Abstract

The pharmacokinetics and tolerability of a new parenteral carbapenem antibiotic, biapenem (L-627), were studied in healthy elderly volunteers aged 65 to 74 years (71.6 ± 2.7 years [mean ± standard deviation], n = 5; group B) and ≥75 years (77.8 ± 1.9 years, n = 5; group C), following single intravenous doses (300 and 600 mg), and compared with those of healthy young male volunteers aged 20 to 29 years (23.0 ± 3.5 years, n = 5; group A). The agent was well tolerated in all three age groups. Serial blood and urine samples were analyzed for biapenem to obtain key pharmacokinetic parameters by both two-compartment model-dependent and -independent methods. The maximum plasma concentration and area under plasma concentration-versus-time curve (AUC) increased in proportion to the dose in all three groups. Statistically significant age-related effects for AUC, total body clearance, and renal clearance (CLR) were found, while elimination half-life (t1/2β) and percent cumulative recovery from urine of unchanged drug (% UR) remained unaltered (t1/2β, 1.51 ± 0.42 [300 mg] and 2.19 ± 0.64 [600 mg] h [group A], 1.82 ± 1.14 and 1.45 ± 0.36 h [group B], and 1.75 ± 0.23 and 1.59 ± 0.18 h [group C]; %UR, 52.6% ± 3.0% [300 mg] and 53.1% ± 5.1% [600 mg] [group A], 46.7% ± 7.4% and 53.0% ± 4.8% [group B], and 50.1% ± 5.2% and 47.1% ± 7.6% [group C]). A significant linear correlation was observed between the CLR of biapenem and creatinine clearance at the dose of 300 mg but not at 600 mg. The steady-state volume of distribution tended to be decreased with age, although not significantly. Therefore, the age-related changes in parameters of biapenem described above were attributable to the combination of decreased lean body mass and lowered renal function of the elderly subjects. However, the magnitude of those changes does not necessitate dosage adjustment in elderly patients with normal renal function for their age.

Biapenem, (1R,5S,6S)-2-[(6,7-dihydro-5H-pyrazolo[1,2-a] [1,2,4] triazolium-6-yl)]-thio-6-[(R)-1-hydroxyethyl]-1-methyl-carbapenem-3-carboxylate L-627, is a new parenteral carbapenem developed by Lederle (Japan), Ltd. It exhibits antibacterial activity against a wide range of gram-positive and -negative bacteria (14). It is also stable to human renal dehydropeptidase I and therefore does not require the coadministration of a dehydropeptidase I enzyme inhibitor (6).

Single and repeated intravenous doses of biapenem have been shown to be well tolerated in healthy young volunteers, with linear pharmacokinetics exhibited within the dosage range of 20 to 600 mg (9). In normal subjects, biapenem is cleared primarily by urinary excretion. The predominant concern in terms of adverse reactions to the prototype carbapenem antibiotic, imipenem/cilastatin, is the greater tendency to cause seizures than that of other β-lactams. The risk of producing a seizure is highly associated with inadequate dose adjustment in relation to renal function (1).

In general, it is accepted that adverse drug effects are more frequently encountered in the elderly. The heightened susceptibility to adverse reactions is due to a number of factors, including altered pharmacokinetic properties of many drugs (12, 15, 16). It is well recognized that many physiologic functions including renal function diminish with increasing age (3, 13). In consideration of these observations, full clarification of pharmacokinetic properties of biapenem in the aged is quite essential for its safe application to them.

In the present study, the pharmacokinetics of biapenem were investigated in an elderly population and compared with those of healthy younger subjects. Our results will aid physicians in adjusting the dosage of the new carbapenem antibiotic for this age group.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects and study protocols.

Before the implementation of this study, the research protocol and the consent form were reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of Shitoro Clinic, Hamamatsu, Japan. Volunteers were selected for enrollment in the study on the basis of physical examination, medical history, and clinical laboratory tests performed prior to the drug administration. In addition, elderly subjects were enrolled in the study on the basis of criteria such as being self-supporting and medically stable under restriction of other medications for 1 week prior to the beginning of study. Finally, 5 younger healthy male subjects (group A) aged 23.0 ± 3.5 years (mean ± standard deviation [SD]; range, 20 to 29 years) and weighing 59.4 ± 7.2 kg and 10 elderly subjects (three males and seven females) participated in the present study after giving their written informed consent. The elderly subjects were subdivided into two groups based on two age ranges, 65 to 74 years and ≥75 years, namely, group B (71.6 ± 2.7 years, 55.6 ± 7.5 kg of body weight, n = 5) and group C (77.8 ± 1.9 years, 56.5 ± 11.4 kg of body weight, n = 5). Caffeine-containing beverages and smoking were prohibited from 12 h before until 24 h after drug administration. Use of other medications was restricted from 7 days before until 24 h after drug administration.

The safety and pharmacokinetics were examined by single intravenous dosing of biapenem over 1 h. Biapenem was administered first at the dose of 300 mg and then at the dose of 600 mg at a 1-week interval. On each study day, biapenem was administered to the volunteers after overnight fasting. Venous blood samples (5 ml) were collected in heparinized tubes before (0 h) and 1, 1.25, 1.5, 2, 3, 5, 9, 12, and 24 h after the beginning of the 1-h intravenous administration. Urine samples were collected as voided just before administration, and at intervals of 0 to 2, 2 to 4, 4 to 6, 6 to 8, 8 to 12, and 12 to 24 h after the beginning of drug administration.

Plasma was immediately separated from the blood samples by centrifugation at 1,500 × g for 5 min under cooling. The plasma sample was mixed with the same volume of 1 M 3-(N-morpholino)propanesulfonic acid (MOPS) buffer (pH 7.0), immediately frozen in methyl alcohol with dry ice, and stored at −80°C until analyzed. The volume of urine sample from each time period was measured accurately. An aliquot (5 ml) was mixed with the same volume of 1 M MOPS buffer (pH 7.0), frozen in the same manner as the plasma sample, and stored at −80°C until analyzed.

All subjective and objective symptoms either observed by the investigators or reported by the subject spontaneously or in response to a direct question were noted. If any adverse experience occurred after the administration of each test drug, the subject was to be given appropriate treatment and close medical supervision. Causality and severity rating of clinical adverse experiences were determined.

Blood biochemistry and hematology tests, urinalysis, and an electrocardiogram were performed at the time of screening, prior to dosing, and at 24 h and at 7 days postdosing in association with each administration. Vital signs including body temperature and blood pressures were monitored just before and periodically up to 24 h after administration.

Analytical methods.

Concentrations of biapenem in plasma and urine samples were quantitated by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) in accordance with previously reported methods (9). The Shimadzu (Kyoto, Japan) HPLC system consisted of a pump (LC-6), an autosampler (SIL-6B), and a system controller (Chromatopac C-R6A) together with a UV detector (SPD-6AV; wavelengths of 300 and 310 nm for plasma and urine samples, respectively). An octyldecylsilane (ODS) analytical column (TSK gel ODS 80TM [Tosoh, Tokyo, Japan]; 4.6 mm [inside diameter] by 150 mm) was used. The mobile phases were a mixture of 0.1 M acetate buffer and acetonitrile (98.5:1.5, vol/vol) and a mixture of sodium 1-octanesulfate solution, acetonitrile, methanol, and acetic acid (480:110:12:3, vol/vol/vol/vol) for plasma and urine samples, respectively. The solution was filtered through a membrane filter (pore size, 0.45 μm) and degassed before use.

The HPLC system was operated at ambient temperature. The flow rates were 1.2 and 1.1 ml/min for plasma and urine samples, respectively. Plasma samples were diluted with 30% ammonium sulfate solution and centrifuged at 3000 rpm. As internal standards, 5-hydroxyindole-3-acetic acid and o-nitroacetanilide were used for plasma and urine samples, respectively. For plasma, the calibration curve was generated by measuring the plasma solution with the biapenem concentrations adjusted to 2.0, 4.9, 9.9, 19.7, 49.3, and 98.5 μg/ml. The calibration curve thus obtained was linear in this concentration range (r = 0.9998). Its coefficient of variation (CV) was 1.38%. The mean recovery (n = 6) of biapenem was 99.5%. The detection limit was 0.1 μg/ml in plasma. For urine, the calibration curve was generated by measuring the urine solution with the biapenem concentrations adjusted to 20.0, 50.1, 100.2, 200.4, 501.0, and 1,002.0 μg/ml. The calibration curve thus obtained was linear in this concentration range (r = 0.9999). The CV was 2.44%. The mean recovery (n = 6) of biapenem was 102.5%. The detection limit was 1.0 μg/ml in urine.

Pharmacokinetic analysis.

In the phase I studies using younger healthy subjects (9), concentrations of biapenem in plasma were fitted well to a two-compartment open model. For comparison, the time-sequential concentrations of drug in plasma for each subject were individually fitted to this model by employing the nonlinear least-squares computer program (MULTI) (17). The data apparently fitted better to a two-compartment model than to a one-compartment model with a lower Akaike’s information criterion value. The area under the plasma concentration-time curve from 0 h to infinity (AUC0–∞) was calculated by use of the trapezoidal rule until the time of the last quantifiable plasma concentration and then to infinity by using the quotient of the last measurable concentration to the terminal-phase rate constant, which was calculated by the above-mentioned curve fitting. The steady-state volume of distribution (Vss) was calculated by using the distribution volume of central compartment (Vc) and two intercompartmental microconstants (k12 and k21) as follows (11): Vss = Vc × [1 + (k12/k21)]. The maximum concentration in plasma (Cmax) was obtained from the simulated value at 1 h. Renal clearance (CLR) was calculated by dividing the amount of drug excreted into the urine by the AUC. Creatinine clearance (CLCR) was determined by dividing the amount of creatinine excreted into the urine in the 12 h prior to drug administration by the creatinine concentration in serum.

Statistics.

Means of the pharmacokinetic parameters were compared among the three age groups by analysis of variance, followed by Scheffe’s multiple comparison test.

RESULTS

Clinical results.

Biapenem was well tolerated by the subjects of all three groups. No adverse clinical effects were noted, and none of the subjects developed any laboratory abnormalities definitely attributable to the test drug.

Pharmacokinetic results.

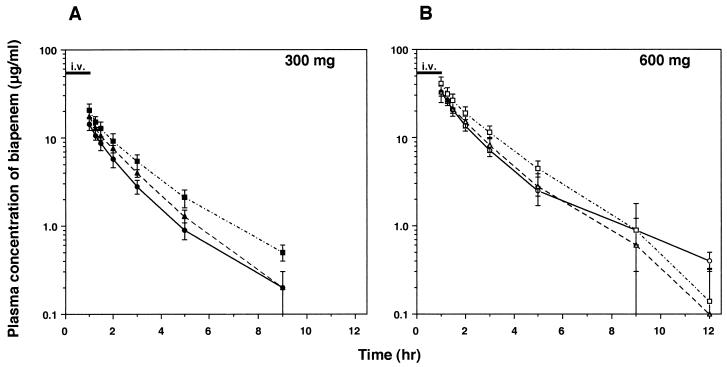

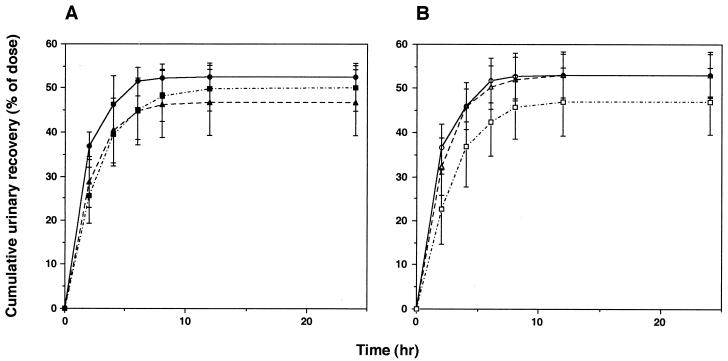

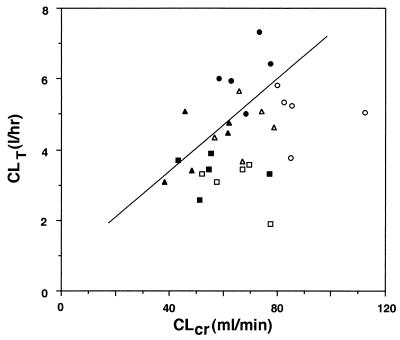

Among the three age groups, there was no significant difference in body weight (Table 1). Figures 1 and 2 illustrate the profiles of the biapenem concentration in plasma and of the recovery of unchanged drug from urine, respectively, as a function of time following intravenous administrations of 300 and 600 mg, the clinically expected doses in the elderly. The pharmacokinetic parameters are also shown in Table 1. When the three age groups were examined, statistically significant age-related effects were found for AUC0–∞ total clearance (CLT), and CLR, while the elimination half-life (t1/2β) remained unchanged. Recovery of unchanged drug from urine, expressed as percentages of 300- and 600-mg doses, also remained unaltered: group A, 52.6% ± 3.0% (300 mg) and 53.1% ± 5.1% (600 mg); group B, 46.7% ± 7.4% and 53.0% ± 4.8%; and group C, 50.1% ± 5.2% and 47.1% ± 7.6%. A significant linear correlation was observed between CLR of biapenem and CLCR at the dose of 300 mg (Fig. 3; Y = 0.782 + 0.0645X, r = 0.566, n = 15, P < 0.05) but not at the dose of 600 mg. The value of Vss tended to be decreased with age, although not significantly.

TABLE 1.

Pharmacokinetic parameters of a parenteral carbapenem, biapenem, in three age groups (A, B, and C)a

| Dose (mg) | Group | n | Age (yr) | Body wt (kg) | t1/2α (h) | t1/2β (h) | Vss (liter) | Cmax (μg/ml) | AUC0–∞ (μg · h/ml) | CLT (liters/h) | CLR (liters/h) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 300 | A | 5 | 23.0 ± 3.5 | 59.4 ± 7.2 | 0.467 ± 0.196 | 1.51 ± 0.42 | 17.7 ± 3.2 | 14.2 ± 2.2 | 26.6 ± 4.0 | 11.5 ± 1.8 | 6.14 ± 0.84 |

| B | 5 | 71.6 ± 2.7 | 55.6 ± 7.5 | 0.425 ± 0.304 | 1.82 ± 1.14 | 15.2 ± 4.1 | 17.4 ± 3.8 | 34.5 ± 5.0 | 8.8 ± 1.1b | 4.16 ± 0.87c | |

| C | 5 | 77.8 ± 1.9 | 56.5 ± 11.4 | 0.462 ± 0.277 | 1.75 ± 0.23 | 13.7 ± 2.7 | 20.2 ± 3.3b | 44.6 ± 6.4c,d | 6.8 ± 0.9c | 3.38 ± 0.50c | |

| 600 | A | 5 | 59.4 ± 6.9 | 0.539 ± 0.162 | 2.19 ± 0.64 | 17.1 ± 1.5 | 33.2 ± 2.7 | 66.1 ± 7.3 | 9.2 ± 0.9 | 5.04 ± 0.77 | |

| B | 5 | 55.9 ± 7.3 | 0.417 ± 0.274 | 1.45 ± 0.36 | 15.1 ± 2.7 | 33.8 ± 7.3 | 70.1 ± 15.8 | 8.9 ± 1.9 | 4.67 ± 0.76 | ||

| C | 5 | 56.8 ± 11.5 | 0.301 ± 0.137 | 1.59 ± 0.18 | 13.4 ± 3.1 | 40.2 ± 7.6 | 91.9 ± 15.0b | 6.7 ± 1.2b,d | 3.06 ± 0.67c,d |

Comparison was made among three age groups by analysis of variance, followed by Scheffe’s multiple comparison test. Values are means ± SDs.

Significantly different from value for group A (P < 0.05).

Significantly different from value for group A (P < 0.01).

Significantly different from value for group B (P < 0.05).

FIG. 1.

Time profile of plasma concentration of biapenem (L-627) after single intravenous administrations of 300 (A) and 600 (B) mg over 1 h in three age groups. Each symbol and error bar represents the mean ± SD. Symbols: circles, group A; triangles, group B; squares, group C (n = 5 for each group).

FIG. 2.

Cumulative recovery of biapenem from urine expressed as percentage of the dose, either 300 (A) or 600 (B) mg in three age groups. Each symbol and error bar represents the mean ± SD. Symbols: circles, group A; triangles, group B; squares, group C (n = 5 for each group).

FIG. 3.

Relationship between CLT of biapenem and CLCR. A significant, positive linear correlation between CLR of biapenem and CLCR was observed at the dose of 300 mg (symbols: •, group A; ▴, group B; ▪, group C; n = 5 for each group) (straight line, r = 0.556 [n = 15], P < 0.05). At the dose of 600 mg, no significant correlation was observed (symbols: ○, group A; ▵, group B; □, group C).

DISCUSSION

The data from the present study revealed that a new parenteral carbapenem, biapenem, was well tolerated in regimens using clinical doses relevant for all ages and possessed the following different pharmacokinetic properties in elderly subjects as compared with those in younger subjects. Biapenem showed statistically significant age-related effects in AUC, CLT, and CLR values, while it showed linear pharmacokinetics in both age groups and the t1/2β and percent cumulative recovery of unchanged drug from urine remained unchanged.

It is well recognized that subject age affects the disposition of many drugs because of physiological changes associated with aging. Organ functions in the elderly generally decline as a result of advancing age. For example, cardiac output decreases by 30 to 40% between the ages of 25 and 65 years and the glomerular filtration rate as expressed by CLCR declines progressively with age. Body composition also changes with aging. Total body water and lean body mass are lower in the elderly, both in absolute terms and as percentages of body weight. There is an age-related increase in adipose tissue as a fraction of body weight of 9 to 49% with a concomitant reduction in lean body mass and body water (5). The decrease in the proportion of lean body mass per unit of body weight has been shown to alter the distribution volumes of various drugs (4). In accordance with the above-mentioned observations, such age-related alterations in pharmacokinetics as increases in t1/2β and in concentration of drug in plasma are encountered for various types of antimicrobial agents. In fact, we have reported age-related changes in the pharmacokinetic properties of two fluoroquinolones, balofloxacin and grepafloxacin, whose main excretion routes are the renal and hepatic routes, respectively (7): delayed and diminished recovery of balofloxacin from urine, attributed to the reduced renal function of the elderly subjects, and increases in Cmax and AUC of grepafloxacin, attributed to a decrease in Vss in the elderly.

In the present study, a significant linear correlation was observed between the CLR of biapenem and CLCR, although only at the dose of 300 mg, and Vss tended to be decreased with age, although not significantly. CLCR was calculated on the basis of urine collection for 12 h during the night instead of over a whole day (24 h). Therefore, the intra- and interindividual variabilities in urine volume during the night might have had a relatively large influence on the accuracy of calculating CLCR and, further, on the result that a significant linear correlation between CLR of biapenem and CLCR was present and absent at the doses of 300 and 600 mg, respectively. At the dose of 600 mg, on the other hand, the elderly subjects showed significantly lower values of CLCR (68.5 ± 8.5 and 64.8 ± 10.0 ml/min for groups B and C, respectively) than the younger ones (89.2 ± 13.1 ml/min for group A) before drug administration (group A versus group B, P < 0.01; group A versus group C, P < 0.01). In light of these observations together with the above-mentioned physiological changes in relation to aging, the age-related decreases in AUC, CLT, and CLR of biapenem could be attributed to the combination of decreased lean body mass and lowered renal function in the elderly subjects. Since t1/2β and percent cumulative recovery of unchanged drug from urine, however, remained unaltered, it is not expected that the accumulation of biapenem would result when administered at 8- to 12-h intervals, in other words, two or three times daily.

When a β-lactam antibiotic is prescribed for an elderly patient, precautions should be taken with regard to age-related changes in pharmacokinetic properties. However, in consideration of the safety and tolerance profiles of β-lactam antibiotics including carbapenem, the magnitude of age-related changes observed in the pharmacokinetics of biapenem does not necessitate dosage adjustment in elderly patients with renal function normal for their age.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported in part by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Ministry of Education, Science and Culture in Japan.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alvan G, Nord C E. Adverse effects of monobactams and carbapenem. Drug Saf. 1995;12:305–313. doi: 10.2165/00002018-199512050-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barbhaiya R H, Knupp C A, Pittman K A. Effects of age and gender on pharmacokinetics of cefepim. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1992;36:1181–1185. doi: 10.1128/aac.36.6.1181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Crome P, Flanagan R J. Pharmacokinetic studies in elderly people. Are they necessary? Clin Pharmacokinet. 1994;26:243–247. doi: 10.2165/00003088-199426040-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Crowley J, Echaves S, Cusak B, Vestal R. The elderly. In: Williams R, Brater D, Mordenti J, editors. Rational therapeutics: a clinical pharmacologic guide for the health professional. New York, N.Y: Marcel Dekker, Inc.; 1990. pp. 141–174. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Forbes G B, Reina J C. Adult lean body mass declines with age: some longitudinal observations. Metabolism. 1970;19:653–663. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(70)90062-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hikida M, Kawashima K, Nishiki K, Furukawa Y, Nishizawa K, Saito I, Kuwao S. Renal dehydropeptidase-I stability of LJC 10,627, a new carbapenem antibiotic. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1992;36:481–483. doi: 10.1128/aac.36.2.481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kozawa O, Uematsu T, Matsuno H, Niwa M, Nagashima S, Kanamaru M. Comparative pharmacokinetic studies of two newer fluoroquinolones, balofloxacin and grepafloxacin, in elderly subjects. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:2824–2828. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.12.2824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meyers B R, Wilkinson P. Clinical pharmacokinetics of antibacterial drugs in the elderly. Implications for selection and dosage. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1989;17:385–395. doi: 10.2165/00003088-198917060-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nakashima M, Uematsu T, Ueno K, Nagashima S, Inaba H, Nakano M, Kosuge K, Kitamura M, Sasaki T. Phase I study of L-627, biapenem, a new parenteral carbapenem antibiotic. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther Toxicol. 1993;31:70–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Norrby S R. Carbapenem. Med Clin N Am. 1995;79:745–759. doi: 10.1016/s0025-7125(16)30037-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Regazzi M B, Rondanelli R, Calvi M. The need for pharmacokinetics protocols in special cases. Pharmacol Res. 1993;27:21–31. doi: 10.1006/phrs.1993.1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rowland M, Tozer T N. Clinical pharmacokinetics: concepts and applications. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Lea & Febiger; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Salom I L, Davis K. Prescribing for older patients: how to avoid toxic drug reactions. Geriatrics. 1995;50:37–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sloan R W. Principles of drug therapy in geriatric patients. Am Fam Physician. 1992;45:2709–2718. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ubukata K, Hikida M, Yoshida M, Nishiki K, Furukawa Y, Tashiro K, Konno M, Mitsuhashi S. In vitro activity of LJC 10,627, a new carbapenem antibiotic with high stability to dehydropeptidase I. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1990;34:994–1000. doi: 10.1128/aac.34.6.994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Walker J, Wynne H. Review: the frequency and severity of adverse drug reactions in elderly people. Age Ageing. 1994;23:255–259. doi: 10.1093/ageing/23.3.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yamaoka K, Tanigawara Y, Nakagawa T, Uno T. A pharmacokinetic analysis program (MULTI) for microcomputer. J Pharmacobio-Dyn. 1981;4:879–885. doi: 10.1248/bpb1978.4.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]