Abstract

The Polypyrrole is properly synthesized with the customary ammonium persulphate as an oxidizing agent. The number of reactions for versatile molar ratios (oxidant: monomer) is addressed and pronounced. Powder X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis revealed the material amorphous nature by wide peak from 20° to 30°. As the molar ratio is changed, the Fourier Transform Infra Red (FTIR) spectrum shows the substantiation of functional groups and peaks are shifted for each specimen slightly. UV–visible spectral study shows a major peak at 320 nm, for typical π-π* transitions. Scanning Electron Microscopic (SEM) study confirmed the agglomerated polypyrrole sample for the surface morphological periphery. It is enabled for electronic filter influx property with versatile macro scale in microns as 3.7874, Polypyrrole is tried for electronic filters as the influx in microns of different scales. Hardness profile for RISE effectiveness and in the biomedical sector as a better anti-diabetic agent by IC-50 values. The hardness value for Vicker's scale of 100 g is 97.9 kg/mm2.

Keywords: Oxidative polymerization, FTIR, SEM, Influx, Anti-diabetic

1. Introduction

Intrinsic conducting polymers have been of better scope for researchers in recent years for the reason owing to their determinant properties. Among all types of conducting polymers, Polypyrrole (PPy), in particular, has remarkable environmental flexibility and surpassing conductivity in the doping process [1]. Composite polymers behave as insulators in their intrinsic state but act as semiconductors after redox reactions. The oxidized state exhibits distinct optical, electrical, and thermo-electric properties, which serve as the foundation for various applications in the industrial way and medicinal sectors [[2], [3], [4]]. These properties can be made to order by controlling the reaction condition properly and with the oxidant/monomer ratio too. Because of the exceptional capabilities of conducting polymers, particularly PPy, they have been employed for oxidation coating of organic and inorganic materials as well as in electrochemical sensors [5,6]. Because of its good conductivity following oxidative polymerization, PPy has been utilized as a biosensor in the biomedical field and present study focusing on the work against diabetic ailment [[7], [8], [9]].

Numerous composites including PPy are in many assorted applications related to energy storage and production, including batteries, solar cells, super-capacitors, home appliances, automobiles, fuel cells, biomedical equipment, and surgical appliances, material and nanomaterial-based polymers and their composites are being studied as specified as the literature based citation [3,5]. The successful advancements made in the use of biocompatible and biologically relevant co-polymers and dendrimers for the treatment of cancer, including their use as a medium for effective anticancer medications [8,9]. Furthermore, they are significant due to their roles as gas sensors [[10], [11], [12]] and pH sensors [13]. Conducting polymers has been demonstrated as a supercapacitor in energy storage applications [14,15]. Conducting PPy has been employed for metal anti-corrosion treatment, medication deliverance systems, anticancer drugs and toxic gas sensors [[16], [17], [18], [19], [20], [21]]. In the present study, pyrrole is oxidized using APS for assorted oxidant-to-monomer ratios (MR 0.5 to 3). The confirmation of the synthesized material is done using characterization techniques such as FTIR, XRD, UV–Vis and SEM.

The Ag-loaded PPy micro-capsules have shown promising medical applications such as computed tomography and gamma imaging [22]. Se@PPy nanocomposites have the potential to be an effective theranostic agent (bio-marker-based shared work) for tumor PAI and PTT mediated by near-infrared light [23]. The incorporation of PPy within the PCL/chitosan matrix was discovered to have a positive influence on the overall properties of the nanofibrous structure, making them suitable for biomedical applications [24]. In the NIR window, PPy nanosheets have shown good biocompatibility as well as significant tumor ablation power [25].

In this communication, the interpretation is the influence of oxidant on the morphological properties of PPy as well mechano-electronic, against diabetes and further can be proceeded for cancer treatment, especially the MCF-7 cells for breast cancer and is in the pipeline. Conducting polymers have received a great deal of attention due to their superior properties, which include, optical and high mechanical properties, tunable electrical properties, ease of synthesis and fabrication, high environmental stability over conventional inorganic materials. Because of its ease of preparation and surface modification, PPy has been used in biomedical applications as conducting polymers. However, to effectively use PPy as a bio-material implant, it is necessary to understand and control the polymer's electrical properties, physical topography, and surface chemistry. The conductive property of polypyrrole makes it useful in the medicinal field.

2. Experimental

2.1. Materials

The monomer pyrrole was purchased from Spectrochem Pvt. Ltd. In Mumbai. Before the initiation of the reaction, the double-distilled pyrrole was kept at 4 °C. AR grade Ammonium persulphate (APS) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Chemicals Pvt. Ltd. (Mumbai), and it was used as an oxidizing agent. All of the solutions and reactions were carried out in the deionized water.

2.2. Preparation of PPy powder

PPy was synthesized using an oxidative polymerization technique. Before the commencement of the polymerization procedure, 1 M pyrrole was produced and stirred constantly in an ice bath for around 30 min. A solution of 1 M ammonium persulfate was prepared and precooled. In the pyrrole solution, precooled ammonium persulfate solution was added dropwise. The reaction was carried out for around 6 h at 0 °C with constant stirring. When the oxidizing agent was added, the color of the mixture changed from dark green to black, indicating that the polymerization process had been initiated instantly.

After the reaction time, the mixture was allowed to be accomplished for nearly 48 h to ensure complete polymerization. After complete polymerization, the mixture was washed with deionized water to eliminate unreacted components before filtering with a vacuum filter. A constant weight was achieved by vacuum-drying the samples at room temperature. Powders ranging from 0.5 to 3 M ratios were synthesized using the steps described above.

2.3. Characterization techniques

FTIR spectroscopy (Shimadzu, IRAffinity-1S) was used to analyze the chemical structure of PPy in the frequency range 400–4000 cm−1. The surface morphology of the samples was investigated using SEM (FEI, Quanta 200). The structural analysis of the black powder (PPy) was carried out using powder X-Ray Diffraction (XRD) technique in the range of 2θ from 20o to 80o.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Fourier Transform-infrared analysis (FTIR)

Fig. 1 depicts the spectra of PPy powder at various molar ratios (oxidant/monomer) ranging from 0.5 to 3. The profile of several polymer samples is reported using FTIR, which detects different functional groups and characterizes covalent bonding information. The peak positions correlate to various covalent bonds, as previously demonstrated by Ramaprasad [26], Taunk [27], Chitte [28], Navale [29], and Chougule [30]. Table 1 reveals the peaks reported in prior work are tabulated in column no. 2 and columns 3–8 list the molar ratio-based peaks found in the test samples. The fluctuation in assignment position is discovered as a result of a change in a molar ratio (oxidant/monomer). As pyrrole rings are attached to the polymer's backbone, the polymer's structure can be altered by attaching varying numbers of atoms.

Fig. 1.

FT-IR spectra of PPy powders with various oxidant to monomer ratios.

Table 1.

FT-IR absorption peaks of PPy.

| Assignments | Peak positions in Refs. [22,26] cm−1 | Peak positions for different samples (cm−1) Molar Ratio (MR): (APS/Pyrrole) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MR:0.5 | MR:1 | MR:1.5 | MR:2 | MR:2.5 | MR:3 | |||

| N–H deformation | 3443 | [5] | 3458 | 3458 | 3456 | 3452 | 3452 | 3454 |

| Absorbance of CH2 group | 2870 | [5] | 2877 | 2862 | 2867 | 2860 | 2868 | 2869 |

| C N bonds | 1685 | [6] | 1643 | 1668 | 1670 | 1674 | 1676 | 1678 |

| C–H out plane stretching | 1473 | [7] | 1446 | 1446 | 1448 | 1449 | 1452 | 1453 |

| C–H in-plane deformation | 1250 | [8] | 1247 | 1281 | 1257 | 1259 | 1236 | 1247 |

| N–C stretching | 1046 | [9] | 1074 | 1074 | 1076 | 1076 | 1078 | 1076 |

| N–C stretching | 920 | [9] | 938 | 983 | 987 | 991 | 993 | 991 |

| N–C stretching | 811 | [9] | 825 | 823 | 831 | 842 | 873 | 887 |

| = C–H Stretching | 793 | [7] | 792 | 792 | 788 | 797 | 792 | 790 |

| C–C out of plane deformation/C–H rocking/C–H wagging | 681 | [6] | 674 | 676 | 657 | 674 | 672 | 671 |

3.2. X-ray diffraction analysis, UV–Vis spectral analysis and morphological study using SEM

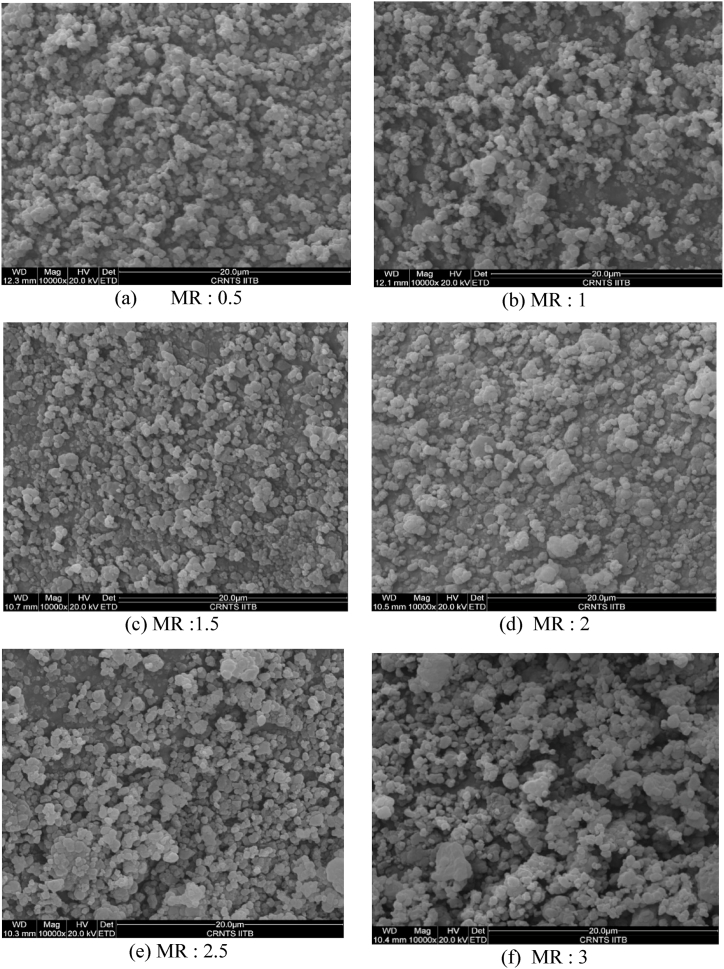

The confirmation of the sample especially of PPy is by the structure by powder XRD; the absorbance cut-off by UV–visible study and the internal morphology by SEM analysis as follows. The PPy structural representation is by the powder XRD pattern and the X-ray diffraction patterns of synthesized PPy with varied oxidant-to-monomer ratio are shown in Fig. 2. The wide peaks are detected in the zone 20° < 2θ < 30°, for molar ratios varying from 0.5 to 3.0, revealing the amorphous nature of synthesized PPy [31,32], as well as the short-range arrangement chains of PPy [33]. Using Scherer's formula, the crystallite size from a sharp peak at 25° for PPy is estimated, resulting in a high-intensity sharp peak of approximately 77.412 nm for PPy powder. The electronic transition of the synthesized PPy is analyzed with the absorption peaks for various oxidant concentrations are shown in Fig. 3. The absorption peak is found at about 320 nm corresponding to the π-π* transition, and 375 nm–425 nm reveals the creation of bipolarons [34]. Polymerization is quickening by the creation of polarons and bipolarons, which promotes the conjugate in a highly conducting state [34,35]. The morphological structure of the synthesized PPy powder is shown in Fig. 4(a–f). The morphological structure of globular particles demonstrates their amorphous nature [36,37]. All views have been selected with a higher magnification of 10 k for better comparison. As seen in Fig. (4), the particle size and, therefore, agglomeration increases as the molar ratio increases from 0.5 to 3. In addition, the bonding effect between grains improves as the proportion of dopant (APS) increases [38].

Fig. 2.

XRD pattern for PPy powders with different molar ratios.

Fig. 3.

UV–Vis absorbance spectrum of PPy powder with different molar ratios.

Fig. 4.

(a–f)SEM of PPy powder for different molar ratios (oxidant/monomer).

3.3. Electronic, mechanical-hardness and anti-diabetic analysis of PPy

The effective role of PPy is tried for electronic filters as the influx in microns for the opto-electronic filters and is 3.7873; 3.7874; 3.7874; 3.7874; 3.7874 and 3.7875 corresponding to MR values as 0.5; 1.0; 1.5; 2.0; 2.5 and 3 respectively, showed no much variations as samples are not anisotropic and are amorphous in nature; so, as the MR values [[39], [40], [41], [42], [43]] are getting elevated in esteem and for filters used in optoelectronic type, minor variations are seen and are also in fourth decimal places. Furthermore, in the burglar alarm to enhance the efficiency of the system, PPy coated components are 1.12, 1.13, 1.13, 1.13, 1.13 and 1.16 times efficient than the uncoated ones and are reducing the noise level due to fine homogeneous particles [[43], [44], [45], [46], [47], [48]]. The IC-741 type of voltage doubling circuital portfolio represents double the value for normal case and is 2.01; 2.03; 2.03; 2.03; 2.03; 2.03 times for the versatile scaling MR values and confirmed the doubling of voltage in circuits. The mechanical representation of samples figuring out the proper projection of their hardness or softness and identifying it based on their value to tribological parameters and here, the hardness profile of MR as 0.5 is tried for Vicker's scale of 25, 50 and 100 g and their HV value in kg/mm2 as 56.2; 68.6 and 97.9 and give rise to n as above 2 and is of Reverse Indentation Size Effect and other samples are in progress for analysis and are pelleted and analyzed [[43], [44], [45], [46], [47], [48]]. The versatile method of the carbothermal way [[49], [50], [51], [52], [53]] is deliberately represented to proceed for PPy in the future with other typical studies [49,[54], [55], [56], [57], [58], [59]]. The biological impacts for insulin deficiency altered by alpha-amylase inhibited concentration of PPy with various MR of versatile scales or % with IC-50 as 48.75; 48.75; 48.75; 48.75; 48.76 and 48.76 correspond to 0.5; 1.0; 1.5; 2.0; 2.5 and 3.0 MR leads to a better scope of activity against the ailment of diabetics and no change in data of IC-50 is observed and the uniformity is due to the amorphous type of nature of versatile MR esteem of 6 samples of PPys [[43], [44], [45], [46], [47], [48]]. While performing for MR-0.5 Alpha Glucosidase based provision of IC-50 as 61.09 and is the slightly higher value than the former one. The influx, anti-diabetic and hardness data are confined with Fig. 5 a-c correspondingly.

Fig. 5.

(a) Influx property (b) antidiabetic analysis (c) Mechanical Hardness of PPy sample.

4. Conclusion

PPy is successfully synthesized using a chemical oxidative polymerization processing with changing oxidant/dopant concentrations. The morphological behavior of agglomerated particles changed as the molar ratio varied between 0.5 and 3, as confirmed by SEM, FTIR, and X-ray diffraction studies. The controllable tailor-made properties of the synthesized PPy powder make the material a promising candidate to be used in applications such as toxic gas sensing, pH measurement, color sensors, dye degradation and many other applications. The PPy samples are mainly used in electronics as filter use with influxing data especially for opto-electronic filters and identified the nature of hardness profile with Vicker's mode as well as the bio-medicinal impact as a standard inhibitor for diabetics with alpha-amylase methodology and a better agent for bio use as confined with IC-50 values. In the future, the irradiation of PPy can proceed and micro/nano by milled impact can be addressed for anti-cancer and antimicrobial as well as tribological usage.

Funding

This publication is developed with the support of Project BG05M2OP001-1.001-0004 UNITe, funded by the Operational Programme “Science and Education for Smart Growth”, co-funded by the European Union through the European Structural and Investment Funds.

Author contribution statement

Sahebrao B. Pagar: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Wrote the paper. Tatyarao N. Ghorude, Maria P. Nikolova: Analyzed and interpreted the data. SenthilKannan.K: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Data availability statement

No data was used for the research described in the article.

Declaration of competing interest

For publication and all author declare that it is a new work and no conflict among them.

Acknowledgements

Authors used the Research Laboratory of ‘G. E. Society's, HPT Arts and RYK Science College, Nashik’ for all experimental work with their permission. Electronic work is enabled in SIMATS and bio-work is enabled by outsourcing.

References

- 1.Das T.K., Prusty S. Review on conducting polymers and their applications. Polym.-Plast. Technol. Eng. Oct. 2012;51(14):1487–1500. doi: 10.1080/03602559.2012.710697. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bajpai M., Srivastava R., Dhar R., Tiwari R.S. Review on optical and electrical properties of conducting polymers. Indian J. Mater. Sci. 2016:1–8. doi: 10.1155/2016/5842763. https://www.hindawi.com/journals/ijms/2016/5842763 Jun. 2016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Malook K., Khan H., Shah M., Ihsan-Ul-Haque Synthesis, characterization and electrical properties of polypyrrole/V2O5 composites. Kor. J. Chem. Eng. Jan. 2018;35(1):12–19. doi: 10.1007/s11814-017-0263-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang S., et al. Thermoelectric properties of solution-processed n-doped ladder-type conducting polymers. Adv. Mater. 2016;28(48):10764–10771. doi: 10.1002/adma.201603731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Omastová M., Mičušík M. Polypyrrole coating of inorganic and organic materials by chemical oxidative polymerisation. Chem. Pap. May 2012;66(5):392–414. doi: 10.2478/s11696-011-0120-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Le T.-H., Kim Y., Yoon H. Electrical and electrochemical properties of conducting polymers. Polymers. Apr. 2017;9(4) doi: 10.3390/polym9040150. Art. no. 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ghorbani Zamani F., Moulahoum H., Ak M., Odaci Demirkol D., Timur S. Current trends in the development of conducting polymers-based biosensors. TrAC, Trends Anal. Chem. Sep. 2019;118:264–276. doi: 10.1016/j.trac.2019.05.031. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang G., Morrin A., Li M., Liu N., Luo X. Nanomaterial-doped conducting polymers for electrochemical sensors and biosensors. J. Mater. Chem. B. Jun. 2018;6(25):4173–4190. doi: 10.1039/C8TB00817E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kumar A.M., Suresh B., Ramakrishna S., Kim K.-S. Biocompatible responsive polypyrrole/GO nanocomposite coatings for biomedical applications. RSC Adv. Nov. 2015;5(121):99866–99874. doi: 10.1039/C5RA14464G. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alizadeh N., Pirsa S., Mani-Varnosfaderani A., Alizadeh M.S. Design and fabrication of open-tubular array gas sensors based on conducting polypyrrole modified with crown ethers for simultaneous determination of alkylamines. IEEE Sensor. J. Jul. 2015;15(7):4130–4136. doi: 10.1109/JSEN.2015.2411515. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Park S.J., Park C.S., Yoon H. Chemo-electrical gas sensors based on conducting polymer hybrids. Polymers. May 2017;9(5) doi: 10.3390/polym9050155. Art. no. 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garg R., Kumar V., Kumar D., Chakarvarti P. Polypyrrole microwires as toxic gas sensors for ammonia and hydrogen sulphide. J. Sens. Instrum. Jan. 2015;3:1–13. 10.7726/jsi.2015.1001.10.7726/jsi.2015.1001. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Czaja T., Wójcik K., Grzeszczuk M., Szostak R. Polypyrrole–methyl orange Raman pH sensor. Polymers. Apr. 2019;11(4) doi: 10.3390/polym11040715. Art. no. 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Afzal A., Abuilaiwi F.A., Habib A., Awais M., Waje S.B., Atieh M.A. Polypyrrole/carbon nanotube supercapacitors: technological advances and challenges. J. Power Sources. Jun. 2017;352:174–186. doi: 10.1016/j.jpowsour.2017.03.128. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang H.-N., et al. Polyoxometalate-based metal–organic frameworks with conductive polypyrrole for supercapacitors. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. Sep. 2018;10(38):32265–32270. doi: 10.1021/acsami.8b12194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen Z., et al. Superior conducting polypyrrole anti-corrosion coating containing functionalized carbon powders for 304 stainless steel bipolar plates in proton exchange membrane fuel cells. Chem. Eng. J. Aug. 2020;393 doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2020.124675. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.El Jaouhari A., et al. Electrosynthesis of zinc phosphate-polypyrrole coatings for improved corrosion resistance of steel. Surface. Interfac. Jun. 2019;15:224–231. doi: 10.1016/j.surfin.2019.02.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shah S.A.A., et al. Electrochemically enhanced drug delivery using polypyrrole films. Materials. Jul. 2018;11(7) doi: 10.3390/ma11071123. Art. no. 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Uppalapati D., Boyd B.J., Garg S., Travas-Sejdic J., Svirskis D. Conducting polymers with defined micro- or nanostructures for drug delivery. Biomaterials. Dec. 2016;111:149–162. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2016.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Samanta D., Hosseini-Nassab N., McCarty A.D., Zare R.N. Ultra-low voltage triggered release of an anti-cancer drug from polypyrrole nanoparticles. Nanoscale. May 2018;10(20):9773–9779. doi: 10.1039/C8NR01259H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Naveen M.H., Gurudatt N.G., Shim Y.-B. Applications of conducting polymer composites to electrochemical sensors: a review. Appl. Mater. Today. Dec. 2017;9:419–433. doi: 10.1016/j.apmt.2017.09.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Krug P., Kwiatkowska M., Mojzych I., Głowala P., Dorant S., Kępińska D., Chotkowski M., Janiszewska K., Stolarski J., Wiktorska K., Kaczyńska K., Mazur M. Polypyrrole microcapsules loaded with gold nanoparticles: perspectives for biomedical imaging. Synth. Met. 2019;248:27–34. doi: 10.1016/j.synthmet.2018.12.025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang J., Qiu T., Lan Y., Tu C., Shang T., Lin Y., Mao G., Yang B. Autocatalytic polymerization of selenium/polypyrrole nanocomposites as functional theranostic agents for multi-spectral photoacoustic imaging and photothermal therapy of tumor. Mater. Today Chem. 2020;17 doi: 10.1016/j.mtchem.2020.100344. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Talebi A., Labbaf S., Karimzadeh F. Polycaprolactone‐chitosan‐polypyrrole conductive biocomposite nanofibrous scaffold for biomedical applications, Polym. Composer. 2020;41:645–652. doi: 10.1002/pc.25395. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang X., Ma Y., Sheng X., Wang Y., Xu H. Ultrathin polypyrrole nanosheets via space-confined synthesis for efficient photothermal therapy in the second near-infrared window. Nano Lett. 2018;18:2217–2225. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.7b04675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ramaprasad A.T., Latha D., Rao V. Synthesis and characterization of polypyrrole grafted chitin. J. Phys. Chem. Solid. May 2017;104:169–174. doi: 10.1016/j.jpcs.2017.01.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Taunk M., Kapil A., Chand S. Chemical synthesis and low temperature electrical transport in polypyrrole doped with sodium bis(2-ethylhexyl) sulfosuccinate. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. Feb. 2011;22(2):136–142. doi: 10.1007/s10854-010-0102-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chitte H.K., Bhat N.V., Gore M.A.V., Shind G.N. Synthesis of polypyrrole using ammonium peroxy disulfate (APS) as oxidant together with some dopants for use in gas sensors. Mater. Sci. Appl. Oct. 2011;2(10) doi: 10.4236/msa.2011.210201. Art. no. 10. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Navale S.T., Mane A.T., Chougule M.A., Sakhare R.D., Nalage S.R., Patil V.B. Highly selective and sensitive room temperature NO2 gas sensor based on polypyrrole thin films. Synth. Met. Mar. 2014;189:94–99. doi: 10.1016/j.synthmet.2014.01.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chougule M.A., Pawar S.G., Godse P.R., Mulik R.N., Sen S., Patil V.B. Synthesis and characterization of polypyrrole (PPy) thin films. Soft Nanosci. Lett. 2011;1(1):6–10. doi: 10.4236/snl.2011.11002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Khadem F., Pishvaei M., Salami-Kalajahi M., Najafi F. Morphology control of conducting polypyrrole nanostructures via operational conditions in the emulsion polymerization. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2017;134(15) doi: 10.1002/app.44697. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Padmapriya S., Harinipriya S. Hydrogen storage capacity of polypyrrole in alkaline medium: effect of oxidants and counter anions. J. Mater. Res. Technol. Sep. 2019;8(5):4435–4447. doi: 10.1016/j.jmrt.2019.07.055. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sakthivel S., Boopathi A. Synthesis and Characterization of Polypyrrole (PPY) Thin Film by Spin Coating Technique. 2014;4(3):7. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Choudhary M., Islam R.U., Witcomb M.J., Mallick K. In situ generation of a high-performance Pd-polypyrrole composite with multi-functional catalytic properties. Dalton Trans. 2014;43(17):6396–6405. doi: 10.1039/C3DT53567C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shiigi H., Kishimoto M., Yakabe H., Deore B., Nagaoka T. Highly selective molecularly imprinted overoxidized polypyrrole colloids: one-step preparation technique. Anal. Sci. 2002;18(1):41–44. doi: 10.2116/analsci.18.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.S. Noshee et al., “Synthesis and characterization of polypyrrole synthesized via different routes,” Int. J. Eng. Res., vol. 9, no.06, p. 4..

- 37.Basavaraja C., Kim W.J., Thinh P.X., Huh D.S. Electrical conductivity studies on water-soluble polypyrrole-graphene oxide composites. Polym. Compos. Dec. 2011;32(12):2076–2083. doi: 10.1002/pc.21237. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Joshi A., Gangal S.A., Gupta S.K. Ammonia sensing properties of polypyrrole thin films at room temperature. Sensor. Actuator. B Chem. Aug. 2011;156(2):938–942. doi: 10.1016/j.snb.2011.03.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yussuf A., Al-Saleh M., Al-Enezi S., Abraham G. Synthesis and characterization of conductive polypyrrole: the influence of the oxidants and monomer on the electrical, thermal, and morphological properties. Int. J. Polym. Sci. Jul. 2018;2018 doi: 10.1155/2018/4191747. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lee J.Y., Song K.T., Kim S.Y., Kim Y.C., Kim D.Y., Kim C.Y. Synthesis and characterization of soluble polypyrrole. Synth. Met. Jan. 1997;84(1–3):137–140. doi: 10.1016/S0379-6779(97)80683-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Muller D., Rambo C.R., Luismar, Porto M., Schreiner W.H., Barra G.M.O. Structure and properties of polypyrrole/bacterial cellulose nanocomposites. Carbohydr. Polym. Apr. 2013;94(1):655–662. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2013.01.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Naveen Kumar T.R., Karthik P., Neppolian B. Polaron and bipolaron induced charge carrier transportation for enhanced photocatalytic H 2 production. Nanoscale. 2020;12(26):14213–14221. doi: 10.1039/D0NR02950E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.SenthilKannan K. Growth and characterisation-XRD, NLO of bis 2 amino pyridinium maleate (B2APM) crystals. Int. J. Energy Sect. Manag. 2018;7:1–3. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kolanjinathan M., Senthilkannan K., Paramasivam S., Baskaran P., Iyanar M. Anti-diabetic studies of 4-(4-chlorophenyl)-7,7-dimethyl-7,8-dihydro-4H-1-benzopyran-2,5(3H,6H)-dione – (CPDMDHHBPHHD) nano crystals. Mater. Today: Proc. 2020;33(7):2750–2752. doi: 10.1016/j.matpr.2020.01.575. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Patel R.P., SenthilKannan K., Hariharasuthan R., et al. Growth and XRD, elemental, mechanical, dielectric, optical and photoconductivity, and surface morphological characterizations of 2-[4-(trifluoromethyl) phenyl]-1H-benzimidazole (TFMPHB) crystals for electronic, mechanical applications. Braz. J. Phys. 2021;51:339–350. doi: 10.1007/s13538-021-00883-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.SenthilKannan K., Gunasekaran S. Synthesis, Growth and interpretation of (organic NLO) 4 bromo-4l chloro benzylidene aniline (BCBA) crystals. International Journal of Frontiers in Science and Technology. 2013;3(3):29–36. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Senthilkannan K., Balakumar D., Jothibas M. Fluorescence, filter, nano tribological studies of 12-(4-Chlorophenyl)-9,9-Dimethyl-9,10-Dihydro-8H-Benzo [A] Xanthen-11(12H)-One- (CPDDHBXH) macro and nano crystals. Mater. Today: Proc. 2020;33(1):4163–4166. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kolanjinathan M., et al. Dielectric, fluorescence, filter, nano tribological and photoconductivity studies of 4-(4-chlorophenyl)-7,7-dimethyl-7,8-dihydro-4H-1-benzopyran-2,5(3H,6H)-dione (CPDMDHHBPHHD) macro and nano crystals. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2020;31:16907–16917. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Li Kangqiang, Chen Jin, Peng Jinhui, Ruan Roger, Srinivasakannan C., Chen Guo. Pilot-scale study on enhanced carbothermal reduction of low-grade pyrolusite using microwave heating. Powder Technol. 2020;360:846–854. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Krug P., Kwiatkowska M., Mojzych I., Głowala P., Dorant S., Kępińska D., Chotkowski M., Janiszewska K., Stolarski J., Wiktorska K., Kaczyńska K., Mazur M. Polypyrrole microcapsules loaded with gold nanoparticles: perspectives for biomedical imaging. Synth. Met. 2019;248:27–34. doi: 10.1016/j.synthmet.2018.12.025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhang J., Qiu T., Lan Y., Tu C., Shang T., Lin Y., Mao G., Yang B. Autocatalytic polymerization of selenium/polypyrrole nanocomposites as functional theranostic agents for multi-spectral photoacoustic imaging and photothermal therapy of tumor. Mater. Today Chem. 2020;17 doi: 10.1016/j.mtchem.2020.100344. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Talebi A., Labbaf S., Karimzadeh F. Polycaprolactone‐chitosan‐polypyrrole conductive biocomposite nanofibrous scaffold for biomedical applications, Polym. Composer. 2020;41:645–652. doi: 10.1002/pc.25395. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang X., Ma Y., Sheng X., Wang Y., Xu H. Ultrathin polypyrrole nanosheets via space-confined synthesis for efficient photothermal therapy in the second near-infrared window. Nano Lett. 2018;18:2217–2225. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.7b04675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ramaprasad A.T., Latha D., Rao V. Synthesis and characterization of polypyrrole grafted chitin. J. Phys. Chem. Solid. 2017;104:169–174. doi: 10.1016/j.jpcs.2017.01.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chitte H.K., Bhat N.V., Gore M.A.V., Shind G.N. Synthesis of polypyrrole using ammonium peroxy disulfate (APS) as oxidant together with some dopants for use in gas sensors. Mater. Sci. Appl. 2011;2:1491. doi: 10.4236/msa.2011.210201. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Navale S.T., Mane A.T., Chougule M.A., Sakhare R.D., Nalage S.R., Patil V.B. Highly selective and sensitive room temperature NO2 gas sensor based on polypyrrole thin films. Synth. Met. 2014;189:94–99. doi: 10.1016/j.synthmet.2014.01.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Taunk M., Kapil A., Chand S. Chemical synthesis and low temperature electrical transport in polypyrrole doped with sodium bis(2-ethylhexyl) sulfosuccinate. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2011;22:136–142. doi: 10.1007/s10854-010-0102-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chougule M.A., Pawar S.G., Godse P.R., Mulik R.N., Sen S., Patil V.B. Synthesis and characterization of polypyrrole (PPy) thin films. Soft Nanosci. Lett. 2011;1:6–10. doi: 10.4236/snl.2011.11002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sikder A., Pearce A.K., Parkinson S.J., Napier R., O'Reilly R.K. Recent trends in advanced polymer materials in agriculture related applications. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2021;3:1203–1217. doi: 10.1021/acsapm.0c00982. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No data was used for the research described in the article.