Abstract

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a common chronic dermatological condition affecting ~10% of adults and ~20% of the paediatric population in high-income countries. There is a lack of comprehensive understanding of the disease burden of AD in India. In this systematic review, the primary objective was to review epidemiological data on AD in India based on articles published between 2011 and 2021. The secondary objective was to assess the disease burden from economic and quality of life (QoL) perspectives. A literature search was conducted using the PubMed and Google Scholar databases using predefined search strings. Relevant studies published in English on AD between 2011 and 2021 were included. This review included 11 articles, of which nine reported demographic and clinical characteristics. The reported prevalence ranged from 3.1% to 7.21% among the paediatric population, up to 16 years of age. The prevalence of AD ranged from 0.98% to 9.2% in studies including paediatric and adult patients. The cost of medications was reported to be the major contributor to the economic burden associated with AD. Mental illnesses such as depression and anxiety were frequently reported in association with AD. Although AD is a common disorder affecting all age groups, there is a lack of substantial epidemiological data. None of the current studies covers the entire country. Hence, studies with a wider geographic scope covering all aspects of disease burden are required to help clinicians and policymakers to understand the disease burden and devise appropriate preventive and management strategies.

Key Words: Atopic dermatitis, disease burden, epidemiology, skin disease

Introduction

Atopic dermatitis (AD), an inflammatory dermatological disorder, affects ~10% of adults and up to 20% of children in high-income countries. AD has the highest disease burden based on disability-adjusted life-years among dermatological disorders and ranks 15th among all non-fatal diseases.[1,2]

AD is a chronic and heterogenous condition.[1,3] AD does not present with a fixed set of clinical symptoms. Its severity and course are dependent on environmental and genetic factors.[3] The symptoms of AD appear during the initial years of life in around 80% of patients. The disease goes into remission for 60% of the patients in adolescence.[4,5] Cases of adult-onset AD have been documented, but the prevalence appears to be less as compared to childhood-onset AD.[6]

In India, the prevalence of AD has been reported to be increasing owing to changes in environmental factors.[7] Most of the demographic data in India has been reported from hospital-based studies.[8,9] Epidemiological information is vital to understanding the disease burden across age groups and contributes to planning management strategies.[10] Currently, there is a lack of a pan-Indian study investigating the AD disease burden. Hence, understanding the epidemiology and disease burden of AD in India is important. The treatment landscape for AD is evolving, with newer treatment options being available in the arsenal. AD being a chronic disease, it is vital for patients to receive a treatment that will help in managing their condition.

In this systematic review, the primary objective was to review and analyse demographic data on the prevalence and incidence of AD in India based on articles published between 2011 and 2021. The secondary objective was to assess the disease burden from economic and quality of life (QoL) perspectives.

Methods

PubMed and Google Scholar databases were searched for articles published between 1st January 2011 and 31st December 2021 on AD from India. The search was conducted using the following search strings: “(Atopic Dermatitis) AND (India)”; “(Atopic Dermatitis) AND (India) AND (Disease Burden)”; “(Atopic Dermatitis) AND (India) AND (Economic)”; and “(Atopic Dermatitis) AND (India) AND (Quality of Life)”.

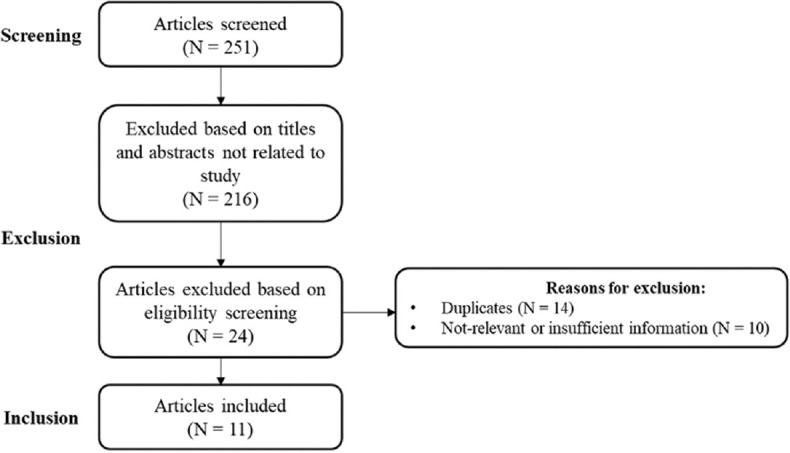

Articles were screened for relevance, and articles in languages other than English were excluded. Studies on AD reporting demographics, patient characteristics, pharmacoeconomic evaluation, and QoL in India were included. The process of study selection has been represented using a flow diagram in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow-diagram for literature search

From the included articles, the following information was extracted: reference details, type of study, study period, number of cases, sample size, gender distribution, diagnosis criteria, severity classification criteria, mean/median age, age of onset, severity, prevalence/incidence, comorbidities, pharmacoeconomic outcomes, and QoL outcomes.

All the articles included in the review were assessed for the risk of bias using the Hoy 2012 [Table 2]. Each parameter was assessed to have either a low or high risk of bias. Overall assessment of bias was according to the number of “high” risks of bias in the parameters per study: low ≤2, moderate, and high ≥5.

Table 2.

Risk of bias assessment (using the Hoy 2012 tool)

| Reference | 1. Representation | 2. Sampling | 3. Random Selection | 4. Non-response bias | 5. Data Collection | 6. Case Definition | 7. Reliability Tool | 8. Method of data collection | 9. Numerators and Denominators | Summary Assessment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Narayan 2019[26] | High | High | High | Unsure | Low | Low | Unsure | Low | High | Moderate |

| Kumar 2014[27] | Low | Low | Low | Unsure | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Kumar 2014[23] | Low | Low | Low | Unsure | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Agarwal 2014[25] | Low | High | Low | Unsure | Low | High | Low | Low | Low | Moderate |

| Sehgal 2015[28] | Low | Low | High | Unsure | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Kumar 2019[29] | Low | High | Low | Unsure | Low | High | Low | Low | Low | Moderate |

| Qureshi 2016[24] | Low | High | Low | Unsure | Low | High | Low | Low | Low | Moderate |

| Grills 2012[30] | Low | Low | Low | Unsure | Low | High | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Upendra 2017[22] | Low | Low | High | Unsure | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

Results

Search results

Through a literature search, 251 articles were screened. Of these, 216 search results included articles on AD management or were not related to AD. Further, 24 articles were identified as duplicates, and 10 articles either did not contain the relevant information on AD demography/patient characteristics or did not contain sufficient required information. Thus, 11 articles were included in this systematic review.

Study characteristics

The studies covered information gathered between 2010 and 2017 and were conducted across various regions of India. There were seven cross-sectional studies and one point-prevalence study. The other three studies did not mention the study design explicitly. Among the 11 studies, four studies used the Hanifin and Rajka criteria to identify AD patients, two studies used William's criteria (UK working party criteria), and the remaining studies did not disclose the criteria used. Among the studies reporting the severity of AD, three studies used the SCORing atopic dermatitis (SCORAD) tool, and one study used the Six-Area, Six-Sign Atopic Dermatitis (SASSAD) severity index.

Epidemiology and patient characteristics

Among the included studies, nine studies reported information on demographics and patient characteristics. Among them, one study reported only patient characteristics of AD as secondary data points. The reported prevalence ranged from 3.1% to 7.21% among the paediatric population, as determined by studies conducted on children aged 0 to 16 years old using surveys or hospital-based data collection. Four studies included paediatric as well as adult AD patients. Two studies from North India reported a prevalence of AD of 9.2%, while another study reported a prevalence of 0.98% across all age groups. A hospital-based study reported a point prevalence of 6.75% amongst outpatient attendees on a single day in one medical college in each of the four zones of India.

The age of onset was reported by four studies. Two studies conducted in North India reported mean ages at onset of 2.13 ± 2.10 and 3.63 ± 1.42 years, respectively. Another study from central India reported the age at onset to be 2.14 ± 0.5 years. A study conducted in Eastern India noted 5.2 (±3.01) months as the age of onset in children below 1 year of age and 3.47 ± 3.02 years in children aged between 1 and 15 years. Male predominance was observed in three studies and female predominance in three studies.

Among the studies that reported the severity of AD, one noted that the majority of the patients (84.4%, n/N = 90/1943) suffered from mild AD based on the SCORAD tool. Another study reported the mean SCORAD score to be 32.02 ± 12.16. The majority of the patients in this study had moderate-to-severe AD (56.4%, N = 55). Please refer to Table 1.

Table 1.

AD demography and patient characteristics

| Reference | Type of Study | Study Period | Patient Population | Definition/Identification criteria | No. of cases | N | F: M (% males) | Disease severity assessment criteria | Age range | Age at onset | Severity | Prevalence | Incidence | Co- morbidities |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Narayan 2019[26] | Hospital- based cross- sectional study | ~ | AD patients | Hanifin and Rajka’s criteria | 55 | 55 | 26/29 (52.7%) | SCORAD | ~ | 2.13±2.10 | Mild - 32.7% Moderate-to -severe - 56.4% Severe 10.9% Mean SCORAD score - 32.02±12.16 | ~ | ~ | ~ |

| Kumar 2014[27] | Hospital- based , point- prevalence, cross-sectional study | 20-Nov-12 (single day) | Psoriasis, vitiligo, and AD patients | Hanifin and Rajka’s criteria | ~ | 4785 | 1.25:1 | ~ | ~ | ~ | ~ | Point prevalence: 6.75% | ~ | ~ |

| Kumar 2014[23] | Prospective hospital-based study | January 2010 to December 2011 | ~ | 132 | 1829 | 75/57 (43.2%) | SCORAD | 0 months to 15 years | Infantile (<1 years) - 5.2 (± 3.01) months Childhood (1 to 15) – 3.47 (± 3.02) years | SCORAD Infantile Mild - 17.8±4.29 Moderate - 38.35±8.28 Severe - 88.42±14.24 SCORAD Childhood Mild - 12.3±5.1 Moderate - 33.3±7.5 Severe - 64.9±11.89 | 7.21% of all pediatric dermatoses | ~ | ~ | |

| Agarwal 2014[25] | Not mentioned | 5 years | Vitiligo patients | ~ | 25 | 268 | ~ | ~ | 1 month to 72 years | ~ | ~ | 4.9% | ~ | Vitiligo |

| Sehgal 2015[28] | Cross- sectional descriptive study | May 2010 - December 2011 | AD patients | Hanifin and Rajka’s criteria | 100 | 100 | 35/65 (65%) | SASSAD | <2 years to >18 years | 3.63±1.42 | Mean SASSAD - 38.46±12.69 | Overall: 0.98% (new plus old cases) 0.24% (newly diagnosed cases) | ~ | ~ |

| Kumar 2019[29] | Cross-sectional study | June 2017 to August 2017 | Asthma patients | ~ | 26 | 95 | 6/20 (76.9%) | ~ | 5-15 years | ~ | ~ | 27.4% | ~ | Asthma |

| Qureshi 2016[24] | Community- based cross-sectional study | 15 March 2012 to 15 May 2013 | School children (epidemiology study for bronchial asthma) | ~ | 25 | 806 | ~ | ~ | 10 to 16 years | ~ | ~ | 3.1% | ~ | Bronchial asthma |

| Grills 2012[30] | Cross-sectional cluster | March 2010 | General population (prevalence survey for dermatological conditions) | ~ | 111 | 1250 | ~ | ~ | <5 years to>65 years | ~ | ~ | 9.2% | ~ | ~ |

| Upendra 2017[22] | Cross-sectional study | ~ | AD patients | Hanifin and Rajka’s criteria | 90 | 1943 | 52/38 (42.2%) | SCORAD | 6-16 years | 2.14±0.5 | Mild - 84.4% Moderate - 13.3% Severe - 2.2% | 4.60% | ~ | Allergic rhinitis - 27.8% Bronchial asthma - 13.3% |

F: M, female: male; N, number; SASSAD, Six Area Six Sign Atopic Dermatitis; SCORAD, SCORing Atopic Dermatitis

Economic burden of atopic dermatitis

The economic burden of AD was reported in one study conducted by Handa et al.[11] The study identified paediatric AD patients using the U.K. Working Party's Diagnostic criteria in an outpatient hospital setting to prospectively assess the total cost of care. The total cost for 6 months included mean caregiver cost, provider cost and indirect cost. The mean total cost of AD management was Rs. 6235.00 ± 3514.00 (range: 2304–17,764) for 6 months. The direct caregiver cost comprised 50.2%, the direct provider cost comprised 18.1%, and the indirect cost comprised 31.7% of the total cost. The cost of medications was reported to amount to 73.37% of the caregiver cost.[11]

Quality of life outcomes in atopic dermatitis patients

From the literature search, one study was included that evaluated the presence of depression and anxiety in AD patients aged between 10 and 74 years (mean age: 34.94 ± 15.89 years). The study utilised the Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders (PRIME-MD) tool to assess the presence of psychiatric illnesses and the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) and Generalized Anxiety Disorder Questionnaire to assess depression and anxiety. The study reported a prevalence of 15% for depression and 12% for anxiety. Females outnumbered males among those with either depression or anxiety. Suicidal ideation was found to have a positive correlation with total PHQ-9 and GAD-7 scores.[12]

Discussion

In the systematic review, the prevalence of AD in paediatric patients ranged from 3.1% to 7.21%. The prevalence of AD among all age groups ranged from 0.98 to 9.2%. Among the included studies, the diagnosis of AD was done using the Hanifin and Rajka criteria in four studies and William's criteria (UK Working Party Criteria) in two studies. The mean age of onset in Indian paediatric patients ranged from 5.2 months to 3.63 years. The pharmacoeconomic study included in this review indicates that the cost of medication is the major contributor to the economic burden associated with AD. This implied the need for more information on the health and economic outcomes of AD. One study assessed the association of mental illnesses with AD patients. In addition to the overall QoL affected due to AD, illnesses like depression, anxiety and, in some cases, suicidal ideations, are causes of concern.

In the systematic review conducted by Bylund et al.,[10] the 1-year prevalence of doctor-diagnosed AD in the 21st century ranged from 1.2% in Asia to 17.1% in Europe among adults. The 1-year prevalence of doctor-diagnosed AD among paediatric patients in Asia ranged from 0.96% to 22.6%. A cross-sectional study conducted in various countries across the globe reported 12-month AD prevalence ascertained using the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC) and self-reported diagnosis to be 2.7–20.1%. Among paediatric patients, AD prevalence was determined to be 13.5–41.9% using the ISAAC diagnostic tool alone.[13] This study included patients from Japan and Taiwan in East Asia. The prevalence in Japan was observed to be 10.7% with a female predominance, while the prevalence in Taiwan was observed to be 11.3% with a male predominance.[13] Studies conducted in the past have reported the mean age of disease onset among paediatric patients to be 4.2–4.5 months for infantile AD, 4–4.1 years for childhood AD, and 4.58 years for the overall paediatric population.[14,15,16]

A pharmacoeconomic study conducted on multiethnic Asian children with AD evaluated the cost of care. The average annual cost per child was determined to be U. S. Dollars 7943, with the major cost contributors being informal caregiving and out-of-pocket expenses.[17] In India, the majority of patients still do not have insurance coverage. They end up paying out of pocket. The economic burden of AD hence needs to be factored in while developing guidelines and policies.

The QoL of AD patients is impacted due to the chronic nature of the condition. Patients experience dissatisfaction with life, and their physical health is further impacted. The caregivers and family members of the patients are also affected.[18,19] A US study conducted on adult AD patients reported a significant impact on the mental and physical health of the patients. The study utilised self-reported scoring systems like the Patient-Oriented Eczema Measure, Patient-Oriented Scoring AD, PO-SCORADitch, and sleep to determine the severity. QoL was assessed using the short-form (SF-) 12 mental and physical health scores and the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI). Patients with moderate-to-severe AD scored low on the SF-12 and DLQI surveys.[18]

AD has been associated with other atopic conditions like asthma, allergic rhinitis and food allergies among others. AD patients have also been observed to suffer from mood disorders like anxiety and depression. Suicidal ideation and suicide attempts have also been linked to the condition.[20,21] Paediatric patients have been associated with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Paediatric patients with AD are at risk of developing other atopic conditions. This is referred to as the 'atopic march'.[20] In the studies included, one study reported allergic rhinitis as a comorbidity in paediatric patients,[22] three studies reported an association with asthma,[22,23,24] and one study that included patients aged between 1 month and 72 years reported an association with vitiligo.[25]

This systematic review provides a critical assessment of the reviewed studies. The findings report data from representative epidemiological studies from across India. This systematic review was however limited due to a few eligible studies and the heterogenous nature of the studies. Although this review reports findings from diverse settings, some of the included studies were designed to assess the prevalence of AD, while others reported AD as a secondary outcome.

AD is a common disorder that affects patients of all age groups. There are a very few studies on the epidemiology of AD published in India between 2011 and 202The majority of the studies focus on paediatric patients. The range of prevalence noted in the publications considered for this article is very wide. There is a need to generate structured epidemiological data on AD in India for all age groups to help shape clinical strategies for managing AD. The studies need to focus on determining the course of the disease and gathering insights on its impact on QoL and economic implications.

Financial support and sponsorship

Pfizer India.

Conflicts of interest

Dr Abhishek De is the Associate Editor for the Indian Journal of Dermatology. Authors Sonali Karekar and Charles Adhav are full-time employees of Pfizer India.30

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to acknowledge Ms Vaidehi Wadhwa (Medical Excellence, Emerging Markets, Pfizer Ltd.) for providing medical writing support.

References

- 1.Langan SM, Irvine AD, Weidinger S. Atopic dermatitis. Lancet. 2020;396:345–60. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31286-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Laughter MR, Maymone MBC, Mashayekhi S, Arents BWM, Karimkhani C, Langan SM, et al. The global burden of atopic dermatitis: Lessons from the Global Burden of Disease Study 1990-2017. Br J Dermatol. 2021;184:304–9. doi: 10.1111/bjd.19580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim J, Kim BE, Leung DYM. Pathophysiology of atopic dermatitis: Clinical implications. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2019;40:84–92. doi: 10.2500/aap.2019.40.4202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.von Kobyletzki LB, Bornehag CG, Breeze E, Larsson M, Lindstrom CB, Svensson A. Factors associated with remission of eczema in children: A population-based follow-up study. Acta Derm Venereol. 2014;94:179–84. doi: 10.2340/00015555-1681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weidinger S, Beck LA, Bieber T, Kabashima K, Irvine AD. Atopic dermatitis. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2018;4:1. doi: 10.1038/s41572-018-0001-z. doi: 10.1038/s41572-018-0001-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hadi HA, Tarmizi AI, Khalid KA, Gajdacs M, Aslam A, Jamshed S. The epidemiology and global burden of atopic dermatitis: A narrative review. Life (Basel) 2021;11:936. doi: 10.3390/life11090936. doi: 10.3390/life11090936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sarkar R, Narang I. Childhood atopic dermatitis-An Indian perspective. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018;35:e330–1. doi: 10.1111/pde.13551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kanwar AJ. Adult-onset Atopic Dermatitis. Indian J Dermatol. 2016;61:662–3. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.193679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rajagopalan M, De A, Godse K, Krupa Shankar DS, Zawar V, Sharma N, et al. Guidelines on management of atopic dermatitis in India: An evidence-based review and an expert consensus. Indian J Dermatol. 2019;64:166–81. doi: 10.4103/ijd.IJD_683_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bylund S, Kobyletzki LB, Svalstedt M, Svensson A. Prevalence and incidence of atopic dermatitis: A systematic review. Acta Derm Venereol. 2020;100:adv00160. doi: 10.2340/00015555-3510. doi: 10.2340/00015555-3510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Handa S, Jain N, Narang T. Cost of care of atopic dermatitis in India. Indian J Dermatol. 2015;60:213. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.152573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mina S, Jabeen M, Singh S, Verma R. Gender differences in depression and anxiety among atopic dermatitis patients. Indian J Dermatol. 2015;60:211. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.152564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Silverberg JI, Barbarot S, Gadkari A, Simpson EL, Weidinger S, Mina-Osorio P, et al. Atopic dermatitis in the pediatric population: A cross-sectional, international epidemiologic study. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2021;126:417–28.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2020.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dhar S, Kanwar AJ. Epidemiology and clinical pattern of atopic dermatitis in a North Indian pediatric population. Pediatr Dermatol. 1998;15:347–51. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1470.1998.1998015347.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dhar S, Kanwar AJ. Epidemiology and clinical pattern of atopic dermatitis in 100 children seenin city hospital. Indian J Dermatol. 2002;47:202–4. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sarkar R, Kanwar AJ. Clinico-epidemiological profile and factors affecting severity of atopic dermatitis in north Indian children. Indian J Dermatol. 2004;49:117–22. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Olsson M, Bajpai R, Wee LWY, Yew YW, Koh MJA, Thng S, et al. The cost of childhood atopic dermatitis in a multi-ethnic Asian population: A cost-of-illness study. Br J Dermatol. 2020;182:1245–52. doi: 10.1111/bjd.18442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Silverberg JI, Gelfand JM, Margolis DJ, Boguniewicz M, Fonacier L, Grayson MH, et al. Patient burden and quality of life in atopic dermatitis in US adults: A population-based cross-sectional study. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2018;121:340–7. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2018.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ali F, Vyas J, Finlay AY. Counting the burden: Atopic dermatitis and health-related quality of life? Acta Derm Venereol. 2020;100:adv00161. doi: 10.2340/00015555-3511. doi: 10.2340/00015555-3511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pope EI, Drucker AM. Comorbidities in pediatric atopic dermatitis. Indian J Paediatr Dermatol. 2018;19:102–7. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Silverberg JI. Comorbidities and the impact of atopic dermatitis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2019;123:144–51. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2019.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Upendra Y, Keswani N, Sendur S, Pallava A. The clinico-epidemiological profile of atopic dermatitis in residential schoolchildren: A study from South Chhattisgarh, India. Indian J Paediatr Dermatol. 2017;18:281–5. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kumar MK, Singh PK, Patel PK. Clinico-immunological profile and their correlation with severity of atopic dermatitis in Eastern Indian children. J Nat Sci Biol Med. 2014;5:95–100. doi: 10.4103/0976-9668.127296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Qureshi UA, Bilques S, Ul Haq I, Khan MS, Qurieshi MA, Qureshi UA. Epidemiology of bronchial asthma in school children (10-16 years) in Srinagar. Lung India. 2016;33:167–73. doi: 10.4103/0970-2113.177442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Agarwal S, Ojha A, Gupta S. Profile of vitiligo in kumaun region of uttarakhand, India. Indian J Dermatol. 2014;59:209. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.127706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Narayan V, Sarkar R, Barman KD, Prakash SK. Clinicoepidemiologic profile and the cutaneous and nasal colonization with methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus in children with atopic dermatitis from north India. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2019;10:406–12. doi: 10.4103/idoj.IDOJ_359_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kumar S, Nayak CS, Padhi T, Rao G, Rao A, Sharma VK, et al. Epidemiological pattern of psoriasis, vitiligo and atopic dermatitis in India: Hospital-based point prevalence. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2014;5((Suppl 1)):S6–8. doi: 10.4103/2229-5178.144499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sehgal VN, Srivastava G, Aggarwal AK, Saxena D, Chatterjee K, Khurana A. Atopic dermatitis: A cross-sectional (descriptive) study of 100 cases. Indian J Dermatol. 2015;60:519. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.164412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kumar P, Singh G, Goyal JP, Khera D, Singh K. Association of common comorbidities with asthma in children: A cross-sectional study. Sudan J Paediatr. 2019;19:88–92. doi: 10.24911/SJP.106-1544873451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grills N, Grills C, Spelman T, Stoove M, Hellard M, El-Hayek C, et al. Prevalence survey of dermatological conditions in mountainous north India. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:579–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2011.05131.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]