Abstract

Introduction

Wandering spleen (WS) is a rare condition, occurring in only 0.2 % of cases, where the spleen becomes hypermobile due to the absence or laxity of its anchoring ligaments. Torsion of the spleen, primarily seen in children but occasionally in adults, is a critical complication that can lead to infarction and is considered a medical emergency.

Clinical presentation

We present a case report of a 50-year-old woman with type 2 diabetes and psychiatric illness presented with 2 days of vomiting, abdominal pain, and dehydration. Physical examination showed a tender mass in the abdomen and imaging confirmed a twisted spleen with a thrombosed splenic vein, leading to a successful emergency splenectomy. The patient had an uncomplicated recovery and was discharged with post-splenectomy protocol.

Discussion

Splenic torsion, a rare occurrence primarily observed in children. Clinical diagnosis is aided by palpable abdominal masses and confirmed by radiological imaging. The gold standard diagnostic tool is contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT), whereas Ultrasonography (USG) is equally good in early assessment. Early identification is crucial to salvage the spleen. Management options include detorsion, splenopexy, or splenectomy depending on the organ viability. Elective splenopexy has emerged as a proactive measure, particularly in children, to prevent complications.

Conclusion

Splenic torsion is a rare but important differential diagnosis in patients presenting with acute abdomen. Early diagnosis and prompt management is necessary to preserve the spleen and to prevent the development of complication. Surgery is often necessary and either splenopexy or splenectomy should be done.

Keywords: Acute abdomen, Splenic torsion case report, Wandering spleen, Splenectomy, Splenopexy

Highlights

-

•

Splenic torsion is rare and it is commonly observed in children with wandering spleen.

-

•

In the acute abdomen presentation with nonspecific parameters, splenic torsion should be considered as a differential diagnosis.

-

•

High suspicion and early intervention is necessary to preserve the lymphoid organ spleen.

-

•

Radiological modalities are very important in diagnosing splenic torsion, its complication and organ viability.

1. Introduction

Torsion of spleen in wandering spleen is a clinical rarity with a universal incidence of only 0.2 %. The spleen is the largest reticuloendothelial organ that develops as an outgrowth from the dorsal mesogastrium in the midline and reaches its location at the left upper quadrant of the abdomen with time. It is held in its final position by a group of constant and varying ligaments, namely the splenogastric, splenocolic, splenorenal, splenophrenic, spleno-omental, and splenopancreatic ligaments. Defects in this process of development lead to several congenital anomalies. The wandering spleen (WS) is a hypermobile but normal spleen due to the laxity or absence of the aforementioned anchoring ligaments that may undergo torsion [1,2,3]. In addition, a few acquired causes, including weak abdominal wall, multiple pregnancies, postpartum period, hormonal changes, and enlarged spleen, have also been described [4]. WS was first documented by a Polish clinician (Dr. Josef Dietl) in the mid-19th century, who also emphasized the elongation of the splenic pedicle in addition to congenital or acquired lax ligaments that contributes to the torsion and infarction of spleen, compromising the splenic vessels flow [1]. Splenic torsion most of the time noted in children, making congenital WS the commonest cause, with equal incidence in both genders. However few cases have been described in adults around their third decade of life with a preponderance of females [5,6]. Clinical presentation of wandering spleen is variable and the major complication is acute torsion with subsequent infarction, which is a fatal emergency [7]. This report was drafted in line with the SCARE 2020 criteria [8].

1.1. Case presentation

A 50-year-old female was brought to the emergency treatment unit with recurrent vomiting for 2 days duration with a vague abdominal pain. She is a diagnosed patient with type 2 diabetes mellitus and psychiatric illness. On admission, she had a blood pressure of 135/95 mmHg, a pulse rate of 100 bpm, a body temperature of 37 °C, oxygen saturation of 98 % on air and features of dehydration. A firm mass with mild to moderate tenderness over the left hypochondrium was noted on examination. It didn't have any specific features to suggest an organ of origin. Her random capillary blood glucose was 494 mg/dL, and it was managed medically. On routine blood investigations, she had leukocytosis with 16.67 × 109/L with 80.2 % neutrophils, hemoglobin of 12.5 g/dL, platelet count of 164 × 109/L, and her basic renal and liver profiles were unaltered. An urgent abdominal ultrasonography (USG of the abdomen) and plain film of abdomen (X-ray abdomen) was taken where plain film showed no significant abnormalities and USG of abdomen revealed a twisted spleen at the left hypochondrium with absent vascularity and a thrombosed splenic vein (Fig. 1, Fig. 2). Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CECT) of the abdomen and pelvis for detailed assessment revealed torsion of the spleen with a thrombosed splenic vein (Fig. 3, Fig. 4). Open splenectomy was done by the surgical team as the spleen was non-viable. Post-operative recovery was uneventful with no postoperative complications especially hemorrhage. Patient was started with prophylactic antibiotics. His clotting profile and platelet counts were normal on the post-op day 1. The clotting profile remained the same till discharge but there was a significant increase in platelet count. The patient was discharged on post-op day 9 with recommended post splenectomy vaccination schedule and clinic follow-up. Vaccination was started post-op day 16 and his blood parameters were normal.

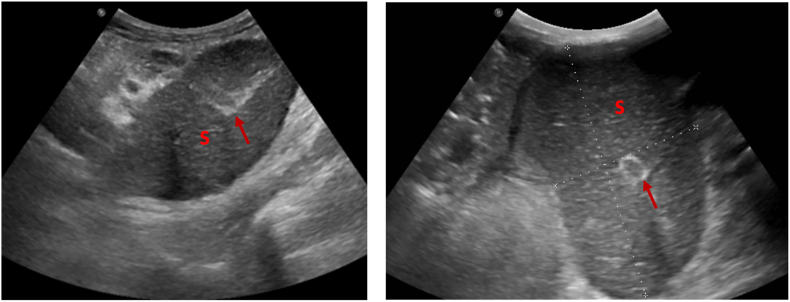

Fig. 1.

A and B - Ultrasound scan of abdomen showing torsion of splenic hilar vessel with absence of doppler flow. (A) Ultrasound image showing tissue oedema (B) Doppler study showing absence of blood flow.

Fig. 2.

A and B - Ultrasound scan of abdomen showing infarcted edematous spleen (S) with thrombosed vessel identified with in the spleen. (arrows indicate vein with thrombus).

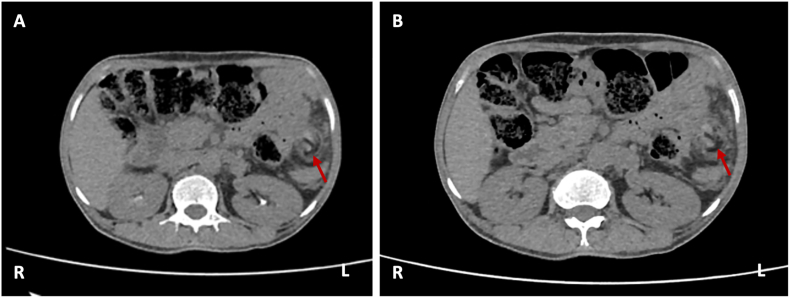

Fig. 3.

A and B - Non contrast CT scan shows torsion of hilar vessel of spleen with surrounding tissue edema. (arrows indicate the site of torsion). (R) denotes right side and (L) denotes left side.

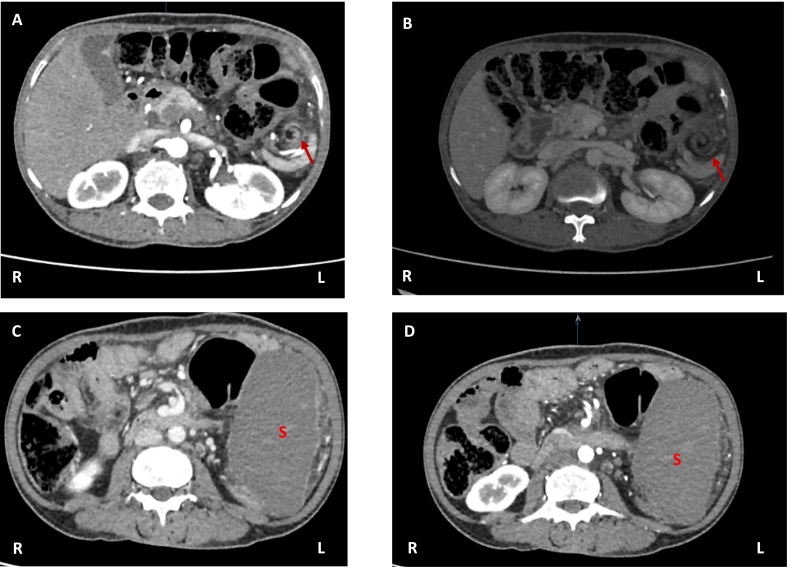

Fig. 4.

.Contrast enhanced CT scan with vascular bright window setting clearly demonstrated twisted splenic hilum with infarcted non enhancing spleen. (A) and (B) shows whorled appearance of the twisted pedicle (Arrow indicates the whorled appearance). (C) and (D) - shows non enhancing spleen (S) with peripheral capsular enhancement of white rim sign (“rim sign”). (R) denotes right side and (L) denotes left side.

2. Discussion

Splenic torsion is a rare clinical rarity which is commonly noted in children [7,9]. The wandering spleen (WS) is a hypermobile but normal spleen due to the laxity or absence group of ligaments which hold the spleen in its final position (splenogastric, splenocolic, splenorenal, splenophrenic, spleno-omental, and splenopancreatic ligaments) [1,2,3]. In addition, a few acquired causes, including weak abdominal wall, multiple pregnancies, postpartum period, hormonal changes, and enlarged spleen, have also been described [4].

Patients with wandering spleen may asymptomatic or present with mass in the abdomen or with acute or chronic abdominal pain [7]. Torsion is the most common complication and its manifestation depends on the extent of the torsion [4,7]. Varying degrees of pain arising from the stretched capsule or local inflammation of peritoneum is a common finding. Mild torsion presents with chronic abdominal pain with a congested spleen, while the moderate form complains of intermittent abdominal pain attributed to the intermittent twisting of the wandering spleen and severe form usually presents to the emergency unit with an acute abdomen. Symptoms in the severe form can present with manifestations of an infarcted unsalvageable spleen or compressed organs in original or ectopic vicinity [4]. Laboratory findings are usually nonspecific in splenic torsion; however, leukocytosis was noted in a case report [6].

Clinically, the diagnosis can be suspected when a firm, movable abdominal mass is felt with the typically “notched border”, however splenic engorgement can hide the splenic notch [10,11]. In this case acute abdomen, a nonspecific mass in the left hypochondrium raised a suspicious of splenic torsion.

The challenges faced in diagnosing splenic torsion solely on clinical grounds are overcome by imaging. Abdominal X-rays are nonspecific in case of splenic torsion [7], where some may show a soft tissue density anywhere in the abdomen displacing bowel loops. Therefore, the USG of the abdomen was performed. In the USG the spleen is a homogeneous organ in the left hypochondrium with echogenicity slightly higher than the renal cortex and slightly less than or equal to that of the liver parenchyma in a healthy adult. A torted spleen may lie at any quadrant of the abdomen with reduced or no intraparenchymal vascularity and with or without a splenic infarct. A splenic artery resistive index (RI) of more than 0.8 favors splenic infarction [2]. Though USG are helpful in diagnosis of wandering spleen and splenic torsion they can be hindered by bowel gas [7]. USG in this study revealed torsion of splenic hilar vessel with absence of doppler flow and Infarcted edematous spleen.

A non-contrast computed tomography (NCCT) is of minimal use in identifying a twisted or infarcted spleen. Contrast enhanced computed tomography (CECT) is the gold standard investigation. A torted spleen can lie in the original (anterior to the left kidney and posterior to the stomach in the left hypochondrium) or ectopic site (anywhere in the abdominal cavity) with or without infarction. Infarcted spleen is partially or non-enhancing [12], with a hyperdense capsule that serves like a white rim (“rim sign”), due to its preserved blood supply from the surrounding small blood vessels [13]. Rarely a whorled appearance of the twisted pedicle is noted in a CT, a pathognomonic sign CT finding of torsion, further aids in the diagnosis [14]. CT study of this case demonstrated twisted splenic hilum with torsion of hilar vessel, peripheral capsular enhancement of white rim (“rim sign”) and infarcted spleen with surrounding tissue edema. These findings of splenic vein thrombosis and infarction prompted us to go for the splenectomy.

MRI had been of use to assess a wandering spleen during pregnancy in few studies [15]. Use of sequential liver-spleen scintigraphy with 99mTc-Sn-colloid and blood-pool scintigraphy with 99mTc-RBC for assessment of splenic blood volume and location were also noted in few studies [16].

The main aim of early identification of splenic torsion is to preserve the organ before it undergoes infarction. The management depends on the vascularity of the organ at the time of diagnosis. An infarcted spleen with thrombosed vessels has to be excised, but a non-infarcted twisted spleen can be detorted and repositioned. De-torsion and splenopexy can be done by open laparotomy or laparoscopically [1]. Fixation of spleen is performed via the pedicle or omentum or by trans positioning the colonic flexure and gastrocolic ligament or by placing a mesh around the organ [7]. Splenectomy is necessary if there is splenic infarction, massively enlarged spleen, splenic vessel thrombosis, secondary hypersplenism, functional asplenia due to torsion or any suspicious of malignancy [17]. Most studies have revealed infarcted spleen at diagnosis that had to be removed, however early diagnosis of a wandering spleen especially in children have paved a place for elective splenopexy preventing complications and the loss of the lymphoid organ [6]. International and local guidelines had stated the importance of post splenectomy vaccination in order to prevent the life threatening infections caused by S. pneumoniae, N. meningitidis, and H. influenzae type b [18].

3. Conclusion

Torsion of spleen is a clinical rarity with a universal incidence of less than 0.2 % and a rare cause of abdominal pain. It is commonly an incidental finding through imaging due to its diverse spectrum of clinical presentation from being asymptomatic with a left hypochondriac mass to being an emergency admission with acute abdomen, with mostly unaltered biochemical parameters or with nonspecific biochemical parameters.

Challenges on early diagnosis conquered through advanced imaging modalities identified through the studies of individual case reports on this uncommon disorder has enabled surgeon to salvage the organ before vascular compromise and complication, hence reducing the mortality. In clinical setting, high level of suspicion, early diagnosis and intervention should be made to preserve spleen and prevent developing of threatening complications.

Statement of informed consent

Informed written consent was obtained from the patient in this case study for publication of this case report and relevant images.

Ethical approval

The ethics clearance was not necessary to this study because Teaching Hospital Jaffna Ethical Review Board (IRB) does not require ethical approval for reporting individual cases or case series.

Funding

None.

Author contribution

Study concept – Subunca R, Sriluxayini M and Vinojan S.

Data collection – Subunca R and Sriluxayini M.

Data analysis –Priyatharsan K, Mayorathan M and Heerthikan K.

Guarantor

Dr. Kuganathan Priyatharsan.

Department of Surgery, Faculty of Medicine, University of Jaffna, Sri Lanka.

Research registration number

1. Name of the registry: N/A.

2. Unique identifying number or registration ID: N/A.

3. Hyperlink to your specific registration (must be publicly accessible and will be checked): N/A.

Conflict of interest statement

There is no conflict of interest between the authors as everybody is aware of the work and participated actively and equally.

References

- 1.Puranik A.K., Mehra R., Chauhan S., Pandey R. Wandering spleen: a surgical enigma. Gastroenterol. Rep. Aug 2017;5(3):241–243. doi: 10.1093/gastro/gov034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gulati M., Suman A., Satyam Garg A. Torsion of wandering spleen and its adherence to the right ovary-an unusual cause of recurrent pain abdomen. J. Radiol. Case Rep. 2020;14(7):10–18. doi: 10.3941/jrcr.v14i7.3752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Udare A.S., Mondel P.K., Thapar V. Torsion of wandering spleen. Indian J. Gastroenterol. Oct 2013;32(3):211. doi: 10.1007/s12664-012-0188-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chawla S., Boal D.K.B., Dillon P.W., Grenko R.T. Splenic torsion. Radiographics. Mar 2003;23(2):305–308. doi: 10.1148/rg.232025110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hussain M., Deshpande R., Bailey S.T.R. Splenic torsion: a case report. Ann. R. Coll. Surg. Engl. 2010;92(5) doi: 10.1308/147870810X12699662980592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Viana C., Cristino H., Veiga C., Leão P. Splenic torsion, a challenging diagnosis: case report and review of literature. Int. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2018;44:212–216. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2018.02.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.El Bouhaddouti H., Lamrani J., Louchi A., El Yousfi M., Aqodad N., Ibrahimi A., et al. Torsion of a wandering spleen. Saudi J. Gastroenterol. 2010;16(4):288–291. doi: 10.4103/1319-3767.70618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Agha R.A., Franchi T., Sohrab C., Mathew G., Kirwan A., Thomas A., et al. The SCARE 2020 guideline: updating consensus surgical case report (SCARE) guidelines. Int. J. Surg. 2020;84(1):226–230. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.10.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Andrés Beatriz, Fernández-González Nuria. Acute torsion of wandering spleen: a rare cause of acute abdomen. Cir. Cir. 2012;80:283–286. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Matsumoto S., Mori H., Okino Y., Tomonari K., Yamada Y., Kiyosue H. Computed tomographic imaging of abdominal volvulus: pictorial essay. Can. Assoc. Radiol. J. 2004;55:297–303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fujiwara T., Takehara Y., Isoda H., Ichijo K., Tooyama N., Kodaira N., et al. Torsion of the wandering spleen: CT and angiographic appearance. J. Comput. Assist. Tomogr. 1995;19:84–86. doi: 10.1097/00004728-199501000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ben Ely A., Zissin R., Copel L., Vasserman M., Hertz M., Gottlieb P., et al. The wandering spleen: CT findings and possible pitfalls in diagnosis. Clin. Radiol. Nov 2006;61(11):954–958. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2006.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vancauwenberghe T., Snoeckx A., Vanbeckevoort D., Dymarkowski S., Vanhoenacker F.M. Imaging of the spleen: what the clinician needs to know. Singapore Med. J. 2015;56(3):133–144. doi: 10.11622/smedj.2015040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Swischuk L.E., Williams J.B., John S.D. Torsion of wandering spleen: the whorled appearance of the splenic pedicle on CT. Pediatr. Radiol. Oct 1993;23(6):476–477. doi: 10.1007/BF02012458. (1993 236) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yücel E., Kurt Y., Ozdemir Y., Gun I., Yildiz M. Laparoscopic splenectomy for the treatment of wandering spleen in a pregnant woman: a case report. Surg. Laparosc. Endosc. Percutan. Tech. Apr 2012;22(2):e102–e104. doi: 10.1097/SLE.0b013e318246beb5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shimizu M., Seto H., Kageyama M., Wei Wu Y., Nagayoshi T., Kamisaki Y., et al. The value of combined 99mTc-Sn-colloid and 99mTc-RBC scintigraphy in the evaluation of a wandering spleen. Ann. Nucl. Med. Aug 1995;9(3):145–147. doi: 10.1007/BF03165042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mohammadi A., Ghasemi-Rad M. Wandering spleen: whirlpool appearance in color doppler ultrasonography. A case report. Maedica. Mar 2015;10(1):58. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rubin Lorry G., Levin Myron J., Ljungman Per, Davies E. Graham, Avery Robin, Tomblyn Marcie, Bousvaros Athos, Dhanireddy Shireesha, Sung Lillian, Keyserling Harry, Kang Insoo. Executive summary: 2013 IDSA clinical practice guideline for vaccination of the immunocompromised host. Clin. Infect. Dis. 1 February 2014;58(3):309–318. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]