Abstract

Purpose:

Suicide and suicidal ideation are topics that have a long but limited history in stuttering research. Clinicians and clinical researchers have discussed personal and therapeutic experiences with clients who have attempted suicide, died by suicide, or struggled with suicidal thoughts. This study sought to (a) explore the occurrence of suicidal ideation in a sample of adults who stutter; (b) evaluate the relationship between adverse impact related to stuttering and suicidal ideation; and (c) document respondents' thoughts related to suicide, stuttering, and their intersection.

Method:

One hundred forty adults who stutter completed the Suicide Behavior Questionnaire–Revised (SBQ-R). Of these, 70 participants completed the Perseverative Thinking Questionnaire (PTQ), and 67 completed the Overall Assessment of the Speaker's Experience of Stuttering (OASES). Participants who indicated at least some tendency for suicidal thoughts on the SBQ-R (n = 95) were then asked a set of follow-up questions to explore their experiences of suicidal ideation related to stuttering.

Results:

Quantitative data indicated that the majority of adults who reported experiencing suicidal ideation associated these experiences with stuttering (61.2%, n = 59). Individuals with higher Total Scores on the PTQ and OASES were predicted to experience significantly higher rates of suicidal ideation and, in particular, a higher likelihood of having more frequent suicidal ideation in the past year. Qualitative analyses revealed that suicidal ideation intersects meaningfully with the experience of stuttering.

Conclusions:

Data from this study highlight the importance of considering broader life consequences of stuttering that some adults may experience, including suicidal ideation. By being cognizant that clients may develop such thoughts, speech-language pathologists can play a valuable role in identifying and providing necessary support for at-risk individuals.

Supplemental Material:

The term adverse impact as it relates to stuttering commonly refers to the negative personal reactions (e.g., negative thoughts, feelings, and behaviors) and the broader speech- or communication-related limitations that a person who stutters experiences in daily life (Tichenor & Yaruss, 2019b; Yaruss, 1998; Yaruss & Quesal, 2006, 2016, 2004). Adverse impact that takes the form of negative personal reactions has been well specified in stuttering research. For example, the behavioral reactions associated with stuttering include more commonly observed stuttering behaviors, such as repetitions, prolongations, or blocks, as well as the more difficult-to-observe behaviors related to physical tension, struggle, or avoidance (Constantino et al., 2017; B. Murphy, Quesal, et al., 2007; Tichenor et al., 2017; Tichenor & Yaruss, 2019a). Many people who stutter also experience negative feelings, including guilt, shame, embarrassment, anger, resentment, hopelessness, and fear (Beilby, 2014; Brundage et al., 2017; Corcoran & Stewart, 1998; Daniels & Gabel, 2004; Sheehan, 1953, 1970; Tichenor & Yaruss, 2018; Van Riper, 1982; Yaruss & Quesal, 2006). Negative thoughts are also commonly experienced. These may relate to anxiety (Alm, 2014; Craig et al., 2003; Iverach et al., 2018) or to anticipation that a moment of stuttering or a difficult speaking situation might soon be experienced (Bloodstein, 1958, 1972, 1975; Brocklehurst et al., 2013; Jackson et al., 2015; Messenger et al., 2004). More broadly, negative thoughts may also take the form of repetitive negative thinking (RNT), in which a person habitually and continually ruminates on difficulties related to their life situation (Tichenor & Yaruss, 2020b). Thus, there are many facets to negative personal reactions related to the stuttering condition, and a person's lived experience of stuttering strongly influences how, why, and to what degree these negative reactions develop (Tichenor & Yaruss, 2018; Tichenor, Herring, et al., 2022).

The nature and degree of adverse impact a person experiences are not just a function of internalized reactions; broader forms of adverse impact can also be experienced, and these may be strongly influenced by a person's environment. For example, research evidence has shown that many people who stutter experience stigma (Boyle, 2013, 2018), have difficulty forming and maintaining personal or romantic relationships (Van Borsel et al., 2011), experience occupational role entrapment (Gabel et al., 2004; McAllister et al., 2012), have decreased chances of employment opportunities (Gerlach et al., 2018; Klein & Hood, 2004; Palasik et al., 2012), experience financial hardship (Blumgart et al., 2010), and undergo employment loss or social rejection (Constantino et al., 2017). Though many individuals who do not stutter also deal with these issues, the fact that each of these hardships appears to be related to a single origin (stuttering) highlights the particular challenges that are often associated with stuttering. The combined effects of these negative life experiences may greatly increase the burden of living as a person who stutters, as it would for any person dealing with such negative life circumstances.

Unfortunately, other broader life consequences related to stuttering remain underspecified in stuttering research. This gap can be acutely seen in the study of suicidal ideation, a topic that highlights the damaging consequences of living with stuttering for some speakers. Although suicidal ideation has been discussed by speech-language pathologists (SLPs; see Kuster et al., 2013), it has been the subject of relatively little research over past decades (see Briley et al., 2021, as one recent exception). The purpose of this study is to bring additional evidence to bear in an attempt to address that gap by exploring the occurrence and nature of suicidal ideation in a sample of adults who stutter. This study also examines suicidal ideation in the context of the broader impact of stuttering that people might experience.

Suicidal Ideation and Stuttering

The term suicidal ideation refers to thoughts, communication, and behaviors related to the intention to die (Van Orden et al., 2010). Suicidal ideation is categorically different from suicide, which is “reserved for those cases in which a suicide attempt results in death” (Van Orden et al., 2010, p. 576). In 2019, suicide accounted for 700,000 deaths worldwide, equating to 1.3% of all deaths and ranking as the 17th leading cause of deaths that year (World Health Organization [WHO], 2019). Suicide was also the second leading cause of death in adolescents and young adults aged 10–34 years in the United States in 2019 (National Institute of Health, 2019). Risk for suicide and/or suicidal ideation is often greater in clinical populations, including people with anxiety disorders (Sareen et al., 2005), depression (Miranda & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2007), autism spectrum disorder (Hedley et al., 2018), attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD; Taylor et al., 2014), traumatic brain injury (Madsen et al., 2018), dementia (Draper et al., 2010), and acquired language impairments (Carota et al., 2016; Costanza et al., 2021). Given the connections between stuttering and anxiety (see Iverach & Rapee, 2014), depressive thoughts (Briley et al., 2021; Tichenor & Yaruss, 2019a, 2020b), and concomitant conditions such as ADHD (Druker et al., 2019; Tichenor et al., 2021), it is particularly necessary to study suicidal ideation in the population of people who stutter.

In 2013, Kuster et al. presented a panel discussion at the annual convention of the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association (ASHA) in which experienced and expert SLPs discussed interactions with clients who stutter who had either attempted or died by suicide (Kuster et al., 2013). The panelists highlighted the important role that SLPs can take in counseling and referring clients with suicidal ideation to appropriate mental health professionals. Other clinicians have similarly shared personal experiences with clients who have expressed suicidal thoughts or ideation in therapy (see Kuster, 2012, for discussion). Though some have expressed a hesitancy to discuss and explore this topic for fear of discouraging SLPs from working with individuals who stutter (e.g., Fraser, 2014), others believe that further exploration of suicidal ideation in people who stutter is necessary given the clear clinical applicability and grave outcomes, both psychologically and physically (Briley et al., 2021; Kuster, 2012; Kuster et al., 2013).

The study of suicidal ideation and stuttering has a relatively long but quite limited history in the field of stuttering research. Deal (1982) presented a case study of a 28-year-old adult who had attempted suicide after a sudden onset of stuttering. Hays and Leigh Field (1989) followed the diagnoses of manic depression and stuttering in three families across five generations. They found that 50% of the people with manic depression in these families also stuttered, whereas only 16% of people in these families who did not have manic depression stuttered; four individuals who had manic depression and stuttered died by suicide. In addition to these case reports, some qualitative studies have shown that suicidal thoughts can occur in people who stutter. Corcoran and Stewart (1998) included a statement from one of their seven participants, who stated, “I was just at the end of my rope…. I remember feeling suicidal” (p. 261). Recently, Briley et al. (2021) found a significant association between males who stutter and suicidal ideation in a large national health survey of adolescents. Although these reports provide glimpses into the potential relationships between stuttering and suicidal ideation, more information about the specific nature of this relationship is needed so that SLPs can be appropriately prepared to address this aspect of the adverse impact of stuttering in their clients.

The importance of investigating suicidal ideation in people who stutter is made apparent by considering research findings from outside of speech-language pathology. For example, RNT, which is the process of engaging in recurrent, habitual, negatively valenced thoughts that develops as a person fails to achieve their life goals due to real or perceived shortcomings (Ehring et al., 2011; Martin et al., 1993; Nolen-Hoeksema, 2004; Watkins, 2008). RNT is significantly associated with depression (Kuehner & Weber, 1999; Nolen-Hoeksema, 2004; Nolen-Hoeksema et al., 2008), and depression, in turn, is significantly associated with suicidal ideation (Chan et al., 2009; Miranda & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2007; Morrison & O'Connor, 2008; Surrence et al., 2009). Recent research evidence has more directly linked increased RNT with suicidal ideation (Ram et al., 2020; Rogers & Joiner, 2017). Our own recent research has shown that RNT develops in many adults who stutter as they cope with the experience of stuttering; those adults who stutter who engage in RNT to a higher degree also experience significantly more adverse impact in their lives related to stuttering (Tichenor & Yaruss, 2020b). This suggests that people who stutter who engage in RNT more frequently and/or experience greater adverse impact related to stuttering may be at higher risk for suicidal ideation.

Other aspects of living with stuttering may also lead a person to engage in suicidal ideation. According to the interpersonal theory of suicide (Van Orden et al., 2010), one recent and prominent theory of how suicidal ideation develops, the desire for suicide occurs as a result of the interaction of “thwarted belonginess” and “perceived burdensomeness” (p. 581). The concept of thwarted belonginess is strongly related to social isolation, which is also one major predictor of suicidal ideation (Van Orden et al., 2010). Thwarted belonginess may arise due to multiple factors, such as loneliness and a lack of care or support, as well as emotional or physical abuse, losing loved ones, social withdrawal, poor family life, and disconnection from friends or family. Perceived burdensomeness generally arises due to feelings of distress, including those feelings associated with homelessness, incarceration, unemployment, physical illness, or feeling unwanted. Importantly, perceived burdensomeness can also arise from feelings of self-hatred, including low self-esteem, self-blame, anger, and resentment that individuals feel toward themselves. Van Orden et al. (2010) hypothesized that the interaction between thwarted belonginess and perceived burdensomeness can create a desire for suicide.

Although these specific terms have not been widely used in the existing stuttering literature, a review of findings pertaining to the overall experience of stuttering shows that these concepts are directly relevant to the experience of people who stutter. As noted, many people who stutter experience negative affective, behavioral, and cognitive reactions to their stuttering, and these reactions can be heavily influenced by external factors. These reactions develop as a person lives life dealing with the stuttering condition; the negative valence of their reactions is reinforced and increased by ongoing negative experiences (Tichenor & Yaruss, 2019b). Indeed, personal stories and qualitative research suggest that at least some people who stutter develop feelings of self-hatred and frustration; as a result, they may experience internalized stigma and decreased self-esteem (Ahlbach & Benson, 1994; Boyle, 2013, 2016; Boyle & Fearon, 2018; Kuster et al., 2013; Tichenor & Yaruss, 2018, 2019b). A lack of social support is also significantly associated with experiencing more negative affective, behavioral, and cognitive reactions (Tichenor & Yaruss, 2019a). Thus, people who experience adverse impact related to stuttering (negative personal reactions, negative environmental influences, or both) may develop both thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness, and this can put them at increased risk for suicidal ideation.

Purposes of This Study

Although a growing body of research continues to highlight various ways that stuttering can cause adverse impact on people's lives, the field is only beginning to explore broader forms of adverse impact. To further the field's understanding of this critical topic, this mixed-method study sought (a) to examine suicidal ideation in a sample of adults who stutter using a standard and established screening form for suicidal ideation, the Suicide Behavior Questionnaire–Revised (SBQ-R; see Osman et al., 2001); (b) to evaluate the relationships between adverse impact related to stuttering, RNT, and suicidal ideation in adults who stutter; and (c) to qualitatively evaluate respondents' thoughts relating to suicide, stuttering, and their intersection, to inform future research studies and clinical intervention in this area. It was hypothesized that adults who experience higher levels of adverse impact related to stuttering or who engage more frequently in RNT would report higher rates of suicidal ideation.

Method

Participants and Survey Procedures

This study involved a mixed-methods analysis of both quantitative and qualitative data from 140 adults (M age = 37.79, SD = 15.34) who stutter, as confirmed by self-report. Note that self-report was considered to be appropriate for this study because it was necessary to understand the experiences of those who identify themselves as living with stuttering rather than relying on listener-based or perceptual criteria that may not reflect the speaker's personal identity (see Tichenor, Constantino, et al., 2022, for discussion). Most of the participants reported that they had previously received therapy for stuttering (106/140, 75.7%); fewer reported that they had participated in self-help/support for stuttering (56/140, 40.0%). The sample of participants contained approximately twice as many men as women, identified mostly as White (75.7%), were highly educated (66.4% had college or postgraduate degree), and were from the United States (66.4%). Because suicidal ideation is also strongly associated with depression and anxiety (Chan et al., 2009; Miranda & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2007; Morrison & O'Connor, 2008; Sareen et al., 2005; Surrence et al., 2009), all participants were asked to self-report concomitant clinical diagnoses related to depression or anxiety. Of the participants reporting, 27.1% of the sample (n = 38) self-reported a clinical diagnosis of anxiety or depression. Table 1 contains detailed demographic information, including age, sex, gender, race, ethnicity, highest educational level, and country of origin, for those participants who elected to provide this information. Note that some demographic data were missing for subjects who chose not to provide this information, as all survey items and questions in the study were optional.

Table 1.

Demographic data.

| Demographic variable | Adults who stutter, n = 140 |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| M (SD) | 37.79 (15.34) |

| Range, min–max | 63, 18–71 |

| Sex | |

| Female | 43 (30.7%) |

| Male | 84 (60.0%) |

| Prefer not to say/missing data | 13 (9.3%) |

| Gender | |

| Female | 43 (30.7%) |

| Male | 80 (57.1%) |

| Nonbinary/third gender | 2 (1.4%) |

| Prefer not to say/missing data | 15 (10.7%) |

| Racial category | |

| American Indian or Alaskan Native | 0 (0.0%) |

| Asian | 5 (3.6%) |

| Black or African American | 3 (2.1%) |

| Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander | 1 (< 1.0%) |

| White | 106 (75.7%) |

| Mixed/Other | 10 (7.1%) |

| Prefer not to say/missing data | 14 (10.0%) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Hispanic or Latinx | 8 (5.7%) |

| Not Hispanic or Latinx | 114 (80.1%) |

| Prefer not to say/missing data | 18 (12.9%) |

| Highest education experiences (having college or postgraduate degree) | |

| Yes | 93 (66.4%) |

| No | 17 (22.1%) |

| Prefer not to say/missing data | 16 (11.4%) |

| Self-reported depression or anxiety clinical diagnosis | |

| Yes | 38 (27.1%) |

| No | 69 (49.3%) |

| Prefer not to say/missing data | 33 (23.6%) |

| Country/continent of origin | |

| United States of America | 93 (68.6%) |

| North America (not USA) | 3 (2.1%) |

| Europe | 13 (9.2%) |

| South America | 0 (0.0%) |

| Asia | 9 (6.4%) |

| Africa | 1 (< 1.0%) |

| Australia (or Oceania) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Prefer not to say/missing data | 21 (15.0%) |

Note. min = minimum; max = maximum.

All participants completed the SBQ-R (Osman et al., 2001). The SBQ-R is a widely used self-report screener of suicidal risk (Batterham et al., 2015). It assesses suicidal ideation using four questions: (a) Have you ever thought about or attempted to kill yourself? (b) How often have you thought about killing yourself in the past year? (c) Have you ever told someone that you were going to commit suicide, or that you might do it? (d) How likely is it that you will attempt suicide someday? The first question assesses a person's lifetime suicidal ideation. The second question assesses the frequency of suicidal ideation in the past year. The third and fourth questions assess the threat or likelihood of future suicide. The participant responds to these questions via Likert scales, where the number of scale responses varies between questions. The SBQ-R has been shown to be a reliable and valid measure of suicidal risk across clinical and nonclinical samples (Osman et al., 2001). We scored the SBQ-R according to instrument instructions to form an SBQ-R Total Score, where higher scores indicate a greater risk of suicide. The SBQ-R Total Score ranges from 3 to 18, with higher scores indicative of increased suicidal risk (see Osman et al., 2001). This total score was the primary outcome variable of interest in the regression equations described below.

The Perseverative Thinking Questionnaire (PTQ; Ehring et al., 2011) was used to measure a person's tendency to engage in RNT. The PTQ is a transdiagnostic measure of RNT, which has been validated in both clinical and nonclinical populations and which has been shown to significantly predict disorder-specific RNT in depression and anxiety (Ehring et al., 2011). RNT as measured by the PTQ has also been shown to significantly predict suicidal ideation (Teismann & Forkmann, 2017). The PTQ contains 15 questions that evaluate intrusive, repetitive, and negative thoughts in a person's life. Participants respond to each item via a Likert frequency scale (never, rarely, sometimes, often, almost always), which correspond to the numeric values 0–4. PTQ Total Scores are formed by summing all 15 items. The PTQ Total Score was used in all regression equations described below.

The Overall Assessment of the Speaker's Experience of Stuttering (OASES; Yaruss & Quesal, 2006, 2016) was used to assess the impact of stuttering on each participant's life. The OASES is based on the WHO's International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF; WHO, 2001); it asks people who stutter about their reactions to stuttering, how much stuttering negatively impacts their communication in daily situations, and how much their stuttering negatively affects their quality of life. The OASES-A (the adult version for people aged 18 years and older), which has been shown to be a reliable and valid measure of the adverse life impact of stuttering, was scored in accordance with instructions. The OASES Total Score was used in all regression equations described below.

Of the 140 adults who stutter who completed the SBQ-R, 70 participants completed the PTQ, and 67 completed the OASES-A. Of those adults who completed the PTQ and OASES-A, 56 completed both measures. The fact that more participants completed the SBQ-R than the other measures is not surprising, given that participants had the option of completing as many survey instruments as they wished and that recruitment for this study was accomplished primarily by advertising the study as focusing specifically on suicidal ideation. Of the 140 adults who completed the SBQ-R, 49 are unique to this study and have not participated in our previous survey work exploring individual differences in the experiences of adults who stutter (Tichenor & Yaruss, 2020a, 2021; Tichenor et al., 2021; Tichenor, Walsh, et al., 2022). Participants who indicated at least some tendency for suicidal thoughts on the SBQ-R (i.e., they did not respond no or never to any of the questions) were asked a set of follow-up questions created by the authors to explore the ways in which their experience of suicidal ideation might be related to their stuttering. The follow-up questions were as follows: Question 1: Have these thoughts related to suicide changed over time since they first started? Question 2: What has helped you manage or cope with these thoughts and feelings related to suicide? Question 3: What triggers these thoughts and feelings related to suicide in your life? Participants who indicated at least some degree of suicidal risk on the SBQ-R were also asked to respond to the following two questions: Question 4: If you experienced any of these thoughts related to suicide, to what extent do you think that the thoughts are related to your stuttering? Question 5: What age did you first have these thoughts related to suicide? This first stuttering-specific question asked participants how related these thoughts were via a 5-point Likert agreement scale: strongly related, related, neither related or not related, not related, strongly not related; there was also an option for respondents to select “not sure.” The age-related question was numeric.

Finally, given the seriousness of the topic addressed in this project, the survey also included statements alerting all participants to the US National Suicide Prevention Lifeline (https://988lifeline.org), which provides free and confidential support for people in distress via phone or online chat. The way in which these questions were asked was deemed to be appropriate, based on research on suicidal ideation showing that talking about suicide and experiences related to suicide decreases suicidal thoughts (see Blades et al., 2018, for reviews). Throughout the study, the researchers sought to ensure that the topic was handled in a sensitive and supportive manner.

Qualtrics surveys were built for all of these questions, measures, and demographic questions, and all data were collected remotely via the Internet (Qualtrics, 2021). Prior to wide recruitment, the follow-up questions were piloted with approximately 20 adults who stutter to ensure that the questions were applicable, answerable, and not overly uncomfortable for participants to answer. Specifically, feedback was sought regarding the appropriateness of the questions, the language used, and whether respondents thought that other questions captured their experiences related to suicide and stuttering. Only minimal changes to the original wording of the questions were required as a result of this pilot testing. Participants were then recruited based on participation in past studies as well as a mixture of snowball and convenience sampling (i.e., personal contacts of the authors, SLPs, university clinics, and social media). Because respondents were encouraged to share the recruitment information with as many adults who stutter who may have wanted to participate, response rates cannot be calculated. For free-response questions, participants were asked to provide as much detail as possible. This study was a part of a larger series of studies investigating individual differences in the experience of stuttering (Tichenor & Yaruss, 2019a, 2019b, 2020a, 2020b, 2021; Tichenor et al., 2021; Tichenor, Walsh, et al., 2022), but data from this study have not been published in a prior manuscript. This study has been deemed exempt from institutional review by the Michigan State University Human Subjects Research Protection Office under statute 45 CFR 46.101(b) 2 of the Federal Policy for the Protection of Human Subjects. All participants provided informed consent prior to participation in the study, all were informed that they could skip any question they elected not to answer, and all were informed that they could stop participating (close any survey) at any time once started.

Quantitative Data Analysis

Multiple R packages were used for data manipulation, analysis, and visualization (Kassambara, 2020; Mazerolle, 2020; Revelle, 2022; Wickham, 2016, 2019). Internal consistency measures on the SBQ-R, PTQ, and OASES were calculated for data collected in this study. Internal consistency was good to excellent for the three PTQ factors (core features of RNT: α = .92; unproductiveness of RNT: α = .76; mental capacity captured by RNT: α = .87), the SBQ-R (α = .81), and for the four sections of the OASES (general information: α = .87; reactions to stuttering: α = .95; communication in daily situations: α = .93; quality of life: α = .93).

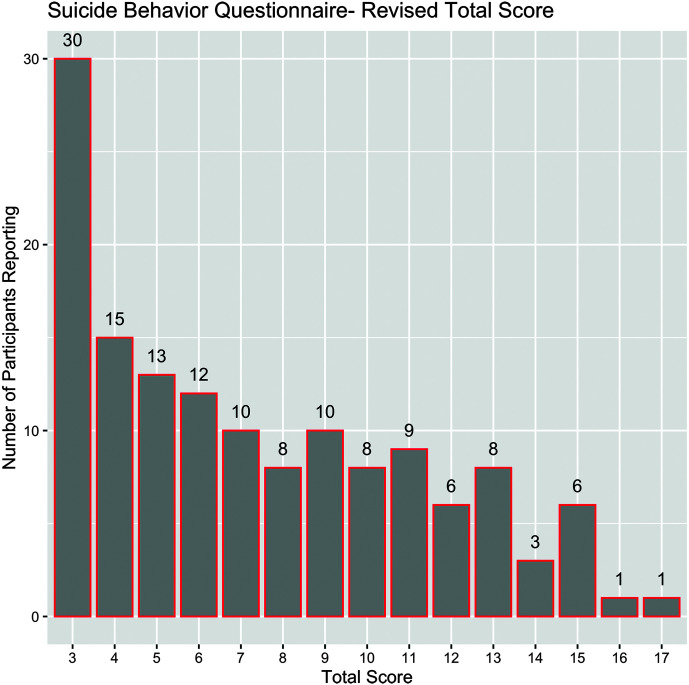

Prior research using the SBQ-R has identified cutoff scores validated for screening both clinical (psychiatric) and nonclinical samples where suicidal ideation was known (Osman et al., 2001). These cutoff scores show a high degree of correct identification for screening suicide risk in clinical (SBQ-R = 7; sensitivity = 87%; specificity = 93%) and nonclinical (SBQ-R = 8; sensitivity = 83%; specificity = 96%) populations. We did not statistically predict these cutoff values or explore relationships between participants who screened positive or negative for suicidal ideation. As discussed below in the Limitations and Future Directions section, such results must be interpreted with caution due to the possibility of selection bias; however, the data reported accurately reflect the responses and reported experiences of these 140 adults who stutter. Thus, we present our raw data in this study in Figure 1 to increase transparency and for comparison to future studies.

Figure 1.

The raw Suicide Behavior Questionnaire–Revised Total Scores from adults who stutter are plotted by number of adults with each total score.

Two linear regression equations were built to determine whether PTQ Total Score or OASES Total Score was predictive of SBQ Total Score. Two separate linear regression equations rather than one combined equation with an interaction term were chosen due to the number of PTQ and OASES data points collected in the study. Because each model only contained a single predictor, multicollinearity was not assessed. Both PTQ and OASES Total Scores were investigated for linearity, normality of residuals, homoscedasticity, and the presence of influential values via diagnostic plots in accordance with the assumptions of linear regression. Diagnostic plots indicated that the predictor and outcome variables in each model showed a linear relationship that only deviated in the extreme tails. All errors were determined to be normally distributed, with only slight deviations of normality in the upper and lower tails. Both PTQ and OASES Total Score demonstrated residuals that had a constant variance (homoscedasticity) and independence of error terms (i.e., no observation was more than 3 times the mean; see Cook, 1979). See Supplemental Material S1 for more information on diagnostic plots. Data were deleted listwise for regression equations where SBQ-R data were missing. This cautious approach was selected because listwise deletion is unbiased when the probability of complete cases is independent of the outcome variable (Bartlett et al., 2014; Newman, 2014; White & Carlin, 2010).

Ordered logistic regression (ordered logit/proportional odds model) was performed to determine the likelihood of a person indicating more frequent thoughts about suicide in the past year (recent suicidal ideation) as a function of degree of RNT (PTQ Total Score) or adverse impact related to stuttering (OASES Total Score). The question on the SBQ-R investigating recent suicidal ideation was chosen a priori given that the other questions are less temporally associated with a person's current mental state. Different equations were built for each predictor. Ordered logistic regression was selected because it is a useful method for predicting Likert-based responses while accounting for the ordered nature of the outcome variable (Williams, 2006, 2016). For both equations, the assumption of parallel lines (proportional odds assumption) was tested using the likelihood-ratio test of cumulative link models (Christensen, 2019). The assumption was met for both models because there was no significant difference between each model and a null model at p < .01 (Allison, 1999).

Qualitative Data Analysis

Thematic analysis principles were used to analyze all qualitative data in this study (Boyatzis, 1998; Braun & Clarke, 2006; Creswell, 2013); these data were analyzed using RQDA (Huang, 2016), a qualitative analysis software in R (R Core Team, 2022). The iterative processes began with the creation of separate data files that contained the responses for each open-ended question described above. The questions were analyzed separately given that they were distinct in meaning, each addressing different aspects of the experience of suicidal ideation. Answers to the individual questions were first read broadly for a general understanding. In subsequent rereadings, code categories that were descriptors of meaning were attached to the statements. Through numerous iterations of rereadings, these code categories were formed into proto-themes and, eventually, themes, as meaning became clearer. Illustrative examples of these themes are given in the results “bring in the voice of the participants” and to provide evidence in support of the themes (Creswell, 2013, p. 219). Because qualitative data in this study come from three predetermined questions, as opposed to a more generalized questions aimed at eliciting an overall experience as commonly found with other types of qualitative inquiry such as phenomenology (see Creswell, 2013), themes for these predetermined questions are presented separately and not combined. This decision was chosen a priori due to the specific nature of the questions, the exploratory nature of the qualitative questions asked, and because we did not aim to capture the overall experience of suicidal ideation in adults who stutter in this study. Note that it was expected that themes might overlap across questions to some degree, and this is accounted for in the discussion and interpretation of findings.

The themes reported below in the results come from all data collected. Consistent with past qualitative research in stuttering using large samples of data (Tichenor & Yaruss, 2019b, 2020a) and qualitative research standard practice (Fusch & Ness, 2015), no saturation analysis was conducted. The large sample size, consistency of the themes, and varied backgrounds of the participants support the credibility of the results. The last author, a researcher with extensive experience using qualitative methods and SLP who is a board-certified specialist in stuttering, completed a reliability analysis on the themes by coding 20% of the data independent of the first author. The first author and last author agreed on the content and structure of the themes, though a discussion was needed to agree on the specific labels used for the themes presented below.

Results

This study investigated suicidal ideation via both quantitative and qualitative means. Together, the analyses presented below provide different insights into these participants' experiences with suicidal ideation.

Quantitative Data

Raw data for the 140 adults who stutter who completed the SBQ-R are visualized in Figure 1. The data skew right (M = 7.36, SD = 3.86, range: 3–17), meaning that most adults who stutter demonstrated lower SBQ-R Total Scores (i.e., less likelihood of suicidal ideation). Nevertheless, a notable proportion of these participants demonstrated a total score of 7 or higher (n = 70, 50%) or 8 or higher (n = 60, 42.9%), corresponding to the published and validated cutoff values for screening positive for suicidal ideation among nonclinical and clinical (psychiatric) normative samples, respectively (see Osman et al., 2001). The raw data are presented here in the interest of transparency; they should not be used normatively as being indicative of the population of people who stutter. (This caveat is discussed in more detail in the discussion and in the future direction and limitation sections below.)

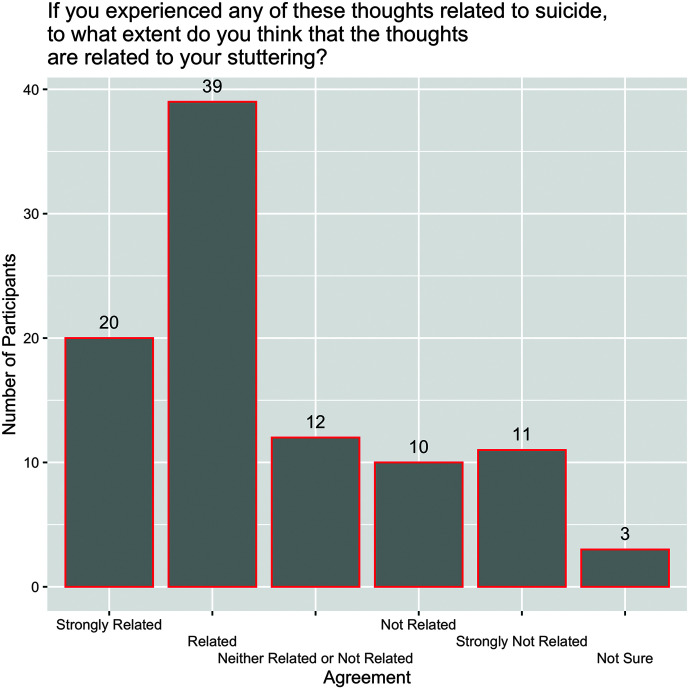

Individuals who reported at least some degree of suicidal ideation on the SBQ-R (i.e., those who scored a 5 or higher; n = 95) were asked to what extent they thought these thoughts were related to their stuttering (Question 4). A majority of these participants indicated that their suicidal thoughts were either strongly related (n = 20) or related (n = 39) to their stuttering. See Figure 2 for the visualization of those data. These results indicate that suicidal ideation was common in adults who stutter in this study and that a majority of those who did report experiencing suicidal ideation (62.1%, n = 59) felt that such thoughts were at least somewhat related to their stuttering. Participants also reported a wide range of ages when they first experienced thoughts related to suicide (M = 17.7 years, SD = 8.2, range: 6–55 years; Question 5).

Figure 2.

The number of adults who stutter who indicated their agreement to whether their suicidal thoughts are related to stuttering is plotted by number of adults reporting each agreement Likert response.

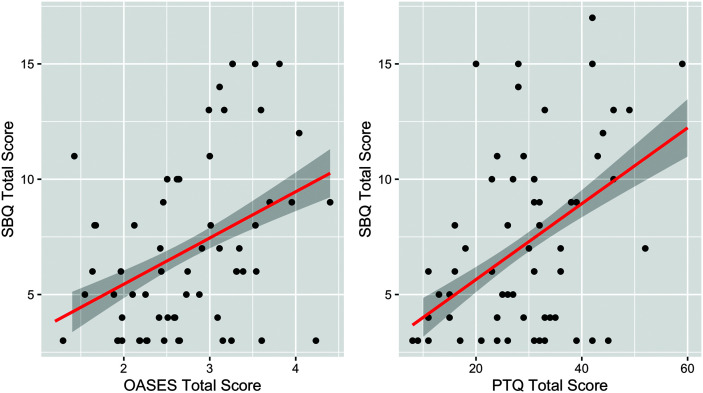

To investigate the relationship between suicidal ideation (SBQ-R Total Score), RNT (PTQ Total Score), and adverse impact related to stuttering (OASES Total Score), two linear regression models were built. The raw data between SBQ-R, OASES, and PTQ Total Scores are visualized in Figure 3. PTQ Total Score explained a significant amount of the variance of SBQ-R Total Score, F(1, 66) = 18.73, p < .001, R 2 = .22, R 2 Adjusted = .21, f2 = .28. The effect size of this prediction was small to medium (Cohen, 1988). SBQ-R Total Score was predicted to increase by .16 for each point increase in PTQ total score. Similarly, OASES Total Score explained a statistically significant amount of the variance of SBQ-R Total Score, F(1, 63) = 12.19, p < .001, R 2 = .16, R 2 Adjusted = .15, f2 = .19. The effect size of this prediction was also small to medium (Cohen, 1988). SBQ-R Total Score was predicted to increase by 2.01 points for every 1 point increase in OASES Total Score. See Table 2 for more information on both regression equations, including the standardized beta coefficients.

Figure 3.

The raw data between SBQ-R, OASES, and PTQ Total Scores are visualized. The regression line is visualized in red. The shaded portion indicates the standard error of the prediction. SBQ-R =Suicide Behavior Questionnaire–Revised; OASES = Overall Assessment of the Speaker's Experience of Stuttering; PTQ = Perseverative Thinking Questionnaire.

Table 2.

Linear regression model results.

| Model | B | SE B | β | τ | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PTQ Model | 0.164 | 0.038 | 0.470 | 4.328 | < .001 |

| OASES Model | 2.001 | 0.574 | 0.403 | 3.491 | < .001 |

Note. Bolded cells indicate significant effects. PTQ = Perseverative Thinking Questionnaire; OASES = Overall Assessment of the Speaker's Experience of Stuttering.

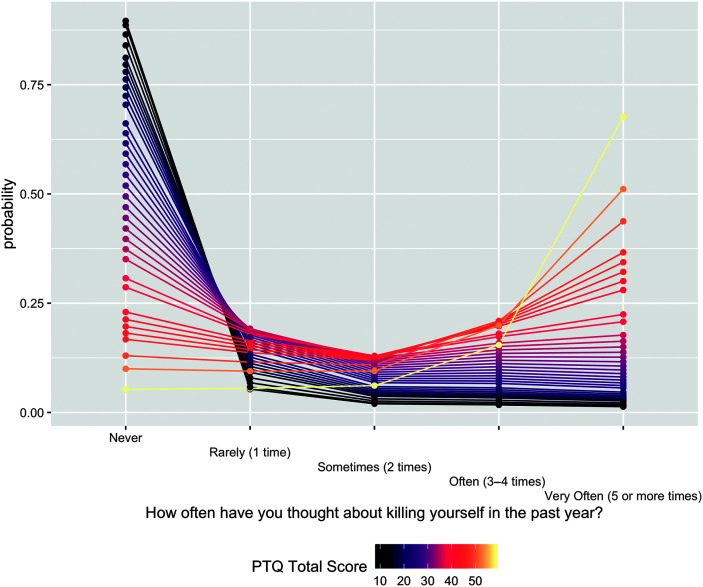

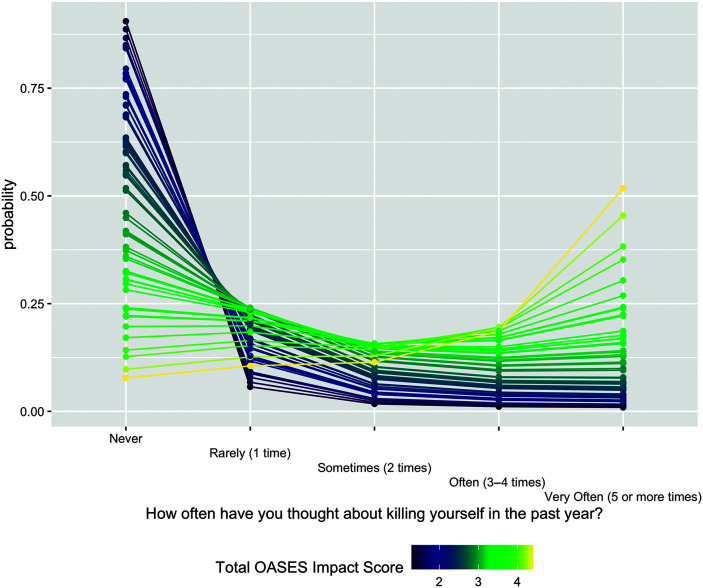

Adverse impact related to stuttering and tendency to engage in RNT, measured via the OASES and PTQ, respectively, were used to predict a person's responses to the question How often have you thought about killing yourself in the past year? A 1-point increase in PTQ Total Score significantly increased the odds of a respondent indicating more frequent suicidal thoughts in the past year by 1.10 at a 95% confidence interval (CI; range: 1.06–1.16). A 1-point increase in OASES Total Score also significantly increased the odds of an adult who stutters indicating more frequent suicidal thoughts in the past year by 4.59 at a 95% CI (range: 2.22–10.21). Because odds are difficult to interpret intuitively, and because odds ratios are not directly comparable as they are unstandardized effect sizes, predicted probabilities were calculated for each observed PTQ and OASES Total Score in the data set and plotted at each level of the SBQ-R question responses (see Figures 4 and 5). As shown in both figures, the more these participants experienced adverse impact (higher OASES Total Score) or the more they engaged in RNT (higher PTQ Total Score), the more likely they were to have thought about killing themselves in the past year. The reverse pattern is also true; participants who experienced less adverse impact related to stuttering or who engaged less frequently in RNT were less likely to have thought about killing themselves in the past year.

Figure 4.

The predicted probability of a person's agreement with How often have you thought about killing yourself in the past year? is predicted by PTQ Total Score. Higher PTQ Total Scores significantly increase the probability of thinking about killing yourself in the past year. Darker lines indicate lower PTQ Total Scores, whereas lighter lines indicate higher PTQ Total Scores. PTQ = Perseverative Thinking Questionnaire.

Figure 5.

The predicted probability of a person's agreement with How often have you thought about killing yourself in the past year? is predicted by OASES Total Score. Higher OASES-A Total Scores significantly increase the probability of thinking about killing yourself in the past year. Darker lines indicate lower OASES-A Total Scores, whereas lighter lines indicate higher OASES-A Total Scores. OASES = Overall Assessment of the Speaker's Experience of Stuttering.

Qualitative Results

Qualitative data come from questions that were asked of participants who indicated at least some degree of suicidal ideation on the SBQ-R (n = 95). Because the qualitative data came from predetermined questions, the themes for each individual question are presented separately, as discussed in the analysis section above. The experiences of participants were seldom unidimensional. Thus, many statements often echoed more than one theme and, in some situations, the same themes arose in response to more than one question, as was expected. As we have previously done with our other qualitative work (Tichenor & Yaruss, 2018, 2019b, 2020a), portions of a statement that correspond to a given theme are italicized to highlight a specific theme. The predetermined questions and the derived themes can be found listed in Table 3.

Table 3.

Qualitative questions and themes.

| 1. Have these thoughts related to suicide changed over time since they first started? |

| Belonging vs. Being a Burden |

| Variability |

| Protection |

| Triggers |

| 2. What has helped you manage or cope with these thoughts and feelings related to suicide? |

| Lifestyle |

| Consequences |

| Support |

| 3. What triggers these thoughts and feelings related to suicide in your life? |

| Triggers |

Question 1: Have These Thoughts Related to Suicide Changed Over Time Since They First Started?

As this question asked about change over time, it was anticipated the aspects of time and change would be present in the themes highlighted below.

Belonging versus being a burden. Feelings of belonging or being a burden were discussed as two inversely related constructs influencing whether or how a person's suicidal thoughts changed over time. For some individuals, a sense of belonging and not being a burden indicated a reduction in suicidal thoughts over time (i.e., they previously felt as if they did not belong and were a burden, but as these feelings changed, they discussed being less likely to engage in suicidal ideation). Other respondents indicated that they continued to experience feelings of not belonging or being a burden; these feelings were also discussed alongside ongoing feelings of suicidal thoughts.

Participant(40): They've changed only in that the things that trigger them are different. The core thoughts of being worthless remain.

P(59): When I was younger, I felt suicide wouldn't have affected so many people. Now that I'm a mother, wife, daughter, sister…I'm not sure I would recover if one of my children took their own life…I had a cousin commit suicide and that act has forever changed me. I don't think I realized when I was younger how much suicide impacts others.

P(49): From the middle of grade 8 to the middle of grade 11, I thought everything would be better if I wasn't here.

P(107): [These thoughts have changed] …Would my husband be better off if I were dead? How long can I live like this? [I have no current] thoughts to kill myself, as that would be wrong. [I still] just think that being dead or dying from stress of stuttering could be my only escape.

P(143): Yes [these thoughts have changed]. I've grown and realized that I [am] able to interact with people and people accept me even though I stutter…I accept who I am now.

P(147): …My suicidal thoughts passed once I reached college as I found people who accepted me and went to therapy. It returned in my 3rd year of college as I faced a lot of sexism in my major and failed at getting an internship, which really hurt my self-esteem. [The suicidal thoughts] only worsened since the more anxious I was, the more I stuttered, and the more I stuttered, the worse my anxiety became. I felt suicidal again when I first thought to myself that I would never be able to hold a job with my stutter or gain respect from anyone I met.

P(152): These thoughts intensified in my 40s when I felt very alone and isolated.

P(165): Yes [these thoughts have changed over time]. When I was a teen, I had no idea about stuttering. So, I just thought that something was wrong with me and that I should leave this world because I am an embarrassment to myself and to my family. Getting speech therapy when I was 18 and finding out about [the National Stuttering Association] and support groups have really helped me out to know that I am not alone…

Variability. In discussing change over time, thoughts relating to suicide were discussed as being variable/not constant and differing across ages or development. This theme of variability was described both temporally and contextually, and many factors such as support, triggers, intensity of the thoughts, and therapy were discussed as influencing factors. Different individuals also discussed improving or worsening trajectories of these thoughts over time.

P(12): Thoughts ebb and flow. Difficult stuttering experiences now prompt high [suicidal ideation] pretty quickly.

P(13): Yes [these thoughts have changed over time]. At rock bottom, [I] wanted out of my current situation. Almost three years later, I'm in a far better place and happier.

P(20): [These thoughts] have only gotten worse over the decades because I know that death is the only true cure for stuttering, but people keep on dragging me to a therapist to talk about my problems about not being able to talk.

P(37): [These thoughts] became worse after a friend who stutters ended their life.

P(118): [Suicidal thoughts] were worst as a teen because of…grief, bullying, school, stuttering, but they got controlled and I saw a therapist later on. [The suicidal thoughts] got a little bad in college, but now they're manageable and only come to me everyone once in a while as a passing thought.

P(129): [The suicidal thoughts] have changed. My stuttering was the root cause due to the anxiety, bullying, and discrimination that came from it, but now I feel like I have grown as a person and my stutter is a part of me. I even have a job where I interact with strangers. My stutter does affect it, but I don't let it get me down anymore.

P(139): It changes over time and with what my situation is. Sometimes I think I've been doing really great, and things are passing and I'm doing better. Other times I feel like it's pointless to try. It's pointless to work. Nothing matters. It spirals from there.

P(149): [Suicidal thoughts] have not diminished. They have gotten more well thought out and sophisticated, however.

P(172) [These thoughts] were very strong in my teens, less so in college and graduate studies, off and on in romance and business, very strong in my later years of failure.

Protection. Participants discussed factors that they thought protected them from suicidal thoughts, highlighting that these factors changed over time (and are therefore closely related to the previous theme of variability that specifically focused on change over time). Many experiences were discussed as offering protection, including more open acknowledgment of stuttering; positive changes in thoughts, feelings, or views about stuttering; receiving love and acceptance of stuttering by themselves or by others; achieving success; participating in therapy; and the passage of time.

P(16): My thoughts were related to external validation of self-worth, and I have addressed these concerns by creating internal self-worth. The suicidal thoughts were eradicated.

P(17): Suicidal thoughts have been tempered over the years as I had success in love and business…

P(32): …As I've matured, I've found new ways to cope with stuttering and realized that suicide is in no way a solution to my problems.

P(56): Through my later teens and early adulthood, [the suicidal thoughts] evolved into destructive actions always involving drugs and alcohol. It was really a downward spiral of drinking socially helped [my stutter], then becoming an alcoholic, then using drugs and drinking every waking moment, then destructive thoughts & actions. I believe one of the main catalysts was my stutter. Or maybe it was an excuse. Not sure, but I'm older, have a family now, and my child's well-being is directly related to my well-being. That is most important in my life. I've gotten over myself.

P(61): [Suicidal thoughts have] changed remarkably over time. Depending on what I'm doing with my life, the people I surround myself with, the self-esteem that I have, the amount of truth and alignment I feel I have with my core purpose in life all have to do with my mental health and state of well-being….

P(127): …I've gained more experience over the years and realized that I always have options.

P(144): [Suicidal thoughts] started out brief. They scared me and so I quickly dismissed them. But over time I've acclimated to [and acknowledged] them…I do consider [the fact I have suicidal thoughts to be] a reason to avoid ownership of firearms or other weapons.

P(156): [Suicidal thoughts] occurred daily during my teens and were related to or influenced by [covert] stuttering. In my 20's and early 30's, cognitive behavioral therapy and other self-help groups weakened these thoughts. The thoughts returned as an escape route when my stuttering became more severe in my late 30's and early 40's [when] the covert stuttering was literally killing me. The thoughts declined when I started attending NSA conferences, accepting stuttering, learning to voluntary stutter, and identify myself as a person who stutters…I recognize [the suicidal thoughts] as the solution of troubled teen who just wanted the pain of isolation to go away. I recognize it and can share about it with my therapist.

Triggers. Participants also described risk factors or constructs that increase or trigger their suicidal thoughts, in frequency, duration, and severity. As was seen with the related but opposite theme of protection, many triggers were discussed as influencing how suicidal thoughts change over time. Examples of triggers included changes in fluency and stuttering, adverse changes in life situations, illness, negative thoughts, and work challenges.

P(14): [These thoughts have not changed], I always thought that I can't survive in the world, especially the corporate world, if I can't speak clearly and fluently to people.

P(57): My thoughts of suicide became stronger as my difficulties in the workplace increased. They are also related to certain events of my life: loss of my father, then my mother, psychiatric disorders (psychosis) of my wife appeared two years ago.

P(71): I don't think about that method of dying [suicide, as I did before]. I just pray for the end of suffering from this dreaded condition [stuttering].

P(96): [I] have fleeting thoughts of suicide every once in a while. These thoughts usually come up if I'm feeling really anxious, or if I'm feeling really sad for some reason. They usually pass pretty quickly, and they never progress to me thinking about a plan.

P(142): I mostly think [suicidal] thoughts were related to teen angst and puberty, and they were greatly amplified whenever I had an embarrassing “stutter moment.”

Question 2: What Has Helped You Manage or Cope With These Thoughts and Feelings Related to Suicide?

Lifestyle. Participants discussed a range of personally relevant and important hobbies, lifestyle pursuits, and health activities that helped them manage thoughts relating to suicide. The examples offered were broad and included activities such as playing or listening to music, creating artistic works, playing video games, exercising, and pursuing spirituality or religion. Various forms of more formal therapy were also mentioned. Most of these pursuits were discussed in terms of increasing mental health; they were also discussed in terms of distractions to keep suicidal thoughts at bay.

P(29): Distractions like working out and playing video games help take my mind off of killing myself…

P(47): Medication, meditation, counseling, diet, experience, the knowledge that I will cycle up again eventually.

P(57): Stopping working has really helped me to find my freedom, to go out of the atmosphere that has become more and more unbearable at work, to resume physical activity, to walk around, to practice meditation, to listen to a lot of music…

P(74): Music helps distract me when the thoughts are strong.

P(124): Driving without a destination, coffee, sleeping have all helped me to calm down and fend off my suicidal thoughts.

P(139): Recreational drugs, vitamins, exercise, mosh pits.

P(143): Some therapy (speech and psychological)… Learning how to use voluntary stuttering really helped my speech and avoidance behaviors. Also, I met my wife and started a family. They have been a great support system. And, I learned how to play an instrument (bass guitar) that opened up new avenues for me, it actually led to me meeting my wife!”

Consequences. Considering the potential consequences of suicide was discussed as a method of management and coping with suicidal thoughts. Again, the nature or type of consequences that the participants described varied, but a prominent example is the predicted impact on friends, significant others, and family members. Consideration of consequences also included personal experiences with suicidal ideation or suicide by a participant's friend or family member.

P(56): Nothing. Even the birth of my child didn't stop my suicidal behavior. It was two things that turned my life around: My 23-year-old cousin committed suicide, my young son and I found him, and the ripple effect destroyed other lives. [I also] realized what I want in life—to be the best father I possibly can.

P(62): Just allowing myself to think about it. For me, I pretty quickly arrive at the conclusion that it is a terrible idea. I have known friends and family that have both attempted and have ended their lives. It is an incredibly damaging and short-sighted thing to do. When you see it up close you really realize that it is selfish and unfair to your family, friends, and yourself.

P(153): Analysis of fallout after I am gone, [the] fear of death and the unknown, [the] deplorability of [my] weakness.

P(177): …If it wasn't for my twin and my mom, I would [have] killed myself a long time ago. I think to myself, if I do decide to kill myself, I'm going to have everything paid for beforehand so my mom isn't left with having to pay for a funeral and a casket. My twin sister needs me so it's not a possibility to kill myself.

Support. Various forms of support were mentioned as beneficial methods of management and coping. Participants offered a variety of definitions for what support meant to them. These included friends, family, and social or other groups to which they belong.

P(28): Being able to talk to someone and not feel trapped. It also helps to have a spouse who you can be very open and honest with.

P(91): Meditation and support groups.

P(99): Counseling. At sixteen, I was treated with a pat on the head but the experience opened my up to the idea of talking to someone about my challenges.

P(113): Thinking of the future and about the support of all the people around me.

P(129): Growing up with supportive friends and family who help me when necessary.

P(156): Seeking cognitive behavioral therapy and directly addressing feelings of wanting to self-harm, finding spirituality, journaling, finding supporting positive friends, working with self-help programs.

Question 3: What Triggers These Thoughts and Feelings Relating to Suicide in Your Life?

Triggers. When asked specifically about trigger thoughts relating to suicide, participants discussed a range of experiences. No single experience was discussed by all participants, and no single participant gave one unitary trigger. Nevertheless, specific examples of triggers were frequently offered across participants. For this reason, various triggers are presented as examples of a unitary theme with many facets rather than as separate themes or subthemes. Triggers included both personal and environmental factors. Personal triggers included underlying health conditions not related to stuttering, negative thoughts and feelings related to being a person who stutters, failures in life relating to work or relationships, increased feelings of burdensomeness, and decreased feelings of belongingness. Environmental triggers included the negative reactions and judgments of other people in the environment, reminders of inadequacy due to speaking difficulties, and a lack of opportunity due to other people's perceptions about stuttering. A person's relationship with stuttering was also often discussed as important factor contributing to increased or decreased suicidal thoughts.

P(12): I had some experiences where stuttering [presented] a barrier from moving on in graduate school in the profession I was interested in. It was the first time that stuttering presented a barrier in my life that working harder could not overcome. Some people in my program and in the field said that they thought my stuttering would prevent me from being successful. People in my program did not give me the support necessary to be successful. They thought that I was responsible for resolving my stuttering in order to succeed and that if I practiced enough, I would be fluent enough.

P(17): The laughter and ridicule of people, the inability to verbally defend myself, discrimination in business, lack of many friends, the shame, pain, and self-hatred I feel.

P(20): Whenever I try to do something like start a business, get a job, try to order food, or do anything that requires me to talk to other people and I fail [I am triggered into suicidal thoughts]. [These thoughts also occur when] I think about how much of my life I have wasted, or…how much of my life that I have had stolen from me, because of [stuttering], the way I get treated, discriminated, made fun of, etc., etc., etc. I just want it to end so I would not have to put up with it any longer and I would no longer be a burden to the people around [me].

P(75): I have chronic physical illnesses when they act up it can and will send my emotional health to bad places. My son is intellectually disabled, my father has a terminal illness. I became disabled and not able to work. So, I have a lot going on. One thing also that I feel like has contributed to all of mental health problems, is my speech. I felt so alone growing up. I tried to act like the jokes didn't bother me, but they really got me sometimes. This was before the internet, so I had no one else that stuttered. It was just me. It was like God cursed me with this messed up speech impediment.

P(94): The frustration from a bad day of stuttering. The lack of hope of it being ‘cured’. Knowing that I've had it my whole life, and even with speech therapy for most of those years, it's not gotten any better, and it's probably gotten worse! I'm also 25 now and it's depressing knowing that I may have this for the rest of my life and I won't be able to be normal in certain situations.

P(103): Having a bad day with my stuttering triggers these thoughts and feelings. When I meet people for the first time with work and having difficulty saying my own name is an example. The look on people's faces and when some people start treating me like a mentally handicapped person really hurts. These experiences make me realize that it is difficult for someone like me to lead a normal life and these experiences make me want to end my life.

P(109): Stuttering, [I am now aged] 70 and the realization that I am a loser who never fulfilled his potential.

P(118): Stress, anxiety, grief, friend problems, romantic relationship fallout.

P(139): Abuse and feelings of worthlessness.

P(155): I no longer have thoughts of suicide and haven't in years. Previously, feelings of shame and worries about not being able to hide stuttering and being exposed as a person who stutters triggered thoughts and feelings related to suicide.

P(180): I would have a good day and suddenly I cannot say certain words. I'll be able to say one week like numbers I cannot say the next and I have to go to work and be professional and I have to constantly change my words all the time is so tiring. I at my breaking point with having to try not [to] stutter because I cannot bear the thought of being looked at differently.

Summary: Qualitative Data

Results from the thematic analyses reveal that adults who stutter may experience suicidal thoughts that are influenced by several factors, including how much they feel they belong and how much of a burden they feel they are to friends, family, significant others, or society as a whole. These feelings are variable and change over time throughout a person's life. Adults who stutter can feel protection from these thoughts or be triggered to experience these thoughts by both personal and environmental influences. Relatedly, management of suicidal ideation follows this same pattern: Speakers may ease or mitigate suicidal thoughts through lifestyle habits, by considering the consequences of such thoughts or actions, and by attaining or participating in support. Importantly, it appears from these participants' reports that suicidal thoughts may diminish, but they do not always disappear, and they may be triggered in myriad ways depending on the person, their relationship with stuttering, and their experiences in life.

Discussion

The purposes of this study were to explore the occurrence of suicidal ideation in a sample of adults who stutter; to evaluate the relationship between adverse impact related to stuttering, RNT, and suicidal ideation; and to qualitatively explore the experiences of adults who stutter who reported experiencing suicidal thoughts. These research questions were asked to support future research in this area and to support SLPs in becoming better prepared to both recognize and understand suicidal ideation in their clients. With an increased ability to recognize suicidal ideation in adults who stutter, and with a deeper understanding of their mental processes, SLPs can hone their education and counseling skills in order to better serve the needs of their clients who stutter.

Predictors of Suicidal Ideation in Adults Who Stutter

Results from quantitative data indicated that the majority of participants experienced at least some degree of suicidal ideation (n = 95 out of 140 participants, 67.9%). This indicates that, in our sample of adults who stutter, suicidal ideation was a common experience. In order to probe the relationship between suicidal thoughts and stuttering, participants were asked to indicate to what degree they felt that their suicidal thoughts were related to stuttering. Fifty-nine out of the 95 participants who reported some degree of suicidal ideation indicated that feelings related to suicide were related (n = 39) or strongly related (n = 20) to stuttering. These findings add support to the notion that suicidal ideation is experienced by many adults who stutter (see Briley et al., 2021; Kuster et al., 2013). Moreover, these data suggest that stuttering is at least partially responsible for suicidal ideation from the perspectives of these adults who live with the condition.

In 2010, the WHO conducted community surveys in 21 countries (N > 100,000) and found that the prevalence of suicidal ideation was 2.0% (Borges et al., 2010). The lifetime estimated prevalence of suicidal ideation has been estimated at 9.0% (Nock et al., 2008). In the United States, the annual prevalence of suicidal ideation has been recently estimated at 4.0% (Piscopo et al., 2016). Thus, the fact that such a high proportion of adults who stutter in this study reported a history of suicidal ideation is deeply concerning. SLPs must be aware that their clients may have or be at risk for developing such thoughts. Potentially valuable to SLPs are our findings showing that individual characteristics significantly predicted rates of suicidal ideation. Statistically significant relationships were found between suicidal ideation, as measured by the SBQ-R; adverse impact related to stuttering, as measured by OASES Total Score; and RNT, as measured by the PTQ Total Score. Specifically, participants with higher OASES Total Scores were significantly more likely to demonstrate higher SBQ-R scores, reflecting greater suicidal ideation. Participants who engaged more frequently in RNT also demonstrated higher levels of suicidal ideation (see Figure 3). The effect sizes of these relationships were small to medium, highlighting the importance of these relationships. Similarly, analysis of the relationships between RNT, adverse impact related to stuttering, and a question on the SBQ-R that gauged recent or current suicidal ideation (How often have you thought about killing yourself in the past year?) revealed that both engaging more frequently in RNT and having higher OASES Total Scores significantly increased the likelihood of more frequent recent thoughts related to suicide (see Figures 4 and 5). Again, these effect sizes of these relationships were meaningful as represented by odds ratios and as visualized in the probability plots. These findings highlight the importance for SLPs of understanding the individual experiences of their clients who stutter and the factors that may place them at higher risk for suicidal ideation.

The Experiences of Adults Who Stutter With Suicidal Ideation

This study also qualitatively explored the experiences of adults who stutter who report suicidal ideation via an exploratory qualitative study. Based on the interpersonal theory of suicide (Van Orden et al., 2010), it can be hypothesized that adults who stutter may have thoughts related to suicide if they felt a lack of belonging or that they were a burden to others. The statements by participants supported this view. For example, some participants discussed that, over time, suicidal thoughts had decreased in frequency and severity as they increased their intimate personal connections with others and found more meaningful life experiences. For example, P(143) stated, “I've grown and realized that I [am] able to interact with people and people accept me even though I stutter.” Other participants discussed a lack of change over time in these areas and either persistent or increased suicidal thoughts. For example, P(152) stated, “These thoughts intensified in my 40s when I felt very alone and isolated.” This theme supports research outside of stuttering suggesting that the intersection of belonging and being a burden is vital to understanding (and potentially reducing) the occurrence of suicidal thoughts (see Van Orden et al., 2010).

Three themes (protection, support, and consequences) also appeared in response to questions that asked about change over time and management of suicidal ideation. These themes were highly related, indicating similar meaning and content. The theme of protection reflected factors that mitigate or shield against suicidal thoughts in terms of frequency or severity. Participants offered many examples of what could be protective, including having a more positive outlook, changing their own perspectives, and receiving love and acceptance by others. The theme of support also took on many forms; participants offered various examples of behaviors, relationships, and activities that provided them support in facing their stuttering and their suicidal thoughts. These frequently included personal relationships that allowed the sharing of feelings; this can be fostered directly in therapy via counseling (Luterman, 2017) or via participation in stuttering-focused self-help groups (Blumgart et al., 2014; Gerlach et al., 2019; Yaruss, Quesal, Reeves, et al., 2002). These findings highlight one way that clinicians can help their clients who are at risk for or who are experiencing suicidal ideation; this is discussed in more detail below. The theme of consequences reflected the recognition of the impact that one's suicide might have on others. Examples of consequences included considering who would take care of children, wondering whether a loved one could live on their own, or reflecting on how someone else's suicide had impacted the participants themselves. Thus, consideration of possible consequences may also be seen as a protective factor against suicidal thoughts.

Importantly, the theme of protection was closely associated with variability. In other words, these aspects develop and change throughout life. As a result, clinicians should not overlook the importance of acceptance, positive thoughts, self-esteem, and overall life successes when considering themes such as consequences and other protective factors. Suicidal ideation varies throughout a person's life, so clinicians should consider a client's current mental state and level of support when exploring thoughts related to suicide. Just as importantly, clinicians must recognize that protective factors can be bolstered and increased, and this points toward ways that clinicians can prepare themselves to help people who stutter who experience suicidal ideation.

Clinical Applications

As noted, 59 participants in this study who reported at least some suicidal ideation on the SBQ-R (42.1%) indicated that their suicidal thoughts were related or strongly related to stuttering. This finding highlights how important it is for SLPs to be aware of the potential for suicidal ideation among their clients who stutter and underscores the role SLPs can play in improving the lives of people who stutter through holistic stuttering therapy. That is, findings support the value of therapy focused on decreasing adverse impact in all of its forms, rather than solely or primarily encouraging perceptibly fluent speech (Tichenor, Constantino, et al., 2022; Tichenor, Herring, et al., 2022; Tichenor & Yaruss, 2019a, 2019b, 2020a, 2020b). Such therapy necessarily involves addressing negative thoughts and feelings related to stuttering when present; holistic therapy may help to prevent suicidal thoughts from developing in a person who stutters.

Interventions for suicidal ideation and suicide attempts have historically focused on preventing exposure to risk factors and, if exposure has already occurred, mitigating that exposure (Osman et al., 2002). This process is often referred to as selective prevention (Mrazek & Haggerty, 1994). Risks for suicidal ideation include both predisposing factors (e.g., previous suicide attempts, psychiatric conditions, illnesses, family history, living alone, being unemployed or retired) and precipitating factors (e.g., access to weapons or recent life stressors such as financial hardship, relationship difficulties). Many of these risk factors are unavoidable depending on the person and their life situation (Bertolote, 2014). For example, family history, concomitant mental health conditions, and history of suicidal attempts cannot be altered. For that reason, research related to suicide prevention often focuses on bolstering or supporting those protective factors that can be targeted in therapy. The specific protective factors that might be addressed varied across individuals and include personal characteristics (e.g., confidence, ability to seek help when needed, openness to others' perspectives) and good family relationships (Bertolote, 2014). Cultural, societal, and environmental factors may also be protective. For example, fostering a sense of purpose in life, support from friends and family, and engaging in hobbies or exercise can all aide in preventing the development of suicidal ideation (Juurlink et al., 2004; Kleiman & Liu, 2013; Pietrzak et al., 2010; Vancampfort et al., 2018). Note that all of these themes, which were reflected in the responses of our participants, can all be addressed through therapy and support for people who stutter.

More specifically, stuttering research and personal stories have shown that participating in self-help and support can greatly alleviate the burden of living with stuttering (Ahlbach & Benson, 1994; Bradberry, 1997; Gerlach et al., 2019; Trichon & Tetnowski, 2011; Yaruss, Quesal, Reeves, et al., 2002). Our own research has shown that participating in self-help and support greatly diminishes the risk of negative affective, behavioral, and cognitive reactions to moments of stuttering (Tichenor & Yaruss, 2019a; Yaruss, Quesal, & Murphy, 2002). Data from this study underscore the value of self-help and support for people who stutter. Only 40% of participants in this study indicated a history of self-help or support participation, despite research and theory in the broader suicidal ideation literature showing the role of support in protecting against suicidal ideation (Van Orden et al., 2010). Though some people who stutter may not be ready for self-help and support, depending on where they are in terms of managing the condition, offering connections to self-help and support is one concrete way that clinicians can help to foster the development of protective factors that minimize the development of suicidal ideation.

Various forms of cognitive therapy have increasingly been used to restructure negative thinking patterns and promote resilience toward suicidal thoughts (Surgenor, 2015). Decades ago, Cooper (1966) noted how stuttering therapy has many commonalities with psychotherapy, and numerous authors have since highlighted the benefits of cognitive therapies in the context of comprehensive and holistic stuttering treatment (Beilby et al., 2012a; Blood, 1995; Boyle, 2011; Cheasman, 2013; Emerick, 1988; Helgadóttir et al., 2014; Kelman & Wheeler, 2015; R. G. Menzies et al., 2008, 2009; Palasik & Hannan, 2013; Plexico & Sandage, 2011; Van Riper, 1973). Even if clinicians do not have formal training in cognitive therapy or counseling methods, they can still create a positive relationship rooted in empathy and honesty (Ginsberg & Wexler, 2000) as a way of expressing regard and respect for their clients. Moreover, there are numerous resources available to SLPs who wish to gain skills in counseling or cognitive therapy. For example, ASHA recently established a new special interest group focused solely on counseling (SIG 20), which offers resources on establishing or improving counseling skills to SLPs. Many authors have also provided helpful tutorials on cognitive behavior therapy (Koç, 2010; R. G. Menzies et al., 2009; R. Menzies et al., 2019; Reddy et al., 2010), acceptance and commitment therapy (Beilby & Byrnes, 2012; Beilby et al., 2012b; Hart et al., 2021; Michise & Palasik, 2017; Nax & Kausar, 2020; Palasik & Hannan, 2013), mindfulness (Boyle, 2011; Emge & Pellowski, 2019; Plexico & Sandage, 2011), desensitization (W. P. Murphy, Yaruss, et al., 2007; Van Riper, 1973), and self-acceptance (De Nardo et al., 2016; Plexico et al., 2019), all of which have been shown to help clients who stutter address affective, behavioral, and cognitive aspects of stuttering and reduce the adverse impact of living with stuttering. Such interventions are consistent with ASHA (2016) scope of practice, which states that “the role of the SLP in the counseling process includes interactions related to emotional reactions, thoughts, feelings, and behaviors that result from living with the communication disorder…” (p. 10). Findings from this study highlight how clinicians can help to decrease the burden of living with stuttering and thereby minimize the likelihood that an individual will develop suicidal thoughts by working to reduce the adverse impact of stuttering on a person's life, helping clients foster connections and develop feelings of inclusion and belonging, and increasing positive thoughts related to communication.

Of course, clinicians must also be aware of the limits to their scope of practice in keeping with the ASHA code of ethics (see ASHA, 2016): They should not attempt to treat suicidal ideation itself or negative thoughts not related to stuttering (or other speech/language issues). They must also involve appropriate mental health professionals immediately if they determine that a client is engaging in suicidal thoughts. To this end, SLPs should develop relationships with psychologists, psychiatrists, counselors, social workers, and professionals who specialize in suicidal ideation and mental health. Notably, these professionals can be a valuable resource even for clients who are not experiencing suicidal ideation (Lindsay & Langevin, 2017), so they should be viewed as an important part of an interdisciplinary team in the treatment of individuals who stutter. Finally, SLPs in the United States can educate their clients about the “988” toll-free telephone dialing code for the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline, the major crisis telephone hotline (Hogan & Goldman, 2021). Calls or texts to 988 are answered by trained crisis counselors who can support any person who is experiencing suicidal, mental health, or substance abuse crises.

Limitations and Future Directions

There are several limitations related to sample size that should be considered when interpreting data from this study. First, though our study is large for a mixed-method study in the area of stuttering, our sample was largely composed of White and non-Hispanic individuals from the United States who had participated in formalized stuttering therapy, with a smaller number of participants from Europe, Asia, and elsewhere. The literature suggests that there are differences in suicidal ideation across races and ethnicities (Rossom et al., 2017). Given that there is not one universal definition of suicidal ideation across cultures, however (see Harmer et al., 2023), care should be taken when applying these findings to different samples or populations of adults who stutter. The broader suicidal ideation literature suggests that suicidal thoughts may be more common in males than females, and males are more represented in our participant sample due to the higher prevalence of stuttering in men than women. Future work should enroll more participants who have had different lived experiences related to stuttering to examine whether certain aspects of the experience of stuttering might be more related to suicidal ideation in some individuals. Such research should specifically explore the relationships between suicidal ideation, adverse impact related to stuttering, and RNT, with particular reference to a participant's verified clinical history with suicide and/or suicidal ideation and other potential diagnoses and experiences.