People with CKD face many symptoms and psychosocial stressors that negatively affect health-related quality of life (HRQOL).1 However, HRQOL is not routinely assessed in clinical care, nor are components of HRQOL captured in traditional outcomes studies of patients with CKD. A patient-reported outcome measure (PROM) can comprehensively survey physical and mental health reported directly by the patient, in a manner tailored to conditions being treated. The Kidney Disease Quality of Life 36 (KDQOL-36)2 is a PROM mandated by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services for use in dialysis care; however, there is no requirement for PROM use in non–dialysis-dependent CKD. Longitudinal capture of patient-reported outcomes represents an opportunity to integrate HRQOL into treatment planning and to deliver person-centered care.

To capture HRQOL-related information in adults with kidney disease attending the Johns Hopkins outpatient nephrology clinics, we developed an electronic PROM (ePROM) using elements of the KDQOL-362 (Symptoms and Problems subscale and questions focused on mental health), with additional questions assessing overall quality of life and nocturia given its prevalence in CKD.3 We integrated the ePROM into the electronic health record (EHR) as a CKD Symptom Survey (Figure 1A) distributed to patients through the MyChart patient portal (Epic Systems Corporation). Use of this ePROM was approved by the Johns Hopkins Institutional Review Board.

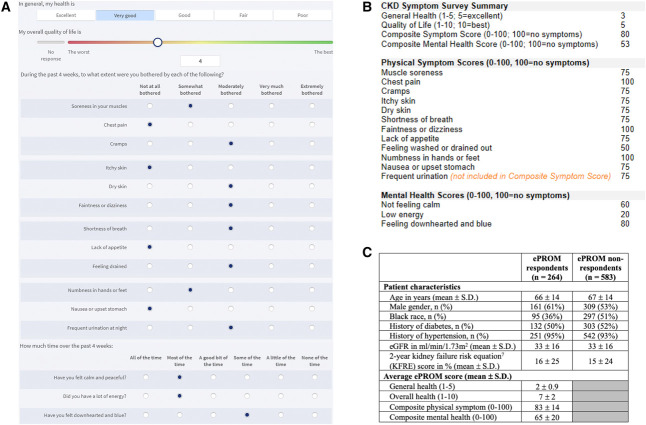

Figure 1.

The CKD Symptom Survey. (A) Patient view of the CKD Symptom Survey, which is an ePROM sent to patients with CKD G3–5 before each visit to the nephrology clinic. The survey can be completed ahead of time on MyChart or on a tablet handed to the patient on clinic check-in. Questions are largely derived from the KDQOL-36.2 (B) Provider view of ePROM scores displayed on input of the .CKDsymptoms dotphrase into clinic notes. Scores are calculated on the basis of published scoring guidelines.4 (C) Early ePROM completion metrics, including characteristics of patients who did or did not complete the ePROM, and average ePROM scores. ePROM, electronic patient-reported outcome measure; KDQOL-36, Kidney Disease Quality of Life 36; KFRE, kidney failure risk equation.

The ePROM assesses general health, overall quality of life, physical symptoms (12 questions), and mental health (three questions). Questions are scored according to recommended guidelines,4 with higher scores representing better quality of life and less prominent symptoms. Composite physical symptom scores do not include scores for frequent urination at night, given that nocturia is not assessed in the KDQOL-36.2 Nephrology providers can view scores on Epic's Synopsis tab or by adding the .CKDsymptoms dotphrase into clinic notes (Figure 1B). Prior and current ePROM scores are displayed to highlight changes in scores over time.

The ePROM is assigned to patients with CKD G3–5 (as determined by the EHR Problems list) presenting for a follow-up visit with their nephrology provider. The ePROM is not assigned before new patient visits because patients new to clinic may not have received education regarding their CKD diagnosis and associated symptoms. ePROMs are assigned before each follow-up visit to enable longitudinal assessment of symptoms over time, with a greater frequency of symptom capture for patients with advanced or rapidly progressive CKD who are anticipated to see providers more frequently. Appropriate capture of patients with CKD G3–5 on the basis of the EHR Problems list was not formally assessed.

An alert to complete the ePROM is sent through MyChart 7 days before clinic visits, with a reminder sent 1 day before the visit if not completed. Patients can alternatively complete the ePROM in person (using the Epic Welcome program) on an electronic tablet provided during clinic check-in. The results are linked to the visit and are immediately available in patient charts.

After pilot testing the ePROM with patients of one provider (D.M.P.) through MyChart only, followed by 2 months of ePROM distribution to all clinic patients, we captured 287 distinct ePROM responses (30% of 979 total ePROMs distributed) from 264 patients (some with multiple ePROM completions). On comparing the characteristics of ePROM respondents with nonrespondents (Figure 1C), we noted potential disparities in ePROM completion by race (a lower proportion of respondents were Black people) and sex (61% of respondents were male). Physical symptom scores reported by our patients align with those reported in a study of Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort participants.5

We noted important considerations regarding the ePROM. While the KDQOL-36 has been validated in non–dialysis-dependent CKD,6 input from patients and clinicians, with additional testing, is needed to refine the ePROM tool (content, method, and frequency of distribution) and maximize its utility. The ePROM has not been externally validated, which limits comparison of scores across different populations of people with CKD. After further assessment of differences in response rates on the basis of patient factors, interventions may be needed to improve ePROM to reach potentially marginalized populations (e.g., those with non-English primary languages, visual impairment, or limited literacy). Nephrology clinician perspectives are needed to identify facilitators and barriers to ePROM use in routine clinical care. Only after addressing these key issues, and after a cultural change prioritizing inclusion of patient-reported outcomes in care, can we achieve optimal implementation of ePROMs in non–dialysis-dependent CKD.

In summary, electronic health systems can enable dissemination of an ePROM to patients with CKD. The ePROM can be administered before each follow-up nephrology appointment, with results uploaded in patient charts such that they can guide clinic visits and treatment plans. Further research is needed to understand the reach of ePROMs, their effect on patient-provider relations, and associations between ePROM scores and clinical end points.

Acknowledgments

We thank all patients, nephrology providers, and nephrology clinic staff involved in ePROM dissemination and utilization.

Disclosures

J. Bitzel and D.M. Patel report employment with Johns Hopkins University. D.C. Crews reports employment with Johns Hopkins University; consultancy for Yale New Haven Health Services Corporation Center for Outcomes Research and Evaluation (CORE); research funding from Baxter International and Somatus, Inc.; honoraria from Maze Therapeutics; and other interests or relationships with Board of Directors of National Kidney Foundation of Maryland/Delaware, Council of Subspecialist Societies of the American College of Physicians, Executive Councilor of the American Society of Nephrology, and Nephrology Board of the American Board of Internal Medicine. D.C. Crews reports advisory or leadership roles for Advisory Group, Health Equity Collaborative, Partner Research for Equitable System Transformation after COVID-19 (PRESTAC); Associate Editor for Kidney360; Co-Chair of Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals Inc. Patient and Physician Advisory Board Steering Committee for Disparities in Chronic Kidney Disease Project; Editorial Boards for CJASN, JASN, and the Journal of Renal Nutrition; and Optum Labs. D.M. Fine reports employment with Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, consultancy for Fresenius Kidney Care Medical Advisory Board and GlaxoSmithKline DSMB, and advisory or leadership role for Medical Advisory Board—Fresenius Medical Corporation. T. Grader-Beck reports employment with Johns Hopkins, consultancy for IQVIA and Novartis, and advisory or leadership role for Novartis. M.E. Grams reports employment with New York University; advisory or leadership roles for the American Journal of Kidney Diseases, the American Society of Nephrology Publication Committee, CJASN, the JASN Editorial Fellowship Committee, the National Kidney Foundation Scientific Advisory Board, the Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes Executive Committee (co-chair elect), and the United States Renal Data System Scientific Advisory Board; grant funding from NKF, which receives funding from multiple pharmaceutical companies; grant funding from NIH; payment from academic institutions for grand rounds; and payment from NephSAP. C.R. Parikh reports employment with Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine; consultancy for Genfit Biopharmaceutical Company; ownership interest in Renaltix AI; research funding from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI) and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK); and advisory or leadership roles for Genfit Biopharmaceutical Company and Renalytix. S. Thavarajah reports employment with Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine and other interests or relationships with the National Kidney Foundation as a National Board member and member of the national scientific advisory board and with the local NKF chapter medical advisory board and board of advisors. S. Thavarajah reports advisory or leadership roles as Medical Advisory Board NKF of Maryland immediate past chair and as previous vice chair of Maryland Kidney Commission 2021–2022, and now chair. S. Thavarajah reports honoraria as a speaker for a CME program conducted by the NKF in December 2020—the NKF had funding for the program and provided a speaker's honorarium to each of the faculty speakers. The original funding was from Bayer, but the honorarium came through the NKF.

Funding

D.C. Crews: NHLBI Division of Intramural Research (K24 HL148181). D.M. Patel: School of Medicine, Johns Hopkins University (Edward S. Kraus Scholarship). M.E. Grams: NHLBI Division of Intramural Research (K24 HL155861).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Deidra C. Crews, Derek M. Fine, Morgan E. Grams, Dipal M. Patel, Sumeska Thavarajah.

Data curation: Jack Bitzel.

Formal analysis: Jack Bitzel.

Funding acquisition: Morgan E. Grams, Dipal M. Patel.

Investigation: Deidra C. Crews, Dipal M. Patel.

Methodology: Deidra C. Crews, Thomas Grader-Beck, Dipal M. Patel.

Software: Thomas Grader-Beck.

Supervision: Deidra C. Crews, Chirag R. Parikh.

Writing – original draft: Dipal M. Patel.

Writing – review & editing: Jack Bitzel, Deidra C. Crews, Derek M. Fine, Thomas Grader-Beck, Morgan E. Grams, Chirag R. Parikh, Dipal M. Patel, Sumeska Thavarajah.

References

- 1.Elliott MJ, Hemmelgarn BR. Patient-reported outcome measures in CKD care: the importance of demonstrating need and value. Am J Kidney Dis. 2019;74(2):148–150. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2019.04.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hays RD, Kallich JD, Mapes DL, Coons SJ, Carter WB. Development of the kidney disease quality of life (KDQOLTM) instrument. Qual Life Res. 1994;3(5):329–338. doi: 10.1007/bf00451725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Agarwal R. Developing a self-administered CKD symptom assessment instrument. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2010;25(1):160–166. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfp426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.RAND Corporation. Kidney Disease Quality of Life Instrument (KDQOL). Accessed March 2022. https://www.rand.org/health-care/surveys_tools/kdqol.html. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grams ME, Surapaneni A, Appel LJ, et al. Clinical events and patient-reported outcome measures during CKD progression: findings from the Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort Study. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2021;36(9):1685–1693. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfaa364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aiyegbusi OL, Kyte D, Cockwell P, et al. Measurement properties of patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) used in adult patients with chronic kidney disease: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2017;12(6):e0179733. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0179733 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tangri N, Stevens LA, Griffith J, et al. A predictive model for progression of chronic kidney disease to kidney failure. JAMA. 2011;305(15):1553–1559. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]