Abstract

Lung cancer, a major contributor to cancer-related fatalities worldwide, involves a complex pathogenesis. Cathepsins, lysosomal cysteine proteases, play roles in various physiological and pathological processes, including tumorigenesis. Observational studies have suggested an association between cathepsins and lung cancer. However, the causal link between the cathepsin family and lung cancer remains undetermined. This study employed Mendelian randomization analyses to investigate this causal association. The univariable Mendelian randomization analysis results indicate that elevated cathepsin H levels increase the overall risk of lung cancer, adenocarcinoma, and lung cancer among smokers. Conversely, reverse Mendelian randomization analyses suggest that squamous carcinoma may lead to increased cathepsin B levels. A multivariable analysis using nine cathepsins as covariates reveals that elevated cathepsin H levels lead to an increased overall risk of lung cancer, adenocarcinoma, and lung cancer in smokers. In conclusion, cathepsin H may serve as a marker for lung cancer, potentially inspiring directions in lung cancer diagnosis and treatment.

Subject terms: Cancer genetics

A Mendelian randomization analysis identifies a potential causal link between cathepsin H and lung cancer risk.

Introduction

Lung cancer is a major global cause of cancer-related mortality, resulting in over one million deaths annually1. Based on histology, lung cancer is classified into small-cell lung cancer (SCLC) and non-small cell lung cancer, primarily consisting of lung adenocarcinoma and lung squamous cell carcinoma2. The pathogenesis of lung cancer is a multifaceted process involving various risk factors3, with cancer cells’ ability to maintain internal homeostasis playing a crucial role4. This implies that cancer cells need to regulate material turnover, particularly protein turnover, to sustain metabolic equilibrium. Thus, a high level of proteolytic system activity is indispensable for the rapid proliferation of tumor cells5.

Cathepsins represent a group of lysosomal proteolytic enzymes that play an important role in maintaining cellular homeostasis6. In humans, the most well-known cathepsins belong to the papain superfamily of cysteine proteases7. They are integral to almost all physiological and pathophysiological cellular processes, such as protein and lipid metabolism, autophagy, antigen presentation, growth factor receptor recycling, cellular stress signaling, extracellular matrix degradation, and lysosome-mediated cell death8. Due to their involvement in these important processes, various cathepsins play critical roles in different diseases, including tumors9.

Recent studies have unveiled the roles of several cathepsins, including cathepsin B10,11, cathepsin L12, and cathepsin S13, in promoting or suppressing tumors in various cancers, such as breast, ovarian, pancreatic, and colorectal cancer14,15. However, only a limited number of observational studies and clinical trials have investigated the association between cathepsins and lung cancer. Previous studies reported elevated levels of cathepsin B and L in lung cancer patients16. Furthermore, findings from several studies confirmed the association of cathepsin B17, cathepsin F18, cathepsin H19, and cathepsin S20 with the survival of lung cancer patients. However, the roles of individual cathepsins can vary dramatically among different tumor subtypes21, and the causality between various types of cathepsins and the risk of different histological lung cancers has not been adequately studied. Therefore, further investigation is necessary to elucidate the causal association between different types of cathepsins and the risk of lung cancer subtypes.

With the advancement of genomics, there is increasing evidence revealing the role of heritability in disease etiology22. Mendelian randomization (MR), relying on genome-wide association studies (GWAS), utilizes one or more genetic variants as instrumental variables (IVs) that are strongly associated with the exposure of interest and unaffected by confounders. MR studies can infer the causal effects of exposure on an outcome23. In this context, MR analyses were conducted to investigate the causal effects of different types of cathepsins on the risk of lung cancer and its histological subtypes through both univariable and multivariable MR methods.

Results

Defining the causal link between various cathepsins and different histological subtypes of lung cancer

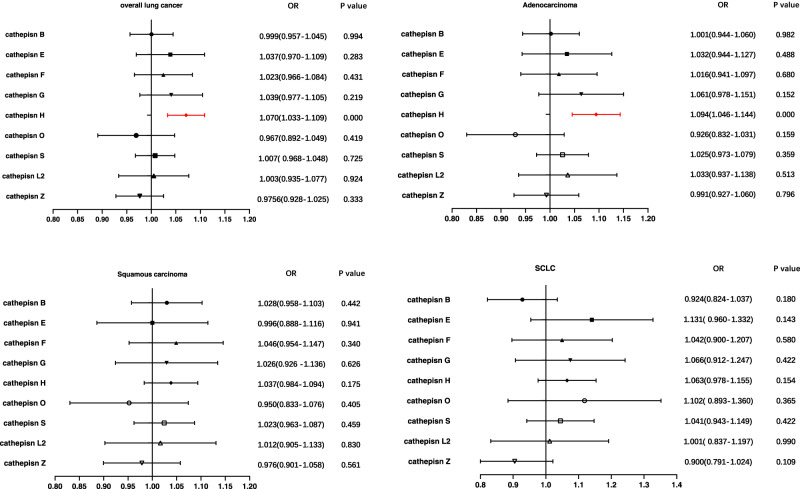

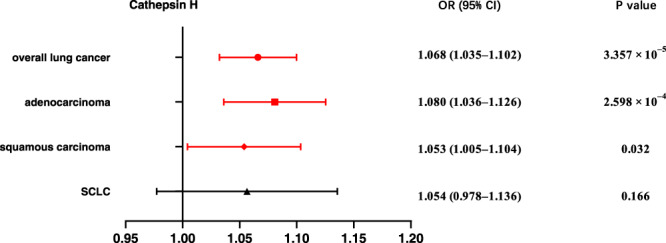

To assess the influence of various cathepsins on the risk of lung cancer subtypes, Two-Sample MR analyses involving nine cathepsins (cathepsin B, E, F, G, H, L2, O, S, and Z) and the overall risk as well as different histological subtypes of lung cancer was firstly performed. The findings of the univariable MR analysis (Fig. 1) revealed that high levels of cathepsin H increased the risk of overall lung cancer (Inverse-Variance Weighted (IVW): p = 3.357 × 10–5, OR = 1.060, 95% confidence interval (CI) = 1.035–1.102). This effect was consistently observed in lung adenocarcinoma (IVW: p = 2.598 × 10–4, OR = 1.080, 95% CI = 1.036–1.126). These consistent significant associations were further corroborated by the weighted median and MR-Egger approaches (Table 1). Additionally, weaker positive effects were observed for cathepsin H levels and the risk of squamous cell carcinomas, and cathepsin G levels and the risk of adenocarcinoma, respectively, only by the IVW method (p = 0.032, OR = 1.053, 95% CI = 1.005–1.104; p = 0.041, OR = 1.095, 95% CI = 1.004–1.195) (Table 1). Furthermore, both the MR-Egger intercept and MR-PRESSO global tests provided no evidence of directional pleiotropy for any of these causal associations in Supplementary Table 1. However, the IVW method did not reveal any causal associations between the other types of cathepsins and overall lung cancer or its major histological subtypes (Table 1).

Fig. 1. Forest plot of univariable Mendelian randomization analysis for cathepsin H and Lung cancer risk.

We conducted inverse-variance weighted analyses to evaluate the causal relationship between cathepsin H and overall lung cancer, adenocarcinoma, squamous cell carcinomas, and small-cell lung cancer. (Highlighted in red are statistically significant results, and error bars represent 95% confidence intervals).

Table 1.

Causal association of cathepsins on lung cancer and its histological subtypes estimated by univariable Mendelian randomization analysis.

| Cathepsin | SNPs | Inverse variance weighted | MR-Egger | Weighted median | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95%CI) | p_value | OR (95%CI) | p_value | OR (95%CI) | p_value | ||

| Cathepsin B | |||||||

| Overall lung cancer | 16 | 1.018 (0.977–1.060) | 0.399 | 1.025 (0.933–1.126) | 0.619 | 1.004 (0.948–1.064) | 0.884 |

| Adenocarcinoma | 16 | 1.032 (0.976–1.092) | 0.268 | 1.104 (0.970–1.256) | 0.156 | 1.043 (0.965–1.127) | 0.293 |

| Squamous carcinoma | 14 | 1.050 (0.982–1.124) | 0.155 | 1.035 (0.888–1.206) | 0.670 | 1.020 (0.933–1.114) | 0.667 |

| SCLC | 12 | 0.956 (0.821–1.114) | 0.565 | 0.781 (0.541–1.126) | 0.214 | 0.862 (0.742–1.002) | 0.053 |

| Cathepsin E | |||||||

| Overall lung cancer | 10 | 1.036 (0.974–1.103) | 0.257 | 1.059 (0.920–1.218) | 0.449 | 1.026 (0.949–1.109) | 0.518 |

| Adenocarcinoma | 10 | 1.009 (0.926–1.099) | 0.844 | 1.097 (0.902–1.335) | 0.380 | 0.978 (0.870–1.099) | 0.707 |

| Squamous carcinoma | 9 | 0.997 (0.897–1.108) | 0.950 | 1.065 (0.786–1.443) | 0.695 | 0.975 (0.848–1.121) | 0.719 |

| SCLC | 10 | 1.096 (0.936–1.282) | 0.254 | 1.316 (0.908–1.907) | 0.185 | 1.230 (0.991–1.527) | 0.060 |

| Cathepsin F | |||||||

| Overall lung cancer | 11 | 0.985 (0.939–1.033) | 0.540 | 1.051 (0.924–1.196) | 0.471 | 0.980 (0.919–1.044) | 0.523 |

| Adenocarcinoma | 11 | 1.004 (0.941–1.071) | 0.899 | 1.126 (0.910–1.394) | 0.302 | 1.035 (0.944–1.135) | 0.462 |

| Squamous carcinoma | 11 | 1.037 (0.962–1.118) | 0.337 | 1.061 (0.868–1.298) | 0.576 | 1.055 (0.956–1.164) | 0.291 |

| SCLC | 11 | 0.962 (0.854–1.084) | 0.525 | 1.152 (0.837–1.587) | 0.408 | 0.916 (0.779–1.077) | 0.291 |

| Cathepsin G | |||||||

| Overall lung cancer | 11 | 1.036 (0.973–1.104) | 0.265 | 1.039 (0.893–1.209) | 0.629 | 1.049 (0.959–1.148) | 0.293 |

| Adenocarcinoma | 11 | 1.095 (1.004–1.195) | 0.041 | 1.184 (0.986–1.421) | 0.103 | 1.069 (0.950–1.204) | 0.269 |

| Squamous carcinoma | 10 | 1.039 (0.931–1.160) | 0.495 | 1.023 (0.773–1.355) | 0.877 | 1.112 (0.957–1.292) | 0.164 |

| SCLC | 11 | 1.076 (0.874–1.325) | 0.489 | 0.987 (0.631–1.543) | 0.955 | 1.031 (0.813–1.308) | 0.799 |

| Cathepsin H | |||||||

| Overall lung cancer | 10 | 1.068 (1.035–1.102) | 3.357 × 10–5 | 1.077 (1.017–1.140) | 0.036 | 1.074 (1.038–1.111) | 4.405 × 10–5 |

| Adenocarcinoma | 10 | 1.080 (1.036–1.126) | 2.598 × 10–4 | 1.093 (1.026–1.166) | 0.026 | 1.091 (1.043–1.141) | 1.674 × 10–4 |

| Squamous carcinoma | 11 | 1.053 (1.005–1.104) | 0.032 | 1.035 (0.958–1.118) | 0.406 | 1.031 (0.977–1.088) | 0.270 |

| SCLC | 9 | 1.054 (0.978–1.136) | 0.166 | 1.020 (0.916–1.135) | 0.733 | 1.034 (0.948–1.127) | 0.448 |

| Cathepsin L2 | |||||||

| Overall lung cancer | 11 | 1.002 (0.944–1.064) | 0.942 | 1.124 (0.952–1.326) | 0.200 | 1.005 (0.924–1.093) | 0.913 |

| Adenocarcinoma | 10 | 1.024 (0.939–1.117) | 0.594 | 1.076 (0.867–1.337) | 0.524 | 1.023 (0.912–1.147) | 0.701 |

| Squamous carcinoma | 11 | 0.998 (0.878–1.136) | 0.982 | 0.985 (0.712–1.361) | 0.930 | 0.967 (0.837–1.117) | 0.651 |

| SCLC | 9 | 1.027 (0.873–1.208) | 0.750 | 1.115 (0.754–1.647) | 0.602 | 1.002 (0.814–1.235) | 0.982 |

| Cathepsin O | |||||||

| Overall lung cancer | 11 | 0.969 (0.913–1.029) | 0.306 | 0.900 (0.793–1.022) | 0.138 | 0.987 (0.913–1.067) | 0.744 |

| Adenocarcinoma | 11 | 0.954 (0.878–1.036) | 0.261 | 0.860 (0.723–1.023) | 0.122 | 0.966 (0.872–1.071) | 0.512 |

| Squamous carcinoma | 11 | 0.978 (0.889–1.076) | 0.654 | 0.981 (0.803–1.199) | 0.857 | 1.007 (0.887–1.143) | 0.916 |

| SCLC | 8 | 1.109 (0.930–1.323) | 0.250 | 1.049 (0.656–1.678) | 0.847 | 1.098 (0.863–1.397) | 0.448 |

| Cathepsin S | |||||||

| Overall lung cancer | 20 | 0.996 (0.953–1.041) | 0.875 | 0.933 (0.874–0.995) | 0.050 | 0.951 (0.906–0.999) | 0.046 |

| Adenocarcinoma | 21 | 1.026 (0.978–1.075) | 0.294 | 0.961 (0.885–1.043) | 0.352 | 0.998 (0.934–1.066) | 0.943 |

| Squamous carcinoma | 23 | 1.009 (0.956–1.065) | 0.734 | 0.927 (0.840–1.023) | 0.148 | 0.960 (0.889–1.037) | 0.301 |

| SCLC | 20 | 0.970 (0.889–1.058) | 0.492 | 0.884 (0.764–1.024) | 0.117 | 0.930 (0.827–1.046) | 0.224 |

| Cathepsin Z | |||||||

| Overall lung cancer | 20 | 0.984 (0.947–1.023) | 0.410 | 0.884 (0.764–1.024) | 0.117 | 0.930 (0.824–1.049) | 0.237 |

| Adenocarcinoma | 20 | 1.000 (0.948–1.056) | 0.989 | 0.884 (0.764–1.024) | 0.117 | 0.930 (0.824–1.049) | 0.235 |

| Squamous carcinoma | 20 | 0.988 (0.929–1.052) | 0.716 | 0.884 (0.764–1.024) | 0.117 | 0.930 (0.825–1.048) | 0.232 |

| SCLC | 20 | 0.946 (0.857–1.044) | 0.269 | 0.884 (0.764–1.024) | 0.117 | 0.923 (0.825–1.048) | 0.233 |

To explore the possibility of reverse causality, we conducted reverse MR analyses. These results in supplementary table 2 indicated a lack of reverse causality between cathepsin H and the risk of lung cancer and adenocarcinoma. However, the reverse MR analysis provided evidence that squamous carcinoma elevated cathepsin B levels (IVW: p = 0.0328, OR = 1.189, 95% CI = 1.014–1.395; and weighted median: p = 0.038, OR = 1.224, 95% CI = 1.011–1.481), and the p-values of the MR-Egger intercept and MR-PRESSO global test showing no signs of directional pleiotropy (0.826 and 0.804, respectively) (Supplementary Table 2). No evidence supported a causal association between any other histological subtypes of lung cancer and various types of cathepsins.

Moreover, we conducted multivariable MR to assess the genetic predisposition involving multiple cathepsins in relation to the risk of different histological subtypes of lung cancer. The results revealed that even after adjusting for other types of cathepsins, elevated cathepsin H levels retained a robust association with an increased risk of overall lung cancer (IVW: p = 1.460 × 10–4, OR = 1.070, 95% CI = 1.033–1.109) and adenocarcinoma risk (IVW: p = 8.854 × 10–5, OR = 1.094, 95% CI = 1.046–1.144) (Fig. 2). However, no statistically significant causal association was observed between cathepsin H and squamous cell carcinomas, or between cathepsin G and adenocarcinoma, after adjusting for other types of cathepsins, the same as the other types of cathepsins and overall lung cancer or its different histological subtypes. Moreover, horizontal pleiotropy was not indicated by the MR-Egger intercept analysis in Supplementary Table 3.

Fig. 2. Forest plot of multivariable Mendelian randomization analysis for various cathepsins and lung cancer risk.

We employed the inverse-variance weighted method to investigate the causal associations between nine cathepsins (cathepsin B, E, F, G, H, L2, O, S, and Z) and overall lung cancer, adenocarcinoma, squamous cell carcinomas, and small-cell lung cancer (SCLC). (Highlighted in red are statistically significant results, and error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals).

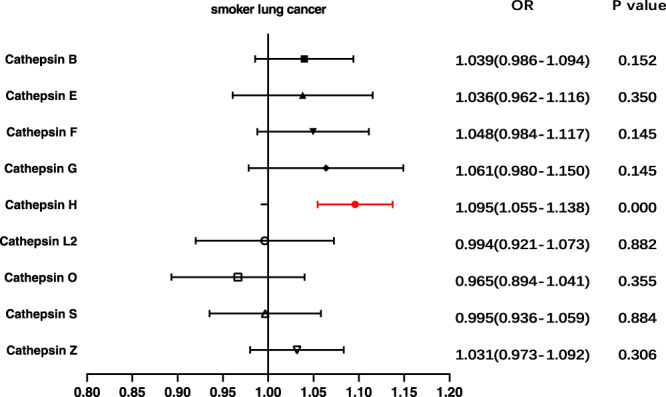

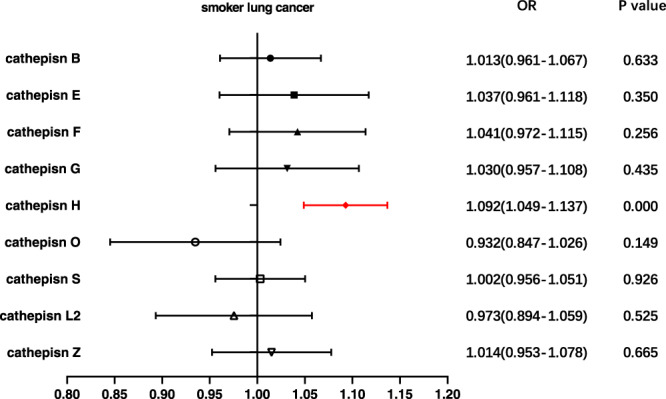

Subgroup MR analyses stratified by smoking behavior

Given the substantial number of lung cancer patients with a history of smoking, and the influence of smoking behavior on lung cancer development, we conducted an in-depth analysis of the causal association between various cathepsins and lung cancer risk stratified by smoking behavior (ever and never smoking). Univariable MR analysis results revealed that elevated cathepsin H levels significantly increased the risk of lung cancer among ever smokers (p = 2.429 × 10–6, OR = 1.095, 95% CI = 1.055–1.138) (Fig. 3). Similarly, no associations between the other types of cathepsins and lung cancer in individuals with a smoking history were found (Supplementary Data 1). For the never-smoker subgroup, none of the assessed associations were significant (Supplementary Data 1). In all the aforementioned analyses, no evidence of horizontal pleiotropy was detected through the MR-PRESSO global test and MR-Egger intercept (p > 0.05) (Supplementary Data 1). Furthermore, reverse MR analysis was performed, the results of which showed no reverse causality between cathepsin H levels and lung cancer risk among individuals with a history of smoking (Supplementary Data 1). Moreover, multivariable MR analysis confirmed a significant direct effect of cathepsin H on lung cancer risk among individuals with a smoking history (p = 1.777 × 10–5, OR = 1.092, 95% CI = 1.049–1.137) (Fig. 4), with the results of the MR-Egger intercept analysis again indicating no existence of directional horizontal pleiotropy (Supplementary Data 1).

Fig. 3. Forest plot of univariable Mendelian randomization analysis for nine cathepsins and lung cancer risk among smokers.

We utilized the inverse-variance weighted method to analyze the causal associations between different cathepsins and lung cancer in individuals with a history of smoking. (Highlighted in red are statistically significant results, and error bars represent 95% confidence intervals).

Fig. 4. Forest plot of multivariable Mendelian randomization inverse-variance weighted analysis for nine cathepsins and lung cancer risk among smokers.

The inverse-variance weighted method was employed to investigate the causal relationships between nine cathepsins (cathepsin B, E, F, G, H, L2, O, S, and Z) and lung cancer in individuals with a history of smoking. (Highlighted in red are statistically significant results, and error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals).

Determining the potential mediation effects

The above-mentioned results have revealed that cathepsin H increases the risk of lung cancer among individuals with smoking behavior. Given that smoking is a well-accepted risk factor for lung cancer24, we analyzed the possibility that cathepsin H acted as a mediator between smoking and lung cancer. Two-step MR25 was used to explore the mediation effects of cathepsin H. The results showed no significant causal effects between smoking initiation and cathepsin H (IVW OR = 0.919, 95% CI = 0.720–1.172, p = 0.494), and vice versa (IVW OR = 1.002, 95% CI = 0.992–1.011, p = 0.752). Subsequently, Bayesian colocalization analysis was performed to putatively identify whether cathepsin H drove the risk of lung cancer among ever-smokers by sharing pathway effects with smoking. CTSH, the gene encoding cathepsin H, is located in chromosomal region 15q25.1, and cathepsin H-related variants also reside in this region. The results of the colocalization analysis indicated no shared variants between cathepsin H and smoking for the CTSH locus (posterior probability = 0.004). Furthermore, we focused on smoking-related variants and performed colocalization analysis for each candidate variant using a 10,000 kb window around the target single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs). The findings revealed that all posterior probabilities for these two traits were less than 0.5. In summary, we found no valid evidence supporting a shared causal variant between the two traits. Consequently, we concluded that a high level of cathepsin H was a hazardous risk factor for developing lung cancer, rather than a mediator of the causal relationship between smoking and lung cancer.

Discussion

The development and progression of malignant tumors involve a highly complex process in which proteolytic events play crucial roles26. Among the important members associated with these events, cathepsins have attracted considerable interest. In this study, we systematically analyzed the causal link between nine different cathepsins and the risk of various histological subtypes of lung cancer using genetic instruments. To our knowledge, this is the large-scale genetic consortia-based MR analysis to establish causality between cathepsins and lung cancer. By integrating findings from univariable analysis, multivariable analysis, mediation analysis, and colocalization analysis, we concluded that cathepsin H is a significant risk factor for lung cancer, especially in individuals with a history of smoking, and no reverse causality for cathepsin H was found.

The analyses conducted in this study demonstrated that cathepsin H increased the risk of overall lung cancer, adenocarcinoma, and lung cancer among smokers. The results obtained from the IVW methods were consistent with other complementary methods and did not suggest pleiotropy or reverse causality. In contrast, we found no significant association between cathepsin H and lung cancer in individuals without a history of smoking in this study. Given that the Transdisciplinary Research in Cancer of the Lung (TRICL) GWAS data for lung cancer stratified by smoking behavior included only 9859 never smokers out of 50,036, it remains unclear whether this null effect reflects the ground truth or results from inadequate statistical power. Further research is warranted.

The conclusions provided herein clarify the partial association between cathepsin H and lung cancer reported in previous observational research and clinical studies19. However, observational research has indicated that cathepsin H is most significantly associated with squamous cell carcinomas, an association not supported by the current MR analyses. Our results demonstrated only a weak causal link between cathepsin H levels and the risk of squamous cell carcinomas in univariable analysis using the IVW method. When other types of cathepsins were adjusted in the multivariable analysis, no statistical difference was found, possibly due to functional compensation by other family members. Multivariable MR analysis might help mitigate these potential biases that can affect conventional observational studies. Therefore, except for overall lung cancer, adenocarcinoma, and lung cancer among smokers, the current evidence is insufficient to establish any causal link between cathepsin H and squamous cell carcinomas or SCLC.

Findings from previous studies24,27 have demonstrated that smoking behavior has a noteworthy impact on the development of lung cancer. This may introduce notable biases into the relationship between cathepsin H and the risk of lung cancer. In addition to univariable MR, both mediation MR analysis and colocalization analysis were carried out to assess potential biases introduced by smoking behavior. The findings indicated that cathepsin H has a causal effect on the risk of lung cancer, rather than serving as a mediator in the pathway from smoking to lung cancer.

Due to its unique endopeptidase activity, cathepsin H, a lysosomal cysteine protease, plays a prominent role in physiological and pathological processes28. Previous studies have explored possible mechanisms related to cathepsin H and tumors, suggesting that the effects of cathepsin H on tumors may be linked to its unique role in the establishment and development of tumor vasculature29. Additionally, cathepsin H participates in the degradation of the extracellular matrix30 and the activation of the extracellular signal-regulated kinase31, promoting tumor cell migration and invasion. A distinguishing feature of human lungs is the abundance of cathepsin H in the alveolar space32, contributing to the generation of lung surfactant involved in maintaining lung functions33. Therefore, the mechanism of cathepsin H in relation to lung cancer becomes more complex, and further research is needed to elucidate the role of cathepsin H in lung cancer.

Furthermore, the results of reverse MR analyses indicated that squamous cell carcinomas increase cathepsin B expression, explaining the high levels of cathepsin B detected in lung cancer patients in previous clinical studies and elucidating the unique role of squamous cell carcinomas16,34. Squamous cell carcinomas might regulate cathepsin B expression through transcription factors Ets1, Sp1, and Sp335, ultimately leading to immune resistance and tumor progression.

With increasing health awareness, tumor screening is becoming increasingly popular. Serum marker detection offers considerable advantages in tumor screening in terms of convenience and speed of detection. This study utilized MR analysis, relying on genetic variants, to explore the causal effect of various cathepsins on different subtypes of lung cancer. The integration of multivariate and reverse MR analysis minimized confounding and reverse causation bias, while mediation analysis and colocalization analysis ruled out mediation effects. These analyses yielded robust results and strengthened the final causal inference. This collective strategy can be utilized to search for and investigate effective tumor markers. However, it is important to note that the individuals included in this study are all of European descent, limiting the generalizability of the conclusions to other racial groups.

In conclusion, the primary genetic evidence from this study reveals that high levels of cathepsin H increase the risk of lung cancer, particularly adenocarcinoma and lung cancer among smokers. Additionally, squamous cell carcinoma may play an important role in regulating cathepsin B expression. This insight may aid in identifying biochemical markers for the prediction, screening, early diagnosis, and prognosis of lung cancer. Moreover, protease inhibitors targeting the specialized cathepsins associated with each histological subtype of lung cancer may offer a potential direction for effective lung cancer treatment.

Methods

Instrumental variables

Genetic instruments for assessing the levels of various cathepsins (µg/L) were obtained from the INTERVAL study, which included 3301 European individuals36. All donors were asked to complete the trial consent, and the INTERVAL study was approved by The National Research Ethics Service (11/EE/0538). Summary data can be accessed at https://gwas.mrcieu.ac.uk. Selection of cathepsin-related IVs for MR analyses followed specific criteria: (a) an r2 measure of LD among instruments <0.001 within a 10,000 kb window; (b) p-values below the genome-wide significant level identified in the corresponding study (5 × 10−6; this value was established in line with the limitation of the sample size). The meta-analysis of GWAS of smoking included 1,232,091 European individuals37, with the cutoff values of independently associated SNPs established as p < 5 × 10−8 and r2 < 0.001. The included SNPs of exposure data are detailed in Supplementary Data 2.

Genetic association of SNPs with lung cancer risk

Summary statistics for lung cancer risk, including log odds ratio (OR) estimates and standard errors for instrumental SNPs, were obtained from the TRICL https://www.ebi.ac.uk/gwas. These data resulted from an aggregated GWAS analysis of lung cancer, including 29,836 cases and 55,586 controls38. The study also provided associations between instrumental SNPs and different histological subtypes of lung cancer, including 11,273 adenocarcinomas, 7426 squamous cell carcinomas, and 2664 SCLC cases. Subgroup analyses were conducted based on smoking status, including smokers (23,223 cases and 16,964 controls) and never smokers (2355 cases and 7504 controls), limited to individuals of European descent. All participants provided informed written consent, and all studies were reviewed and approved by institutional ethics review committees at the involved institutions.

Statistics and reproducibility

MR utilizes genetic variants as IVs to ascertain whether an exposure causally impacts an outcome. A valid IV must meet three core criteria: First, it should be highly correlated with the exposure. Second, a SNP must not be pertinent to traits that would confound the relation between the exposure and the outcome. Lastly, certain variants cannot be associated with the outcome via other paths rather than the exposure. A SNP is considered to have horizontal pleiotropy when the last two assumptions are violated.

In this MR study, the IVW was employed as the primary method to estimate an overall effect size39. Briefly, the influence of each variant on the risk of the disease under investigation was weighted by its effect on the exposure using the Wald ratio method in IVW. Subsequently, these individual MR estimates were amalgamated to attain an overall summary value employing a random-effect inverse variance meta-analysis. Complementary methods, including MR-Egger40 and weighted median41, were used to validate the robustness of the MR results. Briefly, MR-Egger regression40 is a weighted linear regression of the SNP-outcome association on the SNP-exposure associations, and the estimator of the weighted median method41 is a median in which individual MR estimates are weighted proportionally to their precisions, as its name implied. MR analyses (including IVW, MR-Egger, and weighted median) were executed using the R TwoSampleMR package42.

Various sensitivity analyses and statistical tests were conducted to evaluate the validity of assumptions. Cochran’s Q test was used to estimate the heterogeneity of the SNPs. A p-value > 0.05 indicated a lack of heterogeneity. The random effects model was applied when significant heterogeneity among the SNPs existed; otherwise, a fixed effects model was used43. MR-PRESSO global test and MR-Egger intercept were employed to identify outliers and horizontal pleiotropic effects44. The intercept of MR-Egger represents the average pleiotropic effect (intercept p value < 0.05) and the slope could produce a robust pleiotropy MR estimate. The MR-PRESSO outlier test was used to correct for horizontal pleiotropy by removing or down-weighting the outliers when the horizontal pleiotropy was significant (p-value of MR-PRESSO global test < 0.05). Additionally, the MR-PRESSO distortion test was used to identify significant distortion in causal estimates before and after removing outliers. MR-PRESSO global, outlier, and distortion tests were performed using the R MR-PRESSO package44. Leave-one-out analysis was also conducted to identify SNPs with potential extreme influence on estimates and further evaluate the reliability of the results.

Multivariable MR, an extension of standard univariable MR, was used to consider multiple cathepsins when analyzing their causal effects on different lung cancer subtypes and estimating the direct causal effects of each exposure in a single analysis, employing the “MendelianRandomization” package43. Reverse MR analyses, treating lung cancer as the exposure and cathepsins as the outcomes, were performed to evaluate reverse causality and justify the existence of bidirectional causality. In these reverse MR analyses, the same GWAS datasets as the above mentioned were used, the IVs for lung cancer were selected from TRICL, and the abundance levels of cathepsins from the INTERVAL study were used as outcomes. Two-step MR25, a sequence of two MR analyses connected by a shared variable, was employed in mediation analysis to assess whether one trait acts as a mediator, such as whether the cathepsins family lies in between the path from smoking behavior to lung cancer.

Colocalization analysis was conducted using the Coloc package45 to test whether common genetic variants within a given region were shared between two traits. In brief, Bayesian approach calculated a posterior probability of two traits sharing common genetic variants within the same genomic region. All statistical analyses were performed using R software version 4.1.1.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Acknowledgements

We thank Sagesci (www.sagesci.cn) for its linguistic assistance during the preparation of this manuscript. This work was supported by Jilin Provincial Science and Technology Development Plan Project (20220204115YY); Jilin Provincial Science and Technology Development Plan Project, Natural Science Foundation of Jilin Province (YDZJ202201ZYTS121 and YDZJ202301ZYTS007); and Jilin Provincial Science and Technology Research projects of Education Office (JJKH20231215KJ).

Author contributions

S.T. and W.L. conceived and designed the experiment; J.L. ran the analysis and verified the underlying data; J.L. and S.T. wrote the original manuscript. M.T., W.L. and X.G. involved in data interpretation. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Biology thanks Yu Jiang and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: George Inglis. A peer review file is available.

Data availability

The raw data analyzed during the current study were available in public databases https://gwas.mrcieu.ac.uk. and https://www.ebi.ac.uk/gwas. The detailed accession number of involved datasets and summary data (including specific IVs) of the main results, along with source data underlying Figs. 1–4, are available in Supplementary Data 3.

Code availability

All packages for data analysis used in this study were open source in R software (version 4.1.1; R Development Core Team).

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Suyan Tian, Email: wmxt@jlu.edu.cn.

Wei Liu, Email: l_w01@jlu.edu.cn.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s42003-023-05408-7.

References

- 1.Miller KD, et al. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2022. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2022;72:409–436. doi: 10.3322/caac.21731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reck M, Heigener DF, Mok T, Soria JC, Rabe KF. Management of non-small-cell lung cancer: recent developments. Lancet. 2013;382:709–719. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61502-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen S, Wu S. Identifying lung cancer risk factors in the elderly using deep neural networks: quantitative analysis of web-based survey data. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020;22:e17695. doi: 10.2196/17695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van Neerven SM, Vermeulen L. Cell competition in development, homeostasis and cancer. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2023;24:221–236. doi: 10.1038/s41580-022-00538-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moschovi M, et al. Drugs acting on homeostasis: challenging cancer cell adaptation. Expert Rev. Anticancer Ther. 2015;15:1405–1417. doi: 10.1586/14737140.2015.1095095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reiser J, Adair B, Reinheckel T. Specialized roles for cysteine cathepsins in health and disease. J. Clin. Investig. 2010;120:3421–3431. doi: 10.1172/JCI42918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fonović M, Turk B. Cysteine cathepsins and extracellular matrix degradation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2014;1840:2560–2570. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2014.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Conus S, Simon HU. Cathepsins: key modulators of cell death and inflammatory responses. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2008;76:1374–1382. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2008.07.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yadati, T., Houben, T., Bitorina, A. & Shiri-Sverdlov, R. The ins and outs of cathepsins: physiological function and role in disease management. Cells9, 10.3390/cells9071679 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Harbeck N, et al. Prognostic impact of proteolytic factors (urokinase-type plasminogen activator, plasminogen activator inhibitor 1, and cathepsins B, D, and L) in primary breast cancer reflects effects of adjuvant systemic therapy. Clin. Cancer Res. 2001;7:2757–2764. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scorilas A, et al. Determination of cathepsin B expression may offer additional prognostic information for ovarian cancer patients. Biol. Chem. 2002;383:1297–1303. doi: 10.1515/BC.2002.146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Niedergethmann M, et al. Prognostic impact of cysteine proteases cathepsin B and cathepsin L in pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Pancreas. 2004;29:204–211. doi: 10.1097/00006676-200410000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gormley JA, et al. The role of Cathepsin S as a marker of prognosis and predictor of chemotherapy benefit in adjuvant CRC: a pilot study. Br. J. Cancer. 2011;105:1487–1494. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2011.408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gocheva V, et al. IL-4 induces cathepsin protease activity in tumor-associated macrophages to promote cancer growth and invasion. Genes Dev. 2010;24:241–255. doi: 10.1101/gad.1874010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mijanović O, et al. Cathepsin B: a sellsword of cancer progression. Cancer Lett. 2019;449:207–214. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2019.02.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen Q, et al. Detection of cathepsin B, cathepsin L, cystatin C, urokinase plasminogen activator and urokinase plasminogen activator receptor in the sera of lung cancer patients. Oncol. Lett. 2011;2:693–699. doi: 10.3892/ol.2011.302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kayser K, et al. Expression, proliferation activity and clinical significance of cathepsin B and cathepsin L in operated lung cancer. Anticancer Res. 2003;23:2767–2772. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Song L, et al. Expression signature, prognosis value and immune characteristics of cathepsin F in non-small cell lung cancer identified by bioinformatics assessment. BMC Pulm. Med. 2021;21:420. doi: 10.1186/s12890-021-01796-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schweiger A, et al. Cysteine proteinase cathepsin H in tumours and sera of lung cancer patients: relation to prognosis and cigarette smoking. Br. J. Cancer. 2000;82:782–788. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.1999.0999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kos J, et al. Cathepsin S in tumours, regional lymph nodes and sera of patients with lung cancer: relation to prognosis. Br. J. Cancer. 2001;85:1193–1200. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2001.2057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Olson OC, Joyce JA. Cysteine cathepsin proteases: regulators of cancer progression and therapeutic response. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2015;15:712–729. doi: 10.1038/nrc4027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brennan P, Hainaut P, Boffetta P. Genetics of lung-cancer susceptibility. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:399–408. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70126-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Burgess S, et al. Guidelines for performing Mendelian randomization investigations. Wellcome Open Res. 2019;4:186. doi: 10.12688/wellcomeopenres.15555.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ding J, Tu Z, Chen H, Liu Z. Identifying modifiable risk factors of lung cancer: indications from Mendelian randomization. PLoS One. 2021;16:e0258498. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0258498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Relton CL, Davey Smith G. Two-step epigenetic Mendelian randomization: a strategy for establishing the causal role of epigenetic processes in pathways to disease. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2012;41:161–176. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyr233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mason SD, Joyce JA. Proteolytic networks in cancer. Trends Cell Biol. 2011;21:228–237. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2010.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Larsson SC, Burgess S. Appraising the causal role of smoking in multiple diseases: a systematic review and meta-analysis of Mendelian randomization studies. EBioMedicine. 2022;82:104154. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2022.104154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang Y, et al. Cathepsin H: molecular characteristics and clues to function and mechanism. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2023;212:115585. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2023.115585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gocheva V, Chen X, Peters C, Reinheckel T, Joyce JA. Deletion of cathepsin H perturbs angiogenic switching, vascularization and growth of tumors in a mouse model of pancreatic islet cell cancer. Biol. Chem. 2010;391:937–945. doi: 10.1515/BC.2010.080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rojnik M, et al. Cathepsin H indirectly regulates morphogenetic protein-4 (BMP-4) in various human cell lines. Radiol. Oncol. 2011;45:259–266. doi: 10.2478/v10019-011-0034-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fröhlich E, Möhrle M, Klessen C. Cathepsins in basal cell carcinomas: activity, immunoreactivity and mRNA staining of cathepsins B, D, H and L. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 2004;295:411–421. doi: 10.1007/s00403-003-0449-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brasch F, et al. Involvement of cathepsin H in the processing of the hydrophobic surfactant-associated protein C in type II pneumocytes. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2002;26:659–670. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.26.6.4744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Woischnik M, et al. Cathepsin H and napsin A are active in the alveoli and increased in alveolar proteinosis. Eur. Respir. J. 2008;31:1197–1204. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00081207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gong F, et al. Cathepsin B as a potential prognostic and therapeutic marker for human lung squamous cell carcinoma. Mol. Cancer. 2013;12:125. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-12-125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sloane BF, et al. Cathepsin B and tumor proteolysis: contribution of the tumor microenvironment. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2005;15:149–157. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2004.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sun BB, et al. Genomic atlas of the human plasma proteome. Nature. 2018;558:73–79. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0175-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu M, et al. Association studies of up to 1.2 million individuals yield new insights into the genetic etiology of tobacco and alcohol use. Nat. Genet. 2019;51:237–244. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0307-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McKay JD, et al. Large-scale association analysis identifies new lung cancer susceptibility loci and heterogeneity in genetic susceptibility across histological subtypes. Nat. Genet. 2017;49:1126–1132. doi: 10.1038/ng.3892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Burgess S, Butterworth A, Thompson SG. Mendelian randomization analysis with multiple genetic variants using summarized data. Genet. Epidemiol. 2013;37:658–665. doi: 10.1002/gepi.21758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bowden J, Davey Smith G, Burgess S. Mendelian randomization with invalid instruments: effect estimation and bias detection through Egger regression. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2015;44:512–525. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyv080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bowden J, Davey Smith G, Haycock PC, Burgess S. Consistent estimation in Mendelian Randomization with some invalid instruments using a weighted median estimator. Genet. Epidemiol. 2016;40:304–314. doi: 10.1002/gepi.21965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hemani, G. et al. The MR-Base platform supports systematic causal inference across the human phenome. eLife7, 10.7554/eLife.34408 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 43.Yavorska OO, Burgess S. MendelianRandomization: an R package for performing Mendelian randomization analyses using summarized data. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2017;46:1734–1739. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyx034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Verbanck M, Chen CY, Neale B, Do R. Detection of widespread horizontal pleiotropy in causal relationships inferred from Mendelian randomization between complex traits and diseases. Nat. Genet. 2018;50:693–698. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0099-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Giambartolomei C, et al. Bayesian test for colocalisation between pairs of genetic association studies using summary statistics. PLoS Genet. 2014;10:e1004383. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Data Availability Statement

The raw data analyzed during the current study were available in public databases https://gwas.mrcieu.ac.uk. and https://www.ebi.ac.uk/gwas. The detailed accession number of involved datasets and summary data (including specific IVs) of the main results, along with source data underlying Figs. 1–4, are available in Supplementary Data 3.

All packages for data analysis used in this study were open source in R software (version 4.1.1; R Development Core Team).