Abstract

Aim: Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy (HDP) are estimated to occur in up to 10% of all pregnancies and are associated with an increased risk of future cardiovascular disease (CVD) and chronic hypertension (HT). Therefore, we examined the impact of a history of HDP on CVD possibility in middle- and older-aged Japanese women.

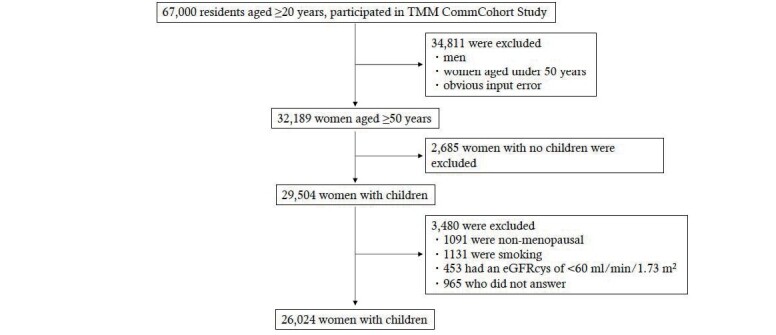

Methods: We used the Tohoku Medical Megabank database to obtain the data of 26,024 menopausal women who were aged ≥ 50 years, had children, did not smoke, and did not have chronic kidney disease and to analyze the relationship between HDP history and CVD.

Results: A history of HDP was found in 4.6% of women. We divided the women into four groups according to the presence or absence of HDP and HT. The percentage of women with dyslipidemia, diabetes mellitus, and body mass index of ≥ 25 kg/m2 was the highest in the HDP+ HT+ group compared to the other groups (43.4%, 24.0%, and 45.2%, respectively). Adjusted odds ratio (OR) for the combined six CVD categories was higher for those with a history of HDP alone (OR [95% confidence interval [CI]]: 1.61 [1.03–2.53]). Moreover, the OR was significantly higher for those with combination with HDP history and HT (OR [95% CI]: 4.11 [3.16–5.35]). The prevalence of individual CVD was also the highest in the HT+ HDP+ group.

Conclusion: An HDP history can influence the risk of CVD in Japanese women, indicating the importance of information about pregnancy outcomes in health management.

Keywords: Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, Cardiovascular disease risk, Hypertension, Women’s health

1.Introduction

Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy (HDP) are estimated to occur in up to 10% of all pregnancies 1) . HDP can be categorized into preeclampsia, gestational hypertension (HT), superimposed preeclampsia, and chronic HT. Though most HDP cases are temporary and often improve postpartum, HDP can have an impact on the long-term prognosis of women 2 - 4) .

Previous studies overseas suggested that women with a history of HDP are at an increased risk of future cardiovascular disease (CVD), chronic HT, and dyslipidemia (DL) compared with those with normotensive pregnancies 2 - 4) .

HDP prevalence has been increasing in other countries, including Japan 5 , 6) . Though the mortality rate of HDP decreased due to advanced medical intervention, the potential impact of HDP is increasing with the current trend of advanced maternal age and obesity. Therefore, HDP management strategies should be more intensively studied. Moreover, evidence is limited linking HDP history with future CVD risk among Japanese women. Therefore, we aimed to determine the impact of HDP history on CVD in relation to HT, another well-known risk factor for CVD, using the Tohoku Medical Megabank Community-based Cohort Study database that includes data on more than 30,000 women.

2.Aim

The aim of the present study was to elucidate the impact of the combination of HDP history and HT on the risk of CVD among middle- and older-aged Japanese women.

3.Methods

3.1 Study Design, Approval, and Ethics

This was a cross-sectional study approved by the Medical Research Ethics Committee of Tokyo Medical and Dental University (M2019-190).

3.2 Study Population

We used the Tohoku Medical Megabank Community-based Cohort Study database version 2.3.0 (TMM CommCohort Study, available at http://www.dist.megabank.tohoku.ac.jp/about/data/_2.3.0/index.html, accessed June 1, 2022), released by the Tohoku Medical Megabank Organization, Tohoku University, on July 31, 2019. This database contains the data of 67,000 residents of Iwate and Miyagi Prefectures in Northeastern Japan aged ≥ 20 years who provided their active consents 7 - 8) . This database also includes the obstetric and medical history of women, including CVD. This survey was performed in specific municipal health checkup sites, in which researchers explained the TMM CommCohort Study to participants in the health checkup, and informed consent was obtained with face-to-face individual interviews. The participants underwent a health checkup conducted by local governments once between 2013 and 2015, and their serum and plasma samples were collected. They also responded to questionnaires regarding their medical history. In addition, we used the estimated glomerular filtration rate using cystatin C (eGFRcys) values obtained at health checkups to ascertain chronic kidney disease (CKD). In the current study, approximately 32,000 women aged ≥ 50 years who had given birth and were not planning any more pregnancies were surveyed to investigate the effects of HDP. Of the 32,189 cases, excluding obvious input errors, there were 29,504 women with children. To adjust effects of known CVD risk factor, the analysis was performed on 26,024 menopausal women who did not smoke and had an eGFRcys of >60 ml/min/1.73 m2.

3.3 Variable Definitions

To assess the participants’ HDP history, the questionnaire asks, “Do you have a history of toxemia or hypertensive disorders of pregnancy?”. Demographic data, including number of children, age at first birth, age at last birth, HT, DL, diabetes mellitus (DM), menopausal status, and smoking status, were also obtained through the self-reported questionnaire. HT, DL, and DM were defined as currently being treated or the previous diagnosis. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated based on the height and weight measured at medical checkups. A BMI of 25 kg/m2 was used as the criterion for obesity based on the Japan Society for the Study of Obesity 9) . Menopausal status was defined as a woman’s affirmation to having experienced menopause. Smoking status was divided into two groups according to participants’ smoking history of ≥ 100 cigarettes in their lifetime. CKD was indicated by an eGFRcys of <60 ml/min/1.73 m 2 10) .

The outcome included the presence of any of the following CVDs: 1) angina/myocardial infarction, 2) cerebral infarction, 3) cerebral hemorrhage, 4) subarachnoid hemorrhage, 5) heart failure, and 6) aneurysm/aortic dissection. The presence of these CVDs was defined as currently under treatment or previous diagnosis.

3.4 Statistical Analyses

All statistical analyses were performed using JMPⓇ 15 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). Continuous variables were expressed as median and interquartile intervals and analyzed using the Kruskal–Wallis test. The baseline characteristics of the participants were compared according to a history of HDP and HT. Next, we examined the correlation of a history of HDP and CVD, using multivariable logistic regression models adjusted for the combination of HDP and HT, age group, obesity, DM, and DL. Inclusion of variables in the models was based on existing knowledge of risk factors for CVD 11) . Three- and two-factor interaction tests were also performed for HDP, HT, and age. In addition, the prevalence of each CVD by age group based on the presence or absence of HT and HDP was evaluated. All tests were two-sided, and a p-value of <0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

4.Results

We analyzed 26,024 women in this study ( Fig.1 ) . Table 1 presents the baseline characteristics of all study participants according to a history of HDP and HT. The prevalence of HDP was 4.6%. Although there was no difference in the median number of children among four groups, women with HDP (HDP+ HT− group and HDP+ HT+ group) tended to give birth at an older age.

Fig.1.

Flow diagram of study participants

Table 1. Study population characteristics by presence or absence of HDP.

| HDP- HT- | HDP+ HT- | HDP- HT+ | HDP+ HT+ | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of subjects (%) | 15506 (59.6) | 513 (2.0) | 9337 (35.9) | 668 (2.6) | N.A |

| Age, y Median (interquartile range) | 64 (60-68) | 63 (59-67) | 66 (63-70) | 65 (62-69) | <0.0001 |

| Number of children Median (interquartile range) | 2 (2-3) | 2 (2-3) | 2 (2-3) | 2 (2-3) | 0.001 |

| Age at first child, y Median (interquartile range) | 24 (23-27) | 25 (23-27) | 24 (23-26) | 25 (23-27) | <0.0001 |

| Age at last child, y Median (interquartile range) | 29 (27-32) | 30 (27-33) | 29 (27-32) | 30 (27-32) | <0.0001 |

| Women with Dyslipidemia, % | 3560 (22.9) | 142 (27.7) | 3417 (36.6) | 290 (43.4) | <0.0001 |

| Women with Diabetes, % | 1171 (7.55) | 52 (10.14) | 2053 (22.0) | 160 (24.0) | <0.0001 |

| Women with BMI is ≥ 25 kg/m2, % | 3132 (20.2) | 124 (24.2) | 3723 (39.9) | 301 (45.2) | <0.0001 |

HDP, hypertensive disorders of pregnancy; HT, hypertension; BMI, body mass index.

The percentage of women with DL, DM, and a BMI of ≥ 25 kg/m2 was significantly higher in the HDP+ HT+ group (43.4%, 24.0%, and 45.2%, respectively). Subsequently, we analyzed the adjusted odds ratios (ORs) for the combined six CVD categories for 26,024 women ( Table 2 ) . The ORs for the six CVDs were calculated for each of the following: combination of HT and HDP history, age group, obesity, DM, and DL. Three- and two-factor interaction tests were also performed for HDP, HT, and age, and no interaction effects were found to be statistically significant (HDP, HT, and age: p =0.96, HDP and HT: p=0.83, HDP and age: p =0.88, HT and age: p =0.43). HDP+ HT− was associated with CVD (OR [95% confidence interval [CI]]: 1.61 [1.03–2.53]). HDP+ HT+ was also associated with CVD (OR [95% CI]: 4.11 [3.16–5.35]). Age group and obesity were associated with CVD (OR [95% CI]; age 60s: 1.95 [1.56–2.43], age 70s and older: 3.22 [2.55–4.06], obesity: 1.15 [1.01–1.30]). By contrast, DM and DL were not associated with CVD.

Table 2. Adjusted ORs for six CVDs.

| ORs [95% CI] | P | |

|---|---|---|

| HDP+HT- (ref. HDP-HT-) | 1.61 (1.03-2.53) | 0.0370 |

| HDP-HT+ (ref. HDP-HT-) | 2.30 (2.02-2.63) | <0.0001 |

| HDP+HT+ (ref. HDP-HT-) | 4.11 (3.16-5.35) | <0.0001 |

| Age of 60s (ref. 50s) | 1.95 (1.56-2.43) | <0.0001 |

| Age of 70s and older (ref. 50s) | 3.22 (2.55-4.06) | <0.0001 |

| obesity (BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2) (ref. BMI <25 kg/m2) | 1.15 (1.01-1.30) | 0.0345 |

| DM (ref. no DM) | 1.14 (0.97-1.34) | 0.11 |

| DL (ref. no DL) | 1.09 (0.94–1.24) | 0.21 |

ORs, odds ratios; CVD, cardiovascular disease; HDP, hypertensive disorders of pregnancy; HT, hypertension; BMI, body mass index; DM, diabetes; DL, dyslipidemia.

We investigated the impact of HDP history on each of the six CVDs. We analyzed the prevalence of each CVD by age group with and without HT and HDP history ( Table 3 ) . The prevalence of angina/myocardial infarction, cerebral infarction, and heart failure generally increased with age. In particular, the prevalence of CVD in the 70s and older group was the highest among HT and HDP history (HT+ HDP+ group). On the contrary, the prevalence of the six CVDs was the lowest among those without HT and HDP history (HT− HDP− group).

Table 3. Prevalence of CVD by age group, presence or absence of HT and HDP.

| 50s (n = 4718) | 60s (n = 15110) | ≥ 70s (n = 6196) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| angina / myocardial infarction | |||||||

| HT category | HDP category | % | n/N | % | n/N | % | n/N |

| HT+ | HDP+ | 1.9 | 2/106 | 5.4 | 22/406 | 5.8 | 9/156 |

| HDP- | 0.8 | 9/1107 | 2.5 | 134/5359 | 4 | 116/2871 | |

| HT- | HDP+ | 0.8 | 1/132 | 1.6 | 5/306 | 4 | 3/75 |

| HDP- | 0.4 | 12/3373 | 1 | 93/9039 | 1.9 | 60/3094 | |

| cerebral infarction | |||||||

| HT category | HDP category | % | n/N | % | n/N | % | n/N |

| HT+ | HDP+ | 0.9 | 1/106 | 3.4 | 14/406 | 5.1 | 8/156 |

| HDP- | 1.4 | 16/1107 | 1.8 | 98/5359 | 2.5 | 71/2871 | |

| HT- | HDP+ | 0.8 | 1/132 | 1 | 3/306 | 0 | 0/75 |

| HDP- | 0.2 | 8/3373 | 0.6 | 50/9039 | 1.6 | 51/3094 | |

| cerebral hemorrhage | |||||||

| HT category | HDP category | % | n/N | % | n/N | % | n/N |

| HT+ | HDP+ | 1.9 | 2/106 | 1.7 | 7/406 | 1.9 | 3/156 |

| HDP- | 0.5 | 6/1107 | 0.7 | 35/5359 | 0.5 | 14/2871 | |

| HT- | HDP+ | 0 | 0/132 | 0 | 0/306 | 0 | 0/75 |

| HDP- | 0.1 | 2/3373 | 0.1 | 7/9039 | 0.2 | 7/3094 | |

| subarachnoid hemorrhage | |||||||

| HT category | HDP category | % | n/N | % | n/N | % | n/N |

| HT+ | HDP+ | 0 | 0/106 | 1.7 | 7/406 | 3.2 | 5/156 |

| HDP- | 0.4 | 4/1107 | 0.9 | 49/5359 | 1 | 29/2871 | |

| HT- | HDP+ | 0.8 | 1/132 | 0 | 0/306 | 1.3 | 1/75 |

| HDP- | 0.4 | 13/3373 | 0.3 | 31/9039 | 0.4 | 13/3094 | |

| heart failure | |||||||

| HT category | HDP category | % | n/N | % | n/N | % | n/N |

| HT+ | HDP+ | 0 | 0/106 | 1.2 | 5/406 | 2.6 | 4/156 |

| HDP- | 0.2 | 2/1107 | 0.3 | 14/5359 | 0.6 | 16/2871 | |

| HT- | HDP+ | 0 | 0/132 | 0.7 | 2/306 | 1.3 | 1/75 |

| HDP- | 0.1 | 2/3373 | 0.1 | 5/9039 | 0.2 | 7/3094 | |

| aneurysm/aortic dissection | |||||||

| HT category | HDP category | % | n/N | % | n/N | % | n/N |

| HT+ | HDP+ | 0 | 0/106 | 1.7 | 7/406 | 5.1 | 8/156 |

| HDP- | 0.5 | 5/1107 | 1 | 54/5359 | 1.2 | 34/2871 | |

| HT- | HDP+ | 0 | 0/132 | 1 | 3/306 | 1.3 | 1/75 |

| HDP- | 0.2 | 8/3373 | 0.5 | 47/9039 | 0.5 | 16/3094 | |

CVD, cardiovascular disease; HDP, hypertensive disorders of pregnancy; HT, hypertension.

5.Discussion

5.1 Pregnancy and Childbirth as a “Stress Test”

In the present study including women aged ≥ 50 years living in the Tohoku region, we found a correlation between HDP history and CVD. Adjusted ORs for the prevalence of the combined six CVDs were significantly higher among women with HDP history (HDP+ HT− group), especially combined with HT (HDP+ HT+ group; OR [95% CI]: 1.61 [1.03–2.53] and 4.11 [3.16–5.35], respectively). Currently, CVD is the leading cause of death among Japanese women 12) . Apart from the conventional risk factors for CVD, such as DL, smoking, and HT, there could be another risk factor specific for women. Though it could be physiological that lipid composition, glucose metabolism, and circulating blood volume markedly change during pregnancy 13) , a previous study suggests that those who failed to adapt to these changes during pregnancy experienced adverse pregnancy outcomes (APO) and had a higher risk of future CVD. Therefore, pregnancy and childbirth can be considered as a “stress test” and a predictor of future CVD 14) .

5.2 HDP History, HT, and Future CVD

HDP are defined as the presence of HT during pregnancy; in most cases, an increase in blood pressure was first observed after 20 weeks of gestation, and it returned to normal within 12 weeks postpartum 1) . The underlying mechanisms of HDP remain to be unknown, but recent studies suggested the potential roles for antiangiogenic factors such as soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase 1 and soluble endoglin induced by insufficient trophoblastic invasion to the placenta. These factors may cause damage to the maternal endothelial integrity 15) . Although the biological mechanisms are unknown, several common risk factors are shared by HDP and CVD 16) , or insults over time to the body are initiated by sustained damage to the vascular, endothelial, or metabolic systems during pregnancy. In Japan, the incidence rates of HDP were 3.8% in 2001 and 4.1% in 2015 17) . With the increasing incidence of advanced maternal age pregnancies or assisted reproductive pregnancies, which are risk factors for HDP 12) , the incidence of HDP is not expected to decrease in Japan.

A study in Japan reported a correlation between a history of HDP and HT, especially at a young age of 30s–50s 18) . Another report from Japan showed that women with a history of HDP have a higher incidence rate of HT at 5 years postpartum, suggesting an impact on younger age groups 19) . Similarly, a study from the Netherlands suggested that the prevalence of HT increased among the younger age group of women with a history of HDP 20) . Our results indicated that the ORs for CVDs were significantly increased among women with HDP history and HT, despite the absence of a statistical interaction between HDP history and HT. In addition, as shown in Table 3 , the prevalence of each CVD increased in the HT+ HDP+ group, suggesting that women with HDP are at potential risk when combined with HT. Our results also showed that the ORs for CVD significantly increased in accordance with age. Therefore, lifestyle modification and early management of HT among women with a history of HDP are important.

5.3 Importance of Pregnancy Outcome Information

The European Society of Hypertension and European Society of Cardiology guidelines suggest a primary care physician to conduct an annual follow-up of blood pressure 21 , 22) . In Japan, the Guidelines for the Management of Hypertension 2019 include a chapter on “Pregnancy-related hypertension,” but it only involved improving the perinatal prognosis 23) and few comments on their future CVD risks. The blood pressure of women with a history of HDP could increase as early as 5 years postpartum 19) . Thus, women with HDP history should be informed about the risk of HT and CVD, and the appropriate health care management should be addressed. Internists who manage women with HT should consider that women with HDP history are at a high risk of future CVD and should inquire about APO, especially HDP, when obtaining patient history. Moreover, future studies are needed to establish an efficient follow-up system to prevent the progression of CVD among women with a history of HDP.

5.4 Limitations

This study had several limitations. First, we used cross-sectional data and did not conduct a prospective analysis; therefore, the causal relationship between the factors remains to be unknown. Second, HDP history was self-reported, and the diagnostic criteria of HDP have changed over time, resulting in potential memory bias. Finally, we could not collect detailed information regarding pregnancy and delivery, the onset or severity of HDP, or any other factors that may have an impact on future CVD risk, such as stillbirth or breastfeeding 24) .

6.Conclusions

Women with a history of HDP should avoid HT, a major risk factor of CVD. Among women with HT, a history of HDP indicates a higher risk of CVD; internists should be aware of this risk.

Grant Support

This research was supported in part by a grant from the Japan Atherosclerosis Research Foundation.

Conflict of Interests

None.

References

- 1).Brown MA, Magee LA, Kenny LC, Karumanchi SA, McCarthy FP, Saito S, Hall DR, Warren CE, Adoyi G, Ishaku S, International Society for the Study of Hypertension in Pregnancy (ISSHP): Hypertensive Disorders of Pregnancy: ISSHP Classification, Diagnosis, and Management Recommendations for International Practice. Hypertension, 2018; 72: 24-43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2).Bellamy L, Casas JP, Hingorani AD, Williams DJ: Pre-eclampsia and risk of cardiovascular disease and cancer in later life: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ, 2007 doi: 10.1136/bmj.39335.385301.BE [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3).Stuart JJ, Tanz LJ, Rimm EB, Spiegelman D, Missmer SA, Mukamal KJ, Rexrode KM, Rich-Edwards JW: Cardiovascular Risk Factors Mediate the Long-Term Maternal Risk Associated with Hypertensive Disorders of Pregnancy. J Am Coll Cardiol, 2022; 79: 1901-1913 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4).Brown MC, Best KE, Pearce MS, Waugh J, Robson SC, Bell R: Cardiovascular disease risk in women with pre-eclampsia: systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Epidemiol, 2013; 28: 1-19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5).Wallis AB, Saftlas AF, Hsia J, Atrash HK: Secular trends in the rates of preeclampsia, eclampsia, and gestational hypertension, United States, 1987-2004. Am J Hypertens, 2008; 21: 521-526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6).Wang W, Xie X, Yuan T, Wang Y, Zhao F, Zhou Z, Zhang H: Epidemiological trends of maternal hypertensive disorders of pregnancy at the global, regional, and national levels: a population-based study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth, 2021 doi.org/10.1186/s12884-021-03809-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7).Hozawa A, Tanno K, Nakaya N, Nakamura T, Tsuchiya N, Hirata T, Narita A, Kogure M, Nochioka K, Sasaki R, Takanashi N, Otsuka K, Sakata K, Kuriyama S, Kikuya M, Tanabe O, Sugawara J, Suzuki K, Suzuki Y, Kodama EN, Fuse N, Kiyomoto H, Tomita H, Uruno A, Hamanaka Y, Metoki H, Ishikuro M, Obara T, Kobayashi T, Kitatani K, Igarashi KT, Ogishima S, Satoh M, Ohmomo H, Tsuboi A, Egawa S, Ishii T, Ito K, Ito S, Taki Y, Minegishi N, Ishii N, Nagasaki M, Igarashi K, Koshiba S, Shimizu R, Tamiya G, Nakayama K, Motohashi H, Yasuda J, Shimizu A, Hachiya T, Shiwa Y, Tominaga T, Tanaka H, Oyama K, Tanaka R, Kawame H, Fukushima A, Ishigaki Y, Tokutomi T, Osumi N, Kobayashi T, Nagami F, Hashizume H, Arai T, Kawaguchi Y, Higuchi S, Sakaida M, Endo R, Nishizuka S, Tsuji I, Hitomi J, Nakamura M, Ogasawara K, Yaegashi N, Kinoshita K, Kure, Sakai A, Kobayashi S, Sobue K, Sasaki M, and Yamamoto M: Study Profile of the Tohoku Medical Megabank Community-Based Cohort Study. J Epidemiol, 2021; 31: 65-76 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8).Egawa M, Kanda E, Ohtsu H, Nakamura T, and Yoshida M: Number of children and risk of cardiovascular disease in Japanese women: Findings from the Tohoku Medical Megabank. J Atheroscler Thromb, 2022 doi: 10.5551/jat.63527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9).Japan Society for the Study of Obesity. http://www.jasso.or.jp/contents/wod/index.html (Accessed June 1, 2022) [Google Scholar]

- 10).https://cdn.jsn.or.jp/data/CKD2018.pdf (Accessed June 1, 2022). In Japanese [Google Scholar]

- 11).Kinoshita M, Yokote K, Arai H, Iida M, Ishigaki Y, Ishibashi S, Umemoto S, Egusa G, Ohmura H, Okamura T, Kihara S, Koba S, Saito I, Shoji T, Daida H, Tsukamoto K, Deguchi J, Dohi S, Dobashi K, Hamaguchi H, Hara M, Hiro T, Biro S, Fujioka Y, Maruyama C, Miyamoto Y, Murakami Y, Yokode M, Yoshida H, Rakugi H, Wakatsuki A, Yamashita S, Committee for Epidemiology and Clinical Management of Atherosclerosis: Japan Atherosclerosis Society (JAS) Guidelines for Prevention of Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Diseases 2017. J Atheroscler Thromb, 2018; 25: 846-984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12).Vital Statistics. Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare. https://www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/list/81-1.html (Accessed June 1, 2022) [Google Scholar]

- 13).Ouzounian JG, Elkayam U: Physiologic changes during normal pregnancy and delivery. Cardiol Clin, 2012; 30: 317-329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14).Martinez G, Daniels K, Chandra A: Fertility of men and women aged 15-44 years in the United States: National Survey of Family Growth, 2006-2010. Natl Health Stat Report, 2012; 12: 1-28 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15).Shibata E, Rajakumar A, Powers RW, Larkin RW, Gilmour C, Bodnar LM, Crombleholme WR, Ness RB, Roberts JM, Hubel CA: Soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase 1 is increased in preeclampsia but not in normotensive pregnancies with small-for-gestational-age neonates: relationship to circulating placental growth factor. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 2005; 90: 4895-4903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16).Sattar N, Greer IA: Pregnancy complications and maternal cardiovascular risk: opportunities for intervention and screening? BMJ, 2002; 325: 157-160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17).Sato S: [Epidemiological Studies from the Japanese Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology Perinatal Registry Database Survey] (in Japanese). Sanka to Fujinka, 2019; 2: 163-169 [Google Scholar]

- 18).Wagata M, Kogure M, Nakaya N, Tsuchiya N, Nakamura T, Hirata T, Narita A, Metoki H, Ishikuro M, Kikuya M, Tanno K, Fukushima A, Yaegashi N, Kure S, Yamamoto M, Kuriyama S, Hozawa A, Sugawara J: Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, obesity, and hypertension in later life by age group: a cross-sectional analysis. Hypertens Res, 2020; 43: 1277-1283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19).Mito A, Arata N, Qiu D, Sakamoto N, Murashima A, Ichihara A, Matsuoka R, Sekizawa A, Ohya Y, Kitagawa M: Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy: a strong risk factor for subsequent hypertension 5 years after delivery. Hypertens Res, 2018; 41: 141-146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20).Groenhof TKJ, Zoet GA, Franx A, Gansevoort RT, Bots ML, Groen H, Lely AT, PREVEND Group: Trajectory of Cardiovascular Risk Factors After Hypertensive Disorders of Pregnancy. Hypertension, 2019; 73: 171-178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21).Williams B, Mancia G, Spiering W, Agabiti Rosei E, Azizi M, Burnier M, Clement DL, Coca A, de Simone G, Dominiczak A, Kahan T, Mahfoud F, Redon J, Ruilope L, Zanchetti A, Kerins M, Kjeldsen SE, Kreutz R, Laurent S, Lip GYH, McManus R, Narkiewicz K, Ruschitzka F, Schmieder RE, Shlyakhto E, Tsioufis C, Aboyans V, Desormais I, ESC Scientific Document Group: 2018 ESC/ESH Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension. Eur Heart J, 2018; 39: 3021-3104 [Google Scholar]

- 22).Regitz-Zagrosek V Roos-Hesselink JW, Bauersachs J, Blomström-Lundqvist C, Cífková R, De Bonis M, Iung B, Johnson MR, Kintscher U, Kranke P, Lang IM, Morais J, Pieper PG, Presbitero P, Price S, Rosano GMC, Seeland U, Simoncini T, Swan L, Warnes CA, ESC Scientific Document Group: 2018 ESC Guidelines for the management of cardiovascular diseases during pregnancy. Eur Heart J, 2018; 39: 3165-3241 [Google Scholar]

- 23).https://www.jpnsh.jp/data/jsh2019/JSH2019_noprint.pdf (Accessed June 1, 2022). In Japanese [Google Scholar]

- 24).Peters SA, Woodward M: Women’s reproductive factors and incident cardiovascular disease in the UK Biobank. Heart, 2018; 104: 1069-1075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]