Abstract

The synthesis of (±)-angustatin A, a phenanthrene-containing cyclophane that possesses conformational chirality, is reported. Key steps include a Pd-catalyzed Negishi coupling to assemble the necessary terphenyl intermediate, its closure into a 14-membered macrocycle via a catalytic-in-phosphine Wittig olefination, and finally a Pt-catalyzed alkyne hydroarylation, which is able to assemble the phenanthrene unit despite the thermodynamic cost of significantly bending arene A from the ideal plane.

The cyclophane angustatin A, which has been isolated from the liverwort Asterella angusta, displays several intriguing architectural features that makes it an attractive synthetic objective.1 It shares with the closely related and more popular target cavicularin a highly strained 14-membered macrocyclic core; however, in contrast to the structure of the latter, in angustatin A the phenanthrene motif remains completely unsaturated.2,3 An additional hydroxy-substituent on ring D of angustatin A completes the differences between the two natural products. Although no crystallographic evidence is available to date, angustatin A is expected to contain a boat-like arene moiety (ring A) and probably a significantly twisted phenanthrene unit (Scheme 1). The nonequivalent 1H NMR signals from ring A, and their unusual chemical shift, also suggest that as result of its rigid skeleton angustatin A displays conformational chirality;2,4 however, no optical rotation value has been reported to date.

Scheme 1. Synthetic Strategy Towards Angustatin A.

It is for these unique molecular attributes, and also due to our long-term interest in the synthesis of twisted polyaromatic structures via Au(I)- or Pt(II)-catalyzed alkyne hydroarylation reactions, that we decided to develop a synthetic route toward angustatin A. Specifically, we plan to construct the phenanthrene unit at a late stage of the synthesis.5 This will allow a comparative evaluation of the available catalysts in a challenging cyclization event. Note that the transformation of the 2-alkynyl biaryl moiety in I (Scheme 1, highlighted in red) into the desired phenanthrene must occur by overcoming the thermodynamic cost of heavily contorting aromatic ring A.

These notions are reflected in our retrosynthetic plan. We initially aimed at the preparation of cyclophane intermediate I, in which the phenanthrene skeleton is still not assembled and, consequently, the ring strain of the structure is significantly reduced. The higher flexibility of I should also facilitate its closure from II via Wittig olefination. The preparation of precursor II was envisioned through the Negishi coupling of conveniently substituted biphenyl and diarylether fragments III and IV, which were respectively prepared in short sequences from simple commercially available materials (Scheme 1).

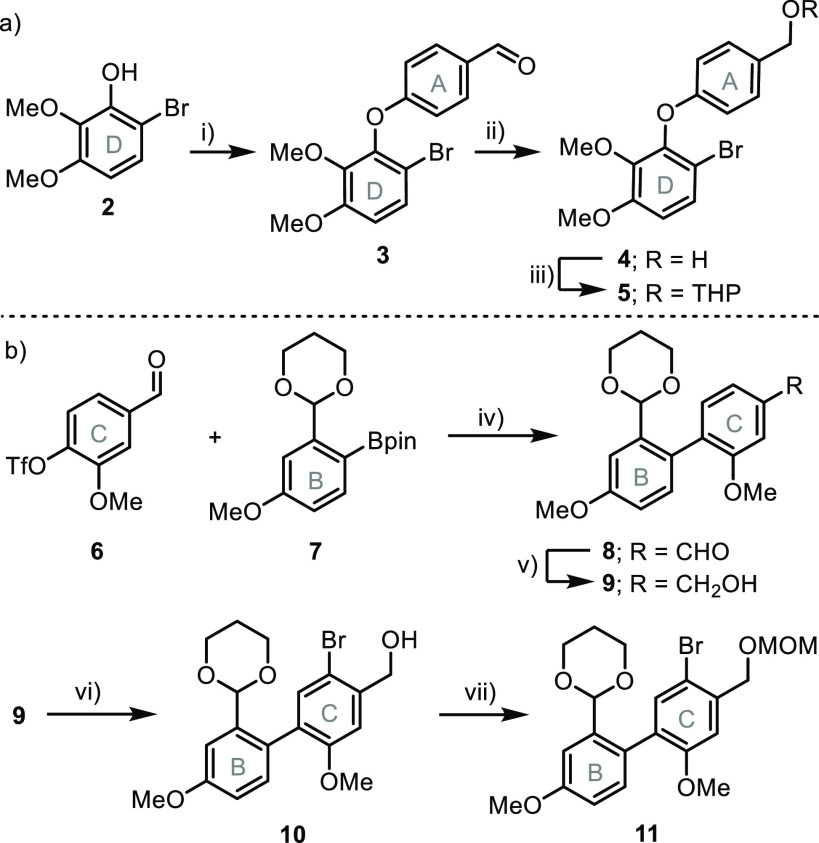

Hence, the assembly of fragment IV started with 2,3-di(methoxy)phenol, which was regioselectively brominated on multigram scale to deliver 2.6 Treatment of this compound with 4-fluorobenzaldehyde delivered ether 3.7 Reduction of the aldehyde unit in 3 to the corresponding benzylic alcohol 4 took place under standard conditions, and final protection with dihydropyrane gave rise to 5 (Scheme 2a).8

Scheme 2. Elaboration of the Synthetic Equivalents of Fragments III and IV.

Reagents and conditions: (i) 4-fluorobenzaldehyde, K2CO3, DMSO, 95 °C, 40%; (ii) NaBH4, THF/EtOH, r.t., 84%; (iii) DHP, PPTS (10 mol %), CH2Cl2, 92%; (iv) Pd(PPh3)4 (13 mol %), Na2CO3, EtOH/toluene 105 °C, 80%; (v) NaBH4, THF/EtOH, 0 °C, 97%; vi) NBS, THF, −78 °C, 75%; (vii) MOMCl, DIPEA, CH2Cl2, 0 °C, 99%.

The equivalent of fragment III was prepared in a straightforward sequence via the Suzuki coupling between already described triflate 6 and pinacol borate 7 to deliver biaryl 8; both precursors are efficiently prepared in multigram scale from vanillin and m-anisaldehyde, respectively.9,10 The reduction of the aldehyde functionality in 8 to the corresponding alcohol 9 is required at this stage in order to introduce the bromine substituent selectively at 4-position of ring C in 10.11 Final MOM protection of the benzylic alcohol affords 11 in a 58% yield after 4 steps (Scheme 2b).

The Negishi reaction between 5 and 11 delivered 12 albeit in a moderate yield; this is probably a consequence of the steric bulk of the fragments to be coupled, which are both o-substituted. Actually, the 1H NMR spectrum of 12 depicts many broad signals, indicating that rotation between rings B–C and C–D are hindered (see the Supporting Information). In the subsequent steps, compound 14 was generated to enable the desired macrocyclization through an intramolecular Wittig olefination.12 This was done by acid removal of the two acetal moieties in 12 and transformation of the benzylic alcohol unit in 13 into a bromide via Appel reaction. At that stage, addition of PPh3 to 14 generated the corresponding phosphonium salt, which upon treatment with NaOMe delivered the desired macrocycle 15 in a 38% yield (two steps). 1H NMR analysis of the crude reaction mixture indicated that under these experimental conditions the (E)-stereoisomer is exclusively obtained (3J(RHC=CHR′) = 16.9 Hz).13 The assembly of 15 was also attempted via the alternative, and more direct, reaction of 13 with [Ph3PH]Br followed by basic treatment; however, this broadly used and more direct protocol was lower yielding for that specific substrate.14 HPLC analysis of a sample of 15 on chiral stationary phase (Daicel IA-3 SFC) followed by measurement of the circular dichroism (CD) spectrum of the eluates showed that this cyclophane already exists as a mixture of two configurationally stable enantiomers.

This result suggests that if a catalytic-in-phosphine Wittig reaction could be made operative for the ring closing step, then an enantioselective synthesis of angustatin A might be developed. Thus, we initially turned our attention to 22, a 9-phosphabicyclo[4.2.1]nonane derivative that has already demonstrated its utility as a catalyst for Wittig reactions when diphenylsilane is used as a reductant.15 To our delight, the macroolefination took place under these conditions in moderate yield (60%); yet, instead of 15 the product obtained was 16, in which the regio- and diastereoselective hydrosilylation of the initially formed double bond had occurred. Actually, treatment of 15 with H2SiPh2 (1.0 equiv) under the reaction conditions applied during the olefination step (toluene, 125 °C) affords a mixture that contains the (Z)-isomer of 15 and 16. Hydrosilylation reactions are often promoted by metal, Lewis acid, or Lewis base catalysts;16 we believe, however, that the release of strain in 15 facilitates this spontaneous addition. The unexpected hydrosilylation is inconsequential regarding the total number of steps and final yield, since the treatment of 16 with TBAF quantitatively delivers 17, and otherwise the double bond in 15 would need to be reduced. When (1R,4R)-7-phenyl-7-phosphabicyclo[2.2.1] heptane-7-oxide 23a was employed as the catalyst under otherwise identical conditions, the macroolefination still worked (42% yield) but compound 16 was obtained with low enantioselectivity (40% ee, determined after desilylation in 17). The more sterically demanding catalyst 23b is characterized by reduced reactivity and required higher operating temperatures; unfortunately, when the reaction conditions were forced (180 °C), only decomposition was observed. It is for this reason that the following steps of the synthesis, namely, MOM-deprotection of 17 to alcohol 18 and the homologation of this moiety into an alkyne in 21, were continued with racemic material (Scheme 3).

Scheme 3. Assembling the Macrocycle via the Wittig Reaction.

Reagents and conditions: (i) nBuLi, THF, −78 °C, 1 h, then ZnBr2, r.t., 2 h, and then 11 (1.0 equiv), Pd(PPh3)4 (5 mol %), 100 °C, 61%; (ii) HCl in EtOH, r.t., 84%; (iii) CBr4 (1.1 equiv), PPh3 (1.1 equiv), 0 °C, 80%; (iv) PPh3 (1.1 equiv), toluene, 110 °C, and then NaOMe (3.0 equiv), r.t., CH2Cl2, 6 h, 38%, (two steps); (v) 22 (30 mol %), KOtBu (2.0 equiv), Ph2SiH2 (1.2 equiv), toluene, 110 °C, 3 d, 60%; (vi) 23a (30 mol %), KOtBu (2.0 equiv), Ph2SiH2 (1.2 equiv), toluene, 125 °C, 3 d, 42% or 23b (30 mol %), KOtBu (2.0 equiv), Ph2SiH2 (1.2 equiv), toluene, 180 °C, 3 d, decomp.; (vii) TBAF (1.5 equiv), THF, r.t., quant.; (viii) HCl, acetone, r.t., 74%; (ix) DMP (1.5 equiv), K2CO3 (3 equiv), r.t., 98%; (x) [Ph3PCH2Br]Br (1.1 equiv), KOtBu (1.3 equiv), THF, −78 °C, 73%; (xi) Et2NH (2.0 equiv), nBuLi (2.0 equiv), −78 °C, then 20 (1.0 equiv), r.t., 12 h., 99%. Molecular structures of 16 and 19 are in the solid state. Anisotropic displacements are shown at the 50% probability level. Hydrogen atoms and solvent molecules were removed for clarity.

At that point, the stage was set for the key 6-endo-dig hydroarylation step. Two typical catalytic conditions for this reaction were initially chosen, namely, PtCl2 in Cl(CH2)2Cl at 80 °C17 and Ph3PAuCl/AgSbF6 in CH2Cl2 at r.t.18 The first one proved to be moderately effective, furnishing the desired phenanthrene 24 in a 33% yield, whereas the use of the Au-based catalytic system resulted in the formation of just traces of the desired product. Up to a certain level, increasing the π-acceptor character of the ancillary ligand coordinated to Au seems to be beneficial. For example, (PhO)3PAuCl and 26, bearing an α-pyridiniophosphine ligand, delivered 24 in 31% and 61% yields, respectively;19 however, the employment of Au-precatalysts based on even more electron-poor α-cationic phosphines resulted in fast catalyst decomposition after activation with AgSbF6.20 Interestingly, it was the Pt precatalyst 25 the one that more effectively promoted the cyclization in terms of isolated yields.21 We ascribe this remarkable result to several synergic effects: (i) the enhanced electrophilicity at Pt center, which derives from the use of a polyfluoronated and cationic ancillary phosphine; (ii) the low appetence of the Pt(II) atom to be reduced by the substrate; and (iii) the robustness of 25 at elevated temperatures (Scheme 4a and b).22

Scheme 4. Construction of the Phenanthrene Core.

Reagents and conditions: method A, PtCl2 (5 mol %), dichloroethane, 80 °C, 12h; method B, Au catalyst (5 mol %), AgSbF6 (5 mol %), rt, 12 h; method C, 25 (5 mol %), AgSbF6 (5 mol %), toluene, 80 °C, 1.5 h; method D, 26 (5 mol %), AgSbF6 (5 mol %), rt, 1 h. Molecular structure of 22 in the solid state. Anisotropic displacements are shown at the 50% probability level. Solvent molecules were removed for clarity.

X-ray analysis of 24 confirmed that the angustatin A core structure had been assembled despite the need to bend arene A 17° from ideal planarity and the imposition of a torsion to the phenanthrene unit (ΦC1–C2–C3–C4 = 13.7°) to achieve this goal (Scheme 4c). This situation seems to be even more strained than that in the case of cavicularin, where the same analysis only yields a mean bending of 14° in ring A.3c The higher torsional flexibility of the 9,10-dihydrophenanthrene unit in cavicularin when compared to the phenanthrene in 24 probably accounts for this partial strain relaxation.

Finally, removal of the methyl protecting groups in 24 with BBr3 (10.0 equiv., r.t.) allowed the clean production and isolation of angustatin A (1) (Scheme 5a). All spectral data (1H and 13C NMR, HRMS) from the synthetic material were consistent to those reported for the natural product.1 Crystals of 1 could not be grown; yet, the addition of 1 equiv of AcOK to a MeOH solution of 1 readily induced the crystallization of the angustatin A·KOAc complex, in which a potassium cation coordinates the catechol moiety of 1 (Scheme 5b). Finally, the separation of the constitutional enantiomers of 1 was carried out via semipreparative HPLC with a chiral stationary phase (Daicel IA-3 SFC). The CD spectra of the samples were, as expected, mirror images (Scheme 5c), and the optical rotation of both optically pure enantiomers showed opposite values, [α]20D = −210 (c 0.13, MeOH, for the second eluted enantiomer); these phenomena definitively proved that 1 displays conformational chirality.

Scheme 5. Final Deprotection.

Reagents and conditions: (i) BBr3 (10.0 equiv), CH2Cl2, r.t., 95%; Molecular structure of 1·KOAc in the solid state. Anisotropic displacements are shown at the 30% probability level; cocrystallized MeOH molecules are shown. Enantiomer A eluted first (red line), and enantiomer B eluted second (green line)

In conclusion, the first synthesis of angustatin A has been accomplished. Noteworthy features of the route developed are the use of a Wittig reaction catalytic-in-phosphorus to effect the macrocyclization and the late construction of the phenanthrene ring via Pt-catalyzed alkyne hydroarylation. As initially expected, angustatin A displays conformational chirality due to ring strain.

Acknowledgments

Support from the DFG (INST 186/1237-1, INST 186/1324-1, and INST 186/1352-1) is gratefully acknowledged. We also thank Mrs. L. González and Mr. M. Simon, both from the University of Göttingen, for the preparation of starting materials and HPLC analyses, respectively.

Data Availability Statement

The Data underlying this study are available in the published article and its Supporting Information.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.orglett.3c02742.

General experimental procedures and characterization data, including 1H- and 13C NMR spectra of new compounds (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Qu J.-B.; Sun L.-M.; Lou H.-X. Antufugal variant bis(bibenzyl)s from the livwerwort Astrella angusta. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2013, 24, 801–803. 10.1016/j.cclet.2013.05.035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Toyota M.; Yoshida T.; Kan Y.; Takaoka S.; Asakawa Y. (+)-Cavicularin: A Novel Optically Active Cyclic Bibenzyl-Dihydrophenanthrene Derivative from the Liverwort Cavicularia densa Steph. Tetrahedron Lett. 1996, 37, 4745–4748. 10.1016/0040-4039(96)00956-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- For the synthesis of cavicularin, see:; a Zhao P.; Beaudry C. M. Enantioselective and Regioselective Pyrone Diels-Alder Reactionns of Vinyl Sulfones: Total Synthesis of (+)-Cavicularin. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 10500–10503. 10.1002/anie.201406621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Zhao P.; Beaudry C. M. Total Synthesis of (±)-Cavicularin: Control of Pyrone Diels-Alder Regiochemistry Using Isomeric Vinyl Sulfones. Org. Lett. 2013, 15, 402–405. 10.1021/ol303390a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Takiguchi H.; Ohmori K.; Suzuki K. Synthesis and Determination of the Absolute Confuguration of Cavicularin by a Symmetrization/Asymmetrization Approach. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 10472–10476. 10.1002/anie.201304929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Harada K.; Makino K.; Shima N.; Okuyama H.; Esumi T.; Kubo M.; Hioki H.; Asakawa Y.; Fukuyama Y. Total synthesis of riccardin C and (±)-cavicularin via Pd-catalyzed Ar-Ar cross couplings. Tetrahedron 2013, 69, 6959–6968. 10.1016/j.tet.2013.06.064. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; e Harrowven D. C.; Woodcock T.; Howes P. D. Total Synthesis of Cavicularin and riccardin C: Addressing the Synthesis of an Arene That Adopts a Boat Conformation. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2005, 44, 3899–3901. 10.1002/anie.200500466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao P.; Song C. Macrocyclic Bisbibenzyls: Properties and Synthesis. Studies in Natural Products Chemistry 2018, 55, 73–110. 10.1016/B978-0-444-64068-0.00003-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Carreras J.; Gopakumar G.; Gu L.; Gimeno A.; Linowski P.; Petuškova J.; Thiel W.; Alcarazo M. Polycationic Ligands in Gold Catalysis: Synthesis and Applications of Extremely π-Acidic Catalysts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 18815–18823. 10.1021/ja411146x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Carreras J.; Patil M.; Thiel W.; Alcarazo M. Exploiting the π-acceptor properties of carbene-stabilized phosphorus centered trications [L3P]3+: applications in Pt(II) catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 16753–16758. 10.1021/ja306947m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pla D.; Albericio F.; Álvarez M. Regioselective Monobromination of Free and Protected Phenols. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2007, 2007, 1921–1924. 10.1002/ejoc.200600971. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Foyer G.; Chanfi B.-H.; Virieux D.; David G.; Caillol S. Aromatic dialdehyde precursors from lignin derivatives for the synthesis of formaldehyde-free and high char yield phenolic resins. Eur. Polym. J. 2016, 77, 65–74. 10.1016/j.eurpolymj.2016.02.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maezaki N.; Mayuko I.; Yuyama S.; Sawamoto H.; Iwata C.; Tanaka T. Studies on Intramolecular Alkylation of an a-Sulfinyl Vinylic Carbanion: a Novel Route to Chiral 1-Cycloalkenyl Sulfoxides. Tetrahedron 2000, 56, 7927–7945. 10.1016/S0040-4020(00)00713-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Si T.; Li B.; Xiong W.; Xu B.; Tang W. Efficient cross-coupling of aryl/alkenyl triflates with acyclic secondary alkylboronic acids. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2017, 15, 9903–9909. 10.1039/C7OB02531A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speicher A.; Groh M.; Zapp J.; Schaumlöffel A.; Knauer M.; Bringmann G. A Synthesis-Driven Structure Revision of ‘Plagiochin E’, a Highly Bioactive Bisbibenzyl. Synlett 2009, 2009 (11), 1852–1858. 10.1055/s-0029-1217510. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Deveau A. M.; Macdonald T. L. Practical synthesis of biaryl colchicinoids containing 3′,4′-catechol ether-based A-rings via Suzuki cross-coupling with ligandless palladium in water. Tetrahedron Lett. 2004, 45, 803–807. 10.1016/j.tetlet.2003.11.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Selected examples for the use of Wittig olefination for the macrocyclization step during the synthesis of structurally related bis(bibenzyl)s:; a Speicher A.; Groh M.; Hennrich M.; Huynh A.-M. Syntheses of Macrocyclic Bis(bibenzyl) Compounds Derived from Perrottetin E. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2010, 2010, 6760–6778. 10.1002/ejoc.201001023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Eicher T.; Fey S.; Puhl W.; Büchel E.; Speicher A. Synthesis of Cyclic Bisbibenzyl Systems. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 1998, 1998, 877–888. . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Structure Determination of Organic Compounds; Pretsch E.; Bühlmann P.; Affolter C., Eds.; Springer, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Speicher A.; Kolz J.; Sambanje R. P. Syntheses of Chlorinated Bisbibenzyls from Bryophytes. Synthesis 2002, 17, 2503–2512. 10.1055/s-2002-35629. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Coyle E. E.; Doonan B. J.; Holohan A. J.; Walsh K. A.; Lavigne F.; Krenske E. H.; O'Brien C. J. Catalytic Wittig Reactions of Semi- and Nonstabilized Ylides Enabled by Ylide Tuning. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 12907–12911. 10.1002/anie.201406103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Vedejs E.; Cabaj J.; Peterson M. J. Wittig Ethylidenation of Ketones: Reagent Control of Z/E Selectivity. J. Org. Chem. 1993, 58, 6509–6512. 10.1021/jo00075a064. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nakajima Y.; Shimada S. Hydrosilylation reaction of olefins: recent advances and perspectives. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 20603–20616. 10.1039/C4RA17281G. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Mamane V.; Hannen P.; Fürstner A. Synthesis of Phenanthrenes and Polycyclic Heteroarenes by Transition-Metal Catalyzed Cycloisomerization Reactions. Chem. Eur. J. 2004, 10, 4556–4575. 10.1002/chem.200400220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Fürstner A.; Mamane V. Flexible Synthesis of Phenanthrenes by a PtCl2-Catalyzed Cycloisomerization Reaction. J. Org. Chem. 2002, 67, 6264–6267. 10.1021/jo025962y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reetz M. T.; Sommer K. Gold-Catalyzed Hydroarylation of Alkynes. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2003, 2003, 3485–3496. 10.1002/ejoc.200300260. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Tinnermann H.; Nicholls L. D. M.; Johannsen T.; Wille C.; Golz C.; Goddard R.; Alcarazo M. N-Arylpyridiniophosphines: Synthesis, Structure, and Applications in Au(I) Catalysis. ACS Catal. 2018, 8, 10457–10463. 10.1021/acscatal.8b03271. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Tinnermann H.; Wille C.; Alcarazo M. Synthesis, Structure, and Applications of Pyridiniophosphines. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 8732–8736. 10.1002/anie.201401073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johannsen T.; Golz C.; Alcarazo M. α-Cationic Phospholes: Synthesis and Applications as Ancillary Ligands. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 22779–22784. 10.1002/anie.202009303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozma A.; Deden T.; Carreras J.; Wille C.; Petuškova J.; Rust J.; Alcarazo M. Coordination Chemistry of Cyclopropenylidene-Stabilized Phosphenium Cations: Synthesis and Reactivity of Pd and Pt Complexes. Chem. Eur. J. 2014, 20, 2208–2214. 10.1002/chem.201303686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alcarazo M. Synthesis, Structure, and Applications of α-Cationic Phosphines. Acc. Chem. Res. 2016, 49, 1797–1805. 10.1021/acs.accounts.6b00262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The Data underlying this study are available in the published article and its Supporting Information.