for neonatal cardiac surgery (72%) and for intraoperative use for cardiac surgery patients (67%).1 This practice in children who undergo cardiac surgery is based on the premise that structural and metabolic changes that occur in RBCs during storage, commonly called storage lesions,2 can have adverse effects with transfusion of older RBCs, increasing the risk of arrhythmia, organ failure, and mortality in critically ill children. If data from clinical trials indicates that the use of fresh RBCs does not improve outcomes, then the practice should be reconsidered because it adds a logistic burden on blood banks that has no patient benefit and may lead to waste of blood products, The Age of Blood in Children in Pediatric Intensive Care Units (ABC-PICU) randomized controlled trial (RCT) (NCT01977547) showed that transfusion of fresh RBCs compared with standard-issue RBCs to critically ill children did not reduce the incidence of new or progressive multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (NPMODS), which includes mortality.3 These findings corroborated those of prior studies undertaken in certain neonatal and pediatric subpopulations that reported no benefit with the use of fresher RBCs.4,5 However, these studies could not be applied to the very specific population of children with cardiac disease due to their distinct physiology and the specificities of cardiac surgery with CPB, including significant transfusion volumes of blood products.

There are limited data regarding the influence of RBCs’ storage duration on clinical outcomes of children requiring cardiac surgery with CPB. This lack of evidence is in part due to difficulties in controlling for confounding factors (ie, surgical complexity, volume of RBCs transfused, and transfusions of other blood products) in this population.6 Most observational studies in children requiring cardiac surgery have shown no benefit with transfusion of RBCs with shorter storage time compared with standard-issue RBCs.7, 8, 9 However, contradictory results have been reported with some data suggesting that longer RBCs’ storage duration is associated with an increased risk of infection,10 or worse outcome when larger volumes of transfusion are administered.11 Recent recommendation do not support the use of fresher RBCs in pediatric cardiac surgery patients6; however, this recommendation is based on low quality pediatric evidence that requires further research to address this issue. Adult RCTs have shown no difference in patient outcome in the cardiac postoperative population.12, 13, 14 However, pediatric studies are needed, especially when considering the physiology of complex heart diseases. We performed a preplanned subgroup analysis of the ABC-PICU trial to determine the effect of RBCs storage time on NPMODS in children undergoing cardiac surgery with CPB.

Material and Methods

Parent Trial

The study protocol of ABC-PICU trial has been previously published.15 This RCT was an international, multicenter, blinded, superiority, randomized controlled trial performed between February 2014 and November 2018 in 50 tertiary care centers. Patients admitted to participating PICUs and aged 3 days to 16 years were screened for eligibility. Patients were eligible if a first RBCs transfusion was prescribed within 7 days after PICU admission or if they received their first RBCs transfusion for an elective surgery requiring subsequent admission to the PICU, which included blood used in the CPB circuit. Surgical patients were randomized before their surgical intervention and the storage time of RBCs used for priming of the CPB circuit as well as for subsequent transfusions was based on the patient's group allocation. Other inclusion criteria were expected length of stay in the PICU >24-hours as assessed by the clinical team, no transfusion in the prior 28 days, and weight ≥3.0 kg at the time of the PICU admission. Exclusion criteria are listed in the study protocol of ABC-PICU trial.15 Patients were randomized to receive RBCs stored for no more than 7 days (fresh arm) or standard-issue RBCs that were generally the oldest in inventory at the time of the transfusion order (first-in first-out policy) in the standard-issue arm.1,16

Cardiac Surgery Secondary Analysis

The analytic plan for this preplanned subgroup study was developed post hoc. We selected the subpopulation that underwent cardiac surgery with CPB who were enrolled in ABC-PICU. Cardiac patients who did not undergo surgery or who had surgery without CPB were excluded. The hypothesis for this subgroup analysis was, as for the original study, that transfusion of fresh RBCs would be superior to the transfusion of standard-issue RBCs in the development of NPMODS. Approval for this study was obtained from the Institutional Review Board/Research Ethics Board of all participating sites (approval No.: 2021-3151 (June 2013)). Written informed consent for publication of study data was obtained before enrollment in the parent trial.

Outcomes

Primary outcome measure

The primary outcome for the ABC-PICU trial was the incidence rate of 28-day NPMODS.3 Thus, this subgroup analysis compares the development of NPMODS in children who underwent a cardiac surgery with CPB transfused with either RBCs stored ≤7 days or standard issue RBCs. We used the definition of Proulx and colleagues17 to diagnose cases of MODS and the definition of new or progressive MODS suggested by Lacroix and colleagues,18 whose patients included cardiac surgery patients. Patients with no organ dysfunction at randomization were categorized as having new MODS if they developed 2 or more concurrent organ dysfunctions. Those with 1 organ dysfunction that progressed to 2 or more were also considered to have developed new MODS, whereas those with 2 or more organ dysfunctions that developed additional organ dysfunctions were considered to have progressive MODS. Patients who died were also considered to have progressive MODS. Additional data were collected by chart review to ascertain the presence of MODS before cardiac surgery; no definitions of outcomes were changed from the original trial. Monitoring of organ dysfunction during the postoperative period was done up to 28 days postrandomization, death, or PICU discharge, whichever occurred first.

Secondary outcomes

Secondary outcomes were those included in the ABC-PICU trial plus additional outcomes specific to the cardiac population and collected up to 7 calendar days after randomization or PICU discharge or death, whichever occurred first. The ABC-PICU trial database provided 28-day and 90-day all-cause mortality, nosocomial infections, Pediatric Logistic Organ Dysfunction-2 score,19 severe sepsis, septic shock, acute respiratory distress syndrome,20,21 and mechanical ventilation-free and PICU-free days. PICU-free days were calculated by subtracting from 28 days the length of stay in the PICU postrandomization; it was 0 if the patient died during this time period. In addition of original secondary outcomes, cardiac-specific secondary outcomes were retrospectively collected, including postoperative total blood loss (measured as total chest tube output in milliliters per kilogram per day) at Day 1 and 2, delayed sternal closure, additional unplanned surgical procedure (eg, mediastinal re-exploration, emergency chest reopening, and emergency surgery involving return to operating room), extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, renal replacement therapy by peritoneal dialysis or continuous renal replacement therapy, cardiac arrest or cardiopulmonary resuscitation, occurrence of arrhythmias requiring treatment, vasoactive-inotropic support score22 and highest lactate and potassium level. These data were extracted retrospectively by chart review.

Statistical Analysis

Baseline characteristics in both study groups were assessed using frequency distributions and univariate descriptive statistics, including measures of central tendency and dispersion. Dichotomous data are presented as numbers and percentages; continuous data are expressed as mean ± SD or medians (interquartile range [IQR]), as appropriate. Postrandomization characteristics of interventions and cointerventions are presented using frequency distributions with measures of central tendency and dispersion and analyzed using relative risks and 95% CIs for dichotomous data and either independent t tests or Wilcoxon rank-sum tests for continuous data as appropriate.

The prespecified primary analysis of the primary outcome included patients according to their randomization group. The primary analysis was performed using an unadjusted χ2 comparing the proportion of patients who acquired organ dysfunction up to 28 days after randomization. The principal measure of effect was an unadjusted absolute risk reduction with 95% CIs. All secondary outcomes were analyzed in the same manner as the primary outcome.

A sensitivity analysis on primary outcome was performed using logistic regression adjusting for risk factors based on clinical rationale, including the following variables: weight at admission to the PICU, hemoglobin level before first transfusion, CPB duration, and Society of Thoracic Surgeons–European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery score. Circulatory arrest and therapeutic hypothermia during surgery were found highly associated to our primary outcome (P = .013 and P < .001, respectively) and were forced into the multivariate analysis.

In addition to the primary analysis, a per-protocol analysis was performed. Per-protocol populations consisting of patients who exclusively received RBCs stored ≤7 days in the fresh group and consisting of all the patients in the standard-issue group. Subgroup analysis of the primary outcome was also performed by age group. Interactions were assessed by adding the treatment, subgroup of interest, and interaction term in a multivariable logistic regression model, where covariates were chosen based on clinical judgment. Unadjusted and adjusted Cox proportional-hazards models were also performed to analyze time to first occurrence of new or progressive MODS. Censoring was defined as date of PICU discharge, end of follow-up (28 days), or death. The treatment effects were expressed as hazard ratios with 95% CIs.

Missing data were treated as missing, and the number of patients missing for each variable is reported. No imputation was done for missing outcomes. All analyses are presented without any adjustment for multiple comparisons. Because of the potential for type 1 error due to multiple comparisons, findings for analyses of secondary and exploratory outcomes should be interpreted as exploratory. Data were analyzed with SAS software version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc). All statistical tests were 2-sided.

Results

Patients

Among the 1461 patients included in the analysis of the original study, 211 were reported as cardiac surgical patients (Figure 1). Additional data collection could not be completed for 21 patients (8 from the fresh group, 13 from the standard-issue group) in 4 centers due to administrative or logistic issues at their center. One hundred ninety patient charts were retrieved to confirm inclusion criteria and collect additional cardiac-related information. After meeting exclusion criteria, 12 other patients were excluded from the analysis: 9 had cardiac surgery with no CPB, 2 were cardiac patients that did not undergo cardiac surgery, and 1 patient was randomized 5 days after cardiac surgery. The final analysis of this substudy involved 178 patients (from 4 centers) among whom 89 were randomized to the fresh group and 89 to the standard-issue group. There were no significant differences in baseline characteristics between groups (Table 1). The median age was 0.6 years (IQR, 0.3-2.2 years) in the fresh group and 0.6 years (IQR, 0.4-3.0 years) in the standard-issue group. The median weight at admission was 7.5 kg (IQR, 5.4-11.6 kg) in the fresh group and 7.1 kg (IQR, 5.0-12.9 kg) in the standard group. Fifteen patients (16.9%) in the fresh group and 13 (14.6%) in the standard-issue group were younger than age 28 days. One patient in each group had MODS before surgery (1.1%, respectively).

Figure 1.

Flow chart for patients analyzed in the Age of Blood in Children in Pediatric Intensive Care Unit (ABC-PICU)- Cardiac Surgery trial.

Table 1.

Baseline patient characteristics

| Red blood cell group | Fresh (n = 89) | Standard-issue (n = 89)∗ |

|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 0.6 (0.3-2.2) | 0.6 (0.4-3.0) |

| ≤28 d | 15 (16.9) | 13 (14.6) |

| 29-365 d | 36 (40.4) | 39 (43.8) |

| >365 d | 38 (42.7) | 36 (40.4) |

| Weight at admission to ICU (kg) | 7.5 (5.4-11.6) | 7.1 (5.0-12.9) |

| Sex | ||

| Girl | 40 (44.9) | 41 (46.1) |

| Boy | 49 (55.1) | 48 (53.9) |

| Time from hospital to ICU admission (d) | 1.6 (0.6-3.9) | 1.6 (0.6-3.6) |

| Recruitment per country | ||

| United States, 2 sites | 1 (1.1) | 2 (2.2) |

| Canada, 2 sites | 88 (98.9) | 87 (97.8) |

| ICU admission to randomization (h) | −6.0 (−8.0 to −5.0) | −6.0 (−8.0 to −5.0) |

| Location of first transfusion | ||

| Operating room | 86 (96.6) | 82 (92.1) |

| ICU | 3 (3.4) | 7 (7.9) |

| Hemoglobin level before first transfusion (g/dL) | 12.8 (11.3-14.2) | 12.5 (10.9-14.5) |

| Location before cardiac surgery | ||

| Home, elective surgery | 58 (65.2) | 64 (71.9) |

| Hospital, pediatrics and cardiology units | 11 (12.4) | 11 (12.4) |

| Neonatal ICU | 14 (15.7) | 10 (11.2) |

| Pediatric ICU | 6 (6.7) | 4 (4.5) |

| No. of organ dysfunctions before surgery (from chart review) | ||

| 0 | 83 (93.3) | 85 (95.5) |

| 1 | 5 (5.6) | 3 (3.4) |

| 2† | 1 (1.1) | 1 (1.1) |

| Univentricular physiology before surgery | 22 (24.7) | 19 (21.3) |

| Cyanotic heart desease before surgery | 46 (51.7) | 46 (51.7) |

| Prior cardiac surgery | 29 (32.6) | 32 (36.0) |

| Genetic abnormality or syndrome | 17 (19.1) | 18 (20.2) |

| Trisomy 21 | 7 (7.9) | 5 (5.6) |

| Di George syndrome | 2 (2.2) | 2 (2.2) |

| Other | 7 (7.9) | 12 (13.5) |

| Unknown | 1 (1.1) | 0 (0.0) |

| Cardiac surgery details | ||

| Emergency procedure | 3 (3.4) | 2 (2.2) |

| STAT mortality category‡ | ||

| 1 | 16 (18.0) | 15 (16.9) |

| 2 | 34 (38.2) | 43 (48.3) |

| 3 | 15 (16.9) | 11 (12.4) |

| 4 | 24 (27.0) | 16 (18.0) |

| 5 | 0 (0.0) | 4 (4.5) |

| Cardiopulmonary bypass duration (min) | ||

| Mean ± SD | 133.3 ± 84.7 | 123.8 ± 63.2 |

| Median (IQR) | 111.5 (85-159.5) | 114 (73-164) |

| Aortic crossclamp time (min) | ||

| Mean ± SD | 70.7 ± 57.8 | 65.0 ± 51.1 |

| Median (IQR) | 67 (27-98) | 54 (28-111) |

| Circulatory arrest, yes | 4 (4.5) | 8 (9.0) |

| Therapeutic hypothermia during surgery | 26 (29.2) | 26 (29.2) |

| If hypothermia: lowest temperature during surgery (°C) | ||

| Mean ± SD | 26.6 ± 3.6 | 26.4 ± 3.9 |

| Median (IQR) | 28 (26-28.7) | 28 (23.5-28.6) |

Values are presented as median (interquartile range [IQR]) or n (%) unless otherwise noted. ICU, Intensive care unit; STAT, Society of Thoracic Surgeons–European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery.

One patient who was randomized to the standard-issue group died in the operating room during cardiac surgery and had no data available for the primary outcome and some secondary outcomes. This patient was not included in the primary outcome but was included in some baseline analyses and in mortality analyses.

Multiple organ dysfunction syndrome, as defined by Proulx and colleagues17 and explained further in the Methods section.

Defined by O'Brien and colleagues.23

Intervention

Intervention and cointerventions are reported in Table 2. The median RBCs storage age in the fresh group was 5 days (IQR, 4-6 days) compared with a storage age of 18 days (IQR, 13-22 days) in the standard-issue group (P < .001). The median number of total RBCs transfusions administered was similar in both groups: 2 (IQR, 1-3) in the fresh group and 2 (IQR, 1-2) in the standard-issue group (P = .76). The median total volume of RBCs transfused per patient after randomization in the fresh group was 47.2 mL/kg (IQR, 28.7-110.2 mL/kg) compared with 40.2 mL/kg (IQR, 28.7-63.5 mL/kg) in the standard-issue group (P = .14).

Table 2.

Anemia and red blood cell (RBC) transfusions: intervention and cointerventions∗

| Intervention and cointervention | RBC group |

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fresh (n = 89) | Standard-issue (n = 89)† | ||

| RBCs transfusions after randomization | |||

| No. of transfusions | 2 (1-3) | 2 (1-2) | .76 |

| No. of patients | |||

| 1 transfusion | 41 (46.1) | 33 (37.1) | .05 |

| 2 transfusions | 20 (22.5) | 35 (39.3) | |

| ≥3 transfusions | 28 (31.1) | 21 (23.5) | |

| Duration of RBC unit storage (d) | 5 (4-6) | 18 (13-22) | <.001 |

| Total volume of RBCs transfused per patient‡ (mL/kg) | 47.2 (28.7-110.2) | 40.0 (28.7-63.5) | .14 |

| Donor exposure to RBCs in transfused patients | |||

| No. of exposures per patient | 2 (1-3) | 2 (1-2) | .98 |

| No. of patients | 89 | 89 | |

| Adherence | |||

| Adherence to study protocol, patients§ | 84/89 (95.5) | 89/89 (100) | .04 |

| Adherence to protocol with respect to length of storage, transfusions‖ | 325/357 (93.7) | 230/230 (100) | |

| CPB priming | |||

| RBCs for priming | 83 (93.3) | 76 (85.4) | .09 |

| Volume of RBCs for priming CBP (mL/kg) | 36.6 (22.0-53.7) | 32.9 (23.0-47.7) | |

| Fresh or fresh frozen plasma for priming | 56 (62.9) | 58 (65.2) | .75 |

| Volume of fresh or fresh frozen plasma for priming (mL/kg) | 18.4 (11.9-31.2) | 18.8 (11.1-29.3) | |

| Blood products during surgery, excluding CPB priming | |||

| RBCs | 44 (49.4) | 41 (46.1) | .65 |

| Volume of RBCs, median (mL/kg) | 31 (15-76) | 22 (12-37) | |

| Fresh or fresh frozen plasma | 42 (47.2) | 47 (52.8) | .45 |

| Volume of fresh or fresh frozen plasma median (mL/kg) | 20 (13-48) | 19 (11-33) | |

| Platelet | 48 (53.9) | 47 (52.8) | .88 |

| Volume of platelet, median (mL/kg) | 16 (8-24) | 15 (10-20) | |

| Cryoprecipitate | 44 (49.4) | 40 (45.0) | .55 |

| Volume of cryoprecipitate (mL/kg) | 3.9 (1.8-7.7) [n = 32] | 3.0 (2.2-5.9) [n = 32] | |

| Median (IQR) (U/kg) | 0.32 (0.22-0.38) [n = 12] | 0.30 (0.20-0.34) [n = 8] | |

| Recombinant factor VIIa | 1 (1.1) | 2 (2.3) | 1.00 |

| Other blood products | 23 (25.8) | 24 (27.0) | .87 |

| Blood products and other cointerventions after randomization¶ | |||

| Frozen or fresh frozen plasma | 71 (79.8) | 70 (78.7) | .85 |

| Apheresis platelets | 52 (58.4) | 50 (56.2) | .76 |

| Random donor platelets | 14 (15.5) | 16 (18.0) | .69 |

| Cryoprecipitate | 51 (57.3) | 51 (57.3) | 1.00 |

| Albumin 5% | 17 (19.1) | 8 (9.0) | .05 |

| Albumin 25% | 78 (87.6) | 74 (83.1) | .40 |

| Systemic corticosteroids in ICU | 19 (21.3) | 14 (15.7) | .33 |

| Use of tranexamic acid in operating room | 86 (97.7) | 87 (97.8) | 1.00 |

| Use of tranexamic acid in ICU | 4 (4.5) | 12 (13.6) | .034 |

| Use of nitric oxide | 44 (49.4) | 35 (39.8) | .20 |

Values are presented as median (interquartile range), n (%), or n/N (%). CBP, Cardiopulmonary bypass; IQR, interquartile range; ICU, intensive care unit.

In all comparisons, the fresh group was used as the reference. Postrandomization characteristics of interventions and cointerventions are presented using frequency distributions with measures of central tendency and dispersion and analyzed using relative risks and 95% CI for dichotomous data and either independent t tests or Wilcoxon rank-sum tests for continuous data depending on their distribution.

One patient who was randomized to the standard-issue group died in the operating room during cardiac surgery and had no data available for the primary outcome, some secondary outcomes, and some cointerventions. This patient was not included in the primary outcome but was included in mortality analyses.

Total volume of RBCs transfused by patient include RBCs transfused in the CPB, during surgery, and in ICU.

For the purpose of this study, patients in the fresh group were considered adherent to protocol if 80% of the RBCs were stored for 7 days or fewer and if no RBCs were stored for more than 14 days during the 28-day follow-up period.

Adherence was defined in the research protocol as (number of transfusions with RBCs stored for ≤7 days)/(total number of transfusions) for fresh group and as (number of standard-issue transfusions)/(total number of transfusions) for the standard-issue group.

Total of blood products other than RBCs transfused after randomization (including CBP priming, during surgery, and during ICU stay).

Cointerventions

There were no statistically significant differences between groups for any other blood products administered including frozen plasma, platelets and cryoprecipitate (Table 2). Use of tranexamic acid in the PICU occurred in 4 patients (4.5%) in the fresh group and 12 patients (13.6%) in the standard-issue group (P = .034).

Primary Outcome

There was no statistically significant difference in development of NPMODS between groups 28 days after randomization. NPMODS occurred in 43 of 89 patients (48.3%) in the fresh-blood group and 38 of 88 (43.2%) in the standard-issue group with a relative risk of 1.12 (95% CI, 0.81-1.54; P = .49) and an unadjusted absolute risk difference of 5.1% (95% CI, −9.5% to 19.8%; P = .49) (Table 3). The hazard ratio for the time to development of NPMODS after randomization in the fresh-blood and the standard-issue group was 0.84 (95% CI, 0.54-1.32; P = .45) (Figure 2).

Table 3.

Clinical trial primary and subset outcomes∗

| Outcome | n/N evaluated (%)† red blood cell group |

Relative risk (95% CI) |

Absolute risk difference (95% CI) |

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fresh | Standard issue | ||||

| Primary outcome: MODS‡ | |||||

| New and/or progressive MODS§ | 43/89 (48.3) | 38/88‖ (43.2) | 1.12 (0.81-1.54) | 5.1 (−9.5 to 19.8) | .49 |

| New MODS | 43/89 (48.3) | 37/88 (42.1) | |||

| Progressive MODS | 0/89 (0.0) | 1/88 (1.1) | |||

| Subset outcomes: MODS | |||||

| Age (d) | |||||

| ≤28 | 15/15 (100.0) | 13/13 (100.0) | – | – | |

| 29-365 | 15/36 (41.7) | 20/39 (51.3) | 0.81 (0.50-1.33) | −9.6 (−32.1 to 12.9) | .51 |

| >365 | 13/38 (34.2) | 5/36 (13.9) | 2.46 (0.98-6.21) | 20.3 (0.1-39.2) | |

| STAT mortality category | |||||

| 1-3 | 23/65 (35.4) | 21/69 (30.9) | 1.15 (0.71-1.86) | 4.5 (−11.5 to 20.5) | .58 |

| 4 or 5 | 20/24 (83.3) | 17/20 (85.0) | 0.98 (0.76-1.27) | −1.7 (−23.3 to 20.0) | |

| Sensitivity analysis on primary outcome: MODS | |||||

| Adjusted for baseline covariates¶ | 1.01 (0.90-1.12)∗∗ | .89 | |||

MODS, Multiple organ dysfunction syndrome; STAT, Society of Thoracic Surgeons–European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery.

In all comparisons, the fresh red blood cell group was used as the reference. Superiority was checked for the primary outcome and for all secondary outcomes analyzing patients according to their randomization groups. The principal analysis was performed using an unadjusted χ2 comparing the proportion of patients who acquire new or progressive MODS after randomization. The principal measure of effect is an unadjusted absolute risk difference with 95% CI. Dichotomous secondary outcomes were analyzed using risk differences and 95% CI followed by logistic regression procedures. Continuous outcomes were analyzed using independent t tests or Wilcoxon rank-sum tests depending on distribution of data.

Refers to number of patients with outcome/number of patients evaluated (proportion). n refers to number analyzed when it is less than the group total.

The primary outcome is described in the Methods section.

Defined by Proulx and colleagues.17

One patient who was randomized to the standard-issue group died in the operating room during cardiac surgery and had no data available for the primary outcome and some secondary outcomes. This patient was not included in the primary outcome but was included in mortality analyses.

Adjusted for weight at admission to ICU, kg (log transformed), P < .001, hemoglobin level before first transfusion, P = .071, cardiopulmonary bypass duration (log transformed), P = .002, circulatory arrest, P = .013, therapeutic hypothermia, P < .001 (P values are values from univariate analysis) and STAT score (as categorical).

Odds ratio (95% CI) from multivariate logistic regression.

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier analysis of time to development of new or progressive multiple organ dysfunction syndrome. PICU, Pediatric intensive care unit. The follow-up of participants ended at death, PICU discharge, or 28 days postrandomization, whichever happened first. Assumption of proportionality of hazard ratios was tested by introducing the interaction term log(time × group) in the model. Proportionality was not rejected (P = .76). Cumulative incidence of new or progressive multiple organ dysfunction syndrome and 95% CI.

The per-protocol analysis showed no significant difference in the primary outcome. NPMODS occurred in 41 of 85 patients (48.2%) in the fresh-blood group and 38 of 88 (43.2%) in the standard-issue group, with an unadjusted absolute risk difference of 5.1 (95% CI, −9.8 to 19.9; P = .51) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Clinical trial secondary outcomes∗

| Outcome | n/N evaluated (%)† red blood cell group |

Relative risk (95% CI) |

Absolute risk difference (95% CI) |

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fresh | Standard issue | ||||

| Per-protocol analysis‡ | |||||

| New or progressive MODS§ | 41/85 (48.2) | 38/88 (43.2) | 1.12 (0.81-1.55) | 5.1 (−9.8 to 19.9) | .51 |

| Mortality | |||||

| In ICU | 3/89 (3.4) | 0/89 (0.0) | NA | 3.4 (0.0-7.1) | .08 |

| In hospital | 3/89 (3.4) | 2/89 (2.3) | 1.50 (0.26-8.76) | 1.1 (−3.7 to 6.0) | .65 |

| ≤28 d | 2/89 (2.3) | 2/89 (2.3) | 1.00 (0.14-6.94) | 0.0 (−4.4 to 4.4) | 1.00 |

| ≤90 d | 3/89 (3.4) | 2/89 (2.3) | 1.50 (0.26-8.76) | 1.1 (−3.7 to 6.0) | .65 |

| Morbidity outcomes‖ | |||||

| Sepsis | 9/88 (10.2) | 7/88 (8.0) | 1.28 (0.50-3.30) | 2.3 (−6.2 to 10.8) | .60 |

| Severe sepsis | 0/88 (0.0) | 0/88 (0.0) | NA | ||

| Septic shock | 8/88 (9.1) | 5/88 (5.7) | 1.60 (0.54-4.70) | 3.4 (−4.3 to 11.1) | .39 |

| ARDS¶ | 0/88 (0.0) | 0/88 (0.0) | NA | ||

| Nosocomial infections# | 2/89 (2.3) | 2/89 (2.3) | 1.00 (0.14-6.94) | 0.0 (−4.4 to 4.4) | 1.00 |

MODS, Multiple organ dysfunction syndrome; ICU, intensive care unit; NA, not applicable; ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome.

In all comparisons, the fresh red blood cell group was used as the reference. Superiority was checked for the primary outcome and for all secondary outcomes analyzing patients according to their randomization groups. The principal analysis was performed using an unadjusted χ2 comparing the proportion of patients who acquire new or progressive MODS after randomization. The principal measure of effect is an unadjusted absolute risk difference with a 95% CI. Dichotomous secondary outcomes were analyzed using risk differences and 95% CI followed by logistic regression procedures. Continuous outcomes were analyzed using independent t tests or Wilcoxon rank-sum tests depending on distribution of data.

Refers to number of patients with outcome/number of patients evaluated (proportion). n refers to number analyzed when it is less than the group total.

Patients who exclusively received red blood cells 7 days or fewer in the fresh group and all patients in the standard-issue group.

Defined by Proulx and colleagues.17

Sepsis, severe sepsis, and septic shock as defined by Goldstein and colleagues.24

Adjusted analyses for baseline covariates (ie, weight at admission to ICU, hemoglobin level before first transfusion, CPB duration, and Society of Thoracic Surgeons–European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery score) and periprocedural factors (eg, circulatory arrest and therapeutic hypothermia) showed no significant difference in the primary outcome in the fresh-blood vs standard-issue groups with an unadjusted relative risk of 1.01 (95% CI, 0.90-1.12; P = .89) (Table 3).

Secondary Outcomes

No statistically significant differences were found for morbidity and mortality outcomes (Table 4). Incidence of sepsis was 10.2% (9 out of 88) in the fresh-blood group and 8.0% (7 out of 88) in the standard-issue group (P = .60) and incidence of nosocomial infections was identical (2.3% [2 of 89]) in each group (P = 1.00) (Table 4). There were no statistically significant differences observed between groups for 28-day ICU-free days, 28-day mechanical ventilation-free days, length of hospital stay and median worst Pediatric Logistic Organ Dysfunction-2 score (Table E2). There were no statistically significant differences observed between groups for chest tube output, mediastinal re-exploration, delayed sternal closure, vasoactive-inotropic support, and lactate and potassium highest level (Table 5).

Table 5.

Cardiac-specific outcomes

| Outcome | Red blood cell group |

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fresh | Standard-issue | ||

| Chest tube output Day 1 (mL/kg) | |||

| Median (IQR) | 8.6 (5.1-18.6) [n = 84] | 9.6 (5.5-18.9) [n = 87] | .39 |

| Chest tube output Day 2 (mL/kg) | |||

| Median (IQR) | 11.1 (5.3-26.1) [n = 87] | 13.4 (7.5-24.3) [n = 88] | .32 |

| Mediastinal re-exploration | 8 (9.0) | 5 (5.7) | .40 |

| Emergency chest re-opening | 6 (6.7) | 2 (2.3) | .15 |

| Open sternum at ICU entry | 14 | 9 | .29 |

| ECMO | 3 (3.3) | 1 (1.1) | .62 |

| CRRT | 2 (2.2) | 0 (0.0) | .50 |

| Peritoneal dialysis | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Cardiac arrest or need for CPR | 6 (6.7) | 1 (1.1) | .12 |

| Arrhythmias requiring pharmacological treatment or cardioversion | 11 (12.4) | 6 (6.8) | .21 |

| Vasoactive-inotropic score∗, Day 1 | 5.5 (0.5-9.8) [n = 84] | 7.2 (3.0-10.0) [n = 87] | .23 |

| Vasoactive-inotropic score, ICU stay, Day 1-7 | 4.0 (1.0-6.7) [n = 89] | 4.0 (1.1-6.1) [n = 88] | .67 |

| Highest lactate level (mmol/L) | 2.3 (1.8-4.0) [n = 89] | 2.5 (1.9-4.3) [n = 88] | .40 |

| Highest potassium level (mmol/L) | 4.7 (4.3-5.2) [n = 89] | 4.6 (4.4-5.1) [n = 88] | .32 |

Values are presented as n (%) or median (interquartile range [IQR]) unless otherwise noted. ICU, Intensive care unit; ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; CRRT, continuous renal replacement therapy; CPR, cardiopulmonary resuscitation.

Defined by Gaies and colleagues.22

Discussion

In this preplanned subgroup analysis of an RCT involving pediatric cardiac surgery patients with CPB, the transfusion of fresh RBCs in the operating room and in the PICU did not reduce the development of NPMODS or mortality compared with the use of standard-issue RBCs. Results on most secondary outcomes were consistently similar between groups. Our findings may not support the use of fresher RBCs in children undergoing cardiac surgery with CPB, including neonates.

Patients, Intervention, and Cointervention

Our 2 groups are well balanced. The only significant difference between groups was the use of tranexamic acid in the PICU. However the overall incidence of tranexamic use remain low (4 patients [4.5%] in the fresh group and 12 patients [13.6%] in the standard-issue group) and is based on center-specific practices. It seems unlikely there is a relationship with the intervention because other parameters reflecting bleeding complications were not different between groups (ie, chest tube output and use of other blood products after randomization).

Main Results

The results of this study are consistent with those of previously published RCTs comparing the effect of fresh versus older RBCs in critically ill children,3 premature neonates,4 severely anemic children,5 adult patients,14,16,28 and adult cardiac surgery patients.12,13

Published studies describing the impact of RBCs storage duration on clinical outcomes in the pediatric population following cardiac surgery are limited. Retrospective data have shown conflicting results. Several retrospective studies have reported no benefit associated with transfusion of fresher RBCs compared with standard issue,7,8 whereas others suggested an association between the administration of older blood, especially with larger volumes of transfusion,11 and increased postoperative morbidity.29,30 However, these studies are limited by their observational nature and subjected to significant bias due to confounding by indication, mixed storage time of RBCs in patients receiving multiple transfusions, and the inability to rule out confounding by other unmeasured variables related to the outcomes of interest. Based on these issues, it has been impossible to determine whether or not a possible cause–effect relationship exists between age of blood and adverse outcomes in pediatric patients undergoing cardiac surgery with CPB.

The results of prospective studies have also been contradictory. Cholette and colleagues31 published an RCT that compared washed vs standard RBCs and platelets transfusions among children undergoing cardiac surgery with CPB. In 2015, they published a secondary analysis of their trial, including 128 patients who did not demonstrate an association between RBCs storage age and survival.10 However, the postoperative infection rate was significantly higher in children who received at least 1 RBC unit stored 25 to 38 days when compared with those in whom the oldest unit received was stored 7 to 15 days (34% vs 7%; P = .004).10 These results have not been confirmed by other prospective studies, nor by the present study. It is important to underline that in Cholette’s10,31 study patients were not transfused with other blood products like platelet, fresh frozen plasma, and cryoprecipitate; in addition, the storage age of RBCs that are associated with infection is higher than the median storage age in our study. However the vast majority of centers tend to transfuse other blood products during CBP and surgery, so our study population reflects common practice of most centers. In 2019, Bishnoi and colleagues9 published a prospective observational study on the influence of length of storage of packed RBCs used to prime CPB circuit on outcomes after pediatric cardiac surgery. One hundred ninety-eight consecutively recruited children were divided into 2 groups based on whether they received blood with a storage age ≤14 or >14 days.9 There were no statistically significant differences in postoperative hepatic, pulmonary or hematological complications, sepsis, multiorgan failure, duration of mechanical ventilation, length of PICU and hospital stay, and mortality. Our study corroborates these findings. In addition, there is a trend, although not significant, for an increase in NPMODS in the fresh-blood group. Similar trend was previously reported in a systematic review and meta-analysis gathering 12 pediatric and adult randomized trials (5229 participants) evaluating the influence of the age of transfused RBCs:32 These studies reported little or no influence of fresher vs older RBCs on mortality or on adverse events and suggested that fresher RBCs may increase the risk of nosocomial infection. Of note, in that review, development of NPMODs was not evaluated.

The Pediatric Critical Care Transfusion and Anemia Expertise Initiative has recently published recommendations for RBCs transfusion in infants and children with acquired and congenital heart disease.6 These recommendations suggest the use of standard-issue RBCs in children with acquired or congenital heart disease requiring transfusion, acknowledging that there are insufficient data to support systematic transfusion of fresher RBCs in this population. However, they recognize this as a weak recommendation with low quality of evidence supported mainly by observational studies. Our findings provide additional evidence supporting this recommendation.

Strengths and Limitations

Several strengths of this study should be highlighted. The study design involved randomization to fresh or standard-issue blood before going on CPB; this subgroup analysis was planned a priori during the development of the original study with an analysis plan elaborated post hoc. Based on design and baseline characteristics, this study is unlikely to have selection bias. Even more, the adjusted analysis confirms the results and showed no difference between groups. To our knowledge, this is the only existing cohort of pediatric patients undergoing cardiac surgery included in an RCT that evaluated the effect of RBCs length of storage on outcome.

Our study has some limitations. Its major limitation is the relatively small number of patients included, with some patients lost due to logistic issues. As a result, there is not adequate power to make firm conclusions regarding the lack of difference in outcomes between study groups. Also, this secondary analysis of the cardiac population includes mainly Canadian patients limiting its external validity. However, this study provides a strong argument for a larger trial and data that should help designing a future study. Some of the cardiac-specific data were collected retrospectively and not during the original trial. Finally, our study was not able to compare the use of very fresh RBCs (<2 days) vs standard of care. However, the use of very fresh RBCs is not supported by current evidence or practice, and would be difficult to implement. In the same way, this study does not allow to conclude on the potential effect of very old RBCs (eg, with 35-42 days of storage).

Conclusions

In neonates and children undergoing cardiac surgery with CPB, transfusion of fresh RBCs did not reduce the incidence of NPMODS, mortality, or postoperative complications compared with standard-issue RBCs (Figure 3). Our findings may not support the use of RBCs stored ≤7 days rather than standard delivery RBCs in this population. A larger trial will be needed to confirm our results.

Figure 3.

Graphical abstract.

Conflict of Interest Statement

Dr Spinella is a consultant for Hemanext and the chief medical officer and co-founder of Kalocyte. All other authors reported no conflicts of interest.

The Journal policy requires editors and reviewers to disclose conflicts of interest and to decline handling or reviewing manuscripts for which they may have a conflict of interest. The editors and reviewers of this article have no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

This study was funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (grant No. 1U01HL116383-01); The Canadian Institutes of Health Research (grant No. 126113), Ottawa, Ontario, Canada; Comité National de la Recherche Clinique, Département de la Recherche Clinique et du Développement, Assistance Publique – Hôpitaux de Paris, Ministère des Solidarités, de la Santé et de la Famille, France; Ministère des Affaires Sociales et de la Santé, Paris, France (PHRC 14-0390); Ministère de la Santé et des Services Sociaux de la Province de Québec; The Department of Pediatrics, Washington University in St Louis, St Louis, Mo; and Women and Children's Health Research Institute, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada.

Appendix 1

Table E1.

Institutions, Age of Blood in Children in Pediatric Intensive Care Unit (ABC-PICU) site investigators, and coordinators for the sites included in cardiac surgery secondary analysis (investigators and study coordinators for the original study and cardiac surgery secondary analysis are provided in separate columns)

| List of sites that reported the inclusion of cardiac surgery patients in the original study | ABC-PICU original study: Investigators and study coordinators | ABC-PICU cardiac surgery secondary analysis: Investigators and study coordinators |

|---|---|---|

| Sainte-Justine University Hospital | Guillaume Émeriaud, Nancy Robitaille, Joannie Blanchette, Adnan Haj-Moustafa, Daniel Vincent, Vincent Laguë, Mariana Dumitrascu, Mary-Ellen French, Djouher Nait-Ladjemil, Ali Ghamraoui, Isabelle Grisoni, Kahina Bensaadi, Anne-Marie Girouard | Sophie Martin, Lucy Clayton, Émilie Laforest, Thierry Ducruet, Nancy Poirier, Jacques Lacroix, Marisa Tucci |

| Stollery Children's Hospital | Gonzalo Guerra, Susan Nahirniak, Jodie deMoissac, Rosalyn Doepker | Gonzalo Guerra, Cathy Sheppard, Darren H. Freed, V. Ben Sivarajan |

| St-Louis (US) | Philip C. Spinella, Allan Doctor, Ken Schechtman, Tina Bockelmann, Stephanie Schafer | Philip C. Spinella, Amila Tutundzic |

| Missouri - Washington University - St. Louis – Kenneth E Remyand Jason Steibel | ||

| Minnesota - University of Minnesota (US) | Marie Steiner, Dan Nerheim and Nicole Dodge Zantek | Marie Steiner, Lexie Goertzen |

| Illinois - Lurie (US) | Lauren Marsillio and Avani Shukla | |

| Virginia - University of Virginia Children's Hospital (US) | Michelle Adu-Darko, Gary Fang and James Gorham | |

| Wisconsin - Children's Hospital and Health System | Sheila Hanson MD, Katherine Woods and Rowena C. Punzalan | |

| Sheba Medical Center (Israel) | Marianne Nellis, (country principal investigator), Tselia Levy, Gideon Paret, Amir Vardi |

| Networks and groups | Network or group leader |

|---|---|

| Canadian Critical Care Trials Group https://www.ccctg.ca/ | Rob Fowler rob.fowler@sunnybrook.ca |

| Pediatric Acute Lung Injury and Sepsis Investigators (PALISI) Network https://www.palisi.org/ | Neal Thomas nthomas@pennstatehealth.psu.edu |

| BloodNet Pediatric Critical Care Blood Research Network https://www.bloodnetresearch.org/ |

Oliver Karam oliver.karam@yale.edu |

| Groupe Francophone de Réanimation et Urgences Pédiatriques https://gfrup.sfpediatrie.com/ |

Javouhey Étienne etienne.javouhey@chu-lyon.fr |

Table E2.

| Outcome | Red blood cell group |

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fresh | Standard-issue | ||

| 28 ICU-free days‡ | |||

| Median (IQR) | 24.1 (19.8-26.0) | 24.8 (22.0-25.9) | .35 |

| Mean (SD) | 20.6 ± 8.4 [n = 89] | 23.0 ± 5.0 [n = 88] | |

| 28 Mechanical ventilation-free days§ | |||

| Median (IQR) | 27.6 (24.4-27.9) | 27.6 (26.1-27.9) | .30 |

| Mean (SD) | 24.1 ± 7.7 [n = 88] | 25.7 ± 4.6 [n = 87] | |

| Worst daily PELOD-2 score‖ | |||

| Median (IQR) | 5 (3-8) | 4 (2-6) | .12 |

| Mean (SD) | 5.8 ± 5.3 [n = 89] | 4.5 ± 2.7 [n = 88] | |

| Length of hospital stay (d) | |||

| Median (IQR) | 6.6 (4.7-12.6) | 6.7 (4.7-14.6) | .75 |

| Mean (SD) | 17.3 ± 25.4 | 14.2 ± 20.7 | |

ICU, Intensive care unit; PELOD-2, Pediatric logistic organ dysfunction-2 score.

Values in square brackets indicate number of patients analyzed among all participants.

We chose to present both means and medians. However, as normality is not verified, non-parametric test are most appropriate.

Calculated by subtracting the actual ICU length of stay in days from 28. If a patient died within 28 days or stayed in ICU for more than 28 days after randomization, 28 ICU-free days were reported as 0.

Calculated by subtracting from 28 the number of days spent receiving mechanical ventilation. If the patient died within 28 days or required mechanical ventilation for more than 28 days after randomization, 28 mechanical ventilation-free days were reported as 0.

Defined by Leteurtre and colleagues.19 The score ranges from 0 to 33; higher scores indicate greater severity of multiple organ dysfunction syndrome. The score can be estimated over the entire stay in the ICU or over 1 days (daily PELOD-2).

References

- 1.Spinella P.C., Dressler A., Tucci M., Carroll C.L., Rosen R.S., Hume H., et al. Survey of transfusion policies at US and Canadian children’s hospitals in 2008 and 2009. Transfusion. 2010;50:2328–2335. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2010.02708.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Flegel W.A., Natanson C., Klein H.G. Does prolonged storage of red blood cells cause harm? Br J Haematol. 2014;165:3–16. doi: 10.1111/bjh.12747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Spinella P.C., Tucci M., Fergusson D.A., Lacroix J., Hébert P.C., Leteurtre S., et al. Effect of fresh vs standard-issue red blood cell transfusions on multiple organ dysfunction syndrome in critically ill pediatric patients: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2019;322:2179–2190. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.17478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fergusson D.A., Hébert P., Hogan D.L., LeBel L., Rouvinez-Bouali N., Smyth J.A., et al. Effect of fresh red blood cell transfusions on clinical outcomes in premature, very low-birth-weight infants: the ARIPI randomized trial. JAMA. 2012;308:1443–1451. doi: 10.1001/2012.jama.11953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dhabangi A., Ainomugisha B., Cserti-Gazdewich C., Ddungu H., Kyeyune D., Musisi E., et al. Effect of transfusion of red blood cells with longer vs shorter storage duration on elevated blood lactate levels in children with severe anemia: the TOTAL randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2015;314:2514–2523. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.13977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cholette J.M., Willems A., Valentine S.L., Bateman S.T., Schwartz S.M. Recommendations on RBC transfusion in infants and children with acquired and congenital heart disease from the pediatric critical care transfusion and anemia expertise initiative. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2018;19:S137–S148. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0000000000001603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baltsavias I., Faraoni D., Willems A., El Kenz H., Melot C., De Hert S., et al. Blood storage duration and morbidity and mortality in children undergoing cardiac surgery. A retrospective analysis. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2014;31:310–316. doi: 10.1097/EJA.0000000000000024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kawase H., Egi M., Kanazawa T., Shimizu K., Toda Y., Iwasaki T., et al. Storage duration of transfused red blood cells is not significantly associated with postoperative adverse events in pediatric cardiac surgery patients. Transfus Apher Sci. 2016;54:111–116. doi: 10.1016/j.transci.2016.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bishnoi A.K., Garg P., Patel K., Ananthanarayanan C., Shah R., Solanki A., et al. Effect of red blood cell storage duration on outcome after paediatric cardiac surgery: a prospective observational study. Heart Lung Circ. 2019;28:784–791. doi: 10.1016/j.hlc.2018.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cholette J.M., Pietropaoli A.P., Henrichs K.F., Alfieris G.M., Powers K.S., Phipps R., et al. Longer RBC storage duration is associated with increased postoperative infections in pediatric cardiac surgery. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2015;16:227–235. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0000000000000320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Manlhiot C., McCrindle B.W., Menjak I.B., Yoon H., Holtby H.M., Brandão L.R., et al. Longer blood storage is associated with suboptimal outcomes in high-risk pediatric cardiac surgery. Ann Thorac Surg. 2012;93:1563–1569. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2011.08.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Steiner M.E., Ness P.M., Assmann S.F., Triulzi D.J., Sloan S.R., Delaney M., et al. Effects of red-cell storage duration on patients undergoing cardiac surgery. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1419–1429. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1414219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Koch C.G., Sessler D.I., Duncan A.E., Mascha E.J., Li L., Yang D., et al. Effect of red blood cell storage duration on major postoperative complications in cardiac surgery: a randomized trial. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2020;160:1505–1514.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2019.09.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heddle N.M., Cook R.J., Arnold D.M., Liu Y., Barty R., Crowther M.A., et al. Effect of short-term vs. long-term blood storage on mortality after transfusion. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:1937–1945. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1609014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tucci M., Lacroix J., Fergusson D., Doctor A., Hébert P., Berg R.A., et al. The age of blood in pediatric intensive care units (ABC PICU): study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2018;19:404. doi: 10.1186/s13063-018-2809-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lacroix J., Hébert P., Fergusson D., Tinmouth A., Blajchman M.A., Callum J., et al. The Age of Blood Evaluation (ABLE) randomized controlled trial: study design. Transfus Med Rev. 2011;25:197–205. doi: 10.1016/j.tmrv.2011.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Proulx F., Fayon M., Farrell C.A., Lacroix J., Gauthier M. Epidemiology of sepsis and multiple organ dysfunction syndrome in children. Chest. 1996;109:1033–1037. doi: 10.1378/chest.109.4.1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lacroix J., Hébert P.C., Hutchison J.S., Hume H.A., Tucci M., Ducruet T., et al. Transfusion strategies for patients in pediatric intensive care units. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1609–1619. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa066240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leteurtre S., Duhamel A., Salleron J., Grandbastien B., Lacroix J., Leclerc F. PELOD-2: an update of the Pediatric Logistic Organ Dysfunction Score. Crit Care Med. 2013;41:1761–1773. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31828a2bbd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thomas N.J., Shaffer M.L., Willson D.F., Shih M.C., Curley M.A. Defining acute lung disease in children with the oxygenation saturation index. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2010;11:12–17. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0b013e3181b0653d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bernard G.R., Artigas A., Brigham K.L., Carlet J., Falke K., Hudson L., et al. The American-European Consensus Conference on ARDS. Definitions, mechanisms, relevant outcomes, and clinical trial coordination. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1994;149:818–824. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.149.3.7509706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gaies M.G., Gurney J.G., Yen A.H., Napoli M.L., Gajarski R.J., Ohye R.G., et al. Vasoactive-inotropic score as a predictor of morbidity and mortality in infants after cardiopulmonary bypass. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2010;11:234–238. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0b013e3181b806fc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.O'Brien S.M., Clarke D.R., Jacobs J.P., Jacobs M.L., Lacour-Gayet F.G., Pizarro C., et al. An empirically based tool for analyzing mortality associated with congenital heart surgery. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2009;138:1139–1153. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2009.03.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goldstein B., Giroir B., Randolph A. International Consensus Conference on Pediatric Sepsis. International Pediatric Sepsis Consensus Conference: definitions for sepsis and organ dysfunction in pediatrics. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2005;6:2–8. doi: 10.1097/01.PCC.0000149131.72248.E6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lacroix J., Gauvin F., Skippen P., Cox P., Langley J.M., Matlow A.G. Nosocomial infections in the pediatric intensive care unit: epidemiology and control. Pediatr Crit Care. 2006;103:1394–1421. [Google Scholar]

- 26.CDC definitions for nosocomial infections, 1988. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1989;139:1058–1059. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/139.4.1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Calandra T., Cohen J. International Sepsis Forum definition of infection in the ICUCC. The International Sepsis Forum Consensus Conference on definitions of infection in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2005;33:1538–1548. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000168253.91200.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cooper D.J., McQuilten Z.K., Nichol A., Ady B., Aubron C., Bailey M., et al. Age of red cells for transfusion and outcomes in critically ill adults. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:1858–1867. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1707572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Redlin M., Habazettl H., Schoenfeld H., Kukucka M., Boettcher W., Kuppe H., et al. Red blood cell storage duration is associated with various clinical outcomes in pediatric cardiac surgery. Transfus Med Hemother. 2014;41:146–151. doi: 10.1159/000357998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ranucci M., Carlucci C., Isgrò G., Boncilli A., De Benedetti D., De la Torre T., et al. Duration of red blood cell storage and outcomes in pediatric cardiac surgery: an association found for pump prime blood. Crit Care. 2009;13:R207. doi: 10.1186/cc8217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cholette JM, Henrichs KF, Alfieris GM, Powers K.S., Phipps R., Spinelli S.L., et al. Washing red blood cells and platelets transfused in cardiac surgery reduces postoperative inflammation and number of transfusions: results of a prospective, randomized, controlled clinical trial. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2012;13:290–299. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0b013e31822f173c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Alexander P.E., Barty R., Fei Y., Vandvik P.O., Pai M., Siemieniuk R.A., et al. Transfusion of fresher vs older red blood cells in hospitalized patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Blood. 2016;127:400–410. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-09-670950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]