Abstract

In the field of early childhood education, research has increasingly paid attention to male kindergarten teachers as research subjects. The shortage of male professionals in this field, coupled with the persistent issue of high turnover rates, presents significant challenges to the preschool education sector. Elevating the retention rate of male kindergarten teachers stands as a vital concern, with occupational commitment emerging as a pivotal factor influencing retention. This study endeavors to construct a moderated mediation model to unveil the potential pathways through which perceived organizational support, occupational well-being, and person–job fit impact occupational commitment. This study administered a questionnaire that included person–job fit, perceived organizational support, occupational well-being, and occupational commitment scales. The study collected 402 valid responses from male kindergarten teachers. The findings reveal several key insights: perceived organizational support has a positive direct influence on occupational commitment; occupational well-being acts as a mediator in the relationship between perceived organizational support and occupational commitment; and person–job fit plays a moderating role, negatively impacting the predictive effect of occupational well-being on occupational commitment. Consequently, perceived organizational support can exert both a direct influence on occupational commitment and an indirect impact, mediated by occupational well-being, with person–job fit moderating the latter pathway. These results contribute to the quantitative literature surrounding male kindergarten teachers, offering valuable insights. Moreover, they furnish policymakers in preschool education and kindergarten management with effective strategies to bolster the occupational commitment of male kindergarten teachers, ultimately addressing the pressing issue of teacher turnover in this field.

Keywords: Male kindergarten teacher, Occupational well-being, Occupational commitment, Perceived organizational support, Person–job fit

1. Introduction

According to the gender schema theory, the ages between three and six years is a critical period for gender role cognition in children. In this period, the existence of male kindergarten teachers can make children experience the caring ways of educators of different sex, which is conducive to the development of children's gender knowledge and gender constancy [1]. Simultaneously, male kindergarten teachers can help children who do not have easy access to male role models or who lack paternal love, producing a gender compensatory effect that promotes the integrity and growth of the child's personality [2]. However, the current industrialized society has formed a strict gender segregation pattern, in which the work of kindergarten teachers is considered an extension of housework in the public sphere, connected with mothers' care, and focusing on coaxing and babysitting children [3]. According to Bourdieu's field theory, people have long been immersed in a social field of negative gender stereotypes, and gender is a source of constraints and norms of occupation, forming the habitus of occupation selection [4]. Hence, under the restriction of strong negative gender stereotypes, the work of kindergarten teachers has been labeled as a female-centered profession.

Therefore, in addition to the education and teaching problems that kindergarten teachers face in their daily work, male kindergarten teachers, in particular, face fear when touching the bodies of their pupils and have to deal with the rejection of parents and suspicion of society [5]. For male kindergarten teachers, work is characterized by high emotional consumption, which causes them to bear high work pressure and emotional burden [6]. This weakens the professional identity of male kindergarten teachers, leading to a high proportion of male kindergarten teachers leaving the kindergarten teaching profession [6]. In 2020, the ratio of male to female kindergarten teachers in China was 1:43.9 [7]. The extremely low proportion of male kindergarten teachers has attracted the government's attention. To address this issue, educational policy makers have introduced various favorable policies to attract male kindergarten teachers [[1], [6]]. However, at present, the number of male kindergarten teachers remains insufficient, which has resulted in a lack of quantitative research on male kindergarten teachers, as most existing studies have employed only qualitative research methods, such as interviews and observations [1,8]. Although qualitative research can dissect the deeper reasons for a behavior, it cannot fully present the relation between different variables. Hence, in this study, we did not analyze the reasons for male kindergarten teachers' behaviors in depth but rather sought to establish a mathematical model of the relations among the variables using a quantitative research approach.

Preschool education administrators and researchers have been attempting to improve the retention rate of male kindergarten teachers [9,10]. In this regard, the factors that affect the teachers' retention rate must be investigated. Teachers' occupational commitment is important in solving the problem of teacher turnover in the global education industry [11] by improving the educators' retention rate [12]. Occupational commitment refers to the degree to which an individual is attached to or desires a particular occupational role [13]. Individuals with a high degree of occupational commitment are more likely to devote more efforts to developing their careers, improving their occupational skills, and working more to promote their careers, and are less likely to leave their careers [13]. In other words, occupational commitment has a negative correlation with turnover intention [14]. Additionally, occupational commitment reflects an individual's degree of work enthusiasm [15] and, in kindergarten teachers, is a key indicator of long-term occupational willingness to engage in preschool education [16]. A high level of occupational commitment can help kindergarten teachers improve the standards of early childhood education and care [17]. Therefore, in this study, we aimed to identify effective approaches for improving the retention rate of male kindergarten teachers by exploring the factors influencing their occupational commitment and its underlying mechanisms. We intended to help enhance the stability of male kindergarten teachers [18], optimize the gender structure of kindergarten teachers [19], and promote the healthy growth of children [20].

Human sociality makes individual behaviors inseparable from specific situations and living spaces. Individual behaviors can be influenced by individual cognition of the social environment. Kindergarten organizations, as an important environmental variable, affect the educational and teaching behaviors of male kindergarten teachers as well as their adaptation and development in the workplace. Based on the job demand-resource (JD-R) model, the interactions between individuals and the work environment involve two processes. The first is the energy-driven process (demand-loss for work), and the second is the motivation-driven process (resource-gain for work) [21]. Job demands refer to job-related tasks that require immediate or long-term efforts, whereas job resources can be defined as job-related means that can be utilized by employees when they must deal with job demands [22]. Work resources have motivation characteristics that can stimulate individual motivation and improve work engagement. In this regard, excessive work-demands and lack of work resources will lead to low work performance, low organizational commitment, and other negative organizational results; work resources can cushion the negative impact of work requirements on employees [23].

Perceived organizational support is an important resource in the work environment [24]. It can reduce the physical and psychological costs of individuals; stimulate their growth, learning, and development; and improve their job engagement [23], which has a positive relation with occupational commitment [25]. Therefore, perceived organizational support is an important factor that affects male kindergarten teachers' occupational commitment. However, although existing studies have focused on the impact of perceived organizational support on organizational commitment [26,27], few studies have paid attention to the relation between perceived organizational support and occupational commitment. As society develops rapidly and population mobility increases, individuals tend to become more loyal to a profession than to an organization. Occupational commitment reflects employees' behavioral choices in the current unstable labor environment and can predict employees’ attitudes and behaviors [28].

When individuals perceive support from the organization they work for, then the organization has created a supportive working atmosphere for them, which can make them gain positive emotional experience and become more loyal to the organization and more willing to continue working [24]. Occupational well-being is a type of positive emotional experience generated in the work [29]. The occupational well-being of kindergarten teachers is reflected in the activities of childcare and education, and is significantly positively correlated with occupational commitment [30]. Thus, occupational well-being is not only a protective factor for occupational commitment but also a potential mediating variable between perceived organizational support and occupational commitment.

In addition, the protective-protective model shows that an individual's adaptation is related to the interaction of two protective factors [31]. In other words, the effect of one protective factor on adaptation outcomes (e.g., occupational commitment) may be influenced by another. Individuals with a high degree of job matching have a strong sense of control over their jobs, which can cushion the negative impact of job stress on occupational commitment [32]. According to the JD-R model [23], job requirements place work pressure on employees, which can reduce employees' occupational well-being. Therefore, person–job fit may also be a protective factor for occupational commitment.

Based on the above analysis, we focused on male kindergarten teachers and utilized a quantitative research method to investigate the underlying mechanisms by which perceived organizational support, occupational well-being, and person–job fit affect occupational commitment. Our findings were expected to provide valuable suggestions for improving male kindergarten teachers’ occupational commitment.

2. Literature review and hypotheses development

2.1. Perceived organizational support and occupational commitment

Eisenberger et al. proposed the concept of perceived organizational support in 1986. According to this concept, when employees feel supported by an organization, an implicit obligation develops into a mutual benefit between the employee and the organization, which benefits the organization [33]. Furthermore, educational opportunities, welfare, salary, and position are all key factors affecting the level of perceived organizational support [34]. As organizations are the carriers of occupations, perceived organizational support enables employees to not only realize their value and informal status in an organization but also feel their importance with respect to the occupation [35]. Employees with a high level of perceived organizational support will put more effort into their work, resulting in high work performance [36]. Beneficial feedback, decision-making participation, support from colleagues and leaders in the field are important resources that can enhance teachers' occupational skills and work engagement and allow them to build close relationships with colleagues and students, thus enabling teachers to develop strong connections to their profession and enhance their level of occupational commitment [37]. In the case of individuals facing a high workload, support from the organization plays a powerful role as a resource, helping individuals reduce stress at work, enhance their professional self-efficacy, and improve their physical and mental health [38]. Perceived organizational support can also alleviate the influence of occupational stress on kindergarten teachers’ turnover intention [39]. Moreover, it has the potential to also serve as a mediator between pay-to-return imbalance and turnover intention [35]. Giving recognition, gratitude, and social emotional support to groups or individuals threatened by stereotypes can make them reconsider their intention to leave the profession [24]. Thus, we proposed the following hypothesis.

H1

Perceived organizational support positively predicts occupational commitment.

2.2. Occupational well-being as a potential mediator

Occupational well-being is a type of subjective well-being generated in the workplace and is a positive evaluation of a person's work effect, attitude, behavior, perception, and physical and mental status [29]. Organizations can provide individuals with social and emotional support as well as tangible support in the form of equipment, funds, and kind assistance to help employees obtain positive emotional experiences and thus become more loyal and committed to the organization and more willing to continue their current work [24]. Social support, income, physical and mental experiences, and value realization are important factors that affect occupational well-being [40]. Moreover, according to the conservation of resources theory [41], to obtain valuable resources conducive to their own development, such as positive emotional experiences, people tend to identify with organizations that can give them positive evaluations. Hence, when organizations meet their employees' emotional needs, they can increase employees' willingness to remain with the organization. In the case of teachers, their occupational well-being helps them conduct teaching work creatively, construct their self-identity, and build good relationships with students, thus promoting the smooth realization of educational reform and improving student achievement [3,42]. Indeed, occupational well-being is an important predictor of teacher burnout and attrition rates [43]. The occupational well-being of kindergarten teachers can promote an emotional connection between kindergarten teachers and their profession and has significant predictive power for their occupational commitment [44]. However, previous research has found that the overall level of occupational well-being of male kindergarten teachers is low [45]. Therefore, we postulated the following hypothesis.

H2

Occupational well-being mediates the relation between perceived organizational support and occupational commitment.

2.3. Person–job fit as a potential moderator

Person–job fit refers to the alignment between individuals' expertise, abilities, and values with the work they do [46]. According to the trait and factor theory of Parsons [47], personality is unique; each occupation needs to match a specific personality type; and individuals are more likely to succeed in their careers when choosing an occupation that matches their personality traits. Research on public servants has found that person–job fit is significantly positively correlated with occupational commitment [47]. Additionally, the matching between people and positions is a prerequisite for individuals to experience happiness [48]. Conversely, the mismatch between workplace characteristics and individual skills or preferences becomes an important stressor that negatively affects individuals’ emotional experiences [49]. Nonetheless, person–job fit can change over time, affected by individual traits, external interpersonal interactions, and other factors [4]. Based on the “lack of match” model within social psychology theory, the behavior patterns exhibited by individuals of different sex do not align with the factors that are indicative of their success within a specific professional domain [50]. Therefore, in preschool education institutions dominated by female teachers, the match between male kindergarten teachers and their positions is deemed to counter the traditional idea of the natural suitability of women for raising children and is thus controversial. Male kindergarten teachers may even deal with doubts about their motivation to engage in early childhood education [51].

Person–job fit and occupational well-being are protective factors for occupational commitment. The protective-protective model holds that two protective factors may interact to predict people's adaptation results, and two hypotheses are proposed to explain how these two protective factors work together: the enhancing and antagonistic interaction hypotheses [31]. The enhancing interaction hypothesis states that the effect of one protective factor on adaptive outcomes may be enhanced by another protective factor. Conversely, the antagonistic interaction hypothesis states that the effect of one protective factor on adaptive outcomes may be reduced by another protective factor. In kindergarten education, it is unclear how the interaction between person–job fit and occupational well-being affects male kindergarten teachers' occupational commitment. Therefore, we explored the moderating effect of person–job fit on the relation between occupational well-being and occupational commitment without explicitly assuming the moderating direction of person–job fit. Therefore, we put forward the following hypothesis.

H3

Person–job fit moderates the predictive effect of occupational well-being on occupational commitment.

2.4. Current study

By constructing a moderated mediation model (Fig. 1), we analyzed the predictive effect of perceived organizational support on occupational commitment, the mediating effect of occupational well-being on the relation between perceived organizational support and occupational commitment, and the moderating effect of person–job fit on the relation between occupational well-being and occupational commitment.

Fig. 1.

Proposed research model.

3. Materials and methods

3.1. Participants and procedure

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Guangxi Normal University (IRB NO. ZS025). We calculated the required sample size as follows. Given that the total number of male kindergarten teachers in China is less than 70,000 [7], we set the total number to 70,000 based on the formula for calculating the sample size (Formula 1) [52], which showed that we needed a minimum of 383 participants to meet the objectives of our study.

Formula 1. Sample size

We used a convenience sampling method to send the questionnaire link to male kindergarten teachers using a WeChat group of preschool education graduates from eight Chinese universities after obtaining permission from the department chairs of the eight universities. Male kindergarten teachers completed the online questionnaire on a voluntary basis and were asked to read the privacy statement of the study in detail before completing the questionnaire. Finally, 413 male kindergarten teachers from 21 of China's 34 provincial-level administrative regions agreed to participate in this study. Ultimately, we obtained 402 (>383, see Formula 1) valid questionnaires (Table 1), with a valid questionnaire rate of 97%.

Table 1.

Demographics of the participants (N = 402).

| Basic data | Item | Number (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Workplace | Urban | 262 (65.17%) |

| Non-urban | 140 (34.83%) | |

| Nature of institution | Public school | 254 (63.18%) |

| Private school | 148 (36.82%) | |

| Daily working hours | 8 h or less | 175 (43.53%) |

| 8–10 h | 192 (47.76%) | |

| 10–11 h | 29 (7.21%) | |

| 11 h or more | 6 (1.49%) | |

| Grade | Kindergarten junior class | 126 (31.34%) |

| Kindergarten middle class | 82 (20.40%) | |

| Kindergarten senior class | 194 (48.26%) | |

| Education | Secondary technical school graduates | 101 (25.12%) |

| Junior college | 113 (28.11%) | |

| Bachelor | 156 (38.81%) | |

| Postgraduate | 32 (7.96%) | |

| Years of teaching experience | 0–1 | 121 (30.10%) |

| 2–5 | 194 (48.26%) | |

| 6–10 | 59 (14.68%) | |

| 11–20 | 16 (3.98%) | |

| 20 + | 12 (2.99%) | |

| Average monthly income (RMB) | <2000 | 85 (21.14%) |

| 2000–3000 | 138 (34.33%) | |

| 3000–4000 | 78 (19.40%) | |

| 4000–5000 | 51 (12.69%) | |

| 5000–10,000 | 35 (8.71%) | |

| >10,000 | 15 (3.73%) | |

| Age (years) | 18–25 | 206 (51.24%) |

| 26–35 | 147 (36.57%) | |

| 36–45 | 36 (8.96%) | |

| 46 + | 13 (3.23%) | |

| Certification | Have | 282 (70.1%) |

| Do not have | 120 (29.9%) |

3.2. Measures

3.2.1. Person–Job Fit Scale

We measured person–job fit using the Person–Job Fit Scale revised by Wong [53]. The scale consists of four items, including the statement “The work environment provided by the unit matches my job requirements.” The tool uses a five-point Likert scale (1 = complete disagreement, 5 = complete agreement). Higher scores indicated higher person–job fit. This scale can be used in kindergarten teachers [54]. The scale showed adequate reliability (α = 0.86, composite reliability, CR = 0.86) and validity average variance extracted (AVE = 0.62).

3.2.2. Perceived Organizational Support Scale

We measured perceived organizational support using the Perceived Organizational Support Scale revised by Liu et al. [55]. This scale comprises six items, including “The organization will consider my opinion.” The tool uses a five-point Likert scale (1 = complete disagreement, 5 = complete agreement). Higher scores indicated greater perceived organizational support. This scale can be used in kindergarten teachers [54]. The scale showed adequate reliability (α = 0.90, CR = 0.90) and validity (AVE = 0.61).

3.2.3. Occupational Well-Being of Kindergarten Teachers Scale

We measured occupational well-being using the Occupational Well-Being of Kindergarten Teachers Scale revised by Wang [43]. The scale has 15 items, including the four subscales of cognitive, psychological, emotional, and social well-being. An example item is “I feel I can control my work.” The tool uses a three-point Likert scale (1 = complete disagreement, 3 = complete agreement), with higher scores indicating higher levels of occupational well-being. The scale showed adequate reliability (α = 0.91, CR = 0.94) and validity (AVE = 0.51).

3.2.4. Teacher Occupational Commitment Scale

We measured occupational commitment using the Teacher Occupational Commitment Scale developed by Long and Li [56]. The scale contains 16 items, including “I feel responsible to continue for the realization of my career,” covering the three subscales of normative, emotional, and continued commitment. The tool uses a four-point Likert scale (1 = complete disagreement, 4 = complete agreement); the higher the score, the higher the level of occupational commitment. This scale can be used in kindergarten teachers [30]. The scale showed adequate reliability (α = 0.92, CR = 0.94) and validity (AVE = 0.50).

3.3. Data analysis

We used IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 23.0, and AMOS 24.0, to organize and analyze the data. In the first step, we identified differences in the scoring criteria that could be attributed to differences in the scales used (the three-point scale of the Occupational Well-Being Scale, the four-point scale of the Occupational Commitment Scale, and the five-point scale of the Person–Job Fit and Perceived Organizational Support Scales). To maintain the consistency of the scoring criteria, we used SPSS to convert the data of both the Occupational Well-Being and Occupational Commitment Scales into five-point scale data through the following formula: Y (B-A) * (x-a)/(b-a) + A [57].

Next, we calculated the value of Cronbach's α using SPSS 23.0 and used the value of Cronbach's α above 0.70 as a criterion to evaluate the reliability of our study [58]. Additionally, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was performed using AMOS 24.0. We used χ2/df < 3, CFI >0.90, TLI >0.90, and RMSEA <0.08 as the criteria for measuring construct validity [14]. The fit indices of the four-factor model were compared with those of other models, and the significant difference was used as the criterion to evaluate the discriminant validity of the model (Δχ2; >3.84, >6.64, or >10.83) [14]. We applied the AVE and CR to evaluate convergent validity, where the values of AVE above 0.50 and CR above 0.70 indicated good convergent validity [59].

The next step involved conducting difference tests (t-test and F-test) and correlation analysis. Finally, we used Model 4 in PROCESS v3.3, a plug-in for SPSS, to analyze the mediating effect, and Model 14 to analyze the moderated mediation effect.

4. Results

4.1. Reliability and validity of measurement

The results of the CFA showed that the four-factor model (person–job fit, perceived organizational support, occupational well-being, and occupational commitment) had the best fit; the fit indices were at an acceptable level (Table 2). The chi-squared difference values between the four-factor model and other models were statistically significant (Δχ2 > 10.83, p < 0.001).

Table 2.

Confirmatory factor analysis results.

| Model | χ2 | df | χ2/df | Δχ2 (Δdf) | CFI | TLI | RMSEA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Four-factor model | 2061.932 | 773 | 2.667 | – | 0.912 | 0.934 | 0.034 |

| Three-factor modela | 2968.938 | 776 | 3.826 | 907 (3) *** | 0.859 | 0.846 | 0.084 |

| Two-factor modelb | 3944.864 | 778 | 5.071 | 975.93 (5) *** | 0.834 | 0.852 | 0.101 |

| One-factor modelc | 5180.275 | 780 | 6.641 | 1235.41 (7) *** | 0.517 | 0.492 | 0.119 |

CFI: Comparative Fit Index; TLI: Tucker–Lewis Index; RMSEA: root mean square error of approximation; Δχ2: chi-squared difference value; Δdf: degrees of freedom difference value; ***: p < 0.001.

This model combines person–job fit and perceived organizational support into a single factor.

This model combines person–job fit, perceived organizational support, and occupational well-being into one factor.

This model combines person–job fit, perceived organizational support, occupational well-being, and occupational commitment into one factor.

As shown in Table 3, the AVE of each variable in the four-factor model was above 0.50, and the CR values were all above 0.70. The correlation coefficients among occupational commitment, person–job fit, perceived organizational support, and occupational well-being were significant. Further, the Cronbach's α for each variable was above 0.70. Hence, this study had good reliability and validity.

Table 3.

Reliability and convergent validity (N = 402).

| Cronbach's α | AVE | CR | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Person–job fit | 0.86 | 0.62 | 0.86 |

| Perceived organizational support | 0.90 | 0.61 | 0.90 |

| Occupational well-being | 0.91 | 0.51 | 0.94 |

| Occupational commitment | 0.92 | 0.50 | 0.94 |

Simultaneously, to eliminate the common method variance caused by self-reported data collection, we used Harman's single-factor test to evaluate common method variance [60]. The results showed that the characteristic roots of the eight factors were greater than 1, and the variance contribution rate of the first factor was 31.66% (less than 40%), indicating that the study had no serious common method variance.

4.2. Descriptive statistics and correlations of study variables

We found significant positive correlations among occupational commitment, person–job fit, occupational well-being, and perceived organizational support (Table 4).

Table 4.

Descriptive statistics and correlation analysis (N = 402).

| M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Person–job fit | 11.98 | 3.46 | – | ||

| 2. Perceived organizational support | 18.81 | 4.79 | 0.57*** | – | |

| 3. Occupational well-being | 48.86 | 10.41 | 0.35*** | 0.45 *** | – |

| 4. Occupational commitment | 54.48 | 10.08 | 0.44*** | 0.45*** | 0.52*** |

Note: ***p < 0.001.

4.3. Mediation model

We analyzed the mediating effect using the PROCESS 3.3 macro (Model 4) of SPSS 23.0 with 5000 bootstrap samples. The results of the difference tests (t-test and F-test) showed that six demographic variables (grade, education, years of teaching experience, average monthly income, age, and certification) significantly affected the scores of male kindergarten teachers in occupational commitment, person–job fit, perceived organizational support, and occupational well-being. Therefore, we set grade, education, years of teaching experience, average monthly income, age, and certification as control variables.

The results showed that perceived organizational support significantly and positively predicted occupational commitment (β = 0.41, 95%CI = [0.33, 0.50]) in the absence of mediating effects. Additionally, as shown in Table 5, perceived organizational support significantly positively predicted occupational well-being (β = 0.44, 95%CI = [0.35, 0.52]), occupational well-being significantly positively predicted occupational commitment (β = 0.40, 95%CI = [0.31, 0.49]), and perceived organizational support significantly positively predicted occupational commitment (β = 0.24, 95%CI = [0.15, 0.33]). As shown in Table 6, the indirect effect value was 0.17, accounting for 41.46%, and the 95%CI excluded 0, indicating that occupational well-being partially mediated the relation between perceived organizational support and occupational commitment.

Table 5.

Mediation analysis (N = 402).

| Predictor variable | Occupational well-being |

Occupational commitment |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | SE | 95% CI | β | SE | 95% CI | |

| Perceived organizational support | 0.44*** | 0.04 | [0.35, 0.52] | 0.24*** | 0.05 | [0.15, 0.33] |

| Occupational well-being | 0.40*** | 0.05 | [0.31, 0.49] | |||

| R | 0.50 | 0.60 | ||||

| R2 | 0.25 | 0.36 | ||||

| F | 18.74*** | 27.28*** | ||||

Note: *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001; CI: confidence interval.

Table 6.

Decomposition of total, direct, and indirect effects.

| Effect | Effect value | Boot SE | 95% CI | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total effect | Perceived organizational support → occupational commitment | 0.41 | 0.04 | [0.33, 0.50] | |

| Direct effect | Perceived organizational support → occupational commitment | 0.24 | 0.05 | [0.15, 0.33] | 58.54% |

| Indirect effect | Perceived organizational support → occupational well-being → occupational commitment | 0.17 | 0.03 | [0.11, 0.24] | 41.46% |

4.4. Moderated mediation model

We analyzed the moderated mediation effect using the PROCESS 3.3 macro (Model 14) of SPSS 23.0 with 5000 bootstrap samples. We set grade, education, years of teaching experience, average monthly income, age, and certification as control variables.

As shown in Table 7 and Fig. 2, the interaction terms of person–job fit and occupational well-being had a significant predictive effect on occupational commitment (β = −0.10, 95%CI = [−0.16, −0.04]). Thus, person–job fit had a moderating effect on the latter half of the intermediary path of “perceived organizational support → occupational well-being → occupational commitment.”

Table 7.

Results of the moderated mediation effect (N = 402).

| Dependent variable | Predictor variable | β | SE | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Occupational commitment | Perceived organizational support | 0.13* | 0.06 | [0.01, 0.24] |

| Occupational well-being | 0.36*** | 0.05 | [0.27, 0.45] | |

| Person–job fit | 0.18*** | 0.05 | [0.08, 0.29] | |

| Person–job fit × occupational well-being | −0.10** | 0.03 | [-0.16, −0.04] | |

| R | 0.62 | |||

| R2 | 0.39 | |||

| F | 24.72*** | |||

Note: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001; CI: confidence interval.

Fig. 2.

Model testing results.

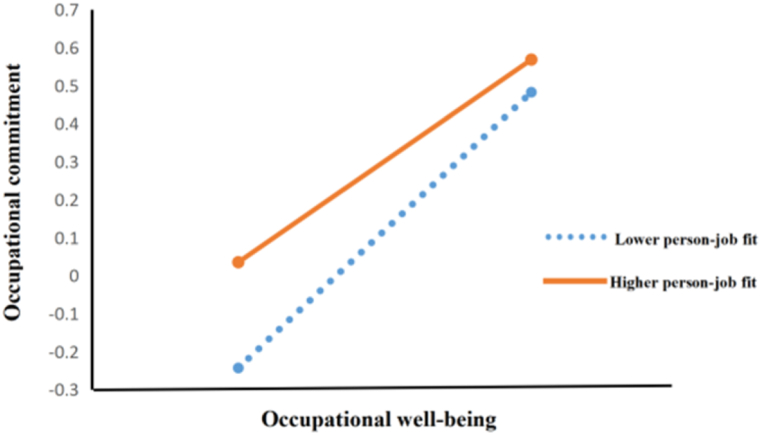

To reflect the moderating effect of person–job fit more intuitively, we divided the person–job fit scores into high and low groups (average plus or minus one standard deviation), performed a simple slope analysis, and drew a simple effect analysis graph (Fig. 3). The results showed that when male kindergarten teachers' person–job fit degree was low (−1 SD), the effect of occupational well-being on occupational commitment was greater (βsimple = 0.50, p < 0.001), with a 95% confidence interval of [0.39, 0.61]. Conversely, when male kindergarten teachers’ person–job fit was high (+1 SD), the effect of occupational well-being on occupational commitment was small (βsimple = 0.29, p < 0.001), with a 95% confidence interval of [0.18, 0.39].

Fig. 3.

Effect of occupational well-being on occupational commitment at different levels of person–job fit.

5. Discussion

This study investigated the potential mechanisms through which perceived organizational support, occupational well-being, and person–job fit influence the occupational commitment of male kindergarten teachers. By analyzing the mediating effect of occupational well-being, we elucidated the indirect effect of perceived organizational support on occupational commitment and the moderating effect of person–job fit on this indirect effect. The results confirmed the theoretical model proposed, namely, perceived organizational support directly predicted occupational commitment. Additionally, perceived organizational support indirectly predicted occupational commitment through the mediating effect of occupational well-being. We also confirmed that person–job fit moderated the predictive effect of occupational well-being on occupational commitment.

5.1. Perceived organizational support positively predicting occupational commitment

Our results showed that perceived organizational support positively predicted kindergarten teachers' occupational commitment, in line with earlier research [24]. The characteristics of the physical and mental developmental stages of preschool children make kindergarten teachers’ work prone to sudden changes. During their work, kindergarten teachers expend a great deal of emotional energy, which puts them in a constant state of high emotional labor. Without support from external resources, they are prone to emotional exhaustion [3]. However, kindergarten teachers receive low organizational support and have to rely on family support [6]. As work stress accumulates and resource depletion outweighs supply, kindergarten teachers may be compelled to tend to leave [21]. According to the JD-R model [23], improving the retention rate of kindergarten teachers involves providing them with adequate organizational support (e.g., setting up one-to-one guidance groups) rather than attempting to change their cognition and acceptance of their work environment. Perceiving staunch support from the organization is a significant resource for male kindergarten teachers, boosting their confidence in coping with the exhausting demands of the job and giving them greater control over their work [61]. Additionally, organizational support can help male kindergarten teachers balance the pressure brought by work requirements, reduce their physical and psychological costs, better conduct childcare and education activities, and enhance their willingness to continue working as kindergarten teachers [62]. Simultaneously, the perceived support from kindergarten organizations can function as a motivator, enabling male kindergarten teachers to engage in their work with more enthusiasm [21] and improve their professional skills. The improvement of professional skills can help alleviate the tension caused by the demands of multiple roles for male kindergarten teachers and realize the identity transformation from “male” to “male kindergarten teacher” to “teacher,” thus weakening the negative impact of gender stereotypes and stimulating their commitment to continue to be kindergarten teachers.

5.2. Mediating role of occupational well-being

Our results showed that occupational well-being partially mediated the relation between perceived organizational support and occupational commitment, which is consistent with the research results of Wang and Wu [63]. The public perception of kindergarten teachers as “glorified babysitters” rather than teachers in the true sense of the word has led to the marginalization of kindergarten teachers' work and the “invisibility of job complexity” [64], resulting in a dilemma of low social status and income for kindergarten teachers. Low social status and income not only reduce the occupational well-being of kindergarten teachers but also lead to men's reluctance to work as kindergarten teachers [1,62]. Male kindergarten teachers represent a small minority. According to the theory of social isolation [65], being the only male kindergarten teacher in a certain kindergarten or preschool education group could result in a sense of workplace alienation during the process of work due to gender differences. Therefore, the perceived support from the kindergarten organization satisfies the male kindergarten teachers' need for a sense of belonging and self-worth in the female-dominated work field, generating a positive emotional experience of “inner warmth” and enhancing the individual's internal psychological resources. When resources are greater than energy consumption, individuals will be in a state of resource income, which will improve occupational well-being [66]. Moreover, such positive emotional experiences increase male kindergarten teachers' sense of job identity [58], thus enhancing occupational commitment [67]. According to the broaden-build theory [68], occupational well-being, as a positive experience derived from one's occupation, not only has the function of instantaneous expansion but also of long-term construction. Occupational well-being can hence help male kindergarten teachers build physical, cognitive, social, and other resources that can help them be more secure, active, and creative when conducting childcare and educational activities. This can bring long-term benefits, such as improvements in work performance and income levels. Moreover, it can enhance the external and internal motivation of male kindergarten teachers' professional commitment. Thus, they can enter a virtuous circle of sustainable development.

5.3. Moderating role of person–job fit between occupational well-being and occupational commitment

Our results showed that person–job fit negatively moderated the predictive effect of occupational well-being on occupational commitment, thus supporting the antagonistic interaction hypothesis of the protective-protective model [31]. In other words, one protective factor may reduce the influence of another protective factor. The reason for this result may be that person–job fit and occupational well-being, as protective factors of occupational commitment, can produce compensatory effects. That is, high person–job fit can enhance the occupational commitment of male kindergarten teachers with low occupational well-being, whereas an elevated level of occupational well-being can mitigate the negative effects of low person–job fit on occupational commitment. According to social role theory [1], although early socialization may result in males lacking certain competencies required to be kindergarten teachers, males can acquire sufficient experience through participation, experience, learning, and training. Thus, they can perform competently as kindergarten teachers and make social contributions matching their professional status. When male kindergarten teachers have a high degree of matching with their jobs (e.g., male kindergarten teachers have acquired knowledge about gender in their pre-service education and can deconstruct gender stereotypes), they do not need to spend too much extra time learning while still being qualified for kindergarten teaching work. As such, the psychological load of male kindergarten teachers will be reduced such that they do not need to spend too much psychological resources, such as occupational well-being, and can still have the motivation to continue working.

Simultaneously, person–job fit is characterized by a dynamic adjustment process based on the interaction between individuals and their work environment. When the work environment meets the developmental needs of male kindergarten teachers, their subjective initiative is stimulated, prompting them to gradually improve their ability according to the job requirements [4]. However, the development rate of kindergartens falls behind the progress rate of teachers, and the professional ceiling of kindergarten teachers has been noted. According to the need–supply model [69], when the ability of male kindergarten teachers is continuously enhanced, their existing work environment may not be able to meet their needs to realize the value of life, making it easy for male kindergarten teachers to leave their current position or even the entire occupation. To address this concern, school managers must transcend the limitations of professional development for kindergarten teachers by implementing personalized post design, thereby affording capable male kindergarten teachers with increased opportunities to showcase their professional worth.

6. Conclusions

Taking male kindergarten teachers as the research subjects, our study demonstrated that perceived organizational support can positively predict occupational commitment, and that occupational well-being plays a mediating role in the relation between perceived organizational support and occupational commitment. Additionally, person–job fit negatively moderates the predictive effect of occupational well-being on occupational commitment. Therefore, improving the perceived organizational support and occupational well-being of male kindergarten teachers can help enhance their occupational commitment. Further, person–job fit plays a negative moderating role in the relation between occupational well-being and occupational commitment, indicating a mutually compensatory relation between person–job fit and occupational well-being. Specifically, a heightened level of person–job fit can enhance the occupational commitment of male kindergarten teachers experiencing low levels of occupational well-being.

6.1. Implications

6.1.1. Theoretical implications

Our research has substantial theoretical implications. First, it enriches the quantitative research on male kindergarten teachers. Owing to the small number of male kindergarten teachers, researchers have had difficulty conducting quantitative research on large samples, leading to a serious shortage of quantitative research on male kindergarten teachers [6]. Hence, our study alleviates this shortage. Second, our results showed that perceived organizational support positively predicts occupational well-being and occupational commitment, thus supporting the motivational process of job resources in the JD-R model, that is, job resources contribute to positive job outcomes [22].

6.1.2. Practical implications

In terms of practical implications, our results provide preschool education policymakers and kindergarten managers with valuable insights and effective methods to enhance the occupational commitment of male kindergarten teachers. First, our study confirmed that perceived organizational support plays a positive role in improving the occupational commitment of male kindergarten teachers. Therefore, kindergarten managers need to create an inclusive and equal work environment and give full play to the positive role of kindergarten organizations in improving male kindergarten teachers' occupational commitment. Second, we demonstrated that perceived organizational support can positively impact occupational commitment by improving preschool teachers' occupational well-being. Hence, preschool policymakers and kindergarten managers should pay close attention to the balance between the job requirements and job resources of male kindergarten teachers to help the latter experience occupational well-being from their work. Third, we confirmed the mutually compensatory relation between person–job fit and occupational well-being. Consequently, to enhance the occupational commitment of male kindergarten teachers, managers and educators can increase male kindergarten teachers’ person–job fit by nurturing their experience, skills, and knowledge to align with job requirements. Moreover, creating a work environment that caters to the specific needs of male kindergarten teachers and recruiting individuals with suitable interests, personalities, and temperaments can further contribute to improving person–job fit.

6.2. Limitations and future research directions

Although the sample size and study design used in our study were sufficient to achieve the research objectives, our research nonetheless had the following five limitations, which also provide directions for future research. First, our findings were based on a sample of male Chinese kindergarten teachers. Hence, whether our results can be generalized to other groups or male kindergarten teachers in other cultural settings requires further research to enhance the persuasiveness of the model. Second, we used a self-report method for data collection, which may have generated measurement errors attributable to social desirability bias. In future, we plan to design questionnaires from the perspectives of leaders, colleagues, and family members to study the factors affecting the occupational commitment of male kindergarten teachers. Third, our results showed that occupational well-being only partially mediated the impact of perceived organizational support on occupational commitment. Future research can further explore other mediating factors, such as job burnout, sense of occupational mission, sense of belonging, and professional identity, to broaden the research on the reasons male kindergarten teachers with higher perceived organizational support have a higher degree of occupational commitment. Fourth, the study design could not determine causality. In the future, longitudinal studies can be conducted to elucidate the development of occupational commitment, perceived organizational support, occupational well-being, and person–job fit of male kindergarten teachers at different career stages through multiple data collection procedures for each variable. Cross-hysteresis analysis can be used to clarify the causal relationship between variables. Fifth, our results demonstrated that person–job fit negatively moderated the predictive effect of occupational well-being on occupational commitment. This result not only provides empirical evidence for the antagonistic interaction hypothesis of the protective–protective model but also has implications for researchers. As scholars, it is crucial to acknowledge that the effectiveness of organizations and management in the workplace is contingent upon the intricate interplay of various factors. Hence, scholars must undertake a comprehensive investigation into the interconnections among these variables across diverse contexts.

Funding

This study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Project Approval No. 32060197).

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Guangxi Normal University (IRB NO. ZS025). All participants provided informed consent to participate in the study.

Author contribution statement

Shuyue Zhang: Conceived and designed the experiments; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Weiwei Huang: Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Wrote the paper.

Hui Li: Analyzed and interpreted the data; Wrote the paper.

Data availability statement

Data will be made available on request.

Full questionnaire

Basic information

Please fill in the following questions or put a tick in front of the option that matches your situation.

-

1.

Your work location: (1) urban (2) non-urban

-

2.

Type of kindergarten you are attending: (1) Public (2) Private

-

3.

The grade you teach: (1) Junior class (2) Middle class (3) Senior class

-

4.

Your average working hours per day

(1) 8 h or less (2) 8–10 h (3) 10–11 h (4) 11 h or more

-

5.

Your highest education: (1) Secondary technical school graduates (2) Junior college (4) Bachelor (5) Postgraduate

-

6.

Your years of teaching experience: (1) 0–1 year (2) 2–5 years (3) 6–10 years (4)11–20 years (5) 20 years or more

-

7.

Your average monthly income (RMB).

(1) Less than 2000 (2) 2000–3000 (3) 3000–4000 (4) 4000–5000 (5) 5000–10,000 (6) 10,000 yuan or more

-

8.

Your age: (1) 18–25 years old (2) 26–35 years old (3) 36–45 years old (4) 45 years old or older

-

9.

Do you have a certification to work in kindergarten: (1) Yes (2) No

Person-job, Person-job Fit Scale

| Complete disagreement | Comparisons do not match | Somewhat in line with | More in line with | Complete agreement | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | I feel like I am a perfect match for my current job | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 2 | The requirements of my current job match the experience, skills, and knowledge I possess | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 3 | The work environment provided by the unit matches my job requirements. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 4 | My personality and temperament traits match my work | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

Perceived Organizational Support Scale

| Complete disagreement | Comparisons do not match | Somewhat in line with | More in line with | Complete agreement | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | The organization will consider my opinion | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 2 | The unit considers my interests | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 3 | The unit respects my goals and values | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 4 | The unit will help me if I ask for it | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 5 | The unit is happy to help | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 6 | The unit is very concerned about me | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

Occupational Well-being Scale

| Complete disagreement | More in line with | Complete agreement | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | I can do my part well | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 2 | I feel I can control my work | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 3 | I feel responsible for the work of the kindergarten | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 4 | The daily work makes me feel like I am the most important | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 5 | I often feel happy in my work | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 6 | I often have a sense of warmth in my work | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 7 | I am a happy person at work | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 8 | My kindergarten gives me a sense of well-being | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 9 | I like everyone in this kindergarten | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 10 | I have a friendly relationship with my colleagues | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 11 | I am approachable with young children. | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 12 | I am satisfied with the work I have undertaken so far | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 13 | I am satisfied with the current working environment | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 14 | I am satisfied with the salary of my current job | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 15 | Overall, I am satisfied with my current job | 1 | 2 | 3 |

Occupational Commitment Scale

| Complete disagreement | Comparisons do not match | More in line with | Complete agreement | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | I feel proud to be in my current profession | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 2 | Enthusiastic about the work you are doing now | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 3 | Like the current occupation so much that it is difficult to give up | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 4 | My current occupation provides me with the opportunity to do what I am interested in | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 5 | My current occupation will enable me to improve my working ability | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 6 | My current occupation gives me room to develop and better realize my self-worth | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 7 | I must pay too high a price for changing my occupation right now | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 8 | If you leave your current occupation, you will lose many benefits, such as housing, schooling for your children, and retirement insurance. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 9 | If I leave my current occupation, it will bring loss to my family | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 10 | Difficulty in finding a better occupation due to the limitations of the field of study | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 11 | Once I leave my current occupation, the biggest problem is that it is difficult to find another job | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 12 | If you do a job, you should love it | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 13 | I believe that people who have received education or training in a profession should work in that profession for a period in order to make a commensurate contribution | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 14 | I feel responsible to continue for the realization of my career | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 15 | I do not think it is right to leave my current occupation, even if it is good for me | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 16 | Stay in the current profession because everyone must be loyal to the profession | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank all the participants who agreed to participate in the study.

References

- 1.Okeke C.I., Nyanhoto E. Recruitment and retention of male educators in preschools: implications for teacher education policy and practices. S. Afr. J. Educ. 2021;41(2):1910. doi: 10.15700/saje.v41n2a1910. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gørtz M., Johansen E.R., Simonsen M. Academic achievement and the gender composition of preschool staff. Lab. Econ. 2018;55:241–258. doi: 10.1016/j.labeco.2018.10.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang L.M. China Social Science Press; 2019. What Makes a Teacher. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gao Z.H. China Light Industry Press; 2011. Understanding Career: Nine Career Metaphors You Must Understand. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Warming K. Men who stop caring: the exit of men from caring occupations, Nord. J. Working Life. 2013;3(4):5–20. doi: 10.19154/njwls.v3i4.3070. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hong X.M., Zhao S.J., Zhang M.Z. How to solve the predicament of the loss of kindergarten teachers. Mod. Educ. Manag. 2021;1:69–75. doi: 10.16697/j.1674-5485.2021.01.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yao Z.R. Minnan Normal University; China: 2022. A Case Biography Study of Male Preschool Teachers' Professional Identity, Unpublished PhD Dissertation. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haller R., Tavecchio L.W.C., Stams G.J.J.M., Van Dam L. Educate the child according to his own way: a Jewish ultra-orthodox version of independent self-construal. J. Beliefs Values. 2023;3:1–15. doi: 10.1080/13617672.2023.2184128. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barkhuizenm N. Exploring the importance of rewards as a talent management tool for generation y employees. Mediterr. J. Soc. Sci. 2014;5(27):1100–1105. doi: 10.5901/mjss.2014.v5n27p1100. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang C., Liu Z.H., Han Y. Conflict and adaptation: a study on the identity construction of male kindergarten teachers from a gender perspective. J. China Women Univ. 2023;35(4):119–128. doi: 10.13277/j.cnki.jcwu.2023.04.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.García E., Weiss E. The teacher shortage is real, large and growing, and worse than we thought. 2019. https://www.epi.org/publication Available at:

- 12.Klassen R.M., Chiu M.M. The occupational commitment and intention to quit of practicing and pre-service teachers: influence of self-efficacy, job stress, and teaching context. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2011;36(2):114–129. doi: 10.1016/j.cedpsych.2011.01.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hackett R.D., Lapierre L.M., Hausdorf P.A. Understanding the links between work commitment constructs. J. Vocat. Behav. 2001;58(3):392–413. doi: 10.1006/jvbe.2000.1776. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang A.Q., Tang C.H., Zhou L.F., Lv H.Y., Song J., Chen Z.M., Yin W.Q. How surface acting affects turnover intention among family doctors in rural China: the mediating role of emotional exhaustion and the moderating role of occupational Commitment. Hum. Resour. Health. 2023;21(3) doi: 10.1186/s12960-023-00791-y. 2–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mérida-López S., Extremera N., Chambel M.J. Linking self and other focused emotion regulation abilities and occupational commitment among pre-service teachers: testing the mediating role of study engagement. Int. J. Env. Res. Pub. He. 2021;18(10):5434. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18105434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cheng L., Gan Y. Psychological capital and occupational commitment of Chinese urban preschool teachers mediated by work-related quality of life. Soc. Behav. Pers. 2020;48(5) doi: 10.2224/sbp.8905. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee H.M., Chou M.J., Chin C.H., Wu H.T. The relationship between psychological capital and professional commitment of preschool teachers: the moderating role of working years. Universal. J. Educ. Res. 2017;5(5):891–900. doi: 10.13189/ujer.2017.050521. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Su Y.R., Xie H. Research on the demand and satisfaction of male teachers in some public kindergartens in Chengdu. Journal of Qiqihar Junior Teachers’ College. 2022;3:17–19. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1009-3958.2022.03.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Suo C.Q., Wang Y. Break through the feminization barriers in the gender structure of kindergarten teachers: strategies of encouraging more males to work in Norwegian early childhood education and care. J. Comp. Educ. 2021;2:134–149. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.2096-7810.2021.02.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huang H.B. 2019. Research on the Causes and Countermeasures of the Loss of Male Teachers in Kindergartens, Elem. Educ.Stud.17; pp. 26–28. 10.3969/j.issn.1002-3275.2019.17.008. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Singh M., James P.S., Paul H., Bolar K. Impact of cognitive-behavioral motivation on student engagement. Heliyon. 2022;8(7) doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e09843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ji T.C., De Jonge J., Taris T.W., Kawakami N., Peeters M.C.W. Walking the tightrope between work and home: the role of job/home resources in the relation between job/home demands and employee health and well-being. Ind. Health. 2023;61(1):24–39. doi: 10.2486/indhealth.2021-0276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bakker A.B., Demerouti E. Job demands–resources theory: taking stock and looking forward. J. Occup. Health. Psych. 2017;22(3):273–285. doi: 10.1037/ocp0000056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Singh R., Zhang Y.J., Wan M., Fouad N.A. Why do women engineers leave the engineering profession? The roles of work-family conflict, occupational commitment, and perceived organizational support. Hum. Resour. Manage-US. 2018;57(4):901–914. doi: 10.1002/hrm.21900. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Son S., Kim D.Y. Organizational career growth and career commitment: moderated mediation model of work engagement and role modeling. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Man. 2021;32(20):4287–4310. doi: 10.1080/09585192.2019.1657165. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Su X.L., Xu Y., Qiang M. The effect of perceived organizational support for safety and organizational commitment on employee safety behavior: a meta-analysis. Int. J. Occup. Saf. Ergo. 2021;27(4):1154–1165. doi: 10.1080/10803548.2019.1694778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Firmansyah A., Junaedi I.W.R., Kistyanto A., Azzuhri M. The effect of perceived organizational support on organizational citizenship behavior and organizational commitment in public health center during COVID–19 pandemic. Front. Psychol. 2022;13 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.938815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huang W., Yuan C., Li M. Person–job fit and innovation behavior: roles of job involvement and career commitment. Front. Psychol. 2019;10:1134. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.van Horn J.E., Taris T.W., Schaufeli W.B., Schreurs P.J.G. The structure of occupational well-being: a study among Dutch teachers. J. Occup. Organ. Psych. 2004;77:365–375. doi: 10.1348/0963179041752718. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang G., Huang X., Lu X., Zhang D.J. Effects of occupational commitment on job performance among kindergarten teachers: mediating effect of occupational well-being. Psychol. Dev. Educ. 2015;31(6):753–760. doi: 10.16187/j.cnki.issn1001-4918.2015.06.15. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu Q.Q., Zhou Z.K., Yang X.J., Kong F.C., Sun X.J., Fan C.Y. Mindfulness and sleep quality in adolescents: analysis of rumination as a mediator and self-control as a moderator. Pers. Indiv. Differ. 2018;122:171–176. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2017.10.031. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yang D.M., Kim R.H., Su K.K. The effect of job characteristics on organizational commitment: the moderating effect of person-job fit. J. CEO. Manag. Stud. 2019;22(2):237–260. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Eisenberger R., Huntington R., Hutchison S., Sowa D. Perceived organizational support. J. Appl. Psychol. 1986;71(2):500–507. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.71.3.500. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lin X.J. Relationship between faculty perceived organizational support and development motivation: the mediating role of basic psychological needs. Chin. J. Health. Psychol. 2022;6:1–10. https://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/11.5257.R.20220601.1732.002.html [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tang Y., Ni X.Q. Study on the relationship between occupational stress, organizational support and turnover intention of medical social workers. J. soc. Work 2. 2023:84–95. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1672-4828.2023.02.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Abdulaziz A., Bashir M., Alfalih A.A. The impact of work-life balance and work overload on teacher's organizational commitment: do job engagement and perceived organizational support matter. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2022;27(7):9641–9663. doi: 10.1007/s10639-022-11013-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Collie R.J. A multilevel examination of teachers' occupational commitment: the roles of job resources and disruptive student behavior. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 2021;24(2):387–411. doi: 10.1007/s11218-021-09617-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ibrahim R.Z.A.R., Zalam W.Z.M., Foster B., Afrizal T., Johansyah M.D., Saputra J., Abu Bakar A., Dagang M.M., Ali S.N.M. Psychosocial work environment and teachers' psychological well-being: the moderating role of job control and social support. Int. J. Env. Res. Pub. He. 2021;18(14):7308. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18147308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Huang X., Wang G., Wang D. Effects of organizational support and occupational stress on turnover intention among kindergarten teachers: mediating effect of occupational burnout. Stud. Physiol. Behav. 2017;15(4):528–535. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lyu B., Li W.W., Xu M.Y., Chen H., Yang Y.C. All normal occupations are sunny and joyful: qualitative analysis of the ladyboys' occupational wellbeing. Psychol. Res. Behav. Ma. 2021;14:2197–2208. doi: 10.2147/PRBM.S340209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bardoel E.A., Drago R. Acceptance and strategic resilience: an application of conservation of resources theory. Group. Organ. Manage. 2021;46(4):657–691. doi: 10.1177/10596011211022488. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen J.P., Cheng H.Y., Zhao D., Zhou F.Y., Chen Y. A quantitative study on the impact of working environment on the well-being of teachers in China's private colleges. Sci. Rep-UK. 2022;12(1):3417. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-07246-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Heyder A. Teachers' beliefs about the determinants of student achievement predict job satisfaction and stress. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2019;86 doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2019.102926. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang G. The characteristics of kindergarten teachers' occupational well-being and its relationship with occupational commitment. Chin. Psychol. Dev. Educ. 2013;29(6):616–624. doi: 10.16187/j.cnki.issn1001-4918.2013.06.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lan Y.F. Unpublished PhD Dissertation, China West Normal University; China: 2016. A Study of Professional Happiness of Male Kindergarten Teachers. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Edwards J.R. In: International Review of Industrial and Organizational Psychology. Cooper C.L., Robertson I.T., editors. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 1991. Person-job fit: a conceptual integration, literature review, and methodological critique; pp. 283–357. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Xu S.A., Zhang W., You J.N. China Science Press; 2019. Career Development and Guidance. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jinseon K. Relationship between congruence of public officials and career satisfaction, career commitment the moderating effect of LMX. J. Soc. Sci. 2021;47(1):93–118. doi: 10.15820/khjss.2021.47.1.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Brandstätter V., Job V., Schulze B. Motivational incongruence and well-being at the workplace: person-job fit, job burnout, and physical symptoms. Front. Psychol. 2016;7:1153. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Qi R.Y., Li C.H., Zhou J.F. Research progress on the relationship between occupational stress and cardiovascular diseases. Shandong Medical. 2023;63(16):100–103. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1002-266X.2023.16.026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Heilman M.E. Gender stereotypes and workplace bias. Res. Organ. Behav. 2012;32:113–135. doi: 10.1016/j.riob.2012.11.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wu M.L. Chongqing University Press; 2022. Statistical Analysis of Questionnaires in Practice-Sp Operations and Applications. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wong Q.X. The role of career self-management on career decision-making effectiveness, Chin. Manage Rev. 2010;22(1):82–93. doi: 10.14120/j.cnki.cn11-5057/f.2010.01.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sun X.L., Zhou C.Y. The influence of person-job fit on preschool teachers' job burnout: mediating of job satisfaction and moderating of perceived organizational support. Xueqian Jiaoyu Yanjiu. 2020;1:42–53. doi: 10.13861/j.cnki.sece.2020.01.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Liu Z.Q., Deng C.J., Liao J.Q., Long L.R. Organizational support, perceived status and employees' innovative behavior: perspective of employment diversity. Chin. J. Manage. Sci. 2015;18(10):80–94. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1007-9807.2015.10.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Long L.R., Li X. A study on the professional commitment of primary and secondary school teachers. Chin. Educ. Res. Experiment. 2002;4:56–61. [Google Scholar]

- 57.IBM Transforming different Likert scales to a common scale. 2020. https://www.ibm.com/support/pages/transforming-different-likert-scales-common-scale Available at:

- 58.Liang M., Wang W.C., Sun Y.Y., Wang H.Y. The impact of job-related stress on township teachers' professional well-being: a moderated mediation analysis. Front. Psychol. 2022;13 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1000441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kumar P., Islam M.A., Pillai R., Sharif T. Analysing the behavioural, psychological, and demographic determinants of financial decision making of household investors. Heliyon. 2023;9(2) doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e13085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tang D.D., Wen Z.L. Statistical approaches for testing common method bias: problems and suggestions. J Psychol Sci. 2020;43:215–223. doi: 10.16719/j.cnki.1671-6981.20200130. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Niswaty R., Wirawan H., Akib H., Saggaf M.S., Daraba D. Investigating the effect of authentic leadership and employees' psychological capital on work engagement: evidence from Indonesia. Heliyon. 2021;7(5) doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e06992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Matsuo M., Tanaka G., Tokunaga A., Higashi T., Honda S., Shirabe S., Yoshida Y., Imamura A., Ishikawa I., Iwanaga R. Factors associated with kindergarten teachers' willingness to continue working. Medicine. 2021;100(35) doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000027102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wang Z.H., Wu H.L. The effect of work-family conflict on kindergarten teachers' turnover intention: the mediating role of occupational well-being. J. Chengdu Norm. Univ. 2023;39:77–83. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.2095-5642.2023.05.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Powell A., Langfoed R., Albanese P., Prentice S., Bezanson K. Who cares for carers? How discursive constructions of care work marginalized early childhood educators in Ontario's 2018 provincial election, Contemp. Iss. Early. Ch. 2020;21(2):153–164. doi: 10.1177/1463949120928433. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lee S.J., Augusto D. Crime in the new U.S. epicenter of COVID-19, Crime. Prev. Communi. Ty. 2022;24(1):57–77. doi: 10.1057/s41300-021-00136-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zhao X.Y., You X.Q., Qin W. The latent profile analysis of middle school teachers' emotional labor strategies and the relationship with vocational well-being. J. East. Chin. Norm. Univ. 2023;1:16–24. doi: 10.16382/j.cnki.1000-5560.2023.01.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kim B., Sik K.U. The relationship between occupational identity, self-efficacy, and job commitment of sports instructors: focusing on the “New Silver” generation. Korean. J. Sport. 2022;20(2):511–521. doi: 10.46669/kss.2022.20.2.046. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Fiaz S., Fahim S.M. The influence of high-quality workplace relational systems and mindfulness on employee work engagement at the time of crises. Heliyon. 2023;9 doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e15523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Van Beurden J., Van Veldhoven M., Van de Voorde K. A needs-supplies fit perspective on employee perceptions of HR practices and their relationship with employee outcomes. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2022;32(4):928–948. 10.1111/1748-8583.12449. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.