Abstract

Background:

Patients with hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) may have a higher risk of coronary artery disease (CAD) due to the excessive inflammatory burden. However, data on this association is still relatively limited.

Aims:

To investigate the association between HS and risk of prevalent and incident CAD by combining result from all available studies using systematic review and meta-analysis technique.

Materials and Methods:

Potentially eligible studies were identified from Medline and EMBASE databases from inception to November 2021 using search strategy that comprised of terms for 'hidradenitis suppurativa' (HS) and 'coronary artery disease' (CAD). Eligible study must be cohort study that consisted of one cohort of patients with HS and another cohort of individuals without HS. The study must report incidence or prevalence of CAD in both groups. The retrieved point estimates with standard errors from each study were summarized into pooled result using random-effect model and generic inverse variance method. Meta-analyses of the prevalent and incident CAD were conducted separately.

Results:

A total of 876 articles were identified. After two rounds of independent review by three investigators, seven cohort studies (four incident studies and three prevalent studies) met the eligibility criteria and were analysed in the meta-analyses. The meta-analysis found a significantly elevated risk of both incident and prevalent CAD in patients with HS compared to individuals without psoriasis with the pooled risk ratio of 1.38 (95% CI, 1.21–1.58; I2 83%) and 1.70 (95% CI, 1.13–2.57; I2 89%), respectively.

Limitations:

Limited accuracy of diagnosis of HS and CSD as most included studies relied on diagnostic codes and high between-study statistical heterogeneity.

Conclusions:

The current systematic review and meta-analysis found a significantly increased risk of both prevalent and incident CAD among patients with HS.

Key Words: Coronary artery disease, hidradenitis suppurativa, meta-analysis

Introduction

The causative role of chronic inflammation in the development of premature atherosclerosis is well-recognized.[1,2] Several studies have demonstrated the deleterious effects of inflammatory cytokine, reactive oxygen species and activated leukocytes on endothelial function, resulting in the initiation and progression of atherosclerotic plaque.[3,4,5,6] Both in vivo and in vitro studies have demonstrated hypercoagulable state associated with chronic inflammation as a result of activated coagulation cascade as well as impaired anti-coagulation pathway and fibrinolysis.[7,8] These factors may serve as the foundation of the development of significant compromised coronary arterial blood flow and clinically evident coronary artery disease (CAD). Moreover, an increased incidence and prevalence of CAD among patients with inflammatory disorders, such as rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis and systemic lupus erythematosus and polymyalgia rheumatica, have been reported.[9,10,11,12,13]

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a chronic skin disorder characterized by recurrent inflammation of the pilosebaceous unit. HS usually presents as inflammatory nodules in intertriginous areas that can progress to abscesses, fistula, scarring and contractures.[14] It is a relatively common disease with the reported prevalence of approximately 0.1% with female to male ratio of 2:1.[15]

Due to the higher inflammatory burden, patients with HS may also carry a higher risk of CAD similar to other chronic inflammatory disorders. The current systematic review and meta-analysis aim to comprehensively review and summarize the results of all available studies that compare the incidence and prevalence of CAD among patients with HS versus individual without HS.

Materials and Methods

Search strategy

Published studies indexed in Medline and EMBASE database from inception to November 2021 were independently reviewed by two investigators (T.C. and P.W.). Search strategy was developed using terms associated with HS and CADs. The search strategy is described in detail in Supplemental Material 1. No language restriction was applied.

Inclusion criteria

Eligible study must be cohort study that consisted of one cohort of patients with HS and another cohort of individuals without HS. The study must report incidence or prevalence of CAD in both groups. Alternatively, the study may report relative risk (RR), hazard risk ratio (HR), standardized incidence ratio (SIR) or incidence rate ratio (IRR) with associated 95% confidence interval (CI) comparing the incidence or prevalence of CAD between the two groups.

The same two investigators independently reviewed each retrieved study for its eligibility. Difference in the determination of study eligibility was resolved by discussion with the senior investigator (P.U.). The quality of studies that reported incident CAD was assessed by two investigators (P.U. and P.W.) using the Newcastle-Ottawa quality assessment scale for cohort study.[16]

Data extraction

A standardized data collection form was utilized for extraction of the following data from each included study: last name of the first author, country where the study was conducted, year (s) of study, publication year, number of participants, recruitment of participants, diagnosis of HS, diagnosis of CAD, average follow-up duration (for incident study), mean age of participants, percentage of female participants, comorbidities of participants and variables that were adjusted in multivariate analysis.

Statistical analysis

Review Manager 5.3 software from the Cochrane Collaboration was used for all of the analyses. Point estimates with standard errors were extracted from each study and were combined to calculate pooled effect estimates using the generic inverse variance method as described by DerSimonian and Laird.[17] Random-effect model, instead of fixed-effect model, was used as the underlying assumption of fixed-effect model that every study should yield the same effect estimate is almost always not true for meta-analysis of observational study. Meta-analyses of the prevalent and incident CAD were conducted separately. Cochran's Q test and I2 statistic were used to assess between-study heterogeneity. A value of I2 of 0–25% represents insignificant heterogeneity, 26–50% low heterogeneity, 51–75% moderate heterogeneity and >75% high heterogeneity.[18] We planned to create funnel plot to assess for the presence of publication bias if there were enough eligible studies.

Results

Search results

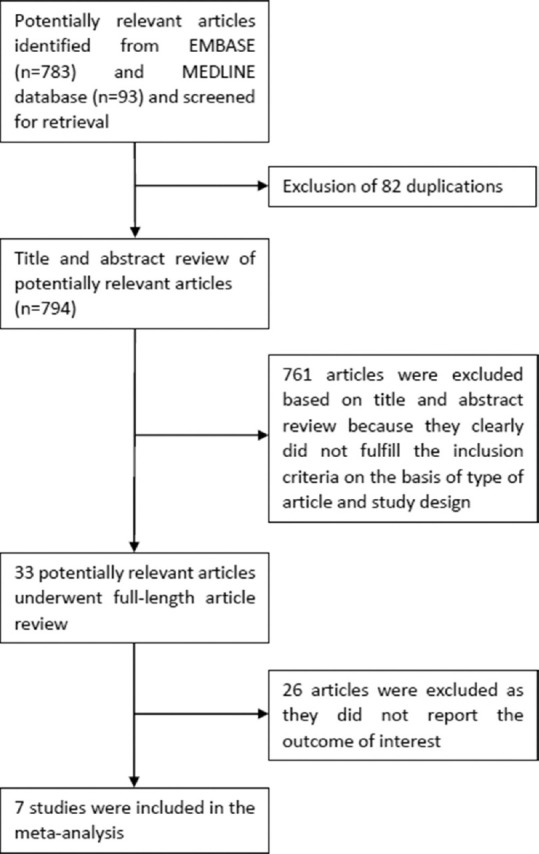

A total of 876 articles were retrieved from EMBASE and Medline database using the aforementioned search strategy. There were 82 duplicated articles between the two databases which were eliminated, leaving 794 articles for title and abstract review. At this stage, 761 articles were eliminated as they obviously did not meet the eligibility criteria based on study design and type of article. This left a total of 33 articles for the full-length article review. After full-length review, 26 articles were further eliminated as they did not report the outcome of interest. Finally, seven cohort studies (four incident studies[19,20,21,22] and three prevalent studies[23,24,25]) met the eligibility criteria and were analysed in the meta-analyses. Figure 1 demonstrates the systematic review process of this study. Tables 1 and 2 describe the methodology and baseline characteristics of the included cohort studies for incident and prevalent meta-analysis, respectively.

Figure 1.

Study identification and literature review process

Table 1.

Main characteristics of the cohort studies included in the meta-analysis of incident CAD in hidradenitis suppurativa

| Egeberg et al.[19] | Andersen et al.[22] | Hung et al.[20] | Reddy et al.[21] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | Denmark | Denmark | Taiwan | United States |

| Study design | Retrospective cohort | Retrospective cohort | Retrospective cohort | Retrospective cohort |

| Year of publication | 2016 | 2020 | 2019 | 2020 |

| Total number of participants | Cases with HS: 5,964 Comparators without HS: 29,404 | Cases with HS: 14,488 Comparators without HS: N/A | Cases with HS: 478 Comparators without HS: 1,912 | Cases with HS: 49,862 Comparators without HS: 1,421,223 |

| Recruitment of participants | Patients with HS were identified from the Danish National Patient Registry database from January 1st, 1997 to December 31st, 2011. This database covers all citizens of Denmark. Comparators without HS were randomly selected from the same database at 1:5 ratio. They were sex, age and calendar time matched to cases. Participants with diagnosis of MI or stroke prior to the study were excluded. | Patients with HS and comparators were identified from the Danish National Patient Registry from January 1st, 1994 to April 10th, 2018 The rest of the residents of Denmark without HS served as comparators. | Patients with HS and comparators were identified from the longitudinal health insurance database of Taiwan from 2000 to 2013. The longitudinal health insurance database is a subset of the Taiwan National Health Insurance Research database which covers inpatient and outpatient care of almost all residents of Taiwan. Comparators without HS were randomly selected from the same database at 1:4 ratio. They were sex, age and calendar time matched to cases. Participants with diagnosis of MI or stroke before 2000 were excluded. | Patients with HS were identified from the Explorys database which encompassed 27 integrated healthcare organization of over 56 million unique patients from January 1, 1999, and April 1, 2019. Comparators without HS were all other patients in the database who did not have diagnosis codes for HS. |

| Diagnosis of HS | Presence of ICD-8-CM (705.91) or ICD-10-CM (L73.2) for HS in the database | Presence of ICD-10-CM (L73.2) diagnosis code for HS in the database or the presence of ICD-10-CM surgical procedural codes for procedures likely for HS at least twice within a 6-month period | Presence of ICD-9-CM (705.83) made by dermatologist at least four times | Presence of at least 1 ICD-9-CM (705.83) or ICD-10-CM (L73.2) for HS in the database |

| Diagnosis of CAD | Presence of ICD-10-CM (I21-I22) for MI in the database | Presence of ICD-10 codes (I21, I210, I210A, I210B, I211, I211A, I211B, I212, I213, I214, I219) for acute MI in the database | Presence of ICD-9-CM (411-414) for CAD in the database | Presence of ICD-9 code (410.x) or ICD-10 code (I21. x-I22.x) for MI in the database |

| Follow-up | Until migration, death or occurrence of the end point of interest | Until migration, death or occurrence of the end point of interest | Until migration, occurrence of the end point of interest or the end of 2013 | Until the date of last database encounter or occurrence of the end point of interest |

| Average duration of follow-up (years) | Mean: 7.1 | Median: 8.8 | Mean for cases with HS: 10.7 Mean for comparators without HS: 11.8 | Mean for cases with HS: 4.2 Mean for comparators without HS: 8.2 |

| Average age of participants (years) | Cases with HS: 37.7 Comparators without HS: 37.6 | Cases with HS: 37.6 Comparator without HS: N/A | Cases with HS: 39.8 Comparators without HS: 40.0 | Cases with HS: 38.3 Comparators without HS: 44.7 |

| Percentage of female | Cases with HS: 72.9 Comparators without HS: 73.1 | Cases with HS: 68.3 Comparator without HS: N/A | Cases with HS: 51.7% Comparators without HS: 51.7% | Cases with HS: 76.2% Comparators without HS: 58% |

| Comorbidities | Cases with HS: Alcohol abuse: 3.3% Arrhythmia: 0.6% DM: 4.3% Depression: 1.2% HTN: 5.6% IBD: 0.8% VTE: 0.8% Comparators without HS: Alcohol abuse: 1.3% Arrhythmia: 0.4% DM: 1.4% Depression: 0.4% HTN: 2.8% IBD: 0.3% VTE: 0.3% | N/A | N/A | Cases with HS: Smoking status: 48.2% HTN: 27.1% Hyperlipidemia: 20.8% DM: 12.5% CCI score 0.6 Comparators without HS: Smoking status: 26.2% HTN: 7.4% Hyperlipidemia: 5% DM: 2.7% CCI score 0.1 |

| Variables adjusted in multivariate analysis | Age, sex, smoking, comorbidities, medication and socioeconomic status | N/A | Age, sex, CCI, alcoholism, obesity and residence/regions | Age, sex, race, HTN hyperlipidemia, DM, smoking status, BMI, CCI score and baseline medication use |

| Newcastle-Ottawa score | Selection: 4 Comparability: 2 Outcome: 3 | Selection: 3 Comparability: 0 Outcome: 3 | Selection: 4 Comparability: 2 Outcome: 3 | Selection: 4 Comparability: 1 Outcome: 3 |

CAD=Coronary artery disease, CCI=Charlson comorbidity index, DM=Diabetes mellitus, HS=Hidradenitis suppurativa, HTN=Hypertension, IBD=Inflammatory bowel disease, ICD=International classification of diseases, MI=Myocardial infarction, N/A=not available, VTE=Venous thromboembolism

Table 2.

Main characteristics of the cohort studies included in the meta-analysis of prevalent CAD in hidradenitis suppurative

| Miller et al.[23] | Ward et al.[24] | Hua et al.[25] | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Country | Denmark | United States | United States |

| Study design | Retrospective cohort | Retrospective cohort | Retrospective cohort |

| Year of publication | 2018 | 2019 | 2021 |

| Total number of participants | Patients with TB: 2,283 Comparators: 6,849 | Patient with HS: 5,046 Comparators: 25,827 | Patient with HS: 13,667 Comparators: 136,670 |

| Recruitment of participants | Patients with HS were identified from the database of the General Suburban Population Study (GESUS) Comparators without HS were the rest of the participants of the survey who did not have HS | Patients with HS were identified from the database of the Duke University Medical Center Comparators without HS were randomly selected from the same database | Patients with HS were identified from the Clinformatics Data Mart database which contained health information of 77 million patients with commercially insured and Medicare coverage from 2003 to June 2019 Comparators without HS were randomly selected from the same database at 1:10 ratio. They were sex, age and race matched to cases. |

| Diagnosis of HS | Self-reported through health questionnaire | Presence of ICD codes for HS in the database | Presence of ICD codes for HS in the database at least twice |

| Diagnosis of CAD | Self-reported through health questionnaire | Presence of ICD codes for CAD in the database | Presence of ICD codes for MI in the database |

| Average age of participants (years) | NA | N/A | Cases with HS: 40.7 Comparator without HS: 40.7 |

| Percentage of female | NA | N/A | Cases with HS: 73.6 Comparator without HS: 73.6 |

| Variables adjusted in multivariate analysis | Age, sex, smoking and metabolic syndrome | Obesity, HTN, hyperlipidemia, renal disease, VTE, metabolic syndrome and DM | Obesity and smoking |

CAD=Coronary artery disease, DM=Diabetes mellitus, HS=Hidradenitis suppurativa, HTN=Hypertension, ICD=International classification of diseases, MI=Myocardial infarction, N/A=not available, VTE=Venous thromboembolism

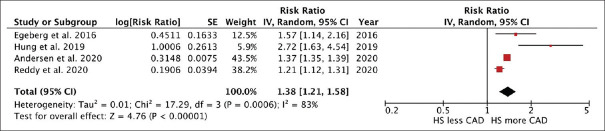

Risk of incident coronary artery disease in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa

The meta-analysis found a significantly elevated risk of incident CAD in patients with HS compared to individuals without HS with the pooled risk ratio of 1.38 (95% CI, 1.21–1.58). This meta-analysis had high statistical heterogeneity with I2 of 83% [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

Forest plot of the meta-analysis of risk of incident coronary artery disease in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa

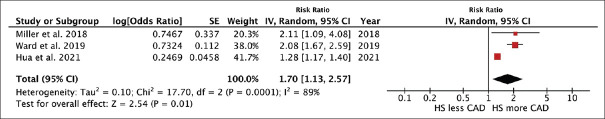

Risk of prevalent coronary artery disease in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa

The meta-analysis found a significantly elevated risk of prevalent CAD in patients with HS compared to individuals without HS with the pooled risk ratio of 1.70 (95% CI, 1.13–2.57). This meta-analysis had high statistical heterogeneity with I2 of 89% [Figure 3].

Figure 3.

Forest plot of the meta-analysis of risk of prevalent coronary artery disease in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa

Evaluation for publication bias

Funnel plot for assessment of publication bias was not created due to the limited number of eligible studies for both meta-analyses.

Discussion

The current systematic review and meta-analysis summarizes data from seven studies, involving over 80,000 patients with HS. There was a significantly increased risk of both incident and prevalent CAD among patients with HS compared with individuals without HS. All included studies reported a positive association between HS and CAD, but the risk estimates varied considerably, ranging from 1.3 to 2.7-fold increase.

Premature atherosclerosis as a result of excessive inflammatory burden is probably the main pathogenesis behind the increased risk of CAD among patients with HS.[7,8] Studies have demonstrated that inflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin-1 and tumour necrosis factor, can induce the expression of vascular adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1) in endothelial cells, which could promote adhesion and invasion of monocytes to vascular endothelium and tunica intima.[2,26] Subsequently, those monocytes would internalize and oxidize lipoprotein particle, initiating the process of lipid deposition and plaque formation in the arterial wall. Chronic inflammation also weakens atherosclerotic plaque through the activated leukocytes and increased production of enzymes that could degrade extracellular matrix constituents such as matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs).[27] This would make the plaque more vulnerable to rupture and, thus, increased risk of acute myocardial infarction. Furthermore, chronic inflammation is known to induce hypercoagulable state through activated coagulation cascade and compromised fibrinolytic pathway.[7,8]

The second explanation is related to shared risk factors between HS and CAD. Smoking and obesity are ones of the most important non-genetic risk factors of HS.[14,28] The role of smoking and obesity in the pathogenesis of CAD is well-established.[29]

Glucocorticoids, a commonly used medication for the management of HS may also serve as a contributing factor to the increased cardiovascular disease risk as their long-term exposure is associated with several predisposing factors for coronary heart disease, such as diabetes mellitus, hypertension and dyslipidemia.[30]

This study has some limitations, and therefore, the pooled results should be interpreted with caution. First, most of the included studies were conducted using administrative database.

Diagnoses of HS and CAD were made based on the presence of diagnostic codes with no further verification which would jeopardize the accuracy of the identification of cases and event of interest. Second, the between-study heterogeneity was high in both meta-analyses which is likely caused by different methodology and background population. Third, the possibility of publication bias could not be assessed due to small numbers of available studies. Therefore, publication bias in favour of studies that showed positive association may have been present.

Conclusion

In summary, the current systematic review and meta-analysis found a significantly increased risk of both prevalent and incident CAD among patients with HS.

Financial support and sponsorship

We did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the commercial, public or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of interest

We do not have any financial or nonfinancial potential conflict of interest.

Supplementary material available online

Supplemental Material 1 – Searching strategy

EMBASE Database

'suppurative hidradenitis'/exp OR 'suppurative hidradenitis'

'hidradenitis suppurativa'/exp OR 'hidradenitis suppurativa'

'acne inversa'/exp OR 'acne inversa'

velpeau

'verneuil disease'/exp OR 'verneuil disease'

'heart infarction'/exp OR 'heart infarction'

'coronary artery disease'/exp OR 'coronary artery disease'

'heart muscle ischemia'/exp OR 'heart muscle ischemia'

'st segment elevation myocardial infarction'/exp OR 'st segment elevation myocardial infarction'

'non st segment elevation myocardial infarction'/exp OR 'non st segment elevation myocardial infarction'

'unstable angina pectoris'/exp OR 'unstable angina pectoris'

'chronic stable angina'/exp OR 'chronic stable angina'

'stable angina pectoris'/exp OR 'stable angina pectoris'

'acute coronary syndrome'/exp OR 'acute coronary syndrome'

'ischemic heart disease'/exp OR 'ischemic heart disease'

'cardiovascular disease'/exp OR 'cardiovascular disease'

#1 OR #2 OR #3 OR #4 OR #5

#6 OR #7 OR #8 OR #9 OR #10 OR #11 OR #12 OR #13 OR #14 OR #15 OR #16

#17 AND #18

Ovid Medline Database

hidradenitis suppurativa.mp. or exp Hidradenitis Suppurativa

suppurative hidradenitis.mp.

acne inversa.mp.

velpeau.mp.

verneuil's disease.mp.

coronary artery disease.mp. or exp Coronary Artery Disease/

myocardial infarction.mp. or exp Myocardial Infarction/

myocardial ischemia.mp. or exp Myocardial Ischemia/

st segment elevation myocardial infarction.mp. or exp ST Elevation Myocardial Infarction/

non st segment elevation myocardial infarction.mp. or exp Non-ST Elevated Myocardial Infarction/

unstable angina.mp. or exp Angina, Unstable/

chronic stable angina.mp. or exp Angina, Stable/

acute coronary syndrome.mp. or exp Acute Coronary Syndrome/

ischemic heart disease.mp.

coronary heart disease.mp. or exp Coronary Disease/

cardiovascular disease.mp. or exp Cardiovascular Diseases/

1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5

6 or 7 or 8 or 9 or 10 or 11 or 12 or 13 or 14 or 15 or 16

17 and 18

References

- 1.Reiss AB, Jacob B, Ahmed S, Carson SE, DeLeon J. Understanding accelerated atherosclerosis in systemic lupus erythematosus: Toward better treatment and prevention. Inflammation. 2021;44:1663–82. doi: 10.1007/s10753-021-01455-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Libby P. Inflammation in atherosclerosis. Nature. 2002;420:868–74. doi: 10.1038/nature01323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Montecucco F, Mach F. Common inflammatory mediators orchestrate pathophysiological processes in rheumatoid arthritis and atherosclerosis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2009;48:11–22. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ken395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abou-Raya A, Abou-Raya S. Inflammation: A pivotal link between autoimmune diseases and atherosclerosis. Autoimmun Rev. 2006;5:331–7. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2005.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Niessner A, Sato K, Chaikof EL, Colmegna I, Goronzy JJ, Weyand CM. Pathogen-sensing plasmacytoid dendritic cells stimulate cytotoxic T-cell function in atherosclerotic plaque through interferon-alpha. Circulation. 2006;114:2482–9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.642801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hänsel S, Lässig G, Pistrosch F, Passauer J. Endothelial dysfunction in young patients with long-term rheumatoid arthritis and low disease activity. Atherosclerosis. 2003;170:177–80. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(03)00281-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xu J, Lupu F, Esmon CT. Inflammation, innate immunity and blood coagulation. Hamostaseologie. 2010;30:5-6, 8-9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stark K, Massberg S. Interplay between inflammation and thrombosis in cardiovascular pathology. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2021;18:666–82. doi: 10.1038/s41569-021-00552-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maradit-Kremers H, Nicola PJ, Crowson CS, Ballman KV, Gabreil SE. Cardiovascular death in rheumatoid arthritis: A population-based study. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:722–32. doi: 10.1002/art.20878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bessant R, Hingorani, Patel L, MacGregor A, Isenberg DA, Rahman A. Risk of coronary heart disease and stroke in a large British cohort of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2004;43:924–9. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keh213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zwain A, Aldiwani M, Taqi H. The association between psoriasis and cardiovascular disease. Eur Cardiol. 2021;16:e19. doi: 10.15420/ecr.2020.15.R2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Masson W, Lobo M, Molinero G. Psoriasis and cardiovascular risk: A comprehensive review. Adv Ther. 2020;37:2017–33. doi: 10.1007/s12325-020-01346-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ungprasert P, Koster MJ, Warrington KJ, Matteson EL. Polymyalgia rheumatica and risk of coronary artery disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Rheum Int. 2017;37:143–9. doi: 10.1007/s00296-016-3557-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Preda-Naumescu A, Ahmed HN, Mayo TT, Yusuf N. Hidradenitis suppurativa: Pathogenesis, clinical presentation, epidemiology, and comorbid associations. Int J Dermatol. 2021;60:e449–58. doi: 10.1111/ijd.15579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garg A, Kirby JS, Lavian J, Lin G, Strunk A. Sex- and age-adjusted population analysis of prevalence estimated for Hidradenitis suppurativa in the United States. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:760–4. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.0201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wells GA, Shea B, O'Connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. http: //www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp.

- 17.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trial. 1986;7:177–88. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327:557–60. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Egeberg A, Gislason GH, Hansen PR. Risk of major adverse cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:429–34. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2015.6264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hung CT, Chiang CP, Chung CH, Tsao CH, Chien WC, Wang WM. Increased risk of cardiovascular comorbidities in hidradenitis suppurativa: A nationwide, population-based, cohort study in Taiwan. J Dermatol. 2019;46:867–73. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.15038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reddy S, Strunk A, Jemec GBE, Garg A. Incidence of myocardial infarction and cerebrovascular accident in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:65–71. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.3412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kjærsgaard Andersen R, Jørgensen IF, Reguant R, Jemec GBE, Brunak S. Disease trajectories for hidradenitis suppurativa in the Danish population. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:780–6. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.1281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miller IM, Ahlehoff O, Zarchi K, Rytgaard H, Mogensen UB, Ellervik C, et al. Hidradenitis suppurativa is associated with myocardial infarction, but not stroke or peripheral arterial disease of the lower extremities. Br J Dermatol. 2018;178:790–1. doi: 10.1111/bjd.15998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ward RA, Kakaati R, Liu B, Green C, Jaleel T. Hidradenitis suppurativa is associated with increased odds of stroke, coronary artery disease, heart failure and PAD: A population-based analysis in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:AB1. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hua VJ, Kilgour JM, Cho HG, Li S, Sarin KY. Characterization of comorbidity heterogeneity among 13,667 patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. JCI Insight. 2021;6:e151872. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.151872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Collins T, Cybulsky MI. NF-kB: Pivotal mediator or innocent bystander in atherogenesis? J Clin Invest. 2001;107:255–64. doi: 10.1172/JCI10373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rajavashisth TB, Liao JK, Galis ZS, Tripathi S, Laufs U, Chai NN, et al. Inflammatory cytokines and oxidized low density lipoproteins increase endothelial cell expression of membrane type 1-matrix metalloproteinases. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:11924–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.17.11924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Revuz JE, Canoui-Poitrine F, Wolkenstein P, Viallette C, Gabison G, Pouget F, et al. Prevalence and factors associated with hidradenitis suppurativa: Results from two case-control studies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:596–601. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2008.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Teo KK, Rafiq T. Cardiovascular risk factors and prevention: A perspective from developing countries. Can J Cardiol. 2021;37:733–43. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2021.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Strohmayer EA, Krakoff LR. Glucocorticoids and cardiovascular risk factors. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2011;40:409–17. doi: 10.1016/j.ecl.2011.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Material 1 – Searching strategy

EMBASE Database

'suppurative hidradenitis'/exp OR 'suppurative hidradenitis'

'hidradenitis suppurativa'/exp OR 'hidradenitis suppurativa'

'acne inversa'/exp OR 'acne inversa'

velpeau

'verneuil disease'/exp OR 'verneuil disease'

'heart infarction'/exp OR 'heart infarction'

'coronary artery disease'/exp OR 'coronary artery disease'

'heart muscle ischemia'/exp OR 'heart muscle ischemia'

'st segment elevation myocardial infarction'/exp OR 'st segment elevation myocardial infarction'

'non st segment elevation myocardial infarction'/exp OR 'non st segment elevation myocardial infarction'

'unstable angina pectoris'/exp OR 'unstable angina pectoris'

'chronic stable angina'/exp OR 'chronic stable angina'

'stable angina pectoris'/exp OR 'stable angina pectoris'

'acute coronary syndrome'/exp OR 'acute coronary syndrome'

'ischemic heart disease'/exp OR 'ischemic heart disease'

'cardiovascular disease'/exp OR 'cardiovascular disease'

#1 OR #2 OR #3 OR #4 OR #5

#6 OR #7 OR #8 OR #9 OR #10 OR #11 OR #12 OR #13 OR #14 OR #15 OR #16

#17 AND #18

Ovid Medline Database

hidradenitis suppurativa.mp. or exp Hidradenitis Suppurativa

suppurative hidradenitis.mp.

acne inversa.mp.

velpeau.mp.

verneuil's disease.mp.

coronary artery disease.mp. or exp Coronary Artery Disease/

myocardial infarction.mp. or exp Myocardial Infarction/

myocardial ischemia.mp. or exp Myocardial Ischemia/

st segment elevation myocardial infarction.mp. or exp ST Elevation Myocardial Infarction/

non st segment elevation myocardial infarction.mp. or exp Non-ST Elevated Myocardial Infarction/

unstable angina.mp. or exp Angina, Unstable/

chronic stable angina.mp. or exp Angina, Stable/

acute coronary syndrome.mp. or exp Acute Coronary Syndrome/

ischemic heart disease.mp.

coronary heart disease.mp. or exp Coronary Disease/

cardiovascular disease.mp. or exp Cardiovascular Diseases/

1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5

6 or 7 or 8 or 9 or 10 or 11 or 12 or 13 or 14 or 15 or 16

17 and 18