Abstract

Background

This review is an update of a rapid review undertaken in 2020 to identify relevant, feasible and effective communication approaches to promote acceptance, uptake and adherence to physical distancing measures for COVID‐19 prevention and control. The rapid review was published when little was known about transmission, treatment or future vaccination, and when physical distancing measures (isolation, quarantine, contact tracing, crowd avoidance, work and school measures) were the cornerstone of public health responses globally.

This updated review includes more recent evidence to extend what we know about effective pandemic public health communication. This includes considerations of changes needed over time to maintain responsiveness to pandemic transmission waves, the (in)equities and variable needs of groups within communities due to the pandemic, and highlights again the critical role of effective communication as integral to the public health response.

Objectives

To update the evidence on the question 'What are relevant, feasible and effective communication approaches to promote acceptance, uptake and adherence to physical distancing measures for COVID‐19 prevention and control?', our primary focus was communication approaches to promote and support acceptance, uptake and adherence to physical distancing.

Secondary objective: to explore and identify key elements of effective communication for physical distancing measures for different (diverse) populations and groups.

Search methods

We searched MEDLINE, Embase and Cochrane Library databases from inception, with searches for this update including the period 1 January 2020 to 18 August 2021. Systematic review and study repositories and grey literature sources were searched in August 2021 and guidelines identified for the eCOVID19 Recommendations Map were screened (November 2021).

Selection criteria

Guidelines or reviews focusing on communication (information, education, reminders, facilitating decision‐making, skills acquisition, supporting behaviour change, support, involvement in decision‐making) related to physical distancing measures for prevention and/or control of COVID‐19 or selected other diseases (sudden acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS), influenza, Ebola virus disease (EVD) or tuberculosis (TB)) were included. New evidence was added to guidelines, reviews and primary studies included in the 2020 review.

Data collection and analysis

Methods were based on the original rapid review, using methods developed by McMaster University and informed by Cochrane rapid review guidance.

Screening, data extraction, quality assessment and synthesis were conducted by one author and checked by a second author. Synthesis of results was conducted using modified framework analysis, with themes from the original review used as an initial framework.

Main results

This review update includes 68 studies, with 17 guidelines and 20 reviews added to the original 31 studies.

Synthesis identified six major themes, which can be used to inform policy and decision‐making related to planning and implementing communication about a public health emergency and measures to protect the community.

Theme 1: Strengthening public trust and countering misinformation: essential foundations for effective public health communication

Recognising the key role of public trust is essential. Working to build and maintain trust over time underpins the success of public health communications and, therefore, the effectiveness of public health prevention measures.

Theme 2: Two‐way communication: involving communities to improve the dissemination, accessibility and acceptability of information

Two‐way communication (engagement) with the public is needed over the course of a public health emergency: at first, recognition of a health threat (despite uncertainties), and regularly as public health measures are introduced or adjusted. Engagement needs to be embedded at all stages of the response and inform tailoring of communications and implementation of public health measures over time.

Theme 3: Development of and preparation for public communication: target audience, equity and tailoring

Communication and information must be tailored to reach all groups within populations, and explicitly consider existing inequities and the needs of disadvantaged groups, including those who are underserved, vulnerable, from diverse cultural or language groups, or who have lower educational attainment. Awareness that implementing public health measures may magnify existing or emerging inequities is also needed in response planning, enactment and adjustment over time.

Theme 4: Public communication features: content, timing and duration, delivery

Public communication needs to be based on clear, consistent, actionable and timely (up‐to‐date) information about preventive measures, including the benefits (whether for individual, social groupings or wider society), harms (likewise) and rationale for use, and include information about supports available to help follow recommended measures. Communication needs to occur through multiple channels and/or formats to build public trust and reach more of the community.

Theme 5: Supporting behaviour change at individual and population levels

Supporting implementation of public health measures with practical supports and services (e.g. essential supplies, financial support) is critical. Information about available supports must be widely disseminated and well understood. Supports and communication related to them require flexibility and tailoring to explicitly consider community needs, including those of vulnerable groups. Proactively monitoring and countering stigma related to preventive measures (e.g. quarantine) is also necessary to support adherence.

Theme 6: Fostering and sustaining receptiveness and responsiveness to public health communication

Efforts to foster and sustain public receptiveness and responsiveness to public health communication are needed throughout a public health emergency. Trust, acceptance and behaviours change over time, and communication needs to be adaptive and responsive to these changing needs. Ongoing community engagement efforts should inform communication and public health response measures.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice

Evidence highlights the critical role of communication throughout a public health emergency. Like any intervention, communication can be done well or poorly, but the consequences of poor communication during a pandemic may mean the difference between life and death.

The approaches to effective communication identified in this review can be used by policymakers and decision‐makers, working closely with communication teams, to plan, implement and adjust public communications over the course of a public health emergency like the COVID‐19 pandemic.

Implications for research

Despite massive growth in research during the COVID‐19 period, gaps in the evidence persist and require high‐quality, meaningful research. This includes investigating the experiences of people at heightened COVID‐19 risk, and identifying barriers to implementing public communication and protective health measures particular to lower‐ and middle‐income countries, and how to overcome these.

Keywords: Humans, Communication, COVID-19, COVID-19/prevention & control, Pandemics, Pandemics/prevention & control, Physical Distancing, Public Health

Plain language summary

How can we communicate better with people and communities about measures which help to prevent and control COVID‐19?

Key messages

‐ During a pandemic, governments and other authorities need to clearly communicate with the public about how people can keep themselves safe. This communication needs to be based on trust and well‐planned. People and communities affected by the pandemic need to be involved in planning and delivering the communication. The communication should reach all people across the community, including those who have trouble reading and writing, people who speak languages other than the community's dominant language, and people who face other types of disadvantage. Clear communication can improve how well people are able to follow measures to keep themselves safe.

‐ This review identified six themes which can guide best‐practice approaches to public health communication during a pandemic. These themes are:

1) Strengthening public trust and countering misinformation;

2) Two‐way communication involving communities so that people have input into how communication can best happen;

3) Development of and preparation for public communication by considering who the audience is and how different people's needs within the community can be met;

4) Public communication features, including how and when messages are delivered to communities;

5) Supporting behaviour change at individual and population levels;

6) Fostering and sustaining receptiveness and responsiveness to public health communication over time.

‐ The review findings can help governments and other authorities make decisions about public health communication during a pandemic. The findings are relevant to COVID‐19 and future public health emergencies. The findings can be applied across different countries and different emergency situations.

‐ Some gaps in the research were found through this review. These included: communication with people who are at higher risk of getting severely sick or dying from COVID‐19; communication in lower‐ and middle‐income countries; and communication in settings known for social inequalities. Further research in these areas may help increase knowledge and improve practices related to pandemic communication.

What are physical distancing measures?

The term 'physical distancing measures' describes ways to reduce the spread of diseases such as COVID‐19 by reducing physical contact between people. Physical distancing measures include contact tracing, avoiding crowds, isolating, quarantine, and measures to reduce transmission in schools and workplaces.

What did we want to find out?

We wanted to find out which ways of communicating with the public are best to increase people's understanding and use of physical distancing measures to protect themselves and limit the spread of COVID‐19 and other similar diseases. We also wanted to find out whether there were ways of communicating that worked better for certain groups in the community, including people who experience disadvantage.

What did we do?

This review is an update of a review conducted in 2020. The 2020 review included primary studies (qualitative and quantitative) and secondary sources (review studies and guidelines).

During the searches for this update, we looked for guidelines or review studies examining communication about physical distancing measures for preventing and/or controlling COVID‐19 or selected other infectious diseases. We compared and summarised the results of included studies and guidelines, together with the findings from the 2020 review.

What did we find?

This review has 68 included studies (guidelines, reviews and primary studies [studies undertaken by researcher(s) which collect original data]). This update added 17 guidelines and 20 reviews (which are considered secondary research) to the original 2020 review.

We identified six main themes related to planning and implementing communication about physical distancing during a pandemic.

These themes can inform policy and decision‐making around pandemic and public health emergency communication. These themes are: 1) Strengthening public trust and countering misinformation; 2) Two‐way communication; 3) Development of and preparation for public communication; 4) Public communication features; 5) Supporting behaviour change at individual and population levels; 6) Fostering and sustaining receptiveness and responsiveness to public health communication.

What are the limitations of the evidence?

This update focused on reviews and guidelines. Typically, these represent the best available evidence but, in this update, were mainly rated as having low or moderate quality. Because of studies' different designs, the quality ratings are not meant to be used as a hierarchy (ranking) of evidence.

A strength of this review is that major themes and findings came from diverse sources, including primary studies, reviews and guidelines. Often, similar findings were reported across different study types, populations and settings. The findings from this updated review also build on those of the 2020 review, adding to the main findings and filling major gaps. Having similar findings across different study types, and adding new information through this update, increases our confidence in the findings even though most of the included studies are of low or moderate quality. However, since searches for new evidence last occurred in 2021, it is likely that further relevant evidence now exists.

How up‐to‐date is this evidence?

This evidence is up‐to‐date until August 2021.

Background

This review update explores the ways in which communication by governments, health organisations, clinicians and community groups have promoted and supported physical distancing to prevent and control COVID‐19. It provides a comprehensive update to a published rapid review that was commissioned by the WHO European Office in 2020 to answer an urgent question: 'What are relevant, feasible and effective communication approaches to promote acceptance, uptake and adherence to physical distancing measures for COVID‐19 prevention and control?' (Ryan 2021a).

Completed in June 2020 (with evidence current up to 1 May 2020), Ryan 2021a was produced against a backdrop of global uncertainty, fear and confusion. Little was known about transmission, treatment or the potential to vaccinate against the new virus. One of the few certainties was that strict physical distancing measures – isolation, quarantine, contact tracing, crowd avoidance, and work and school measures (Iezadi 2021; WHO 2019) – would form the cornerstone of the public health response to COVID‐19. The need to physically distance to reduce the risk of infectious disease transmission has been known since the earliest civilisations (Vitello 2022) and the need for effective public health communication to underpin these actions has not abated. As the findings of this review attest, the role of effective public health communication in supporting the early and ongoing uptake and adherence to physical distancing measures by billions of people around the world was, and remains, vital. As COVID‐19 remains a public health priority and there has been huge growth in research related to COVID‐19 over recent years, it is important that governments, public health agencies and decision‐makers have access to an updated synthesis of available evidence in order to help inform and guide communications related to the pandemic.

This review update identifies and explores relevant and timely evidence on the complex and multi‐layered task of communicating with diverse and disparate audiences about what is known and unknown, and the steps people need to take to reduce risk and protect public health over the course of a pandemic. In doing so, this review update highlights key information and implications for policy‐makers and governments to consider when planning, implementing and revising how and when to enact physical distancing measures for COVID‐19 control over time. These findings can also inform evidence‐based planning and responsiveness to future pandemics and global health crises. As the evidence confirms, the need for clear and effective public communication remains a constant.

Weighing up the evidence over time: what have we learnt

This review update reinforces the original rapid review findings (Ryan 2021a), which underlined the need for:

Clear, accurate and timely public information and actionable messages that are consistently updated.

Information about risk and what people needed to do to minimise risk both in the immediate and longer terms.

Public information conveying consistent messages expressed in clear and understandable language shared via multiple sources and dissemination pathways.

Accessible information tailored to local contexts to enhance reach, relevance and acceptability and to ensure that the needs of diverse, vulnerable and disadvantaged communities are met.

Community engagement to inform tailoring of messages to groups within populations – ensuring appropriateness to local contexts and using community feedback to improve reach and relevance.

Practical support and access to essential services (e.g. food, medicines, financial support) alongside public information and communication in order to enable people to adhere as closely as possible to physical distancing measures.

The 2020 rapid review drew on rapidly emerging information on COVID‐19 alongside evidence from influenza, SARs, MERs and other infectious outbreaks (Ryan 2021a). Since that time, there has been a deluge of COVID‐19 research. This review update, with evidence current up to 18 August 2021, includes 17 new guidelines and 20 new reviews that, taken together, fill several previous evidence gaps and add to our understanding of communication needs, practices and impacts over the short and longer terms.

Key findings in this current review update that build on the previous findings, centre on the need to:

Build and maintain trust in public agencies, which in turn supports individual and community receptiveness and adherence to ongoing public health communications.

Proactively identify and counter misinformation that continues to sow confusion and mistrust, fuel conspiracy theories and undermine/counter public health communications at local and global levels.

Involve communities at all stages of the pandemic response to improve the dissemination, accessibility and acceptability of communications about preventive public health messages.

Monitor changes in attitudes and behaviours over time that influence individual and community willingness and ability to accept and adhere to physical distancing measures.

Deliver consistent, actionable and coordinated public communications that clearly outline what is known and unknown (acknowledging uncertainty) and is responsive to changes over time.

Address multiple equity issues and challenges to ensure information and communication are tailored for and appropriate to diverse audiences, including hard to reach, vulnerable and marginalised groups (see Appendix 1 for comprehensive list).

Actively work to foster and sustain public receptiveness and responsiveness to public health communication over time.

Focus on equity and community engagement

Equity has emerged as a key theme across the WHO’s COVID‐19 key findings and policy briefings (WHO 2023), the Lancet’s Commission on Lessons for the Future of the COVID pandemic (Sachs 2022), the Cochrane Convenes global evidence summit (Cochrane 2020) and the International Red Cross’s Trust, Equity and Local Action ‐ Lessons from the COVID‐19 pandemic to avert the next global crisis (IFRC 2023). The consensus amongst leading health experts, sociologists and economists is that COVID‐19 increased existing inequalities and created additional urgent policy and healthcare issues in need of redress around the world.

It is clear that inequalities influence the degree to which individuals and populations are able to accept and adhere to preventive measures. Accordingly, the importance of public communication that recognises and is designed to counteract inequalities can’t be overstated. This is critical to supporting community‐level uptake of physical distancing measures – particularly as the effects of the pandemic disproportionately affect the poorest and most vulnerable.

In recognition of this, this review update identifies key elements of effective communication for physical distancing measures for diverse populations and groups, and applies a more consistent equity lens across the evidence. It highlights the role of community involvement, feedback and interactive engagement to inform and refine communication approaches, content and delivery over time. It is essential that information, as well as practical supports, are tailored to meet the specific needs of diverse communities, particularly underserved, vulnerable and disadvantaged groups.

Navigating pandemic fatigue and looking ahead: why this review is important

Communicating clearly with people and populations about why physical distancing measures are needed and how they can adhere to them has been a critical and consistently challenging component of COVID‐19 prevention and control globally. This updated review addresses this identified need for further understanding of effective public health communication approaches. Three years into the pandemic, people’s lives, livelihoods and forbearance have been tested beyond measure. Pandemic fatigue has set in, bringing a fresh set of challenges for effective public health communication.

Late in 2022, WHO Director Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus and US President Joe Biden made respective statements that the end of COVID‐19 was in sight (United Nations 2022) and that the pandemic was now over (Berger 2022). In part, these declarations reflected less about actual case numbers and mortality rates and more about the political, economic and social status quo. It is increasingly clear that people, communities and governments across the globe collectively yearn to put COVID‐19 – and the immeasurable losses from illness, isolation, closures and lost opportunities that come with it – firmly out of sight and out of mind.

Universal COVID‐19 fatigue makes the task of public health communication ever more challenging, but no less critical. The evidence in this rapid review update has direct implications for policy‐makers and governments to consider when planning, implementing and revising physical distancing measures for COVID‐19 control over time, and in the real‐world conditions we now find ourselves in. The findings may also have relevance in helping to inform and guide policy‐makers and others when planning communications in relation to future disease outbreaks and public health emergencies.

It adds another important piece to the emerging picture of what worked and what did not in preventing the spread of COVID‐19. The evidence on the role of public health communication in the pages that follow can inform our thinking on critical issues beyond physical distancing measures. It can also shape our response to the ongoing challenges of COVID‐19, and our preparedness for the future global health challenges that lie ahead.

Objectives

This review update builds on the existing rapid review commissioned by WHO to address the question: 'What are relevant, feasible and effective communication approaches to promote acceptance, uptake and adherence to physical distancing measures for COVID‐19 prevention and control?'

Therefore, the primary focus of this review update is communication approaches to promote and support acceptance, uptake and adherence to physical distancing – and not the effects of physical distancing per se.

A secondary objective, introduced in this updated version, is to explore and identify key elements of effective communication for physical distancing measures for different (diverse) populations and groups. This included, where appropriate, differential consideration or analysis of countries according to income levels (e.g. upper and middle income compared with others); or of target groups within populations (e.g. lower socioeconomic status, lower health literacy), underserved groups (e.g. people experiencing homelessness), culturally and ethnically diverse groups (e.g. migrants and refugees), specific age and demographic groups; and included consideration of the prevalence of COVID‐19 within populations over time (e.g. communication during peak times (surge/wave) versus that during lower prevalence periods).

Methods

The original rapid review (Ryan 2021a) and this updated review used methods based closely on rapid response methods developed and used by McMaster University (Wilson 2018) and informed by Cochrane rapid review methods guidance (Garritty 2021; Tricco 2020).

A protocol was developed and made publicly available before the updating process began (Ryan 2021b). Please refer to this for detailed methods, a brief summary of which is provided here. Any changes to the methods from those described in the protocol are noted.

Please also see Table 1 for a list of abbreviations used throughout the review.

1. Abbreviations used in this update.

| AGREE II: Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation II tool AMSTAR: A Measurement Tool to Assess Systematic Reviews BAME: Black, Asian and minority ethnic CASP: Critical Appraisal Skills Programme CCM: child contact management CDC: Centres for Disease Control and Prevention CHW: community health worker COI: conflict of interest CT: contact tracing ECE: early care and education ECDC: European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control EEA: European Economic Area ERC: emergency risk communication EU: European Union EVD: Ebola virus disease FAQ: frequently asked questions FTTIS: find, test, trace, isolate, support GL: guideline GOARN: Global Outbreak Alert and Response Network GPS: global positioning system H1N1: H1N1 influenza strain HCW: health care worker HIV: Human Immunodeficiency Virus IFRC: Internation Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies IHE: institute of higher education LMIC: lower‐ and middle‐ income country MERS: Middle Eastern respiratory syndrome N/A: not applicable NGO: non‐goverment organisation NICE: National Institute for Clinical Excellence NIHR: National Institute for Health Research NPI: non‐pharmaceutical intervention OECD: Organisation for Economic Co‐operation and Development PD: physical distancing PH: public health PHAC: Public Health Agency Canada PHM: public health measures PHSM: public health and social measures PPE: personal protective equipment PTSD: post‐traumatic stress disorder QES: qualitative evidence synthesis QR: quick response RCCE: risk communication and community engagement RCT: randomised controlled trial SAGE: Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies SARS: Sudden acute respiratory syndrome SES: socioeconomic status SIM: subscriber identity module SMS: short message/ messaging service SPI‐B: Scientific Pandemic Influenza Group on Behaviours SR: systematic review TB: tuberculosis THL: Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare UAE: United Arab Emirates UNICEF: United Nations International Children's Emergency Fund WHO: World Health Organization |

Eligibility criteria for this review update

Types of study design

We had planned to consider eligible studies in two phases (refer to Appendix 2 for details):

Phase 1 (synthesised evidence sources; focusing on COVID‐19, SARS, MERS, influenza, Ebola (EVD), or TB): guidelines (country‐specific, global or regional), systematic reviews (intervention reviews, qualitative syntheses, mixed‐methods reviews).

Phase 2 (primary studies; focusing on COVID‐19 only): single studies on COVID‐19 if there were gaps in the evidence derived from guidelines or reviews (i.e. primary studies that provided new knowledge not found in identified synthesised evidence sources), including observational studies, controlled trials, qualitative studies (any empirical method (i.e. based on observation or measurement of phenomena)), mixed‐methods research.

At the screening stage, we identified a large volume of synthesised evidence (i.e. guidelines, systematic reviews) eligible for inclusion. We, therefore, decided to stop screening at Phase 1 and formulate this update as an overview of synthesised evidence sources.

Population and context

Consistent with the original rapid review (Ryan 2021a), studies focussing on physical distancing measures for prevention and/or control of COVID‐19 or other selected infectious diseases (SARS, MERS, influenza, EBV or TB) were included. We focused on communication to promote physical distancing measures outside healthcare settings, i.e. measures put in place in community settings, including workplaces and schools. All countries were eligible, irrespective of income level or geographic location.

Types of intervention

To be included, studies must have focused on the intersection between communication and physical distancing measures. Communication with individuals, organisations, communities and/or systems was included.

Physical distancing measures (contact tracing, isolation, quarantine, crowd avoidance, school and work measures) were defined based on WHO definitions for pandemic influenza control (WHO 2019); see Table 2 for definitions.

2. Definitions of physical distancing measures considered by this review update.

| Contact tracing | The identification and follow‐up of persons who may have come into contact with an infected person, usually in combination with quarantine of identified contacts. |

| Crowd avoidance | Measures to reduce virus transmission in crowded areas/mass gatherings, including restrictions on gatherings, and approaches for individual distancing in homes, shops, workplaces, public transport and public places. |

| Isolation | Reduction in virus transmission from an ill person to others by confining symptomatic individuals for a defined period either in a special facility or at home. |

| Quarantine | Isolation of individuals who contacted a person with proven or suspected viral illness, or travel history to an affected area, for a defined period after last exposure, with the aim of monitoring them for symptoms and ensuring the early detection of cases. |

| School measures | Closure of schools when virus transmission is observed either in the school or community, or an early planned closure of schools before virus transmission initiates. |

| Work measures, including closures | Measures to reduce virus transmission in the workplace, or on the way to and from work, by decreasing the frequency and length of social interactions. May include closure of workplaces when virus transmission is observed in the workplace, or an early planned closure of workplaces before virus transmission initiates. |

Definitions of physical distancing measures taken from WHO 2019

Communication in the context of physical distancing was defined as that undertaken for one or more of the following purposes (Hill 2011; Kaufman 2017; Ryan 2014):

Information/education.

Reminding.

Facilitating communication or decision‐making.

Enabling communication.

Acquiring skills.

Supporting behaviour change.

Being supported.

Involving the community in decision‐making for the promotion of physical distancing.

The following were excluded:

Methods of enhancing community ownership of non‐pharmaceutical intervention (NPI) measures.

Personal support (e.g. individual psychosocial support).

Strategies for minimising risks/harms to individuals/communities, without a focus on communication of physical distancing measures (e.g. informing individuals about the importance of ‘flu' vaccination in the context of the COVID‐19 pandemic).

Implementation and/or effects of physical distancing measures, without an identifiable communication element (e.g. effectiveness of physical distancing measures themselves).

Modelling of effectiveness scenarios (e.g. effectiveness of quarantine at preventing viral transmission).

Mobile/digital health applications without an explicit focus on physical distancing measures and related communication.

Knowledge of pandemic risks and/or risk perceptions without a focus on physical distancing measures.

Public/consumer information materials on physical distancing.

Types of outcome(s)

We sought qualitative and quantitative data on outcomes for individuals and communities, broadly aligned with the following major categories:

Acceptance;

Uptake;

Adherence;

Feasibility and related outcomes.

Studies were not excluded based on outcomes sought or outcome measures reported.

Search methods for identification of studies

An Information Specialist (AP) designed and ran all searches, which were informed by a content expert, independently peer reviewed and updated from the original 2020 search methods designed to identify all relevant physical distancing measures. Previous keyword choices had been peer‐reviewed by Robin Featherstone (then Information Specialist, Cochrane Evidence Production & Methods Directorate) and Andrew Booth (University of Sheffield).

Electronic databases

For the original rapid review (Ryan 2021a), we searched electronic databases from inception to 1 May 2020. For this review update, we searched the MEDLINE, Embase and the Cochrane Library databases from 1 January 2020 to 18 August 2021:

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2021, Issue 8), in the Cochrane Library (Appendix 3);

Embase Classic (1947 to 2021 week 33) (Appendix 4); and

MEDLINE via Ovid (1946 to 18 August, 2021) (Appendix 5).

Please refer to Table 3 for all search details.

3. Search activities and dates.

| Database | Date searched |

| CAMARADES COVID‐19 SOLES | 24 Aug 2021 |

| CDC | 24 Aug 2021 |

| Cochrane Library | 18 Aug 2021 |

| Cochrane study Registry COVID‐19 | 24 Aug 2021 |

| ECDC | 24 Aug 2021 |

| Embase Classic + Embase 1947 to 2021 August 18 | 18 Aug 2021 |

| Epistemonikos COVID‐19 | 25 Aug 2021 |

| Google Scholar | 18 – 25 Aug 2021 |

| Health Systems Evidence | 25 Aug 2021 |

| Lit COVID | 25 Aug 2021 |

| Ovid MEDLINE(R) ALL 1946 to August 19, 2021 | 18 Aug 2021 |

| MedRixv | 31 Aug 2021 |

| NICE | 25 Aug 2021 |

| PDQ Evidence | 25 Aug 2021 |

| PubMed | 24 Aug 2021 |

| WHO Global research on COVID‐19 | 31 Aug 2021 |

| Web of Science (citing references) | 1 Sep 2021 |

All records were downloaded to an Endnote library. Duplicates from the previous publication’s search (Ryan 2021a) were removed from the database records. As when undertaking the original review, the Cumulated Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) and PsycINFO were assessed before the searches were conducted. Both were judged as not having sufficiently unique references and, so again, were not searched in this update.

Guidelines

The eCOVID19 Recommendations Map (https://covid19.recmap.org/; eCOVID‐19 RecMap) team supplied us with spreadsheets of all the organisational guidelines screened for the COVID‐19 Living Catalogue of Guidelines in November 2021.

Other searches

Reference lists of key studies were searched, together with searches for citing articles about key studies. Key informants were also consulted for additional sources of relevant evidence.

For studies available but not yet peer‐reviewed (e.g. MedRivx), the lack of peer review was noted in the quality assessment. For pre‐prints included in the original review, we checked the publication status and verified the data extracted against any subsequently published peer‐reviewed articles.

We also searched a range of online databases and grey literature (see Table 3). Relevant keywords were chosen for each of the websites. Full search terms and strategies for the online databases and grey literature are available from the authors upon request.

At the time of publication, approximately 24 months had elapsed since running searches for this update. We did not update the searches to identify more recently available evidence as it was beyond our resourcing to do so. This high‐level synthesis draws on a very large volume and range of literature related to COVID‐19 as well as other selected diseases, with the purpose of informing current public health communications and future pandemic preparedness planning. The methods and approach adopted are therefore different to usual Cochrane review methods but tailored to providing a rigorous review of evidence for decision‐makers.

Screening

Decision rules operationalising the selection criteria were developed and refined iteratively by two review authors (RR, CS). One author (RR) screened all titles and abstracts for eligibility. All records identified as potentially relevant were retrieved for full‐text assessment. A second reviewer (CdMM) independently checked 20% of excluded records.

Two review authors (RR, CS) screened all full‐text articles, with discrepancies resolved by discussion to reach consensus.

We handsearched the list of guidelines from eCOVID‐19 RecMap. One author (RR) screened titles, and two authors (RR, CS) screened full‐text copies of all potentially‐relevant guidelines to determine eligibility.

Studies excluded at the full‐text screening phase for this update are reported in Characteristics of excluded studies, with reasons for exclusion. Full‐text studies excluded from the original review are available at opal.latrobe.edu.au/articles/dataset/Studies_excluded_from_Ryan_et_al_2021/20436261.

We did not exclude studies based on the language of the publication. All potentially eligible non‐English language abstracts progressed to full‐text assessment, and methods were translated to determine eligibility, where possible.

As part of Phase 1 screening, included guidelines and reviews were mapped systematically against major themes identified in the original review by a single reviewer (RR) and checked by a second reviewer (CS, BM, CdMM, LS). All six themes were well‐populated with evidence, and major gaps that had been identified in the original review were addressed by the addition of more recent evidence (school and work measures; measures for vulnerable populations including those at heightened risk of severe disease; communications related to alterations of public health measures). Accordingly, screening was halted at Phase 1, and primary studies were not considered further in the review.

Inclusion of ongoing or unpublished studies

We assessed studies identified as pre‐prints in the original rapid review, identifying one (Atchison 2020, cited April 3, 2020) subsequently published in 2021. The published and pre‐print versions were cross‐checked, and while several small changes were identified in the 2021 publication, none affected data extracted from the pre‐print version.

Data collection and analysis

Data extraction and quality assessment

Data were extracted from included studies by one author (RR) and verified by a second author (CS, BM, CdM, LS), including quality assessments. Included studies were appraised using established tools (for guidelines, AGREE II (Brouwers 2010); for systematic reviews, AMSTAR (original tool) (Shea 2007)). Where available from reliable databases, quality ratings were extracted directly, with acknowledgement of the assessment source.

For studies identified from handsearching of eCOVID‐19 RecMap, the eCOVID‐19 Rec Map Critical Appraisal Team critically appraised eligible guidelines independently in duplicate using the AGREE‐II tool. Inter‐rater item differences of 3 points or greater were flagged as a conflict. All conflicts were resolved through discussion with the help of the critical appraisal coordinator, as needed.

We did not contact the study authors to request more information related to missing data. In the protocol, we noted that any such efforts would concentrate on primary research studies (Ryan 2021b). Given that our methods for selecting studies changed during the review, this step was no longer a priority. We did, however, contact authors of forthcoming reviews (protocols) that were judged as eligible for inclusion. We requested access to the review (if completed) and/or information about the likely timing of the full review becoming available.

Review Manager (RevMan) was used to collate and report all elements of the review using a flexible review format. Data tables, once verified, were added to RevMan directly as Appendix 6. Other review information and data was entered into RevMan by one reviewer (RR) and checked for accuracy by a second reviewer (AV, CS).

Data synthesis

Data were systematically extracted and tabulated in the first instance to transparently and consistently present key features and findings of the included evidence, including quality assessments, in a structured way (Campbell 2020). Data were extracted, and findings mapped to each component of the review question (e.g. acceptance, adherence). There was then a second translational step to identify the communication purpose and how this might affect interpretation of the study findings (Campbell 2020).

For the original review, included studies were mapped to each component of the review question and grouped for analysis. In the analysis, we considered population features, intervention characteristics (i.e. characteristics of the communication intervention or issue), and contextual factors or implementation issues. Data were standardised by identifying major thematic categories. We used modified framework analysis (Ritchie 1994) for analysing data in the original review, informed by methods described in Tricco 2017 (primarily Chapter 4). Findings from both qualitative and quantitative research were analysed concurrently, and six themes were identified (see Appendix 7).

These themes provided the guiding framework for synthesising newly identified evidence in this update, allowing for new categories to emerge through the analysis.

The quality of studies informing each section of findings was systematically assembled and presented alongside the thematic findings in all cases. We also identified and discussed any limitations of the assembled evidence and potential biases in the review process.

At the protocol stage (Ryan 2021b), we planned to investigate and identify key elements of effective communication for physical distancing measures for different (diverse) populations and groups. Data on these features (e.g. income levels, population features such as socioeconomic status) were collected and systematically assembled and used to inform the development of themes (e.g. identification of findings related to particular groups at a disadvantage and/or who may require specific consideration related to communication, such as migrants and refugees). We also sought to identify communication approaches targeting individual members of the public and report these separately from community‐level (public health) communication.

At each stage of synthesis (identifying major thematic categories and subcategories of data, analysing the findings and considering other factors such as intervention and population features), we developed clear decision rules to ensure consistency across the author team. Training and support were provided by the original author team members.

A single reviewer (RR), with work checked by a second reviewer (CS, AV), undertook each synthesis step. At least one senior member of the original author team (RR, SH) was involved in the oversight or conduct of the review at all stages of synthesis (for all data) to ensure consistency and accuracy of the data and analyses. In addition, members of the review team provided key input at critical points of the synthesis. For example, input from co‐authors was sought upon preliminary development of the themes for this update. Co‐authors' feedback critically shaped the scope and language of themes and subthemes as well as the structure and order of the findings.

We planned to explore the possibility of quantitative outcomes for statistical analyses. However, none were identified in the data for this update.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

Searches of databases and grey literature sources identified 6845 records after deduplication. Screening of titles and abstracts identified 1517 records for full‐text screening. At this stage, the decision was taken to include only synthesised evidence sources (reviews and guidelines) in this review update. As a result, 1355 primary studies were excluded from the full‐text assessment. A total of 162 records were identified as systematic reviews or guidelines for full‐text screening.

Screening of a further 412 records in eCOVID19 RecMap identified 151 guidelines for full‐text assessment.

In total, 313 (162 + 151) reviews and guidelines were assessed for eligibility in full text. Of these, 267 were excluded. Seven studies are outstanding (5 awaiting classification, 2 awaiting translation), with two ongoing at the time of searching and screening; see Figure 1.

1.

PRISMA flow diagram to illustrate our study selection process for this update

The current review update includes 68 studies. Of these, 31 were from the original rapid review (Ryan 2021a). We added 37 new studies (17 guidelines and 20 reviews) in this updated version. One included review was empty (Moya‐Salazar 2021) and so is not reported further.

Of the reviews included, five (1 from the original review (Eaton 2020) and 4 newly included (Berg 2021; Majid 2020; Mobasseri 2020; Noone 2021)) were scoping, rather than systematic, reviews. These were included as it was judged that they contributed relevant, important evidence, for instance, communication issues related to unique population groups (older people Mobasseri 2020), health authorities' considerations of modes for pandemic communication with the public (Berg 2021), or identification of determinants of physical distancing behaviour uptake and adherence related to communication about these measures (e.g. beliefs, knowledge, skills) (Lunn 2020).

Included studies are summarised in data tables (see Appendix 6), reporting all relevant information for each of the included studies as an updated map of evidence addressing the review objectives previously presented in Ryan 2021a. Each study's data table presents the following information:

Study characteristics.

Study findings.

Results of quality assessment.

Mapping and translational steps. These were undertaken as part of the synthesis of results and represent intermediate steps, translating the study findings to communication purpose and the review's objectives.

Disease context

The original rapid review included 31 studies conducted during the COVID‐19 era and those on selected infectious diseases (influenza, SARS, MERS, EBV and TB). All the 17 primary studies (12 cross‐sectional surveys, one randomised controlled trial (RCT), one cohort study and three qualitative studies) focused on COVID‐19. For the 14 systematic reviews and guidelines, synthesised evidence was based on studies of pandemic influenza, particularly related to the 2009 H1N1 pandemic influenza outbreak (n = 7), EVD (2), SARS (2), TB (2) and MERS (1).

Of the 37 systematic reviews and guidelines added to this review update, 31 focussed on COVID‐19; the remaining six drew on research that was not COVID‐19‐specific, but the research was explicitly conducted in the context of the current pandemic outbreak.

Geographic location and income level

Geographically, included studies were spread across the world and from all continents. For details, please refer to Appendix 6.

However, most included studies (48/68) were drawn either exclusively or predominately from high‐income countries (according to World Bank classifications), with only nine from low‐ and middle‐income countries. Of these, several focused on EVD (largely from countries in West Africa; Congo, Guinea, Liberia, Senegal and Sierra Leone) or TB (including Ethiopia, India, Indonesia, Malawi, South Africa, Peru and selected higher‐income countries). Several guidelines and reviews (n = 10) included evidence drawn from several countries across income brackets, and many sought studies or evidence from a range of countries.

Target of communications

In the original review, much of the evidence was directed at the population level and focused on public pandemic risk messaging, including information to the public or specific groups within populations to promote physical distancing measures.

In this update, we again planned to attempt to identify communication approaches targeting individual members of the public and report these separately from community‐level (public health) communication. However, most included studies again dealt with general, community‐level communication (approximately three quarters; 72%). We did find, however, that in newly identified studies, a number (10 guidelines and reviews) focused on communication with specific vulnerable groups. Three guidelines specifically focused on vulnerable groups (ECDC 2020a; ECDC 2020b; WHO 2021), while other guidelines and reviews included a general population scope but specifically identified vulnerable groups within this (PHAC 2021; PHAC 2022; Sopory 2021); or focused on one or more groups requiring tailored communication (e.g. non‐English speaking groups and EVD survivors (Gilmore 2020), vulnerable groups (Cardwell 2021), older adults and/or those with comorbidity or of lower socioeconomic status (Mobasseri 2020; Regmi 2021)). Themes in the data relating specifically to vulnerable groups were identified in our analysis.

In the protocol (Ryan 2021b), we planned to investigate and identify key elements of effective communication for diverse populations and groups, including countries according to income level; target groups within populations (such as those based on socioeconomic levels); health literacy; hard(er)‐to‐reach groups; culturally, linguistically and ethnically diverse groups; and any other relevant features, such as age. We also aimed to identify populations defined by COVID‐19 prevalence over time (e.g. communication during peak times (surge/wave) versus that during lower prevalence periods).

We extracted all such information where available, and identified these groups and information relevant for shifting public health measures in the presence of changing COVID‐19 levels within communities in our analysis. Findings related to these groups were identified naturally in the data. Findings related to specific groups and changing requirements of public health communication over time are reflected throughout the thematic results.

Excluded studies

Studies excluded based on title and abstract screening were checked by a second reviewer: of the 4918 studies excluded at the preliminary screening stage, 984 (20%) were checked by a second reviewer. In total, 10 studies were queried, and half (5) were re‐included in the group of primary studies to be assessed in full text as phase 2 citations (no longer considered eligible for inclusion in this update). These checks indicated a high level of agreement between reviewers about selection decisions, and that potentially‐relevant studies were unlikely to have been mistakenly excluded by a single reviewer conducting title and abstract screening.

Studies excluded at the full‐text screening stage are reported with reasons in Characteristics of excluded studies. Studies were more often excluded because they lacked an identifiable focus on communication; had insufficient intersection between communication and physical distancing measures; focused on clinical/infection control; or were set primarily in health systems or services (non‐community settings).

Studies screened in full text and excluded from the original review are not reported here but are available at: https://opal.latrobe.edu.au/articles/dataset/Studies_excluded_from_Ryan_et_al_2021/20436261.

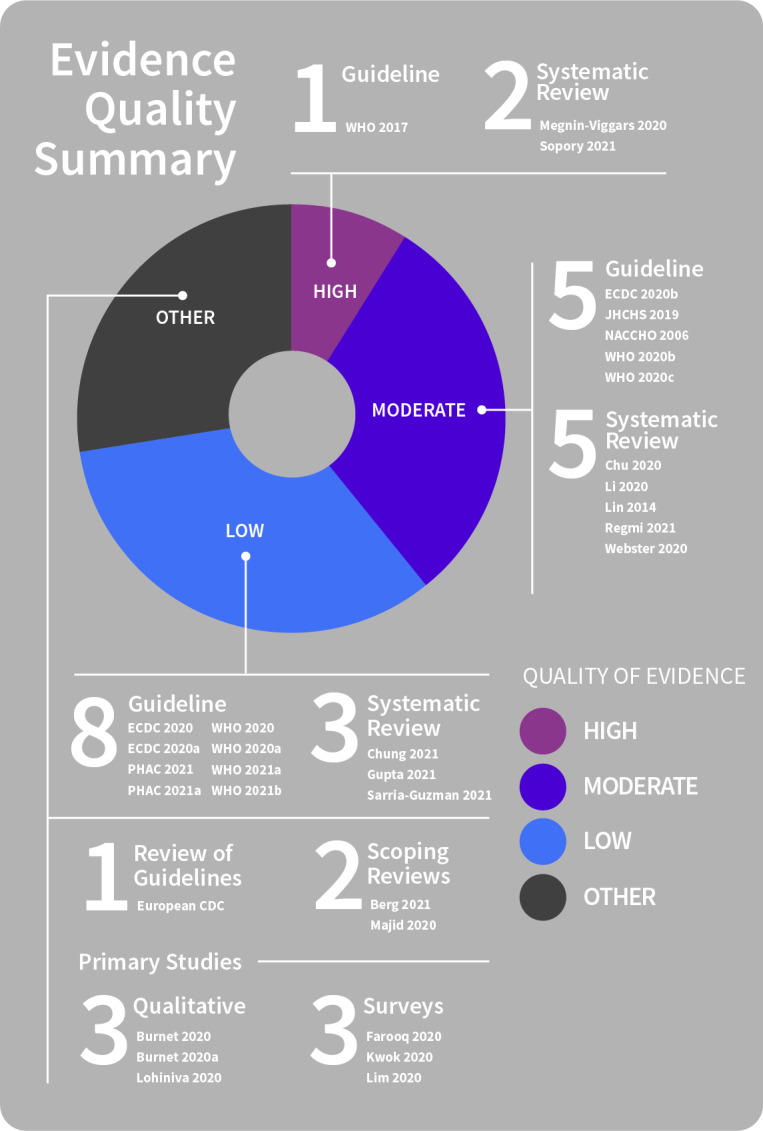

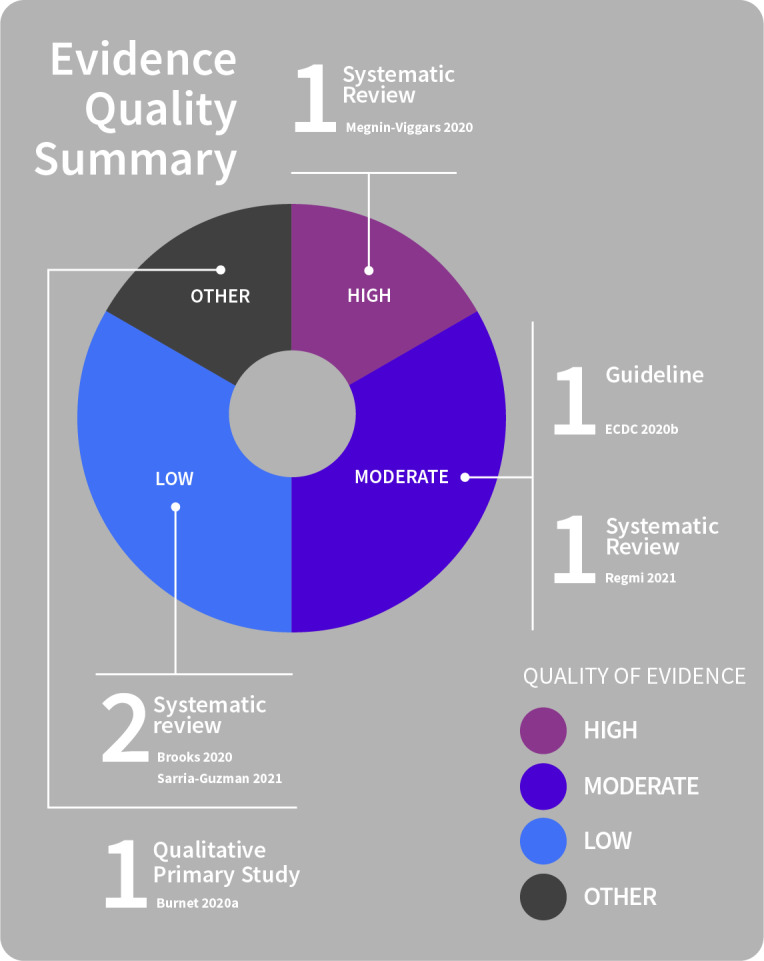

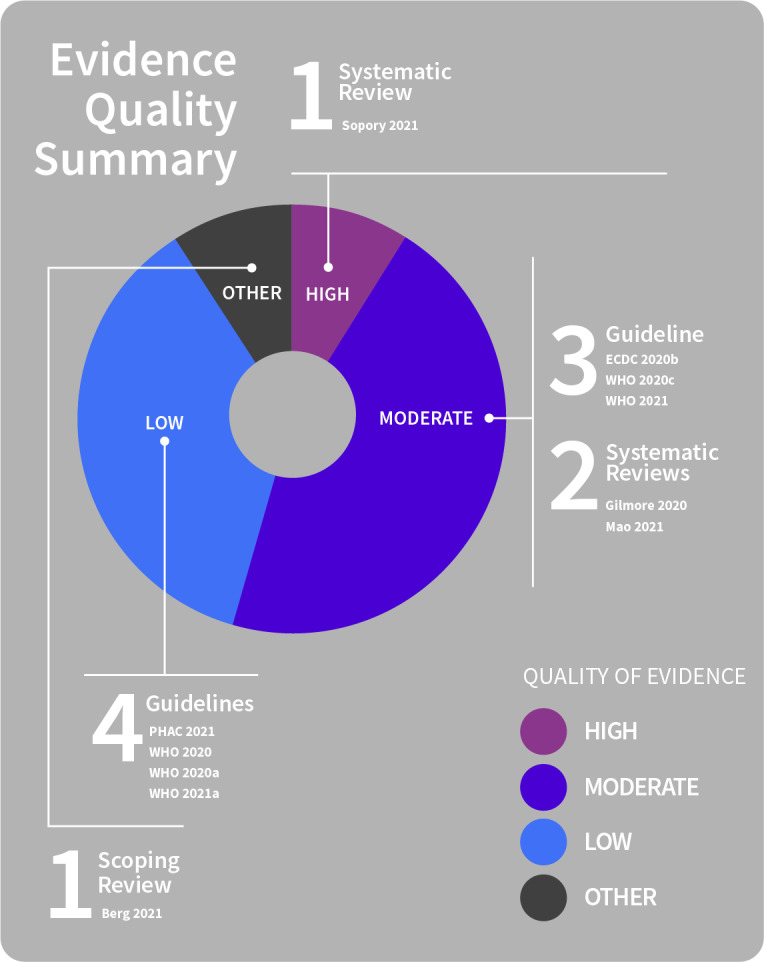

Quality of included studies

An overview of the quality ratings of included studies (original review and this update) is provided in Table 4, with a more detailed breakdown of ratings provided in Table 5. A detailed quality assessment can be found for each study within the data tables provided in Appendix 6. We report quality assessments of studies contributing data to each theme and subtheme in the results, to convey an indication of the volume, type and quality of the evidence underpinning all findings. However, the quality assessments are not intended to be used as a hierarchy of evidence, as this was neither possible nor appropriate with the mix of included research (i.e. qualitative and quantitative, primary and synthesised evidence sources). Rather, this information on quality is provided with the aim of informing interpretation and implementation of the findings.

4. Overview of included studies and quality ratings (original review and this update).

| Guidelines | Systematic reviews | Primary studies | |

| Original review (Ryan 2021a) | 3 | 11 | 17 |

| Cochrane update | 17 | 20* | 0 |

| Total included | 20 Quality (AGREE II):

|

31* Quality (AMSTAR):

|

17 Quality (design‐specific tools):

|

* One included review was empty (Moya‐Salazar 2021) and was therefore not assessed for quality or considered further in this update.

AMSTAR ratings categorised as follows (scored out of 11): 1‐4 low, 5‐7 moderate, 8+ high‐quality

AGREE II ratings categorised as follows (mean scores across 6 domains): < 40% low, 40 to < 70% moderate, 70%+ high‐quality

5. Included studies and ratings of methodological quality.

| Physical distancing measure | Study ID (type of study) | Quality, assessment tool |

| Contact tracing | Chung 2021(SR)# | Low, AMSTAR |

| Gilmore 2020(SR)#^ | Moderate, AMSTAR | |

| Heuvelings 2018 (SR)* | Moderate, AMSTAR | |

| Khorram‐Manesh 2021(SR)# | Moderate, AMSTAR | |

| Megnin‐Viggars 2020(SR)# | High, AMSTAR | |

| Saurabh 2017 (SR)* | Low, AMSTAR | |

| Szkwarko 2017 (SR)* | Moderate, AMSTAR | |

| Bodas 2020 (survey)# | Low‐moderate | |

| Isolation | WHO 2021(GL)# | Moderate, AGREE II |

| Cardwell 2021(SR)#^ | Moderate, AMSTAR | |

| Chu 2020(SR)#^ | Moderate, AMSTAR | |

| ECDC 2020b(GL)# | Moderate&, AGREE II | |

| ECDC 2020a(GL)# | Low, AGREE II | |

| Mao 2021(SR)# | Moderate, AMSTAR | |

| Mobasseri 2020(scoping review)# | Low, AMSTAR | |

| Regmi 2021(SR)# | Moderate, AMSTAR | |

| Seale 2020(SR)# | Low, AMSTAR | |

| WHO 2020c(GL)# | Moderate, AGREE II | |

| Burnet 2020 (qualitative)# | Moderate, CASP | |

| Burnet 2020a (qualitative)# | Moderate, CASP | |

| Farooq 2020 (survey)# | Low | |

| Qazi 2020 (survey)# | Low | |

| Quarantine | Brooks 2020 (SR)*^ | Low%, AMSTAR |

| Gomez‐Duran 2020(SR)#^ | Moderate, AMSTAR | |

| Lin 2014 (SR)* | Moderate, AMSTAR | |

| Sopory 2021(qualitative, SR)#^ | High, AMSTAR | |

| Webster 2020 (SR)#^ | Moderate, AMSTAR | |

| WHO 2021b(GL)# | Low, AGREE II | |

| Zhu 2020 (survey)# | Moderate | |

| School measures | Brooks 2020a (SR)*^ | Low%, AMSTAR |

| CDC 2022(GL)# | Low, AGREE II | |

| CDC 2022a(GL)# | Low, AGREE II | |

| CDC 2022b(GL)# | Low, AGREE II | |

| DES 2020(GL)# | Low, AGREE II | |

| Work measures | ‐ | ‐ |

| Crowd avoidance, including individual physical distancing measures | ECDC 2020(GL)# | Low, AGREE II |

| NACCHO 2006 (guideline)+* | Moderate, AGREE II | |

| PHAC 2021(GL)# | Low, AGREE II | |

| PHAC 2021a(GL)# | Low, AGREE II | |

| Teasdale 2014 (SR, qualitative)* | Moderate, AMSTAR | |

| Tooher 2013 (SR)* | High, AMSTAR | |

| WHO 2020b(GL)# | Moderate, AGREE II | |

| Eaton 2020 (scoping review)*^ | Low, AMSTAR | |

| Lor 2016 (qualitative)* | Moderate, CASP | |

| Atchison 2020 (survey)# | Moderate | |

| Briscese 2020 (survey)# | Moderate | |

| Clements 2020 (survey)# | Low | |

| Kwok 2020 (survey)# | Low‐moderate | |

| Lohiniva 2020 (qualitative)# | Moderate, CASP | |

| Lunn 2020 (RCT)# | Moderate, CASP | |

| Meier 2020 (survey)# | Low‐moderate | |

| Roy 2020 (survey)# | Low | |

| Zhong 2020 (survey)# | Low | |

| General | Bekele 2020(SR)# | Moderate, AMSTAR |

| Berg 2021(scoping review, rapid)# | Low, AMSTAR | |

| ECDC 2020g (review of guidelines)# | Low, AMSTAR | |

| Gupta 2021(SR)# | Low, AMSTAR | |

| JHCHS 2019 (guideline)* | Moderate, AGREE II | |

| Li 2020(SR)# | Moderate, AMSTAR | |

| Majid 2020(scoping review) #^ | Low, AMSTAR | |

| Noone 2021(scoping review, rapid)# | High, AMSTAR | |

| PHAC 2022(GL)# | Low, AGREE II | |

| Sarria‐Guzman 2021(SR)# | Low, AMSTAR | |

| WHO 2017 (guideline)* | High, AGREE II | |

| WHO 2020(GL)# | Low, AGREE II | |

| WHO 2020a(GL)# | Low, AGREE II | |

| WHO 2021a(GL)# | Low, AGREE II | |

| Lim 2020 (survey)# | Moderate |

# COVID‐19‐specific, #^ included research not COVID‐19‐specific but review conducted explicitly in the context of the current pandemic outbreak, *non‐COVID‐19‐specific study

Bold text indicates new studies added in this update.

AMSTAR ratings categorised as follows (scored out of 11): 1‐4 low, 5‐7 moderate, 8+ high‐quality

AGREE II ratings categorised as follows (mean scores across 6 domains): < 40% low, 40 to < 70% moderate, 70%+ high‐quality

&AGREE II overall rating calculated based on mean of 3 domains (1, 3, 6) rather than all 6 domains of the tool

% AMSTAR rating from McMaster Health Forum (via Health Systems Evidence https://www.healthsystemsevidence.org)

The quality of the included studies varied. Half (34/68) of all included studies were rated as of high or moderate quality based on the tools applied. This means that shortcomings in the design and/or conduct of many included studies are present and that findings should be interpreted with recognition that limitations in the assembled research exist.

Results of the synthesis

Themes identified in the framework analysis

From the synthesis of the data, six major themes emerged. These were derived from the six themes originally identified by Ryan 2021a that served as a guiding framework for the synthesis (Appendix 7), but were substantially adapted on the basis of newly included evidence and based on feedback by the wider author team. The ordering of the themes was also modified based on decisions by the team after considering the themes and subthemes emerging from preliminary analysis.

Evidence assembled in this update addressed a number of key knowledge gaps identified in the original review and added significantly to the findings in several key areas. This included the need for ongoing communication over time during a pandemic, particularly to reflect changes to risk and to public health measures; the requirements for tailoring and flexibility of public information and communication; the need to explicitly and carefully consider the needs of vulnerable groups within communities; and the need for systems to support the critical role of community engagement in mounting an effective public health communication response.

Original themes were therefore substantially modified by the inclusion of new findings emerging through the framework analysis. For instance, data previously contributing to and synthesised under a theme of physical distancing measures in schools and workplaces (original theme 6) were judged as aligning to findings within other major themes. A new major theme, on sustaining and maintaining public health communication and behaviour change, emerged with the inclusion of new evidence, and themes were re‐organised to reflect a more intuitive progression of communication purposes ‐ from building public trust through communication, engagement of communities in pandemic response and communications, through to the more specific elements (timing, content and tailoring) of public health communications and the maintenance of these and preventive behaviours over time.

The six major themes emerging from the data with newly‐included evidence are as follows:

Theme 1 Strengthening public trust and countering misinformation: essential foundations for effective public health communication;

Theme 2 Two way‐communication: involving communities to improve the dissemination, accessibility and acceptability of information;

Theme 3 Development of and preparation for public communication: target audience, equity and tailoring;

Theme 4 Public communication features: content, timing and duration, delivery;

Theme 5 Supporting behaviour change at individual and population levels;

Theme 6 Fostering and sustaining receptiveness and responsiveness to public health communication.

Findings of the synthesis

Public information and risk communication during the response to a pandemic are essential and critical components of the public health response to an outbreak. The evidence assembled to date again highlights that communication between authorities and governments and the public can be done well or poorly. To be most effective at promoting uptake of and adherence to protective measures, such as physical distancing measures, communication needs to be based on trust and planned ahead of time, engage communities meaningfully, and incorporate several key features including those related to content, timing, tailoring and reach within communities.

The findings of this update are organised under six major themes, within which subthemes emerging from the evidence are identified. The quality of the evidence on which the findings are based is also provided to aid with interpretation of the findings within each theme.

Theme 1: Strengthening public trust and countering misinformation: essential foundations for effective public health communication

Public trust in the authorities is an essential component of communication.

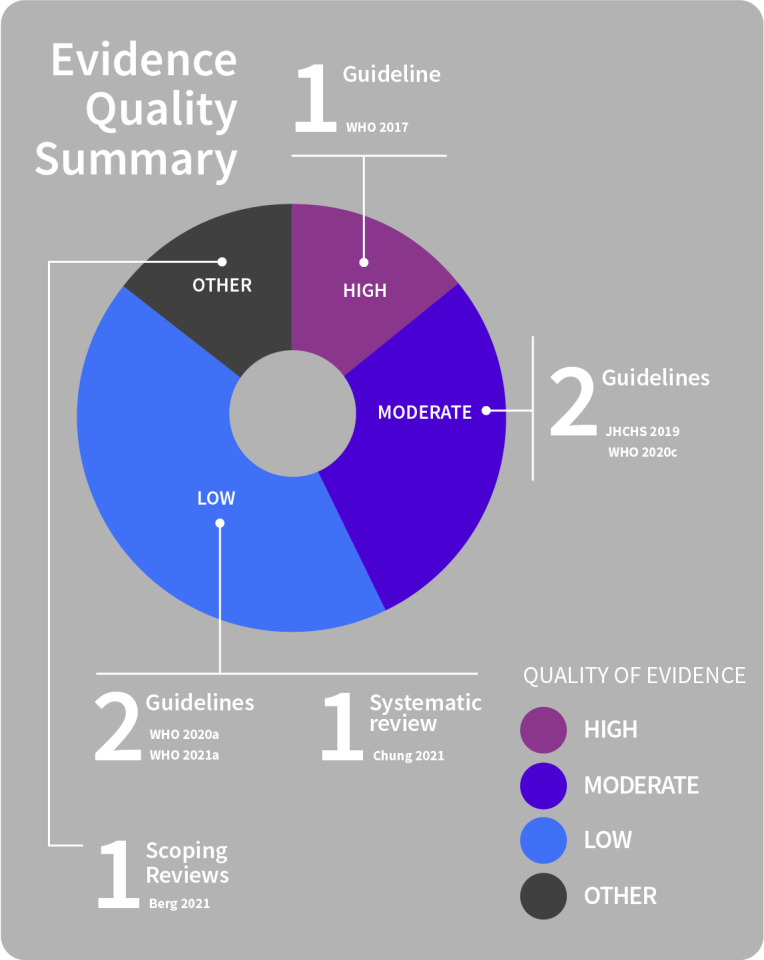

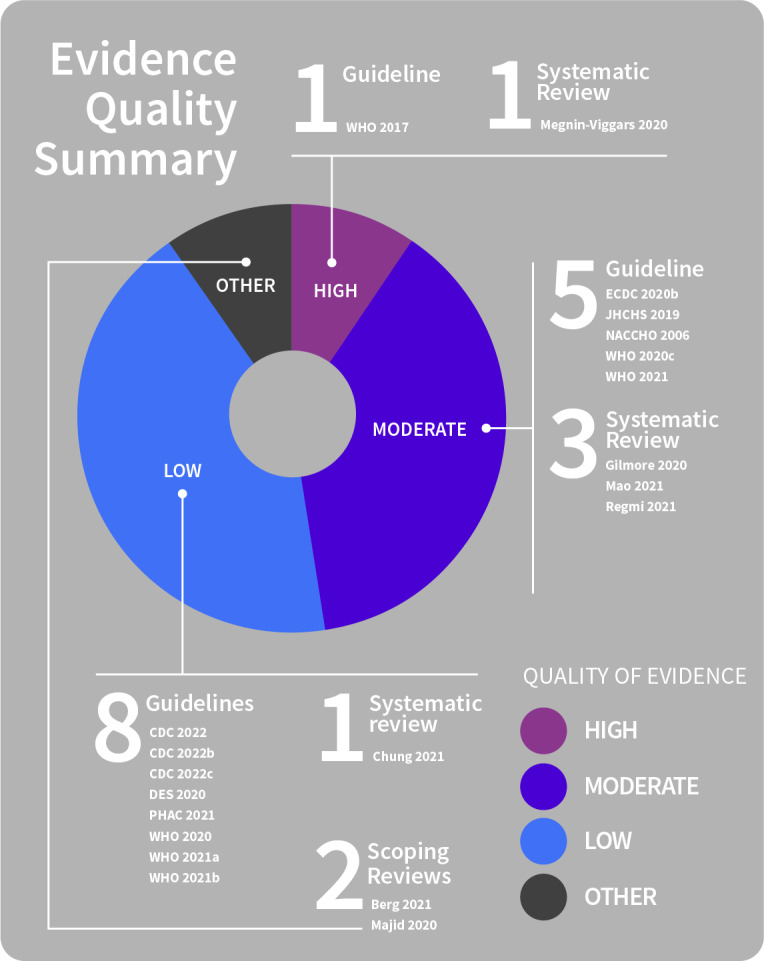

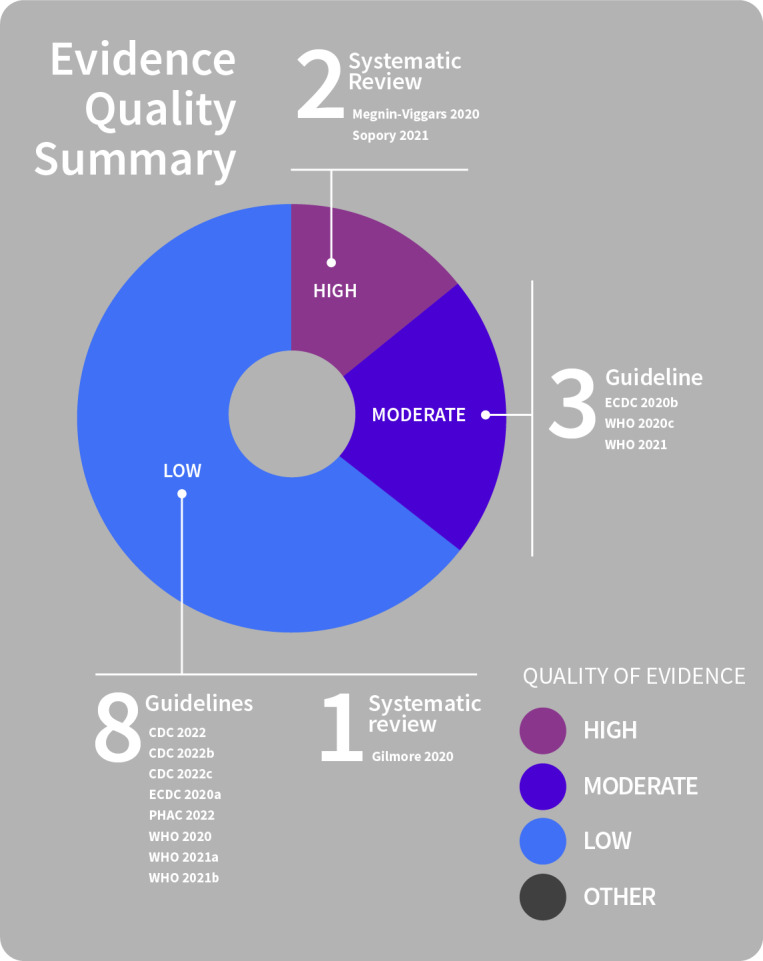

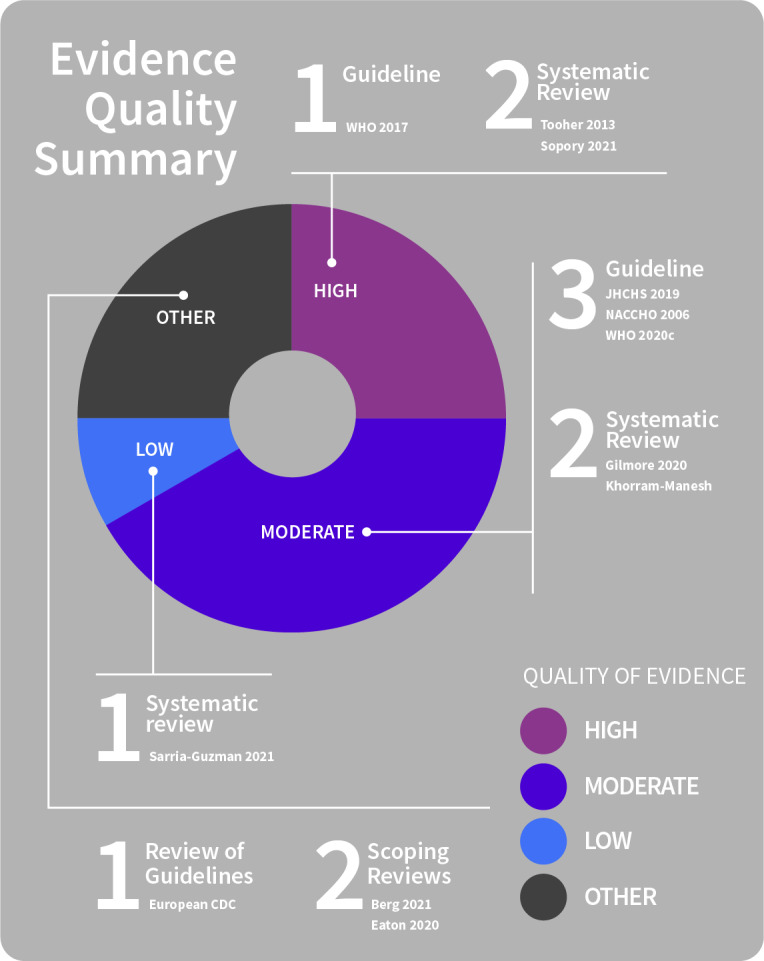

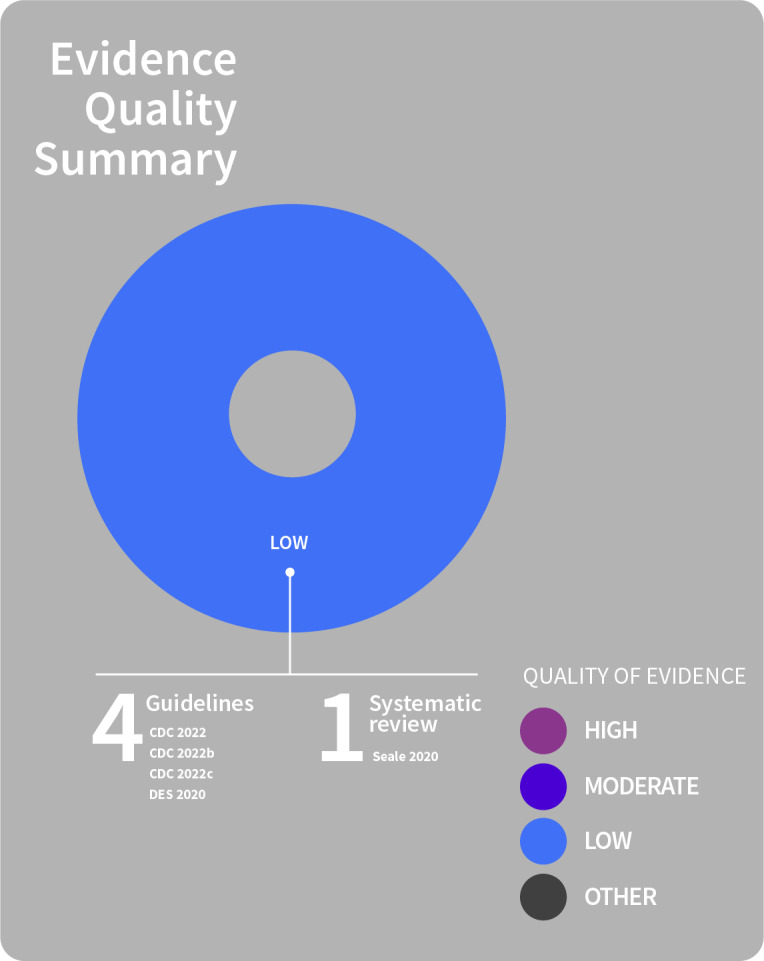

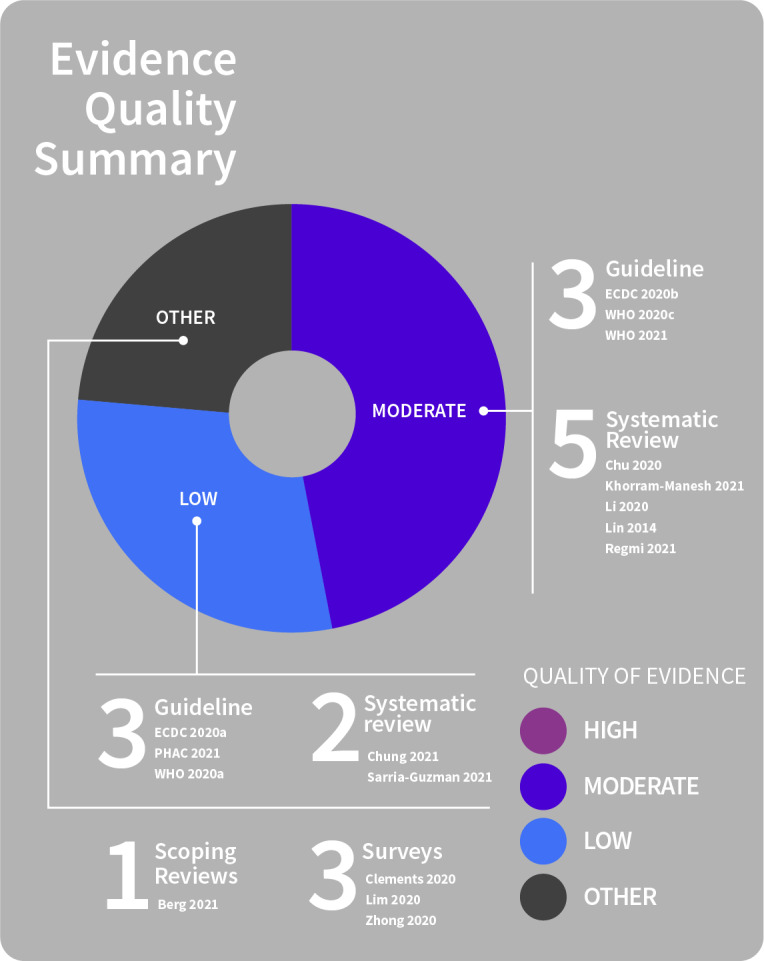

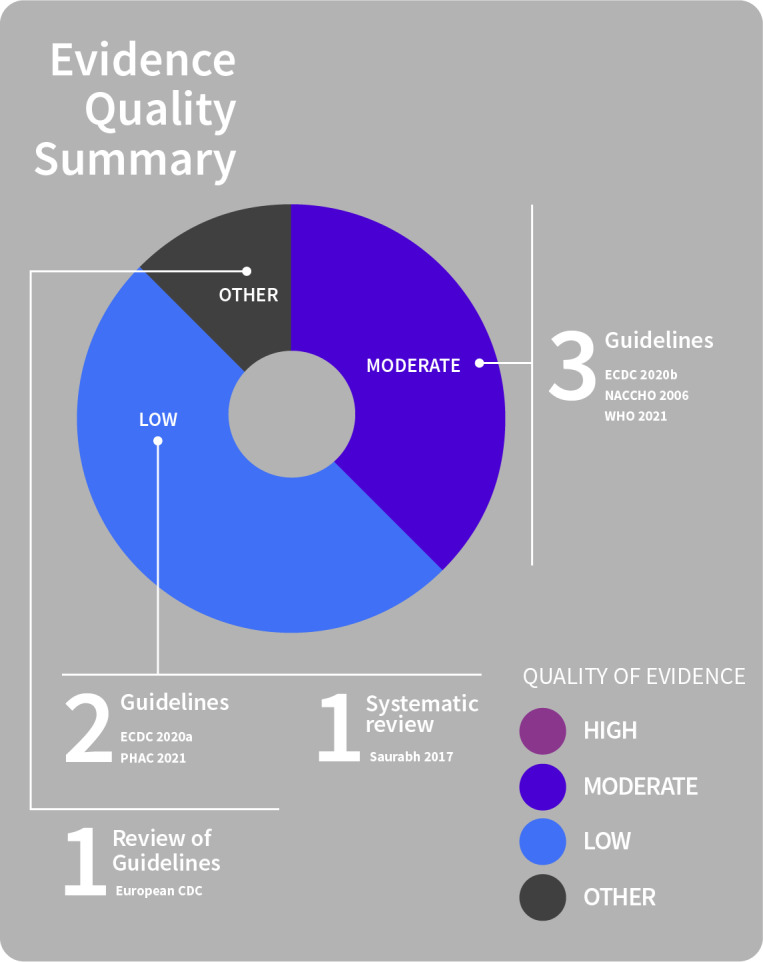

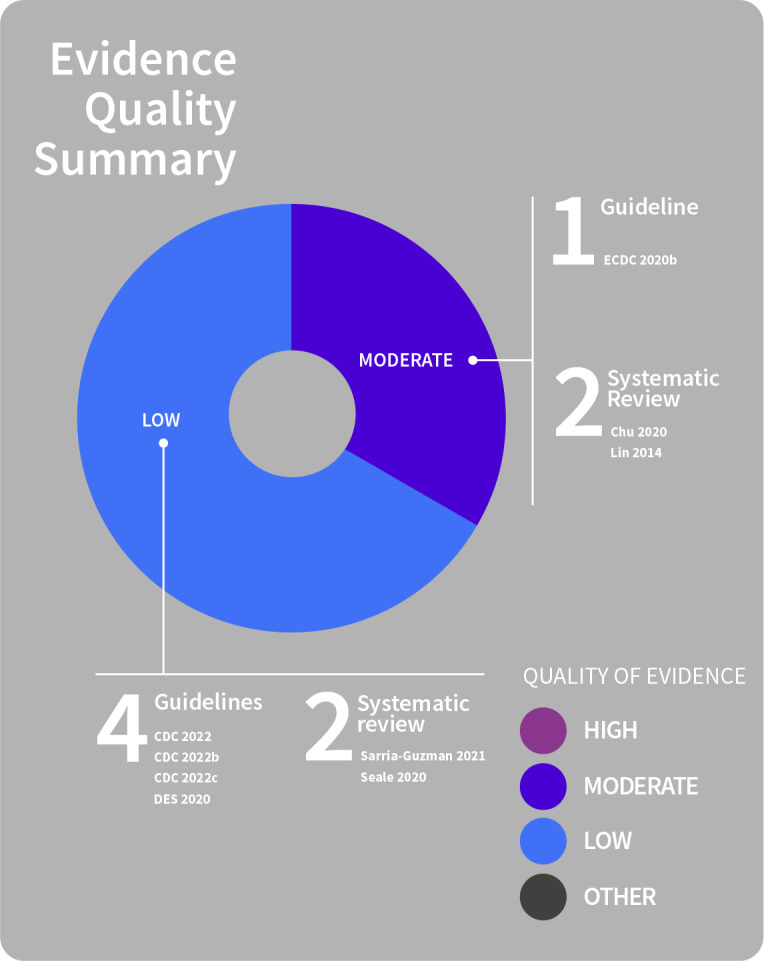

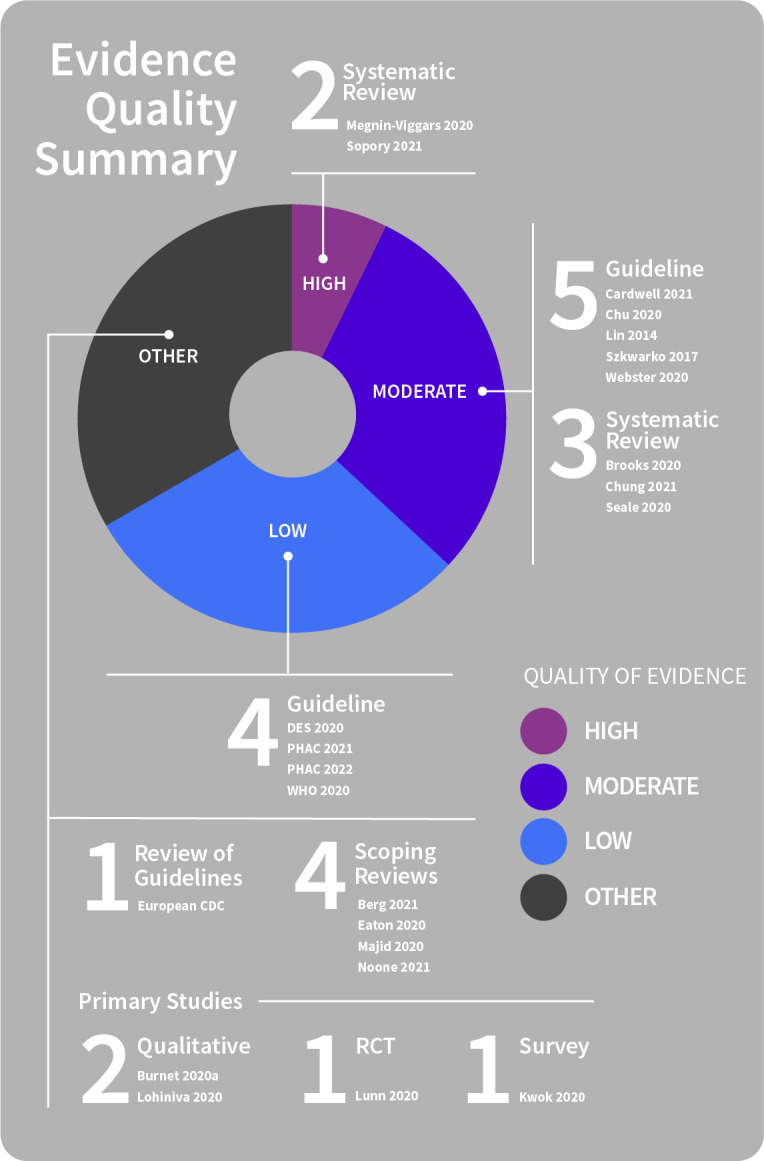

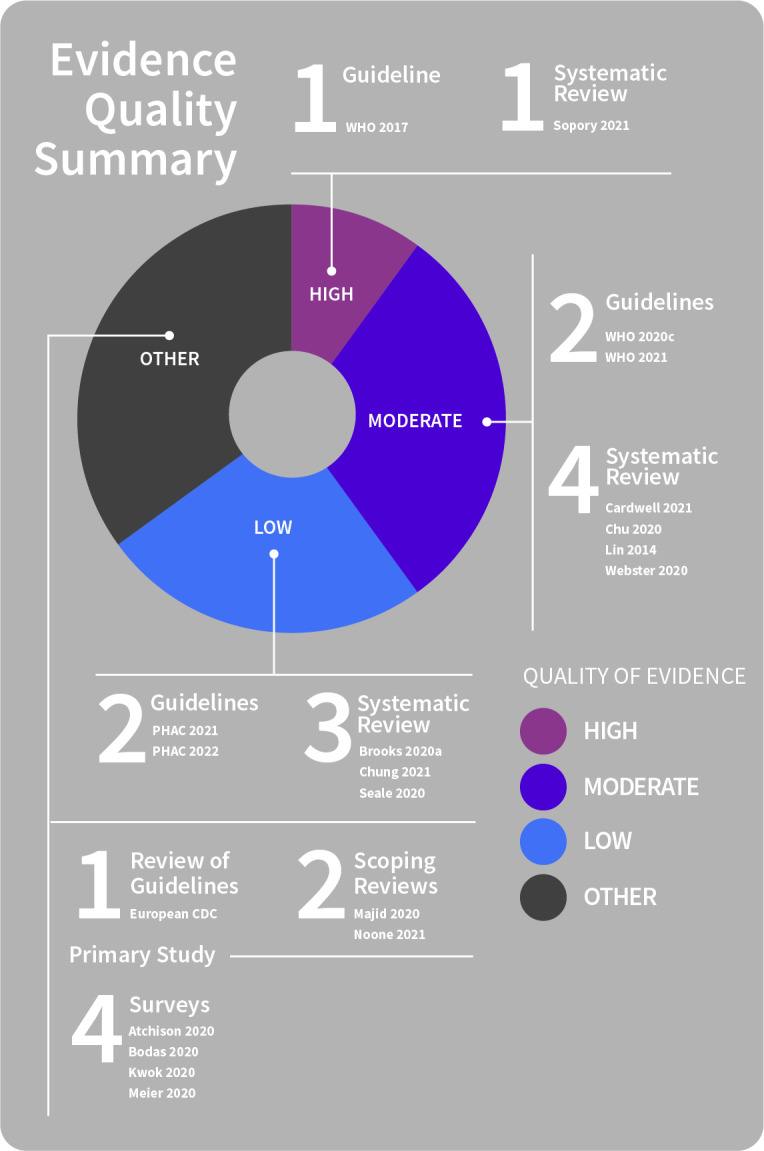

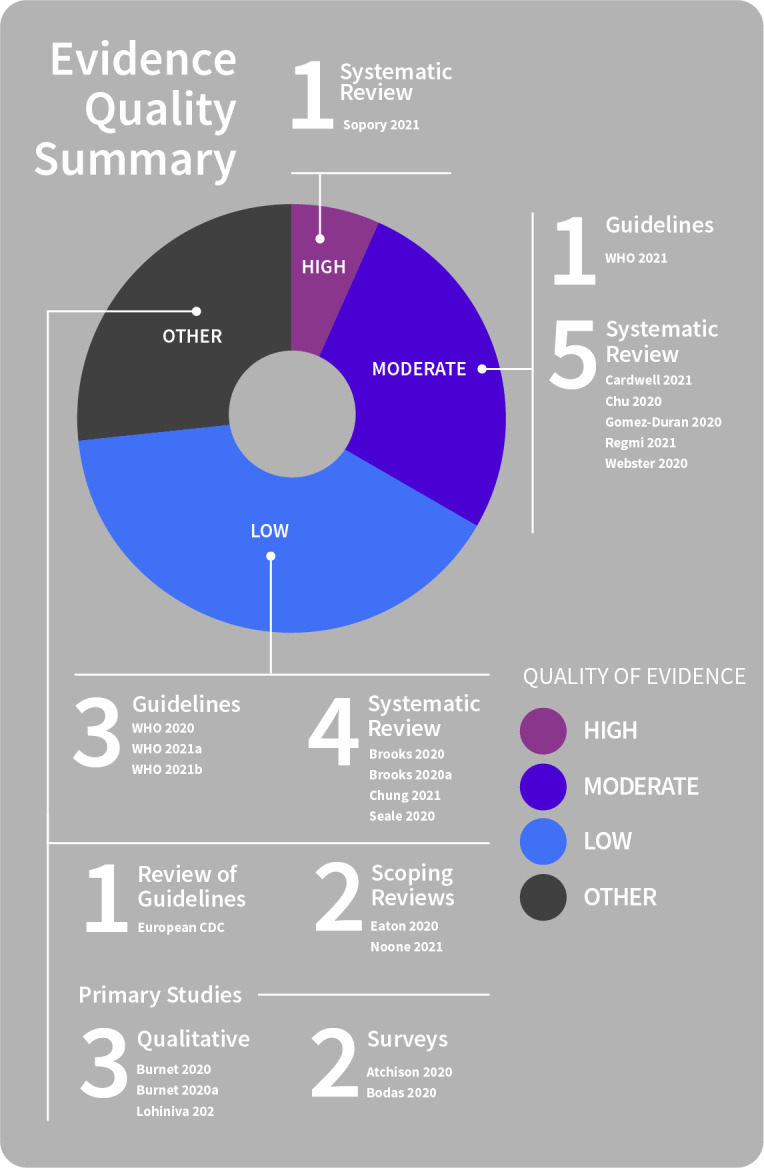

See Figure 2 for a summary of evidence quality for these findings.

2.

Public trust

Public trust is an essential element of effective communication before, during and after a pandemic outbreak (Berg 2021; JHCHS 2019; WHO 2017). The need to build and maintain public trust is mentioned directly or implied by several of the findings of this review, as it can be built or eroded by the approaches to or consequences of physical distancing or the communication approach taken.

Ideally, public trust in authorities is established and consolidated prior to an outbreak, or prior to introduction of or changes to public health measures (Berg 2021; WHO 2020a; WHO 2021a), but this is not always the case. Governments and authorities need to be mindful that building and maintaining trust amongst the population is essential when planning communication related to a pandemic (Chung 2021; WHO 2020c; WHO 2020a; WHO 2021a), as this is critical for promoting adherence to public health advice and increasing the effectiveness of preventive measures (WHO 2020c).

Facilitators of public trust

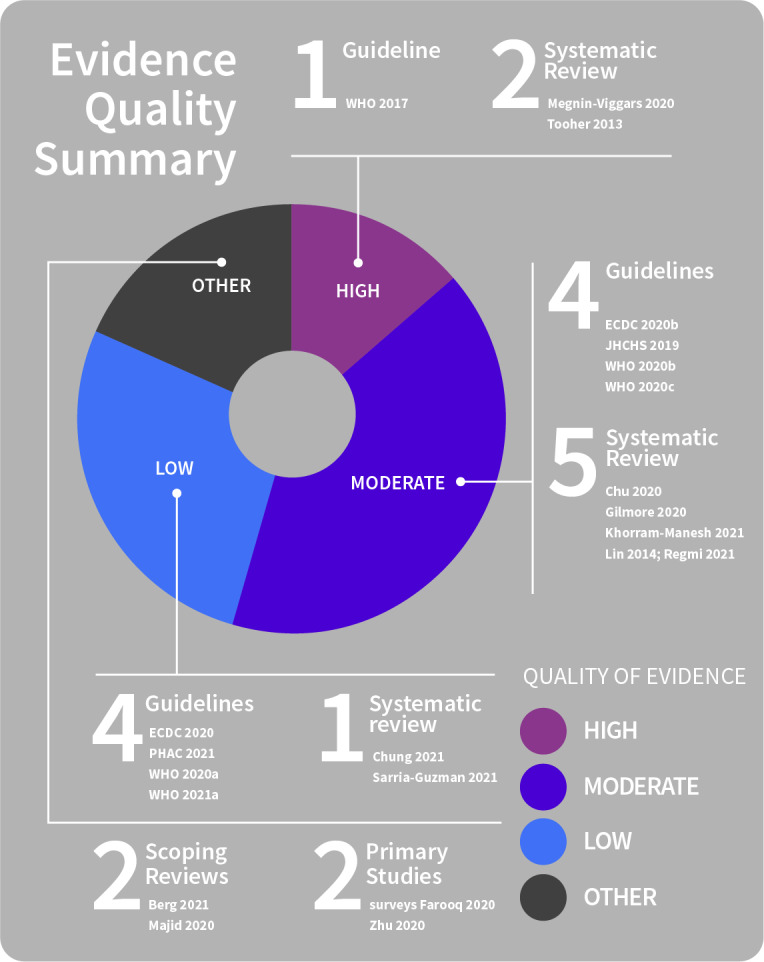

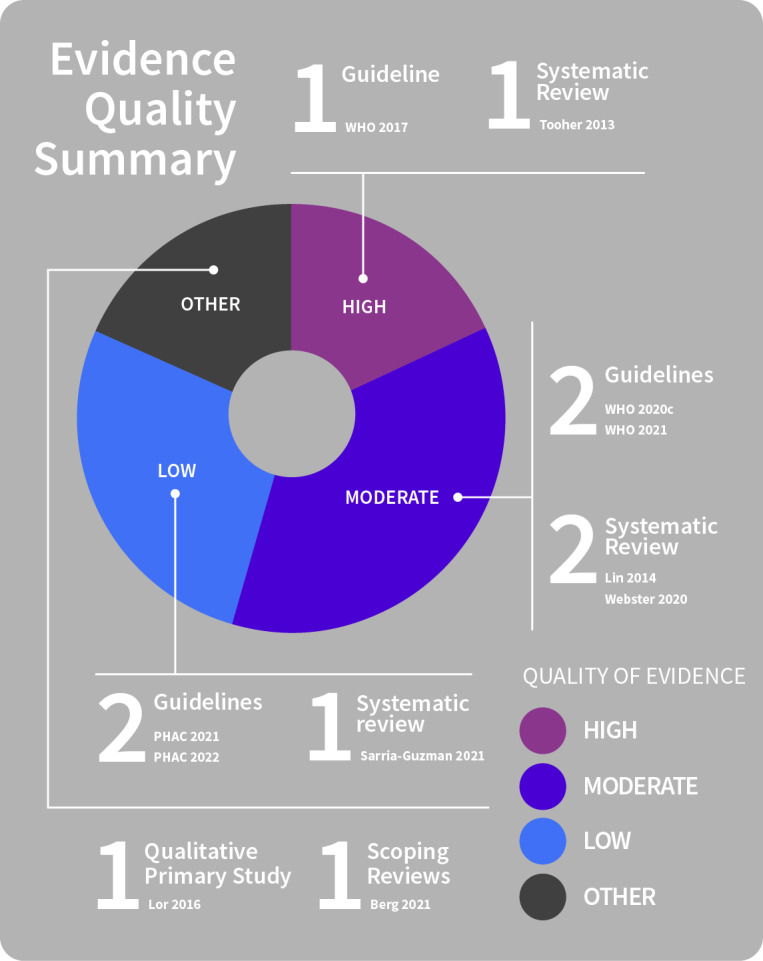

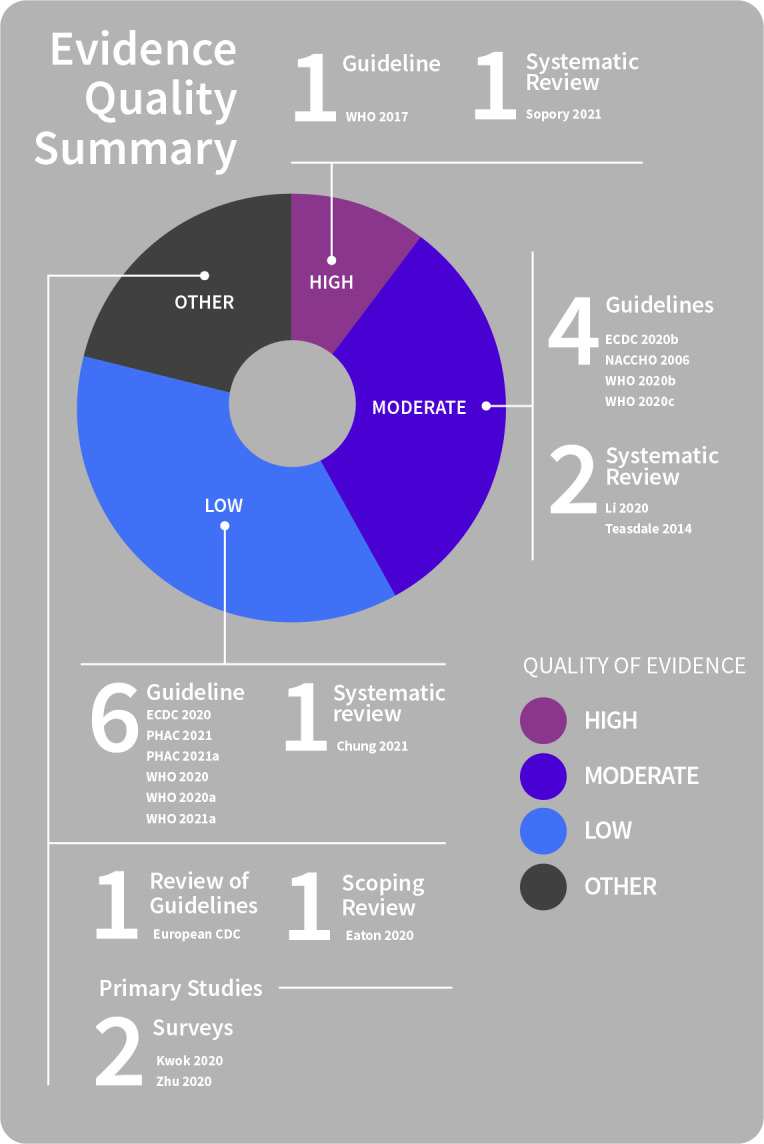

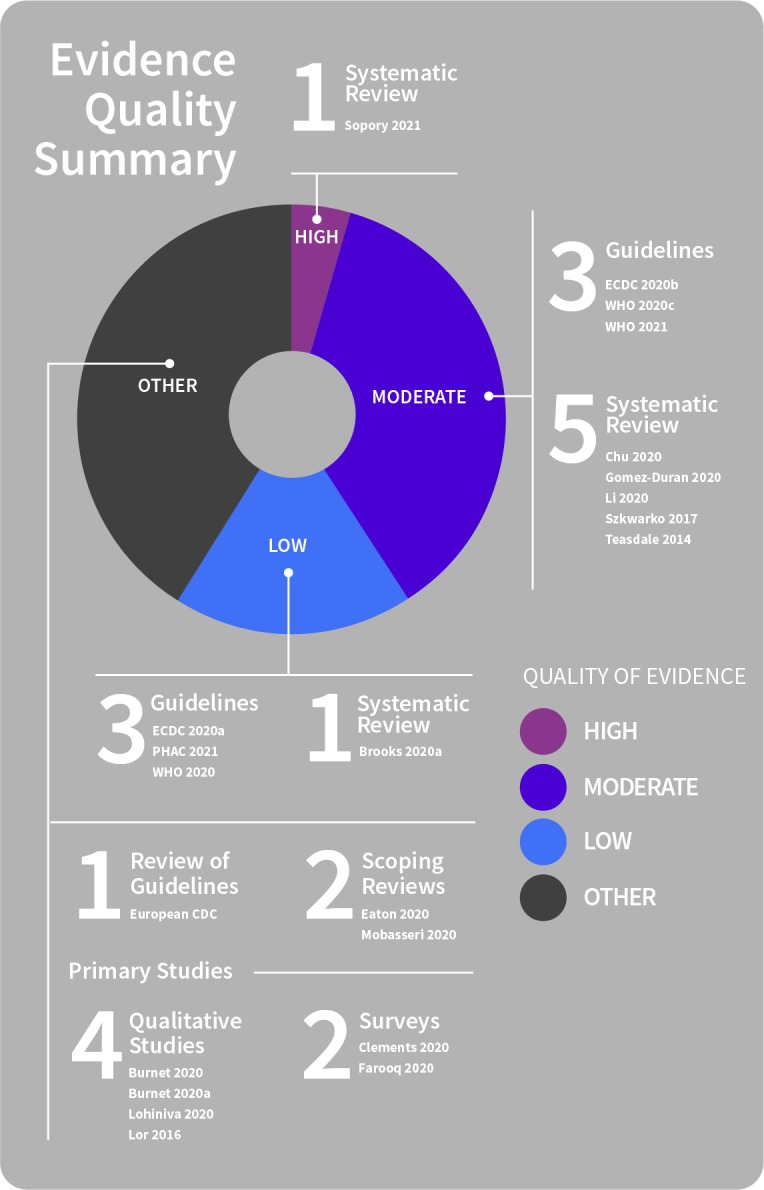

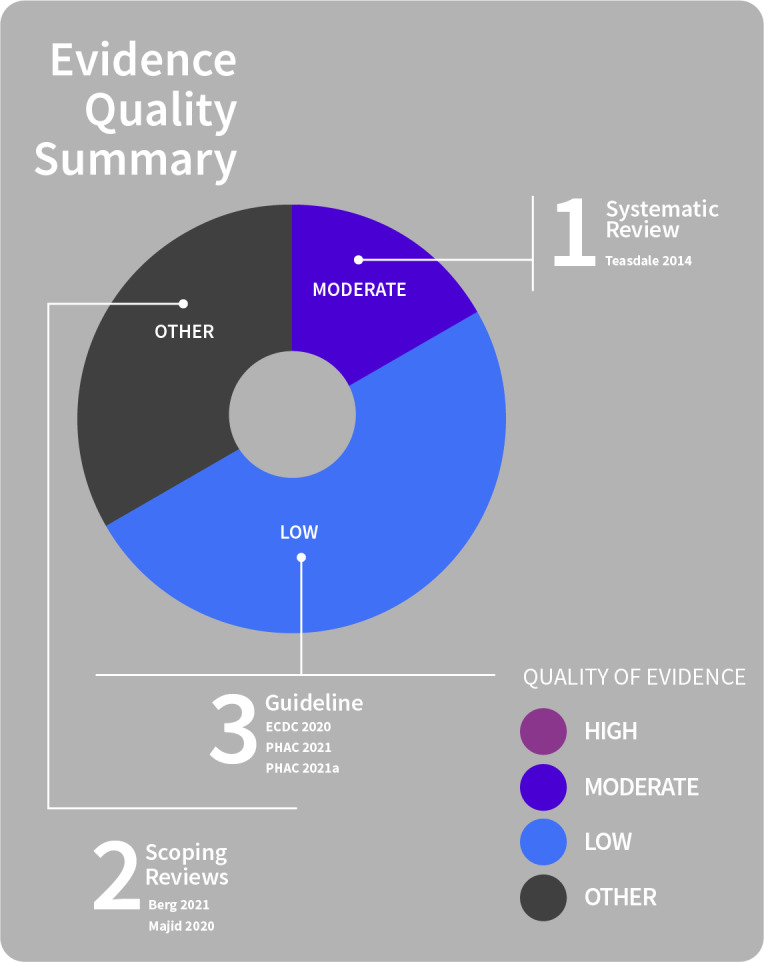

See Figure 3 for a summary of evidence quality for these findings.

3.

Facilitators of public trust

Several factors positively influence people’s trust of public health messaging and consequently, their adoption of and adherence to preventive behaviours.

Providing clear, timely and consistent (i.e. not conflicting or contradictory) information about risk, physical distancing measures and rationale for the measures that is accessible and disseminated widely through different media and channels helps to build public trust (Berg 2021; Chu 2020; Chung 2021; ECDC 2020b; Farooq 2020; Gilmore 2020; JHCHS 2019; Majid 2020; Megnin‐Viggars 2020; PHAC 2021; Regmi 2021; Sarria‐Guzman 2021; WHO 2017; WHO 2020a; WHO 2020b; WHO 2020c; WHO 2021a).

Findings also show:

Conflicting information from different levels of government, or between governments and authorities, needs to be avoided as this undermines public trust.

Governments and authorities need to regularly communicate epidemiological data to the public to build trust, particularly as measures change over time (WHO 2021a).

To build and sustain trust, communication from the authorities needs to clearly and transparently convey what is known and what is not (uncertainty), as well as the commitment to base decisions on the best available scientific knowledge at any time (ECDC 2020; Majid 2020; PHAC 2021; WHO 2020a; WHO 2020c).

As the pandemic continues, so does uncertainty. Clear, consistent public health communication that acknowledges this can help to mitigate the negative impact of uncertainty, without undermining trust (Chung 2021; Majid 2020; WHO 2020c).

Trust in information sources may also be associated with more accurate knowledge of risk and adoption of protective behaviours (Berg 2021; Regmi 2021; WHO 2021a). Promoting person‐centred, community‐led approaches may increase trust and social cohesion, so improving the feasibility of implementing preventive measures and adherence to them (WHO 2020c; WHO 2021a).

Higher trust in the ability of governments and public officials to work to control a pandemic outbreak and to ensure protection of privacy and personal information are also associated with greater likelihood of the recommended actions (e.g. engagement with contact tracing) being willingly engaged with, and adopted, by the community (Berg 2021; Chung 2021; Farooq 2020; JHCHS 2019; Khorram‐Manesh 2021; Lin 2014; PHAC 2021; WHO 2017; Zhu 2020).

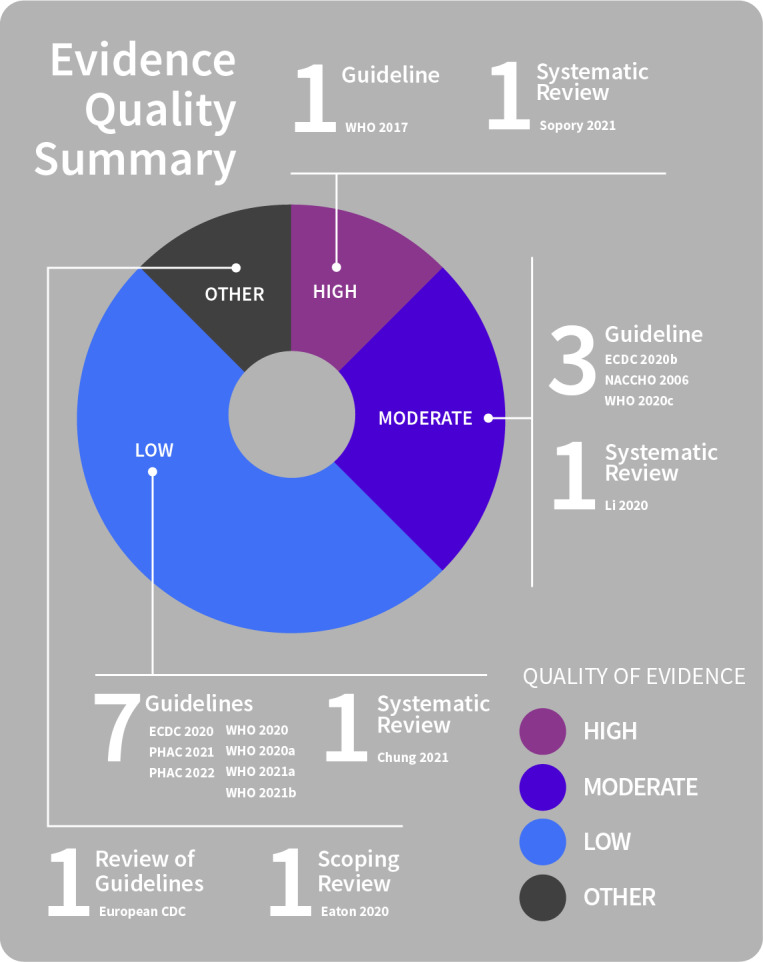

Barriers to public trust

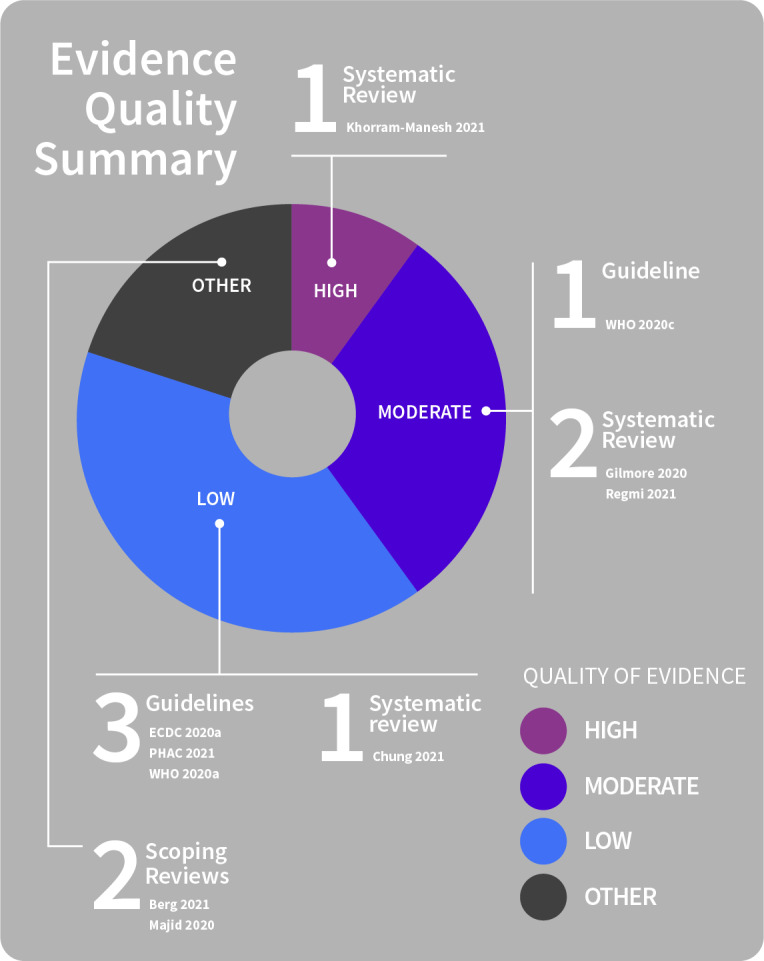

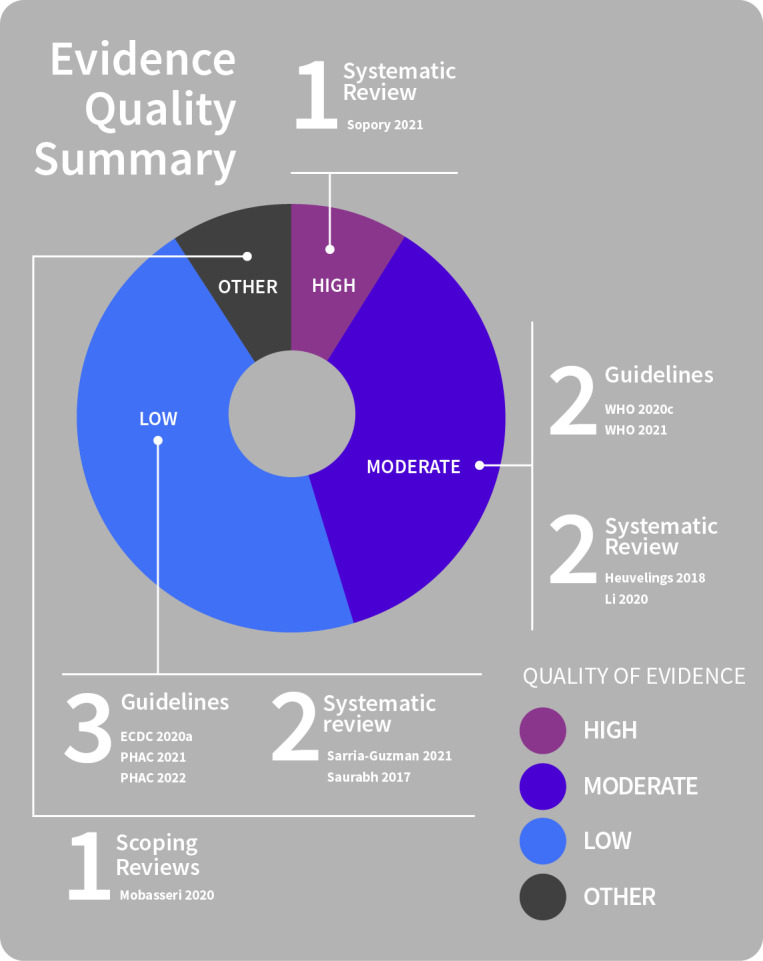

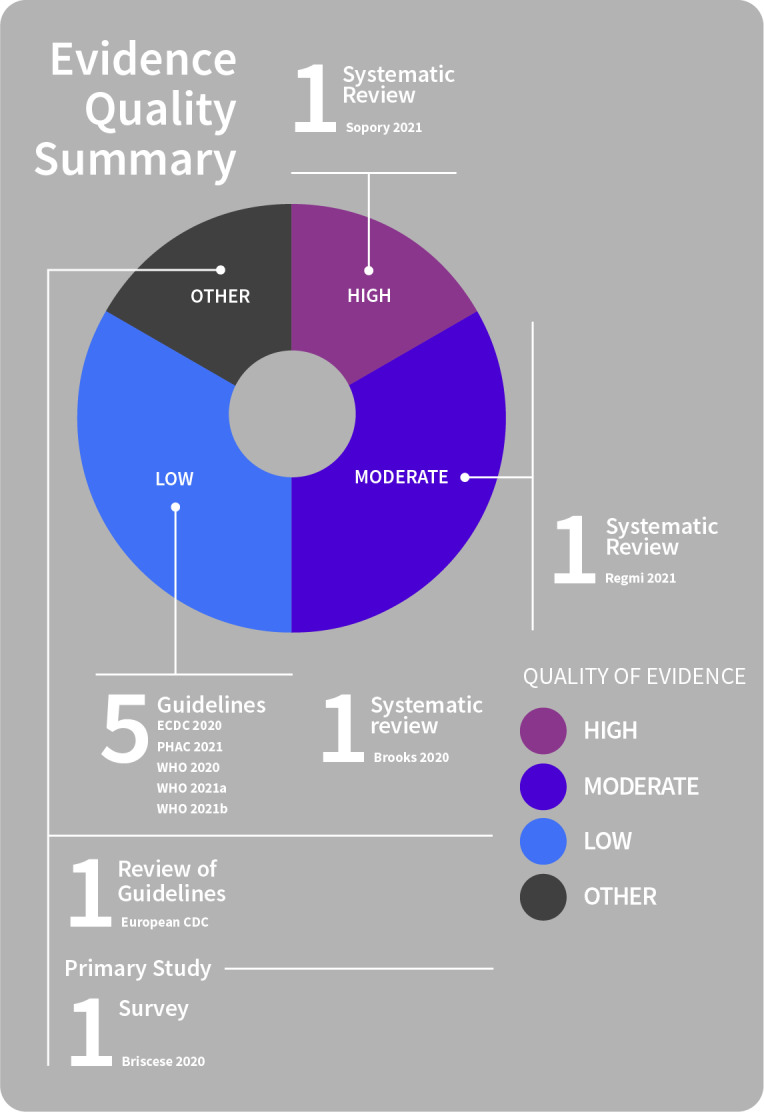

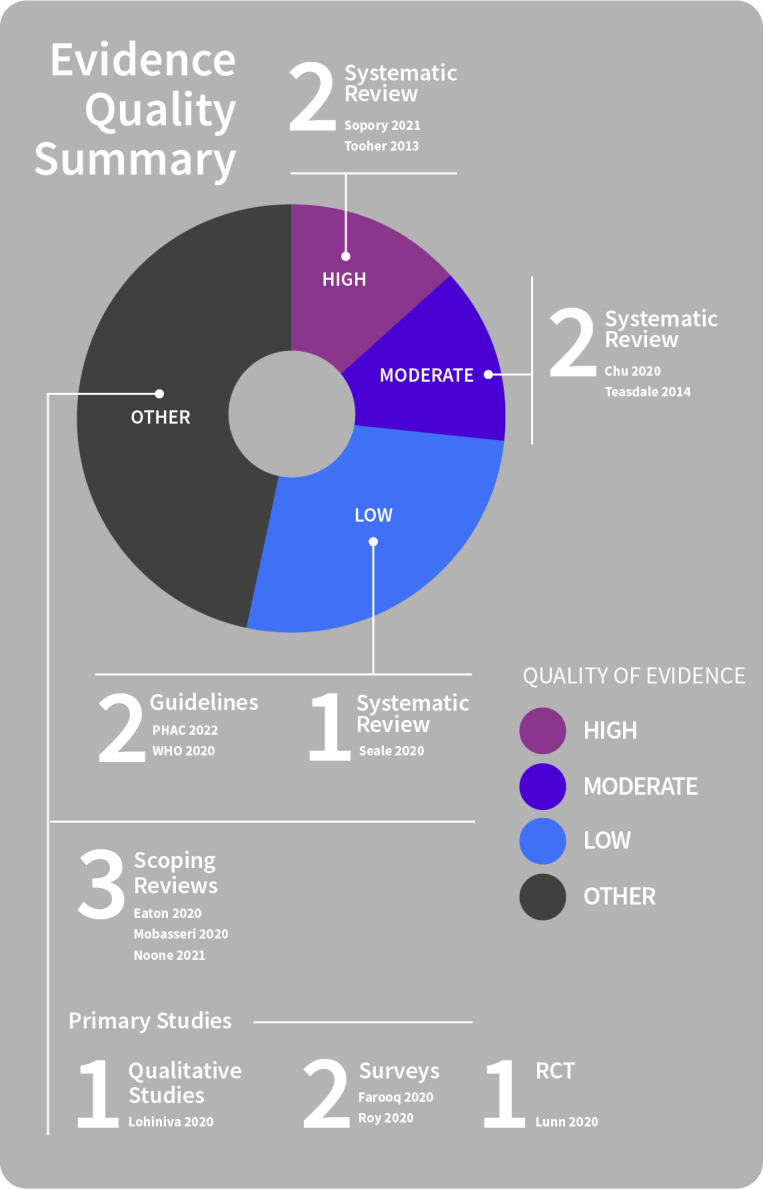

See Figure 4 for a summary of evidence quality for these findings.

4.

Public trust barriers

In addition to recognised contextual, social, and financial barriers to preventive behaviours, erosion of public trust is also key and can negatively influence people’s uptake of and adherence to preventive messaging and measures. These include conspiracy beliefs or mistrust of government or other organisations (Chung 2021; Gilmore 2020; Megnin‐Viggars 2020; WHO 2020c); mistrust or worries about accuracy of information reported by the media, including social media (Gilmore 2020; Majid 2020); and worsening inequalities, with the pandemic affecting the poorest and most vulnerable disproportionately (ECDC 2020a; WHO 2020c; see Appendix 1 for a comprehensive list of people identified as vulnerable during COVID‐19).

Findings also show:

Public health messaging that includes overstatements or exaggerations, that fosters fear, appeals to authority, repeats myths or misinformation (even where the aim is to counter with factually accurate information), or relies heavily on statistical information is generally less trusted and therefore less effective at promoting adherence to preventive measures (PHAC 2021).

Information that challenges or contradicts misconceptions, and is communicated from a trusted source, may reduce misconceptions if the communication is coherent (Majid 2020; Regmi 2021; WHO 2020a).

Frequent, drastic changes in reporting may be perceived as inaccurate by the public and lead to a loss of trust (Majid 2020), as may the reporting of inaccurate information (Berg 2021; Majid 2020).

Identifying and addressing misinformation

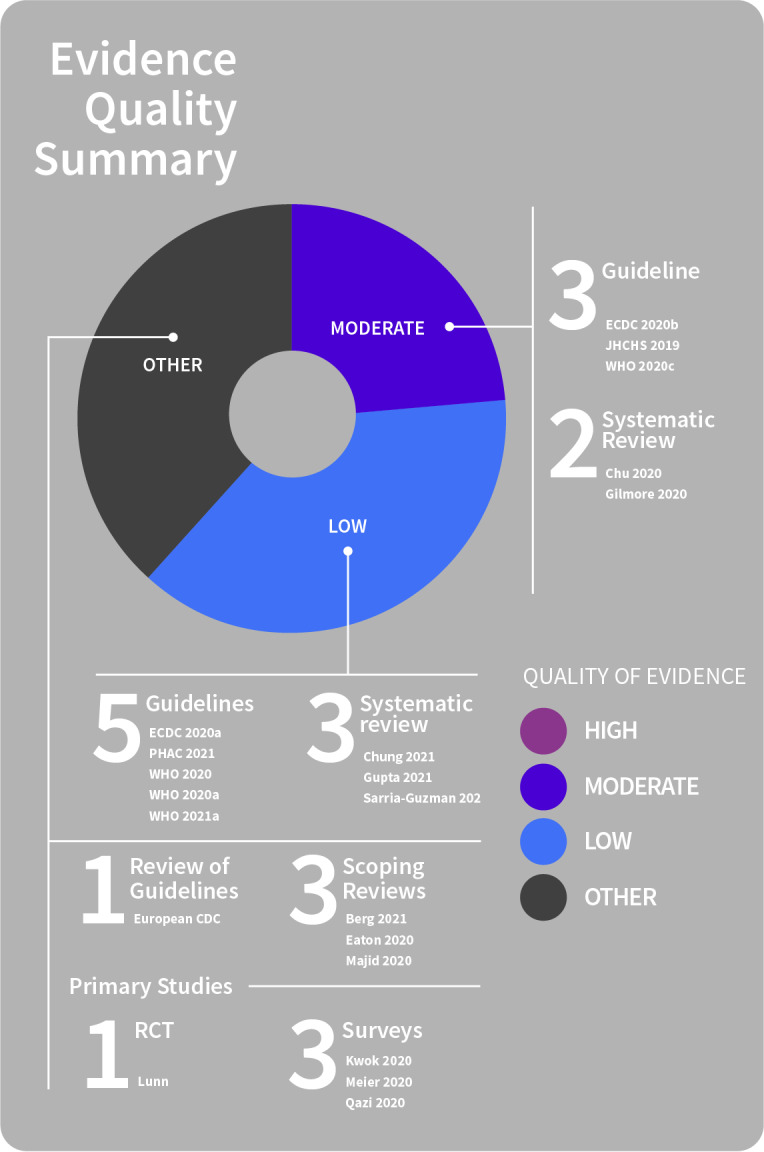

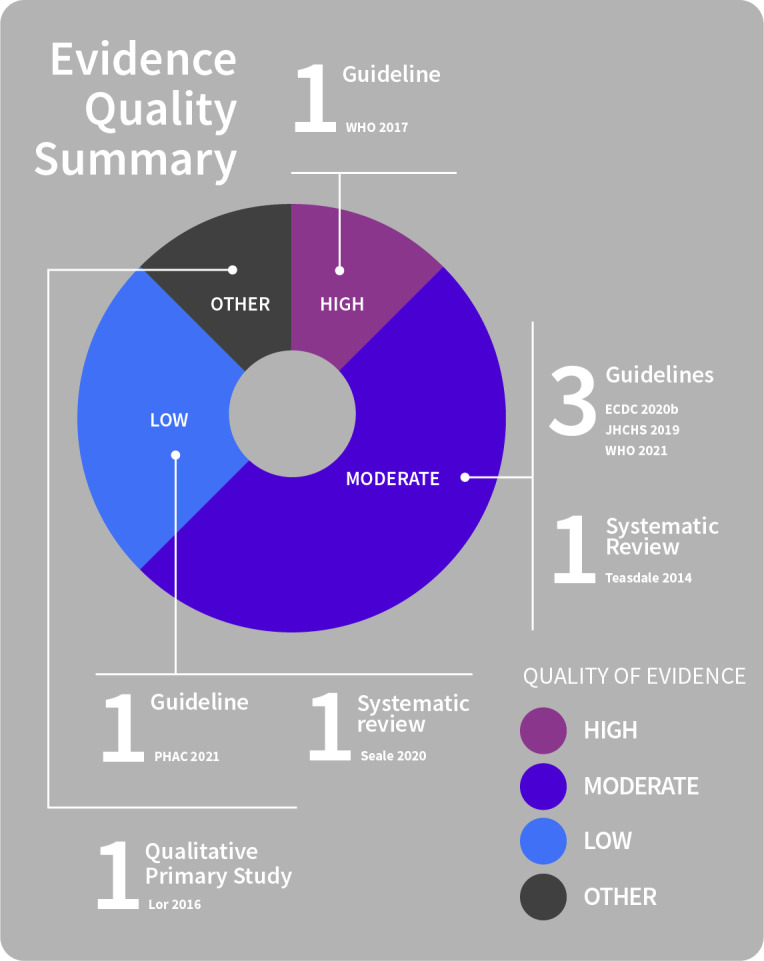

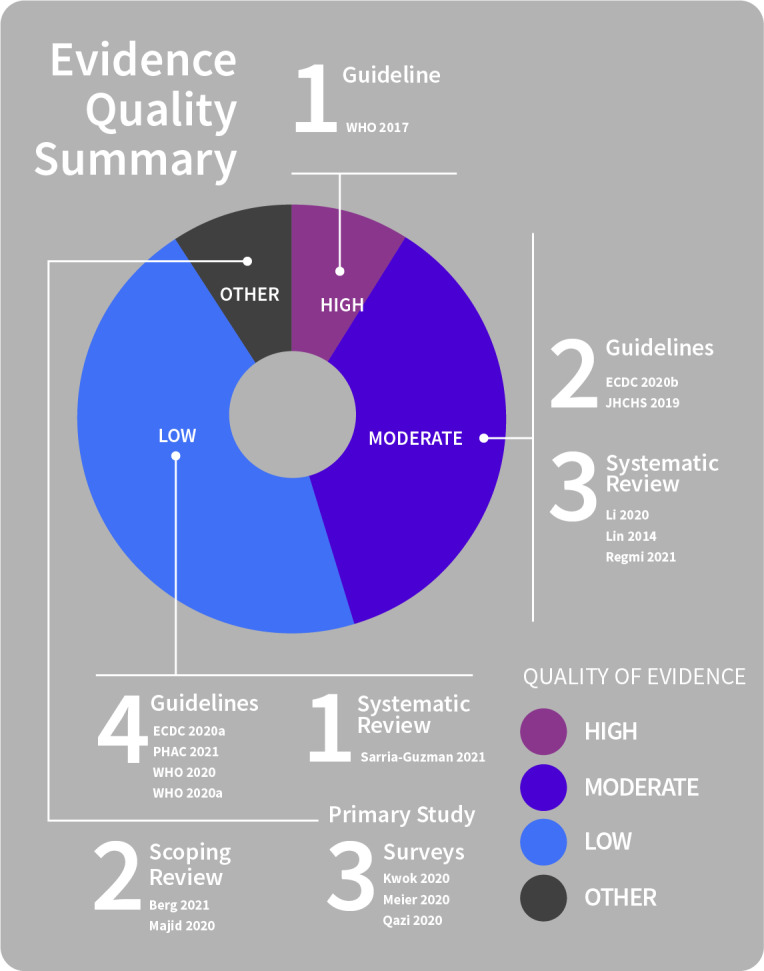

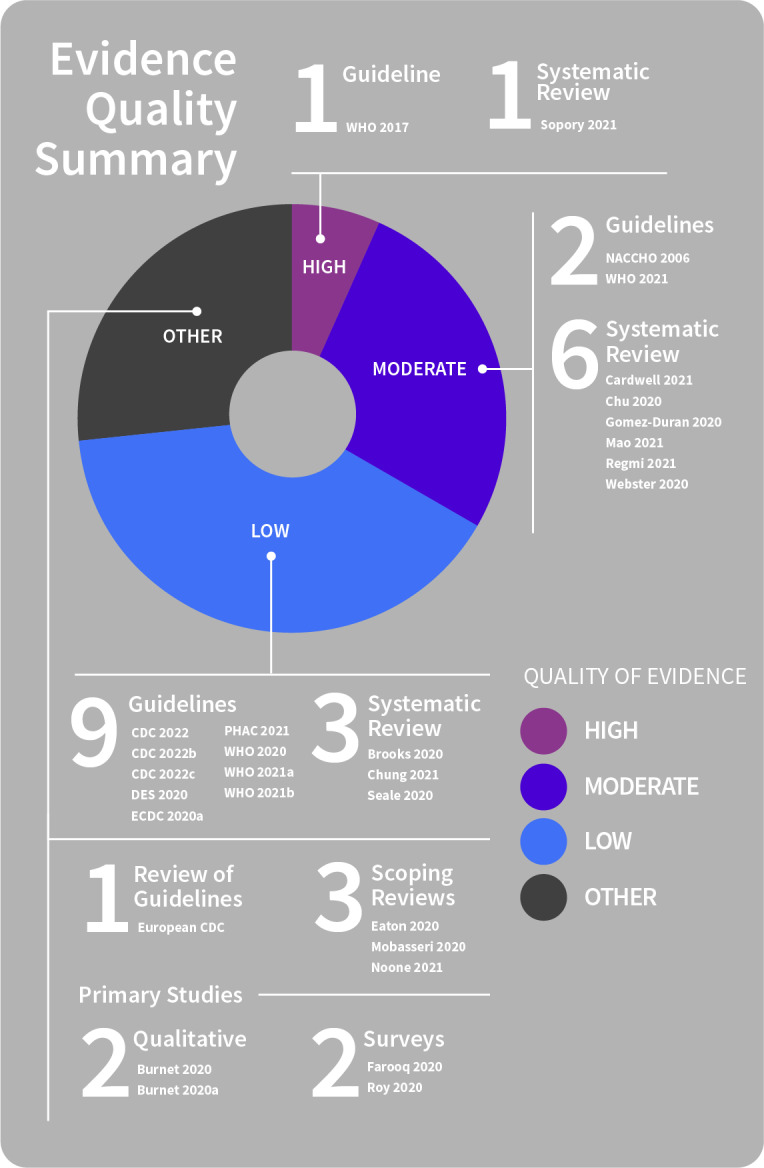

See Figure 5 for a summary of evidence quality for these findings.

5.

Misinformation

Identifying sources of misinformation

During pandemics, both accurate and inaccurate information spread quickly. It is not yet clear how communities navigate between accurate knowledge that promotes protective behaviours and inaccurate information that does not (Majid 2020).

Commonly accessed information sources may contribute to the spread of misinformation, fears, rumours, and misconceptions about required preventive measures and pandemic risks throughout the general public. This can negatively affect people’s adoption of preventive measures and prevent people from seeking medical care (ECDC 2020b; Gupta 2021; Majid 2020; WHO 2020a).

Misinformation from different sources can circulate alongside accurate information. This may be due to:

a lack of access and availability of accurate information (forcing people to seek alternative, less reliable sources of information);

inadequacy of information from reliable sources to support informed decisions regarding adoption of preventive measures; or

conflicting or contradictory public health messages (Majid 2020; Sarria‐Guzman 2021).

Even where members of the public are knowledgeable about an outbreak, many also actively seek information from diverse sources (Eaton 2020; Kwok 2020; Majid 2020; Meier 2020; Qazi 2020; Sarria‐Guzman 2021). Public access to information sources is a determinant of use. While perceived trustworthiness may also influence frequency of use, high exposure (frequency of use) to a particular information channel does not necessarily correspond with high levels of trust in information received via the channel. For example, use of online sources and social media platforms is high and growing, but trust in these channels is typically low, whereas traditional media and government sources are used less frequently despite being regarded as trustworthy (Kwok 2020; Majid 2020; Qazi 2020; WHO 2020c). Other research suggests that, in some studies, communication by traditional media is seen as alarmist and inaccurate, exaggerating or sensationalising risk information (Berg 2021; Majid 2020).

Some sources, specifically social media, may be more prone to spreading inaccurate information or misinformation about pandemic risks than others. Countering this (misinformation, rumours and contradictory messages) spread via social media remains problematic for health authorities (Berg 2021). Additionally, people may not verify information they receive via social media or their social networks (Berg 2021; Majid 2020; Sarria‐Guzman 2021).

Addressing misinformation

Proactive monitoring for rumours and misinformation is essential. It is critical that health authorities and the media adopt co‐ordinated strategies to identify and counter misinformation, as this may otherwise spread rapidly and negatively affect adherence to preventive measures (Berg 2021; Majid 2020; PHAC 2021; Sarria‐Guzman 2021; WHO 2020; WHO 2020a; WHO 2020c).

Ongoing public health messaging built on clear, accurate, and consistent information is needed to proactively build trust, clarify misconceptions and address misinformation (ECDC 2020b; Gilmore 2020; Majid 2020; PHAC 2021; WHO 2020a; WHO 2020c).

Co‐ordinated management of misinformation and information overload is needed as these may otherwise grow in the absence of available or accessible information or in the presence of conflicting messages (Majid 2020). For example, different health agencies or levels of government might actively work together to address common issues and use consistent messaging.

Providing the right information at the right time, to the right people via trusted, credible channels (e.g. community and faith leaders) is critical in helping to build public understanding and consensus about behaviours, such as physical distancing, to mitigate risk (Chu 2020; ECDC 2020a; Gilmore 2020; Gupta 2021; Majid 2020; PHAC 2021; WHO 2020c; WHO 2021a).

Strengthening the capacity for local and national media to identify and address misinformation may help to ensure consistent messages are communicated (PHAC 2021; WHO 2020c). Building trusted relationships between authorities and the mass media, or authorities engaging effectively with social media, may also build trust (Berg 2021).

Misconceptions may be more common amongst those with less trust of the government or authorities; therefore, community leaders, healthcare providers, the media and government all play an important role in communicating accurate, consistent information about disease and required health protection measures during a pandemic (Chung 2021; Majid 2020; Regmi 2021). Introducing information that contradicts misconceptions may be helpful, but this depends on the source and format of the information and on the level of trust people have in the source. Such information may help to counteract the negative effects of misconceptions on behaviours. However, it requires more cognitive work from people to process information at a higher level to inform their decisions and behaviours. This may delay the adoption of protective behaviours or increase the adoption of ineffective behaviours, lead to information overload and negative emotional states (Majid 2020).

Additionally, putting in place mechanisms to monitor, address misinformation and rumours, and respond to questions or feedback from the public (e.g. mass and social media, hotlines), is important in order to monitor how knowledge, beliefs, practices and behaviours change (Gilmore 2020). Public communication/information needs to be updated after analysis of public risk perceptions and adjusted in response to help promote uptake of public health advice and reduce mental health issues (Gilmore 2020; Regmi 2021; WHO 2020; WHO 2020a; WHO 2020c; WHO 2021a). Part of the role of such a system may be to identify or monitor for areas of uncertainty, inaccuracy or misinformation, as well as common questions in the public realm. This may in turn help to identify opportunities to address misinformation and allow the delivery of tailored communications (WHO 2017; WHO 2020; WHO 2020a; WHO 2021a).

Theme 2: Two‐way‐communication: involving communities to improve the dissemination, accessibility and acceptability of information

Community involvement is key in response planning, dissemination and reach of messages.

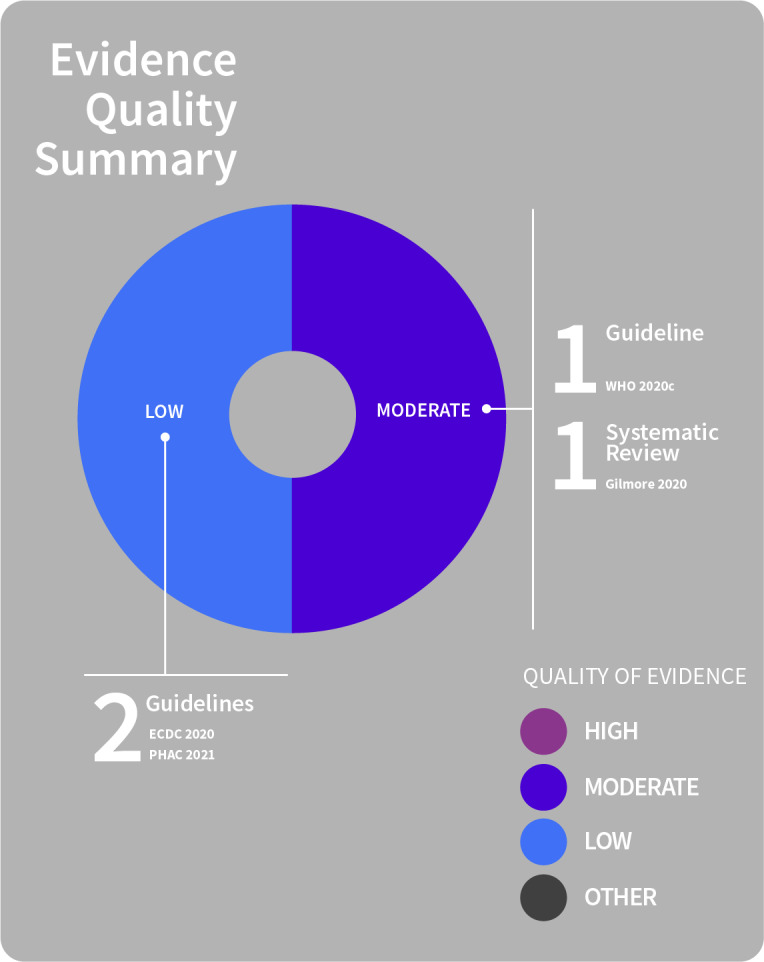

See Figure 6 for a summary of evidence quality for these findings.

6.

Community involvement in messaging

During a public health emergency, communication of information and advice is a critical public health intervention. The public, healthcare providers and other stakeholders all require trustworthy and accessible (language and literacy level) information to be available in a timely way in order to be able to protect their own and others’ health (PHAC 2021).

Physical distancing uptake, feasibility, acceptability and adherence are influenced by an array of cultural, geographic and economic factors. These include structural features (e.g. social context, living conditions, resources and services), traditions, sociocultural norms, the need for social interaction and access to space. Perceived norms are an important factor but vary across countries, as do other factors such as carer responsibilities (e.g. lower levels of distancing because of caring duties outside the home) (WHO 2020c; WHO 2021b).

Community involvement is needed to address barriers and to promote acceptability and adherence to preventive measures (WHO 2020c; WHO 2021b), and might be based on the two‐way participatory partnership approaches used successfully in past outbreaks (ECDC 2020a; WHO 2020c).

Working with the community is key to understanding local contexts (people’s needs, concerns, attitudes and beliefs, and barriers to implementing measures) and identifying localised solutions (CDC 2022b; Megnin‐Viggars 2020; WHO 2020; WHO 2021). Without community involvement, misinformation, confusion and mistrust can undermine public health efforts (WHO 2020c).

Involving the community helps to ensure an informed and appropriate person‐centred response by:

Gathering information on knowledge and behaviours (e.g. preferred information sources and formats) (CDC 2022b; Megnin‐Viggars 2020; PHAC 2021; Regmi 2021; WHO 2020; WHO 2020a; WHO 2020c; WHO 2021);

Developing (designing) and implementing appropriate messaging related to measures (information, education, communication) (Gilmore 2020); and

Tailoring the supports needed to follow public health measures (PHAC 2021; Regmi 2021).

Community involvement is also critical for identifying the ways people might respond in a crisis that are different from those that were predicted (NACCHO 2006). Community trust is built from sustained two‐way community engagement that is evidence‐based, communicated via trusted sources, and is responsive to community feedback (i.e. monitoring knowledge, beliefs and practices/beliefs and changes over time, and adapting course as needed) (ECDC 2020b; Gilmore 2020; JHCHS 2019; PHAC 2021; WHO 2017; WHO 2020c; WHO 2021a). However, this requires structures and processes to be in place (e.g. participatory governance, mechanisms for involving communities in policy and intervention design). This may be a key consideration for organisations when planning pandemic preparedness processes and structures (WHO 2020c).

Findings also show:

Two‐way community engagement is most effective if started early, if it is ongoing as information changes, and occurs through multiple channels. This can help to promote better understanding of the sociocultural context in which disease prevention and control efforts are needed (Gilmore 2020; WHO 2020a; WHO 2020c).

Community involvement is needed in all stages of local COVID‐19 responses: planning, design, implementation, monitoring, and evaluation (WHO 2020c; WHO 2021a).

Planning and decision‐making related to introduction or adjustment of public health measures needs to be undertaken collaboratively with local and regional leadership with the aim of balancing community needs and the benefits of measures against potential harms (CDC 2022; CDC 2022a; CDC 2022b; Gilmore 2020; PHAC 2021; WHO 2021a).

If stricter measures are needed, the impact of these need to be balanced against the positive and negative effects for the community, as a whole and for individuals. If measures are lifted, implications for transmission must be well understood, and adequate health systems and measures put in place to minimise risk to vulnerable people (WHO 2021a).

Incorporating community members into planning, response and monitoring activities of pandemic management teams is needed, with plans widely disseminated within communities to promote support (Gilmore 2020; WHO 2020c).