Abstract

Hibiscus trionum, commonly known as the ‘Flower of an Hour’, is an easily cultivated plant in the Malvaceae family that is widespread in tropical and temperate regions, including drylands. The purple base part of its petal exhibits structural colour due to the fine ridges on the epidermal cell surface, and the molecular mechanism of ridge formation has been actively investigated. We performed genome sequencing of H. trionum using a long-read sequencing technology with transcriptome and pathway analyses to identify candidate genes for fine structure formation. The ortholog of AtSHINE1, which is involved in the biosynthesis of cuticular wax in Arabidopsis thaliana, was significantly overexpressed in the iridescent tissue. In addition, orthologs of AtCUS2 and AtCYP77A, which contribute to cutin synthesis, were also overexpressed. Our results provide important insights into the formation of fine ridges on epidermal cells in plants using H. trionum as a model.

Keywords: Hibiscus trionum, genome, transcriptome, ridge structure, flower iridescence

1. Introduction

The genus Hibiscus belongs to the Malvaceae family and is widely distributed in both temperate and tropical regions of the world. There are over 200 species in the genus, ranging from annual and perennial flowers to woody shrubs and small trees. Hibiscus syriacus (known as the Rose of Sharon) and Hibiscus rosa-sinensis (China rose) are two common ornamental plants with attractive flowers. As reviewed in Da-Costa-Rocha et al. (2014),1Hibiscus sabdariffa (Roselle) is native to Africa and is used worldwide for its fibres, food, and medicinal properties. Another African species, Hibiscus cannabinus (kenaf), is also known for its fibre production.

Hibiscus trionum is an annual to short-lived perennial plant that is widespread in tropical and temperate regions of Europe, Asia, and Africa, including drylands. Commonly known as the ‘Flower of an Hour’, its flowers are only open for a few hours in the morning. The centre of the flower is deep purple with anthocyanin pigments (Fig. 1A and B), and the pistil is fused with many stamens (Fig. 1A). The adaxial surface of the purple region (Fig. 1B-a) is striated with fine structures like ridges that show iridescence2,3 (Fig. 1C-a, and D-a1 and a2). As the flower opens, the epidermal cells in the purple region elongate to form the fine structure through a combination of mechanical stress and chemical changes to the cuticle.4,5 On the other hand, the outside of the petal is light yellow with flavonols (Fig. 1B-c–e). The adaxial epidermal cells in the light-yellow region are conically shaped (Fig. 1C-c and d), and the cells at the most distal tip are almost pointed (Fig. 1C-e). In contrast to the purple region, no ridges were observed in the light yellow region2,4,5 (Fig. 1C-d, and D-d1 and d2).

Figure 1.

Flowers of H. trionum and their electron microscopy images. (A) A flower image of H. trionum. (B) A petal image of H. trionum. The right image shows the observation positions in C and D. (C) Scanning electron microscopy images at each position indicated in B. The broken lines indicate the sectioning axis in D. (D) Transmission electron microscopy images obtained for positions a and d indicated in B, along the sectioning axis shown in C. a1 and a2, and d1 and d2 are magnified views of the positions indicated by the rectangles in a and d, respectively. Arrows in a1, a2, d1, and d2 indicate extracellular matrix including cell wall and cuticle layers. an, anthocyanin. Scale bars, 1 cm in A and B; 30 μm in C; 5 μm in D.

The H. trionum genome provides a valuable resource for investigating the molecular mechanism of the formation of fine structures with iridescence, supporting omics analyses (i.e. transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics), and genome editing. In our incubator, H. trionum flowers when it reaches a plant length of about 15 cm, without the need for long or short-day photoperiods. Furthermore, self-fertilization is possible with a lifecycle of about 2 months. Therefore, H. trionum has the potential to be a model plant for the study of floral iridescence.

In this study, we sequenced the genome of H. trionum using PacBio Sequel II systems powered with HiFi sequencing technology, which can produce highly accurate long reads. We also compared its transcriptomes between petal regions with and without the fine ridges to identify candidate genes. Our results provide important insights into the formation of fine structures on epidermal cells with iridescence.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Plant materials and culture conditions

The seeds of H. trionum L. were obtained from the botanical gardens of Osaka Metropolitan University (Osaka, Japan), Tokyo Metropolitan Medicinal Plants Garden (Tokyo, Japan), Tokyo Metropolitan Kiba Park (Tokyo, Japan), Shigei Medicinal Plants Garden (Kurashiki, Japan), and a flower shop in Hamamatsu (Hamamatsu, Japan). Self-reproduction was performed repeatedly using the H. trionum from the Hamamatsu flower shop and the strain name was Htri001sk. This line was used for the sequencing. Plants were cultivated at 22–25°C under long-day conditions (16 h light and 8 h dark) in soil.

2.2. Preparation of chromosomes

Root tips were pretreated with 2 mM 8-hydroxyquinoline for 4 h at room temperature in dark conditions. The pretreated root tips were fixed with 3:1 (v/v) ethanol/glacial acetic acid for 3 days at room temperature and stored at 4°C until use. The fixed root tips (two to three) were then soaked in distilled water for 10 min and the water was removed with a Kimwipe on the glass slide. The root tips were stained with 2% (w/v) carmine (Merck, NJ, USA) in 45% acetic acid for 1 h at room temperature and washed with distilled water for 2 min to remove the acetic acid. Two to three root tips were put on the glass slides and the water was removed with a Kimwipe. Then, treated with enzymatic solutions consisting of 2% (w/v) of pectolyase Y23 (Kyowa Kasei, Osaka, Japan), 2% (w/v) of cytohelicase (Sigma–Aldrich, MO, USA), and 2% (w/v) of cellulase ‘ONOZUKA’ R-10 (Yakult, Tokyo, Japan) dissolved in 1× citrate buffer (0.01 M of Na-critic and citric acid diluted with distilled water and adjusted to pH 4.5–4.8) at 37°C for 30 min to 1 h depending on the root size. Ten microliters of 45% acetic acid were added to the root tips and the acetic acid squash method was used with a 22 × 22-mm coverslip. Images were captured with a DP21 camera (Olympus/Evident, Tokyo, Japan) using a BX40 microscope (Olympus/Evident, Tokyo, Japan), and the number of chromosomes was counted manually.

2.3. Flow cytometric analysis

For ploidy analysis, leaves cut into 5 mm squares were sectioned with a blade in 200 μl nuclear extraction buffer of the Quantum Stain NA UV2 kit (Quantum Analysis, Münster, Germany) containing 2 μl/ml 2-mercaptoethanol and 2% PVP K30, and incubated for 1 min at room temperature. One milliliter of DAPI staining solution from the same kit was added and filtered through a 30 μl nylon mesh. After incubation for 1 min at room temperature, the fluorescence intensity of DAPI was measured using a flow cytometer, Quantum P (Quantum Analysis, Münster, Germany).

For genome size estimation, leaves were subjected to the same treatment as for the ploidy analysis using the Quantum Stain PI kit (Quantum Analysis, Münster, Germany). One milliliter of PI staining solution from the same kit was added and filtered through a 30 μl nylon mesh. After incubation for 1 h in the dark conditions, the fluorescence intensity of PI was measured using a flow cytometer, CyFlow SL (Partec, Münster, Germany).

2.4. Electron microscopy

For scanning electron microscopy, the raw petal samples were observed using HITACHI Miniscope TM4000Plus (Hitachi High-Tech, Tokyo, Japan) with a cooling stage at –30°C and an acceleration voltage of 5 kV.

For transmission electron microscopy, petals were fixed with 2% glutaraldehyde in 50 mM cacodylate buffer (pH 7.4) at 4°C overnight. The fixed samples were washed 3× in 50 mM cacodylate buffer and then post-fixed with 2% osmium tetroxide in the same buffer for 3 h at 4°C. After dehydration in a graded ethanol series (50, 70, 90, and 3× with 100%), the samples were infiltrated with propylene oxide (PO) for 1.5 h, a 50:50 mixture of PO and Epon812 resin (TAAB, Berks, England) for 3 h, and 100% Epon812 resin overnight, and polymerized at 60°C for 1 day. Ultrathin sections (70 nm thickness) were cut with a diamond knife (Diatome, Nidau, Switzerland) on a Leica EM UC6 + FC6 ultramicrotome (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany) and mounted on copper grids. The sections were stained with 2% uranyl acetate for 10 min followed by lead staining solution (Sigma–Aldrich, MA, USA) for 3 min. The grids were observed under a transmission electron microscope JEM-1010 (JEOL, Tokyo, Japan) with a CCD camera at an acceleration voltage of 80 kV.

2.5. Isolation of high-molecular-weight genomic DNA

Young fresh leaf tissues were frozen in liquid nitrogen and homogenized into powders. The 0.7 g tissue powders were washed twice using a 45 ml sorbitol wash buffer [100 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.0, 0.35 M sorbitol, 5 mM EDTA pH 8.0, 1% (w/v) polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP-40), and 1% (v/v) β-mercaptoethanol] to remove polysaccharides as described previously.6 The IBTB buffer was prepared by mixing the isolation buffer [IB; 15 mM Tris, 10 mM EDTA, 130 mM KCI, 20 mM NaCl, and 8% (w/v) PVP-10, pH9.4], 0.1% Triton X-100, and 7.5% (v/v) β-mercaptoethanol. The obtained pellet of 1.4 g tissue was mixed vigorously with 14 ml of ice-cold IBTB buffer in a 50 ml conical tube. The mixture was filtered through a 100 μm nylon filter, followed by a 40 μm filter to remove tissue fragments. The filtrate was gently mixed with 140 μl of Triton X-100, and centrifuged at 4°C for 10 min at 2,000 × g to pellet the nuclei. The nuclear pellet from 2.8 g of tissue was vortexed with 10 ml of 2× CTAB buffer [2% (w/v) hexadecyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB), 1.4 M NaCl, 20 mM EDTA, 100 mM Tris–HCl (pH 8.0)] and 1 mg/ml Proteinase K, and incubated at 50°C for 30 min with gentle agitation. RNase A was added to the mixture to achieve a final concentration of 0.1 mg/ml, and incubated at 37°C for 30 min. After the addition of 10 ml of chloroform, the mixture was rotated for 30 min and centrifuged at 7,500 × g for 15 min. The upper aqueous phase was transferred to a new tube, and the same procedure was repeated. The aqueous phase was combined with an equal volume of 2-propanol and centrifuged at 4,500 × g for 20 min. The precipitate was rinsed twice with 3 ml of 70% ethanol, air-dried for 10 min and then resuspended in 50 µl of TE [10 mM Tris–HCl (pH 8.0), 1 mM EDTA].

2.6. Library preparation and sequencing

The genomic DNA library was constructed using the SMRTbell Express Template Prep Kit v2.0 (PacBio, CA, USA) with a size range of 10–50 kbp using the BluePippin size selection system (Sage Science, MA, USA). The libraries were sequenced on two cells of the PacBio Sequel II platform using the Sequel II Binding Kit v2.2 (PacBio, CA, USA). The statistics of the obtained reads are shown in Supplementary Table S1.

2.7. Genome assembly and gene prediction

HiFi reads were assembled using Hifiasm7 (v0.16.1) with the ‘-N 1000’ option. The assembled contigs were aligned to the chloroplast (NC_026909.1) and mitochondrial (NC_035549.1) genomes of the related species, searching for contigs with high identity (>90%) and coverage (>90%). A contig aligned to the chloroplast genome was removed but there was no contig aligned to the mitochondrial genome. The assembled genome was evaluated using BUSCO8 (v5.4.4) with the eudicots_odb10 and embryophyta_odb10 datasets. Gene prediction was performed by BRAKER29,10 using H. trionum RNA-seq data (the same datasets as in the transcriptome analysis section) and plant protein datasets obtained from OrthoDB11 (v11). The predicted genes obtained from each dataset were merged using TSEBRA12 (v1.0.3), and genes with at least partial support from known sequences were selected using a script from BRAKER2, selectSupportedSubsets.py, with the ‘--anySupport’ option. The final version of the predicted genes was evaluated by BUSCO using the eudicots_odb10 and embryophyta_odb10 datasets.

2.8. Gene annotation

The predicted gene sequences were translated into protein sequences using GffRead13 (v0.12.7). The protein sequences were BLASTP searched14,15 (v2.13.0+) against Arabidopsis thaliana protein sequences. The results were filtered with the threshold (query coverage ≥ 80 and e-value ≤ 1e – 5) and the descriptions of the best-hit proteins in A. thaliana were mapped to H. trionum sequences. Ortholog groups were predicted using OrthoFinder16 (v2.5.4) with the protein sequences of nine plant species (H. trionum, Hibiscus syriacus, A. thaliana, Solanum lycopersicum, Ipomoea nil, Lotus japonicus, Antirrhinum majus, Populus trichocarpa, and Oryza sativa (the references are listed in Supplementary Table S2)). The results are presented in Supplementary Table S3. Domains and important sites on the proteins were predicted using InterProScan.17 Transcription factors (TFs) were predicted by the Transcription Factor Prediction tool on the PlantTFDB website.18

2.9. Transcriptome analysis

Petals of 5–6 mm in size were collected and dissected into the purple and light yellow regions. RNA was extracted using an ISOSPIN Plant RNA Kit (Nippon Gene, Tokyo, Japan). The RNA integrity was checked using the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer System (Agilent Technologies, CA, USA) with an RNA Integrity Number (RIN) value greater than or equal to seven. Sequencing libraries were constructed using the TruSeq stranded mRNA library kit (Illumina, CA, USA) after random fragmentation of the reverse-transcribed cDNA. The libraries were sequenced on a NovaSeq 6000 system (Illumina, CA, USA). The statistics of the reads are shown in Supplementary Table S1. The obtained reads were evaluated using FastQC19 (v0.11.5), and adapter, poly-A, and low quality sequences were removed using Cutadapt20 (v2.5). The remaining reads were mapped to the H. trionum genome with the gene structure annotations, and transcript per million (TPM) was calculated using RSEM21 (v1.3.1) with a mapping tool STAR22 (v2.7.10b). The differential expression genes (DEGs) between the purple and light yellow regions of the petals were identified using TCC23 of the R software. DEGs were further annotated by BLAST search against NCBI nr datasets (e-value ≤ 1e – 5).

2.10. Pathway analysis

Pathways related to cuticle and anthocyanin in A. thaliana were searched using the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) database,24 and the lists of genes involved in these pathways were obtained. The A. thaliana gene lists were then linked to the H. trionum genes using the information from the predicted ortholog groups.

2.11. Phylogenetic analysis

BLASTP searches were performed against the protein sequences of the species listed in Supplementary Table S2 using AtSHINE1–3 as query sequences. The results were filtered with a threshold, e-value < 1e – 50. Multiple sequence alignment was performed using MAFFT25 with the accurate option L-INS-i. A phylogenetic tree was constructed based on the multiple sequence alignment with the setting of complete deletion of gap sites using the maximum-likelihood method of the MEGA 11 software,26 with 1,000 bootstrap replicates. Jones–Taylor–Thornton (JTT) matrix-based models27 with gamma-distribution among sites and subtree-pruning–regrafting—extensive (SPR level 5) were used for amino acid substitution modelling and heuristic methods. The alignment sequences and sequence regions used for the phylogenetic tree in FASTA format are provided as Supplementary Datasets S1 and S2.

3. Results

3.1. Selection of a diploid Hibiscus trionum line and its genome size

In Hibiscus trionum, both diploid (2n = 2x = 28) and tetraploid (2n = 4x = 56) lines have been reported.28–31 For efficient genetic analyses, we focused on the diploid line. Five H. trionum lines were collected from the following locations in Japan: The botanical garden of Osaka Metropolitan University (Osaka line), Tokyo Metropolitan Medicinal Plants Garden (Tokyo-Medicinal line), Tokyo Metropolitan Kiba Park (Tokyo-Kiba line), Shigei Medicinal Plants Garden (Kurashiki line), and a flower shop in Hamamatsu (Hamamatsu hibiscus). In Osaka line, the tetraploid number (2n = 2x = 56) of the chromosome was comfirmed by chromosome counting (Supplementary Fig. S1A). We compared DAPI fluorescence intensities by flow cytometry with other lines to the tetraploid Osaka line to confirm the ploidy. The fluorescence intensity peaks of the Tokyo-Medicinal, Tokyo-Kiba, and Kurashiki lines were detected at the same position as the Osaka line, whereas the peak of the Hamamatsu hibiscus was at half the position (Supplementary Fig. S1B). Based on these results, the Hamamatsu hibiscus was considered to be diploid.

We estimated the genome size of the diploid H. trionum (Hamamatsu hibiscus) by comparing the peaks of PI fluorescence intensity with those of A. thaliana (135 Mb) and Nicotiana benthamiana (about 3 Gb) using flow cytometry. The relative peak positions were 67.33 and 209.13 between the H. hibiscus and the A. thaliana (Supplementary Fig. S1C), and 210.43 and 344.94 between the H. hibiscus and the N. benthamiana, respectively (Supplementary Fig. S1D). Based on these ratios, the genome size of the diploid H. trionum was estimated to be 1.6–1.8 Gb. Self-reproduction was performed repeatedly using the diploid H. trionum and the strain name was Htri001sk. This strain was used for the sequencing.

3.2. Genome assembly and the gene annotation

Extracted high-molecular-weight genomic DNA from the diploid line was sequenced using the Sequel II system (PacBio, CA, USA). The obtained HiFi reads were assembled using the Hifiasm assembler as shown in Table 1. The total length of the contigs was about 1.67 Gb, which was consistent with the estimated size. The N50 length and the number of contigs were about 41 Mb and 276, respectively. The BUSCO evaluation showed 99.4% and 99.6% coverage of the core genes of eudicots and embryophyta, respectively.

Table 1.

Statistics and BUSCO value of the assembled genome

| Statistics of the assembled genome | ||

|---|---|---|

| Total length of contigs | 1,671,232,404 bp | |

| Number of contigs | 276 | |

| Number of contigs (>10 Mb) | 45 | |

| N50 length | 41,362,954 bp | |

| Predicted gene loci | 51,828 | |

| Predicted genes | 53,010 | |

| BUSCO value of genome | eudicots_odb10 | embryophyta_odb10 |

| Complete | 99.4% | 99.6% |

| Single-copy | 63.1% | 65.7% |

| Duplicated | 36.3% | 33.9% |

| Fragmented | 0.1% | 0.2% |

| Missing | 0.5% | 0.2% |

| BUSCO value of all predicted genes | eudicots_odb10 | embryophyta_odb10 |

| Complete | 98.3% | 98.7% |

| Single-copy | 56.4% | 60.3% |

| Duplicated | 41.9% | 38.4% |

| Fragmented | 0.6% | 0.7% |

| Missing | 1.1% | 0.6% |

Gene prediction was performed by BRAKER2 using our RNA-seq data (the same data as in the next subsection) and the protein datasets from OrthoDB. In total, 51,828 loci and 53,010 genes including splicing variants were predicted with support from known sequences, and these genes included 98.3% and 98.7% of the BUSCO core genes of eudicots and embryophyta, respectively (Table 1). The predicted genes were further annotated with BLASTP searches between the translated protein sequences and A. thaliana protein sequences. Next, we examined the presence of seven TF families using the Transcription Factor Prediction tool on the PlantTFDB website. The resulting number of seven TF families in A. thaliana, H. trionum, and H. syriacus is shown in Table 2. The details of all TF members can be found in Supplementary Table S4.

Table 2.

The number of TFs in each species

| TF family | A. thaliana | H. trionum | H. syriacus |

|---|---|---|---|

| MADS | 109 | 125 | 263 |

| MYB | 144 | 329 | 609 |

| NAC | 114 | 219 | 441 |

| WRKY | 72 | 186 | 390 |

| bHLH | 153 | 359 | 692 |

| bZIP | 73 | 172 | 374 |

| ARF | 22 | 56 | 106 |

3.3. Comparison of gene expression between parts of petals with/without fine structures

To investigate the gene expressions in the purple region with the fine structures and the light yellow region without the fine structures, we performed RNA-seq analysis on these samples. Since the ridge structures are formed during flower development,4 we collected petals before the completion of the fine structure (5–6 mm in size) and attempted to identify the responsible genes. The obtained illumina short reads were mapped to the H. trionum genome sequence and differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were selected using the following threshold: q-value (false discovery rate [FDR]) < 0.001 and expression level ratio >= 2-fold. The highly expressed genes in the purple and light yellow regions were 260 and 221, respectively (Supplementary Tables S5 and S6).

We characterize DEGs using three lists of genes: TF genes (blue flags), genes with almost no expression in the other region (average of transcript per million [TPM] < 0.15; yellow flags), and genes with extreme expression difference (>100-fold; orange flags) (K–M columns in Supplementary Tables S5 and S6). Among the DEGs that were highly expressed in the purple region, the TF list included 20 genes, such as those encoding MYB family genes, bZIP family genes, ARF family proteins, regulatory factors of flower development including MADS domain proteins, and ERF/AP2 protein similar to AtSHINE1 for wax biosynthesis. The number of non-expressed genes in the light yellow region was 14. They partially overlapped with the TF genes similar to AtAPETALA1, AtTGS7, and AtSHINE1. The others were genes similar to AtXTH30 (xyloglucan endotransglucosylase/hydrolase 30), AtGA20ox (involved in gibberellin biosynthesis), and genes involved in osmotic pressure. The high-difference list contained 17 genes, nine of which overlapped with the no-expression genes. Remarkably, five genes showed expression ratios greater than 1,000-fold: two were Arabidopsis CUTIN SYNTHASE2 (AtCUS2; involved in cutin synthesis) like genes and another two were Arabidopsis dihydroflavonol 4-reductase (AtDFR; involved in leucoanthocyanidin synthesis) like genes.

The DEGs that were highly expressed in the light yellow region were as follows. The TF list contained 46 genes, including MYB domain proteins, bHLH family proteins, C2H2 family proteins, HD-ZIP proteins, and a YABBY family protein involved in the polarity specification of the adaxial/abaxial axis. Notably, an AtMYB16-like gene was detected that regulates the epidermal conical cells in petals.32 The list of no-expression in the purple region included 10 genes such as Arabidopsis ASYMMETRIC LEAVES 2-LIKE 1 (AtASL1; involved in proximal–distal patterning). The high expression list contained nine genes including the AtYABBY5- and AtASL1-like genes listed above.

3.4. Pathway analyses of cuticle and flavonoid

We examined genes in the cuticle and flavonoid pathways that were differentially expressed between the purple and light yellow regions of H. trionum petals. We first extracted genes involved in the cuticle and flavonoid pathways in A. thaliana, and then located H. trionum genes based on the putative ortholog groups. A. thaliana genes orthologous to DEGs were highlighted in purple and yellow, respectively, based on their highly expressed region, respectively (Supplementary Tables S7 and S8).

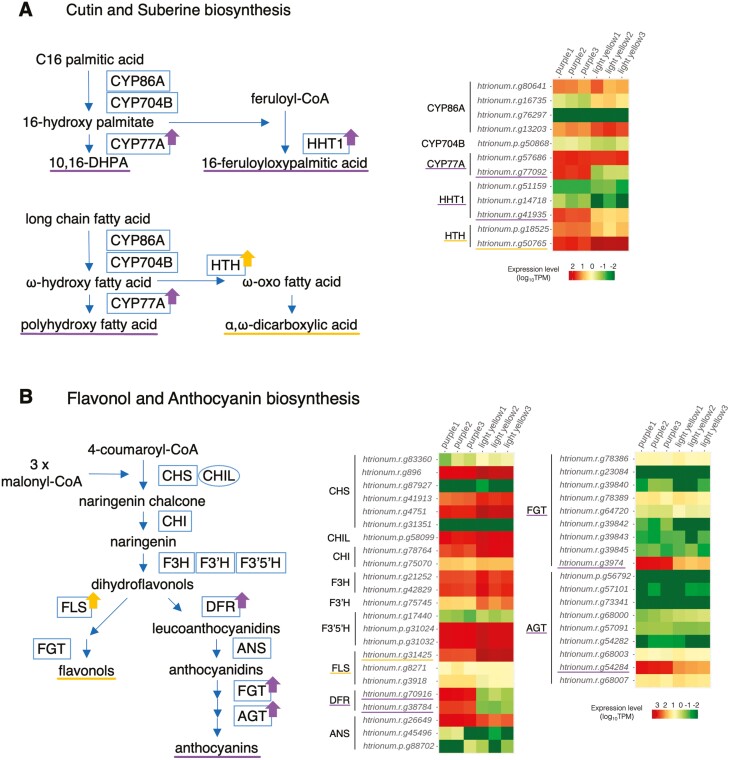

In the cuticle pathway, we detected one A. thaliana gene orthologous to highly expressed genes in the light yellow region each in the fatty acid biosynthesis (KEGG PATHWAY: ath00061) and in the fatty acid elongation (KEGG PATHWAY: ath00062), and a few A. thaliana genes orthologous to highly expressed genes in both the purple and light yellow regions in fatty acid degradation (KEGG PATHWAY: ath00071). We also found several A. thaliana genes orthologous to the highly expressed genes in the purple and light yellow regions in cutin, suberin, and wax biosynthesis (KEGG PATHWAY: ath00073) but they were involved in the synthesis of the different metabolites. The genes highly expressed in the purple were putative orthologs of Arabidopsis cytochrome P450, family 77, subfamily A (CYP77A member) and HXXXD-type acyl-transferase family genes (AtRWP1), which are involved in the metabolism of cutin monomer, 10,16-dihydroxyhexadecanoic acid (10,16-DHPA) or polyhydroxy-fatty acid, and suberin monomer, 16-feruloyloxypalmitic acid, respectively (Fig. 2A). On the other hand, the gene highly expressed in the light yellow was a putative ortholog of Arabidopsis glucose–methanol–choline (GMC) oxidoreductase family gene (AtHTH), which is involved in the metabolism of suberin monomer α,ω-dicarboxylic acids (Fig. 2A).

Figure 2.

Biosynthetic pathways and expression profiles of enzyme genes. (A) Schematic diagram representation of the cutin and sberine biosynthesis (left) and the expression profiles of the enzyme genes of three replicates in the purple and light yellow regions (right). Enzymes are represented by rectangles. CYP86A, cytochrome P450 family 86 subfamily A; CYP704B, cytochrome P450 family 704 subfamily B; CYP77A, cytochrome P450 family 77 subfamily A; HHT1, omega-hydroxypalmitate O-feruloyl transferase; HTH, fatty acid omega-hydroxy dehydrogenase. (B) Schematic representation of flavonol and anthocyanidin biosynthesis (left), and the expression profiles of the enzyme genes of three replicates in the purple and light yellow regions (right). Enzymes and an enhancer are indicated by rectangles and a circle, respectively. CHS, chalcone synthase; CHI, chalcone isomerase; CHIL, chalcone isomerase-like protein, which is an enhancer of CHS33,34; F3H, flavanone 3-hydroxylase; F3ʹH, flavonoid 3ʹ-hydoroxylase; F3ʹ5ʹH, flavonoid 3ʹ,5ʹ-hydoroxylase; FLS, flavonol synthase; DFR, dihydroflavonol 4-reductase; ANS, anthocyanidin synthase; FGT, flavonoid glucosyl transferase; AGT, anthocyanin glucosyl transferase. The purple and yellow arrows in A and B indicate up-regulated enzymes in the purple and light yellow regions, respectively. For colour figure refer to online version.

In the flavonoid pathway, we found one A. thaliana gene orthologous to highly expressed genes in the purple region each in the anthocyanin biosynthesis (KEGG PATHWAY: ath00942) and in the flavone and flavonol biosynthesis (KEGG PATHWAY: ath00944). In addition, one A. thaliana gene orthologous to the highly expressed genes in the purple and light yellow regions was found each in the flavonoid biosynthesis (KEGG PATHWAY: ath00941). Genes highly expressed in the purple region were a putative ortholog of AtUGT78D member, AtUF3GT, and AtDFR encoding flavonoid glucosyltransferase (FGT), anthocyanin glucosyltransferase (AGT), and dihydroflavonol 4-reductase, respectively. A gene highly expressed in the light yellow region was a putative ortholog of Arabidopsis flavonol synthase 1 (AtFLS1) (Fig. 2B).

4. Discussion

In this study, we sequenced the diploid H. trionum genome (2n = 28), whose genome size was consistent with the size estimated by flow cytometric analysis, and predicted a total of 53,010 genes on 51,828 loci in the genome. The genome and the predicted genes covered 99.6% and 98.7% of the core genes of embryophyta, respectively (Table 1), indicating the validity of our approach including the assembly and annotation. By BUSCO, the completeness of single-copy orthologs in the genome and genes was 65.7% and 60.3%, and that of duplicated single-copy orthologs was 33.9% and 38.4%, respectively, suggesting a high level of heterozygosity in the assembled genome. In the k-mer frequency plot obtained from Hifiasm (Supplementary Fig. S2), a prominent peak (Peak 1) was recognized as a homo-peak by Purge_Dups35 (run internally in Hifiasm). However, a very small additional peak (Peak 2) was also observed, and haplotigs may not have been effectively purged, which could explain the detection of many duplicate single-copy orthologs by BUSCO. Even if this is the case, retaining the haplotigs is useful for future genome editing of candidate genes. We mapped the HiFi reads to the assembled genome and examined the loci of the candidate genes described below using IGV but no extreme variations in read coverage were observed around the loci (Supplementary Fig. S3).

It has been suggested that Hibiscus species have independently undergone whole genome duplication (WGD),36 as evidenced by their high and diverse numbers of chromosomes and genes (Table 3). H. trionum is unique from others in its lower number of chromosomes and genes, and the accuracy of gene prediction results. With its short life cycle and small size, H. trionum is a good target for molecular analysis (e.g. genome editing). Comparing the number of major TFs with A. thaliana, we found that MYB domain proteins, WRKY family proteins, bHLH family proteins, bZIP family proteins, and ARF family proteins were detected more than 2-fold in both H. trionum and H. syriacus (Table 2).

Table 3.

Genome size and chromosome number in Hibiscus species

| Species | Chromosome number | Genome size (Gb) | Nnumber of genes | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H. trionum (diploid) | 2n = 28 | 1.6 | 53,009 | This study |

| H. syriacus | 2n = 80 | 1.75 | 87,603 | Kim et al., 201737 |

| H. mutabilis | 2n = 92 | 2.68 | 118,222 | Yang et al., 202238 |

| H. cannabinus | 2n = 36 | 1.1 | 66,004 | Zhang et al., 202039 |

| H. hamabo | 2n = 92 | 1.7 | 107,309 | Wang et al., 202240 |

Several key genes in flavonol and anthocyanin biosynthesis were detected from DEGs. The genes htrionum.r.g38784 and htrionum.r.g70916 were specifically expressed in the purple region, while htrionum.r.g31425 was promoted only in the light yellow region. The former two genes and the latter gene were putative orthologs of AtDFR and AtFLS1, which are responsible for the synthesis of leucoanthocyanidin (leading to anthocyanin biosynthesis) and flavonols from dihydroflavonol, respectively (Fig. 2B). The genes htrionum.r.g3974 and htrionum.r.g54284, which show increased expression in the purple region, were assigned to ortholog groups of AtUGT78Ds and AtUF3GT, respectively, both involved in the subsequent anthocyanin biosynthesis. The former, htrionum.r.g3974, showed the highest similarity to AtUGT78D2 (one of the FGTs), and its mutant showed reduced anthocyanin content.41 The latter, htrionum.r.g54284, showed the closest similarity to AtUGT79B3 (one of the AGTs), which is known to increase anthocyanin accumulation through its overexpression.42 In addition, htrionum.r.g54284 was also predicted to be orthologous to the I. nil gene INIL03g17665 (Dusky) (OG 0000422 shown in Supplementary Table S3). Dusky encodes anthocyanidin 3-O-glucoside-2″-O-glucosyltransferase (3GGT), and its mutant showed reddish-brown flowers with reduced purple coloration.43 These findings suggest that the accumulation of anthocyanins and flavonols in the purple and light yellow regions is regulated by the expression of the above genes, contributing to the colors observed in each petal region (Fig. 2B). Note that htrionum.r.g3974 may be involved in flavonol biosynthesis, as it also shows similarity to AtUGT78D1, which encodes an FGT that uses flavonols as substrates.44

Regarding cuticle components, a total of 10 genes were detected by OrthoFinder as the SHINE clade of AP2 domain transcription factors. In Arabidopsis, AtSHINE1, AtSHINE2, and AtSHINE3, are known to promote a brilliant or shiny green leaf surface with increased cuticular wax,45 and Moyroud et al. (2022)5 focused on this clade as the candidate factors for fine ridge formation in H. trionum. In addition to the several genes reported by Moyroud et al. (2022),5 we newly detected two putative orthologs of AtSHINE1, htrionum.r.g51082, and htrionum.r.g73448 with a high bootstrap support in the phylogenetic analysis (Supplementary Fig. S4). Among the 10 candidates, only htrionum.r.g51082 was highly expressed in the purple region (Supplementary Table S9) and is a promising candidate for fine ridge formation.

The AtCUS2-like genes, htrionum.r.g2803 and htrionum.r.g8620, were highly up-regulated in the purple region but had almost no expression in the light-yellow region, with expression ratios exceeding 1,000-fold. AtCUS2 is known to play a crucial role in the development of ridge structures during sepal growth.46 We also observed a drastic difference in the thickness of the extracellular matrix between the two regions (Fig. 1D). Although the cell wall and cuticle layers were unclear by transmission electron microscopy, the amount of cutin components in the cuticle layer likely reflects the results of the intense expression of these genes to form ridge structures. The pathway analysis revealed that the synthesis of 10,16-DHPA, polyhydroxy-fatty acid, and 16-feruloyloxypalmitic acid was up-regulated in the purple region (Fig. 2A). Mazurek et al. (2017)47 reported a clear correlation between the amount of 10,16-DHPA and the cuticular ridges on the conical cells of Arabidopsis petals, suggesting that the AtCYP77A-like gene, htrionum.r.g77092, is also responsible for the ridges. Omega-hydroxypalmitate O-feruloyl transferase (HHT), which synthesizes 16-feruloyloxypalmitic acid, has been reported to function mainly in roots48 for wound-healing and sensitivity to salt stress.49,50 It is unclear whether AtRWP1 (encoding HHT1)-like gene, htrionum.r.g41935, is involved in the formation of the ridge structures. In contrast, the synthesis of ω-oxo fatty acid was up-regulated in the light yellow region (Fig. 2A), suggesting that the cutin and suberin composition in the cuticle may differ significantly between the purple and light yellow regions. This difference may contribute to the absence/presence of fine structures on the petal surface.

As mentioned above, mechanical stress associated with cell elongation has been reported to be important for the formation of fine structures.4,5 In H. trionum petals, cells in the purple regions were elongated in the proximal–distal direction, while those in the light yellow regions showed conical shapes.2,3 In the purple regions, AtXTH30-like (htrionum.r.g22645) and AtGA20ox-like (htrionum.r.g53103) genes, which are involved in tissue development and elongation,51–54 were up-regulated. In addition, the pectate lyase-like gene htrionum.r.g34263 was highly expressed only in the purple regions, which are also likely to be involved in tissue elongation. On the other hand, the AtMYB16-like gene (htrionum.r.g50021), which regulates epidermal conical cells in petals,32 was up-regulated in the light yellow region. The change in cell shape in each region may affect the formation of fine structures. Genes involved in axis determination were also up-regulated in the light yellow region.

It is also worth noting one of the highly expressed DEGs in the purple region, htrionum.r.g22045. This gene had yellow flags (no expression in light yellow) and orange flags (a >100-fold change) and showed high similarity to a hypothetical protein in Gossypium stocksii. While no genes showed high similarity in A. thaliana, the gene also formed an ortholog group (OG0007627 shown in Supplementary Table S3) with the A. thaliana genes AT2G20870 and AT4G28160. The functions of these A. thaliana genes are still unclear. Therefore, the function of htrionum.r.g22045 awaits further investigation.

We performed genome, transcriptome, and pathway analyses and we successfully identified promising candidate genes involved in the formation of the fine structures on the epidermal cells in H. trionum petals. This plant grows easily in a laboratory and has a lifecycle of only about 2 months. With its genome sequence, H. trionum can be a useful model plant for molecular analysis of ridge formation. Analyzing the molecular functions of the identified genes and elucidating the mechanisms of fine structure formation are our next research tasks.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank T. Mochizuki and M. Sakamoto at NIG for advice on genome assembly and genome annotation, K. Yoshimoto (Meiji Univ.) for experimental support, K. Fukushima (Würzburg Univ.) for providing the genomic DNA isolation method, and T. Takeuchi, A. Kawada, K. Kuzunishi, and C. Takagi at NIBB for plant culture. We also thank the botanical gardens of Osaka Metropolitan University (Osaka, Japan), Tokyo Metropolitan Medicinal Plants Garden (Tokyo, Japan), Tokyo Metropolitan Kiba Park (Tokyo, Japan), and Shigei Medicinal Plants Garden (Kurashiki, Japan) for providing H. trionum seeds. Computations were partially performed on the NIG supercomputer at the ROIS National Institute of Genetics and the Data Integration and Analysis Facility at the National Institute for Basic Biology. Plant culture and SEM observation were supported by the Model Plant Section of the Model Organisms Facility and Optics and Imaging Facility in the NIBB Trans-Scale Biology Center. This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI grants to K.S. (20H05909), a JST ACT-X grant to S.K. (JPMJAX21B6), a grant from Sapporo Bioscience Foundation to S.K., and the NIBB Collaborative Research Program to S.K. (20-341, 21-223, 22NIBB308, and 23NIBB314).

Contributor Information

Shizuka Koshimizu, Bioinformation and DDBJ Center, National Institute of Genetics, Mishima 411-8540, Japan; Graduate Institute for Advanced Studies, SOKENDAI, Mishima 411-8540, Japan.

Sachiko Masuda, Center for Sustainable Resource Science, RIKEN, Yokohama 230-0045, Japan.

Arisa Shibata, Center for Sustainable Resource Science, RIKEN, Yokohama 230-0045, Japan.

Takayoshi Ishii, Arid Land Research Center, Tottori University, Tottori 680-001, Japan.

Ken Shirasu, Center for Sustainable Resource Science, RIKEN, Yokohama 230-0045, Japan.

Atsushi Hoshino, National Institute for Basic Biology, Okazaki 444-8585, Japan; Graduate Institute for Advanced Studies, SOKENDAI, Okazaki 444-8585, Japan.

Masanori Arita, Bioinformation and DDBJ Center, National Institute of Genetics, Mishima 411-8540, Japan; Graduate Institute for Advanced Studies, SOKENDAI, Mishima 411-8540, Japan.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author contributions

S.K. and M.A. conceived and designed the research in general. S.K. and A.H. performed and supervised the experiments. T.I. performed the chromosome observation. S.M., A.S., and K.S. performed the sequencing and assembly of the genome. S.K. and M.A. performed and supervised the computational analyses. All authors provided comments on the manuscript.

Data availability

The raw sequence reads have been deposited at DDBJ/ENA/GenBank under accession number PRJDB15920. The genome sequence has also been deposited at DDBJ/ENA/GenBank under accession number BSYR00000000.1 (BSYR01000001-BSYR01000276), and the assembly data can be accessed under accession number GCA_030270665.1. The genome sequence and the annotation are available at Zenodo (https://zenodo.org/record/8100923). The gene IDs corresponding to each gene mentioned in this paper are listed in the Supplementary Table S10.

References

- 1. Da-Costa-Rocha, I., Bonnlaender, B., Sievers, H., Pischel, I., and Heinrich, M.. 2014, Hibiscus sabdariffa L. – a phytochemical and pharmacological review, Food Chem., 165, 424–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Vignolini, S., Moyroud, E., Hingant, T., et al. 2015, The flower of Hibiscus trionum is both visibly and measurably iridescent, New Phytol., 205, 97–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Moyroud, E., Wenzel, T., Middleton, R., et al. 2017, Disorder in convergent floral nanostructures enhances signalling to bees, Nature, 550, 469–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Airoldi, C.A., Lugo, C.A., Wightman, R., Glover, B.J., and Robinson, S.. 2021, Mechanical buckling can pattern the light-diffracting cuticle of Hibiscus trionum, Cell Rep., 36, 109715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Moyroud, E., Airoldi, C.A., Ferria, J., et al. 2022, Cuticle chemistry drives the development of diffraction gratings on the surface of Hibiscus trionum petals, Curr. Biol., 32, 5323–5334.e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Inglis, P.W., Marilia de Castro, R.P., Resende, L.V., and Grattapaglia, D.. 2018, Fast and inexpensive protocols for consistent extraction of high quality DNA and RNA from challenging plant and fungal samples for high-throughput SNP genotyping and sequencing applications, PLoS One, 13, e0206085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cheng, H., Concepcion, G.T., Feng, X., Zhang, H., and Li, H.. 2021, Haplotype-resolved de novo assembly using phased assembly graphs with hifiasm, Nat. Methods, 18, 170–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Simão, F.A., Waterhouse, R.M., Ioannidis, P., Kriventseva, E.V., and Zdobnov, E.M.. 2015, BUSCO: assessing genome assembly and annotation completeness with single-copy orthologs, Bioinformatics, 31, 3210–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hoff, K.J., Lange, S., Lomsadze, A., Borodovsky, M., and Stanke, M.. 2016, BRAKER1: unsupervised RNA-Seq-based genome annotation with GeneMark-ET and AUGUSTUS, Bioinformatics, 32, 767–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Brůna, T., Hoff, K.J., Lomsadze, A., Stanke, M., and Borodovsky, M.. 2021, BRAKER2: automatic eukaryotic genome annotation with GeneMark-EP+ and AUGUSTUS supported by a protein database, NAR Genom. Bioinform., 3, 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kuznetsov, D., Tegenfeldt, F., Manni, M., et al. 2023, OrthoDB v11: annotation of orthologs in the widest sampling of organismal diversity, Nucleic Acids Res., 51, D445–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gabriel, L., Hoff, K.J., Brůna, T., Borodovsky, M., and Stanke, M.. 2021, TSEBRA: transcript selector for BRAKER, BMC Bioinf., 22, 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Pertea, G. and Pertea, M.. 2020, GFF utilities: GffRead and GffCompare, F1000Res, 9, 304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Altschul, S.F., Madden, T.L., Schäffer, A.A., et al. 1997, Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs, Nucleic Acids Res., 25, 3389–402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Camacho, C., Coulouris, G., Avagyan, V., et al. 2009, BLAST+: architecture and applications, BMC Bioinf., 10, 421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Emms, D.M. and Kelly, S.. 2019, OrthoFinder: phylogenetic orthology inference for comparative genomics, Genome Biol., 20, 238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Paysan-Lafosse, T., Blum, M., Chuguransky, S., et al. 2023, InterPro in 2022, Nucleic Acids Res., 51, D418–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Jin, J., Tian, F., Yang, D.C., et al. 2017, PlantTFDB 4.0: toward a central hub for transcription factors and regulatory interactions in plants, Nucleic Acids Res., 45, D1040–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Simon, A. 2010, FastQC: a quality control tool for high throughput sequence data. Available online at: http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/.

- 20. Martin, M. 2011, Cutadapt removes adapter sequences from high-throughput sequencing reads, EMBnet J., 17, 10. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Li, B. and Dewey, C.N.. 2011, RSEM: accurate transcript quantification from RNA-Seq data with or without a reference genome, BMC Bioinf., 12, 323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Dobin, A., Davis, C.A., Schlesinger, F., et al. 2013, STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner, Bioinformatics, 29, 15–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sun, J., Nishiyama, T., Shimizu, K., and Kadota, K.. 2013, TCC: an R package for comparing tag count data with robust normalization strategies, BMC Bioinf., 14, 219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kanehisa, M. and Goto, S.. 2000, KEGG: kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes, Nucleic Acids Res., 28, 27–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Katoh, K. and Standley, D.M.. 2013, MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: improvements in performance and usability, Mol. Biol. Evol., 30, 772–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Tamura, K., Stecher, G., and Kumar, S.. 2021, MEGA11: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 11, Mol. Biol. Evol., 38, 3022–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Jones, D.T., Taylor, W.R., and Thornton, J.M.. 1992, The rapid generation of mutation data matrices from protein sequences, Bioinformatics, 8, 275–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hugh Davie, J. 1933, Cytological studies in the Malvaceae and certain related families, J. Genet., 28, 33–67. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Skovsted, A. 1935, Chromosome numbers in the Malvaceae. I, J. Genet., 31, 263–96. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Rao, L.N. 1941, Cytology of Hibiscus trionum, New Phytol., 40, 326–35. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Murray, B.G., Craven, L.A., and De Lange, P.J.. 2010, New observations on chromosome number variation in Hibiscus trionum s.l. (Malvaceae) and their implications for systematics and conservation, N. Z. J. Bot., 46, 315–9. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Baumann, K., Perez-Rodriguez, M., Bradley, D., et al. 2007, Control of cell and petal morphogenesis by R2R3 MYB transcription factors, Development, 134, 1691–701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Waki, T., Mameda, R., Nakano, T., et al. 2020, A conserved strategy of chalcone isomerase-like protein to rectify promiscuous chalcone synthase specificity, Nat. Commun., 11, 1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Morita, Y., Takagi, K., Fukuchi-Mizutani, M., et al. 2014, A chalcone isomerase-like protein enhances flavonoid production and flower pigmentation, Plant J., 78, 294–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Guan, D., Guan, D., McCarthy, S.A., et al. 2020, Identifying and removing haplotypic duplication in primary genome assemblies, Bioinformatics, 36, 2896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Eriksson, J.S., Bacon, C.D., Bennett, D.J., Pfeil, B.E., Oxelman, B., and Antonelli, A.. 2021, Gene count from target sequence capture places three whole genome duplication events in Hibiscus L. (Malvaceae), BMC Ecol. Evol., 21, 1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kim, Y.M., Kim, S., Koo, N., et al. 2017, Genome analysis of Hibiscus syriacus provides insights of polyploidization and indeterminate flowering in woody plants, DNA Res., 24, 71–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Yang, Y., Liu, X., Shi, X., et al. 2022, A high-quality, chromosome-level genome provides insights into determinate flowering time and color of cotton rose (Hibiscus mutabilis), Front. Plant Sci., 13, 230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Zhang, L., Xu, Y., Zhang, X., et al. 2020, The genome of kenaf (Hibiscus cannabinus L.) provides insights into bast fibre and leaf shape biogenesis, Plant Biotechnol. J., 18, 1796–809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wang, Z., Xue, J.Y., Hu, S.Y., et al. 2022, The genome of Hibiscus hamabo reveals its adaptation to saline and waterlogged habitat, Hortic. Res., 9, uhac067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Tohge, T., Nishiyama, Y., Hirai, M.Y., et al. 2005, Functional genomics by integrated analysis of metabolome and transcriptome of Arabidopsis plants over-expressing an MYB transcription factor, Plant J., 42, 218–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Li, P., Li, Y.J., Zhang, F.J., et al. 2017, The Arabidopsis UDP-glycosyltransferases UGT79B2 and UGT79B3, contribute to cold, salt and drought stress tolerance via modulating anthocyanin accumulation, Plant J., 89, 85–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Morita, Y., Hoshino, A., Kikuchi, Y., et al. 2005, Japanese morning glory dusky mutants displaying reddish-brown or purplish-gray flowers are deficient in a novel glycosylation enzyme for anthocyanin biosynthesis, UDP-glucose:anthocyanidin 3-O-glucoside-2ʹʹ-O-glucosyltransferase, due to 4-bp insertions in the gene, Plant J., 42, 353–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Jones, P., Messner, B., Nakajima, J.I., Schäffner, A.R., and Saito, K.. 2003, UGT73C6 and UGT78D1, glycosyltransferases involved in flavonol glycoside biosynthesis in Arabidopsis thaliana, J. Biol. Chem., 278, 43910–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Aharoni, A., Dixit, S., Jetter, R., Thoenes, E., Van Arkel, G., and Pereira, A.. 2004, The SHINE clade of AP2 domain transcription factors activates wax biosynthesis, alters cuticle properties, and confers drought tolerance when overexpressed in Arabidopsis, Plant Cell, 16, 2463–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Hong, L., Brown, J., Segerson, N.A., Rose, J.K.C., and Roeder, A.H.K.. 2017, CUTIN SYNTHASE 2 maintains progressively developing cuticular ridges in Arabidopsis sepals, Mol. Plant, 10, 560–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Mazurek, S., Garroum, I., Daraspe, J., et al. 2017, Connecting the molecular structure of cutin to ultrastructure and physical properties of the cuticle in petals of arabidopsis, Plant Physiol., 173, 1146–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Lotfy, S., Javelle, F., and Negrel, J.. 1995, Distribution of hydroxycinnamoyl-CoA: ω-hydroxypalmitic acid O-hydroxycinnamoyltransferase in higher plants, Phytochem., 40, 389–91. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Negrel, J., Lotfy, S., and Javelle, F.. 1995, Modulation of the activity of two hydroxycinnamoyl transferases in wound-healing potato tuber discs in response to pectinase or abscisic acid, J. Plant Physiol., 146, 318–22. [Google Scholar]

- 50. Gou, J.Y., Yu, X.H., and Liu, C.J.. 2009, A hydroxycinnamoyltransferase responsible for synthesizing suberin aromatics in Arabidopsis, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A., 106, 18855–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Nishitani, K. 1997, The role of endoxyloglucan transferase in the organization of plant cell walls, Int. Rev. Cytol., 173, 157–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Vissenberg, K., Martinez-Vilchez, I.M., Verbelen, J.P., Miller, J.G., and Fry, S.C.. 2000, In vivo colocalization of xyloglucan endotransglycosylase activity and its donor substrate in the elongation zone of Arabidopsis roots, Plant Cell, 12, 1229–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Rieu, I., Ruiz-Rivero, O., Fernandez-Garcia, N., et al. 2008, The gibberellin biosynthetic genes AtGA20ox1 and AtGA20ox2 act, partially redundantly, to promote growth and development throughout the Arabidopsis life cycle, Plant J., 53, 488–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Plackett, A.R.G., Powers, S.J., Fernandez-Garcia, N., et al. 2012, Analysis of the developmental roles of the Arabidopsis gibberellin 20-oxidases demonstrates that GA20ox1, -2, and -3 are the dominant paralogs, Plant Cell, 24, 941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The raw sequence reads have been deposited at DDBJ/ENA/GenBank under accession number PRJDB15920. The genome sequence has also been deposited at DDBJ/ENA/GenBank under accession number BSYR00000000.1 (BSYR01000001-BSYR01000276), and the assembly data can be accessed under accession number GCA_030270665.1. The genome sequence and the annotation are available at Zenodo (https://zenodo.org/record/8100923). The gene IDs corresponding to each gene mentioned in this paper are listed in the Supplementary Table S10.