Abstract

Background.

Helicobacter pylori (Hp) is among the most common bacterial infections in the world and one of the most common infectious agents linked to malignancy, gastric cancer (GC). Within the US there is high disparity in the rates of Hp infection and associated diseases. Hp infection is treatable, and knowledge may influence screening and treatment seeking behaviors.

Materials and Methods.

In this cross-sectional study of 1042 respondents recruited from the Online Amazon MTurk platform, we sought to assess baseline knowledge of Hp and to gain insight into barriers related to Hp care.

Results.

Just over half (52.3%) reported some prior knowledge of Hp with 11.7% (n=122) reporting being treated for Hp themselves and 21.4% reporting family members diagnosed with Hp. Of respondents reporting prior treatment, 95 (78%) reported GI upset and 27 (21%) reported not completing medications. Specific to Hp and GC, 70% indicated that a belief that the treatment was worse than the symptoms would affect their willingness to seek care, while 81% indicated knowing Hp can cause GC would affect their treatment decisions and knowing their gastric symptoms were caused by Hp would affect their willingness to receive care.

Conclusions.

Knowledge of Hp in this US sample of online respondents is low and self-reported difficulties with treatment compliance is high. Increasing awareness of this infection and addressing the challenges to treatment compliance could potentially reduce rates of Hp antibiotic resistance and progression to GC or other complications of Hp infection.

Keywords: Helicobacter pylori, Knowledge, Attitude, Practice, Compliance

INTRODUCTION

Helicobacter pylori (Hp) is among the most common bacterial infections in the world, with infection rates ranging from 80–91% in developing countries to 11–25% among developed countries.1 It is one of the most common infectious agents linked to any malignancy and approximately 90% of non-cardia gastric cancers (GC) are attributable to Hp worldwide.2 The World Health Organization has classified Hp as a group I carcinogen3 and labeled it as a “High Priority” for research and development of new antibiotics due to expanding antibiotic resistance and risk to public health.4 Hp infection is also linked to 80% of chronic gastritis5, 60–100% of peptic ulcers6, and 90% of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma.7

Certain ethnic groups in the United States (US) have been found to have higher rates of Hp positivity and GC including Black, American Indian/Alaska Native and Hispanic people8,9 as well as individuals living along the US/Mexico border.10 In the US, Alaska Natives have the highest prevalence rates of Hp infection (75–80%).11 We found Hp prevalence near 65% among certain northern Arizona American Indian communities.12 American Indians and Alaska Native populations also have higher rates of non-cardia GC compared to non-Hispanic Whites.9 Certain counties in Alaska, New Mexico, and northern Arizona have non-cardia GC mortality rates which are two standard deviations above the US average.13 What drives these differences in infection and cancer incidence rates is not fully understood.

Hp is thought to be acquired during early life through fecal-oral transmission and/or saliva.14 Known risk factors for infection include living with someone who has Hp15, living in a crowded home, drinking unsafe water and poor hygiene practices.16 Due to the attributable risk of Hp for GC, it follows that protective measures to reduce GC risk include actions that may influence Hp infection. These protective measures include reducing salt intake17, eating more fresh fruits and vegetables18, not sharing utensils/oral secretions19, eliminating processed foods20, and smoking cessation.21

Given that Hp is treatable, understanding patient care seeking behavior is important. Utilization of health care is affected not only by an individuals’ physical access to care, but also by an understanding of why they require care and a willingness to receive that care.22 Knowledge, attitude and practice (KAP) surveys have been used around the world since the 1950s to determine the existing resources and gaps prior to developing interventions for a variety of health, economic and social issues.23 Previous research indicates that individuals with greater disease knowledge have higher adherence with treatment regimens.24

Baseline knowledge about Hp among the general US population and population subgroups is unknown. A KAP survey about Hp has not been performed in the US since 1997, and that survey focused on peptic ulcer disease (PUD) rather than Hp and its association with GC.25 Before more focused efforts can be made to address both knowledge gaps and the factors influencing patients’ care seeking and compliance, a baseline assessment is important.

This cross-sectional study sought to assess baseline knowledge of Hp within the US as well as to gain insight into barriers related to Hp care. This information will be useful to identify knowledge gaps and to design an implementation to reduce Hp associated diseases.

METHODS

Development of the survey

For this survey, we used questions from existing surveys on Hp risk factors and treatment26–29 and developed additional questions. Nine questions asked about the respondent’s personal and family experience with Hp, including if they or family members had been told they were infected with Hp and, if they tested positive, how it was confirmed and their experience with the treatment. Three questions related to the degree to which Hp knowledge influences decisions to receive care (knowing about the association with gastric symptoms, belief treatment is worse than symptoms and knowing Hp is associated with GC) and five questions assessed respondent’s access to medical care in general (transportation to services, financial resources, insurance, convenience of appointment time, and availability of child/elder care).

Questions gauging existing knowledge of Hp associations fell into three domains: (i) six questions asking about the association between Hp specific diseases: gastritis, PUD, diabetes (low is correct), GC, MALT, or modes of transmission (selecting fecal-oral & person to person and not selecting vectorborne or droplet are correct, (ii) six questions about risk factors surrounding either acquiring Hp infection including living with someone with Hp, crowding in home, unsafe water, and poor hygiene or the development of GC where family history (low is correct) and stress (low is correct) were asked, and (iii) seven questions about actions to prevent Hp infection, which included reducing salt intake, increasing green leafy vegetables (low is correct), not sharing eating utensils, drinking probiotic yogurt (low is correct), eliminating processed foods (low is correct), reduced charred foods, quitting smoking (low is correct). Except for mode of transmission which was correct or not, these questions were asked using a scale of 0–100 (0 being no association and 100 being a causal association), where respondents estimated how much these risk factors or diseases were associated with Hp infection or incidence of GC.

Sociodemographic information included gender identity (male/female/non-binary or gender neutral/prefer to self-describe), race and ethnicity (non-mutually exclusive), education (high school or less, some college, bachelor’s degree, graduate or professional degree), income (dichotomized at a household income of less than $30,000 annually), community size and state of primary residence. Because household size (number of people in addition to self) and water sources (well vs municipal or bottled) have been associated with Hp infection, we also included these questions. The complete survey is provided as Supplementary Material.

The survey was reviewed and finalized by a working group including public health professionals and physicians who diagnose and treat Hp. The survey was piloted for errors and adjusted before being formally launched. Attention check questions were included to encourage data quality and completeness.30 The survey was implemented using REDCap electronic data capture hosted at the University of Arizona Center for Biomedical Information and Biostatistics. REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture) is a secure, web-based platform designed to anonymously store responses.31,32

Survey Distribution

The internet-based survey of the general population in the US was implemented through Amazon’s Mechanical Turk (MTurk) Survey System linking to the UArizona hosted REDCap survey. MTurk is a crowdsourcing website used to hire individuals for on-demand tasks. The use of MTurk respondents in research has been previously validated.33,34 MTurk participants were provided with a description of the survey prior to answering questions and were allowed to opt-in or opt-out at any time. Eligible respondents were at least 18 years old and able to read and write in English.

The survey was conducted in March-May 2021. The survey was launched in several stages to oversample in states with larger American Indian populations and then opened to “All US”. A $1 incentive for completing the survey was automatically distributed to respondents through the Amazon MTurk platform.

Scoring System

To meaningfully compare variables to an individual’s baseline Hp knowledge, a scoring system was developed. Questions were structured as “What percentage of (disease) cases do you think are because someone is infected with Helicobacter pylori” or “What percentage of Helicobacter pylori (or gastric cancer) cases could be eliminated by (risk factor/preventative measure)”. Answers were given initially on a scale of 0 to 100 and were dichotomized into a “correct” or “incorrect” response based on previous research attempting to provide quantified equivalents to qualitative answers.31 If the estimated association between the variable and the outcome reported in the literature was high, the respondent was scored a “1” for an answer of 60 to 100% and “0” for an answer of less than 60%. If the association between the variable and the outcome was low in reported literature, the respondent was scored a “1” for an answer of 0–40% and “0” for a score of greater than 40%. For the question living in a crowded or unsanitary home where the association was weakly negative, a score of “1” was given for 59% and less and for the question about amount of GC that could be prevented through the elimination of charred foods or smoking and alcohol question the association was weakly positive and a score of “1” was given for a response of 41 or greater.

Among the six disease association questions for diabetes low attribution to Hp was considered correct) and for the modes of transmission selecting fecal-oral & person to person and not selecting vectorborne or droplet were correct with 0.25 points each. Among the six risk factor questions family history of GC and stress low estimates of Hp or GC prevented was considered correct. Finally, for the seven prevention questions increasing green leafy vegetables, drinking probiotic yogurt, eliminating processed foods, and quitting smoking, attributing a lower percent of prevention was correct.

Maximum scores for each of the three domains are as follows: disease associations = six; Hp and GC incidence risk factors = six, and GC prevention = seven.

Data Analysis

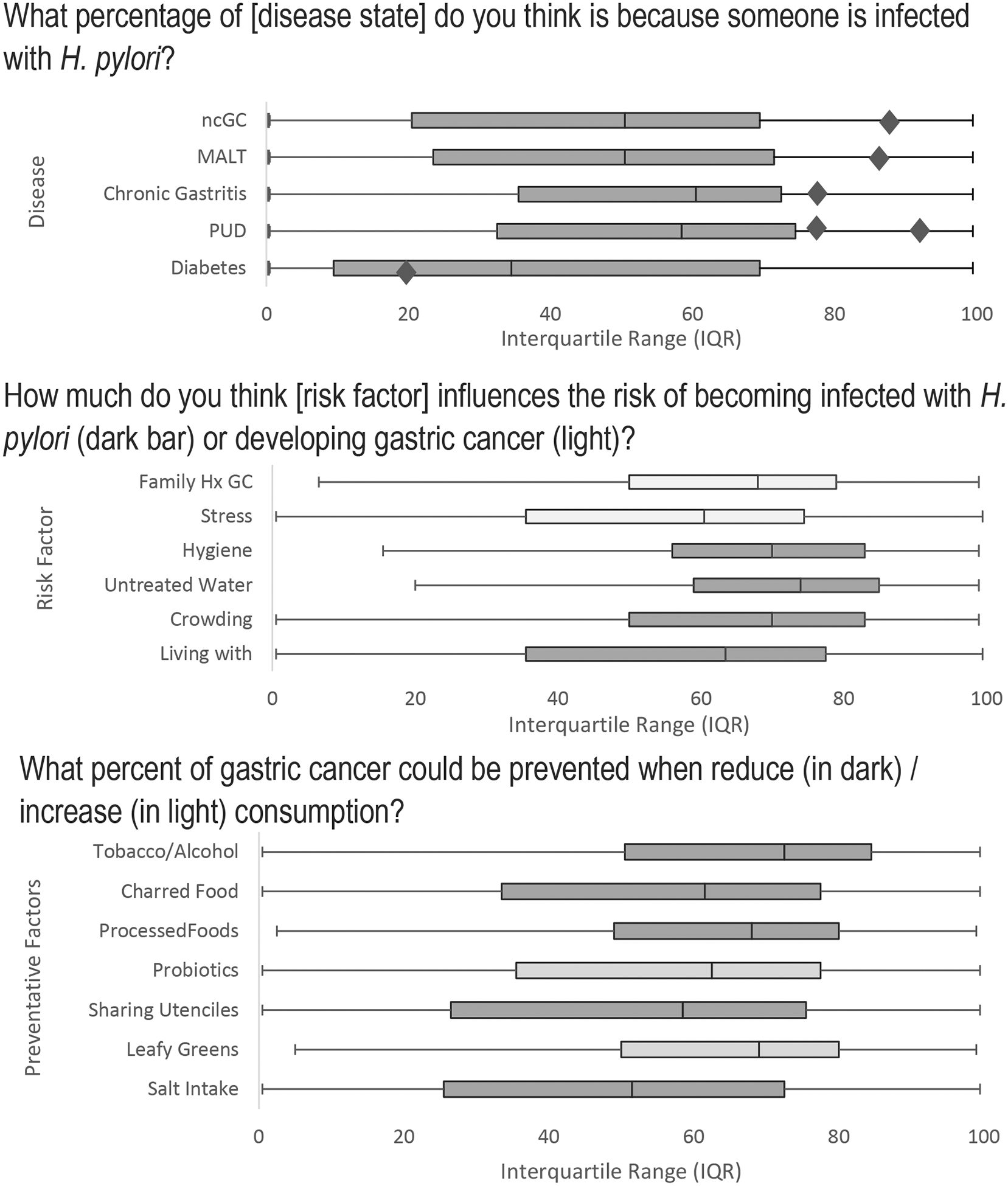

Descriptive statistics were performed to summarize the response frequencies. Because the disease association, risk factor and prevention responses were highly skewed, we used box plots to describe the spread of the responses, including the median value and the interquartile range (range of the middle 50% of the responses).

We used two sided t-test to compare the scores for each of the three knowledge domains a) disease associations with Hp, b) knowledge of risk factors associated with Hp and c) Hp prevention scores by dichotomized income (less than $30,000, greater than or equal to $30,000), gender (male/female), educational attainment (less than bachelor’s degree, bachelors or higher) and by experience with Hp, specifically, whether the participant themselves had ever been tested or treated (ever/never) and whether they had a family member who had been told they were positive (yes/no).

The Stata 17.0 (College Park, TX) statistical software was used for data analysis. Alpha of < 0.05 was considered significant.

Ethical Considerations

The study protocol was reviewed and deemed exempt by the University of Arizona Institutional Review Board (project ID: 201011265).

RESULTS

A total of 1,042 respondents completed the survey (Table 1). The average time to complete the survey was 6.25 minutes. Respondents from 49 states completed the survey with most (11.8%) coming from California, followed by Arizona (8.73%) and Washington (7.87%). Over 57% of the sample were male and 82.6% made more than $30,000 annually. They were overwhelmingly educated with 92% having some college education or more. More than half (52.5%) lived in a household with four or more people and half (50.3%) were living in an urban community.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study sample overall

| Total | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Total | 1,042 | |

| Gender Identity | ||

| Female | 440 | 42.2% |

| Male | 594 | 57.0% |

| Other | 8 | 0.8% |

| Education | ||

| High School or Less | 83 | 8.0% |

| Some College | 226 | 21.7% |

| Bachelor’s Degree | 530 | 50.9% |

| Graduate or Professional Degree | 203 | 19.5% |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||

| White | 741 | 71.3% |

| Black | 159 | 15.3% |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 9 | 0.8% |

| Asian | 66 | 6.4% |

| Hispanic | 64 | 6.2% |

| Annual Household Income | ||

| Less than $30,000 | 164 | 15.7% |

| Greater than or equal to $30,000 | 861 | 82.6% |

| Prefer not to answer | 17 | 1.6% |

| Neighborhood Type | ||

| Urban | 524 | 50.3% |

| Town | 367 | 35.2% |

| Rural/Farm | 151 | 14.5% |

| Experience with Hp | ||

| Prior knowledge of Hp | 545 | 52.3% |

| Family member with Hp | 223 | 21.4% |

| Previously tested | 160 | 15.4% |

| Endoscopic biopsy | 70 | 23.9% |

| Stool antigen test | 60 | 20.5% |

| Breath test | 67 | 22.9% |

| Serology | 90 | 30.7% |

| Previously treated | 122 | 11.7% |

| Any difficulty | 118 | 96.7% |

| GI upset | 95 | 77.9% |

| Cost of treatment | 27 | 22.1% |

| Inability to finish medications | 27 | 22.1% |

%, percentage of subjects

Totals less than 1042 reflect missing responses on demographic factors

Medical History/ Experience with Hp

Table 1 also shows that just over half (52.3%) of respondents reported some prior knowledge of Hp. Almost one quarter of respondents (21.4%) had family members who had been diagnosed with Hp. Hp positive family members were most commonly a parent (35.1%), sibling (20.2%), or grandparent (15.9%).

Testing and Treatment

Table 1 also shows that of the 160 (15.4%) respondents who had been tested for Hp, 20.5% of them reported they received a stool antigen test, 23.9% reported they were diagnosed by endoscopic biopsy, 22.9% received a breath test and 30.7% reported being diagnosed by serology.

Among those reporting prior treatment for Hp (n=122), 44.3% reported being prescribed antibiotics and 31.4% reported probiotics, with 19.6% reporting both. Most individuals who had been treated did not require more than two treatments (55.6%), with 19.2% reporting only one treatment.

Of the treated respondents, 118 (96.7%) reported some difficulty accessing and completing treatment. The most common reason cited difficulty was GI upset (n=95, 77.9%) and 27 (22.1%) reported they could not take all of the medications. Over a fifth of those treated reported difficulty affording the medications (n=27, 22.1%).

Perceived Knowledge Scores

Associations between knowledge about Hp and related disease outcomes, risk factors for acquisition of Hp infection or GC incidence, and prevention strategies for GC were analyzed by first plotting the distribution of the contribution attributions for each individual question, then calculating and comparing the domain scores across experience and demographic factors.

The top third of Figure 1 shows mean contribution attribution when respondents were asked to estimate what percentage of cases of non-cardia GC, MALT lymphoma, chronic gastritis, PUD, and diabetes could be attributed to infection with Hp. In most disease-Hp attributions the rate of disease caused by Hp suggested by the literature did not fall within the interquartile range (IQR) of responses. 90 to 95% of non-cardia GC is now attributed to Hp infection35,36, but in this case, the mean response was 50% with an IQR of 20–69%. Over 90% of MALT lymphoma has been attributed to Hp7, but respondents reported the mean response was 50% with an IQR of 23–71%. While 80% of chronic gastritis is associated with Hp5, the mean response was 54.2% with an IQR of 35–72%. For PUD, 60–100% are attributable to Hp and that number increases to 90–100% if NSAID-induced peptic ulcers are excluded.6 The mean response for the percentage of cases of PUD caused by Hp was 58% with an IQR of 32–74%. The relationship between Hp and diabetes is still debated, and respondents were not asked to distinguish between type 1 and type 2 diabetes, but the presence of Hp may increase the risk of diabetes by 27%.37 When asked what percentage of diabetes was caused by Hp, the mean response was 34% with an IQR of 9–69%.

Figure 1.

Respondents’ answers to specific questions asking their perception of the magnitude of association for each of the knowledge domains: specific disease states with Hp infection (top), as well as their perception of risk factors for acquiring Hp (center), and actions which can prevent infection or gastric cancer (bottom). For all questions, 0% indicated a lack of association while 100% indicated a strong association. Diamonds represent the estimated true values for the disease associations.

Abbreviations: MALT = Mucosa-associated Lymphoid Tissue; ncGC = non-cardia gastric cancer; PUD = Peptic Ulcer disease; Family Hx GC = Family history gastric cancer; Living with = living with someone infected with Hp.

Not graphed but part of the disease association score was the mode of transmission. Previous research has shown that Hp can be spread by fecal-oral route38 and 75% of current survey participants identified fecal-oral route as a method of Hp spread. A quarter of respondents believed, incorrectly, that the bacteria could be spread by a vector or droplet.

The center panel of Figure 2 indicates the interquartile range of responses for potential risk factors for acquiring the infection and the factors associated with risk of developing GC. Hp is causally associated with living with a Hp positive person15, living in a crowded home16, drinking unsafe water and poor hygiene12,16, and most individuals estimated near 50–60% association with these risk factors for Hp infection. Interestingly, respondents attributed a chronic stressful environment to GC development (median value = 60%) of our respondents which is lower than a prior study from South Korea where participants attributed 73.5% of GC to stress.28 While there is evidence of stress associated with colorectal cancer39 and cardia GC40, the association with non-cardia GC remains understudied. As for history of GC, because first-degree relatives are strongly associated with risk of developing GC41 and specifically for non-cardia GC42 but a genetic marker has yet to be found in familial clusters.43 The role of family history was estimated highly preventative of GC by respondents.

The responses to what precent of gastric cancer would be prevented by action is presented in the lowest panel of Figure 2. While consumption of leafy greens and eating probiotic yogurt are healthy lifestyle choices, their role in preventing GC are not strongly established. For example, in a meta-analysis Lunet et al.44 found a protective effect for fruit intake and GC incidence, but not for vegetables except in when studies had follow-up periods 10 years or longer. Conversely, in two large prospective cohort studies from Europe and China found no effect of fruit or vegetable intake and GC risk.18,45 Use of probiotics has been associated with lowered adverse effects and increased efficacy during Hp eradiation therapy46,47, however effect on cancer prevention requires additional research.48,49 Reducing salt intake17 and removing processed and charred foods45 are associated with GC, which most people recognized. Participants ranked quitting tobacco and alcohol as preventive of GC and a recent meta-analysis found smokers had 1.6 the risk for developing non-cardia GC compares with non-smokers21 though the association for alcohol is less clear.50

Table 2 shows the relationship between the knowledge scores for questions in each of the three domains (disease associations, risk factors, and prevention) with prior experience with the Hp infection and selected sociodemographic characteristics. Experience with Hp, either through family members or themselves being tested and treated, was associated with higher scores on disease association and prevention knowledge. Interestingly, risk factor scores tended to be protective though only significantly different by testing status. Specifically, there was a tendency for those who reported being tested to overestimate the role of chronic stress and family history as risk factors for GC development. Among the demographic factors, those with less education (some college or less) had lower disease association and prevention scores.

Table 2.

The relationship between knowledge scores for each of the three domains: disease associations, risk factors and prevention by prior experience with the Hp infection and sociodemographic characteristics.

| Scores for Knowledge by Domain | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prior experience with Hp | N | Disease Assoc. mean (sd) | Risk Factors mean (sd) | Prevention mean (sd) |

| Family Member with Hp | ||||

| Yes | 223 | 3.65 (1.37)* | 2.76 (0.88) | 4.13 (1.21)* |

| No | 688 | 2.83 (1.38) | 2.88 (0.95) | 3.42 (1.23) |

| Previously Tested | ||||

| Yes | 160 | 3.57 (1.39)* | 2.66 (0.88)* | 4.01 (1.21)* |

| No | 777 | 2.93 (1.42) | 2.86 (0.96) | 3.50 (1.26) |

| Previously Treated | ||||

| Yes | 122 | 3.80 (1.30)* | 2.70 (0.82) | 4.32 (1.11)* |

| No | 865 | 2.90 (1.40) | 2.86 (0.97) | 3.46 (1.24) |

| Sociodemographic characteristics | N | Disease Assoc. mean (sd) | Risk Factors mean (sd) | Prevention mean (sd) |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 594 | 2.98 (1.43) | 2.84 (0.98) | 3.57 (1.29) |

| Female | 440 | 3.10 (1.41) | 2.85 (0.93) | 3.59 (1.19) |

| Income | ||||

| < $30K | 164 | 3.00 (1.44) | 2.79 (0.93) | 3.51 (1.29) |

| > $30K | 861 | 3.05 (1.42) | 2.85 (0.97) | 3.58 (1.25) |

| Education | ||||

| Some college or less | 230 | 2.81 (1.38)* | 2.83 (1.01) | 3.27 (1.17)* |

| Associate Degree or more | 812 | 3.09 (1.42) | 2.84 (0.94) | 3.65 (1.26) |

Notes:

1) Total may not sum to 1042 due to respondents selecting “I don’t know” or “Prefer not to answer”.

2) Statistically significant differences between the mean scores for each association are marked with

3) total possible scores for each of the three domains: Disease association = 6, Risk factors = 6, Prevention = 7.

Barriers to Care

Table 3 shows the frequency of responses to questions about access and barriers to receiving medical care. A large proportion of respondents indicated that the convenience of accessing a medical facility (74%), insurance (77%), and financial issues (77%) were concerns. Just over half (52%) reported access to child or elder care as a barrier to receiving care for themselves. Almost two thirds indicated transportation was a barrier to seeking medical care (often for 34% and sometimes for 30%). Despite that access may be associated with socioeconomic status, in our sample there were no significant differences with respect to these access concerns by income.

Table 3.

Identified barriers for access to medical care and specific beliefs that could affect medical care seeking actions for Helicobacter pylori, n=1042.

| Question: “The following questions are related to your access to medical care and are not specific to H pylori. Please indicate the choice that best shows how often each of the following items influences your decision to receive medical services” | |||

| Yes | No | Unsure | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Availability of child or elder care during my appointments/ services. | 52.3% | 44.1% | 3.6% |

| Availability of medical services or appointments at convenient times. | 74.3% | 23.8% | 1.9% |

| Availability of money or financial resources. | 76.6% | 22.1% | 1.3% |

| Availability of insurance coverage. | 76.8% | 21.4% | 1.8% |

| Availability of transportation from home to medical service. | 63.3% | 34.8% | 1.8% |

| Question: “With respect to seeking treatment for H. pylori infection, please estimate of how much each of the following would influence your decision to receive care. If you have never sought care for H. pylori infection, please mark what you think might influence your decision to receive care in the future.” | |||

| Yes | No | Unsure | |

| Knowing H. pylori is associated with gastric symptoms. | 81.6% | 14.5% | 4.0% |

| Belief that H. pylori treatment is worse than my current symptoms. | 70.6% | 24.8% | 4.6% |

| Knowing H. pylori is a cause of gastric cancer. | 81.7% | 14.5% | 3.8% |

When participants were asked about beliefs that might influence their decision to receive care, please estimate of how much each of the following would influence your decision to receive, 70% of respondents indicated that a belief that the treatment was worse than the symptoms would affect their willingness to seek care. Eighty-one percent indicated that knowing that Hp can cause GC would affect their treatment decisions and the same percentage indicated that knowing their gastric symptoms were caused by Hp would affect their willingness to receive care.

DISCUSSION

We sought to identify knowledge gaps about Hp infection and barriers to treatment seeking in a sample of online media users (MTurk). Specifically, we sought to assess knowledge about Hp treatment and infection sources and to assess barriers to treatment-seeking among US adults. Among the 1042 respondents, 52% reported having some prior knowledge of Hp with 15% reporting they had been tested for Hp in the past and almost 12% received treatment.

Importantly, though self-reported, most of those who reported being treated for Hp (n=118/122, 96.7%) reported some difficulty accessing and completing their prescribed therapy. Over three-quarters (77.9%) of these individuals complained of an “upset stomach”, which has long been a known difficulty with this treatment regimen.51 Only 19.6% of those receive treatment were prescribed probiotics with the antibiotics, while evidence does suggest that use of probiotics may reduce adverse effects of therapy, thereby increasing compliance.52,53

To aid individuals in completing their therapy and avoid the propagation of resistant bacteria, priority should be given to investigating ways to make the therapies more tolerable. Previous research has shown that patients who are educated about how to monitor their medication schedules and the importance of completing their medications have higher adherence rates. While the exact rates are unknown, there is a trend towards greater successful eradication of Hp as the percentage of the prescribed antibiotic regimen completed increases.54 Some previously suggested approaches include pre-sorted pill packs, extended physician counseling, literature on known/expected side effects in easy-to-understand language, and careful follow up to ensure adherence.54 While tailoring treatment based on local resistance is important, it must be done consider responsible antibiotic stewardship.55,56

A belief that the treatment is worse than the symptoms of Hp would influence 70% of all our respondents’ decisions to seek care and 81% indicated that knowledge about Hp being a cause of their symptoms and as a cause of GC would affect their willingness to comply with prescribed therapy

Knowledge was fair with respect to transmission, with 75% correctly selecting fecal-oral transmission and 53% correctly selecting person-to-person transmission through saliva. On average, most individuals thought that more than half of Hp cases could be due to the risk factors of living with infected individuals or crowding. However, knowledge about the disease-states attributed to Hp infection was generally lacking, although personal experience with Hp was associated with higher scores. Having a family member who experienced Hp was associated with both increased knowledge of disease association and prevention method scores as did those previously tested and previously treated. Interestingly, prior experience seemed to lead to lower ability to correctly identify risk factors, especially among those previously tested. Looking at the individual components of the risk factor score, those who themselves tested positive tended to overestimate stress and family history as risk factors. These perceptions might indicate that increased information, particularly among higher risk populations would be appropriate.

While this is the first US-based study addressing the general public’s knowledge about diseases associated with Hp since the 1997 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) study on PUD25, our sample size was smaller and conducted solely via the online survey tool. The CDC survey was included as part of a national Health Styles survey with questionnaires mailed to a representative sample of over 3000 US adults, while we utilized the online crowdsourcing MTurk survey tool to identify respondents. Our results should be generalized with caution as our sample tended to be non-Hispanic White (71.1% compared to a national average of 57.8% based on 2020 US Census) and well-educated (70.4% of our respondents had a bachelor’s degree or higher vs 32.1% of US residents).57 Although the respondents were 50.3% urban-dwellers, this frequency is below the 2010 US Census which indicates that 80.7% of Americans are urban-dwellers.58 The median income of participants in this study was between $50,000 and $59,999 compared to a US average median household income of $67,521 in 2020.59 A previous study comparing MTurk respondents to National Survey data also showed that MTurk respondents were more likely to be male, White, and college educated while having lower household income on average compared to the National Survey.60 We did not find MTurk to be an efficient method for surveying minority populations and suggest a similar study be conducted which can more successfully recruit the populations at greatest risk for Hp associated disease.

The American College of Gastroenterology currently recommends screening for Hp in patients with known current or past PUD (not previously treated for Hp), those with low-grade MALT lymphoma, dyspepsia, and early-stage GC after endoscopic resection. It should also be considered, per guidelines, in those with idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura, those starting chronic treatment with aspirin or other NSAID regimen, and unexplained iron deficiency anemia.61 This means that many infected individuals will not be tested as about 90% of those who are infected with Hp are asymptomatic.54 However, in populations with high incidence or high risk of GC especially in certain Asian countries (Japan, certain regions of China, Korea, Taiwan), Hp screening and eradication has been recommended as a part of GC preventions irrespective of the symptoms.55 Given the synergistic effect of first-degree familial history of GC and Hp infection, eradication is recommended when there is a family history.41,62

Within the general population, actual rates of complications from Hp infection include a 1–10% risk of developing peptic ulcers, a 0.1–3% risk of developing GC, and less than a 0.01% risk of MALT lymphoma.54 While these rates are low, they correspond to 780,000 cancer cases and 6.25% of cancers diagnosed worldwide each year.54 Due to the sheer number of cancer cases related to Hp infection, guidelines recommend eradication with test for cure in all patients, including those that are asymptomatic. Kyoto global consensus guidelines report that benefits of eradication include stopping the progression of histopathologic changes related to Hp infection and associated risk of developing cancer, in addition to societal benefits of reducing reservoir of infected individuals capable of transmitting infection to others. Future guidelines should consider the higher rates of Hp within specific groups as well as the increased risk of non-cardia GC in American Indian and Alaska Native populations9 as this could dramatically affect the number needed to treat calculations for these populations.

CONCLUSION

In summary, knowledge of Hp in the US population is low. Unsurprisingly, those with personal or family experience with Hp were more knowledgeable about the disease. However, recognition of this lack of knowledge is important for encouraging individuals to seek medical care for gastrointestinal complaints potentially related to Hp and in being compliant with therapy. In our study, almost all treated individuals reported difficulty complying with therapy mostly due to GI upset. Addressing these issues could improve compliance thereby potentially reducing rates of Hp antibiotic resistance and progression to GC or other complications of Hp infection.

Supplementary Material

FUNDING

The Art Chapa Foundation provided support for this project. Research reported in this publication was also supported by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under the awards for the Partnership of Native American Cancer Prevention U54CA143924 (UACC) and U54CA143925 (NAU) and by an R01 to Dr Merchant R01 DK118563-04.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts to disclose.

AUTHORSHIP

HEB, RBH, JM, PK, VL were involved with the conception and design of the study. KB, HEB and RBH performed the data collection and analysis. All authors have been involved in the writing and editing of the manuscript and all approve the final version.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hunt R, Xiao S, Megraud F, et al. World Gastroenterology Organisation Global Guideline Helicobacter pylori in Developing Countries. J Dig Dis. 2011;12:319–329. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e31820fb8f6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kotilea K, Bontems P, Touati E. Epidemiology, diagnosis and risk factors of Helicobacter pylori infection. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2019;1149:17–33. doi: 10.1007/5584_2019_357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC). Schistosomes, Liver Flukes and Helicobacter Pylori. IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. Lyon, 7–14 June 1994. Vol 61.; 1994. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7715068. Accessed May 1, 2018. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tacconelli E, Carrara E, Savoldi A, et al. Discovery, research, and development of new antibiotics: the WHO priority list of antibiotic-resistant bacteria and tuberculosis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2018;18(3):318–327. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30753-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sipponen P Helicobacter pylori, chronic gastritis and peptic ulcer. Mater Med Pol. 1992;24(3):166–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gisbert JP, Legido J, García-Sanz I, Pajares JM. Helicobacter pylori and perforated peptic ulcer prevalence of the infection and role of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Dig Liver Dis. 2004;36(2):116–120. doi: 10.1016/J.DLD.2003.10.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stolte M, Bayerdörffer E, Morgner A, et al. Helicobacter and gastric MALT lymphoma. Gut. 2002;50(Suppl 3):iii24. doi: 10.1136/GUT.50.SUPPL_3.III19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Malaty HM. Epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori infection. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2007;21(2):205–214. doi: 10.1016/J.BPG.2006.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Melkonian SC, Pete D, Jim MA, et al. Gastric Cancer Among American Indian and Alaska Native Populations in the United States, 2005–2016. Am J Gastroenterol. 2020;115(12):1989–1997. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000000748 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cardenas VM, Mena KD, Ortiz M, et al. Hyperendemic H. pylori and tapeworm infections in a U.S.-Mexico border population. Public Health Rep. 2010;125(3):441–447. doi: 10.1177/003335491012500313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhu J, Davidson M, Leinonen M, et al. Prevalence and persistence of antibodies to herpes viruses, Chlamydia pneumoniae and Helicobacter pylori in Alaskan Eskimos: the GOCADAN Study. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2006;12(2):118–122. doi: 10.1111/J.1469-0691.2005.01319.X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harris RB, Brown HE, Begay RL, et al. Helicobacter pylori Prevalence and Risk Factors in Three Rural Indigenous Communities of Northern Arizona. Int J Environ Res Public Heal 2022, Vol 19, Page 797. 2022;19(2):797. doi: 10.3390/IJERPH19020797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brown HE, Dennis LK, Lauro P, Jain P, Pelley E, Oren E. Review emerging evidence for infectious causes of cancer in the United States. Epidemiol Rev. 2019;41(1):82–96. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxz003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kayali S, Manfredi M, Gaiani F, et al. Helicobacter pylori, transmission routes and recurrence of infection: state of the art. Acta Biomed. 2018;89(8-S):72–76. doi: 10.23750/ABM.V89I8-S.7947 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kivi M, Johansson ALV, Reilly M, Tindberg Y. Helicobacter pylori status in family members as risk factors for infection in children. Epidemiol Infect. 2005;133(4):645–652. doi: 10.1017/S0950268805003900 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nouraie M, Latifi-Navid S, Rezvan H, et al. Childhood hygienic practice and family education status determine the prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection in Iran. Helicobacter. 2009;14(1):40–46. doi: 10.1111/J.1523-5378.2009.00657.X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peleteiro B, Lopes C, Figueiredo C, Lunet N. Salt intake and gastric cancer risk according to Helicobacter pylori infection, smoking, tumour site and histological type. Br J Cancer. 2011;104(1):198–207. doi: 10.1038/SJ.BJC.6605993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Epplein M, Shu XO, Xiang YB, et al. Fruit and Vegetable Consumption and Risk of Distal Gastric Cancer in the Shanghai Women’s and Men’s Health Studies. Am J Epidemiol. 2010;172(4):397. doi: 10.1093/AJE/KWQ144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Axon ATR. Review article: is Helicobacter pylori transmitted by the gastro-oral route? Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1995;9(6):585–588. doi: 10.1111/J.1365-2036.1995.TB00426.X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.González CA, Jakszyn P, Pera G, et al. Meat intake and risk of stomach and esophageal adenocarcinoma within the European Prospective Investigation Into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC). J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98(5):345–354. doi: 10.1093/JNCI/DJJ071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ladeiras-Lopes R, Pereira AK, Nogueira A, et al. Smoking and gastric cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Cancer Causes Control. 2008;19(7):689–701. doi: 10.1007/S10552-008-9132-Y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Health-Care Utilization as a Proxy in Disability Determination. Heal Util as a Proxy Disabil Determ. April 2018. doi: 10.17226/24969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Launiala A How much can a KAP survey tell us about people’s knowledge, attitudes and practices? Some observations from medical anthropology research on malaria in pregnancy in Malawi. undefined. 1970;11(1). doi: 10.22582/AM.V11I1.31 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sweileh WM, Zyoud SH, Abu Nab’A RJ, et al. Influence of patients’ disease knowledge and beliefs about medicines on medication adherence: findings from a cross-sectional survey among patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus in Palestine. BMC Public Health. 2014;14(1). doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-94 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.CDC. Knowledge about causes of peptic ulcer disease -- United States, March-April 1997. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1997;46(42):985–987. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/00049679.htm. Accessed December 17, 2022. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Driscoll LJ, Brown HE, Harris RB, Oren E. Population knowledge, attitude, and practice regarding Helicobacter pylori transmission and outcomes: A literature review. Front Public Heal. 2017;5:144. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2017.00144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wu Y, Su T, Zhou X, Lu N, Li Z, Du Y. Awareness and attitudes regarding Helicobacter pylori infection in Chinese physicians and public population: A national cross-sectional survey. Helicobacter. 2020;25(4). doi: 10.1111/HEL.12705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Do-Youn O, Kui SC, Hae-Rim S, Yung-Jue B. Public awareness of gastric cancer risk factors and disease screening in a high risk region: A population-based study. Cancer Res Treat. 2009;41(2):59–66. doi: 10.4143/crt.2009.41.2.59 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Murakami TTT, Scranton RARA, Brown HEHE, et al. Management of Helicobacter pylori in the United States: Results from a national survey of gastroenterology physicians. Prev Med (Baltim). 2017;100:216–222. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2017.04.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mason W, Suri S. Conducting behavioral research on Amazon’s Mechanical Turk. Behav Res Methods. 2012;44(1):1–23. doi: 10.3758/s13428-011-0124-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377–381. doi: 10.1016/J.JBI.2008.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Harris PA, Taylor R, Minor BL, et al. The REDCap consortium: Building an international community of software platform partners. J Biomed Inform. 2019;95. doi: 10.1016/J.JBI.2019.103208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Buhrmester MD, Talaifar S, Gosling SD. An Evaluation of Amazon’s Mechanical Turk, Its Rapid Rise, and Its Effective Use. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2018;13(2):149–154. doi: 10.1177/1745691617706516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Loepp E, Kelly JT. Distinction without a difference? An assessment of MTurk Worker types: Res Polit. 2020;7(1). doi: 10.1177/2053168019901185 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shiotani A, Cen P, Graham DY. Eradication of gastric cancer is now both possible and practical. Semin Cancer Biol. 2013;23(6 Pt B):492–501. doi: 10.1016/J.SEMCANCER.2013.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Holleczek B, Schöttker B, Brenner H. Helicobacter pylori infection, chronic atrophic gastritis and risk of stomach and esophagus cancer: Results from the prospective population-based ESTHER cohort study. Int J cancer. 2020;146(10):2773–2783. doi: 10.1002/IJC.32610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mansori K, Moradi Y, Naderpour S, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection as a risk factor for diabetes: a meta-analysis of case-control studies. BMC Gastroenterol. 2020;20(1). doi: 10.1186/S12876-020-01223-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bui D, Brown HE, Harris RB, Oren E. Serologic evidence for fecal-oral transmission of Helicobacter pylori. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2016;94(1):82–88. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.15-0297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Courtney JG, Longnecker MP, Theorell T, de Verdier MG. Stressful life events and the risk of colorectal cancer. Epidemiology. 1993;4(5):407–414. doi: 10.1097/00001648-199309000-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jansson C, Johansson AL V, Jeding K, Dickman PW, Nyrén ON, Lagergren J. Psychosocial working conditions and the risk of esophageal and gastric cardia cancers. Cancer Epidemiol. 2004;19(7):631–641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Luu MN, Quach DT, Hiyama T. Screening and surveillance for gastric cancer: Does family history play an important role in shaping our strategy? Asia Pac J Clin Oncol. 2022;18(4):353–362. doi: 10.1111/AJCO.13704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Song M, Camargo MC, Weinstein SJ, et al. Family history of cancer in first-degree relatives and risk of gastric cancer and its precursors in a Western population. Gastric Cancer. 2018;21(5):729–737. doi: 10.1007/S10120-018-0807-0/TABLES/5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Choi YJ, Kim N. Gastric cancer and family history. Korean J Intern Med. 2016;31(6):1042. doi: 10.3904/KJIM.2016.147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lunet N, Lacerda-Vieira A, Barros H. Fruit and vegetables consumption and gastric cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Nutr Cancer. 2005;53(1):1–10. doi: 10.1207/S15327914NC5301_1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.González CA, Pera G, Agudo A, et al. Fruit and vegetable intake and the risk of stomach and oesophagus adenocarcinoma in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC-EURGAST). Int J cancer. 2006;118(10):2559–2566. doi: 10.1002/IJC.21678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhu R, Chen K, Zheng YY, et al. Meta-analysis of the efficacy of probiotics in Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(47):18013. doi: 10.3748/WJG.V20.I47.18013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tong JL, Ran ZH, Shen J, Zhang CX, Xiao SD. Meta-analysis: The effect of supplementation with probiotics on eradication rates and adverse events during Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;25(2):155–168. doi: 10.1111/J.1365-2036.2006.03179.X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Śliżewska K, Markowiak-Kopeć P, Śliżewska W. The role of probiotics in cancer prevention. Cancers (Basel). 2021;13(1):1–22. doi: 10.3390/CANCERS13010020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Javanmard A, Ashtari S, Sabet B, et al. Probiotics and their role in gastrointestinal cancers prevention and treatment; an overview. Gastroenterol Hepatol From Bed to Bench. 2018;11(4):284–295. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang SM, Freedman ND, Loftfield E, Hua X, Abnet CC. Alcohol consumption and risk of gastric cardia adenocarcinoma and gastric noncardia adenocarcinoma: A 16-year prospective analysis from the NIH-AARP diet and health cohort. Int J cancer. 2018;143(11):2749–2757. doi: 10.1002/IJC.31740 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lee M, Kemp JA, Canning A, Egan C, Tataronis G, Farraye FA. A randomized controlled trial of an enhanced patient compliance program for Helicobacter pylori therapy. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159(19):2312–2316. doi: 10.1001/ARCHINTE.159.19.2312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Eslami M, Yousefi B, Kokhaei P, et al. Are probiotics useful for therapy of Helicobacter pylori diseases? Comp Immunol Microbiol Infect Dis. 2019;64:99–108. doi: 10.1016/J.CIMID.2019.02.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Çekin AH, Şahintürk Y, Harmandar FA, Uyar S, Yolcular BO, Çekin Y. Use of probiotics as an adjuvant to sequential H. pylori eradication therapy: impact on eradication rates, treatment resistance, treatment-related side effects, and patient compliance. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2017;28(1):3–11. doi: 10.5152/TJG.2016.0278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kim N, ed. Helicobacter Pylori. Springer Singapore; 2016. doi: 10.1007/978-981-287-706-2/ [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Liou JM, Malfertheiner P, Lee YC, et al. Screening and eradication of Helicobacter pylori for gastric cancer prevention: the Taipei global consensus. Gut. 2020;69(12):2093–2112. doi: 10.1136/GUTJNL-2020-322368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rokkas T, Ekmektzoglou K, Graham DY. Current role of tailored therapy in treating Helicobacter pylori infections. A systematic review, meta-analysis and critical analysis. Helicobacter. 2022:e12936. doi: 10.1111/HEL.12936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.McElrath K, Martin M. Bachelor’s Degree Attainment in the United States: 2005 to 2019.; 2021. https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2021/acs/acsbr-009.pdf. Accessed December 17, 2022.

- 58.Bureau UC. Urban Areas Facts. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/geography/guidance/geo-areas/urban-rural/ua-facts.html. Published October 8, 2021. Accessed December 17, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Shrider EA, Kollar M, Chen F, Semega J. Income and Poverty in the United States: 2020 Current Population Reports.; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yank V, Agarwal S, Loftus P, Asch S, Rehkopf D. Crowdsourced Health Data: Comparability to a US National Survey, 2013–2015. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(8):1283–1289. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2017.303824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chey WD, Leontiadis GI, Howden CW, Moss SF. ACG Clinical Guideline: Treatment of Helicobacter pylori Infection. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112(2):212–238. doi: 10.1038/AJG.2016.563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Choi IJ, Kim CG, Lee JY, et al. Family history of gastric cancer and Helicobacter pylori treatment. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(5):427–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.