Abstract

Fiscal decentralization, widely believed to be one essential tool to boost economic growth, is typically presented as something that works for developed countries. However, this needs to be investigated, which is what this paper aims to do. This paper investigates the relationship between fiscal decentralization and economic growth, specifically focusing on its applicability in both developed and developing countries. Using cross-sectional data from 23 African and 23 OECD countries, we employ two-stage estimation methods, including two-stage least squares (2SLS), Generalized Method of Moments (GMM), and Limited Information Maximum Likelihood (LIML), to address concerns related to endogeneity. The inclusion of instruments representing country size, ethnoreligious diversity, and administrative structure enhances the analysis. The dependent variable is based on average values for the five-year period between 2015 and 2019, while the explanatory variables are derived from data in 2017, representing the midpoint of the 2013–2021 period. The results highlight the effectiveness of the 2SLS method in estimating the relationship between fiscal decentralization, control variables, instrument variables, and per capita GDP. Empirical findings indicate significant positive impacts of both expenditure decentralization and revenue decentralization on per capita GDP, holding true for both developed and developing countries, with a slightly stronger effect observed in the latter. These results underscore the potential benefits of fiscal decentralization across diverse economies and offer valuable insights for policymakers.

The study uses cross-sectional data from 23 African and 23 OECD countries and applies two-stage estimation methods to effectively address the endogeneity issue in the modeling. A variety of such methods in two-stage least squares (2SLS), Generalized Method of Moments (GMM), and Limited Information Maximum Likelihood (LIML) are applied and compared against the ordinary least squares (OLS) method. Variables that represent the size, the ethnoreligious diversity and the type of administrative structure of the countries are employed as instruments. The 2SLS method proved to excellently estimate the relationship between the fiscal decentralization terms as well as other control and instrument variables and the per capita GDP. The findings from the empirical analysis showed that both expenditure decentralization and revenue decentralization have significant positive impacts on per capita GDP of a country. This relationship holds not only for developed countries but also for developing ones, even to a slightly better degree in the latter.

Keywords: Fiscal decentralization, Expenditure, Revenue, 2SLS, Endogeneity, Africa

1. Introduction

Fiscal decentralization is conceived to achieve economic growth by distributing revenue collection and expenditure management to subnational governments. However, there is a deep-rooted debate on whether the system can apply to all countries or only to countries at a certain level of economic growth. The facts are the current status of fiscal decentralization in developing countries is significantly lower than that of developed ones. The argument in most cases lies in whether the economic status or the level of fiscal decentralization is seen as a cause or a result of the other – are the less developed countries not suited for this system, or are they less developed because they did not practice the system to a good level. Should the countries wait until they reach a certain level of development to entertain fiscal decentralization? How different is the level of fiscal decentralization in developing countries? What is the impact of fiscal decentralization on the economy of a county? Is the level of impact and significance different in developing countries? This paper addresses these questions by investigating the fiscal decentralization practice and related economic data of selected developing African countries with the OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) countries.

It is commonly reflected in the literature on fiscal decentralization that developed countries are more decentralized than developing ones [8,31,45]. One of the studies described the “weakness of the local governments” as the distinctive feature of developing countries [5]. Based on a survey of 43 nations consisting of both developed and developing countries, Oates declared that 65% of the total expenditure is utilized centrally in developed countries, while the figure reaches 89% in developing countries [32]. Revenue decentralization is reported to follow a similar trend [32]. Despite the common agreement on the difference in the level of fiscal decentralization, there is significant variation in interpreting the fact. Some would prefer to see fiscal centralization as a cause for the sluggish economic growth, while others believe it is a result that naturally happens during the early development stages.

Wallas E. Oates has two famous publications, published in 1972 and 1985, in which he argued the critical role of fiscal decentralization in economic development [31,32]. This argument is shared by Ref. [43]. On the other side, there are [44] and others who do not suggest fiscal decentralization until a country gets relatively wealthy because they think it is “expensive”. Reference [5] argues that countries at early stages of development are better served with a centralized fiscal system. The argument is supported by empirical analysis by Ref. [14], who deemed the relationship between fiscal decentralization and growth to be non-existing in developed countries and negative in developing countries.

Theoretical perspectives suggest that fiscal decentralization can enhance economic growth through various mechanisms. From an economic theory perspective, it improves resource allocation and responsiveness to local economic conditions [33] Public choice theory highlights how it empowers local governments and promotes fiscal discipline through competition [19]. A political economy perspective emphasizes its role in enhancing stability and reducing fiscal imbalances [37]. The effectiveness of fiscal decentralization is influenced by the institutional framework, including legal and administrative structures [16]. This study examines the relationship between fiscal decentralization and economic growth in developed and developing countries, drawing on these theoretical perspectives to guide the analysis and contribute to the existing literature.

Reference [14] is one of the earliest studies that addressed the relationship between fiscal decentralization and GDP. Ordinary least squares (OLS) method is used on a cross-country panel data set collected from 46 developed and developing countries from 1970 to 1989. The independent variables included in the model, in addition to the expenditure decentralization, are tax rate, population growth, initial human capital, initial per capita GDP, investment share of GDP and a dummy variable for time fixed effects. The study concluded a negative relationship between fiscal decentralization and economic growth for five- and ten-year intervals in the world and developing country samples. One major issue that makes the conclusion questionable is the endogeneity of the expenditure decentralization term, which would lead to the nonfulfillment of Gauss-Markov assumption of an OLS and a possible bias in the regression result. The expenditure decentralization being the only measure used cannot fully represent fiscal decentralization, especially on the revenue side.

The study by Ref. [4] investigates the moderation effect of institutional quality (IQ) on the relationship between financial inclusion (FI) and financial development (FD) in Organization of Islamic Cooperation (OIC) countries. Their findings highlight a significant positive relationship between FI, IQ, and FD, emphasizing the crucial role of financial inclusion and institutional quality in sustainable development. The findings are consistent with that of reference [3] which focused on Islamic Development Bank member countries.

A contradicting result is reported by Ref. [25]. The study evaluated the impact of fiscal decentralization on GDP growth based on cross-country data from 51 countries in four categories for the period 1997 to 2001. Variables such as average tax rate, political freedom, population, initial human capital, initial GDP and two dummy variables for income groups and regions are used in the study that employed Instrumental Variables (IV) technique with an interaction term. The study concluded a positive relationship between fiscal decentralization and economic growth. However, this study also considered the decentralization in expenditure as the only measure of fiscal decentralization [14]. The inclusion of the interaction term between fiscal decentralization and political freedom also complicates the interpretation of the regression coefficients, as is witnessed with the contestation in the paper itself with the negative coefficient of the interaction term. Though such a method is commonly used in psychology studies, it is not popular in econometric studies. The strong collinearity among a variable and the interaction term that includes the same variable is something that needs further investigation.

Reference [28] suggested the use of variables such as legal system origin and type of demonstrative system of the country together with the size of the country as instruments in a two-stage least square regression. Data from 56 countries over the period 1990–2007 was used in the study. They reported that the results vary based on the alternative instrumental variables used. The selected IVs are also said to be insufficient to guarantee causality between fiscal decentralization and economic growth.

Panel data from 27 advanced and emerging economies in Europe for the period 1992 to 2017 was used in Ref. [36]. The study devised an overall decentralization indicator that can represent revenue and expenditure decentralization, defined as the geometric mean of two indicators. Individual models consisted of the individual variables were developed. The OLS regression results showed that only the expenditure decentralization term exhibited a statistically significant positive coefficient. In contrast, both the revenue decentralization and the composite term have got statically significant but negative coefficients. It is worth mentioning again that the possible endogeneity is not addressed in the study.

A continuation of the literature on the topic is one by Ref. [21] used two-step system Generalized Method of Moments (GMM) based technique on a panel data of 15 developing federations for the period 2000 to 2015. Tax revenue decentralization and expenditure decentralization are used to measure the fiscal decentralization. Factors such as social capital, labor force, inflation, trade openness, rate of investment, corruption, institutional quality, quality of Democracy, size of the public sector are considered through respective independent variables. The study focused only on federal nations and concluded that both tax revenue decentralization and expenditure decentralization contribute to economic growth in the countries. Though the paper did not explicitly point out the instrument variables, it is explained that lagged variables of the level equation are used as instruments and the number of instrumental variables (IVs) are reported as 14 and 12. Using more than one lagged versions of a single variable as instruments would be a questionable approach, given the fact that it makes it very unlikely for the IVs to be exogenous.

An effort to address the endogeneity issue, which they alleged has plagued the vast majority of the empirical literature on fiscal decentralization and growth, is applied by Ref. [12]. The approach involves the use of two instrument variables, the size of the country and geographic fragmentation index (GFI), which they argue are strong and consistent instruments for fiscal decentralization. It is concluded that decentralizing expenditure or revenue at subnational levels results in growth in GDP per capita. A new instrument variable called GFI, which was developed by their earlier study [11], is used. A special observation during our review of literatures and data collection is the case of Comoros. Though Comoros is one of the smallest countries, its special characteristics related to the geographic dispersion of the member islands as well as their history of existing as independent nations are said to be important factors for the suitability of fiscal decentralization in Comoros [26]. However, it is understandably challenging to devise a variable that can represent such geographic and historic characteristics. Thus, the GFI variable used in Ref. [12] is an interesting attempt. Taking factors other than altitude in to consideration in the fragmentation metric would have produced a better instrument specially in terms of improving the correlation with fiscal decentralization (endogenous) variable.

Reference [24] used panel data of 18 countries over the 2011–2017 period to examine the simultaneous relationship that exists between fiscal decentralization, and human development and economic growth. The methods employed in the study are 3SLS (Three Stage Least Squares) and GMM (Generalized Method of Moments). The reported results showed that fiscal decentralization has a negative impact on economic growth and vice versa. While the sophistication in the method could be useful to address some of the modeling issues, the specific choice of a 3SLS method is dubitable in this case especially due to likelihood of the equations being under-identified and thus be disregarded in such an estimation.

Reference [15] investigated the relationship between government size, decentralization, and economic growth in Italian regions. Their findings revealed an inverted U-shaped relationship between public expenditure and economic growth, depending on the degree of fiscal decentralization. The optimal degree of decentralization was estimated to be around 32%, with an optimal government size value of approximately 52%. The study contributes to the literature by using regional data within the same country, providing a consistent measure of government size across statistical units.

Reference [29] examined the relationship between public finance variables and economic growth in West African countries, focusing on the West African Economic and Monetary Union (WAEMU). The study employed panel econometric techniques and found that government expenditure and revenue had counter-cyclical nature in WAEMU, West African Monetary Zone (WAMZ), and Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) countries. The study also revealed weak long-run relationships between government budget and terms of trade, as well as Granger causality effects suggesting a unidirectional causality from government revenue to expenditure. The findings highlighted the interrelatedness of WAEMU countries and emphasized the need for greater intra-African trade and regional integration to enhance the benefits of monetary union.

Reference [10] assessed the sustainability of fiscal policy in the European Union (EU) countries from 1980 to 2015. The study employed panel unit root tests, cointegration analysis, and causality tests to examine the relationship between government revenues, expenditures, primary balance, and debt. The results indicated the presence of a long-run relationship between government revenues and expenditures, as well as between government primary deficit and debt. The causality tests supported the fiscal neutrality hypothesis, showing no causal link between government revenues and expenditures. The study identified three homogeneous clusters of countries, with one group, including Portugal, Ireland, Italy, Greece, and Spain, exhibiting unsustainable fiscal trends.

One major problem observed in most empirical studies is the identification problem related to the above-mentioned cause or effect relationship between fiscal decentralization and economic growth. Economic growth is believed to be impacted by fiscal decentralization while decentralization can also be influenced by the economic growth [27]. This reverse causality leads to endogeneity problem in the empirical models and thus evoking concerns on the veracity of the conclusions drawn. This issue of endogeneity is also discussed in studies on the impact of decentralization on variables other than GDP as well [12]. The endogeneity in the models can also be related to some omitted variable biases.

As agreeable as the endogeneity problem is in most studies, the approaches used to address the issue are diverse. One of the methods is multi stage regressions that use IVs. The regressions can be two-stage least squares (2SLS) [28], Generalized Method of Moments (GMM) [17,21], three stage least squares (3SLS) [24]. There are a range of variables applied as instruments in different studies. The approaches can mainly be classified in to two. The first approach is using lagged or initial values of the independent variables as instruments as in Refs. [20,21,25]. Initial GDP, which is GDP of the first year in the panel set, is one of the IVs used in most of such studies. The other type approach involves the use of external instruments. Some of the external instrument variables used in the literature include land area or size of country [28], the geographic fragmentation index [12], country's legal origin [18], federal system [28], fiscal autonomy [9]. Some studies used parameters such as elevation and climate [11], which are difficult to correlate with fiscal decentralization to say the least. It is also common to notice IVs used in other studies which are not exogenous themselves.

This paper aims to examine the relationship between fiscal decentralization and economic growth in 23 developing African countries and 23 OECD countries. While previous studies have explored this relationship to some extent, our research addresses several gaps in the literature. Specifically, we seek to provide updated empirical evidence on the impact of fiscal decentralization on economic growth and investigate the factors that influence this relationship. By including important yet overlooked factors like ethnoreligious diversity, our analysis expands the existing knowledge on this subject.

One of the key motivations behind this study is to bridge the gap in the literature that stems from the scarcity of data on African economies. While the role of fiscal decentralization has been extensively studied in developed countries, its implications for developing African nations remain understudied. Therefore, by comparing African economies with those of OECD countries, we aim to shed light on the suitability of decentralized fiscal systems in different contexts and challenge the prevailing assumption that they are primarily beneficial for developed nations.

The objectives of this research are twofold. First, we aim to analyze the relationship between fiscal decentralization and economic growth by employing expenditure and revenue decentralization as measures of fiscal decentralization. Second, we seek to evaluate the impact of various economic, social, geographic, and political factors on the suitability of fiscal decentralization in both African and OECD countries. By considering a comprehensive set of variables and employing rigorous statistical techniques, we aim to provide a nuanced understanding of the complex relationship between fiscal decentralization and economic growth.

In this paper, an empirical analysis of cross-sectional data of 23 developing African countries and 23 OECD countries is applied to evaluate the role of fiscal decentralization to economic growth. Expenditure decentralization and revenue decentralization are used to measure the fiscal decentralization while the dependent variable in the models is log of per-capita GDP. The role of economic, social, geographic and political factors on suitability of the system are evaluated in the empirical analysis though the use of selected exogenous and instrument variables. Factors such as ethnoreligious diversity, which play important role specially in African countries but yet are not considered in earlier studies, are taken in to consideration. The study contributes in providing updated empirical evidence on the relationship between fiscal decentralization and economic growth as well as the factors that influence this relationship. It gives a different perspective to the thought that decentralized fiscal system only suites the developed. The study is foremost a path-breaker in terms of addressing a region which is less covered in the literature due to scarcity of data.

One of the challenges in the imperial studies relating fiscal decentralization and growth appear to be finding suitable external instruments that are exogenous to each other and whose influence economic growth is though the endogenous variable. This study starts with a large set of candidate variables listed in Table 1 collected from the previous literature on the topic. It was arrived at a refined set of control and instrument variables after a series of tests and logical reasoning. Variables with strong exogeneity credentials and explicable level of correlation with the endogenous variables (the decentralization terms) are selected.

Table 1.

Description of variables.

| Variables | Description | Source |

|---|---|---|

| ED | Expenditure decentralization (%) | OECD-UCLGa |

| EFb | Ethnic Fractionalization | [2] |

| EXP | Government Expenditure % of GDP | The Heritage Foundationc |

| FDI | Foreign direct investment, net inflows (% of GDP) | WB WDI 2017d |

| FEDe | Type of government (1 = federal, 0 = unitary) | SNG-WOFIf |

| GI | Government Integrity | The Heritage Foundation |

| INF | Inflation | WB WDI 2017 |

| JE | Judicial Effectiveness | The Heritage Foundation |

| LogGDPPC | Natural logarithm of GDP per capita | WB WDI 2017 |

| LogLND | Natural logarithm of Land area (millions of sq. km) | WB WDI 2017 |

| LogPOP | Natural logarithm Population (millions) | WB WDI 2017 |

| N_SNG | Total number of SNGs | SNG-WOFI |

| RD | Revenue decentralization (%) | OECD-UCLG |

| RFb | Religious Fractionalization | [2] |

| TR | Average Tax Rateg | The Heritage Foundation |

OECD-UCLG World Observatory on Subnational Government Finance and Investment.

Ref. [30].

World Development Indicators [46].

This variable is a dummy variable, quasi-federal states such as South Africa are considered as federal states.

SNG-WOFI country and territory profiles.

The average of individual income tax and corporate tax rates calculated by authors.

The motivation for conducting this study lies in the need to understand the relationship between fiscal decentralization and economic growth, particularly in both developed and developing countries. Fiscal decentralization is often considered a vital policy tool, but its applicability and effectiveness across different economic contexts remain an open question.

The findings from this study have the potential to contribute significantly to policy discussions and decision-making processes. By employing rigorous empirical methods and considering a diverse sample of African and OECD countries, the study provides valuable insights into the impacts of fiscal decentralization on economic growth. The identification of positive effects of expenditure and revenue decentralization on per capita GDP, across both developed and developing countries, suggests the potential benefits of implementing decentralized fiscal policies.

The rest of this paper includes a brief discussion on the practice of fiscal decentralization in Africa which is followed by a section that presents the data and method used in the study. The types of estimation and the models are described. The regression results are presented and discussed together with the post-estimation diagnosis in the later section. The final part of the paper is where conclusions are forwarded based on the findings from the empirical analysis.

2. Fiscal decentralization in Africa

Africa is working towards achieving two major targets set globally and by the continent itself in the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) and the 2063 African Union's Agenda (Agenda 2063) respectively. Agenda 2063 is a strategic plan for the next 50 years that was adopted by the 24th ordinary assembly of the African Union in Addis Ababa on 31 January 2015. One of the main goals in the economic development pillar of the agenda is eradicating poverty within one generation [1]. The SDGs were adopted by the UN member states in 2015 as a universal call to action to end poverty, protect the world and ensure that all people enjoy prosperity and peace by 2030 [42]. Setting up adequate financial policies and mechanisms is critical to achieving those goals. Fiscal decentralization is one of those mechanisms which is believed to contribute to achieving those two plans.

The early attempts of adopting decentralization in Africa started in the 1990s [40]. The Africities Summit which was held in 1998 in Abidjan, Ivory Coast, is one memorable instance of the continental progress towards embracing decentralization. The summit was held with the theme “Recognition of the essential role of local governments in the development of Africa”. Agendas such as challenges of decentralization, local development, regional integration, and cooperation within Africa were discussed during the summit [41]. Africities has continued to be one of the important platforms where decentralization is discussed and experiences are shared among African countries.

The Yaounde Declaration, which was adopted by the African Ministers in the 10th plenary meeting of the Global Forum on Transparency and Exchange of Information for Tax Purposes (the Global Forum), in 2005 was one of the landmark documents in the decentralization practice in Africa, as a continent. Thirty two African countries and the African Union Commission have signed the declaration as of October 2021 [34]. The declaration promotes decentralization and effective participation of the population at all levels.

Another millstone is the adoption of the “African Charter on Values and Principles of Decentralization, Local Governance, and Local Development”, by the African Union (AU) in 2014 which entered into force on January 13, 2019. The first objective of the charter is to “Promote, protect and act as a catalyst for decentralization, local governance and local development in Africa” [6]. 17 countries have signed, 6 have ratified and 6 have deposited the charter until the end of 2021 [7]. One of the few studies that reviewed the charter by Ref. [13] states that though the effort by AU to put forward the Charter is commendable, the charter has two major drawbacks: inability to sufficiently guarantee local autonomy and failure to explicitly recognize the role of traditional authorities.

Fiscal decentralization has received growing interest across Africa. However, the rate of progress in the different countries has been diverse and it was not a linear path for any of the countries [47]. After independence in the 1960s, the fiscal system in most African countries was a highly centralized one. The regimes that came to power after freedom promised immediate changes in terms of decentralization and autonomy of sub-national governments though the promises could not be seen put into action during the first few decades. It was since the 1990s and early 2000s that visible changes started to be noticed. Those changes were mostly in terms of the legislative and constitutional reforms such as the 1997 Finance Act of Kenya, the 1997 Local Governments Act of Uganda, and the Municipal Finance Management Act (2003) of South Africa to mention a few. Other heavily centralized governments were also undergoing major political changes. Fiscal decentralization was used by most the countries as a means to compromise the internal ethnic and political differences. Some of the North African countries such as Morocco that were late relatively late to incorporate fiscal decentralization have been pushed to follow a similar trend by the Arab Spring. Three countries - Ethiopia, Nigeria, and South Africa – are identified by Ref. [22] as the countries with the most advanced decentralization out of sub-Saharan Africa. The expenditure of the sub-national governments in those countries is reported to be around half of the total general government expenditure.

Most of the regional governments in most African countries are highly dependent on budgetary transfers from their respective central governments except for a very few large urban governments located in relatively richer countries that have the capacity of generating a significant part of their expenditure on their own. The other common characteristic of the fiscal system in African countries is the huge fiscal disparities and the misalignment between responsibilities and the resources of the sub-national governments.

23 developing African countries1 shown in the map in Fig. 1 are considered for the empirical analysis in this study.

Fig. 1.

Sample developing African countries considered in the study (drawn by the authors using [23].

Some of the major summary points on the fiscal decentralization in the selected African countries and the cooperative statistics with the whole dataset consisting of the OECD countries2 are:

The overall level of implementation of fiscal decentralization in Africa is still at an early stage with the mean values of expenditure decentralization and revenue decentralization being 16% and 18% respectively.

The level of decentralization in terms of revenue and expenditure decentralization is almost equal in average. Revenue decentralization is marginally higher with mean value of 18.87% compared to 18.76% of expenditure decentralization. This could allow for the possibility of harvesting the theoretical benefits of fiscal decentralization which would have been undermined by a mismatch between the two terms.

Countries following federal system of administration are observed to have greater level of fiscal decentralization. The three federal countries on average exhibited 48.4% expenditure revenue compared to the 10.5% of the unitary countries. The revenue decentralization also followed a similar trend with mean values of 48.8% in federal countries and 11.4% for in unitary states.

The average values of the two decentralization terms were lower than the respective mean values of the total sample including the OECD countries (Table 2). However, both the minimum and maximum values of revenue decentralization in the sample were exhibited by African countries.

Table 2.

Summary of the data used in the study.

| Sample Area | mean |

std |

min |

max |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Africa | Africa + OECD | Africa | Africa + OECD | Africa | Africa + OECD | Africa | Africa + OECD | |

| GDP | 6.49E+10 | 3.8E+11 | 1.16E+11 | 6.95E+11 | 1.6E+09 | 1.6E+09 | 4.87E+11 | 3.36E+12 |

| LND | 513810.1 | 728368.6 | 435238.6 | 1699914 | 2030 | 2030 | 1259200 | 8965590 |

| POP | 32527919 | 28112831 | 42367981 | 37251501 | 537415.8 | 344587.6 | 1.91E+08 | 190961846.6 |

| EF | 0.63 | 0.41 | 0.23 | 0.30 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.93 | 0.93 |

| RF | 0.57 | 0.48 | 0.26 | 0.26 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.86 | 0.86 |

| FDI | 2.82 | 3.34 | 3.84 | 5.38 | −2.76 | −6.30 | 18.69 | 27.78 |

| INF | 9.38 | 5.57 | 20.79 | 15.05 | −0.40 | −0.40 | 101.17 | 101.17 |

| EXP | 24.86 | 35.09 | 7.88 | 12.98 | 12.48 | 12.48 | 38.09 | 57.59 |

| JE | 41.37 | 62.55 | 20.44 | 27.94 | 10.90 | 10.90 | 81.70 | 97.80 |

| GI | 37.20 | 55.56 | 14.39 | 24.78 | 13.06 | 13.06 | 61.43 | 99.46 |

| TR | 31.63 | 30.77 | 6.90 | 7.19 | 15.00 | 12.00 | 52.50 | 52.50 |

If we compare the African countries to the OECD countries separately, we can notice that the average values for level of decentralization in African is still lagging behind. The average expenditure decentralization in Africa is less than half of the 30.28% for the OECD countries. The revenue decentralization is also smaller than the 18.27% average value for the OECD countries.

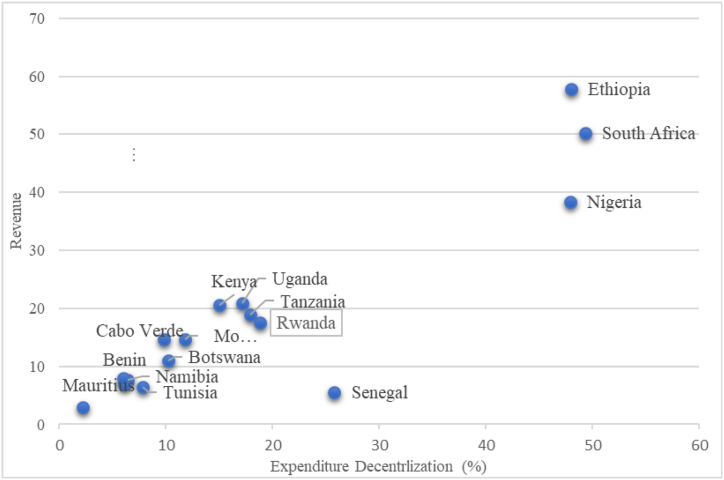

The largest level of revenue decentralization among the sampled African countries is observed in Ethiopia while South Africa scored the maximum in terms of expenditure dementalization. The minimum score in both indexes was counted in Mauritius (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Fiscal decentralization in African countries.

3. Data and method

3.1. Data

The availability of reliable and up-to-date data is a critical element that influences the results of empirical studies. The most significant challenges for this kind of study are properly measuring the extent of decentralization and finding reliable and credible data sources. The issue is more pronounced when the study focuses on developing nations as is the case in this study. Though the use of panel data consisting more than one year of data across the countries was what was intended in the beginning, the lack of data has forced us to use cross-sectional data. Thus, the analysis on time-to-time changes and resulting impacts as well as the interactions among the different tiers of governments within in the countries are out of the scope of this paper. However, in order to avoid measurement errors due to the short-term economic fluctuation, average values for the five years period between 2015 and 2019 are used for the dependent variables as recommended in most of similar studies [14,25]. The explanatory variables are for the year 2017 which at the middle of the 2013–2021 period.

The standard measures of fiscal decentralization utilized in most decentralization studies are the ratio of total subnational government revenues to general government revenues and the ratio of total subnational government expenditures to general government expenditures. These two fiscal decentralization indicators are also used here.

Expenditure Decentralization (ED): This is the ratio of the subnational governments’ total expenditure to the total government expenditure (equation (1)).

| (1) |

where “i" denotes the country.

Revenue Decentralization (RD): This is the ratio of the regional state's total revenue to the combined government and regional states' total revenue (equation (2)).

| (2) |

Within the framework of the preceding consideration, a cross-sectional data of selected 23 developing African countries and 23 OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) countries collected from the sources specified in Table 1 is used in this study. The first 23 countries are selected from the 34 OECD countries after the countries’ names are alphabetically sorted and Costa Rica, Estonia, Israel and New Zealand are removed due to missing data on ethnoreligious diversity and poverty. The dependent, independent and instrument variables used in the empirical analysis are summarized in Table 1. The statistical summary of the data used in the study and the sources of the data are provided in Table 2. Natural logarithms of the values are considered for all variables that are not fractions or scales.

3.2. Empirical analysis

The main aim of this study is evaluating the impact of fiscal decentralization on economic growth. Thus, it is expected that there would be a model or a couple of models which relate the dependent variable (LogGDPPC) to the fiscal decentralization indices and other explanatory variables. However, as it has been explained in greater detail in the introduction section, the empirical models are mostly suffering from endogeneity issue. The choice of this study is a proper selection and application of instrumental variables (IVs) in two-stage regression. A variety of this scheme in the forms of Two-stage Least squares (2SLS), Instrument Variables Generalized Method of Moments (IVGMM) and Limited information maximum likelihood (LIML) are applied. An ordinary least squares (OLS) model is also tried and presented for comparison. Heteroscedastic robust standard errors are used in to address the heteroscedasticity issue all of the regressions.

Our choice of methodology is motivated by previous studies such as [21,25,31,43], which have utilized similar approaches to examine the relationship between fiscal decentralization and economic growth. By adopting these established methods, we ensure consistency with the existing literature and build upon their findings.

The basic approach remains similar in the two-stage methods. The first stage of regression relates the fiscal decentralization term with the instrumental variables as shown in equations (3), (4). The second stage uses the predicted fiscal decentralization term from the first stage together with the other exogenous control variables to estimate the impact on GDP as shown in (5), (6).

Furthermore, we carefully select exogenous control variables based on their significant correlation with the dependent variable and their relevance as identified in related literature. These variables capture socioeconomic, geographic, and political factors that may influence the impact of fiscal decentralization on GDP. We have conducted correlation analysis to verify the suitability of the selected instrumental variables and have made necessary adjustments based on their correlation levels. As the result in Fig. A1 of the Annex shows, the RF and N_SNG showed very low correlation with decentralization terms. Thus, those variables are dropped from the IV expression in the respective models. The other issue is to check whether the IVs are exogenous themselves. The LogLND and LogPOP variables exhibited higher level of correlation as might be expected, which invalidates the assumption that all the IVs are exogenous. As a result, LogPOP, which proved to have lower level of correlation to the endogenous variables, was dropped.

In the first stage, the two fiscal decentralization measures (expenditure decentralization and revenue decentralization) are used as dependent variables and regressed against the instrument variables that represent socioeconomic, geographic and political situations of the countries (Eqs. (3) and (4)).

| (3) |

| (4) |

where the EDi and RDi are the expenditure decentralization and revenue decentralization endogenous variables; LogLNDi, EFi, RFi, FEDi are the instrument variables explained in Table 1 for each country “i”; εi and ηi are the residuals.

In the second stage, the dependent variable LogGDPPC is regressed against the endogenous variable (the fiscal decentralization term) and the other exogenous control variables as shown in Eqs. (5), (6).

| (5) |

| (6) |

where FDIi, INF+, EXPi, JEi, GIi, TRi, EDi are the control variables explained in Table 1 and μi and φi are the residuals.

Two sets of data, one consisting only of the sample 23 developing African countries and the other including another group of 23 OECD countries, are used to measure and contrast the impact of fiscal decentralization on GDP in the respective cases.

The models are developed and the regression analysis is performed using the statsmodels [38] and linearmodels python packages and further verified using Eviews. The choice of methodology is carefully considered and driven by the aim of evaluating the impact of fiscal decentralization on economic growth. Given the potential endogeneity issue associated with empirical models, a two-stage regression approach using instrumental variables (IVs) is employed. This method allows us to address endogeneity concerns and obtain more reliable estimates. Specifically, three variations of the two-stage regression method, namely Two-stage Least Squares (2SLS), Instrument Variables Generalized Method of Moments (IVGMM), and Limited Information Maximum Likelihood (LIML), are applied. Additionally, an Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) model is included for comparison purposes. The use of IVs and control variables is based on extensive review and correlation analysis, ensuring their relevance and exogeneity. By employing these methodologies, we aim to provide rigorous and robust analysis, enhancing the credibility and validity of our findings.

4. Results and analysis

4.1. Regression results

The regression results using the different estimating methods are presented in Tables 3 and 4. Looking at the R squared values, it would be perceived that OLS has produced the best model. However, the model is likely to be biased due to the endogeneity problem that was anticipated and proved later with the endogeneity tests. Thus, looking into details of the OLS result cannot give any tangible information regarding the true relationship between the fiscal decentralization terms and GDP. We will focus on results of the other estimation techniques. As it can be observed in both figures, the estimation results from all of the two-stage methods are not significantly different from one another in both their regression coefficients as well the significance levels. Values of the performance metrices do not show a big difference either. The 2SLS method, which marginally outperforms the others in terms of R-squared and F-statistic values, is chosen for the proceeding discussions. The models based on the dataset only on African countries are understandably less accurate compared to that of the full data set potentially due to the smaller sample size.

Table 3.

Regression results for the dataset consisting of both African and OECD countries.

| OLS |

2SLS |

IVGMM |

LIML |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EQ1 | EQ2 | EQ1 | EQ2 | EQ1 | EQ2 | EQ1 | EQ2 | |

| Dep. Variable | LogGDPPC | LogGDPPC | LogGDPPC | LogGDPPC | LogGDPPC | LogGDPPC | LogGDPPC | LogGDPPC |

| Estimator | OLS | OLS | IV-2SLS | IV-2SLS | IV-GMM | IV-GMM | IV-LIML | IV-LIML |

| No. Observations | 46 | 46 | 46 | 46 | 46 | 46 | 46 | 46 |

| Cov. Est. | robust | robust | robust | robust | robust | Robust | robust | robust |

| R-squared | 0.8033 | 0.7936 | 0.7973 | 0.7846 | 0.7962 | 0.7835 | 0.7968 | 0.7835 |

| Adj. R-squared | 0.767 | 0.7556 | 0.7599 | 0.7449 | 0.7586 | 0.7436 | 0.7593 | 0.7436 |

| F-statistic | 223.94 | 222.8 | 203.5 | 211.89 | 227.4 | 225.13 | 202.4 | 210.07 |

| P-value (F-stat) | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| const | 2.356 | 2.301 | 2.334 | 2.217 | 2.289 | 2.165 | 2.333 | 2.213 |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| FDI | 0.010 | 0.008 | 0.012 | 0.011 | 0.014 | 0.012 | 0.012 | 0.011 |

| (0.525) | (0.584) | (0.459) | (0.507) | (0.390) | (0.442) | (0.457) | (0.504) | |

| INF | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.002 |

| (0.276) | (0.306) | (0.293) | (0.357) | (0.249) | (0.273) | (0.294) | (0.360) | |

| EXP | 0.015 | 0.016 | 0.015 | 0.018 | 0.016 | 0.019 | 0.015 | 0.018 |

| (0.024) | (0.022) | (0.022) | (0.013) | (0.011) | (0.008) | (0.023) | (0.013) | |

| JE | 0.006 | 0.005 | 0.006 | 0.006 | 0.006 | 0.006 | 0.006 | 0.006 |

| (0.381) | (0.465) | (0.298) | (0.399) | (0.277) | (0.352) | (0.295) | (0.396) | |

| GI | 0.010 | 0.012 | 0.008 | 0.010 | 0.007 | 0.010 | 0.008 | 0.010 |

| (0.187) | (0.098) | (0.307) | (0.183) | (0.302) | (0.183) | (0.314) | (0.189) | |

| TR | −0.004 | −0.004 | −0.004 | −0.003 | −0.004 | −0.003 | −0.005 | −0.003 |

| (0.439) | (0.527) | (0.442) | (0.577) | (0.531) | (0.675) | (0.442) | (0.580) | |

| ED | 0.007 | 0.011 | 0.011 | 0.011 | ||||

| (0.031) | (0.004) | (0.001) | (0.004) | |||||

| RD | 0.006 | 0.011 | 0.011 | 0.011 | ||||

| (0.070) | (0.020) | (0.012) | (0.020) | |||||

| Instruments | LogLND | LogLND | LogLND | LogLND | LogLND | LogLND | ||

| EF | EF | EF | EF | EF | EF | |||

| RF | RF | RF | RF | RF | RF | |||

| FED.1 | FED.1 | FED.1 | FED.1 | FED.1 | FED.1 | |||

P-values reported right below the respective coefficients in parenthesis.

Table 4.

Regression results for the dataset consisting of only African countries.

| OLS |

2SLS |

IVGMM |

LIML |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EQ1 | EQ2 | EQ1 | EQ2 | EQ1 | EQ2 | EQ1 | EQ2 | |

| Dep. Variable | LogGDPPC | LogGDPPC | LogGDPPC | LogGDPPC | LogGDPPC | LogGDPPC | LogGDPPC | LogGDPPC |

| Estimator | OLS | OLS | IV-2SLS | IV-2SLS | IV-GMM | IV-GMM | IV-LIML | IV-LIML |

| No. Observations | 23 | 23 | 23 | 23 | 23 | 23 | 23 | 23 |

| Cov. Est. | robust | robust | robust | robust | robust | Robust | robust | robust |

| R-squared | 0.4532 | 0.5055 | 0.4421 | 0.5033 | 0.4427 | 0.4985 | 0.4406 | 0.503 |

| Adj. R-squared | 0.1981 | 0.2747 | 0.1817 | 0.2715 | 0.1826 | 0.2645 | 0.1796 | 0.2711 |

| F-statistic | 91.446 | 100.92 | 66.005 | 88.04 | 58.695 | 93.768 | 64.01 | 86.358 |

| P-value (F-stat) | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| const | 2.959 | 2.889 | 2.895 | 2.857 | 2.967 | 2.940 | 2.891 | 2.855 |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| FDI | −0.033 | −0.034 | −0.035 | −0.035 | −0.033 | −0.033 | −0.035 | −0.035 |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| INF | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.000 |

| (0.746) | (0.817) | (0.775) | (0.833) | (0.635) | (0.583) | (0.777) | (0.834) | |

| EXP | 0.013 | 0.013 | 0.016 | 0.014 | 0.016 | 0.012 | 0.016 | 0.014 |

| (0.173) | (0.151) | (0.124) | (0.137) | (0.073) | (0.091) | (0.121) | (0.136) | |

| JE | 0.004 | 0.004 | 0.004 | 0.004 | 0.004 | 0.005 | 0.004 | 0.004 |

| (0.606) | (0.540) | (0.573) | (0.521) | (0.542) | (0.502) | (0.571) | (0.520) | |

| GI | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.002 | 0.000 | 0.001 |

| (0.899) | (0.883) | (0.979) | (0.929) | (0.983) | (0.808) | (0.972) | (0.932) | |

| TR | −0.009 | −0.008 | −0.008 | −0.007 | −0.011 | −0.010 | −0.008 | −0.007 |

| (0.354) | (0.407) | (0.403) | (0.434) | (0.270) | (0.292) | (0.406) | (0.436) | |

| ED | 0.010 | 0.013 | 0.012 | 0.013 | ||||

| (0.001) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | |||||

| RD | 0.011 | 0.013 | 0.011 | 0.013 | ||||

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | |||||

| Instruments | LogLND | LogLND | LogLND | LogLND | LogLND | LogLND | ||

| EF | EF | EF | EF | EF | EF | |||

| RF | RF | RF | RF | RF | RF | |||

| FED.1 | FED.1 | FED.1 | FED.1 | FED.1 | FED.1 | |||

P-values reported right below the respective coefficients in parenthesis.

4.2. Regression result analysis

Model 1 examines the impact of expenditure decentralization on per capita GDP by employing equation (5) at the first stage and equation (3) in the second stage. The results demonstrate that expenditure decentralization has a small but significant coefficient in both datasets. Interestingly, in the dataset focusing on developing African countries (Table 4), the coefficient of expenditure decentralization is slightly larger, and the p-value is slightly smaller, indicating an even greater level of significance compared to the dataset including OECD countries (Table 3). This implies that expenditure decentralization has a significant positive impact on per capita GDP, and this impact is equally notable in developing African countries. Specifically, a 1-unit improvement in expenditure decentralization resulted in a 1.126% increase in per capita GDP in the whole dataset and a 1.258% increase in the African countries dataset.

These results contradict earlier studies such as [14] which reported a negative relationship between expenditure decentralization and economic growth in world and developing country samples. It is important to note that the Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) method used in Ref. [14] may suffer from endogeneity issues, and the quality of data, particularly for developing countries during that time, is questionable. In contrast, studies such as [21,25], which utilized instruments or advanced econometric techniques like two-step system Generalized Method of Moments (GMM), have come to similar conclusions as this study.

Moving to Model 2, which examines the impact of revenue decentralization on per capita GDP using Eq. (6) at the first stage and Eq. (4) in the second stage, the results again indicate a significant positive contribution of revenue decentralization to a country's economy in both groups of countries. The coefficient and p-value of the decentralization term remain consistent in both datasets, although the impact is slightly larger in the African countries' dataset. Specifically, a 1-unit increase in revenue decentralization leads to a 1.126% increase in per capita GDP in the African countries' dataset, compared to 1.086% in the whole dataset.

These findings present a contrasting argument to Ref. [39], who found revenue decentralization, measured by tax decentralization, to have an insignificant impact on economic growth. However, recent studies like reference [9] have raised concerns about the robustness of the methods and results used in previous research. Reference [36], for instance, using OLS regression and data from emerging economies in Europe, demonstrated a negative impact of revenue decentralization on economic growth, opposing the positive impact of expenditure decentralization. On the other hand, reference [20] reported a positive impact of revenue (tax) decentralization on economic growth. Furthermore [21], employing two-step system GMM and data from federal countries, concluded that both tax revenue decentralization and expenditure decentralization play a positive role in advancing economic growth. The conflicting results in the literature could be attributed to various factors, including endogeneity, the robustness of regression techniques, and data quality.

Another notable observation from the regression results is the varying impacts of foreign direct investment (FDI) and the GDP share of government expenditure across the two datasets. FDI demonstrates a significant impact in the sampled developing African countries, whereas its impact is not significant in the whole dataset. Conversely, the GDP share of government expenditure is a significant variable impacting per capita GDP in all the sampled countries, but its impact is not as pronounced in African countries specifically.

The empirical analysis reveals that decentralizing both expenditure and revenue is a significant and positive approach to foster economic growth in a country. This finding aligns with studies such as [21,25,31] while differing from Refs. [5,14,24,36,44]. It is worth noting that the impact of expenditure decentralization appears slightly larger than that of revenue decentralization. Importantly, the results challenge the claim by Ref. [44] that fiscal decentralization is suitable only for developed countries. In fact, the comparative analysis shows that decentralization has an even greater impact on developing African countries, albeit by a small margin.

The findings from this empirical analysis strongly support fiscal decentralization as a vital tool for promoting economic development in developing countries. The results underscore the positive impact of both revenue and expenditure decentralization, making it clear that promoting one while discouraging the other solely based on the interpretation of regression coefficients would be impractical and possibly counterproductive due to the interplay between the two terms and resulting vertical imbalance. Therefore, this study provides empirical support for the commitment of developing African countries and supporting organizations to advance fiscal decentralization as a means to stimulate economic growth.

4.3. Diagnostic and robustness tests

Series of diagnostic tests and robustness checks re applied to assess the validity and reliability of the instrumental variable approach and the overidentification assumptions in the 2SLS estimation.

Looking in to the first stage statistics provided in Table 5, for the variable “ED,” the instruments used in the first stage explain approximately 71.3% of the variation, with about 57.9% representing the unique variation after accounting for other exogenous variables. The F-statistic of 65.767 indicates the joint significance of the instruments, and the small p-value (1.77E-13) suggests strong evidence against the null hypothesis. Similarly, for the variable “RD,” the instruments explain around 68.4% of the variation, with 63.5% representing the unique variation. The F-statistic of 75.634 is significant, and the p-value (1.44E-15) provides strong evidence against the null hypothesis. In both models, the first-stage statistics indicate the instruments' relevance and effectiveness in explaining the respective endogenous variables.

Table 5.

First-stage statistics.

| R2 | Partial R2 | Shea R2 | f.stat | f.pval | f.dist | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ED | 0.713 | 0.579 | 0.579 | 65.767 | 1.77E−13 | chi2 (4) |

| RD | 0.684 | 0.635 | 0.635 | 75.634 | 1.44E−15 | chi2 (4) |

Results of the overidentification testes are presented in Table 6. The Sargan's test of overidentification examines whether the model is overidentified. The test statistic is 1.0473 with a p-value of 0.7898, indicating that we do not reject the null hypothesis. Similarly, the Basmann's test of overidentification yields a test statistic of 0.8154 with a p-value of 0.8458, again suggesting that the model is not overidentified. Additionally, Wooldridge's overidentification test confirms that the instrumental variables (LogLND, EF, RF, and FED) used in both models are valid, as the 2SLS residuals are found to be uncorrelated with the instruments. This further supports the appropriateness of using these variables as instruments in the regression analysis.

Table 6.

Tests of overidentification.

| Parameters | Sargan's test | Basmann's test | Wooldridge's score test | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Statistic | 1.0473 | 0.8154 | 0.7083 |

| P-value | 0.7898 | 0.8458 | 0.8712 | |

| Distributed | chi2 (3) | chi2 (3) | chi2 (3) | |

| Model 2 | Statistic | 1.5855 | 1.2494 | 0.9064 |

| P-value | 0.6627 | 0.7412 | 0.8239 | |

| Distributed | chi2 (3) | chi2 (3) | chi2 (3) |

H0: The model is not overidentified.

The Wu-Hausman test of exogeneity was performed on Model 1 and Model 2. For both models, the null hypothesis assumed that all endogenous variables are exogenous. The test results (Table 7) showed that there is no significant evidence of endogeneity in either model, as the p-values were greater than the significance level. Therefore, the endogenous variables in both models are likely exogenous and not correlated with the error term.

Table 7.

Wu-Hausman test results.

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| H0 | All endogenous variables are exogenous | |

| Statistic | 2.1039 | 3.8250 |

| P-value | 0.1554 | 0.0581 |

| Distributed | F (1,37) | F (1,37) |

The Anderson-Rubin test was conducted to assess the strength of the instruments in two models (Table 8). In Model 1, the test yielded a statistic of 1.0581 with a p-value of 0.7872, while Model 2 had a statistic of 1.6096 with a p-value of 0.6572. In both cases, the p-values were greater than the significance level, indicating that there is no sufficient evidence to reject the null hypothesis. Therefore, the instruments used in both models are not considered weak.

Table 8.

Anderson-Rubin test results.

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| H0 | The model is not overidentified | |

| Statistic | 1.0581 | 1.6096 |

| P-value | 0.7872 | 0.6572 |

5. Conclusion and recommendations

This study provides robust empirical evidence on the impact of fiscal decentralization on economic growth, with a specific focus on developing African countries. By utilizing data from 23 African countries and 23 OECD countries, the study employed a two-stage regression approach using instrumental variables and advanced econometric techniques, such as 2SLS, GMM, and LIML estimations. The analysis included a set of exogenous control variables that exhibited significant correlations with the dependent variable.

The key finding of this study is that both expenditure decentralization and revenue decentralization have a significant positive impact on a country's per capita GDP. The coefficient of expenditure decentralization was slightly larger and more significant in the dataset of developing African countries, indicating an even greater level of impact compared to the dataset including OECD countries. Specifically, a 1-unit improvement in expenditure decentralization resulted in a 1.258% increase in per capita GDP in the African countries dataset, while the impact was slightly smaller but still significant at 1.086% in the whole dataset. These findings contradict earlier studies, such as [14], which reported a negative relationship between expenditure decentralization and economic growth. The utilization of instrument variables and advanced econometric techniques in this study contributes to its robustness and supports similar conclusions found in studies like [21,25].

The analysis also examined the impact of revenue decentralization on per capita GDP. The results indicated a significant positive contribution of revenue decentralization to a country's economy in both groups of countries. While the impact of revenue decentralization was slightly larger in the African countries' dataset, the coefficient and p-value remained consistent in both datasets. Specifically, a 1-unit increase in revenue decentralization led to a 1.126% increase in per capita GDP in the African countries' dataset and a 1.086% increase in the whole dataset. These findings contrast with the findings of [39], who reported an insignificant impact of revenue decentralization on economic growth. Conflicting results in the literature, such as the negative impact reported by Ref. [36] and the positive impact reported by Ref. [20], could be attributed to differences in methodologies, data quality, and the inclusion of control variables.

Furthermore, the analysis revealed varying impacts of foreign direct investment (FDI) and the GDP share of government expenditure across the two datasets. FDI demonstrated a significant impact in the sampled developing African countries, while its impact was not significant in the whole dataset. On the other hand, the GDP share of government expenditure significantly impacted per capita GDP in all the sampled countries, but its impact was not as pronounced in African countries specifically.

In conclusion, this study provides robust empirical evidence supporting fiscal decentralization as an effective tool for promoting economic growth, particularly in developing African countries. The results emphasize the positive impacts of both expenditure decentralization and revenue decentralization, underscoring the importance of pursuing both approaches rather than favoring one over the other. These findings challenge the notion that fiscal decentralization is only suitable for developed countries and highlight its even greater impact on developing African countries. It is crucial for governments in these countries to recognize fiscal decentralization as an internal tool for economic development and reduce reliance on external aids, loans, and investments. The study's findings have important implications for policymakers and development organizations, reaffirming the significance of advancing fiscal decentralization as a means to stimulate economic growth and foster sustainable development in developing countries, particularly in Africa.

The findings of this study have important policy implications for governments and development organizations aiming to promote economic growth and development in developing African countries. The empirical evidence supports the implementation of fiscal decentralization as a key policy tool. The following policy implications can be drawn from the study:

-

1.

Embrace Fiscal Decentralization: Governments of developing African countries should recognize and embrace fiscal decentralization as an effective internal tool for economic development. The positive impact of both expenditure decentralization and revenue decentralization on per capita GDP highlights the need to devolve financial powers and decision-making authority to subnational levels. Policymakers should prioritize decentralization efforts, ensuring that resources and responsibilities are transferred to regional and local governments.

-

2.

Focus on Expenditure Decentralization: The study found that expenditure decentralization has a slightly larger positive impact on economic growth compared to revenue decentralization. Therefore, policymakers should give particular attention to decentralizing expenditure responsibilities to subnational levels. This implies allocating budgetary authority and spending responsibilities to local governments, allowing them to address the specific needs and priorities of their communities.

-

3.

Strengthen Institutional Capacity: Effective fiscal decentralization requires strong institutional capacity at subnational levels. Governments should invest in building the administrative and technical capabilities of local governments to ensure efficient utilization of decentralized resources. This includes providing training, technical assistance, and financial support to enhance their governance, financial management, and service delivery capacities.

-

4.

Foster Collaboration and Coordination: While decentralization empowers subnational entities, it is essential to foster collaboration and coordination between different levels of government. Policymakers should establish mechanisms for intergovernmental cooperation, ensuring coherence in policy implementation, resource allocation, and service delivery. This can be achieved through regular dialogue, information sharing, and joint decision-making processes.

-

5.

Monitor and Evaluate Decentralization Efforts: It is crucial to establish monitoring and evaluation mechanisms to assess the effectiveness and impact of decentralization efforts. Governments should collect and analyze relevant data on key indicators of economic growth, fiscal performance, and service delivery at both national and subnational levels. Regular evaluations will help identify challenges, measure progress, and inform evidence-based policy adjustments.

-

6.

Enhance Revenue Mobilization Capacities: Revenue decentralization relies on subnational governments' ability to generate their own revenues. Policymakers should support local governments in enhancing their revenue mobilization capacities through measures such as tax administration reforms, expanding revenue sources, and improving compliance. This will enable subnational entities to finance their expenditure responsibilities and reduce dependence on central government transfers.

-

7.

Learn from International Best Practices: Developing African countries can benefit from studying successful experiences of fiscal decentralization in other regions and countries. Governments should engage in knowledge exchange, seek technical assistance from international organizations, and learn from the best practices of countries that have effectively implemented fiscal decentralization. This will help in designing context-specific decentralization policies and adapting them to local circumstances.

-

8

Address Vertical Imbalances: As decentralization progresses, it is crucial to address vertical imbalances between central and subnational governments. Policymakers should ensure an equitable distribution of resources and fiscal powers, avoiding over-centralization or excessive concentration of decision-making authority. Balancing the autonomy and accountability of subnational entities with the need for coordination and national policy objectives is essential for successful fiscal decentralization.

It is important to note that while the findings of this study provide empirical support for fiscal decentralization, implementing decentralization reforms requires careful planning, coordination, and consideration of country-specific contexts. Policymakers should take into account local political, economic, and social dynamics when formulating and implementing decentralization policies. Continuous monitoring, evaluation, and adaptation of policies based on evidence and feedback from stakeholders will contribute to the effectiveness and sustainability of fiscal decentralization efforts in developing African countries.

Future research should focus on exploring the causal mechanisms underlying the relationship between fiscal decentralization and economic growth. Sectoral analyses, investigating the quality of decentralized governance, and studying the long-term effects of decentralization can provide valuable insights. Additionally, examining subnational variation, conducting comparative analyses, and studying the design and implementation of decentralization policies are important areas for further investigation.

Future research should explore the causal mechanisms underlying the relationship between fiscal decentralization and economic growth. Sectoral analyses, investigation of governance quality, long-term effects, subnational variation, comparative analysis, and examination of policy design and implementation are important avenues for further exploration. Addressing these research gaps will enhance our understanding of fiscal decentralization's impact and inform evidence-based policymaking for sustainable development.

The study is subject to several limitations that should be acknowledged. First, the availability and quality of data may have affected the accuracy of the analysis. Second, establishing a causal relationship between fiscal decentralization and economic growth is challenging due to endogeneity. Third, the chosen measures of decentralization may not fully capture its multidimensional nature. Fourth, the heterogeneity among countries included limits the generalizability of the findings. Fifth, alternative model specifications or approaches could yield different results. Sixth, the study's focus on short-term effects overlooks long-term dynamics and contextual factors. Lastly, unaccounted external factors may have influenced the observed relationship. Addressing these limitations in future research will enhance the study's validity and contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of the topic.

Author contribution statement

Melat Sima: Conceived and designed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Wrote the paper.

Peng Liang: Performed the experiments.

Zhou Qingjie: Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data.

Funding statement

This research was funded by National Social Science Fund of China (No. 21BJY192).

Data availability statement

Data included in article/supplementary material/referenced in article.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e19520.

Angola, Benin, Botswana, Cabo Verde, Cameroon, Chad, Eswatini, Ethiopia, Ivory Coast, Kenya, Malawi, Mauritius, Morocco, Mozambique, Namibia, Nigeria, Rwanda, Senegal, South Africa, Tanzania, Tunisia, Uganda and Zimbabwe.

Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Czech Republic, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Mexico, Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Poland and Slovak Republic.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.African Union . African Union Agenda 2063; 2020. Goals & Priority Areas of Agenda 2063. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alesina A., Devleeschauwer A., Easterly W., Kurlat S., Wacziarg R. Fractionalization. J. Econ. Growth. 2003 doi: 10.1023/A:1024471506938. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ali M., Hashmi S.H., Nazir M.R., Bilal A., Nazir M.I. Does financial inclusion enhance economic growth? Empirical evidence from the IsDB member countries. Int. J. Finance Econ. 2021;26(4) doi: 10.1002/ijfe.2063. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ali M., Nazir M.I., Hashmi S.H., Ullah W. Financial inclusion, institutional quality and financial development: empirical evidence from oic countries. Singapore Econ. Rev. 2022;67(1) doi: 10.1142/S0217590820420084. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alison M., Lewis W.A. Patterns of public revenue and expenditure. Manch. Sch. Econ. Soc. Stud. 1956;24:203–244. [Google Scholar]

- 6.AU African charter on the values and principles of decentralisation. Local Govern. Local Dev. 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 7.AU . 2021. List of Countries Which Have Signed, Ratified/Acceded to the African Charter on the Values and Principles of Decentralisation, Local Governance and Local Development.https://au.int/sites/default/files/treaties/36387-sl-AFRICAN CHARTER ON THE VALUES AND PRINCIPLES OF DECENTRALISATION%2C LOCAL pdf [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bahl R.W., Nath S. Public expenditure decentralization in developing countries. Environ. Plann. C: Govern. Policy. 1986 doi: 10.1068/c040405. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baskaran T., Feld L.P. Fiscal decentralization and economic growth in OECD countries: is there a relationship? Publ. Finance Rev. 2013 doi: 10.1177/1091142112463726. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brady G.L., Magazzino C. Fiscal sustainability in the EU. Atl. Econ. J. 2018;46(3) doi: 10.1007/s11293-018-9588-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Canavire-Bacarreza G., Martinez-Vazquez J., Yedgenov B. Reexamining the determinants of fiscal decentralization: what is the role of geography? J. Econ. Geogr. 2016 doi: 10.1093/jeg/lbw032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Canavire-Bacarreza G., Martinez-Vazquez J., Yedgenov B. Identifying and disentangling the impact of fiscal decentralization on economic growth. World Dev. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2019.104742. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chigwata T.C., Ziswa M. Entrenching decentralisation in Africa: a review of the African charter on the values and Principles of decentralisation, local governance and local development. Hague J. Rule Law. 2018;10:295–316. doi: 10.1007/s40803-018-0070-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Davoodi H., Zou H. Fiscal decentralization and economic growth: a CrossCountry study. J. Urban Econ. 1998;43:244–257. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Di Liddo G., Magazzino C., Porcelli F. Government size, decentralization and growth: empirical evidence from Italian regions. Appl. Econ. 2018;50(25) doi: 10.1080/00036846.2017.1409417. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Faria H.J., Morales D.R., Pineda N., Montesinos H.M. Can capitalism restrain public perceived corruption? Some evidence. J. Inst. Econ. 2012;8(4) doi: 10.1017/S1744137412000070. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Filippetti A., Sacchi A. Decentralization and economic growth reconsidered: the role of regional authority. Environ. Plann. C: Govern. Policy. 2015 doi: 10.1177/0263774X16642230. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fisman R., Gatti R. Decentralization and corruption: evidence across countries. J. Publ. Econ. 2002;83(3) doi: 10.1016/S0047-2727(00)00158-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brennan G., Buchanan J.M. Cambridge University Press; 1980. The Power to Tax: Analytical Foundations of a Fiscal Constitution. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gemmell N., Kneller R., Sanz I. Fiscal decentralization and economic growth: spending versus revenue decentralization. Econ. Inq. 2013 doi: 10.1111/j.1465-7295.2012.00508.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hanif I., Wallace S., Gago-de-Santos P. SAGE Open; 2020. Economic Growth by Means of Fiscal Decentralization: an Empirical Study for Federal Developing Countries. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hobdari N., Nguyen V., Dell'Erba S., Ruggiero E. Lessons for effective fiscal decentralization in sub-saharan Africa. Departmental Papers/Policy Papers. 2018;18(10) doi: 10.5089/9781484358269.087. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.https://www.mapchart.net/world.html. (n.d.).

- 24.Hung N.T., Thanh S.D., McMillan D. Fiscal decentralization, economic growth, and human development: empirical evidence. Cogent Econ. Finance. 2022;10(1) doi: 10.1080/23322039.2022.2109279. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Iimi A. Decentralization and economic growth revisited: an empirical note. J. Urban Econ. 2005 doi: 10.1016/j.jue.2004.12.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.IMF Union of the Comoros: selected issues and statistical Appendix. IMF Staff Country Rep. 2006 doi: 10.5089/9781451809183.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jilek M. Proceedings of the 23rd International Conference Theoretical and Practical Aspects of Public Finance 2018. 2018. Determinants of fiscal decentralization - the recent evidence in European countries. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ligthart J.E., van Oudheusden P. The fiscal decentralisation and economic growth nexus revisited. Fisc. Stud. 2017 doi: 10.1111/1475-5890.12099. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Magazzino C. Fiscal variables and growth convergence in the ECOWAS. African J. Econ. Manag. Stud. 2016;7(2) doi: 10.1108/AJEMS-03-2015-0032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miller T., Kim A.B., Roberts J.M. The Heritage Foundation; 2022. 2020 Index of Economic Freedom. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Oates W.E. 1972. Fiscal Federalism. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Oates W.E. Searching for leviathan: an empirical study. Am. Econ. Rev. 1985;75(4):748–757. doi: 10.2307/1821352. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Oates W.E. An essay on fiscal federalism. J. Econ. Lit. 1999;37(3) doi: 10.1257/jel.37.3.1120. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.OECD . 2021. Yaoundé Declaration with List of Signatories.https://www.oecd.org/tax/transparency/what-we-do/technical-assistance/Yaounde-Declaration-with-Signatories.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 35.Office of International Religious Freedom . Eswatini; 2021. 2020 Report on International Religious Freedom. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pasichnyi M., Kaneva T., Ruban M., Nepytaliuk A. Investment Management and Financial Innovations. 2019. The impact of fiscal decentralization on economic development. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rodden J. The dilemma of fiscal federalism: grants and fiscal performance around the world. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 2002;46(3) doi: 10.2307/3088407. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Seabold S., Perktold J. Proceedings of the 9th Python in Science Conference. 2010. Statsmodels: econometric and statistical modeling with Python. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thornton J. Fiscal decentralization and economic growth reconsidered. J. Urban Econ. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.jue.2006.06.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.UCLG . 2020. The Localization of the Global Agendas How Local Action Is Transforming Territories and Communities: the GOLD V Regional Report on Africa. [Google Scholar]

- 41.UCLG Africa . 2019. Africities 7 Summit Political Report. [Google Scholar]

- 42.UNDP . 2021. Sustainable Development Goals.https://www.africa.undp.org/content/rba/en/home/sustainable-development-goals.html [Google Scholar]

- 43.Weingast B.R. The economic role of political institutions: market-preserving federalism and economic development. J. Law Econ. Organ. 1995;11(1) doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jleo.a036861. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wheare K.C. fourth ed. Oxford University Press; 1964. Federal Government. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Woo Sik Kee Fiscal decentralization and economic development. Publ. Finance Rev. 1977 doi: 10.1177/109114217700500106. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.World Bank . 2017. World Development Index. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yatta F., Vaillancourt F. GOLD 2010 (UCLG) 2010. Second global report on decentralization and local democracy: Africa. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data included in article/supplementary material/referenced in article.