Abstract

A commercial carbon cloth (CC) was oxidized by HNO3 acid and the features of the plain and oxidized CC were evaluated. The results of characterization illustrated that HNO3 oxidization duplicated the oxygen-containing functional groups and the surface area of the CC. The adsorption performance of the plain and oxidized CC (Oxi-CC) toward benzotriazole (BTR) was compared. The results disclosed that the uptake of BTR by oxidized CC was greater than the plain CC. Thence, the affinity of oxidized CC toward BTR was assessed at different conditions. It was found that the adsorption was quick, occurred at pH 9 and improved by adding NaCl or CaCl2 to the BTR solution. The kinetic and isotherm studies revealed that the surface of Oxi-CC is heterogeneous and the adsorption of BTR follows a physical process and forms multilayer over the Oxi-CC surface. The regenerability and reusability study illustrated that only deionized water can completely regenerate the Oxi-CC and that the Oxi-CC can be reused for five cycles without any loss of performance. The high maximum adsorption capacity of Dubinin–Radushkevich isotherm model (252 mg/g), ease of separation and regeneration, and maintaining the adsorption capacity for several cycles revealed the high efficiency and economical and environmental feasibility of Oxi-CC as an adsorbent for BTR.

Subject terms: Environmental chemistry, Analytical chemistry

Introduction

The worldwide rapid industrial progress has introduced numerous synthetic chemicals in humans’ everyday life. The inefficient treatment of wastewater leads to the contamination of surface and ground water with several contaminants of emerging concerns (CECs). These CECs have deleterious effects on the environment, live beings and the natural balance of biomes1–5.

Benzotriazole (BTR, C6H5N3) is one of the CECs that is widely used as corrosion inhibitor, antifreeze, anti-fog, anti-rust, drug precursor, cooling and hydraulic fluid, UV absorber, and dishwashing detergent. Therefore, it is produced in large quantities. BTR is characterized by high water solubility (28 g/L) and bio-recalcitrance which limits its removal by the conventional water/wastewater treatment processes. The wide applications range, mass production and limited removal efficiency lead to the widespread detection of BTR in the aquatic environments. However, the high toxicity, ability to disrupt the endocrine system and long-term negative effects of BTR raised the public concerns towards its presence in the aquatic environments4,6–9. As a result, it is critical to use cutting-edge treatment methods to get rid of BTR from aquatic environments.

Advanced oxidation process10, membrane filtration11, biological processes12, combined processes13 have been applied to remove CECs from water/wastewater. However, amongst the different advanced treatment processes, adsorption has a well-established efficiency for the removal of hazardous contaminants in addition to its easy operation, economic feasibility, low-energy consumption, and insensitivity to toxic substances. Consequently, adsorption became the most widely applied4,7,14–18. So far, among the many materials that have been utilized as adsorbents, carbonaceous materials stand out because of their demonstrated affinity for various contaminants19,20. Activated carbon has three forms; granular, powdered and fibers, felts or cloth16,18. Unlike carbon cloth (CC), granular (GAC) and powdered activated carbons (PAC) suffer from the release of fine particles and dusts, and also, suffer from significant headloss due to their small grain size, and the accumulation of solid debris at the filter surface17,19.

Recently, CC has attracted significant consideration in water treatment because of its several advantages. Comparative to GAC and PAC, CC has superior mechanical and structural integrity, less diffusion limitations, ease of handling, straightforward recovery post-treatment, smaller reactor size, rapid adsorption kinetics and effectiveness similar to or even better than GAC and PAC14,16–18,20–22. In spite of these prominent merits, the application of CC for water treatment still limited, relative to GAC and PAC, till now23. Researchers are currently devoting efforts to reduce the cost of CC production, endow selectivity and specificity to a definite contaminant, evaluate its efficiency in multicomponent systems, among other topics24,25. However, enhancing the adsorption effectiveness of CC is one of the key challenges that could promote its practical application.

Most previous studies used plain commercial carbon cloth for the adsorption of organic contaminants16,18–20,22. Very few studies considered the modification of CC. For instance, Zulfiqar et al.3 prepared a porous activated carbon cloth modified by a silane polymer and applied it for the separation of oil/water mixtures. Generally, the pre-treatment processes of adsorbents aim to improve its adsorption performance via adding functional groups, increasing the surface area or both. Surface oxidation is an approach that introduces oxygen-containing functional groups on the material’s surface. These oxygen-containing functional groups are potential adsorption sites and increase the material’s hydrophilicity and wetting properties26.

To the best of our knowledge, the adsorption of the contaminant of emerging concern benzotriazole by oxidized carbon cloth has not been reported yet. Therefore, this study targets filling this literature gap. For the first time, this study aims at evaluating and improving the adsorption efficiency of a commercially available carbon cloth toward the adsorption of benzotriazole. The approach of introduction of new oxygen-containing functional groups on the surface of the commercially available carbon cloth to improve its adsorption efficiency was pursued in this study. A simple nitric acid hydrothermal process was followed to oxidize the commercial carbon cloth and introduce new oxygen-containing surface functional groups. Then, the chemical and textural properties of the plain and oxidized carbon cloth were finely characterized. A series of batch adsorption experiments were executed with the aim of evaluating the effect of nitric acid oxidation on the adsorption efficiency, finding the optimum conditions of the adsorption process, understanding the effect of ionic strength on the adsorption, testing the regeneration and reusability of the oxidized carbon cloth, and understanding the adsorption mechanism. Different kinetics and isotherm models were applied to describe the mechanism of adsorption.

Materials and methods

Materials

Carbon cloth (CC, ELAT-hydrophilic plain cloth) was purchased from fuel cell store. Nitric acid (HNO3, 69%), and benzotriazole (99%) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich.

Nitric acid hydrothermal oxidation

A piece (4 × 6 cm) of carbon cloth was immersed in 40 mL HNO3 (69%) contained in a 50 mL Teflon-lined stainless autoclave. The autoclave was sealed and maintained at 90 °C for 16 h. After cooling to room temperature naturally, the oxidized carbon cloth (Oxi-CC) was taken out and washed with copious amount of deionized water then dried.

Plain and oxidized carbon cloth characterization

The morphology and elemental composition of the plain and oxidized carbon cloth were investigated by field emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM, TESCAN VEGA 3) and energy dispersive X-ray analysis (EDX, Bruker), respectively. Before analysis, the samples were coated by gold using Quorum Q 150 ES (UK) magnetron sputtering machine. The functional groups were identified using attenuated total reflection Fourier transform infrared (ATR-FTIR, Jasco 4100). The N2 adsorption–desorption isotherms at 77 K was obtained using BELSORP-max surface analyzer. The samples were outgassed at 150 °C overnight before analysis. The specific surface area (SBET) was calculated according to Brunauer–Emmett–Teller and the pore size distribution was determined by nonlocal density functional theory (NLDFT) from the N2 adsorption isotherm. The diameter of the carbon fibers was determined manually using ImageJ 1.54b software. The point of zero charge was determined according to the salt addition method27.

Evaluation of adsorption performance

Before performing the adsorption experiments, a series of working solutions of BTR were prepared by proper dilution of 100 mg/L stock solution. All solutions were prepared using deionized water obtained from Milli-Q water purification system. The UV spectra of the working solutions were recorded using a double-beam UV–Vis spectrophotometer (JASCO V730, Japan) and are shown in Fig. S1a. As given by the Figure, the absorption maximum is located at 273 nm. A nine-point standard curve was established by plotting the absorbance at 273 nm vs. concentration (Fig. S1b). A straight line with high coefficient of determination (R2 = 0.999) was obtained over the concentration range 0–100 mg/L. Therefore, this standard curve was used to convert the absorbance of unknown samples to concentration.

The adsorption experiments were conducted in batch mode using an orbital shaker incubator (DAIHAN ThermoStable™ IS-30, Korea) at 200 rpm and 26 °C. In a typical experiment, precisely weighed pieces of carbon cloth were added in Erlenmeyer flasks containing BTR solution. After a determined time, the concentration of BTR was determined and the amount of BTR adsorbed per gram of carbon cloth (q, mg/g) and removal percentage (R%) were calculated by Eqs. (1) and (2), respectively:

| 1 |

| 2 |

wherein Co and Ct (mg/L) are the concentrations of BTR before the beginning of the experiment and after contact with the carbon cloth for t (min), respectively, V (L) is the volume of BTR solution, and w (g) is the mass of the carbon cloth piece.

The effects of initial pH (pHo) of BTR solution, ionic strength, adsorption time, initial concentration of BTR solution and reusability of the carbon cloth were evaluated using the aforementioned procedure. In the pHo effect study, the pHo of 50 mL BTR solution (20 mg/L) was adjusted to 3, 5, 7, and 9 then contacted with 50 mg of carbon cloth. Samples were collected periodically and the concentrations of BTR were measured. In the ionic strength effect study, a specific amount of the NaCl or CaCl2 (25–300 mg/L) was added to 50 mL BTR solution (20 mg/L) pre-adjusted to the optimum pHo then the BTR solution was contacted with 50 mg of carbon cloth. In the initial concentration effect study, 50 mg of carbon cloth was added to a series of 50 mL BTR solutions of different initial concentrations (5–45 mg/L). After contacting for 2 h, the remaining concentrations of BTR were measured. In the reusability study, the exhausted carbon cloth was regenerated by shaking with deionized water for 1 h before reusing for another adsorption cycle. The regeneration efficiency was calculated according to Eqs. (S4) and (S5). Each adsorption experiment was performed three times under the same conditions. The reported results are the average of the triplicate analysis.

The obtained adsorption kinetic and isotherm data were treated with the nonlinear forms of the common adsorption mathematical models in order to explore the adsorption mechanism. The tested kinetic and isotherm models are given in details in the supporting information. The validity of the tested kinetic and isotherm models was evaluated based on several error functions as discussed in the supporting information. OriginPro 2021 software was used for graphing, and analysis of the data.

Results and discussions

Characteristics of the plain and oxidized carbon cloth

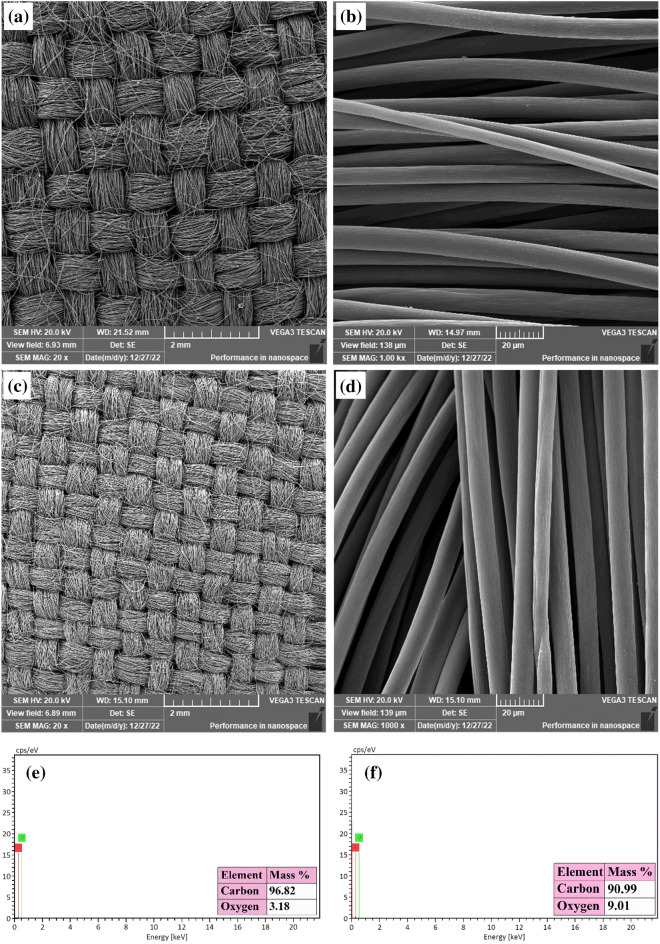

With the aim of increasing the potential adsorption site, a commercially available plain carbon cloth was treated with nitric acid. The nitric acid treatment results in the oxidation of carbon atoms on the surface of carbon cloth where the C–C and/or the C–H bonds are oxidized to C–O bonds. Thus, nitric acid treatment increases the oxygen-containing functional groups such as –C=O, –C–O, and –COOR28 which are potential adsorption sites. The morphology of the plain and oxidized carbon cloth is displayed in Fig. 1. The plain carbon cloth (Fig. 1a) is made out of many carbon fibers that are gathered to form very similar woven braids. The individual carbon fibers have a smooth surface that is free of pores, defects and grooves. The diameters of the carbon fibers were determined from the high magnification image (Fig. 1b) and found to range between 5.5 and 9.7 µm.

Figure 1.

SEM micrographs and EDX spectra of plain (a,b,e) and oxidized (c,d,f) carbon cloth.

The SEM images of the oxidized carbon cloth displayed in Fig. 1c,d indicate that the oxidation process has not changed the structure and morphology of the carbon cloth. Cheng et al.28 and Moloudi et al.29 have reported similar observation before.

The elemental composition of the carbon cloth was determined before and after the oxidation process by EDX analysis. The EDX spectra of both plain and oxidized carbon cloth (Fig. 1e,f, respectively) show the presence of the peaks of oxygen and carbon elements. The inset tables of Fig. 1e,f show the mass percentage of carbon and oxygen. It can be seen that the mass percentage of oxygen in the oxidized carbon sample is 2.8 times that of the plain carbon cloth. This result indicates increasing the content of oxygen-containing functional groups in the oxidized carbon cloth which implies the success of the oxidation process.

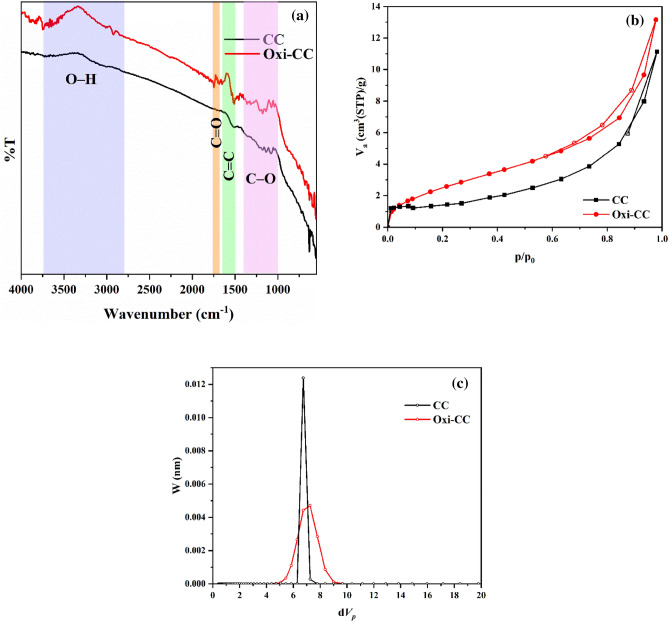

The surface functional groups of the plain and oxidized carbon cloth were assessed using FTIR analysis and the spectra are presented in Fig. 2a. The IR spectrum of the plain CC revealed the presence of aliphatic and aromatic hydrocarbons in addition to few oxygen-containing functional groups. Specifically, the weak broad peaks around 3700 cm−1 and 3040 cm−1 are assignable to the stretching vibration of O–H and =C–H of aliphatic or aromatic hydrocarbons, respectively3. The peak at 1519 cm−1 is for aromatic C=C bending3,30. The peak at 1460 cm−1 results from the –C–H bending vibration of CH3 and CH2 groups. The peaks in the range 1000–1400 cm−1 can be ascribed to the stretching vibration of the C–O bond29. The band at around 610 cm−1 is due to the C–H bond of the –C≡C–H.

Figure 2.

FTIR spectra (a), N2 adsorption–desorption isotherms (b), and NLDFT pore size distribution (c) of plain (CC) and oxidized (Oxi-CC) carbon cloth.

Clear differences between the spectra of the plain and oxidized carbon cloth can be noticed. Altogether, the intensifying and appearance of additional peaks related to the oxygen-containing functional groups and the receding of the intensity of the peaks related to the carbon atoms can be observed in the spectrum of the oxidized carbon cloth. Specifically, the intensity of the peaks at 3700 cm−1 (O–H stretching), and at the range 1000–1400 cm−1 (C–O stretching) was increased. Additional prominent peaks related to the stretching vibration of O–H, C=O (of carboxylic acids amides, ketones, aldehydes, lactone, or esters), and aromatic C=C groups appeared at 2916 cm−1, 1740–1685 cm−130, and 1540 cm−1, respectively. The appearance of these peaks proves the oxidation of plain carbon cloth. In addition, it can be noted that the intensity of the band for the C–H bond of the –C≡C–H decreased after the oxidation process which indicates the oxidation of the C–H bonds. All in all, the FT-IR results give solid evidence for the successful oxidation and increasing the oxygen-containing functional groups of the carbon cloth. This result is in accordance with earlier studies that found carbon cloth’s content of oxygen-containing functional groups increased as a result of oxidation29–33.

The surface area and porous structure of a material is an important property which affect its adsorption efficiency. Therefore, the N2 adsorption–desorption isotherms of the plain and oxidized carbon cloth were measured and used to determine their surface area, pore volume, pore size and pore size distribution. Figure 2b shows the obtained N2 adsorption–desorption isotherms.

The first step in the interpretation of physisorption isotherm is to define the type of the isotherm34. The type of the isotherm identifies the nature of the adsorption process. The International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) categories physisorption isotherms into six groups34,35. Herein, the physisorption isotherms of both the plain and oxidized carbon cloth presented in Fig. 4a are concave to the p/p0 axis at low p/p0 and convex afterward. This shape matches well with the reversible type II isotherm which characterizes the nonporous or microporous materials and implies unrestricted mono-/multi-layer adsorption. In addition, the presence of hysteresis loops in the physisorption isotherms of plain and oxidized carbon cloth is depicted in Fig. 2b. The observation that the hysteresis loops have the lower limit of desorption branches at the cavitation-induced p/p0 indicates that these loops are of the H3 type.

Figure 4.

Experimental and models’ fitted curves of the adsorption (a) kinetics and (b) isotherm.

The Brunauer, Emmett and Teller (BET) method was applied to determine the specific surface area (SBET) and total pore volume (Vtot) of the plain and oxidized carbon cloth. The calculated SBET and Vtot of plain carbon cloth were 5.2 m2/g and 0.017 cm3/g, respectively, while those of oxidized carbon cloth were 10.2 m2/g and 0.020 cm3/g, respectively. These results indicate that the oxidation of the plain carbon cloth increased the surface area and total pore volume significantly which agrees with literature. Previously, Vautard et al.36, Gao and Zhao37, and Pittman et al.38 reported that oxidation of carbon fibers by nitric acid increases the surface area and oxygen-containing functional groups.

The pore size distribution of the plain and oxidized carbon cloth was determined from the N2 adsorption isotherm by the non-local density functional theory (NDLFT) model. Figure 2c shows the obtained pores size distribution curves. Both the plain and oxidized carbon cloth is mainly mesoporous with a mean pore diameter of 6.7 nm and 7.2 nm, respectively. Moreover, the pore size distribution curve of the oxidized carbon cloth is relatively wider than that of the plain carbon cloth. This might be due to widening the distance between the carbon fibers by the nitric acid during the oxidation process.

Joining the observed morphology (Fig. 1), physisorption isotherm type (Fig. 2b), and the pore size distribution curves (Fig. 2c) indicates that the fibers of both plain and oxidized carbon cloth are nonporous and the distances between the fibers form mesopores.

Adsorption of benzotriazole

The characteristics of carbon cloth such as lightweight, compactness, high hydraulic conductivity, low mass transfer resistances, and ease of arrange in a variety of stable configurations simplify and encourage its practical application19,25. The effectiveness of the plain and oxidized carbon cloth for the adsorption of benzotriazole from aqueous solutions was tested. This experiment was performed using 1 g/L of CC or Oxi-CC, and 20 mg/L BTR solution adjusted to pHo 9. Figure 3 presents the results. It is abundantly clear that the removal of BTR by both CC and Oxi-CC was quite fast. The amount of adsorbed BTR increased sharply after the first contact with either CC or Oxi-CC then remained unchanged thereafter. Previously, Xu et al.4 reported a similar pattern for the adsorption of BTR by Zn–Al–O binary metal oxide where the amount of adsorbed BTR increased steeply to 0.26 mg/g after the first contact then remained constant. In general, it is recognized that the adsorption kinetic by CC is fast due to the small diameters of its consisting fibres25. Notably, the amount of BTR adsorbed by the Oxi-CC (6.53 mg/g) was considerably higher than that adsorbed by the CC (5.51 mg/g). This observation signifies the role of oxidation process in enhancing the adsorption performance of carbon cloth. Thus, the mechanism and factors affecting the adsorption of BTR by Oxi-CC was further explored.

Figure 3.

(a) Removal of BTR by CC and Oxi-CC, (b,c) effect of pHo on BTR removal by Oxi-CC, and (d) pHPZC of Oxi-CC.

The solution pH affects the surface charges of the adsorbent and ionization of the adsorptive. Thus, it mostly plays a critical role in the adsorption process. Figure 3b depicts the data obtained for the adsorption of BTR by 1 g/L of Oxi-CC at different pHo as a function of contact time. The results show that Oxi-CC can adsorb 6.81 mg/g of BTR at pHo 9, while at pHo ranging from 3 to 7 relatively little adsorption takes place.

The surface charge of the Oxi-CC was investigated at different pH values in order to explain the results of pH effect study. The difference between the initial and final pH vs. the initial pH is plotted in Fig. 3c. The figure shows that the surface of Oxi-CC has a pHPZC of 2.1. Thus, the surface of Oxi-CC has a net electronegative charge under the studied pH range. On the other side, BTR behaves as a weak base (pKa = 1.6) and a weak acid (pKa = 8.6)4,6,9, therefore, it has three forms in aqueous solutions as displayed in Scheme 1. It exists in the protonated form (BTRH2+) at pH < 1.6, molecular (unionized) form at pH between 1.6 and 8.6, and deprotonated form (BTR−) at pH > 8.6. Thus, under the experimental conditions, BTR exist in the molecular form in the pHo range 3–7 and the deprotonated form at pHo 9.

Scheme 1.

Forms of benzotriazole at different pH values.

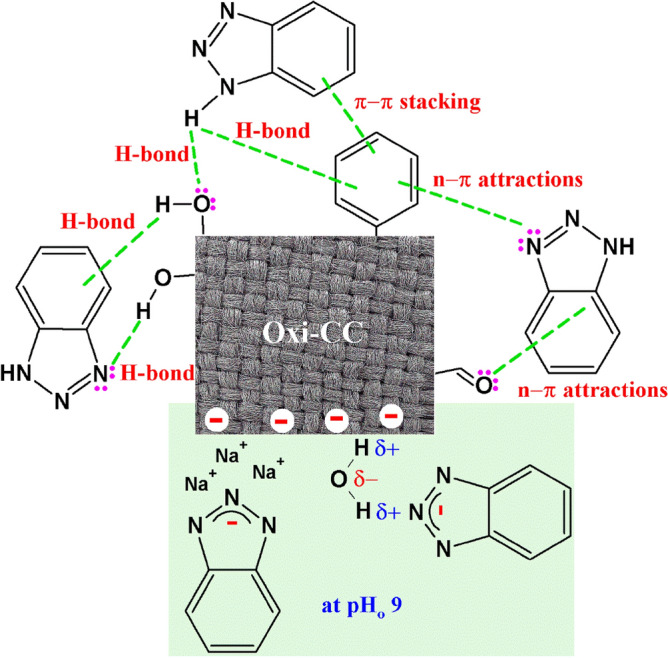

In general, the adsorption of aromatic compounds can be driven by one or more of electrostatic attractions, ion exchange, hydrogen-bond interactions, hydrophobic interactions, Van der Waals’ interactions, dipole–dipole interactions, and π–π stacking4,39. As illustrated above, at pHo 3–7, BTR exists in the molecular form and the Oxi-CC has a net negative charge. So, electrostatic attraction mechanism can be excluded. The FTIR of the Oxi-CC revealed the presence of aliphatic and aromatic hydrocarbons as well as oxygen-containing functional groups. Therefore, in this study, the possible interactions between the BTR and the Oxi-CC, presented in Scheme 2, are (a) π–π stacking between the π electrons of the aromatic rings of BTR and the Oxi-CC, (b) hydrogen-bond interactions between (i) the hydrogen of the –NH group and of BTR and either the benzene rings (Yoshida hydrogen-bond) or the oxygen containing functional groups of the Oxi-CC (dipole–dipole hydrogen-bond), and (ii) the hydrogen of the –OH groups on the surface of Oxi-CC and the benzene ring of BTR or the triazole nitrogen atoms, and (c) n-π electron donor–acceptor interaction between (i) the lone electron pair of the triazole nitrogen atoms and the aromatic rings on the Oxi-CC surface and (ii) the lone electron pair of the carbonyl groups of the Oxi-CC and the benzene ring of BTR. Beforehand, Hu et al.9 reported that hydrogen bonding drives the adsorption of BTR onto Zn-Al layered double oxide. Likewise, Hasanzadeh et al.40 and Sarker et al.41 reported that a combination of hydrophobic interactions, π–π stacking and electrostatic interactions underlies the adsorption of BTR onto modified magnetic biochar and Co-based metal azolate framework, respectively.

Scheme 2.

Some probable interactions between Oxi-CC and BTR.

It is known that pH has insignificant effect on the hydrophobic and π–π interactions40,41. So, relatively slight change in the amount adsorbed can be observed in the pHo range 3–7. At pHo 9, electrostatic repulsion between the deprotonated form of BTR and the negative charges on the surface of Oxi-CC is predicted to dominates. Surprisingly, a considerably increase in the amount adsorbed can be observed at pHo 9. Similarly, Hu et al.9 reported that Zn-Al layered double oxides adsorb a significant amount of BTA at pH > 8, despite the predicted repulsive forces between the Zn-Al layered double oxides and BTR, and attributed this observation to the involvement of a mechanism other than electrostatic interactions in the adsorption process without further clarifications.

A possible explanation of the observed increase in adsorption efficiency at pHo 9 is the involvement of like-charge attraction mechanism. In general, the mechanism of like-charge attraction still ambiguous, however, bridging water, bridging counter-ions, and counter-ions bonded to only one of the like-charge ions are commonly debated as the underlying forces for the like-charge attraction42. Monovalent counter-ions can bound to the like-charge species hence screen the charge and diminish the electrostatic repulsion. But to generate attraction, non-electrostatic attraction must be involved. On the other side, multivalent counter-ions can invert the charge by bounding to one of the like-charged species and/or act as a bridge by bounding to both like-charge species. Thus, drives the like-charged attraction without the need for other attraction mechanisms42–44. In the present study there are two probable reasons for the observed like-charged attraction. First, the Na+ ions introduced to the medium during the adjustment of pHo weaken the repulsive forces between the negatively charged Oxi-CC and the deprotonated form of BTR by the screening effect of Na+ ions44 (Scheme 2). Such weakening of the repulsive forces lets the hydrophobic and π–π interactions take place and drive the adsorption process. Second, the polar water molecules can mediate the attraction between the like-charged Oxi-CC and BTR. The slightly positive charge on hydrogen atoms of the water molecules can act as a bridge between the like-charged Oxi-CC and deprotonated BTR (Scheme 2). It has been reported previously that water molecules can invert the electrostatic repulsion into electrostatic attraction45. In both cases, the suggested like-charge adsorption mechanism highpoints the significance of non-electrostatic forces46.

To elucidate the involvement of hydrophobic attractions, like-charge attraction mechanism and the important role of cations on the adsorption of BTR onto Oxi-CC, the effect of both monovalent and divalent cations was investigated. Na+ and Ca2+ were used as representatives for monovalent and divalent cations, respectively. The results showed that the addition of 25 mg/L of either NaCl or CaCl2, increased the value of qe by 15% (7.85 mg/g) or 16% (7.92 mg/g), respectively. However, the value of qe insignificantly changed by further addition of NaCl and gradually increased by further addition of CaCl2 reaching 8.14 mg/g (20% increment) at 300 mg/L CaCl2. These results prove that the presence of monovalent or divalent cations diminishes the predicted electrostatic repulsion between the anionic BTR and the negatively charged Oxi-CC (at pHo 9) and enables and increases the hydrophobic attractions. The slightly higher improvement of adsorption efficiency in case of Ca2+ suggests that it might contribute in the adsorption by act as bridge via bounding to both deprotonated BTR and negatively charged Oxi-CC. It is widely reported that increasing the ionic strength causes an increase in the hydrophobic attractions and decreases the electrostatic interactions47,48.

The adsorption process was performed as a function of contact time to determine the equilibrium time. It is obvious from Fig. 4a that the adsorption of BTR onto the Oxi-CC is instantaneous where the equilibrium state was only attained after 15 min. This fast adsorption can be ascribed to the abundance of adsorption sites and the large concentration gradient at the start of the adsorption process which promoted the migration of BTR from the aqueous to the solid phase and have reduced the mass transfer8. This fast adsorption suggests that the adsorption of BTR by the Oxi-CC occurs thru external surface adsorption4. Noteworthy that relative to previous studies on BTR adsorption, the equilibration time in this study was considerably short. For example, Hu et al.9 reported that the equilibrium state for the adsorption of BTR onto Zn-Al layered double oxide was 160 min. Xu et al.4 reported an equilibrium time of 30 min for the adsorption of BTR by Zn–Al–O binary metal oxide adsorbent. Furthermore, the amount of BTR adsorbed at equilibrium by the Oxi-CC (6.81 mg/g) was considerably higher than several other adsorbents in the literature. Yu et al.8 reported that the adsorption capacity of polyvinyl chloride microplastics toward BTR at equilibrium was 0.0626 mg/g. Xu et al.4 obtained an equilibrium adsorption capacity of 0.26 mg/g for BTR using Zn–Al–O binary metal oxide. Hongling et al.7 obtained a maximum equilibrium adsorption capacity of 1.28 mg/g for BTR adsorption using Ca-montmorillonite (Ca-Mt). However, there are some other reported powdered adsorbents that have higher equilibrium adsorption capacity than Oxi-CC. For example, Hongling et al.7 reported a maximum equilibrium adsorption capacity of 18.89 mg/g and 13.86 mg/g for propylbis (dodecyldimethyl) ammonium chloride and propylbis (octadecyldimethyl) ammonium chloride modified Ca-Mt, respectively. Undoubtedly, powdered adsorbents normally have higher adsorption capacity than immobilized ones, so comparing the efficiency of powdered adsorbents to Oxi-CC isn’t logical.

To further investigate the kinetics of adsorption and get some details about the adsorption mechanism, the experimental kinetic data was fitted to the pseudo-first-order (PFO)49, pseudo-second-order (PSO)50, and Elovich51 models. The fit curves are depicted in Fig. 4a and the resulting parameters besides the coefficient of determination (R2), chi-square (χ2), and root mean square error (RMSE) are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Parameters of the applied kinetics and isotherm models.

| Kinetic models | Isotherm models | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| PFO | Freundlich | ||

| R2 | 0.9988 | R2 | 0.9872 |

| χ2 | 0.008 | χ2 | 0.00003 |

| RMSE | 0.09 | RMSE | 0.0053 |

| k1 | 0.45 ± 0.03 | KF | 10.49 ± 3.54 |

| qe | 6.72 ± 0.04 | nF | 0.30 ± 0.02 |

| PSO | Langmuir | ||

| R2 | 0.9983 | R2 | 0.6528 |

| χ2 | 0.011 | χ2 | 0.00075 |

| RMSE | 0.11 | RMSE | 0.0274 |

| k2 | 0.23 ± 0.04 | KL | 2.83 × 10–4 ± 3.68 |

| qe | 6.82 ± 0.05 | qL | 1.06 × 103 ± 1.38 × 107 |

| Elovich | D–R | ||

| R2 | 0.9945 | R2 | 0.9901 |

| χ2 | 0.036 | χ2 | 0.00002 |

| RMSE | 0.19 | RMSE | 0.0046 |

| α | 3.70 × 1012 ± 4.43 × 1013 | KD–R | 0.19 ± 0.01 |

| β | 5.16 ± 1.87 | qD–R | 2.12 ± 0.45 |

| Sips | |||

| R2 | 0.9906 | ||

| χ2 | 0.00002 | ||

| RMSE | 0.0049 | ||

| KS | 486.97 ± 1093.54 | ||

| nS | 4.63 ± 1.04 | ||

| qS | 0.25 ± 0.12 | ||

The values of the R2, χ2, and RSME obtained for the different kinetic models were compared in order to determine the suitability of the models to the experimental kinetic data and the most compatible model. The values of R2 were higher than 0.99 for all of the tested kinetic models which indicate that the three models can predict the experimental data. This observation implies that a sophisticated mechanism triggered the adsorption process. Noticeably, the value of R2 was slightly higher for the PFO and the values of χ2, and RSME were the lowest among the studied models. Therefore, it can be concluded that the kinetics of BTR adsorption onto Oxi-CC is more fitted to the PFO model. Several previous studies found that the PFO gives the better fit for their kinetic data20,52. The PFO model is based on a direct proportion between the rate of adsorption and the difference in equilibrium concentration and the amount adsorbed with time52. Also, the PFO is common for adsorption systems in which adsorption occur via diffusion thru the interface and physisorption is the rate determining step53–55.

Adsorption isotherm describes the relation between the concentration of adsorptive in the liquid and solid phases. It is essential for the design of adsorption process and to understand the interactions between the adsorptive and adsorbent. In this study, the adsorption isotherm was determined in batch mode at 26 °C using 1 g/L of the Oxi-CC and different initial concentrations (5–45 mg/L) of BTR solution adjusted to pHo 9. The obtained experimental adsorption isotherm displayed in Fig. 4b shows that the amount adsorbed of BTR increases with increasing the initial concentration of BTR solution. The experimental adsorption isotherm belongs to the S-type sub-group 1 of Giles classification56. The S-type sub-group 1 isotherm indicates that the initial adsorption of BTR facilitates the adsorption of more BTR and high initial concentration of BTR enhances the adsorption. Also, it indicates that the adsorbed BTR is vertically oriented on the surface of Oxi-CC and surface saturation has not been attained. Xu et al.4 reported S-type isotherm for the adsorption of BTR onto Zn–Al–O binary metal oxide.

The non-linear forms of four isotherm models, namely, Langmuir57, Freundlich58, Dubinin–Radushkevich (D–R)59, and Sips60 were used to analyze the experimental adsorption isotherm. The regression plots of the applied isotherm models are shown in Fig. 4b and the calculated values of both models’ parameters and goodness-of-fit functions are listed in Table 1. Visual examination of Fig. 4b shows that among the applied adsorption isotherms, Langmuir model cannot fit the experimental adsorption isotherm data. This observation is supported by the calculated values of R2. Freundlich, D–R, and Sips models have R2 values greater than 0.98 while Langmuir has R2 of 0.65. Thus, the R2 values indicate the good fit of the Freundlich, D–R, and Sips models and the poor fit of Langmuir model. Moreover, the values of the goodness-of-fit indicators are consistent with this conclusion where very minor differences of χ2, and RSME for Freundlich, D–R, and Sips models can be observed. The common character of the Freundlich, D–R, and Sips models is that they can describe multilayer adsorption onto a heterogeneous surface. Each of these models provides additional information about the nature of the adsorption process. Freundlich model assumes interactions between adsorbates and increasing the amount adsorbed with increasing the adsorptive initial concentration58. The D–R model assumes a key role of Van der Waal’s forces in the formation of multilayer and enables the determination of whether the adsorption is a physical or a chemical process59. It is argued that the adsorption is dominated by physical process when the mean adsorption free energy is less than 8 kJ/mol and chemical process when E is greater than 8 kJ/mol55,61. In this work, the calculated value of E is 1.62 kJ/mol. Therefore, the adsorption of BTR onto the Oxi-CC is mainly physical process. This inference is consistent with the findings of the kinetic study, which indicated that the rate-determining step is physisorption. The D–R model also provides valuable data about the maximum adsorption capacity of a material (the parameter qD–R). The calculated value of qD–R in this study is 2.12 ± 0.45 mmol/g (252.33 ± 53.54 mg/g). This value is 235 times than what Xu et al.4 reported (1.07 mg/g), demonstrating the high efficiency of the Oxi-CC for the removal of BTR. Regrettably, the value of qD–R for removing BTR using other adsorbents has not been found in the literature. The Sips exponent (ns) is commonly used to derive the heterogeneity factor (mS = 1/nS) which defines the heterogeneity of the adsorbent surface. The value of mS ranges between 0 and 1, an mS of 1 indicates a homogeneous surface while a value less than 1 indicates a heterogeneous surface62,63. In this work, the calculated mS is 0.26 revealing the heterogeneous nature of the surface of Oxi-CC. To sum up, the isotherm study indicated that the Oxi-CC has a heterogeneous surface with high adsorption affinity toward BTR adsorption. And that BTR adsorbs onto Oxi-CC via a physical process and forms multilayer.

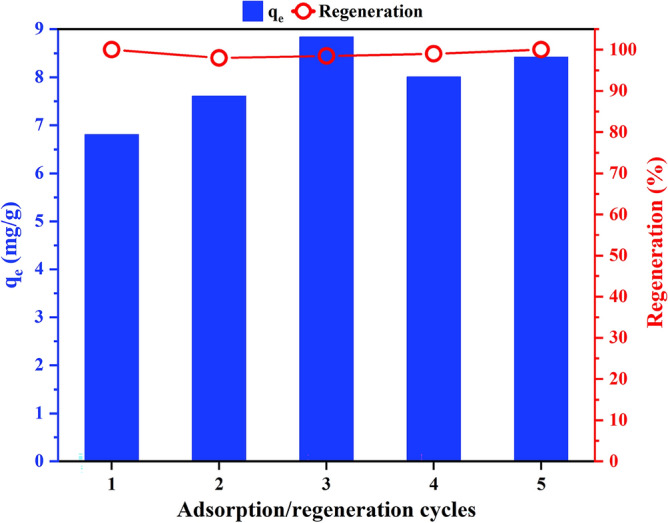

The reusability is one of the critical features that determine the feasibility of practical application of an adsorbent64. A reusable adsorbent reduces both the cost of the adsorption process and the generated solid waste65. The primary requirement of a reusable adsorbent is regenerability. In the regeneration step the adsorption sites are freed-up from the occupying adsorbate molecules thus restoring the adsorption capacity. It is argued that only water can regenerate an adsorbent when the adsorption process is physisorption66. Therefore, based on the results of the kinetic and isotherm studies, deionized water was selected as the eluent in this study. Figure 5 shows that the adsorbed BTR can be nearly completely desorbed from the Oxi-CC using deionized water as the regeneration efficiency ranged between 98 and 100%. Also, it can be observed that the Oxi-CC retained it adsorption capacity after five cycles. The adsorption capacity in the first cycle was 6.81 mg/g and increased in the range 7.61 mg/g to 8.84 mg/g from the second to the fifth cycle. Previous researchers65,67 reported an increase in the adsorption capacity of other adsorbents relative to that of the first cycle.

Figure 5.

Adsorption/regeneration cycles of Oxi-CC for BTR adsorption.

Conclusions

Carbon cloth has several attracting characteristics that encourage its application in water/wastewater treatment. Enhancing the adsorption characteristics of the carbon cloth and understating the adsorption mechanism is required to enable its practical application. In this study, HNO3 acid oxidation of a commercial carbon cloth introduced oxygen-containing functional groups and increased the surface area. Enhancing these features lead to improving the adsorption affinity toward benzotriazole. The adsorption of benzotriazole onto the oxidized carbon cloth was fast and occurred via surface adsorption at pH 9. Increasing the ionic strength of the benzotriazole solution improved the adsorption efficiency, and proved the involvement of like-charge and non-electrostatic attraction mechanisms. The pseudo-first-order model was the most compatible with the adsorption kinetics data. While the adsorption isotherm data was predicted efficiently by Freundlich, D–R, and Sips models. The regeneration and reuse study revealed that the Oxi-CC can be easily generated using deionized water and can be reused for five cycles without loss of adsorption capacity. Overall, the kinetic, isotherm, and regeneration studies indicated that BTR adsorbs perpendicularly onto the heterogeneous surface of Oxi-CC via physical interactions involving Van der Waal’s forces and forms multilayer. Conclusively, oxidized carbon cloth has great potential for practical application in water/wastewater treatment by the virtue of its high adsorption efficiency, ease of separation post-treatment, ease of regeneration, and reusability.

Supplementary Information

Author contributions

E.K.R: conceptualization, methodology, investigation, formal analysis, resources, visualization, funding acquisition and writing—original draft preparation. R.A.O: conceptualization, methodology, investigation, formal analysis, visualization and writing—review & editing. A.S.M.: conceptualization, methodology, and writing—review & editing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Open access funding provided by The Science, Technology & Innovation Funding Authority (STDF) in cooperation with The Egyptian Knowledge Bank (EKB). This paper is based upon work supported by Science, Technology & Innovation Funding Authority (STDF) under Grant Number 43115.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its Supplementary Information file.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-023-44067-w.

References

- 1.Radwan EK, Ibrahim MBM, Adel A, Farouk M. The occurrence and risk assessment of phenolic endocrine-disrupting chemicals in Egypt’s drinking and source water. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020;27:1776–1788. doi: 10.1007/s11356-019-06887-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Radwan EK, Abdel Ghafar HH, Ibrahim MBM, Moursy AS. Recent trends in treatment technologies of emerging contaminants. Environ. Qual. Manag. 2023;32:7–25. doi: 10.1002/tqem.21877. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zulfiqar U, et al. Flexible nanoporous activated carbon for adsorption of organics from industrial effluents. Nanoscale. 2021;13:15311–15323. doi: 10.1039/D1NR03242A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xu B, Wu F, Zhao X, Liao H. Benzotriazole removal from water by Zn–Al–O binary metal oxide adsorbent: Behavior, kinetics and mechanism. J. Hazard. Mater. 2010;184:147–155. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2010.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jagini S, et al. Emerging contaminant (Triclosan) removal by adsorption and oxidation process: Comparative study. Model. Earth Syst. Environ. 2021;7:2431–2438. doi: 10.1007/s40808-020-01020-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li P, et al. Efficient preparation and molecular dynamic (MD) simulations of Gemini surfactant modified layered montmorillonite to potentially remove emerging organic contaminants from wastewater. Ceram. Int. 2019;45:10782–10791. doi: 10.1016/j.ceramint.2019.02.152. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang H, Xia M, Wang F, Li P, Shi M. Adsorption properties and mechanism of montmorillonite modified by two Gemini surfactants with different chain lengths for three benzotriazole emerging contaminants: Experimental and theoretical study. Appl. Clay Sci. 2021;207:106086. doi: 10.1016/j.clay.2021.106086. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yu Y, et al. Exploring the adsorption behavior of benzotriazoles and benzothiazoles on polyvinyl chloride microplastics in the water environment. Sci. Total Environ. 2022;821:153471. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.153471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hu M, Yan X, Hu X, Feng R, Zhou M. High-capacity adsorption of benzotriazole from aqueous solution by calcined Zn–Al layered double hydroxides. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2018;540:207–214. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfa.2018.01.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dong T, et al. N-doped porous bowl-like carbon with superhigh external surface area for ultrafast degradation of bisphenol A: Key role of site exposure degree. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023;445:130562. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2022.130562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Foureaux AFS, et al. Rejection of pharmaceutical compounds from surface water by nanofiltration and reverse osmosis. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2019;212:171–179. doi: 10.1016/j.seppur.2018.11.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dubey M, Vellanki BP, Kazmi AA. Removal of emerging contaminants in conventional and advanced biological wastewater treatment plants in India—A comparison of treatment technologies. Environ. Res. 2023;218:115012. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2022.115012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ji J, et al. Anaerobic membrane bioreactors for treatment of emerging contaminants: A review. J. Environ. Manag. 2020;270:110913. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2020.110913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.López-Ramón MV, et al. Removal of bisphenols A and S by adsorption on activated carbon clothes enhanced by the presence of bacteria. Sci. Total Environ. 2019;669:767–776. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.03.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tongur T, Ayranci E. Adsorption and electrosorption of paraquat, diquat and difenzoquat from aqueous solutions onto activated carbon cloth as monitored by in-situ UV–Visible spectroscopy. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2021;9:105566. doi: 10.1016/j.jece.2021.105566. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Duman O, Ayranci E. Adsorptive removal of cationic surfactants from aqueous solutions onto high-area activated carbon cloth monitored by in situ UV spectroscopy. J. Hazard. Mater. 2010;174:359–367. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2009.09.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Masson S, et al. Single, binary, and mixture adsorption of nine organic contaminants onto a microporous and a microporous/mesoporous activated carbon cloth. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2016;234:24–34. doi: 10.1016/j.micromeso.2016.07.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ayranci E, Hoda N. Adsorption kinetics and isotherms of pesticides onto activated carbon-cloth. Chemosphere. 2005;60:1600–1607. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2005.02.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cosgrove S, Jefferson B, Jarvis P. Application of activated carbon fabric for the removal of a recalcitrant pesticide from agricultural run-off. Sci. Total Environ. 2022;815:152626. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.152626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ayranci E, Hoda N. Studies on removal of metribuzin, bromacil, 2,4-D and atrazine from water by adsorption on high area carbon cloth. J. Hazard. Mater. 2004;112:163–168. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2004.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Martin-Gullón I, Font R. Dynamic pesticide removal with activated carbon fibers. Water Res. 2001;35:516–520. doi: 10.1016/S0043-1354(00)00262-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marques SCR, Marcuzzo JM, Baldan MR, Mestre AS, Carvalho AP. Pharmaceuticals removal by activated carbons: Role of morphology on cyclic thermal regeneration. Chem. Eng. J. 2017;321:233–244. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2017.03.101. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Masson S, et al. Thermodynamic study of seven micropollutants adsorption onto an activated carbon cloth: Van’t Hoff method, calorimetry, and COSMO-RS simulations. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2017;24:10005–10017. doi: 10.1007/s11356-016-7614-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gopinath A, Kadirvelu K. Strategies to design modified activated carbon fibers for the decontamination of water and air. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2018;16:1137–1168. doi: 10.1007/s10311-018-0740-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cukierman AL. Development and environmental applications of activated carbon cloths. ISRN Chem. Eng. 2013;2013:261523. doi: 10.1155/2013/261523. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ros TG, van Dillen AJ, Geus JW, Koningsberger DC. Surface oxidation of carbon nanofibres. Chemistry. 2002;8:1151–1162. doi: 10.1002/1521-3765(20020301)8:5<1151::AID-CHEM1151>3.0.CO;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Appel C, Ma LQ, Rhue RD, Kennelley E. Point of zero charge determination in soils and minerals via traditional methods and detection of electroacoustic mobility. Geoderma. 2003;113:77–93. doi: 10.1016/S0016-7061(02)00316-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cheng N, et al. Acidically oxidized carbon cloth: A novel metal-free oxygen evolution electrode with high catalytic activity. Chem. Commun. 2015;51:1616–1619. doi: 10.1039/C4CC07120D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moloudi M, et al. Bioinspired polydopamine supported on oxygen-functionalized carbon cloth as a high-performance 1.2 V aqueous symmetric metal-free supercapacitor. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2021;9:7712–7725. doi: 10.1039/D0TA12624A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alvarado Ávila MI, Toledo-Carrillo E, Dutta J. Improved chlorate production with platinum nanoparticles deposited on fluorinated activated carbon cloth electrodes. Clean. Eng. Technol. 2020;1:100016. doi: 10.1016/j.clet.2020.100016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim H-I, et al. Effects of maleic anhydride content on mechanical properties of carbon fibers-reinforced maleic anhydride-grafted-poly-propylene matrix composites. Carbon Lett. 2016;20:39–46. doi: 10.5714/CL.2016.20.039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Devi R, Tapadia K, Maharana T. Casting of carbon cloth enrobed polypyrrole electrode for high electrochemical performances. Heliyon. 2020;6:e03122. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2019.e03122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rahmanian S, Suraya AR, Zahari R, Zainudin ES. Synthesis of vertically aligned carbon nanotubes on carbon fiber. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2013;271:424–428. doi: 10.1016/j.apsusc.2013.01.207. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sing KSW. Reporting physisorption data for gas/solid systems with special reference to the determination of surface area and porosity (Recommendations 1984) Pure Appl. Chem. 1985;57:603. doi: 10.1351/pac198557040603. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thommes M, et al. Physisorption of gases, with special reference to the evaluation of surface area and pore size distribution (IUPAC Technical Report) Pure Appl. Chem. 2015;87:1051–1069. doi: 10.1515/pac-2014-1117. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vautard F, et al. Influence of an oxidation of the carbon fiber surface by boiling nitric acid on the adhesion strength in carbon fiber-acrylate composites cured by electron beam. Surf. Interface Anal. 2013;45:722–741. doi: 10.1002/sia.5147. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gao W, Zhao G. Surface oxidation modification of wooden activated carbon fibers with nitric acid. Mater. Rep. 2018;32:1688–1694. doi: 10.11896/j.issn.1005-023X.2018.10.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pittman CU, He GR, Wu B, Gardner SD. Chemical modification of carbon fiber surfaces by nitric acid oxidation followed by reaction with tetraethylenepentamine. Carbon. 1997;35:317–331. doi: 10.1016/S0008-6223(97)89608-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tang H, et al. Theoretical insight into the adsorption of aromatic compounds on graphene oxide. Environ. Sci. Nano. 2018;5:2357–2367. doi: 10.1039/C8EN00384J. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hasanzadeh M, Soltaninejad Y, Esmaeili S, Babaei AA. Preparation, characterization, and application of modified magnetic biochar for the removal of benzotriazole: Process optimization, isotherm and kinetic studies, and adsorbent regeneration. Water Sci. Technol. 2022;85:3036–3054. doi: 10.2166/wst.2022.092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sarker M, Bhadra BN, Seo PW, Jhung SH. Adsorption of benzotriazole and benzimidazole from water over a Co-based metal azolate framework MAF-5(Co) J. Hazard. Mater. 2017;324:131–138. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2016.10.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zangi R. Attraction between like-charged monovalent ions. J. Chem. Phys. 2012;136:5692. doi: 10.1063/1.4705692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Manning GS. Counterion condensation theory of attraction between like charges in the absence of multivalent counterions. Eur. Phys. J. E. 2011;34:132. doi: 10.1140/epje/i2011-11132-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zheng Y, Lin C, Zhang J-S, Tan Z-J. Ion-mediated interactions between like-charged polyelectrolytes with bending flexibility. Sci. Rep. 2020;10:21586. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-78684-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zangi R. Attraction between like-charged monovalent ions. J. Chem. Phys. 2012;136:184501. doi: 10.1063/1.4705692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tiraferri A, Maroni P, Borkovec M. Adsorption of polyelectrolytes to like-charged substrates induced by multivalent counterions as exemplified by poly(styrene sulfonate) and silica. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2015;17:10348–10352. doi: 10.1039/C5CP00910C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Al-Degs YS, El-Barghouthi MI, El-Sheikh AH, Walker GM. Effect of solution pH, ionic strength, and temperature on adsorption behavior of reactive dyes on activated carbon. Dyes Pigm. 2008;77:16–23. doi: 10.1016/j.dyepig.2007.03.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hu Y, et al. Dye adsorption by resins: Effect of ionic strength on hydrophobic and electrostatic interactions. Chem. Eng. J. 2013;228:392–397. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2013.04.116. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Langergren S, Svenska BK. Zur theorie der sogenannten adsorption geloester stoffe. Veternskapsakad Handlingar. 1898;24:1–39. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Blanchard G, Maunaye M, Martin G. Removal of heavy metals from waters by means of natural zeolites. Water Res. 1984;18:1501–1507. doi: 10.1016/0043-1354(84)90124-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Roginsky S, Zeldovich YB. The catalytic oxidation of carbon monoxide on manganese dioxide. Acta Phys. Chem. U.S.S.R. 1934;1:2019. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shahmirzaee M, Hemmati-Sarapardeh A, Husein MM, Schaffie M, Ranjbar M. ZIF-8/carbon fiber for continuous adsorption of sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) from aqueous solutions: Kinetics and equilibrium studies. J. Water Process Eng. 2021;44:102437. doi: 10.1016/j.jwpe.2021.102437. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sahoo TR, Prelot B. In: Nanomaterials for the Detection and Removal of Wastewater Pollutants. Bonelli B, Freyria FS, Rossetti I, Sethi R, editors. Elsevier; 2020. pp. 161–222. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Liu B, et al. Temperature-induced adsorption and desorption of phosphate on poly (acrylic acid-co-N-[3-(dimethylamino) propyl] acrylamide) hydrogels in aqueous solutions. Desalin. Water Treat. 2019;160:260–267. doi: 10.5004/dwt.2019.24351. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nour HF, et al. Main-chain donor–acceptor polyhydrazone mediated adsorption of an anionic dye from contaminated water. React. Funct. Polym. 2021;158:104795. doi: 10.1016/j.reactfunctpolym.2020.104795. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Giles CH, MacEwan TH, Nakhwa SN, Smith D. 786. Studies in adsorption. Part XI. A system of classification of solution adsorption isotherms, and its use in diagnosis of adsorption mechanisms and in measurement of specific surface areas of solids. J. Chem. Soc. 1960;1:3973–3993. doi: 10.1039/JR9600003973. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Langmuir I. The adsorption of gases on plane surfaces of glass, mica and platinum. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1918;40:1361–1403. doi: 10.1021/ja02242a004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Freundlich HMF. Over the adsorption in solution. J. Phys. Chem. 1906;57:385–470. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dubinin MM, Radushkevich LV. The equation of the characteristic curve of the activated charcoal. Proc. Acad. Sci. U.S.S.R. Phys. Chem. Sect. 1947;55:331–337. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sips R. Combined form of Langmuir and Freundlich equations. J. Chem. Phys. 1948;16:490–495. doi: 10.1063/1.1746922. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nour HF, et al. Adsorption isotherms and kinetic studies for the removal of toxic reactive dyestuffs from contaminated water using a viologen-based covalent polymer. New J. Chem. 2021;45:18983–18993. doi: 10.1039/D1NJ02488D. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tcheka C, et al. Biosorption of cadmium ions from aqueous solution onto alkaline-treated coconut shell powder: Kinetics, isotherm, and thermodynamics studies. Biomass Convers. Biorefin. 2022 doi: 10.1007/s13399-022-03099-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nagarajan L, et al. A facile approach in activated carbon synthesis from wild sugarcane for carbon dioxide capture and recovery: Isotherm and kinetic studies. Biomass Convers. Biorefin. 2022 doi: 10.1007/s13399-022-03080-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Peralta ME, et al. Highly efficient removal of heavy metals from waters by magnetic chitosan-based composite. Adsorption. 2019;25:1337–1347. doi: 10.1007/s10450-019-00096-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rigueto CVT, et al. Tannery wastes-derived gelatin and carbon nanotubes composite beads: Adsorption and reuse studies using tartrazine yellow dye. Matéria. 2022;27:1308. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Trikkaliotis DG, Christoforidis AK, Mitropoulos AC, Kyzas GZ. Adsorption of copper ions onto chitosan/poly(vinyl alcohol) beads functionalized with poly(ethylene glycol) Carbohydr. Polym. 2020;234:115890. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2020.115890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Costa JAS, Sarmento VHV, Romão LPC, Paranhos CM. Adsorption of organic compounds on mesoporous material from rice husk ash (RHA) Biomass Convers. Biorefin. 2020;10:1105–1120. doi: 10.1007/s13399-019-00476-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its Supplementary Information file.