Abstract

New antibiotic regimens are needed for the treatment of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. Mycobacterium tuberculosis has a thick peptidoglycan layer, and the penicillin-binding proteins involved in its biosynthesis are inhibited by clinically relevant concentrations of β-lactam antibiotics. β-Lactamase production appears to be the major mechanism by which M. tuberculosis expresses β-lactam resistance. β-Lactamases from the broth supernatant of 3- to 4-week-old cultures of M. tuberculosis H37Ra were partially purified by sequential gel filtration chromatography and chromatofocusing. Three peaks of β-lactamase activity with pI values of 5.1, 4.9, and 4.5, respectively, and which accounted for 10, 78, and 12% of the total postchromatofocusing β-lactamase activity, respectively, were identified. The β-lactamases with pI values of 5.1 and 4.9 were kinetically indistinguishable and exhibited predominant penicillinase activity. In contrast, the β-lactamase with a pI value of 4.5 showed relatively greater cephalosporinase activity. An open reading frame in cosmid Y49 of the DNA library of M. tuberculosis H37Rv with homology to known class A β-lactamases was amplified from chromosomal DNA of M. tuberculosis H37Ra by PCR and was overexpressed in Escherichia coli. The recombinant enzyme was kinetically similar to the pI 5.1 and 4.9 enzymes purified directly from M. tuberculosis. It exhibited predominant penicillinase activity and was especially active against azlocillin. It was inhibited by clavulanic acid and m-aminophenylboronic acid but not by EDTA. We conclude that the major β-lactamase of M. tuberculosis is a class A β-lactamase with predominant penicillinase activity. A second, minor β-lactamase with relatively greater cephalosporinase activity is also present.

Tuberculosis causes 3 million deaths annually, more than any other single infectious agent (2, 19, 35). Multidrug resistance is a growing clinical problem, with strains of Mycobacterium tuberculosis exhibiting resistance to 11 or more antimicrobial agents having been described (25). Although it was shown in the 1940s that under certain culture conditions penicillin inhibits the growth of M. tuberculosis (9, 10, 18, 31), the availability of other effective antimicrobial agents limited efforts to determine whether tuberculosis might respond to treatment with β-lactams. However, the recent rise in infections caused by multidrug-resistant strains has made it necessary to identify alternative treatment regimens, including the determination of whether some older classes of antibiotics such as the β-lactams might be effective in the clinical setting.

The cell wall structure of M. tuberculosis contains a thick peptidoglycan layer. Cycloserine, a second-line drug in the treatment of tuberculosis, is a d-alanine analog that interferes with peptidoglycan synthesis (37). Recently, it has been shown that M. tuberculosis makes at least four penicillin-binding proteins (PBPs) that bind ampicillin and other β-lactams at clinically relevant antibiotic concentrations (3). The affinities of these agents for their PBP targets are of the magnitude seen for β-lactams that can be effectively used for the treatment of infections caused by other microbes. Also, the outer cellular structures of tubercle bacilli do not represent a major permeability barrier for β-lactams (3, 22). Therefore, the production of β-lactamase by M. tuberculosis appears to be its major mechanism of resistance to β-lactams.

Most and possibly all isolates of M. tuberculosis produce β-lactamase (12, 13, 15, 42); however, data regarding its nature are limited. Opinions differ as to whether it is secreted, cytoplasmic, or bound to the cell membrane and as to whether its production is inducible or constitutive (10, 14, 15, 32, 42). Zhang et al. (42) have reported that isoelectric focusing of Triton X-100 extracts of acetone-precipitated cell pellets of strains of M. tuberculosis reveals two bands exhibiting β-lactamase activity with pI values of 4.9 and 5.1.

Most of the information on the kinetic properties of M. tuberculosis β-lactamase comes from studies with relatively impure preparations of enzyme or has been inferred indirectly via the results of susceptibility tests involving β-lactams and β-lactam–β-lactamase inhibitor combinations. However, greater penicillinase activity than cephalosporinase activity is consistently reported (15, 20, 22, 42). M. tuberculosis β-lactamase is inhibited competitively by antistaphylococcal penicillins (13–15, 21, 22, 32) and by conventional β-lactamase inhibitors including clavulanic acid, sulbactam, and tazobactam (5, 8, 33, 38, 41, 42). β-Lactamase inhibitors improve the activities of some penicillins against M. tuberculosis in vitro (5, 8, 14, 33) and in vivo (13). In addition, some cephalosporins including ceforanide and cephapirin as well as carbapenems such as imipenem exhibit potent in vitro activities (23, 30, 36).

Because a better understanding of the mechanisms by which M. tuberculosis expresses resistance to β-lactams might ultimately lead to strategies in which these agents could be used in the treatment of tuberculosis, we have worked to characterize its β-lactamase(s). In this report, we describe the isolation of three enzymes with distinct pI values directly from M. tuberculosis and the recombinant expression and kinetic characterization of the major enzyme.

(Results of this study were presented in part at the 36th Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, New Orleans, La., 15 to 18 September 1996, and at the 32nd U.S.-Japan Conference of Tuberculosis/Leprosy, Cleveland, Ohio, 21 to 23 July 1997.)

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, media, and reagents.

Strain H37Ra (ATCC 25177) is an attenuated laboratory strain of M. tuberculosis. Escherichia coli DH5α was used in routine E. coli transformation experiments, and E. coli Top10 was used as the host for recombinant protein expression. Middlebrook 7H9 broth media and oleic acid-albumin-dextrose-catalase (OADC) were purchased from Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich. G-75 Sephadex (Pharmacia-LKB Biotechnology, Broma, Sweden) was used to construct the gel filtration column, and DEAE-cellulose (Pharmacia-LKB) was used for anion-exchange chromatography. Standard powders of nitrocefin (BBL Microbiology Systems, Cockeysville, Md.), phenoxymethylpenicillin and cephaloridine (Sigma Chemical Company, St. Louis, Mo.), cephapirin (Bristol Laboratories, Syracuse, N.Y.), cefazolin, cephalothin, cefamandole, and benzylpenicillin (Eli Lilly & Company, Indianapolis, Ind.), azlocillin (Miles Inc., West Haven, Conn.), amoxicillin and clavulanic acid (SmithKline Beecham Pharmaceuticals, Philadelphia, Pa.), and sulbactam (Pfizer Inc., New York, N.Y.) were used to prepare antibiotic solutions for kinetic studies.

Determination of β-lactamase activity.

β-Lactamase activity was assayed spectrophotometrically with nitrocefin (100 μM) in 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer (pH 6.0) as the substrate at 37°C (26). All determinations were carried out in duplicate. One unit of β-lactamase activity is defined as the amount required to hydrolyze 1 nmol of nitrocefin per min. To calculate the amount of secreted and cell-associated β-lactamase, cells from a 3-week-old culture of H37Ra in Middlebrook 7H9 media supplemented with OADC and 0.05% Tween 80 (BBL Microbiology Systems) were pelleted by centrifugation. The cell pellet was resuspended in 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer (pH 6.0) and lysed with a Bead Beater (Biospec Products, Bartlesville, Okla.) for 2 min. The supernatant from the broth culture and the cell lysate thus obtained were assayed for β-lactamase activity as described above to determine the amounts of extracellular and cell-associated β-lactamase, respectively.

Purification of β-lactamase directly from M. tuberculosis H37Ra.

M. tuberculosis H37Ra was inoculated into Middlebrook 7H9 broth media containing OADC and 0.05% Tween 80 was added to facilitate its growth as dispersed cells rather than clumps of cells (18, 34). A 4-week-old culture was harvested and the supernatant was precipitated with ammonium sulfate. The precipitated pellet obtained by increasing the ammonium sulfate concentration from 50 to 62.5% was resuspended in 0.1 M sodium citrate buffer (pH 5.0) and dialyzed overnight in the same buffer.

(i) Gel filtration chromatography.

The crude enzyme preparation thus obtained was concentrated to 20 ml and was loaded onto a G-75 column (3 by 90 cm) equilibrated with 0.1 M sodium citrate buffer (pH 5.0). Elution was continued with the same buffer until the β-lactamase activity was recovered.

(ii) Chromatofocusing chromatography.

The β-lactamase activity from gel filtration chromatography was exchanged with 25 mM bis-Tris buffer (pH 6.3) and was loaded onto a Mono P column (HR 5/20 fast-performance liquid chromatography system; Pharmacia-LKB), and the proteins were eluted with polybuffer (pH 4.0) in a linear gradient manner.

(iii) Anion-exchange chromatography.

As an alternative to chromatofocusing, in some experiments anion-exchange chromatography was performed with a column (3 by 20 cm) and DEAE-cellulose. Fractions from the gel filtration column exhibiting β-lactamase activity were pooled, concentrated, and exchanged with 20 mM bis-Tris buffer (pH 6.0). After loading onto and washing of the anion-exchange column with the same buffer, the β-lactamase was eluted with 20 mM bis-Tris (pH 6.0) containing a linear gradient from 0 to 200 mM NaCl.

Isoelectric focusing of M. tuberculosis β-lactamase.

Each peak fraction of β-lactamase activity collected independently from the chromatofocusing column was subjected to isoelectric focusing on a Multiphor electrophoresis system (Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, N.J.). Isoelectric focusing was performed with commercially available ampholyte polyacrylamide gels (pH range, 4.0 to 6.5; Pharmacia-LKB Biotechnology). Electrophoresis was performed at 10°C by using preset values of 1,400 V, 25 mA, and 25 W. After 3 h, the gel was removed and the bands corresponding to β-lactamase activity were visualized by overlaying the gel with Whatman paper impregnated with nitrocefin.

The isoelectric point of each peak was estimated with the help of TEM and Bacteroides fragilis β-lactamases, which have low pI values, for comparison. Three TEM β-lactamases (TEM-1, pI 5.4; TEM-3, pI 6.3; TEM-12, pI 5.2) and B. fragilis β-lactamase (pI 4.3) were run in parallel with each peak on the isoelectric focusing gel. After focusing and nitrocefin staining, the pI values were estimated graphically by using the known β-lactamases as references.

Expression, renaturation, and purification of Y49 β-lactamase.

Two oligonucleotide primers Y49F (GATCTCGAGAATGCGCAACAGAGGATTCGGTCGT) and Y49R (GATGAATTCCTATGCAAGCACACCGGCAAC) (where underscores indicate the restriction sites) were constructed on the basis of the DNA sequence of a β-lactamase gene in cosmid Y49 of a library of chromosomal DNA of M. tuberculosis H37Rv that has been sequenced by the Sanger Centre, Cambridge, United Kingdom (27). On the basis of our finding that the major β-lactamase is an exoenzyme, the Y49F primer was designed on the basis of the codons slightly inside of the deduced N terminus of the Y49 open reading frame so that the N terminus of the recombinant protein would align with a plausible signal peptide cleavage site. An XhoI site was added in the Y49F primer, and an EcoRI site was added in the Y49R primer. These primers were used to amplify the Y49 β-lactamase gene from the chromosomal DNA of M. tuberculosis H37Ra, producing a 900-bp product which was digested with XhoI and EcoRI and cloned into the E. coli expression vector ptrchisB vector (Invitrogen). The authenticity of the amplified PCR product has been verified by sequencing the insert in the ptrchisB vector. The construct was transformed into E. coli Top 10, and the expression of the recombinant six-histidine tag–Y49 β-lactamase fusion protein was induced with isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside. Sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) of the cell lysate indicated that most of the recombinant protein was found in a pellet as insoluble inclusion bodies. Thus, a protocol was developed to renature the protein on the nickel affinity column. The inclusion body pellet was dissolved in 8 M guanidine hydrochloride–500 mM NaCl–25 mM Tris (pH 8.0) containing 25 mM β-mercaptoethanol and loaded onto a preequilibrated nickel column (Invitrogen). The column was washed twice with the same buffer and twice with a buffer at pH 6.0. Then, a renaturation buffer containing 25 mM Tris–500 mM NaCl (pH 8.3) without β-mercaptoethanol was used to wash the column twice. The renatured recombinant Y49 was eluted with 5 ml of different concentrations (50, 150, 300, and 500 mM) of imidazole containing 500 mM NaCl and 25 mM Tris (pH 6.0), and 1-ml fractions were collected. Each fraction was assayed for β-lactamase activity. Most of the recombinant protein was eluted in the fractions containing 300 mM imidazole. The fractions with peak activity were pooled and exchanged with 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer (pH 6.0).

Enzyme kinetics.

Initial velocities of hydrolysis were monitored at a wavelength corresponding to the maximal change in absorbance between the unhydrolyzed substrate and the hydrolyzed product and included the following: cephaloridine, 254 nm; cefazolin, 272 nm; nitrocefin, 482 nm; cephapirin, 258 nm; cephalothin, 258 nm; cefamandole 269 nm; benzylpenicillin, 232 nm; amoxicillin, 235 nm; phenoxymethylpenicillin, 240; and azlocillin, 235 nm (1, 29). β-Lactamase assays were performed in 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer (pH 6.0) in 1-cm cuvettes at 37°C with a DU-70 recording spectrophotometer (Beckman Instruments, Fullerton, Calif.). For substrate profile determinations, 100 μM cephalosporins and 500 μM penicillins were used in the assays. For Km and Vmax determinations, the initial velocity of hydrolysis assays were performed with six cephalosporin concentrations ranging from 11.1 to 100 μM. Penicillin hydrolysis assays were performed with six to eight initial substrate concentrations ([s]) ranging from 70 to 1,000 μM. The Vmax and Km for each substrate-enzyme combination were determined from [s]/v against [s] plots (Hanes plots) (39), with computerized software (Hyper; Department of Biochemistry, University of Liverpool, Liverpool, United Kingdom). The turnover number, kcat, was calculated from Vmax by using a molecular mass of the purified recombinant Y49 β-lactamase of 30,000 g/mol.

Inhibition studies.

Purified recombinant Y49 enzyme was incubated with inhibitor at 37°C, and the residual activity was measured with 100 μM nitrocefin as a reporter substrate. The inactivation was studied with various concentrations of β-lactamase inhibitor (2 to 10 μM) by withdrawing the sample and determining the residual activity after different periods of time. The Ki value was determined as described by Galleni et al. (6). In the case of EDTA, the β-lactamase activity was assayed in the presence of 1 to 100 mM EDTA as described above.

RESULTS

β-Lactamase production and purification directly from M. tuberculosis H37Ra.

To determine whether M. tuberculosis β-lactamase activity is predominantly extracellular or cell associated, M. tuberculosis H37Ra was grown in 500 ml of Middlebrook 7H9 broth containing OADC supplemented with 0.05% Tween 80. After 3 to 4 weeks, the cultures were harvested, and the β-lactamase activities in the cell pellet and the broth supernatant were assayed separately. Under these conditions, the bulk of the β-lactamase activity from a 450-ml culture was found in the broth supernatant (554 U) rather than with the cell pellets (5.6 U).

The presence of albumin from the OADC supplement in the broth medium is needed for β-lactamase production, but it has complicated the purification protocol by making it necessary to subsequently separate the albumin from the β-lactamase. Attempts to eliminate the albumin entirely by using Sauton’s minimal medium and other media without albumin were unsuccessful due to greatly diminished β-lactamase production. It was eventually determined that the amount of albumin added to the Middlebrook 7H9 broth could be reduced from 50 to 12.5 g per liter without adversely affecting β-lactamase production.

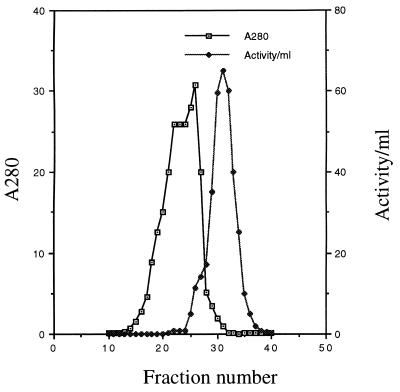

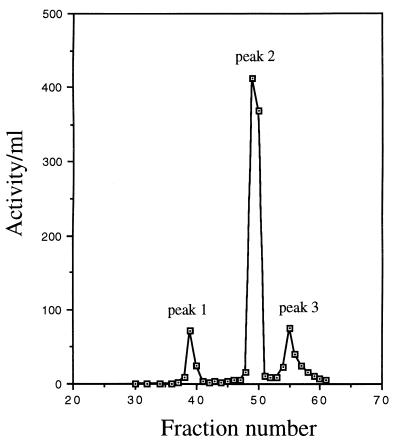

The usual purification protocol includes (i) ammonium sulfate precipitation of protein directly from the supernatant of 3 to 6 liters of 3- to 4-week-old cultures of M. tuberculosis H37Ra, with most of the β-lactamase activity being precipitated in the 50 to 62.5% fraction, (ii) G-75 Sephadex chromatography (Fig. 1), and (iii) chromatofocusing (Fig. 2). β-Lactamase has been recovered from the chromatofocusing column as three activity peaks. About 78% of the final β-lactamase activity was identified in peak 2 (Fig. 2 and Table 1), with 10 and 12% being present in peaks 1 and 3, respectively.

FIG. 1.

Partial purification of β-lactamase from M. tuberculosis H37Ra by gel filtration chromatography. Ammonium sulfate-precipitated protein from 5 liters of culture supernatant was suspended in 0.1 M sodium citrate and was loaded onto a G-75 Sephadex column. The eluted protein was collected in 10-ml fractions. The A280 value and the β-lactamase activity of each fraction are plotted. The large protein peak occurring before the peak of β-lactamase activity primarily comprises the bovine serum albumin added as a supplement to the broth culture.

FIG. 2.

Further purification of β-lactamase from M. tuberculosis H37Ra by chromatofocusing. Fractions with β-lactamase activity and a relatively low albumin concentration from gel filtration chromatography (e.g., fractions 29 to 36, Fig. 1) were pooled, concentrated, and loaded onto a Mono P column. The proteins were eluted in a linear pH gradient as 2-ml fractions. The β-lactamase activity of each fraction is plotted. Three peaks of β-lactamase activity were identified.

TABLE 1.

Recovery of M. tuberculosis β-lactamase during purificationa

| Step | Total activityb | Sp actc | Purifi- cation factord | Yield (%)d |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Broth supernatant | 15,100 | 0.8 | ||

| NH4SO4 precipitation | 8,600 | 13 | 16 | 56 |

| Gel filtration (G-75 Sephadex) | 5,400 | 81 | 100 | 36 |

| Chromatofocusing | 4,080 | 26 | ||

| Peak 1 | 400 | 370 | 462 | 2.6 |

| Peak 2 | 3,200 | 1,600 | 2,000 | 21.2 |

| Peak 3 | 480 | 700 | 875 | 3.2 |

| Anion exchange | 3,800 | 580 | 725 | 25 |

Values represent the average of six experiments. After gel filtration, the β-lactamase was purified further by either chromatofocusing (four experiments) or anion-exchange chromatography (two experiments).

Total activity is reported as nanomoles of nitrocefin degraded per minute in 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer (pH 6.0) at 37°C.

Specific activity determinations are reported as nanomoles of nitrocefin degraded per minute per milligram of protein. Protein concentrations were determined spectrophotometrically assuming an extinction coefficient at 280 nm of 1.0 for the protein.

Purification factor and percent yield are relative to the values for the broth supernatant.

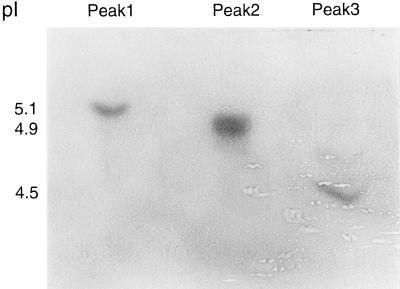

Isoelectric focusing.

Isoelectric focusing was performed with each peak fraction from the chromatofocusing. The three peaks corresponded to pI values of 5.1, 4.9, and 4.5, respectively (Fig. 3). Also, on some isoelectric focusing runs a minor band at pI 4.7 was observed, but it was never isolated from the chromatofocusing in quantities adequate for kinetic evaluation (data not shown). When DEAE anion-exchange chromatography instead of chromatofocusing was used to further purify the β-lactamase, isoelectric focusing of the post-DEAE fractions with peak activity identified the two bands corresponding to pI values of 5.1 and 4.9, respectively, whereas the pI 4.5 band was not observed (data not shown).

FIG. 3.

Isoelectric focusing of M. tuberculosis β-lactamases. A portion of the fractions corresponding to the three peaks of β-lactamase activity harvested during chromatofocusing were loaded onto a polyacrylamide gel. The proteins were separated by isoelectric focusing, and bands corresponding to the β-lactamase activity were identified by overlaying the gel with filter paper soaked with a solution of nitrocefin.

Expression, renaturation, and purification of recombinant Y49 β-lactamase.

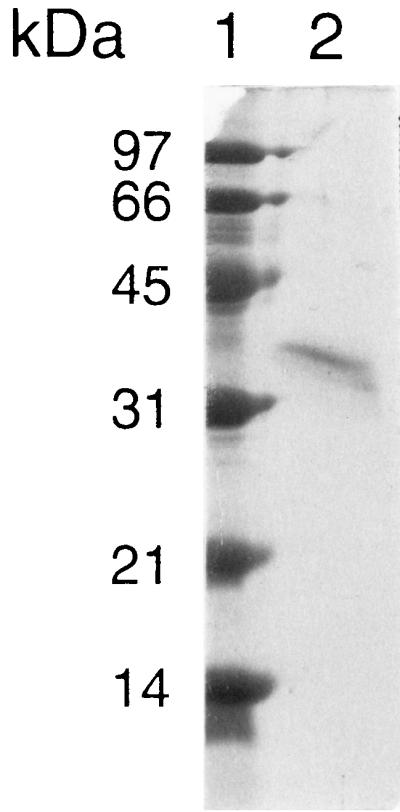

The recombinant Y49 β-lactamase was expressed as a fusion protein containing a six-histidine tag at the N terminus to facilitate easy purification on a nickel affinity column. The yield was 2 mg of recombinant protein per 100 ml of broth; however, most of it was found in inclusion bodies. Attempts to renature the purified recombinant after purification and elution from the nickel column were unsuccessful. Thus, a procedure was developed to renature the recombinant protein while it was attached to the nickel column. The purified, soluble, biologically active renatured form of the Y49 β-lactamase had a specific activity of 23,000 U per mg and yielded a single band above the 31-kDa marker on SDS-PAGE (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

SDS-PAGE of recombinant Y49 β-lactamase. The β-lactamase-containing fractions from nickel affinity chromatography were pooled, and 1 μg of protein was loaded onto an SDS–12% polyacrylamide gel. Lane 1, molecular mass markers; lane 2, purified recombinant Y49 β-lactamase. The six-histidine tag adds approximately 3 kDa to the mass of the recombinant Y49 β-lactamase.

Kinetic characteristics.

To determine whether the three activity peaks from the chromatofocusing column of material purified directly from M. tuberculosis represent different β-lactamases or the same β-lactamase, each peak fraction was evaluated kinetically. The kinetic characteristics of the first (pI 5.1) and second (pI 4.9) peak fractions were identical to each other, whereas the third peak exhibited a different kinetic profile (Table 2). Peaks 1 and 2 exhibited greater penicillinase activity, whereas peak 3 showed relatively greater cephalosporinase activity. The substrate profile of the recombinant Y49 β-lactamase is similar to those of peaks 1 and 2, indicating that the β-lactamase gene on cosmid Y49 encodes most of the β-lactamase activity that can be recovered directly from M. tuberculosis.

TABLE 2.

Substrate profiles of β-lactamases recovered directly from M. tuberculosis and recombinant Y49 β-lactamase

| Substratea | Relative rate of hydrolysisb

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peak 1c | Peak 2c | Peak 3c | Recombinant Y49 β-lactamased | |

| Benzylpenicillin | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Azlocillin | 234 | 200 | 91 | 153 |

| Nitrocefin | 78 | 82 | 216 | 84 |

| Cephaloridine | 5 | 9 | 55 | 8 |

| Cefazolin | 4 | 4 | 85 | 5 |

The substrate concentrations used in these determinations were 500 μM for the penicillins and 100 μM for the cephalosporins.

The initial velocity of hydrolysis of benzylpenicillin was fixed at 100, and the relative rate of hydrolysis of other substrates has been expressed as a percentage of the value for benzylpenicillin.

Peak 1, peak 2, and peak 3 refer to the partially purified enzyme in β-lactamase-containing fractions recovered directly from M. tuberculosis H37Ra by chromatofocusing (Fig. 2).

Recombinant Y49 β-lactamase refers to the purified recombinant β-lactamase, expressed in E. coli, which corresponds to the β-lactamase gene encoded on cosmid Y49.

The recombinant Y49 β-lactamase showed greater activity against most penicillins compared to its activity against the cephalosporin substrates (Table 3). It was particularly active against azlocillin, with a kcat value of 55 molecules of azlocillin hydrolyzed per second for every molecule of β-lactamase. Among the cephalosporins other than nitrocefin, the enzyme showed the greatest activity against cefamandole. The Ki values for recombinant Y49 β-lactamase with clavulanic acid and sulbactam were 0.4 and 0.5 μM, respectively. Clavulanic acid and sulbactam were also capable of inhibiting the peak 3 β-lactamase purified directly from M. tuberculosis, with Ki values of 1.1 and 3.6 μM, respectively. meta-Aminophenyl boronic acid inhibited the activity of the recombinant Y49 β-lactamase at high concentrations (i.e., 50% inhibition with 1,000 μM). The recombinant Y49 enzyme was not inhibited by EDTA even at high concentrations (100 mM).

TABLE 3.

Kinetic characteristics of recombinant Y49 β-lactamase from E. coli and β-lactamase obtained directly from M. tuberculosis

| Substrate | Kinetics of hydrolysisa

|

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recombinant Y-49 β-lactamase

|

Directly from M. tuberculosis

|

||||||||||

| Post-anion-exchange fraction

|

Chromatofocusing peak 2 fraction

|

||||||||||

| Km (μM) | kcat (s−1) | Relative Vmaxb | REHc | Ki (μM) | Km (μM) | Relative Vmaxb | REHc | Km (μM) | Relative Vmaxb | REHc | |

| Benzylpenicillin | 50 | 21 | 100 | 100 | 58 | 100 | 100 | 74 | 100 | 100 | |

| Phenoxymethylpenicillin | 38 | 20 | 95 | 125 | 78 | 70 | 66 | ||||

| Amoxicillin | 94 | 2 | 10 | 5 | 95 | 17 | 10 | ||||

| Azlocillin | 185 | 55 | 262 | 71 | 340 | 363 | 62 | 326 | 338 | 77 | |

| Nitrocefin | 81 | 31 | 147 | 91 | 114 | 180 | 92 | 105 | 185 | 131 | |

| Cephaloridine | 798 | 8 | 39 | 2 | 540 | 23 | 2 | ||||

| Cefazolin | 490 | 8 | 36 | 4 | 304 | 17 | 3 | ||||

| Cephalothin | 308 | 8 | 36 | 6 | 218 | 25 | 7 | ||||

| Cephapirin | 680 | 3 | 15 | 1 | 319 | 9 | 2 | ||||

| Cefamandole | 645 | 22 | 104 | 8 | 282 | 63 | 13 | 566 | 126 | 16 | |

| Cefuroximed | 0.4 | ||||||||||

| Ceftriaxoned | <0.5 | ||||||||||

| Clavulanic acid | 0.4 | ||||||||||

| Sulbactam | 0.5 | ||||||||||

Values for the recombinant Y49 β-lactamase and the pooled post-DEAE-cellulose anion-exchange chromatography fractions represent the averages of three or four assays of rates of hydrolysis of substrates. Values for the chromatofocusing peak 2, i.e., the pI 4.9 enzyme, were obtained from a single experiment.

Vmax values are relative to the Vmax of benzylpenicillin, which was assigned a value of 100. The measured Vmax values for benzylpenicillin were 41, 0.31, and 0.51 μmol hydrolyzed per min per mg of protein, respectively, for the purified recombinant Y49 β-lactamase, the pooled post-anion-exchange fractions (containing both the pI 5.1 and the pI 4.9 β-lactamases), and the peak 2 fraction (containing the pI 4.9 β-lactamase) obtained following chromatofocusing.

Relative efficiency of hydrolysis (REH) values are derived from the Vmax/Km ratio, with the benzylpenicillin value adjusted to 100. The other relative efficiency of hydrolysis values are expressed as a percentage of the value for benzylpenicillin.

The rates of degradation of cefuroxime and ceftriaxone were too low to obtain Km and Vmax values. For these β-lactams, the initial velocity of hydrolysis of a 100 μM solution of the cephalosporin is given as a percentage of the initial velocity of hydrolysis of a 1,000 μM solution of benzylpenicillin.

DISCUSSION

The major β-lactamase of M. tuberculosis is a class A β-lactamase which accounts for more than 80% of the total β-lactamase activity associated with broth cultures. Its nucleotide sequence has been determined and is encoded on cosmid Y49 (GenBank accession no. Z73966) of a chromosomal DNA library from M. tuberculosis H37Rv (27) and sequenced by the Sanger Centre. As observed with other class A β-lactamases, the Y49 β-lactamase has a molecular mass of about 30 kDa and a serine active site, and it is inhibited by clavulanic acid and m-aminophenylboronic acid but not by EDTA. It has predominant penicillinase activity and is identified by dual bands on isoelectric focusing with pI values of 5.1 and 4.9. Of interest, the demonstration of kcat and Vmax values of the Y49 β-lactamase for azlocillin higher than those for any other β-lactam probably explains why azlocillin can be added to primary mycobacterial isolation media including the BACTEC AFB system to inhibit the growth of other bacteria without having a serious adverse effect upon the recovery of clinical isolates of M. tuberculosis. The Y49 enzyme is probably produced by most M. tuberculosis strains and appears to be the enzyme that has been studied in earlier work regarding M. tuberculosis β-lactamase (15, 20, 40, 42).

The Y49 β-lactamase is associated with two distinct bands on isoelectric focusing. Zhang et al. (42) showed pI 5.1 and 4.9 bands to be present in each of 10 epidemiologically distinct isolates of M. tuberculosis. More recently, Hackbarth et al. (7) sequenced the β-lactamase gene from M. tuberculosis H37Ra (GenBank accession no. U67924) and found it to be identical to that of H37Rv. When this gene was expressed in Mycobacterium smegmatis, they found that isoelectric focusing results were a composite of those for M. smegmatis (bands at pI values of 5.4 and 4.3) and M. tuberculosis (bands at pI values of 5.1 and 4.9). The derivation of both the pI 5.1 and 4.9 bands from the same gene is further supported by our finding that the substrate profiles of the pI 5.1 and 4.9 bands when separated by chromatofocusing were identical. Apparently, the Y49 β-lactamase gene gives rise to two stably modified forms of the same enzyme. Protein oxidation and/or ragged N termini of the same β-lactamase related to protease activity might account for multiple bands on isoelectric focusing of a single β-lactamase. A highly plausible possibility is that one represents a true exoenzyme form of the enzyme, whereas the other is cross-linked at the N terminus to a membrane-associated lipid. This is the case for other gram-positive bacteria which produce extracellular β-lactamases (24). For example, in many strains of Staphylococcus aureus, about 50% of the β-lactamase exists in the extracellular form and about 50% exists in the membrane-bound form. Minor but insignificant differences in the kinetic properties of the extracellular and membrane-bound forms of staphylococcal β-lactamase have been reported (16), even though they represent stable forms of the same β-lactamase. We might be observing a similar phenomenon with the Y49 β-lactamase.

There is growing evidence that M. tuberculosis produces one or more β-lactamases in addition to the Y49 enzyme. We identified an enzyme that had a pI value of 4.5 and predominant cephalosporinase activity but that is clearly different from the Y49 enzyme. It was harvested in the same fractions off the G-75 Sephadex column as the Y49 enzyme, suggesting a molecular mass also in the 30-kDa range. Our studies indicate that this enzyme is also inhibited by clavulanic acid and sulbactam. Furthermore, we also observed slight β-lactamase activity in fractions from G-75 Sephadex chromatography eluting before the major β-lactamase (e.g., fractions 26 and 27 in Fig. 1, whereas the major β-lactamase eluted in fractions 29 to 35). Upon isoelectric focusing of these fractions a band of nitrocefin hydrolysis with a pI value of >6.0 was observed (data not shown). The presence of this band with a higher pI value only in the initial fractions with β-lactamase activity and its incomplete separation from the albumin peak that accounts for most of the absorbance in these fractions suggests that it has a higher molecular mass than the Y49 β-lactamase.

Candidates for other β-lactamase genes can be found among data made available through M. tuberculosis genome sequencing efforts. BLAST searches of the Sanger Centre site on the World Wide Web by using the amino acid sequence of Mycobacterium fortuitum β-lactamase (1, 6) as the search parameter identifies a candidate open reading frame (ORF) in cosmid Y6F7 (now recorded under GenBank accession no. Z95555) encoding a protein of unknown function. Although large, with a deduced sequence of 491 amino acids, this protein contains structural features common to class A β-lactamases (i.e., S-x-x-K active site, S-D-N loop, -E- acidic residue, and D-K-T-G motif [11]).

In addition, the Sanger Centre has reported the presence of part of an ORF with homology to class C β-lactamases in cosmid Y31 (GenBank accession no. Z73101). Because only a portion of the ORF was contained within Y31, we amplified this portion by PCR and used it as a probe to identify and clone a 3.5-kb BamHI fragment of M. tuberculosis chromosomal DNA containing the remainder of the gene (17). Sequencing of an additional 900 bp of this gene followed by using this sequence as the search parameter for another BLAST search at the Sanger Centre Web site revealed identity with part of another cosmid (Y21C12; now recorded under GenBank accession no. Z95210). The complete ORF of the gene bridging cosmids Y31 and Y21C12 encodes a protein bearing homology to the class C β-lactamases of gram-negative aerobic species as well as carboxypeptidases. Furthermore, another M. tuberculosis ORF with strong homology to class C β-lactamases is located on cosmid 4C12 (now recorded under GenBank accession no. Z81360).

It is not yet clear whether any of these gene products correlates with the bands with pI values of 4.5 and >6.0 and β-lactamase activity which we observe on isoelectric focusing. Their estimated molecular masses are 53 to 55 kDa; this includes the mass of the leader peptide. This is larger than most class C β-lactamases, and it could be that they are carboxypeptidases (i.e., d-alanyl-d-alanine peptidases) with some β-lactamase activity. Chambers et al. identified a 52-kDa PBP in cell membranes of M. tuberculosis (3), and on gels this band had the appearance of a doublet (4), further suggesting the presence of penicillin-interactive proteins of about this size. The issue of whether these proteins represent carboxypeptidases or β-lactamases may best be answered by determining the turnover numbers (kcat values) for β-lactams by using purified enzymes, although the answer might be ambiguous because some carboxypeptidases hydrolyze β-lactams fairly efficiently. Because the amounts of these enzymes that can be recovered directly from M. tuberculosis in culture are too small to permit a more detailed analysis than that reported in this paper, overexpression of the genes in recombinant form may be the most plausible strategy for evaluating these proteins further.

We found that most of the β-lactamase activity recovered directly from M. tuberculosis was found in the broth culture rather than in the cell pellet. This is in contrast to the reports of some earlier investigations, in which the β-lactamase was believed to be either intracellular or membrane bound (10, 12, 15, 40). The difference between the findings presented in those other reports and our observations may be due, in part, to the use of Tween 80 in the broth medium. Tween 80 is a nonionic detergent that minimizes cell clumping and acts to disperse tubercle bacilli as single cells (18, 34). Kasik et al. (14) reported that “cell-free mycobacterial penicillinase” could be obtained by incubating M. tuberculosis in liquid Dubos media containing Tween-albumin. In contrast, glycerol- and oleic acid-based media promote the clumping of cells into macroscopic aggregates. Our results are consistent with studies showing that the β-lactamases of other mycobacterial species including M. fortuitum and M. smegmatis are also predominantly extracellular (1, 28).

Finally, the therapeutic options for the management of tuberculosis caused by multidrug-resistant strains are often limited. β-Lactam antibiotics are extensively developed, highly effective, widely used, and relatively nontoxic antimicrobial agents. The evaluation of β-lactam activity against M. tuberculosis in vitro and the further study of mycobacterial β-lactamases should help in identifying which β-lactams have the greatest promise of efficacy in vivo.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by U.S. Public Health Service grant AI-35250 from the National Institutes of Health.

We are grateful to Hiriam Gates for assistance in the purification of M. tuberculosis β-lactamase. We thank Charles W. Stratton for technical advice with isoelectric focusing and for providing us with β-lactamases with low pI values that were used as standards to calculate the pI values of the M. tuberculosis enzymes. We thank Stewart Cole of the Institut Pasteur in Paris, France, for notifying us in June 1996 that a gene with homology to known β-lactamases had been identified on cosmid Y49. We thank the Sanger Centre for maintaining a Web site with a BLAST search engine from which the DNA sequences of the Y49 β-lactamase and other mycobacterial genes could be retrieved.

REFERENCES

- 1.Amicosante G, Franceschini N, Segatore B, Oratore A, Fattoroni L, Orefici G, Van Beeumen J, Frére J M. Characterization of beta-lactamase produced in Mycobacterium fortuitum D316. Biochem J. 1990;271:729–734. doi: 10.1042/bj2710729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bloom B R, Murray C J L. Tuberculosis: commentary on a reemergent killer. Science. 1992;257:1055–1064. doi: 10.1126/science.257.5073.1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chambers H F, Moreau D, Yajko D, Miick C, Wagner C, Hackbarth C, Kocagoz S, Rosenberg E, Hadley W K, Nikaido H. Can penicillins and other beta-lactam antibiotics be used to treat tuberculosis? Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:2620–2624. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.12.2620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chambers, H. F. Personal communication.

- 5.Cynamon M H, Palmer G S. In vitro activity of amoxicillin in combination with clavulanic acid against Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1983;24:429–431. doi: 10.1128/aac.24.3.429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Galleni M, Franceschini N, Quinting B, Fattorini L, Orefici G, Oratore A, Frére J M, Amicosante G. Use of chromosomal class A beta-lactamase of Mycobacterium fortuitum D316 to study potentially poor substrates and inhibitory beta-lactam compounds. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1994;38:1608–1614. doi: 10.1128/aac.38.7.1608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hackbarth C J, Unsal I, Chambers H F. Cloning and sequence analysis of a class A β-lactamase from Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Ra. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:1182–1185. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.5.1182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heifets L B, Iseman M D, Cook J L, Lindholm-Levy P J, Drupa I. Determination of in vitro susceptibility of Mycobacterium tuberculosis to cephalosporins by radiometric and conventional methods. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1985;27:11–15. doi: 10.1128/aac.27.1.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Iland C N. The effect of penicillin on the tubercle bacillus. J Pathol Bacteriol. 1946;58:495–500. doi: 10.1002/path.1700580320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Iland C N, Baines S. The effect of penicillin on the tubercle bacillus: tubercle penicillinase. J Pathol Bacteriol. 1949;61:329–335. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Joris B, Ledent P, Dideberg O, Fonzé E, Lamotte-Brasseur J, Kelly J A, Ghuysen J M, Frère J M. Comparison of the sequences of class A β-lactamases and of the secondary structure elements of penicillin-recognizing proteins. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1991;35:2294–2301. doi: 10.1128/aac.35.11.2294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kasik J E. The nature of mycobacterial penicillinase. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1965;91:117–119. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1965.91.1.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kasik J E, Weber M, Winberg E, Barclay W R. The synergistic effect of dicloxacillin and penicillin G on murine tuberculosis. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1966;94:260–261. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1966.94.2.260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kasik J E, Weber M, Freehill P J. The effect of the penicillinase-resistant penicillins and other chemotherapeutic substances on the penicillinase of the R1Rv strain of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1967;95:12–19. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1967.95.1.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kasik J E. Mycobacterial beta-lactamases. In: Hamilton-Miller J M T, Smith J T, editors. Beta-lactamases. London, United Kingdom: Academic Press; 1979. pp. 339–350. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kernodle D S, McGraw P A, Stratton C W, Kaiser A B. Use of extracts versus whole-cell bacterial suspensions in the identification of Staphylococcus aureus beta-lactamase variants. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1990;34:420–425. doi: 10.1128/aac.34.3.420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kernodle, D. S., and R. K. R. Voladri. Unpublished data.

- 18.Kirby W M M, Dubos R J. Effect of penicillin on the tubercle bacillus in vitro. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1947;66:120–123. doi: 10.3181/00379727-66-16004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kochi A. The global tuberculosis situation and the new control strategy of the World Health Organization. Tubercle. 1991;72:1–6. doi: 10.1016/0041-3879(91)90017-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kwon H H, Tomioka H, Saito H. Distribution and characterization of β-lactamases of mycobacteria and related organisms. Tuberc Lung Dis. 1995;76:141–148. doi: 10.1016/0962-8479(95)90557-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lorian V, Sabath L D. The effect of some penicillins on Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1972;105:632–637. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1972.105.4.632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mishra R K, Kasik J E. The mechanisms of mycobacterial resistance to penicillins and cephalosporins. Int J Clin Pharmacol. 1970;3:73–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Misiek M, Moses A J, Pursiano T A, Leitner F, Price K E. In vitro activity of cephalosporins against Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv: structure-activity relationships. J Antibiot. 1973;26:737–744. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.26.737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Neilsen J B K, Lampen J O. Membrane-bound penicillinases in gram-positive bacteria. J Biol Chem. 1982;257:4490–4495. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nitta A T, Iseman M D, Newell J D, Madsen L A, Goble M. Ten-year experience with artificial pneumoperitoneum for end-stage, drug-resistant pulmonary tuberculosis. Clin Infect Dis. 1993;16:219–222. doi: 10.1093/clind/16.2.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.O’Callaghan C H, Morris A, Kirby S M, Singler A H. Novel method for detection of β-lactamase by using a chromogenic cephalosporin substrate. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1972;1:283–288. doi: 10.1128/aac.1.4.283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Philipp W J, Poulet S, Eiglmeier K, Pascopella L, Balasubramanian V, Heym B, Bergh S, Bloom B R, Jacobs W R, Jr, Cole S T. An integrated map of the genome of the tubercle bacillus, Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv, and comparison with Mycobacterium leprae. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:3132–3137. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.7.3132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Quining B, Galleni M, Timm J, Gicquel B, Amicosante G, Frére J M. Purification and properties of the Mycobacterium smegmatis mc(2)155 beta-lactamase. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1997;149:11–5. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1097(97)00041-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ross G W, Chanter K V, Harris A M, Kirby S M, Marshall M J, O’Callaghan C H. Comparison of assay techniques for beta-lactamase activity. Anal Biochem. 1974;54:9–16. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(73)90241-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sanders W E, Jr, Schneider N, Hartwig C, Cacciatore R, Valdez H. Comparative activity of cephalosporins against mycobacteria. In: Nelson J D, Grassi C, editors. Current chemotherapy and infectious disease. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1980. pp. 1075–1077. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Solotrovsky M, Iland C N. The effect of penicillin on the growth of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in Dubos’ medium. J Bacteriol. 1948;55:555–559. doi: 10.1128/jb.55.4.555-559.1948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Soltys M A. Effect of penicillin on mycobacteria in vitro and vivo. Tubercle. 1952;33:120–125. doi: 10.1016/s0041-3879(52)80054-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sorg T B, Cynamon M H. Comparison of four β-lactamase inhibitors in combination with ampicillin against Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1987;19:59–64. doi: 10.1093/jac/19.1.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stinson M W, Solotorovsky M. Interaction of Tween 80 detergent with mycobacteria in synthetic medium. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1971;104:717–727. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1971.104.5.717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sudre P, ten Dam G, Kochi A. Tuberculosis: a global overview of the situation today. Bull W H O. 1992;70:149–159. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Watt B, Edwards J R, Rayner A, Grindey A J, Harris G. In vitro activity of meropenem and imipenem against mycobacteria: development of a daily antibiotic dosing schedule. Tuberc Lung Dis. 1992;73:134–136. doi: 10.1016/0962-8479(92)90145-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Winder F G. Mode of action of the antimycobacterial agents and associated aspects of the molecular biology of the mycobacteria. In: Ratledge C, Stanford J, editors. The biology of the mycobacteria. New York, N.Y: Academic Press, Inc.; 1982. pp. 53–138. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wong C S, Palmer G S, Cynamon M H. In-vitro susceptibility of Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Mycobacterium bovis and Mycobacterium kansasii to amoxycillin and ticarcillin in combination with clavulanic acid. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1988;22:863–866. doi: 10.1093/jac/22.6.863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wong J T. Kinetics of enzyme mechanisms. New York, N.Y: Academic Press, Inc.; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Woodruff H B, Foster J W. Microbiological aspects of penicillin. VII. Bacterial penicillinase. J Bacteriol. 1945;49:7–29. doi: 10.1128/jb.49.1.7-17.1945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yew W W, Wong C F, Lee J, Wong P C, Chau C H. Do β-lactam–β-lactamase inhibitor combinations have a place in the treatment of multidrug-resistant pulmonary tuberculosis? Tuberc Lung Dis. 1995;76:90–92. doi: 10.1016/0962-8479(95)90588-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang Y, Steingrube V A, Wallace R J., Jr Beta-lactamase inhibitors and the inducibility of the beta-lactamase of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1992;145:657–660. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/145.3.657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]