Abstract

In China, there is a lack of data regarding the awareness and treatment preferences among patients with vitiligo and their families. To address this gap, a cross-sectional questionnaire-based study was conducted to investigate disease awareness and treatment preferences in Chinese patients with vitiligo. The study also evaluated willingness to pay, using 2 standardized items, and assessed quality of life, using the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) score. Data from 307 patients with vitiligo (59.3% women, mean age 28.98 years, range 2–73 years) were analysed. Of these patients, 44.7% had insufficient knowledge of vitiligo, particularly those from rural areas or with low levels of education. Mean DLQI total score was 4.86 (5.24 for women and 4.30 for men). Among the most accepted treatments were topical drugs, phototherapy, and systemic therapy. Patients were relatively conservative about the duration and cost of treatment, with only 27.7% willing to pay more than 10,000 Chinese yuan renminbi (CNY) for complete disease remission. High level of education, high income, skin lesions in specific areas, and skin transplantation therapy predicted higher willingness to pay. Insufficient knowledge was associated with a higher burden of disease. In order to reduce the disease burden and improve treatment adherence it is crucial to enhance disease awareness and take into account patient preferences.

SIGNIFICANCE

This study investigated disease awareness and treatment preferences in 307 Chinese patients with vitiligo. Results indicated that 44.7% of patients lacked knowledge about the disease, particularly those from rural areas or with low levels of education. Insufficient knowledge was associated with a higher burden of disease. High level of education, high income, skin lesions in specific areas and skin transplantation therapy predicted higher willingness to pay for treatment. These data support enhancing disease awareness and taking into account patient preferences in order to reduce disease burden and improve treatment adherence.

Key words: awareness, quality of life, treatment preference, vitiligo, willingness to pay

Vitiligo is a common skin disease characterized by loss of epidermal melanocytes, resulting in white patches on the skin (1, 2). Worldwide, the prevalence of vitiligo ranges from 0.1% to 2% (3). In China, the prevalence of vitiligo is 0.54%, with males having a higher prevalence (0.71%) than females (0.41%) (1). Almost 50% of people with vitiligo develop the condition before the age of 20 years, and nearly 32–37% of these have childhood-onset vitiligo before the age of 12 years (4). Vitiligo is still not fully recognized by the general public, and patients may be misdiagnosed with pityriasis versicolor or mycosis at the initial visit to a GP (5). Despite being a non-fatal condition, vitiligo can have a significant impact on health-related quality of life (HRQoL), leading to psychological distress and stigmatization of patients due to their appearance (6, 7).

In the 10 years since the healthcare reform plan “Opinions of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China and The State Council on Deepening the Reform of the Medical and Health System (Zhongfa (2009) No. 6), China has made steady progress in fairness in access to care and strengthening financial protection, especially for lower socioeconomic groups. However, there are still deficiencies in service efficiency, control of healthcare expenditure, and public satisfaction (8). In a 2017 satisfaction survey on the cost of living, 28% of respondents stated that paying for healthcare was the biggest financial burden on their household expenses. Meanwhile, 12% of respondents ranked healthcare as the least satisfying aspect of life, second only to income (28%) (8, 9). Physicians can assess disease severity and patient satisfaction by recording quality of life (QoL) parameters. Currently, the impact of diseases on QoL is commonly assessed using validated questionnaires. Both the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) and Willingness to Pay (WTP) are considered appropriate tools for assessing disease burden. WTP estimates patient preferences and the monetary value of health benefits by asking the maximum amount a person is willing to spend on disease treatment (10). The WTP concept has been applied to various skin diseases, including acne and atopic dermatitis (11–13).

While several studies have investigated the impact of vitiligo on QoL (14, 15), evidence on its impact and preferences for treatment among Chinese patients is insufficient and inconclusive. The aims of this study are to investigate the disease awareness and treatment preferences of Chinese patients with vitiligo, and to evaluate disease burden using WTP and DLQI.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design and participants

This cross-sectional, non-interventional study was conducted at the Third Xiangya Hospital of Central South University, Changsha, China, between March 2021 and August 2022. Exclusion criteria were: (i) patients who had not been diagnosed with vitiligo by a dermatologist; (ii) patients who were illiterate or had dysgnosia; (iii) patients with vitiligo who were unable to complete the questionnaire due to other serious psychological or physical disorders; (iv) patients who were unwilling to participate in the survey and evaluation. In general, children do not possess fully developed cognitive abilities, so the children’s Dermatology Life Quality Index (CDLQI) questionnaire was completed by their parent/carer. Furthermore, we evaluated the parent/ carer’s preference for treatment. On the other hand, for adult participants, we assessed their quality of life (DLQI), disease awareness, and preference for treatment. To ensure participant confidentiality, data were collected and sorted anonymously. All participants provided informed consent, and the Institutional Review Board of the Third Xiangya Hospital of Central South University approved the study (number 21132).

Data extraction from the questionnaire and data definition

For the vitiligo cognition test item, a score of 1 was given for each correct answer and 0 for incorrect answers. Overall scores of 0–4, 5–6, and 7–8 indicated “insufficient”, “medium”, and “sufficient” knowledge of vitiligo, respectively. The QoL evaluation was conducted using the DLQI or CDLQI, which offers response options including “very severe”, “severe”, “mild”, “none”, and “irrelevant”. Scores were categorized as follows: “no” or “irrelevant” = 0, “minor” = 1, “severe” = 2, and “very severe” = 3. The overall score ranged from 0 to 30, with higher scores indicating worse QoL. A total score of 0–1 indicated no impact, 2–5 indicated mild impact, 6–10 indicated moderate impact, 11–20 indicated severe impact, and 21–30 indicated very serious impact.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive analysis was conducted for all data, including absolute and percentage frequencies. For continuous variables, such as age, values (mean and median) and the scattering (SD, range) were calculated. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05 for all analyses, which were 2-tailed. Two-sample t-tests and analysis of variance (ANOVA) were used for analysing measurement data, while Pearson’s χ2 (or Fisher’s exact) tests were used for categorical data. Non-parametric tests, such as the Mann–Whitney U test and Kruskal–Wallis H test, were used to compare rank data. Correlations were analysed using Spearman’s rank test (rs). Binary logistic regression was used to determine predictors for DLQI, while multinomial logistic regression was used to examine cognitive level of vitiligo as an outcome variable. Finally, ordinal logistic regression was used for eliciting predictors of WTP using multiple regression models. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 26.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA), and covariates were preserved in the multivariate models based on confounding and effect modifications considerations.

RESULTS

Characteristics of the patients

This study investigated the characteristics of 307 patients with vitiligo, including sex, age, educational level, residential location, and annual household income. Of the included patients, 59.3% were female and 40.7% were male, with a mean age of 28.98 ± 14.86 years (median age 28 years, age range 2–73 years). Most patients were aged between 11 and 50 years (79.1%). Urban areas were the main residential location (70.7%), with most patients having a bachelor’s degree or above (37.1%) and an annual household income of less than 80,000 Chinese yuan renminbi (CNY) (Note: US$1 was equivalent to about 7.34 CNY) (47.9%) (Fig. S1).

The mean age of onset was 25.34 ± 14.83 years, with disease onset being highest in the age group 11–20 years (27.7%). Most patients (67.4%) had < 1% affected body sites The visible body areas commonly affected were the face and neck (23.0%) and trunk (18.0%). Over a third of patients (39.4%) reported expanding white spots or emerging lesions, and 60.3% did not know the distribution of their skin lesions. Only 30 patients (9.8%) had a family history of vitiligo. Comorbidities were reported by 10.7% of patients, including thyroid disease (n = 10), type 1 diabetes (n = 5), and depression (n = 4) (Fig. S2).

Disease awareness and information sources among patients with vitiligo

The study examined 244 patients over 18 years of age, in order to assess their cognitive level of vitiligo, by testing their ability to answer 8 questions (Q1–Q8) (Fig. 1a). The questions about consuming vitamin C-rich foods (Q6, 37.3%) and identifying vitiligo (Q4, 34.8%) were the 2 least correctly answered. It is notable that 44.7% of participants had insufficient knowledge, and only 11.5% had sufficient knowledge, of vitiligo (Fig. 1b). The study also asked patients to rate their understanding of the cause of vitiligo on a scale of 0–10 and found a mean score of 3.69 ± 2.78. Using 9 possible options for factors that trigger vitiligo, it was found that mental stress and anxious-depressive disorder were accurately identified as triggers by more than 50% of participants (70.9% and 56.6%, respectively), but 17.2% of patients incorrectly identified vitamin C-rich foods as a trigger (Fig. 1c). In addition, patients mainly obtained information from doctors (85.2%) and the internet (61.9%), with medical popularization platforms being a desired source of information for 49.6% of patients (Fig. 1d–e).

Fig. 1.

Awareness of vitiligo and information sources among patients with vitiligo. (a) Accuracy of vitiligo awareness test questions. Q1: Do you think vitiligo is infectious? Q2: Do you think vitiligo is hereditary? Q3: Do you think vitiligo is an autoimmune disease? Q4: Do you think the white spots on your body must be vitiligo? Q5: Do you think patients with vitiligo should spend more time in the sun? Q6: Do you think vitamin C should not be consumed by vitiligo patients? Q7: Do you think vitiligo can be completely cured? Q8: Do you think vitiligo can heal by itself without treatment? (b) Score of the vitiligo cognitive test for the patients with vitiligo. (c) Patients’ answers about the 9 triggering factors of vitiligo. (d) Access to information about vitiligo among patients. (e) The acceptable access to information about vitiligo for patients.

The study analysed factors associated with disease awareness in 244 patients with vitiligo and found that 3 demographic variables (age, education, and residential location) and 2 disease characteristics (disease duration and change in vitiligo lesions) were significantly associated with knowledge of vitiligo (p < 0.05). Using these results, a knowledge evaluation regression model was developed (Table I). This showed that age was negatively associated with knowledge of vitiligo (adjusted odds ratio (aOR) 0.972; (95% confidence interval (95% CI) 0.947–0.997); p = 0.031). Patients with middle-school education were more likely to have insufficient knowledge (aOR 0.288; 95% CI 0.090–0.918; p = 0.035), and urban habitation was associated with sufficient knowledge (aOR 3.103; 95% CI 1.402–6.871; p = 0.005).

Table I.

Analysis of the association between the cognitive level of vitiligo, confounding variables, and disease characteristics

| Variable | Cognitive level of vitiligo | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mediuma | Sufficienta | |||

| aORs (95% CI) | p-value | aORs (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Age, years | 0.972 (0.947–0.997) | 0.031 | 0.972 (0.927–1.019) | 0.236 |

| Education | ||||

| Primary school or below | 1.263 (0.079–20.236) | 0.869 | 1.951 (0.090–9.390) | 0.437 |

| Middle-school | 0.288 (0.090–0.918) | 0.035 | 0.372 (0.036–3.822) | 0.405 |

| High-school | 0.654 (0.277–1.545) | 0.333 | 0.787 (0.192–3.224) | 0.739 |

| Technical college | 1.047 (0.474–2.314) | 0.910 | 1.785 (0.536–5.940) | 0.345 |

| Bachelor’s degree or above | 1 [reference] | NA | 1 [reference] | NA |

| Residential location | ||||

| Rural | 1 [reference] | NA | 1 [reference] | NA |

| Urban | 3.103 (1.402–6.871) | 0.005 | 2.013 (0.529–7.656) | 0.305 |

| Annual household income (CNY) | ||||

| < 80,000 | 1 [reference] | NA | 1 [reference] | NA |

| 80,000–160,000 | 0.786 (0.358–1.727) | 0.549 | 2.248 (0.614–8.236) | 0.221 |

| 160,000–240,000 | 1.194 (0.472–3.021) | 0.708 | 2.203 (0.471–10.306) | 0.316 |

| 240,000–320,000 | 0.370 (0.070–1.967) | 0.243 | NA | NA |

| > 320,000 | 1.199 (0.318–4.525) | 0.789 | 2.919 (0.453–18.806) | 0.260 |

| Disease duration | ||||

| < 6 weeks | 0.745 (0.193–2.878) | 0.669 | NA | NA |

| 6 weeks–0.5 year | 1.839 (0.611–5.533) | 0.279 | 0.629 (0.053–7.419) | 0.713 |

| 0.5–1 year | 1.712 (0.637–4.605) | 0.287 | 4.065 (0.927–17.821) | 0.063 |

| 1–3 years | 1.834 (0.696–4.835) | 0.220 | 2.659 (0.575–12.303) | 0.211 |

| 3–5 years | 3.876 (0.827–18.175) | 0.086 | 5.829 (0.734–46.286) | 0.095 |

| > 5 years | 1 [reference] | NA | 1 [reference] | NA |

Multinomial logistic regression model were constructed with the cognitive level of vitiligo (insufficient, medium and sufficient) as the outcome variable. This model included potential confounding variables and age was included as covariate. There were no significant interactions between the cognitive level of vitiligo, disease duration, treatment duration and other covariates in the multivariate model.

aOR: adjusted odds ratio; NA: not applicable.

Evaluation of Dermatology Life Quality Index and possible risk factors

The mean total DLQI score was 5.02 ± 5.25 (n = 244, age ≥ 18 years), while for CDLQI it was 4.21 ± 5.26 (n = 63, age < 18 years). Women had a higher score than men (5.24 ± 5.65 vs 4.30 ± 4.57). Approximately 13.0% of patients with vitiligo had a DLQI > 10, indicating severe reduction in QoL. The degree of impact on QoL was distributed based on the DLQI total score (Fig. 2b), with “work” and “shame” having the greatest impact on QoL (Fig. 2a). In contrast, CDLQI showed different results, with “treatment” and “ being bullied “ being significant factors affecting children’s QoL (Fig. 2c).

Fig. 2.

Evaluated Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI). (a) Percentage of adult patients by DLQI items rated moderately or severely affected (n = 244). (b) Distribution of the DLQI score among the patients with vitiligo (n = 307). (c) Percentage of child patients by Children’s Dermatology Life Quality Index (CDLQI) items rated as often or frequently affected (n = 63).

There was a slightly negative correlation of DLQI with residential location (rs = –0.155, p = 0.006), indicating rural patients had more intense QoL restrictions. DLQI correlated positively with vitiligo lesion area (% of body surface area) (rs = 0.214, p = 0.000), suggesting more severe reduction in QoL in extensively affected patients. Patients with affected hands and feet (p = 0.042) and external genitals (p = 0.000) had significantly higher DLQI scores than the corresponding negative counterparts (Table SI). In addition, DLQI scores also differed based on cognitive level of vitiligo (H = 5.765, p = 0.056), which warrants further investigation.

All of these factors were included in binary logistic regression analysis (Table II). The bivariate model show-ed a significantly higher aOR between DLQI and the following clinical situations: (primary school or below: aOR 11.652 (95% CI 2.092–64.911), p = 0.005; stable vitiligo: aOR 0.221 (95% CI 0.068–0.716), p = 0.012; vitiligo lesion area of 1–5%: aOR 3.750 (95% CI 1.524–9.227), p = 0.004; external genitals affected: aOR 3.597 (95% CI 1.274–10.153), p = 0.016).

Table II.

Possible predictors independently associating with Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) total score

| Variable | DLQI total scorea | |

|---|---|---|

| aORs (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Education | ||

| Primary school or below | 11.652 (2.092–64.911) | 0.005 |

| Middle-school | 1.723 (0.476–6.234) | 0.407 |

| High-school | 1.146 (0.356–3.686) | 0.820 |

| Technical college | 0.403 (0.117–1.385) | 0.149 |

| Bachelor’s degree or above | 1 [reference] | NA |

| Changes in vitiligo lesions within 6 months | ||

| Expand or emerging lesion | 1 [reference] | NA |

| Stable | 0.221 (0.068–0.716) | 0.012 |

| Pigmentation | 0.581 (0.223–1.513) | 0.266 |

| Vitiligo lesion area (% of body surface area) | ||

| < 1% | 1 [reference] | NA |

| 1–5% | 3.750 (1.524–9.227) | 0.004 |

| 6–50% | 0.975 (0.157–6.075) | 0.979 |

| > 50% | 1.625 (0.114–23.219) | 0.720 |

| External genitals | ||

| Absent | 1 [reference] | NA |

| Present | 3.597 (1.274–10.153) | 0.016 |

Binary logistic regression models were constructed with DLQI total score (DLQI ≤ 10 vs DLQI > 10) as the binary dependent (outcome) variable. The adjusted odds ratio (aORs) were determined from multivariate models by including the sex, current age, residential location, annual household income and disease duration. The education, changes in vitiligo lesions within 6 months, vitiligo lesion area, and the site of lesions were included as covariates. There were no significant interactions between the DLQI total score and other covariates in the multivariate model.

CI: confidence interval; NA: not applicable.

Treatment preferences and willingness to pay

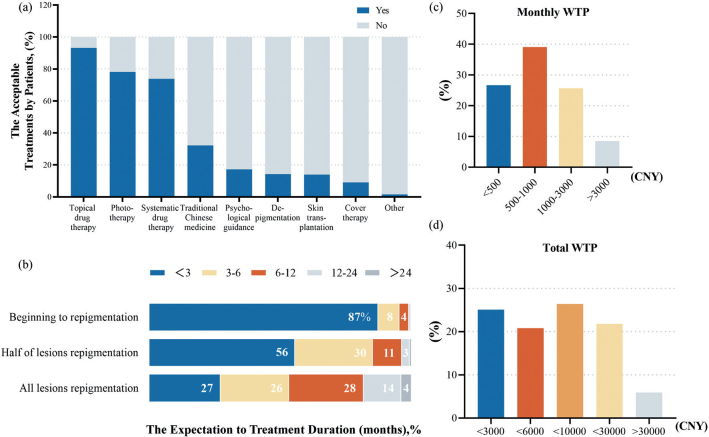

Based on the questionnaire, most patients preferred topical drugs (93.2%), followed by phototherapy (78.2%), systemic drugs (73.9%), traditional Chinese medicine (32.2%), and skin transplantation therapy (14.0%) (Fig. 3a). Regarding treatment duration, 87.3% of patients expected to begin repigmentation within 3 months, and 55.7% expected half of the lesions to repigment within 3 months. The majority of respondents expected a cure within 0–3 months (27.4%), 3–6 months (26.1%), and 6–12 months (28.3%), respectively (Fig. 3b).

Fig. 3.

Patient preferences for treatment and willingness to pay (WTP). (a) Treatments acceptable to patients. (b) Expectation of treatment duration (months). (c) Distribution of the results of monthly WTP (CNY). (d) Distribution of the results of total WTP (CNY).

WTP was determined to further objectify the disease burden. When asked to state an acceptable monthly treatment cost, 26.7%, 39.1%, 25.7% and 8.5% were willing to pay from 0–500 CNY, 500–1,000 CNY, 1,000–3,000 CNY and more than 3,000 CNY, respectively (Fig. 3c). Meanwhile, 25.1%, 20.8% and 26.4% were willing to make a single payment of up to 3,000 CNY, 6,000 CNY and 10,000 CNY, respectively, while only 27.7% were willing to pay more than 10,000 CNY for cure (Fig. 3d). Total and monthly WTP were significantly correlated (rs = 0.578, p = 0.000), and awareness of vitiligo was positively associated with total WTP (H = 6.123, p = 0.047).

To further determine the variables influencing WTP, non-parametric tests were performed. associated with higher total WTP included education level, annual household income, disease duration, vitiligo lesion area, cognitive level of vitiligo, involvement of limbs, hands and feet, and hair/eyebrows/eyelashes, and skin transplantation therapy (Table SII). All of these were considered potential factors and included in the multivariate analysis (Table III). In this model, the association between total WTP and the following clinical situations had significantly higher aOR (bachelor’s degree or above: aOR 4.768 (95% CI 1.303–17.444), p = 0.018; annual household income more than 320,000 CNY: aOR 6.246 (95% CI 2.421–16.119), p = 0.000; disease duration of 1–3 years: aOR 5.966 (95% CI 2.079–17.116), p = 0.001; limbs affected: aOR 2.010 (95% CI 1.076–3.751), p = 0.029; hair/eyebrows/eyelashes affected: aOR 2.186 (95% CI 1.200–3.983), p = 0.011; skin transplantation therapy: aOR 5.894 (95% CI 2.034–17.064), p = 0.001.

Table III.

Possible significant predictors of the total willingness to pay for vitiligo

| Variable | Total WTPa | |

|---|---|---|

| aORs (95% CI) | p-value | |

| DLQI | 1.008 (0.965–1.053) | 0.731 |

| Education | ||

| Primary school or below | 1 [reference] | NA |

| Middle-school | 2.694 (0.732–9.924) | 0.136 |

| High-school | 2.477 (0.668–9.189) | 0.175 |

| Technical college | 3.452 (0.946–12.579) | 0.061 |

| Bachelor’s degree or above | 4.768 (1.303–17.444) | 0.018 |

| Annual household income (CNY) | ||

| < 80,000 | 1 [reference] | NA |

| 80,000–160,000 | 1.685 (0.974–2.912) | 0.062 |

| 160,000–240,000 | 2.656 (1.344–5.249) | 0.005 |

| 240,000–320,000 | 4.745 (1.477–15.226) | 0.009 |

| > 320,000 | 6.246 (2.421–16.119) | 0.000 |

| Disease duration | ||

| < 6 weeks | 1 [reference] | NA |

| 6 weeks–0.5 year | 2.751 (0.973–7.776) | 0.056 |

| 0.5–1 year | 5.629 (1.990–15.927) | 0.001 |

| 1–3 years | 5.966 (2.079–17.116) | 0.001 |

| 3–5 years | 5.124 (1.502–17.462) | 0.009 |

| > 5 years | 2.416 (0.803–7.272) | 0.117 |

| Four limbs | ||

| Absent | 1 [reference] | NA |

| Present | 2.010 (1.076–3.751) | 0.029 |

| Hands and feet | ||

| Absent | 1 [reference] | NA |

| Present | 1.175 (0.691–1.996) | 0.551 |

| Hair/eyebrows/eyelashes | ||

| Absent | 1 [reference] | NA |

| Present | 2.186 (1.200–3.983) | 0.011 |

| Skin transplantation | ||

| Absent | 1 [reference] | NA |

| Present | 5.894 (2.034–17.064) | 0.001 |

Ordinal logistic regression models were constructed with the total WTP for vitiligo (< 3,000 CNY, < 6,000 CNY, < 10,000 CNY, < 30,000 CNY or > 30,000 CNY) as the ordinal dependent (outcome) variable. The model included the potential confounding variables. The independent (explanatory) variable was DLQI, education, annual household income, disease duration, the site of lesions, and the treatment modality received. There were no significant interactions in the multivariate models.

DLQI: Dermatology Life Quality Index; aOR: adjusted odds ratio; NA: not applicable; WTP: Willingness to Pay.

DISCUSSION

This study presents extensive data on willingness to pay among Chinese patients with vitiligo. In addition to using WTP to evaluate disease burden, this study also examined patient awareness, treatment preferences and their impact on QoL. The mean age of onset was 25.34 years, supporting the fact that nearly 70–80% of patients with vitiligo develop the condition before the age of 30 years, thus enhancing the comparability of the results (4).

Among 244 self-reporting patients with vitiligo, only 11.5% had sufficient knowledge of vitiligo and 44.7% had insufficient knowledge. Misconceptions about the triggers and identification of vitiligo were common, with 17.2% of patients incorrectly identifying vitamin C-rich foods as a cause. Vitamin C has skin-whitening and antioxidant effects, so patients worry that it will aggravate their condition, which is a very common misunderstanding in China. Previous studies have reported similarly low levels of knowledge about vitiligo among the public. Tsadik et al. reported that 31.7% of the 300 Ethiopian participants had insufficient knowledge of vitiligo (16), while, in another study conducted in Thailand, only 30% of participants were able to correctly identify typical white spots as vitiligo (17). The current study investigated the possible reasons and found the primary cause to be residential location, age and education. Patients from rural areas and with lower levels of education had relatively less knowledge of the disease and may lack access to relevant channels for acquiring vitiligo knowledge.

In the current study, patients typically relied on doctors (85.2%) and the internet (61.9%) for information, but almost half (49.6%) hoped to learn more about the disease through medical popularization online platforms. Vitiligo is often overlooked due to patients’ misconceptions about its severity and delayed diagnosis. Gudmundsdottir et al. (18) observed improved disease awareness and treatment adherence in patients with atopic dermatitis after digital interventions. Thus, it is necessary to have appropriate educational programs that provide accurate information in order to prevent delayed treatment or excessive treatment due to unnecessary anxiety (19). Medical practitioners can improve patients’ awareness of vitiligo by strengthening online publicity and authoritative medical popularization online platform .

For vitiligo, the QoL of patients can be assessed using a generalized health-related instrument, such as the short form 36 health survey questionnaire (SF-36), an instrument designed for skin diseases, such as the DLQI and CDLQI, or a vitiligo-specific health-related quality-of-life instrument, such as the VitiQoL (10). As the most commonly used HRQoL instrument, the DLQI is more generalizable and offers the possibility to compare outcomes between different countries or different skin conditions. Our average DLQI score of 5.02 ± 5.25 was higher than the average CDLQI score of 4.21 ± 5.26. Adults and children were affected differently, with adults mainly experiencing difficulties in “work and study” as well as “symptoms and feelings”, while children mainly struggled with “treatment”. This is probably due to the different social environments they live in and the difference in disease perception of the parents of the vitiligo-affected children.

The mean DLQI total score in patients with vitiligo (4.86) in the current study is similar to other published scores in various clinical settings (13, 20). Lewis et al. (21) found higher mean DLQI scores in psoriasis (8.8), acne (11.9), and atopic dermatitis (12.2). Vitiligo has a relatively mild impact on QoL compared with other diseases. Nonetheless, approximately 13.0% of patients still experienced a negative impact on QoL (DLQI > 10) owing to disease-related stress or problems with treatment. Risk factors for limitation of QoL include low level of education, expanded or emerging lesion, vitiligo lesion area of 1–5% of body surface area, and external genitals affected. Our results show that a lower DLQI score indicates less impact on the patient’s QoL and reflects a low burden of disease.

Patients with vitiligo preferred topical drugs, photo-therapy, and systemic drugs over skin transplantation (14.0%), which may be related to the cost of treatments. Although not in the top 3 treatment choices, traditional Chinese medicine was accepted by 32.2% of patients with vitiligo. The combination of Chinese herbs and western medicine may better meet the treatment expectations of patients and improve their compliance. Therefore, physicians should communicate and explain the advantages and disadvantages of other treatment options in the later stages of vitiligo. In recent years, skin grafting has become an effective therapeutic option for stable vitiligo. According to the nature of the grafts, it can be divided into tissue grafting and cellular grafting (22). Tissue grafting, such as suction blister grafting, costs about 100 CNY per square centimetre in China, and is simple to perform, but it is generally suitable for small areas and skin lesions in specific areas (23). In addition, progress has been made in cellular grafting in recent years. Non-cultured epidermal cell suspension (NCES) transplantation, also known as recell technology, may cost approximately 35,000 CNY in China (24), while autologous culture tissue engineering epidermal grafting is more expensive due to its technical difficulty. The high price of cellular grafting and low awareness of surgical treatment among patients limit its clinical application (25).

A significant positive association was noted between the WTP and awareness of vitiligo. Patients with adequate cognition were more willing to pay for treatment. Education level and disease course may potentially influence awareness and increase WTP. However, unlike Radtke et al. (13), no correlation was found between the DLQI and the WTP of patients with vitiligo. Europeans are mostly Caucasian and have a fairer skin type, while the Chinese have a yellowish skin type; hence the skin lesions may be more visible and easier to spot in Chinese patients. These patients are more likely to be diagnosed early and treated to control the condition, which leads to relatively low DLQI. In addition, cultural differences may play an important role.

Potential factors influencing WTP were analysed in this study. It was found that annual household income significantly influenced WTP, which is consistent with the results of previous studies (26). Patients with affected limbs, hair/eyebrows/eyelashes, and a history of skin transplantation also had greater WTP, probably because lesions in these areas are more difficult to treat. However, surveyed patients were conservative about treatment duration and cost, and choosing a more effective treatment option may exceed their expectations.

Study strengths and limitations

All patients were approached continuously from our outpatient department, providing a strong representation of those seen in daily practice. However, there are some limitations to the current study. Firstly, limited literature on awareness and WTP for vitiligo makes it difficult to compare the current findings. Secondly, potential limitations include selection bias, self-reporting bias, and a small sample size; hence the study results should be interpreted with caution.

Conclusion

This study found that inadequate knowledge about vitiligo among patients is associated with a higher burden of disease. Patients have limited understanding of the disease and treatment options. Physicians should improve patient education by explaining the nature and possible course of the disease. Furthermore, combining patient preferences to select treatment regimens may increase adherence and reduce the burden of disease, and improve QoL for individuals with vitiligo.

Supplementary Material

Disease Awareness and Treatment Preferences in Vitiligo: A Cross-sectional Study in China

Disease Awareness and Treatment Preferences in Vitiligo: A Cross-sectional Study in China

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (number 82103704) and Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province (number 2021JJ20089).

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of The Third Xiangya Hospital of Central South University (3 November 2021, number 21132).

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wang X, Du J, Wang T, Zhou C, Shen Y, Ding X, et al. Prevalence and clinical profile of vitiligo in China: a community-based study in six cities. Acta Derm Venereol 2013; 93: 62–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang Y, Li S, Li C. Clinical features, immunopathogenesis, and therapeutic strategies in vitiligo. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol 2021; 61: 299–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Osinubi O, Grainge MJ, Hong L, Ahmed A, Batchelor JM, Grindlay D, et al. The prevalence of psychological comorbidity in people with vitiligo: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Dermatol 2018; 178: 863–878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ezzedine K, Eleftheriadou V, Whitton M, van Geel N. Vitiligo. Lancet 2015; 386: 74–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alikhan A, Felsten LM, Daly M, Petronic-Rosic V. Vitiligo: a comprehensive overview Part I. Introduction, epidemiology, quality of life, diagnosis, differential diagnosis, associations, histopathology, etiology, and work-up. J Am Acad Dermatol 2011; 65: 473–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Do Bú EA, Santos VMD, Lima KS, Pereira CR, Alexandre MES, Bezerra V. Neuroticism, stress, and rumination in anxiety and depression of people with vitiligo: an explanatory model. Acta Psychol (Amst) 2022; 227: 103613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ezzedine K, Eleftheriadou V, Jones H, Bibeau K, Kuo FI, Sturm D, et al. Psychosocial effects of vitiligo: a systematic literature review. Am J Clin Dermatol 2021; 22: 757–774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yip W, Fu H, Chen AT, Zhai T, Jian W, Xu R, et al. 10 years of health-care reform in China: progress and gaps in Universal Health Coverage. Lancet 2019; 394: 1192–1204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sun J, Hu G, Ma J, Chen Y, Wu L, Liu Q, et al. Consumer satisfaction with tertiary healthcare in China: findings from the 2015 China National Patient Survey. Int J Qual Health Care 2017; 29: 213–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang TT, Lee CH, Lan CE. Impact of vitiligo on life quality of patients: assessment of currently available tools. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022; 19: 14943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Motley RJ, Finlay AY. How much disability is caused by acne? Clin Exp Dermatol 1989; 14: 194–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schmitt J, Meurer M, Klon M, Frick KD. Assessment of health state utilities of controlled and uncontrolled psoriasis and atopic eczema: a population-based study. Br J Dermatol 2008; 158: 351–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Radtke MA, Schäfer I, Gajur A, Langenbruch A, Augustin M. Willingness-to-pay and quality of life in patients with vitiligo. Br J Dermatol 2009; 161: 134–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Elbuluk N, Ezzedine K. Quality of life, burden of disease, co-morbidities, and systemic effects in vitiligo patients. Dermatol Clin 2017; 35: 117–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pun J, Randhawa A, Kumar A, Williams V. The impact of vitiligo on quality of life and psychosocial well-being in a Nepalese population. Dermatol Clin 2021; 39: 117–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tsadik AG, Teklemedhin MZ, Mehari Atey T, Gidey MT, Desta DM. Public knowledge and attitudes towards vitiligo: a survey in Mekelle City, Northern Ethiopia. Dermatol Res Pract 2020; 2020: 3495165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Juntongjin P, Abouelsaad S, Sugkraroek S, Taechakraichana N, Lungchukiet P, Nuallaong W. Awareness of vitiligo among multi-ethnic populations. J Cosmet Dermatol 2022; 21: 5922–5930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gudmundsdóttir SL, Ballarini T, Ámundadóttir ML, Mészáros J, Eysteinsdóttir JH, Thorleifsdóttir RH, et al. Clinical efficacy of a digital intervention for patients with atopic dermatitis: a prospective single-center study. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb) 2022; 12: 2601–2611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tsentemeidou A, Sotiriou E, Ioannides D, Vakirlis E. Hidradenitis suppurativa-related expenditure, a call for awareness: systematic review of literature. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges 2022; 20: 1061–1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ongenae K, Van Geel N, De Schepper S, Naeyaert JM. Effect of vitiligo on self-reported health-related quality of life. Br J Dermatol 2005; 152: 1165–1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lewis V, Finlay AY. 10 years experience of the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI). J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc 2004; 9: 169–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ju HJ, Bae JM, Lee RW, Kim SH, Parsad D, Pourang A, et al. Surgical interventions for patients with vitiligo: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Dermatol 2021; 157: 307–316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gao PR, Wang CH, Lin YJ, Huang YH, Chang YC, Chung WH, et al. A comparative study of suction blister epidermal grafting and automated blister epidermal micrograft in stable vitiligo. Sci Rep 2022; 12: 393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mrigpuri S, Razmi TM, Sendhil Kumaran M, Vinay K, Srivastava N, Parsad D. Four compartment method as an efficacious and simplified technique for autologous non-cultured epidermal cell suspension preparation in vitiligo surgery: a randomized, active-controlled study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2019; 33: 185–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhou H, You C, Wang X, Jin R, Wu P, Li Q, et al. The progress and challenges for dermal regeneration in tissue engineering. J Biomed Mater Res A 2017; 105: 1208–1218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Beikert FC, Langenbruch AK, Radtke MA, Augustin M. Willingness to pay and quality of life in patients with rosacea. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2013; 27: 734–738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Disease Awareness and Treatment Preferences in Vitiligo: A Cross-sectional Study in China

Disease Awareness and Treatment Preferences in Vitiligo: A Cross-sectional Study in China