Abstract

Fucoidan is linked to a variety of biological processes. Differences in algae species, extraction, seasons, and locations generate structural variability in fucoidan, affecting its bioactivities. Nothing is known about fucoidan from the brown alga Dictyota bartayresiana, its anti-inflammatory properties, or its inherent mechanism. This study aimed to investigate the anti-inflammatory properties of fucoidan isolated from D. bartayresiana against LPS-induced RAW 264.7 macrophages and to explore potential molecular pathways associated with this anti-inflammatory effects. Fucoidan was first isolated and purified from D. bartayresiana, and then, MTT assay was used to determine the effect of fucoidan on cell viability. Its effects on reactive oxygen species (ROS) formation and apoptosis were also studied using the ROS assay and acridine orange/ethidium bromide fluorescence labelling, respectively. Molecular docking and molecular dynamics simulation studies were performed on target proteins NF-κB and TNF-α to identify the route implicated in these inflammatory events. It was observed that fucoidan reduced LPS-induced inflammation in RAW 264.7 cells. Fucoidan also decreased the LPS-stimulated ROS surge and was found to induce apoptosis in the cells. Molecular docking and molecular dynamics simulation studies revealed that fucoidan’s potent anti-inflammatory action was achieved by obstructing the NF-κB signalling pathway. These findings were particularly noteworthy and novel because fucoidan isolated from D. bartayresiana had not previously been shown to have anti-inflammatory properties in RAW 264.7 cells or to exert its activity by obstructing the NF-κB signalling pathway. Conclusively, these findings proposed fucoidan as a potential pharmaceutical drug for inflammation-related diseases.

Keywords: Apoptosis, Fucoidan, Inflammation, NF-κB, Reactive oxygen species, Sulphated polysaccharide, TNF-α

Introduction

Inflammation is a complicated and necessary biological procedure that arises in reaction to mechanical tissue damage, natural stimuli, or an abnormal autoimmune reaction (Mauriz et al. 2013; Wu et al. 2017). Due to the harmful effects of various inflammatory components, excessive inflammation can harm host organisms and cause several illnesses, including tumours, osteoarthritis, diabetes, septicaemia, and cardiovascular disease (Iwalewa et al. 2010; Wu et al. 2017). Macrophages possess two distinct morphologies: pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory, which are essential players in the reaction triggered by inflammation (Wang et al. 2018; Kim et al. 2020). Lipopolysaccharide (LPS), a constituent of the external cellular membranes and constituents of gram-negative bacterium, is an acknowledged endotoxin that may trigger macrophages to generate diverse inflammatory cytokines like interleukin-1 (IL-1), tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), and interleukin-6 (IL-6) (Kiemer et al. 2002; Zhang et al. 2015). As a result, blocking cytokine and mediator production by LPS-stimulated macrophages is constantly utilized to establish and test innovative anti-inflammatory medicines. Recently, drug research has frequently depended on using natural and synthetic pharmaceuticals to prevent or cure many disorders (Hariram Nile and Won Park 2013). Natural anti-inflammatory substances are gaining popularity since they have fewer adverse effects than manufactured medications (Sun et al. 2015; Wu et al. 2017). Many natural components, such as triptolide, resveratrol, and silymarin, are now used in clinical trials as anti-inflammatory medicines (Zhou et al. 2012; Zhang et al. 2013). Numerous medicinal and culinary plants are high in anti-inflammatory constituents, particularly flavonoids, which comprise multiple anti-inflammatory properties (Toker et al. 2004; Wang et al. 2014). By interacting through nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathways, flavonoids frequently affect signalling cascades of inflammation and suppress the production of cytokines like TNF-α, IL-1, and IL-6 (Chuang and McIntosh 2011; Zhang and Tsao 2016; Liu et al. 2016). The recently discovered energy-regulating peptide nesfatin-1, which is extensively expressed in central and peripheral tissues, has a wide range of physiological functions. Nesfatin-1 has antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and anti-apoptotic capabilities, and it has a role in the onset and development of many illnesses, according to a vast number of recent research. By reducing levels of lactate dehydrogenase, medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA), and malondialdehyde (MDA) and increasing levels of SOD (superoxide dismutase), CAT (catalase), and glutathione (GSH), the nesfatin-1 treatment inhibits intracellular ROS (reactive oxygen species) excessive production. It maintains the balance of oxidant/antioxidant systems and suppresses free radical formation (Xu and Chen 2020). Despite having minimal anti-tumour potential, the antibacterial activity of silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) is also evident. There are studies focussed to ascertain the cytotoxic effects of AgNPs on Michigan Cancer Foundation-7 (MCF-7) breast cancer cells and the associated mechanism of cell death. This method makes new materials that might be used in nano-medicine as an alternative therapeutic therapy for human breast cancer. Therefore, more research is required to thoroughly understand the anticancer efficacy and toxicity mechanisms of AgNPs. In place of chemical and physical procedures, biological approaches have been developed employing plants and microorganisms such bacteria, actinobacteria, moulds, yeast, and algae (Subbaiya et al. 2017).

Algae research has expanded beyond biodiesel production to explore new prebiotics and chemicals with unique structures and bioactivities. These small molecules and secondary metabolites have anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, antimicrobial, and anti-tumour properties. Examples of these molecules include phenolic chemicals, polysaccharides, carotenoids, and polyunsaturated fatty acids along with phlorotannins from brown seaweeds and microalgae’s terpenoids and peptides. Brown seaweeds (Phaeophyta) generate a variety of polysaccharides, including alginates, laminarans, and fucoidans. These polysaccharides, which mostly comprise L-fucose and sulphate, have been researched for their biological effects, which include anticoagulant, antithrombotic, anti-inflammatory, anti-tumoral, contraceptive, apoptotic, antioxidant, and antiviral characteristics. Their biological functions have been thoroughly explored, and they are regarded as significant resources for a variety of applications (Rabanal et al. 2014).

Dictyota is a brown alga, often referred to as a forded sea tumbleweed (Aisha and Maryam 2019), found in the tropical western Indo-Pacific area and the Gulf of Mexico. It comprises substances being studied for potential application, such as larvicides and antimicrobials. Individuals of this genus were shown to produce structurally varied secondary metabolites that have a protective quality, which significantly aids in their ability to survive and procreate in various challenging maritime habitats (Taylor et al. 2003). Hundreds of bioactive natural chemicals, including phenolic compounds, flavonoids, fatty acids, polyphenols, and polysaccharides, have been found in Dictyota (Ragan and Jensen 1977; Abdel-Fattah et al. 1978; Bouzidi et al. 2008; Martins et al. 2016). A sulphated polysaccharide called fucoidan is present in several species of brown algae. Fucoidan is now used in a wide variety of items on the market, including nutritional supplements, cosmetic products, surgical instruments, therapeutic food and beverages and animal healthcare. Fucoidan is also used in healthcare and pharmaceutical research. Algae-derived fucoidans have been studied intensively during the last years regarding their multiple biological activities and possible therapeutic potential. However, the source, species, molecular weight, composition, structure of the polysaccharides, and route of administration of fucoidan could be crucial for their effects. According to reports, fucoidan affects many phases of inflammation, including (1) limiting lymphocyte adhesion and invasion, (2) inducing apoptosis, and (3) inhibiting several enzymes (Apostolova et al. 2020). In a study, it was reported that the fucoidan extracted from Saccharina japonica showed an anti-inflammatory impact by inhibiting the production of inflammatory cytokines, including TNF-α, IL-1, and IL-6 as well as other mediators like iNOS and COX-2 (Ye et al. 2020). However, it is now recognized that fucoidan possesses many biological activities, including antioxidant, antibacterial, and cytotoxic capabilities. So, in this study, fucoidan isolated from the brown seaweed Dictyota bartayresiana was checked for potent anti-inflammatory activity in lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-stimulated RAW 264.7 cells for the first time making it a novel study, followed by an exploration of the mechanism of action behind this anti-inflammatory activity using both experimental and computational approaches.

Materials and methods

Isolation and purification of fucoidan

The sulphated polysaccharide (fucoidan) was isolated from the brown seaweed D. bartayresiana using a standard protocol. Using column chromatography, fucoidan, the sulphated polysaccharide, was purified from Dictyota bartayresiana (Dubey and Sivaraman 2022).

Cell culture and cell cytotoxicity assay

The MTT assay was conducted using standard protocols. RAW 264.7, that is a mouse macrophage cell line, was acquired from the National Centre for Cell Science (NCCS, Pune). These cells were cultured and incubated at around 37 °C and 5% CO2 in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% foetal bovine serum (FBS) and antibiotics (penicillin and streptomycin). On a 96-well plate, approximately 5 × 103 cells were seeded per well. These cells were subjected to lipopolysaccharide (LPS) treatment (1 µg/well), and after an hour, drug treatment was done and was again cultured for 24 h. Fucoidan was administered to the cells with final concentrations ranging from 10 to 45 µg/ml. The negative control was dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), while the blank control was cells without treatment. Cells were treated 24 h before incubating for 4 h with an 3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl]2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) at 37 °C and CO2 (5%). DMSO was also added at the end of the treatment. Subsequently, absorbance at 570 nm was observed using a microtiter plate reader.

Intracellular ROS measurement

To monitor changes in the intracellular amount of ROS, the fluorescent probe 2ʹ-7ʹ-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (DCFDA), which is a hydrogen peroxide-specific probe, was employed. In short, 2 × 105 cells/well were cultivated in 6 well plates for around 24 h in CO2 (5%) at 37 °C. Following incubation, lipopolysaccharide (1 µg/ml) was added. After one hour of incubation, sulphated polysaccharide (35 µg/ml) was added to the wells prior to being treated by DCFDA (10 mmol/L) at 37 °C for nearly 20 min against suitable control. Cells were therefore harvested, rinsed, and re-suspended three times in DMEM without FBS. Flow cytometry computed the DCF fluorescence in cells, with the excitation source wavelength of 488 nm and the emission wavelength of 525 nm.

Apoptosis assay

The apoptosis in these cells was assessed by dual acridine orange/ethidium bromide (AO/EtBr) fluorescent staining. In brief, 2 × 105 RAW 264.7 cells per well were grown in the plate (6-well), cultured for 24 h, and then exposed to different drug concentrations against suitable control. Additionally, a PBS wash and removal of the supernatant were performed. Following that, approximately 6 µl of AO was poured into each well, and the plates were left incubating for 10 min. After another wash in PBS, 5 µl of EtBr was added, and the cells were seen under fluorescence microscopy after a 5-min incubation.

Computational analysis

Fucoidan has anti-inflammatory properties, and experiments using molecular docking and molecular dynamics simulation were conducted to identify the mechanism involved.

Molecular docking studies

The protein needed for molecular docking studies was NF-κB P50 homodimer bound to DNA with PDB ID-1SVC and crystal structure of TNF-α with a small molecule inhibitor with PDB ID-2AZ5. Protein Data Bank was utilized to derive the protein structure. Fucoidan was the ligand employed in the study, while PubChem provided the ligand’s structure. Prior to docking, the protein and ligands structures were produced. The ligand was generated using the Lig prep module of the Schrodinger suite, whereas the proteins structures were generated with the Schrodinger suite’s Protein preparation wizard. Glide was utilized to execute docking after the preparation of the ligand and protein. After molecular docking, the glide score and binding energies were recorded.

Molecular dynamics simulation studies

For simulation studies, the Schrodinger suite’s Desmond program was utilized. Both complexes produced from molecular docking investigations were subjected to simulation experiments. A constant-temperature, constant-pressure ensemble (NPT) ensemble having temperature (300 K) and pressure (1 bar) was used during all the runs. For the ligands 1SVC and 2AZ5, the simulation period was 100 ns. All simulations utilized the optimized potentials for liquid simulations (OPLS 2005) force field settings. The root mean square deviation (RMSD) plots were used to evaluate the sustainability of molecular dynamics (MD) simulations.

Statistical analysis

All measurements were analysed in independent triplicate and presented as the mean ± standard deviation.

Results

As mentioned earlier, marine algae have countless advantages in pharmaceutics, food, and cosmetics. They are also known as a remedial measure against numerous deadly diseases and have wide-ranging benefits in almost all fields (Costa et al. 2010; Na et al. 2010). Nowadays, it has been noticed that researchers are focussing much on polysaccharides extracted from natural sources, including plants and seaweeds, since they have several bioactive properties such as anti-inflammatory, anti-tumour, anti-oxidative, antimicrobial and antiviral properties, thus, in the present investigation, a sulphated polysaccharide (fucoidan) isolated from D. bartayresiana was subjected for evaluation of anti-inflammatory properties. The extracted sulphated polysaccharide was purified using ion chromatography using Sephadex A-50 column, and eluents were pooled in different fractions. In our previous study, the carbohydrate and sulphate estimated in purified fucoidan fraction F1 was 1526.48 µg/ml, while the sulphate content obtained was 70.4 mg/ml. Now, to identify the structural and chemical details of the extracted sulphated polysaccharide, this was subjected to characterization studies by nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) and Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) analyses as the chemical and structural identification also forms a substantial distinguishing element in the extraction process. The peaks obtained from 13C NMR were analogous to the sulphated polysaccharide fucoidan, the promising polysaccharide acquired from brown algae. Thus, it can be stated that the sulphated polysaccharide extracted from D. bartayresiana was fucoidan. The results obtained from FTIR analysis were concordant with those obtained from NMR, thus confirming the extracted sulphated polysaccharide to be fucoidan (Dubey and Sivaraman 2022). Since fucoidan is acknowledged for several therapeutic applications such as neuroprotective, anti-diabetic, and anticoagulant activity, we intended to perform this search for NF-κB and TNFα inhibitors and explore fucoidan’s anti-inflammatory actions in lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-stimulated RAW 264.7 cells.

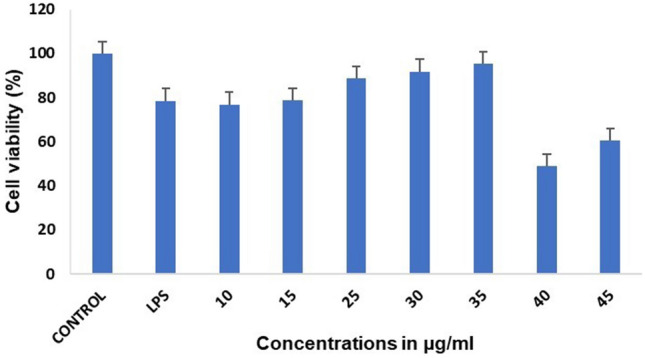

Effects of fucoidan on the viability of RAW 264.7 cells

The ability of viable mitochondria to metabolize the MTT salt into the formazan product via a reduction process catalysed by succinate dehydrogenase is frequently used to assess the cytotoxicity of chemicals to cells (dos Santos Nunes et al. 2019). The result is interpreted as cytotoxic, protective, or neutral in the presence of bioactive substances. In the present study, the cell viability was assessed using an MTT assay to evaluate the cytotoxic effects of fucoidan in the current investigation, where RAW264.7 cells were given with LPS (1 µg/ml) and fucoidan (10–45 µg/ml) for 24 h to assess the cytotoxic effects of fucoidan. The MTT assay demonstrated that LPS displayed cytotoxic effects at dosages up to 1 µg/ml at 24 h compared to control cells without treatment. When the cells were exposed to LPS, their viability began to drop to 78%. Fucoidan had no cytotoxic effects at dosages as high as 15 µg/ml. When the fucoidan concentration was increased to 25–35 µg/ml, cell viability increased but fell to 40–45 µg/ml. Cell viability grew to 90–95% so that the cells could attenuate LPS-induced inflammation at approximately 30–35 µg/ml. The increase in cell viability percentage was found to increase dose-dependently at around 30–35 µg/ml. As a result, we limited the concentration of fucoidan in subsequent testing to 30–35 µg/ml, as seen in Fig. 1. The IC50 value obtained in this case was 35 µg/ml. Therefore it can be stated that fucoidan extracted from D. bartayresiana enhanced the cell viability percentage, indicating that fucoidan could reduce LPS-induced inflammation and hence be regarded as a potent anti-inflammatory drug.

Fig. 1.

Fucoidan’s effects on cell viability were measured in RAW 264.7 cells using the MTT test. When the fucoidan concentration was increased to 25–35 µg/ml in LPS-treated cells, the cell viability percentage rose, indicating a decrease in LPS-induced inflammation

In previous studies, fucoidan fraction 6 of Viscozyme-assisted hydrolysate from E. maxima stipe (EMSF6) inhibited inflammation via regulating pro-inflammatory cytokines and the protein expression of iNOS and COX-2 in LPS-induced RAW 264.7 cells (Lee et al. 2022). In another study, fucoidans from five brown seaweeds were extracted and characterized and their anti-inflammatory properties were examined in-vitro. For the first time, it was discovered that the anti-inflammatory effect of fucoidan may be mediated by inhibiting protein denaturation using the model of the denaturation of egg albumin (Obluchinskaya et al. 2022). In a rat model of paw inflammation caused by histamine, fucoidan from Cystoseira crinita showed an anti-inflammatory action. After LPS exposure, this sulphated polysaccharide reduced the levels of several pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-1 and TNF-α) but did not affect the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10. Another study investigated the biological activity of a sulphate polysaccharide isolate derived from the brown algae Sargassum polycystum. The findings revealed that the sulphate polysaccharide exhibited anti-inflammatory properties and could potentially prevent and treat cardiovascular disease (Manggau et al. 2022).

Intracellular ROS measurement

Redox reactions trigger the production of ROS, such as superoxide, in addition to peroxides. ROS may interact with lipids, proteins, DNA, and other molecules to harm biomolecules. To determine the inhibitory effect of fucoidan on oxidative damage, the next phase in this investigation was measuring ROS formation through flow cytometry in RAW 264.7 cells stimulated by LPS. It was discovered that ROS production dramatically increased when LPS stimulated the cells. It was observed that treatment with 35 µg/ml fucoidan led to a statistically significant reduction in ROS generation, similar to a decrease in Indomethacin (positive control). Figure 2 shows that ROS generation was raised in LPS-treated cells by up to 84%, which decreased up to 66.8% in positive control (Indomethacin) and up to 65.8% in fucoidan-treated cells. These results indicated that fucoidan prevented oxidative damage effectively by inhibiting ROS production in activated macrophages.

Fig. 2.

Flow cytometry was used to assess intracellular ROS where control cells produced 69.81% of the ROS, LPS-treated cells had 84.23% of the ROS, and fucoidan dramatically decreased ROS generation in LPS-stimulated cells to 65–66%

It has been observed that the overproduction of inflammatory mediators induces the pathophysiology of inflammatory illnesses due to reactive oxygen species (ROS) formation (Kauppinen et al. 2013). As a result, the downregulation of pro-inflammatory factors is regarded as an effective therapeutic strategy for treating inflammation-related disorders. In the present study, fucoidan was found to downregulate ROS production, thus indicating promising results and efficient anti-inflammatory actions. In a study, it was found that purified fucoidan (SAF3) from S. autumnale also possessed an anti-inflammatory effect against LPS-induced inflammation as in RAW 264.7 macrophage cells, SAF3 dramatically reduced the generation of NO, PGE2, and pro-inflammatory cytokines such TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1 followed by iNOS and COX2 downregulation. It was found that NF-κB and MAPK were associated with the anti-inflammatory action (Lee et al. 2022). Another study discovered the sulphated heteropolysaccharide Sargassum Zhangii fucoidan (SZF) has unreported potential. Due to SZF’s immune-stimulating properties, NO production in RAW 264.7 cells was increased through the dose-dependent up-regulation of iNOS and COX-2 protein and mRNA expression. In contrast, NO production in macrophages was decreased by commercial fucoidans from Undaria pinnatifida and Fucus vesiculosus (Li et al. 2023). On the other hand, Sargassum fucoidan (SHF) polysaccharide was isolated and showed outstanding immune-stimulatory action. By elevation of COX-2 and iNOS levels based on gene expression and protein abundance, an immune-stimulating test demonstrated that SHF could considerably boost NO production in macrophage RAW 264.7 cells. These findings indicate a significant potential for SHF extracted from Sargassum hemiphyllum to operate as a health-improving component in the pharmaceutical and functional food industries. Overall conclusions based on our research and prior studies showed that fucoidan effectively reduced LPS-induced inflammation and ROS generation.

Apoptosis assay

Another experiment set included apoptosis detection by dual acridine orange/ethidium bromide (AO/EtBr) fluorescent staining. AO/EtBr staining is a valuable tool for distinguishing between live, apoptotic, and dead cells based on their distinctive fluorescence patterns. Live cells fluoresce green due to intact lysosomal accumulation of AO, early apoptotic cells emit orange/red fluorescence due to disrupted lysosomes and nuclear changes, and dead cells emit red fluorescence due to EtBr binding to DNA after complete membrane breakdown. This technique provides researchers with valuable insights into the physiological state of cells within a population, aiding in studying cellular processes such as apoptosis, necrosis, and cell viability. In the present study, after being exposed to LPS and drugs, RAW 264.7 cells were labelled by AO/EtBr stains. A fluorescence microscopic study of AO/EtBr-labelled cells was performed to confirm the apoptosis produced by fucoidan. It was found that most of the cells in the control group were alive, and there were few to no apoptotic cells, as displayed in Fig. 3.

Fig.3.

AO/ EtBr fluorescence staining was used to detect apoptosis, which is characterized by minimal to no apoptosis in control cells, increased necrotic dead cells in LPS-treated cells, and increased live and apoptotic cells in fucoidan-treated cells

It was also witnessed that the staining technique effectively revealed morphological alterations associated with apoptosis in treated cells. In the LPS-treated group, a large number of dead cells were observed where, the orange cells stained with EtBr indicated they are necrotic and late apoptotic cells. Late apoptotic cells in contrast displayed contracted and frequently shattered nuclei compared to necrotic cells. Necrotic cells stain orange and lack condensed chromatin in LPS-treated cells. It was observed that both late and early apoptotic cells were detected in fucoidan-treated cells, i.e. 30–35 µg/ml and the proportion of apoptotic cells increased in a dose-dependent manner in fucoidan-treated cells, as displayed in Fig. 3. Therefore, the conclusion drawn from the results of AO/EtBr staining indicated that the method of cell death in RAW 264.7 cells treated with fucoidan (30–35 µg/ml) is apoptosis, which is characterized by stained cells owing to chromatin condensation and lack of membrane integrity.

Computational analysis results

Using experimental research, we discovered that fucoidan could effectively prevent oxidative damage by decreasing the generation of ROS in activated macrophages and triggering cell death, proving its anti-inflammatory properties. Therefore, we decided to perform molecular docking and molecular dynamics simulation experiments to investigate the pathway associated with the anti-inflammatory effects of our drug. We were interested in understanding if anti-inflammatory actions was because of TNF-α receptor interactions or receptor activation, as in the case of NF-κB. The PDB IDs 1SVC and AZ5 were selected as target proteins for molecular docking and complex simulation studies based on literature studies and a few unique criteria, such as a higher resolution of 2.10 Å in 2AZ5. Secondly, it was the recently identified structure of TNF-α in comparison to others. The reason for selecting 1SVC for complex binding and molecular docking simulation comes from literature and due to their unique crystal structure as it indicates that the structure of a large fragment of the p50 subunit of the human transcription factor NF-kappa B, bound as a homodimer to DNA, reveals that the Rel-homology region has two beta-barrel domains that grip DNA in the major groove. Both domains contact the DNA backbone. The amino-terminal specificity domain contains a recognition loop interacting with DNA bases; the carboxy-terminal dimerization domain bears I-kappa B interaction site. The folds of these domains are related to immunoglobulin-like modules. The amino-terminal domain also resembles the core domain of p53. Since fucoidan is a water-soluble polysaccharide mainly composed of l-fucose and sulphate groups with minimal amounts of mannose, glucose, xylose, and glucuronic acid (Wu et al. 2016), the structure of fucoidan retrieved from PubChem comprising repeating units of fucose sulphate was used in the study. Fucoidans as mentioned are fucose-containing sulphated polysaccharides, meaning that L-fucose always surpasses other sugar monomers, including galactose, mannose, glucose, and uronic acids. l-fucose may account for more than 90% of the overall sugar content of fucoidan (Kopplin et al. 2018).

Molecular docking results

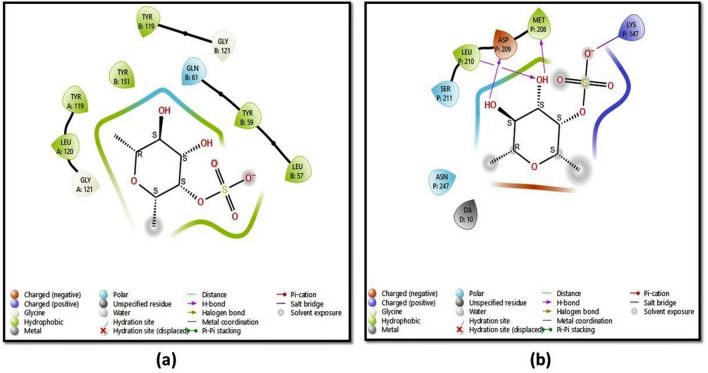

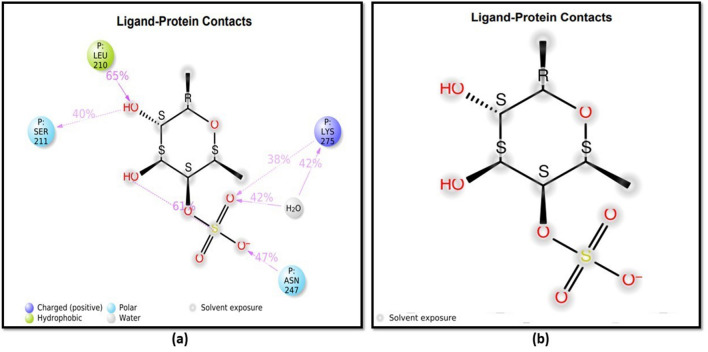

The study aimed to identify the binding affinity of fucoidan to the target protein TNF-α and NF-κB using molecular docking techniques. The target protein NF-κB had a sequence length of 365 residues and a resolution of 2.60 Å, while the TNF-α target had a sequence length of 148 residues and a resolution of 2.10 Å. Hydrogen atoms were added to each inhibitor, followed by energy minimization. The molecular docking technique produced docking scores of ligands along with the resulting glide energy generated. The outcomes of molecular docking studies indicated that the compound fucoidan showed significant binding affinity scores/docking scores for the target proteins. The docking results of fucoidan with target proteins were predicted depending on several parameters, including glide score, hydrogen bond interactions, glide energy, binding free energy and hydrophobic interactions. It was found that fucoidan has properly docked inside the binding sites of both proteins, as shown in the form of 2D interactions in Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

Two-dimensional (2D) depictions of a TNF-α and b NF-κB ligand–protein interactions, with hydrophobic contacts in green, polar interactions in blue, and hydrogen bond formation shown by a purple arrow

Molecular docking and molecular dynamics simulations are extremely important in computer-aided drug design. The docking score obtained by fucoidan binding to TNF-alpha was − 6.36 kcal/mol, whereas NF-κB yielded a value of − 3.814 kcal/mol. The glide energy obtained for TNF-alpha was − 26.79 and − 16.34 kcal/mol, respectively. The docking score represents the energy or stability of the ligand–receptor complex in a particular binding configuration. It considers several things, such as van der Waals interactions, electrostatic interactions, hydrophobic interactions, and hydrogen bonds between the ligand and the receptor. The two-dimensional (2D) representations of ligand–protein interaction are displayed in Fig. 4. In the active regions of proteins, polar residues are indicated in blue, hydrophobic residues in green, and positively charged residues in dark blue. Hydrogen bonds play a part in the interactions between ligands (such as medications) and their target receptors in drug design. These interactions can determine the binding affinity and specificity of the interaction. Figure 4 depicts the formation of hydrogen bonds with the protein NF-κB at LEU 210, MET 208, and ASP 209 residues. The O atom in fucoidan’s hydroxyl group forms H-bonds with the amino acids LEU 210, MET 208, and ASP 209. TNF-α hydrophobic contacts were found at TYR 151, LEU 120, TYR 119, LEU 57, and TYR 59. Hydrophobic interactions were detected in NF-κB at LEU 210 and MET 208. Fucoidan has been acknowledged to possess anticancer, antioxidant, anticoagulant, anti-hyperlipidemic, and antiviral possessions. The constant interaction between fucoidan and target proteins has convincingly revealed fucoidan’s anti-inflammatory effect via TNF-α, as it had a better binding score and glide energy than NF-κB.

Molecular dynamics simulation results

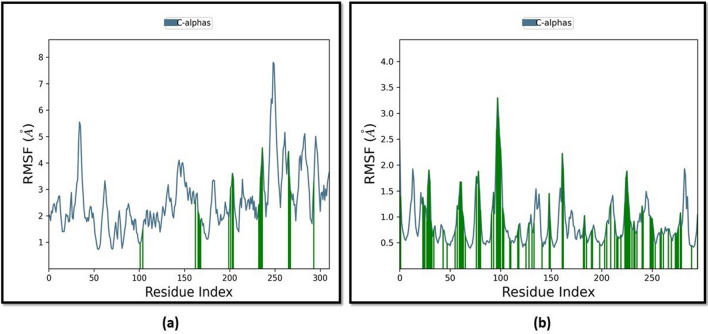

Further, molecular dynamics (MD) simulation studies were conducted to substantiate the results of docking analysis and to assess the stability of the complexes produced after docking. Desmond software was used to perform MD simulations on target proteins and the fucoidan complex to assess structural consistency. MD simulations were run for 100 ns for the target proteins and fucoidan. Several metrics were examined along the simulation trajectory, including the root mean square deviations (RMSD), hydrogen bonds, root mean square fluctuations (RMSF), and protein secondary structure components. RMSD graphs for the ligand that fit on the protein were examined during simulations. Figure 5 displays the RMSD plot for (a) NF-κB and (b) TNF-α.

Fig. 5.

The RMSD plot obtained for a fucoidan-NF-κB complex (PDB ID 1SVC) and b fucoidan-TNF-α complex (PDB ID 2AZ5). The simulation duration of 100 ns demonstrates establishing a stable complex with no significant conformational changes in protein structure

The findings demonstrate that the RMSD for protein in the case of TNF-α deviated at 0.3–2.7 Å, with a few strong peaks up to 2.4–2.7 Å between 0 and 20 ns of simulated time. Still, the ligand RMSD on the right side indicated deviations up to 80 Å, further reduced to 60 Å during the last 20 ns of simulation. Similarly, in the case of NF-κB, the RMSD for protein varied around 6–8.5 Å, with a few significant peaks up to 8.5 Å in the range of 0–65 ns of simulated time, and the ligand RMSD on the right side of plot displayed deviations in the range of 10–14 Å which further reduced to 10.5 Å in later stages of simulations. As the simulation converges, as the RMSD values settle around a given value, changes considerably bigger than 3 Å suggest that the protein is undergoing a substantial conformational shift. The plot displayed above, designated "Lig fit Prot," reveals the RMSD of a ligand after computing the RMSD of the ligand’s heavy atoms and aligning the protein–ligand complex on the backbone of the reference protein. If the ligand RMSD values are substantially beyond the protein’s RMSD, as in the case of TNF-α, the ligand has probably moved from its initial binding site. Thus, it can be stated that these anti-inflammatory reactions proceeded through the NF-κB pathway and not TNF-α as the RMSD plot is found more stable in the case of NF-κB. In order to identify local alterations throughout the protein chain and describe the dynamic behaviour of protein residue, the RMSF fluctuations were also observed for both the target proteins. Figure 6a shows that the NF-κB protein’s residue level fluctuations were extremely high, reaching up to 5–8 Å for residues between 0 and 50 residue numbers. A second, more significant peak (7.5 Å) was visible at around 250 residue index. On the other hand, Fig. 6b shows that the TNF-α protein’s residue level fluctuations were high, reaching 3.5 Å for the protein’s first 100 residues, with a second more significant peak appearing after 150 residues.

Fig. 6.

RMSF analysis for both the target proteins. The RMSF plot obtained for a NF-κB (PDB ID 1SVC) and b TNF-α (PDB ID 2AZ5)

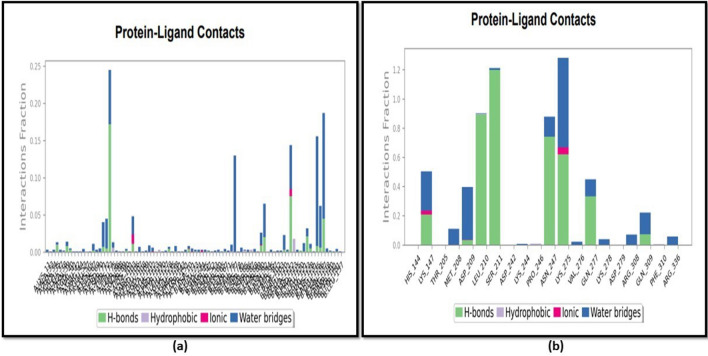

The protein–ligand interactions were also monitored and categorized as H-bonds, ionic bonds, hydrophobic bonds, and water bridges. The H-bonds in the NF-κB were visible at LYS147, LEU 210, ASP 209, SER 211, ASN 247, GLN 277, LYS 275, and GLN 309, as shown in Fig. 7b. Ionic bonds, however, were seen at LYS 147 and LYS 275. Water bridges were also found at LYS 147, MET 208, ASP 209, ASN 247, LYS 275, GLN 277, VAL 276, LYS 278, ARG 308, GLN 309, and ARG 336. Similarly, in the case of TNF-α, hydrogen bonds were observed at LEU 120, TYR 150, GLY 121, VAL 123, LYS 112, HIS 73, LYS 128, SER 71, THR 72, GLU 110, ARG 103, LYS 90, GLN 67, ALA 35, ASN 39, GLY 40, GLU 135, ASN 137, ILE 136, ASN 92, GLU 135, ASP 10 (Fig. 7a), whereas hydrophobic interactions at TYR 119, LEU 57, LEU 94, PRO 113, VAL 85, LEU 75, TYR 87, ALA 35, ALA 38 and ionic interactions at LYS 112, ARG 103, ARG 44, LYS 90, LYS 11, and ASP 10, respectively. Water bridges were also observed at various positions. TYR 151, SER 60, GLY 121, VAL 123, ILE 97, LYS 112, GLU 107, GLN 102, ALA 109, GLN 67, GLU 110, GLN 86 GLN 88, LYS 128, GLU 53, ARG 103, THR 72, SER 71, HIS 73, VAL 41, ASN 39, CYS 69, etc.

Fig. 7.

Analysis of molecular interaction and type of contacts with fucoidan after MD simulation with a TNF-α and b NF-κB where a normalized stacked bar chart of TNF-α protein binding site residues interacting with fucoidan and b normalized stacked bar chart of NF-κB protein binding site residues interacting with fucoidan via hydrogen bond, hydrophobic and ionic interactions, and water bridges

Additionally, Fig. 8 shows a timeline picture of the connections and interactions for both the target proteins indicating a sequence of contacts and interactions. The topmost pane illustrates the entire interactions the protein encounters with the ligand during the trajectory. The lowermost pane represents residues interacting with the ligand inside every trajectory frame. According to the scale on the right of the picture, many residues have unique interactions with the ligands, reflected in a deeper orange colour. As a result, we may infer that more contacts have been created in NF-κB, which is indicated by the increased number of deeper orange hues at specific residue sites during a specified period.

Fig. 8.

Timeline illustration of the interactions between ligands and target proteins a TNF-α and b NF-κB illustrating the total number of contacts throughout the simulation and specific residue location at which interaction occurs

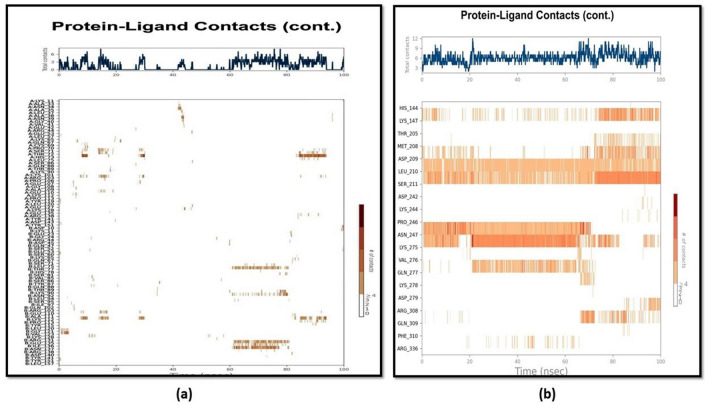

Further, Fig. 9 clearly shows the schematic depiction of ligand atoms and target protein residues. The interactions in the chosen trajectory that occur for over 30.0% of the simulation period up to 100 ns are illustrated in this picture. This figure shows that in NF-κB, the ligand binds to many protein amino acid residues, including LYS 275, ASN 247, SER 211, and LEU 210. ASN 247 and SER 211 displayed polar interactions for 40–47% of the simulation period, while LEU 210 displayed hydrophobic interactions for 65% of the simulation period. In contrast, for TNF-α, no interactions other than solvent exposure were discovered for more than 30% of the simulation duration, thus confirming that the anti-inflammatory actions are due to the NF-κB pathway.

Fig. 9.

Interactions that occur for over 30% of the simulation period are displayed. Detailed schematic interaction of fucoidan with binding site residue of protein crystal structures a NF-κB (1SVC) and b TNF-α (2AZ5), respectively

Finally, for each target protein, the ligand torsions graph indicates the structural progression of every rotating bond inside the ligand during the simulation time. Figure 10 depicts a two-dimensional representation of a ligand with several rotatable bonds in various colour codes. A bar plot and a dial plot of identical colour represent the torsion of rotatable bonds. Dial plots were utilized during the simulation to investigate the torsion’s conformation. The simulation starts in the middle of the radial graph and progresses radially outside. The data from the dial plots were portrayed in bar graphs by exhibiting the torsion probability density. The graphic highlights the potential of the rotating bond in addition to the potential for associated torsions if torsional potential data are acquired. Torsion potential values are provided in kcal/mol. The histogram and torsional potential correlations demonstrate the structural straining that the ligand undertakes to retain a protein-bound conformation.

Fig. 10.

Ligand torsion plot for fucoidan and target protein a NF-κB complex and b TNF-α complex throughout the simulation trajectory

The ligand torsion plot for NF-κB and TNF-α showed four rotational bonds in each case, as shown in Fig. 10. The four color-coded dial plots in both instances began in the centre at the beginning of the simulation and migrated radially outwards as the simulation went on. In the case of NF-κB and TNF-α, the probability density of torsion increased up to 3.02 kcal/mol for the first rotatable bond between sulphur and oxygen in blue, 10.93 kcal/mol for the second rotatable bond between carbon and oxygen in green, 2.27 kcal/mol for another rotatable bond between carbon and hydroxyl group in pink, and 3.01 kcal/mol for a third bond between carbon and hydroxyl group in orange. Every rotatable bond in the ligand has an evolution in conformation at different angles throughout the simulation trajectory, summarized by the ligand torsions diagram. Thus, it can be stated that the ligand had suffered almost the same strain or torsion in the case of both the protein targets as indicated above. To better understand the factors influencing protein stability during the simulation trajectory, secondary structural components were examined to show proteins’ alpha helices and beta strands. According to the results, NF-κB preserved around 37.94% of its secondary structure elements (SSE), mostly 9.58% helices, and 28.36% beta strands. This SSE finding confirms that the protein in fucoidan is exceptionally stable. On the other hand, in the case of TNF-α, 43.07% SSE was maintained out of only 0.03% helix and 43.01% beta strands. Consequently, it may be concluded from the computational study that the anti-inflammatory impacts of fucoidan were caused through the NF-κB pathway and not TNF-α as the simulation results indicated more stability in the case of NF-κB. However, more experimental investigation could provide more details concerning how this happens. In a study, fucoidan produced from Undaria pinnatifida reduced inflammation induced by LPS in RAW 264.7 macrophage cells by preventing the phosphorylation of MAPK (ERK, p38, and JNK) (Phull and Kim 2017). In the ischemia–reperfusion-induced myocardial injury model, Li et al. discovered that the injection of fucoidan extracted from Laminaria japonica could control the inflammatory response via HMGB1 and NF-κB inactivation (Li et al. 2011). Additionally, via altering the gut microbiota, fucoidan from the sea cucumber Pearsonothuria graeffei exhibits substantial benefits in lowering obesity and improving lipid profiles (Li et al. 2018). According to recent research, a fucoidan (LJSF4) isolated from S. japonica has a potent anti-inflammatory activity both in-vitro and in-vivo by downregulating signal pathways such as MAPK and NF-κB (Ni et al. 2020). The molecular mechanism by which fucoidan from D. bartayresiana controls the inflammatory process is still unclear, despite the theory that every newly discovered fucoidan may be a novel chemical with distinct structural features and intriguing bioactive activities.

Discussion

Inflammation is the immune system’s initial response to potentially damaging stimuli (such as damage, stress, and infections). Activating macrophages and neutrophils results in mediators for instance nitric oxide (NO), prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), and pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines. Biomarkers of inflammation include the pro-inflammatory cytokines interleukin-1 (IL-1), tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) besides interleukin-6 (IL-6) although it occurs as a natural defence mechanism, it has been linked to the aetiology of certain disorders. Fucoidans are complex polysaccharides found in brown seaweeds and some marine invertebrates that consist of L-fucose and sulphate ester groups with trace quantities of neutral monosaccharides and uronic acids. Fucoidans from algae have been the subject of much research in recent years due to their wide range of biological functions and potential medicinal applications. Previous research has found that the sulphate concentration of fucoidans from various brown seaweeds influences their bioactivities, particularly their antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties (Wang et al. 2019; Jayawardena et al. 2019). Numerous research have examined the use of brown seaweed fucoidan in food or functional food items and for medicinal or pharmaceutical purposes (Fitton et al. 2019; Citkowska et al. 2019; Chen et al. 2021). Therefore, in the current study, we investigated the anti-inflammatory activity of fucoidan isolated from D. bartayresiana. Here, the anti-inflammatory actions of fucoidan was evaluated using both experimental and computational approaches. The sulphated polysaccharide was extracted and purified from brown seaweed D. bartayresiana using Sephadex A-50 column in our previous study, where the amount of carbohydrate and sulphate estimated in purified sulphated polysaccharide fraction F1 was 1526.48 µg/ml, while the sulphate content obtained was 70.4 mg/ml. The purified sulphated polysaccharide was characterized by NMR and FTIR analyses, thus confirming it as fucoidan (Dubey and Sivaraman 2022). These findings showed that fucose was substantially concentrated throughout the purification process, possibly related to its anti-inflammatory action. Purified fucoidan exhibited FTIR spectrum patterns identical to commercial fucoidan, according to FTIR spectroscopy (Priyan et al. 2020; Wang et al. 2020). Furthermore, 13C NMR findings confirmed that it shares certain structural characteristics with commercial fucoidan. Since the sulphated polysaccharide extracted was fucoidan, it was used for both experimental and computational analyses. So, the anti-inflammatory assets of the fucoidan were checked experimentally using the in-vitro approach in RAW 264.7 cells. The cytotoxic action of fucoidan was investigated using the MTT assay that measures cell viability. It was found that the cells could reduce the LPS-induced inflammation at around 30–35 µg/ml as the cell viability increased to 90–95%. The next step was to measure ROS generation by flow cytometry in LPS-induced RAW 264.7 cells to examine fucoidan’s inhibitory impact on oxidative damage. The ROS production was increased to 84% in LPS-treated cells, which decreased up to 66.8% in the case of positive control (Indomethacin) and comparatively reduced to 65.8% in fucoidan-treated cells. After exposure to LPS and drugs, RAW 264.7 cells were labelled by AO/EtBr stains. A fluorescence microscopy study of AO/EtBr labelled cells was performed to confirm the apoptosis produced by fucoidan. The staining technique effectively revealed morphological alterations associated with apoptosis in fucoidan-treated cells and all the above analyses confirmed the anti-inflammatory potential of fucoidan. In addition, molecular docking and molecular dynamics simulation experiments were carried out to discover the mechanism linked with these anti-inflammatory effects, as numerous studies suggested that LPS binding to the surface of macrophages triggers various intricate intracellular signalling pathways involved in the inflammatory cascade, including the NF-κB signal pathway. Because the activation of NF-κB may cause the overexpression of inflammatory genes and further encourage the production of inflammatory mediators and pro-inflammation cytokines (Chang et al. 2016; Liu et al. 2017; Delma et al. 2019). The proteins selected to assess this anti-inflammatory action were NF-κB and TNF-α, which have a significant role in inflammation. Target and protein docking was performed to measure the effectiveness of protein–ligand binding interactions. Our fucoidan bounded very efficiently with the target proteins and had docking scores of − 6.36 kcal/mol and − 3.81 kcal/mol in the case of TNF-α and NF-κB, respectively. Thus, it can be stated that fucoidan had better inhibition actions towards NF-κB than TNF-α. Molecular dynamics simulations estimated the stability of the complex formed from the ligand and protein binding. The simulation was performed for 100 ns for both the complexes but was found to have promising results in the case of NF-κB. The RMSD plot displayed that root mean square deviation for protein varied around 6–8.5 Å, and for the ligand, the deviations were in the range of 10–14 Å, but the RMSD plot of ligand fit protein presented a constant graph. The RMSF plot indicated variabilities in protein at the residue level, and these fluctuations were found high up to 5–8 Å for residues. It was observed that hydrogen bond formation took place in NF-κB. The O atom in fucoidan’s hydroxyl group forms H-bonds with the amino acids LEU 210, MET 208, and ASP 209. In timeline representations of all the linkages and interactions, few residues had multiple interactions with the ligand. The conformational evolution of every rotatable bond was represented as the ligand’s torsion plot where dial plot indicated the conformational changes occurring during the torsion and the bar plots displayed the probability density of the torsion. The secondary structure elements displayed 9.58% alpha helices and 28.36% beta strands, confirming an influential binding between protein fucoidan and NF-κB. Thus, the computational analysis also confirmed that fucoidan exhibited anti-inflammatory actions by blocking the NF-κB signalling pathway. It was found that although LPS stimulation markedly increased the phosphorylation level of NF-κB in the nucleus, treatment with fucoidan would effectively obstruct the translocation of NF-κB into the nucleus. Therefore, fucoidan might successfully inhibit the NF-κB pathway’s activity and validate its anti-inflammatory effects in macrophages.

Conclusions

In this investigation, fucoidan extracted from D. bartayresiana demonstrated substantial anti-inflammatory actions in LPS-induced RAW 264.7 cells. As per our understanding, this marks the first study to describe the anti-inflammatory actions of fucoidan LPS-induced macrophages by inhibiting ROS production and inducing apoptosis in RAW 264.7 cells. The therapeutic stimulation of cell apoptosis at the inflammatory site might be a potent pro-resolution intervention that meets the clinical requirement to prevent the adverse effects of inflammation. Therefore, any drug that encourages apoptosis in inflamed cells may shield the cells from the harm caused by inflammation and fucoidan triggered apoptosis in cells. Further, according to results from computational analyses, the anti-inflammatory action of fucoidan was attributed to the modification of the NF-κB signalling system. Therefore, it was claimed that fucoidan has positive anti-inflammatory effects on macrophages that had been stimulated by LPS, and that it works by inhibiting the NF-KB signalling pathway. Altogether, it can be said that fucoidan has the potential to be developed as an herbal remedy or as a broad-spectrum anti-inflammation drug.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge Vellore Institute of Technology, Vellore, for the support for Research.

Author contributions

AD and JS conceptualized the research, AD did isolation of compound, investigation, data curation, and original draft preparations, TD performed the laboratory experiments and TR conceptualized the laboratory experiments, VD performed the computational experiments, and JS finally reviewed and supervised the entire study.

Data availability

The data analyzed during the present study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest in the publication.

Ethics declarations

The authors have no competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article. There are no human or animal subjects involved in this study, and informed consent is not applicable.

References

- Abdel-Fattah AF, Hussein MMD, Fouad ST. Carbohydrates of the brown seaweed Dictyota dichotoma. Phytochemistry. 1978;17:741–743. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9422(00)94218-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aisha K, Maryam S. Genus Dictyota (Dictyophyceae, Phaeophycota) from the coastal waters of Pakistan. Int J Biol Res. 2019;7(1):1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Apostolova E, Lukova P, Baldzhieva A, et al. Polymers immunomodulatory and anti-inflammatory effects of fucoidan: a review. Polymers (basel) 2020;12:2338. doi: 10.3390/polym12102338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouzidi N, Daghbouche Y, El Hattab M, et al. Determination of total sterols in brown algae by Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy. Anal Chim Acta. 2008;616:185–189. doi: 10.1016/J.ACA.2008.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang KC, Ko YS, Kim HJ, et al. 13-Methylberberine reduces HMGB1 release in LPS-activated RAW264.7 cells and increases the survival of septic mice through AMPK/P38 MAPK activation. Int Immunopharmacol. 2016;40:269–276. doi: 10.1016/J.INTIMP.2016.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen P-H, Chiang P-C, Lo W-C, et al. NC-ND license A novel fucoidan complex-based functional beverage attenuates oral cancer through inducing apoptosis, G2/M cell cycle arrest and retarding cell migration/invasion. J Funct Foods. 2021;85:1756–4646. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2021.104665. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chuang CC, McIntosh MK. Potential mechanisms by which polyphenol-rich grapes prevent obesity-mediated inflammation and metabolic diseases. Annu Rev Nutr. 2011;31:155–176. doi: 10.1146/annurev-nutr-072610-145149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Citkowska A, Szekalska M, Winnicka K. Possibilities of fucoidan utilization in the development of pharmaceutical dosage forms. Mar Drugs. 2019;17:458. doi: 10.3390/MD17080458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa LS, Fidelis GP, Cordeiro SL, et al. Biological activities of sulfated polysaccharides from tropical seaweeds. Biomed Pharmacother. 2010;64:21–28. doi: 10.1016/J.BIOPHA.2009.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delma CR, Thirugnanasambandan S, Srinivasan GP, et al. Fucoidan from marine brown algae attenuates pancreatic cancer progression by regulating p53–NFκB crosstalk. Phytochemistry. 2019;167:112078. doi: 10.1016/J.PHYTOCHEM.2019.112078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- dos Santos Nunes RG, Pereira PS, Elekofehinti OO, et al. Possible involvement of transcriptional activation of nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2)in the protective effect of caffeic acid on paraquat-induced oxidative damage in Drosophila melanogaster. Pestic Biochem Physiol. 2019;157:161–168. doi: 10.1016/j.pestbp.2019.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubey A, Sivaraman J. Evaluation of the cytotoxicity, apoptosis and autophagy induction by fucoidan in human hepatic adenocarcinoma cells. Indian J Pharm Educ Res. 2022;56:756–764. doi: 10.5530/ijper.56.3.125. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fitton JH, Stringer DN, Park Y, Karpiniec SS. Therapies from fucoidan: new developments. Mar Drugs. 2019;17(10):571. doi: 10.3390/md17100571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hariram Nile S, Won Park S. Optimized methods for in vitro and in vivo anti-inflammatory assays and its applications in herbal and synthetic drug analysis. Mini-Rev Med Chem. 2013;13:95–100. doi: 10.2174/1389557511307010095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwalewa EO, Mcgaw LJ, Naidoo V, Eloff JN. Inflammation: the foundation of diseases and disorders. A review of phytomedicines of South African origin used to treat pain and inflammatory conditions. Afr J Biotechnol. 2010;6:2868–2885. doi: 10.4314/ajb.v6i25.58240. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jayawardena TU, Fernando IPS, Lee WW, et al. Isolation and purification of fucoidan fraction in Turbinaria ornata from the Maldives; inflammation inhibitory potential under LPS stimulated conditions in in-vitro and in-vivo models. Int J Biol Macromol. 2019;131:614–623. doi: 10.1016/J.IJBIOMAC.2019.03.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kauppinen A, Suuronen T, Ojala J, et al. Antagonistic crosstalk between NF-κB and SIRT1 in the regulation of inflammation and metabolic disorders. Cell Signal. 2013;25:1939–1948. doi: 10.1016/J.CELLSIG.2013.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiemer AK, Müller C, Vollmar AM. Inhibition of LPS-induced nitric oxide and TNF-α production by α-lipoic acid in rat Kupffer cells and in RAW 264.7 murine macrophages. Immunol Cell Biol. 2002;80:550–557. doi: 10.1046/J.1440-1711.2002.01124.X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JW, Zhou Z, Yun H, et al. Cigarette smoking differentially regulates inflammatory responses in a mouse model of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis depending on exposure time point. Food Chem Toxicol. 2020;135:110930. doi: 10.1016/J.FCT.2019.110930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopplin G, Rokstad AM, Mélida H, et al. Structural characterization of fucoidan from Laminaria hyperborea: assessment of coagulation and inflammatory properties and their structure-function relationship. ACS Appl Bio Mater. 2018;1:1880–1892. doi: 10.1021/ACSABM.8B00436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H-G, Nagahawatta DP, Liyanage NM, et al. Structural characterization and anti-inflammatory activity of fucoidan isolated from Ecklonia maxima stipe. Algae. 2022;37(3):239–247. doi: 10.4490/algae.2022.37.9.12. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li C, Gao Y, Xing Y et al (2011) Fucoidan, a sulfated polysaccharide from brown algae, against myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury in rats via regulating the inflammation response. Food Chem Toxicol 49:2090–2095. 10.1016/J.FCT.2011.05.022 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Li S, Li J, Mao G et al (2018) A fucoidan from sea cucumber Pearsonothuria graeffei with well-repeated structure alleviates gut microbiota dysbiosis and metabolic syndromes in HFD-fed mice. Food Funct 9:5371–5380. 10.1039/C8FO01174E [DOI] [PubMed]

- Li R, Zhou Q-L, Yang R-Y, et al. Determining the potent immunostimulation potential arising from the heteropolysaccharide structure of a novel fucoidan, derived from Sargassum Zhangii. Food Chem. 2023;18:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.fochx.2023.100712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu D, Cao G, Han L, et al. Flavonoids from Radix Tetrastigmae inhibit TLR4/MD-2 mediated JNK and NF-κB pathway with anti-inflammatory properties. Cytokine. 2016;84:29–36. doi: 10.1016/J.CYTO.2015.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q, Xiao XH, Hu LB, et al. Anhuienoside C ameliorates collagen-induced arthritis through inhibition of MAPK and NF-κB signaling pathways. Front Pharmacol. 2017;8:1–12. doi: 10.3389/FPHAR.2017.00299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manggau M, Kasim S, Fitri N, et al. Antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and anticoagulant activities of sulfate polysaccharide isolate from brown alga Sargassum policystum. IOP Conf Ser Earth Environ Sci. 2022;967:1–12. doi: 10.1088/1755-1315/967/1/012029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Martins AP, Yokoya NS, Colepicolo P. Biochemical modulation by carbon and nitrogen addition in cultures of Dictyota menstrualis (Dictyotales, Phaeophyceae) to generate oil-based bioproducts. Mar Biotechnol. 2016;18:314–326. doi: 10.1007/S10126-016-9693-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mauriz JL, Collado PS, Veneroso C, et al. A review of the molecular aspects of melatonin’s anti-inflammatory actions: recent insights and new perspectives. J Pineal Res. 2013;54:1–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079x.2012.01014.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Na YS, Kim WJ, Kim SM, et al. Purification, characterization and immunostimulating activity of water-soluble polysaccharide isolated from Capsosiphon fulvescens. Int Immunopharmacol. 2010;10:364–370. doi: 10.1016/J.INTIMP.2009.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ni L, Wang L, Fu X et al (2020) In vitro and in vivo anti-inflammatory activities of a fucose-rich fucoidan isolated from Saccharina japonica. Int J Biol Macromol 156:717–729. 10.1016/J.IJBIOMAC.2020.04.012 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Obluchinskaya ED, Pozharitskaya ON, Shikov AN. In vitro anti-inflammatory activities of fucoidans from five species of brown seaweeds. Mar Drugs. 2022;20:1–16. doi: 10.3390/md20100606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phull AR, Kim SJ (2017) Fucoidan as bio-functional molecule: Insights into the anti-inflammatory potential and associated molecular mechanisms. J Funct Foods 38:415–426. 10.1016/J.JFF.2017.09.051

- Priyan I, Fernando S, Kapuge K, et al. Fucoidan purified from Sargassum polycystum induces apoptosis through mitochondria-mediated pathway in HL-60 and MCF-7 cells. Mar Drugs. 2020;18(196):1–13. doi: 10.3390/md18040196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabanal M, Ponce NMA, Navarro DA, et al. The system of fucoidans from the brown seaweed Dictyota dichotoma: chemical analysis and antiviral activity. Carbohydr Polym. 2014;101:804–811. doi: 10.1016/J.CARBPOL.2013.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ragan MA, Jensen A. Quantitative studies on brown algal phenols. I. Estimation of absolute polyphenol content of Ascophyllum nodosum (L.) Le Jol. and Fucus vesiculosus (L.) J Exp Mar Bio Ecol. 1977;30:209–221. doi: 10.1016/0022-0981(77)90013-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Subbaiya R, Saravanan M, Priya AR, et al. Biomimetic synthesis of silver nanoparticles from Streptomyces atrovirens and their potential anticancer activity against human breast cancer cells; Biomimetic synthesis of silver nanoparticles from Streptomyces atrovirens and their potential anticancer activity against human breast cancer cells. IET Nanobiotechnol. 2017;11(8):965–972. doi: 10.1049/iet-nbt.2016.0222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y, Liu J, Jiang X, et al. One-step synthesis of chiral oxindole-type analogues with potent anti-inflammatory and analgesic activities. Sci Rep. 2015;5:1–7. doi: 10.1038/srep13699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor RB, Lindquist N, Kubanek J, Hay ME. Intraspecific variation in palatability and defensive chemistry of brown seaweeds: effects on herbivore fitness. Oecologia. 2003;136:412–423. doi: 10.1007/S00442-003-1280-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toker G, Küpeli E, Memisoǧlu M, Yesilada E. Flavonoids with antinociceptive and anti-inflammatory activities from the leaves of Tilia argentea (silver linden) J Ethnopharmacol. 2004;95:393–397. doi: 10.1016/J.JEP.2004.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Chen P, Tang C, et al. Antinociceptive and anti-inflammatory activities of extract and two isolated flavonoids of Carthamus tinctorius L. J Ethnopharmacol. 2014;151:944–950. doi: 10.1016/J.JEP.2013.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Xu Y, Zhang P, et al. Smiglaside A ameliorates LPS-induced acute lung injury by modulating macrophage polarization via AMPK-PPARγ pathway. Biochem Pharmacol. 2018;156:385–395. doi: 10.1016/J.BCP.2018.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Oh JY, Hwang J, et al. In vitro and in vivo antioxidant activities of polysaccharides isolated from celluclast-assisted extract of an edible brown seaweed, Sargassum fulvellum. Antioxidants. 2019;8(493):1–12. doi: 10.3390/antiox8100493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Guan Y, Yang R, et al. Anti-inflammatory activity of 3-cinnamoyltribuloside and its metabolomic analysis in LPS-activated RAW 264.7 cells. BMC Complement Med Ther. 2020;20(329):1–12. doi: 10.1186/S12906-020-03115-Y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu L, Sun J, Su X, et al. A review about the development of fucoidan in antitumor activity: progress and challenges. Carbohydr Polym. 2016;154:96–111. doi: 10.1016/J.CARBPOL.2016.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J, Liu Z, Su J, et al. Anti-inflammatory activity of 3β-hydroxycholest-5-en-7-one isolated from Hippocampus trimaculatus leach via inhibiting iNOS, TNF-α, and 1L–1β of LPS induced RAW 264.7 macrophage cells. Food Funct. 2017;8:788–795. doi: 10.1039/C6FO01154C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y, Chen F. Antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and anti-apoptotic activities of nesfatin-1: a review. J Inflamm Res. 2020;13:607–617. doi: 10.2147/JIR.S273446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye J, Chen D, Ye Z, et al. Fucoidan isolated from Saccharina japonica inhibits LPS-induced inflammation in macrophages via blocking NF-κB, MAPK and JAK-STAT pathways. Mar Drugs. 2020;18:1–17. doi: 10.3390/md18060328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Tsao R. Dietary polyphenols, oxidative stress and antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects. Curr Opin Food Sci. 2016;8:33–42. doi: 10.1016/J.COFS.2016.02.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang A, Sun H, Wang X. Recent advances in natural products from plants for treatment of liver diseases. Eur J Med Chem. 2013;63:570–577. doi: 10.1016/J.EJMECH.2012.12.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang TT, Wang M, Yang L, et al. Flavonoid glycosides from Rubus chingii Hu fruits display anti-inflammatory activity through suppressing MAPKs activation in macrophages. J Funct Foods. 2015;18:235–243. doi: 10.1016/J.JFF.2015.07.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou ZL, Yang YX, Ding J, et al. Triptolide: structural modifications, structure–activity relationships, bioactivities, clinical development and mechanisms. Nat Prod Rep. 2012;29:457–475. doi: 10.1039/C2NP00088A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data analyzed during the present study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.