Abstract

Background

Tinnitus is described as the perception of sound or noise in the absence of real acoustic stimulation. In the current absence of a cure for tinnitus, clinical management typically focuses on reducing the effects of co‐morbid symptoms such as distress or hearing loss. Hearing loss is commonly co‐morbid with tinnitus and so logic implies that amplification of external sounds by hearing aids will reduce perception of the tinnitus sound and the distress associated with it.

Objectives

To assess the effects of hearing aids specifically in terms of tinnitus benefit in patients with tinnitus and co‐existing hearing loss.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Ear, Nose and Throat Disorders Group Trials Register; the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL); PubMed; EMBASE; CINAHL; Web of Science; Cambridge Scientific Abstracts; ICTRP and additional sources for published and unpublished trials. The date of the search was 19 August 2013.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials and non‐randomised controlled trials recruiting adults with subjective tinnitus and some degree of hearing loss, where the intervention involves amplification with hearing aids and this is compared to interventions involving other medical devices, other forms of standard or complementary therapy, or combinations of therapies, no intervention or placebo interventions.

Data collection and analysis

Three authors independently screened all selected abstracts. Two authors independently extracted data and assessed those potentially suitable studies for risk of bias. For studies meeting the inclusion criteria, we used the mean difference (MD) to compare hearing aids with other interventions and controls.

Main results

One randomised controlled trial (91 participants) was included in this review. We judged the trial to have a low risk of bias for method of randomisation and outcome reporting, and an unclear risk of bias for other criteria. No non‐randomised controlled trials meeting our inclusion criteria were identified. The included study measured change in tinnitus severity (primary measure of interest) using a tinnitus questionnaire measure, and change in tinnitus loudness (secondary measure of interest) on a visual analogue scale. Other secondary outcome measures of interest, namely change in the psychoacoustic characteristics of tinnitus, change in self reported anxiety, depression and quality of life, and change in neurophysiological measures, were not investigated in this study. The included study compared hearing aid use to sound generator use. The estimated effect on change in tinnitus loudness or severity as measured by the Tinnitus Handicap Inventory score was compatible with benefits for both hearing aids or sound generators but no difference was found between the two alternative treatments (MD ‐0.90, 95% confidence interval (CI) ‐7.92 to 6.12) (100‐point scale); moderate quality evidence. No negative or adverse events were reported.

Authors' conclusions

The current evidence base for hearing aid prescription for tinnitus is limited. To be useful, future studies should make appropriate use of blinding and be consistent in their use of outcome measures. Whilst hearing aids are sometimes prescribed as part of tinnitus management, there is currently no evidence to support or refute their use as a more routine intervention for tinnitus.

Plain language summary

Hearing aids for tinnitus in people with hearing loss

Background

Tinnitus describes 'ringing', 'whooshing' or 'hissing' sounds that are heard in the absence of any corresponding external sound. About 10% of people experience tinnitus and for some it has a significant negative impact on their quality of life. Tinnitus is commonly associated with some form of hearing loss and is possibly the result of hearing loss‐related changes in brain activity. It is logical to think, therefore, that providing people who have hearing loss and tinnitus with a hearing aid will not only improve their ability to hear sound but will also reduce their tinnitus symptoms. Hearing aids increase the volume at which people hear external sounds so this may help mask or cover up the tinnitus sound. They also improve communication, which may reduce the symptoms often associated with tinnitus such as stress or anxiety. Hearing aids may also improve tinnitus symptoms by reducing or reversing abnormal types of nerve cell activity that are thought to be related to tinnitus. The purpose of this review is to evaluate the evidence from high‐quality clinical trials that try to work out the effects hearing aids have on people's tinnitus. We particularly wanted to look at how bothersome their tinnitus is, how depressed or anxious tinnitus patients are and whether hearing aid use has an effect on patterns of brain activity thought to be associated with tinnitus.

Study characteristics

Our search identified just one randomised controlled trial which evaluated 91 participants who had tinnitus for at least six months and some degree of hearing loss. It compared those receiving hearing aids to those receiving sound generators. The average age of the patients was 38 and there were 40 women and 51 men. The study took place in two centres in Italy and the USA.

Key results

The result from the single study we reviewed was not definitive and was compatible with only small differences between the effect of hearing aids and sound generators. We also found another relevant study which has not yet been completed. We believe further high‐quality trials are needed.

Quality of the evidence

The quality of this evidence is moderate to low. This review is up to date to August 2013.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Hearing aids compared to sound generator for patients with tinnitus and co‐existing hearing loss.

| Hearing aids compared to sound generator for patients with tinnitus and co‐existing hearing loss | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with tinnitus and co‐existing hearing loss Settings: audiology Intervention: hearing aids Comparison: sound generators | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Sound generators | Hearing aids | |||||

| Tinnitus severity or handicap Measured by Tinnitus Handicap Inventory (scale range from 0 to 100) Follow‐up: mean 12 months | The mean change in the control group was ‐29.2 points | The mean change in the hearing aids group was 0.9 higher (6.12 lower to 7.92 higher) | 91 (1) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | In both groups the THI score reduced from a baseline of around 58. A higher (i.e. larger) reduction means a bigger improvement. A change of 20 points on the Tinnitus Handicap Inventory is considered clinically significant. |

|

| Tinnitus sound quality (loudness) Measured with a visual analogue scale (scale range from 0 to 10) | The mean change in the control group was ‐3.4 points | The mean change in the hearing aids group was 0 higher (0.64 lower to 0.64 higher) | 91 (1) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1 | Psychoacoustic measures could have been used to measure tinnitus sound quality. However, this was not reported and only VAS measures were available2. A higher score means 'worse'. | |

| Generalised anxiety ‐ not measured | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Generalised depression ‐ not measured | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Quality of life ‐ not measured | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Coping (style) ‐ not measured | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Neurophysiology changes ‐ not measured | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Adverse events of hearing aid fitting and use ‐ not measured | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| CI: confidence interval; THI: Tinnitus Handicap Inventory; VAS: visual analogue scale | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1A number of items are unclear or under‐reported. We were unable to get clarification about the conduct of the power calculation or the use of blinding. If there was no blinding, this is an important risk for subjective patient‐reported outcomes. The tinnitus questionnaire used is not sensitive to treatment‐related change.

2A VAS is not a considered a validated measure of loudness.

Background

Tinnitus is defined as the perception of sound in the absence of an external source (Jastreboff 2004). It is typically described by those who experience it as a ringing, hissing, buzzing or whooshing sound and is thought to result from abnormal neural activity at some point or points in the auditory pathway which is erroneously interpreted by the brain as sound. Tinnitus can be either objective or subjective. Objective tinnitus refers to the perception of sound that can also be heard by the examiner and is usually due to blood flow or muscle movement (Eggermont 2010). Most commonly, however, tinnitus is subjective; the sound is only heard by the person experiencing it and no source of the sound is identified (Jastreboff 1988).

Subjective tinnitus affects 10% of the general population, increasing to as many as 30% of adults over the age of 50 years (Davis 2000; Møller 2000). It can be experienced acutely, recovering spontaneously within minutes to weeks, but is considered chronic and unlikely to resolve spontaneously when experienced for three months or more (Hahn 2008; Hall 2011; Rief 2005).

In England alone there are an estimated ¾ million GP consultations every year where the primary complaint is tinnitus (El‐Shunnar 2011), equating to a major burden on healthcare services. For many people tinnitus is persistent and troublesome, and has disabling effects such as insomnia, difficulty concentrating, difficulties in communication and social interaction, and negative emotional responses such as anxiety and depression (Andersson 2009; Crönlein 2007; Marciano 2003). In approximately 90% of cases, chronic tinnitus is co‐morbid with some degree of hearing loss which may confound these disabling effects (Fowler 1944; Sanchez 2002). An important implication of this in clinical research, therefore, is that outcome measures need to distinguish benefits specific to improved hearing from those specific to tinnitus.

Description of the condition

Diagnosis and clinical management of tinnitus

There is no standard procedure for the diagnosis or management of tinnitus. Practice guidelines and the approaches described in studies of usual clinical practice typically reflect differences between the clinical specialisms of the authors or differences in the clinical specialisms charged with meeting tinnitus patients' needs (medical, audiology/hearing therapy, clinical psychology, psychiatry), or the available resources of a particular country or region (access to clinicians or devices, for example) (Biesinger 2010; Cima 2012; Department of Health 2009; Hall 2011; Henry 2008; Hoare 2011a). Common across all these documents, however, is the use or recommendation of written questionnaires to assess tinnitus and its impact on patients by measuring severity, quality of life, depression or anxiety. Psychoacoustic measures of tinnitus (pitch, loudness, minimum masking level) are also recommended. Although these measures do not correlate well with tinnitus severity (Hiller 2006) they can prove useful in patient counselling (Henry 2004) or by demonstrating stability of the tinnitus percept over time (Department of Health 2009).

Clinical management strategies include education and advice, relaxation therapy, tinnitus retraining therapy (TRT), cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), sound enrichment using ear‐level sound generators or hearing aids, and drug therapies to manage co‐morbid symptoms such as insomnia, anxiety or depression. The effects of these management options are variable and have few known risks or adverse effects (Dobie 1999; Hoare 2011; Hobson 2010; Martinez‐Devesa 2010; Phillips 2010).

Pathophysiology

Most people with chronic tinnitus have some degree of hearing loss (Ratnayake 2009) and the prevalence of tinnitus increases with greater hearing loss (Han 2009; Martines 2010). The varying theories of tinnitus generation involve changes in either function or activity of the peripheral (cochlea and auditory nerve) or central auditory nervous systems (Henry 2005). Theories involving the peripheral systems include the discordant damage theory which predicts that the loss of outer hair cell function, where inner hair cell function is left intact, leads to a release from inhibition of inner hair cells and aberrant activity (typically hyperactivity) in the auditory nerve (Jastreboff 1990). Such aberrant auditory nerve activity can also have a biochemical basis, resulting from excitotoxicity or stress‐induced enhancement of inner hair cell glutamate release with upregulation of N‐methyl‐D‐aspartate (NMDA) receptors (Guitton 2003; Sahley 2001).

In the central auditory system, structures implicated as possible sites of tinnitus generation include the dorsal cochlear nucleus (Middleton 2011; Pilati 2012), the inferior colliculus (Dong 2010; Mulders 2010), and the auditory and non‐auditory cortex (discussed further below). There is a strong rationale that tinnitus is a direct consequence of maladaptive neuroplastic responses to hearing loss (Møller 2000; Mühlnickel 1998). This process is triggered by sensory deafferentation and a release from lateral inhibition in the central auditory system allowing irregular spontaneous hyperactivity within the central neuronal networks involved in sound processing (Eggermont 2004; Rauschecker 1999; Seki 2003). As a consequence of this hyperactivity, a further physiological change noted in tinnitus patients is increased spontaneous synchronous activity occurring at the cortical level, measurable using electroencephalography (EEG) or magnetoencephalography (MEG) (Dietrich 2001; Tass 2012; Weisz 2005). Another physiological change thought to be involved in tinnitus generation is a process of functional reorganisation which amounts to a change in the response properties of neurons within the primary auditory cortex to external sounds. This effect is well demonstrated physiologically in animal models of hearing loss (Engineer 2011; Noreña 2005). Evidence in humans, however, is limited to behavioural evidence of cortical reorganisation after hearing loss, demonstrating improved frequency discrimination ability at the audiometric edge (Kluk 2006; McDermott 1998; Moore 2009; Thai‐Van 2002; Thai‐Van 2003), although Buss 1998 did not find this effect. For comprehensive reviews of these physiological models, see Adjamian 2009 and Noreña 2011.

It is also proposed that spontaneous hyperactivity could cause an increase in sensitivity or 'gain' at the level of the cortex, whereby neural sensitivity adapts to the reduced sensory inputs, in effect stabilising mean firing and neural coding efficiency (Noreña 2011; Schaette 2006; Schaette 2011). Such adaptive changes would be achieved at the cost of amplifying 'neural noise' due to the overall increase in sensitivity, ultimately resulting in the generation of tinnitus.

Increasingly, non‐auditory areas of the brain, particularly areas associated with emotional processing, are also implicated in bothersome tinnitus (Rauschecker 2010; Vanneste 2012). Vanneste 2012 describes tinnitus as "an emergent property of multiple parallel dynamically changing and partially overlapping sub‐networks", implicating the involvement of many structures of the brain more associated with memory and emotional processing in tinnitus generation. However, identification of the structural components of individual neural networks responsible for either tinnitus generation or tinnitus intrusiveness, which are independent of those for hearing loss, remains open to future research (Melcher 2012).

One further complication in understanding the pathophysiology of tinnitus is that not all people with hearing loss have tinnitus and not all people with tinnitus have a clinically significant hearing loss. Other variables, such as the profile of a person's hearing loss, may account for differences in their tinnitus report. For example, König 2006 found that the maximum slope within audiograms was higher in people with tinnitus than in people with hearing loss who do not have tinnitus, despite the 'non‐tinnitus' group having the greater mean hearing loss. This suggests that a contrast in sensory inputs between regions of normal and elevated threshold may be more likely to result in tinnitus.

Description of the intervention

The standard function of a digital hearing aid is to amplify and modulate sound, primarily for the purpose of making sound more accessible and aiding communication. Using hearing aids in tinnitus management has been proposed as a useful strategy since the 1940s (Saltzman 1947), although the benefit reportedly varies and there is no clear consensus on when a person would or would not benefit from amplification (Henry 2005; Hoare 2012). Beck 2011 proposes that hearing aid fittings for people with very mild up to moderate sensorineural hearing loss (who might not ordinarily look for or be prescribed a hearing aid) can lead to significant improvements in tinnitus. Currently, hearing aids, supplemented with education and advice, form a common intervention for someone who has tinnitus and an aidable hearing loss (Hoare 2012). This combination of hearing aid provision with education and advice might be considered a complex intervention with interdependent components (Shepperd 2009).

There are many options for hearing aid fitting which complicate their use in tinnitus. For example, Del Bo 2007 suggests that the best clinical result for someone with tinnitus requires bilateral rather than monolateral amplification. Trotter 2008, however, in describing a 25‐year experience of hearing aids in tinnitus therapy, found no difference in tinnitus improvement between unilaterally and bilaterally aided patients. For other aspects of hearing aid fitting there appears to be greater consensus; for example, the value of using open‐fitting aids, which allow natural environmental sound to enter the ear, as well as amplifying those sounds, thus improving perceived sound quality (Del Bo 2007; Forti 2010).

The effect of amplification on tinnitus may be in part determined by the degree to which different frequencies are amplified by the hearing aid. Moffat 2009 examined the effect of amplification on objectively measured tinnitus pitch characteristics. The authors compared the effects of two very distinct amplification gain profiles in patients with a dominant tinnitus pitch that was typically above or equal to 4 kHz. A 'standard amplification' group received gain that was limited to the low and medium ends of the audible spectrum (with minimal amplification above 4 kHz). One month after fitting there was a significant reduction in the contributions of low frequencies (250, 500 and 750 Hz) to the tinnitus pitch percept. A 'high‐bandwidth amplification' group received gain that provided enhanced audibility at 4 to 6 kHz. One month after fitting there was no change in tinnitus pitch characteristics. In contrast, Schaette 2010 examined the effect of amplification on self reported benefits. Their study addressed the influence of dominant tinnitus pitch on outcome in patients receiving 'standard amplification'. Pilot results indicated a significant reduction in tinnitus severity and loudness in those participants whose dominant tinnitus pitch fell within the stimulated frequency range of the device (i.e. less than 6 kHz), but not in those whose dominant tinnitus pitch was 6 kHz or more. Since neither study measured both tinnitus pitch characteristics and self reported benefits, the link between these two outcomes requires further investigation.

Finally, hearing aid prescription might also be combined with other forms of therapy, such as formal counselling, albeit with mixed evidence for the effects of such combinations of therapies (Hiller 2005; Hobson 2010; Phillips 2010; Searchfield 2010).

How the intervention might work

Hearing aids may be beneficial for people with tinnitus in a number of ways. The amplification of external sounds may reverse or reduce the drive responsible for 'pathological' changes in the central auditory system associated with hearing loss, such as increased gain or auditory cortex reorganisation, possibly by strengthening lateral inhibitory connections. Increased neuronal activity that results from amplified sounds may reduce the contrast between tinnitus activity and background activity thus reducing audibility and the awareness of tinnitus. Alternatively, amplification may simply refocus attention on alternative auditory stimuli that are incompatible and unrelated to the tinnitus sound. The primary purpose of fitting a hearing aid is to reduce hearing difficulties and improve communication (Dillon 2012), which for some people should reduce the stress and anxiety that may be associated with their hearing difficulties (Surr 1985). This may lead to changes in self reported measures of tinnitus handicap which contain questions on tinnitus‐related stress or anxiety. Finally, there is likely to be the potential for a large placebo effect in any study of tinnitus (Dobie 1999) and so it is essential that any investigation of hearing aids for tinnitus considers the potential impact of this effect.

Why it is important to do this review

This review is important because 1) hearing aids are a recommended intervention if an individual has bothersome tinnitus and some hearing loss, 2) the evidence base which supports current clinical practice has not been systematically collated and 3) this is a rapidly evolving field. Hearing aid technology is ever advancing, with increasing emphasis on open‐fitting aids, greater bandwidths of amplification (up to 10 kHz), better feedback cancellation techniques and signal processing programs, and the combination of a hearing aid with a tinnitus masker or sound generator in a single digital device (Forti 2010; Sweetow 2010). There has never been a dedicated systematic review on the specific effects of amplification on tinnitus. This review is important, therefore, not only as a synthesis of the data that currently exist on the use of hearing aids as an intervention in tinnitus management, but as a working document that can set and forecast important questions on the topic.

Objectives

To assess the effects of hearing aids specifically in terms of tinnitus benefit in patients with tinnitus and co‐existing hearing loss.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

In the protocol for this review we anticipated including both randomised and non‐randomised studies. In this review we have clarified this as follows. The 'non‐randomised studies' we planned to include were those conducted in a very similar manner to RCTs, but with an inadequate randomisation technique (quasi‐randomised trials) or where allocation was not randomised (non‐randomised controlled trials). Cluster‐randomised trials would also be included. Features of these trials are as defined in Table 13.2a of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Handbook 2011).

Specifically, non‐randomised controlled trials would only be included if:

hypotheses, identification of participants, baseline and outcome measurements are pre‐defined, i.e. trials are prospective;

the primary design was selected to make a between‐group and not a within‐group controlled comparison; and

participants were allocated by an action of the researcher (Handbook 2011).

For inclusion we also required the primary question of the non‐randomised controlled trial to reflect that of the review (Wells 2013) and so inform recommendations for future relevant trials.

Types of participants

Adults (18 years and above) with subjective tinnitus and some degree of hearing loss.

Types of interventions

Studies were included where patients with tinnitus received a hearing aid (with any standard educational/informational support) and this was compared to either care involving other medical devices, other forms of standard or complementary therapy or combinations of therapies, no intervention or placebo interventions. Where available, we report details of the fitting procedure and type of hearing aid used.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Tinnitus severity or handicap, measured as a change between baseline (pre‐hearing aid fitting) and follow‐up compared to a control, using a tinnitus questionnaire listed in Table 2. This list will be updated on an ongoing basis whenever other questionnaires are validated.

1. Tinnitus questionnaires.

| Questionnaire (author) | Range, number of items, subscales | Psychometric properties | Clinically significant change score |

| Tinnitus Handicap Inventory (Newman 1996) | 0 to 100, 25 items, 3 subscales | a = 0.93 for total scale | 20 points |

| Tinnitus Functional Index (Meikle 2012) | 0 to 100, 25 items, 8 subscales | a = 0.97 for total scale | 13 points |

| Tinnitus Handicap Questionnaire (Kuk 1990) | 0 to 100, 27 items, 3 subscales | a = 0.93 for total scale | Not known |

| Tinnitus Questionnaire (Goebel 1994; Hallam 1996) | 0 to 84, 52 items, 5 subscales | a = 0.91 for total scale; for subscales a = 0.76 to a = 0.94 | 5 points |

| Tinnitus Reaction Questionnaire (Wilson 1991) | 0 to 104, 26 items, 4 subscales | a = 0.96 and a test‐retest correlation of r = 0.88 | Not known |

| Tinnitus Severity Index (Meikle 1995) | 12 to 56, 12 items, no subscales | Not reported | Not known |

Secondary outcomes

Generalised anxiety

Generalised depression

Quality of life

Coping (style)

All measured as change (from baseline) using validated questionnaires.

Tinnitus sound quality (e.g. dominant pitch, loudness), measured as changes in psychoacoustic measures

Neurophysiology changes (e.g. change in neural activity as measured by functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), electroencephalography (EEG), magnetoencephalography (MEG) etc.)

Adverse effects of hearing aid fitting and use

The use of appropriate outcomes and outcome measures (i.e. how the outcomes were measured) is particularly important tinnitus research. Both selective outcome reporting and detection bias are important issues that we will consider in this review.

Search methods for identification of studies

We conducted systematic searches for randomised controlled trials and controlled clinical trials. There were no language, publication year or publication status restrictions. The date of the search was 19 August 2013.

Electronic searches

We searched the following databases from their inception for published, unpublished and ongoing trials: the Cochrane Ear, Nose and Throat Disorders Group Trials Register; the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL, The Cochrane Library 2013, Issue 7); PubMed; EMBASE; CINAHL; AMED; LILACS; KoreaMed; IndMed; PakMediNet; CAB Abstracts; Web of Science; ISRCTN; ClinicalTrials.gov; ICTRP; Google Scholar and Google. In searches prior to 2013, we also searched BIOSIS Previews 1926 to 2012.

We modelled subject strategies for databases on the search strategy designed for CENTRAL. Where appropriate, we combined subject strategies with adaptations of the highly sensitive search strategy designed by The Cochrane Collaboration for identifying randomised controlled trials and controlled clinical trials (as described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0, Box 6.4.b. (Handbook 2011)). Search strategies for major databases, including CENTRAL, are provided in Appendix 1.

Searching other resources

We supplemented the electronic searches with searches of all the research studies included in a current scoping review (Shekhawat 2013) and the reference list of the included study.

We searched for conference abstracts using the Cochrane Ear, Nose and Throat Disorders Group Trials Register.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Three authors (DJH, DH, MAA) independently reviewed all articles retrieved to determine their eligibility for inclusion in the review. We considered multiple articles reporting the same study together as a single record. Disagreements were discussed between all three authors until a consensus was reached. We contacted authors of studies where there was insufficient information to evaluate eligibility for inclusion.

Data extraction and management

Two authors (MEJ, MS) independently extracted data using a data extraction form designed specifically for the review, which was piloted on a subset of articles and revised as appropriate before formal data extraction began.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two authors (MS, MEJ) independently assessed the risk of bias of the included trials, with the following taken into consideration, as guided by theCochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Handbook 2011):

sequence generation;

allocation concealment;

blinding;

incomplete outcome data;

selective outcome reporting; and

other sources of bias, such as the use of patient‐reported outcome measures with insufficient validity and sensitivity to detect changes.

For the assessment of RCTs we used the Cochrane 'Risk of bias' tool in RevMan 5.2 (RevMan 2012), which involves describing each of these domains as reported in the trial and then assigning a judgement about the adequacy of each entry: 'low', 'high' or 'unclear' risk of bias.

Measures of treatment effect

If data were available, we planned to analyse dichotomous data as risk ratios (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs).

We analysed outcomes measured using scales as continuous outcomes. Continuous outcomes are summarised as mean difference (MD) with 95% CI. We also planned to use standardised mean difference (SMD), also known as Cohen's d effect size (ES), particularly when different scales were used to measure an outcome.

Unit of analysis issues

We anticipated the following unit of analysis issues in this review:

the unit of randomisation was at the group level, i.e. cluster‐randomised trials;

multiple observations were made for the same outcome (e.g. repeated measurements) at different time points.

If appropriate studies had been identified, we would have used data extraction and analysis techniques which take into account the effect of clustering, as recommended in Chapter 16 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Handbook 2011). To minimise the issue of repeated measurement of data, we would only incorporate data at the most relevant time points rather than analysing each time point reported by the included studies.

Dealing with missing data

In line with the recommendations contained in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Handbook 2011), where possible we planned to contact the original investigators to request missing data. In this review some values were not reported in the text but sufficient information was presented in the report diagrams and figures. It is clearly stated throughout the review where estimation was used.

Assessment of heterogeneity

In addition to statistical heterogeneity, we would have considered the issue of clinical heterogeneity (in terms of patient population, intervention, comparison and how outcomes were measured) before we made any decision to pool the data and in the description of results.

If more than one study was found and included in the meta‐analysis, we would have visually inspected forest plots for the presence of heterogeneity. We would also have used formal statistical tests: Cochran's Q statistic (Chi2 test with K‐1 degrees of freedom, where K is the number of studies) and the I2 statistic. We would have considered statistical heterogeneity to be present if the P value of the Chi2 test was 0.1 or the I2 value was 50% or higher (Handbook 2011).

Assessment of reporting biases

We planned to investigate potential publication bias and the influence of individual studies on the overall outcome of this review using a funnel plot (Egger 1997). However, there were insufficient studies included to make this analysis meaningful. Other aspects of reporting bias were assessed as part of the selective (outcome) reporting 'Risk of bias' assessment. Our search strategy also included key trial registries and any studies completed with unpublished results would have been noted.

Data synthesis

If more than one study had been identified and if combining studies was appropriate we had planned to use RevMan 5.2 (RevMan 2012) to perform meta‐analysis. With just one included study, however, we analysed data to support a narrative synthesis that reports both statistical and clinical significance levels. We had planned to pool data from randomised controlled trials using a fixed‐effect model, except when heterogeneity was found. We planned to pool dichotomous data using the RR measure, while continuous data were to be pooled using the standardised mean difference (SMD) measure if more than scale or questionnaire was used to measure the same outcome. We would have given consideration to the psychometric properties of the questionnaire with regard to the suitability for pooling.

This review planned to include data from both RCTs and non‐RCTs. However, we planned to analyse these studies separately according to the recommendations of the Cochrane Non‐Randomised Studies Methods Group, to take into account issues relating to confounders and heterogeneity of data (Valentine 2013).

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Where appropriate the following potential sources of heterogeneity are discussed: age, sex, hearing loss (pure‐tone average), baseline tinnitus severity, baseline hearing handicap, baseline level of anxiety or depression.

Sensitivity analysis

We planned to perform a sensitivity analysis to explore whether any significant heterogeneity was a result of low trial quality. We planned to exclude the lowest quality trials if appropriate.

Results

Description of studies

See: Characteristics of included studies; Characteristics of excluded studies.

Results of the search

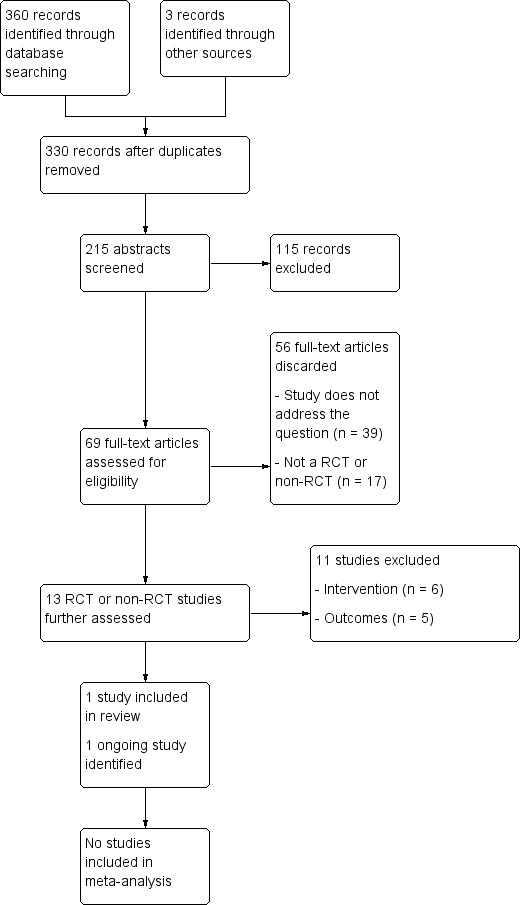

Our electronic database search on 19 August 2013 identified 360 records. A further three records were identified from a handsearch of the one study included in this review and a newly published scoping review (Shekhawat 2013). After the removal of duplicates, we were left with 330 records. We discarded 115 records and retrieved 215 abstracts for assessment. Following screening of these we retrieved 69 full‐text papers. From these we discarded 39 as they did not address the research question (for example, 19 were tinnitus review articles). From the remaining 30, we discarded a further 17 as they were not RCT or non‐RCT study designs. We formally excluded 11 RCT or non‐RCT studies as they either did not test a relevant intervention or control, or they did not use a tinnitus questionnaire as an outcome measure.

Just one completed study met our inclusion criteria (Parazzini 2011). We identified one further ongoing study which could potentially meet our criteria for inclusion when published (NCT01857661).

No studies comparing hearing aids to no intervention or to a placebo intervention were identified.

See Figure 1 for a flow chart showing the search process for the search. Those RCTs and non‐RCTs that we formally excluded are listed in Characteristics of excluded studies, with details of the reason for exclusion.

1.

Process for sifting search results and selecting studies for inclusion.

Included studies

We included one study in the review (Parazzini 2011). This study examined the effects of hearing aid use on tinnitus, compared to the effects of a sound generator device, and used a questionnaire to measure tinnitus handicap. It also used a visual analogue scale (VAS) of tinnitus loudness.

Design

Parazzini 2011 was a two‐centre, randomised, controlled (parallel), repeated‐measures trial.

Sample size

One hundred and one patients were enrolled, but due to missing records the final data set included only 91 patients.

Setting

Patients were screened and treated in one of two tinnitus clinics (Italy or USA).

Participants

Group level data for age, duration of tinnitus and hearing loss were not provided by Parazzini 2011. The 91 patients included in the final analysis had a mean age of 38.8 years (SD 18.1) and a mean tinnitus duration of 69.5 months (SD 89.7). Baseline measures included an audiological test for hearing loss. Mean hearing loss was not reported per group but inclusion in the study required patients to have hearing levels < 25 dB at 2 kHz and > 25 dB at frequencies higher than 2 kHz. This was taken as the borderline between two categories: 'no hearing loss' and 'significant hearing loss'. According to Jastreboff 2004, patients with this hearing level can be managed with either hearing aids or sound generators. The participants in this study therefore had a very particular audiological profile. Patients who had previously been prescribed hearing aids were excluded from participation in the trial.

Group level data for gender and baseline tinnitus severity were provided by Parazzini 2011 and groups were comparable on both variables. The group who received hearing aids included 21 women and 28 men, and the group receiving sound generators included 19 and 23 men. The mean Tinnitus Handicap Inventory (THI) score at baseline was 57 for the hearing aid group and 59 for the sound generator group.

Interventions

One group were fitted with bilateral open ear hearing aids (n = 49) and one group were fitted with bilateral sound generators (n = 42). All hearing aid patients were fitted with the 'ResoundAir' device (GN Resound), programmed according to standard audiological practice. In terms of the type of sound generators, all patients were fitted with behind‐the‐ear open fit 'Silent Star' devices (Viennatone) which produce a broadband sound. All patients received the same educational counselling component of tinnitus retraining therapy (TRT), with follow‐up to optimise the therapy at three, six and 12 months.

Outcomes

Change in tinnitus symptoms was measured using the Tinnitus Handicap Inventory (Table 2; Newman 1996). A number of visual analogue scales were used to rate tinnitus loudness over the preceding month (rated from 0 = no tinnitus to 10 = 'as loud as you can imagine'), effect on life, tinnitus annoyance, percentage of time when patients were annoyed and percentage of time when patients were aware of their tinnitus. Outcomes were measured at three, six and 12 months during the tinnitus treatment.

Excluded studies

See: Characteristics of excluded studies for details of the 11 RCTs and non‐RCTs excluded because of the intervention or control they used (n = 6) or because of the outcome measures they used (n = 5) (dos Santos Ferrari 2007; Eysel‐Gosepath 2004; Forti 2010; Hazell 1985; Henry 2006; Kießling 1980; Mehlum 1984; Melin 1987; Moffat 2009; Oz 2013; Schaette 2010).

Risk of bias in included studies

Two authors (MS, MEJ) critically reviewed study methodology and graded the quality of the study according to the stated criteria. We contacted the lead author of the included study on two occasions to ask for more details of their methodology where risk of bias was unclear, however we had not received a response at the time of submission. For a summary of the risk of bias in this study see Figure 2.

2.

'Risk of bias' summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for the included study.

Allocation

The authors of Parazzini 2011 state that "Randomization was obtained on the basis of a random table". From this it is unclear whether investigators were aware of allocation before enrolment, so we judged selection bias to be unclear.

Blinding

The use of blinding was not reported so the risk of performance bias is unclear. Outcome measurement involved self reported questionnaires. Whether or not there was blinding of researchers was not reported, again representing an unclear risk of detection bias.

Incomplete outcome data

We judged Parazzini 2011 to have a low risk of attrition bias. They excluded participants from both groups after randomisation because of lost records rather than any systematic exclusion process. The loss of outcome data in all cases was due to a single reason and was similar across groups.

Selective reporting

We judged Parazzini 2011 to have a low risk of selective reporting bias. Although psychoacoustic measures of tinnitus loudness and pitch were collected at baseline and not repeated at follow‐up, the most clinically meaningful measures were repeated at follow‐up.

Other potential sources of bias

Parazzini 2011 conducted a power analysis but the authors do not report the basis for this. They included 91 participants in the study although only 80 were required for adequate statistical power. No justification was given. We judged the study to be at low risk for other potential sources of bias.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

Hearing aids versus sound generator device

The included randomised controlled trial (RCT) (Parazzini 2011) compares hearing aids for tinnitus management versus a sound generator device, hence this is the only comparison which can be analysed in this review.

Primary outcome measure

Tinnitus severity or handicap, measured as a change between baseline (pre‐hearing aid fitting) and follow‐up

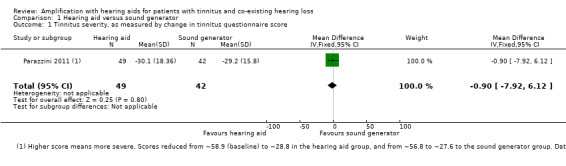

Parazzini 2011 reported no statistically significant difference in the change in tinnitus handicap between groups. Tinnitus Handicap Inventory (THI) scores were assessed at 12 months. We estimated mean values from the data plots (in Figure 1 of their paper). For patients who were fitted with a hearing aid, the THI score reduced from ˜58.9 to ˜28.8 (the questionnaire range is 0 to 100), whereas the group who received sound generators reported a reduction from ˜56.8 to ˜27.6. Parazzini 2011 performed a two‐way ANOVA showing that the reduction in THI was statistically significant overall (P < 0.001), but there was no significant difference between groups (mean difference (MD) ‐0.90, 95% confidence interval (CI) ‐7.92 to 6.12; standardised mean difference (SMD) 0.05, 95% CI ‐0.36 to 0.46) (Analysis 1.1). The reduction in THI score seen in both groups was clinically significant (i.e. more than 20 points, Newman 1996).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Hearing aid versus sound generator, Outcome 1 Tinnitus severity, as measured by change in tinnitus questionnaire score.

Secondary outcome measures

Generalised anxiety

Parazzini 2011 did not include any outcome measures of generalised anxiety.

Generalised depression

Parazzini 2011 did not include any outcome measures of generalised depression.

Quality of life

Parazzini 2011 did not include any outcome measures of generalised quality of life.

Coping (style)

Parazzini 2011 did not include any outcome measures of coping.

Tinnitus sound quality (e.g. dominant pitch, loudness), measured as changes in psychoacoustic measures

Parazzini 2011 did not perform psychoacoustic measurement of tinnitus.

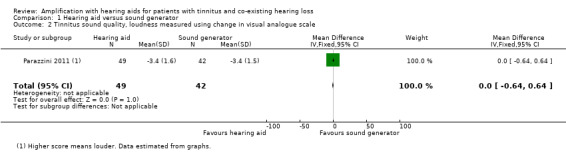

Both groups reported a reduction in tinnitus loudness using a visual analogue scale (VAS) score at 12 months follow‐up, but this did not differ significantly between groups (SMD 0, 95% CI ‐0.64 to 0.64) (Analysis 1.2).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Hearing aid versus sound generator, Outcome 2 Tinnitus sound quality, loudness measured using change in visual analogue scale.

Neurophysiology changes

Parazzini 2011 did not measure neurophysiology changes.

Adverse effects of hearing aid fitting and use

Neither a plan to measure adverse effects nor the occurrence of adverse effects was reported by Parazzini 2011.

Discussion

Summary of main results

The objective of this review was to evaluate the effects of amplification with hearing aids in patients with tinnitus and a co‐existing hearing loss.

We found no evidence relating to the comparison of hearing aids with placebo or no intervention.

For the comparison of hearing aids versus sound generators, only one small RCT met the inclusion criteria. The included RCT found no difference between the effect of hearing aids and sound generators on the change in self reported tinnitus handicap or VAS scores of tinnitus loudness. The use of both was associated with a clinically significant reduction in tinnitus handicap. In summary, hearing aids were not better or worse than sound generators. No evidence was found for the other outcomes of interest in this review. See Table 1.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

This review found evidence from one small RCT for two outcomes measured using self reported measures, i.e. change in tinnitus questionnaire scores for tinnitus severity or VAS for tinnitus loudness, in a patient population who might receive the intervention in practice.

The study was conducted on a clinical population, making the findings on the face of it externally valid. However, the participants had a very specific audiological profile, representing a group with a specific type and degree of hearing loss. It is not clear whether or not the findings are equally applicable to patients with more severe hearing loss.

We found no evidence comparing hearing aids with either placebo or no intervention.

Quality of the evidence

We consider the quality of evidence for the main outcome to be moderate, i.e. further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. There are some important limitations in the design and conduct of the study. The report of the included study (Parazzini 2011) did not provide any information about blinding and therefore this is a concern as subjective patient‐reported outcomes were used. In addition, the choice of outcome measure (Tinnitus Handicap Inventory) used to measure tinnitus severity was not originally developed as an outcome measure. It uses a scoring system that is not sensitive to small treatment‐related changes (Meikle 2008). Key properties for any outcome instrument are content validity, reproducibility and responsiveness (Terwee 2007).

Psychoacoustic measures of tinnitus pitch or loudness were collected at baseline but were not used as outcome measures (Parazzini 2011). It is unclear whether or not this results in selective reporting bias. However, the study reported tinnitus loudness based on a VAS scale.

As we found only one RCT, the overall number of participants available for data analysis was relatively small. Although the authors of the included study had conducted a power calculation, they provided little detail about this and recruited beyond it (80 participants required for power but 101 participants recruited in the first instance, and 91 participants reported). The rationale behind this is not clear. As the confidence intervals did not exceed minimum clinically important differences, we made no further downgrading for imprecision.

Potential biases in the review process

Our searches of electronic databases and journal websites were comprehensive. We also searched the reference list of the included study and a current scoping review (Shekhawat 2013). Language was not a barrier to inclusion and a number of German articles were translated in house for inclusion assessment. Author roles in the review process were pre‐defined in the protocol; three authors independently selected studies for inclusion and two authors extracted data and judged risk of bias. Risk of publication bias was not formally assessed as only one study met the criteria for inclusion. To be included in the review, studies had to report the primary outcome measure using a self reported questionnaire. A number of studies were excluded, therefore, which measured some secondary outcomes of interest but not this primary outcome. This may have resulted in some bias in the reviewing of secondary outcomes.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

This is the first systematic review to examine exclusively the effects of amplification with hearing aids on tinnitus. However, studies involving hearing aids have appeared in previous systematic reviews. The Cochrane review of masking (Hobson 2010) cites one comparable study from Hazell 1985 where the use of hearing aids or sound generators within tinnitus retraining therapy was compared. This clinical study was excluded from this review as it did not involve the use of a tinnitus questionnaire. Rather, they used a self devised 'masker‐effectiveness questionnaire'. As was found here, Hazell 1985 reported no difference in the therapeutic effect of using hearing aids or sound generators. Hoare 2011 reviewed Stephens 1985 (a randomised sub‐study within Hazell 1985) which also did not report using a questionnaire of tinnitus severity and so was excluded from the current review. Stephens 1985 reported no significant difference between groups in what they termed 'psychological' measures of tinnitus. Our conclusion that hearing aids and sound generators are equally effective for tinnitus in a population with some hearing loss is therefore consistent with the conclusions of this earlier work.

Evidence for the effects of hearing aids compared to the option of not using one is limited to cohort studies and surveys (see Shekhawat 2013 for a scoping review) and has not been addressed in any previous systematic review.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Hearing aids are one of a number of therapeutic options offered to tinnitus patients. However, there is currently no evidence to support or refute the provision of hearing aids as a primary intervention in the management of tinnitus in patients with co‐existing hearing loss. Provision of hearing aids for tinnitus will always have the potential consequence of reducing the distress associated with hearing loss and so any clinical improvement that is specific to tinnitus will always be difficult to estimate accurately. We identified evidence of limited quality that for patients with a particular audiological profile hearing aids seem to be as beneficial as sound generators. They may in some cases be a better option on the grounds that amplification may for some patients be more acceptable and useful than the broadband or patterned sound stimuli delivered by sound generators (Hoare 2013).

Implications for research.

Future research should aspire to produce high‐quality evidence from well‐conducted RCTs which report findings to recognised standards, such as the CONSORT statement (Schulz 2010). The choice of outcomes measured in trials also needs to be carefully considered. A recent proposal for international standards for tinnitus trials (Landgrebe 2012) considers a comprehensive outcome assessment of tinnitus to include psychoacoustic measures or ratings of loudness and annoyance as well as questionnaires measuring tinnitus impact. We recommend the use of the Tinnitus Functional Index (TFI) as a core outcome measure (Meikle 2012) as it was developed to be sensitive to treatment‐related changes, unlike many tinnitus questionnaires currently in use. The TFI also sets a benchmark of what constitutes a clinically significant benefit, that is a reduction of 13 points on this 0 to 100 scale. Psychoacoustic outcome measures are also important. A case in point is seen in one of the studies excluded from this review (Schaette 2010). The conclusions in this study relate to a grouping of participants according to psychoacoustic estimates of tinnitus pitch made at baseline. Pitch was not re‐evaluated at follow‐up so their conclusion hinged on the assumption that it was stable throughout the study. As far as is feasible, future studies should routinely include psychoacoustic measures of tinnitus at study endpoints.

The single study included in this review makes one comparison (hearing aids or sound generators) for a pre‐defined subset of patients (those with hearing loss at higher frequencies) and finds no between‐group difference in outcome. It remains open to future studies to determine whether, for given populations of help‐seeking tinnitus patients, the provision of a hearing aid is superior to an education‐only intervention, no intervention (waiting list control) or to a hearing aid placebo (where a hearing aid gain is set to overcome the effects of any occlusion due to the device fitting only, with zero amplification above the normal threshold). In terms of efficacy, an important question is whether or not patients with only mild hearing loss or high‐frequency hearing loss should routinely be offered a hearing aid. Parazzini 2011, however, compared hearing aid and sound generator use in patients who might reasonably be managed with either device, i.e. patients with tinnitus, normal hearing at lower frequencies (< 25 dB HL at 2 kHz) and some hearing loss at higher frequencies. This patient group may or may not report hearing difficulties as a primary complaint. The effects of amplification on this patient population lends itself to a placebo‐controlled RCT in a way that would be less appropriate to patient populations who have severe co‐morbid hearing loss.

Future trials should also consider, whilst controlling for hearing loss, randomising hearing aid features that maximise hearing benefit, such as noise reduction settings, environmental steering, compression and wide dynamic range, to provide evidence about which features contribute to or reduce the tinnitus benefit a patient may experience.

Acknowledgements

The original database searches were performed by Samantha Faulkner from the Cochrane Ear, Nose and Throat Disorders Group. Dr Michal Sereda was funded through a NIHR Cochrane Incentive Award to provide administration support for this review, including the translation of articles published in German. Thanks to Lee Yee Chong for advice on the 'Summary of findings' table.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Search strategy

| CENTRAL | PubMed | EMBASE (Ovid) | CINAHL (EBSCO) |

| #1 MeSH descriptor Tinnitus explode all trees #2 tinnit* #3 #1 OR #2 #4 MeSH descriptor Hearing Aids explode all trees #5 MeSH descriptor Prosthesis Fitting explode all trees #6 "hearing aid*" #7 "ear mold*" OR earmold* #8 "ear mould*" OR earmould* #9 amplification #10 #4 OR #5 OR #6 OR #7 OR #8 OR #9 #11 #3 AND #10 | #1 Search "Tinnitus"[Mesh] #2 Search tinnit* #3 Search #1 OR #2 #4 Search "Hearing Aids"[Mesh] #5 Search "Prosthesis Fitting"[Mesh] #6 Search "hearing aid*" #7 Search "ear mold*" OR earmold* #8 Search "ear mould*" OR earmould* #9 Search amplification #10 Search #4 OR #5 OR #6 OR #7 OR #8 OR #9 #11 Search #3 AND #10 | 1 exp tinnitus/ 2 "tinnit*".tw. 3 1 or 2 4 exp hearing aid/ 5 exp prosthesis/ 6 "hearing aid* ".tw. 7 ("ear mold*" or earmold*).tw. 8 ("ear mould*" or earmould*).tw. 9 amplification.tw. 10 4 or 5 or 6 or 7 or 8 or 9 11 3 and 10 |

S1 (MH "Tinnitus") S2 TX tinnit* S3 S1 or S2 S4 (MH "Hearing Aids+") S5 (MH "Prosthetic Fitting") S6 TX "hearing aid*" S7 TX "ear mold*" OR earmold* S8 TX "ear mould*" OR earmould* S9 TX amplification S10 S4 or S5 or S6 or S7 or S8 or S9 S11 S3 and S10 |

| CAB Abstracts (Ovid) | Web of Science | AMED (Ovid) | ISRCTN (mRCT) |

| 1 tinnit*.tw. 2 "hearing aid*".tw. 3 ("ear mold*" or earmold*).tw. 4 ("ear mould*" or earmould*).tw. 5 amplification.tw. 6 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 7 1 and 6 |

#1 TS=tinnit* #2 TS="hearing aid*" #3 TS=("ear mold*" or earmold*) #4 TS=("ear mould*" or earmould*) #5 TS=amplification #6 #2 OR #3 OR #4 OR #5 #7 #6 AND #1 | 1 exp Tinnitus/ 2 tinnit*.tw. 3 1 or 2 4 exp Hearing aids/ 5 exp Prosthesis/ 6 "hearing aid*".tw. 7 ("ear mold*" or earmold*).tw. 8 ("ear mould*" or earmould*).tw. 9 amplification.tw. 10 4 or 5 or 6 or 7 or 8 or 9 11 3 and 10 |

Tinnitus AND (amplification OR “hearing aid” OR “hearing aids”) |

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Hearing aid versus sound generator.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Tinnitus severity, as measured by change in tinnitus questionnaire score | 1 | 91 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.90 [‐7.92, 6.12] |

| 2 Tinnitus sound quality, loudness measured using change in visual analogue scale | 1 | 91 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [‐0.64, 0.64] |

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Parazzini 2011.

| Methods |

Allocation: randomised Design: a 2‐centre, controlled (parallel), repeated‐measures trial |

|

| Participants |

Number: 91 participants (49 intervention, 42 control) Age: mean age = 38.8 (± 1.9) years Gender: 40 women and 51 men Setting: patients were evaluated and treated within 2 tinnitus clinics in Milan and Baltimore Eligibility criteria: i) aged 18 to 75 years ii) tinnitus duration at least 6 months iii) borderline between category 1 and 2 (according to the Jastreboff classification, with hearing loss ≤ 25 dB at 2 kHz and HL ≥ 25 dB at frequencies above 2 kHz iv) bilateral symmetrical hearing loss (difference < 15 dB) Exclusion criteria: tinnitus arising from external ear disease, middle ear disease or Ménière's disease Baseline characteristics: at initial appointment, mean score on Tinnitus Handicap Inventory = 58, tinnitus loudness = 7, effect on life = 6.6, tinnitus annoyance = 7.1, percentage of time when participants were annoyed = 47.0, percentage of time when participants were aware = 70.1 |

|

| Interventions |

Intervention: tinnitus retraining therapy with hearing aid(s) Control: tinnitus retraining therapy with sound generator(s) |

|

| Outcomes | Tinnitus Handicap Inventory (THI range 0 to 100) Tinnitus loudness (VAS range 0 to 10) Effect on life (VAS range 0 to 10) Tinnitus annoyance (VAS range 0 to 10) Percentage of time when participants were annoyed (VAS range 0 to 100) Percentage of time when participants were aware (VAS range 0 to 100) |

|

| Notes | Outcomes were measured at the 3, 6 and 12‐month follow‐up appointments | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | "Randomization was obtained on the basis of a random table." (Parazzini 2011 p549) |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | No blinding, but unclear about the consequent risk of bias |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | None apparent |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Some participants' data were excluded due to missing records. "A sample of 101 subjects passed the screening criteria and was tested across centers. However, due to missing recordings in some subjects, the final pooled data set consisted of 91 subjects…" (Parazzini 2011 p552) Tinnitus annoyance, percentage of time when participants were annoyed and percentage of time when participants were aware of tinnitus were analysed for 51 participants only (29 with hearing aids and 22 with sound generators). "These variables were recorded only from a subset of all the subjects involved in the study...." (Parazzini 2011 p552) |

| Other bias | Low risk | None apparent |

THI: Tinnitus Handicap Inventory VAS: visual analogue scale

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| dos Santos Ferrari 2007 | ALLOCATION Randomised controlled trial PARTICIPANTS Adults with tinnitus and hearing loss INTERVENTIONS Behind‐the‐ear hearing aids with open moulds versus behind‐the‐ear hearing aids with pressure‐vented ear moulds |

| Eysel‐Gosepath 2004 | ALLOCATION Randomised controlled trial PARTICIPANTS Adults with tinnitus and hearing loss INTERVENTIONS Hearing aids or sound generators using music and environmental sounds as distraction versus no device using 'light and warmth' as distraction, both with counselling and relaxation training |

| Forti 2010 | ALLOCATION Non‐randomised controlled trial PARTICIPANTS Adults with tinnitus and hearing loss INTERVENTION Open ear canal hearing aids versus 'classical' hearing aids, no control for amplification |

| Hazell 1985 | ALLOCATION Non‐randomised controlled trial PARTICIPANTS Adults with tinnitus and hearing loss INTERVENTION Hearing aids versus combination devices versus sound generators OUTCOME MEASURE No questionnaire measure of tinnitus severity or handicap, used Crown‐Crisp Experiential Index, 'masker effectiveness questionnaire', 7 'semantic differential questions', minimum masking level and tinnitus loudness |

| Henry 2006 | ALLOCATION Non‐randomised controlled trial PARTICIPANTS Adults with tinnitus and hearing loss INTERVENTION Hearing aids were an optional component of both intervention and control groups |

| Kießling 1980 | ALLOCATION Non‐randomised controlled trial PARTICIPANTS Adults with tinnitus and hearing loss INTERVENTION Hearing aids versus sound generators OUTCOME MEASURE No appropriate questionnaire measure of tinnitus severity or handicap, used tinnitus loudness, tinnitus pitch and self reported benefit |

| Mehlum 1984 | ALLOCATION Randomised controlled trial PARTICIPANTS Adults with tinnitus and hearing loss INTERVENTION Open ear mould hearing aid versus open ear mould combination device versus sound generator versus no intervention OUTCOME MEASURE No questionnaire measure of tinnitus severity or handicap; used patient preference as primary outcome |

| Melin 1987 | ALLOCATION Randomised controlled trial PARTICIPANTS Adults with tinnitus and hearing loss INTERVENTION Hearing aids versus no intervention (waiting list) OUTCOME MEASURE No appropriate questionnaire measure of tinnitus severity or handicap; used visual analogue scale (VAS) of tinnitus severity |

| Moffat 2009 | ALLOCATION Non‐randomised controlled trial PARTICIPANTS Adults with tinnitus and hearing loss INTERVENTION Hearing aids with low‐to‐medium amplification versus hearing aids with high bandwidth amplification versus no intervention OUTCOME MEASURE No appropriate questionnaire measure of tinnitus severity or handicap; used tinnitus loudness, tinnitus frequency |

| Oz 2013 | ALLOCATION Randomised controlled trial PARTICIPANTS Adults with tinnitus and hearing loss INTERVENTION Combination hearing aids or sound generators with betahistine versus betahistine alone, but data combined in the report |

| Schaette 2010 | ALLOCATION Non‐randomised, participants allocated according to degree of hearing level PARTICIPANTS Adults with tinnitus INTERVENTION Comparison was not an alternative intervention; comparison was made between groups of individuals with tinnitus pitch within or outside the range of amplification or output of sound devices |

Characteristics of ongoing studies [ordered by study ID]

NCT01857661.

| Trial name or title | 'The influence of the sound generator combined with conventional amplification for tinnitus control: blind randomized clinical trial' |

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial, single‐blind design |

| Participants | Adults with tinnitus and hearing loss |

| Interventions | Hearing aids versus combination hearing aids |

| Outcomes | Tinnitus Handicap Inventory and psychoacoustic measurements |

| Starting date | September 2012 |

| Contact information | Prof Dr Ricardo F. Bento, Otorhinolaryngology Department, Medicine School University of Sao Paulo, Brazil (rbento@gmail.com) |

| Notes | ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT01857661 Grant number: 11/03001‐2 |

Differences between protocol and review

In the protocol for this review we anticipated including both randomised and non‐randomised studies; in the review we further clarified our definition of 'non‐randomised studies' as set out in Types of studies.

Primary outcome measure: we have specified that tinnitus severity or handicap must be measured using one of the validated questionnaires listed in Table 2. We will update this list on an ongoing basis as other questionnaires are validated.

Secondary outcome measures: we have clarified adverse effects as being those associated with both hearing aid fitting 'and use'.

We have provided more detail of our methods for the following: selection of studies; choosing measures of effect for dichotomous (risk ratio) and continuous data (mean difference or standardised mean difference); handling potential unit of analysis issues (cluster‐randomised trials and multiple observations for the same outcome) and assessment of clinical heterogeneity.

Contributions of authors

Hoare DJ: lead author, planned and wrote the protocol, selected which studies to include, interpreted the analysis, drafted the final review.

Edmondson‐Jones AM: extracted data, assessed risk of bias, analysed data, interpreted the analysis, provided critical comment on the draft review.

Sereda M: extracted data, assessed risk of bias, provided critical comment on the draft review.

Akeroyd MA: selected which studies to include, provided critical comment on the draft review.

Hall DA: selected which studies to include, provided critical comment on the draft review and conducted the revisions.

Sources of support

Internal sources

-

National Institute for Health Research, UK.

DJH, MEJ, MS and DAH are funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Biomedical Research Unit Programme, however the views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health. MAA is funded by the UK Medical Research Council (MRC).

External sources

NIHR‐Cochrane Incentive Award 2013, UK.

Declarations of interest

DJH, MS and DH are researchers involved in an ongoing programme of research funded by National Institute for Health Research to assess the efficacy and effectiveness of current and novel sound‐based interventions for tinnitus. They are also conducting research on devices for treating tinnitus with The Tinnitus Clinic (DJH and DH) and Oticon A/S (MS and DH). DH has received fees for consultancy from Merz Pharmaceuticals GmbH. DJH is vice‐chair of the British Tinnitus Association's Professional Advisory Committee and a media spokesperson for the charity. DH is a member of the Board of Trustees of the British Tinnitus Association. ME‐J and MAA have no interests to declare.

New

References

References to studies included in this review

Parazzini 2011 {published data only}

- Parazzini M, Bo L, Jastreboff M, Tognola G, Ravazzani P. Open ear hearing aids in tinnitus therapy: an efficacy comparison with sound generators. International Journal of Audiology 2011;50(8):548‐53. [DOI: 10.3109/14992027.2011.572263] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to studies excluded from this review

dos Santos Ferrari 2007 {published data only}

- dos Santos Ferrari GM, Sanches TG, Bovino Pedalini ME. The efficacy of open molds in controlling tinnitus. Brazilian Journal of Otorhinolaryngology 2007;73:370‐7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Eysel‐Gosepath 2004 {published data only}

- Eysel‐Gosepath K, Gerhards F, Schicketanz KH, Teichmann K, Benthien M. Attention diversion in tinnitus therapy. Comparison of the effects of different treatment methods [Aufmerksamkeitslenkung in der Tinnitustherapie]. HNO 2004;52:431‐8. [DOI: 10.1007/s00106-003-0929-4] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Forti 2010 {published data only}

- Forti S, Crocetti A, Scotti A, Pignatoro L, Ambrosetti U, Bo L. Tinnitus sound therapy with open ear canal hearing aids. B‐ENT 2010;6:195‐9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hazell 1985 {published data only}

- Hazell JWP, Wood SM, Cooper HR, Stephens SDG, Corcoran AL, Coles RRA, et al. A clinical study of tinnitus maskers. British Journal of Audiology 1985;19:65‐146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jastreboff PJ, Hazell JWP, Graham RL. Neurophysiological model of tinnitus: dependence of the minimal masking level on treatment outcome. Hearing Research 1994;80:216‐32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephens SD, Corcoran AL. A controlled study of tinnitus masking. British Journal of Audiology 1985;19:159‐67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Henry 2006 {published data only}

- Henry JA, Schechter MA, Zaugg TL, Griest S, Jastreboff PJ, Vernon JA, et al. Outcomes of clinical trial: tinnitus masking versus tinnitus retraining therapy. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology 2006;17:104‐32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kießling 1980 {published data only}

- Kießling J. Masking of tinnitus aurium by maskers and hearing aids. HNO 1980;28:383‐8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Mehlum 1984 {published data only}

- Mehlum D, Grasel G, Fankhauser C. Prospective crossover evaluation of four methods of clinical management of tinnitus. Otolaryngology ‐ Head and Neck Surgery 1984;92:448‐53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Melin 1987 {published data only}

- Melin L, Scott B, Lindberg P, Lyttkens L. Hearing aids and tinnitus – an experimental group study. British Journal of Audiology 1987;21:91‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Moffat 2009 {published data only}

- Moffat G, Adjout K, Gallego S, Thai‐Van H, Collet L, Noreña AJ. Effects of hearing aid fitting on the perceptual characteristics of tinnitus. Hearing Research 2009;254:82‐91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Oz 2013 {published data only}

- Oz I, Arslan F, Hizal E, Erbek SH, Eryaman E, Senkal OA, et al. Effectiveness of the combined hearing and masking devices on the severity and perception of tinnitus: a randomized, controlled, double‐blind study. ORL; Journal of Oto‐Rhino‐Laryngology and Its Related Specialties 2013;75:211‐20. [DOI: 10.1159/000349979] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Schaette 2010 {published data only}

- Schaette R, König O, Hornig D, Gross M, Kempter R. Acoustic stimulation treatments against tinnitus could be most effective when tinnitus pitch is within the stimulated frequency range. Hearing Research 2010;269(1‐2):95‐101. [DOI: 10.1016/j.heares.2010.06.022] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to ongoing studies

NCT01857661 {published data only}

- Munhoes dos Santos G. The influence of the sound generator combined with conventional amplification for tinnitus control: blind randomized clinical trial. http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01857661. [NCT01857661] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Additional references

Adjamian 2009

- Adjamian P, Sereda M, Hall DA. The mechanisms of tinnitus: perspectives from human functional neuroimaging. Hearing Research 2009;253:15‐31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Andersson 2009

- Andersson G. Tinnitus patients with cognitive problems: causes and possible treatments. The Hearing Journal 2009;62:27‐8,30. [Google Scholar]

Beck 2011

- Beck DL. Hearing aid amplification and tinnitus: 2011 overview. The Hearing Journal 2011;64:12‐4. [Google Scholar]

Biesinger 2010

- Biesinger E, Bo L, Ridder D, Goodey R, Herraiz C, Kleinjung T, et al. Algorithm for the diagnostic & therapeutic management of tinnitus. http://www.tinnitusresearch.org/en/documents/downloads/TRI_Tinnitus_Flowchart.pdf (accessed 19 June 2012).

Buss 1998

- Buss E, Hall III JW, Grose JH, Hatch DR. Perceptual consequences of peripheral hearing loss: do edge effects exist for abrupt cochlear lesions? . Hearing Research 1998;125:98‐108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Cima 2012

- Cima RFF, Maes IH, Joore MA, Scheyen DJWM, Refaie A, Baguley DM, et al. Specialised treatment based on cognitive behaviour therapy versus usual care for tinnitus: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2012;379(9830):1951‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Crönlein 2007

- Crönlein T, Langguth B, Geisler P, Hajak G. Tinnitus and insomnia. Progress in Brain Research 2007;166:227‐33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Davis 2000

- Davis A, Rafaie A. Epidemiology of tinnitus. In: Tyler RS editor(s). Tinnitus Handbook. Singular, Thomson Learning, 2000. [Google Scholar]

Del Bo 2007

- Bo L, Ambrosetti U. Hearing aids for the treatment of tinnitus. Progress in Brain Research 2007;166:341‐5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Department of Health 2009

- Department of Health. Provision of Services for Adults with Tinnitus. A Good Practice Guide. London: Central Office of Information, 2009. [Google Scholar]

Dietrich 2001

- Dietrich V, Nieschalk M, Stoll W, Rajan R, Pantev C. Cortical reorganization in patients with high frequency cochlear hearing loss. Hearing Research 2001;158:95‐101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Dillon 2012

- Dillon H. Hearing Aids. 2nd Edition. Turramurra: Boomerang Press, 2012:48‐54. [Google Scholar]

Dobie 1999

- Dobie RA. A review of randomized clinical trials in tinnitus. Laryngoscope 1999;109:1202‐11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Dong 2010

- Dong S, Rodger J, Mulders WH, Robertson D. Tonotopic changes in GABA receptor expression in guinea pig inferior colliculus after partial unilateral hearing loss. Brain Research 2010;1342:24‐32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Egger 1997

- Egger M. Bias in meta‐analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 1997;315:629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Eggermont 2004

- Eggermont JJ, Roberts LE. The neuroscience of tinnitus. Trends in Neuroscience 2004;27:676‐82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Eggermont 2010

- Eggermont J, Roberts L, Caspary D, Shore S, Melcher J, Kaltenbach J. Ringing ears: the neuroscience of tinnitus. Journal of Neuroscience 2010;30:14972‐9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

El‐Shunnar 2011

- El‐Shunnar S, Hoare DJ, Smith S, Gander PE, Kang S, Fackrell K, et al. Primary care for tinnitus: practice and opinion among GPs in England. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice 2011;17:684‐92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Engineer 2011

- Engineer ND, Riley JR, Seale JD, Vrana WA, Shetake JA, Sudanagunta SP, et al. Reversing pathological neural activity using targeted plasticity. Nature 2011;470:101‐4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Fowler 1944

- Fowler EP. Head noises in normal and disordered ears: significance, measurement, differentiation and treatment. Archives of Otolaryngology 1944;39:490‐503. [Google Scholar]

Goebel 1994

- Goebel G, Hiller W. The tinnitus questionnaire. A standard instrument for measuring the severity of tinnitus. Results of a multicentre study with the tinnitus questionnaire. HNO 1994;42:166‐72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Guitton 2003

- Guitton MJ, Caston J, Ruel J, Johnson RM, Pujol R, Puel J‐L. Salicylate induces tinnitus through activation of cochlear NMDA receptors. Journal of Neuroscience 2003;23:3944‐52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hahn 2008

- Hahn A, Radkova R, Achiemere G, Klement V, Alpini D, Strouhal J. Multimodal therapy for chronic tinnitus. International Tinnitus Journal 2008;14:69‐71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hall 2011

- Hall D, Láinez M, Newman C, Sanchez T, Egler M, Tennigkeit F, et al. Treatment options for subjective tinnitus: self reports from a sample of general practitioners and ENT physicians within Europe and the USA. BMC Health Services Research 2011;11(1):302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hallam 1996

- Hallam RS. Manual of the Tinnitus Questionnaire. London: The Psychological Corporation, Brace & Co, 1996. [Google Scholar]

Han 2009

- Han BI, Lee HW, Kim TY, Lim JS, Shin KS. Tinnitus: characteristics, causes, mechanisms, and treatments. Journal of Clinical Neurology 2009;5:11‐9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Handbook 2011

- Higgins JPT, Green S (editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. Available from www.cochrane‐handbook.org.

Henry 2004

- Henry JA, Snow JB (editors). Tinnitus: Theory and Management. Ontario: BC Becker Inc, 2004. [Google Scholar]

Henry 2005

- Henry JA, Dennis KC, Schechter MA. General review of tinnitus: prevalence, mechanisms, effects, and management. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research 2005;48:1204‐35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Henry 2008

- Henry JA, Zaugg TL, Myers PJ, Schechter MA. The role of audiological evaluation in progressive audioloogic tinnitus management. Trends in Amplification 2008;12(3):170‐87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hiller 2005

- Hiller W, Haerkotter C. Does sound stimulation have additive effects on cognitive‐behavioral treatment of chronic tinnitus?. Behaviour Research and Therapy 2005;43:595‐612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hiller 2006

- Hiller W, Goebel G. Factors influencing tinnitus loudness and annoyance. Archives of Otolaryngology ‐‐ Head and Neck Surgery 2006;132:1323‐30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hoare 2011

- Hoare DJ, Kowalkowski V, Kang S, Hall DA. Systematic review and meta‐analyses of RCTs examining tinnitus management. Laryngoscope 2011;121:1555‐64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hoare 2011a