Abstract

Gardnerella vaginalis and Lactobacillus acidophilus have been shown to grow to high titers in a simple biofilm system. This system was used in the present investigation to compare the biofilm-eradicating concentrations (BECs) of amoxicillin, clindamycin, erythromycin, and metronidazole to standard tube MIC and minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC) results. With the lactobacillus, the BEC/tube MBC ratio was at least 16:1, while for G. vaginalis the ratio varied from 2:1 to 512:1. The simple continuous-culture system used in the present investigation is ideal for investigating the BEC for bacteria involved in complex ecological situations such as bacterial vaginosis and may be useful for the identification of the most effective and selective antibiotic therapy.

Bacterial vaginosis, a common form of vaginal discharge, is of major importance because of its association with the delivery of premature low-birth-weight infants (4, 5) and an increased prevalence of human immunodeficiency virus infection (9).

In bacterial vaginosis, the lactobacillus-dominated normal vaginal flora is replaced by a mixed flora in which organisms such as Gardnerella vaginalis, Mycoplasma hominis, and Mobiluncus spp. become dominant (13, 14). The details of the physiological and pathological conditions that underline the condition remain largely unresolved, reflecting in part the lack of a suitable system for studying the organisms individually and in combination. We have recently used the Sorbarod biofilm system to determine its suitability as a laboratory model for investigating bacterial vaginosis (11). Both G. vaginalis and Lactobacillus acidophilus grew to high concentrations under optimal growth conditions, maintaining titers in excess of 109 recoverable CFU/Sorbarod filter for at least 96 h (11). In the present investigation we have used this Sorbarod biofilm system to investigate the susceptibilities of G. vaginalis and L. acidophilus to a number of selected antibiotics and have compared this system to traditional susceptibility tests.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacteria.

Growth conditions for G. vaginalis ATCC 14018 and L. acidophilus ATCC 832 were as described previously (11). Briefly, for optimal growth in broth culture and biofilm, brain heart infusion (BHI) broth (Oxoid, Unipath, Basingstoke, United Kingdom) and deMan, Rogosa, Sharpe (MRS) broth (Oxoid) were used for the respective organisms.

Antibiotics, tube MIC and MBC, and Etest.

The following antibiotics were used: amoxicillin (SmithKline Beecham, Weybridge, United Kingdom), erythromycin (Abbott, Maidenhead, United Kingdom), and clindamycin and metronidazole (Rhone-Poulenc Rorer, Eastbourne, United Kingdom).

The method for determination of the tube MIC and the minimal bactericidal concentration (MBC) was that previously described (7). Overnight broth cultures were adjusted to a turbidity equal to that of a McFarland 0.5 standard (approximately 108 CFU/ml). The tubes were then inoculated so that the initial concentration of organisms in these experiments was approximately 105 CFU/ml (7). The media used were those that gave optimum growth of the two bacteria in biofilms, BHI broth, and MRS broth (11). When testing G. vaginalis against metronidazole under anaerobic conditions, BHI broth was dispensed into 5-ml glass tubes, and the tubes were autoclaved and incubated in an anaerobic cabinet (37°C) overnight before antibiotic dilution and inoculation with G. vaginalis. In order to control all these experiments, the Etest (Biodisk, Solna, Sweden) was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions with Diagnostic Sensitivity Test (DST) Agar (Difco). Bacteroides fragilis NCTC 9343 was also used as a control for the tests done under anaerobic conditions, and the Etest MIC for B. fragilis was 0.5 mg/liter. A Du Scientific MK3 Anaerobic Workstation (Whitley Scientific Ltd., Shipley, United Kingdom) was used for anaerobic incubation.

Sorbarod biofilms.

The Sorbarod biofilm methods described previously were used (2, 6). Briefly, 12 individual Sorbarod filters (diameter, 10 mm; length, 20 mm; Ilacon, Kent, United Kingdom) were prepared in order to have sufficient numbers for inclusion of an antibiotic-free control and to cover a suitable range of twofold dilutions of an antibiotic (see Results). The Sorbarod filters were inoculated with 3 ml of an overnight broth culture of an organism. The entire apparatus was placed in a 37°C incubator. Feed broth was then delivered to each biofilm at a rate of 0.1 ml/min by means of a 12-channel peristaltic pump (Watson Marlow, Falmouth, United Kingdom). The effluent was collected in replaceable 150-ml glass bottles downstream of the biofilm. After 24 h, when steady-state growth had been reached (11), individual biofilms were exposed for 18 h to a single concentration of an antibiotic made up in BHI broth or MRS broth, which was delivered to the biofilms at the flow rate mentioned above. After this 18-h period, effluent from the biofilm was collected for 15 min in a sterile container. This enabled determination of the titer of the planktonic bacteria that continually elute from a biofilm. The Sorbarod biofilm was then disintegrated in 5 ml of broth with a vortex mixer. Titrations were done immediately in triplicate by a recognized method (7). All biofilm titers per milliliter were multiplied by a factor of 6.57 to take into account the volume of 5 ml of broth added and the volume of the biofilm itself. Biofilm titers thus represent the recoverable numbers of CFU/biofilm filter. The biofilm-eradicating concentration (BEC) and the biofilm effluent MBC were those concentrations of an antibiotic that eliminated the organism from a biofilm and the effluent, respectively, as described previously (2).

Light microscopy studies of biofilms.

Light microscopy studies of the Sorbarod biofilms were done in order to determine the distribution of bacteria in this biofilm mode of growth. Intact Sorbarod filters were fixed in 10% buffered formalin, dehydrated through a series of alcohol and xylene, and then embedded in paraffin wax. Microtome sections were stained with the Gram stain and were photographed with a Nikon Optiphot 2 photomicroscope (Nikon UK, Kingston upon Thames, United Kingdom).

RESULTS

The results of the tube MIC and MBC, BEC, and effluent MBC tests and the Etest are presented in Table 1. The values obtained for the tube MIC tests are similar to those obtained in previously published work (1, 8, 10).

TABLE 1.

Tube MIC/MBC, BEC for the biofilm, and effluent MBCs for G. vaginalis and L. acidophilus grown in BHI broth or MRS brotha

| Antibiotic, organism (broth type) | Tube MIC (mg/liter)/MBC (mg/liter) | Tube MBC/MIC ratio | BEC (mg/liter) | BEC/tube MBC ratio | Ef MBC (mg/liter) | Etest MIC (mg/liter) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amoxicillin | ||||||

| G. vaginalis | 0.06/0.06 | 1 | 32 | 512 | 4 | 0.016 |

| L. acidophilus (BHI) | ND/0.06 | ND | 1 | 16 | 1 | 0.19 |

| L. acidophilus (MRS) | 0.06/0.5 | 8 | 16 | 32 | 16 | 0.19 |

| Clindamycin | ||||||

| G. vaginalis | 0.004/0.008 | 2 | 0.016 | 2 | 0.004 | 0.016 |

| L. acidophilus (BHI) | ND/0.06 | ND | 1 | 16 | 0.5 | 0.016 |

| L. acidophilus (MRS) | 0.06/4 | 64 | 64 | 16 | 64 | 0.016 |

| Erythromycin | ||||||

| G. vaginalis | 0.004/0.03 | 8 | 1 | 32 | 0.5 | 0.016 |

| L. acidophilus (BHI) | ND/0.125 | ND | 4 | 32 | 2 | 0.032 |

| L. acidophilus (MRS) | 0.25/8 | 32 | >128 | >16 | >128 | 0.032 |

| Metronidazole (CO2), G. vaginalis | 8/32 | 4 | 128 | 4 | 128 | 8 |

| Metronidazole (An), G. vaginalis | 2/8 | 4 | ND | ND | ND | 2.0 |

Etests were done with DST agar plates as described in the text. Tests with G. vaginalis and metronidazole were done either in an atmosphere of 6% CO2 or under anaerobic (An) conditions, as indicated. ND, not done; Ef MBC, effluent MBC.

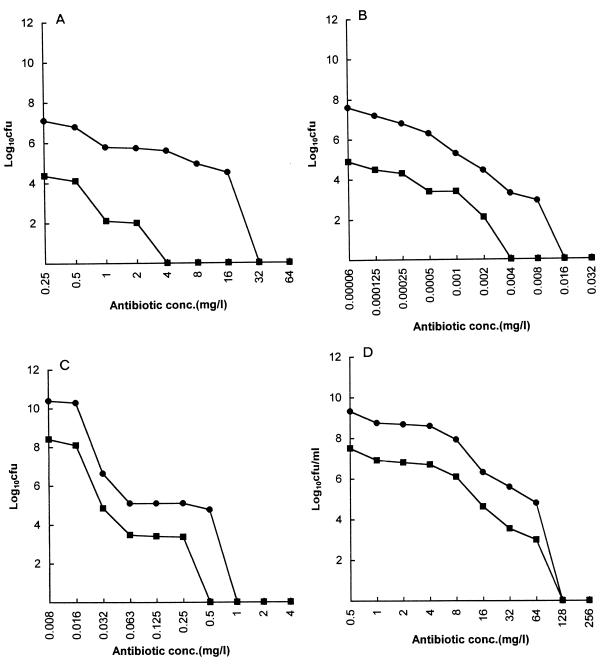

The results for G. vaginalis showed that the tube MBC/MIC ratio varied from 1 to 8. The BEC/tube MBC ratio varied from 2 to 512, indicating significant differences in the effectiveness of individual antibiotics in eradicating a biofilm population of this organism. With the exception of the values for amoxicillin, the BEC and effluent MBC were similar.

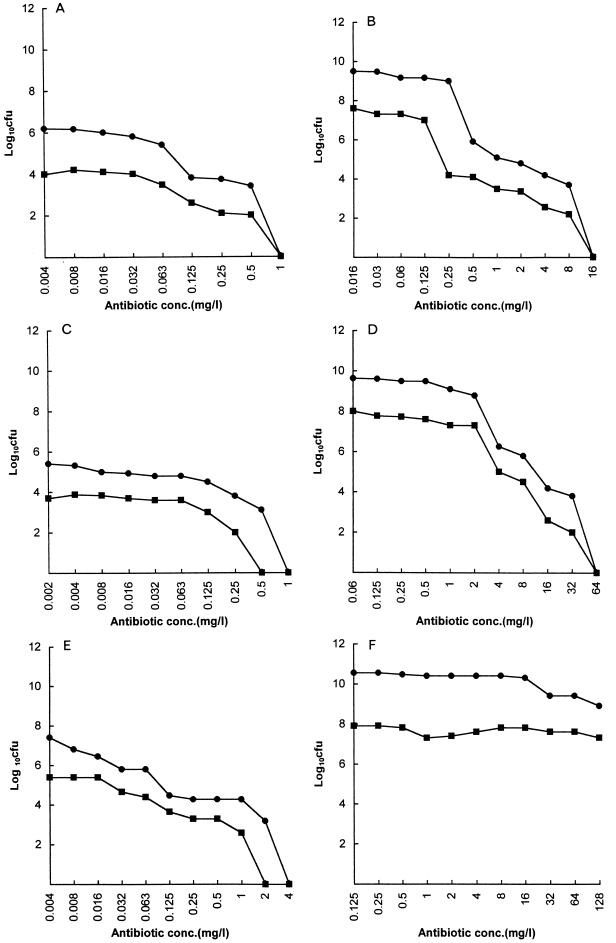

In the case of L. acidophilus grown in BHI broth in which there were relatively low concentrations of organisms, on the order of 106 to 107 recoverable CFU/filter, the BEC/tube MBC ratio was at least 16:1. Because of the relatively low numbers of organisms in the BHI broth, the tube MIC could not be reliably determined, and these values are thus not recorded. In MRS broth, in which much higher organism concentrations were achieved (>109 recoverable CFU/filter), both tube MBC/MIC and BEC/tube MBC ratios were at least 8:1.

Graphical presentation of the results of the BEC and effluent MBC experiments are presented in Fig. 1 and 2. As shown previously (11), the titer of bacteria eluting off the biofilm into the effluent was several log values less than that in the biofilm. In essentially all cases the pattern of susceptibility of an organism in the biofilm matched that of an organism in the biofilm effluent.

FIG. 1.

Viability of G. vaginalis in Sorbarod biofilms (•; expressed as total recoverable CFU/Sorbarod filter) and in biofilm effluent (planktonic growth); (▪; expressed as CFU/milliliter). After 18 h of exposure to an antibiotic at a single concentration, effluent was collected for 15 min and the Sorbarod biofilm was then disintegrated as described in the text. (A) Amoxicillin; (B) clindamycin; (C) erythromycin; (D) metronidazole.

FIG. 2.

Viability of L. acidophilus in Sorbarod biofilms (•; expressed as total recoverable CFU/Sorbarod filter) and in biofilm effluent (planktonic growth); (▪; expressed as CFU/milliliter). After 18 h of exposure to an antibiotic at a single concentration, effluent was collected for 15 min and the Sorbarod biofilm was then disintegrated as described in the text. (A and B) Amoxicillin; (C and D) clindamycin; (E and F) erythromycin. (A, C, and E) L. acidophilus grown in BHI broth; (B, D, and F) L. acidophilus grown in MRS broth.

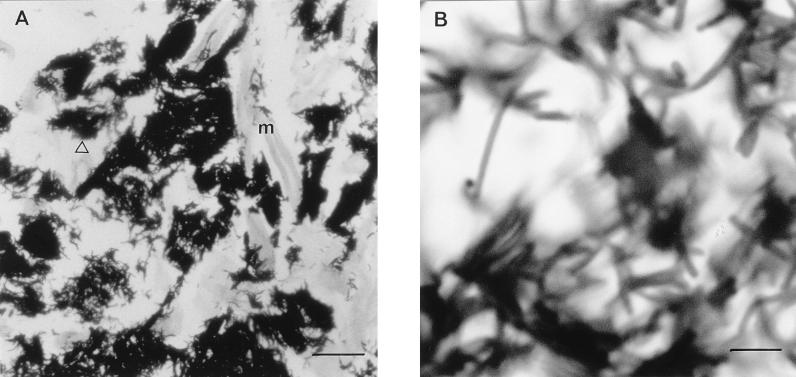

The results of light microscopy studies of L. acidophilus are presented in Fig. 3. These showed large latticed networks of organisms forming microcolonies between the cellulose fiber matrix. Similar microcolonies were seen with G. vaginalis. In addition, with G. vaginalis numerous free bacteria were seen to be adherent to the matrix.

FIG. 3.

Photomicrographs of thin sections of Sorbarod biofilms of L. acidophilus stained with the Gram stain. m, cellulose matrix; ▵, microcolony. (A) Bar, 40 μm. (B) Bar, 5 μm.

DISCUSSION

We have previously used the Sorbarod biofilm mode of growth as a model for investigating bacterial vaginosis. The system was used in the present investigation to study the antimicrobial susceptibilities of two key organisms associated with this condition and to compare the results with those of traditional susceptibility tests. The Sorbarod biofilm BEC and the effluent MBC were determined in media which gave optimal growth of the two organisms in the biofilms (11). For this reason the traditional tests were done in the same media, which was controlled by using the Etest on DST agar.

With G. vaginalis grown in BHI broth, the BEC was higher than the MBC obtained by the traditional tube MBC test with the exception of the values for clindamycin, to which the bacteria remained exquisitely sensitive. We consider that any pH changes would affect the results obtained with the biofilms less than they would affect those obtained by the tube tests. The maximum pH change occurred in an overnight broth culture, with a change from pH 7.4 for uninoculated BHI broth to pH 6.6 after overnight culture; effluent collected from an established biofilm for 1 h had a pH of 6.9. The organism in these biofilms was shown to be highly resistant to metronidazole. One criticism of this result may be that the conditions in the biofilm were not truly anaerobic, because the experiments had to be conducted in a standard incubator because of the equipment involved. However, other work in this laboratory (15) with the aerobic bacterium Pseudomonas aeruginosa indicates that this organism grows only on the exposed surfaces of the Sorbarod filter, whereas organisms such as G. vaginalis, L. acidophilus (11), and S. pneumoniae (2) grow throughout the biofilm. Also, the anaerobe Mobiluncus curtisii remains viable in these biofilms for at least 48 h under the same growth conditions (10a). This evidence indicates that reasonable anaerobic conditions exist within an established Sorbarod biofilm culture. In addition, in a study of the susceptibilities of 93 strains of G. vaginalis (8), the metronidazole MIC at which 50% of isolates are inhibited was determined to be 8 mg/liter. The values obtained in the present investigation by the tube MIC test and the Etest were at or below this value. The resistance to metronidazole shown in the present investigation may represent a characteristic feature of this biofilm mode of growth. Overall, the evidence presented for G. vaginalis clearly refutes the thinking that organisms in biofilms are less susceptible to antibiotics in general (3), as shown from the effect of clindamycin on this organism.

With L. acidophilus, useful information was obtained from the results of tests with the two different media used, BHI broth and MRS broth. In all cases the BEC was at least 16-fold greater with MRS broth than that achieved with BHI broth. In MRS broth the organism was highly resistant to erythromycin. There are suitable explanations for this. First, the organism achieved significantly higher titers in MRS broth than in BHI medium (11) (Fig. 2). In addition, as pointed out previously (8), erythromycin is less effective at lower pH, a fact that may compromise its activity in the acidic environment of the vagina. The lower pH of MRS broth (pH 6.2) than that of BHI broth (pH 7.4) before inoculation could explain the significant population of the organism that remains resistant to erythromycin in the biofilms in MRS broth. When lactobacillus was grown in BHI broth, the pH after overnight broth culture was 7.3, while that of the effluent collected from an established biofilm for 1 h was 6.9. In MRS broth, the pH values for the two specimens were 5.9 and 5.0, respectively. Lactobacilli have traditionally been considered tolerant to antibiotics (1). Comparison of the ratio of the BEC to the tube MBC shows that this tolerance is clearly enhanced in Sorbarod biofilms.

It is accepted that in vivo most bacteria grow as adherent biofilms; traditionally, bacteria in the biofilm mode of growth have been considered less susceptible to antibiotics (3). The use of the Sorbarod system in the present investigation indicates that no general rules regarding the antibiotic susceptibilities of microorganisms in the biofilm mode of growth can be made. G. vaginalis remained exquisitely sensitive to clindamycin both in broth and in biofilms. For the other antibiotics tested the general rule of reduced susceptibility may apply. It is worthwhile noting that for these agents the effluent MBC was greater than the equivalent tube MBC by at least a factor of 8. The organisms that elute continually off the biofilm as the biofilm planktonic bacteria exhibit the same degree of resistance as the organisms making up the adherent biofilm microcolonies (Fig. 3).

Many factors, such as growth conditions, nutrient supply, and the microenvironment, must contribute to the effect of even a single agent (12). The light microscopy studies with L. acidophilus (Fig. 3) indicated that the bacteria grow as adherent microcolonies in this biofilm system. Similar results have been obtained with G. vaginalis, and thus, the system can be regarded as producing a true biofilm. The Sorbarod biofilm system may be useful for investigating the interaction of bacteria (11). The work presented here indicates that it has a role in investigating the actions of antibiotics against organisms in the biofilm mode of growth. The information obtained may be of use in determining the optimum antibiotic to be used in complex ecological situations such as bacterial vaginosis. This is highlighted by the fact that the difference in the BEC of clindamycin for the lactobacillus and that for G. vaginalis is on the order of 4,000-fold when they were grown under optimal conditions.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

F. W. Muli is on sabbatical leave from the Moi University, Kikwit, Kenya. This leave is financed by a predoctoral scholarship from the World Bank, New York, N.Y.

We acknowledge the staff of the Department of Histopathology, Central Manchester Health Care Trust, for the preparation of the thin sections of the Sorbarod biofilms.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bayer A S, Chow A W, Conception N, Guze L B. Susceptibility of 40 lactobacilli to six antimicrobial agents with broad gram-positive anaerobic spectra. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1978;14:720–722. doi: 10.1128/aac.14.5.720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Budhani R K, Struthers J K. The use of Sorbarod biofilms to study the antimicrobial susceptibilities of a strain of Streptococcus pneumoniae. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1997;40:601–602. doi: 10.1093/jac/40.4.601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gander S. Bacterial biofilms: resistance to antimicrobial agents. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1996;3:1047–1050. doi: 10.1093/jac/37.6.1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hauth J C, Goldenberg R L, Andrews W W, Dubard M B, Copper R L. Reduced incidence of preterm delivery with metronidazole and erythromycin in women with bacterial vaginosis. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:1732–1736. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199512283332603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hillier S L, Nugent R P, Eshenbach D A, Krohn M A, Gibbs R S, Martin D H, Cotch M F, Edelman R, Pastorek J G, Rao A V, McNellis D, Regan J A, Carey J C, Klebanoff M A. Association between bacterial vaginosis and preterm delivery of low-birth weight infant. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:1737–1742. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199512283332604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hodson A E, Nelson S M, Brown M R M, Gilbert P. A simple in vitro model for growth control of bacterial biofilms. J Appl Bacteriol. 1995;79:87–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1995.tb03128.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Holt A, Brown D. Antimicrobial susceptibility testing. In: Hawkey P M, Lewis D A, editors. Medical bacteriology: a practical approach. Oxford, United Kingdom: IRL Press; 1989. pp. 167–194. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kharsany A B M, Hoosen A A, Van Den Ende J. Antimicrobial susceptibilities of Gardnerella vaginalis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1993;37:2733–2735. doi: 10.1128/aac.37.12.2733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mayaud R. Tackling bacterial vaginosis in developing countries. Lancet. 1997;350:530–531. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)22034-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McCarthy L R, Mickelsen P A, Smith E G. Antibiotic susceptibility of Haemophilus vaginalis (Corynebacterium vaginale) to 21 antibiotics. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1979;16:186–189. doi: 10.1128/aac.16.2.186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10a.Muli, F. W. Unpublished results.

- 11.Muli F W, Struthers J K. The growth of Gardnerella vaginalis and Lactobacillus acidophilus in Sorbarod biofilms. J Med Microbiol. 1998;47:1–5. doi: 10.1099/00222615-47-5-401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nichols W W. Biofilms, antibiotics and penetration. Rev Med Microbiol. 1991;2:177–181. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rosenstein I J, Morgan D J, Sheehan M, Lamont R F, Taylor-Robinson D. Bacterial vaginosis in pregnancy: distribution of bacterial species in different Gram stain categories of the vaginal flora. J Med Microbiol. 1996;45:120–126. doi: 10.1099/00222615-45-2-120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Spiegel C A. Bacterial vaginosis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1991;4:485–502. doi: 10.1128/cmr.4.4.485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wooster, S. L., and J. K. Struthers. Unpublished observations.