Abstract

Effective vaccines are needed to combat diarrheal diseases due to Shigella. Two live oral S. sonnei vaccine candidates, WRSs2 and WRSs3, attenuated principally by the lack of spreading ability, as well as the loss of enterotoxin and acyl transferase genes, were tested for safety and immunogenicity.

Healthy adults 18–45 years of age, assigned to 5 cohorts of 18 subjects each (WRSs2 (n = 8), WRSs3 (n = 8) or placebo (n = 2)) were housed in an inpatient facility and administered a single oral dose of study agent 5 min after ingestion of oral bicarbonate. Ascending dosages of vaccine (from 103 CFU to 107 CFU) were evaluated. On day 8, treatment with ciprofloxacin (500 mg BID for 3 days) was initiated and subjects were discharged home 2 days after completing antibiotics. Subjects returned for outpatient visits on day 14, 28 and 56 post-vaccination for monitoring and collection of stool and blood samples.

Both WRSs2 and WRSs3 were generally well tolerated and safe over the entire dose range. Among the 80 vaccinees, 11 subjects developed diarrhea, 8 of which were mild and did not affect daily activities. At the 107 CFU dose, moderate diarrhea occurred in one WRSs2 subject while at the same dose of WRSs3, 2 subjects had moderate or severe diarrhea. Vaccinees mounted dose-dependent mucosal and systemic immune responses that appeared to correlate with fecal shedding.

S. sonnei vaccine candidates WRSs2 and WRSs3 are safe and immunogenic over a wide dose range. Future steps will be to select the most promising candidate and move to human challenge models for efficacy of the vaccine.

Keywords: Phase I study, Shigella sonnei, Live vaccines, WRSs2/3

1. Introduction

Shigella species, comprised of 4 major serogroups, S. dysenteriae, S. flexneri, S. boydii, and S. sonnei, are estimated to cause over 164,000 deaths annually with 55,000 among children <5 years of age, which represents 11% of all global diarrhea deaths [1]. While Shigella typically is a self-limiting infection, due to low infectious dose, efficiency of transmission and infection associated sequalae, antibiotics often are prescribed to treat the infection. However, multidrug resistance among Shigella is common and increasing in frequency [2]. Therefore, efforts have been focused on development of vaccines to prevent the infection.

A first generation oral, live, attenuated S. sonnei vaccine candidate, WRSS1, was constructed by deleting virulence-plasmid encoded VirG(IcsA) [3]. Phase 1 trial of WRSS1 showed that dose of 104 CFU was safe and immunogenic, but higher doses were associated with diarrhea and fever in over 12% of the recipients [4,5]. To widen the window of safety, while retaining immunogenicity, two second-generation VirG(IcsA)-based oral live vaccine candidates, WRSs2 and WRSs3 were constructed. Animal studies demonstrated that WRSs2 and WRSs3 compared favorably with the safety, immunogenicity and efficacy of WRSS1 with less reactogenicity [6–8]. The current study was conducted to determine whether one or both vaccine candidates strikes the right balance between reactogenicity and immunogenicity and provides a wider window of safety for VirG(IcsA)-deletion-based live vaccines.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Vaccine candidates

WRSs2 and WRSs3 vaccine candidates were derived from the S. sonnei strain, Moseley, [3,4,7]. Both candidates were manufactured under cGMP at the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research (WRAIR) Pilot Bioproduction Facility. Each vial of WRSs2 (lot #1501) and WRSs3 (lot #1486) contained 9.6 × 108 CFU and 1.6 × 109 CFU, respectively, formulated in 2 mL of phosphate buffer saline containing 7.5% dextran T10, 2% sucrose and 1.5% glycerol and then lyophilized. Since manufacture, the stability of the vaccine candidates remain unchanged with >90% Form I phenotype for both WRSs2 and WRSs3 candidates. The vaccines were shipped on dry ice with a temperature monitor to Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center (CCHMC) and stored at −80 °C ± 10 °C until used.

2.2. Study subjects and study design

Following extensive screening, healthy adults (18–45 years) were enrolled after informed consent. The eligibility criterion included no abnormal lab tests, negative for HLA-B27 and an anti-S. sonnei LPS serum IgG ELISA titer of <1:2500 (for detailed eligibility criteria see https://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT01336699). The study was conducted as a double-blind dose-escalation (103–107 CFU, sequential 10-fold increases) trial with five cohorts of 18 subjects randomly assigned to receive a single oral dose of WRSs2 (n = 8), WRSs3 (n = 8) or placebo (n = 2). Subjects were admitted to the inpatient unit the day prior to receipt of the study agent and remained in the inpatient unit for 10 days or after having 2 stool cultures negative for Shigella, whichever was longer. Subjects were administered ciprofloxacin (500 mg twice daily for 3 days) beginning on day 8 Outpatient visits occurred on days 14 ± 1, 28 ± 2 and 56 ± 4 and a final phone call on day 180 ± 14 after vaccination.

The primary objective of the study was to evaluate the safety and tolerability of each candidate with secondary objectives to assess the fecal shedding of the vaccine strain and immune responses in blood and stool.

2.3. Vaccine administration

On the day of vaccination, two vials of each of the vaccine candidates were thawed on ice and immediately reconstituted in 2 mL of ice cold sterile water. After combining the contents of the vials, additional dilutions were made in ice cold saline to the desired concentrations. The vaccine was administered within 2 h of reconstitution. At the time of vaccine administration, an aliquot was removed to determine by culture the actual dose administered.

Subjects fasted for 90 min prior to and after receiving the study product. Subjects ingested 150 mL of sodium bicarbonate (2 gm in 150 mL of sterile water) followed within 5 min by the 30 mL of saline containing 1 mL vaccine suspension.

2.4. Clinical assessment

During the inpatient period, subjects were evaluated at least twice daily to capture reactogenicity (Table 1). All signs and symptoms were graded as mild, moderate or severe based on the impact of the symptoms on the daily activities of the subject. Clinical signs and abnormal laboratory values were graded based on predefined criteria. Serious adverse events (SAEs) were recorded through day 180 post-vaccination.

Table 1.

Maximum severity of solicited adverse events.

| Vaccine and vaccine dosea | Diarrhea |

Fever | Headache | Cramps | Vomiting | Myalgia | Arthralgia | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mild | Mod-Severe | Any | Any | Any | Any | Any | Any | ||

|

| |||||||||

| 103 | WRSs2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| WRSs3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 104 | WRSs2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| WRSs3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 105 | WRSs2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| WRSs3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| 106 | WRSs2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| WRSs3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 107 | WRSs2 | 2 | 1b | 1 (38.4 °C max) | 4 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| WRSs3 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| Placebo | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

n = 8 for each vaccine and dose, n = 9 for placebo.

Subject had 4 loose stools over 24 h with a total weight of 178 gm with one of the stools being 0.2 gm in weight.

Diarrhea was defined as per 24 h period; mild if the subject had 2–3 loose or watery stools with <400 gm/loose stools, moderate if the subject had 4–5 loose or watery stools or 400–800 g/loose stools and severe if ≥6 loose or watery stools or >800 gm/loose stools in 24 h. Dysentery was defined as two or more diarrheal stools with gross blood and mucous and reportable constitutional symptoms. Shigellosis was defined as shedding of S. sonnei in the stool accompanied by moderate-severe diarrhea and/or dysentery along with moderate fever or one or more severe intestinal symptoms. Dehydration was defined as a negative fluid balance associated with any of the following symptoms: syncope or near syncope, orthostatic hypotension, urine specific gravity >1.030, or no urine output within an 8-hour period.

A Safety Monitoring Committee reviewed all safety data collected through Day 28 and provided recommendation for the subsequent cohort. Halting rules included 2 or more subjects in a single dosage cohort experiencing the same ≥3 grade severe event, or 3 subjects developing the same severe event across dosage groups for WRSs2 or WRSs3, in the 15 days after vaccination.

2.5. Sample collection

2.5.1. Blood

Blood was collected before vaccination and on days 7, 14, 28 and 56 post-vaccination for whole blood count, renal and liver function tests as well as measurement of Shigella antigen-specific serum IgA and IgG. Blood for enumerating antibody secreting cells (ASCs) was collected before vaccination and on days 5, 7 and 9 post-vaccination. Sera for immunological testing were stored at −20 °C until assayed.

2.5.2. Stool

All stools were assessed for consistency and presence of visible blood which was confirmed by stool guaiac testing. Every loose or watery stool was weighed, recorded and graded. At least one stool per day for each subject was cultured for Shigella. Aliquots of each stool were stored frozen either directly for fecal IgA determination or in modified buffered glycerol saline (BGS) to quantify the magnitude of vaccine shedding.

2.6. Specimen testing

2.6.1. Stool culture

A presumptive detection of Shigella was made by testing up to two blue-green colonies isolated from freshly plated stool for agglutination using S. sonnei polyvalent Group D antiserum (Denke-Seiken). For stools from which Shigella presumptively was detected, aliquots were suspended in BGS and stored at −70 °C pending definitive identification and quantification. Frozen stools were thawed and serial dilutions of stool were streaked on Hektoen Enteric Agar (HEA) plates and immunoblotted with monoclonal antibody MAb 2F1 to IpaB [9] with the number of positive colonies used to calculate the colonies of Shigella per gram of stool. Subjects with stool samples that were colony immunoblot positive were defined as shedders.

2.7. Assessment of immune responses

2.7.1. Antigens

Shigella antigens used for the immunoassays included Invaplex50 (IVP) (a water extract complex of S. sonnei LPS, IpaB and IpaC), purified S. sonnei LPS, and purified invasion plasmid antigen (Ipa) B [10–12].

2.7.2. Serum immune responses

Determination of endpoint titers specific for Shigella antigens was performed by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) as previously described [10,13]. The endpoint titer was defined as the reciprocal of the highest dilution of a given sample that produced an OD value of ≥0.2. An IgA/IgG seroresponse was defined as a ≥4-fold rise in reciprocal endpoint titers over the baseline.

2.7.3. Antibody secreting cells

Blood was collected in EDTA tubes and mononuclear cells (PBMC) were isolated, cryopreserved and stored in liquid nitrogen for ASC assays [10,14]. A responder was defined as having ≥10 ASCs per 106 PBMCs.

2.7.4. Fecal IgA

Frozen stool samples were thawed and suspended in an extraction buffer containing a soybean trypsin inhibitor-EDTA and the resulting supernatants were used to determine total and antigen-specific IgA by ELISA [15,16]. Endpoint titers were calculated as the reciprocal of the highest dilution and adjusted to 1000 μg/mL of total IgA.

2.8. Statistical analysis

This Phase 1 study was not powered to detect statistical significance between the two vaccine candidates, therefore the analyses focused on descriptive techniques to estimate rates, means, and confidence intervals. With a sample size of 40 subjects per vaccine group, there is only a 33% likelihood of detecting an event with an actual frequency of 1%. The comparisons were made by computing estimates and confidence intervals of appropriate outcomes. The immunogenicity data were log transformed to satisfy asymptotic normality conditions to compute the mean. Mean values were converted back to arithmetic scale to expressed as geometric mean values (GMTs). All data analyses and statistical computations were conducted with SAS software, version 9.3 or higher (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

2.9. Ethical review

The study was reviewed and approved by the CCHMC IRB and conducted to the standards of ICH-GCP E6, under a US Food and Drug Administration approved IND.

3. Results

3.1. Subject enrollment and vaccine administration:

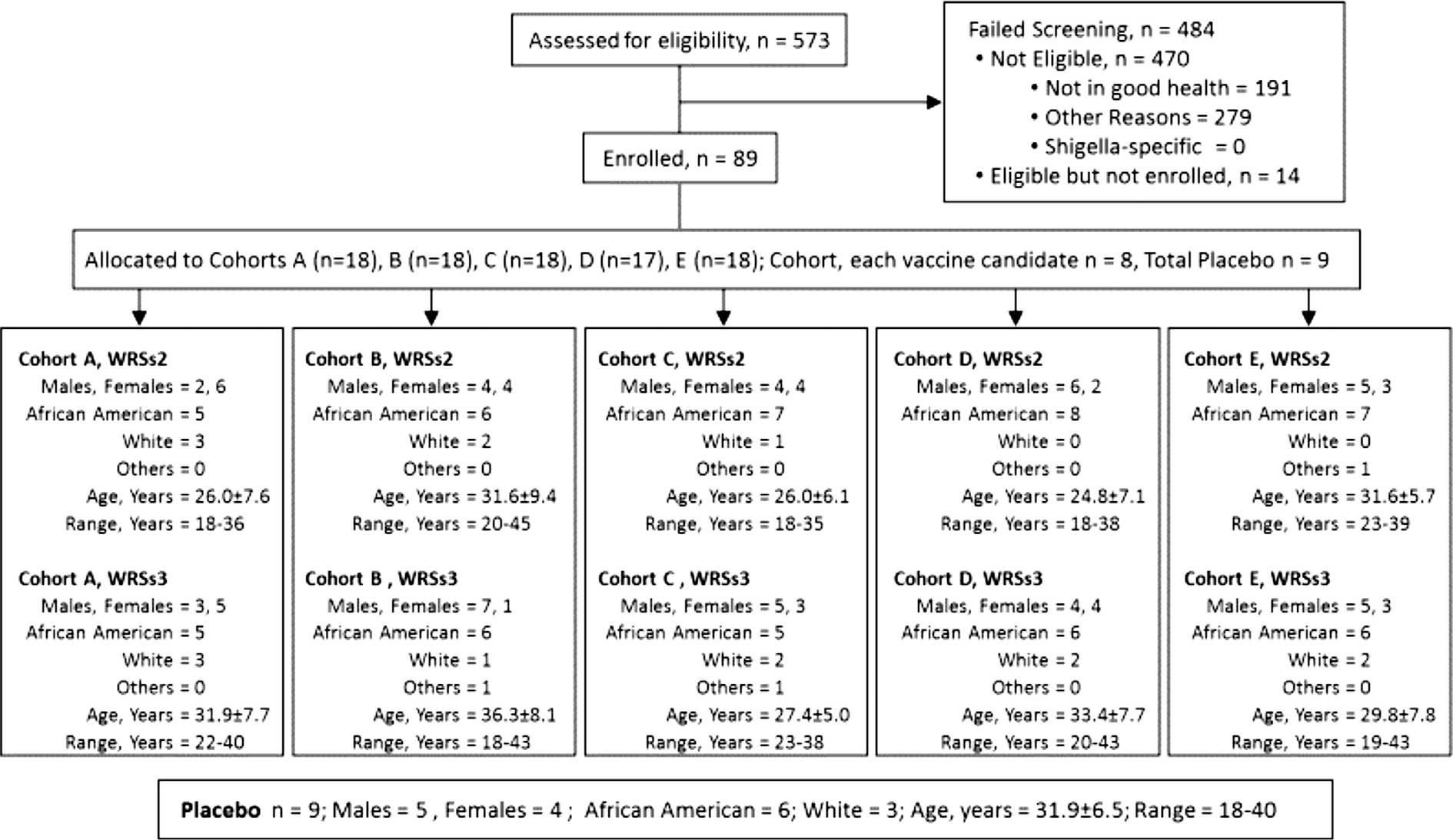

The consort diagram and demographics of the subjects and the actual vaccine dose delivered to each cohort are shown in Fig. 1. Five hundred and seventy-three subjects were screened to enroll the study cohort. The most common reasons for exclusion included; hypertension, elevated hemoglobin A1-c, hypokalemia, anemia and leukopenia. The plan was to enroll 90 subjects, however, for cohort D (106 CFU dose) only one subject received placebo, thus 89 subjects total received study product. Eighty-five subjects (95%) completed the study, while one subject voluntarily withdrew (day 56) and 3 were lost to follow-up (one each on days 14, 56 and 180).

Fig. 1.

Study demographics and subject disposition in the Phase I study (DMID 09–0009) of S. sonnei live oral vaccine candidates WRSs2 and WRSs3.

3.1.1. Clinical response

Both vaccine candidates were safe and well-tolerated, solicited events through 7 days post vaccination are shown in Table 1. No subject developed shigellosis, dysentery or dehydration and there were no vaccine-related SAEs. Except for diarrhea at the highest vaccine dose, vaccine associated adverse events were mild, short lived and resolved without treatment (Table 1). Of the 11 diarrheal episodes, 8 were mild, characterized by 2–3 loose stools of small volume (average weight 108 g) over one 24-hour period that did not affect the subjects’ daily routine (Table 1). At the highest vaccine dose, one subject in the WRSs2 group and two subjects in the WRSs3 group had moderate to severe diarrhea. The subject in the WRSs2 group had 4 loose stools over a 24 h period with a total weight of 178 g. On the same day, this subject also experienced a single episode of mild fever (38.4 °C) that resolved within 5 h and did not recur. Of the 2 subjects in the WRSs3 group, one had a total of 6 loose stools (total weight 1350 g) on days 1 and 2. The 2nd subject had mild diarrhea on day 1 and developed severe diarrhea on day 2 with 7 loose stools totaling 982 g. Other solicited adverse events were not associated with vaccine candidate or dose and the frequency of events such as abdominal cramps and headaches were similar among vaccine and placebo recipients (Table 1). None of the above described symptoms required intervention and no subject required early antibiotic treatment (prior to planned treatment on day 8).

There were 4 unsolicited AEs that were classified as Grade 3 (“severe”). Two of the episodes were systolic hypertension (maximum blood pressure 156) and one was diastolic hypotension (blood pressure 108/45). Each event occurred in a different subject, occurred on different days post-vaccination with different doses of vaccine, was asymptomatic, lasted less than 12 h, resolved spontaneously and did not recur. The fourth severe AE event was related to development of gall stones. None of these events were vaccine-related and only the episode of cholecystitis required treatment.

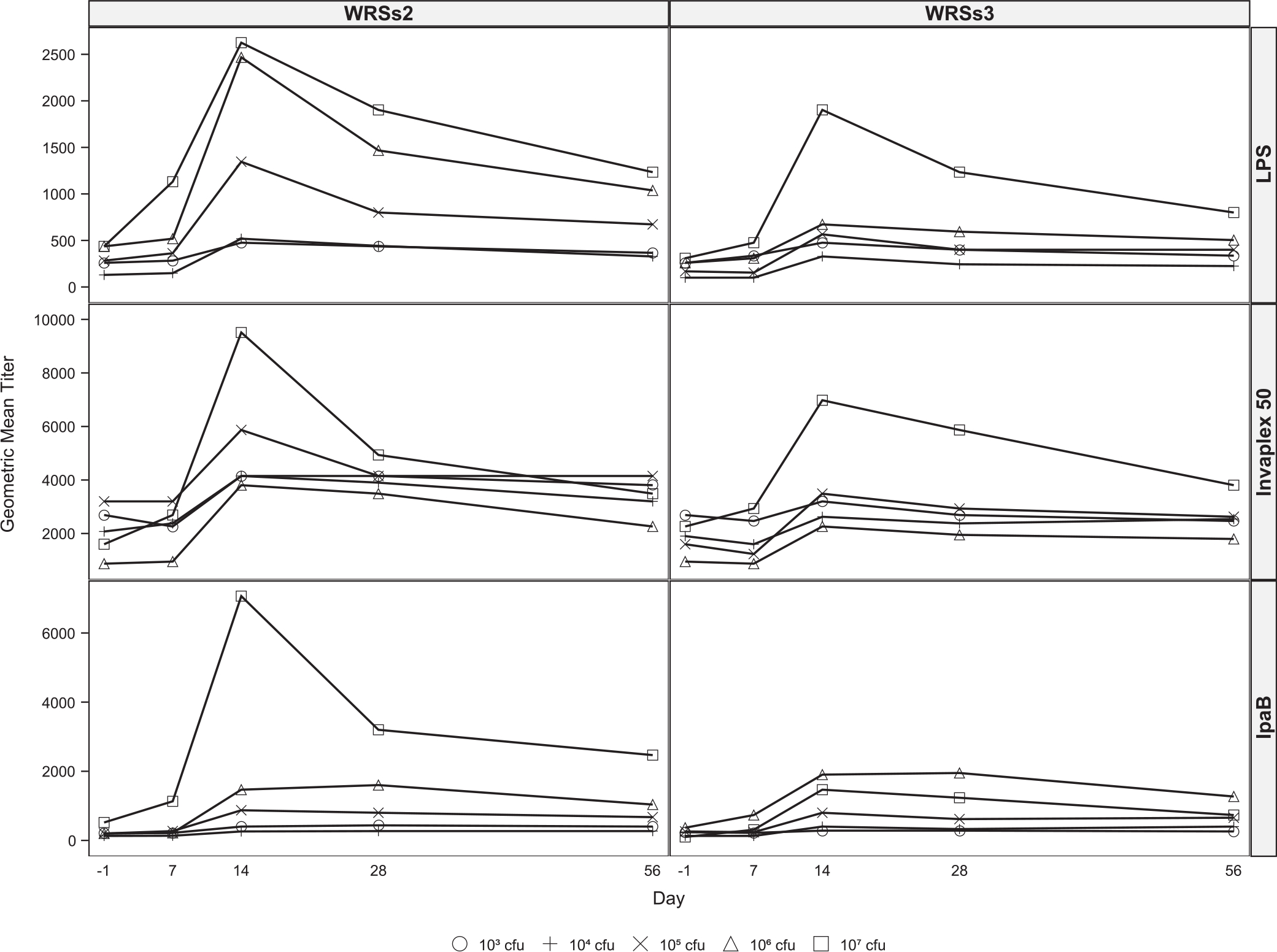

3.2. Serum antibody responses

The kinetics of serum IgG and IgA responses are shown in Fig. 2A and B, respectively. The GMT for serum IgA and IgG generally peaked at day 14 and the peak GMT correlated with the vaccine dose (Fig. 2A). Serum IgG GMTs to IVP were generally higher than to LPS or IpaB for both vaccine candidates, particularly at the three higher doses and although not statistically significant, WRSs2 immunized subjects had higher GMTs than subjects who received WRSs3. In most instances, responses to each antigen gradually declined to baseline levels by day 56 (Fig. 2A and B).

Fig. 2.

Kinetics of serum and fecal antibody responses following vaccination with WRSs2 and WRSs3. Blood for serum IgG (Panel 2A) and IgA (Panel 2B) measurements were collected before vaccination and on days 7, 14, 28 and 56 following vaccination. Stool samples for fecal IgA (Panel 2C) determination were collected before vaccination and on days 7, 10, 14 and 28 after vaccination. Antibody levels in the serum and fecal extracts were measured by ELISA and the data are presented as the geometric mean titers on the Y-axis. The S. sonnei antigens used for antibody detection are shown on the right-hand side of the panel. Individual doses are represented as symbols described at the bottom of the figure.

The responder rates as well as the geometric mean of the maximum fold increase in antibody titers, also appeared related to vaccine dose (Table 2). At the lowest dose of either vaccine, IgA and IgG seroconversion rates to the 3 antigens ranged from 13% to 63%, while at the highest dose, seroconversion rates ranged from 38% to 100%. Additionally, when comparing responses between the two vaccines, WRSs2 recipients had a higher IgA seroresponder rate to LPS and IVP (27 and 32 subjects, respectively) as compared to those who received WRSs3 (22 and 24 subjects, respectively). Similarly, of WRSs2 recipients, 22 and 18 subjects had an LPS-specific and IVP-specific IgG response respectively, compared to 18 and 13 among WRSs3 recipients.

Table 2.

Serum IgG and IgA and Fecal IgA: maximum fold increase from baseline at any time post vaccination.

| Vaccine and Vaccine Dose (cfu) | Serum IgG |

Serum IgA |

Fecal IgA |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LPS | Invaplex | IpaB | LPS | Invaplex | IpaB | LPS | Invaplex | IpaB | ||

|

| ||||||||||

| 103 | WRSs2 | 2.2 ± 2.6 (25) | 2.0 ± 2.3 (38) | 2.2 ± 2.6 (25) | 6.7 ± 7.3 (63) | 5.7 ± 5.9 (50) | 1.5 ± 2.1 (13) | 6.8 ± 4.3 (71) | 14.9 ± 8.0 (71) | 7.9 ± 9.2 (43) |

| WRSs3 | 2.0 ± 1.7 (25) | 1.3 ± 1.9 (13) | 1.3 ± 1.7 (13) | 3.7 ± 4.7 (50) | 3.7 ± 7.2 (38) | 1.4 ± 2.1 (13) | 5.9 ± 3.8 (50) | 12.7 ± 5.9 (75) | 6.8 ± 4.5 (63) | |

| 104 | WRSs2 | 4.0 ± 10.1 (38) | 2.0 ± 2.7 (25) | 2.2 ± 4.3 (25) | 5.2 ± 8.9 (50) | 8.7 ± 9.4 (75) | 1.7 ± 2.6 (25) | 4.4 ± 3.7 (50) | 8.8 ± 12.0 (38) | 4.0 ± 2.8 (38) |

| WRSs3 | 2.6 ± 4.2 (38) | 1.3 ± 2.3 (25) | 2.4 ± 4.6 (25) | 4.0 ± 6.6 (38) | 3.1 ± 6.4 (38) | 2.2 ± 3.5 (25) | 6.2 ± 5.1 (38) | 7.8 ± 12.5 (50) | 4.1 ± 3.1 (50) | |

| 105 | WRSs2 | 4.8 ± 3.4 (75) | 2.2 ± 1.6 (25) | 5.2 ± 2.7 (63) | 12.3 ± 4.0 (75) | 11.3 ± 3.4 (88) | 4.4 ± 3.3 (63) | 3.2 ± 2.6 (50) | 10.3 ± 5.0 (75) | 2.0 ± 5.7 (25) |

| WRSs3 | 3.7 ± 3.7 (38) | 2.2 ± 2.7 (38) | 3.4 ± 10.6 (25) | 6.2 ± 5.4 (50) | 6.7 ± 4.8 (63) | 2.4 ± 7.0 (25) | 4.0 ± 1.7 (63) | 4.5 ± 3.3 (38) | 3.1 ± 4.7 (38) | |

| 106 | WRSs2 | 5.7 ± 3.4 (75) | 5.2 ± 2.8 (75) | 10.4 ± 8.7 (63) | 9.5 ± 4.6 (63) | 13.5 ± 5.2 (88) | 8.0 ± 9.8 (50) | 8.4 ± 7.5 (50) | 21.7 ± 12.1 (75) | 8.9 ± 5.4 (50) |

| WRSs3 | 3.1 ± 2.7 (50) | 2.6 ± 2.7 (50) | 6.2 ± 15.2 (38) | 3.7 ± 3.9 (50) | 9.5 ± 7.0 (75) | 4.8 ± 7.3 (50) | 11.3 ± 6.0 (67) | 11.9 ± 3.6 (83) | 13.9 ± 9.0 (67) | |

| 107 | WRSs2 | 5.7 ± 3.0 (63) | 4.8 ± 3.0 (63) | 12.3 ± 6.6 (63) | 13.5 ± 2.6 (88) | 14.7 ± 2.0 (1 0 0) | 10.4 ± 4.4 (88) | 8.1 ± 5.2 (75) | 17.3 ± 4.7 (88) | 11.0 ± 8.7 (63) |

| WRSs3 | 6.7 ± 3.2 (75) | 3.7 ± 3.5 (38) | 17.4 ± 21.9 (63) | 11.3 ± 4.2 (88) | 26.9 ± 4.6 (88) | 8.0 ± 8.7 (50) | 19.2 ± 4.4 (86) | 43.2 ± 7.1 (1 0 0) | 18.3 ± 16.8 (71) | |

| Placebo | 1.0 ± 1.0 (0) | 1.1 ± 1.7 (11) | 1.0 ± 1.4(0) | 1.0 ± 1.0(0) | 1.1 ± 1.3(0) | 1.0 ± 1.0 (0) | 2.2 ± 5.1 (33) | 3.6 ± 3.7 (44) | 2.8 ± 3.4 (22) | |

Geometric Mean ± Standard Deviation, numbers in the parentheses are percent with ≥4~fold increase at any time after vaccination.

In contrast to serum GMT responses, the maximum fold increase of antibody titer to IVP and LPS was higher for serum IgA than serum IgG, in part due to a higher baseline IgG compared to IgA. For IpaB, the fold increases for IgA and IgG were equivalent (Table 2).

3.3. Fecal IgA responses

The kinetics of fecal IgA is shown in Fig. 2C and the fecal IgA responder rates are summarized in Table 2. Compared to WRSs3, the antigen-specific fecal IgA levels were higher among WRSs2 recipients, generally peaking between days 10–14 post vaccination (Panel 2C). At the lowest dose, 43–75% of vaccinees in both groups demonstrated a fecal IgA response to all 3 antigens, and at the three highest doses 25–100% of the subjects responded in a similar manner. In contrast to serum antibody responses, neither the magnitude of fecal IgA response against either antigen, nor the responder rates, was clearly dose-dependent. There were generally no notable differences between the fecal IgA response of WRSs2 and WRSs3 at the same dose to the same antigens except at the highest dose where the maximum fold rise in fecal IgA titers to LPS, IVP and IpaB was almost two-fold higher in WRSs3 immunized subjects compared to WRSs2 (Table 2). Although 22–44% of the placebo recipients also demonstrated a measurable fecal IgA response to the Shigella antigens, the titers were of lower magnitude as compared to vaccine recipients (Table 2).

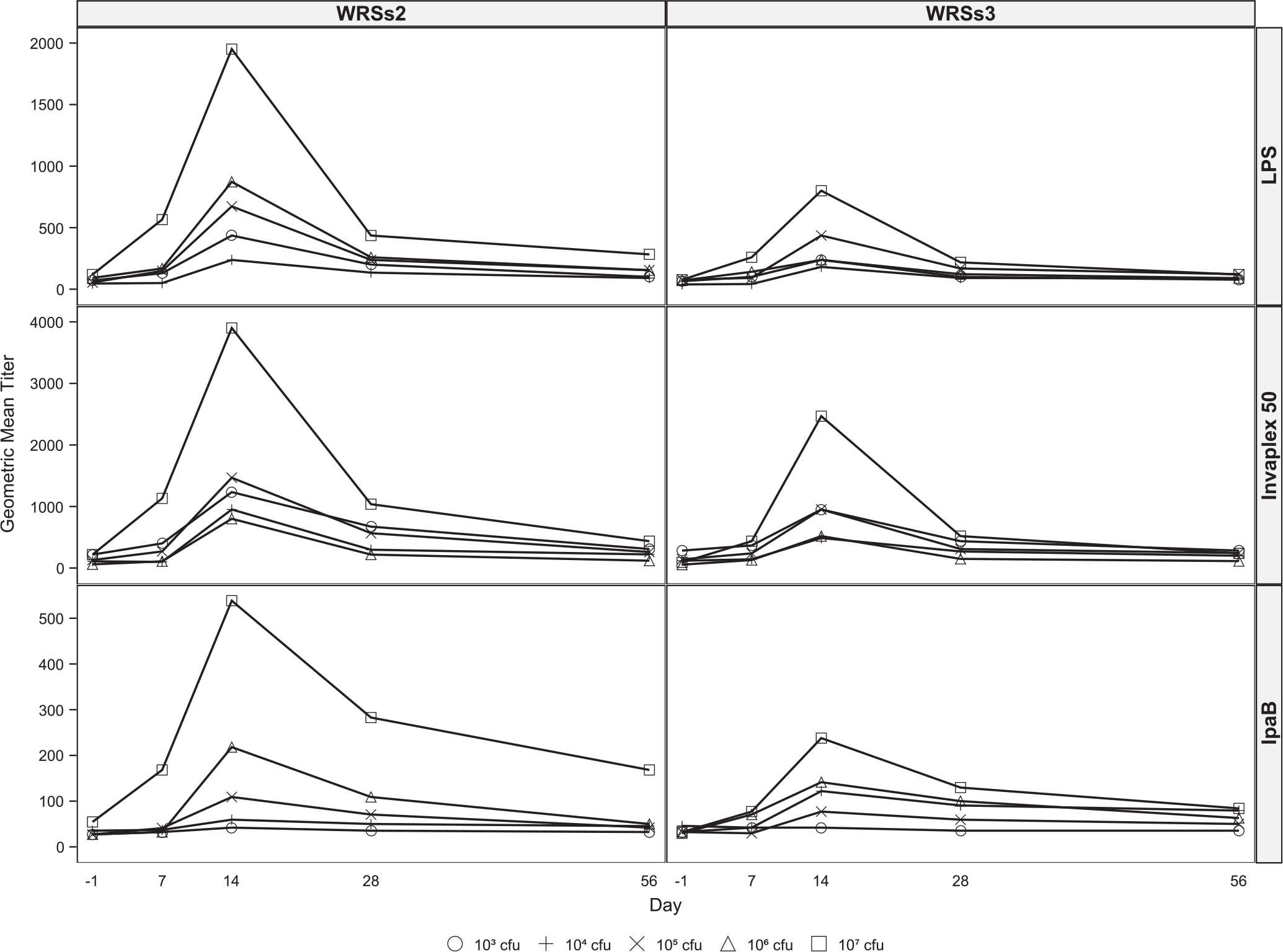

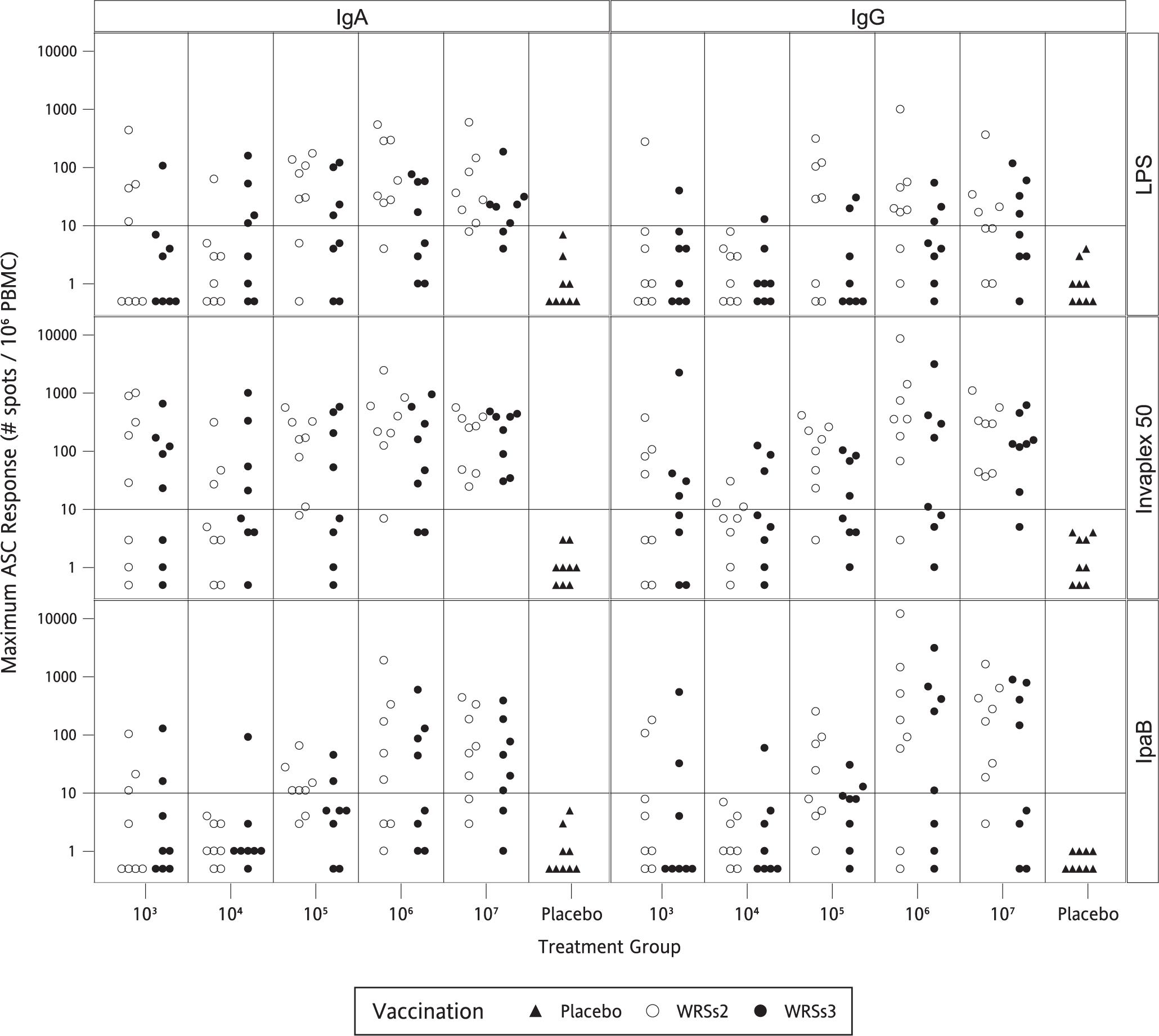

3.4. ASC responses

While at the lowest vaccine dose some subjects had a high ASC response to LPS and IVP, generally the ASC numbers and the responder rates for both candidates increased with increasing doses (Table 3 and Fig. 3). Overall, the ASCs responses were higher in magnitude in the WRSs2 immunized subjects. Even at the lowest dose, ASCs against IVP were more frequently detected than LPS or IpaB, and at ≥106 doses, 88–100% of the subjects in both groups demonstrated a significant IgA-ASC response to IVP as well as to LPS.

Table 3.

GM of maximum antibody secreting cell (ASC) responses in WRSs2 and WRSs3-immunized subjects.

| Vaccine and vaccine dose (cfu) | IgA |

IgG |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LPS | Invaplex | IpaB | LPS | Invaplex | IpaB | ||

|

| |||||||

| 103 | WRSs2 | 5.4 ± 15.4 (50) | 35.2 ± 21.7 (63) | 2.9 ± 8.2 (38) | 2.4 ± 8.9 (13) | 11.5 ± 13.0 (50) | 4.5 ± 10.4 (25) |

| WRSs3 | 2.2 ± 6.8 (13) | 21.3 ± 13.9 (63) | 2.4 ± 7.6 (25) | 2.2 ± 5.0 (13) | 11.9 ± 15.1 (50) | 2.6 ± 14.0 (25) | |

| 104 | WRSs2 | 2.1 ± 5.3 (13) | 6.8 ± 9.5 (38) | 1.3 ± 2.3 (0) | 1.6 ± 3.0 (0) | 5.1 ± 3.9 (38) | 1.5 ± 2.7 (0) |

| WRSs3 | 5.7 ± 8.7 (50) | 19.6 ± 12.3 (50) | 1.9 ± 5.2 (13) | 1.3 ± 3.2 (13) | 8.6 ± 7.8 (38) | 1.7 ± 5.6 (13) | |

| 105 | WRSs2 | 28.7 ± 7.4 (75) | 101.2 ± 4.9 (88) | 12.0 ± 2.7 (75) | 13.1 ± 13.9 (63) | 77.6 ± 5.1 (88) | 16.9 ± 6.5 (50) |

| WRSs3 | 8.2 ± 8.3 (50) | 21.2 ± 16.0 (50) | 4.0 ± 4.7 (25) | 1.8 ± 5.7 (25) | 13.6 ± 5.5 (50) | 4.9 ± 3.9 (25) | |

| 106 | WRSs2 | 63.5 ± 5.2 (88) | 256.6 ± 5.6 (88) | 30.8 ± 14.1 (63) | 22.5 ± 7.5 (75) | 284.0 ± 10.3 (88) | 90.8 ± 31.2 (75) |

| WRSs3 | 9.5 ± 6.2 (50) | 69.8 ± 8.4 (75) | 16.1 ± 11.2 (50) | 5.0 ± 4.7 (38) | 48.2 ± 15.5 (63) | 37.4 ± 27.8 (63) | |

| 107 | WRSs2 | 43.6 ± 4.2 (88) | 151.0 ± 3.3 (1 0 0) | 50.4 ± 6.0 (75) | 11.8 ± 6.8 (50) | 182.0 ± 3.7 (1 0 0) | 119.2 ± 8.2 (88) |

| WRSs3 | 19.8 ± 3.1 (75) | 171.6 ± 3.2 (1 0 0) | 26.9 ± 7.1 (75) | 10.2 ± 6.1 (50) | 98.9 ± 4.9 (88) | 25.1 ± 25.4 (50) | |

| Placebo | 1.0 ± 2.6(0) | 1.0 ± 2.0(0) | 0.9 ± 2.4 (0) | 1.0 ± 2.2 (0) | 1.4 ± 2.5 (0) | 0.7 ± 1.4(0) | |

Geometric Mean ± Standard Deviation, numbers in the parentheses are percent with ≥10 ASC/106 PBMCs.

Fig. 3.

Maximum ASC response to S. sonnei LPS, IVP and IpaB following vaccination with WRSs2 and WRSs3. The open circles denote WRSs2 and the closed circles denote WRSs3 immunized subjects. The X-axis shows vaccine doses. The Y axis on the left side of the panel gives the maximum IgA and IgG ASC responses of individual subjects to S. sonnei antigens shown on the right-hand side of the panel.

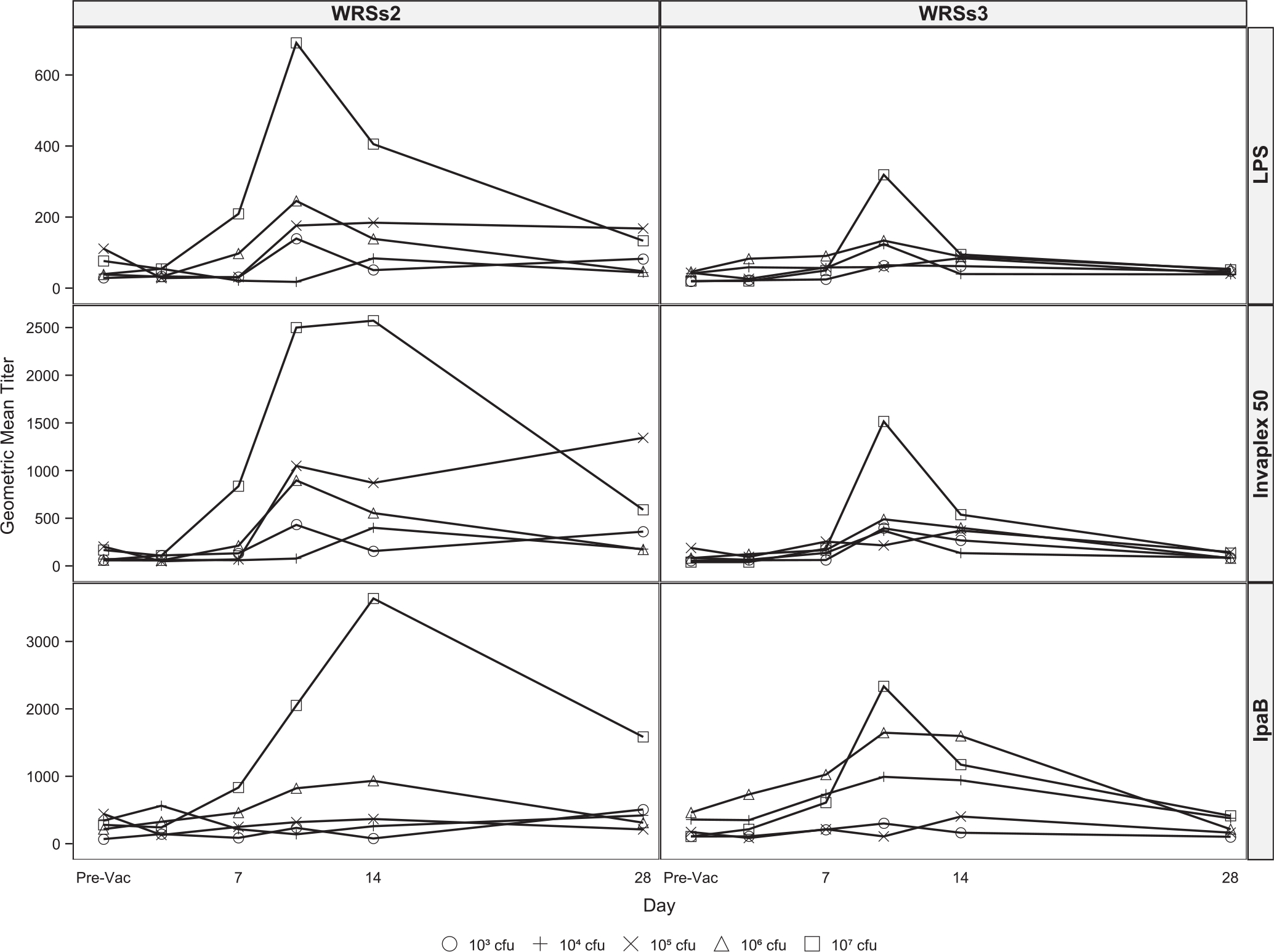

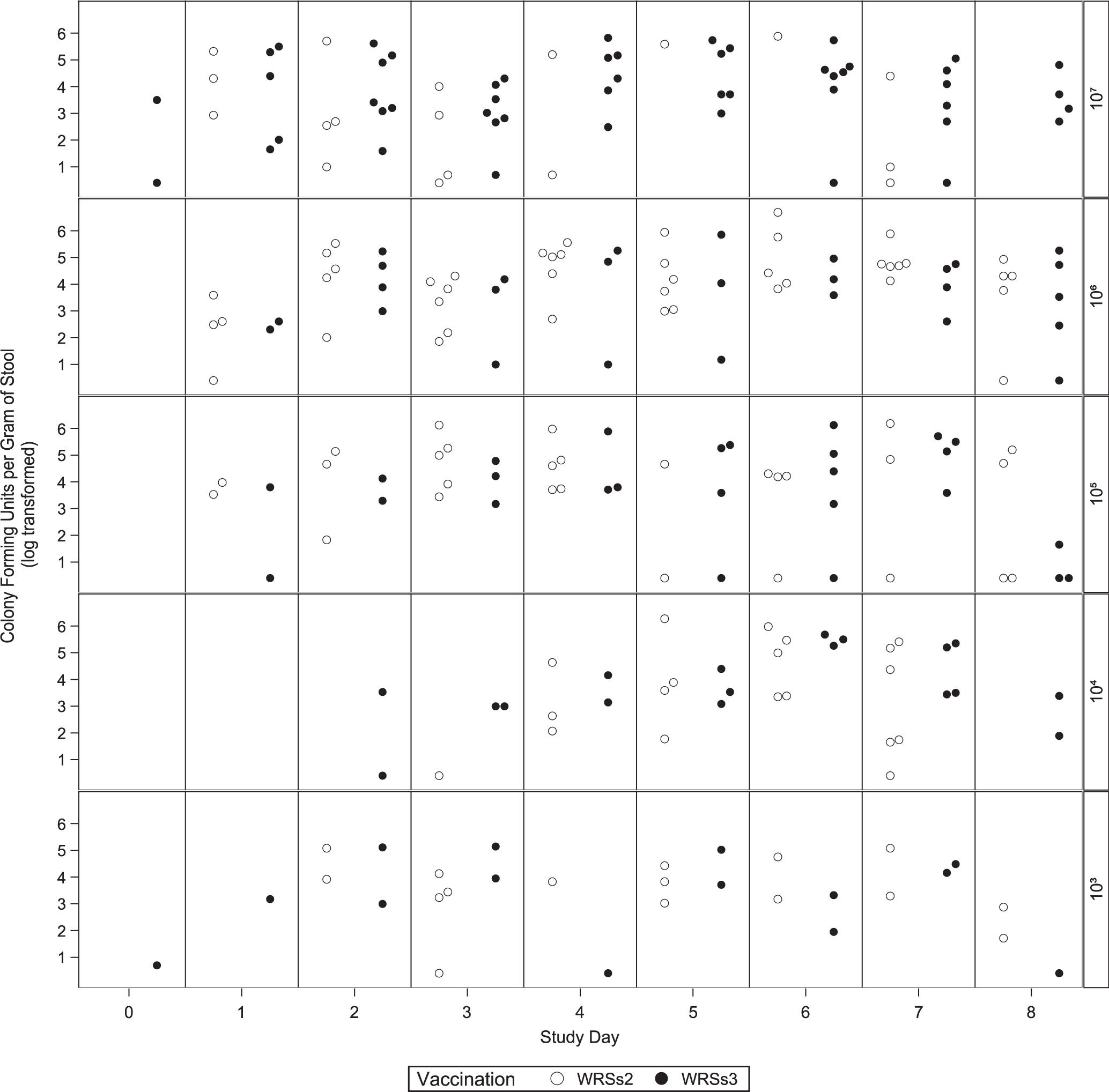

3.5. Fecal shedding

The magnitude of shedding of the vaccine strain was robust for both vaccine candidates, and the frequency of subjects colonized was associated with the vaccine dose (Fig. 4). Overall, among WRSs2 vaccinees, 28 of 40 (70%) subjects shed the vaccine as compared to 25 of 40 (63%) subjects who received WRSs3. Of subjects who received a 105 or 106 CFU dose of WRSs2, 88% shed the vaccine as compared to 50% and 63% respectively among subjects receiving WRSs3. Subjects typically shed the vaccine strain in their stool between 2 and 6 days although some subjects shed until the initiation of antibiotic treatment. No subject receiving placebo shed Shigella (data not shown).

Fig. 4.

Vaccine shedding after WRSs2 and WRSs3 immunization. The X-axis provides the days after vaccination and the Y-axis on the left shows the magnitude of shedding described as the maximum colony blot positive CFU per gram of stool shed per subject immunized with either WRSs2 (open circles) or WRSs3 (closed circles). The magnitude of shedding is presented by group and study day using log-transformed data. The Y-axis on the right-hand side of the panel provides the immunization doses from the lowest to the highest dose.

4. Discussion

Shigella vaccine development has focused on three approaches: (a) whole-cell killed or live attenuated strains constructed through deletions of metabolic and virulence genes, (b) subunit vaccines with and without Shigella LPS and (c) hybrid strains such as E. coli or Salmonella typhi expressing Shigella antigens [17–23]. A previous Phase I study of 27 subjects who received a dose of WRSS1 ranging from 103 to 106 CFU demonstrated that the vaccine was generally safe and well tolerated at the lower two doses with only 1 of 11 (9%) vaccinees having fever or loose stools. However, at the two higher doses (105 and 106 CFU), 5 of 16 (31%) subjects had vaccine-related symptoms of diarrhea and/or fever. A similar safety profile was also seen in an outpatient study in Israel leading to the conclusion that at doses of 104 CFU or lower, the vaccine was safe and highly immunogenic [4,5]. However, at higher doses >104 CFU WRSS1 was too reactogenic suggesting further attenuation was needed [4,5].

In this study, we demonstrated the safety, immunogenicity and shedding patterns of two second generation live S. sonnei vaccine candidates, WRSs2 and WRSs3. In addition to deletions in the virG(icsA) gene, both candidates have deletions of the enterotoxin gene senA and its paralog senB. WRSs3 has been further attenuated through loss of the virulence plasmid-based msbB2 gene [7]. Since both WRSs2 and WRSs3 were well tolerated at doses up to 106 CFU the safety window has been widened by almost 2 logs over WRSS1. No subject in the current study developed dysentery, dehydration or any other moderate to severe constitutional symptoms. All three cases of moderate to severe diarrhea, along with the episode of mild fever occurred in subjects receiving the highest dose of the vaccine. Thus, for future studies, dosing likely will need to be at or below 106 CFU.

The differences between the two candidates in the current trial were more evident in their immunogenicity profiles. While both WRSs2 and WRSs3 induced robust humoral and mucosal immune responses, overall, serum antibody titers and ASC levels were higher in the WRSs2 vaccinated subjects. Responder rates for the immune responses to Shigella antigens, between the doses of 105 and 106 CFU, considered the safe dose for both candidates, were also higher in the WRSs2 group of subjects. This may relate to a link between the immunogenicity of a live Shigella vaccine and shedding of the vaccine in the stool. [4,15]. WRSs2 induced the highest immune responses at 105 and 106 CFU doses where 14 of the 16 subjects (88%) shed the vaccine and 9 of these 14 subjects shed the vaccine robustly for more than 6 days. In contrast, 9 of 16 subjects (56%) receiving 105 and 106 CFU of WRSs3 shed the vaccine for 6 days. However, at 107 dose of WRSs3, 100% of the subjects shed the vaccine and demonstrated the highest overall immune responses. Unfortunately, this dose was also associated with 2 of 8 subjects demonstrating moderate to severe diarrhea. Overall, the immune response of subjects did not appear to correlate with whether they experienced diarrhea after vaccination. Based on the safety data discussed above, the optimal dose of WRSs2 or WRSs3 lies within the range of 105 to 106 CFU. From these studies it appears that deletion of msbB2 did not impart a clear advantage to the vaccine strain in terms of safety or immunogenicity.

Among questions remaining for live Shigella vaccines are the number and schedule of doses needed to induce a durable protective immunity. In a previous trial, 12 subjects were immunized with a single 104 CFU dose of a S. flexneri 2a vaccine SC602 and 7 were challenged two months later with a wild type strain of S. flexneri [24]. All 7 (100%) were protected against moderate to severe diarrhea and fever while 6 of 7 unimmunized control subjects had shigellosis. The immune responses post vaccination in the SC602 study compare favorably with the responses seen in this study with WRSs2 at the 106 CFU dose indicating that the immunogenicity seen with WRSs2 could be protective.

However, it is unclear how long immunity persists after a single dose of a live Shigella vaccine. In a real-world setting, endemic populations are believed to be protected due to continual exposure to specific enteric pathogens [25,26]. Based on that observation, more than one dose of vaccine likely will be needed to induce effective protection in naïve individuals. From the current study, the immune responses seen with WRSs2 and WRSs3 suggest that administering at least 2 doses of the vaccine, and perhaps a booster dose later will be needed to maintain immunity. Since most of the primary immune responses in the current study appear to peak between 7 and 14 days and trend to baseline by 28–56 days, the second dose likely will need to be 1–2 months after the first dose.

The current study also demonstrates the importance of bacterial colonization as measured by fecal shedding of the vaccine and the immune response associated with shedding. This has been seen previously with SC602 and WRSS1 [4,24]. In the WRSs2 immunized group that received 105 and 106 CFU dose, 14 of the 16 subjects shed the vaccine. Of these 14 shedders, 13 subjects (93%) were positive for LPS-specific IgA ASC, and all 14 subjects (100%) responded with a ≥4-fold serum IgA or IgG titer over baseline. 12 of these 14 subjects (86%) also had a ≥4-fold fecal IgA response to LPS and IVP. Of the 2 vaccinees that did not shed at these two doses, one did not have a serum IgA/IgG, ASC IgA/IgG or a fecal IgA response to any of the 3 antigens. The second subject had only IgG ASC response to the 3 antigens and fecal IgA to LPS. In the WRSs3 group, 100% of the subjects at the 107 dose shed the vaccine and 7 of 8 (88%) demonstrated an ASC and serum IgA and/or IgG response to LPS and Invaplex50. One subject who had very low level of shedding (45 CFU/gm of stool) did not have serum IgA to IVP, serum IgG to LPS and IVP and LPS-specific IgA or IgG ASC. These responses indicate that live vaccines, that mimic a natural infection, require robust colonization to elicit a good immune response.

In summary, S. sonnei vaccine candidates WRSs2 and WRSs3 demonstrated a good safety profile over a wide dose range and elicited strong humoral and mucosal immune responses. The encouraging results of this study warrant future studies including efficacy in a human challenge model as well as strategies to combine the most promising candidate into a multivalent vaccine cocktail of different Shigella serotypes.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Lakshmi Chandrasekaran for viability studies of the vaccine candidates. The authors also thank Chad Porter for thoughtful review of the manuscript. This Phase 1 study was sponsored and funded by DMID VTEU (Vaccine and Treatment Evaluation Units), Contract Number: HHSN272201300016I.

WRSs2 and WRSs3 were developed under the Department of Army’s Military Infectious Disease Research Program (MIDRP). The opinions or assertions contained herein are the private views of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official views of WRAIR, the Department of the Army or the Department of Defense.

The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy or position of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, the National Institutes of Health, the Department of Health and Human Services, or the U.S. Government.

References

- [1].Kotloff KL et al. Global burden of Shigella infections: implications for vaccine development and implementation of control strategies. Bull World Health Organ 1999;77(8):651–66. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Chang Z et al. The changing epidemiology of bacillary dysentery and characteristics of antimicrobial resistance of Shigella isolated in China from 2004–2014. BMC Infect Dis 2016;16(1):685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Hartman AB, Venkatesan MM. Construction of a stable attenuated Shigella sonnei DeltavirG vaccine strain, WRSS1, and protective efficacy and immunogenicity in the guinea pig keratoconjunctivitis model. Infect Immun 1998;66(9):4572–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Kotloff KL et al. Phase I evaluation of delta virG Shigella sonnei live, attenuated, oral vaccine strain WRSS1 in healthy adults. Infect Immun 2002;70(4):2016–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Orr N et al. Community-based safety, immunogenicity, and transmissibility study of the Shigella sonnei WRSS1 vaccine in Israeli volunteers. Infect Immun 2005;73(12):8027–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Barnoy S et al. Shigella sonnei vaccine candidates WRSs2 and WRSs3 are as immunogenic as WRSS1, a clinically tested vaccine candidate, in a primate model of infection. Vaccine 2011;29(37):6371–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Barnoy S et al. Characterization of WRSs2 and WRSs3, new second-generation virG(icsA)-based Shigella sonnei vaccine candidates with the potential for reduced reactogenicity. Vaccine 2010;28(6):1642–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Jeong KI et al. Evaluation of virulent and live Shigella sonnei vaccine candidates in a gnotobiotic piglet model. Vaccine 2013;31(37):4039–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Mills JA, Buysse JM, Oaks EV. Shigella flexneri invasion plasmid antigens B and C: epitope location and characterization with monoclonal antibodies. Infect Immun 1988;56(11):2933–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Riddle MS et al. Safety and immunogenicity of an intranasal Shigella flexneri 2a Invaplex 50 vaccine. Vaccine 2011;29(40):7009–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Turbyfill KR, Kaminski RW, Oaks EV. Immunogenicity and efficacy of highly purified invasin complex vaccine from Shigella flexneri 2a. Vaccine 2008;26(10):1353–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Picking WL et al. Cloning, expression, and affinity purification of recombinant Shigella flexneri invasion plasmid antigens IpaB and IpaC. Protein Expr Purif 1996;8(4):401–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Kaminski RW et al. Development and preclinical evaluation of a trivalent, formalin-inactivated Shigella whole-cell vaccine. Clin Vaccine Immunol 2014;21(3):366–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Bodhidatta L et al. Establishment of a Shigella sonnei human challenge model in Thailand. Vaccine 2012;30(49):7040–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Pitisuttithum P et al. Clinical trial of an oral live Shigella sonnei vaccine candidate, WRSS1, in Thai Adults. Clin Vaccine Immunol 2016;23(7):564–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Tribble D et al. Safety and immunogenicity of a Shigella flexneri 2a Invaplex 50 intranasal vaccine in adult volunteers. Vaccine 2010;28(37):6076–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Venkatesan MM, Ranallo RT. Live-attenuated Shigella vaccines. Expert Rev Vaccines 2006;5(5):669–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Kaminski RW, Oaks EV. Inactivated and subunit vaccines to prevent shigellosis. Expert Rev Vaccines 2009;8(12):1693–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Dharmasena MN et al. Stable expression of Shigella sonnei form I O-polysaccharide genes recombineered into the chromosome of live Salmonella oral vaccine vector Ty21a. Int J Med Microbiol 2013;303(3):105–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Riddle MS et al. Safety and immunogenicity of a candidate bioconjugate vaccine against Shigella flexneri 2a administered to healthy adults: a single-blind, randomized phase I study. Clin Vaccine Immunol 2016;23(12):908–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Rossi O et al. Modulation of endotoxicity of Shigella generalized modules for membrane antigens (GMMA) by genetic lipid A modifications: relative activation of TLR4 and TLR2 pathways in different mutants. J Biol Chem 2014;289(36):24922–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].van der Put RM et al. A synthetic carbohydrate conjugate vaccine candidate against Shigellosis: improved bioconjugation and impact of alum on immunogenicity. Bioconjug Chem 2016;27(4):883–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Mani S, Wierzba T, Walker RI. Status of vaccine research and development for Shigella. Vaccine 2016;34(26):2887–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Coster TS et al. Vaccination against shigellosis with attenuated Shigella flexneri 2a strain SC602. Infect Immun 1999;67(7):3437–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Guerrero L et al. Asymptomatic Shigella infections in a cohort of Mexican children younger than two years of age. Pediatr Infect Dis J 1994;13(7):597–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Clemens J et al. Development of pathogenicity-driven definitions of outcomes for a field trial of a killed oral vaccine against enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli in Egypt: application of an evidence-based method. J Infect Dis 2004;189(12):2299–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]