Abstract

When generated in a mass spectrometer bridged bicyclic 1,3-dioxenium ions derived from 4-O-acylgalactopyranosyl, donors can be observed by infrared spectroscopy at cryogenic temperatures, but they are not seen in the solution phase in contrast to the fused bicyclic 1,3-dioxalenium ions of neighboring group participation. The inclusion of a 4-C-methyl group into a 4-O-benzoyl galactopyranosyl donor enables nuclear magnetic resonance observation of the bicyclic ion arising from participation by the distal ester, with the methyl group influence attributed to ester ground state conformation destabilization. We show that a 4-C-methyl group also influences the side-chain conformation, enforcing a gauche,trans conformation in gluco and galactopyranosides. Competition experiments reveal that the 4-C-methyl group has only a minor influence on the rate of reaction of 4-O-benzoyl or 4-O-benzyl-galacto and glucopyranosyl donors and, consequently, that participation by the distal ester does not result in kinetic acceleration (anchimeric assistance). We demonstrate that the stereoselectivity of the 4-O-benzoyl-4-C-methyl galactopyranosyl donor depends on reaction concentration and additive (diphenyl sulfoxide) stoichiometry and hence that participation by the distal ester is a borderline phenomenon in competition with standard glycosylation mechanisms. An analysis of a recent paper affirming participation by a remote pivalate ester is presented with alternative explanations for the observed phenomena.

Introduction

The development of practical, reproducible, and highly stereoselective glycosylation reactions is of critical importance to the glycosciences.1−3 In this respect, the concept of stereodirecting participation from distal esters (distal group participation, DGP) has recently received much attention with particular emphasis on the formation of α-galacto and α-fucopyranosides with DGP by esters at the 4-position.4−9 The DGP concept, a seemingly straightforward extrapolation of the well-established concept of neighboring group participation (NGP) involving the intermediacy of bridged bicyclic ions as intermediates, was introduced as long ago as 1972.10,11 The concept has received support from studies of the influence on selectivity of electron-donating and/or withdrawing groups on the directing ester, with Seeberger, Pagel, and co-workers most recently showing 4-O-pivalate esters to be more α-directing than 4-O-acetates.5,12−14 We, on the other hand, have argued against DGP in the form of bridged bicyclic ions on multiple grounds:4,15 (i) the experimentally demonstrated reduced thermodynamic stability of six- and seven-membered cyclic 1,3-dioxcarbenium ions compared to their five-membered counterparts,16−18 (ii) the established negative correlation of ring size with ring closure in simple non-carbohydrate models of 1,3-dioxacarbenium ion formation,19 (iii) the unstable ester conformation4,20−22 required for DGP, (iv) the failure of a variety of probes to trap the intermediate ions under typical glycosylation conditions,23,24 (v) the absence of spectroscopic evidence in the condensed phase for bridged bicyclic 1,3-dioxacarbenium ions as compared to fused bicyclic 1,3-dioxalenium ions, (vi) the failure of most models to take into account the stabilization of glycosyl oxocarbenium ions in the form of covalent intermediates by combination with counterions in the solution, (vii) the concatenation of unfavorable steps required, which renders the process kinetically unfavorable (summarized in Scheme 1), and (viii) the availability of other typically overlooked explanations for the experimental phenomena.

Scheme 1. Unfavorable Equilibria in the Formation of the Bridged Dioxacarbenium Ions Required for DGP from 4-O-Acylgalactopyranosyl Donors.

Previously, focusing on the barrier to DGP imposed by the unfavorable ester conformation required, we prepared a series of galactopyranosyl donors 1–6 from the corresponding alcohols 7 and 8 (Figure 1) and studied their reactions and decomposition products.25 Notably, activation of the 4-methyl-4-O-Boc derivative 1 with diphenyl sulfoxide and trifluoromethanesulfonic anhydride in dichloromethane at −80 °C followed by warming to room temperature gave a 56% yield of the bridged bicyclic carbonate 9, indicative of tert-butyl group loss from the corresponding bicyclic ion 10. In contrast, donor 2, lacking the 4-C-methyl group, gave a complex reaction mixture in which no bridged bicyclic carbonate could be located and from which the only isolated product was the intramolecular Friedel–Crafts compound 11. Activation of the 4-C-methyl-4-O-(13C1-benzoate) donor 5 with triflic anhydride in deuteriodichloromethane at −80 °C gave nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectra interpreted as predominantly composed of the bridged bicyclic dioxacarbenium ion 12, thereby providing the first direct spectroscopic evidence for DGP in solution. Gradual warming of the NMR probe revealed ion 12 to be stable up to −40 °C above which decomposition to the 1,6-anhydro derivative 13, isolated in 41% yield, was observed. Analogous to the results with the 4-O-Boc derivatives, repetition of the experiment with the desmethyl analogue 6 did not provide any evidence for the corresponding bridged bicyclic ion but rather revealed the formation of the galactosyl triflate 14 on activation at −80 °C with decomposition to 15 and 16, isolated in 27 and 29% yield, on warming above −20 °C.25 Thus, we found no evidence for DGP by esters of secondary alcohols at the 4-position of typical galactopyranosyl donors but demonstrated that the formation of bridged intermediates is possible from esters of tertiary alcohols at the same position. We interpret the change in behavior on going from secondary to tertiary esters as a consequence of increased conformational mobility in the tertiary systems and so in terms of removal of one of the unfavorable equilibria (K3) depicted in Scheme 1 thereby facilitating cyclization in manner akin to the well-known “gem-dimethyl” effect on cyclization reactions in general.26

Figure 1.

Donors 1–6, alcohols 7 and 8, the bridged ions 10 and 12, galactosyl triflate 14, and the decomposition products 9, 11, 13, 15, and 16.

We now turn our attention to other possible roles played by the methyl group in donors such as 1 and 5 beyond the facilitation of cyclization to bridged intermediates. Jensen and Bols demonstrated previously that 4-C-methylation of methyl α-D-galacto-and glucopyranoside leads to a minor reduction in the rate of acid-catalyzed hydrolysis compared to the parent glycosides, and presciently suggested that this may be due to a change in the conformation of the C5–C6 bond (side-chain conformation) imposed by the presence of the methyl group.27 Indeed, such a change in side-chain conformation is apparent from the observed variations in the 1H NMR coupling constants between H5 and the two diastereotopic H6’s in 1–8, and it is now well-established that side-chain conformation modulates the reactivity and selectivity of glycosyl donors.15,28,29 In donor 5, with the demonstrated propensity to form a bridged intermediate, there arises the further possibility of enhanced reaction rate through anchimeric assistance. To more fully understand the reactivity of galacto- and glucopyranosyl donors substituted with esters at the 4-position, and the manner in which it is influenced by 4-C-methylation, we have studied and report on the manner in which 4-C-methylation influences side-chain conformation in galacto- and glucopyranosides and, through the aegis of competition reactions, describe the effect of 4-C-methylation on glycosylation reaction rate. We also report on the role of concentration and stoichiometry in DGP discovered in the course of our experiments. Finally, we address the work of Seeberger, Pagel, and co-workers on the superiority of pivalate esters in DGP5 and argue against the use of gas phase experiments in the absence of counterions as predictors of solution phase reactivity in glycosylation reactions.

Results and Discussion

Influence of 4-C-Methylation on Side Chain Conformation

The side-chain conformation of carbohydrates is usually considered in terms of an equilibrium mixture of three staggered conformers dubbed the gauche,gauche (gg), gauche,trans (gt), and trans,gauche (tg) conformers (Figure 2), wherein the first descriptor refers to the relationship of the C5–O5 and C6–O6 bonds and the second one to that of the C5–C4 and C6–O6 bonds.30−32

Figure 2.

Staggered conformations of hexose side chains and their relationship to axial (ax) and equatorial (eq) substituents at C4.

Analysis of the relative populations of the gg, gt, and tg conformers in the side chain of a given compound requires unambiguous assignment of the diastereotopic H6pro-R (H6R) and H6pro-S (H6S) protons, which is best achieved by stereospecific monodeuteriation.33−38 Thus, tri-O-acetyl-6S-deuterio-1,6-anhydro-d-glucose 17-D1(38) was converted in 22% overall yield to methyl 2,3-di-O-benzyl-4,6-O-benzylidene-6S-deuterio-α-D-glucopyranoside 18-D1 by standard means. Reductive cleavage of the benzylidene acetal39 with triethylsilane and TFA40 then gave 43% of 19-D1 that was subjected to Parekh–Doering oxidation followed by treatment with methylmagnesium chloride resulting in a 1:0.8 mixture of the 4-C-methyl galacto- and gluco-derivatives 20-D1 and 21-D1 in 84% overall yield. Routine hydrogenolysis then afforded 22-D1 and 23-D1 in 92 and 85% isolated yield, respectively (Scheme 2). Unlabeled 22 and 23 were prepared analogously from unlabeled 19(41,42) via 20 and 21 (Scheme 2).

Scheme 2. Synthesis of 19–23 and Their 6S-Deuterio Isotopomers.

1H NMR spectra for compounds 22, 23, and their monodeuterio analogues were recorded at 500 in MHz in D2O and those of the partially benzylated derivatives 19, 20, and 22 in either CDCl3 or C6D6 for reasons of resolution, with assignments of the diastereotopic side-chain resonances made with the aid of the isotopomers, leading to the data presented in Table 1. Protected galacto- and glucopyranosides retain the same conformations of their respective side chains in CDCl3 and C6D6.38,43 The data for methyl α-D-galactopyranoside 24 and methyl α-D-glucopyranoside 25 (Table 1) are taken from the literature,35 while those for methyl 2,3,6-tri-O-benzyl-α-D-galactopyranoside 26(44) and methyl 2,3,6-tri-O-benzyl-α-D-glucopyranoside 19(45) (Figure 3) are taken from the literature with assignment of the proR and proS side chain hydrogens made by analogy with the corresponding rigorously assigned phenyl β-thioglycosides.38 With all assignments made and coupling constants determined, a standard population analysis was conducted,46−48 whereby eqs 1–3 were solved for the mole fractions of the three staggered conformations (fgg-tg) for all compounds by inputting the experimental coupling constants (3J5,6R and 3J5,6S) and the limiting coupling constants (3JR,gg-tg and 3JS,gg-tg) for each of the three staggered conformers determined with conformationally locked standards.43 In this analysis, negative populations of any given conformer are considered to arise from imperfections in the limiting coupling constants applied and the errors in the measurement of the experimental coupling constants (∼0.4 Hz) and are considered negligible if ≤−5%:43

| 1 |

| 2 |

| 3 |

Table 1. Diagnostic Chemical Shifts, Coupling Constants, and Derived Side-Chain Conformations.

| compound | solvent | configuration | C4 substitution | other protection | δH5 | δH6R, H6S | 3J5,6R, 3J5,6S | side-chain

conformation |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| gg | gt | tg | ||||||||

| 22 | D2O | galacto | Me, OH | 3.64 | 3.62, 3.84 | 8.7, 2.2 | 24.8 | 78.1 | –2.9 | |

| 24 | D2O | galacto | H, OH | 3.92 | 3.70, 3.70 | 7.8, 6.0 | 3.7 | 50.7 | 45.6 | |

| 23 | D2O | gluco | Me, OH | 3.66 | 3.57, 3.88 | 9.2, 2.1 | 20.7 | 83.6 | –4.3 | |

| 25 | D2O | gluco | H, OH | 3.69 | 3.76, 3.89 | 5.4, 2.3 | 56.0 | 44.0 | 0.0 | |

| 20 | C6D6 | galacto | Me, OH | 2,3,6-tri-O-Bn | 3.92 | 3.88, 3.95 | 5.9, 2.6 | 49.0 | 47.8 | 3.2 |

| 26 | CDCl3 | galacto | H, OH | 2,3,6-tri-O-Bn | 3.90 | 3.68, 3.74 | 5.8, 5.7 | 25.6 | 31.8 | 42.6 |

| 21 | CDCl3 | gluco | Me, OH | 2,3,6-tri-O-Bn | 3.90 | 3.58, 3.72 | 7.0, 5.1 | 18.6 | 46.9 | 34.5 |

| 19 | CDCl3 | gluco | H, OH | 2,3,6-tri-O-Bn | nda | nda | 5.3, 4.1 | 43.1 | 34.5 | 22.4 |

| 7 | CDCl3 | galacto | Me, OH | 2,3,6-tri-O-Bn | 3.44 | 3.93, 3.82 | 5.5, 2.9 | 50.5 | 42.3 | 7.2 |

| 8 | CDCl3 | galacto | H, OH | 2,3,6-tri-O-Bn | 3.57 | 3.81, 3.76 | 5.7, 5.7 | 26.6 | 30.8 | 42.6 |

| 3 | CDCl3 | galacto | Me, OBz | 2,3,6-tri-O-Bn | 3.76 | 4.26, 3.89 | 7.5, 2.5 | 34.2 | 64.5 | 1.3 |

| 4 | CDCl3 | galacto | H, OBz | 2,3,6-tri-O-Bn | 3.87 | 3.69, 3.58 | 6.9, 5.9 | 13.3 | 42.0 | 44.7 |

| 29 | CDCl3 | galacto | Me, OBn | 2,3,6-tri-O-Bn | 3.53 | 3.79, 3.94 | 6.2, 3.6 | 38.2 | 46.0 | 15.8 |

| 28 | C6D6 | gluco | Me, OBz | 2,3,6-tri-O-Bn | nda | nda | 6.0, 2.9 | 45.7 | 47.3 | 7.0 |

| 30 | CDCl3 | gluco | Me, OBn | 2,3,6-tri-O-Bn | 3.74 | 3.66, 3.94 | 7.6, 2.1 | 36.3 | 67.4 | –3.7 |

Not determined due to insufficient resolution.

Figure 3.

Literature compounds 24, 25, and 26.

The installation of a methyl group at the 4-position of methyl α-D-galactopyranoside 24 gives compound 22 in which 3JH5,6R is reduced by ∼1 Hz on incorporation of the methyl group, while 3JH5,6S decreases from 6.0 to 2.2 Hz indicative of a significant change of the mean side-chain conformation on methylation. As is apparent from inspection of the population analysis of the three staggered conformers, this change involves depopulation of the tg conformation with correspondingly increased populations of the gg and gt conformers to the extent that the gt conformer dominates following C-methylation. Turning to methyl 2,3,6-tri-O-benzyl-α-D-galactopyranoside 26 and its 4-C-methyl derivative 20, the inclusion of the methyl group again destabilizes and depopulates the tg conformer leading to correspondingly increased populations of the gg and gt conformers. In both 20 and 26, the gg and gt conformations are approximately equally populated, which we attribute to an intramolecular hydrogen bond stabilizing the otherwise relatively disfavored gg conformation in the aprotic solvent.38 In the gluco-series, the inclusion of a 4-C-methyl group results in a reduction in population of the gg conformation and correspondingly increased populations of the gt and tg conformation, whether in D2O solution for the unprotected 23 and 25 or in CDCl3 solution for the 2,3,6-tri-O-benzylated compounds 19 and 21. In the absence of protection at the 2, 3, and 6 positions in D2O the gt conformation is greatly favored (84%) in the 4-C-methyl gluco compound 23 just as it is in the unprotected galacto isomer 22. With all but the 4-hydroxy group protected and in aprotic solution, the addition of the 4-C-methyl group in the gluco series results in an approximately 3:2:1 mix of the gt, tg, and gg conformers with the abnormally high population of the tg conformer in this case being due to the presence of an intramolecular hydrogen bond, consistent with previous results.38 Overall, it is apparent that a 4-C-methyl group in the galacto series (Figure 2, ax = OH, eq = Me) destabilizes the tg conformation because of a syn-pentane-type, or 1,3-interaction, with O6. In the gluco series, the addition of the methyl group (Figure 2, ax = Me, eq = OH) results in an analogous destabilization of the gg conformation. In the absence of intramolecular hydrogen bonding, the presence of the 4-C-methyl group gives rise to side-chain populations in both the galacto and gluco series that both co-incidentally strongly favor the gt conformation.

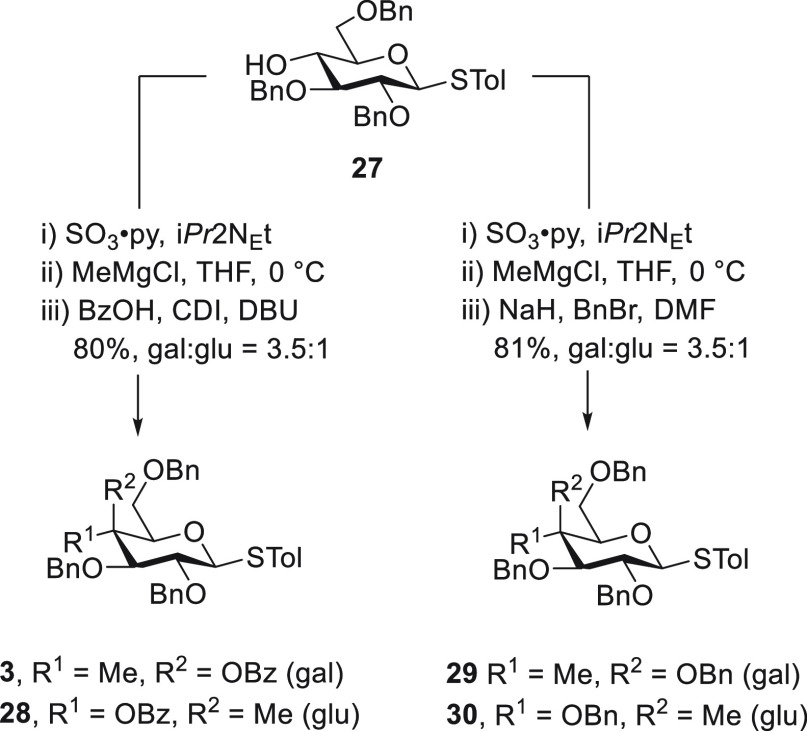

We next turned to the influence of protecting groups, benzoate esters or benzyl ethers, at the 4-position in conjunction with that of 4-C-methylation on side-chain conformation. To this end, we employed the p-tolyl β-D-thioglycospyranosides, with all compounds either obtained as described previously25 or as set out in Scheme 3 starting from p-tolyl 2,3,6-tri-O-benzyl-β-D-glucothiopyranoside 27.45 Vázquez and coworkers have established that neither anomeric configuration nor the nature of the aglycon greatly influences glycoside side-chain conformation.49−52 Therefore, in this series of compounds, we simply assigned the proR and proS hydrogen resonances on the basis of their relative chemical shifts by analogy30 with the methyl α-pyranosides described above and with closely related and rigorously assigned phenyl β-D-thioglycopyranosides described previously.38

Scheme 3. Synthesis of 3 and 28–30.

Comparison of the side-chain conformations of galactosyl thioglycosides 3 and 4 reveals that the inclusion of a 4-C-methyl group has a similar effect on the 4-O-benzoate esters as on the corresponding alcohols (20 and 26) to the extent that it strongly disfavors the tg conformation. However, in the absence of intramolecular hydrogen bonding stabilizing the gg conformation, the result is an approximately 1:2 mixture of the gg and gt conformers that approaches the population distribution seen for the tetraol 22 in D2O solution. The corresponding 4-O-benzyl ether 29 populates the gg conformer to a similar extent as the 4-O-benzoate 3 but has a somewhat enhanced population (15.8%) of the tg conformer that is achieved at the expense of a reduction in population of the gt conformer. In the glucosyl series, 4-O-benzoate 28 populates an approximately 1:1 mixture of the gg and gt conformers with only a minor contribution from the tg conformer. The corresponding 4-O-benzyl ether 30 is an approximately 1:2 mixture of the gg and gt conformations with no contribution from the tg conformation.

Influence of 4-C-Methylation on Glycosylation

To investigate the influence of 4-C-methylation on glycosylation, both with and without possible anchimeric assistance from a benzoate ester at the 4-position, we designed a series of competition experiments in which equimolar mixtures of two glycosyl donors compete for a deficiency of glycosyl acceptor under similar conditions to those used in our investigation into the effect of methylation on DGP, namely, with activation by the diphenyl sulfoxide/triflic anhydride combination53 in dichloromethane at −78 °C. We used 1,2;3,4-di-O-isopropylidene galactopyranose 31 as acceptor, and buffered the reactions with 2,4,6-tri-tert-butylpyrimidine (TTBP). Because of the anticipated complexity of the competition reaction mixtures, we first conducted each of the individual glycosylation reactions and isolated and characterized the major products for use as authentic standards (Table 2).

Table 2. Influence of 4-C-Methylation on Glycosylation of 1,2;3,4-di-O-Isopropylidene Galactopyranose (31).

Comparison of Table 2 entries 1 and 3 reveals the influence of the 4-O-protecting group on selectivity, with the benzyl ether 29 showing essentially no selectivity and the benzoate ester 3 displaying complete α-selectivity. Comparison of entries 3 and 5 in Table 2 confirms the influence of the 4-C-methyl group in the benzoate series on selectivity with the desmethyl donor 4 showing only minimal selectivity for the α-glycoside in contrast with the complete α-selectivity seen with 31 in the presence of the methyl group. Comparison of entries 1 and 2 in Table 2 reveals the relatively minor effect of configuration at C4 on selectivity in the 4-C-methyl 4-O-benzyl series with both the galacto 29 and gluco 30 donors affording the coupled products with minimal selectivity. In comparing 29 with 30, however, it is noteworthy that the major byproduct from the gluco donor 30 (Table 2, entry 2) was the 1,6-anhydro derivative 35, whereas the major byproduct from the galacto donor 29 (Table 2, entry 1) was the more unusual 1,4-anhydro derivative 33.54 Finally, comparison of the two 4-C-methyl-4-O-benzoyl donors 3 and 28 (Table 2, entries 3 and 4) reveals the far greater influence of configuration for donors carrying an ester at the 4-position than those with a 4-O-benzyl ether, as 3 and 28 both display complete but opposite selectivity. In addition, isolated from the reaction of 28 were the minor byproduct 38, a 1,6-anhydro derivative, which is comparable to derivative 35 obtained in minor amounts from the reaction of the benzyl ether 30, the hemiacetal 39, and the triflated acceptor 40.

The high β-selectivity observed in the formation of 37 from the gluco-donor 28 (Table 2, entry 4) could be interpreted in terms of DGP by the benzoate group through an intermediate bridged ion 42, or simply by SN2 displacement of the covalent donor 43 (Scheme 4). In the case the selectivity arises through SN2-like displacement from the covalent donor 43, the difference in selectivity between the 4-O-benzoyl and 4-O-benzyl donors 28 and 30, respectively (Table 2, entries 4 and 2), would be due to the stronger electron-withdrawing ability of the benzoate ester and the consequent stabilization of the covalent donor.55,56 DGP from esters at the 4-position of mannosyl donors via bridged ions related to 42 has been advocated in the literature,57 but in previous work we have failed to find any evidence in support of it.23

Scheme 4. Possible Reaction Pathways for the Formation of β-Glucoside 37 from Donor 28.

To probe the possibility of DGP with donor 28, we synthesized the isotopomer 99% enriched in 13C at the carbonyl C of the benzoate ester 44 (Supporting Information) and oxidized 44 to the glycosyl sulfoxide 45 (Figure 4) for ease of activation at −80 °C (Supporting Information). Sulfoxide 45 was activated at −80 °C in CD2Cl2 solution in the presence of TTBP by the addition of Tf2O, and the 1H and 13C spectra were quickly recorded. The reaction mixture was then allowed to warm in 10 °C increments in the probe of the NMR spectrometer with spectra recorded at every stage (Supporting Information). Complete activation was observed at −80 °C and gave rise to relatively complex spectra containing several apparent activated species and resonances attributed to benzyl triflate 4658 along with minor amounts of 13C enriched 1,6-anhydro sugar 47 (Figure 4).58 On warming, the proportions of 46 and 47 in the reaction mixture gradually increased until −20 to −10 °C when the signal attributed to 46 was lost. Workup of the reaction mixture after it reached room temperature allowed isolation of the 13C enriched 1,6-anhydro sugar 47 in 31% yield. Most importantly, and in stark contrast to the galactopyranosyl series and the ready observation of ion 12,25 at no stage of this NMR experiment was any evidence observed for the formation of a bridged bicyclic ion 42. We conclude that DGP through a cyclic ion such as 42 is highly unlikely for donors with equatorial esters at the 4-position and consequently that the high β-selectivity in the coupling of donor 28 with diisopropylidenegalactopyranose 31 (Table 2, entry 4) is the result of stabilization of an activated covalent intermediate 43 by the electron-withdrawing effect of the remote ester, with subsequent SN2-like displacement.

Figure 4.

Structures of isotopically enriched donors 44 and 45, benzyl triflate 46, and of 1,6-anhydro sugar 47.

Turning to the competition experiments, equimolar mixtures of two donors and acceptor 31 were activated in dichloromethane at −78 °C in the presence of TTBP: After stirring at −78 °C for 20 h, the reaction mixtures were quenched and analyzed by reverse phase-HPLC with detection by ultraviolet and electrospray ionization (ESI)-mass spectrometry. In view of the complexity of the reaction mixtures, no attempt was made to isolate or characterize the saccharides or the various byproducts formed, whose presence was nevertheless confirmed by mass spectrometry, but attention was focused on the relative proportions of the unreacted donors, leading overall to the results set out in Table 3.

Table 3. Competition Reactions.

Identified by ESI mass spectrometry in the reaction mixture.

The competition reaction between the two benzylated 4-C-methyl donors 29 and 30 (Table 3, entry 1), or between the two benzoylated donors 3 and 28 (Table 3, entry 2), shows that in a given pair of isomers the galacto-isomer is moderately more reactive than its gluco-counterpart, such that the inclusion of the methyl group does not alter the very well-established relative anomeric reactivity patterns of galacto and gluco isomers.59−61 The very similar ratios of recovered donors in Table 3, entries 1 and 2 also rule out the possibility of any significant anchimeric assistance by the 4-O-benzoate ester in donor 3 in spite of its predisposition toward participation demonstrated by the formation of the bridged ion 12 in NMR experiments conducted in the absence of acceptor alcohol. This absence of anchimeric assistance by the remote ester is consistent with multiple investigations into the possibility of kinetic acceleration of NGP by esters at the 2-position of 1,2-cis-glycosyl donors.4 Likewise, anchimeric assistance in the subsequent reaction of an activated 1,2-trans species, such as an α-glycosyl triflate or glycosyl oxysulfonium ion, can be excluded on the basis of these results. The third competition reaction, between the 4-O-benzyl and 4-O-benzoyl 4-C-methyl galactopyranosyl donors, 29 and 3, respectively, demonstrates that the ether-protected system 29 is moderately more reactive than its esterified congener 3 (Table 3, entry 3). Thus, the presence of the 4-C-methyl group and the associated change in conformation of the ester in 3 and the side-chain conformation in both 3 and 29, with respect to the desmethyl analogues, does not perturb the classical reactivity sequence according to which esters are more disarming than ethers in glycosylation reactions.56

Influence of Concentration and Stoichiometry on Glycosylation Selectivity

Perhaps the most striking result in Table 2 is the fully α-selective coupling of the 4-C-methyl-4-O-benzoyl galactopyranosyl donor 3 with diacetone galactopyranose 31 (Table 2, entry 3), which stands in contrast to the 1.3:1 α/β ratio we reported previously under similar conditions.25 We traced this apparent discrepancy with our earlier work to the differences in concentration and stoichiometry between the previous experiment25 and the one reported in Table 2. Thus, the original experiments25 were conducted with a 0.1 M solution of donor 3 and 80 mole % of acceptor 31, whereas the experiments reported in Table 2 used a 0.05 M solution of 3 and a full equivalent of acceptor. In addition, the earlier experiment also employed 200 mole percent of diphenyl sulfoxide and 150 mole % of triflic anhydride, whereas the experiments reported in Table 2 used 100 mole % of diphenyl sulfoxide and 100 mole % of triflic anhydride. In each case, sufficient base (TTBP) was present to buffer the triflic acid formed in the course of the reaction. All of the changes from the published work were instituted in preparation for the competition experiments reported in Table 3, which require that the reactions not go to more than approximately 50% overall completion. To determine whether the change in selectivity resulted from the change in concentration or the change in diphenyl sulfoxide stoichiometry, we first repeated the coupling of 3 with diacetone galactopyranose 31 under the previous conditions, obtaining essentially the same results, and then conducted two further couplings independently varying overall concentration and diphenyl sulfoxide stoichiometry leading to the results presented in Table 4.

Table 4. Influence of Concentration and Diphenyl Sulfoxide Equivalence on the Coupling of Donor 3 with Diacetone Galactopyranose 31.

From the data presented in Table 4, it is evident that both the overall reaction concentration and the presence of excess diphenyl sulfoxide in the reaction mixture impact the selectivity of coupling of donor 3 to diacetone galactopyranose 31. Thus, from a comparison of Table 4, entries 1 and 4, it is clear that at the lower concentration of 0.05 M donor and acceptor, the presence of excess diphenyl sulfoxide reduces the α/β-selectivity significantly. At the higher concentration of both donor and acceptor, the α/β ratio is reduced further again (Table 4, entries 2 and 3), but it is the reaction containing free diphenyl sulfoxide that is marginally more α-selective. We interpret these results as demonstrating the borderline nature of DGP by the benzoate ester in 3, having previously drawn attention to what we consider to be the borderline nature of even NGP mechanisms in glycosylation.15 These observations can be understood in terms of the equilibrium between the bridged ion 12 resulting from DGP, ultimately leading to the α-product, and a more typical covalent donor, either a glycosyl sulfoxide or a glycosyl oxysulfonium ion 48 that is the precursor of the β-product (Scheme 5). Both glycosyl triflates62 and glycosyl oxysulfonium ions63 have been characterized multiple times,64 with the oxysulfonium ions being considered to be the more stable of the two.63

Scheme 5. Concentration and Additive-Dependent Nature of DGP Following Activation of Donor 3.

Influence of a 4-O-Pivalate Ester on Galactopyranosylation

Finally, we address the origin of the stereodirecting influence of pivalate esters at the 4- and 6-positions of galactosyl donors described recently by Seeberger, Pagel, and co-workers.5 Briefly, the authors of this paper reported that the 4-O-pivalate protected donor 49 gave excellent α-selectivity in glycosylation reactions conducted with activation by N-iodosuccinimide and triflic acid in dichloromethane at −20 °C and that this selectivity was superior to that seen with the corresponding 6-O-pivalate 50, the 4,6-di-O-pivalate 51, the 4-O-acetate 52, and the 4-O-trifluoroacetate 53 (Figure 5). On the basis of cryogenic gas phase infrared measurements on isolated ions generated in a mass spectrometer with support by density functional theory investigations also carried out in the absence of solvent and counterion, the authors concluded that the optimal α-selectivity seen with 49 was the result of DGP via a bridged ion 54. They further concluded that 54 was more stabilized with respect to the corresponding simple oxocarbenium ion than the corresponding bridged ion 55 arising from the 4-O-acetate because of the greater electron-donating ability of the tert-butyl group in 54. No evidence for DGP was found with the trifluoroacetate 53 although it gave reasonable α-selectivity under the glycosylation conditions employed, certainly better than that seen with the acetate 52. Alternative explanations for the increased α-directing effect of electron-rich esters at the 4-position of galactosyl donors4,15 were not considered.

Figure 5.

Donors and intermediates considered by Seeberger, Pagel, and co-workers.

We have previously shown that the presence of a either 4-O- or a 6-O-pivalate ester does not change the mix of gg, gt, and tg side-chain conformers of galactopyranosyl donors carrying benzyl ethers on the remaining hydroxyl groups with respect to the corresponding acetates.38 The presence of a 4-O-trifluoroacetate ester, however, has a significant influence in that the population of the tg conformer increases to 75% from the 55% seen in both the 4-O-pivalate and acetate esters, with corresponding reductions in the populations of the gg and gt conformers. The strongly electron-withdrawing effect of the 4-O-trifluoroacetate ester is therefore reinforced by the change in side-chain conformation it confers, which logically leads to stabilization of covalent intermediates such as the β-galactosyl triflate and the strong α-selectivity seen by Seeberger, Pagel, and co-workers with donor 53. As we had not previously investigated the combined influence of pivalate groups at the 4- and 6-positions on the side-chain conformation of a galactopyranosyl donor, we prepared donor 51 by standard means from the corresponding diol.5 The 3JH5,H6a and 3JH5,H6b coupling constants of 51 that report on its side-chain conformation were found to be 7.3 and 6.0 Hz, respectively, and fully consistent with those of the corresponding 2,3,6-tri-O-benzyl-4-O-pivaloyl and 2,3,4-tri-O-benzyl-6-O-pivaloyl donors,38 and we conclude that there is no interaction between the 4- and 6-O-pivalate esters in 51.

As we have shown with donor 6, in the solution phase there is no evidence for the formation of a cyclic dioxocarbenium ion bridging the 1- and 6-positions, rather the anticipated covalent glycosyl triflate is observed:25 This observation is bolstered by multiple failed experiments designed to trap such an intermediate.23,25 A bridged ion such as 12 only becomes observable in the solution phase once the ground state ester conformation is destabilized by the presence of a well-placed substituent, when trapping experiments for related ions are also successful.25 Boons and coworkers previously found the pivalate 49 to give an α/β-selectivity of 16:1 on activation with N-iodosuccinimide and trimethylsilyl triflate in 1:1 toluene/dioxane, whereas the corresponding 4-O-benzoate gave a selectivity of 17:1 suggesting that the pivalate ester is at best marginally more advantageous than a benzoate ester.12 There is no reason to believe that the ground state conformation of a pivalate ester is any different from that of acetate or benzoate esters and consequently no reason to believe that pivalate esters have any special propensity toward DGP. We conclude that the experimental observations of Seeberger, Pagel, and co-workers on the very high α-selectivity seen with donor 49, while certainly significant from a preparative standpoint, likely do not arise from DGP in the form of the bridged ion 54. We stress that experiments demonstrating the formation of such bridged ions in the absence of the counterion either in the gas phase or in silico have little or no relevance to the solution phase, where the correct reference point is the covalent donor and not a naked oxocarbenium ion.4,15 We propose, consistent with our previous suggestions on the influence of electron density in the modulation of selectivity by 4-O-carboxylate esters in galactopyranosylation,4,15 that the advantageous effect of the pivalate ester as compared to the corresponding acetate can be attributed to the increased electron density on O4 of the galactosyl donor, as a result of electron donation by the tert-butyl group, and the consequent increased electrostatic stabilization of (partial) positive charge at the anomeric locus and a consequent shift of the general reaction mechanism toward looser and more α-selective ion pairs. This hypothesis is best appreciated by consideration of the minor ester no-bond resonance form in Figure 6, is consistent with the increased stability of the pivaloyl cation over the acetyl cation,65,66 and models for the enhanced reactivity of galactopyranosyl over glucopyranosyl systems that invoke stabilization of positive charge at the anomeric center by electrostatic interaction with the electron density at O4 in galactose and related systems.67−70

Figure 6.

Non-DGP model for α-directing influence of electron-rich esters at galactose O4.

Conclusions

Installation of a single methyl group at C4 of galacto- and glucopyranosyl donors changes the relative populations of the three staggered conformers of the side chain by destabilizing the tg conformation in the galacto- series and of the gg conformation in the glucopyranosyl series. This leads to the preferential adoption of the gt conformation in both 4-C-methyl galacto- and glucopyranosyl donors. Competition experiments between galacto- and glucopyranosyl donors bearing a 4-C-methyl group reveal the galacto isomer to be moderately more reactive than their gluco counterparts and that ether-protected 4-C-methyl donors are more reactive than ester-protected ones consistent with conventional reactivity patterns. No evidence was found in support of anchimeric assistance by a 4-O-benzoate ester even in the presence of a 4-C-methyl group. Overall, we conclude that the presence of a 4-C-methyl group does not significantly impact the reactivity of a galacto or a glucopyranosyl donor carrying either a benzyl ether or a benzoate ester at the 4-position. The stereochemical outcome of 4-O-benzoyl-4-C-methyl galactopyranosylation is dependent on both concentration and stoichiometry of the reagent leading to the conclusion that, even in this most favorable of cases, DGP at best is a borderline phenomenon.

Acknowledgments

We thank the NIH (GM62160) for financial support of this project, Kapil Upadhyaya (UGA) for preliminary observations on the influence of 4-C-methylation on donor reactivity and Michael G Pirrone (UGA) and Constance M Sullivan (UGA) for assistance with the preparation of 17-D1.

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this study are available in the published article and its Supporting Information.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.joc.3c01496.

Full experimental details and copies of NMR spectra (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Walt D. R.; Aoki-Kinoshita K. F.; Bendiak B.; Bertozzi C. R.; Boons G.-J.; Darvill A.; Hart G. W.; Kiessling L. L.; Lowe J.; Moon R.; Paulson J. C.; Sasisekharan R.; Varki A. P.; Wong C.-H.. Transforming Glycoscience: A Roadmap for the Future; National Research Council: Washington DC, 2012. 10.17226/13446. [Google Scholar]

- Pohl N. L. Carbohydrate Chemistry. Chem. Rev. 2018, 118, 7865–7866. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.8b00512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeanneret R. A.; Johnson S. E.; Galan M. C. Conformationally Constrained Glycosyl Donors as Tools to Control Glycosylation Outcomes. J. Org. Chem. 2020, 85, 15801–15826. 10.1021/acs.joc.0c02045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hettikankanamalage A.; Lassfolk R.; Ekholm F.; Leino R.; Crich D. Mechanisms of Stereodirecting Participation and Ester Migration from Near and Far in Glycosylation and Related Reactions. Chem. Rev. 2020, 120, 7104–7151. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.0c00243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greis K.; Leuichnitz S.; Kirschbaum C.; Chang C.-W.; Lin M.-H.; Meijer G.; von Helden G.; Seeberger P. H.; Pagel K. The Influence of the Electron Density in Acyl Protecting Groups on the Selectivity of Galactose Formation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 20258–20266. 10.1021/jacs.2c05859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komarova B. S.; Ustyuzhanina N. E.; Tsvetkov Y. E.; Nifantiev N. E.. Stereocontrol of 1,2-cis-Glycosylation by Remote O-Acyl Protecting Groups. In Modern Synthetic Methods in Carbohydrate Chemistry; From Monosaccharides to Complex Glycoconjugates, Werz D. B., Vidal S. Eds.; Wiley, 2013; pp 125–160. [Google Scholar]

- Komarova B. S.; Tsvetkov Y. E.; Nifantiev N. E. Design of α-Selective Glycopyranosyl Donors Relying on Remote Anchimeric Assistance. Chem. Rec. 2016, 16, 488–506. 10.1002/tcr.201500245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Y.; Jiang Q.; Wang X.; Xiao G. Total Synthesis of Cordyceps militaris Glycans via Stereoselective Orthogonal One-Pot Glycosylation and α-Glycosylation Strategies. Org. Lett. 2022, 24, 7950–7954. 10.1021/acs.orglett.2c03081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ter Braak F.; Elferink H.; Houthuijs K. J.; Oomens J.; Martens J.; Boltje T. J. Characterization of Elusive Reaction Intermediates Using Infrared Ion Spectroscopy: Application to the Experimental Characterization of Glycosyl Cations. Acc. Chem. Res. 2022, 55, 1669–1679. 10.1021/acs.accounts.2c00040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dejter-Juszynski M.; Flowers H. M. Studies on the Koenigs-Knorr Reaction: Part III. A Stereoselective Synthesis of 2-Acetamido-2-deoxy-6-O-α-L-fucopyranosyl-D-glucose. Carbohydr. Res. 1972, 23, 41–45. 10.1016/S0008-6215(00)81575-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dejter-Juszynski M.; Flowers H. M. Studies on the Koenigs-Knorr Reaction: Part IV: The Effect of Participating Groups on the Stereochemistry of Disaccharide Formation. Carbohydr. Res. 1973, 28, 61–74. 10.1016/S0008-6215(00)82857-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Demchenko A. V.; Rousson E.; Boons G.-J. Stereoselective 1,2-cis-Galactosylation Assisted by Remote Neighboring Group Participation and Solvent Effects. Tetrahedron Lett. 1999, 40, 6523–6526. 10.1016/S0040-4039(99)01203-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gerbst A. G.; Ustuzhanina N. E.; Grachev A. A.; Tsvetkov D. E.; Khatuntseva E. A.; Nifant’ev N. E. Effect of the Nature of Protecting Group at O-4 on Stereoselectivity of Glycosylation by 4-O-Substituted 2,3-Di-O-benzylfucosyl Bromides. Mendeleev Commun. 1999, 9, 114–116. 10.1070/MC1999v009n03ABEH001073. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gerbst A. G.; Ustuzhanina N. E.; Grachev A. A.; Khatuntseva E. A.; Tsvetkov D. E.; Whitfield D. M.; Berces A.; Nifantiev N. E. Synthesis, NMR, and Conformational Studies of Fucoidan Fragments. III. Effect of Benzoyl Group at O-3 on Stereoselectivity of Glycosylation by 3-O- and 3,4-Di-O-benzoylated 2-O-Benzylfucosyl Bromides. J. Carbohydr. Chem. 2001, 20, 821–831. 10.1081/CAR-100108659. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crich D. En Route to the Transformation of Glycoscience: A Chemist’s Perspective on Internal and External Crossroads in Glycochemistry. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 17–34. 10.1021/jacs.0c11106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulsen H. Transformations of Carboxonium Compounds in Carbohydrate and Polyol Chemistry. Pure Appl. Chem. 1975, 41, 69–92. 10.1351/pac197541010069. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Paulsen H.; Meyborg H.; Behre H. Cyclorearrangement of Di-O-pivaloylpentaerythitol-O-pivaloxonium Hexachloroantimonate. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1969, 8, 888–888. 10.1002/anie.196908881. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen J. W.; Ewing S. Relative Heats of Formation of Cyclic Oxonoim Ions in Sulfuric Acid. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1971, 93, 5107–5111. 10.1021/ja00749a025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wilen S. H.; Delguzzo L.; Saferstein R. Experimental Evidence for AcO-7 Neighboring Group Participation. Tetrahedron 1987, 43, 5089–5094. 10.1016/S0040-4020(01)87685-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mathieson A. M. The Preferred Conformation of the Ester Group in Relation to Saturated Ring Systems. Tetrahedron Lett. 1965, 6, 4137–4144. 10.1016/S0040-4039(01)99578-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schweizer W. B.; Dunitz J. D. Structural Characteristics of the Carboxylic Ester Group. Helv. Chim. Acta 1982, 65, 1547–1554. 10.1002/hlca.19820650528. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- González-Outeiriño J.; Nasser R.; Anderson J. E. Conformation of Acetate Derivatives of Sugars and Other Cyclic Alcohols. Crystal Structures, NMR Studies, and Molecular Mechanics Calculations of Acetates. When is the Exocyclic C-O Bond Eclipsed?. J. Org. Chem. 2005, 70, 2486–2493. 10.1021/jo048295c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crich D.; Hu T.; Cai F. Does Neighboring Group Participation by Non-Vicinal Esters Play a Role in Glycosylation Reactions? Effective Probes for the Detection of Bridging Intermediates. J. Org. Chem. 2008, 73, 8942–8953. 10.1021/jo801630m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen P.; Crich D. Absence of Stereodirecting Participation by 2-O-Alkoxycarbonylmethyl Ethers in 4,6-O-Benzylidene-Directed Mannosylation. J. Org. Chem. 2015, 80, 12300–12310. 10.1021/acs.joc.5b02203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Upadhyaya K.; Subedi Y. P.; Crich D. Direct Experimental Characterization of a Bridged Bicyclic Glycosyl Dioxacarbenium Ion by 1H and 13C NMR Spectroscopy: Importance of Conformation on Participation by Distal Esters. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 25397–25403. 10.1002/anie.202110212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung M. E.; Piizzi G. gem-Disubstituent Effect: Theoretical Basis and Synthetic Applications. Chem. Rev. 2005, 105, 1735–1766. 10.1021/cr940337h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen H. H.; Bols M. Steric Effects Are Not the Cause of the Rate Difference in Hydrolysis of Stereoisomeric Glycosides. Org. Lett. 2003, 5, 3419–3421. 10.1021/ol030081e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen H. H.; Nordstrøm L. U.; Bols M. The Disarming Effect of the 4,6-Acetal Group on Glycoside Reactivity: Torsional or Electronic. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 9205–9213. 10.1021/ja047578j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moumé-Pymbock M.; Furukawa T.; Mondal S.; Crich D. Probing the Influence of a 4,6-O-Acetal on the Reactivity of Galactopyranosyl Donors: Verification of the Disarming Influence of the trans-gauche Conformation of C5-C6 Bonds. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 14249–14255. 10.1021/ja405588x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bock K.; Duus J. O. A Conformational Study of Hydroxymethyl Groups in Carbohydrates Investigated by 1H NMR Spectroscopy. J. Carbohydr. Chem. 1994, 13, 513–543. 10.1080/07328309408011662. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grindley T. B.Structure and Conformation of Carbohydrates. In Glycoscience: Chemistry and Chemical Biology, Fraser-Reid B., Tatsuta K., Thiem J. Eds.; Springer, 2001; Vol. 1, pp 3–51. [Google Scholar]

- Rao V. S. R.; Qasba P. K.; Balaji P. V.; Chandrasekaran R.. Conformation of Carbohydrates; Harwood Academic Publishers, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Ohrui H.; Horiki H.; Kishi H.; Meguro H. The Synthesis of D-(6R)- and (6S)-D-Glucose-6-2H through Stereospecific Photobromination of 1,6-Anhydro-β-D-glucopyranose Derivative. Agric. Biol. Chem. 1983, 47, 1101–1106. 10.1080/00021369.1983.10865756. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ohrui H.; Nishida Y.; Meguro H. The Synthesis of D-(6R)- and (6S)-(6-2H1)-Galactose. Agric. Biol. Chem. 1984, 48, 1049–1053. 10.1080/00021369.1984.10866239. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nishida Y.; Ohrui H.; Meguro H. 1H-NMR Studies of 6R- and 6S-Deuterated D-Hexoses: Assignment of the Preferred Rotamers about C5-C6 Bond of D-Glucose and D-Galactose Derivatives in Solutions. Tetrahedron Lett. 1984, 25, 1575–1578. 10.1016/S0040-4039(01)90014-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ohrui H.; Nishida Y.; Watanabe M.; Hori H.; Meguro H. 1H-NMR Studies of 6R- and 6S-Deuterated 1,6-Linked Disaccharides: Assignment of the Preferred Rotamers about C5-C6 Bond of 1,6-Disaccharides in Solutions. Tetrahedron Lett. 1985, 26, 3251–3254. 10.1016/S0040-4039(00)98164-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ichikawa Y.; Kuzuhara H. Synthesis of 1,6-Anhydro-2,3-di-O-benzoyl-4-O-(methyl 2,3,4-tri-O-benzoyl-α-L-iodpyranosyluronate)-β-D-glucopyranose from Cellobiose. Carbohydr. Res. 1983, 115, 117–129. 10.1016/0008-6215(83)88140-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dharuman S.; Amarasekara H.; Crich D. Interplay of Protecting Groups and Side Chain Conformation in Glycopyranosides. Modulation of the Influence of Remote Substituents on Glycosylation?. J. Org. Chem. 2018, 83, 10334–10351. 10.1021/acs.joc.8b01459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janssens J.; Risseeuw M. D. P.; Van der Eycken J.; Van Calenbergh S. Regioselective Ring Opening of 1,3-Dioxane-Type Acetals in Carbohydrates. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2018, 6405–6431. 10.1002/ejoc.201801245. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- DeNinno M. P.; Etienne J. B.; Duplantier K. C. A Method for the Selective Reduction of Carbohydrate 4,6-O-Benzylidene acetals. Tetrahedron Lett. 1995, 36, 669–672. 10.1016/0040-4039(94)02348-F. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Garegg P. J.; Hultberg H. A Novel, Reductive Ring-Opening of Carbohydrate Benzylidene Acetals with Unusual Regioselectivity. Carbohydr. Res. 1981, 93, C10–C11. 10.1016/S0008-6215(00)80766-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Garegg P. J.; Hultberg H.; Wallin S. A Novel, Reductive Ring-Opening of Carbohydrate Benzylidene Acetals. Carbohydr. Res. 1982, 108, 97–101. 10.1016/S0008-6215(00)81894-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Amarasekara H.; Dharuman S.; Kato T.; Crich D. Synthesis of Conformationally-Locked cis- and trans-Bicyclo[4.4.0] Mono-, Di- and Trioxadecane Modifications of Galacto- and Glucopyranose. Experimental Limiting 3JH,H Coupling Constants for the Estimation of Carbohydrate Side Chain Populations and Beyond. J. Org. Chem. 2018, 83, 881–897. 10.1021/acs.joc.7b02891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang C.-W.; Lin M.-H.; Chan C.-K.; Su K.-Y.; Wu C.-H.; Lo W.-C.; Lam S.; Cheng Y.-T.; Liao P.-H.; Wong C.-H.; Wang C.-C. Automated Quantification of Hydroxyl Reactivities: Prediction of Glycosylation Reactions. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 12413–12423. 10.1002/anie.202013909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shie C.-R.; Tzeng Z.-H.; Kulkarni S. S.; Uang B.-J.; Hsu C.-Y.; Hung S.-C. Cu(OTf)2 as an Efficient and Dual-Purpose Catalyst in the Regioselective Reductive Ring Opening of Benzylidene Acetals. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2005, 44, 1665–1668. 10.1002/anie.200462172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaudemer A.Determination of Configurations by NMR Spectroscopy. In Stereochemistry: Fundamentals and Methods, Kagan H. B. Ed.; Georg Thieme, 1977; Vol. 1, pp 44–136. [Google Scholar]

- Eliel E. L.; Wilen S. H.. Stereochemistry of Organic Compounds; Wiley, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Tvaroška I.; Gajdoš J. Angular Dependence of Vicinal Carbon-Proton Coupling Constants for Conformational Studies of the Hydroxymethyl Group in Carbohydrates. Carbohydr. Res. 1995, 271, 151–162. 10.1016/0008-6215(95)00046-V. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Morales E. Q.; Padron J. I.; Trujillo M.; Vázquez J. T. CD and 1H NMR Study of the Rotational Population Dependence of the Hydroxymethyl Group in β-Glucopyranosides on the Aglycon and Its Absolute Configuration. J. Org. Chem. 1995, 60, 2537–2548. 10.1021/jo00113a038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Padrón J. I.; Morales E. Q.; Vázquez J. T. Alkyl Galactopyranosides: Rotational Population Dependence of the Hydroxymethyl Group on the Aglycon and Its Absolute Configuration and on the Anomeric Configuration. J. Org. Chem. 1998, 63, 8247–8258. 10.1021/jo981002t. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nobrega C.; Vázquez J. T. Conformational Study of the Hydroxymethyl Group in D-Mannose Derivatives. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry 2003, 14, 2793–2801. 10.1016/S0957-4166(03)00623-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roën A.; Padron J. I.; Vázquez J. T. Hydroxymethyl Rotamer Populations in Disaccharides. J. Org. Chem. 2003, 68, 4615–4630. 10.1021/jo026913o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Codée J. D. C.; van den Bos L. J.; Litjens R. E. J. N.; Overkleeft H. S.; van Boeckel C. A. A.; van Boom J. H.; van der Marel G. A. Chemoselective Glycosylations Using Sulfonium Triflate Activator Systems. Tetrahedron 2004, 60, 1057–1064. 10.1016/j.tet.2003.11.084. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bullock C.; Hough L.; Richardson A. C. Rearrangement of α-D-Glucopyranose 4-Sulfonates to 1,4-Anhydro-β-D-galactopyranoses. J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun. 1971, 1276–1277. 10.1039/C29710001276. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- van Boeckel C. A. A.; Beetz T.; van Aelst S. F. Substituent Effects on Carbohydrate Coupling Reactions Promoted by Insoluble Silver Salts. Tetrahedron 1984, 40, 4097–4107. 10.1016/0040-4020(84)85091-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z.; Ollmann I. R.; Ye X.-S.; Wischnat R.; Baasov T.; Wong C.-H. Programmable One-Pot Oligosaccharide Synthesis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999, 121, 734–753. 10.1021/ja982232s. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- De Meo C.; Kamat M. N.; Demchenko A. V. Remote Participation-Assisted Synthesis of β-Mannosides. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2005, 2005, 706–711. 10.1002/ejoc.200400616. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Elferink H.; Mensink R. A.; White P. B.; Boltje T. J. Stereoselective β-Mannosylation by Neighboring-Group Participation. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 11217–11220. 10.1002/anie.201604358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douglas N. L.; Ley S. V.; Lucking U.; Warriner S. L. Tuning Glycoside Reactivity: New Tool for Efficient Oligosaccharide Synthesis. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans 1 1998, 51–66. 10.1039/a705275h. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Green L. G.; Ley S. V.. Protecting Groups: Effects on Reactivity, Glycosylation Stereoselectivity, and Coupling. In Carbohydrates in Chemistry and Biology; Ernst B., Hart G. W., Sinaÿ P. Eds.; Wiley-VCH: 2000; Vol. 1, pp 427–448. [Google Scholar]

- Namchuk M. N.; McCarter J. D.; Becalski A.; Andrews T.; Withers S. G. The Role of Sugar Substituents in Glycoside Hydrolysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000, 122, 1270–1277. 10.1021/ja992044h. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crich D. Methodology Development and Physical Organic Chemistry: A Powerful Combination for the Advancement of Glycochemistry. J. Org. Chem. 2011, 76, 9193–9209. 10.1021/jo2017026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia B. A.; Gin D. Y. Dehydrative Glycosylation with Activated Diphenyl Sulfonium Reagents. Scope, Mode of C(1)-Hemiacetal Activation, and Detection of Reactive Glycosyl Intermediates. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000, 122, 4269–4279. 10.1021/ja993595a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Qiao Y.; Ge W.; Jia L.; Hou X.; Wang Y.; Pedersen C. M. Glycosylation Intermediates Studied Using Low Temperature 1H- and 19F-DOSY NMR: New Insight into the Activation of Trichloroacetimidates. Chem. Commun. 2016, 52, 11418–11421. 10.1039/C6CC05272J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radom L. Ab initio Molecular Orbital Calculations on Acetyl Cations. Relative Hyperconjugative Abilities of Carbon-X Bonds. Aust. J. Chem. 1974, 27, 231–239. 10.1071/CH9740231. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bentley T. W. Structural Effects on the Solvolytic Reactivity of Carboxylic and Sulfonic Acid Chlorides. Comparisons with Gas-Phase Data for Cation Formation. J. Org. Chem. 2008, 73, 6251–6257. 10.1021/jo800841g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miljkovic M.; Yeagley D.; Deslongchamps P.; Dory Y. L. Experimental and Theoretical Evidence of Through-Space Electrostatic Stabilization of the Incipient Oxocarbenium Ion by an Axially Oriented Electronegative Substituent During Glycopyranoside Acetolysis. J. Org. Chem. 1997, 62, 7597–7604. 10.1021/jo970677d. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smith D. M.; Woerpel K. A. Electrostatic Interactions in Cations and their Importance in Biology and Chemistry. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2006, 4, 1195–1201. 10.1039/b600056h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen H. H.; Bols M. Stereoelectronic Substituent Effects. Acc. Chem. Res. 2006, 39, 259–265. 10.1021/ar050189p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods R. J.; Andrews C. W.; Bowen J. P. Molecular Mechanical Investigations of the Properties of Oxacarbenium Ions. Application to Glycoside Hydrolysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1992, 114, 859–864. 10.1021/ja00029a008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this study are available in the published article and its Supporting Information.