Abstract

To build on the existing data on the pattern of myosin heavy chain (MyHC) isoforms expression in the human muscle spindles, we aimed to verify whether the ‘novel’ MyHC‐15, ‐2x and ‐2b isoforms are co‐expressed with the other known isoforms in the human intrafusal fibres. Using a set of antibodies, we attempted to demonstrate nine isoforms (15, slow‐tonic, 1, α, 2a, 2x, 2b, embryonic, neonatal) in different regions of intrafusal fibres in the biceps brachii and flexor digitorum profundus muscles. The reactivity of some antibodies with the extrafusal fibres was also tested in the masseter and laryngeal cricothyreoid muscles. In both upper limb muscles, the expression of slow‐tonic isoform was a reliable marker for differentiating positive bag fibres from negative chain fibres. Generally, bag1 and bag2 fibres were distinguished in isoform 1 expression; the latter consistently expressed this isoform over their entire length. Although isoform 15 was not abundantly expressed in intrafusal fibres, its expression was pronounced in the extracapsular region of bag fibres. Using a 2x isoform‐specific antibody, this isoform was demonstrated in the intracapsular regions of some intrafusal fibres, particularly chain fibres. To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to demonstrate 15 and 2x isoforms in human intrafusal fibres. However, whether the labelling with an antibody specific for rat 2b isoform reflects the expression of this isoform in bag fibres and some extrafusal ones in the specialised cranial muscles requires further evaluation. The revealed pattern of isoform co‐expression only partially agrees with the results of previous, more extensive studies. Nevertheless, it may be inferred that MyHC isoform expression in intrafusal fibres varies along their length, across different muscle spindles and muscles. Furthermore, the estimation of expression may also depend on the antibodies utilised, which may also react differently with intrafusal and extrafusal fibres.

Keywords: immunohistochemistry, intrafusal fibre, muscle spindle, myosin heavy chain isoforms (MyHC), skeletal muscle

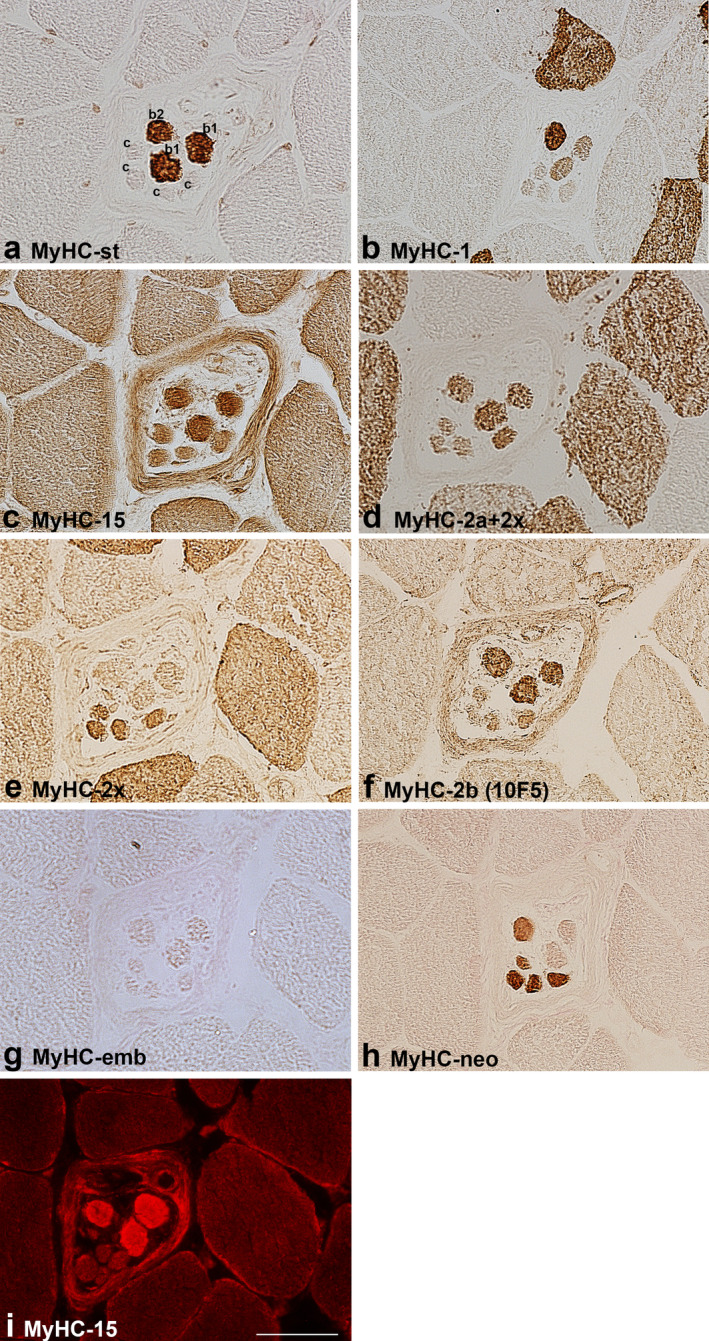

Myosin heavy chain (MyHC) isoforms expression in bag1 (b1), bag2 (b2) and chain (c) fibres of a muscle spindle in human flexor digitorum profundus was analysed. In addition to previously demonstrated MyHC‐slow‐tonic (st), ‐1, ‐α, ‐2a, embryonic (emb) and ‐neonatal (neo), MyHC‐15 and ‐2x isoforms were also demonstrated. Note that the antibody specific to rat MyHC‐2b also labelled bag fibres.

1. INTRODUCTION

Muscle spindles are sensory receptors composed of small encapsulated intrafusal fibres embedded in larger extrafusal ones. They detect changes in the length and stretch of extrafusal fibres through their afferent nerves and convey the proprioceptive information to the central nervous system, which regulates the contraction of extrafusal and intrafusal fibres through their α and γ motor neurons respectively. Thus, muscle spindles are essential for effective locomotion and posture control (Walro & Kucera, 1999). Muscle spindles are most abundant in axial muscles, including those involved in head movements, whereas they are less abundant in distal muscles of the upper extremities than in proximal ones (Banks, 2006).

Banks and Barker (2004) divided muscle spindles into three regions: A, B and C. The first two regions are encapsulated. The A region includes the central equatorial and the peripheral juxta‐equatorial regions, from which the B region or polar zone extends peripherally. In the A region, there are accumulations of intrafusal fibre nuclei and sensory nerve endings. The B‐encapsulated region contains motor nerve endings. The C region is the extracapsular portion of a muscle spindle where intrafusal and extrafusal fibres merge.

Intrafusal fibres are divided into larger bag fibres with nuclei accumulated in a nuclear ‘bag’ and smaller chain fibres with nuclei aligned longitudinally in a ‘chain’ in the equatorial region (Matthews, 1964). Intrafusal fibres have been further differentiated according to their staining characteristics following histochemical reaction for myofibrillar ATPase (mATPase) after alkaline (pH 10.4) and acid (pH 4.6 and 4.3) preincubations (Eriksson & Thornell, 1990; Kucera et al., 1978; Österlund et al., 2011, 2013; Ovalle & Smith, 1972). However, differences in the staining pattern were present along the fibres. Furthermore, the number of intrafusal fibres varied not only across different muscle spindles but across the different muscles and with age (Liu et al., 2003; Thornell et al., 2015). Since the reaction for mATPase only reflects the content of myosin heavy chain (MyHC) isoforms, which are the primary determinant of fibre contractile characteristics, the pattern of MyHC isoforms expression in intrafusal fibres has been examined in more recent studies (Liu et al., 2002, 2003, 2005; Österlund et al., 2013).

In vertebrates, MyHC isoforms are encoded by 11 sarcomeric myosin heavy chain (MYH) genes, which exhibit very high amino acid sequence identity (Lee et al., 2019). Two cardiac MYH genes code for MyHC‐α (MYH6) and MyHC‐β or ‐1 (MYH7) (Saez et al., 1987; Weiss, McDonough, et al., 1999; Weiss, Schiaffino, et al., 1999). While MyHC‐α is expressed in the atrial myocardium, specialised craniofacial muscles (masticatory, extraocular and laryngeal muscles) and intrafusal fibres, MyHC‐1 is expressed in the ventricular myocardium and slow or type 1 extrafusal fibres. A cluster of six MYH genes encodes the following MyHC isoforms: ‐embryonic (MYH3), ‐2a (MYH2), ‐2x (MYH1), ‐2b (MYH4), ‐neonatal/perinatal/ (MYH8) and ‐extraocular (MYH13). MyHC‐2a and ‐2x isoforms are expressed in the fast extrafusal type 2a and 2x fibres respectively. MyHC‐2b was not detected in large human skeletal muscles (Ennion et al., 1995; Smerdu & Eržen, 2001; Smerdu et al., 1994), but since the antibody specific for rat MyHC‐2b labelled some fibres, it was assumed to be weakly expressed in the extraocular and some laryngeal muscles (Mascarello et al., 2016; Smerdu & Cvetko, 2013; Stirn Kranjc et al., 2009). MyHC‐embryonic (MyHC‐emb) and MyHC‐neonatal/perinatal (MyHC‐neo) are predominantly expressed in developing muscles and more scarcely in the mature regenerating muscles, specialised cranial muscles and intrafusal fibres (Schiaffino et al., 2015). MyHC‐extraocular is expressed in the extraocular muscles (Mascarello et al., 2016; Stirn Kranjc et al., 2009; Wieczorek et al., 1985).

Besides these eight genes, three more ancient MYH genes, namely MYH7b (initially termed MYH14), MYH15 and MYH16, have been recently detected in separate chromosomes (Desjardins et al., 2002). MYH16, which encodes the masticatory MyHC isoform of some vertebrates, especially carnivores, has been lost in humans due to a frameshift mutation (Stedman et al., 2004; Toniolo et al., 2008). MYH7b gene codes for the slow‐tonic MyHC (MyHC‐st), evolutionarily the second most ancient isoform (Lee et al., 2019; Rossi et al., 2010). Previously, MyHC‐st was immunohistochemically demonstrated in avian skeletal muscles (Bormioli et al., 1979; Pierobon Bormioli et al., 1980; Sokoloff et al., 2007). As MyHC‐st shows the highest sequence homology to both cardiac MyHC isoforms, it was initially described as slow A (Desjardins et al., 2002; Lee et al., 2019). The expression of MyHC‐st was demonstrated in the extraocular and laryngeal muscles and intrafusal fibres (Liu et al., 2002; Mascarello et al., 2016; Pierobon Bormioli et al., 1980; Rossi et al., 2010). Multiple motor end plate innervation and prolonged contractions are characteristic of fibres expressing MyHC‐st (Banks, 2015).

MYH15 is an orthologue of the gene, which is expressed in the heart and so‐called ‘conventional’ skeletal muscles of birds, snakes and various mammals (Lee et al., 2019). As the corresponding isoform shows similarity to cardiac isoforms, it was initially addressed as slow B (Desjardins et al., 2002; Lee et al., 2019). It was found to be expressed in the orbital layer of rat extraocular muscles and the extracapsular region of some rat bag fibres (Rossi et al., 2010). In humans, MyHC‐15 has been demonstrated in some extraocular muscles (Mascarello et al., 2016).

Intrafusal fibres were shown to co‐express several MyHC isoforms, with their expression pattern varying along the fibre length, across different muscles and with age (Liu et al., 2002, 2003, 2005; Österlund et al., 2013; Thornell et al., 2015). Bag1 fibres generally express MyHC‐st over their entire length. In the A region, they strongly express MyHC‐α but weakly to moderately express MyHC‐1 in the B and C regions respectively. Bag1 fibres may also weakly express developmental MyHC isoforms. Bag2 fibres co‐express MyHC‐st and ‐1 over their entire length except for the equatorial region; in the A region, MyHC‐α is also expressed. Chain fibres were mostly positive for antibodies specific for fast and developmental MyHC isoforms. The reports about fast MyHC‐2a and ‐2x isoforms expression were particularly controversial. Namely, two antibodies considered specific for MyHC‐2a were used, but in our experience, they label both human fast MyHC isoforms (Meznaric & Čarni, 2020; Meznaric et al., 2018; Smerdu & Soukup, 2008). To demonstrate MyHC‐2x, the antibody which labels MyHC‐1 and ‐2a, but not ‐2x was used. However, since several MyHC isoforms co‐expression is characteristic of intrafusal fibres, this antibody is not useful for studying muscle spindles.

Thus, despite several detailed past studies, the analysis of the ‘novel’ MyHC‐15 and a clear assessment of fast MyHC isoforms expression in human intrafusal fibres remains to be accomplished. Hence, the main aim of this study was to determine whether the MyHC‐15 isoform, demonstrated in the extracapsular region of some rat bag fibres (Rossi et al., 2010), is also expressed in human intrafusal fibres. Second, we aimed to determine whether MyHC‐2x is expressed in human intrafusal fibres, to the best of our knowledge, for the first time using an antibody exclusively specific for this isoform. Third, since an antibody specific for rat MyHC‐2b labelled some extrafusal fibres in the specialised cranial muscles, we aimed to verify whether this antibody also labels intrafusal fibres and potentially suggests MyHC‐2b expression. The fourth goal was to demonstrate the pattern of MyHC isoform co‐expressions in intrafusal fibres.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Muscle samples

Samples from upper limb muscles of presumably healthy male subjects who suffered sudden death were analysed. Three samples of biceps brachii (BB) were obtained from 21‐, 41‐ and 63‐year‐old male subjects, and one sample of flexor digitorum profundus (FDP) was obtained from the 21‐year‐old male subject. To test a potential cross‐reactivity of some antibodies, an immunohistochemical reaction was also performed on samples of the masseter muscle from 24‐ and 32‐year‐old male subjects and a sample of the laryngeal cricothyreoideus muscle of a 59‐year‐old male subject. The samples were excised at autopsy within 12 h post‐mortem. The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and the human muscle sampling was approved by the National Medical Ethics Committee of the Republic of Slovenia (No. 36/04/08). The muscle samples were frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C until the preparation of serial cryosections (5 μm).

2.2. Immunohistochemistry

The first serial muscle cryosection was labelled with haematoxylin‐eosin to identify muscle spindles (Dubowitz, 1985). Next, the MyHC isoform expression was demonstrated with a set of antibodies, whose specificity, dilutions used, and research resource identifiers (RRIDs) or source are shown in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Antibodies, their specificity and dilutions used to demonstrate MyHC isoforms in human intrafusal fibres.

| Antibody | MyHC specificity | Dilution | Research resource identifier (RRID)/source |

|---|---|---|---|

| BA‐D5 | MyHC‐1/β (cardiac) | 1:200 | DSHB Cat# BA‐D5, RRID:AB_2235587 |

| BA‐G5 | MyHC‐α (cardiac) | 1:100 | Abcam Cat# ab50967, RRID:AB_942084 |

| MYH6 | MyHC‐α (cardiac) | 1:2500–5000 | Sigma‐Aldrich Cat# HPA001349, RRID:AB_1079437 |

| MYH14 | MyHC‐slow‐tonic | 1:100 | (Rossi et al., 2010) |

| MYH15 | MyHC‐15 | 1:100–400 | (Rossi et al., 2010) |

| SC‐71 | MyHC‐2a+2x a | 1:100 | DSHB Cat# SC‐71, RRID:AB_2147165 |

| 6H1 | MyHC‐2x | 1:50 | DSHB Cat# 6H1, RRID:AB_1157897 |

| 10F5 | MyHC‐2b (rat) | 1:20 | DSHB Cat# 14J4, RRID:AB_2314829 |

| BF‐F3 | MyHC‐2b (rat) | 1:20 | DSHB Cat# BF‐F3, RRID:AB_2266724 |

| NCL MHCd | MyHC‐embryonic | 1:20 | Leica Biosystems Cat# NCL‐MHCd, RRID:AB_563901 |

| NCL MHCn | MyHC‐neonatal | 1:10 | Leica Biosystems Cat# NCL‐MHCn, RRID:AB_563900 |

Intensive staining of MyHC‐2a and moderate of MyHC‐2x in human muscles.

Two rabbit polyclonal antibodies, MYH14 and MYH15, donated by Schiaffino and co‐workers (Rossi et al., 2010), were used to demonstrate the expression of MyHC‐st and MyHC‐15 isoforms respectively.

Antibody BA‐D5 was used to demonstrate MyHC‐1, whereas two antibodies, BA‐G5 and MYH6, were used to demonstrate MyHC‐α. BA‐G5 (Rudnicki et al., 1990) was either donated by Schiaffino or purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, UK), and MYH6 was purchased from Sigma‐Aldrich (USA, produced in Sweden).

To demonstrate the expression of fast MyHC isoforms, four antibodies specific for rat fast MyHC were used: SC‐71, 6H1, 10F5 and BF‐F3 (Lucas et al., 2000; Schiaffino, 1986). It should be noted that according to our experience, antibody SC‐71, specific for rat MyHC‐2a, intensively stains human 2a and moderately 2x extrafusal fibres (MyHC‐2a+2x). Antibody 6H1 is specific for rat and human MyHC‐2x (Meznaric & Čarni, 2020; Smerdu & Soukup, 2008). However, antibodies 10F5 and BF‐F3, both specific for rat MyHC‐2b, do not label human extrafusal fibres in limb muscles (Smerdu & Cvetko, 2013).

The supernatants of BA‐D5, SC‐71 and BF‐F3 antibodies were produced in the local laboratory (Blood Transfusion Centre of Slovenia, Ljubljana, Slovenia) from corresponding cell lines provided by Deutsche Sammlung von Mikroorganismen und Zellkulturen (DSMZ, Braunschweig, Germany), while those of 6H1 and 10F5 were purchased from Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank (DSHB, University of Iowa, USA).

MyHC‐emb and MyHC‐neo isoforms were demonstrated by antibodies NCL MHCd and NCL MHCn, respectively (Ecob‐Prince et al., 1989), both purchased from Leica Biosystems Newcastle Ltd (Newcastle Upon Tyne, UK).

The muscle sections were preincubated either in the phosphate‐buffered saline (PBS) containing 0.5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) and 2% goat serum (MYH14 and MYH15) or in PBS/BSA containing 2.5% rabbit serum (the rest of antibodies used) for 30 min. The appropriate dilutions of antibodies with PBS/BSA were determined. The sections were incubated with the primary antibody in a humidified box overnight at 4°C. As a control for each set of the analysed samples, a slide with serial sections was simultaneously incubated in PBS/BSA without a primary antibody. The reactivity of antibodies was mostly revealed by horseradish peroxidase‐conjugated secondary antibody (PO260, Dako, Denmark), diluted (1:100) in PBS/BSA, containing 2.5% rabbit serum. To reveal the secondary antibody binding, the sections were incubated in 0.05% diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride hydrate and 0.01% H2O2 in 0.2 M acetate buffer (pH 5.2) for approximately 7 min in the dark (Gorza, 1990; Smerdu & Soukup, 2008). Since antibody 6H1 only weakly stains fibres, its binding was demonstrated using NovoLink Polymer Detection System, following the producer's instructions (Leica Biosystems, Newcastle, UK). The control sections were incubated with the secondary antibody or NovoLink Polymer Detection System. In some samples, the binding of MYH14 and MYH15 was also revealed by immunofluorescence technique, using goat anti‐rabbit secondary antibody (1:200), conjugated with Alexa Fluor 594 (Jackson ImmunoResearch).

2.3. Muscle spindles analysis

An individual muscle spindle was identified in consecutive serial muscle sections, stained with different antibodies for MyHC isoforms. The images of muscle spindles were captured by the digital camera (Kern, Germany) connected to the Eclipse E80i microscope (Nikon). MyHC isoform expression was analysed in different regions of muscle spindles (A, B and C), depending on how they appeared in muscle cross‐section. However, the B region was the optimum for the analysis. A total of six muscle spindles were analysed, four in three human BB muscle samples and two in the FDP sample. The staining intensity of intrafusal fibres with different antibodies was estimated and accordingly classified into four categories: intensively stained (++), moderately stained (+), weakly stained (±) and unstained (−) (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Staining pattern of human intrafusal bag1, bag2 and chain fibres by antibodies against MyHC isoforms (slow‐tonic [st], 1, α, 2a, 2x, 2b, 15, embryonic [emb] and neonatal [neo]) in different regions (A, B, C) of muscle spindles in biceps brachii and flexor digitorum profundus muscles.

| m. biceps brachii (21 years) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A region | B region | C region | ||||

| bag1 | bag2 | chain | bag1 | bag2 | chain | |

| ++st | ++st | ++st | ++st | |||

| ++1 | +1 | ++1 | +/−1 | |||

| ±α | ±α | ±α | ±α | ±α | ||

| ++2a+2x | ++2a+2x | ++2a+2x | ++2a+2x | ++2a+2x | ++/+2a+2x | |

| +2x | +2x | +2x | +2x | +2x | ||

| ++2b | ++2b | ++2b | ++2b | |||

| +15 | +15 | +15 | +15 | +15 | +15 | |

| +emb | +emb | +emb | ||||

| +neo | ++neo | |||||

| m. biceps brachii (41 years) | ||||||

| bag1 | bag2 | chain | bag | |||

| ++st | ++st | ++st | ||||

| +1/− | ++1 | +1 | ||||

| ±α | ±α | ±α | ||||

| ++2a+2x | ++2a+2x | ++2a+2x | ++/±2a+2x | |||

| +/−2x | ||||||

| +2b | +2b | |||||

| +15 | +15 | +15 | ++15 | |||

| ++emb | ||||||

| ++neo | ||||||

| m. biceps brachii (63 years) | ||||||

| bag1 | bag2 | chain | bag1 | bag2 | chain | |

| ++st | ++st | ++st | ++st | |||

| ++1 | +/−1 | ++1 | ||||

| ±/−α | ±α | ±α | ±α | ±α | ||

| ++2a+2x | ++2a+2x | ++/+2a+2x | +2a+2x | +2a+2x | +/±2a+2x | |

| +2x | +2x | +2x | +2x | +/±2x | ++/±2x | |

| ++2b | ++2b | +±2b | ++2b | ++2b | +/±/−2b | |

| +15 | +15 | ±15 | +15 | +15 | +/±15 | |

| ±emb | ±emb | ±emb | ±emb | ±/+emb | ||

| +neo | ++neo | |||||

| m. flexor digitorum profundus (21 years) | ||||||

| bag1 | bag2 | chain | bag | |||

| ++st | ++st | ++st | ||||

| +1 | ++1 | ++1 | ||||

| ±α | ±α | ±α | ±2a+2x | |||

| ++2a+2x | ++2a+2x | ++/+2a+2x | ||||

| ++2x | ||||||

| ++/±2b | ++/±2b | ±/−2b | +2b | |||

| +15 | +15 | ±/15 | ++15 | |||

| ±emb | ±emb | |||||

| ++neo | ++neo | |||||

Note: The intrafusal fibres were classified to four categories according to the estimated staining intensity: intensively stained (++), moderately stained (+), weakly stained (±) and unstained (−). Completely negative results are not presented. It should be noted that the presented staining for MyHC‐2b does not confirm the expression of this isoform in the intrafusal fibres.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Intrafusal fibres classification

In BB of the young subject, a muscle spindle in the A and proximal and distal B regions was analysed (Figure 1). In BB of the middle‐aged subject, a muscle spindle in B and C regions was analysed (Figures 2 and 3). In the older subject, two muscle spindles were analysed in BB: one in the A and distal B regions and the other in the proximal B region only (Figure 4). In the FDP of the young subject, two muscle spindles were analysed, both in the proximal B region (Figure 5) and one of them in the C region as well.

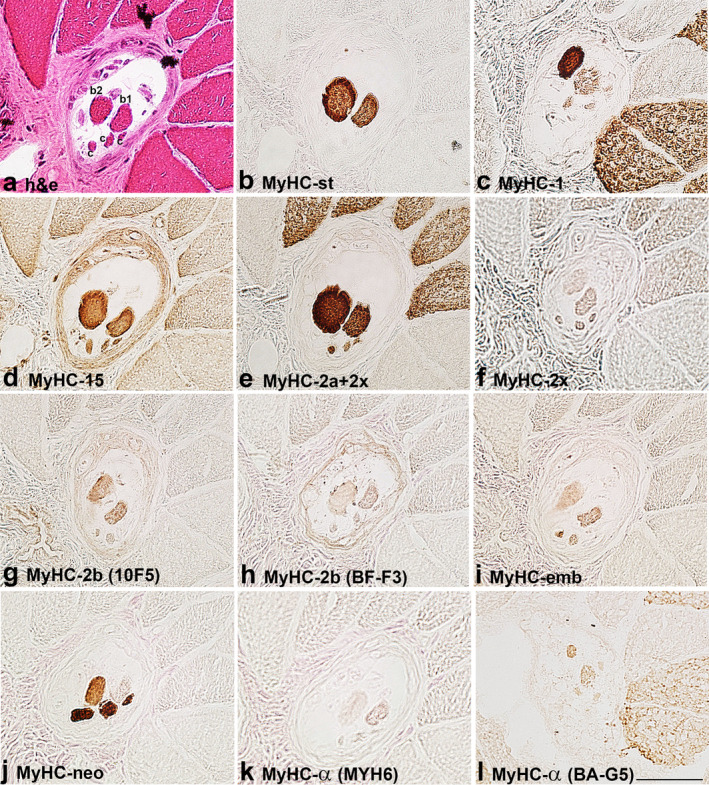

FIGURE 1.

MyHC isoform expression in the B region of a muscle spindle in the biceps brachii of a 21‐year‐old patient. The muscle sections are labelled by: a. hematoxylin‐eosin staining (h & e) and antibodies specific for: b. MyHC‐st, c. MyHC‐1, d. MyHC‐15, e. MyHC‐2a+2x, f. MyHC‐2x, g. MyHC‐2b (10F5), h. MyHC‐2b (BF‐F3), i. MyHC‐emb, j. MyHC‐neo, k. MyHC‐α (MYH6) and l. MyHC‐α (BA‐G5). In a. intrafusal bag1 (b1), bag2 (b2) and chain (c), fibres are labelled. Scale bar: 50 μm.

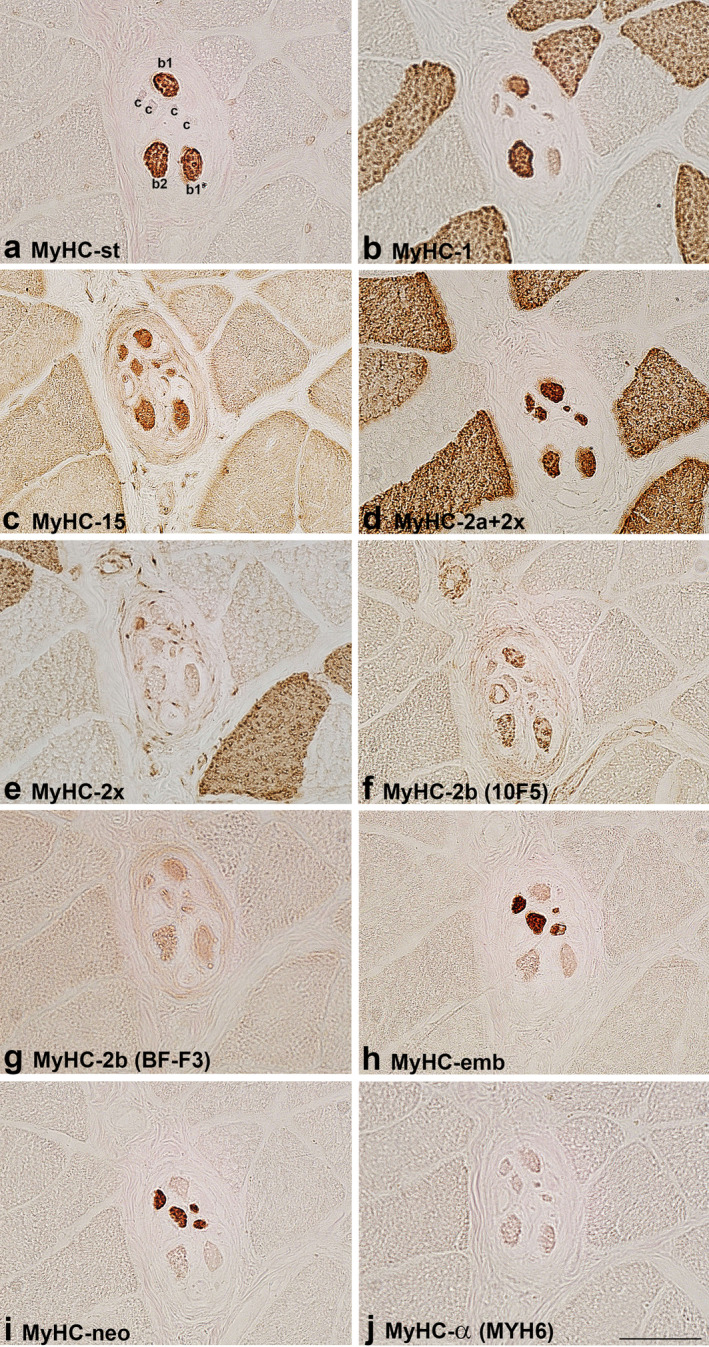

FIGURE 2.

MyHC isoform expression in the B region of a muscle spindle in the biceps brachii of a 41‐year‐old patient. The muscle sections are labelled by antibodies specific for: a. MyHC‐st, b. MyHC‐1, c. MyHC‐15, d. MyHC‐2a+2x, e. MyHC‐2x, f. MyHC‐2b (10F5), g. MyHC‐2b (BF‐F3), h. MyHC‐emb, i. MyHC‐neo and j. MyHC‐α (MYH6). In a. intrafusal bag1 (b1), bag2 (b2) and chain (c), fibres are labelled. Scale bar: 50 μm.

FIGURE 3.

MyHC isoform expression in the C region of bag fibres in the biceps brachii of a 41‐year‐old patient. The muscle sections are labelled by antibodies specific for: a. MyHC‐st, b. MyHC‐2b (10F5), c. MyHC‐15 and d. MyHC‐2a+2x. In a. two bag (b), fibres are labelled. Note that both bag fibres express MyHC‐15. Scale bar: 50 μm.

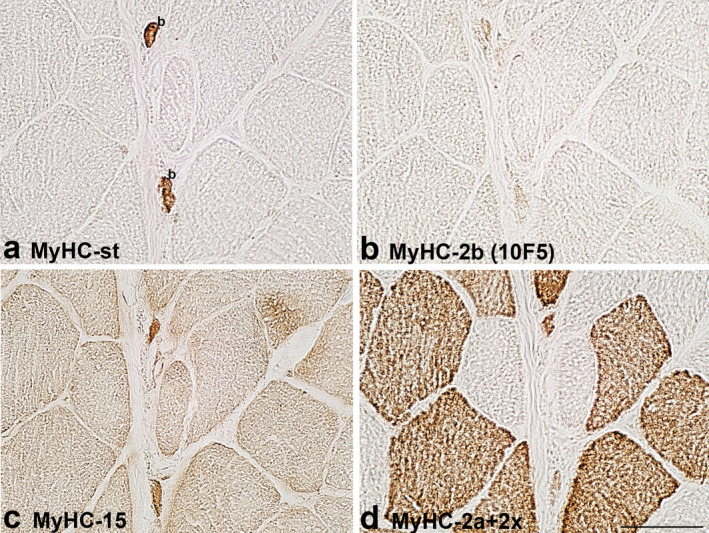

FIGURE 4.

MyHC isoform expression in the B region of a muscle spindle in the biceps brachii of a 63‐year‐old patient. The muscle sections are labelled by antibodies specific for: a. MyHC‐st, b. MyHC‐1, c. MyHC‐15, d. MyHC‐2a+2x, e. MyHC‐2x, f. MyHC‐2b (10F5), g. MyHC‐emb, h. MyHC‐neo and i. MyHC‐α (BA‐G5). In a. intrafusal bag1 (b1), bag2 (b2) and chain (c), fibres are labelled. Scale bar: 50 μm.

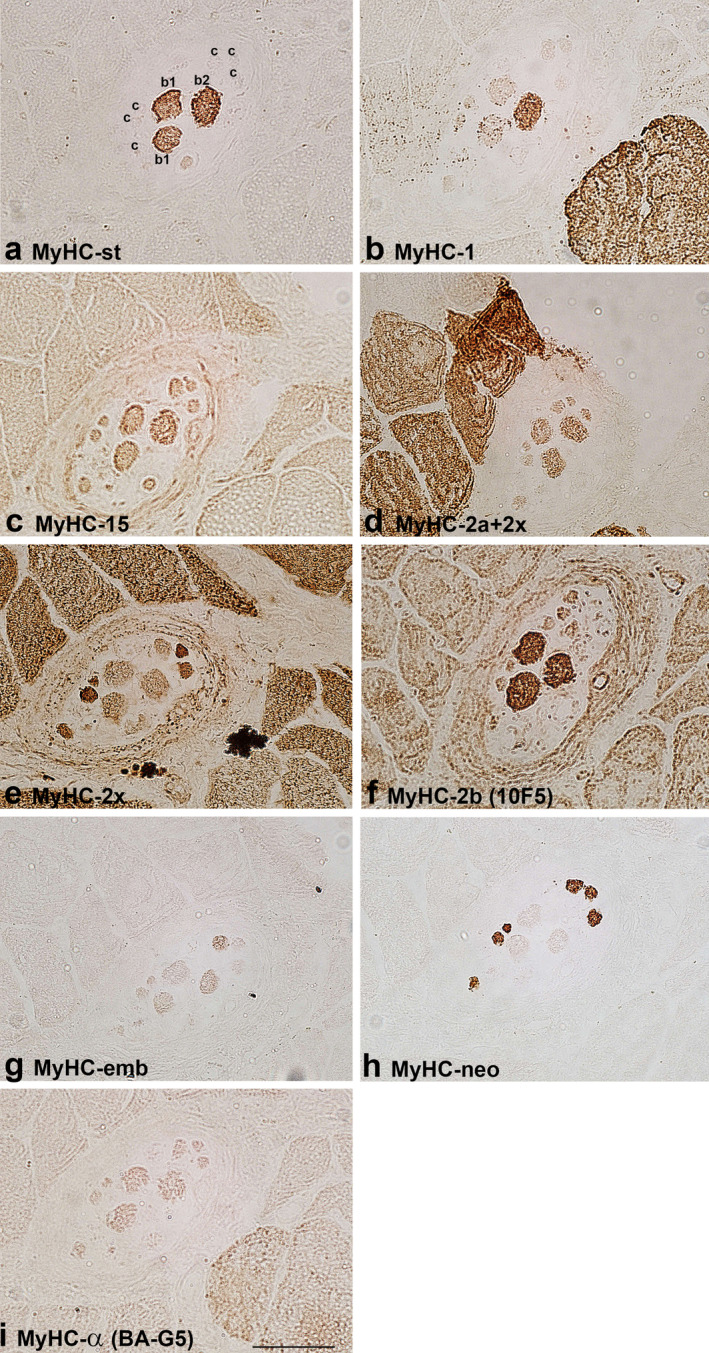

FIGURE 5.

MyHC isoform expression in the B region of a muscle spindle in the flexor digitorum profundus. The muscle sections are labelled by antibodies specific for: a. MyHC‐st, b. MyHC‐1, c. MyHC‐15, d. MyHC‐2a+2x, e. MyHC‐2x, f. MyHC‐2b (10F5), g. MyHC‐emb, h. MyHC‐neo and i. MyHC‐15 (immunofluorescence). In a. intrafusal bag1 (b1), bag2 (b2) and chain (c) fibres are labelled. Scale bar: 50 μm.

Intrafusal fibres were classified according to the fibres' size and, more importantly, according to the previously reported pattern of MyHC isoform expression in intrafusal fibre types determined according to the histochemical reaction for mATPase after alkaline and acid preincubations (Eriksson & Thornell, 1990; Liu et al., 2002, 2003, 2005; Österlund et al., 2013).

The staining pattern of intrafusal fibres by antibodies for MyHC isoforms is presented in Table 2. The expression of MyHC‐st was a reliable marker to distinguish positive bag fibres from negative chain fibres in both human muscles. All bag2 fibres intensively expressed MyHC‐1, whereas only some bag1 fibres expressed this isoform in the B region in BB. In FDP, all bag1 fibres expressed this isoform either intensively or moderately. Bag fibres and most of the chain fibres were intensively labelled by antibody SC‐71 (MyHC‐2a+2x) except for the B region of a muscle spindle in BB of the older subject, indicating MyHC‐2a expression. On the other hand, moderately stained bag and chain fibres by SC‐71 were considered to express MyHC‐2x if they were also positive with antibody 6H1, specific for MyHC‐2x. Some of the bag and chain fibres were variably stained by one or both antibodies specific for developmental MyHC isoforms (MyHC‐emb and ‐neo), MyHC‐neo being more intensively expressed (Figures 1, 2, 4 and 5). In the B region of all analysed spindles, MyHC‐neo was intensively expressed in chain fibres and moderately or intensively in bag2 fibres in BB and FDP of the young subject respectively.

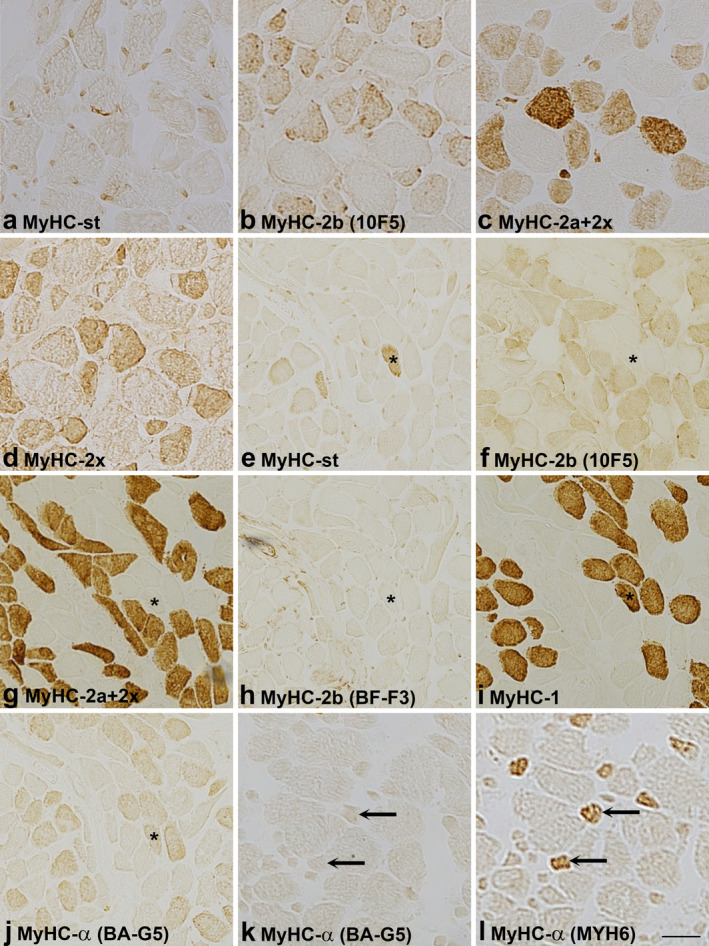

Two antibodies, either BA‐G5 or MYH6, or both, were employed to demonstrate MyHC‐α. BA‐G5 weakly labelled bag1 and bag2 fibres and cross‐reacted with MyHC‐1 in extrafusal fibres but its staining of intrafusal fibres differed from that of BA‐D5 (see Figures 1c,l and 4b,i). Both antibodies were tested in the masseter muscle, which is known to express MyHC‐α. MYH6 antibody intensively labelled some fibres, whereas BA‐G5 did not (Figure 6k,l). MYH6 only weakly labelled most of the intrafusal fibres.

FIGURE 6.

Reactivity of antibodies specific for MyHC‐2b and ‐α in the masseter and laryngeal cricothyreoideus muscle. The staining pattern of 10F5 and BF‐F3 (rat MyHC‐2b), BA‐G5 and MYH6 (MyHC‐α) in masseter (a–d, k, l) and cricothyreoideus muscles (e–j). The muscle sections are labelled by antibodies specific for: a. MyHC‐st, b. MyHC‐2b (10F5), c. MyHC‐2a+2x, d. MyHC‐2x, e. MyHC‐st, f. MyHC‐2b (10F5), g. MyHC‐2a+2x, h. MyHC‐2b (BF‐F3), i. MyHC‐1, j. MyHC‐α (BA‐G5), k. MyHC‐α (BA‐G5) and l. MyHC‐α (MYH6). Note first, that in the masseter (a–d) all fast fibres, labelled by antibodies specific for fast MyHC‐2a and ‐2x isoforms (SC‐71, 6H1), are reactive to antibody 10F5. Note also that in the cricothyreoideus muscle (e–g), 10F5 did not stain the fibre expressing MyHC‐st (asterisk) but labelled all fast fibres, whereas antibody BF‐F3, also specific for rat MyHC‐2b, did not react with fast fibres (h). Note that antibody BA‐G5 (j), specific for MyHC‐α, cross‐reacted with MyHC‐1 (i) in the cricothyreoideus muscle, and in the masseter did not label (k) fibres positive with MYH6 (l, arrows), also specific for MyHC‐α. Scale bar: 25 μm.

3.2. MyHC‐15, ‐2x and ‐2b isoforms

Antibody MYH15 usually stained all human intrafusal fibres but with variable intensity; generally, bag fibres were more intensely stained, particularly in the C region. The staining intensity did not depend on the secondary antibody used (horseradish peroxidase or immunofluorescence), which is evident in Figure 5. In some samples, MYH15 reactivity with intrafusal fibres was the same as that of antibody SC‐71; thus, we suspected it may cross‐react with MyHC‐2a and/or ‐2x. However, this assumption was excluded since it did not specifically label extrafusal 2a and 2x fibres; in fact, it slightly labelled all extrafusal fibres (Figures 1, 2, 3, 4, 5). Furthermore, in the extracapsular C region of the muscle spindle in BB, both bag fibres were intensively stained by MYH15, but only one was by SC‐71 (Figure 3).

Antibody 6H1, specific for MyHC‐2x, moderately labelled all intrafusal fibres in the A region of muscle spindles in BB of the young and older subject. In the B region, the same staining pattern was present only in the older subject. In the young subject, bag1 and chain fibres were moderately labelled, whereas in the middle‐aged subject, only some chain fibres were labelled. In the C region, this antibody did not label intrafusal fibres. In FDP, chain fibres were intensively to moderately labelled by 6H1. Most 6H1‐positive fibres were also intensively labelled by antibody SC‐71 (MyHC‐2a+2x); thus, they were considered to co‐express both fast MyHC isoforms. However, the fibres unstained by 6H1 were considered to express MyHC‐2a exclusively. Only a few chain fibres in BB of the older subject and in the FDP were intensively labelled by 6H1 and moderately by SC‐71; thus, they were considered to express MyHC‐2x only (Figures 4 and 5).

The antibody 10F5, specific for rat MyHC‐2b, stained human bag fibres intensively and chain fibres weakly to moderately. However, the extrafusal fibres of BB and FDP remained unlabelled. In most samples with the intracapsular part of muscle spindles, its staining pattern was the same as that of antibody specific for MyHC‐st, so it was initially assumed that 10F5 may cross‐react with MyHC‐st. However, in some spindles, the staining of the two antibodies was not the same. For example, in the extracapsular C region of BB, both bag fibres, intensively stained by an antibody specific for MyHC‐st, were unstained by 10F5 (Figure 3). This antibody was tested in the masseter and laryngeal cricothyreoideus muscle (Figure 6). In the laryngeal muscle, antibody 10F5 moderately stained all fast extrafusal fibres, whereas only a few fibres were stained by the antibody specific for MyHC‐st. In the masseter muscle, in which no fibres expressing MyHC‐st were present, 10F5 also moderately stained all fast fibres and a few slow fibres (the latter not shown). Thus, the cross‐reactivity of 10F5 with MyHC‐st can be excluded.

The reactivity of antibody BF‐F3, also specific for rat MyHC‐2b, was less specific. It either stained all intrafusal fibres moderately (bag fibres usually more intensely) and weakly cross‐reacted with extrafusal fast fibres (Figures 1 and 2), or it stained all extrafusal and intrafusal fibres uniformly (Figure 4).

4. DISCUSSION

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to demonstrate MyHC‐15 and ‐2x in human muscle spindles. The results indicate that MyHC‐15 is not abundantly expressed in the intrafusal fibres. Using an antibody exclusively specific for MyHC‐2x, it was shown that this isoform is expressed in the intracapsular regions of some intrafusal fibres, particularly in chain fibres. However, whether the labelling with the antibody specific for rat MyHC‐2b reflects the expression of this isoform in bag fibres requires further evaluation. The pattern of MyHC isoforms co‐expression in intrafusal fibres, demonstrated in this study, is partially in agreement with previous reports. It is obvious, that the estimation of MyHC expression depends on different antibodies used. Moreover, the reactivity of antibodies may differ between extrafusal and intrafusal fibres. However, it is also evident that MyHC expression in intrafusal fibres varies not only along their length but also across different muscle spindles and muscles.

MyHC‐15 was the most intensively expressed in the extracapsular region of human bag fibres in BB and FDP of the young subject, as previously found in rats (Rossi et al., 2010). Many bag fibres and some chain fibres seemed to express MyHC‐15 at low levels. In bag fibres, MyHC‐15 was mostly co‐expressed with MyHC‐st, ‐1 and ‐2a, in some spindles also with ‐2x, whereas in chain fibres, mostly with both fast and developmental MyHC isoforms. A similar pattern for bag fibres was found in FDP, in which most chain fibres did not express MyHC‐15.

MyHC‐15, one of the three ancient isoforms, with predicted slow ATPase rate, possesses the highest amino acid sequence identity with both cardiac isoforms (Desjardins et al., 2002; Lee et al., 2019). The orthologues have been demonstrated in the skeletal muscles of snakes and various mammals. In humans, MyHC‐15 has been revealed only in some extraocular muscles, pulmonary vascular endothelium and alveolar macrophages (Hansel et al., 2015; Lee et al., 2019; Mascarello et al., 2016), indicating that the MYH15 gene also plays a role in other tissues. Considered a slow MyHC isoform and expressed at low levels, the role of MyHC‐15 in muscle spindles remains obscure (Lee et al., 2019). However, the expression of slower MyHC isoforms like MyHC‐st, −1 and ‐α in intrafusal fibres correlates with their much lower contraction speed than that of the extrafusal ones (Walro & Kucera, 1999).

Using 6H1, exclusively specific for MyHC‐2x, we demonstrated that this isoform is expressed in intrafusal fibres, but most probably at low levels. Notably, evaluating MyHC‐2x expression with antibody 6H1 is remarkably difficult, given its weak reactivity. Accordingly, low dilutions and the detection system were used to improve its binding visualisation; however, both resulted in stronger background staining. Thus, to appropriately interpret the results, the staining of fibres with 6H1 should be correlated to the fibres staining in the ‘blind’ control section with primary antibody incubation omitted. Nevertheless, the intense staining of chain fibres in the B region in FDP and BB of the older subject firmly demonstrates that MyHC‐2x, suggested to be the fastest human MyHC isoform (Bloemink et al., 2013), is expressed in human intrafusal fibres (Figures 4 and 5).

The expression of MyHC‐2x in the juxta‐equatorial part of chain fibres in the BB has been previously suggested based on the staining comparison of three different antibodies specific for one or more MyHC isoforms but not exclusively for MyHC‐2x (Liu et al., 2002; Österlund et al., 2013). Moreover, the analysis of MyHC isoforms in samples of isolated muscle spindles by sodium dodecyl sulphate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS‐PAGE) revealed four MyHC bands. The slowest band, migrating just above MyHC‐2a, which is the migration position of MyHC‐2x, was declared MyHC‐emb (Liu et al., 2002; Pedrosa‐Domellöf et al., 1993). Since in the presented figure, this band seems unlabelled by BF‐35, which according to our experience, does not label human MyHC‐2x band in immunoblots (Smerdu & Soukup, 2008), it may correspond to MyHC‐2x and would match to the results of this study.

The antibody 10F5, specific for rat MyHC‐2b, stained many intrafusal fibres with variable intensity but never the extrafusal ones in the analysed limb muscles. The initial assumption that 10F5 cross‐reacted with abundantly expressed MyHC‐st in bag fibres was excluded. On the contrary to limb muscles, in the masseter muscle, 10F5 moderately stained all fast fibres and a few slow fibres (Figure 6). A similar 10F5 staining pattern of certain extrafusal fibres, co‐expressing either MyHC‐1 or MyHC‐2a and ‐2x, was observed in our prior studies of human laryngeal and extraocular muscles, in the latter MyHC‐2b transcripts were demonstrated as well (Smerdu & Cvetko, 2013; Stirn Kranjc et al., 2009), like found by another study (Horton et al., 2008). Therefore, the labelling with 10F5 suggests either the presence of another MyHC isoform or epitope in intrafusal and some extrafusal fibres in specialised muscles.

However, the expression of human MyHC‐2b isoform has not been undoubtedly proven, though the MyHC band migrating slightly above the MyHC‐1 and ‐α bands, positive with anti‐fast MyHC antibody and present in the extraocular and laryngeal muscle samples, was suggested to correspond MyHC‐2b (Mascarello et al., 2016). An extra MyHC band, migrating between MyHC‐1 and ‐2a, was also revealed in our previous study of the laryngeal muscles but was unlabelled by both antibodies specific for rat MyHC‐2b (Smerdu & Cvetko, 2013). This is not surprising since we found that 10F5 labels rat 2b fibres but not the corresponding MyHC band in immunoblots (our unpublished observations). MyHC‐2b mRNA transcripts were previously detected in the masseter muscle and in patients with Duchenne muscular dystrophy (Harrison et al., 2011; Horton et al., 2001), but not the corresponding protein, in the latter study using antibody BF‐F3. It should be noted that in our studies, BF‐F3 did not react specifically with human intrafusal and extrafusal fibres (Figures 1, 2 and 6). In contrast, in another study, neither MyHC‐2b transcripts nor the corresponding protein was detected in the masseter (Mascarello et al., 2016).

Nevertheless, the human MYH4 gene encoding MyHC‐2b is highly conserved with the corresponding mouse gene and encodes a functional motor domain as demonstrated by the recombinant protein experiments (Resnicow et al., 2010). However, its transcriptional activity is reduced due to the alteration of myocyte enhancer factor 2 and serum response factor binding sites within the proximal promoter region. The gene is thought to be transcriptionally and post‐transcriptionally regulated (Harrison et al., 2011). Though the gene possesses a very high identity to rat orthologue, encoding the fastest rat isoform, the data of kinetic measurements suggest that human MyHC‐2b is slower than MyHC‐2a and ‐2x (Bloemink et al., 2013). All these findings would imply that MyHC‐2b could be expressed in human muscle spindles and specialised cranial muscles. However, its expression and functional significance require further confirmation.

Nevertheless, the second possibility that 10F5 just unspecifically labelled the intrafusal and some extrafusal fibres due to the presence of specific epitope, should not be neglected until the expression of MyHC‐2b in human muscles is undoubtedly confirmed. Although, excluding intrafusal fibres, it is intriguing why a 10F5‐specific epitope would be present only in some extrafusal fibres in the specialised cranial muscles but not in limb muscles.

The pattern of other, previously analysed MyHC isoforms in intrafusal fibres, demonstrated in this study, only partially agrees with previous reports. As previously reported, the MyHC‐st isoform was expressed only in bag1 and bag2 fibres (Liu et al., 2002, 2005; Österlund et al., 2013). Recently, it was demonstrated that several key motor properties of MyHC‐st are slower than those of MyHC‐1 (Lee et al., 2023). In this study, MyHC‐1 was more prominently expressed in bag1 fibres, particularly in the FDP muscle, than previously reported (Liu et al., 2002).These fibres probably correspond to acid‐stable bag1 (AS‐bag1) fibres, demonstrated in the masseter and BB (Eriksson & Thornell, 1990; Österlund et al., 2013). The prominent expression of MyHC‐1 in bag2 fibres was supposed to be related to their origin from primary myotubes that express this slow isoform. On the other hand, in bag1 fibres, which develop from secondary myotubes, the initial expression of MyHC‐1 is assumed to be blocked by afferent neurons. In contrast, chain fibres were assumed not to express MyHC‐1, as they develop from secondary myotubes expressing fast isoforms (Pedrosa‐Domellof & Thornell, 1994). The results of this study indicate that bag1 fibres may switch to more abundant MyHC‐1 expression.

MyHC‐α, previously considered a slow isoform (Kwa et al., 1995), but recently demonstrated to have kinetic properties more similar to fast MyHC‐2a isoform (Deacon et al., 2012), was reported to be abundantly expressed in the A region of bag fibres in BB of children and deep neck muscles of adult subjects, whereas in the masseter, it was expressed over the entire length of bag fibres (Liu et al., 2002, 2003), but decreased in older subjects (Liu et al., 2005). Similarly, MyHC‐α is abundantly expressed in rat intrafusal fibres (Kucera et al., 1992). Despite using two antibodies, MyHC‐α expression could hardly be demonstrated in this study. Though BA‐G5 was found to cross‐react with MyHC‐1 in the extrafusal fibres in the present and another study (Luo et al., 2014), its staining of intrafusal fibres differed from that of BA‐D5. The cross‐reactivity with MyHC‐1 is not surprising since MyHC‐α and MyHC‐1 exhibit the highest degree (93%) of amino acid sequence identity (Lee et al., 2019). Despite weak labelling of intrafusal fibres, MYH6 reliably demonstrated MyHC‐α in the masseter muscle (Figure 6). However, since it did not label human bag fibres as intensively as those in the masseter, it could be assumed that MyHC‐α was not expressed in the analysed muscle spindles or was too poorly expressed to be detected. However, the possibility that the antibody MYH6 failed to reveal MyHC‐α in human intrafusal fibres should not be neglected.

MyHC‐2a was intensively expressed in bag fibres and more variably in chain fibres. This finding is consistent with theprevious study using the same antibody (Österlund et al., 2013). Interestingly, in that study, the results of SC‐71 labelling differed from those obtained by antibody A4.74, which has an identical staining pattern of extrafusal fibres as SC‐71 (Meznaric & Čarni, 2020; Meznaric et al., 2018; Smerdu & Soukup, 2008), probably indicating differently exposed epitopes in intrafusal and extrafusal fibres. The expression of MyHC‐emb was mostly absent or weaker than in the previous studies using a different antibody (Liu et al., 2003, 2005). On the contrary, the expression of MyHC‐neo was intense in chain fibres in the B region and moderate in some of them in the A region. MyHC‐neo was also expressed in bag2 fibres; this finding is both in agreement (Liu et al., 2002, 2003) and discordance (Liu et al., 2005; Österlund et al., 2013) with previous reports using the same antibody. It is noteworthy, that the experiments on the recombinant human myosin isoform motor domain showed that the predicted contractile speed of MyHC‐emb is similar to that of MyHC‐1 (Walklate et al., 2016), whereas that of MyHC‐neo is more similar to MyHC‐2a (Johnson et al., 2019).

The intrafusal fibres were initially classified according to the enzyme‐histochemical reaction for mATPase, which correlates to the contraction speed of MyHC isoforms (Guth & Samaha, 1969). Considering several MyHC isoforms co‐expression in the intrafusal fibres and recently predicted contraction properties of human MyHC isoforms, that is, st <1, 15, emb <α, 2b, 2a, neo, <2x, the histochemical profile of fibres could hardly be predicted. It would be expected to depend on the prevailing isoform. However, MyHC‐st, a slow isoform with predicted alkali‐labile and acid‐stable mATPase activity, seems to be the predominant isoform in both bag1 and bag2 fibres, but their histochemical profiles differ. Therefore, the weaker labelling of bag1 after acid preincubation could be assigned only to less abundant expression of MyHC‐1 in previous studies (Liu et al., 2002).

A very high similarity of MyHC isoforms in amino acid sequences and a potential unspecific binding of antibodies is undoubtedly a limiting factor of immunohistochemistry (Smerdu & Soukup, 2008). Though considered that the reactivity of antibodies against the extrafusal isoforms reflects their expression also in the intrafusal fibres (Kucera et al., 1992), there are apparent differences not only between intrafusal and extrafusal fibres but also between the fibres in the conventional and specialised cranial muscles.

Overall, there appears to be significant variability in the MyHC isoforms expression in the intrafusal fibres, as only about one third of bag1, bag2 and chain fibres in BB from young subjects showed the same pattern of co‐expressed isoforms (Österlund et al., 2013). In addition, there are differences across different muscles and along the intrafusal fibres' length. The latter was assumed to result from lack of motor innervation predominance in the coordinated regulation of MYH genes. The accumulation of nuclei in nuclear bags and chains in the encapsulated regions near afferent endings may facilitate the regulation of gene expression by afferents. On the contrary, in the extracapsular regions, which differ in MyHC expression from the intracapsular regions, gene expression could be regulated by external factors, including extrafusal α‐motor neurons (Kucera et al., 1991; Thornell et al., 2015). However, using different antibodies may also contribute to different interpretations of the pattern of MyHC isoforms expression across different studies.

In conclusion, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to demonstrate MyHC‐15 and ‐2x isoforms in the intrafusal fibres. Though the ‘novel’ MyHC‐15 is expressed at low levels, its expression was pronounced in the extracapsular C region of bag fibres, as previously reported in rats (Rossi et al., 2010). The expression of MyHC‐2x has also been confirmed in the intracapsular regions of some intrafusal fibres, particularly chain fibres. However, whether the labelling with the antibody specific for rat MyHC‐2b reflects the expression of this isoform in human muscle spindles and specialised skeletal muscles or it is just the result of cross‐reactivity, remains to be further evaluated.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Vika Smerdu designed and conducted the whole study and wrote the article.

FUNDING INFORMATION

The research was supported by the Slovenian Research Agency; Grant no. P3‐0043.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The author declares no conflict of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The author thanks Professor Emeritus Stefano Schiaffino for proposing the study and donating antibodies specific for MyHC‐st, ‐15 and ‐α. The author also thanks Nataša Pollak, Majda Črnak‐Maasarani, Andreja Vidmar and Marko Slak for their technical assistance and Chiedozie Kenneth Ugwoke, MD, for language proofreading.

Smerdu, V. (2023) Expression of MyHC‐15 and ‐2x in human muscle spindles: An immunohistochemical study. Journal of Anatomy, 243, 826–841. Available from: 10.1111/joa.13923

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data from this study are available from the author upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- Banks, R.W. (2006) An allometric analysis of the number of muscle spindles in mammalian skeletal muscles. Journal of Anatomy, 208(6), 753–768. Available from: 10.1111/J.1469-7580.2006.00558.X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banks, R.W. (2015) The innervation of the muscle spindle: a personal history. Journal of Anatomy, 227(2), 115–135. Available from: 10.1111/joa.12297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banks, R.W. & Barker, D. (2004) The muscle spindle. In: Engel, A. & Franzini‐Armstrong, C. (Eds.) Myology, 3rd edition. New York: McGraw‐Hill, pp. 489–509. [Google Scholar]

- Bloemink, M.J. , Deacon, J.C. , Resnicow, D.I. , Leinwand, L.A. & Geeves, M.A. (2013) The superfast human extraocular myosin is kinetically distinct from the fast skeletal IIa, IIb, and IId isoforms. The Journal of Biological Chemistry, 288(38), 27469–27479. Available from: 10.1074/jbc.M113.488130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bormioli, S.P. , Torresan, P. , Sartore, S. , Moschini, G.B. & Schiaffino, S. (1979) Immunohistochemical identification of slow‐tonic fibers in human extrinsic eye muscles. Investigative Ophthalmology and Visual Science, 18(3), 303–306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deacon, J.C. , Bloemink, M.J. , Rezavandi, H. , Geeves, M.A. & Leinwand, L.A. (2012) Identification of functional differences between recombinant human α and β cardiac myosin motors. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences: CMLS, 69(13), 2261–2277. Available from: 10.1007/s00018-012-0927-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desjardins, P.R. , Burkman, J.M. , Shrager, J.B. , Allmond, L.A. & Stedman, H.H. (2002) Evolutionary implications of three novel members of the human sarcomeric myosin heavy chain gene family. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 19(4), 375–393. Available from: 10.1093/OXFORDJOURNALS.MOLBEV.A004093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubowitz, V. (1985) Histological and histochemical stains and reactions. In: Dubowitz, V. (Ed.) Muscle biopsy. Paris: Bailliere Tindall, pp. 19–40. [Google Scholar]

- Ecob‐Prince, M. , Hill, M. & Brown, W. (1989) Immunocytochemical demonstration of myosin heavy chain expression in human muscle. Journal of the Neurological Sciences, 91(1–2), 71–78. Available from: 10.1016/0022-510X(89)90076-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ennion, S. , Sant Ana Pereira, J. , Sargeant, A.J. , Young, A. & Goldspink, G. (1995) Characterization of human skeletal muscle fibres according to the myosin heavy chains they express. Journal of Muscle Research and Cell Motility, 16(1), 35–43. Available from: 10.1007/BF00125308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson, P.‐O. & Thornell, L.‐E. (1990) Variation in histochemical enzyme profile and diameter along human masseter intrafusal muscle fibers. The Anatomical Record, 226(2), 168–176. Available from: 10.1002/ar.1092260206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorza, L. (1990) Identification of a novel type 2 fiber population in mammalian skeletal muscle by combined use of histochemical myosin ATPase and anti‐myosin monoclonal antibodies. Journal of Histochemistry and Cytochemistry, 38(2), 257–265. Available from: 10.1177/38.2.2137154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guth, L. & Samaha, F.J. (1969) Qualitative differences between actomyosin ATPase of slow and fast mammalian muscle. Experimental Neurology, 25(1), 138–152. Available from: 10.1016/0014-4886(69)90077-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansel, N.N. , Pare, P.D. , Rafaels, N. , Sin, D.D. , Sandford, A. , Daley, D. et al. (2015) Genome‐wide association study identification of novel loci associated with airway responsiveness in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. American Journal of Respiratory Cell and Molecular Biology, 53(2), 226–234. Available from: 10.1165/rcmb.2014-0198OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, B.C. , Allen, D.L. & Leinwand, L.A. (2011) IIb or not IIb? Regulation of myosin heavy chain gene expression in mice and men. Skeletal Muscle, 1(1). Available from: 10.1186/2044-5040-1-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horton, M.J. , Brandon, C.A. , Morris, T.J. , Braun, T.W. , Yaw, K.M. & Sciote, J.J. (2001) Abundant expression of myosin heavy‐chain IIB RNA in a subset of human masseter muscle fibres. Archives of Oral Biology, 46(11), 1039–1050. Available from: 10.1016/S0003-9969(01)00066-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horton, M.J. , Rosen, C. , Close, J.M. & Sciote, J.J. (2008) Quantification of myosin heavy chain RNA in human laryngeal muscles: differential expression in the vertical and horizontal posterior cricoarytenoid and thyroarytenoid. The Laryngoscope, 118(3), 472–477. Available from: 10.1097/MLG.0B013E31815C1A93 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, C.A. , Walklate, J. , Svicevic, M. , Mijailovich, S.M. , Vera, C. , Karabina, A. et al. (2019) The ATPase cycle of human muscle myosin II isoforms: adaptation of a single mechanochemical cycle for different physiological roles. The Journal of Biological Chemistry, 294(39), 14267–14278. Available from: 10.1074/jbc.RA119.009825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kucera, J. , Dorovini‐Zis, K. & Engel, W.K. (1978) Histochemistry of rat intrafusal muscle fibers and their motor innervation. Journal of Histochemistry and Cytochemistry, 26(11), 973–988. Available from: 10.1177/26.11.152786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kucera, J. , Walro, J.M. & Gorza, L. (1992) Expression of type‐specific MHC isoforms in rat intrafusal muscle fibers. Journal of Histochemistry and Cytochemistry, 40(2), 293–307. Available from: 10.1177/40.2.1552171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kucera, J. , Walro, J.M. & Reichler, J. (1991) Neural organization of spindles in three hindlimb muscles of the rat. American Journal of Anatomy, 190(1), 74–88. Available from: 10.1002/aja.1001900107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwa, S.H.S. , Weijs, W.A. & Juch, P.J.W. (1995) Contraction characteristics and myosin heavy chain composition of rabbit masseter motor units. Journal of Neurophysiology, 73(2), 538–549. Available from: 10.1152/jn.1995.73.2.538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, L.A. , Barrick, S.K. , Meller, A. , Walklate, J. , Lotthammer, J.M. , Tay, J.W. et al. (2023) Functional divergence of the sarcomeric myosin, MYH7b, supports species‐specific biological roles. The Journal of Biological Chemistry, 299(1), 102657. Available from: 10.1016/j.jbc.2022.102657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, L.A. , Karabina, A. , Broadwell, L.J. & Leinwand, L.A. (2019) The ancient sarcomeric myosins found in specialized muscles. Skeletal Muscle, 9(1), 7. Available from: 10.1186/s13395-019-0192-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.X. , Eriksson, P.O. , Thornell, L.E. & Pedrosa‐Domellöf, F. (2002) Myosin heavy chain composition of muscle spindles in human biceps brachii. Journal of Histochemistry and Cytochemistry, 50(2), 171–183. Available from: 10.1177/002215540205000205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.X. , Eriksson, P.O. , Thornell, L.E. & Pedrosa‐Domellöf, F. (2005) Fiber content and myosin heavy chain composition of muscle spindles in aged human biceps brachii. Journal of Histochemistry and Cytochemistry, 53(4), 445–454. Available from: 10.1369/jhc.4A6257.2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.X. , Thornell, L.E. & Pedrosa‐Domellöf, F. (2003) Muscle spindles in the deep muscles of the human neck: a morphological and immunocytochemical study. Journal of Histochemistry and Cytochemistry, 51(2), 175–186. Available from: 10.1177/002215540305100206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucas, C.A. , Kang, L.H.D. & Hoh, J.F.Y. (2000) Monospecific antibodies against the three mammalian fast limb myosin heavy chains. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications, 272(1), 303–308. Available from: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.2768 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo, Q. , Douglas, M. , Burkholder, T. & Sokoloff, A.J. (2014) Absence of developmental and unconventional myosin heavy chain in human suprahyoid muscles. Muscle & Nerve, 49(4), 534–544. Available from: 10.1002/MUS.23946 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mascarello, F. , Toniolo, L. , Cancellara, P. , Reggiani, C. & Maccatrozzo, L. (2016) Expression and identification of 10 sarcomeric MyHC isoforms in human skeletal muscles of different embryological origin. Diversity and similarity in mammalian species. Annals of Anatomy, 207, 9–20. Available from: 10.1016/j.aanat.2016.02.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews, P.B. (1964) Muscle spindles and their motor control. Physiological Reviews, 44, 219–288. Available from: 10.1152/physrev.1964.44.2.219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meznaric, M. & Čarni, A. (2020) Characterisation of flexor digitorum profundus, flexor digitorum superficialis and extensor digitorum communis by electrophoresis and immunohistochemical analysis of myosin heavy chain isoforms in older men. Annals of anatomy/Anatomischer Anzeiger: Official Organ of the Anatomische Gesellschaft, 227, 151412. Available from: 10.1016/j.aanat.2019.151412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meznaric, M. , Eržen, I. , Karen, P. & Cvetko, E. (2018) Effect of ageing on the myosin heavy chain composition of the human sternocleidomastoid muscle. Annals of anatomy/Anatomischer Anzeiger: Official Organ of the Anatomische Gesellschaft, 216, 95–99. Available from: 10.1016/j.aanat.2017.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Österlund, C. , Liu, J.X. , Thornell, L.E. & Eriksson, P.O. (2011) Muscle spindle composition and distribution in human young masseter and biceps brachii muscles reveal early growth and maturation. Anatomical Record, 294(4), 683–693. Available from: 10.1002/ar.21347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Österlund, C. , Liu, J.X. , Thornell, L.E. & Eriksson, P.O. (2013) Intrafusal myosin heavy chain expression of human masseter and biceps muscles at young age shows fundamental similarities but also marked differences. Histochemistry and Cell Biology, 139(6), 895–907. Available from: 10.1007/s00418-012-1072-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ovalle, W.K. & Smith, R.S. (1972) Histochemical identification of three types of intrafusal muscle fibers in the cat and monkey based on the myosin ATPase reaction. Canadian Journal of Physiology and Pharmacology, 50(3), 195–202. Available from: 10.1139/y72-030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedrosa‐Domellöf, F. , Gohlsch, B. , Thornell, L.E. & Pette, D. (1993) Electrophoretically defined myosin heavy chain patterns of single human muscle spindles. FEBS Letters, 335(2), 239–242. Available from: 10.1016/0014-5793(93)80737-F [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedrosa‐Domellof, F. & Thornell, L.E. (1994) Expression of myosin heavy chain isoforms in developing human muscle spindles. Journal of Histochemistry and Cytochemistry, 42(1), 77–88. Available from: 10.1177/42.1.8263326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierobon Bormioli, S. , Sartore, S. , Vitadello, M. & Schiaffino, S. (1980) “Slow” myosins in vertebrate skeletal muscle: an immunofluorescence study. Journal of Cell Biology, 85(3), 672–681. Available from: 10.1083/jcb.85.3.672 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnicow, D.I. , Deacon, J.C. , Warrick, H.M. , Spudich, J.A. & Leinwand, L.A. (2010) Functional diversity among a family of human skeletal muscle myosin motors. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 107(3), 1053–1058. Available from: 10.1073/pnas.0913527107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi, A.C. , Mammucari, C. , Argentini, C. , Reggiani, C. & Schiaffino, S. (2010) Two novel/ancient myosins in mammalian skeletal muscles: MYH14/7b and MYH15 are expressed in extraocular muscles and muscle spindles. Journal of Physiology, 588(2), 353–364. Available from: 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.181008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudnicki, M.A. , Jackowski, G. , Saggin, L. & McBurney, M.W. (1990) Actin and myosin expression during development of cardiac muscle from cultured embryonal carcinoma cells. Developmental Biology, 138(2), 348–358. Available from: 10.1016/0012-1606(90)90202-T [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saez, L.J. , Gianola, K.M. , McNally, E.M. , Feghali, R. , Eddy, R. , Shows, T.B. et al. (1987) Human cardiac myosin heavy chain genes and their linkage in the genome. Nucleic Acids Research, 15(13), 5443–5459. Available from: 10.1093/NAR/15.13.5443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiaffino, S. , Saggin, L. , Ausoni, S. , Sartore, S. & Gorza, L. (1986) Muscle fiber types identified by monoclonal antibodies to myosin heavy chains. In: Benzi, G. , Packer, L. & Siliprandi, N. (Eds.) Biochemical aspects of physical exercise. Amsterdam: Elsevier, pp. 27–34. [Google Scholar]

- Schiaffino, S. , Rossi, A.C. , Smerdu, V. , Leinwand, L.A. & Reggiani, C. (2015) Developmental myosins: expression patterns and functional significance. Skeletal Muscle, 5(1), 22. Available from: 10.1186/s13395-015-0046-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smerdu, V. & Cvetko, E. (2013) Myosin heavy chain‐2b transcripts and isoform are expressed in human laryngeal muscles. Cells, Tissues, Organs, 198(1), 75–86. Available from: 10.1159/000351293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smerdu, V. & Eržen, I. (2001) Dynamic nature of fibre‐type specific expression of myosin heavy chain transcripts in 14 different human skeletal muscles. Journal of Muscle Research and Cell Motility, 22(8), 647–655. Available from: 10.1023/A:1016337806308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smerdu, V. , Karsch‐Mizrachi, I. , Campione, M. , Leinwand, L. & Schiaffino, S. (1994) Type IIx myosin heavy chain transcripts are expressed in type IIb fibers of human skeletal muscle. The American Journal of Physiology, 267(6), C1723–C1728. Available from: 10.1152/ajpcell.1994.267.6.c1723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smerdu, V. & Soukup, T. (2008) Demonstration of myosin heavy chain isoforms in rat and humans: the specificity of seven available monoclonal antibodies used in immunohistochemical and immunoblotting methods. European Journal of Histochemistry, 52(3), 179–189. Available from: 10.4081/1210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sokoloff, A.J. , Li, H. & Burkholder, T.J. (2007) Limited expression of slow tonic myosin heavy chain in human cranial muscles. Muscle and Nerve, 36(2), 183–189. Available from: 10.1002/mus.20797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stedman, H.H. , Kozyak, B.W. , Nelson, A. , Thesier, D.M. , Su, L.T. , Low, D.W. et al. (2004) Myosin gene mutation correlates with anatomical changes in the human lineage. Nature, 428(6981), 415–418. Available from: 10.1038/nature02358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stirn Kranjc, B. , Smerdu, V. & Eržen, I. (2009) Histochemical and immunohistochemical profile of human and rat ocular medial rectus muscles. Graefe's Archive for Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology/Albrecht von Graefes Archiv Fur Klinische Und Experimentelle Ophthalmologie, 247(11), 1505–1515. Available from: 10.1007/s00417-009-1128-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornell, L.E. , Carlsson, L. , Eriksson, P.O. , Liu, J.X. , Österlund, C. , Stål, P. et al. (2015) Fibre typing of intrafusal fibres. Journal of Anatomy, 227(2), 136–156. Available from: 10.1111/JOA.12338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toniolo, L. , Cancellara, P. , Maccatrozzo, L. , Patruno, M. , Mascarello, F. & Reggiani, C. (2008) Masticatory myosin unveiled: first determination of contractile parameters of muscle fibers from carnivore jaw muscles. American Journal of Physiology—Cell Physiology, 295(6), C1535–C1542. Available from: 10.1152/ajpcell.00093.2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walklate, J. , Vera, C. , Bloemink, M.J. , Geeves, M.A. & Leinwand, L. (2016) The most prevalent Freeman‐Sheldon syndrome mutations in the embryonic myosin motor share functional defects. The Journal of Biological Chemistry, 291(19), 10318–10331. Available from: 10.1074/jbc.M115.707489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walro, J.M. & Kucera, J. (1999) Why adult mammalian intrafusal and extrafusal fibers contain different myosin heavy‐chain isoforms. Trends in Neurosciences, 22(4), 180–184. Available from: 10.1016/S0166-2236(98)01339-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss, A. , McDonough, D. , Wertman, B. , Acakpo‐Satchivi, L. , Montgomery, K. , Kucherlapati, R. et al. (1999) Organization of human and mouse skeletal myosin heavy chain gene clusters is highly conserved. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 96(6), 2958–2963. Available from: 10.1073/PNAS.96.6.2958 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss, A. , Schiaffino, S. & Leinwand, L.A. (1999) Comparative sequence analysis of the complete human sarcomeric myosin heavy chain family: implications for functional diversity. Journal of Molecular Biology, 290(1), 61–75. Available from: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wieczorek, D.F. , Periasamy, M. , Butler‐Browne, G.S. , Whalen, R.G. & Nadal‐Ginard, B. (1985) Co‐expression of multiple myosin heavy chain genes, in addition to a tissue‐specific one, in extraocular musculature. The Journal of Cell Biology, 101(2), 618–629. Available from: 10.1083/JCB.101.2.618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data from this study are available from the author upon reasonable request.