Abstract

In Benin maternal mortality remains high at 397 deaths per 100,000 live births, despite 80% of births being attended by skilled birth attendants in health facilities. To identify childbirth practices that potentially contribute to this trend, an ethnographic study was conducted on the use of biomedical and alternative health services along the continuum of maternal care in Allada, Benin. Data collection techniques included in-depth interviews (N = 83), informal interviews (N = 86), observations (N = 32) and group discussions (N = 3). Informants included biomedical, spiritual and alternative care providers and community members with a variety of socioeconomic and religious profiles. In Southern Benin alternative and spiritual care, inspired by the Vodoun, Christian or Muslim religions, is commonly used in addition to biomedical care. As childbirth is perceived as a “risky journey to the unknown”, these care modalities aim to protect the mother and child from malevolent spirits, facilitate the birth and limit postpartum complications using herbal decoctions and spiritual rites and rituals. These practices are based on mystical interpretations of childbirth that result in the need for additional care during facility-based childbirth. Because such complementary care is not foreseen in health facilities, facility-based childbirth is initiated only at an advanced stage of labour or at the onset of a perceived immediate life-threatening complication for the mother or baby. Programmes and policies to reduce maternal mortality in Benin must seek synergies with alternative providers and practices and consider the complementary and integrated use of alternative and spiritual care practices that are not harmful.

Keywords: childbirth, continuum of care, Benin, health-seeking behaviour, alternative care, spiritual care

Résumé

Au Bénin, la mortalité maternelle demeure élevée, à 397 décès pour 100 000 naissances vivantes, même si 80% des accouchements bénéficient de l’aide d’accoucheuses qualifiées dans des établissements de santé. Pour identifier les pratiques d’accouchement qui contribuent potentiellement à cette tendance, une étude ethnographique a été menée sur l’utilisation de services de santé biomédicaux et alternatifs tout au long du continuum de soins maternels à Allada, Bénin. Les techniques de recueil des données comprenaient des entretiens approfondis (n = 83), des entretiens informels (n = 86), des observations (n = 32) et des discussions de groupe (n = 3). Les informateurs incluaient des prestataires de soins biomédicaux, spirituels et alternatifs ainsi que des membres de la communauté présentant différentes caractéristiques socioéconomiques et religieuses. Au Bénin méridional, les soins alternatifs et spirituels, inspirés des religions vaudou, chrétienne ou musulmane, sont fréquemment utilisés en complément des soins biomédicaux. L’accouchement étant considéré comme « un voyage risqué vers l’inconnu », ces modalités de soins visent à protéger la mère et l’enfant des esprits malveillants, à faciliter la naissance et à limiter les complications du post-partum grâce à des décoctions de plantes ainsi que des rites et rituels spirituels. Ces pratiques sont fondées sur des interprétations mystiques de l’accouchement qui génèrent un besoin de soins additionnels lors de l’accouchement en établissement de santé. Puisque ces soins complémentaires ne sont pas prévus dans les établissements de santé, l’accouchement en établissement de santé n’est initié qu’à un stade avancé du travail ou au début d’une complication jugée comme mettant immédiatement en danger la vie de la mère ou du bébé. Les programmes et politiques de réduction de la mortalité maternelle au Bénin doivent rechercher des synergies avec des prestataires et des pratiques alternatives, et envisager l’utilisation complémentaire et intégrée de pratiques de soins alternatifs et spirituels qui ne sont pas nocives.

Resumen

En Benín, la tasa de mortalidad materna continúa siendo alta, 397 muertes por cada 100,000 nacimientos vivos, a pesar de que el 80 % de los partos son atendidos por parteras calificadas en establecimientos de salud. Para identificar las prácticas de parto que posiblemente contribuyen a esta tendencia, se realizó un estudio etnográfico sobre el uso de servicios de atención biomédica y alternativa a lo largo del continuum de atención materna en Allada, Benín. Las técnicas de recolección de datos fueron: entrevistas a profundidad (N = 83), entrevistas informales (N = 86), observaciones (N = 32) y discusiones en grupo (N = 3). Los informantes eran prestadores de servicios de atención biomédica, espiritual y alternativa, así como miembros de la comunidad con una variedad de perfiles socioeconómicos y religiosos. En Benín meridional, además de la atención biomédica, se brinda comúnmente atención alternativa y espiritual inspirada por las religiones vudú, cristiana o musulmana. Dado que el parto es percibido como un “viaje arriesgado hacia lo desconocido”, estas modalidades de atención pretenden proteger a la madre y al infante de espíritus malévolos, facilitar el parto y limitar las complicaciones posparto utilizando decocciones de hierbas y ritos y rituales espirituales. Estas prácticas se basan en interpretaciones místicas del parto que resultan en la necesidad de atención adicional durante el parto institucional. Dado que en los establecimientos de salud no se prevé dicha atención complementaria, el parto institucional se inicia solo en una etapa avanzada del trabajo de parto o al inicio de una complicación inmediata percibida potencialmente mortal para la madre o el bebé. Los programas y las políticas para reducir la mortalidad materna en Benín deben buscar sinergia con prácticas y prestadores de servicios alternativos, y considerar el uso complementario e integrado de prácticas de atención alternativa y espiritual que no sean dañinas.

Introduction

The birth of a child is an intense and potentially stressful event in a woman's life, especially in Benin, where maternal mortality is very high, with an estimated ratio of 397 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births.1 The World Health Organization (WHO) promotes access to and use of quality reproductive health services as key interventions to reduce preventable maternal and newborn deaths. Specifically, WHO suggests that improving the quality of preventive and curative care across the continuum of maternal health care could have a major impact on maternal, fetal and newborn survival.2,3 Recent Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) data1 show that a high proportion (89%) of pregnant women in Benin have at least one antenatal care (ANC) visit and a predominant majority (85%) of women report having given birth in a facility. Health facility rates in Benin are particularly high compared to what is reported (55%) for the whole west and central African region. Historically, Benin has had higher rates of ANC use and facility-based birth than other countries in the West African region. This has been attributed to a higher number of trained midwives in the country since the early twentieth century, which has contributed to making facility-based childbirth a common practice in Beninese society.4 In addition, in December 2008, the Beninese government decreed that caesarean sections would be free of charge to improve care for pregnant women.5 Despite this high utilisation of health facilities for childbirth, the maternal and neonatal mortality rate remain worryingly high, pointing to failures in quality of care in health facilities.

Factors associated with poorer access to care have been shown to include individual and family characteristics, such as high parity, low socioeconomic status, low education, remoteness from health facilities and living in rural areas.6,7 These factors and their associations with health-seeking behaviours have been extensively studied, in part because of the availability of data from large, repeated, nationally representative household surveys such as the DHS. However, these factors are not directly related to the quality of services provided in health facilities and have not been understood in the historical socio-cultural context that underlies women's reproductive choices and obligations. Nonetheless, such contextual factors often inform local treatment-seeking itineraries during pregnancy and childbirth.8

Although the WHO model of quality of care recognises the multidimensional nature of what “quality” should mean across the continuum of maternal health care, emphasising that respectful delivery and emotional support are just as important as evidence-based medical practices during childbirth,9 little research has been done in Benin on what appropriate “care” means from a local socio-cultural perspective, and how it may or may not contextually align with the guidelines for childbirth care underpinned by the WHO model's clinical practices. In Benin, the act of giving birth is considered socially, culturally and biomedically to be a critical time when both woman and baby are at risk. To mitigate this risk, the pregnant woman receives special attention and protection from her husband, family and the entire community. In Benin, it has been shown that the birthing process involves other forms of care in addition to those received in biomedical health facilities.8 Indeed, 80% of Beninese actively use “traditional medicine” – including during childbirth – and there are six times as many “traditional practitioners” as physicians in Benin, i.e. around 11,000 traditional practitioners and only 1,700 physicians for a population of 11.2 million people.10

Our study aimed to elucidate some of these non-medical factors that potentially contribute to the paradoxical situation of high rates of facility-based childbirth with skilled birth attendants at the same time as high maternal and infant mortality rates. As such, we investigated the apparent gaps in the continuum of maternal health care, results of which have been published elsewhere.11 In this article, we zoom in on the multiple modalities of care involved specifically in childbirth in southern Benin.

Methods

Study type and site

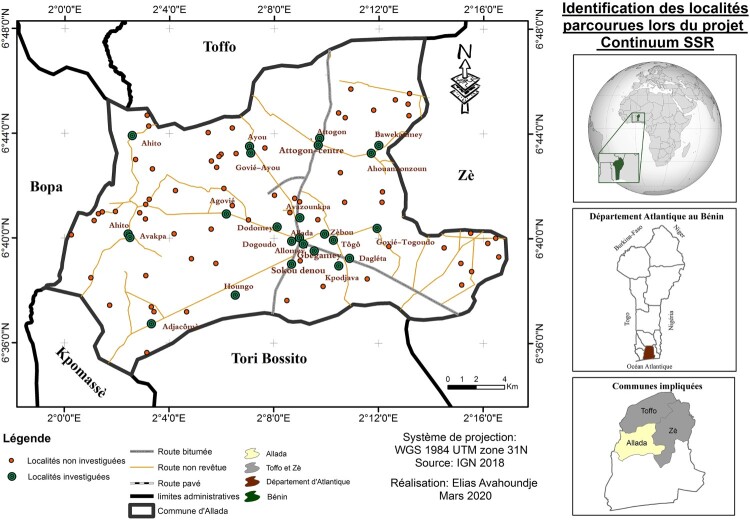

An ethnographic study was conducted in the health zone (HZ) of Allada-Toffo-Zè, a semi-rural area rich in modern (biomedical), traditional and spiritual care, in the Atlantic Department (administrative territorial unit similar to a county) of Benin from January 2018 to March 2020.

Out of the 12 “departments” of the country, the study region was selected based on the following characteristics: (i) representative of the main ethnic groups in Benin, as such avoiding border regions or cosmopolitan areas to reduce the influence of cross-border migration on the data collected; (ii) close enough to the research centre for travel to be feasible within the resources available; (iii) an identified gap between the use of different services along the continuum of maternal, neonatal and family planning care, analysed from service utilisation data (DHS 2011–2012). These criteria jointly led to the selection of the Atlantic region, out of which the Allada-Toffo-Zè health zone was selected because it included the cultural epicentre of the region, Allada. Founded in the sixteenth century, the ancient kingdom of Allada played a central historical role in the emergence of the kingdoms of Danxomè (now Benin) and is still considered a reference point for pre-colonial cultures and practices related to birth, life, sexuality, reproduction and death in southern Benin. According to the Fourth General Population and Housing Census conducted in 2013, the commune of Allada had 19 public health facilities, including the Allada zone hospital, and five private health facilities, including one faith-based health facility (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Map of the area and localities visited during the ethnographic study

Study population

The municipality of Allada covers a population of 127,512 inhabitants12 who speak mainly Aïzo and Fon. Most of the working population is engaged in agriculture, fishing and hunting, followed by trade, catering and accommodation.12 In the agricultural sector, most households are engaged in large-scale plantation, i.e. processing units for pineapple, palm nuts, cassava and palm wine.

Data collection

Sampling

The target population for this study was healthcare users (and non-users) and providers in the public, private, traditional, and home care sectors, targeting pre-pregnancy, pregnancy, childbirth and postpartum care. Participants were selected based on the principles of theoretical sampling, where the researcher simultaneously collects and analyses data based on existing theories to guide the next phase of the research and the associated selection of new participants. Sampling also aimed to progressively select for maximum variation in profiles in terms of localities, gender, age, marital status, socioeconomic status, occupation, religious beliefs, ethnicity and non-use or use of formal maternal health services.

Data collection techniques

The research team was composed of three anthropologists and three physicians who are experts in public health. The Beninese health system is structured into 34 health zones, including the Allada-Toffo-Zè health zone, for better care of the population. The researchers had no previous connections in the study sites, although three of the researchers were of the same Fon ethnicity and were able to speak the Fon language with participants. Prior to the start of data collection, political and health authorities in the three communes of the Allada-Toffo-Zè health zone were contacted to negotiate their support and assistance throughout the study and select specific study sites. Potential informants in those study sites were then approached face to face at the community level and in healthcare facilities for social interaction. Access to informants was achieved primarily through snowball sampling, whereby some key informants (primarily health centre staff such as midwives and local authority figures such as village chiefs) referred us to other potential participants. The same researchers visited the same informants multiple times, which was an additional way to build trust between researcher and participant. Fieldwork continued until theoretical saturation was reached.

Several qualitative research techniques were triangulated to strengthen the insights emerging from the data and test the internal validity. Data collection techniques included in-depth interviews (N = 83), informal interviews (N = 86), observations (N = 32) and group discussions (N = 3).

In-depth interviews were conducted using an interview guide that was continually adapted to fit the iterative nature of ethnographic research. These interviews were conducted by two female anthropologists and a female physician, most often in Fon language. Interview duration depended on the preference of the informant, the richness of the response and whether the interview was done during a return visit or a first visit. Interviews lasted between 25 and 75 minutes. Interviews always took place face to face, most often in informants’ homes or public places such as churches, the meeting place (straw hut) of the village, marketplace, at schools on Wednesday afternoons or during the weekends. The location of the interview was based on the informant’s preferences. Interviews were recorded, transcribed verbatim and translated into French by the same researchers that conducted the interviews to ensure consistent interpretations of the raw data. French transcripts were not back-translated to Fon. Relevant French quotes were translated to English.

Participant observation was used to contrast stated opinions with actual behaviour, constituting a respondent-independent data collection tool. Participant observation included observing people's behaviour in their natural environment, as well as informal conversations with participants in the same context. The researchers engaged with local people in informal conversations to build up rapport and trust. These conversations were often spontaneous and occurred as part of the social interaction between the researchers and local people and were not recorded. The research team also observed prenatal consultations, neonatal immunisation sessions in public and private health facilities, practices related to maternal and neonatal health such as baptisms, birth rites and annual community cleansing ceremonies. In public places such as markets, people were not aware of our observations serving research purposes. In settings such as churches, health facilities and ceremonial gatherings, pastors, community leaders, cultural leaders and health facility staff were informed and consented to the observations for research purposes. Notes were taken during the observations, also of other aspects such as non-verbal attitudes. Informal conversations were transcribed into field notes. We also conducted focus group discussions to better understand the sexual and reproductive health practices of adolescent girls and boys. Informants were recruited with the help of school principals, the commune-level artisan leader and the local village chief. The participating adolescents did not necessarily know each other to facilitate spontaneous feedback.

Additional reflexive field notes were kept throughout the research process and included in the analysis in the form of memos.

Data analysis

The researchers collecting the data conducted data analysis simultaneously. In preparation for the research, the PASS (Partners for Applied Social Sciences) health-seeking behaviour model13 was used to design preliminary thematic guides and as an analytical tool during preliminary field visits. The PASS-model was conceived as a hands-on tool to identify why and how people seek care in a specific socio-cultural context. As such, the model builds primarily on social structures and values, worldviews and the health structures that shape the context of health-seeking processes. Open-ended questions were developed to allow for the emergence of unknown factors. In the initial phase of the research, raw data were coded inductively. In a next phase, abductive analysis was employed, where theoretical ideas are iteratively tested in the field until saturation is reached. The qualitative analysis software NVivo 12 was used for data management and analysis. During a workshop where all involved researchers were present, a final coding tree based on the results of the analytical process during the fieldwork was constructed and coding queries were performed to test relationships between codes or between codes and respondent attributes.

Ethical considerations

The study was carried out in accordance with the general ethical principles set out in the Declaration of Helsinki, the American Anthropological Association's Code of Ethics, the American Anthropological Association's Declaration on Ethnography and Institutional Review Boards, all applicable international and local regulations and according to internationally established scientific standards. The ethnographic study protocol was approved by the institutional review boards at ITM Antwerp (Number 1224/18 – 26/02/18) and in Benin (University of Parakou – CLERB-UP; Number 0092 − 18/07/18), followed by the Ministry of Health’s administrative authorisation. Each data collector obtained the informed consent of each participant prior to any interview, focus group discussion or direct observation of a participant, with the exclusion of the observation of groups of people in public spaces. Individual consent was sought from all participants, who were offered the opportunity to withdraw from the study/interview without any consequences for themselves or their families. The goals of the study were explained during the informed consent procedure, and participants were made aware that anonymised data could be used for publications and were given the opportunity to withdraw their consent to participate in the study at any time. The parents of unemancipated minors (adolescents) participating in the study gave their informed consent in their place. Participants were interviewed following written or oral consent. Oral consent, documented by the researcher and a witness, was preferred by community members during data collection because signing one's name when providing information during interviews was seen as a reason for mistrust. A second reason for using an oral consent procedure is the principle of “respondent responsiveness”, referring to the effects that the degree of formality could have on the information provided and on the reliability of responses. Oral consent improved the reliability of the response.

Results

Participant profiles

A total of 83 in-depth interviews, 86 informal interviews, 32 observations and 3 focus group sessions were conducted. During the data collection period, 37 healthcare providers (including 18 biomedical, 10 spiritual and 9 alternative care providers) and 186 community members were interviewed (159 adults and 27 adolescents) as shown in Table 1.

Table 1:

Participant profiles

| Profiles | Total | Male | Female |

|---|---|---|---|

| Healthcare providers | 37 | ||

| Biomedical care (including providers in public, private and religious health facilities) | 18 | 05 | 13 |

| Spiritual care (including key figures in evangelical, Muslim and celestial religions) | 10 | 07 | 03 |

| Alternative care (including bone setters and healers; diviners; and herbal medicine practitioners) | 9 | 9 | 00 |

| Community members | 186 | ||

| Petty trade (sellers of various goods) | 25 | 00 | 25 |

| Agriculture (farmers, plantation workers) | 83 | 21 | 62 |

| Local administration (City Hall Officer; Delegate; community health worker) | 27 | 17 | 10 |

| Public administration (accountant; secretary; teacher) | 22 | 8 | 14 |

| Student | 15 | 7 | 8 |

| Craftspeople (hairdresser; tailor, etc.) | 14 | 02 | 12 |

| Age group | |||

| Adults | 196 | 68 | 128 |

| Adolescents | 27 | 8 | 19 |

| Total | 223 | 76 | 147 |

Perceptions of childbirth

Our informants in southern Benin consider the fetus an ancestor who will be reincarnated at birth. Human life is thus perceived as a cycle of “reincarnation/birth – childhood – adolescence – youth – adulthood – old age – death – reincarnation/birth”. A spiritual dimension of the human being survives death to be reincarnated in another body. This fundamental representation of the life cycle leads to the mobilisation of several care providers along the continuum of care who see human life as a cycle traversed by rites of passage. Interviews with community members show that these perceptions and behaviours are rooted in family, cultural and religious considerations and that every symptom is perceived to have a biomedical and spiritual dimension. Informants moreover report that being able to draw from these different conceptualisations of illness continually renews their hope to overcome potential complications, as several pathways to health can be explored.

Biomedical practices of childbirth

Healthcare providers and facilities

In Allada’s health facilities, our observations show that the biomedical providers who assist women in labour are midwives, nurses, technical health assistants and sometimes gynaecologists and anaesthesiologists. Some biomedical providers report combining their biomedical knowledge and medical protocols with other knowledge systems, which are based on personal experiences, religion, faith, or lessons learned during their careers. Some midwives apply such alternative practices to prevent complications in childbirth, including the use of herbal treatments during the last trimester of pregnancy, and, in the case of breech position, having the woman tie a special loincloth that is supposed to help the foetus assume a cephalic position. There are other midwives who do not use such alternative practices themselves but permit the family of the woman to do so.

“Sometimes […] if a parent-in-law […] comes and brings things and say they want to give her [the woman in labour] herbal tea, at times I let them, I let the parents give, so that tomorrow they can’t tell me that it [potential complications] is because I refused that. So if I see that it's not too much, I accept. If I see that it can't be a problem, I accept it because they know their own practices.” (In-depth interview, midwife)

We have also observed midwives in public health centres providing spiritual care such as praying together with the woman and her family. One midwife in a health centre of the study explained that she could identify women in labour who were very anxious (sometimes because they felt they had a spell on them), which would then trigger her to provide additional care, i.e. staying with them during the entire labour process and praying with them. Informants report that some of the midwives that also operate in the alternative care circuit are known for not referring childbirth complications to other health facilities. They are expected to know how to combine their biomedical training with alternative knowledge to achieve successful childbirth, even when caesarean sections would be advised from a biomedical perspective.

Medical care

In Benin, standard operating procedures for a vaginal birth consist of 13 steps, including welcoming the labouring woman, medical interview and physical examination, additional examinations, labour monitoring, childbirth, cutting the umbilical cord, immediate newborn care including resuscitation if needed, delivery of the placenta, immediate postpartum care, appointment for follow-up, farewell to the women by staff and late postpartum examination.2 Healthcare providers reported during interviews that their biomedical care at health facilities included measuring blood pressure, pulse and temperature; monitoring uterine contractions; checking fetal heart sounds and the progression of fetal presentation and sometimes performing the partograph.

Standard operating procedures after the birth of the child include clamping the cord, an injection of oxytocin and the delivery of the placenta.14 Interviews revealed that after the birth and the cutting of the umbilical cord, the newborn is placed on the mother's belly for a few minutes and then handed over to the medical assistant to be cleaned and dressed. The woman is then kept under observation on the delivery table for a few hours while she massages her own abdomen after being instructed in this by the midwife. Afterwards, the woman is moved to a bed where the staff will give her baby back to her. Breastfeeding is not systematically encouraged in health facilities. Healthcare workers reported that depending on the circumstances of the birth and sometimes at the insistence of the mother, the mother–child pair will be discharged after 12-24 hours. Interviews with community members revealed that postnatal care for mother and baby is often handled by the woman herself or with the support of experienced women in the extended family or in the community.

Informants report that giving birth in a health facility is a formal requirement to be able to formalise the birth of the newborn with a birth certificate, which links the child to the health system. In the health facility, women also receive maternity leave certificates (mother and father), and immediate postpartum care (including referral if needed).

Spiritual care practices to support childbirth

Spiritual care providers

Interviews and observations show that the “Fâ” is an important health provider in the landscape of both spiritual and alternative health in Benin. The “Fâ” acts as an oracle that predicts the future and guides a person’s life with a clear vision from conception to 16 years after death. The Fâ can have more specific visions of important life events and phases, such as marriage and pregnancy,15 and can warn of anticipated successes and failures on a person's path, including complications a person may encounter in his or her life. Guided by the Fâ’s visions, spiritual and alternative care is provided by the Bokonon, an initiate of the Fâ.

In addition to Catholicism and Islam, there are Vodoun religions such as “Dan”, “Egoungoun”, “Thron”, “Sakpata”, “Atchigali”, as well as the worship of the protective deities of each family compound and the graves of deceased ancestors. Spiritual care is administered by the leaders of these religions, which include pastors, priests, imams and practitioners of traditional cults.

Spiritual care practices

Informants explained that in the field of reproductive health, the Bokonon predicts and anticipates the care and sacrifices that must be made for a successful marriage, pregnancy or childbirth. The purpose of childbirth consultations with the Bokonon is to determine the best conditions for the woman to give birth in and to be able to return her to her family without any negative effects. The last consultation at the end of a pregnancy is called “afo djèté Fâ” (afo = foot, djèté = descent, Fâ = future). Ideal childbirth conditions may require therapies directly through the blood (scarification) or orally (herbal teas). Other types of care are prescribed only and are self-administered, such as the use of traditional belts.

Spiritual leaders of the Christian and indigenous religions report to use prayers, psalms and “incantations” to protect the pregnant woman, who is considered vulnerable to spiritual attack. Pregnancy is perceived to weaken the woman's health, which enables passage of malevolent spirits to harm her or her family. According to most religious leaders, the protection provided through family rites and deities is not sufficient for a pregnant woman, hence special religious protection is required during this period. Prayers are also perceived to be psychological care, i.e. pregnant women benefit from prayer sessions in their places of worship because these reduce the woman’s anxiety regarding the complications that may arise during childbirth. Most prayers to support pregnancy and childbirth are done in places which are protected from any perceived moral defilement. In these places, eating, wearing shoes, entering immediately after sex, entering during menstruation and for at least one month after giving birth are prohibited.

Rites and rituals

Women narrated that childbirth is a moment of strong emotions because it is full of uncertainties. To face it, certain rites and rituals are needed to prepare the woman.

The most common ritual is the “Koudio” (kou = death and dio = exchange) which aims at removing the risk of maternal and/or neonatal death that the Bokonon has predicted. The ritual consists of sacrifices to deities or deceased ancestors who accept, after invocation of the Bokonon, to remove this misfortune. The Bokonon gives the pregnant woman a jar containing a herbal infusion with which the woman must purify herself for a certain number of days and in a specific place. This allows her to be “reborn” and not be identified by the malevolent entities that had planned to cause the complications. An alternative healthcare provider explains,

“When pregnant women are approaching their eighth finger [month of pregnancy], we accompany them. We do the ‘koudio’, for us, a woman who is going to give birth, goes to death and comes back to life. We consult the “Fâ” and make all the necessary sacrifices to hear the voice of the child and the mother.” (Informal interview, male traditional therapist)

Objects of power

Our study showed that spiritual care may also include carrying blessed objects or objects of piety. The use of belts or ropes is often recommended by the Bokonon for women in early pregnancy who show signs of potential miscarriage, such as uterine contractions that feel similar to labour. The Bokonon makes a belt and gives it to the couple with instructions on how to use it, including putting it on by the head and taking it off by the feet before birth.

“[…] some women start (uterine) contractions early, they are given a kind of rope, “adogo kan”, which is meant to protect the pregnancy until term. Once full term, if the woman does not remove this rope, she will go into labour for several days but will not give birth naturally.” (In-depth interview, male traditional plant supplier)

Informants report that when a pregnant woman's waters break at home, before going to the hospital, alternative healthcare providers or experienced relatives or friends tie a sandbag to the end of the loincloth the pregnant woman wears around her hip. Until she or her partner unties the knot and the sand drains out, the birth is thought not to be able to take place vaginally.

Within the Christian-inspired celestial religion, pregnancy protection belts are also often used. This belt must go through the same ritual of removal to facilitate childbirth as in the alternative care practices provided by the Bokonon. By separating from the belt, the pregnant woman is again opening the space in which spiritual forces could gather to expel the foetus, which is considered an acceptable risk since the fetus is perceived as fully developed at the time of removal. These belts and other objects of power must be removed before birth.

A spiritual leader informs:

“We make the pregnancy protection belts from the threads of the candles used in our masses and prayers. We tie them together and recite some Bible verses about them before making them available to the faithful who need them. It will be worn by the pregnant woman during pregnancy and removed before delivery.” (In-depth interview, male spiritual care provider)

Some Christian pregnant women reported to wear objects such as the medal of the Virgin Mary or the cross, often with bracelets or beads that carry these medals and are worn around the kidneys. In Christianity-inspired religions, holy water is used, which pregnant women report to pour into their bath water to ward off malevolent spirits. This water is also given to the pregnant woman to drink and pour on her belly for a successful delivery. In the same logic, some women apply holy oil and make the sign of the cross on their belly every time they leave the house, including before leaving the house for the birth.

Alternative practices of care surrounding childbirth

Alternative providers

Interviews with community members and alternative health providers indicate that several types of traditional healers can provide alternative care, as well as elderly relatives (mostly grandmothers and mothers-in-law) and the Bokonon (see above). Herbal medicine is also available on the market and can be directly bought by women and families from specialised herbal medicine sellers.

Herbal medicines

Alternative medicine is generally reported to involve the use of barks, infusions, medicinal leaves and powders made from medicinal leaves. These therapies are usually prepared and provided by the mother-in-law or the Bokonon. The medicinal plant “abiwèlè” is reported to be used to eliminate excess salt in the pregnant woman's body and to lower the weight of the fetus to allow an uncomplicated birth. Herbal products to prepare for childbirth usually begin at the beginning of the third trimester. One woman related her experience:

“I am 49 years old and have six children […]. I go to the maternity ward for the second time [i.e. second contact with the health facility during this pregnancy] […] when I go into labour and after doing my own vaginal exam, I see mucus or blood, I go to the maternity ward. When you are full term, you make an infusion of the medicinal plant (“'kpatin dèhouin” or “abiwèlè” in Fon) and you drink it.” (In-depth interview, female community member and user of public health facility)

Interviews indicate that some medicinal plants prescribed by the Bokonon are intended to induce labour. When the woman is in labour, infusions are available in the community to speed up labour before taking the woman to a health centre.

Community members report that at the health centre, the birth companion usually asks the midwife for permission to visit the woman in labour in the labour room. During these visits, the companions discreetly offer concoctions or herbal products that are meant to speed up labour.

“If the baby can't come out, there are traditional recipes. For my 1st child, the health workers already asked us to take her to Calavi for a Caesarean section, but when my father-in-law came to the scene with a special oil (made from medicinal plants) that we made her drink, a few minutes later my wife gave birth.” (In-depth interview, male community member)

Scarifications

The traditional healer, trained providers and the Bokonon report making scarifications on women’s skin to facilitate labour and childbirth. Scarifications are meant to bring herbal powders in direct contact with the blood of pregnant women who are almost at term. Herbal powders are applied in several strokes of the blade around the woman's hip at term, which is believed to have a faster effect than drinking herbal infusions to prepare for childbirth. The Bokonon can also use or recommend oils extracted from plants to massage on the belly of a woman in labour with active uterine contractions.

Socio-cultural factors explaining the choice of different care providers and practices

Diagnostic uncertainty

Childbirth is considered a time when many invisible “games” by spiritual entities take place, making it difficult to predict the outcome of the event. When a pregnant woman goes into labour, members of the community should not talk about it publicly because it invites supernatural entities into the playing field. Although good biomedical care is considered to take care of many medical complications, such unexpected spiritual events cannot be managed by biomedical care alone. During this phase of uncertainty, alternative and spiritual care is perceived to be needed to cope with and overcome the uncertainty.

Emotional support and kindness

Previous experiences with a welcoming attitude of health facility staff and compassion in times of pain are reported to impact on the pregnant woman’s decision of where to seek care. Women report that the Allada health centre is not frequently used for childbirth because the healthcare workers do not have the welcoming attitude that they experience in the private sector. When a woman is in labour, her suffering is trivialised in the public health centre. A woman recounts the midwife’s words during her last birth:

“are you sure you want to give birth with all this noise? You're still nowhere and you're reacting like this … .” (Informal interview, user of public health facility and a new mother)

To avoid these reactions from health centre staff, some women reported to purposively arrive at the health centre only after their waters had already broken, or at the sight of blood or mucus.

Perceived causality

Alternative healthcare providers often speak of mystical causes for certain symptoms such as unexplained bleeding, very close contractions not followed by a change in cervical dilatation. In these cases, some biomedical providers use skills such as prayer to avoid a negative outcome. One informant reveals an experience during a delivery:

“[…] the woman in labour […] is set up in the labour room. She called us and informed us that, as if in a dream, she saw a woman who had just placed a calabash in a corner of the room. We prayed with her […] it seems that there is an old woman in their house who is the cause [of the complication] and that the companions have returned to threaten her. Subsequently, the woman gave birth without complications.” (Informal interview, female health provider)

Shame and social exclusion

Because alternative care practices are not always welcomed at the clinic, women often do not admit to having received other types of care before coming to the clinic. Sometimes alternative therapies are administered discreetly at the health centre by family members to speed up the work. These practices are considered “evil” by some health workers, which has a negative impact on the care the woman receives from these workers.

In this community, it is considered shameful when a woman who gives birth without medical complications remains in a health centre for more than 72 hours. This indicates the inability of the household to pay the medical costs of the delivery (and the woman is effectively imprisoned until the costs are paid). It is also considered shameful when the delivery is done at home and is unsuccessful, which will lead to the entire household being criticised.

“I know a woman who had a bad experience during her home birth and the child died on the spot. After this event, she left the area to join her parents in another department.” (Informal interview, female community member)

Structural factors explaining the choice of different care providers and practices

Affordability of care

Biomedical care is more expensive than alternative and spiritual care during childbirth because of the cost of various prescribed medicines, travel costs and the medical costs of childbirth. While some prescribed medical products are often available at the health facility's pharmacy, many prescriptions require multiple trips that result in additional expenses at private pharmacies. Most households in the study area report to have low incomes and are unable to cover the excessive costs of health care. The inability to pay for childbirth in public health facilities, in addition to the imprisonment of women, is also sanctioned by the retention of the birth certificate. This document is essential because it identifies the child by legal name, citizenship and parentage, and gives the child access to national examinations and education certificates in later life.

“When I gave birth at the health facility, I was kept for four days. The four days were due to the fact that my husband was not able to pay the eight (8,000 FCFA – approximately US$13) bills that were sent to us after the delivery.” (In-depth interview, female community member)

The popular alternative offered by private health facilities is to pay in instalments in case of financial difficulties. Traditional and spiritual care is usually available nearby and inexpensive, or payment is left to the discretion of the users. Therapies used for alternative and/or spiritual care are also often within reach: some family members can provide this care themselves; holy books need only be purchased once and many medicinal plant leaves can be collected from around the village.

Accessibility of care

In the Allada-Toffo-zè health zone, not all roads are passable in all seasons. Nevertheless, communities find ways to move women in childbirth, using tricycles, motorcycles or on foot. Ambulances were rarely reported as a means of transportation, even in the case of complications, due to the operational status and cost of the service. The convenience of having alternative and spiritual care providers within the community, quickly reachable by a message carried either by a child in the community or by a phone call, is very attractive to community members because they can move quickly to assist the woman in labour.

Unidirectional communication

Community members indicate that there is a lack of communication about the value of care during pregnancy, childbirth and even afterwards provided by healthcare providers in public health facilities. The relationship between biomedical caregivers and pregnant women during labour and delivery is perceived as unbalanced. Many health professionals we interviewed consider their practices to be the best and reject other forms of care. This leads to the development of hide-and-seek games that are not beneficial to either party.

“These are things they do in secret. When they come in and you set them up […], the parents, often the husband comes in and asks for a few minutes to see or talk to his wife […]. Once I caught a man with a calabash in his hand in the delivery room who at the sight of me dropped the calabash [… .]. The fact that the calabash fell could complicate the woman's delivery [as it should not close, it should remain open to the sky].” (Informal interview, female healthcare provider)

The woman in labour is thought to be vulnerable, has little to say and often finds herself in between several actors (husband or partner and healthcare providers). Women report to be struggling especially when they are caught in the crossfire between the biomedically compliant midwife opposing the use of herbal recipes, and the alternative or spiritual provider continually warning her that not using the products recommended to her would lead to complications, such as the need for a caesarean section or the death of the newborn or the woman, and would also take away the social benefits of the integration rites that the mother and newborn need to be (re)settled as members of the community.

Alternative and spiritual providers are actors that the pregnant woman encounters almost every day because they live in her community, or she meets them on days of worship. Women report that the proximity, cohabitation and frequency of contact makes such health communication more effective. Similarly, pregnant women report to prefer the way communication is managed by some private health centres. They receive appointment reminders by telephone 72 and 48 hours before the consultation date. In private health facilities, they most often stay with the same provider, who can build trust and obtain more details about the non-biomedical care received by pregnant women through repeated contact.

Discussion

The results of this study show that both socio-cultural and structural factors explain the combined use of biomedical and non-biomedical childbirth practices and care providers in Southern Benin. Understanding why women do or do not comply with the biomedical guidelines for pregnancies and childbirth in Benin must also be linked with an understanding of how local communities for whom such guidelines and policies are in place perceive childbirth. Our study shows that women’s decisions on what care to seek, and at what point in the birthing process, are driven by their perceptions of risk and the multidimensionality of a perceived successful birth. Several types of care and multiple social actors are needed in a woman’s reproductive life to cover the biomedical, spiritual and social dimensions of childbirth. These dimensions of childbirth interact with external barriers limiting access to quality health care, including geographic access and financial means as shown by other studies in Benin and other sub-Saharan countries.16,17

Non-medical dimensions of childbirth

Previous studies have described how non-medical factors shape many of the practices surrounding childbirth in Sub-Saharan Africa, from both a patient and a health provider perspective.18–21 Alternative childbirth and labour practices to the biomedical protocol have also been identified all around the world.22,23 In Benin, we identified practices such as prayer, scarifications, divination and herbal medicines to tackle the social, spiritual and biological forces at play in “the battle” of childbirth. This is similar to how de Sardan describes childbirth in rural Niger.24 Although such alternative practices are often hidden from healthcare workers, they serve to ensure healthcare worker attention upon arrival at the health centre. Some of our informants used non-biomedical interventions (spiritual objects, herbal concoctions, alternative care) to induce physical effects such as blood or mucus before going to a health centre, which would force healthcare workers to take care of them. However, blood and mucus may represent a medical emergency and therefore this can be considered an important delay to seeking timely and effective biomedical care in case of complications. This could be one of the factors explaining the high maternal mortality rates in Benin despite the high use of facility-based childbirth. We have described the late arrival of women in the maternity ward as a potential risk factor for unnecessary complications before.11 Schantz et al. confirm this trend and add that these complications may further lead to “emotional exhaustion” for the health provider, ultimately reducing the quality of care they can deliver.21

Healthcare worker behaviour

Other studies have also found that women's reasons for not attending maternal health services include dissatisfaction with poor behaviour of health workers,25–29 long waiting times,29 lack of medical equipment, costs and bribes paid to medical staff for medical care received.2,6,21,30,31 Moreover, apprehensions about the pain of childbirth, the health of the unborn baby, unexpected complications and their own mental capacity to cope with the ordeal were found to generate anxiety in labouring women, which requires effective communication from healthcare providers.21,32 We were not able to observe women in the maternity ward or delivery room to assess the immediate medical and non-medical healthcare worker responses to this anxiety; however, another study which did observe women in an urban hospital in Benin suggests that health providers try to overcome this anxiety with medical interventions that may not be medically warranted, such as caesarean sections.21 Our study shows, however, that in Allada healthcare workers can effectively alleviate anxiety by integrating alternative practices such as prayers and continued presence during labour into their medical care services.

Integrating community perspectives in maternal health policies

In a number of African countries, there have been several approaches and policies to improve community-based health care for childbirth with varying successes.33–36 In Namibia, maternity homes have been built33 to bring women closer to health facilities and reduce maternal mortality, and have been shown to increase health facility-based childbirth and to reduce complications during pregnancy, birth and the immediate postpartum.33 In Kenya, a successful policy to improve health care around childbirth involved traditional birth attendants, who now sensitise and refer pregnant women to formal health facilities.34 Several initiatives have also been taken by the Beninese government to bring biomedical care, including childbirth, closer to its users. The first strategy in 2006 was the provision of emergency obstetric kits to public health facilities35; the second is the health equity fund to pay for care for the poor; and since 2008, Benin has made caesarean sections free.30,35 These initiatives have resulted in high rates of facility-based childbirth in the Atlantic department – 97.7% in the 2017–2018 Demographic and Health Survey1 – but have been less effective in reducing maternal mortality rates. Schantz et al describe how the suboptimal implementation of the free caesarean section policy in Benin has driven an overuse of caesarean sections as a response to maternal distress and fear of childbirth.21 As other studies8,24 in Africa have shown, these biomedically oriented initiatives do not always consider the spiritual and other non-biomedical needs of pregnant women and their families. Although local communities have integrated different conceptual frameworks into their own continuum of care, the biomedical guidelines and policies on which public health service delivery is based lack this integration, reducing its popularity and limiting its consistent use in the formal care continuum. We have shown in this study that quality care during childbirth from the perspective of Fon community members is considered multidimensional, which does not correspond to the unidimensional medical protocol that midwives and other health workers in public health facilities have to work with. To increase the perceived quality and utilisation of public health care, we suggest broadening the biomedical perspective on care by integrating locally specific non-harmful alternative practices that help women and their families feel at ease during labour and childbirth.

Strengths and limitations of the study

This study provided a better understanding of the practices and perceptions surrounding the late use of care during childbirth. The 12-month ethnographic immersion was conducted by Beninese researchers to better understand healthcare utilisation along the continuum. However, we were not able to observe the pregnant women in labour and thus accurately describe the words, potions, prayers and recipes used at home and in the delivery room. Some participant characteristics such as religion and education level were not systematically collected for all informants.

Conclusion

Our study suggests that in Southern Benin, childbirth is a physical, social and a spiritual process. All processes must be integrated into care to achieve a perceived successful birth. The mother and her newborn are perceived to need spiritual and social (re)integration rites as well as to receive quality medical care to prevent medical, social and spiritual complications. Despite medically adequate protocols of care, the skilled staff at health facilities are struggling to significantly reduce the maternal mortality rate. Our study suggests that although most women reach and give birth at a health facility, they often arrive late in labour because certain alternative and spiritual practices are likely to precede their departure to the health facility. This trend potentially contributes to the high maternal mortality rates documented in Benin. Maternal health policies should take this into account and identify practices during childbirth that are not harmful to the mother or child, such as prayers and the application of safe products (olive oil, holy water, etc.) to increase the acceptability of maternal health care offered at health facilities.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr Sourou Béatrice Goufodji Keke for facilitating the fieldwork and supporting the study as retiring director of CERRHUD. We would also like to thank all the participants in the study villages, the health centres, markets, pharmacies and hospitals, as well as in the alternative and spiritual care settings, for their willingness to talk to us about at times sensitive subject matter and invite us to stay in their homes and/or workplaces.

Funding Statement

The study was funded by the Belgian Directorate-General for Development Cooperation. The funder had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, interpretation of the data or writing the manuscript.

Authors’ contributions

CG and TD conceptualised and designed the study. Ethnographic fieldwork was carried out by AV, CB, JPD, LK and supervised through intermittent field visits by CG and TD. Data analysis was carried out jointly by AV, CB, JPD, LK, CG, TD, LB. AV, JPD and CG wrote the preliminary manuscript, after which all authors read, contributed to and approved the final manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- 1.Institut National de la Statistique et de l’Analyse Economique (INSAE) et ICF . Bénin, Enquête Démographique et de Santé 2017-2018. Cotonou, Bénin et Rockville, MD; 2019.

- 2.Organisation mondiale de la Santé . Standards pour l’amélioration de la Qualité des soins maternels et néonatals dans les établissements de santé. Genève: Organisation mondiale de la Santé; 2017. 84 p. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kerber KJ, de Graft-Johnson JE, Bhutta ZA, et al. . Continuum of care for maternal, newborn, and child health: from slogan to service delivery. Lancet. 2007;370(9595):1358–1369. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61578-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baxerres C, Egrot M, Duquenois S, et al. . La biomédicalisation de la grossesse au Bénin s ‘accompagne-t-elle d’un processus de marchandisation ? In: Farnarier C, editor. L’innovation en santé : technologies, organisations, changements. Rennes: Presses Universitaires de Rennes; 2018. p. 171–188. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Présidence de la République du Bénin . Décret 2008-730 portant institution de la gratuité de la césarienne au Bénin. Cotonou, Benin; 2008.

- 6.Kifle D, Azale T, Gelaw YA, et al. . Maternal health care service seeking behaviors and associated factors among women in rural Haramaya District, Eastern Ethiopia: a triangulated community-based cross-sectional study. Reprod Health. 2017;14(1):6. doi: 10.1186/s12978-016-0270-5. PMID: 28086926; PMCID: PMC5237279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Babalola S, Fatusi A.. Determinants of use of maternal health services in Nigeria - looking beyond individual and household factors. BMC Pregn Childbirth. 2009;9(1):43. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-9-43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dossou JP, Vigan A, Boyi C, et al. Utilisation des services de santé reproductive le long du continuum de soins au Bénin: une exploration qualitative. Cotonou, Benin; 2020.

- 9.Tunçalp Ö, Were W, MacLennan C, et al. . Quality of care for pregnant women and newborns—the WHO vision. BJOG. 2015;122(8):1045–1049. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.13451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de la Santé M. Annuaire des statistiques sanitaires 2017. Cotonou, Benin; 2018.

- 11.Gryseels C, Dossou J, Vigan A, et al. Where and why do we lose women from the continuum of care in maternal health? A mixed-methods study in Southern Benin. Tropical Medicine & International Health [Internet]. 2022 Feb 9. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111tmi.13729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Institut National de la Statistique et de l’Analyse Economique . Cahier des villages et quartiers de ville du Département de l’Atlantique. Cotonou, Benin; 2016.

- 13.Hausmann Muela S, Muela Ribera J, Toomer E, et al. . The PASS-model: a model for guiding health-seeking behavior and access to care research. Malaria Rep. 2012;2(e3):17–23. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Saizonou J, Godin I, Ouendo EM, et al. . La qualite de prise en charge des urgences obstetricales dans les maternites de reference au Benin: Le point de vue des et leurs attentes. Trop Med Internat Health. 2006;11(5):672–680. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2006.01602.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hounkposso B. Le fâ est une lumière des hommes qui tire sa source du grand nom divin. Quotidien la Nation. Available from: https://www.ouvertures.net/benin-le-fa-est-une-lumiere-des-hommes-qui-tire-sa-source-du-grand-nom-divin/.

- 16.Tanou M, Kishida T, Kamiya Y.. The effects of geographical accessibility to health facilities on antenatal care and delivery services utilization in Benin: a cross-sectional study. Reprod Health. 2021;18(1):205. doi: 10.1186/s12978-021-01249-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bobo FT, Asante A, Woldie M, et al. . Spatial patterns and inequalities in skilled birth attendance and caesarean delivery in sub-Saharan Africa. BMJ Glob Health. 2021;6(10):e007074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jaffré Y, Lange IL.. Being a midwife in West Africa: between sensory experiences, moral standards, socio-technical violence and affective constraints. Soc Sci Med. 2021;276:113842. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.113842 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Quagliariello C. Birth models in and between Italy and Senegal: a cross-cultural inquiry on the risks related to childbirth and birth technologies. Health Risk Soc. 2019;21(3–4):207–225. doi: 10.1080/13698575.2019.1640352 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jaffré Y, Suh S. Where the lay and the technical meet: Using an anthropology of interfaces to explain persistent reproductive health disparities in West Africa. Soc Sci Med. 2016;156:175–183. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.03.036. Epub 2016 Mar 28. PMID: 27043370 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schantz C, Aboubakar M, Traoré AB, et al. . Caesarean section in Benin and Mali: increased recourse to technology due to suffering and under-resourced facilities. Reprod Biomed Soc Online. 2020;10:10–18. doi: 10.1016/j.rbms.2019.12.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Policella M. De l’Afrique à la France: la maternité déracinée. France: Université de Caen Normandie; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bartoli L. Venir au monde: les rites de l’enfantement sur les cinq continents. Paris: Petite Bibliothèque Payot; 2007. 288 p. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Olivier de Sardan J, Moumouni A, Souley A.. ‘L’accouchement c’est la guerre’- De quelques problèmes liés à l’accouchement en milieu rural nigérien. Bulletin de l’APAD. 1999;17;1–24. doi: 10.4000/apad.483 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McMahon SA, George AS, Chebet JJ, et al. . Experiences of and responses to disrespectful maternity care and abuse during childbirth; a qualitative study with women and men in Morogoro Region, Tanzania. BMC Pregnan Childbirth. 2014;14:268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Abuya T, Warren CE, Miller N, et al. . Evolution of the perlecan/HSPG2 gene and its activation in regenerating nematostella vectensis. PLoS One. 2015;10(4):e0124578. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0124578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wesson J, Hamunime N, Viadro C, et al. . Provider and client perspectives on maternity care in Namibia: results from two cross-sectional studies. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2018;18(1):363. doi: 10.1186/s12884-018-1999-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Warren N, Beebe M, Chase RP, et al. . Nègènègèn: sweet talk, disrespect, and abuse among rural auxiliary midwives in Mali. Midwifery. 2015;31(11):1073–1080. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2015.07.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gong E, Dula J, Alberto C, et al. . Client experiences with antenatal care waiting times in southern Mozambique. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19(1):538, doi: 10.1186/s12913-019-4369-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lange IL, Kanhonou L, Goufodji S, et al. . The costs of ‘free’: experiences of facility-based childbirth after Benin’s caesarean section exemption policy. Soc Sci Med. 2016;168:53–62. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.09.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moungbakou IBM. Commodification of care and its effects on maternal health in the Noun division (West Region – Cameroon). BMC Med Ethics. 2018;19(S1):43. doi: 10.1186/s12910-018-0286-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Obossou AAA, Salifou K, Aboubakar M, et al. . Vécu psychologique De La parturiente En salle d’accouchement À La maternité Du centre hospitalier départemental Et universitaire Du borgou À parakou (BENIN). European Sci J. 2017;13(21):407. doi: 10.19044/esj.2017.v13n21p407 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Organisation Mondiale de la Santé . Des maisons de maternité en Namibie pour protéger les nouveau-nés et leur mère [Internet]. Centre des Médias de l’Organisation Mondiale de la Santé; 2016. Available from: https://www.who.int/fr/news-room/feature-stories/detail/namibia-maternity-waiting-homes-protect-newborns-and-mothers.

- 34.Tomedi A, Stroud SR, Maya TR, et al. . From home deliveries to health care facilities: establishing a traditional birth attendant referral program in Kenya. J Health Popul Nutr. 2015;33(1):6. doi: 10.1186/s41043-015-0023-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Centre de Recherche en Reproduction Humaine et en Démographie . Rapport de synthèse: l’évaluation de la politique de gratuité de la césarienne dans cinq zones sanitaires au Bénin. FEMHealth. Cotonou: University of Aberdeen; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Omer K, Joga A, Dutse U, et al. . Impact of universal home visits on child health in Bauchi State, Nigeria: a stepped wedge cluster randomised controlled trial. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021;21(1):1085. doi: 10.1186/s12913-021-07000-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]