Summary

Background

After primary vaccination schemes with rAd26-rAd5 (Sputnik V), ChAdOx1 nCoV-19, BBIBP-CorV or heterologous combinations, the effectiveness of homologous or heterologous boosters (Sputnik V, ChAdOx, Pfizer-BioNTech, Moderna) against SARS-CoV-2 infections, hospitalisations and deaths has been scarcely studied.

Methods

Test-negative, case–control study, conducted in Argentina during omicron BA.1 predominance, in adults ≥50 years old tested for SARS-CoV-2 who had received two or three doses of COVID-19 vaccines. Outcomes were COVID-associated infections, hospitalisations and deaths after administering mRNA and vectored boosters, < or ≥60 days from the last dose.

Findings

Of 422,124 individuals tested for SARS-CoV-2, 221,993 (52.5%) tested positive; 190,884 (45.2%) and 231,260 (54.8%) had received 2-dose and 3-dose vaccination schemes, respectively. The 3-dose scheme reduced infections, hospitalisations and death (OR 0.81 [0.80–0.83]; 0.28 [0.25–0.32] and 0.25 [0.22–0.28] respectively), but protection dropped after 60 days to 1.04 [1.01–1.06]; 0.52 [0.44–0.61] and 0.38 [0.33–0.45]). Compared with 2-dose-schemes, homologous boosters after primary schemes with vectored-vaccines provided lower protection against infections < and ≥60 days (0.94 [0.92–0.97] and 1.05 [1.01–1.09], respectively) but protected against hospitalisations (0.30 [0.26–0.35]) and deaths (0.29 [0.25–0.33]), decreasing after 60 days (0.59 [0.47–0.74] and 0.51 [0.41–0.64], respectively). Heterologous boosters protected against infections (0.70 [0.68–0.71]) but decreased after 60 days (1.01 [0.98–1.04]) and against hospitalisations and deaths (0.26 [0.22–0.31] and 0.22 [0.18–0.25], respectively), which also decreased after 60 days (0.43 [0.35–0.53] and 0.33 [0.26–0.41], respectively). Heterologous boosters protected against infections when applied <60 days (0.70 [0.68–0.71], p < 0.001), against hospitalisations when applied ≥60 days (0.43 [0.35–0.53], p < 0.01), and against deaths < and ≥60 days (0.22 [0.18–0.25], p < 0.01 and 0.33 [0.26–0.41], p < 0.001).

Interpretation

During omicron predominance, heterologous boosters such as viral vectored and mRNA vaccines, following Sputnik V, ChAdOx1, Sinopharm or heterologous primary schemes might provide better protection against death; this effect might last longer in individuals aged ≥50 than homologous boosters.

Funding

None.

Keywords: Vaccination

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

The advantages of applying heterologous boosters to improve the immunological response against variants of concern (VOCs) of SARS-CoV-2 has been demonstrated in experimental and real-world studies. We found there is a great amount of evidence that shows the beneficial outcomes of mRNA vaccines as homologous or heterologous boosters. Therefore, we focused our search on studies about the utilization of vectored or inactivated vaccines.

We searched preprint and peer-reviewed published articles in PubMed, medRxiv, and SSRN for observational studies, with no language restrictions, using the term “COVID-19 OR SARS-CoV-2” AND “vaccine effectiveness” OR “vaccine impact” AND “homologous” AND “heterologous” AND “booster” OR “third dose” AND “waning”, published between 1 December 2021 and 1 September 2022.

However, there is scarce information about the protection achieved and the duration of the effect of homologous or heterologous boosters applied after primary vaccination with inactivated viral vaccine BBIP-CorV, viral vectored vaccine rAd26-rAd5, or different heterologous vaccines combinations.

Added value of this study

Our observations show that administration of heterologous boosters might provide enhanced protection and longer effect duration against COVID-19-related deaths in individuals older than 50 compared to homologous boosters, during omicron predominance. The scheme of inactivated vaccine followed by a viral vectored booster seemed to be associated with the best protection against death.

Implications of all the available evidence

The implications of our findings thus support the utilisation of heterologous boosters to reach durable vaccine protection, especially in populations in which viral vectored or inactivated vaccines were applied as primary schemes.

Introduction

The emergence of the highly transmissible omicron (B.1.1.529) variant of concern (VOC), able to partially evade the immune response achieved after vaccination or natural infection, has caused an extraordinary increase in COVID-19 cases worldwide.1 As evidence of waning of immunity generated by mRNA vaccines began to surface, many countries started to administer a booster to improve vaccine response against omicron at the end of 2021 since vaccine effectiveness (VE) can be restored with a booster dose.2 Thus far, most reports about boosters refer to the administration of the same mRNA vaccines administered in primary schemes.3,4

Argentina began a massive vaccination roll-out on December 29, 2020, with the recombinant adenovirus (rAd)-based vaccine rAd26-rAd5 (Sputnik V, from Gamaleya National Research Center for Epidemiology and Microbiology).5 In the context of decreased vaccine availability across the world, the Argentine Ministry of Health incorporated other immunisation schedules, which included: the vectored vaccines ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 (referred to as ChAdOx1, from Oxford University and AstraZeneca) and CanSinoBIO Ad5-nCoV-S (CanSino, from CanSino Biologics Inc), the inactivated viral SARS-CoV-2 vaccine BBIBP-CorV (Sinopharm, from Beijing Institute of Biological Products Co); and the mRNA vaccines BNT162b2 (PfizerBNT, from Pfizer-BioNTech) and mRNA-1273 (Moderna).6 To achieve widespread vaccine coverage in the shortest possible time, Argentina started using heterologous vaccination schemes in July 2021. Recommendations about this strategy are available in the literature; furthermore, the advantages of applying heterologous boosters to improve the immunological response against VOCs, including omicron, have also been demonstrated in experimental and real-world studies.4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23

There is scarce information in real-world studies about the protection achieved and duration of homologous or heterologous boosters following a primary vaccination course with Sinopharm, Sputnik V, or heterologous vaccine schemes.11,23 In view of this, we formulated the following research question: With respect to individuals that had previously received Sputnik V, ChAdOx1, Sinopharm or heterologous schemes as the primary series vaccination during the period of omicron BA.1 predominance: Did the administration of heterologous boosters, such as viral vectored and mRNA vaccines, increase vaccine effectiveness for laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infections, COVID-associated hospitalisations, and COVID-associated deaths compared to the administration of homologous boosters?

Methods

Study population and design

This study used a test negative case–control design, which has proven to limit bias resulting from testing and healthcare seeking behaviour.24,25 Subjects eligible for inclusion were those ≥50 years with residence in the Province of Buenos Aires, that had received at least two doses of COVID-19 vaccines by 1 January 2022, and had been tested for SARS-CoV-2 between 1 January and 1 April, 2022. Exclusion criteria were having had a previous positive RT-PCR or antigen tests for SARS-CoV-2 in the previous 90 days, having received none, one, or four doses of any vaccine, or having a laboratory-confirmed test within 14 days of vaccination. 14 days were selected based on immunological studies that state the response to any vaccine requires at least 2 weeks to evolve. Therefore, any breakthrough infection occurring before that period could not be attributed to the vaccine's lack of effectiveness.12,16,26 We compared hospitalised individuals with positive COVID tests against testing negative, and individuals who died following a positive COVID test against those testing negative.11,13, 14, 15, 16,19,20,24

We assessed vaccine performance during the period of omicron B.1.1.529 predominance (1 January–1 April 2022), as detected by the National Ministry of Health's genomic surveillance program for identifying VOCs through RT-PCR laboratory-confirmation.27

Data sources and definitions

This study used epidemiological surveillance data from the National Surveillance System (SNVS 2.0) which is the centralised disease notification system of the National Ministry of Health.28 Only authorised health personnel can upload information. The database registers age, sex, site of residence (Greater Buenos Aires or not) and presence or absence of the following comorbidities: arterial hypertension, smoking habit, asthma, diabetes, ex-smoker, pregnancy, obesity, heart disease, neurological disease, onco-haematological diseases, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, kidney disease, immunodeficiencies, previous pneumonia, liver disease, preterm birth, low birth weight, tuberculosis, acute and chronic haemodialysis. Forms displayed the following list of conditions cited above. If the patient had at least one condition, personnel should tick the box corresponding to the comorbidity as “Yes”. They also register information on SARS-CoV-2 infections obtained using RT-PCR or antigen test. For diagnostic purposes, both tests were considered. The individual was considered a case (positive PCR/antigen test) according to an internal algorithm, shown in the Supplementary material (Supplementary Table S1).

During the study period, only symptomatic cases were tested according to the standards established by the Province of Buenos Aires. Data on infections were recorded until 1 April 2022, and on COVID-associated hospitalisations and COVID-associated deaths until 28 April 2022 (Supplementary Figure S1). Information about deaths was further validated with the Registry of Persons of the Province of Buenos Aires.5,6 The date of confirmed-laboratory SARS-CoV-2 infection was identified by symptom-onset date or, if not available, the date of the sample collected for the COVID-19 test. Number of positive tests in the past, total number of previous tests and dates of COVID-associated hospitalisations and COVID-associated deaths were also registered.

The first positive test during the study period was considered a case for primary analysis, regardless of the number of previous negative tests. Controls were those individuals who tested negative over the entire study period and the date of their first test was considered for analysis. Individuals could be included only once for each outcome.

Vaccination information was collected in Vacunate PBA, a system developed in the Province of Buenos Aires, Argentina, to address the rollout of the COVID-19 vaccination campaign. Registration was voluntary and was carried out by individuals via Android and IOS applications or via the specially designed website Vacunate PBA.29 Previously trained health personnel registered vaccination date, number of doses, vaccine type, vaccine lot number, and vaccination centre. The data in both databases (VacunatePBA and National Surveillance System (SNVS 2.0)) were linked via ID number and sex. Data not coinciding in either database were discarded from the analysis; their number was reported under the category of “Registration and programming errors” in the flowchart of the study.

Vaccination status was verified on the day the SARS-CoV-2 test was performed.

In Argentina, vaccines of three different platforms were utilised: vectored-based (Sputnik V, ChAdOx1 and CanSino), mRNA (Pfizer-BNT and Moderna) and inactivated virus (Sinopharm) (Supplementary Table S2).

In December 2020, Argentina started the vaccination campaign against COVID-19 with Sputnik V and progressively incorporated ChAdOx1, Sinopharm, CanSino, Pfizer-BNT, Moderna vaccines, and combinations of Sputnik V component 1/Moderna, Sputnik V/ChAdOx1, and Sputnik V/CanSino, among others, in settings of limited vaccine availability.30,31

Vaccination rollout developed according to recommendations from the National Ministry of Health, prioritising individuals with higher risk of COVID-19. Thus, the campaign first targeted individuals >60 with any comorbidity and then continued with those belonging to the same group, but without comorbidities (Supplementary Figure S2).

The primary vaccination series initially consisted of two doses with a minimum interval of 21- or 28-day for immunocompetent subjects, or three doses with a 28-day interval for immunocompromised adults.30 Importantly, the immunocompromised did not receive different vaccines than the rest of the population. In March 2021, the first dose of viral-vectored vaccines (Sputnik V and ChAdOx1) was prioritised due to low availability of vaccines and delayed the second dose for at least 90 days. The interval between doses with the Sinopharm vaccine was left at 28 days.32

On October 28 2021, the WHO recommended an additional dose for individuals aged >50 who had received a primary series with inactivated vaccines.33 On November 10 2021, a booster dose with either Sputnik V, ChAdOx1, CanSino, Pfizer-BNT or a half dose (50 μg) of Moderna was introduced for adults aged >70 and for those in high-risk groups.34

The recommended interval between the initial scheme and the booster was 6 months; afterwards, with the emergence of new evidence, it was shortened to 4 months.35 Following the comorbidity-prioritised and age-progressive COVID-19 vaccination campaign, the program continued in a staggered manner, in 10-year age decrements, until covering the entire population.

In this study, only individuals aged >50 were considered, as they were prioritised for vaccination in the guidelines proposed by the National Ministry of Health due to the increased risk of severe disease and mortality demonstrated in this age group.36,37 For study purposes, eligible individuals were those who had received a 2-dose vaccination scheme and should have received their booster dose at 120 days or after, but had not—for any reason. They constituted the reference group. Individuals ineligible for boosters were those who had received a 2-dose scheme with the last dose administered up to 119 days before the test.

The booster was considered homologous when the platform was similar to the primary scheme administered—i.e. vectored-based, mRNA or inactivated virus, and heterologous when the platform was different. A primary scheme was considered heterologous when it included two vaccines of different platforms. Any booster administered to a primary heterologous scheme was considered heterologous.

The analysis of the time since vaccine administration was stratified in two periods of <60 and ≥60 days, taking into consideration the reported increase in COVID-19 vaccine protection after administration, waning over time.16,20

The COVID-19 vaccine uptake in the Province of Buenos Aires in adults aged ≥50 and the epidemiological characteristics are shown in the Supplementary Material (Supplementary Figures S1 and S2).

Outcomes

The main outcome was the odds ratio of SARS-CoV-2 infection, COVID-associated hospitalisations and COVID-associated deaths after administering a booster in comparison to a 2-dose primary scheme, occurring ≥14 days after having received the booster dose. The secondary outcome was the odds of experiencing infections, COVID-associated hospitalisations and COVID-associated deaths related to the administration of homologous vs. heterologous boosters, administered after different primary vaccination schemes.

Statistical analyses

Data are expressed in tables as mean ± standard deviations, median with 0.25 and 0.75 percentiles or numbers and percentages, as appropriate. T tests, Chi-square tests, Kruskal–Wallis and Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney tests were used, according to the nature of the variables. A p value < 0.05 was considered significant.

We defined each group based on the primary vaccine scheme and type of booster. Using a matching process, we selected our controls from those individuals who received two doses. Categorical variables were directly matched by aligning the values of each variable. For continuous variables, we established ranges to enable ‘approximate’ matching. The matching process for the test negative case design was performed without replacement using the nearest neighbour (1nn) matching methodology, utilising a logistic regression propensity score within groups defined by exact coincidence on the number of all positive tests in the past (from the beginning of the pandemic to 90 days before the vaccination date) sex, site of residence (Greater Buenos Aires or not), and presence or absence of comorbidities. Additionally, we matched the total number of previous tests on three levels (0, 1–2 or 3+) as a proxy of differences in exposure. The non-exact variables considered were age at diagnosis and date of testing, with maximum tolerance of ±2 years for the age and ±6 days for the date of testing. Up to five controls per case were selected. For each outcome, cases are those with the outcome, and matched controls are selected from among all individuals who tested negative throughout the study period. Furthermore, each control could be included in more than one analysis.38

Subsequently, for each matched set, we utilised a conditional univariate logistic regression model to estimate the odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) for the outcome for each of the groups in the vaccination status variable. This variable had four levels. The reference group were those individuals with two doses who were eligible for receiving a booster dose. The other groups included individuals with two doses ineligible for boosting, as defined previously; those with three doses (third being the booster dose), the last received 15–59 days before the test; and those with three doses (third being the booster dose), the last received 60 or more days before the test.

The following comparisons were performed:

-

(i)

2- vs 3-dose vaccination schemes.

-

(ii)

Homologous booster vs heterologous booster < and ≥60 days for infections, COVID-associated hospitalisations and COVID-associated deaths.

-

(iii)

Sinopharm, Sputnik V, ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 plus mRNA and viral vectored boosters, evaluated at < and ≥60 days for infection, COVID-associated hospitalisations and COVID-associated deaths.

Vaccine effectiveness (VE) was calculated as (1-OR) x 100. Differences in OR for infections, COVID-associated hospitalisations and COVID-associated deaths between homologous vs heterologous boosters received < and ≥60 days; and between selected vaccination schemes were evaluated statistically with pairwise comparisons. For comparison of VE between schemes, the overlapping of the estimated 95% CIs was examined. Additionally, assuming normal distribution of the natural logarithm (ln) of the OR, t-tests for the difference between ORs were conducted. p values were adjusted for multiple comparisons with the Bonferroni method.

Sensitivity analysis

We repeated this analysis stratifying the data according to two-age levels (under or over 65 years old), sex, and presence or absence of comorbidities. This was done to assess whether the effect of vaccine status differs between subgroups. To evaluate the effect of the time cut-off-based subgrouping in the waning analysis, models for infection, COVID-associated hospitalisations and COVID-associated deaths were run considering different time cut-offs. Differences observed in the ORs in infections, COVID-associated hospitalisations and COVID-associated deaths obtained were not statistically significant (p > 0.05, 95% CI) considering a tolerance of ±10 days from the cut-off selected for the main analysis (60 days). To assess the uncertainty associated with the sampling, the matching process was repeated one hundred times for hospitalisation and death analysis. Thus, one hundred ORs were computed for each analysis. In both cases, as obtained ORs were within the limits of the confidence intervals reported in the main analysis for the abovementioned outcomes, it is possible to conclude that our main result is not significantly different to the result of any of these repetitions.

Data preprocessing was carried out with PostgreSQL (Portions Copyright © 1996–2022, The PostgreSQL Global Development Group). All statistical analyses were performed with R (R Development Core Team, 4.2.1 version) software.

Missing values were not imputed.

Ethics

The Central Ethics Committee of the Ministry of Health of the Province of Buenos Aires evaluated and approved the protocol of the present study on 21 September 2022. The report number is 2022-31701807-GDEBA-CECMSALGP.

No patients or members of the public were directly involved in the development or completion of this study.

Informed Consent

This study was exempted of informed consent due to its retrospective nature, and given it is a public health-related official program.

Anonymisation of data

Data were anonymized by the following procedure: the personal ID number was used to link the databases of follow-up and of vaccination. After this process, the personal ID number was removed and an ID reference number for each individual was created. This reference number is not associated with any personal information.

Role of the funding sources

This study did not receive any funding.

Results

Description of the study population

During the study period, 422,144 subjects aged ≥50 and who had completed a test for SARS-CoV-2 at least once during the period of 1 January to 1 April 2022 were eligible for the study. Of them, 221,933 (52.5%) individuals had a positive test and 200,211 (47.5%) had a negative test. With respect to their vaccination status, 190,884 (45.2%) had received a 2-dose scheme of SARS-CoV-2 vaccines and 231,260 (54.8%) had received the primary scheme plus a booster dose (3-dose scheme). The flowchart of the study is shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of the study.

The primary series most frequently included were: ChAdOx1/ChAdOx1 (n = 143,721; 34.0%), Sputnik V/Sputnik V (n = 119,441; 28.3%), Sinopharm/Sinopharm (n = 68,251; 16.2%), Sputnik V/Moderna (66,157; 15.7%) and Sputnik V/ChAdOx1 (n = 23,098; 5.5%).

The boosters applied were vectored vaccines (n = 161,619; 38.3%), mRNA (n = 68,850; 16.3%), and other types of booster platforms (n = 791; 0.2%).

The primary schemes utilised with the corresponding boosters administered, stratified by platform, are shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Primary schemes and boosters administered stratified by platform.

Characteristics of the entire group and comparisons between two and 3-dose vaccinated subjects are shown in Table 1. Briefly, compared to the 2-dose subgroup, the 3-dose subgroup was significantly older, had a lower proportion of males, higher proportion of subjects with comorbid conditions, and lower proportions of subjects with previously registered SARS-CoV-2 infections and previous tests performed. Comorbidities: The main comorbidities registered were arterial hypertension, diabetes, asthma and obesity (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the entire group and comparisons between 2- and 3-dose vaccinated subjects.

| Overall | 2 doses | 3 doses | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 422,144 | 190,884 | 231,260 | |

| Age | 62.19 ± 9.82 | 59.67 ± 8.90 | 64.26 ± 10.06 | <0.001 |

| Sex | ||||

| F | 235,304 (55.7) | 103,704 (54.3) | 131,600 (56.9) | <0.001 |

| M | 186,840 (44.3) | 87,180 (45.7) | 99,660 (43.1) | |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| No | 394,125 (93.4) | 179,948 (94.3) | 214,177 (92.6) | <0.001 |

| Yes | 28,019 (6.6) | 10,936 (5.7) | 17,083 (7.4) | |

| Arterial hypertension | ||||

| Yes | 3292 (0.78) | 1145 (0.6) | 2312 (1) | |

| Asthma | ||||

| Yes | 2490 (0.59) | 1088 (0.57) | 1410 (0.61) | |

| Diabetes | ||||

| Yes | 1857 (0.44) | 668 (0.35) | 1295 (0.56) | |

| Obesity | ||||

| Yes | 591 (0.14) | 229 (0.12) | 393 (0.17) | |

| Others | ||||

| Yes | 19,789 (4.68) | 7806 (4.09) | 11,673 (5.05) | |

| Greater Buenos Aires | ||||

| No | 127,579 (30.2) | 54,059 (28.3) | 73,520 (31.8) | <0.001 |

| Yes | 294,565 (69.8) | 136,825 (71.7) | 157,740 (68.2) | |

| Previous positive SARS-CoV-2 tests | ||||

| 0 | 367,309 (87.0) | 164,285 (86.1) | 203,024 (87.8) | <0.001 |

| 1 | 53,244 (12.6) | 25,814 (13.5) | 27,430 (11.9) | |

| 2 | 1535 (0.4) | 759 (0.4) | 776 (0.3) | |

| 3 | 52 (0.0) | 25 (0.0) | 27 (0.0) | |

| 4 | 4 (0.0) | 1 (0.0) | 3 (0.0) | |

| Previous total SARS-CoV-2 tests | ||||

| 0 | 244,772 (58.0) | 110,179 (57.7) | 134,593 (58.2) | <0.001 |

| 1–2 | 158,275 (37.5) | 72,384 (37.9) | 85,891 (37.1) | |

| 3+ | 19,097 (4.5) | 8321 (4.4) | 10,776 (4.7) | |

| Interval after last dose in days | 96 ± 59 | 149 ± 42 | 52 ± 25 | <0.001 |

| Interval after last dose | ||||

| 15–59 days | 156,438 (37.1) | 4925 (2.6) | 151,513 (65.6) | <0.001 |

| 60–119 days | 101,299 (24.0) | 24,882 (13.0) | 76,417 (33.0) | |

| ≥120 days | 164,407 (38.9) | 161,077 (84.4) | 3330 (1.4) | |

| Events per outcome | ||||

| Infections | 221,933 (52.6) | 119,599 (62.7) | 102,334 (44.3) | <0.001 |

| Hospitalisations | 2178 (0.5) | 1341 (0.7) | 837 (0.4) | <0.001 |

| Deaths | 2209 (0.5) | 1420 (0.7) | 789 (0.3) | <0.001 |

Data are presented as mean ± SD and n (%).

The median time elapsed for the 3-dose scheme since the application of the last dose for the <60 and ≥60 days subgroups was 36 (26–48) and 75 (66–89) days, respectively. The median time elapsed for the 2-dose scheme since the application of the last dose for the <120 and ≥ 120 days subgroups was 48 (31–66) and 127 (123–132) days, respectively.

Of the 221,933 cases of confirmed infections, 119,599 were in the 2-dose subgroup and 102,334 in the 3-dose (62.7% vs 44.3%; p < 0.001) (Table 1). Two-thousand one hundred and seventy-eight individuals were hospitalised (0.5%); 1341 in the 2-dose subgroup and 837 in the 3-dose subgroup (0.7% vs 0.4%; p < 0.001). A total of 2209 (0.5%) COVID-associated deaths were registered; 1420 in the 2-dose subgroup and 789 in the 3-dose subgroup (0.7% vs 0.3%, p < 0.001).

Matched analysis for the entire population

The matched analysis included 127,014 cases and 180,714 controls; the characteristics of the matched groups are shown in Supplementary Table S3, and the number of the infections, COVID-associated hospitalisations and COVID-associated deaths are shown in Table 2. Regarding infections, the booster dose decreased the OR after 14–59 days of administration (OR 0.81 [0.80–0.83]); after 60 days, protection dropped back to levels similar to the 2-dose scheme. The booster dose also decreased the risk of COVID-associated hospitalisations and COVID-associated deaths after 14–59 days (OR 0.28 [0.25–0.32] and 0.25 [0.22–0.28] respectively), and this protective effect persisted after administration for a median of 75 days (66–89) (Table 2). These trends were also evident when subgroups of individuals with or without comorbidities, of both sexes, or older than 65 years were analysed (Table 3 and Supplementary Figure S3, a–f).

Table 2.

Odds ratio against COVID-associated infections, hospitalisations and deaths, stratified by vaccination status.

| Outcome | Vaccination status | SARS-CoV-2 positive cases | SARS-CoV-2 negative controls | Matched SARS-CoV-2 positive cases | Matched SARS-CoV-2 negative controls | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | VE (%) | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Infection | Total | 221,933 | 200,211 | 127,014 | 180,714 | ||||

| 2 doses ineligible | 18,820 | 10,987 | 9413 | 10,531 | 0.97 | 0.94–1.00 | 3 | 0 to 6 | |

| 2 doses eligible | 100,779 | 60,298 | 51,748 | 57,301 | 1 (ref) | ||||

| 3 doses <60 days | 74,777 | 76,736 | 45,933 | 72,777 | 0.81 | 0.80–0.83 | 19 | 17 to 20 | |

| 3 doses ≥60 days | 27,557 | 52,190 | 19,920 | 40,105 | 1.04 | 1.01–1.06 | −4 | −6 to −1 | |

| Hospitalisations | Total | 2178 | 200,211 | 2149 | 9254 | ||||

| 2 doses ineligible | 136 | 10,987 | 136 | 356 | 1.08 | 0.87–1.35 | −8 | −35 to 13 | |

| 2 doses eligible | 1205 | 60,298 | 1192 | 3044 | 1 (ref) | ||||

| 3 doses <60 days | 546 | 76,736 | 533 | 4483 | 0.28 | 0.25–0.32 | 72 | 68 to 75 | |

| 3 doses ≥60 days | 291 | 52,190 | 288 | 1371 | 0.52 | 0.44–0.61 | 48 | 39 to 56 | |

| Death | Total | 2209 | 200,211 | 2196 | 10,023 | ||||

| 2 doses ineligible | 136 | 10,987 | 135 | 329 | 1.09 | 0.88–1.35 | −9 | −35 to 12 | |

| 2 doses eligible | 1284 | 60,298 | 1275 | 3188 | 1 (ref) | ||||

| 3 doses <60 days | 538 | 76,736 | 537 | 5054 | 0.25 | 0.22–0.28 | 75 | 72 to 78 | |

| 3 doses ≥60 days | 251 | 52,190 | 249 | 1452 | 0.38 | 0.33–0.45 | 62 | 55 to 67 |

Table 3.

Odds ratio of booster against confirmed COVID-associated infections, hospitalisations and death by subgroup.

| Subgroup | Vaccination status | Outcome | Matched SARS-CoV-2 positive casesa | Matched SARS-CoV-2 negative controlsa | Odds ratio | CILow | CIHigh | VE (%) | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 50–65 years old | 2 doses elegible | Infections | 38,382 | 41,196 | 1.00 | Ref | Ref | ||

| 2 doses ineligible | 7891 | 8673 | 0.96 | 0.93 | 1.00 | 4 | 0 to 6 | ||

| 3 doses <60 days | 24,276 | 42,408 | 0.75 | 0.74 | 0.77 | 25 | 23 to 26 | ||

| 3 doses ≥60 days | 11,433 | 21,943 | 1.02 | 0.99 | 1.05 | −2 | −5 to 1 | ||

| 2 doses elegible | Hospitalisations | 240 | 865 | 1.00 | Ref | Ref | |||

| 2 doses ineligible | 48 | 159 | 1.10 | 0.77 | 1.58 | −10 | −58 to 23 | ||

| 3 doses <60 days | 69 | 798 | 0.29 | 0.21 | 0.39 | 71 | 61 to 79 | ||

| 3 doses ≥60 days | 73 | 286 | 0.85 | 0.62 | 1.18 | 15 | −18 to 38 | ||

| 2 doses elegible | Death | 169 | 577 | 1.00 | Ref | Ref | |||

| 2 doses ineligible | 38 | 95 | 1.37 | 0.90 | 2.07 | −37 | −107 to 10 | ||

| 3 doses <60 days | 43 | 553 | 0.24 | 0.17 | 0.35 | 76 | 65 to 83 | ||

| 3 doses ≥60 days | 35 | 182 | 0.56 | 0.37 | 0.85 | 44 | 15 to 63 | ||

| 65+ years old | 2 doses elegible | Infections | 13,164 | 15,931 | 1.00 | Ref | Ref | ||

| 2 doses ineligible | 1503 | 1852 | 0.99 | 0.92 | 1.07 | 1 | −7 to 8 | ||

| 3 doses <60 days | 21,556 | 30,120 | 0.93 | 0.90 | 0.96 | 7 | 4 to 10 | ||

| 3 doses ≥60 days | 8476 | 17,808 | 1.11 | 1.07 | 1.16 | −11 | −16 to −7 | ||

| 2 doses elegible | Hospitalisations | 942 | 2117 | 1.00 | Ref | Ref | |||

| 2 doses ineligible | 86 | 198 | 1.03 | 0.78 | 1.36 | −3 | −36 to 22 | ||

| 3 doses <60 days | 464 | 3594 | 0.27 | 0.24 | 0.31 | 73 | 69 to 76 | ||

| 3 doses ≥60 days | 212 | 1075 | 0.42 | 0.35 | 0.51 | 58 | 49 to 65 | ||

| 2 doses elegible | Death | 1097 | 2582 | 1.00 | Ref | Ref | |||

| 2 doses ineligible | 97 | 241 | 0.93 | 0.72 | 1.20 | 7 | −20 to 28 | ||

| 3 doses <60 days | 490 | 4381 | 0.25 | 0.22 | 0.28 | 75 | 72 to 78 | ||

| 3 doses ≥60 days | 213 | 1249 | 0.36 | 0.30 | 0.44 | 64 | 56 to 70 | ||

| Female | 2 doses elegible | Infections | 29,469 | 32,322 | 1.00 | Ref | Ref | ||

| 2 doses ineligible | 5466 | 5887 | 1.00 | 0.96 | 1.04 | 0 | −4 to 4 | ||

| 3 doses <60 days | 27,089 | 41,803 | 0.81 | 0.79 | 0.83 | 19 | 17 to 21 | ||

| 3 doses ≥60 days | 11,776 | 22,818 | 1.06 | 1.02 | 1.09 | −6 | −9 to −2 | ||

| 2 doses elegible | Hospitalisations | 555 | 1525 | 1.00 | Ref | Ref | |||

| 2 doses ineligible | 54 | 164 | 1.01 | 0.73 | 1.41 | −1 | −41 to 27 | ||

| 3 doses <60 days | 263 | 2139 | 0.31 | 0.27 | 0.37 | 69 | 63 to 73 | ||

| 3 doses ≥60 days | 128 | 642 | 0.50 | 0.39 | 0.64 | 50 | 36 to 61 | ||

| 2 doses elegible | Death | 615 | 1580 | 1.00 | Ref | Ref | |||

| 2 doses ineligible | 50 | 158 | 0.86 | 0.62 | 1.21 | 14 | −21 to 38 | ||

| 3 doses <60 days | 261 | 2378 | 0.26 | 0.22 | 0.31 | 74 | 69 to 78 | ||

| 3 doses ≥60 days | 101 | 680 | 0.32 | 0.25 | 0.42 | 68 | 58 to 75 | ||

| Male | 2 doses elegible | Infections | 22,299 | 24,991 | 1.00 | Ref | Ref | ||

| 2 doses ineligible | 4054 | 4654 | 0.96 | 0.92 | 1.01 | 4 | −1 to 8 | ||

| 3 doses <60 days | 18,623 | 30,952 | 0.80 | 0.77 | 0.82 | 20 | 18 to 23 | ||

| 3 doses ≥60 days | 8237 | 17,261 | 1.01 | 0.98 | 1.05 | −1 | −5 to 2 | ||

| 2 doses elegible | Hospitalisations | 636 | 1563 | 1.00 | Ref | Ref | |||

| 2 doses ineligible | 82 | 183 | 1.17 | 0.87 | 1.56 | −17 | −56 to 13 | ||

| 3 doses <60 days | 274 | 2294 | 0.26 | 0.22 | 0.31 | 74 | 69 to 78 | ||

| 3 doses ≥60 days | 160 | 747 | 0.51 | 0.41 | 0.64 | 49 | 36 to 59 | ||

| 2 doses elegible | Death | 661 | 1604 | 1.00 | Ref | Ref | |||

| 2 doses ineligible | 85 | 165 | 1.33 | 1.00 | 1.76 | −33 | −76 to 0 | ||

| 3 doses <60 days | 275 | 2675 | 0.24 | 0.20 | 0.28 | 76 | 72 to 80 | ||

| 3 doses ≥60 days | 148 | 779 | 0.43 | 0.35 | 0.54 | 57 | 46 to 65 | ||

| With comorbidities | 2 doses elegible | Infections | 2961 | 3336 | 1.00 | Ref | Ref | ||

| 2 doses ineligible | 420 | 463 | 1.00 | 0.87 | 1.16 | 0 | −16 to 13 | ||

| 3 doses <60 days | 3343 | 4743 | 0.86 | 0.80 | 0.93 | 14 | 7 to 20 | ||

| 3 doses ≥60 days | 1806 | 3077 | 1.15 | 1.05 | 1.26 | −15 | −26 to −5 | ||

| 2 doses elegible | Hospitalisations | 588 | 1341 | 1.00 | Ref | Ref | |||

| 2 doses ineligible | 58 | 150 | 0.96 | 0.69 | 1.33 | 4 | −33 to 31 | ||

| 3 doses <60 days | 285 | 1872 | 0.32 | 0.27 | 0.38 | 68 | 62 to 73 | ||

| 3 doses ≥60 days | 179 | 693 | 0.65 | 0.52 | 0.81 | 35 | 19 to 48 | ||

| 2 doses elegible | Death | 449 | 963 | 1.00 | Ref | Ref | |||

| 2 doses ineligible | 48 | 102 | 1.13 | 0.78 | 1.66 | −13 | −66 to 22 | ||

| 3 doses <60 days | 165 | 1350 | 0.24 | 0.20 | 0.30 | 76 | 70 to 80 | ||

| 3 doses ≥60 days | 77 | 408 | 0.39 | 0.29 | 0.53 | 61 | 47 to 71 | ||

| Without comorbidities | 2 doses elegible | Infections | 48,629 | 53,969 | 1.00 | Ref | Ref | ||

| 2 doses ineligible | 9013 | 10,074 | 0.98 | 0.95 | 1.01 | 2 | −1 to 5 | ||

| 3 doses <60 days | 42,692 | 68,093 | 0.81 | 0.80 | 0.83 | 19 | 17–20 | ||

| 3 doses ≥60 days | 18,244 | 36,992 | 1.04 | 1.01 | 1.07 | −4 | −7 to −1 | ||

| 2 doses elegible | Hospitalisations | 597 | 1760 | 1.00 | Ref | Ref | |||

| 2 doses ineligible | 78 | 198 | 1.22 | 0.91 | 1.63 | −22 | −63 to 9 | ||

| 3 doses <60 days | 255 | 2540 | 0.27 | 0.23 | 0.32 | 73 | 68 to 77 | ||

| 3 doses ≥60 days | 109 | 690 | 0.39 | 0.31 | 0.50 | 61 | 50 to 69 | ||

| 2 doses elegible | Death | 827 | 2286 | 1.00 | Ref | Ref | |||

| 2 doses ineligible | 87 | 230 | 1.04 | 0.80 | 1.36 | −4 | −36 to 20 | ||

| 3 doses <60 days | 369 | 3673 | 0.26 | 0.23 | 0.30 | 75 | 70 to 87 | ||

| 3 doses ≥60 days | 172 | 1006 | 0.42 | 0.34 | 0.51 | 58 | 49 to 66 |

a) Under 65 years, b) Over 65 years, c) Without comorbidities, d) With comorbidities, e) Male, f) Female.

Matching process used the nearest neighbour (1nn) matching. with up to five controls per case, based on age, sex, number of positive tests in the past, site of residence, presence or absence of comorbidities and number of previous tests.

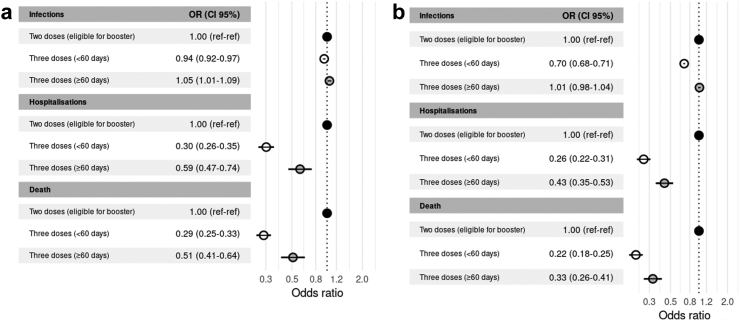

Protection of homologous boosters against infection, COVID-associated hospitalisations and COVID-associated deaths

The primary schemes with ChAdOx1, SputnikV or combined vectored schemes plus a vectored-vaccine booster showed similar trends regarding protection of infections, consisting in a small incremental effect (OR 0.94 [0.92–0.97]), that waned after 60 days (OR 1.05 [1.01–1.09]). These schemes provided a large protection against COVID-associated hospitalisations and COVID-associated deaths (OR 0.30 [0.26–0.35] and OR 0.29 [0.25–0.33], respectively). The effect of all homologous primary courses receiving a booster of a similar platform against COVID-associated hospitalisations and COVID-associated deaths (OR 0.59 [0.47–0.74] and OR 0.51; [0.41–0.64], respectively) waned after 60 days (Fig. 3a–c and Supplementary Table S4).

Fig. 3.

Odds ratios of boosters against confirmed COVID-associated infections, hospitalisations and deaths. a) Homologous boosters. b) Heterologous boosters.

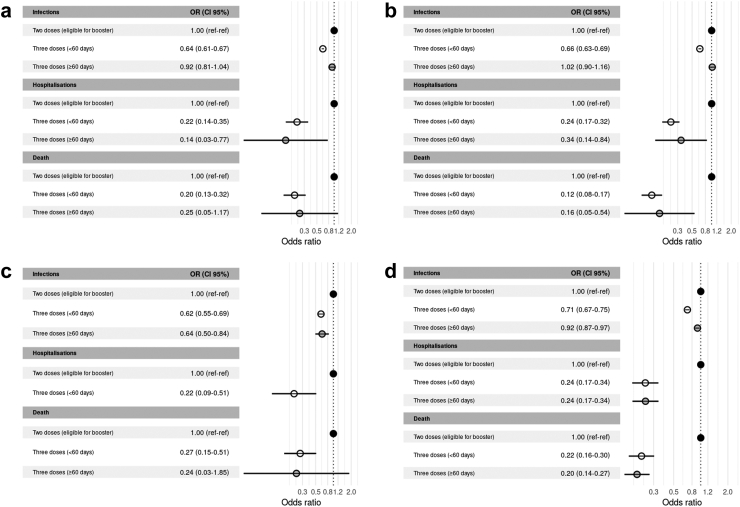

Odds ratio for all subgroups by primary scheme and platform of booster are shown in Fig. 4a–c and Supplementary Table S5.

Fig. 4.

Odds ratio of homologous vectored booster against confirmed COVID-associated infections, hospitalisations and deaths stratified by primary scheme. a) ChAdOx1 b) Sputnik V c) Vectored heterologous primary schemes.

Protection of heterologous boosters against infection, COVID-associated hospitalisations and COVID-associated deaths

The primary courses with ChAdOx1 or Sputnik V plus a mRNA booster, or with Sinopharm plus mRNA or vectored booster afforded additional protection against infections (OR 0.70 [0.68–0.71]), but a waning effect after 60 days was evident (OR 1.01 [0.98–1.04]) (Fig. 3, Supplementary Table S2). Notwithstanding this, there was a clear protective effect against COVID-associated hospitalisations (OR 0.26 [0.22–0.31]) and COVID-associated deaths (OR 0.22 [0.18–0.25]) in all cases, which persisted after 60 days (OR [0.43; 0.35–0.53] and 0.33 [0.26–0.41], respectively). Odds ratios for all subgroups by primary scheme and platform of booster are shown in Fig. 5a–d and Supplementary Table S5.

Fig. 5.

Odds ratio of heterologous boosters against confirmed COVID-associated infections, hospitalisations and deaths stratified by primary scheme and type of booster. a) ChAdOx1 plus mRNA b) Sputnik V plus mRNA c) Sinopharm plus mRNA d) Sinopharm plus vectored vaccine.

After heterologous primary schemes, mRNA boosters conferred greater protection against COVID-associated hospitalisations and COVID-associated deaths when compared with viral vectored boosters (OR [0.09; 0.04–0.24] and OR [0.12; 0.05–0.27], respectively). However, for these viral vector types of boosters the confidence intervals were wide, probably due to the small number of individuals in this category (Fig. 6a–c and Supplementary Table S5).

Fig. 6.

Odds ratio of heterologous boosters against confirmed COVID-associated infections, hospitalisations and deaths stratified by primary scheme and type of booster. a) Vectored heterologous primary schemes plus mRNA booster. b) Vectored-mRNA heterologous primary schemes plus mRNA booster c) Vectored-mRNA heterologous primary schemes plus vectored booster.

Comparison of homologous vs. heterologous boosters

Heterologous boosters applied after different primary vaccination schemes were superior to homologous boosters against infection (p < 0.0001 and p < 0.01, within and after 60 days of application, respectively); COVID-associated hospitalisations (only after ≥60 days of application, p < 0.01); and COVID-associated deaths (p ≤ 0.01 and p ≤ 0.001, within and after 60 days of application, respectively) (Supplementary Table S4).

Comparison between some specific primary schemes with Sinopharm, Sputnik V, ChAdOx1 followed by mRNA boosters.

Within 60 days of application, there were no differences in the occurrence of infections, COVID-associated hospitalisations and COVID-associated deaths between the 3 different above-mentioned schemes evaluated. However, after 60 days, the scheme Sinopharm + mRNA booster was associated to a decreased number of infections than Sputnik V + mRNA booster (p < 0.001), without differences for COVID-associated hospitalisations and COVID-associated deaths (Supplementary Figure S4a–b).

Comparison between some specific primary schemes with Sinopharm, Sputnik V, ChAdOx1 followed by viral vectored boosters.

Within 60 days of application, Sinopharm + any vector booster vaccine was superior against infection compared to SputnikV or ChAdOx1 + any vector booster (p < 0.0001). Against COVID-associated hospitalisations and COVID-associated deaths, however, Sinopharm + any vector booster gave higher protection than SputnikV + any vector booster (p < 0.0001). After 60 days, Sinopharm + any vector booster vaccine was superior against infection, COVID-associated hospitalisations and COVID-associated deaths compared to ChAdOx1 + any vector booster (p < 0.0001 for the 3 events). Sinopharm + any vector booster, when compared to SputnikV + any vector booster, was superior only against COVID-associated deaths (p < 0.001) (Supplementary Figure S4c–d).

Subgroup analysis

Comparison of COVID-associated deaths between 2- and 3-dose schemes after 60 days in patients with 50–65 years and in those older than >65 showed ORs and CIs of 0.56 [0.37–0.85] and 0.36 [0.30–0.44], respectively. For patients with and without comorbidities, ORs were 0.39 [0.29–0.53] and 0.42 [0.34–0.51], respectively. For COVID-associated hospitalisations, the subgroup of 50–65 years had lower protection than the subgroup >65 (OR 0.85 [0.62–1.18] vs 0.42 [0.35–0.51]). Protection against COVID-associated hospitalisations after 60 days of vaccination in patients without and with comorbidities was present (ORs 0.39 [0.31–0.50] vs 0.65 [0.52–0.81], respectively).

ORs for death in males were higher than in females: 0.43 [0.35–0.54] vs. 0.32 [0.25–0.42], respectively; while no difference was observed forCOVID-associated hospitalisations: OR 0.51 [0.41–0.64] vs. 0.50 [0.39–0.64], respectively.

All data about subgroups are shown in Table 3.

Sensitivity analysis

The results of the matching process, which was repeated one hundred times for COVID-associated hospitalisations and COVID-associated deaths are shown in the Supplementary material (Supplementary Figures S5 and S6).

Discussion

We examined the effect of homologous and heterologous boosters applied after different primary vaccination schemes against infection, COVID-associated hospitalisations, and COVID-associated deaths in individuals older than 50 during omicron BA.1 predominance in Argentina. Our main finding was that the administration of a heterologous booster after the primary scheme might produce greater beneficial effects on COVID-associated hospitalisations and COVID-associated deaths, which did not wane at different time points from inoculation, in comparison to homologous boosters. Of note, in our sample, all 3-dose homologous schemes were viral-vectored products. Similar results have been reported in previous studies for other vaccine schemes combinations.9, 10, 11, 12,14,15,17, 18, 19, 20 In addition, this study provides new information on the utilisation of the inactivated vaccine Sinopharm, the viral vector vaccine SputnikV, and heterologous primary schemes, which was previously quite scarce.21

After realising that ChAdOx1 administration was associated with increased risk of thrombosis with thrombocytopenia syndrome, some European Union Member States embarked on a strategy of heterologous primary vaccination during the spring of 2021.39 Similar strategies involving heterologous vaccination in other diseases have been applied in the past.40 In this context, new data has emerged, acknowledging that, in terms of immunological response, the administration of heterologous boosters is as good as, or even better, than homologous boosters.3,7, 8, 9, 10,41 As in vitro studies also support this strategy, the CDC and ECDC recommended the “mix and match” approach.42,43 Considering a global context of primary schemes that do not include mRNA vaccines, taking into consideration that not all countries have access to them, our findings expand on the current knowledge regarding the protection conferred from additional COVID-19 vaccine combinations.

The first studies reporting heterologous boosters in real life originated in the United Kingdom during the pre-omicron period, where Pfizer-BNT administered after a primary scheme of ChAdOx1 had 93% VE against symptomatic disease, compared to the unvaccinated.11 These figures are similar to the 94% VE achieved with a homologous booster after a primary scheme of Pfizer-BNT.12 In Chile, after a Sinovac primary scheme, heterologous boosting with ChAdOx1 or Pfizer-BNT was associated with higher VE than homologous boosting against symptomatic infection (90% for ChAdOx1; 93% for Pfizer-BNT; and 68% for Sinovac), COVID-associated hospitalisations (96%, 89%, and 75%, respectively), and intensive care unit admission (98%, 90%, and 79%, respectively), during the period of delta VOC predominance.12 Both studies show high VE against symptomatic infection, in contrast to our study in which any booster administration produced a low and brief protection against this outcome. These divergent results might be ascribed to omicron's great capacity for immune evasion.

The first study on heterologous boosting after inactivated vaccines in the Omicron era was carried out in Brazil, which reported a VE of 56.8% against symptomatic disease and 86.0% against severe COVID-19 after a primary scheme with an inactivated virus vaccine followed by a Pfizer-BNT booster.13 In our study, the effect of homologous boosting afforded little or no additional protection against confirmed infections, as was documented in Brazil and Singapore after the triple scheme with Sinovac, and in the US and Malaysia where the viral vectored boosters Janssen and ChAdOx1 were administered.11,13, 14, 15, 16,23,44 Conversely, two studies from the UK and Qatar, and a systematic review using triple-mRNA reported acceptable protection against infections, but it waned after 2 or 3 months.6,11,15,18,45 We found that the effect of homologous boosting against COVID-associated hospitalisations and COVID-associated deaths was slightly lower than after the utilisation of heterologous boosting, with a trend towards waning after 60 days—similar to other reports.13, 14, 15,46,47 An exception occurred with the administration of a primary heterologous vectored scheme followed by a vectored booster, which provided significant protection against mortality within 60 days of booster administration.

Concerning the use of heterologous boosters after homologous or heterologous primary schemes against infections, we observed a modest increase in protection that waned after 60 days, similar to the results described by researchers from Brazil, Scotland and the United Kingdom after the application of ChAdOx1 primary schemes followed by mRNA boosters.17,19,20 In contrast, a US study with viral vectored Janssen vaccine and an mRNA booster reported protection against infections up to 160 days.15 We observed, however, high additional protection against death after the administration of a heterologous booster used with homologous primary regimens, which was maintained for a median of 75 (66–88) days. Similar results were reported with heterologous boosting after the administration of primary schemes with the inactivated vaccine Sinovac and the vectored vaccines Janssen and ChAdOx1.15,17,19, 20, 21, 22 In our study, Sinopharm plus any vectored vaccine seemed to provide the best protection against death. Although our results are the first to report protection in a real-life setting, they are in line with in vitro studies; Argentinian researchers found that a heterologous booster with ChAdOx1, Sputnik V, or Pfizer-BNT vaccines markedly increased the neutralising activity against the omicron variant and was maintained up to 90 days in elderly people with primary schemes of Sinopharm.10 Furthermore, researchers from Bahrain and Serbia reported that heterologous boosting with Pfizer-BNT after administering a primary scheme with Sputnik V yielded higher levels of antibodies than homologous boosting.46,47

Boosting with a vectored vaccine after a primary scheme which included an mRNA vaccine resulted in less protection compared with the same boosting after two doses of Sinopharm. By contrast, boosting with mRNA vaccine after a primary vectored vaccine scheme provided remarkable protection. The impact resulting from the order in which vaccine products and platforms in heterologous vaccination are administered has been recognised and is the subject of research, according to the WHO.7

With respect to subgroup analyses, results of COVID-associated deaths and COVID-associated hospitalisations between 2- and 3-dose schemes after 60 days in different age and comorbidities subgroups resulted in some unexpected findings. For example, concerning death, the older group seemed to be more protected than the younger group. Patients with comorbidities had lower ORs; however, CIs 95% overlapped in all cases. Therefore, we cannot clearly state that vaccination with 3-doses against 2, after 60 days, conferred higher protection against COVID-associated deaths in the older and comorbidity subgroups. What is evident is that there are trends towards decreased mortality in these two subgroups. It is possible that, since we are considering relative effectiveness, the higher protection provided by a third dose in the elderly might be due to lower basal protection provided by 2 doses; thus, the relative increase of VE with a third dose in this population might be higher.13

With regard to COVID-associated hospitalisations, we did find that in individuals with 3-dose schemes, the 50-65-year-old subgroup had lower protection than the >65 subgroup. This might be attributed to lower perception of the severity of the disease, secondary to the receipt of the complete 2-dose schemes in this younger subgroup compared to the older. Another possibility is that the younger subgroup receiving 2 doses might have exhibited better results in terms of COVID-associated hospitalisations than the older ones, due to better immunological status and, therefore, delayed waning. Patients without comorbidities exhibited longer protection against COVID-associated hospitalisations after 60 days of vaccination, compared to those with comorbidities. Finally, there was a trend towards more COVID-associated deaths in the male subgroup, as has been reported in the literature.48,49

To our knowledge, ours is the first study carried out in a real world setting in which primary schemes with Sinopharm, Sputnik V or multiple heterologous schemes were applied and then boosted with vaccines from different platforms. Additionally, we evaluated protection against 3 relevant outcomes: infections, COVID-associated hospitalisations and COVID-associated deaths.

Limitations

First, we were only able to assess the effect of the booster up to a median time of 75 days due to the rapid surge and decrease of the omicron BA.1 wave; so, it is possible that VE and waning effects might develop further changes over time. Nevertheless, the amount of time reported here might be sufficient to detect patterns of change.44,45 Second, we could only estimate the OR of a third dose relative to a second dose. The calculation of the absolute OR (comparison with an unvaccinated population) was not possible given that 95% of the population older than 50 had received at least two vaccine doses at the time of the study period.38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50 Third, modification of testing protocols during the study period might have influenced healthcare seeking behaviour. The choice of a test-negative design aims to attenuate this possible bias. Fourth, misclassification cannot be completely discarded since contamination by incidental COVID-19 cases remains possible. For this reason, we only contemplated COVID-associated hospitalisations and COVID-associated deaths occurring within 14 and 28 days from COVID-19 diagnosis, respectively. Fifth, viral genome sequencing was not available for most individuals; therefore, omicron BA.1 predominance periods were based on genomic surveillance data. Sixth, we only included individuals over the age of 50; thus, our findings about VE and waning cannot be generalised to younger populations. Seventh, OR estimates may be biased due to residual confounders, as in any observational study. Eighth, due to the increased burden of data entry to document infections during the short but intense omicron wave, it is possible that underreporting of COVID-associated hospitalisations occurred. This might also have occurred with the report of other variables, like comorbidities. We do not have a clear explanation for the low number of comorbid conditions reported in our population, but it might also be ascribed to the massive number of cases occurring during the Omicron wave. The testing capacity was certainly overwhelmed, precluding a precise report of some variables, since patient forms had to be filled out by healthcare personnel and not by patients themselves-an important point, given that there might be a differential vaccine effectiveness in the subgroup of immunocompromised subjects. Ninth, given the unavailability of mRNA vaccines in Argentina at the beginning of vaccination roll-out, we could not evaluate the performance of homologous 3-dose schemes involving mRNA vaccines. Finally, we did not compare homologous and heterologous schemes directly; ORs and 95% CIs were estimated against a reference group.

Conclusions and areas for further research

This study shows that heterologous boosters, such as viral vectored and mRNA vaccines, following Sputnik V, ChAdOx1, Sinopharm or heterologous schemes as primary series vaccination, might provide better protection and longer effectiveness against death in individuals over 50, compared to homologous boosters during omicron predominance. The scheme of inactivated vaccine followed by a viral vectored booster seemed to be associated with the best protection against death. The implications of our findings might, thus, support the utilisation of different booster strategies to reach durable vaccine protection, especially in populations with primary schemes involving viral vectored or inactivated vaccines. Continuous monitoring of booster effectiveness over longer periods of time, with consideration of possible new SARS-CoV-2 variants, is key to developing the most appropriate COVID-19 vaccination strategies.

Contributors

Soledad González: Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing, Methodology, Conceptualization, Project administration; Santiago Olszevicki: Software, Data curation, Validation, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing, Methodology; Alejandra Gaiano: Conceptualization; Ana Nina Varela Baino: Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing, Methodology, Conceptualization, Project administration; Lorena Regairaz: Conceptualization; Martín Salazar: Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing, Methodology, Project administration, Conceptualization; Santiago Pesci: Conceptualization; Lupe Marín: Conceptualization, data curation; Veronica V. González Martínez: Conceptualization; Teresa Varela: Conceptualization; Leticia Ceriani: Conceptualization; Erika Bartel: Conceptualization; Juan Ignacio Irassar: Software, data curation; Enio Garcia: Conceptualization; Nicolás Kreplak: Conceptualization; Elisa Estenssoro: Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing, Methodology, Project administration, Conceptualization; Franco Marsico: Software, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing, Methodology, Project administration.

Data sharing statement

The confidentiality of the data obtained through the VacunatePBA and National Surveillance System records was guaranteed. The use of the data was exclusively for the purposes of this research, preserving the anonymity of the persons included. Data will be available for researchers who provide a methodologically sound proposal after it is approved. The data that could be shared is Individual participant data that underlie the results reported in this article, after de-identification (text, tables, figures, and appendices). Proposals should be directed to franco.lmarsico@gmail.com; to gain access, data requestors will need to sign a data access agreement.

Declaration of interests

NK, LC, TV, AG and SP declared being involved in the decision-making process of the vaccination campaign in the Province of Buenos Aires, Argentina. All other authors report no competing interests.

Acknowledgements

Funding: This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Footnotes

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lana.2023.100607.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

References

- 1.Cele S., Jackson L., Khoury D.S., et al. Omicron extensively but incompletely escapes Pfizer BNT162b2 neutralization. Nature. 2022;602(7898):654–656. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-04387-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bar-On Y.M., Goldberg Y., Mandel M., et al. Protection of BNT162b2 vaccine booster against Covid-19 in Israel. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:1393–1400. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2114255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Garcia-Beltran W.F., St Denis K.J., Hoelzemer A., et al. mRNA-based COVID-19 vaccine boosters induce neutralizing immunity against SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant. Cell. 2022;185(3):457–466.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.12.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Higdon M.M., Baidya A., Walter K.K., et al. Duration of effectiveness of vaccination against COVID-19 caused by the omicron variant. Lancet Infect Dis. 2022;22(8):1114–1116. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(22)00409-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.González S., Olszevicki S., Salazar M., et al. Effectiveness of the first component of Gam-COVID-Vac (Sputnik V) on reduction of SARS-CoV-2 confirmed infections, hospitalisations and mortality in patients aged 60-79: a retrospective cohort study in Argentina. eClinicalMedicine. 2021;40 doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.101126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.González S., Olszevicki S., Gaiano A., et al. Effectiveness of BBIBP-CorV, BNT162b2 and mRNA-1273 vaccines against hospitalisations among children and adolescents during the Omicron outbreak in Argentina: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Reg Health Am. 2022;13 doi: 10.1016/j.lana.2022.100316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Health Organization . 2021. Interim recommendations for heterologous COVID-19 vaccine schedules.WHO-2019-nCoV-vaccines-SAGE-recommendation-heterologous-schedules-2021.1-eng.pdf Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 8.Atmar R.L., Lyke K.E., Deming M.E., et al. Homologous and heterologous Covid-19 booster vaccinations. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(11):1046–1057. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2116414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tan C.S., Collier A.Y., Yu J., et al. Durability of heterologous and homologous COVID-19 vaccine boosts. Durability of heterologous and homologous COVID-19 vaccine boosts. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(8) doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.26335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rouco S.O., Rodriguez P.E., Miglietta E.A., et al. Heterologous booster response after inactivated virus BBIBP-CorV vaccination in older people. Lancet Infect Dis. 2022;22(8):1118–1119. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(22)00427-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Andrews N., Stowe J., Kirsebom F., et al. Effectiveness of COVID-19 booster vaccines against COVID-19-related symptoms, hospitalization and death in England. Nat Med. 2022;28(4):831–837. doi: 10.1038/s41591-022-01699-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jara A., Undurraga E.A., Zubizarreta J.R., et al. Effectiveness of homologous and heterologous booster doses for an inactivated SARS-CoV-2 vaccine: a large-scale prospective cohort study. Lancet Glob Health. 2022;10(6):e798–e806. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(22)00112-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ranzani O.T., Hitchings M.D.T., de Melo R.L., et al. Effectiveness of an inactivated Covid-19 vaccine with homologous and heterologous boosters against Omicron in Brazil. Nat Commun. 2022;13:5536. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-33169-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tan C.Y., Chiew C.J., Pang D., et al. Vaccine effectiveness against Delta, Omicron BA.1 and BA.2 in a highly vaccinated Asian setting: a test-negative design study. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2022;S1198-743X(22):418–419. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2022.08.002. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Accorsi E.K., Britton A., Shang N., et al. Effectiveness of homologous and heterologous Covid-19 boosters against omicron. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(25):2433–2435. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2203165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Suah J.L., Tng B.H., Tok P.S.K., et al. Real-world effectiveness of homologous and heterologous BNT162b2, CoronaVac, and AZD1222 booster vaccination against Delta and Omicron SARS-CoV-2 infection. Emerg Microb Infect. 2022;11(1):1343–1345. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2022.2072773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.UK Health Security Agency . 2021. COVID-19 vaccine surveillance report–week 35.https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1050721/Vaccine-surveillance-report-week-4.pdf Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chemaitelly H., Ayoub H.H., AlMukdad S. Duration of mRNA vaccine protection against SARS-CoV-2 Omicron BA.1 and BA.2 subvariants in Qatar. Nat Commun. 2022;13(1):3082. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-30895-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cerqueira-Silva T., Shah S.A., Robertson C., et al. Effectiveness of mRNA boosters after homologous primary series with BNT162b2 or ChAdOx1 against symptomatic infection and severe COVID-19 in Brazil and Scotland: a test-negative design case-control study. PLoS Med. 2023;20(1) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1004156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cerqueira-Silva T., de Araujo Oliveira V., Paixão E.S., et al. Duration of protection of CoronaVac plus heterologous BNT162b2 booster in the Omicron period in Brazil. Nat Commun. 2022;13(1):4154. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-31839-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baum U., Poukka E., Leino T., Kilpi T., Nohynek H., Palmu A.A. High vaccine effectiveness against severe COVID-19 in the elderly in Finland before and after the emergence of Omicron. BMC Infect Dis. 2022;22(1):816. doi: 10.1186/s12879-022-07814-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mayr F.B., Talisa V.B., Shaikh O., Yende S., Butt A.A. Effectiveness of homologous or heterologous covid-19 boosters in Veterans. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(14):1375–1377. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2200415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Park S., Gatchalian K.K., Oh H. Association of homologous and heterologous vaccine boosters with SARS-CoV-2 infection in BBIBP-CorV vaccinated healthcare personnel. Cureus. 2022;14(7) doi: 10.7759/cureus.27323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Patalon T., Gazit S., Pitzer V.E., Prunas O., Warren J.L., Weinberger D.M. Odds of testing positive for SARS-CoV-2 following receipt of 3 vs 2 doses of the BNT162b2 mRNA vaccine. JAMA Intern Med. 2022;182:179–184. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2021.7382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dean N.E., Hogan J.W., Schnitzer M.E. Covid-19 vaccine effectiveness and the test-negative design. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(15):1431–1433. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe2113151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.British society for immunology. 2022. https://www.immunology.org/public-information/vaccine-resources/covid-19/guide-vaccinations-covid-19 Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 27.Argentinian Ministry of Health Genomic surveillance report. 2022. https://www.argentina.gob.ar/coronavirus/informes-diarios/vigilancia-genomica Available from:

- 28.Argentinian Ministry of Health . 2022. Comprehensive surveillance and control strategy for COVID-19 and other acute respiratory infections.https://www.argentina.gob.ar/salud/coronavirus/vigilancia Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 29.Government of the Province of Buenos Aires Plan provincial público, gratuito y optativo contra COVID-19. https://vacunatepba.gba.gob.ar Available from:

- 30.Argentinian Ministry of Health . 2021. Recomendaciones sobre esquemas heterólogos de vacunación COVID-19.https://bancos.salud.gob.ar/sites/default/files/2021-08/recomendacion-sobre-esquemas-heterologos-de-vacunacion-contra-COVID19.pdf Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 31.Argentinian Ministry of Health . 2021. Lineamientos Técnicos: resumen de recomendaciones vigentes para la Campaña Nacional de Vacunación contra la COVID-19.https://bancos.salud.gob.ar/recurso/lineamientos-tecnicos-resumen-de-recomendaciones-vigentes-para-la-campana-nacional-de-0 Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 32.Argentinian Ministry of Health . 2021. Priorización de primera dosis de vacuna contra COVID-19. Available from: https://bancos%a2salud%a2gob%a2ar/recurso/priorizacion-deprimera-dosis-de-vacuna-contra-covid-19. [Google Scholar]

- 33.World Health Organization-WHO . 2021. Interim recommendations for use of the inactivated COVID-19 vaccine BIBP developed by China National Biotec Group (CNBG), Sinopharm.https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/352470/WHO-2019-nCoV-vaccines-SAGE-recommendation-BIBP-2022.1-eng.pdf Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 34.Argentinian Ministry of Health . 2021. Dosis adicional al esquema primario y dosis de refuerzo (booster)https://bancos.salud.gob.ar/recurso/lineamientos-tecnicos-dosis-adicional-al-esquema-primario-y-dosis-de-refuerzo-booster-10-de Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 35.Argentinian Ministry of Health Recomendación de intervalo para la aplicación de la dosis de refuerzo de vacunas contra COVID-19. https://bancos.salud.gob.ar/recurso/memorandum-recomendacion-de-intervalo-para-la-aplicacion-de-la-dosis-de-refuerzo-de-vacunas Available from:

- 36.O'Driscoll M., Ribeiro Dos Santos G., Wang L., et al. Age-specific mortality and immunity patterns of SARS-CoV-2. Nature. 2021;590(7844):140–145. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2918-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Williamson E.J., Walker A.J., Bhaskaran K., et al. Factors associated with COVID-19-related death using OpenSAFELY. Nature. 2020;584(7821):430–436. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2521-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gazit S., Saciuk Y., Perez G., Peretz A., Pitzer V.E., Patalon T. Short term, relative effectiveness of four doses versus three doses of BNT162b2 vaccine in people aged 60 years and older in Israel: retrospective, test negative, case-control study. BMJ. 2022;377 doi: 10.1136/bmj-2022-071113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.European Medicines Agency . 2021. COVID-19 Vaccine Janssen: EMA finds possible link to very rare cases of unusual blood clots with low blood platelets.https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/news/covid-19-vaccine-janssen-ema-finds-possible-link-very-rare-cases-unusual-blood-clots-low-blood Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kardani K., Bolhassani A., Shahbazi S. Prime-boost vaccine strategy against viral infections: mechanisms and benefits. Vaccine. 2016;34(4):413–423. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.11.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Costa Clemens S.A., Weckx L., Clemens R., et al. Heterologous versus homologous COVID-19 booster vaccination in previous recipients of two doses of CoronaVac COVID-19 vaccine in Brazil (RHH-001): a phase 4, non-inferiority, single blind, randomised study. Lancet. 2022;399:521–529. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00094-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.U.S Food and Drug Administration . 2021. Coronavirus (COVID-19) update: FDA takes additional actions on the use of a booster dose for COVID-19 vaccines.https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/coronavirus-covid-19-update-fda-takes-additional-actions-use-booster-dose-covid-19-vaccines Available from: CDC mix match. [Google Scholar]

- 43.European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control EMA and ECDC recommendations on heterologous vaccination courses against COVID-19. https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/news-events/ema-and-ecdc-recommendations-heterologous-vaccination-courses-against-covid-19 Available from:

- 44.Ng O.T., Marimuthu K., Lim N., et al. Analysis of COVID-19 incidence and severity among adults vaccinated with 2-dose mRNA COVID-19 or inactivated SARS-CoV-2 vaccines with and without boosters in Singapore. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(8) doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.28900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kirsebom F., Andrews N., Sachdeva R., Stowe J., Ramsay M., Lopez Bernal J. Effectiveness of ChAdOx1-S COVID-19 booster vaccination against the omicron and delta variants in England. Nat Commun. 2022;13(1):7688. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-35168-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stosic M., Milic M., Markovic M., et al. Immunogenicity and reactogenicity of the booster dose of COVID-19 vaccines and related factors: a panel study from the general population in Serbia. Vaccines (Basel) 2022;10(6):838. doi: 10.3390/vaccines10060838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.AlMadhi M., AlAwadhi A., Stevenson N., et al. Comparing the Safety and Immunogenicity of homologous (Sputnik V) and heterologous (BNT162B2) COVID-19 prime-boost vaccination. medRxiv. 2022 doi: 10.1101/2022.08.24.22279160. [Preprint] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jin J.M., Bai P., He W., et al. Gender differences in patients with COVID-19: focus on severity and mortality. Front Public Health. 2020;29(8):152. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.00152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Flanagan K.L., Fink A.L., Plebanski M., Klein S.L. Sex and gender differences in the outcomes of vaccination over the life course. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2017;33(1):577–599. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-100616-060718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Grewal R., Kitchen S.A., Nguyen L., et al. Effectiveness of a fourth dose of covid-19 mRNA vaccine against the omicron variant among long term care residents in Ontario, Canada: test negative design study. BMJ. 2022;378 doi: 10.1136/bmj-2022-071502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.