Abstract

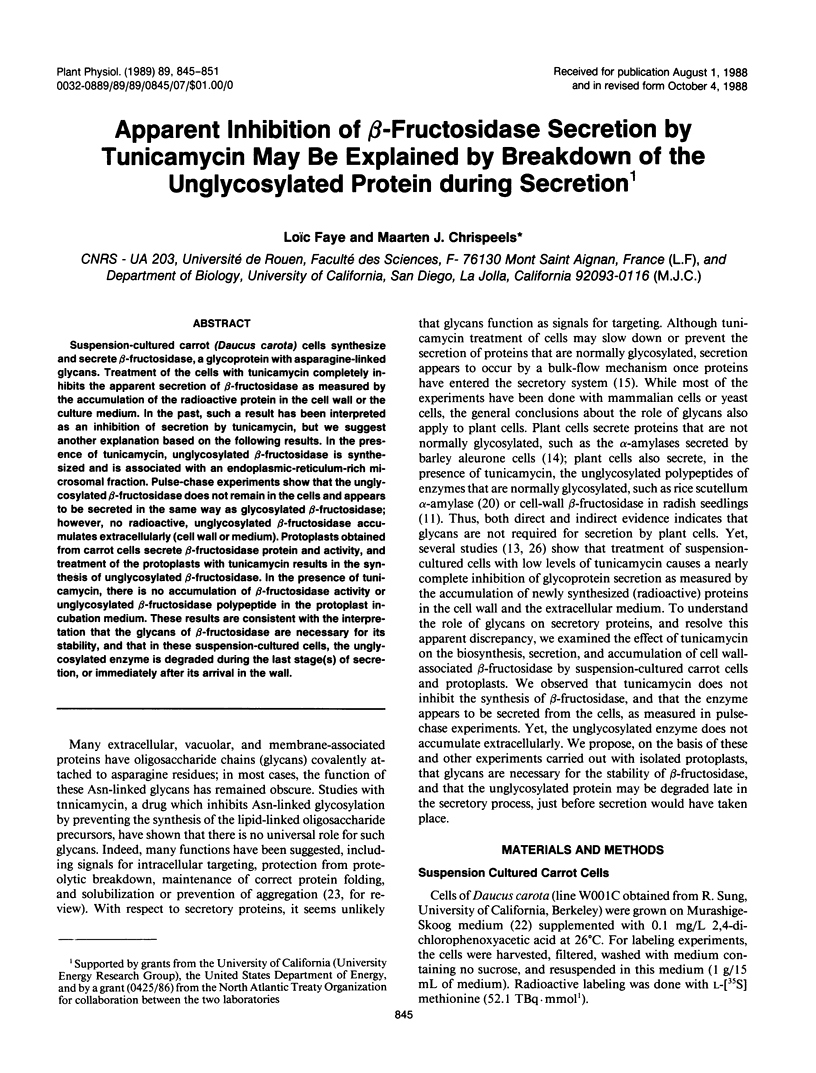

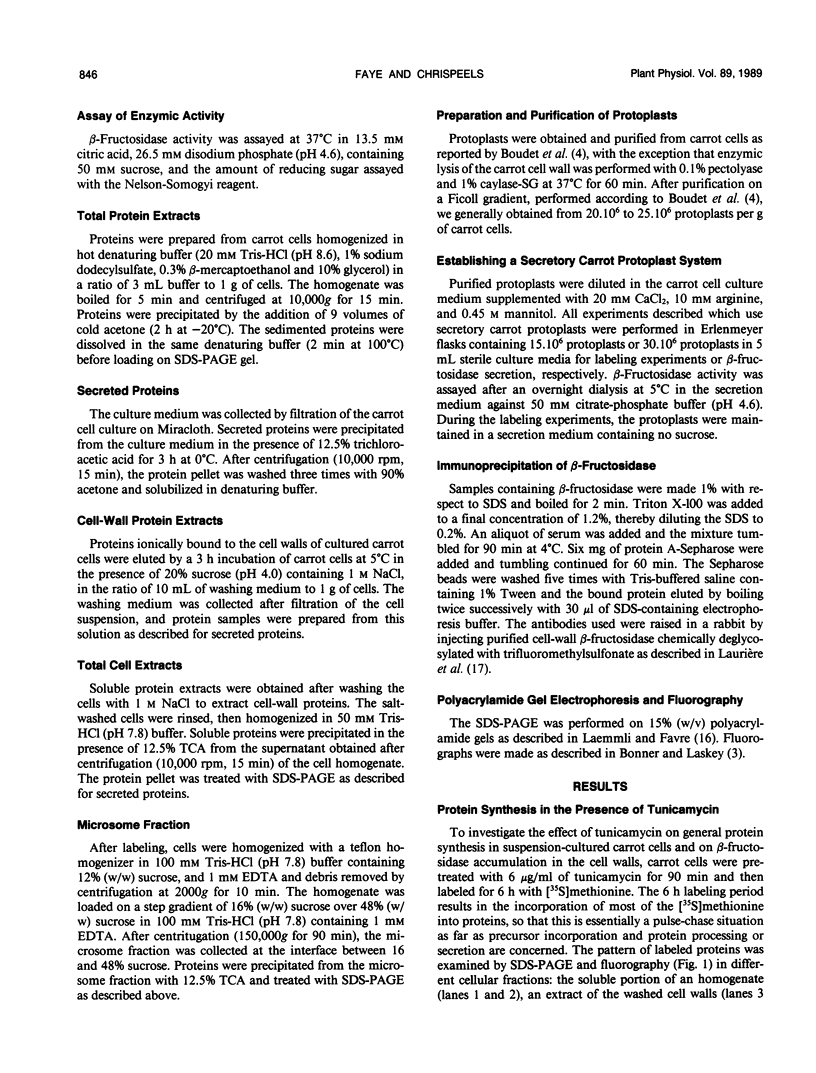

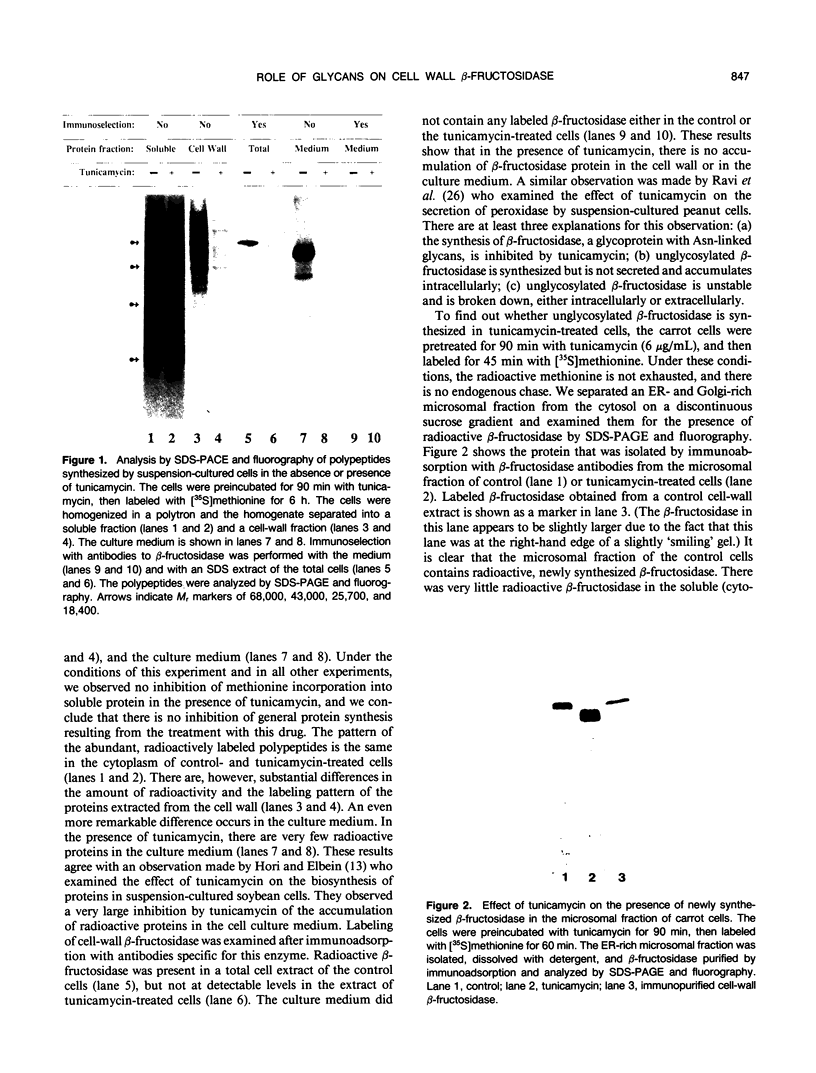

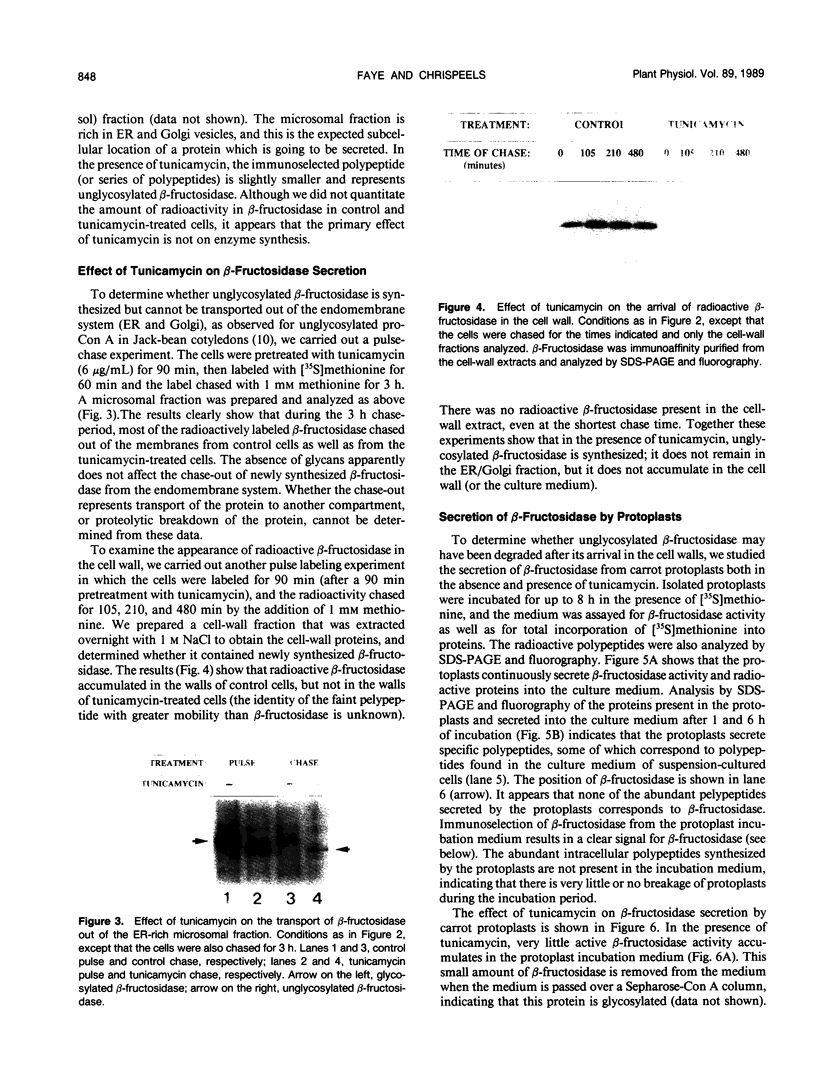

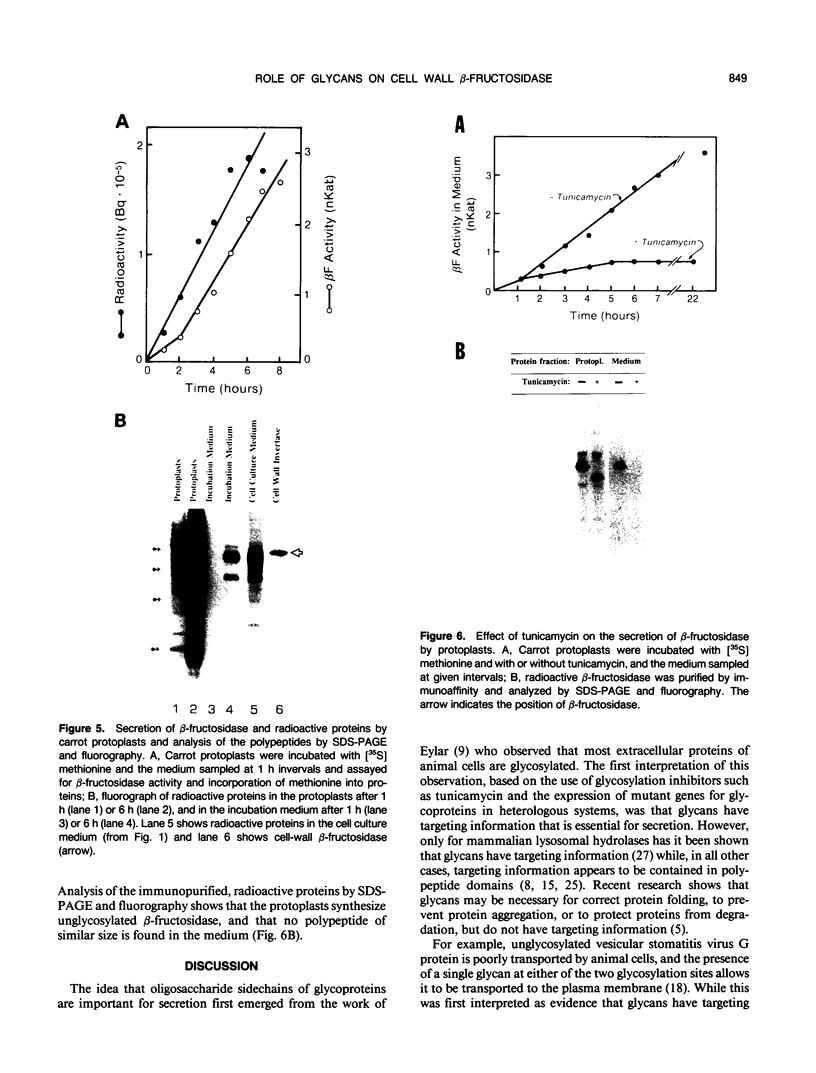

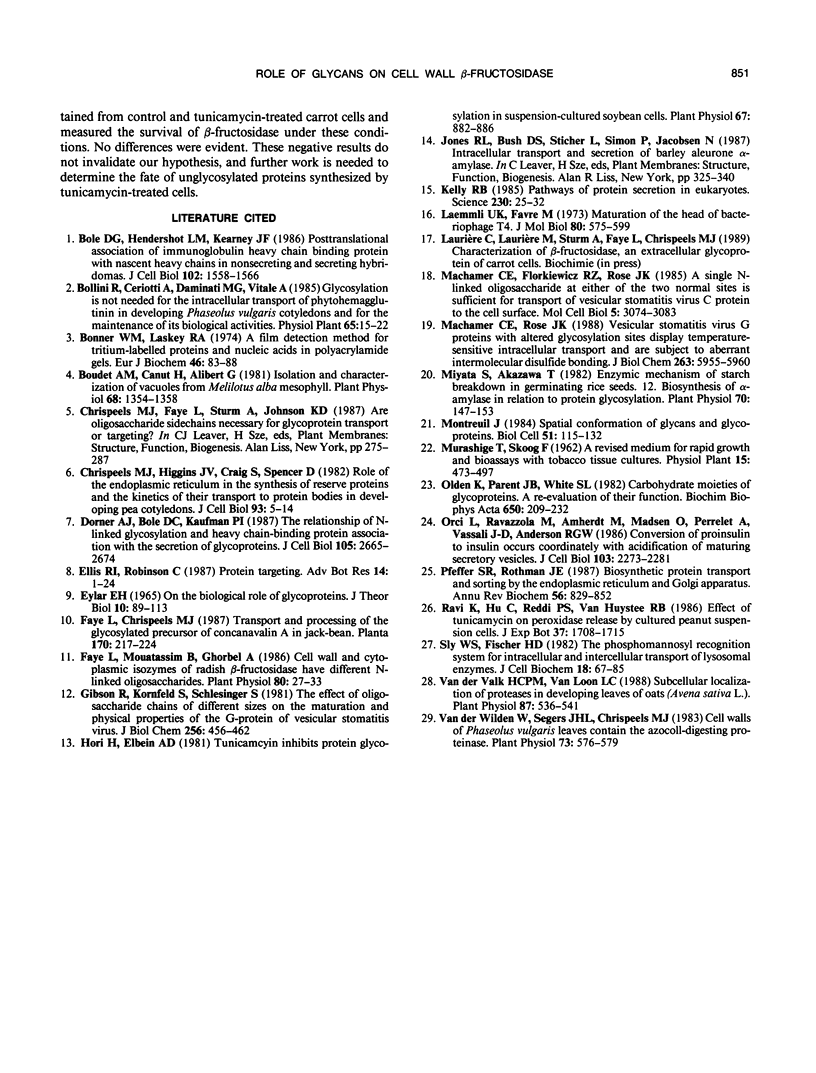

Suspension-cultured carrot (Daucus carota) cells synthesize and secrete β-fructosidase, a glycoprotein with asparagine-linked glycans. Treatment of the cells with tunicamycin completely inhibits the apparent secretion of β-fructosidase as measured by the accumulation of the radioactive protein in the cell wall or the culture medium. In the past, such a result has been interpreted as an inhibition of secretion by tunicamycin, but we suggest another explanation based on the following results. In the presence of tunicamycin, unglycosylated β-fructosidase is synthesized and is associated with an endoplasmic-reticulum-rich microsomal fraction. Pulse-chase experiments show that the unglycosylated β-fructosidase does not remain in the cells and appears to be secreted in the same way as glycosylated β-fructosidase; however, no radioactive, unglycosylated β-fructosidase accumulates extracellularly (cell wall or medium). Protoplasts obtained from carrot cells secrete β-fructosidase protein and activity, and treatment of the protoplasts with tunicamycin results in the synthesis of unglycosylated β-fructosidase. In the presence of tunicamycin, there is no accumulation of β-fructosidase activity or unglycosylated β-fructosidase polypeptide in the protoplast incubation medium. These results are consistent with the interpretation that the glycans of β-fructosidase are necessary for its stability, and that in these suspension-cultured cells, the unglycosylated enzyme is degraded during the last stage(s) of secretion, or immediately after its arrival in the wall.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Bole D. G., Hendershot L. M., Kearney J. F. Posttranslational association of immunoglobulin heavy chain binding protein with nascent heavy chains in nonsecreting and secreting hybridomas. J Cell Biol. 1986 May;102(5):1558–1566. doi: 10.1083/jcb.102.5.1558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonner W. M., Laskey R. A. A film detection method for tritium-labelled proteins and nucleic acids in polyacrylamide gels. Eur J Biochem. 1974 Jul 1;46(1):83–88. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1974.tb03599.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boudet A. M., Canut H., Alibert G. Isolation and Characterization of Vacuoles from Melilotus alba Mesophyll. Plant Physiol. 1981 Dec;68(6):1354–1358. doi: 10.1104/pp.68.6.1354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chrispeels M. J., Higgins T. J., Craig S., Spencer D. Role of the endoplasmic reticulum in the synthesis of reserve proteins and the kinetics of their transport to protein bodies in developing pea cotyledons. J Cell Biol. 1982 Apr;93(1):5–14. doi: 10.1083/jcb.93.1.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorner A. J., Bole D. G., Kaufman R. J. The relationship of N-linked glycosylation and heavy chain-binding protein association with the secretion of glycoproteins. J Cell Biol. 1987 Dec;105(6 Pt 1):2665–2674. doi: 10.1083/jcb.105.6.2665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eylar E. H. On the biological role of glycoproteins. J Theor Biol. 1966 Jan;10(1):89–113. doi: 10.1016/0022-5193(66)90179-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faye L., Mouatassim B., Ghorbel A. Cell Wall and Cytoplasmic Isozymes of Radish beta-Fructosidase Have Different N-Linked Oligosaccharides. Plant Physiol. 1986 Jan;80(1):27–33. doi: 10.1104/pp.80.1.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson R., Kornfeld S., Schlesinger S. The effect of oligosaccharide chains of different sizes on the maturation and physical properties of the G protein of vesicular stomatitis virus. J Biol Chem. 1981 Jan 10;256(1):456–462. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hori H., Elbein A. D. Tunicamycin inhibits protein glycosylation in suspension cultured soybean cells. Plant Physiol. 1981 May;67(5):882–886. doi: 10.1104/pp.67.5.882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly R. B. Pathways of protein secretion in eukaryotes. Science. 1985 Oct 4;230(4721):25–32. doi: 10.1126/science.2994224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laemmli U. K., Favre M. Maturation of the head of bacteriophage T4. I. DNA packaging events. J Mol Biol. 1973 Nov 15;80(4):575–599. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(73)90198-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machamer C. E., Florkiewicz R. Z., Rose J. K. A single N-linked oligosaccharide at either of the two normal sites is sufficient for transport of vesicular stomatitis virus G protein to the cell surface. Mol Cell Biol. 1985 Nov;5(11):3074–3083. doi: 10.1128/mcb.5.11.3074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machamer C. E., Rose J. K. Vesicular stomatitis virus G proteins with altered glycosylation sites display temperature-sensitive intracellular transport and are subject to aberrant intermolecular disulfide bonding. J Biol Chem. 1988 Apr 25;263(12):5955–5960. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyata S., Akazawa T. Enzymic mechanism of starch breakdown in germinating rice seeds : 12. Biosynthesis of alpha-amylase in relation to protein glycosylation. Plant Physiol. 1982 Jul;70(1):147–153. doi: 10.1104/pp.70.1.147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montreuil J. Spatial conformation of glycans and glycoproteins. Biol Cell. 1984;51(2):115–131. doi: 10.1111/j.1768-322x.1984.tb00291.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olden K., Parent J. B., White S. L. Carbohydrate moieties of glycoproteins. A re-evaluation of their function. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1982 May 12;650(4):209–232. doi: 10.1016/0304-4157(82)90017-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orci L., Ravazzola M., Amherdt M., Madsen O., Perrelet A., Vassalli J. D., Anderson R. G. Conversion of proinsulin to insulin occurs coordinately with acidification of maturing secretory vesicles. J Cell Biol. 1986 Dec;103(6 Pt 1):2273–2281. doi: 10.1083/jcb.103.6.2273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeffer S. R., Rothman J. E. Biosynthetic protein transport and sorting by the endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi. Annu Rev Biochem. 1987;56:829–852. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.56.070187.004145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sly W. S., Fischer H. D. The phosphomannosyl recognition system for intracellular and intercellular transport of lysosomal enzymes. J Cell Biochem. 1982;18(1):67–85. doi: 10.1002/jcb.1982.240180107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Valk H. C., van Loon L. C. Subcellular Localization of Proteases in Developing Leaves of Oats (Avena sativa L.). Plant Physiol. 1988 Jun;87(2):536–541. doi: 10.1104/pp.87.2.536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Wilden W., Segers J. H., Chrispeels M. J. Cell Walls of Phaseolus vulgaris Leaves Contain the Azocoll-Digesting Proteinase. Plant Physiol. 1983 Nov;73(3):576–578. doi: 10.1104/pp.73.3.576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]