Abstract

Background:

Crashes involving farm equipment (FE) are a major safety concern for farmers as well as all other users of the public road system in both rural and urban areas. These crashes often involve passenger vehicle drivers striking the farm equipment from behind or attempting to pass, but little is known about drivers’ perceived norms and self-reported passing behaviors. The objective of this study is to examine factors influencing drivers’ farm equipment passing frequencies and their perceptions about the passing behaviors of other drivers.

Methods:

Data were collected via intercept surveys with adult drivers at local gas stations in two small rural towns in Iowa. The survey asked drivers about their demographic information, frequency of passing farm equipment, and perceptions of other drivers’ passing behavior in their community and state when approaching farm equipment (proximal and distal descriptive norms). A multinomial logistic regression model was used to estimate the relationship between descriptive norms and self-reported passing behavior.

Results:

Survey data from 201 adult drivers showed that only 10% of respondents considered farm equipment crashes to be a top road safety concern. Respondents who perceived others passing farm equipment frequently in their community were more likely to report that they also frequently pass farm equipment. The results also showed interactions between gender and experience operating farm equipment in terms of self-reported passing behavior.

Conclusions/Implications:

Results from this study suggest local and state-level norms and perceptions of those norms may be important targets for intervention to improve individual driving behaviors around farm equipment.

Keywords: Farm equipment, Public roads, Occupational accidents/injuries, Descriptive norms, Rural roads, Overtaking/passing

1. Introduction

Transportation is the leading mechanism for agricultural-related fatality and injury, and roadway crashes with farm equipment contribute significantly to this burden (Costello et al., 2009; Gerberich et al., 1996; Mehlhorn et al., 2015). Farm equipment refers to vehicles specifically designed for agricultural use, such as combines, farm tractors, fertilizers, feeders, towed grain carts, and wagons (Agrifarming, 2019). According to the National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH), 410 farm workers and farmers died from work-related injuries in the US in 2019 (a fatality rate of 19.4 per 100,000 workers), with transportation incidents being the leading cause. Crashes involving farm equipment are not just a rural occurrence (NIOSH, 2019). Approximately one third of farm equipment-involved crashes occur in or near urban areas (Harland et al., 2014), where suburban and urban motorists interact with farm equipment—vehicles that are typically large, low-speed, and have less maneuverability.

Farm equipment crashes are most often the fault of the other vehicle drivers (Peek-Asa et al., 2007; Pinzke et al., 2014) with more than half of those crashes occurring when another vehicle rear-ends (30%) or attempts to overtake and pass (21%) the farm equipment (Peek-Asa et al., 2007). Passing such a large vehicle might require non-farm vehicle drivers to enter the opposing lane to assess if it is safe to pass, which could increase the risk of a collision (Kinzenbaw, 2008). In addition, the use of towed-behind farm implements (e.g., grain wagons) makes visibility more difficult and increases the passing time (Schwab, 2009)

The fatality rate of farm equipment-involved crashes is high—nearly five times more than the average for all road crashes (Karimi & Faghri, 2021). Given the high fatality rate and occurrence on both rural and suburban roads, crashes involving farm equipment have become a community-wide safety concern. Community-based interventions have been demonstrated to improve safety culture for a variety of hazardous driving behaviors (e.g., youth speeding, not using seatbelt, drunk driving) (Ramirez et al., 2013; Vasudevan et al., 2009; Yadav & Kobayashi, 2015). Given that farm equipment related crashes are a community concern and community-based interventions have been effective in changing safety culture, it is important to identify community-level road safety factors (e.g., social norms) that can be targeted for interventions.

Previous studies and theories, like the theory of planned behavior (TPB), indicate that behaviors can be influenced by social norms (Ajzen, 1991; Cialdini et al., 1991). Compared with injunctive norms (i.e., perceptions of the degree to which the majority of others approve or disapprove of the target behavior), descriptive norms (i.e., perceptions of how people actually behave) have been shown to have a greater impact on behavior (Zou et al., 2019). Several studies have shown perceptions of traffic safety and driving-related descriptive norms to be predictors of distracted driving and other driving violations (Carter et al., 2014; Forward, 2009).

Community interventions targeting social norms have been shown to be more effective in changing behavior than interventions appealing to fears or punitive consequences (Kok et al., 2014). Therefore, to design an effective community-based intervention to reduce crashes caused by passing farm equipment, it is necessary to understand the perceptions of passing behaviors among community members as well as their own passing behaviors. The objective of this study was to examine predictors of drivers’ self-reported farm equipment passing behavior when encountering farm equipment on the roadway. This study hypothesized descriptive norms around community farm equipment passing behavior to be associated with self-reported passing behavior.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study design and population

Intercept surveys were conducted in two small rural towns to identify driver perceptions of road safety issues and passing behaviors in their communities. The towns were chosen for their similarity in size and demographic composition, and they represent two distinct areas in the state of Iowa. Both towns were approximately five square miles and had populations between 3,000 and 4,000. In the two counties where the two towns are located, rural areas accounted for 58% and 69% of the total county populations, respectively.

2.2. Data collection procedures

Data were collected in the two rural communities during the fall of 2018 and the spring of 2019 by approaching gas station customers who appeared to be drivers. The surveys took less than 3 minutes to complete, and respondents received a $5 gift card to the gas station for participating in the study. To be eligible, respondents had to live or work within the community’s county and be at least 18 years old. Responses were collected by the research team using tablet computers and Qualtrics software.

2.3. Variables

The outcome of interest was self-reported passing behavior, based on the survey question “How often do you pass when encountering farm equipment on the road?”. This outcome was recorded as an ordinal variable with five categories but was recategorized into three functional categories for modeling purposes: “Always/Most of the time,” “Sometimes,” and “Rarely/Never.” The 5-point scale was consolidated into 3 ordered categories to aid interpretation and modeling. To preserve the information contained by the ordinal nature of this variable and for ease of interpretation, an ordinal logistic regression with proportional odds, also known as a cumulative logit model, was chosen. A score test for the proportional odds assumption was performed to determine whether the relationship between any two combined adjacent outcome categories and the remaining category could be assumed to be the same. That is, it was presumed the coefficient from the ordinal logistic regression model is the same when comparing the outcomes Always/Mostly and Sometimes versus Rarely/Never as when comparing Always/Mostly versus Sometimes and Rarely/Never.

Primarily, the study was interested in the role of proximal descriptive norms as a predictor of self-reported passing behavior. Proximal descriptive norms in this context refer to how a person’s perception of the passing behavior of drivers in their community influences their own passing behavior. To compare the effects of descriptive norms at the state and community levels, distal descriptive norms were also included. Distal descriptive norms in this case refer to how a person’s perception of the passing behavior of drivers in their state influences their own passing behavior. The intercept surveys captured two variables that address how people perceive local drivers’ farm equipment passing behaviors— “perceived community passing frequency” and “perceived state passing frequency.” The former variable corresponds to the primary analysis of proximal descriptive norms, and the latter to the secondary analysis on distal descriptive norms. These variables were measured as the percentage of the time the respondent believed people in their community or state pass when they encounter farm equipment on the road.

Potential explanatory variables for self-reported passing behaviors and perceived passing behaviors collected include residence (Do you live or work in town?), experience driving farm equipment on the road (Have you ever operated farm equipment on the road?), and whether respondents had seen any messages in their community about safely sharing the road with farm equipment within the past month. The survey also collected respondents’ demographic information, including gender (with six options: male, female, genderqueer/non-binary, intersex, transgender FTM (female-to-male), transgender MTF (male-to-female), and other), age (as an inclusion criterion for respondents over 18 years old), and their top three road safety concerns (What do you believe are the top three road safety issues in your community?). These open-ended road safety concern responses were inductively coded into several categories, including one for farm equipment concerns that was considered in regression modeling. Data were entered into Qualtrics along with an indicator variable for each community surveyed.

2.4. Data analysis

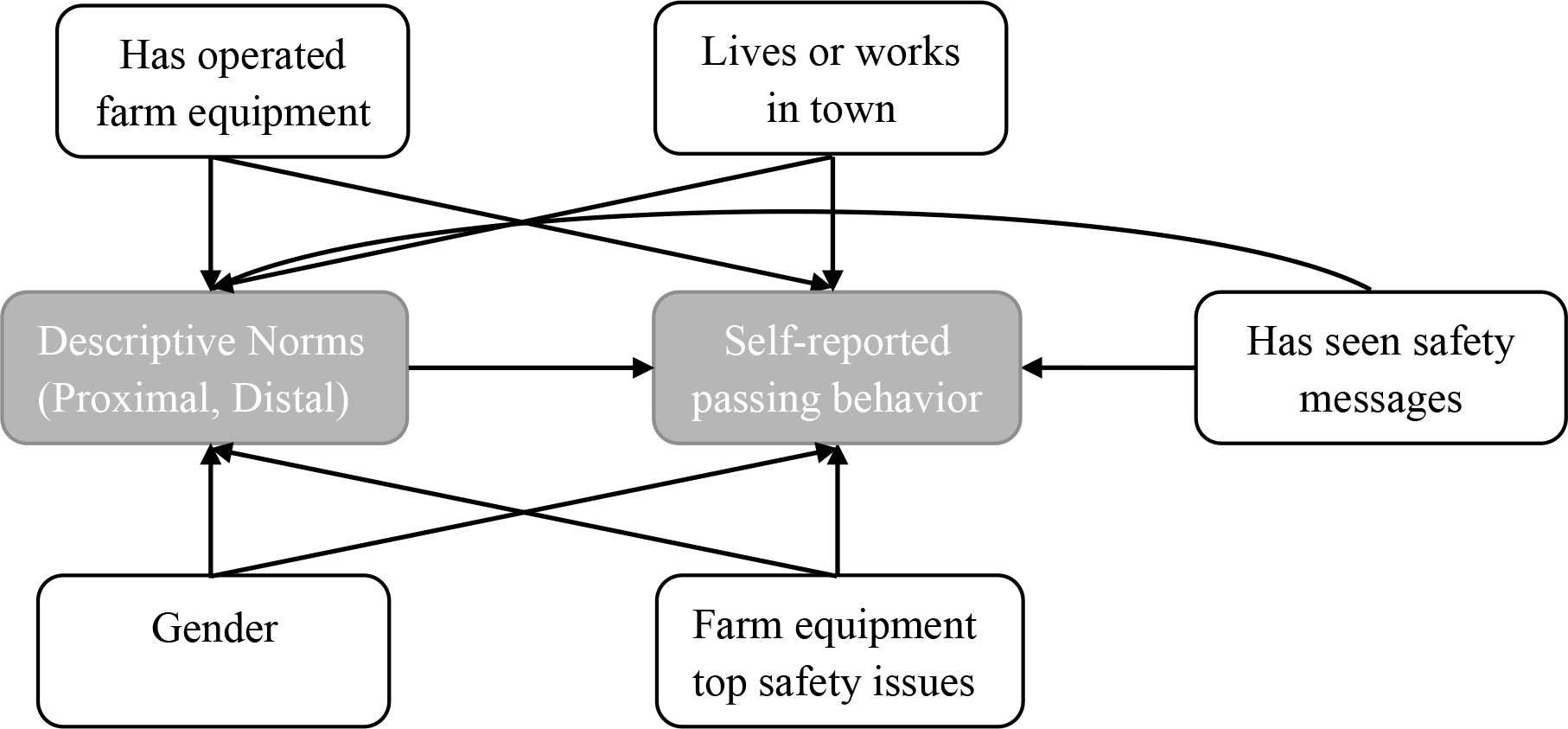

The distributions of survey responses were compared between the two rural towns where intercept surveys were conducted. After confirming there were no meaningful differences between the characteristics of responses between two towns (in terms of demographic variables, such as gender distribution, etc..), the data were combined and analyzed as one sample using SAS 9.4. Descriptive statistics including frequencies and distributions were examined and independent measures of association were produced for each potential explanatory variable’s association with self-reported passing behaviors, perceived community passing behaviors, and perceived state passing behaviors. An ordinal logistic regression model with proportional odds was formulated to explain self-reported passing behaviors. Based on TPB and previous research, a directed acyclic graph (DAG) was developed to guide the selection of potential explanatory variables for the regression model (Figure 1). The primary explanatory variable of this DAG is the descriptive norms, and the primary outcome is self-reported passing behavior, while the other variables are potential confounders. The variable selection process for model analysis is described in the following sections.

Figure 1:

Proposed model for respondent passing behavior when encountering farm equipment.

As a first step, variable selection for all potential explanatory variables was performed using a backwards elimination algorithm to determine the best model fit, where the variable removals were governed by the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC). Two hypothesized interaction terms were investigated based on a prior knowledge—one between gender and experience driving farm equipment and another between gender and descriptive norms. However, all other possible interaction terms were also considered for the sake of completeness.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive statistics

A total of 201 individuals participated in this study (Table 1). All participants identified as either male or female, with more than half (54.2%) being male, and 51.7% had experience operating farm equipment on roadways. In comparison to 71% of males, 28% of females reported having experience operating farm equipment. About 10% of the sampled population neither lived in nor worked in town where the survey was conducted but did live within the county. Half of the respondents in this study (50.5%) reported passing farm equipment always or most of the time. Although nearly half (46.2%) of the study respondents reported seeing safety messages about safely sharing the road with farm equipment, when asked what they believed were the top three road safety issues for their community, only 10% mentioned farm equipment as one of their top three road safety concerns. In comparison, the road safety concerns reported by the most respondents were road condition and infrastructure (36%), the driving behaviors of others (30%), and distracted driving (20%).

Table 1 -.

Distribution of self-reported farm equipment passing frequency by demographic characteristics, seeing safety messages, reporting FE as a safety issue, and perceptions of passing behavior.

| Self-reported farm equipment passing frequency | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Candidate Explanatory Variables | Total N=201 | Always/Most of the time N = 102 | Sometimes N = 73 | Rarely/Never N = 26 |

|

| ||||

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | |

|

| ||||

| Do you live or work in town? | ||||

| Yes | 179 (89.1) | 90 (50.3) | 65 (36.3) | 24 (13.4) |

| No | 22 (10.9) | 12 (54.6) | 8 (36.4) | 2 (9.1) |

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 92 (45.8) | 30 (32.6) | 41 (44.6) | 21 (22.8) |

| Male | 109 (54.2) | 72 (66.1) | 32 (29.4) | 5 (4.6) |

| Farm equipment driving experience | ||||

| Yes | 104 (51.7) | 62 (59.6) | 30 (28.8) | 12 (11.5) |

| No | 97 (48.3) | 40 (41.2) | 43 (44.3) | 14 (14.4) |

| Saw safety messages | ||||

| Yes | 92 (45.8) | 44 (47.8) | 34 (37.0) | 14 (15.2) |

| No/Unsure | 109 (54.2) | 58 (53.2) | 39 (35.8) | 12 (11.0) |

| Reported farm equipment as a top road safety issue | ||||

| Yes | 20 (10.0) | 12 (60.0) | 6 (30.0) | 2 (10.0) |

| No | 180 (90.0) | 90 (50.0) | 67 (37.2) | 23 (12.8) |

|

| ||||

| Descriptive Norms: Passing Behaviors | Median (Q1-Q3) | Median (Q1-Q3) | Median (Q1-Q3) | Median (Q1-Q3) |

|

| ||||

| What percent of time do the people in your community pass when they encounter farm equipment on the road? | 75 (60–90) | 87.5 (75–95) | 75 (50–75) | 72.5 (50–90) |

| What percent of the time do the people in Iowa pass when they encounter farm equipment on the road? | 75 (60–90) | 85 (75–95) | 75 (55–80) | 55 (50–75) |

Male respondents were twice as likely as female respondents to self-report passing farm equipment “always” or “most of the time” (66.1% versus 32.6%). Respondents with experience operating farm equipment on the road were more likely to report passing farm equipment “always” or “most of the time” than those without experience (59.6 % versus 41.2%). There were similar distributions of self-reported passing behaviors among respondents who lived or worked in town, had seen a safety message about passing farm equipment in the past month, or had considered farm equipment to be a top road safety issue.

For respondents who self-reported passing farm equipment “Always” or “Most of the time,” the median response to the question “What percent of the time do the people in your community pass when they encounter farm equipment on the road?” was 87.5%. Among those who self-reported passing farm equipment “Sometimes,” the median response was lower, at 75%. Finally, among those who self-reported passing farm equipment “Rarely” or “Never,” the median response to the same question was similar to the “Sometimes” category, at 72.5%. This pattern suggests that drivers who believe they personally pass farm equipment more often tend to perceive that people in their community also frequently pass farm equipment. Respondents who rarely or never pass farm equipment tend to perceive that people in their community pass more frequently than they do themselves. There was a similar pattern among responses to the question “What percent of the time do the people in Iowa pass when they encounter farm equipment on the road?”. Among respondents who self-reported passing farm equipment “Always” or “Most of the Time,” the median response was 85%; for those who pass farm equipment “Sometimes”, the median response was 75%; for those who pass farm equipment “Rarely” or “Never”, the median response was 55%.

3.2. Predictors of self-reported farm equipment passing behaviors

For the analysis of the proximal (community) norms, an ordinal logistic regression model with partial proportional odds was developed for self-reported passing frequency using backwards selection based on AIC (Table 2). All but one of the predictors selected by AIC met the assumption of proportional odds as assessed by the score test for proportional odds. The main variable of interest, perceived community passing frequency, did not meet this assumption and was therefore allowed to have unequal slopes relating it to the levels of self-reported passing frequency. Other potential covariates included respondent age, gender, whether they lived or worked in town, whether they had experience driving farm equipment, whether they had seen safety messaging, and the two hypothesized interaction terms. Only the covariates for gender, farm equipment experience, perceived community passing frequency, and the interaction between gender and farm equipment driving were chosen by the AIC selection algorithm for the best fitting model. Therefore, when explaining the relationship between proximal descriptive norms and the outcome, it is necessary to control for the gender of the survey respondent and their experience with driving farm equipment on the road. The model for the secondary analysis, the distal model, was similar to the first model but includes the covariate for perceived state passing frequency (distal norms) rather than perceived community passing frequency (proximal norms). The same covariate selection process was applied, and the same covariates were selected. Results for both the proximal and distal models in predicting self-reported farm equipment passing behavior are recorded in (Table 2). Proximal (‘Always/Most of the time’ versus ‘Sometimes’ and ‘Rarely/Never’) and distal norms were positively related to self-reported passing behavior. Participants who believed that others in their community and state frequently pass farm equipment were almost 5.5% more likely to report passing FEs. The interaction between gender and farm equipment driving experience was highly associated with self-reported passing behavior. Males with farm equipment driving experience, in particular, were more likely to report passing farm equipment compared females with or without driving experience and males without farm equipment driving experience.

Table 2:

Predictors of self-reported farm equipment passing behavior comparing proximal (community) and distal (state) descriptive norms as main independent variables.

| Proximal (community) model | Distal (state) model | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| OR | 95% Wald CI | OR | 95% Wald CI | |

|

| ||||

| What percent of time do the people in your community pass when they encounter farm equipment on the road? * | NA | NA | ||

| ‘Always/Most of the time’ versus ‘Sometimes’ and ‘Rarely/Never | 1.056 | (1.03, 1.08) | ||

| ‘Always/Most of the time’ and ‘Sometimes’ versus ‘Rarely/Never’ | 1.014 | (0.99, 1.04) | ||

| What percent of the time do the people in Iowa pass when they encounter farm equipment on the road? | NA | NA | 1.05 | (1.03, 1.06) |

| Gender (Ref = Female) | 1.83 | (0.76, 4.42) | 1.98 | (0.84, 4.69) |

| Experience driving farm equipment (Ref = No experience) | 0.36 | (0.14, 0.89) | 0.41 | (0.17, 1.03) |

| Gender x Experience driving farm equipment | 8.12 | (2.17, 28.23) | 6.36 | (1.76, 22.91) |

This variable violated the proportional odds assumption in the proximal model; therefore, two coefficients are reported.

3.3. Gender and experience driving farm equipment

For both the proximal and distal models, the effect of farm equipment experience on self-reported passing frequency is moderated by gender (Table 3). The following results correspond to the primary analysis using the proximal model including perceived community passing frequency. Assuming a constant effect of proximal norms, the male respondents with experience driving farm equipment had nearly 3 times the odds of passing farm equipment more frequently (i.e., being in a higher passing frequency category) compared to males without farm equipment driving experience [OR = 2.93, CI = (1.16, 7.42)]. In contrast, for female survey respondents with experience driving farm equipment, the odds of being in a higher passing frequency category were 64% lower than for females without experience driving farm equipment, assuming a constant effect of proximal norms [OR = 0.36, CI = (0.15, 0.90)]. Also, the effects of gender can be interpreted when holding constant the effect of farm equipment driving experience. Out of all respondents who said they did not have farm equipment driving experience, males may be more likely to pass more frequently than females [OR = 1.83, CI = (0.76, 4.42)]. Although this relationship is not statistically significant at the 5% level, the bounds of the confidence interval suggest a positive relationship. Among survey respondents who had experience driving farm equipment, the odds of males passing more frequently were nearly 15 times higher than for females [OR = 14.87, CI = (5.50, 40.20)].

Table 3:

Comparison of Gender and Experience Driving Farm Equipment (Proximal Model)

| Odds Ratio | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Males versus Females | ||

| Experience | 14.87 | (5.50, 40.20) |

| No experience | 1.83 | (0.76, 4.42) |

| Experience versus No experience | ||

| Male | 2.93 | (1.16, 7.42) |

| Female | 0.36 | (0.14, 0.89) |

3.4. Proximal norms and self-reported passing frequency

The results suggest that an increase in perceived community-wide passing frequency corresponds to an increase in the odds that the respondent self-reported their own passing frequency to be in a higher rather than lower category. That is, a higher percentage of perceived community passing frequency corresponds to a survey respondent being more likely to classify their own passing frequency as “Sometimes” over “Rarely/Never,” and more likely to classify their passing frequency as “Always/Most of the time” over “Sometimes.”

The magnitude of the effect of perceived community passing frequency on the outcome differs depending on which levels of self-reported passing frequency are being compared, as shown by the two estimates reported in Table 2. Although the point estimates differ, the confidence intervals point to an effect in the same direction so they may be interpreted similarly.

A one-percent increase in perceived community passing frequency corresponds to the odds of being in the highest self-reported passing category as opposed to the others (i.e., ‘Always/Most of the time’ versus ‘Sometimes’ and ‘Rarely/Never’) increasing by about 6% while controlling for all other covariates. Likewise, a one-percent increase in perceived community passing frequency corresponds to the odds of being in one of the two higher self-reported passing categories (i.e., ‘Always/Most of the time’ and ‘Sometimes’ versus ‘Rarely/Never’) increasing by about 1% while controlling for all other covariates.

4. Discussion

This study aimed to examine self-reported passing behaviors when encountering farm equipment on the road. Even though crashes involving farm equipment are five times more deadly than crashes without farm equipment (Muelleman & Mueller, 1996; Muelleman et al., 2007), the safety concerns surrounding farm equipment on the road were not reported as a priority in the two rural communities that were sampled. The results showed very low prioritization of farm equipment within top road safety issues reported among rural residents, indicating an opportunity to increase awareness and education. This low prioritization is consistent with a previous Australian study, which found that the majority of participants perceive interactions with large agricultural equipment as neutral (King et al., 2021).

In line with previous studies, the findings suggest that descriptive behavioral norms are often predictive of individual and health risk behaviors (Rivis & Sheeran, 2003). Results indicate a significant but small relationship between proximal and distal descriptive norms and self-reported farm equipment passing frequency. The relationship between self-reported driving behaviors and proximal descriptive norms found in this study has been demonstrated in other studies examining local safety culture and risky driving topics (e.g., distracted driving, speeding) (Møller & Haustein, 2014; Trivedi & Beck, 2018).

Results from this study showed that male respondents were more likely to report passing farm equipment than female respondents, supporting well-documented evidence that males tend to be riskier drivers (Rhodes & Pivik, 2011; Ventsislavova et al., 2021). Prior experience driving farm equipment had differential effects for male and female respondents. Male respondents with experience driving farm equipment were more likely to report passing farm equipment than male respondents without experience. In contrast, female respondents with previous farm equipment experience were less likely to pass farm equipment than female respondents without experience. Holland et al. (2010) examined the effects of driving experience (measured as the number of months driving) on adolescent driving style and reported that for males more driving experience led to increased carefulness and reduced high-velocity and angry driving, while the opposite was found for females (Holland et al., 2010). Despite different participant groups (adolescents in the Holland study and adult drivers here) and differences in measuring driving experience, the Holland findings may be relevant and in some ways contradictory to ours. More experience driving farm equipment may lead to safer driving in females compared to males in interactions with farm equipment, whereas experience driving passenger cars may have a completely different effect on male and female drivers. A possible explanation for this seemingly opposite trend between males and females could be differing amounts of driving experience, which was not measured in this study. For example, males may have driven FE but have done so rarely, while the females who have driven FE may be very experienced at it (i.e., more males have more casual experience while more females have more extensive experience. To the best of our knowledge, no prior studies have examined the impact of descriptive norms and the interaction of farm equipment driving experience and gender on self-reported drivers’ passing behavior, in general, or specific to the passing of farm equipment.

These results have several theoretical and practical implications for both policymakers and road safety campaigns. This study examined the perceptions people held about their own passing behaviors around farm equipment and those of others in their community and state. The findings can be used to develop driver education and intervention programs by providing the following suggestions: 1) Community perspectives, local voices, and related context should drive safety interventions, not state-level policies, 2) Messages/interventions may need to be different depending on gender and experience operating farm equipment.

4.1. Limitations

Self-reported surveys were used rather than direct observation of participants’ behavior, however, this study was focused on perceptions which can include perception of the person’s own behavior. The self-reported passing frequency provides information about the prevalence of passing behaviors but does not directly measure the riskiness of those passing behaviors. Also, the collection of self-reported passing frequency as a categorical variable rather than a percentage prevented direct comparisons between self-reported passing rates, perceptions of community and state passing rates using percentages. In addition, the study’s small sample size may not be representative of Iowa’s drivers.

Though likely a combination of both, our study was not able to determine if respondents’ passing behaviors and experiences influenced their perceptions of community and state passing rates, or if their perceptions of community and state passing rates influenced their passing behaviors. Future research should attempt to clarify directionality of this relationship further, as understanding this relationship will aid in the creation of effective road safety interventions for rural road users. Future examination of the norms around how people are expected to behave by the community (injunctive norms) would also be beneficial.

5. Conclusions

This study emphasizes a need for increasing social awareness and knowledge about safely sharing the road with farm equipment. The results demonstrated a significant relationship between self-reported passing behaviors and proximal descriptive norms that could help guide future rural road safety campaigns to target messaging to alter norms at community and state-level as well as individual behavior. Additionally, the results suggest males with farm equipment driving experience as a key demographic audience to target due to their high reported passing frequency.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the community members who took part in this study and the student research assistants who were instrumental in data collection.

Funding

This work was supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (grant number U54 OH 007548). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or the Department of Health and Human Services.

Footnotes

Declaration of competing interest

The authors do not have any competing interests to declare.

References

- Agrifarming. (2019). Farm machinery types, uses, and importance, June 1, 2019. https://www.agrifarming.in/farm-machinery-types-uses-and-importance

- Ajzen I (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational behavior and human decision processes, 50(2), 179–211. [Google Scholar]

- Carter PM, Bingham CR, Zakrajsek JS, Shope JT, & Sayer TB (2014). Social norms and risk perception: Predictors of distracted driving behavior among novice adolescent drivers. Journal of Adolescent Health, Elsevier., 54(5), S32–S41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cialdini RB, Kallgren CA, & Reno RR (1991). A focus theory of normative conduct: A theoretical refinement and reevaluation of the role of norms in human behavior. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, (Vol. 24, pp. 201–234). [Google Scholar]

- Costello TM, Schulman MD, & Mitchell RE (2009). Risk factors for a farm vehicle public road crash. Accident Analysis & Prevention, 41(1), 42–47. 10.1016/j.aap.2008.08.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forward SE (2009). The theory of planned behaviour: The role of descriptive norms and past behaviour in the prediction of drivers’ intentions to violate. Transportation research part F: traffic psychology and behaviour, 12(3), 198–207. [Google Scholar]

- Gerberich SG, Robertson LS, Gibson RW, & Renier C (1996). An epidemiological study of roadway fatalities related to farm vehicles: United States, 1988 to 1993. Journal of occupational and environmental medicine, 1135–1140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harland KK, Greenan M, & Ramirez M (2014). Not just a rural occurrence: differences in agricultural equipment crash characteristics by rural–urban crash site and proximity to town. Accident Analysis & Prevention, 70, 8–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland C, Geraghty J, & Shah K (2010). Differential moderating effect of locus of control on effect of driving experience in young male and female drivers. Personality and individual differences, 48(7), 821–826. [Google Scholar]

- Karimi K, & Faghri A (2021). Farm vehicle crashes on US P\public roads: A review paper. Open Journal of Safety Science and Technology, 11(2), 34–54. [Google Scholar]

- King JC, Franklin RC, & Miller L (2021). Traversing community attitudes and interaction experiences with large agricultural vehicles on rural roads. Safety, 7(1), 4. [Google Scholar]

- Kinzenbaw CR (2008). Improving safety for slow-moving vehicles on Iowa’s high speed rural roadways. Iowa State University. [Google Scholar]

- Kok G, Bartholomew LK, Parcel GS, Gottlieb NH, & Fernández ME (2014). Finding theory-and evidence-based alternatives to fear appeals: Intervention Mapping. International Journal of Psychology, 49(2), 98–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehlhorn SA, Wilkin H, Darroch B, & D’Antoni J (2015). Physical characteristics of farm equipment crash locations on public roads in Tennessee. Journal of agricultural safety and health, 21(2), 85–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Møller M, & Haustein S (2014). Peer influence on speeding behaviour among male drivers aged 18 and 28. Accident Analysis & Prevention, 64, 92–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muelleman RL, & Mueller K (1996). Fatal motor vehicle crashes: variations of crash characteristics within rural regions of different population densities. Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery, 41(2), 315–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muelleman RL, Wadman MC, Tran TP, Ullrich F, & Anderson JR (2007). Rural motor vehicle crash risk of death is higher after controlling for injury severity. Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery, 62(1), 221–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NIOSH. (2019). Agricultural Safety. National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, United States. August 2, 2019. https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/topics/aginjury/

- Peek-Asa C, Sprince NL, Whitten PS, Falb SR, Madsen MD, & Zwerling C (2007). Characteristics of crashes with farm equipment that increase potential for injury. The Journal of Rural Health, 23(4), 339–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinzke S, Nilsson K, & Lundqvist P (2014). Farm tractors on Swedish public roads–age-related perspectives on police reported incidents and injuries. Work, 49(1), 39–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez M, Yang J, Young T, Roth L, Garinger A, Snetselaar L, & Peek-Asa C (2013). Implementation evaluation of Steering Teens Safe: engaging parents to deliver a new parent-based teen driving intervention to their teens. Health education & behavior, 40(4), 426–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes N, & Pivik K (2011). Age and gender differences in risky driving: The roles of positive affect and risk perception. Accident Analysis & Prevention, 43(3), 923–931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivis A, & Sheeran P (2003). Descriptive norms as an additional predictor in the theory of planned behaviour: A meta-analysis. Current psychology, 22, 218–233. [Google Scholar]

- Schwab C (2009). Agricultural Equipment on Public Roads. [Google Scholar]

- Trivedi N, & Beck KHT (2018). Do significant others influence college-aged students texting and driving behaviors? Examination of the mediational influence of proximal and distal social influence on distracted driving. Transportation research part F: traffic psychology and behaviour, 56, 14–21. [Google Scholar]

- Vasudevan V, Nambisan SS, Singh AK, & Pearl T (2009). Effectiveness of media and enforcement campaigns in increasing seat belt usage rates in a state with a secondary seat belt law. Traffic injury prevention, 10(4), 330–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ventsislavova P, Crundall D, Garcia-Fernandez P, & Castro C (2021). Assessing willingness to engage in risky driving behaviour using naturalistic driving footage: the role of age and gender. International journal of environmental research and public health, 18(19), 10227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yadav R-P, & Kobayashi M (2015). A systematic review: effectiveness of mass media campaigns for reducing alcohol-impaired driving and alcohol-related crashes. BMC public health, 15(1), 1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou X, Savani KJJ, & Making D (2019). Descriptive norms for me, injunctive norms for you: Using norms to explain the risk gap. Judgment and Decision Making, 14(6), 644. [Google Scholar]